Abstract

Aims

1) Explore occupational challenges of individuals participating in pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), and 2) examine impacts of occupational therapy, embedded within PR, on performance of, satisfaction with, dyspnea in and experience of challenging occupations.

Methods

A mixed methods cohort study recruited adults from a 8-week community-based PR program which incorporated targeted occupational therapy. Participant perspectives of the occupational therapy were explored using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale.

Results

Seventeen participants with either Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Bronchiectasis, or Interstitial Lung Disease were recruited (age 71 ± 7(SD) identifying 269 problematic occupations. Nine participants completed the program obtaining clinically and statistically significant improvements in COPM performance, satisfaction scores and Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale, maintained at 12 wk, and validated through participants reporting they ‘now do things differently’.

Conclusion

People with chronic respiratory conditions are occupational beings. Occupational therapy embedded within PR can influence participants’ engagement in challenging occupations.

Introduction

Chronic respiratory conditions are chronic diseases that affect the airways, including the lungs and passages to the lungs, characterized by symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath (dyspnea), chest tightness and cough, estimated to impact 545 million people globally.Citation1 These symptoms, along with anxiety and fatigue, create barriers for this population to engage in everyday activities, referred to as ‘occupations’ within the occupational therapy profession.Citation2,Citation3 Self-reported challenging occupations specifically in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are extremely varied and have a weak association with clinical determinants such as the degree of airflow limitation, Medical Research Council dyspnea grade and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage.Citation4 Annegarn et alCitation4 highlighted the importance of assessing occupations experienced as challenging on an individual basis to inform person-centered interventions within comprehensive multidisciplinary programs. Findings from three recent scoping reviews indicate occupational therapists readily provide interventions to individuals with chronic respiratory conditions, particularly as part of multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) programs however, all have called for further details regarding the unique role of occupational therapy and evidence of its benefits and impact.Citation5–7

Moreover, the identification of individually challenging occupations through an occupation-focused assessment such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) allows for occupational therapy interventions, embedded within PR, to be goal directed and occupation-centered.Citation8 The aim of the interventions are to influence individuals’ occupational performance, satisfaction with performance and symptom-burden in the individually challenging occupations.Citation9 There is a need to explore the impact and outcomes of occupational therapy in PR and the aims of this preliminary study were to: (1) explore the types of occupational challenges in individuals with chronic respiratory conditions participating in PR, and (2) examine occupational performance, satisfaction with performance and dyspnea management in occupations experienced as challenging immediately post PR with occupational therapy, and at 6- and 12-week follow-up.

Study design and methods

A mixed methods cohort study with convergent design gathered data pre, post, 6 wk and 12 wk following participation in a combined PR and occupational therapy program. The study was approved by the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Services (HREC/2019/QGC/48573) and Griffith University (Ref. No. 2019/373) human research ethics committees. It was deemed unethical to include a comparison group as PR with occupational therapy was running as standard practice at the study site. As a result, a concurrent process evaluation was added to explore mechanisms of impact.

Setting and population

The study setting was a community-based center of a tertiary health service. The PR program is a comprehensive multidisciplinary education and exercise program for people with chronic respiratory conditions inclusive of thorough assessment followed by person tailored therapies designed to improve self-management of chronic respiratory conditions through improved physical and psychological condition of participants.Citation10 The exercise program consists of 2 × 90-min supervised exercise sessions over 8 wk combining resistance and aerobic exercises individually prescribed by a physiotherapist (in terms of intensity, duration, frequency, type and mode) and adjusted based on perceived exertion (aiming for moderate breathlessness). Education consisted of 6 × 2-hour group education sessions presented by multidisciplinary team members covering a holistic approach to self-management of chronic respiratory conditions. The occupational therapy components include a home visit, group energy management education and two occasions of occupation-based training.

The occupational therapy home visit was 1:1 with each participant for approximately 1 h in their primary place of residence and occurred prior to commencement of the exercise and education components of PR. Occupations identified as challenging during initial interviews were the focus of intervention firstly through didactic exploration whereby the therapist could gather information relevant to the context of each challenging occupation. Following this, the therapist would observe the participant engaging in a self-identified challenging occupation within the home environment to evaluate the quality of the individual’s occupational performance alongside underlying person, body functions, and environmental factors influencing performance. These occupations could have been self-care (e.g., donning/doffing shoes), productive (e.g., vacuuming floors), leisure (e.g., dancing in living room), or mobility (e.g., walking to a local bus stop). Tailored occupation-focused education incorporated ways to adapt occupational performance through application of energy conservation techniques, breathing retraining, adaptive equipment and/or environmental modifications. Following the participant would engage in an occupation-based intervention incorporating discussed strategies and modifications. Reinforcement of education occurred during the active component through verbal feedback provided by the therapist based on observations of the quality of occupational performance, biofeedback from recordings of heart rate and oxygen saturation from Masimo Rad-5® Pulse Oximetry monitoring, and participants subjective reflections on how they felt whilst performing a challenging occupation.

The occupational therapy group education component occurred in week two of PR and lasted approximately 1-h. Group size varied from 30 pre-COVID −19 including participants involved in PR and significant others, to 15 once local COVID-19 social distancing protocols were in place. The education session was occupation-focused designed to educate participants on the principles of energy management (i.e., reducing metabolic demands) and breathing retraining (i.e., enhancing ability to meet metabolic demands) that could be applied during occupational performance. A showcase of useful equipment, description of potential environmental modifications and demonstration of basic energy conservation and breathing techniques were provided. The group nature provided opportunities for participants to learn through shared experience. A written resource was provided to participants for further reading and reinforcement of education.

The two sessions of occupation-based training occurred 1:1 with the occupational therapist and participant within exercise sessions as a substitution for an upper limb exercise between weeks three and seven of PR. Each session lasted approximately 15-minutes and was completed in ‘domestic like’ environments within the community health centers (e.g., bathrooms, store cupboards). The purpose of the occupation-based training sessions was to provide participants an opportunity to experience the difference when implementing taught adaptive strategies during occupational performance. A protocol was followed whereby a participant engaged in a challenging occupation (e.g., mopping floors) for two minutes firstly without instruction using their ‘own technique’ and secondly using taught ‘energy management techniques’ tailored to each participant during the session based on therapist observations. Monitoring was completed throughout with recording of objective physiological responses to occupational performance of heart rate and oxygen saturation from Masimo Rad-5® Pulse Oximetry, subjective experiences of dyspnea using the Modified Borg Dyspnea scale and time to recover post performance (i.e., heart rate return to within 6 beats per minute and oxygen saturation within 2% of resting). These records were used in combination with discussions around the participant’s experience and perspectives of the session as feedback to reinforce adaptive techniques used. On conclusion of each session, the therapist discussed with participants how to use learnt strategies and techniques within their own home or community and encouraged the participant to practice at home.

Further details of the exercise and education components of PR at Gold Coast Health are provided in supplementary material.

To gain a wide representation of participant experiences and perspectives,Citation11 convenience sampling was used to recruit individuals referred to the combined PR and occupational therapy program over a six-month period. To be included in the study, participants needed to be adults (18+ yrs.) with a diagnosis of a chronic respiratory condition including COPD, Bronchiectasis or Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) who, had not completed PR previously and, had no formal diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation (using PS Power and Sample Size calculation program version 3.0) with data from a previous study using the COPM SD =1.3,Citation12 indicated a minimum sample size of six was required to meet the 2-point change required for a clinically important difference in the primary outcome measure,Citation8,Citation13 with a probability of 0.9 (Power) at a significance level of 0.05. Recruitment over a six-month period sought to obtain greater than the minimum required participants to gather a wider representation of participant experiences and perspectives for qualitative outcomes.

Study outcomes and procedure

The COPM was used with participants to identify challenging occupations and measure self-perceived performance of, and satisfaction with, these challenging occupations. Participants were prompted to consider challenging occupations as occupations that they would like to do, need to do, or are expected to do but found difficult to complete because of their respiratory condition.Citation8 Each occupation is rated for performance and satisfaction, ranging from 1 (not at all able/satisfied) to 10 (able to perform extremely well/extremely satisfied).Citation8 The COPM is designed to detect changes in occupational performance and satisfaction over time,Citation8 is reliable in individuals with chronic respiratory conditions,Citation14 and is responsive to PR.Citation15

The Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale measured participant’s perceptions of breathlessness when they last performed each of the identified challenging occupations on a 10-point scale from 0 (nothing at all) to 10 (maximal). The scale is commonly used in PR as a unidimensional psychophysical scale assessing dyspnea intensity in response to a specific stimulus (e.g., exercise or occupational performance).Citation16 Recall of dyspnea has been found to be accurate in male individuals with moderate to severe COPD,Citation17 and is likely to be more accurate when recalled in relation to a specific context (e.g., specific to engaging in a particular occupation).Citation18

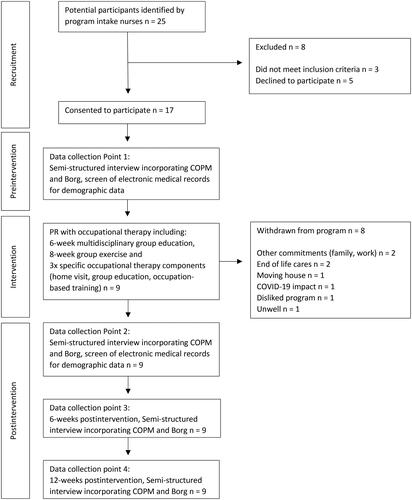

Study recruitment occurred over two 3-month periods (Jul-Sep 2019 and Apr-Jul 2021) with a pause in recruitment approved by human research ethics committee due to parental leave of the primary researcher. Those who met the inclusion criteria were identified by a nurse during an initial assessment and were referred to the primary researcher for study details and consent processes. Participant characteristics including demographic variables, disease variables and symptoms and impact variables routinely collected prior to PR were obtained from participants electronic medical records for the purpose of providing insights into the health profile of participants (). Semi-structured interviews with qualitative exploration were completed by the primary researcher on four occasions: pre and post intervention, 6- and 12 wk follow-up. All interviews included the COPM and Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale. The first interview also asked participants to prioritize up to five occupations they found challenging and wanted to address during the program. Exploratory and probing questions sought to explore the participant experiences of their challenging occupations. The remaining interviews, all post intervention, explored participant perspectives and experiences of the occupational therapy components of the PR program. illustrates the full study procedure.

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

COPM, Canadian Occupational performance Measure; Borg, the Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease; PR, Pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Table 1. Baseline participant characteristics.

Data analysis

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized descriptively. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v27 was used for Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test to explore change between pre and post intervention, followed by post intervention to 6- and 12-week follow-up. The level of significance was set at p ≤ .05. Challenging occupations from the COPM were classified as either self-care (including personal care and community management occupations), mobility (including functional mobility), productivity (including paid/unpaid work, household management, study occupations), or leisure (including quiet recreation, active recreation, and socialization).Citation8 Mobility-related challenges are typically classified under “self-care”Citation8 however, as per previous studies mobility related challenges are expected to be highly prevalent for people with chronic respiratory conditions and therefore were classified separately.Citation4,Citation19–21 Qualitative interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, then examined using thematic analysis with an inductive approach.Citation22 The primary researcher (AM) read and inductively coded interview transcripts using Dedoose application and then another researcher (RW) independently reviewed interview transcripts to confirm coding and concepts. Subsequent categorization into themes was discussed by all research team members.

Results

Participant demographics

Seventeen participants provided consent and completed baseline data collection including seven (41%) males, with a mean age of 70 (SD 7.37). The majority were diagnosed with COPD (76%), with mean forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) % predicted 57 (SD 23.18) (). Participants described broad impacts of living with chronic respiratory conditions (). This ranged from the physical experience and sensations whilst engaging in occupations, to how it affects them mentally and emotionally, and impacts their relationships and abilities to engage socially. Nine participants completed the combined program and postintervention data collection attending on average 10.44(2.79) exercise sessions. illustrates participant research flow with reasons for withdrawing.

Table 2. Initial interview themes related to participant perceptions of living with a chronic respiratory condition.

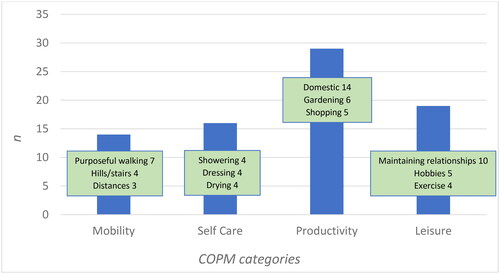

Challenging occupations

The 17 participants identified 269 challenging occupations, averaging 15 each, primarily related to productivity (45%) followed by leisure (21%), self-care (19%) and mobility (13%). illustrates the number of prioritized challenging occupations across the seventeen participants with frequently occurring occupations listed against each category. Participants expressed a range of reasons for experiencing challenges with occupational performance () including factors related to how they approached occupations (such as tendencies to rush or push through tasks), the physical demands of the occupation (such as requirements to bend), health related factors (such as the fluctuating nature of symptoms or symptom anticipation), or external factors related to the environments of the occupation (such as the impact of the weather or perceptions of people around them). Seventy-eight occupations were identified as ‘important’ and prioritized by participants to focus on improving during the program. Occupations were perceived as important for a variety of reasons () including: a wish to continue to look after themselves through maintaining their health, fitness, and physical appearance; looking after and upholding a high standard for the appearance of their property/homes; maintaining their independence particularly for self-care occupations; feeling that occupations just ‘have to be done’ as opposed to choosing to engage; remaining engaged with family and social connections and maintaining roles; and because they were enjoyable and brought a sense of satisfaction and/or fun.

Figure 2. Prioritized challenging occupations.

Number of prioritized challenging occupations in 17 participants assessed using the COPM (Canadian Occupational Performance Measure). Frequently described occupations are listed under each category.

Table 3. Initial interview themes related to participant perceptions of why occupations are important.

Change scores pre- and postintervention

Following intervention, clinically and statistically significant improvements were reported for performance of challenging occupations increasing by 2.87 (95% CI, 3.56 to 2.18; p <.001), satisfaction with performance which increased by 3.5 (95% CI, 4.35 to 2.65; p <.001), and Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale which decreased by 2.10 (95% CI, 1.28 to 2.90; p <.001). Participants reflected on their challenging occupations after the program and explained the various ways they now ‘do things differently’ when it comes to occupational performance (). Many reflected on what they had learnt through occupational therapy sessions describing how they now modify their approach to challenging occupations through implementing techniques such as pacing and coordinating their breathing or using recommended equipment. Participants expressed they improved not only in their ability to perform challenging occupations, but it seemed they were able to generalize more broadly what they had learnt, their perception of their breathing difficulties had improved and there was a sense of greater endurance when performing occupations. Participants also reported higher self-efficacy regarding their ability to manage and engage in challenging occupations now having a clear understanding of their limitations and increased confidence to engage in challenging occupations.

Table 4. Postintervention interview themes related to participants perspectives of their challenging occupations postintervention and their experiences of these.

Outcomes at 6- and 12 wk postintervention

Changes in participant performance scores were not clinically or statistically significant for challenging occupations 6- and 12 wk postintervention with scores decreasing by 0.32 (95% CI, 0.47 to 1.10; p =.832) and 0.5 (95% CI, 0.35 to 1.35; p =.274) respectively. Similarly, changes in participant satisfaction with performance of challenging occupations scores 6- and 12 wk postintervention were not clinically or statistically significant with scores decreasing by 0.08 (95% CI, 0.64 to 0.80; p =.665) and 0.4 (95% CI, 0.34 to 1.13; p =.294) respectively. Changes in participant Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale 6- and 12 wk postintervention were also not clinically or statistically significant with scores increasing by 0.20 (95% CI, 0.92 to 0.52; p =.219) and 0.17 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.28; p =.200) respectively.

Discussion

Occupational therapists have long contributed to multidisciplinary PR but there is a need to evidence the contribution and effectiveness of this involvement.Citation5–7 To contribute to this evidence base, the present preliminary work identified occupational challenges of individuals with chronic respiratory conditions participating in PR, as well as reported on the impact of PR in individually identified challenging occupations.

Recruited participants with mixed chronic respiratory diagnoses identified a wide range of challenging occupations, most commonly classified as productivity and leisure. Although occupational challenges of individuals with chronic respiratory conditions outside of COPD have never been explored, findings are consistent with studies identifying individuals with broad severity of COPD experience a variety of challenging occupations with a high proportion classified as productivity. Citation4,Citation19–21 Unlike these previous studies, occupations classified as ‘mobility’ did not feature as highly. Potentially the participant profile inclusive of individuals with ILD and bronchiectasis may account for this difference. Given PR is offered in clinical practice to individuals with a range a chronic respiratory diagnosis, future research is needed to understand the occupational challenges of individuals across the range of diagnoses that bring them to PR. The inclusion of interviews enhanced understanding of how mobility was positioned within people’s lives, leading to alternate classification as either leisure or productivity. For example, participant twelve identified walking with their daughter as a challenging occupation. This was categorized as leisure as the interview revealed the value and purpose for this occupation was social as a way of connecting and maintaining their relationship. By taking an occupational perspective it was possible to understand that mobility was a means to enable social connectedness rather than the prioritized outcome for the participant. This consideration of personal meaning aligns with current Australian healthcare systems focus on value-based health care where traditional clinical outcomes (e.g., breathlessness and exercise tolerance) should be considered alongside patient-reported outcomes measures (e.g., satisfaction with occupational performance and quality of life).Citation23 The understanding of the value of occupations for participants (e.g., internal personal motivations, social/connectedness, need and pure enjoyment) and their perspectives of why different occupations were challenging (e.g., the demands of the occupation itself and the context/environment in which the occupation is performed) reinforce the need for assessments that provide unique and personalized insights. This is essential to ensure that interventions, provided by occupational therapists and other PR members, are guided by person-centered approaches.Citation9

The difficulty in determining the specific impact of occupational therapy interventions when delivered as part of the PR program has been acknowledged.Citation24 Positive outcomes specifically from the addition of occupational therapy to PR have been summarized in three scoping reviews including improvement in quality of life and psychological impact, disease related outcomes such as prognosis, all-cause mortality, symptom management and pulmonary function, and occupation related outcomes such as occupational engagement, independence in basic activities of daily living and functional status.Citation5–7 Previously studies have use the COPM to evaluate occupational performance and satisfaction with performance after PR, Citation12,Citation15 however occupational therapy interventions were either not present,Citation15 or not a key component of the program only being offered as indicated.Citation12 To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the impact of PR with specific occupational therapy interventions on occupational performance, satisfaction with performance and experiences of dyspnea in individually identified challenging occupations. Our post-intervention improvements in all three outcomes exceeded and maintained the minimal clinically important difference up to 12 wk post intervention of two points for COPM performance and satisfaction scores,Citation8 and one unit change in the Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale.Citation25 Previously it has been suggested that goal-directed PR toward challenging occupations does not offer advantages over a generic exercise program.Citation15 A key difference in our study was that goal-directed interventions were delivered by occupational therapists using occupation-based and occupation focused interventions as opposed to physical exercises aimed to address identified problematic occupations. For example, participants who identified vacuuming as problematic within our study had opportunities to vacuum at home whilst receiving targeted educational strategies and techniques, as well as opportunities to practice and receive feedback whilst implementing techniques. Participants in Swell et alCitation15 who found vacuuming problematic were prescribed an exercise involving pulling up on a resistive elastic band, attached to wall bars, and provided verbal reminders that the exercise was designed to work toward their goal. Reports from participants in our study suggests the occupation-centered interventions were impactful. Further investigation is warranted through larger clinical trials to determine if goal-directed occupation-focused and occupation-based interventions alongside multidisciplinary PR has an influence on occupation-centered outcomes compared to traditional PR.

The intent of this small mixed-methods cohort study was to gather preliminary evidence that would support development of future larger multisite studies. A strength of this study lies in its mixed methodology which, by enabling participants to further explain quantitative findings, enhanced understanding of why occupations were challenging and important and provided further understanding of how the combined program was impacting participants post program. A limitation of the study was the use of recall for dyspnea during occupational performance for individuals with Bronchiectasis and ILD. Scope remains for future research validating recall of dyspnea during occupational performance using the Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale for these populations. Another limitation was the lower-than-expected sample size potentially due to the impact of COVID-19 on the number of potential participants with imposed social distancing regulations. Additionally, a high proportion of dropouts prior to completion of the program were noted however within drop-out ranges reported previously for PR.Citation26 Distinguishing the direct impact of occupational therapy when part of multidisciplinary PR is challenging with this study design. Future work includes a process evaluation to explore active components and causal mechanisms of the occupational therapy intervention. Further research, with a larger sample size and control group, would enable further examination of the impact of this intervention approach.

Conclusion

This preliminary mixed methods cohort study identified individuals with chronic respiratory conditions are occupational beings who experience a wide variety of occupational challenges. Using a person and occupation-centered approach to assessment provides insights into participants experience of occupations enabling interventions to be value-based and targeted toward individualized goals. Combining goal-directed occupational therapy interventions with PR was observed to influence participants performance of, satisfaction with, dyspnea in, and experience of these challenging occupations. Larger multisite studies with control arms are required to establish a causal relationship.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the work of Gold Coast Hospital and Health Services PR teams in delivering the combined PR and occupational therapy program. Clinicians Anne Sinclair and Penny Bishop contributed to the initial development of this body of work including protocol development, grant application and ethics application.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Soriano JB, Kendrick PJ, Paulson KR, et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):585–596. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3.

- Sewell L. Occupational therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation. In: Clini E, Holland EA, Pita F, Troosters T, eds. Textbook of Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017:159–169.

- World Federation of Occupational Therpists. About occupational therapy. https://wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy. Updated 2023. Accessed January 5, 2023

- Annegarn J, Meijer K, Passos VL, et al. Problematic activities of daily life are weakly associated with clinical characteristics in COPD. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):284–290. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.002.

- McCowan A, Gustafsson L, Bissett M, Sriram BK. Occupational therapy in adults with chronic respiratory conditions: a scoping review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2023;70(3):392–415. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12861.

- Finch L, Frankel D, Gallant B, et al. Occupational therapy in pulmonary rehabilitation programs: a scoping review. Respir Med. 2022;199:106881. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106881.

- Goubeau G, Mandigout S, Sombardier T, Borel B. Occupational therapy for improving occupational performance in COPD patients: a scoping review. Can J Occup Ther. 2022;90(4):353–362. doi:10.1177/00084174221148037.

- Law M. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). 5th ed. Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT); 2014.

- Fisher AG. Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: Same, same or different? Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21 Suppl 1(3):96–107. doi:10.3109/11038128.2012.754492.

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–64. doi:10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST.

- Holloway I, Galvin K, Holloway I. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare. 4th ed. Chinchester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

- Spruit MA, Augustin IML, Vanfleteren LE, et al. Differential response to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: multidimensional profiling. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(6):1625–1635. doi:10.1183/13993003.00350-2015.

- McColl MA, Paterson M, Davies D, Doubt L, Law M. Validity and community utility of the Canadian occupational performance measure. Can J Occup Ther. 2000;67(1):22–30. doi:10.1177/000841740006700105.

- Sewell L, Singh SJ. The Canadian occupational performance measure: is it a reliable measure in clients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Br J Occup Ther. 2001;64(6):305–310. doi:10.1177/030802260106400607.

- Sewell L, Singh SJ, Williams JEA, Collier R, Morgan MDL. Can individualized rehabilitation improve functional independence in elderly patients with COPD? Chest. 2005;128(3):1194–1200. doi:10.1378/chest.128.3.1194.

- Crisafulli E, Clini EM. Measures of dyspnea in pulmonary rehabilitation. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2010;5(3):202–210. doi:10.1186/2049-6958-5-3-202.

- Meek PM, Lareau SC, Anderson D. Memory for symptoms in COPD patients: how accurate are their reports? Eur Respir J. 2001;18(3):474–481. doi:10.1183/09031936.01.00083501.

- Williams M, Garrard A, Cafarella P, Petkov J, Frith P. Quality of recalled dyspnoea is different from exercise-induced dyspnoea: an experimental study. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55(3):177–183. doi:10.1016/s0004-9514(09)70078-9.

- Koolen EH, Spruit MA, de Man M, et al. Effectiveness of Home-based occupational therapy on COPM performance and satisfaction scores in patients with COPD. Can J Occup Ther. 2021;88(1):26–37. doi:10.1177/0008417420971124.

- Martinsen U, Bentzen H, Holter MK, et al. The effect of occupational therapy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24(2):89–97. doi:10.3109/11038128.2016.1158316.

- Nakken N, Janssen DJA, van den Bogaart EHA, et al. Patient versus proxy-reported problematic activities of daily life in patients with COPD. Respirology. 2017;22(2):307–314. doi:10.1111/resp.12915.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Lewis S. Value-based healthcare – meeting the evolving needs of our population. Aust Health Rev. 2019;43(5):485. doi:10.1071/AHv43n5_ED.

- Vaes AW, Delbressine JML, Mesquita R, et al. Impact of pulmonary rehabilitation on activities of daily living in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019;126(3):607–615. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00790.2018.

- Oliveira ALA, Andrade L, Marques A. Minimal clinically important difference and predictive validity of the mMRC and mBorg in acute exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2017;50(suppl 61):PA4705.

- Bjoernshave B, Korsgaard J, Nielsen CV. Does pulmonary rehabilitation work in clinical practice? A review on selection and dropout in randomized controlled trials on pulmonary rehabilitation. Clin Epidemiol. 2010;2:73–83. doi:10.2147/clep.s9483.