ABSTRACT

Little is known about student aging interest groups (AIGs) in post-secondary institutions. Our study evaluated awareness of a student aging interest group at a western Canadian university with no gerontology program. Additional goals included assessing interest in joining the AIG, participation rates among group members, and preferences for group activities. Using a mixed method approach we analyzed 13 years of administrative data recording 65 meetings and conducted a survey among group members and nonmember students across the university with a potential interest in aging (n = 52). Almost two-thirds of respondents (n = 33) were nonmembers with most of these (n = 24) having no prior knowledge of the AIG; 77% of students already aware of the AIG learned about it from a professor. Sixty per cent of respondents were in health-related faculties, with the remainder representing multiple disciplines and faculties. Group attendance was strongly influenced by student workloads and schedules, with average attendance rising by 27.3% during the shift to virtual meetings in 2020–21. Our results highlight the interdisciplinary nature of aging studies, the key role faculty members play in informing students about AIGs, and the broad range of interests that students have in issues related to age and aging.

Introduction

Population aging is a global phenomenon that has led to increased demand for services aimed at older adults across social, health and business sectors. However, the growth in aging education in post-secondary institutions has not grown at the same pace as the demand for working professionals (Andrews, Campbell, Denton, & McGilton, Citation2009; Boscart, McCleary, Huson, Sheiban, & Harvey, Citation2017). Student (and faculty) awareness of the importance of gerontological and geriatric content in coursework also appears to be lagging (Boscart, McCleary, Huson, Sheiban, & Harvey, Citation2017; Glauser, Citation2019).

There are multiple preexisting barriers for post-secondary students who may otherwise be more amenable to pursuing aging as a topic of study, such as being uninformed about aging, feeling disinterest or even disdain about age-related issues, and lacking awareness of the opportunities related to aging across multiple job sectors (Lawrence et al., Citation2003; Lun, Citation2012; Obhi & Woodhead, Citation2016; Wesley, Citation2005). To counteract these issues, it is important to better inform students about age and aging as early as possible, and a student interest group is one mechanism to help generate such exposure (Louw, Turner, & Wolvaardt, Citation2018).

Jones, Vandenberg, and Bottsford (Citation2011) define an Aging Interest Group (AIG) as any voluntary group of health profession students who explore topics related to aging. This article describes an evaluation of an AIG named Students Targeting Aging Research or STAR, located at a research-intensive Canadian university that does not have a dedicated gerontology program at either the undergraduate or graduate level. Group membership is open to any student enrolled at the university across all levels of study and from any faculty or discipline. As such, rather than limiting the definition of an AIG to the health professions, we instead define an AIG as any voluntary group of post-secondary students interested aging.

Context

The University of Manitoba is the largest university in the province, with over 31,000 students on two main campuses, Fort Garry and Bannatyne (University of Manitoba, Citation2021b). The Fort Garry campus is the setting for the bulk of the university buildings, facilities and research centers while the Bannatyne campus, located adjacent to the province’s largest hospital, offers graduate training in medicine and allied health fields. There is no gerontology program, rather the university offers an interfaculty Option in Aging which consists of aging-related coursework offered across five facultiesFootnote1 resulting in a transcript notation (University of Manitoba, Citation2021a), as well as a Graduate Focus on Aging Concentration for students enrolled in any graduate program at the University.

The Center on Aging (hereinafter referred to as “the Center”) at the University of Manitoba is the provincial focal point for interdisciplinary research in aging-related areas and, while it is not a teaching unit, it supports training in aging and is active in community outreach. The Center also hosts the university’s student-led STAR AIG. Student members represent any discipline taught at the university through any level of study, from first year undergraduates through doctoral students. STAR allows students to engage with one another while also connecting with academics, working professionals and older adult community members.

Established in 2013, the group is student-led and hosts monthly meetings throughout the academic year; meetings variously involve talks by working professionals, researchers, community members, and group alumni, group discussion, and networking opportunities. Students may optionally be included in the Center mailing list to receive bi-weekly newsletters and other relevant communications such as opportunities for scholarships, additional training, and career-forwarding information such as openings for research assistants, volunteers and paid work in the community. STAR also participates in outreach activities with local community groups that focus on aging.

Purpose

In the fall of 2020, the STAR mailing list included more than 100 student e-mail addresses, however, attendance at monthly meetings was usually fewer than 10 students. Further, we were the only student AIG at our university with a student body numbering over 31,000 people. Based on these facts, and our belief that learning about aging is important, we hoped to broaden our reach as evidenced by increased group membership and attendance at activities and meetings. Our project asked, “How can we increase student engagement in STAR?” Our goal was to assess awareness of STAR in the study body at large, to describe basic characteristics of our membership, assess interest level and participation rates, and collect thoughts and ideas for improvement.

Literature review

The pursuit of education related to a career in aging is strongly influenced by personal history and meaningful experiences with older adults (Lawrence et al., Citation2003; Wesley, Citation2005). Unfortunately, student perceptions of working with older adults are mostly negative and tend to conform with common ageist assumptions, such as associating old age with dependency and frailty, which may deter students from pursuing an education in gerontology (Algoso, Peters, Ramjan, & East, Citation2016). Additional barriers for pursuing an education in age-related issues include being uninformed about aging and older populations, lacking knowledge about careers in aging, and apprehension about finding employment in the field (Hebditch et al., Citation2020; Obhi & Woodhead, Citation2016). Opportunities for intergenerational interactions during college years are also important in promoting an interest in aging studies, and professors in aging courses have a responsibility to create and support such opportunities (Jones, Vandenberg, & Bottsford, Citation2011).

One barrier for students that is perhaps most important is a paucity of course-based opportunities for learning about aging. In Canada, for example, there is a lack of education on aging at the undergraduate level and only a limited number of graduate programs on gerontology and geriatrics (Meisner et al., Citation2020; Wister, Kadowaki, & Mitchell, Citation2016). Relatedly, graduates of a major nursing program in western Canada felt their education on aging was under-supported by faculty and the curriculum, with particular deficits related to working with people with dementia (Dahlke, Kalogirou, & Swoboda, Citation2021). In the United States there is a similar concern that aging continues to be non-integrated in the coursework for the health professions, resulting in a labor force without the skills or interest in working with older people (Lee & Richardson, Citation2020)

In contrast, students who have had exposure to interprofessional education (IPE) show more positive attitudes toward older adults and form a more realistic outlook regarding geriatric practice (Gray & Walker, Citation2015; Holmes et al., Citation2020; Mcquown et al., Citation2020; Solberg, Carter, & Solberg, Citation2019). Teamwork and collaboration in the learning environment through IPE also has a positive impact on student attitudes when working with other professionals and on interprofessional teams following graduation (Blachman, Blaum, & Zabar, Citation2021; Holmes et al., Citation2020; Stetten, Black, Edwards, Schaefer, & Blue, Citation2019; Thompson et al., Citation2020). The importance of IPE is widely acknowledged in the health professions, and there is an abundance of research on best practices and student perceptions of such programs. AIGs have also been found to help prepare future health care professionals to function more effectively when working on interprofessional geriatric teams (Jones, Vandenberg, & Bottsford, Citation2011; Schapmire et al., Citation2018).

The literature calls for more supportive environments for students with an interest in gerontology and aging more broadly, not only in the health professions and in geriatrics (Lawrence et al., Citation2003; Miller, Murphy, Cronley, Fields, & Keaton, Citation2019). Interest groups are valuable as they facilitate learning, create a sense of belonging and emotional support, and help establish long-term ties and professional networks (Cammer Paris, Citation1998). Being involved with an AIG has important academic and personal benefits for students, such as enhanced faculty mentorship, networking opportunities, and supporting career advancement (Blachman, Blaum, & Zabar, Citation2021). Students also have the chance to talk through their academic issues and career concerns, and have enhanced opportunities for collaboration and participating in research projects (Perrella, Cuperfain, Canfield, Woo, & Wong, Citation2020). Students involved in an AIG tend to alter their perspectives and preconceptions of older adults, thus AIGs also serve to help dispel stigma relating to aging (Lawrence et al., Citation2003; Perrella, Cuperfain, Canfield, Woo, & Wong, Citation2020).

The importance of AIGs among geriatric students has been noted (Blachman, Blaum, & Zabar, Citation2021; Perrella, Cuperfain, Canfield, Woo, & Wong, Citation2020), although the academic literature on this topic is relatively sparse. For AIGs to be truly interdisciplinary they need to represent cross-cutting interests and competencies spanning multiple bodies of knowledge, yet very little research has been performed regarding AIGs that involve students outside of the health professions. The gap in the literature on AIGs both within and outside of the health sciences emphasizes how limited our knowledge base is regarding why students are not engaging more with AIGs and what we can do to increase student involvement.

Methods

Our project used a conceptual framework for assessing student engagement developed by Ella Kahu (Citation2013) (see ). According to this framework, engagement is influenced by structural factors including university culture and policies, and by psychosocial factors including support, relationships and individual skills development. Consequences or outcomes of engagement include academic achievement, wellbeing, and future career success.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of student engagement. Reproduced from Kahu (Citation2014). CC-BY.

Acknowledging the complexity of the phenomenon of engagement, we focused our study on assessing student engagement in terms of self-reported enthusiasm and interest, and in terms of behavior through group participation and attendance. We did not assess knowledge as our group is not geared toward specific learning outcomes.

Study design

We used a mixed method approach that involved collecting and analyzing administrative data and conducting a survey among STAR group members and other students across the university with a potential interest in aging. The total estimated population of students having an interest in aging was approximately 500 students (described more fully below). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board 1 at the University of Manitoba [Certificate R1-2021:027 (HS24722)].

Administrative data

Center staff have been involved in an important supporting role since the founding of STAR, such as helping students self-organize, facilitating meetings, and linking students with researchers and community organizations and recording/storing group information. This information constitutes our administrative data and includes:

Meeting date, time of day, location; basic record keeping

Attendance; documenting student involvement

Meeting topic and presenter; to ensure variation in programming; maintain a ‘balance’ between student activities and community outreach; ensure community organizations and research affiliates are not over-burdened by requests to speak or alternately under-represented

Survey

Following ethics approval, we conducted an online survey among students. Inclusion criteria included current and former STAR members and nonmember students who might be reasonably expected to be interested in aging. “Reasonably expected” to have an interest in aging refers to all students enrolled in an undergraduate courseFootnote2 offered through the university’s Option on Aging, and student research assistants and graduate students under the supervision of researchers and professors affiliated with the Center. An estimated total population size of about 500 students was established based class enrollment numbers (320), the number of students on the STAR mailing list (107), and an average of 2 students supervised or employed by university researchers affiliated with the Center (120). We assumed that there would be some overlap or duplication such as a student being on the STAR mailing list and supervised by a Center researcher, so rounded down. There were no exclusion criteria.

Recruitment was three-pronged. First, students on the STAR mailing list were emailed directly with an invitation to participate with a link to the online survey. Second, research affiliates of the Center were emailed and asked to forward the same recruitment materials to students under their supervision or employed as research assistants. The third recruitment strategy targeted students enrolled in an aging course. Based on ethics requirements, we sought and received permission from relevant faculty deans and/or department heads to contact instructors, then approached instructors and asked them to forward recruitment materials to their class list. Not all instructors were responsive, and we do not know how many academics forwarded our recruitment materials. The survey was open from March to April 2021, and a two-week reminder was sent out for all recruitment strategies. Students were encouraged to participate with the incentive of a lottery for a $25 gift-card.

The brief 20-question survey took only a few minutes to complete and asked students for basic demographic information, their awareness of STAR, membership status and attendance. Students were invited to write about their academic and research interest in aging studies, indicate their preferences for meeting locations and frequency, and rank their interest level in meeting topics.

Analysis

Quantitative data underwent basic descriptive and inferential analysis using Microsoft Excel, qualitative data was sorted manually to arrive at themes and categories. Administrative and survey data were analyzed separately. From the administrative data, attendance rates were assessed for patterns according to meeting topic, date, or location. The meetings topics were categorized, and these categories were used in the survey to ask students their preferences. The first author manually analyzed long answer responses to a question asking students about their “specific interest in aging” using open coding to arrive at categories or codes/themes. These categories were reviewed and approved by coauthors. We also ran t tests to compare the preferences of undergraduate and graduate students. Finally, the results from both data sources were synthesized to inform the interpretation of the findings.

Results

Administrative data

There were 65 STAR meetings between the fall of 2013 and spring 2021, averaging eight meetings per year (range 6 to 11) and seven students per meeting (range 3–17). In addition to a first “welcome” meeting each September, meeting types were clustered into five categories: research, practice, discussion, networking, and other. Research meetings were presentations on the latest research from Center affiliates, and practice meetings refer to talks with professionals working in government, in the health system, or in the community in age-related areas. Discussion meetings were student-led conversations following a reading or a video presentation, while networking events allowed student members to get to know one another and gathered students and working professionals together to highlight career opportunities in aging. The remainder of meetings were labeled “other,” and this category included talks by older adult community members, presentations from fellow students, and outreach activities such as organizing holiday gift baskets. The bulk of meetings were devoted to research and practice (see ), plus one welcome meeting per year and about one meeting per year for each of discussion, networking and other.

Table 1. Number of STAR meetings by category: Fall 2013 to Spring 2021.

STAR meetings and group activities were held in-person until March 2020, after which time all meetings were held virtually due to COVID-19. The first welcome meeting for each academic year averaged 10 students, higher than the overall average of seven students per meeting. Of note, during the pandemic year of 2020–21, all meetings switched from in-person to virtual and average attendance rose to 11 students per meeting during that year. We found no additional attendance patterns related to meeting date, time, or topic.

Survey data

We had 52 complete responses, representing an approximate response rate of about 10% for nonmembers of STAR and 18% for members. Respondents were equally split between students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, with the majority being women between the ages of 25 and 44 years old (see ).

Table 2. Respondent characteristics (N = 52).

As illustrated in the word cloud in , the majority (60%) of participants were in health and wellness related faculties and departments, with the remainder representing a broad range of academic units including the humanities, architecture and other sciences such as computer science and engineering.

Half of the respondents were unsure of their specific focus or interest in aging, and of those unsure most (65%) were undergraduates. Respondents were asked to share their specific interest in aging, and 27 respondents provided detailed answers. Our analysis of the long-answer responses arrived at seven themes: health, mental health, dementia and cognitive decline, personhood and experiences, technology, caring and care systems, and society and environment. shows themes alongside key concepts from the original responses.

Table 3. Thematic summary of responses to long answer question: “Please share your interest related to aging, being as specific as possible.

Graduate students often shared their dissertation topic incorporating multiple themes (e.g., mental health of family caregivers supporting a person with dementia, or implementation science and care transitions between home and institutions).

Sixty-five per cent of respondents were not STAR members, and most (70%) of these were unaware of the group prior to the survey, equally represented by graduate and undergraduate students. Of those already aware of STAR, most learned about the group from a professor or instructor rather than through our website or posters around campus, with no significant differences between graduate and undergraduate students. Eighteen respondents were current members of STAR and only four reported attending meetings often. Members reporting infrequent or rare attendance at group meetings indicated they were unable to make meeting times or they were too busy (see ).

Table 4. Subsample of 18 STAR members: Meeting attendance and reason for nonattendance.

One STAR member indicated their lack of attendance at meetings was not due to conflicts with classes or busyness but due to accessibility and health issues, with online meetings increasing their likelihood of attending.

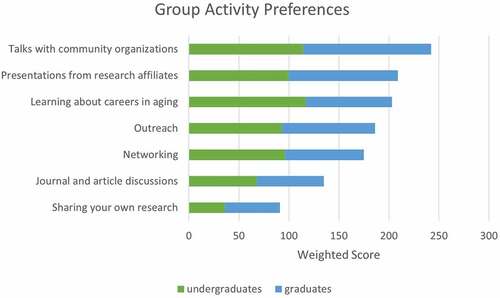

We asked all respondents to rank meeting activities in order of preference from first to last across seven options. Responses were inversely weighted, with first choice scoring seven, second choice scoring six and so on, and then added to give each activity an overall score. As shown in , the top three topics of interest were 1) hearing from community organizations and professionals working in the community (score = 242), 2) attending presentations about the latest research from affiliates at the Center on Aging (score = 209), and 3) learning about careers in aging (score = 203).

We performed T-tests to compare the responses of graduate and undergraduate students and found a significant difference in that undergraduates were more likely to be interested in learning about careers (undergraduates x = 3.125, sd = 2.383; graduates x = 4.261, sd = 1.982. t-test at α = 0.10: df = 44, t-Stat = −1.779, p = 0.08,) and graduate students more likely to be interested in sharing their own research (undergraduates x = 6.5, sd = 1.063; graduates x = 5.609, sd = 1.982. t-test at α = 0.05: df = 36, t-Stat = 2.098, p = 0.04). As part of the question about interest in activities, respondents supplied long-answer suggestions, which included current “hot topics” such as talks on robotics and artificial intelligence, multi-generational meetings incorporating attendance by older adults, and volunteer opportunities in the community.

Finally, we asked students a series of questions about meeting times and formats. Sixty-three per cent indicated that that STAR meetings should alternate or find a balance in some way between the benefits of in-person meetings and the convenience of online meetings.

Discussion

The varied interests and affiliations of students responding to our survey underscore the reality that aging studies can intersect with almost any educational path, many of which do not fit within a typical gerontological program. The future work done by today’s students, regardless of their field of study, will impact and be impacted by our aging population. Universities today, particularly public post-secondary institutions, are increasingly expected to facilitate interdisciplinary research, and this starts with facilitating interdisciplinary teaching and collaboration (Miller, Murphy, Cronley, Fields, & Keaton, Citation2019; Pfirman & Martin, Citation2017). We are not the first to note this fact, and to recommend that gerontology education be incorporated across as many fields as possible, even those areas that might seem unrelated to aging studies (Van Dussen & Weaver, Citation2009). An excellent example of such work is reported by Miller, Murphy, Cronley, Fields, and Keaton (Citation2019) in their case study of an interdisciplinary collaboration among social work, civil engineering and computer science students. Relatedly, it is also important that any aging interest group present a wide assortment of programming to reflect a broad range of topics of potential interest to members.

Among our respondents, the highest preference for meeting topic was hearing from working professionals about jobs in the “real world” and the work being done in the community. As group leaders, all three authors have noted over the years that STAR students interested in working for and with older adults tend to be surprised by the variety of career opportunities available to them outside of medicine and health care. Our respondents also indicated wanting our group to provide more opportunities for intergenerational interaction through community outreach or by having older adults participate in meetings. It is interesting to us that students wish for more interaction and collaboration across many typical divides, whether it is institutional divides of academic discipline or cultural divides based on age itself.

There is a wealth of current resources on effective collaboration in gerontological and geriatric teaching and education for institutions and programs striving to embrace a more interdisciplinary perspective (for example Flores-Sandoval, Sibbald, Ryan, & Orange, Citation2021; Hannon, Hocking, Legge, & Lugg, Citation2018; Holmes et al., Citation2020; Mcquown et al., Citation2020; Schapmire et al., Citation2018; Thompson et al., Citation2020). We did not conduct a systematic review of the literature but based on our brief scan there appears to be abundant resources on collaboration in geriatrics education with less on social gerontology, and we similarly note an emphasis on pedagogy and curricula with less attention to establishing, growing, and sustaining student-led interest groups and extracurricular opportunities in aging studies. To be fair, extracurricular activities are “extra,” but we contend that the extra to be gained from students sharing and learning from each other across all disciplines would benefit the entire field of aging studies.

Of practical note, our analysis found a spike in student attendance at group meetings during the 2020–2021 pandemic year. The change in attendance during COVID is most reasonably explained due to virtual meetings being more convenient for students, allowing more people to attend. The interpretation that online meetings enhance attendance is reinforced in the survey data in which students expressed a preference for future meetings to be held both online and in person; one person specifically indicated that “having meetings online has greatly increased my attendance.” We plan to provide both in-person and virtual options for attending meetings in the future and encourage others to consider the same.

As the population ages, and the need for working professionals with knowledge in aging becomes more apparent, ensuring the availability and engagement of AIGs within post-secondary institutions will be paramount in ensuring the upcoming workforce has the appropriate training. Future research should examine the engagement of students in AIGs at other institutions. Other AIGs could use the findings from the current study to determine whether changes are needed within their group structure to achieve, for example, increased multidisciplinary attendance and accessibility. The results from this study have already led to positive change including the Center modifying the online presence of the STAR group, making the website more accessible and hopefully more meaningful for students. Additionally, using this data as a baseline, we hope to conduct future evaluations on student engagement.

Strengths and limitations

This study has the strength that student survey responses were integrated with an assessment of student group activities conducted over a period of eight years. A weakness is that we do not know the population size of students interested in aging studies, and so cannot claim to have a representative sample. Recruitment was affected by the need for individual faculty members to assist with recruitment; there was a lot going on for professors during that phase of the pandemic and we did not manage to connect with all relevant professors. In tandem with this issue, our response rate was likely impacted by running the survey during the final weeks of the winter term and into the exam period when student time was also under multiple demands. Our findings must be interpreted with care as this research was highly context specific.

Conclusion

STAR is a student AIG that allows students to engage with one another while also connecting with academics, working professionals and older adult community members. In summary, our study found that students interested in aging represent a very diverse group, that students learned about our AIG from their professors rather than other sources, and we had higher rates of attendance during the pandemic year with online meetings. A major highlight was that attendance was based more on student availability than meeting topic; AIGs and other student interest groups should consider students’ schedules as much as possible to enhance engagement. We encourage the development of AIGs at other institutions that foster interdisciplinary learning and interaction outside of the more traditional fields of social gerontology and geriatric health professions; such efforts may help cultivate increased interest in aging among the student body and help shape a more age-friendly future.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Dr. Michelle Porter, Director of the Centre on Aging at the University of Manitoba, and Centre staff Rachel Ines and Nicole Dunn, for their supervision and support

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Participating faculties are: Agricultural and Food Sciences, Arts, Kinesiology and Recreation Management, Social Work, and the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences including the Max Rady College of Medicine and the College of Nursing.

2. There were no graduate-level aging courses on offer during the term.

References

- Algoso, M., Peters, K., Ramjan, L., & East, L. (2016). Exploring undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of working in aged care settings: A review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 36, 275–280. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2015.08.001

- Andrews, G., Campbell, L., Denton, M., & McGilton, K. (2009). Gerontology in Canada: History, challenges, research. Ageing International, 34(3), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-009-9042-7

- Blachman, N. L., Blaum, C. S., & Zabar, S. (2021). Reasons geriatrics fellows choose geriatrics as a career, and implications for workforce recruitment. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 42(1), 38–45. doi:10.1080/02701960.2019.1604341

- Boscart, V., McCleary, L., Huson, K., Sheiban, L., & Harvey, K. (2017). Integrating gerontological competencies in Canadian health and social service education: An overview of trends, enablers, and challenges. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 38(1), 17–46. doi:10.1080/02701960.2016.1230738

- Cammer Paris, B. E. (1998). The development of a medical student interest group in Geriatrics. Educational Gerontology, 24(3), 199–205. doi:10.1080/0360127980240301

- Dahlke, S., Kalogirou, M. R., & Swoboda, N. L. (2021). Registered nurses’ reflections on their educational preparation to work with older people. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 16(2), e12363. doi:10.1111/opn.12363

- Flores-Sandoval, C., Sibbald, S., Ryan, B. L., & Orange, J. B. (2021). Interprofessional team-based geriatric education and training: A review of interventions in Canada. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 42(2), 178–195. doi:10.1080/02701960.2020.1805320

- Glauser, W. (2019). Lack of interest in geriatrics among medical trainees a concern as population ages. Cmaj, 191(20), E570–E571. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-5752

- Gray, D. L., & Walker, B. A. (2015). The effect of an interprofessional gerontology course on student knowledge and interest. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 33(2), 103–117. doi:10.3109/02703181.2015.1006349

- Hannon, J., Hocking, C., Legge, K., & Lugg, A. (2018). Sustaining interdisciplinary education: Developing boundary crossing governance. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(7), 1424–1438. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1484706

- Hebditch, M., Daley, S., Wright, J., Sherlock, G., Scott, J., & Banerjee, S. (2020). Preferences of nursing and medical students for working with older adults and people with dementia: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 92. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02000-z

- Holmes, S. D., Smith, E., Resnick, B., Brandt, N. J., Cornman, R., Doran, K., & Mansour, D. Z. (2020). Students’ perceptions of interprofessional education in geriatrics: A qualitative analysis. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 41(4), 480–493. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1500910

- Jones, K. J., Vandenberg, E. V., & Bottsford, L. (2011). Prevalence, formation, maintenance, and evaluation of interdisciplinary student aging interest groups. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 32(4), 321–341. doi:10.1080/02701960.2011.618958

- Kahu, E. (2014). Increasing the emotional engagement of first year mature-aged distance students: Interest and belonging. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 5(2), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v5i2.231

- Lawrence, A. R., Jarmanrohde, L., Dunkle, R. E., Campbell, R., Bakalar, H., & Li, L. (2003). Student pioneers and educational innovations. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 39(1–2), 91–110. doi:10.1300/J083v39n01_09

- Lee, K., & Richardson, V. E. (2020). Geriatric community health workers’ views about aging, work, and retirement: Implications for geriatrics and gerontology education. Educational Gerontology, 46(2), 47–58. doi:10.1080/03601277.2019.1710043

- Louw, A., Turner, A., & Wolvaardt, L. (2018). A case study of the use of a special interest group to enhance interest in public health among undergraduate health science students. Public Health Reviews, 39(1), 11. doi:10.1186/s40985-018-0089-4

- Lun, M. W. (2012). Students’ knowledge of aging and career preferences. Educational Gerontology, 38(1), 70–79. doi:10.1080/03601277.2010.500584

- Mcquown, C., Ahmed, R. A., Hughes, P. G., Ortiz-Figueroa, F., Drost, J. C., Brown, D. K. … Hazelett, S. (2020). Creation and implementation of a large-scale geriatric interprofessional education experience. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2020, e3175403. doi:10.1155/2020/3175403

- Meisner, B. A., Boscart, V., Gaudreau, P., Stolee, P., Ebert, P., Heyer, M. … Wilson, K. (2020). Interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches needed to determine impact of Covid-19 on older adults and aging: CAG/ACG and CJA/RCV joint statement. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 39(3), 333–343. doi:10.1017/S0714980820000203

- Miller, V. J., Murphy, E. R., Cronley, C., Fields, N. L., & Keaton, C. (2019). Student experiences engaging in interdisciplinary research collaborations: A case study for social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(4), 750–766. doi:10.1080/10437797.2019.1627260

- Obhi, H. K., & Woodhead, E. L. (2016). Attitudes and experiences with older adults: A case for service learning for undergraduates. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 37(2), 108–122. doi:10.1080/02701960.2015.1079704

- Perrella, A., Cuperfain, A. B., Canfield, A. B., Woo, T., & Wong, C. L. (2020). Do interest groups cultivate interest? Trajectories of geriatric interest group members. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 23(3), 264–269. doi:10.5770/cgj.23.413

- Pfirman, S., & Martin, P. J. S. (2017). Facilitating interdisciplinary scholars. In R. Frodeman (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198733522.013.47

- Schapmire, T. J., Head, B. A., Nash, W. A., Yankeelov, P. A., Furman, C. D., Wright, R. B. … Faul, A. C. (2018). Overcoming barriers to interprofessional education in gerontology: The interprofessional curriculum for the care of older adults. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 9, 109–118. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S149863

- Solberg, L. B., Carter, C. S., & Solberg, L. M. (2019). Geriatric care boot camp series: Interprofessional education for a new training paradigm. Geriatric Nursing, 40(6), 579–583. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.05.010

- Stetten, N. E., Black, E. W., Edwards, M., Schaefer, N., & Blue, A. V. (2019). Interprofessional service learning experiences among health professional students: A systematic search and review of learning outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 15, 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.xjep.2019.02.002

- Thompson, S., Metcalfe, K., Boncey, K., Merriman, C., Flynn, L. C., Alg, G. S. … Beale, J. (2020). Interprofessional education in geriatric medicine: Towards best practice. A controlled before–after study of medical and nursing students. BMJ Open, 10(1), e018041. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018041

- University of Manitoba. (2021a). Aging (interfaculty option). https://umanitoba.ca/explore/programs-of-study/aging-interfaculty-option

- University of Manitoba. (2021b). Facts and Figures. http://www.umanitoba.ca/factsandfigures

- Van Dussen, D. J., & Weaver, R. R. (2009). Undergraduate students’ perceptions and behaviors related to the aged and to aging processes. Educational Gerontology, 35(4), 342–357. doi:10.1080/03601270802612255

- Wesley, S. C. (2005). Enticing students to careers in gerontology. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 25(3), 13–29. doi:10.1300/J021v25n03_02

- Wister, A., Kadowaki, L., & Mitchell, B. (2016). Gerontology graduate training in North America: Shifting landscapes, innovation and future directions [Report]. https://summit.sfu.ca/item/16511. Accessed December 16, 2021