Abstract

Recent scholarship on the characteristics of Chinese urbanism engages with the practices and possible consequences of so-called enclave urbanism, said to generate cities as agglomerations of patchworked enclaves. Acknowledging that inequality becomes explicit in supposedly self-contained enclaves, in this paper, I seek to advance the initial debate by shifting the focus onto the spaces and processes in-between the enclaves. I draw on fieldwork in Shanghai to argue that perceptions of inequality, individual and group identities, everyday cultures and, ultimately, new ways of being in and making the city are shaped amidst the in-between spaces that essentiate emerging cities in China and elsewhere: urban borderlands. I outline a research agenda around the current and future urban condition and propose the exploration of borderland urbanism as a timely new direction in urban geography.

Introduction

Physical barriers have been constructed everywhere—around houses, apartment buildings, parks, squares, office complexes, and schools. Apartment buildings and houses which used to be connected to the street by gardens are now everywhere separated by high fences and walls, and guarded by electronic devices and armed security men. […] A new aesthetics of security shapes all types of constructions and imposes its new logic of surveillance and distances as a means for displaying status, and is changing the character of public life and public interactions (Caldeira, Citation1996, pp. 307–308).

Describing the “fortified enclaves” of Brazil’s Sao Paolo in the early 1990s, Caldeira (Citation1996) identifies their main characteristics as being physically isolated, turned inwards, socially homogenous and controlled with enforced rules of inclusion and exclusion. Sixteen years on, Wissink, van Kempen, Fang, and Li (Citation2012), among others, describe China’s growing and emerging cities as agglomerations of disconnected “patchworked, unifunctional, and monocultural enclaves”: commodity-housing compounds, work-unit compounds and traditional neighbourhoods from before 1949 when the communists took over. The editors of a recent special issue of this journal have diagnosed the ongoing practices as Enclave Urbanism, sparking a lively academic discourse around Chinese urban form (Breitung, Citation2012; Douglass, Wissink, & van Kempen, Citation2012; He, Citation2013; Hogan, Bunnell, Pow, Permanasari, & Morshidi, Citation2012; Jie Shen & Wu, Citation2012; Z. Li & Wu, Citation2013; Li, Zhu, & Li, Citation2012; Wang, Li, & Chai, Citation2012; Wissink et al., Citation2012; Wu, Zhang, & Webster, Citation2013a; Zhu, Breitung, & Li, Citation2012). But is this an accurate understanding of the emerging urban condition in China, or are alternative readings possible?

With this essay, I aim to expand the current debate around the fragmented city in bringing the attention to one particular phenomenon which is easily overlooked when examining cities and urbanisms from a remote bird’s-eye perspective; that is, outwardly disjointed urban enclaves are surrounded by borders and boundaries which not only divide, but also join them together. These borders and boundaries around and between them are not rigid lines or walls, but three-dimensional sociomaterial spaces which I call urban borderlands; they are the claimed, appropriated, inhabited, shared, continuously negotiated, maintained and often even nurtured spaces of co-presence and coexistence.

The article is based upon material gathered between 2006 and 2011 during extended periods of ethnographic work on one such urban borderland in Shanghai—the space in-between two sociospatially dissimilar but physically adjacent neighbourhoods (I purposefully avoid calling these entities “enclaves”): one traditional neighbourhood inhabited by low-income urban residents and rural-to-urban migrants, and one gated commodity-housing estate inhabited by better-off urban professionals. I draw on structured, open-ended and photo-elicitation interviews with selected participants. Building on an understanding of the larger-scale trajectories that led to the current condition of sociospatial differentiation, I use a transdisciplinary analytical framework to provide an agency-focused perspective on bordering practices and everyday life and on the sociopsychological identity processes involved in the negotiation of this urban borderland condition.

The paper is structured in seven sections. Following this introduction, I present an overview of the literature on urban enclaves and enclave urbanism in China and elsewhere, before presenting a conceptual framework around inequality, identity and place. Then, I provide a brief history of recent sociospatial transitions in Shanghai and introduce the case study area, turning to examine some of the most important sociopsychological identity processes under conditions of coexistence in distinct but adjacent urban neighbourhoods. I close with a detailed account of vibrant everyday life on the borderland. In closing, I argue that the emerging Chinese city is interesting not because of its supposedly segregated enclaves, but rather because of the wealth of activities, interactions and possibilities that mark the contact zones and spaces in-between urban borderlands.

Enclave urbanism

In an age of globalisation and mobility, people of different backgrounds and socioeconomic standing agglomerate in dense urban centres. Most human settlements have been made up of enclaves, initially simply serving the separation of functions (residences, commercial exchange, etc.); “with the emergence of private property”, however, “some enclaves were appropriated by powerful individuals […] and consciously separated from the commons” in order to allow them to “protect their power and control over resources and people” (Angotti, Citation2013, p. 114). Enclave urbanism in the twenty-first century is defined as

the pattern of metropolitan development produced by the globalized real estate and financial sectors, and codified in planning regulations, whereby metropolitan regions are becoming agglomerations of unequal urban districts, sharply divided by race, class and other social distinguishers, and often physically separated. Enclave urbanism is not random. It reflects the conscious adoption of policies that shape the physical and social life of the metropolis; it is not the absence of planning but the presence of a particular kind of planning. (Angotti, Citation2013, p. 113)

The West has reached a state where segregated areas are not usually visually apparent as “fortified enclaves”; rather, they “are presumed to be part of an open city where freedom, diversity and equality reign”; thus, the “contemporary enclave city is all the more difficult to challenge because of its semblance of openness” (Angotti, Citation2013, p. 115).

Angotti (Citation2013, p. 10) argues further that enclave urbanism has led to the branding and packaging of urban spaces as “separate commodities” that are defined, in essence, by their boundaries. Hence, it is startling that scholarship has not yet turned to examine these boundaries much more in detail. In my introduction to a recent special issue on urban borderlands, I explore the notions of border, boundary and borderland across disciplines in the natural and social sciences, noting that they have been notoriously neglected in the history of urban studies (Iossifova, Citation2013a). Only a small number of studies explicitly examine urban borderland conditions.

For instance, Boano and Martén (Citation2013) use Agamben’s spatial ontology to extract authority, production, exclusion, iconicity and identity as the five “tensions” which allow them to build an analytical framework for the study of borders in the case of Jerusalem and the West Bank. Karaman and Islam (Citation2012) examine how borders between ethnic communities in Istanbul are undone for the sake of redevelopment and suggest that planning practice should recognise “residents’ right to assimilation, but […] not impose it as an obligation”. Imai (Citation2013) examines urban borderlands from the intimate perspective of urban residents in Tokyo and argues that they can be defined as the “essential spaces of temporary and informal use” that are critical for the evolution of cities. In this sense, the borders and boundaries in-between enclaves are by no means rigid, nonnegotiable dividing lines.

Although typical for the Chinese city, our understanding of the meaning, function and state of urban borderlands in this context remains very limited. However, the emerging discourse around the characteristics of urban enclaves in China is timely and useful in illustrating how inequalities become explicit in social, economic and spatial differentiation. The following paragraphs provide a brief overview of the literature.

Urban enclaves in China

With a view on processes in “developing” countries, Roy (Citation2011a, p. 107) suggests that cities “have always been splintered and fractured spaces”, but that “the current geography of enclave urbanism is significant because it calls into question the anxieties that are often expressed about Third World megacities”: the reality of a state that “can declare an exception to the law”. The production of new urban enclaves in China is largely facilitated by the state in the context of state-sponsored gentrification through redevelopment of large patches of urban fabric and displacement of original residents (He, Citation2007). It follows a common pattern: first, a site is demarcated for redevelopment; resettlement conditions are negotiated with potentially existing residents and occupiers; occasionally, empty buildings are temporarily inhabited by rural-to-urban migrants and urban poor; once construction begins, armies of workers occupy the construction site; eventually, the new, often radically different, buildings become home to equally dissimilar groups of new residents (Iossifova, Citation2009a). Boundaries around new-built commodity compounds—and other types of enclaves—are therefore always human-made, socially constructed, “subsequent”; that is, they are “superimposed upon existing patterns of human settlements” (Newman & Paasi, Citation1998, p. 190).

Research on urban enclaves in China has been focused on studying and comparing them to each other as self-contained entities, for instance, brand new commodity-housing compounds, work-unit compounds and traditional neighbourhoods before 1949 (Wissink et al., Citation2012). Wu (Citation2005, p. 235) distinguishes between the gated community under socialism, where gates reinforce “political control and collective consumption organised by the state”, and the gated community of the post-reform era, where gates are erected to symbolise “emerging consumer clubs in response to the retreat of the State from the provision of public goods”. Jie Shen and Wu (Citation2012, p. 200) juxtapose the “standardized, monotonic landscape” of the Maoist period with new residential areas “designed to present a setting for symbolic consumption”. Like Yip (Citation2012), who interprets gated communities as resident retreats from state control, S.-m. Li et al. (Citation2012) speculate that the popularity of commodity compounds may be attributed to some liberation from state surveillance.

Unsurprisingly, Breitung (Citation2012, p. 291) finds that the walls and gates of commodity estates can be attributed to a market logic which “demands that territories are clearly defined and that access is filtered”. In a study of gated communities in Shanghai, however, Yip (Citation2012, p. 225) reveals that although the vast majority of neighbourhoods in the city are gated, many are effectively open in that they “do not necessarily impose strict access control”. He finds that gates and walls bring about “a higher sense of perceived security” and a stronger sense of community—much in contrast to findings on gated communities in the West (Yip, Citation2012, p. 232). Comparing the degree of community attachment among residents of new commodity-housing estates and conventional neighbourhoods, Li et al. (Citation2012) find greater community attachment among residents of the commodity-housing estates and argue that the higher quality of the living environment compensates for poorer neighbourly relations. Wang et al. (Citation2012) call for a comparative study of residents’ activity spaces in adjacent old and new forms of enclaves and for the consideration of rural-to-urban migrants in such studies. Finally, focusing on urban villages (rural villages enclosed by urban expansion) in three different cities, Li and Wu (Citation2013) study residential satisfaction and find that it may be linked with individual background (urban villagers, rural-to-urban migrants or relocated urban residents) as well as differing urban policy context.

In short, the emerging literature suggests that in order to assess the possible consequences of enclave urbanism, future research will need to take into account the important issues of historical genesis, place-related identity and community attachment. It is surprising, however, that the majority of studies concerned with urban enclaves in China seem to neglect not only that enclaves are part of larger, complex urban systems, but also that they are interlinked and interconnected through spatial, social, ecological and economic networks and relationships on various scales, and that therefore, their adjacency and co-presence in patchworked urban space must have important implications for perceptions of inequality among urban residents.

Inequality, identity and place

Enclave urbanism is the spatial manifestation of escalating inequality in China, which is of major concern to country’s leadership and the international community because of its potential to disrupt social cohesion and continued economic growth (Knight & Ding, Citation2012). It has now been acknowledged by the growing body of literature on subjective well-being in a variety of fields that interpersonal comparison by individuals with their reference persons determines how inequality is perceived (e.g. Boyce, Brown, & Moore, Citation2010; van Praag, Citation2011). Individuals identify how satisfied they are in various domains of life in relation to and in comparison with others—their reference groups, made up of “persons belonging to the same age bracket, education group, region, etc.” (van Praag, Citation2011, p. 117). Therefore, inequality matters at the local level (Knight, Citation2013).

In a sociological study of attitudes towards inequality, Whyte (Citation2010) found that despite being the poorest group, people in rural China were the least discontented about growing inequality. Rural-to-urban migrants “suffer both from their second-class status in the cities and from the widening of their reference groups to include the more affluent urban […] population” (Knight & Gunatilaka, Citation2011, p. 22). Urban households compare themselves with a wider range of households in the same city which influence their aspirations (Knight & Gunatilaka, Citation2011). Perceptions of inequality are therefore clearly related to processes of identity and identification.

Identity is often the product of ideology and is imposed upon individuals, groups and the places they inhabit. It emerges from the simultaneous processes of being identified and of identifying with—a province, a city, a class or a group, to name just a few (Graumann, Citation1983). Individual identity is not restricted to people’s “spiritual self” or “inner character”; it “includes all things and places a person considers his or her own” (Graumann, Citation1988, p. 61). Fried’s (Citation1963) notion of “sense of spatial identity” includes the social construction and mental appropriation of space. The sense of spatial identity

is fundamental to human functioning [in that it] represents a phenomenal or ideational integration of important experiences concerning environmental arrangements and contact in relation to the individual’s conception of his own body in space; [spatial identity] is based on spatial memories, spatial imagery, the spatial framework of current activity and the implicit spatial components of ideas and aspirations. (Fried, Citation1963, p. 156)

Living conditions and the built environment play a role in that place-related identity and attachment to place depend on the assessment of how well the current place satisfies a set of needs in comparison to available alternatives (Stokols & Shumaker, Citation1981).

Lalli (Citation1992) introduced a framework for the conceptualisation of urban-related identity and identification and an instrument to measure it. His “Urban Identity Scale” measures the human perception, cognitions and experience of the urban environment using five categories: external evaluation, general attachment, continuity with personal past, perception of familiarity and commitment. Several, if not all, of these categories are clearly related to referencing. The measure of external evaluation, for instance, builds on the evaluative comparison between one’s own living conditions and those of others; continuity with the personal past is related to the sense of temporal continuity which emerges from memories of interacting with others—strangers, family members, neighbours—in certain places; familiarity results from everyday encounter; and lastly, commitment develops from expectations and aspirations and the desire to maintain current living conditions. As part of the identity process, it is clearly related to the identification of reference groups: Who do we identify with? How do we aspire to live?

The “development of identity in general is the result of differentiation between self and others” (Lalli, Citation1992, p. 293). Concepts of identity and belonging and the complex sociospatial relations and relationships that they create or that create them are therefore linked with territorial borders and boundaries as signifiers of real or imagined difference (Iossifova, Citation2010, Citation2012a; Newman, Citation2003). In Deleuze’s understanding, territories “are more than just spaces: they have a stake, a claim. […] Territories are not fixed for all time, but are always being made and unmade, reterritorializing and deterritorializing” (Wise, Citation2005). Soft, semi-permeable borders are expressions of negotiated appropriation, of identities made and unmade, of emerging hybridity. In contrast, rigid physical borders can be read as expressions of territoriality, the demarcation and defence of space and its delimitation by boundaries.

Environmental elements (including objects and people) are “indicators of social position, ways of establishing group or social identity” within their respective culture; they result in expectations towards particular behaviour within environmental settings (Rapoport, Citation1982). Proshansky (Citation1978) speaks of the “strategic co-present social interactions”, the techniques that individuals adopt to cope with the presence of others. These interactions form part of the continuing process of appropriating and developing personal territory. Territoriality is a behaviour of exaggerated attachment to place, whereby place is not neutrally defined but rather fiercely defended in the face of menacing threats—including real or perceived discontinuities like the loss of social control or looming displacement (Sommer, Citation1969).

It becomes apparent that the mere co-presence of others in shared urban space will influence individual behaviour and habits, and that the many micro-strategies that individuals adopt in their day-to-day lives are of importance to the processes of shaping and maintaining culture and identity. In this way, micro-interactions (be they positive or negative) contribute to the emergence of new identities for individuals and groups that coexist in urban space. How do people negotiate their individual and group identities under the current conditions of coexistence in quickly transforming sociospatial environments in Shanghai? Before providing some initial answers to this question, I give a brief history of the most important place- and identity-related shifts that have occurred in Shanghai over the past decades.

Sociospatial transitions in Shanghai

Native place identity plays an important role in Chinese culture, in that people tend to identify with the place of origin of their ancestors rather than their own place of birth. This identification principle is of particular importance to the emergence of sociospatial differentiation in pre-communist Shanghai. People from the southern part of neighbouring Jiangsu Province (Jiangnan) had occupied well-paid jobs and the more expensive central parts of the city and were aspiring towards modern life styles and sophistication, particularly in the eyes of foreigners. As migrants kept arriving from Jiangbei, roughly the northern part of Jiangsu Province, the Jiangnan Shanghainese were eager to portray the living conditions and habits of newcomers as distinct from their own, inventing the category of Subei in the process. People from Subei were associated with poverty, strange customs, rural backwardness and downward mobility; consequently, they were confined to the lower ranks of social order, to lower paid jobs and to Subei settlements on the outskirts of Shanghai (Honig, Citation1989, Citation1990, Citation1992).

Albeit still important today, the traditionally predominant native place identity became secondary to socioeconomic class and political orientation as identity signifiers after Liberation in 1949 (Honig, Citation1992). The introduction of the household registration system (hukou) in 1951 added a whole new dimension to the structure of China’s society, dividing it, effectively, in two classes (Cheng & Selden, Citation1994): households were registered as rural (agricultural) or urban (nonagricultural). Those holding an urban hukou were entitled to a number of vital services in the city which were out of reach for the holders of a rural hukou.

Immigrants from Subei became urban hukou holders, true urban residents. They came to live and work in danweis—socialist work units of varying sizes, home to factories, homes, canteens, schools and sometimes even hospitals. The dingti (replacement/substitution) system contributed to the consolidation of urban working-class neighbourhoods over time, in that children largely inherited their parents’ jobs after their retirement (Ho & Ng, Citation2008; Wang, Citation2004). With time, street committees (jiedao) and neighbourhood committees (juweihui) were set up to facilitate the monitoring of residents and their political development.

When China entered the Opening Up and Reform era almost four decades ago, the danwei began to lose importance with the emergence of commodity housing and gated residential communities (Bray, Citation2005). State-owned enterprises began to close and many former employees became part of a new stratum: the urban poor. Simultaneously, migration restrictions were relaxed and “farmers”, initially welcomed as a cheap and exploitable labour force, began to move to the city to find work in factories and at construction sites (e.g., Goodkind & West, Citation2002; Li, Citation2004; Solinger, Citation1995, Citation1999). To date, municipal governments have failed to provide a satisfactory form of urban housing for the masses of rural-to-urban migrants (Mobrand, Citation2006; Jianfa Shen & Huang, Citation2003; Wu, Citation2002, Citation2006, Citation2008; Wu, Zhang, & Webster, Citation2013b; Zhang, Citation2001, Citation2002; Zhang, Zhao, & Tian, Citation2003; Zheng, Long, Fan, & Gu, Citation2009). Only a few accounts exist to document the lived experience of migrants in the city and the ways in which they succeed in finding informal solutions to their housing problem, for instance, in the basements or on the rooftops of formal housing blocks (Wu, Citation2007; Wu & Canham, Citation2008 provide insightful documentation on migrant living conditions in Beijing and Hong Kong).

Aiming to achieve “global-city” status, Shanghai—like many other Chinese cities—has undergone extensive urban renewal, “‘cleansing’ itself from the old and the poor through countless projects of gentrification” (Iossifova, Citation2009a, p. 66). The city’s sanitisation efforts included banning street vendors, hawkers and service providers from public space (see Dong & Zha, Citation2009; Yang, Citation2008) and hiding poor urban areas away from the eyes of the public. The struggle to attract international investment in projecting an image of impeccable law and order has led the municipality to adopt a number of aggressive practices which have been dubbed the “Shanghai model” for development, enthusiastically implemented elsewhere (Roy, Citation2011b).

The focus area

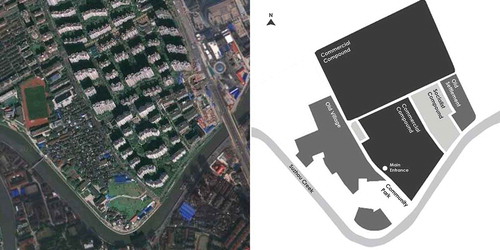

The case study area, located on the north banks of Suzhou Creek (see ), is part of an old shantytown which was known as a typical Subei neighbourhood and negatively associated with the characteristics of Subei culture. Upon demolition of large parts of the former Subei settlement and displacement of its residents elsewhere, away from the city, private developers erected the Commercial CompoundFootnote1 in the early 2000s, surrounding it with fences and securing its gates against unwanted intruders. Representing progress and development, the compound towers over the remainders of the past. It is home to affluent urban elites with incomes ten times the average in Shanghai—young, well-educated professionals, their parents and grandparents, and a few fortunate former shantytown dwellers were wealthy enough to buy into on-site resettlement flats. Notably, the compound offers refurbished studio flats in more or less legal “hotels” located around its edges, occasionally rented out to rural-to-urban migrant families and groups of friends.

Figure 1. Left: Aerial photograph of the case study area derived from Google Maps in April 2014. Photograph: © 2014 Google Imagery, © 2014 DigitalGlobe. Right: Schematic map of the case study area, encompassing the Old Village to the west and the Commercial Compound to the east. Drawing: Deljana Iossifova.

One side of the street dividing the Old Village and the Commercial Compound is lined by structures that had been added over the past years and are owned by the local government. The “garage-shop” (a space of about 10 square meters in size providing shelter with the roller shutter down, and a retail/small business space with the roller shutter up) represents the most frequently found type of space along the street. The other side is lined by a spacious sidewalk and a see-through fence, used by residents of the Village to span clotheslines and hang their laundry to dry; their furniture creates outdoor living rooms on the sidewalk.

“Enclaves” in context: co-presence and coexistence

The material presented in the following sections expands on work that has been previously published and discussed in detail elsewhere (Iossifova, Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2010, Citation2012a, Citation2012b). Between 2006 and 2011, I spent extensive periods in the case study area gathering data through participant observation, open-ended and photo-elicitation interviews with selected participants. I conducted a small-scale survey of rural-to-urban migrants, urban poor and middle-class residents in the area based on a questionnaire designed to assess the physical and social aspects of participants’ living conditions (past, present and future aspirations); to elicit perceptions of spatial boundaries to their neighbourhood in an application of “bound graphic investigation” (Weichhart, Citation1999); to examine how they perceive their own and adjacent neighbourhoods via 21 items on a five-point Likert scale; and to measure their place-related identification structured around Lalli’s (Citation1992) “Urban Identity Scale”. I draw on the analysis of in-depth interviews to substantiate findings. It should be noted that due to the very small size of the sample (50 participants), results can only be regarded as indicative.

Spatial imaginations and perceptions of the other

Around 5,000 people had their hukou registered in the Old Village, but according to the representatives of the local juweihui, in 2009, only 3,000 Shanghainese still lived there at the time of this research. Many original residents had left as soon as they were able to afford it, hoping for better living standards in new-built residential areas elsewhere. The remaining residents were mostly retired and laid-off workers who had become accustomed to performing everyday activities and chores together. Left-behind homes, meanwhile, had been rented out to new arrivals from the countryside, contributing to feelings of decreasing social control and territoriality among long-term residents of the neighbourhood. They perceived migrants as contributing to the deterioration of the built environment and as a challenge to governance (Interview with juweihui representatives, May 2009). Paralleling the Jiangnan-Subei-dichotomy in the creation of Subei identity in Shanghai before the Liberation, nowadays the label “migrant” serves to signify poverty, strange customs, rural backwardness, downward mobility and crime.

But the estimated 3,000 rural-to-urban migrants now, resident in Old Village were not the only ones experienced as encroaching upon accustomed routines; the residents of the adjacent Commercial Compound were often experienced as equally alien and described as distant and self-centred. In turn, despite initially exposing resentment and even disgust towards the Old Village, many residents of the Commercial Compound admitted to feelings of attachment, even nostalgia, which emerged from memories of their past in Shanghai or elsewhere. The following statement is representative of many: “I grew up in a traditional neighbourhood, very clean and neat. Much like the Village, but the streets were wider; wooden houses, two floors each. I miss this type of intimacy around here” (Interview with Ms Long, May 2009).

The small size of the sample does not allow drawing robust conclusions; however, it can be noted that different groups seem to perceive and evaluate inequality in the built environment in dissimilar terms. shows the results of an inquiry using a semantic differential instrument to examine perceptions of the own and adjacent neighbourhoods among the different groups in the case study area. Residents of the Commercial Compound perceived their own neighbourhood in exclusively positive terms, whilst they assigned negative attributes to the Old Village. Rural hukou residents of the Old Village shared the positive perception of the Commercial Compound and assigned negative attributes to the Old Village. Interestingly, urban hukou residents were reluctant to assign positive attributes to the Commercial Compound and remained mostly neutral in their evaluation.

Figure 2. Perceptions of the own versus perception of adjacent neighbourhoods among residents of the Commercial Compound (top); residents of Old Village holding and urban hukou (middle); and residents of Old Village holding a rural hukou (bottom). The study used a seven-point Likert scale (±3 = very; +/−2 = quite; +/−1 = rather; 0 = neither).

External evaluation of the built environment builds on the evaluative comparison between the own living conditions and those of others (the reference group). It plays an important role in processes of personal and group identity and is included among four other subdimensions (general attachment; continuity with personal past; perception of familiarity and commitment) in Lalli’s (Citation1992) Urban Identity Scale. To understand place-related identity under coexistence, residents in the case study area were asked to state their agreement or disagreement with 18 statements, scoring, respectively, on a scale from 1 (= disagree) to 3 (= agree). The average scores were calculated for each group (i.e., residents of the Old Village with rural or urban hukou and residents of the Gated Compound with urban hukou) for each of the subdimensions as well as the overall place-related identity (see ).

Figure 3. Scores on the Place-Related Identity Scale (PIS) and its subdimensions for residents of the Old Village holding a rural and urban hukou and residents of the Gated Compound.

Overall place-related identity scores did not differ much between urban hukou holders in the case study area, regardless of their place of residence in the Old Village or Commercial Compound; they were, however, lower for residents with rural hukou. This is not surprising as the relationship with the living environment is strengthened with increasing length of residence (Becker & Keim, Citation1975; Thum, Citation1981; Treinen, Citation1965). The sense of continuity with the personal past emerges from memories of interacting with others—strangers, family members, neighbours—in certain places. This is especially true for neighbourhoods such as Old Village, where urban hukou long-term residents scored highest on the subdimension “continuity”, followed by their counterparts in the Gated Compound and the most recent arrivals in the case study area, rural-to-urban migrants.

Likewise, “familiarity” builds up gradually over time and is linked with the experience of everyday encounter. It is therefore not surprising that the sense of familiarity was very similar among urban hukou holders in Old Village and the Commercial Compound and comparatively low among rural-to-urban migrants.

In stark contrast to the literature, which assumes that rural-to-urban migrants are reluctant to stay in the city (Fan, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Fan & Wang, Citation2008; Zheng et al., Citation2009), the majority (57%) of interviewed rural-to-urban migrants in the Old Village wanted to stay forever. This willingness is indicated in the subdimension “commitment” which reflects expectations and aspirations for the future and the desire to maintain living in the current environment. Although residents of the Commercial Compound scored highest, they were followed by rural-to-urban migrants in the Old Village who, on average, scored slightly higher than their urban hukou counterparts. In interviews, they often expressed feelings of attachment and the desire to stay. Rural-to-urban migrants also showed the lowest levels of “attachment”, in contrast to residents holding an urban hukou in the Old Village and Commercial Compound.

Figure 4. How residents of the case study area perceive the boundaries of their neighbourhood. (a): residents of the Commercial Compound; (b): urban hukou residents of Old Village; (c): rural hukou residents of the Old Village.

Unsurprisingly, reflecting the relatively high quality of their living environment, residents of the Commercial Compound scored highest on the subdimension “external evaluation”. Remarkably, however, rural hukou holders scored much higher than their urban hukou holding neighbours in the Old Village. This might be attributed to their relatively recent arrival in the city and their (still) high expectations and aspirations for the future. Conversely, the phenomenon could also be related to the actual spaces that participants refer to when they evaluate their neighbourhoods: asked to draw the spatial boundaries around their neighbourhood on a map, rural-to-urban migrants who lived in the Old Village often referred exclusively to the area containing the Commercial Compound (see for a comparison between the boundaries drawn by different groups on site). This might explain why they evaluate “their” neighbourhood higher than others in the Old Village. The phenomenon draws attention to the importance of spatial perceptions and how they contribute to the mental maps of residents and further, to their place-related identity and perceptions of inequality. Future research into perceptions of inequality in the built environment should therefore aim to include spatial aspects in data collection and analysis.

These findings begin to show the complex relationships of social and spatial factors that shape how and why people identify with their own—or adjacent—neighbourhoods under conditions of coexistence. Ultimately, it appears that despite claims to the contrary, dissimilar neighbourhoods (the so-called enclaves) are not at all self-sufficient; they are shaped by, and shape, their immediate environment and should be studied as entities embedded within their sociospatial context. Understanding exchange and interaction between urban enclaves is only possible by reading the materiality of and processes on the borders and boundaries between them. The following section first presents an instance of attempted physical division between neighbourhoods—imposed from above—before giving a brief overview of the everyday activities and interactions in the sociospatial in-between spaces that contribute to the undoing of formal divides and the emergence of urban borderlands in the case study area.

Undoing the formal divide

Borderland encounters are certainly not always free of conflict; they involve sharing space during physical activities or practices of personal hygiene; contesting alternative uses in and of limited space; negotiating relationships around micro-economic exchanges (client–customer relations); articulating one’s own and acknowledging the presence of the other in; and, often, they involve repeat and deliberate practices of conviviality as the foundation of long-term connections and even friendship.

Residents of the Commercial Compound had long complained about the traffic jams, pollution and noise resulting from the overspill of business and other activities onto the street dividing the Compound from the Old Village. In response, attempting to regulate the everyday life practices of poor residents where they inconvenienced the “civilised” ways of life of Commercial Compound residents, the jiedao erected a two-meter-high concrete fence in front of all shop and business spaces along the street in 2008 (see Iossifova, Citation2009b). The Chinese government had taken a nation-wide strategy of hiding away poor urban enclaves, instantiated in the experimental walling of migrant villages in Beijing (Gao, Citation2010).

Naturally, tenants in the case study area had trouble adapting to the challenge of catering to customers under conditions of blocked public access, lack of light and other inconveniences (see ). Mixing uncertainty with fear of persecution, shopkeepers and business owners behind the fence remained hesitant at first. Some had to close for good because of the difficult economic conditions, amplified by the onset of the global economic crisis which diminished their client base even further (e.g., Window of China, Citation2008). After approximately six months, however, the braver among shopkeepers began to experiment: some simply installed card boards behind the fence and occupied the space between their façade and the fence; others removed individual poles from the fence—keeping them stored nearby so as to be able to place them back immediately in the case of control; others again removed parts of the fence and replaced them with operable metal gates; some removed poles along the entire length of their shop’s façade, erasing the impact of the fence on their business altogether (see ). Within less than a year after the first appearance of the fence, most of those supposed to be contained behind it had perverted its purpose to serve their own.

Figure 5. The transformation of a restaurant and hair salon over time (from left to right, top to bottom): In early 2007; in 2008; in early 2009, after the fence, the restaurant had to remain closed due to lack of access; in late 2009, after the removal of individual poles; in early 2010; in the summer of 2011, after incorporating the space in-between the former facades and the fence as business spaces. (Photographs: Deljana Iossifova).

The undoing of the fence shows clearly the persistence and resilience of unprivileged urban residents left to make do within the narrow spaces in-between dissimilar fragments of the planned city (see Iossifova, Citation2013b). The following paragraphs offer a detailed account of the wealth and variety of day-to-day activities and interactions that take place between people of different background on urban borderlands—on everyday life in-between co-present “enclaves”.

Everyday life in-between “Enclaves”

In the early morning hours, around 5 o’clock, the janitor of the food market performs his daily exercises at the gates, and then opens them wide to receive meat, vegetables, eggs and other products stacked on large trucks that wait in the street. A woman delivers pigs, cut in half, on a bicycle. Young men and women—some dressed in professional sports clothing, others wearing just shorts and flip-flops—run up and down the street. Street sweepers in blue uniforms collect the garbage that has accumulated during night hours. Boys return on cargo bikes from a night of selling Beijing duck, store their equipment away, urinate against the fence of the Commercial Compound, and then hide in one of the garage-type rentals lining the street for a few hours of sleep behind a roller shutter. People are up and busy on the sidewalks, gurgling and spitting whilst brushing their teeth. At seven fifteen, the seamstress arrives, pushing the cart containing her sewing machine and carrying bags full of cloth, zippers and yarn. Residents of the Old Village empty their chamber pots at the public toilet and wash them. The cook of the soup restaurant crosses the street to collect dishes from the guards at the gate to the Gated Community, where hired taxis and cars begin to line up around 7 o’clock. Eating freshly fried bread sticks from the shop across the street, drivers polish the outsides of their employers’ automobiles. Residents of the Commercial Compound cross the street to buy breakfast. Boys and girls, carrying school bags and musical instruments, board hired taxis. Pedestrians stroll up and down the street, drivers honking and shouting in protest.

As lunchtime approaches, the market is buzzing with customers. An elegantly dressed elderly woman emerges from behind the gates to sit on the seamstress’s bench. The market janitor sweeps the side walk and takes garbage to the collection point further down the street. Residents of the Old Village are frequently dropped off at the gates to the Compound, where they wait for their taxis to take off before crossing the street and disappearing in the alleys that take them home. Residents of the Commercial Compound are frequently dropped off at the small shops along the Old Village, where they buy fruits, drinks or cigarettes before disappearing behind the Gates of the Compound. Around 2 o’clock, the sound of men and women calling for used goods, old paper and bottles from their cargo bicycles prevails. Hawkers appear and disappear, setting up stalls on either side of the street, looking for rare spots in the shadow. Around 4 o’clock, migrant mothers from the construction workers’ dormitory next to the market take their children and babies for walks. The guards waive them through the gate to the Compound as they make their way to the small polished park. Market vendors carry shopping bags for their Compound customers. Around 5 o’clock, construction workers begin to return to their dormitory, stopping at the soup restaurant for a bowl of food. The drivers of big black cars honk and flash their lights angrily at pedestrians as they crawl into the driveway which leads them to the underground parking garage of the Compound.

Rushing to their homes in the Old Village, street vendors abandon their wheelbarrows and carts on the sidewalks along the street. Young women gather along the fence along the Compound to knit and chat. At nightfall, grandparents with their grandchildren, all wearing pyjamas, leave the Commercial Compound for a late walk along the nearby Suzhou Creek. Residents of the Old Village empty and wash chamber pots, again. Shopkeepers gather behind roller shutters to watch TV with their families. Groups of teenagers meet in the street to smoke cigarettes; workers sit together on small stools, chat and nibble on freshly roasted sunflower seeds. Men and women on bicycles turn into the alleys of the Old Village, sometimes singing loudly. Gradually, the street becomes quiet, until only the clatter of mah-jongg stones can be heard.

Towards borderland urbanism

Work on enclave urbanism has provided us with an initial understanding of the genesis of gated commodity-housing compounds in Chinese cities, the varying nature of fences and gates, the extent of social networks and activity spaces of residents in gated traditional and commodity-housing compounds. Sure enough, taking on what Amin (Citation2013) calls the “telescopic” approach to the study of cities, it may appear as if these neighbourhoods are indeed disconnected, “autistic” entities, as Kaika (Citation2011) would put it. We may find, however, that albeit being patchworked—or rather, precisely because of being patchworked—“enclaves” are not at all as “unifunctional” and “monocultural” as they are usually portrayed (e.g., Wissink et al., Citation2012).

Instead, these neighbourhoods are part of the multidimensional social and material reality of cities, firmly embedded within the multi-layered urban fabric through continuously changing and evolving physical and relational linkages. The initial debate around enclave urbanism can be pushed further to see between enclaves—between the bounded spaces of a formal urban geography—to acknowledge the forces, dynamics and emerging possibilities for alternative urbanities and urbanisms on the borders, boundaries and borderlands between adjacent, sociospatially differentiated urban “enclaves”.

Borders are expressions of power and intent; they are the physical manifestations of political will and its accumulation and layering through time. They can be read as the imagined lines on the equally imagined perimeter of imagined communities; of the spaces that some call enclaves, because it is easy to think them as such based on a removed bird’s-eye view. In contrast, borderlands are spaces of contestation and dismantlement, the spaces where imposed political will is contested and where need and want emerge—because of the juxtaposition of difference, the co-presence of the other, and the emerging awareness that there are other ways of being in this world. They are not just the fixed borders or boundaries around homogeneous territories—they are the negotiated, maintained and, occasionally, celebrated spaces in-between the different. These are spaces that allow for the emergence of alternatives.

Urban borderlands can be the moments of encounter between the past, the present and the future—the historical and the envisioned, enmeshed with the continuous negotiations of power and control. Borderlands “appear and disappear with shifting social boundaries; just as symbolically as they are sometimes erected by the powerful, they are often patiently and persistently undone by those who live them in their everyday” (Iossifova, Citation2013a). They can be the shared spaces of informal, unplanned and spontaneous encounter between two or more worldviews, lifestyles, mind sets, individuals or groups. They facilitate the co-presence of that which has been “calculated, quantified, and programmed” (Lefebvre, Citation2003, p. 119)—which has been brought into life intentionally and with purpose—and the accidental other. In the context of the rapidly transforming Chinese city, rural-to-urban migrants, urban poor and a generation of middle-class professionals coexist in space and time, potentially giving rise to a new and surprising urbanity with “Chinese characteristics” (Iossifova, Citation2012b). This new urbanity can only emerge because of the implied possibilities inherent in urban borderlands. Thus, borderlands succeed in suspending existing spatial and temporal disconnections (Iossifova, Citation2010). They are “essential for the people who are present within and along them and for the formation of hybrid (or multiple) identities within the urban context; they are multidimensional and transcalar entities that have the potential to contribute to the amplification or obliteration of sociomaterial difference in the city” (Iossifova, Citation2013a).

Borderlands make obvious the triggers, conditions and effects of global systems of resource accumulation, distribution and depletion. They are not at all marginal. In fact, they are the central spaces of our cities; they amplify difference. Accepting that escalating inequality in China becomes explicit in its splintered urban fabric, we must nonetheless acknowledge the state of adjacency and co-presence of its distinct urban neighbourhoods and find answers to urgent emerging questions. Inequality matters at the local level and how people perceive—and negotiate—this condition is linked to processes of identity and identification, to the evaluation of current needs and future aspirations, and to comparison with co-present reference groups. These are just some of the emerging issues, important within and outside the context of urban China. How do co-present groups in the city delimit their real or imagined territories? How do they negotiate these boundaries through spatial tactics and strategies of co-present social interactions? How do they form and maintain individual and group identities under conditions of coexistence in continuously transforming urban environments? Finding answers to these questions will inform urban policy, design and planning. Future research should therefore seek to understand the role of urban borderlands not just in the perception of inequality, but also in processes exacerbating or soothing the condition itself.

With this paper, I call for a re-engagement of scholarship with the realities of our cities—in China and elsewhere. We need to move beyond superficial inquiries and theories that seem written in stone. I argue that rather than looking explicitly at stratifying and segregating effects of urban “enclaves”—and conceiving of cities along the lines of previous notions of post-modern urbanism and “patchwork city” (Dear & Flusty, Citation1998) or “splintering urbanism” (Graham & Marvin, Citation2001)—we should broaden our scope to include the ways in which livelihoods, identities and coexistence are negotiated in-between supposed enclaves. Such scholarship, studying the very joint lines, the breaks and folds where top-down planning and bottom-up agency converge and where alternative futures become possible, will contribute to a more holistic understanding of emerging cities in China and beyond. This borderland urbanism reads and protects the spaces in-between as moments of assemblage—of actors, actions and activities across social, temporal, cultural, economic or plain spatial divisions; it includes the possibility of the alternative, the otherwise.

Notes

1. In the interest of the privacy of participants in this research, the real names of the areas in question as well as of research participants, where applicable, have been replaced.

References

- Amin, Ash (2013). Telescopic urbanism and the poor. City, 17(4), 476–492.

- Angotti, Tom (2013). The new century of the metropolis: Urban enclaves and orientalism. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Becker, Heidede, & Keim, Dieter K. (1975). Wahrnehmung in der städtischen Umwelt, möglicher Impuls für kollektives Handeln. Berlin: Kiepert.

- Boano, Camillo, & Martén, Ricardo (2013). Agamben’s urbanism of exception: Jerusalem’s border mechanics and biopolitical strongholds. Cities, 34, 6–17.

- Boyce, Christopher J., Brown, Gordon D. A., & Moore, Simon C. (2010). Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 21(4), 471–475.

- Bray, David (2005). Social space and governance in urban China: The Danwei system from origins to reform. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Breitung, Werner (2012). Enclave urbanism in China: Attitudes towards gated communities in Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 33(2), 278–294.

- Caldeira, Teresa P. R. (1996). Fortified enclaves: The new urban segregation. Public Culture, 8(2), 303–328.

- Cheng, Tienjun, & Selden, Mark (1994). The origins and social consequences of China’s hukou system. The China Quarterly, 644–668. doi:10.1017/S0305741000043083

- Dear, Michael, & Flusty, Steven (1998). Postmodern urbanism. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88(1), 50–72.

- Dong, Hui, & Zha, Minjie (2009, July 24). Beaten vendor in intensive care. Shanghai Daily Online Edition. Retrieved from http://www.shanghaidaily.com/Metro/health-and-science/Beaten-vendor-in-intensive-care/shdaily.shtml

- Douglass, Mike, Wissink, Bart, & van Kempen, Ronald (2012). Enclave urbanism in China: Consequences and interpretations. Urban Geography, 33(2), 167–182.

- Fan, C. Cindy (2008a). China on the move: Migration, the state, and the household. London: Routledge.

- Fan, C. Cindy (2008b). Migration, hukou, and the city. In S. Yusuf & T. Saich (Eds.), China urbanizes: Consequences, strategies, and policies (pp. 65–89). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Fan, C. Cindy, & Wang, Wenfei Winnie (2008). The household as security: Strategies of rural–urban migrants in China. In I. L. Nielsen & R. Smyth (Eds.), Migration and social protection in China (pp. 205–243). Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific Publishing.

- Fried, Marc (1963). Grieving for a lost home. In L. J. Duhl & J. Powell (Eds.), The urban condition: People and policy in the metropolis (pp. 151–171). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Gao, Helen (2010, October 3). Migrant “villages” within a city ignite debate. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/04/world/asia/04beijing.html?_r=2

- Goodkind, Daniel, & West, Loraine A. (2002). China’s floating population: Definitions, data and recent findings. Urban Studies, 39(12), 2237–2250.

- Graham, Stephen, & Marvin, Simon (2001). Splintering urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. London: Routledge.

- Graumann, Carl Friedrich (1983). On multiple identities. International Social Science Journal, 35(96), 309–321.

- Graumann, Carl Friedrich (1988). Towards a phenomenology of being at home. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference of the IAPS: Looking Back to the Future, Delft, Netherlands.

- He, Shenjing (2007). State-sponsored gentrification under market transition: The case of Shanghai. Urban Affairs Review, 43(2), 171–198.

- He, Shenjing (2013). Evolving enclave urbanism in China and its socio-spatial implications: The case of Guangzhou. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(3), 243–275.

- Ho, Wing Chung, & Ng, Petrus (2008). Public amnesia and multiple modernities in Shanghai: Narrating the postsocialist future in a former socialist “Model Community”. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 37(4), 383–416.

- Hogan, Trevor, Bunnell, Tim, Pow, Choon-Piew, Permanasari, Eka, & Morshidi, Sirat (2012). Asian urbanisms and the privatization of cities. Cities, 29(1), 59–63.

- Honig, Emily (1989). The politics of prejudice: Subei people in republican-era Shanghai. Modern China, 15(3), 243–274.

- Honig, Emily (1990). Invisible inequalities: The status of Subei people in contemporary Shanghai. The China Quarterly, 122, 273–292.

- Honig, Emily (1992). Creating Chinese ethnicity: Subei people in Shanghai, 1850–1980. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Imai, Heide (2013). The liminal nature of alleyways: Understanding the alleyway roji as a “Boundary” between past and present. Cities, 34, 58–66.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2009a). Blurring the joint line? Urban life on the edge between old and new in Shanghai. URBAN DESIGN International, 14(2), 65–83.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2009b). Negotiating livelihoods in a city of difference: Narratives of gentrification in Shanghai. Critical Planning, 16, 98–116.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2010). WP/39 identity and space on the borderland between old and new in Shanghai: A case study. In UNU-WIDER (Ed.), UNU-WIDER Working Paper Series (Vol. 2010). Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2012a). Place and identity on the borderland between old and new in Shanghai: A case study. In J. Beall, B. Guha-Khasnobis, & R. Kanbur (Eds.), Urbanization and development in Asia: Multidimensional perspectives (pp. 73–94). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2012b). Shanghai borderlands: The rise of a new urbanity? In T. Edensor & M. Jayne (Eds.), Urban theory beyond the west: A world of cities (pp. 193–206). London: Routledge.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2013a). Searching for common ground: Urban borderlands in a world of borders and boundaries. Cities, 34, 1–5.

- Iossifova, Deljana (2013b). Beyond scarcity: Making space in the city. CityCity Magazine, 1, 20–23.

- Kaika, Maria (2011). Autistic architecture: The fall of the icon and the rise of the serial object of architecture. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(6), 968–992.

- Karaman, Ozan, & Islam, Tolga (2012). On the dual nature of intra-urban borders: The case of a Romani neighborhood in Istanbul. Cities, 29(4), 234–243.

- Knight, John (2013). Inequality in China: An overview (C. B. U. Partnerships, Development Economics Vice Presidency, Trans.) In Policy research working paper (Vol. 6482). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Knight, John, & Ding, Sai (2012). China’s remarkable economic growth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Knight, John, & Gunatilaka, Ramani (2011). Does economic growth raise happiness in China? Oxford Development Studies, 39(1), 1–24.

- Lalli, Marco (1992). Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(4), 285–303.

- Lefebvre, Henri (2003). The urban revolution. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Li, Bingqi (2004). Urban social exclusion in transitional China. CASEpaper 82. Retrieved from http://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/case/cp/casepaper82.pdf

- Li, Si-ming, Zhu, Yushu, & Li, Limei (2012). Neighborhood type, gatedness, and residential experiences in Chinese cities: A study of Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 33(2), 237–255.

- Li, Zhigang, & Wu, Fulong (2013). Residential satisfaction in China’s informal settlements: A case study of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 34(7), 923–949.

- Mobrand, Erik (2006). Politics of cityward migration: An overview of China in comparative perspective. Habitat International, 30(2), 261–274.

- Newman, David (2003). On borders and power: A theoretical framework. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 18(1), 13–25.

- Newman, David, & Paasi, Anssi (1998). Fences and neighbours in the postmodern world: Boundary narratives in political geography. Progress in Human Geography, 22(2), 186–207.

- Proshansky, Harold M. (1978). The city and self-identity. Environment and Behavior, 10(2), 147–169.

- Rapoport, Amos (1982). The meaning of the built environment. A nonverbal communication approach. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Roy, Ananya (2011a). Re-forming the megacity: Calcutta and the rural–urban interface. In A. Sorensen & J. Okata (Eds.), Megacities (Vol. 10, pp. 93–109). Berlin: Springer.

- Roy, Ananya (2011b). Urbanisms, worlding practices and the theory of planning. Planning Theory, 10(1), 6–15.

- Shen, Jianfa, & Huang, Yefang (2003). The working and living space of the “floating population” in China. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 44(1), 51–62.

- Shen, Jie, & Wu, Fulong (2012). The development of master-planned communities in Chinese suburbs: A case study of Shanghai’s thames town. Urban Geography, 33(2), 183–203.

- Solinger, Dorothy J. (1995). The floating population in the Cities: Chances for assimilation. In D. S. Davis, R. Kraus, B. Naughton, & E. J. Perry (Eds.), Urban spaces in contemporary China: The potential for autonomy and community in post-mao China (pp. 113–139). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Solinger, Dorothy J. (1999). Contesting citizenship in urban China: Peasant migrants, the state, and the logic of the market. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sommer, Robert (1969). Personal space: The behavioral basis of design. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Stokols, Daniel, & Shumaker, Sally A. (1981). People in places: A transactional view of settings. In J. H. Harvey (Ed.), Cognition, social behavior, and the environment (pp. 441–488). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Thum, Karl (1981). Soziale Bindungen an das Wohnviertel. In E. Bodzenta, I. Speiser, & K. Thum (Eds.), Wo sind Grossstädter daheim?: Studien über Bindungen an das Wohnviertel (pp. 33–108). Wien: Böhlau.

- Treinen, Heiner (1965). Symbolische Ortsbezogenheit. Eine soziologische Untersuchung zum Heimatproblem. Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 17, 73–97.

- van Praag, Bernard (2011). Well-being inequality and reference groups: An agenda for new research. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(1), 111–127.

- Wang, Donggen, Li, Fei, & Chai, Yanwei (2012). Activity spaces and sociospatial segregation in Beijing. Urban Geography, 33(2), 256–277.

- Wang, Ya Ping (2004). Urban poverty, housing and social change in China. London: Routledge.

- Weichhart, Peter (1999). Spatial identity (two-day intensive course). Alexander von Humboldt Lectures in Human Geography. Retrieved from http://www.ru.nl/gpm/@800980/pagina/

- Whyte, Martin (2010). Myth of the social volcano: Perceptions of inequality and distributive injustice in contemporary China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Window of China (2008, December 9). Financial crisis forces China’s migrants back home for work. Special Report: Global Financial Crisis. Retrieved from http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-12/09/content_10478975.htm

- Wise, J. Mcgregor (2005). Assemblage. In C. J. Stivale (Ed.), Gilles Deleuze: Key concepts (pp. 77–87). Montreal: McGill Queens University Press.

- Wissink, Bart, van Kempen, Ronald, Fang, Yiping, & Li, Si-ming (2012). Introduction—Living in Chinese enclave cities. Urban Geography, 33(2), 161–166.

- Wu, Fulong (2005). Rediscovering the “Gate” under market transition: From work-unit compounds to commodity housing enclaves. Housing Studies, 20(2), 235–254.

- Wu, Fulong, Zhang, Fangzhu, & Webster, Chris (2013a). Rural migrants in urban China: Enclaves and transient urbanism. London: Routledge.

- Wu, Fulong, Zhang, Fangzhu, & Webster, Chris (2013b). Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area. Urban Studies, 50(10), 1919–1934.

- Wu, Rufina. (2007). Beijing, underground ( Master of Architecture Master thesis). University of Waterloo, Cambridge.

- Wu, Rufina, & Canham, Stefan (2008). Portraits from above: Hong Kong’s informal rooftop communities. Berlin: Peperoni Books.

- Wu, Weiping (2002). Migrant housing in urban China: Choices and constraints. Urban Affairs Review, 38(1), 90–119.

- Wu, Weiping (2006). Migrant intra-urban residential mobility in urban China. Housing Studies, 21(5), 745–765.

- Wu, Weiping (2008). Migrant settlement and spatial distribution in metropolitan Shanghai. The Professional Geographer, 60(1), 101–120.

- Yang, Lifei (2008, October 13). Snack vendors get booted off city streets. Shanghai Daily Online Edition. Retrieved from http://www.shanghaidaily.com/article/?id=376658&type=Metro

- Yip, Ngai (2012). Walled without gates: Gated communities in Shanghai. Urban Geography, 33(2), 221–236.

- Zhang, Li (2001). Strangers in the city: Reconfigurations of space, power, and social networks within China’s floating population. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Zhang, Li (2002). Spatiality and urban citizenship in late socialist China. Public Culture, 14(2), 311–334.

- Zhang, Li, Zhao, Simon X. B., & Tian, J. P. (2003). Self-help in housing and chengzhongcun in China’s urbanization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(4), 912–937.

- Zheng, Siqi, Long, Fenjie, Fan, C. Cindy, & Gu, Yizhen (2009). Urban villages in China: A 2008 survey of migrant settlements in Beijing. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50(4), 425–446.

- Zhu, Yushu, Breitung, Werner, & Li, Si-ming (2012). The changing meaning of neighbourhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Studies, 49(11), 2439–2457.