?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Reading literature contributes to the development of language skills and socioemotional competencies related to empathic responding. Despite implications for improving measures of empathy used by practitioners interested in reading behavior and their applications to teaching empathic skills through literature, extensions to the ability to express empathic inference of interpersonal encounters, or empathic accuracy, remains an understudied area. Comparing which traits are associated with performance on tasks that require empathic accuracy could reveal more about underlying empathic processes and their characteristics for the benefit of practitioner tools and pedagogical choices for reading. Two studies were conducted to investigate possible relationships between self-reported constructs of interpersonal reactivity and an experimental paradigm that measures empathic accuracy. Experiment 1 investigated these relationships among participants having everyday conversations, and Experiment 2 examined the same variables in a context designed to emulate a counseling setting. In both cases, scores on the Fantasy self-report scale correlated with empathic accuracy scores. The results indicate that a tendency to consume fiction and engage in narrative transportation might play a role in the ability to accurately infer the internal state of others. Implications for reader involvement as learner engagement and consequential validity for instructional scaffolds are discussed.

Introduction

The act of reading requires processes like the perceptual reception of features with global and local fixation strategies (Leung, Mikami, & Yoshikawa, Citation2019), integrative steps of orthographic recognition for lexical access (Morton & Sasanuma, Citation1984), and the formation of schema for comprehending abstract entities and concepts (Carrell & Eisterhold, Citation1983). Reading is especially fundamental to the four skills of language learning, exemplified in studies on extensive reading that have made headway as an approach to proficiency and marker of progress in vocabulary acquisition and recall (McLean, Stewart, & Batty, Citation2020). When sustained, reading behavior underpins self-regulation processes and working memory for reading skill development among foreign language beginners (Sagarra, Citation2017), the retention of learned word forms in interpretative reading (Rose & Harbon, Citation2013), and numerous downstream factors of learner motivation, such as reading curiosity, challenge, compliance, efficacy, and, crucially, involvement, or the engagement garnered from reading stories in the target language (Mori, Citation2002).

Literature benefits the teaching of language by dint of providing authentic contextualization that both attenuates the role and embeddedness of social factors in thick descriptions and frames them in depictions of the human condition (Hadaway, Vardell, & Young, Citation2002). As cited in Seelye (Citation1984), dating back to Marquardt (Citation1969), reading literature has been used as a sensitizing method for the formation of empathy, even described as “a desired end-product of learning” (p. 67). Fiction, in particular, is characterized by pleasurable motivational salience and interest on the part of learners who experience the exploratory rush of worldbuilding and observe the dramaturgical interplay of members in the throes of different life circumstances. This might be attributed to the propulsive translocation that occurs through language to edify our common understanding, raising consciousness of multiple perspectives and providing substrates for critical thinking and discussion (Leo, Citation2010). This tendency is thought to be effective when leveraged in literature courses that opt for pedagogical choices that emphasize learner engagement of new literacies and intercultural encounters, as “the ability to enter a literary world may be akin to the ability to enter another culture” (Seelye, Citation1984, p. 276). Overall, literature is hypothesized as a means of vicarious intergroup contact (Belet, Citation2018) and route to empathic development, even finding applications in clinical settings (Campo, Citation1998; Mast & Ickes, Citation2007), but requiring refinement as a pedagogical tool (Paran, Citation2008).

Empathy expressed for real people has been shown to bear similarities to that for fictional characters (Nomura & Akai, Citation2012) across several empirical studies, which have found that frequent readers of fiction are highly sensitive social decoders (Mar, Oatley, Hirsh, Paz, & Peterson, Citation2006). In fact, a meta-analysis by Dodell-Feder and Tamir (Citation2018) determined that reading fiction leads to the performance of social cognition in instances of mindreading. However, previous studies have often used questionnaires limited to capturing the levels of empathy that respondents can recognize within themselves (Bal & Veltkamp, Citation2013; McCreary & Marchant, Citation2017) or behavioral tasks of “mindreading ability” that do not account for the actual internal states of the depicted individuals (e.g., the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; Baron-Cohen, Jolliffe, Mortimore, & Robertson, Citation1997). The issue of whether reading materials such as fiction can cultivate accurate inferences about the internal state of individuals portrayed in interpersonal interactions could be considered a basic assumption and empirical question related to the real-world encounters of socioemotional importance that color our daily lives, which are subsequently drawn upon for the inferences and critical thinking exercises used for comprehension, visualization, and learner engagement in reading activities. Thus, the current study aims to address this core assumption and question with an established paradigm for social inference and an established inductive summary for the trait tendency to read fiction with frequency and aplomb.

Empathic accuracy (EA) is the ability for a person to accurately infer the internal state of another person interacting in an interpersonal encounter (Ickes, Citation2001; Ickes & Hodges, Citation2013). While conceptually interchangeable with descriptions of theory of mind and mindreading, the term “empathic accuracy” characterizes the properties of the measurement paradigm and the motivational tendency to express empathy rather than the capacity to do so (Hollan, Citation2012). The EA measurement paradigm by Ickes and colleagues is one of the most frequently used experimental techniques in this regard (Ickes, Citation2001; Ickes, Stinson, Bissonnette, & Garcia, Citation1990; Marangoni, Garcia, Ickes, & Teng, Citation1995). It compares the degree of correspondence between the stated or expressed internal experience of an actor modeling an interaction at a given moment in time, called a target participant, with the stated or expressed inference of an onlooker, known as a perceiver. The approach possesses high ecological validity as it allows for the matching of observer inferences with the actual internal states of the participants serving as targets. In addition, EA is crucially tied to gauging the objects of desire in interpersonal encounters for subsequently behaving in an altruistic manner. For example, if the chance to offer words of comfort to someone looking forlorn were to present itself, accurate inference of the internal states of the interlocutor would be clearly desired as a matter of relationship regulation. However, open research questions remain for EA and related traits in ways that have left the process that gives rise to EA elusive (Ickes, Citation2016).

Trait-relevant factors of cognitive and affective empathy are assumed to be available to self-report and effective, straightforward predictors of EA given their shared conceptual underpinnings. Acting with cognitive empathy describes a process where an onlooker can take the perspective of a target without necessarily experiencing any emotional change, and the process of experiencing affective empathy is considered unintentional and uncontrollable with onlookers feeling the same emotions as targets (Davis, Citation2006). To capture trait empathy, Davis (Citation1980) developed the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), the most widely operationalized instrument for inductive summaries on the facets of empathy (Decety & Ickes, Citation2011). The IRI consists of four dimensions: Empathic Concern, or the tendency for a respondent to have sympathy for another person’s negative experiences; Perspective Taking, which reflects the tendency to see things from another person’s point of view; Personal Distress, which measures the tendency for a person to engage in vicarious experiences of distress when they observe the negative experiences of others; and the Fantasy, which represents the tendency for a person to insert or replace themselves with the characters in a fictional story (Davis, Citation1980). The factor for Perspective Taking has been shown to encompass components of cognitive empathy, while the factors of Empathic Concern and Personal Distress have been considered components of affective empathy (Israelashvili, Sauter, & Fischer, Citation2020). However, previous findings have not consistently observed relationships between EA and trait-level cognitive or affective empathy (e.g., Ickes, Gesn, & Graham, Citation2000; Laurent & Hodges, Citation2009; Stinson & Ickes, Citation1992). As illustrated by Gleason, Jensen-Campbell, and Ickes (Citation2009), neither cognitive nor affective empathy were significantly related to the performance of EA in children. Extending to reports with other groups, trait-level cognitive and affective empathy measured via questionnaires have so far failed to reliably predict EA in experimental settings (Hodges, Lewis, & Ickes, Citation2015). A recent meta-analysis also provided few relationships between trait cognitive and affective empathy, and EA (Murphy & Lilienfeld, Citation2019). A possible reason for the discrepancy between trait-relevant self-reports of cognitive/affective empathy and EA is that perceivers may lack insight (or metaknowledge) into their own relative level of empathic skill (Dunning, Johnson, Ehrlinger, & Kruger, Citation2003; Ickes, Citation1993).

A selective pattern for the relevant factors as trait contributions in prior literature narrow the scope of hypothesis formation. Although previous studies have failed to show that EA covaries with trait empathy in terms of Perspective Taking and Empathic Concern, hypotheses for the Fantasy subscale remain intact for predicting EA performance due to consistent results from the evidence base of empirical studies. Nussbaum (Citation1995) proposed that processing of the fictional world actively develops a form of imaginative thinking and feeling toward others. Myers and Hodges (Citation2009) similarly suggested that accurate inference on the EA task could be caused by invoking imagined representations. As Fantasy relates to familiarity with fiction, which has also correlated with a fondness for fiction (Nomura & Akai, Citation2012), it may induce high performance on the EA task, as suggested by Nussbaum (Citation1995). In fact, many previous findings supported the idea that high consumption of and proximity to fiction fosters the representations of how other people think and feel. Lee, Guajardo, Short, and King (Citation2010) showed that Fantasy was positively correlated with the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test, which requires matching an emotion label with the eyes of a target. Mar et al. (Citation2006) also revealed that exposure to fiction facilitated performance on the Interpersonal Perception Task, which requires multiple-choice questions to describe the interaction depicted in a scene. Reading fiction led to better performance on tests such as the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test across five experiments (Kidd & Castano, Citation2013) and recent evidence indicated a correlation between Fantasy and cognitive empathy components of the Multifaceted Empathy Test, asking participants to match emotion labels with facial displays (Drimalla, Landwehr, Hess, & Dziobek, Citation2019). Goldstein, Wu, and Winner (Citation2009) further supported this perspective by showing that adolescent and adult actors who adopt the perspective of multiple characters were skilled at reading the mental states of others. Accordingly, it can be assumed that Fantasy, or the tendency to insert oneself with the characters in a fictitious story, could be within the bounds of EA more than other trait-level factors of cognitive and affective empathy.

As an assertion common to the benefits of reading, fiction might be described as a route to or form of simulation that runs on minds and enables complex interactions in the social world. The theory for the simulation of social worlds has been carefully proposed and could form a basis for effects between improved EA and active engagement with fiction (Mar, Djikic, & Oatley, Citation2008; Oatley, Citation2016). Neuroanatomical evidence also supports the notion that fictional arcs induce a proxy simulation of events in the story world that concurrently represent, relate, or accord to the activities of the character(s) in question. When readers visualize a story that characters perform, different brain regions mirror brain responses that similarly occur in real-world activities (Speer, Reynolds, Swallow, & Zacks, Citation2009). Thus, it is plausible that literary simulations via Fantasy help us to improve our understanding of others. If true, this link could provide clues to the process of empathic accuracy and justify the use of fictional literature and reading in training for socioemotional competence, as desired by pedagogical (Williams, Citation2013) and clinical applications (Campo, Citation1998; Charon, Citation2008; Mast & Ickes, Citation2007).

Taken together, it is necessary to reexamine the relationships between the self-reported traits of empathy and their expression via EA for the benefit of measures used in applied settings. Based on the pattern of possible relationships for trait empathy and quasi-mindreading performance as stated in previous research, EA would be expected to be associated with the factor of Fantasy over other factors such as Perspective Taking and Empathic Concern. Our study reports on these relationships in two experimental settings. Experiment 1 investigated these relationships for targets engaging in everyday conversations, and Experiment 2 further examines the same variables in a context designed to emulate a counseling setting. A hierarchical linear model was used to account for perceiver and target differences included in the EA paradigm. We hypothesized that Fantasy, as reported by perceivers, would be associated with better empathic accuracy. The current study also hypothesized that self-reported cognitive/affective empathy would fail to show relationships with EA. In addition, we expected that investigating EA using different situations across two experiments would more securely establish the idea that proximity to fiction fosters the representations of how other people think and feel, and bolster the generalization and consequential aspects in Messick’s unified view of construct validity (Messick, Citation1995).

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 was conducted to investigate the relationships between the self-reported traits of empathy and the empathic accuracy derived from the EA paradigm under the conditions of an everyday conversation about an emotional event, as such conditions were expected to represent the phenomenon as an occurrence experienced commonly on a daily basis.

Method

Participants (Perceivers)

In Experiment 1, thirty-one Japanese university students (N = 31) participated in this study as perceivers (17 females; M age (SD) = 21.97 (1.43)). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the investigation in line with a protocol approved by the Ethical Committee of Hiroshima University. They were given a monetary compensation of 500 yen after the experiment.

Video Stimulus (Targets)

Experiment 1 used the video clips of seven target persons (4 females, M age (SD) = 22.43 (1.18)) who were videotaped discussing a recent emotional event with a male experimenter. After being videotaped, each target watched their own video, which lasted 2 minutes 30 seconds. They described what he or she was experiencing during the previously recorded film clip of their discussion on a form and marked the time that the thought or feeling occurred. Targets were allowed to start, pause, or replay the recorded clips of their own reactions during the conversation as needed. Instances where the target recalled a specific thought or feeling during the video were varied. Written informed consent was obtained from each target before the experiment in line with a protocol approved by the Ethical Committee of Hiroshima University. The participants who served as targets were given a monetary compensation of 2,000 yen after the experiment.

Procedures

Experiment 1 let the participants evaluate the clips of the target internal statements using the thought-feeling recording forms with the time marked as was done by targets in the stimulus procurement phase. Experiment 1 used all seven clips. The order of the clips for the targets was randomized. The participants then filled out the Japanese version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI: Davis, Citation1980; Himichi et al., Citation2017). depicts the descriptive statistics for the IRI in Experiment 1 as average scores of the items. also shows that the correlated pair of greatest magnitude, Empathic Concern and Perspective Taking, did not reach a threshold above chance level (|r| < 0.32, p > .09).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the IRI in the two experiments.

Table 2. Correlation matrix of the IRI for the two experiments.

Referring to the procedures in previous studies (Marangoni et al., Citation1995), EA was computed per the agreement between target-generated thought-feeling entries and perceiver-generated thought-feeling entries. Two raters compared the content of each actual and inferred thought-feeling entry and rated the degree of similarity along three response options ranging from 0 (essentially different content), through 1 (similar, but not the same content), to 2 (essentially the same content; Ickes, Citation2001). To ensure reliability, an index of interrater agreement was calculated, which was found to be sufficiently high (Experiment 1: weighted κ = 0.78, p < 0.001).

In keeping with open science practices that emphasize the transparency and replicability of results, all data have been made available online as supplementary material (https://osf.io/k3v6h/?view_only=40782b7f2d944d6fbff0bd46419e79e3).

Statistical Analysis

In order to clarify the relationships between self-reported traits of empathy and empathic accuracy, a hierarchical linear model was conducted to control for the differences between each perceiver and target. In addition, we adopted a Bayesian approach to evaluate uncertainty as probability distributions. The models for EA were described as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

All predictors were standardized for the interpretation of coefficients. Results were obtained using R (4.0.2, R Core Team, Citation2020), specifically the brms packages (Bürkner, Citation2018). All iterations were set to 2,000 and burn-in samples were set to 1,000, with the number of chains set to four. All priors were kept at the default settings for the brm function. The value of R-hat for all parameters equaled 1.0, indicating convergence across the four chains (Stan Development Team, Citation2020).

Results

In order to clarify the relationships between self-reported trait empathy and empathic accuracy, a Bayesian hierarchical linear model with random intercepts was conducted to control for the differences between each perceiver and target. For more conservative tests, we examined intra-class correlations for evaluation of random effects, reported the variance inflation factor (VIF) to check for multicollinearity and posterior predictive checks to verify model validity.

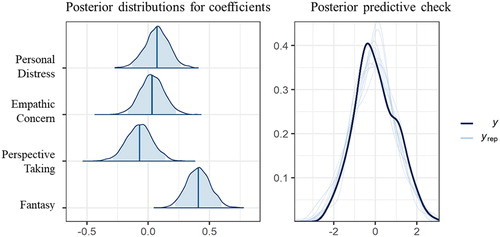

After checking the ICCs for each random effect (perceivers = 0.17; target = 0.07), we conducted a model that controlled the random effects for perceivers. and depict the coefficients for each factor of trait empathy predicting EA performance and posterior predictive check. Notably, Fantasy was found to predict EA (β = 0.41, 95% Credible Intervals = [0.22, 0.60]), but all other predictors including Perspective Taking and Empathic Concern did not due to 95% CIs that included zero. The group effects in Experiment 1 suggest that perceivers were a source of strong random effects (SD (perceiver) 95% Credible Intervals = [0.20, 0.60]). Furthermore, post-hoc sensitivity power analysis using the simr package (Green & MacLeod, Citation2016) indicated that this sample size was sufficient to detect a standardized regression coefficient of |β| = 0.40 for Fantasy in mixed models with a significance level of α = 0.05 and 99% power. All VIFs were less than 5 (VIFs < 1.36), indicating a low correlation of predictors with each other.

Figure 1. Posterior distributions of each coefficient for EA in Experiment 1 (left). Blue bars are expected a posteriori values and blue transparencies stand for 95% credible intervals. Posterior predictive check for the current model from Experiment 1 (left). The empirical distribution of data (y) was compared to the distributions of individual simulated datasets (yrep).

Experiment 2

Building on the results of Experiment 1, Experiment 2 was conducted to examine relationships derived from the EA paradigm under a similar disclosure of an emotional event in the context of a counseling situation. We reasoned that conditions that involved the discussion of private problems would constitute a situation that was common and important to applied settings. Experiment 2 hypothesized that empathic accuracy would be associated with Fantasy but not other self-reported cognitive/affective empathy factors, consistent with Experiment 1.

Method

Participants (Perceivers)

In Experiment 2, forty-four Japanese university students (N = 44) participated in this study as perceivers (26 females; M age (SD) = 21.11 (1.24)). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the investigation in line with a protocol approved by the Ethical Committee of Hiroshima University. They were given a monetary compensation of 500 yen after the experiment.

Video Stimulus (Targets)

Experiment 2 used the video clips of six target persons (3 females, M age (SD) = 22.33 (1.51). The targets were videotaped while they discussed private problems (e.g., academic problems or future career) for 30 minutes with a licensed male therapist in clinical psychology. After being videotaped, all targets performed the same procedures as Experiment 1. Written informed consent was obtained from each target before the investigation of both experiments in line with a protocol approved by the Ethical Committee of Hiroshima University. The target participants were given a monetary compensation of 2,000 yen after the experiment.

Procedures and Statistical Analysis

We implemented the same procedure as Experiment 1 except for the number of stimuli. Perceivers in Experiment 2 watched only two clips because of time restrictions. An index of interrater agreement was calculated and shown to be sufficiently high (Experiment 2: weighted κ = 0.83, p < 0.001). shows the descriptive statistics for the IRI in Experiment 2 as the average scores of items. Similar to Experiment 1, there were no significant correlations for the IRI sub-factors (|r| < .22, p > .15: ).

Results

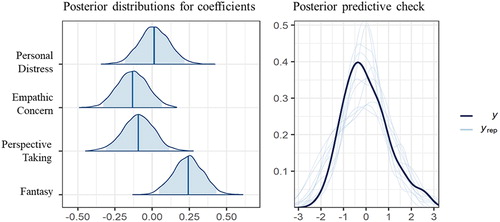

After checking ICCs for each random effect (perceivers = 0.08; target = 0.18), we performed a model controlling for the random effect of targets. Coefficients for each factor of trait empathy predicting EA performance for Experiment 2 are shown in and . Consistent with Experiment 1, Fantasy was found to predict EA (β = 0.24, 95% Credible Intervals = [0.04, 0.45]). However, all other predictors including Perspective Taking and Empathic Concern did not predict the performance of EA due to 95% CIs that included zero. The group effects for Experiment 2 represent strong variances for targets (SD (target) 95% Credible Intervals = [0.18, 1.70]). The post-hoc sensitivity power analysis indicated that this sample size was moderately sufficient to detect a standardized regression coefficient of |β| = 0.24 for Fantasy in mixed models with a significance level of α = 0.05 and 68% power. All VIFs were less than 5 (VIFs < 1.09), indicating a low correlation for predictors with each other.

Figure 2. Posterior distributions of each coefficient for EA in Experiment 2 (left). Blue bars are expected a posteriori values and blue transparencies stand for 95% credible intervals. Posterior predictive check for the current model from Experiment 2 (left). The empirical distribution of data (y) was compared to the distributions of individual simulated datasets (yrep).

Table 3. Results of the hierarchical linear models for two experiments.

General Discussion

This study investigated EA with two types of targets and accounted for the alignment of traits of empathy as a way to match behavioral indicators of interest to practitioners. Consistent with the simulation of social worlds that is posited to occur when reading fictional narratives (Oatley, Citation2016), Fantasy predicted EA performance but other trait empathy factors such as Perspective Taking or Empathic Concern did not. The two experiments showed that EA was related to Fantasy over other self-reported traits of cognitive empathy and affective empathy as predicted via synthesis with prior studies (Mar et al., Citation2006; Kidd & Castano, Citation2013; Hollan, Citation2012; Djikic, Oatley, & Moldoveanu, Citation2013). These results clarify the relationship between empathic inference as an expression of socioemotional ability and tendencies in reading behavior often promoted in literature-based and extensive reading curricula for empathic development.

The most interesting finding from this study is that the Fantasy subscale of the IRI was the strongest predictor of EA through two experiments. This result suggests that the target was treated by the perceiver as a fictional character. The Fantasy construct represents a tendency to insert oneself into the characters in a fictitious story (Davis, Citation1980), but has also been found to be significantly related to the fondness for fiction generally (Nomura & Akai, Citation2012). Therefore, it may be easier for people who have high tendency for Fantasy to become familiar with or engage with fiction in a manner similar to the presentation of narrative circumstances depicted in clips. This interpretation accords with a finding from a brain imaging study that revealed that Fantasy is associated with the potential to process and retrieve allocentric information from autobiographical memories related to a character as the subject of interaction (Cheetham, Hänggi, & Jancke, Citation2014). Following this line of reasoning, one interpretation of our results could be that empathic accuracy is involved in an active evaluation and application of pattern matching between current target-observer circumstances with past experiences encountered in fictional worlds. This would suggest that Fantasy might expand one’s repertoire of available representations in the tractable manner of consuming fiction and gaining literacy about human socioemotional circumstances.

In contrast, Stinson and Ickes (Citation1992) showed that Fantasy was negatively correlated with EA, which is inconsistent with the present findings. However, the participants (perceivers) of that study engaged in a direct conversation with the target in the dyadic interaction paradigm before doing the EA task, and such experiences might affect the nature of EA. In other words, engaging in direct interactions with a target may change the perceiver’s view of the target in a way that does not see them as a fictional character. Thus, it may be useful to investigate EA and the influence of direct experiences with the target in more controlled laboratory settings. Although Gleason et al. (Citation2009) used child perceivers, our finding with adults supports their report which revealed a positive relationship between EA and the Fantasy subscale of the IRI under the standard stimulus paradigm. Overall, our study showed that empathic accuracy may be predicted by the trait tendency to insert oneself into the mind of the target, namely through the narrative transportation associated with fantasy.

The use of literary fiction and narrative knowledge has long been a subject of attention to scholars and practitioners (e.g., Mast & Ickes, Citation2007; Charon, Citation2008), but also in contemporary work from the realm of development and education. Reading fictional stories is thought to promote academic achievement and social development (McCreary & Marchant, Citation2017), as well as improvement of intergroup attitudes, reduction in stereotyping, greater degrees of positive intergroup behavioral intentions, and an increased desire to engage in future contact (Vezzali, Stathi, & Giovannini, Citation2012). In an example account of applications that favor literary activity as a program target, Schutt, Deng, and Stoehr (Citation2013) evaluated the rehabilitative outcomes of participating in probation programs that implemented bibliotherapy and found a decrease in the rate of recidivism and offense severity for participants in comparison to a randomized group of probationers as a control (e.g., Zaki, Citation2020). The positive psychological effects of consuming Fiction are increasingly coming into purview, and our findings serve as incremental evidence for a relationship between empathic accuracy and the tendency to insert oneself into the characters in a fictitious story in two accounts of ecologically valid situations (everyday conversations and semi-counseling settings). In this manner, the EA paradigm might be a useful research platform for empirical studies of behavioral experiments that intersect with reading, fiction, and interpersonal variables, and this finding might be useful for practitioners who aim to apply empathic accuracy or the IRI to educational and clinical settings (e.g., Mast & Ickes, Citation2007).

Our findings also have implications for reader involvement as learner engagement via the pedagogical use of film adaptations as visual aids for the contextualization of reading material and instructional scaffolds for reflective practice assignments. Consuming reading materials from different registers activates lexical skills but can be difficult for students early in their proficiency (Paran, Citation2008). Thus, pedagogical techniques for lesson planning rely on tools such as visual aids to enhance the resolution and comprehension of reading material by coupling it with the richness of film adaptations for literature classes, especially for period pieces with sociohistorical significance, and reflective learning assignments are used to personalize and contextualize past circumstances with experiences relating to the author’s intentions or the character’s circumstances. Approaches such as these create space for critical thinking and engagement with the text as they require readers to visualize real or imagined scenarios, call upon their experienced circumstances, and use empathic inference to demonstrate comprehension. While more work is necessary, one interpretation of our findings is that the Fantasy factor of the IRI and expression of empathic inference measured by EA could be used to improve the consequential validity of tools for empathic development in structured syllabi for reading and literacy courses, as desired areas of extension and refinement (Paran, Citation2008). Additionally, such investigations could provide empirical evidence for pedagogical approaches that leverage meta-awareness about the self or historical others as the subject matter for reflective learning and socioemotional and intercultural competency development (Williams, Citation2013). Our approach could also plausibly couple with formal or informal assessments of the multimodal and multidirectional dyadic interactions of digital reading paths (Simpson, Walsh, & Roswell, 2013). Thus, future studies might consider the IRI and the EA paradigm as experimental methods to improve our understanding of the connections between literature, reading, and empathic processes and strengthen the justification of pedagogical choices or tools used for skills development in reading, socioemotional competence, and intercultural awareness.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, Fantasy, as a tendency measured psychometrically, is a more indirect indicator of reader consumption when compared to more detailed or probing behavioral questions about the breadth or depth of reading materials, considerations of fandom or commitment, or genre preferences for works of fiction, as examples. Thus, this finding did not provide straightforwardly prescriptive evidence that reading fictional literature is a directly trainable method to improve empathic inference. However, we contend that the current study did shed light on descriptive evidence that a factor that summarizes a key tendency in reader profiles could predict more accurate behavioral performance of empathic inference, suggesting that further studies could prove beneficial for practical settings. These might take the form of methods to assess the relationship between textual material presented in case vignettes and role plays that are visually presented in a dynamic medium or enacted in real-time, or applications to observations of reading paths from affordances in haptic learning (Simpson et al., 2013) and materials related to visual literacy skills in education, such as TPCK (Angeli & Valanides, Citation2009). Second, generalizing the observed results is difficult due to possible cultural differences from our sample of participants. Asian perceivers, for instance, reportedly pay more attention to distinct expressive information from the eyes than Western perceivers, who focus more on the areas around the mouth (Jack, Citation2013), indicating that there may be cultural factors at play in the ways that some individuals obtain social information when observing others. Morling, Kitayama, and Mitamoto (2002) also showed that Japanese participants, relative to other populations, are purportedly more likely to be involved in situations that feature making adjustments to accommodate the relational needs or circumstances of others. Such findings suggest that there might be noteworthy cultural differences in examinations of social situations. Thus, future studies remain necessary to carefully take these cultural factors into account. Finally, while robustness was confirmed by the results of two experiments providing the same relationships, a larger sample size of study participants could provide for an even more robust understanding of the effects.

In sum, the experiments in this report revealed that an individual’s tendency for Fantasy might be able to determine their ability to accurately read or infer the content of another person’s thoughts and feelings. Consistently corroborating empathic accuracy as an ability with the narrative transportation tied to Fantasy with further investigations may be a viable means to establish relationships between the trait and performance of empathy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Angeli, C., & Valanides, N. (2009). Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT–TPCK: Advances in technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). Computers & Education, 52(1), 154–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.07.006

- Bal, P. M., & Veltkamp, M. (2013). How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation on the role of emotional transportation. PloS One, 8(1), e55341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055341

- Baron-Cohen, S., Jolliffe, T., Mortimore, C., & Robertson, M. (1997). Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(7), 813–822.

- Belet, M. (2018). Reducing interethnic bias through real-life and literary encounters: The interplay between face-to-face and vicarious contact in high school classrooms. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 63, 53–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.01.003

- Bürkner, P. C. (2018). Advanced Bayesian Multilevel Modeling with the R Package brms. The R Journal, 10(1), 395–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-017

- Campo, R. (1998). The desire to heal: A doctor's education in empathy, identity, and poetry. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Carrell, P. L., & Eisterhold, J. C. (1983). Schema theory and ESL reading pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 17(4), 553–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3586613

- Charon, R. (2008). Narrative medicine: Honoring the stories of illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cheetham, M., Hänggi, J., & Jancke, L. (2014). Identifying with fictive characters: Structural brain correlates of the personality trait “fantasy. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(11), 1836–1844. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst179

- Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS: Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 1–17.

- Davis, M. H. (2006). Empathy. In J. E. Stets & J. H. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of emotions (pp. 443–466). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Decety, J., & Ickes, W. (2011). The social neuroscience of empathy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Djikic, M., Oatley, K., & Moldoveanu, M. C. (2013). Reading other minds: Effects of literature on empathy. Scientific Study of Literature, 3(1), 28–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.3.1.06dji

- Dodell-Feder, D., & Tamir, D. I. (2018). Fiction reading has a small positive impact on social cognition: A meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(11), 1713–1727. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000395

- Drimalla, H., Landwehr, N., Hess, U., & Dziobek, I. (2019). From face to face: The contribution of facial mimicry to cognitive and emotional empathy. Cognition & Emotion, 33(8), 1615–1672. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1596068

- Dunning, D., Johnson, K., Ehrlinger, J., & Kruger, J. (2003). Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 83–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01235

- Gleason, K. A., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., & Ickes, W. (2009). The role of empathic accuracy in adolescents' peer relations and adjustment. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(8), 997–1011. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209336605

- Goldstein, T. R., Wu, K., & Winner, E. (2009). Actors are skilled in theory of mind but not empathy. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 29(2), 115–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/IC.29.2.c

- Green, P., & MacLeod, C. J. (2016). SIMR: An R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(4), 493–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12504

- Hadaway, N. L., Vardell, S. M., & Young, T. A. (2002). Literature-based instruction with English language learners, K-12. Boston: Allyn & Bacon Longman.

- Himichi, T., Osanai, H., Goto, T., Fujita, H., Kawamura, Y., Davis, M. H., & Nomura, M. (2017). Development of a Japanese version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Shinrigaku Kenkyu : The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 88(1), 61–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.88.15218

- Hodges, S. D., Lewis, K. L., & Ickes, W. (2015). The matter of other minds: Empathic accuracy and the factors that influence it. In P. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 319–348).Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Hollan, D. (2012). Emerging issues in the cross-cultural study of empathy. Emotion Review, 4(1), 70–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073911421376

- Ickes, W. (1993). Empathic accuracy. Journal of Personality, 61(4), 587–610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1993.tb00783.x

- Ickes, W. (2001). Measuring empathic accuracy. In J. A. Hall & F. J. Bernieri (Eds.), Interpersonal sensitivity: Theory and measurement (pp. 219–241). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Ickes, W. (2016). Empathic accuracy: Judging thoughts and feelings. In J. A. Hall, M. S. Mast, & T. V. West (Eds.), The social psychology of perceiving others accurately (pp. 52–70). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ickes, W., Gesn, P. R., & Graham, T. (2000). Gender differences in empathic accuracy: Differential ability or differential motivation? Personal Relationships, 7(1), 95–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2000.tb00006.x

- Ickes, W., & Hodges, S. (2013). Empathic accuracy in close relationships. In J. A. Simpson & L. Campbell (Eds.), Handbook of close relationships (pp. 348–373). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ickes, W., Stinson, L., Bissonnette, V., & Garcia, S. (1990). Naturalistic social cognition: Empathic accuracy in mixed-sex dyads. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 730–742. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.4.730

- Israelashvili, J., Sauter, D., & Fischer, A. (2020). Two facets of affective empathy: Concern and distress have opposite relationships to emotion recognition. Cognition & Emotion, 34(6), 1111–1112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1724893

- Jack, R. E. (2013). Culture and facial expressions of emotion. Visual Cognition, 21(9–10), 1248–1286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13506285.2013.835367

- Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science (New York, N.Y.), 342(6156), 377–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918

- Laurent, S. M., & Hodges, S. D. (2009). Gender roles and empathic accuracy: The role of communion in reading minds. Sex Roles, 60(5–6), 387–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9544-x

- Lee, S. A., Guajardo, N. R., Short, S. D., & King, W. (2010). Individual differences in ocular level empathic accuracy ability: The predictive power of fantasy empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(1), 68–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.016

- Leo, J. D. (2010). Education for intercultural understanding. Thailand: UNESCO Bangkok.

- Leung, C. Y., Mikami, H., & Yoshikawa, L. (2019). Positive psychology broadens readers’ attentional scope during L2 reading: Evidence from eye movements. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2245. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02245

- Marangoni, C., Garcia, S., Ickes, W., & Teng, G. (1995). Empathic accuracy in a clinically relevant setting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(5), 854–869. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.854

- Mar, R.A., Djikic, M., & Oatley, K. (2008). Effects of reading on knowledge, social abilities, and selfhood. In S. Zyngier, M. Bortolussi, A. Chesnokova, & J. Auracher (Eds.). Directions in empirical studies in literature: In honor of Willie van Peer (pp. 127–137). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., Hirsh, J., D., Paz, J., & Peterson, J. B. (2006). Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(5), 694–712. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.002

- Marquardt, W. F. (1969). Creating empathy through literature between members of the mainstream culture and disadvantaged learners of the minority cultures. The Florida FL Reporter, 7(1), 133–141.

- Mast, M. S., & Ickes, W. (2007). Empathic accuracy: Measurement and potential clinical applications. In T. Farrow & P. Woodruff (Eds.), Empathy in mental illness (pp. 408–427). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- McCreary, J. J., & Marchant, G. J. (2017). Reading and empathy. Reading Psychology, 38(2), 182–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2016.1245690

- McLean, S., Stewart, J., & Batty, A. O. (2020). Predicting L2 reading proficiency with modalities of vocabulary knowledge: A bootstrapping approach. Language Testing, 37(3), 389–411.

- Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons' responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. American Psychologist, 50(9), 741–749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.9.741

- Mori, S. (2002). Redefining motivation to read in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2), 91.

- Morling, B., Kitayama, S., & Miyamoto, Y. (2002). Cultural practices emphasize influence in the United States and adjustment in Japan. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 311–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202286003

- Morton, J., & Sasanuma, S. (1984). Lexical access in Japanese. In L. Henderson (Ed.), Orthographies and reading: Perspectives from cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and linguistics (pp. 25–42). London: Erlbaum.

- Murphy, B. A., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2019). Are self-report cognitive empathy ratings valid proxies for cognitive empathy ability? Negligible meta-analytic relations with behavioral task performance. Psychological Assessment, 31(8), 1062–1072.

- Myers, M. W., & Hodges, S. D. (2009). Making it up and making do: Simulation, imagination and empathic accuracy. In K. Markman, W. Klein, & J. Suhr (Eds.), The handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 281–294). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Nomura, K., & Akai, S. (2012). Empathy with fictional stories: Reconsideration of the fantasy scale of the interpersonal reactivity index. Psychological Reports, 110(1), 304–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/02.07.09.11.PR0.110.1.304-314

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Poetic justice: The literary imagination and public life. Boston, MA: Beacon.

- Oatley, K. (2016). Fiction: Simulation of social worlds. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(8), 618–628.

- Paran, A. (2008). The role of literature in instructed foreign language learning and teaching: An evidence-based survey. Language Teaching, 41(4), 465–496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480800520X

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/.

- Rose, H., & Harbon, L. (2013). Self‐regulation in second language learning: An investigation of the kanji‐learning task. Foreign Language Annals, 46(1), 96–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12011

- Sagarra, N. (2017). Longitudinal effects of working memory on L2 grammar and reading abilities. Second Language Research, 33(3), 341–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658317690577

- Schutt, R. K., Deng, X., & Stoehr, T. (2013). Using bibliotherapy to enhance probation and reduce recidivism. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 52(3), 181–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2012.751952

- Seelye, H. N. (1984). Teaching culture: Strategies for intercultural communication. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Co.

- Simpson, A., Walsh, M., & Rowsell, J. (2013). The digital reading path: Researching modes and multidirectionality with iPads. Literacy, 47(3), 123–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12009

- Speer, N. K., Reynolds, J. R., Swallow, K. M., & Zacks, J. M. (2009). Reading stories activates neural representations of visual and motor experiences. Psychological Science, 20(8), 989–999. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02397.x

- Stan Development Team. (2020). RStan: The R interface to Stan. R package version 2.21.2. Retrieved from http://mc-stan.org/.

- Stinson, L., & Ickes, W. (1992). Empathic accuracy in the interactions of male friends versus male strangers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(5), 787–797. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.62.5.787

- Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., & Giovannini, D. (2012). Indirect contact through book reading: Improving adolescents' attitudes and behavioral intentions toward immigrants. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 148–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20621

- Williams, T. R. (2013). Examine your LENS: A tool for interpreting cultural differences. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 22(1), 148–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.36366/frontiers.v22i1.324

- Zaki, J. (2020). The war for kindness: Building empathy in a fractured world. New York: Crown.