Abstract

The effectiveness of the Enhanced Assess, Acknowledge, Act (EAAA) program in reducing victimization and impacting other outcomes (mediators of program effects) was demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial. A planned analysis showed that program effects on sexual assault were not significantly different for survivors of completed rape and other women. The present article investigated whether the impact of EAAA on incidence of rape and attempted rape and on the mediators of EAAA’s effectiveness (e.g., situational risk detection, direct resistance, self-defense self-efficacy) was strengthened or weakened for women with a history of victimization (i.e., history of rape, attempted rape, or neither). EAAA’s impact on self-blame for women who experienced rape after program participation was also assessed. Data from 851 women who received either EAAA or a control intervention were examined. Regardless of victimization history, participants benefited from EAAA to some degree (28%–85% relative risk reduction). Prior victimization was not a significant moderator of the variables that mediate EAAA’s effectiveness, suggesting EAAA functions similarly for women regardless of victimization history. Finally, women who were raped post-intervention blamed themselves significantly less after taking EAAA than women in the control group. This effect was found both for rape survivors and women with no history of victimization but not for attempted rape survivors. These results contribute to the #MeToo movement(s) by showing the power of feminist resistance education as well as areas where program adaptation or boosters are needed.

The #MeToo movement has brought to the fore the ongoing problem of sexual assault, especially in the context of relationships with acquaintances and those in positions of power (Jaffe, Citation2018). Empowering women to resist sexual violence has been a priority for feminist activists and advocates in North America for decades (e.g., Bateman, Citation1978; McCaughey, Citation1997; Cermele, Citation2010). Strategies have included feminist organizing and creation of new entities and approaches for activism (e.g., Reclaim the Night marches), legal reform (e.g., changes to rape/sexual assault laws), art (e.g., Born in Flames by Lizzie Borden), prevention (e.g., Women Against Rape), individual self-defense (e.g., Wen-Do Women’s Self Defence in Canada; Women’s Martial Arts Federation in U.S.), and support and advocacy (e.g., rape crisis centers, feminist therapy). Unfortunately, despite this work and as the #MeToo movement makes clear, the rates of sexual violence have not decreased (Breiding et al., Citation2014; Koss et al., Citation1987; Smith et al., Citation2018). By conservative estimates, one in five women will experience a rape in her lifetime, with most occurring by age 25 (Breiding et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2018). Survivors have made their voices heard through #MeToo and amplified the importance of resistance education.

The Enhanced Assess, Acknowledge, Act (EAAA) sexual assault resistance program

The EAAA program (also known as Flip the Script with EAAATM) is rooted in feminist social psychological theory and evidence (e.g., Nurius and Norris (Citation1996) cognitive ecological model; Rozee and Koss (Citation2001) AAA conceptualization; Bart and O’Brien (Citation1985) and Ullman’s (Citation1997) studies on what works in resistance) demonstrating the emotional and knowledge barriers women face when confronted by sexually coercive male acquaintances. EAAA provides knowledge and skills to assist women to overcome these barriers. It is also grounded in grassroots feminist theory and knowledge (e.g., from activists, advocates, and practitioners in rape crisis and feminist self-defense) and stresses that no matter what women do or do not do, perpetrators are always and entirely responsible for the sexual violence they commit. Further, EAAA explicitly assures women that survival is successful resistance.

Within a positive sexuality frame, the goals of EAAA are: (a) to increase women’s detection of risk cues in acquaintance social contexts (e.g., isolation, alcohol) and men’s behavior (e.g., persistence, sexual entitlement) early in the interaction; (b) to increase women’s trust in their own perceptions and judgment and decrease emotional or cognitive obstacles to risk detection or resistance in acquaintance situations; and (c) to increase women’s confidence and ability to select from and use a wide range of strategies (e.g., leaving when possible, forceful verbal and physical self-defense) that predict the best outcomes (i.e., interruption of rape attempts; reduced severity of sexual assault; Tark & Kleck, Citation2014; Ullman, Citation1997). EAAA is not prescriptive and makes clear that women themselves are always the best judge of what they should or could do in any situation.

In this context, “resistance” refers to holding attitudes or taking actions that renounce society’s tendency to blame women for sexual violence, support rape culture, and undermine women’s sexual autonomy. It encompasses defensive strategies women use to defend their boundaries (including their sexual boundaries) and their bodies. For survivors, resistance extends to the rejection of sexual assault perpetrators’ and society’s descriptions of them and what happened when they were assaulted. EAAA, specifically, and resistance education more generally can thus be conceptualized as a strategy that is complementary with other feminist approaches working toward social and sexual justice, recovery, and healing (Radtke et al., Citation2020).

EAAA is designed for women aged 17–24, in the early years of university, who are at elevated risk of sexual assault (e.g., Cranney, Citation2015). The program’s audience is self-identified women students of all sexual identities (including asexual and trans women), abilities, and racial, ethnic, and class backgrounds, including international students. The program is gendered, focusing on male perpetrators, who represent the vast majority of perpetrators against women of all sexual identities (e.g., Coulter et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2018).

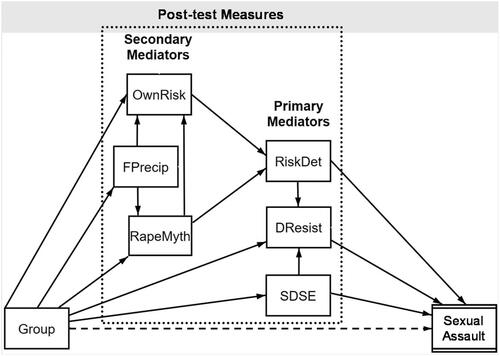

When evaluated in a large multi-site randomized controlled trial (RCT: see trial protocol here for full details; Senn et al., Citation2013), EAAA was effective in reducing the sexual assaults young women experienced for at least two years following participation (Senn et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). It also (a) increased women’s perceptions that they were personally at risk of acquaintance sexual assault; (b) reduced general rape myth acceptance; (c) decreased belief in woman-blaming explanations for rape; (d) improved detection of risk (in a hypothetical situation of acquaintance sexual coercion); (e) increased women’s knowledge of and willingness to use direct, forceful verbal and physical strategies in that situation; and (f) increased women’s confidence that they could defend themselves if necessary (Senn et al., Citation2017). These six domains are important elements of the theoretical model underpinning the program (i.e., cognitive ecological model, Nurius & Norris, Citation1996; AAA conceptualization, Rozee & Koss, Citation2001). EAAA’s impact on these measures fully account for (i.e., mediate) its effects on sexual assault (Senn et al., Citation2021). See for a graphic of this mediation model. Three mediators are primary because their effect on sexual assault is direct. Three are secondary because their effect on sexual assault is indirect, operating through improvement of risk detection.

Figure 1. Chained multiple mediation model explaining program reductions in sexual assault. Note. Primary mediators are variables that explain a portion of the EAAA program’s (Group) effect on sexual assault victimization and have a direct link to the outcome (Sexual Assault). Secondary mediators are variables that do not have a direct link to the outcome themselves but rather influence a primary mediator. See Senn et al. (Citation2021) for more detail. Dashed line indicates that the relationship between Group and Sexual Assault is fully mediated by the model. OwnRisk: perceived risk of acquaintance rape; FPrecip: belief in female precipitation of rape; RapeMyth: rape myth acceptance; RiskDet: risk detection; DResist: direct resistance; SDSE: self-defense self-efficacy.

Our Current Focus on Survivors

Any sexual violence prevention programming for women must recognize that survivors will be present. Given that survivors are at increased risk for subsequent abuse (Classen et al., Citation2005), sexual violence prevention programming should have benefits that extend to them, including a reduced risk for subsequent sexual assault. EAAA was designed with a trauma-informed educational approach to ensure its relevance and appropriateness for survivors (DePrince & Gagnon, Citation2018). Unlike other resistance or risk reduction programs that have failed to demonstrate reductions in sexual assault for rape survivors (Gidycz et al., Citation2006; Hanson & Gidycz, Citation1993), EAAA was effective in decreasing the incidence of sexual assault across 12 months for women with and without a rape history. However, this does not necessarily mean that the program was effective for both groups for the same reasons.

The best understandings of why revictimization occurs are consistent with the cognitive ecological model that is the theoretical foundation of EAAA (Nurius & Norris, Citation1996) and the research base supporting the program’s content (Rozee & Koss, Citation2001). Research suggests that survivors have even higher thresholds for acknowledging risk (Yeater et al., Citation2010), face even more cognitive and emotional obstacles to resistance (Norris et al., Citation1996), and/or show an increased likelihood of disabled resistanceFootnote1 (i.e., a greater likelihood of passive or other ineffective strategies and immobility) than other women (e.g., Norris et al., Citation1996; Anderson et al., Citation2018). Thus far, we have not analyzed how victimization status influenced the program’s effects on other outcomes, specifically those factors (i.e., mediators) that are responsible for reductions in sexual assault. This was our first goal for the current analysis.

Our second goal was to analyze whether the benefits of EAAA were similar for women who reported an attempted, but not completed, rape prior to enrolling. Although there is broad recognition of the continuum of sexual violence (e.g., Gidycz, Citation2011; Humphrey & White, Citation2000), most studies of prevention and revictimization focus on rape experiences or collapse across all forms of sexual victimization rather than distinguishing between attempted and completed rape (e.g., Resick, Citation1993; Ullman & Najdowski, Citation2011). Although methodologically defensible, researchers using these practices typically have assumed that their conclusions are generalizable only to rape, or to any sexual victimization, or to attempted and completed rape together, without any formal evaluation of these assumptions (for an exception see Fisher et al., Citation2007). Specificity is important to understand where aspects of the experience or the aftermath are likely different.

Compared to rape survivors, survivors of attempted rape have better outcomes (Perilloux et al., Citation2012; Zayed, Citation2008), are less susceptible to suicidal ideation (Segal, Citation2009), and experience less ongoing trauma (Testa et al., Citation2004). Therefore, we classified women according to their history of completed or attempted rape, the two forms of sexual victimization associated with the most negative outcomes (e.g., Fisher et al., Citation2003; Perilloux et al., Citation2012). For some of the outcomes (mediators) that explain EAAA’s effectiveness, we hypothesized that simply being sexually assaulted, regardless of whether penetration was attempted or completed, would affect women in similar ways. One example of an expected similarity is related to the optimism bias, the belief that although others similar to us are at risk of a negative event, we ourselves are not (e.g., Conversano et al., Citation2010). Judgements of other women’s risk of becoming a victim of acquaintance rape are relatively accurate, whereas perceptions of personal risk are not. It is the latter half of the bias that impairs risk perception in situations where sexual assault risk is elevated (e.g., Messman-Moore & Brown, Citation2006; Senn et al., Citation2021). One would expect women who have experienced either attempted or completed rape to be less likely to underestimate their risk of sexual assault than women who have not had these experiences.

For other mediators, the type of assault could be more relevant. Self-defense self-efficacy, the confidence that one could defend herself if required, is one such example. A few studies suggest that learning physical self-defense may be of specific benefit to rape survivors’ self-efficacy (e.g., Pinciotti & Orcutt, Citation2018). Nevertheless, if two women both struggled with their attackers, but only one situation ended in rape, this reality may interact with the training provided and self-efficacy may differ. Such differences could have implications for how the content in a resistance program is received by women with varying sexual assault histories.

Our third, and final, goal was to assess self-blame for women who experienced rape following their participation in EAAA compared to women in the control group. Our definition of resistance includes fighting back against harmful cultural messages about woman-blaming, including blaming of oneself. Some feminist scholars and activists have expressed concerns that prevention programming for women in general, and resistance education or self-defense training in particular, is potentially victim-blaming and could lead to increased self-blame if women were to experience rape following such programs (e.g., Basile, Citation2015; Valenti, Citation2015). There are strong feminist arguments against these conjectures (e.g., Hollander, Citation2016; Radtke et al., Citation2020), and as the #MeToo movement makes clear, women continue to experience sexual violence and have the right to any knowledge that could improve their lives. However, the research evidence on the impact on blame is lacking.

EAAA was designed to actively and consistently counter woman-blaming because higher levels of self-blame have been linked to poorer outcomes directly or indirectly (Frazier, Citation2003; Ullman et al., Citation2007), and self-blame has been implicated in increasing revictimization in some (Miller et al., Citation2007) but not all prospective studies on revictimization (Ullman & Najdowski, Citation2011). We have previously demonstrated that participation in EAAA substantially reduced woman-blaming rape myth beliefs (Senn et al., Citation2017), and in the current analysis, we assessed self-blame for those women who experienced rapeFootnote2 after they had taken the program.

Hypotheses

Preliminary Analysis: Situating the Sample

Based on past research, one would expect some differences prior to program intervention on demographic or background variables or on perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs between women who have and have not experienced an attempted or a completed rape. Although these comparisons are not the focus of our study, they are presented to allow readers to situate this sample within the current research literature.

EAAA Program Effects by Prior Sexual Victimization

Past research (Brecklin & Ullman, Citation2004; Norris et al., Citation1996; Nurius et al., Citation2000) suggested that there would be group differences on the baseline measures of some mediators (e.g., perceived risk, self-defense self-efficacy) that could affect our analyses. We hypothesized that EAAA would have beneficial effects on all mediators of the program’s effectiveness beyond these differences. We hypothesized that EAAA would be as effective in reducing sexual assaults for women who had experienced an attempted rape as for women who had experienced a completed rape prior to entering the study. Additionally, we hypothesized that EAAA would reduce self-blame attributions for women who experienced rape after taking the program, whether or not the post-program victimization was a first rape or revictimization.

Method

Participants

Eight hundred and ninety-three first-year women students were recruited on three university campuses. The demographics for the full sample have been reported elsewhere (Senn et al., Citation2015). Of those, 851 women provided responses on mediators measured at both baseline and post-test and are the focus of this paper. There was no characteristic difference between the 42 women who were excluded and the 851 who were retained. Similar to the full sample, the mean age of these women was 18 years, three-quarters were White, and most were heterosexual (92%). In terms of sexual history, the majority were sexually active, with approximately half involved in romantic or sexual relationships at the start of the study.

Intervention

EAAA

The EAAA program curriculum has four 3-hr units briefly described here. Unit 1: Assess helps women identify situations and behaviors that signal higher risk for sexual violence. Unit 2: Acknowledge offers opportunities to identify and overcome emotional barriers, to acknowledge the threat from men they know, to strengthen trust in themselves and their judgment, and to provide practice in identifying and resisting verbal coercion. Unit 3: Act provides empowerment verbal and physical self-defense training (based on Wen-Do Women’s Self Defence wendo.ca) focused on effective strategies for resisting common acquaintance tactics. Unit 4: Relationships & Sexuality offers high quality sexual information and a context for exploring and talking about their own sexual desires and relationship values (based on the Our Whole Lives sexuality education curriculum; Goldfarb & Casparian, Citation2000; Kimball & Frediani, Citation2000). Messages running through multiple units are that: women’s sexual rights and boundaries matter, responsibility for sexual assault always rests with the perpetrator and not the victim/survivor, no one other than the woman herself can judge what she could or should do in any situation, and survival is also successful resistance. For more detail on the program content, see Senn et al., Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2017; Radtke et al., Citation2020; http://SARECentre.org.

This small group (≤20 participants) intervention was led by pairs of highly trained, peer (<30 yrs) women facilitators. Women attended an average of 3.62 (SD = 0.82) of four sessions with most (91%) attending three or four sessions. Curriculum fidelity was high (average 94%) as measured by assessment of randomly selected audio recordings (Senn et al., Citation2015).

Control

To match the standard of care common to all university campuses at the time, brochures on sexual assault were available for participants to take and read, with a knowledgeable person present to answer any questions that arose about sexual assault or available resources. Brochures chosen were specific to the campuses but had common elements including general sexual assault information, date rape drug facts, legal and medical information, and local resources.

Procedure

Key elements of the procedure and measures are provided here. The full trial protocol has been published elsewhere (Senn et al., Citation2013), as have the CONSORT flowchart and 1- and 2-year primary and secondary outcomes for the full sample (Senn et al., Citation2015, Citation2017).

Participants were recruited through psychology department participant pools, posters, classroom recruiting, tabling, and email. Interested students were screened by a research assistant, told the purpose of the study, the longitudinal survey process and timing, and randomization procedure. Participants then chose the timing of the baseline and experimental intervention sessions that matched their schedule. Participants attended the baseline session in person, completed computerized surveys, and were randomly assigned to either EAAA or control. Randomization was disclosed upon arrival to the first or, for controls, only intervention session. Participants assigned to the EAAA program attended the remainder of the sessions on the same weekend or the same weekday evening for the next three weeks. They then attended an in-person post-test survey session within one week of their final session or, for control participants, matched to their experimental group’s final session. Six-, 12-, 18- and 24- (for cohort recruited in first year) month follow-up surveys were completed online.

Measures

Previous completed rape or attempted rape

The Sexual Experiences Survey–Short Form Victimization (SES-SFV; Koss et al., Citation2007), often considered the gold standard for measuring sexual assault, was used with one modification to focus the questions on male perpetration given the gender-specific focus of the program content. Seven items, each with a stem that described a sexually coercive or assaultive act or attempted act (e.g., “A man put his penis into my vagina, or [someone] inserted fingers or objects without my consent by”), are followed by five descriptions of perpetrator tactics or strategies (e.g., “Using force, for example holding me down with their body weight, pinning my arms, or having a weapon”). The tactics ranged from verbal pressure to alcohol incapacitation to physical force. Participants identified how frequently they had experienced each stem and tactic since the age of 14, since the baseline (one-week post-test), and since the last survey for 6- to 24-month follow-ups. Participants who reported an attempted or completed rape were prompted to use a pop-up calendar to pick when the incident happened to allow for time-to-event analysis.

Participants’ responses were scored at the highest level of sexual victimization experienced using Koss et al. (Citation2007) standard coding: (0) no victimization, (1) unwanted sexual contact, (2) attempted sexual coercion, (3) sexual coercion (oral, vaginal, or anal penetration accomplished by penis, fingers, or objects with verbal tactics only), (4) attempted rape, and (5) completed rape (oral, vaginal, or anal penetration accomplished by alcohol or drug incapacitation, threats of force or force). Experiences of attempted or completed rape at baseline (since the age of 14) and in the post-test to 12-month follow-up period were the focus of the current analyses.

Primary mediatorsFootnote3

Full descriptions and reliabilities of the measures are published elsewhere (Senn et al., Citation2017, Citation2021). The primary mediators included: (a) Situational Risk Detection, based on an evolving coercive dating scenario where participants indicate at each stage how likely the situation is to end in positive and negative outcomes (higher scores indicate more risk detected; Testa et al., Citation2006); (b) Direct Resistance, a subscale measuring willingness to use effective (forceful) self-defense strategies in the same coercive situation (higher scores indicate more endorsement of effective resistance strategies; Testa et al. (Citation2006) built on items from Norris et al. (Citation1999) and Davis et al. (Citation2004)), and (c) Self-defense Self-efficacy, assessing participants’ confidence in their ability to deal with various coercive situations (higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy; adaptation of Marx et al.’s, Citation2001, adaptation of Ozer & Bandura, Citation1990, scale).

Secondary mediators3

The secondary mediators included: (a) participants’ perceptions of their own (general) risk of acquaintance sexual assault (single item “What are your chances of being raped by someone you know?” adapted from Gray et al., Citation1990), (b) acceptance of rape myths, measured by the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale–Short Form (IRMA-SF) (Payne et al., Citation1999), and (c) beliefs that women are responsible for rape, assessed using the Female Precipitation subscale of the Perceived Causes of Rape Scale (lower scores indicates lower woman-blame; Cowan & Campbell, Citation1995).

Post-intervention rape attributions: Self-blame

Rape attribution scale

Frazier’s (Citation2003) Rape Attribution Scale (RAS) was given only to participants who experienced a completed rape in any follow-up period. They reported “How often they thought they were assaulted because …” for 10 items on a 5-point scale from (1) never to (5) very often. The 5-item Behavioral Self-blame scale is the focus here. Higher scores represent greater belief that their own behavior was to blame for what happened. The subscale had good criterion validity in the original sample. Internal consistency was high in the original and current study (Cronbach’s αs = 0.87 and 0.89, respectively). Participants were not given the RAS if they indicated that they did not consider what happened to be an assault of any kind.

Results

Previous rape or attempted rape victimization

At baseline, 23% of participants had experienced completed rape, 27% attempted rape, 22% coercion, 31% attempted coercion, and 50% had experienced non-consensual sexual contact. Twelve percent were survivors of attempted but not completed rape. Tests of group differences showed that survivors of both previous rape and attempted rape were more likely to have experienced non-consensual sexual contact and attempted and completed coercion at baseline than women with no previous rape history (ps < 0.001; see ).

Table 1. Baseline comparisons among groups (N = 851).

Differences in baseline characteristics were compared among the three groups (Previous Completed Rape, Previous Attempted Rape Only, No Previous Any Rape) using one-way analyses of variance for continuous variables and contingency table Chi-Square tests for categorical variables. Survivors of completed and attempted rape were similar to those who had not experienced either form of sexual violence on most demographic and background variables, but there were some differences based on sexual activity, relationship status, experience with self-defense courses, and ethnicity (See ). Survivors of attempted and completed rape had higher baseline perceptions of their personal risk of sexual assault than other women (i.e., lower optimism bias). Women who had been raped had lower baseline self-defense self-efficacy than either women who had experienced an attempted rape or those without such experiences.

EAAA program effects on mediator outcomes by prior sexual victimization

Linear mixed models were used to analyze the post-test scores on outcomes (mediators) by including a random intercept to account for the correlation among observations within sessions (i.e., within-session clustering), a fixed effect for assigned intervention (EAAA vs. control), a fixed effect for group (Previous Completed Rape vs. Previous Attempted Rape Only vs. No Previous Any Rape), the cross-product between assigned intervention and group, and the corresponding baseline score. Results are reported as adjusted means and adjusted between-intervention mean differences with corresponding p values. Cohen’s d is also reported to quantify the intervention effect sizes as small, d = 0.2, medium, d = 0.5, or large, d = 0.8 (Cohen, Citation1988). Finally, moderation p values were calculated to assess whether any observed differential intervention effect among the three groups was statistically significant. Self-blame scores were analyzed using linear mixed models in a similar manner.

See for details. Prior victimization was not a significant moderator of EAAA’s medium to large effects on any of the secondary mediators (i.e., perceived risk of acquaintance rape, rape myth acceptance, or belief in female precipitation) nor the primary mediators (i.e., risk assessment, self-defense self-efficacy, and direct resistance).

Table 2. Comparisons of secondary (Indirect) and primary (Direct) mediator scores by intervention and rape history.

EAAA program effects on sexual assault outcomes by prior victimization

Incidences of completed and attempted rape over the one-year period of follow-up were estimated from Kaplan–Meier failure analyses and compared between interventions using Greenwood’s variance formula. Corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the absolute risk reductions are reported. Relative risk reductions are also reported to quantify intervention effect sizes due to EAAA. Variances were inflated to account for within-session clustering. Although p values have been reported to complement the analyses, as the size of each subgroup and risk of victimization varied by type of previous victimization, our interpretation of the results is appropriately focused on effect sizes and relative risk reductions rather than on the significance of p values (Cutter, Citation2020).

See for details. The results from the present study show that participants, whether or not they had experienced previous victimization, benefited from EAAA (28%–85% relative (rel.) risk reduction). For women with no prior history of rape or attempted rape, the incidence of completed rape was reduced from 4.6% control group) to 0.7% (EAAA group; 85% rel. risk reduction) and attempted rapes from 3.5% to 1.4% (60% rel. risk reduction). This is a 70% combined relative risk reduction. For survivors of attempted rape, the relative risk reductions from EAAA were 46% for completed rape (13.1%–7.1%) and 82% for attempted rape (25.8%–4.7%). This is a 63% combined relative risk reduction. For rape survivors, EAAA reduced the one-year risk of rape from 22.7% to 16.4% (28% rel. risk reduction) and attempted rape from 15.5% to 9.8% (37% rel. risk reduction); a 30% relative risk reduction when combined.

Table 3. One-year Kaplan–Meier sexual assault risks.

Self-blame

Of the 851 women, 61 experienced completed rape within one-year post-intervention, 45 of these perceived their experience as an assaultFootnote4 and completed the RAS. As can be seen in , survivors of completed or attempted rape at baseline had significantly higher mean self-blame scores for the subsequent rape than women with no such history. Overall, women who took EAAA blamed themselves significantly less for a subsequent rape (M = 14.2, SE = 1.6) than women in the control group (M = 18.9, SE = 0.9; p = 0.01). Surprisingly, however, EAAA reduced self-blame in women who had previously experienced completed rape and those who had not experienced either attempted or completed rape but not for women who had previously experienced an attempted rape. See for more detail.

Table 4. Between-intervention comparisons of rape attribution self-blame subscale scores by experience of previous completed rape among participants who experienced a completed rape after enrollment in the study (n = 45).

Discussion

This article fills a number of gaps in the literature related to individual differences in intervention effects and the impact of sexual assault resistance education on survivors. It also provides one of the first assessments of the impact of a resistance program on the risk of revictimization for both attempted and completed rape survivors. Our conclusions are based on a large (N = 851) and diverse sample (25% of students were women of color) of young women attending universities in large and smaller cities. Our data are experimental and prospective, so we can make causal (RCT with random assignment) and temporal (longitudinal design) conclusions about program effects.

Situating the current sample

As reported previously for the full RCT sample (Senn et al., Citation2015), and in line with other research (e.g., Krebs et al., Citation2009), a sizeable proportion of the women entering the study had experienced some form of sexual victimization since the age 14. When these experiences were scored at the highest level of sexual violence experienced, almost one in four participants had experienced completed rape and an additional one in eight had experienced attempted rape. As previous research has shown (e.g., Krebs et al., Citation2009), many of the women who had experienced a rape attempt (completed or not) had also experienced sexual coercion, attempted sexual coercion, and non-consensual sexual contact at a higher rate than women who had not experienced a previous rape attempt. Given the structure of the SES-SFV, these experiences could have occurred on the same or different occasions.

While not a focus of our analyses, the baseline data reported here also support prior research showing limited but important differences between women who have and have not experienced rape and extends these to women who have experienced attempted, but not completed, rape. Like rape survivors, attempted rape survivors were more likely to be sexually active and involved in romantic or sexual relationships than women who had never experienced a rape attempt. This extends the findings of higher levels of sexual and relationship activity reported by rape survivors (e.g., Campbell et al., Citation2004) to women who experienced rape attempts.

Survivors of sexual violence are overrepresented in self-defense courses (see Brecklin & Ullman, Citation2004 for a review) compared to women with no history of sexual victimization, although studies vary in whether they find associations between learning self-defense and child and adult sexual violence, rape in adulthood, adult sexual victimization, or in one study, attempted rape specifically (Brecklin, Citation2004). Our baseline data replicate Brecklin’s (Citation2004) finding that women who had experienced attempted but not completed rape were more likely to have self-defense training. Unfortunately, we cannot determine the timing to determine whether for this group of women self-defense was sought out after an attempted rape, was taken previously and contributed to that rape not being completed, or some combination (Brecklin, Citation2004; Brecklin & Ullman, Citation2005). Prospective research is needed to confirm the temporal relationship. However, we know from the current analysis that there are substantial benefits for women who take a resistance program, which includes empowerment self-defense, after an attempted rape.

Prior research suggests that sexual victimization is not experienced at the same rates by all groups of women students (Coulter et al., Citation2017). In our sample, Asian women had significantly lower rates of both attempted and completed rape from the age of 14 than either Black or White women students. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual women had similar rates of sexual assault to heterosexually identified women. As ours was not a random sample, we cannot reliably establish rates of victimization in sub-populations. However, Asian women’s lower rates are consistent with the limited number of studies in which sexual victimization risk has been examined for this subgroup of students (Archambeau et al., Citation2010; Coulter et al., Citation2017). By contrast, the rates of sexual violence reported by our participants appears to be inconsistent with the higher rates of sexual assault usually reported by bisexual women students (e.g., Coulter et al., Citation2017). Due to small cell sizes, we had to collapse lesbian/gay and bisexual women into a single group for the comparison which may have obscured differences. Alternatively, it may be that risk increases after the first year of university for bisexual women.

Does being a survivor of attempted or completed rape moderate EAAA’s effects?

For outcomes which are mediators of sexual assault effects

The design of the program tested here was formulated on Rozee and Koss (Citation2001) Assess, Acknowledge, Act (AAA) conceptualization which was grounded in Nurius and Norris (Citation1996) cognitive ecological model of the barriers to risk detection and resistance women experience when confronted by sexual coercion or assault from a man they know. We have demonstrated elsewhere that the components of this theoretical model work together to explain EAAA’s reduction on sexual assault; accounting for 95% of the variance in completed rape outcomes and 76% of the variance in attempted rape outcomes (Senn et al., Citation2021). The three components that work as primary (direct) mediators were situational risk detection, use of direct resistance (e.g., direct, forceful verbal and/or physical response and leaving) in hypothetical situations, and self-defense self-efficacy. The three secondary mediators, which have indirect effects on sexual assault–perception of personal risk, rape myth beliefs, and the specific belief in female provocation of rape–contributed to women’s ability to detect risk in situations. Research has linked prior victimization to higher thresholds for risk detection (e.g., Yeater et al., Citation2010) and/or reduced ability to resist or respond assertively to sexual threats (e.g., Livingston et al., Citation2007; Yeater et al., Citation2011). Consequently, we assessed whether women’s rape history moderated their ability to use the content and skills development from EAAA to counteract harmful attitudes (i.e., rape-supportive, woman-blaming ones), build their confidence that they could defend themselves, and enhance their existing risk detection and resistance skills for effective self-protection. Victimization history did not moderate any of EAAA’s six positive outcomes (mediators) related to attitudes and beliefs or knowledge and skills.

EAAA’s positive effects on the primary and secondary mediators were present and consistent for all groups–survivors of completed rape and attempted rape and women with no history of rape attempts. This was true despite group baseline differences on perceived acquaintance risk (survivors had higher scores than women who had never experienced a rape attempt) and self-defense self-efficacy (rape survivors had lower starting levels). Two of the tests of moderation (for self-defense self-efficacy and risk assessment) approached significance (i.e., p < 0.10), and in those cases, the effect sizes were larger for survivors (for women who had experienced rape or attempted rape in the former case and for women who had experienced attempted rape for the latter). Thus, the resistance program had robust effects for both groups of women survivors and women who had not experienced a prior rape attempt.

For sexual assault outcomes

Our previously published planned subgroup analysis of EAAA’s efficacy showed that it substantially reduced the risk of completed and attempted rape both for survivors of rape and women who had never experienced rape (i.e., there was no significant moderation; Senn et al., Citation2015). We undertook a more nuanced exploratory analysis here to examine whether the program’s effects on attempted and completed rape varied depending on whether women had experienced completed rape or attempted rape or no experience of rape.

Given past literature on revictimization (e.g., Messman-Moore & Brown, Citation2006), we expected and found higher rates of attempted and completed rape for rape survivors during follow-up (four and five times higher than for women without previous victimization). Women who had experienced attempted rape were at seven times the risk for future attempted rape and nearly triple the risk of completed rape than women who had never experienced a rape attempt. The pattern of outcomes demonstrated that although EAAA is effective in reducing sexual violence for all groups of women (28–85% relative reductions), there were expected and unexpected differences in the size of those risk reductions. EAAA reduced the relative risk most dramatically (>80%) for completed rape among women without prior rape victimization of any kind and attempted rape among women who had experienced prior attempted but not completed rape. It also led to a higher absolute reduction in completed and attempted rapes for survivors than for women with no prior rape experience.

How does participation in EAAA impact self-blame for new sexual assaults?

Women who had survived either an attempted or a completed rape before they entered the study reported significantly higher self-blame in relation to a subsequent rape experience than women who had not. This supports and extends previously published findings that prior rape victimization predicts more negative outcomes (here self-blame) if victimization occurs again (e.g., Casey & Nurius, Citation2005) to attempted rape survivors.

Nevertheless, and importantly, EAAA participation significantly reduced self-blame both for rape survivors and for women who had not previously experienced a rape attempt of any kind. This is crucial because self-blame has been linked to poorer health outcomes for rape survivors (Frazier, Citation2003). Frazier et al. (Citation2005) demonstrated that higher behavioral self-blame is related to social withdrawal and that social withdrawal is related to higher distress. As such, countering this type of self-blame is another form of resistance against a rape culture (Radtke et al., Citation2020) and is a critically important benefit of EAAA. Women who had not experienced rape or attempted rape in adolescence benefited the most from EAAA. They rarely or never had self-blaming thoughts after experiencing rape compared to similar women in the control group who at least sometimes blamed themselves. This suggests that getting resistance education to young women before their first sexual assault would magnify its benefits. We have developed an adaptation for younger girls (14–17 years) and are currently evaluating it in a randomized controlled trial.

According to Ullman and Najdowski (Citation2011), the social withdrawal associated with behavioral self-blame reduces social support, which limits future opportunities for positive interactions. Their prospective study demonstrated that positive social reactions to disclosures from people in women’s lives did not lead to lower behavioral self-blame and suggested that it is not easy to produce a positive impact on self-blame. In contrast, EAAA appears to create a social environment in which women become better at challenging these beliefs for other women (i.e., reductions in rape myth beliefs and woman-blaming) and themselves. The program was designed to interrupt self-blame in both its content (e.g., clear statements that while there are things women can do to undermine perpetrators’ advantages in situations, there is no risk without the presence of a person willing to engage in sexual violence) and its process (e.g., careful training of facilitators to challenge woman-blaming while keeping women engaged during the program), so it is likely that attention to these details have driven these findings.

It is less clear why EAAA does not similarly reduce self-blame for women who had experienced a prior attempted rape. There is limited evidence to draw on for explanations because most previous studies on self-blame have focused on completed rape. Perhaps, survivors who avoided rape previously had strongly held beliefs about their own abilities to resist on that occasion and this coincided with lower behavioral self-blame for that event. A subsequent rape may undermine this view of themselves in some way. The higher baseline self-defense self-efficacy for women in this group supports the first part of this hypothesis. Ullman and Najdowski (Citation2011), in a slightly different context suggest, “[b]ehavioral self-blame may be reinforced in such victims who feel they should be able to change their behavior to avoid future assaults but are unsuccessful in doing so [on this occasion]” (p. 1952, with addition). Given the benefits of EAAA on program mediators (including rape myth acceptance, woman-blaming, and self-defense self-efficacy) and sexual assault outcomes for women who have experienced attempted rape in the past, the current inability of EAAA to reduce self-blame for women who had experienced an attempted rape requires further attention. Qualitative research may be needed to explore this phenomenon further. It is important to emphasize, however, that self-blame did not increase for any group of women.

Study strengths and limitations

The design of the RCT and our large and diverse sample provide a strong foundation from which to explore the impact of resistance education on survivors. Unfortunately, our sample was not sufficiently large to allow for an intersectional analysis of variations in effects for survivors of varied ethnicities or sexual identities.

Our analysis was also limited by the self-blame attribution scale’s (reasonable) requirement that redirects participants away from scale completion if they do not label their experience based on SES behavioral questions (i.e., fitting the definition of rape or attempted rape) as an assault (purposefully not using the language of rape or attempted rape). This is necessary because each item is framed with the assault label. As is common (e.g., Littleton et al., Citation2017), 26% of women did not label their experience in this way. In future studies, it would be useful to measure self-blame attributions for all women whose SES reports meet sexual violence criteria no matter their acknowledgement status. This is particularly important since acknowledgement and revictimization appear to be linked (Littleton et al., Citation2017).

Our quantitative study was not well positioned to explore the reasons behind some of the variations in effects for survivors of attempted versus completed rape. A mixed method study specifically designed to explore these variations is needed to replicate and test our (and other) hypotheses regarding these findings. Further, a qualitative investigation of the experience of resistance education for survivors of varied types of sexual violence would be important for generating new hypotheses and possibilities for enhancement of programs.

Conclusions

Scholarly reviews of self-defense, resistance, and risk reduction programs for women have called for more focus on how prevention works and needs to be amended to work best for survivors (e.g., Gidycz & Dardis, Citation2014). Some programs do not acknowledge that survivors are in the room (see examples of survivors’ experiences in Worthen & Wallace, Citation2021). This is a serious oversight given the high rates of victimization and revictimization reported in research and through the #MeToo movement. The latter has given new voice to survivor's experiences. These must not be overlooked in program design and evaluation. Our analysis shows the many benefits of sexual assault resistance education for women with varying victimization histories including possible unique benefits on sexual assault outcomes for survivors of attempted rape.

Still, there is room to enhance the EAAA program’s effects on sexual assault outcomes for survivors of completed rape and on self-blame for survivors of attempted rape. Survivors of completed rape and, to a lesser extent, survivors of attempted rape experience a wide range of negative outcomes, including symptoms (e.g., PTSD) and coping strategies (e.g., alcohol use) that can impair their capacity or willingness to use verbal and physical resistance (e.g.,Yeater et al., Citation2011). Survivors may benefit even more from resistance education when it is paired, or aligned, with therapy or other supports. The EAAA program’s impact on attempted rape is likely due to the empirically based content and activities that support women trusting their own instincts, responding to suspected danger cues early, and getting out of situations (when possible) before coercion progresses. The largest benefits for all groups of women, including attempted and completed rape survivors, were found here. For reducing completed rape, the empowerment self defense likely becomes more important. Past research has shown the benefits of self-defense for survivors (e.g., Brecklin & Ullman, Citation2004); rape survivors benefit here, but may require more than two hours of skills building to fully counteract the bodily impact of their previous assaults (e.g., Weitlauf et al., Citation2007). More research is needed to identify what enhancements or additional elements are needed for extension or booster sessions to strengthen effects and support survivors’ internal resources.

Our research provides an important challenge to the societal context in which media coverage for both completed and attempted rapes renders women’s resistance invisible (Hollander & Rodgers, Citation2014). When studies do not examine intervention effects or revictimization for women who have experienced attempted rape, important phenomena may be masked. Attempted rapes are often viewed as nonevents, narrow or lucky escapes, rather than as important experiences that have decided impact on the targeted person and constitute part of the problem of rape culture (Cermele, Citation2010). Our study’s nuanced findings of both similarities and differences related to sexual assault risks and program impacts for attempted rape survivors compared to rape survivors contributes to better understanding of the sexual violence continuum.

In the recent #MeToo context in which the media has tended to spotlight women’s individual and group resistance against powerful men, it can be easy to forget that most women who experience sexual violence are confronted by men who perpetrate under the cover of friendship or love and social relationships where gender is the primary power imbalance and where coercive tactics are often gradual, masked by heterosexual norms, and occur in private when there is no supportive community present. The #MeToo cultural moment, though important, still requires resources for women to heal from sexual violence and to build their capacity for possible future interactions with sexually coercive men without fear or restrictions. EAAA was developed to assist women in altering the obstacles they face in detecting risk and taking action to resist men they know (and like or love) in social situations that are supposed to be safe and fun (Nurius & Norris, Citation1996). Sexual assault resistance education like EAAA, framed in a positive sexuality context, is an important tool for empowering women to center their own desires, retain and develop relationships where their desires are respected, and develop a variety of verbal and physical resistance strategies and the willingness to use them when necessary to defend their rights. This is all resistance!

Despite its strengths, EAAA is only one part of the solution for sexual violence prevention. Importantly, even when it “fails,” women benefit from taking it by understanding EAAA's message that perpetrators are entirely responsible for their behavior and reducing the harmful self-blame which can impede healing and recovery. In this way and many others, EAAA contributes to both women’s resistance and recovery and the challenge to rape culture.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The language and idea of disabled resistance was first put forward by feminist legal scholar Catharine A. MacKinnon (Citation1982).

2 The Rape Attribution Survey is designed for completed rape survivors only.

3 Primary mediators have a direct effect on sexual assault outcomes. Secondary mediators influence sexual assault through their effect on a primary mediator.

4 The questions presume this and so are inappropriate as written for women who actively reject the label of assault.

References

- Anderson, R., Cahill, S., & Delahanty, D. L. (2018). Differences in the type and sequence order of self-defense behaviors during a high-risk victimization scenario: Impact of prior sexual victimization. Psychology of Violence, 8(3), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000169

- Archambeau, O. G., Frueh, B. C., Deliramich, A. N., Elhai, J. D., Grubaugh, A. L., Herman, S., & Kim, B. S. (2010). Interpersonal violence and mental health outcomes among Asian American and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander college students. Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 2(4), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021262

- Bart, P. B., & O’Brien, P. H. (1985). Stopping rape: Successful survival strategies. Teachers College Press.

- Basile, K. C. (2015). A comprehensive approach to sexual violence prevention. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(24), 2350–2352. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1503952

- Bateman, P. (Ed.). (1978). Fear into Anger: A manual of self-defense for women. Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall.

- Brecklin, L. R. (2004). Self-defense/Assertiveness training, women's victimization history, and psychological characteristics. Violence against Women, 10(5), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801204264296

- Brecklin, L. R., & Ullman, S. E. (2004). Correlates of postassault self-sefense/sssertiveness training participation for sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00131.x

- Brecklin, L. R., & Ullman, S. E. (2005). Self-defense or assertiveness training and women's responses to sexual attacks. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(6), 738–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504272894

- Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Merrick, M. T. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization — National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6308a1.htm

- Campbell, R., Sefl, T., & Ahrens, C. E. (2004). The impact of rape on women's sexual health risk behaviors. Health Psychology: official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 23(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.67

- Casey, E. A., & Nurius, P. S. (2005). Trauma exposure and sexual revictimization risk: Comparisons across single, multiple incident, and multiple perpetrator victimizations. Violence against Women, 11(4), 505–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801204274339

- Cermele, J. (2010). Telling our stories: The importance of women's narratives of resistance. Violence against Women, 16(10), 1162–1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210382873

- Classen, C. C., Palesh, O. G., & Aggarwal, R. (2005). Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 6(2), 103–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005275087

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Conversano, C., Rotondo, A., Lensi, E., Della Vista, O., Arpone, F., & Reda, M. A. (2010). Optimism and its impact on mental and physical well-being. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health: CP & EMH, 6, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901006010025

- Coulter, R. W., Mair, C., Miller, E., Blosnich, J. R., Matthews, D. D., & McCauley, H. L. (2017). Prevalence of past-year sexual assault victimization among undergraduate students: Exploring differences by and intersections of gender identity, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 18(6), 726–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0762-8

- Cowan, G., & Campbell, R. R. (1995). Rape causal attitudes among adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 32(2), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499509551784

- Cranney, S. (2015). The relationship between sexual victimization and year in school in U.S. Colleges: Investigating the parameters of the "Red Zone". Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(17), 3133–3145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514554425

- Cutter, G. (2020). Effect size or statistical significance, where to put your money. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 38, 101490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2019.101490

- Davis, K. C., George, W. H., & Norris, J. (2004). Women's responses to unwanted sexual advances: The role of alcohol and inhibition conflict. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(4), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00150.x

- DePrince, A. P., & Gagnon, K. L. (2018). Understanding the consequences of sexual assault: What does it mean for prevention to be trauma informed? In L. M. Orchowski & C. A. Gidycz (Eds.), Sexual assault risk reduction and resistance: Theory, research, and practice. (pp. 15–36). Academic Press.

- Fisher, B. S., Daigle, L. E., Cullen, F. T., & Santana, S. A. (2007). Assessing the efficacy of the Protective action-completion nexus for sexual victimizations. Violence Vict, 22(1), 18–42. https://doi.org/10.1891/vv-v22i1a002

- Fisher, B. S., Daigle, L. E., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2003). Acknowledging sexual victimization as rape: Results from a national-level study. Justice Quarterly, 20(3), 535–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820300095611

- Frazier, P. A. (2003). Perceived control and distress following sexual assault: A longitudinal test of a new model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1257–1269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1257

- Frazier, P. A., Mortensen, H., & Steward, J. (2005). Coping strategies as mediators of the relations among perceived control and distress in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.267

- Gidycz, C. A. (2011). Sexual revictimization revisited: A commentary. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(2), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311404111

- Gidycz, C. A., & Dardis, C. M. (2014). Feminist self-defense and resistance training for college students: A critical review and recommendations for the future. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 15(4), 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014521026

- Gidycz, C. A., Rich, C. L., Orchowski, L., King, C., & Miller, A. K. (2006). The evaluation of a sexual assault self-defense and risk-reduction program for college women: A prospective study. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00280.x

- Goldfarb, E. S., & Casparian, E. M. (2000). Our Whole Lives: Sexuality education for grades 10-12. Unitarian Universalist Association.

- Gray, M. D., Lesser, D., Quinn, E., & Brounds, C. (1990). The effectiveness of personalizing acquaintance rape prevention: Programs on perception of vulnerability and on reducing risk-taking behavior. Journal of College Student Development, 31, 217–220.

- Hanson, K. A., & Gidycz, C. A. (1993). Evaluation of a sexual assault prevention program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 1046–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.61.6.1046

- Hollander, J. A. (2016). The importance of self-defense training for sexual violence prevention. Feminism & Psychology, 26(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353516637393

- Hollander, J. A., & Rodgers, K. (2014). Constructing victims: The erasure of women's resistance to sexual assault. Sociological Forum, 29(2), 342–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12087

- Humphrey, J. A., & White, J. W. (2000). Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 27(6), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00168-3

- Jaffe, S. (2018). The collective power of #MeToo. Dissent, 65(2), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/dss.2018.0031

- Kimball, R. S., & Frediani, J. (2000). Our Whole Lives: Sexuality education for adults. Unitarian Universalist Association.

- Koss, M. P., Abbey, A., Campbell, R., Cook, S., Norris, J., Testa, M., Ullman, S. E., West, C., & White, J. (2007). Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 270–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x

- Koss, M. P., Gidycz, C. A., & Wisniewski, N. (1987). The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.162

- Krebs, C. P., Lindquist, C. H., Warner, T. D., Fisher, B. S., & Martin, S. L. (2009). College women's experiences with physically forced, alcohol- or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health, 57(6), 639–649. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649

- Littleton, H., Grills, A., Layh, M., & Rudolph, K. (2017). Unacknowledged rape and re-victimization risk: Examination of potential mediators. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(4), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684317720187

- Livingston, J., Testa, M., & VanZile-Tamsen, C. (2007). The reciprocal relationship between sexual victimization and sexual assertiveness. Violence against Women, 13(3), 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801206297339

- MacKinnon, C. A. (1982). Feminism, Marxism, method, and the state: An agenda for theory. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 7(3), 515–544. https://doi.org/10.1086/493898

- Marx, B. P., Calhoun, K. S., Wilson, A. E., & Meyerson, L. A. (2001). Sexual revictimization prevention: An outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.25 https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.69.1.25

- McCaughey, M. (1997). Real knockouts the physical feminism of women's self-defense. New York University.

- Messman-Moore, T. L., & Brown, A. L. (2006). Risk perception, rape and sexual revictimization: A prospective study of college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00279.x

- Miller, A. K., Markman, K. D., & Handley, I. M. (2007). Self-blame among sexual assault victims prospectively predicts revictimization: A perceived sociolegal context model of risk. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701331585

- Norris, J., Nurius, P. S., & Dimeff, L. A. (1996). Through her eyes: Factors affecting women's perception of and resistance to acquaintance sexual aggression threat. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00668.x

- Norris, J., Nurius, P. S., & Graham, T. L. (1999). When a date changes from fun to dangerous: Factors affecting women's ability to distinguish. Violence against Women, 5(3), 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778019922181202

- Nurius, P. S., & Norris, J. (1996). A cognitive ecological model of women's response to male sexual coercion in dating. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 8(1–2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v08n01_09

- Nurius, P. S., Norris, J., Young, D., Graham, T. L., & Gaylord, J. (2000). Interpreting and defensively responding to threat: Examining appraisals and coping with acquaintance sexual aggression. Violence and Victims, 15(2), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.15.2.187

- Ozer, E. M., & Bandura, A. (1990). Mechanisms governing improvement effects: A self-efficacy analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(3), 472–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.3.472

- Payne, D. L., Lonsway, K. A., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1999). Rape myth acceptance: Exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(1), 27–68. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238

- Perilloux, C., Duntley, J. D., & Buss, D. M. (2012). The costs of rape. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(5), 1099–1106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9863-9

- Pinciotti, C. M., & Orcutt, H. K. (2018). Rape aggression defense: Unique self-efficacy benefits for survivors of sexual trauma. Violence against Women, 24(5), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780127708885 https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801217708885

- Radtke, H. L., Barata, P. C., Senn, C. Y., Thurston, W. E., Hobden, K. L., Newby-Clark, I., & Eliasziw, M. (2020). Countering rape culture with resistance education. In D. Crocker, J. Minaker, & A. Nelund (Eds.), Violence Interrupted: Confronting Sexual Violence on University Campuses (pp. 349–370). McGill-Queen’s University.

- Resick, P. A. (1993). The psychological impact of rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8(2), 223–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626093008002005

- Rozee, P. D., & Koss, M. P. (2001). Rape: A century of resistance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(4), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00030

- Segal, D. L. (2009). Self-reported history of sexual coercion and rape negatively impacts resilience to suicide among women students. Death Studies, 33(9), 848–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180903142720

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Barata, P. C., Thurston, W. E., Newby-Clark, I. R., Radtke, H. L., & Hobden, K. L, SARE study team (2013). Sexual assault resistance education for university women: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (SARE trial). BMC Women's Health, 13(25), 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-13-25

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Barata, P. C., Thurston, W. E., Newby-Clark, I. R., Radtke, H. L., & Hobden, K. L. (2015). Efficacy of a sexual assault resistance program for university women. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(24), 2326–2335. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1411131

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Hobden, K. L., Barata, P., Radtke, H. L., Thurston, W. E., & Newby-Clark, I. (2021). Exploring the mechanisms underlying the efficacy of a sexual assault resistance education program for women through a chained multiple mediation analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 45(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684320962561

- Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Hobden, K. L., Newby-Clark, I. R., Barata, P. C., Radtke, H. L., & Thurston, W. (2017). Secondary and 2-year outcomes of a sexual assault resistance program for university women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684317690119

- Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M-J., & Chen, J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief–Updated Release. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- Tark, J., & Kleck, G. (2014). Resisting rape: the effects of victim self-protection on rape completion and injury. Violence against Women, 20(3), 270–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214526050

- Testa, M., Vanzile-Tamsen, C., & Livingston, J. A. (2004). The role of victim and perpetrator intoxication on sexual assault outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(3), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2004.65.320

- Testa, M., Vanzile-Tamsen, C., Livingston, J. A., & Buddie, A. M. (2006). The role of women's alcohol consumption in managing sexual intimacy and sexual safety motives. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(5), 665–674. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2006.67.665

- Ullman, S. E. (1997). Review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24(2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854897024002003

- Ullman, S. E., & Najdowski, C. J. (2011). Prospective changes in attributions of self-blame and social reactions to women's disclosures of adult sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(10), 1929–1934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510372940

- Ullman, S. E., Townsend, S. M., Filipas, H. H., & Starzynski, L. L. (2007). Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self-blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00328.x

- Valenti, J. (2015, June 12). We need to stop rapists, not change who gets raped. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/12/stop-rapists-not-change-who-gets-raped

- Weitlauf, J. C., Ruzek, J. I., Westrup, D. A., Lee, T., & Keller, J. (2007). Empirically assessing participant perceptions of the research experience in a randomized clinical trial: The women's self-defense project as a case example. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: JERHRE, 2(2), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2007.2.2.11

- Worthen, M. G., & Wallace, S. A. (2021). "Why should i, the one who was raped, be forced to take training in what sexual assault is?" Sexual assault survivors' and those who know survivors' responses to a campus sexual assault education program?”. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(5–6), NP2640–NP2674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518768571

- Yeater, E. A., McFall, R. M., & Viken, R. J. (2011). The relationship between women's response effectiveness and a history of sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(3), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510363425

- Yeater, E. A., Treat, T. A., Viken, R. J., & McFall, R. M. (2010). Cognitive processes underlying women's risk judgments: Associations with sexual victimization history and rape myth acceptance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019297

- Zayed, M. H. (2008). Effects of adult sexual assault types and tactics on cognitive appraisals and mental health symptoms (Publication Number Order No. 333506) [Doctoral Dissertation, Northern Illinois University]. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.