ABSTRACT

Recent research has pointed to increasingly divided housing access across advanced economies. This reflects growing labor market inequality and rising intergenerational divides amplifying the importance of parental resources. At the same time, an increasing spatial polarization of housing markets has driven divergence between high-gain versus low-gain submarkets. This paper confronts how divided access to housing collides with growing spatial inequality in housing markets. The research turns to the Netherlands, drawing on full-population register data. First, GIS mapping exposes spatial polarization in house-value development. Second, household-level modeling demonstrates the impact of income, employment position and parental wealth in divided access to housing submarkets. Taken together, spatial polarization and differentiated access appear fundamental to driving inequalities in housing wealth accumulation.

Introduction

Housing matters. Housing is fundamental to shaping individual life course trajectories, being crucial to the attainment of independence and family formation (William & Dieleman, Citation1996). It is also central toward household economic security and wealth strategies (Aalbers & Christophers, Citation2014; Ansell, Citation2014; Doling & Ronald, Citation2010). Across many advanced economies, the gradual and uneven erosion of welfare-state safety nets (Brenner, Peck, & Theodore, Citation2010) alongside labor market restructuring (Bell & Blanchflower, Citation2011; Stockhammer, Citation2013) have only increased the centrality of housing assets toward household economic security. On a societal level, housing is further key in producing and reproducing various dimensions of inequality (Desmond, Citation2016). In particular, differentiated access to homeownership and property wealth accumulation appear central to shaping societal inequalities.

Homeownership ideology over the past half century or so has endorsed mass homeownership as a means toward widespread asset accumulation and economic redistribution (Ronald, Citation2008; Kohl, Citation2018; Arundel & Ronald, Citation2019). Recent developments, however, and especially since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), have instead pointed toward starkly increasing housing inequalities in many countries (Arundel, Citation2017; Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015; Lennartz, Arundel, & Ronald, Citation2016).

On the one hand, divides in housing outcomes reflect other dimensions of rising socio-economic inequality. Labor markets across advanced economies have been characterized by a “hollowing out of the middle classes” with growing shares in more precarious employment (Kalleberg, Citation2018; Milanovic, Citation2016; Nolan et al., Citation2014; OECD, Citation2016) impacting housing access (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017). Relatedly, recent scholarly work has singled out emerging generational divides, with younger populations in many countries struggling to enter the housing market (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Lennartz et al., Citation2016). This has seemingly increased the role of parental financial support in housing market entry (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015; McKee, Citation2012).

On the other hand, we argue housing markets are not only differentiated across populations but are also divided across space. Housing asset accumulation is inherently spatial. Recent transformations of housing markets – and land values that underlie theseFootnote1 – have seemingly only intensified spatial divides in the face of ongoing processes of housing financialization and rising flows of capital invested in particular real estate markets (Aalbers, Citation2016; Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016). In a context of spatial polarization, where booming and struggling property markets coexist, it is not only a matter of who is able to buy, but also where one buys may profoundly affect asset accumulation.

In understanding dynamics of rising housing inequality, this paper brings together how housing markets are divided across populations and space. While a substantial body of research has looked at determinants of initial access to housing markets (see Dewilde, Hubers, & Coulter, Citation2018; Filandri & Bertolini, Citation2016; Helderman & Mulder, Citation2007; Kurz & Blossfeld, Citation2004), there is only limited understanding on differentiated wealth accumulation potential among homeownership entrants, and the spatial nature of such differences. Past research in the UK has pointed to aggregate associations between higher social class and increased housing capital gains (Hamnett, Citation1999; Murie & Forrest, Citation1980) alongside recognition that such patterns can be geographic in nature (Forrest & Murie, Citation1989; Hamnett, Citation1992). A recent Swedish study further posited that an important determinant for higher-income individuals in achieving greater capital gains were their residential trajectories across space (Wind & Hedman, Citation2018). Nonetheless, direct research into how space structures unequal housing wealth accumulation has been limited. This article addresses this knowledge gap through an examination of key factors that shape young-adult households’ likelihood to buy property in higher versus lower-gain locations – reflecting divergent potential for housing wealth accumulation.

The article turns to the salient case of the Netherlands to empirically investigates these processes. To do so, the paper employs an integrated perspective tackling, on the one hand, spatial inequality in house-value developments in the country between 2006 and 2018, and on the other, how economic position and parental support structure young adultFootnote2 households’ access to housing.

The paper begins outlining, first, contemporary developments that are seemingly promoting growing housing market spatial polarization and, second, household-level determinants that may structure divided access to such spatially-differentiated housing submarkets. We subsequently introduce the context of the Netherlands and its particular relevance toward examining spatial dynamics of divided housing wealth accumulation. Drawing on longitudinal and individual-level register data from Statistics Netherlands, the empirical research thus presents two primary components: (1) an examination of nation-wide trends of spatial polarization in neighborhood-level housing value developments, and (2) modeling how household economic position and parental support structure entry into divergent neighborhood submarkets. The discussion of the results brings attention to the fundamental significance of these interacting dynamics in driving increasing societal wealth inequalities.

Literature

The Spatial Polarization of Housing Markets

Location plays an essential role in housing asset accumulation. While this may be a self-evident real estate trope, spatial divisions in housing markets are seemingly on the rise. Underlying rising spatial inequality are both increased and increasingly uneven flows of capital into housing. These dynamics are linked to the marketization and “financialization” of housing (Aalbers, Citation2016; Aalbers & Christophers, Citation2014). Financialization has promoted rising investment in property, expanded mortgage credit, and an embedding of real estate into global circuits of capital (Aalbers, Citation2008; Aalbers & Christophers, Citation2014; Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016; Schwartz & Seabrooke, Citation2008). On a macro-level, financialization and expanded access to (cheap) credit essentially inflates the values of collateral assets pushing up property values (Stiglitz, Citation2012). Investment in property markets is further driven by lower yields on other investment portfolios (Green & Bentley, Citation2014) and processes of capital shifting from production to the built environment, particularly in urban property markets (Christophers, Citation2011; Harvey, Citation1989). These dynamics see house value inflation – particularly so in certain markets – promoting both growing wealth for market-insiders and rising affordability barriers for new entrants (Allegré & Timbeau, Citation2015).

Increasing spatial polarization plays out on various scales, for example between regions, between cities but also at the very local level of neighborhoods. At higher spatial scales, trends point toward the channeling of capital into select first and second-tier global cities (Sassen, Citation1991, Citation2014). These property markets are targeted for both returns and as a relatively secure store of capital (Fernandez, Hofman, & Aalbers, Citation2016). Conversely, many suburban areas see growing poverty rates (Cooke & Denton, Citation2015; Hochstenbach & Musterd, Citation2018) with peripheral (shrinking) regions confronted with disinvestment and capital shifting away (Martinez‐Fernandez, Audirac, Fol, & Cunningham‐Sabot, Citation2012).

The changing geography of capital flows, has gone hand in hand with state restructuring. Many states have shifted toward market-enabling entrepreneurial policies that privilege winner areas (Brenner, Citation2004; Harvey, Citation1989), likely exacerbating spatial polarization (Etherington & Jones, Citation2009). This is evidenced in contexts such as the Netherlands where more centralized power facilitated national policy toward central-city growth (Terhorst & Van de Ven, Citation1995).

Housing market dynamics are mutually reinforced by selective residential mobility, further entrenching concentrated affluence and disadvantage through persistent patterns of socio-economic segregation (Sampson, Citation2012; Sampson & Sharkey, Citation2008). Recent studies point to an increase in income segregation across European and American urban areas (Bischoff & Reardon, Citation2014; Musterd, Marcińczak, Van Ham, & Tammaru, Citation2017). Such studies focus on population distributions but similar patterns likely apply to housing market divisions, such as measured by changing property values.

While it is broadly understood that housing markets are inherently spatial, research is lacking on how contemporary processes may be driving increasing spatial inequality. The first empirical focus of the paper thus confronts this issue through an investigation of recent house value dynamics across neighborhood-level housing submarkets in the Netherlands. Given the contemporary housing market dynamics discussed herein, we expect to find rising spatial inequality in rates of house value appreciation (Hypothesis 1).

Determinants of divided access to housing

Household economic position

Understanding housing inequality cannot be separated from the underlying factors that structure unequal access to the housing market. Clearly, economic position fundamentally shapes both the ability to access homeownership and the type of (spatial) submarket that households are able to invest in. Of course, housing preferences and decisions are also influenced by a host of interrelated social and cultural factors (Bourdieu, Citation2005; Ley, Citation1996). Nevertheless, a sufficiently high income and degree of economic security appear necessary to access homeownership in the first place, while a particularly strong economic position is needed to enter high-demand submarkets.

While persistent spatial inequality is important, local housing market change, notably gentrification, may also contribute to economic sorting of housing wealth potential. Especially more affluent population groups are able to capitalize on rent gaps (Smith, Citation1979), using their capital and access to mortgage credit to close such gaps (Aalbers, Citation2007; Wyly & Hammel, Citation1999). Higher-income newcomers may thus be able to buy into the most profitable niches.

Beyond income, employment position is likely crucial to housing access. Labor market restructuring over recent decades has seen a growing flexibilization of employment with growing shares in non-typical and precarious contracts, such as temporary and part-time positions (Biegert, Citation2014; Emmeneger, Citation2012). Employment security is important to homeownership access as evidenced in research across European countries (see Dotti Sani & Acciai, Citation2018). While there is limited research on employment security and differentiated outcomes among homeowners, a recent study in the Netherlands revealed strong correlations between stable employment contracts and being a homeowner in more urban and higher-gain housing markets (Arundel & Ronald, Citation2019).

These dynamics inform our expectations in the relation between divided access and spatially unequal housing markets. We thus posit that access to higher-gain spatial submarkets would be associated with both higher household income (Hypothesis 2a), as well as more secure employment positions (Hypothesis 2b).

Parental support

Young adults’ access to the housing market can be further structured by resources beyond their immediate household. Here, parental support may play a crucial – and increasing – role in structuring housing opportunities. There is substantial evidence of rising intergenerational inequality. Across many countries, older cohorts, albeit by no means a uniform group, were more likely to benefit from favorable past labor conditions and be shielded from market reforms (Biegert, Citation2014; Häusermann & Schwander, Citation2012; OECD, Citation2019b). These advantages intersected with easier homeownership access and subsequent house-value increases, resulting in substantial shares of older cohorts with (substantial) accumulated property wealth (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015). On the other hand, younger cohorts have faced labor market deterioration alongside growing housing unaffordability and, post-crisis, more restricted access to credit. Data from the United States and Europe have shown long-term decreases in relative incomes for young adults (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Bell & Blanchflower, Citation2011; Hills, Cunliffe, Gambaro, & Obolenskaya, Citation2013).

The concentration of housing wealth among older generations and their more favorable labor market position ostensibly enhances the role of intergenerational support in young adult housing trajectories, especially in purchasing a home (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015). Intergenerational transfers may take many forms: from direct financial assistance, acting as guarantors in credit access, to in-kind support through childcare or co-residence allowing increased savings (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015; Helderman & Mulder, Citation2007; Öst, Citation2012). Parents may also lend other support, such as resourceful social networks and specific housing knowledge (Hochstenbach & Boterman, Citation2017). Finally, the intergenerational transmission of homeownership is more broadly related to social-class reproduction (Friedman, Laurison, & Miles, Citation2015), socialization (Rowlands & Gurney, Citation2000), and normative (classed) expectations of transitions to adulthood (Druta & Ronald, Citation2017). Given divergent parental resources, intergenerational support reproduces socio-economic and intra-generational divisions (Christophers, Citation2018).

Beyond homeownership entry, support from parents can be fundamental in structuring what housing is purchased. Parental resources may allow young adults to access more expensive housing segments (Spilerman & Wolff, Citation2012). This also influences where young adults are able to buy. Previous research, in Sweden, the UK and the Netherlands, shows how parental background plays an important role in the residential location of young adults (Coulter, Citation2017; Hochstenbach, Citation2018; Van Ham, Hedman, Manley, Coulter, & Östh, Citation2014).

Given these dynamics, we expect higher levels of parental resources to be associated with entering higher-gain spatial submarkets (Hypothesis 3a). As we are able to differentiate between housing and non-housing parental wealth, we further expect the latter, as a more “liquid” asset, to display a stronger association (Hypothesis 3b) implying the particular significance of the financial mechanism of parental support.

Other determinants

Beyond our primary focus on economic position and parental resources, various other household characteristics are expected to play a role in differentiated access to higher or lower-gain submarkets (subsequently controlled for in our analyses). Of key importance is educational attainment which would be expected to intersect with spatial residential trajectories, given that education and higher-skilled employment opportunities tend to concentrate in larger cities. More broadly, higher-educated young adults display a stronger urban orientation and, within cities, typically prefer centrally-located gentrifying neighborhoods (Boterman, Citation2012; Ley, Citation1996). These areas are also commonly higher-gain submarkets. Additionally, household type would likely play a role in differentiated housing trajectories, such as couples or households with children exhibiting different housing preferences and spatial residential trajectories (Mulder & Hooimeijer, Citation1999; Lersch & Dewilde, Citation2015). It is further important to consider how the number of siblings may moderate parental support (Albertini & Kohli, Citation2012). Common socio-economic variables of gender, age and ethnicity that have been shown to shape housing market entry (see Filandri & Bertolini, Citation2016; Lersch & Dewilde, Citation2015; Kurz & Blossfeld, Citation2004) may further intersect with particular (spatial) housing preferences and opportunities among homeowners.

In sum, our research looks at how dynamics of housing market spatial inequality, economic position, and differentiated access to parental resources may structure access to more or less profitable housing submarkets. While we argue for the crucial importance of understanding the intersect of these dynamics, we caution against implying a direction of causality. Rather, we see spatially-differentiated housing markets and divided access as mutually reinforcing: population sorting across space may further drives property value divergences and vice versa. Furthermore, rather than absolute outcomes of housing wealth inequality, we are concerned with examining rates of appreciation. In other words, the research focuses on rates of change in housing values regardless of the total size of housing assets (or, relatedly, the share owned versus the share mortgaged). While absolute measures of housing wealth inequality have been the focus of some relevant recent research (Wind, Lersch., & Dewilde, Citation2017; Arundel, Citation2017; Appleyard & Rowlingson, Citation2010; Hochstenbach Citation2018), we argue that understanding how rates of return in housing wealth are differentiated across socio-economic lines is crucial to disentangling the mechanisms driving housing wealth inequality.

Study area and methods

The Dutch context

Our empirical focus turns to the case of the Netherlands, which presents unique characteristics that make it particularly relevant for examining dynamics of housing wealth inequality as well as reflecting similar trends occurring across advanced economies (Aalbers, Citation2016; Hay, Citation2004). The Dutch case is particularly salient, having experienced strong housing marketization and financialization in recent decades. While social rent traditionally accommodated large population segments, its ongoing gradual decline has seen access increasingly restricted (Musterd, Citation2014). The share of housing associations dwellings saw a decline from about 41% in 1990 to 35% in 2006 (Lijzenga & Boertien, Citation2016) and down to 29% in 2018 (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019a). At the same time, an expansion in market housing (both through homeownership and private rent), alongside reduced tenant protection (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019a) allows increasing social differentiation and spatial sorting in the housing market. The homeownership share grew from 46% in 1990 (Lijzenga & Boertien, Citation2016) to 53.7% in 2006 and 56.7% in 2018 (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). The Netherlands represents a highly financialized housing market – displaying the highest European mortgage-debt-to-GDP rates (EMF, Citation2018) – with long-term house price inflation fueled by high levels of credit access (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016). The Dutch homeownership market is also supported by generous mortgage tax deductions (Dutch: hypotheekrenteaftrek) which further inflate house values. Despite credit access being tightened following the GFC, recent years have seen increased capital flows into real estate by private households and institutional investors (Aalbers, Bosma, Fernandez, & Hochstenbach, Citation2018).

Although the Netherlands is characterized by relatively modest income inequality, it exhibits particularly high levels of wealth inequality (Reuten, Citation2018). The highly-financialized Dutch housing market has been identified as a key explanation for these wealth disparities (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016; Van Bavel & Salverda, Citation2014). Beyond housing markets, the role of the Dutch state has seen a shift from policies that targeted disadvantaged areas for investment (Musterd & Andersson, Citation2005) toward increasingly prioritizing already well-performing urban neighborhoods (Hochstenbach, Citation2017; Van Gent, Citation2013), further contributing to spatial polarization. Besides the particularities of the Dutch case, it can also be placed within a context of similar trends occurring across advanced economies which have seen ongoing financialization (Aalbers, Citation2016), long-term house value inflation (OECD, Citation2019a), uneven development (Brenner, Citation2004) and recent rises in housing inequality (Lennartz et al., Citation2016). In these ways, the examination of the Dutch context provides both a salient case on its own as well as informing potential dynamics across other contexts facing similar housing market processes. Finally, the Netherlands provides particularly valuable data opportunities through access to full-population and full-dwelling stock longitudinal registers.

The empirical research consists of two primary foci: (1) examining nation-wide trends of neighborhood-level housing value developments, and (2) modeling how household economic position and parental support structure entry into different asset-accumulation neighborhoods. In other words, the paper investigates polarization between “hot” and “cold” property markets across space as well as how new home-buyers sort into these different spatial submarkets defined on the basis of neighborhood boundaries. This paper draws on data from the System of Social-statistical Datasets (SSD) of Statistics Netherlands, which combines different register datasets. It contains data on the full population registered in the Netherlands, as well as dwelling-level information for the total housing stock. All data are geocoded and longitudinal, making it possible to follow people over space and time.

Spatial analysis of housing value dynamics

In order to assess spatial housing market polarization, it is necessary to measure house-value developments at low spatial scales. We draw on dwelling-level registry data to determine property values for each year in the 2006–2018 period (also see Hochstenbach & Arundel, 2019). Information on dwelling size is not available, so we rely on total values. Only those dwellings that have real estate information available for all years are included in our analyses. We exclude demolished and newly-built dwellings, as well as those with missing data in any of the years. This leaves a “stable” housing stock, which we use to determine average neighborhood-level property values. Property values (Dutch: Waardering Onroerende Zaken [WOZ]) are based on building characteristics, official valuations, and recent selling prices of nearby properties (Rijskoverheid, Citation2018). There is a strong correlation between house values and house prices, but differences exist: rental units also get a value assigned, and a time lag exists as changing sale prices take one or two years to translate into changes in assessed values.

In defining small-scale housing submarkets, we follow the Statistics Netherlands country-wide neighborhood classification (Dutch: buurten), typically delineated by natural boundaries, waterways and major infrastructure. Using the 2016 neighborhoods, boundaries are stable over time. To comply with SSD privacy requirements, we exclude all neighborhoods where less than ten (stable) dwellings had values assigned. We exclude a total of 1,678 neighborhoods, mostly scarcely populated rural, industrial, or newly developed areas, and a very small number due to missing data.Footnote3 This leaves a total of 11,145 neighborhoods with 5,859,464 stable dwellings in our analyses with an average of 526 dwellings per neighborhood (minimum 10, maximum 11,381).

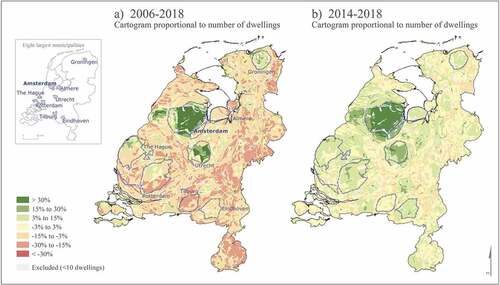

We measure inflation-corrected house-value development at the neighborhood level in percentage change over different periods, including 2006–2018 (the full data range) and 2014–2018 (a post-crisis period of increasing house values). GIS analysis is applied to map uneven developments in detail. The resulting maps are presented as cartograms with neighborhoods intentionally distorted proportional to dwelling numbers using the Gastner-Newman diffusion algorithm (Gastner & Newman, Citation2004). This graphically corrects for the relative size of property markets and prevents misleading overrepresentation of larger but sparsely-populated rural areas at the expense of smaller dense urban neighborhoods.

Subsequently, we analyze trends in housing market polarization at both the dwelling and neighborhood level. We calculate house-value ratios by comparing the highest value (i.e. top 10% most expensive) with the lowest value neighborhoods (i.e. bottom 10%). Increasing ratios over time indicate a stronger house-value polarization. A Gini coefficient over the years is further measured to capture spatial inequality trends. The Gini is a common measure to capture inequality, ranging from 0 (full equality) to 100 (complete inequality). A higher coefficient thus indicates greater differences between neighborhoods. We calculate these measures at the dwelling-level to analyze the uneven distribution of individual house values across the country. At the neighborhood-level, the measures assess the degree of spatial inequality between low-value and high-value neighborhoods. In calculating the neighborhood-level measures, we weight for differences in neighborhood size.

Regression modeling

The second empirical part of this paper looks into the question of where – in which neighborhood property markets – young adult households buy a home. The key question is to what extent young adults of different economic and parental support characteristics sort into property markets with higher or lower asset accumulation potential.

We first address this question through descriptive analyses, focusing on the characteristics of young adults moving into the different neighborhoods. We do so by splitting our sample across constructed neighborhood decile groups based on the 2014–2018 house-value development. To account for differences in neighborhood size, decile breaks are weighted by number of dwellings. The top decile includes the 10% dwellings with the strongest neighborhood house-value developments: the “hottest” property markets nationally.

Subsequently, we estimate multilevel random-effects regression models with the 2014–2018 neighborhood-level percentage change in property values as dependent variable. Key predictor variables concern labor market position and parental wealth background, as described below. Our models include two levels: the individual level and a spatial control. While we don’t include level-two variables in our model, we acknowledge that our population is nested in several regional housing submarkets. Within these submarkets, different housing-market conditions and price developments may exist, influencing who is able to gain access at all, and into high or low-gain areas. Our spatial control is at the provincial level. The twelve provinces roughly capture regional submarkets, while also preserving intra-regional variation.

Research population

Our analyses focus on young-adult households that we classify as “new” entrants having entered homeownership at any point in 2013 – thus the new entrants “capturing” the subsequent neighborhood house value change from 2014–2018 that forms our dependent variable. The selected entrant year represents the bottom of the Dutch housing and economic slump, as house prices reached their low point before picking up again. Low house prices may have given opportunities for new entrants, but stronger mortgage lending criteria and economic precarity may restrict post-crisis access. All analyses are at the household level, because this is where economic resources are bundled and translate into housing market purchasing power. We only include households with one or two adult members, where the oldest household member is aged between 16 and 39. Only households where all members moved residence are included to ensure we are dealing with a new purchase, rather than people moving in together. Our selection only includes young adults who were previously tenants or living in the parental house, but who are owner-occupiers after moving. In most cases these young adults will be first-time buyers, although we cannot rule out that this includes returns into owner occupancy. As we are interested in the role of parental resources, only households where the wealth position of at least one parent is known are included. Additionally, a total of 2.4% of households (N = 1,462) were removed due to missing/extreme values on household/individual level while 7.4% (N = 4,438) were removed due to missing/extreme values on dependent variable (house-value change). After narrowing down our population, and excluding cases with missing and extreme values, our population consists of 53,956 households (see for descriptive statistics).

Table 1. Descriptive data (Household population in the multivariate analysis N = 53,956)

Household economic position indicators

We include various indicators of economic position in our analyses, considering both gross household income and employment situation in 2013. Employment situation is assigned for the household’s main earnerFootnote4 and is derived from tax registers. We distinguish four employment situations, based on highest source of income over the year: employed, self-employed, receiving benefits, receiving student bursaries. We subsequently draw on insurance registers to determine whether employed main earners are on a permanent or temporary contract.Footnote5 In a small number of cases, employment status is categorized unknown, or not applicable (i.e. for major shareholders, or company directors). It should be acknowledged that our analyses focus on home-buyers which tend to be a relatively more well-off group, while those in rent or in the parental home – skewing lower on socio-economic status – are not part of the research population.

Parental resources

Our analyses also focus on the role of parental resources. Although we don’t have data available on actual intergenerational financial transfers, we are able to include parental wealth positions. We distinguish between net parental housing wealth as well as net other non-housing forms of parental wealth, which capture more easily transferable (liquid) assets such as savings. These net wealth measures subtract all outstanding debts, including mortgages.

Parental wealth is summed for all parents of a household as the assumption is that couples with affluent parents on both sides may receive more support than those with affluent parents only on one side. In other words, we measure total wealth (minus debts) of all parents of all adult household members.Footnote6 Where parents are separated, parental wealth is summed for both parents. When wealth is missing for a parent (i.e. due to death or a parent living abroad), only assets of the other parent are used.

Young-adult households’ own wealth position may also play a role, but unfortunately our data only allows us to include household wealth post-moving. At this point, first-time buyers may have depleted their savings to buy and maximized their mortgage capacity. Including pre-moving wealth is not possible, as we cannot distinguish personal wealth from parental wealth those living in the parental home.

Results

Spatial Polarization of Housing Markets

The spatial analysis examines the uneven development of housing values across the Netherlands over the 2006–2018 period per neighborhood submarkets. This period includes rising average values until about 2010 with a subsequent stagnation then decline in the aftermath of the GFC. Only after 2015, average house values start increasing again (see ).

Table 2. Inequality measures between neighborhoods based on average property values

National trends mask strong spatial variations in property value dynamics. GIS mapping reveal stark spatial inequality in house-value development per neighborhoods (). Between 2006 and 2018 most areas of the country show neighborhood declines while a few specific property markets have, on the contrary, displayed significant property value appreciation ()). Rising property values – i.e. “hot market” neighborhoods – are mostly concentrated in a limited number of larger and medium-sized cities, namely Amsterdam, Utrecht, Groningen and HaarlemFootnote7.

Figure 1. Change in inflation-adjusted house values per neighborhood across the Netherlands

The 2014–2018 period ()) shows a striking pattern of divergent house-value appreciation across neighborhoods. Despite national indications of property value increases, a spatial understanding of these developments reveals instead a story of broad stagnation, or only modest gains, nationally. The glaring exception however is Amsterdam, where dramatic property value gains dominate. To a lesser extent, other cities – particularly Utrecht and Haarlem – display higher gains. The spatial analysis uncovers the stark geographic heterogeneity in housing market developments across neighborhoods, and suggests a growing differentiation in potential asset accumulation among homeowners depending on where households buy property. Multi-scalar and temporal patterns of increasing spatial polarization at the national, regional and municipal level are further untangled in (Hochstenbach & Arundel, Citation2019).

Turning to the composite indicators of inequality in housing values, further confirms our hypothesis of increasing house-value polarization between neighborhoods across the country (): at the neighborhood level, the 90:10 ratio shows that neighborhoods in the 90th percentile had housing values that were 2.23 times higher than those in the 10th percentile in 2006. By 2018, this ratio had gone up to 2.42 – indicating increasing spatial inequality. Annual figures show a clear and consistent trend upwards, and a post-2015 acceleration of inequality. The 75:25 ratio is more stable, showing a slight increase in inequality. At the dwelling level, we see a similar divergent development, indicating growing differences in house values between expensive and affordable units.

Finally, the Gini captures overall inequality in the distribution of average housing values. Increasing Gini-coefficients at the neighborhood-level from 18.66 to 20.55 (an increase of +10%) confirm a clear pattern of spatial house-value polarization. In other words, nationwide, the distribution of housing values across neighborhoods has become more unequal. Between 2015 and 2018, the Gini shows a rapid increase, suggesting accelerating polarization in the most recent years. At the dwelling level, the Gini increased from 26.87 in 2006 to 28.64 in 2018 (+6.6%). As would be expected, inequalities are stronger at the dwelling level than at the aggregated neighborhood level. Interestingly, however, the increase in inequality was stronger at the neighborhood level than at the dwelling level.

Given the time lag and more tempered nature of assessed property values in comparison with actual sale prices, it is expected that the results would show even higher levels of inequality measured by sales prices. Recent data on prices, only available for the largest municipalities, show an even starker intensified dominance of Amsterdam compared to the national average (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019c). This indicates that as the city captures an increasingly disproportionate share of property capital flows, spatial polarization may accelerate.

Divided access to housing submarkets

With the second empirical focus, we are subsequently interested in where young adults entering homeownership buy into the housing market. More specifically, we aim to unravel to what extent economic and parental support characteristics shape access to the spatially-differentiated housing submarkets across a landscape of (increasingly) unequal higher-gain versus lower-gain neighborhoods.

Descriptive findings

Descriptive results across deciles based on neighborhood house-value change () reveal that gross household income is positively associated with the ability to buy in high-gain neighborhoods, supporting our expectations (Hypothesis 2a). Households buying into the top 20% of neighborhoods earn five to eight percent more than the average young-adult household in our population, while those moving into the lowest-gain neighborhoods, earn four percent below average. The relatively muted relationship can partly be explained by the fact only buyers are included who would need a more substantial income to buy at all.

Table 3. Variation from mean for predictor variables across neighborhood deciles (mean = 100)

Turning to the employment status of principal household earner reveals some interesting findings that do not clearly support the expected relationship (Hypothesis 2b). Both positions of permanent and temporary contracts display relatively even distributions. Those on a permanent contract do not buy into high-gain areas more often, neither does there appear to be a substantial penalty for those on a temporary contract. Instead, those on a permanent contract are even slightly underrepresented in high gain areas, while the opposite is true for those on a temporary contract. Surprisingly, young adults buying into the highest-gain areas are relatively often self-employed or students – a point we will elaborate upon in the subsequent section.

On the other hand, parental wealth remarkably shows some even stronger divergences in neighborhood outcomes than household income but particularly for the highest decile. We do see more ambiguous patterns at the lower deciles given with somewhat higher parental wealth values for the lowest deciles and lowest parental wealth associated with the middle deciles. This is explained by the fact that mean 2014 house values in those bottom three deciles are higher than for the middle four deciles (albeit lower than for top three deciles). In other words, even though these neighborhoods show below-average gains, they are slightly more expensive than the average. In the highest-gain neighborhoods, however, the pattern is starkly clear. For young adult households moving into the top decile, their parents hold a full 54% more wealth than average (supporting Hypothesis 3a). Distinguishing between parental housing wealth and other non-housing parental wealth (i.e. savings), we find the latter does show an even stronger correlation with neighborhood outcomes. This lends support to our expectations regarding non-housing wealth as more liquid and easily transferable between generations (Hypothesis 3b).

Finally, looking at education reveals strong differentiations. While overall, our population is a relatively highly educated,Footnote8 there are nonetheless clear divergences in spatial outcomes. Those with low or middle education buy into low-gain areas relatively often, while those with a high education concentrate in high-gain areas.

Regression analyses

We estimated multi-level random effects models with the 2014–2018 neighborhood property value change as the dependent variable to assess the isolated impact of economic position and parental wealth background in access to the spatially-differentiated housing submarkets markets (). We construct a three-step model: adding key parental variables in the second step and, subsequently, an interaction between parental non-housing wealth and employment contract.

Table 4. Multilevel random-effects regression models. Dependent variable: percentage change in house values 2014–2018 of the destination neighborhood

We first see in our models a further confirmation of a significant positive association in our models between gross household income and buying into higher-gain property markets (Hypothesis 2a). This is an important initial indication of an intensification of socio-economic inequality through unequal asset accumulation potential across space. Education measures further corroborate such reproduction of socio-economic divisions with highly educated households being significantly more likely to move into high-gain neighborhoods than their peers with a low or middle education level.

Even after controlling for other factors, employment position measures reveal similarly unexpected results as apparent in the descriptive findings. We find, surprisingly, that young adults on a temporary contract, in self-employment, or in education are more likely to move into high-gain areas than young adults on a permanent contract. One could argue that these groups have a more urban orientation – where the strongest increases in housing values are also recorded. We therefore estimated additional models (available upon request) focusing only on young adults that bought in urban areas (models across the eight largest cities, the four largest cities, Amsterdam and the Amsterdam metropolitan region). Even when narrowing our population, a similar effect for those self-employed and temporarily employed is found. In other words, even within cities, these young-adult households appear to sort into relatively higher gain areas. One explanation would be that these represent “marginal gentrifiers” – with lower economic but higher cultural capital (Rose, Citation1984). They may lack the economic position to buy into established areas, seeking out niche markets of incipient gentrification instead.

Looking at parental background variables, the second model confirms our hypothesis finding a significant independent “effect” of parental housing and non-housing wealth on buying in higher-gain neighborhoods. These results support the potential importance of intergenerational resources in accessing prime housing markets (Hypothesis 2a). While we cannot model direct financial transfers, our models clearly reveal the correlation between higher parental resources and entering submarkets with higher asset accumulation rates. This has fundamental implications in the reproduction and amplification of inequalities across generations. While parental non-housing wealth is also strongly significant, after controlling for other variables through our model, we don’t see the expected stronger effect (Hypothesis 2b) as was apparent in the descriptive results. Given that we are not able to look directly at transfers, we acknowledge that parental wealth may also capture the broader social-class background of young adults, although we do control for other key socio-economic indicators. Nonetheless, the “number of siblings” shows a significant negative effect potentially indicating that having to share parental wealth with more siblings reduces the odds to move into high-gain areas. This reinforces the likelihood of parental resources being important in direct support beyond broader class position and associated preferences. Our third model further reveals interesting results in terms of parental wealth to some extent mediating more precarious employment contracts. Including an interaction effect between parental non-housing wealthFootnote9 and employment position reveals that parental resources have a significantly higher impact on the likelihood of accessing a higher gain neighborhood for those on a temporary contract and particularly for students, compared to the reference category of those in full-time employment. The larger role of parental wealth for these groups may correlate with a stronger likelihood of being in higher-gain neighborhoods through further socio-cultural transmission of expectations and preferences for certain neighborhoods (Friedman et al., Citation2015; Hochstenbach & Boterman, Citation2017). Although we can’t measure this directly, for some students with wealthier parents, this may involve assistance with, or purchase of, housing by their parents for their study periods, which could be expected to be more likely located in higher-gain central urban areas and university cities.

Among further control variables, the models return interesting results for ethnicity. We find that non-western non-natives are significantly more likely to buy in higher-gain neighborhoods compared to their native Dutch counterparts. While this is initially an unexpected result, when we run a further OLS regression model focusing only on the four largest cities or on Amsterdam, we instead find this group to be significantly less likely to buy into high-gain areas. The results would therefore seem to be explained by their urban focus. In other words, non-western non-natives homebuyers tend to buy more often in urban areas and especially within the largest cities where we also find many high-gain neighborhoods. Within these cities, however, they are more likely to buy into neighborhoods showing a relatively weak development in housing values. It is furthermore important to keep in mind that we focus on a specific subset of homebuyers, with non-western non-natives much more likely to depend on rental housing. Hence, urban house-value increases may indeed benefit a small group of ethnic minorities – enabling those that bought to accumulate substantial housing assets – but a larger share among these minority groups may in fact find themselves on the losing end where house-value increases translate into declining rental housing affordability.

Robustness checks

Alongside the robustness checks for the subsample of larger cities and the Amsterdam region discussed above, we carried out a series of additional models over different combinations of time periods for property value change (including the full period 2006–2018, 2010–2018, 2011–2018, and so forth). We also estimated OLS regressions without nesting data in provinces, and using larger borough districts (Dutch: wijken) as spatial units. These robustness checks returned highly similar results across all variables, indicating that our findings are not tied to a specific period or spatial scale.

We also ran the models where we did not use neighborhood-level, but dwelling-level change in house values as the dependent variable. Interestingly, while the direction, size and significance of the effects remained highly similar, the explanatory power (R-squared) of these models was substantially lower. A technical explanation may be that aggregation of dwelling data to the neighborhood level smooths the data, reducing dwelling-level volatility. A more substantive explanation would be that dwelling-level grading is partly dependent on post-purchase renovations and investments. Furthermore, purchase decisions may be influenced to a greater extent by neighborhood trajectories. While not the focus of the current article, these potential explanations motivate further research. The results of the individual level models are included as additional material (see Table Appendix) and provide some further insight into population sorting at the level of dwelling outcomes. However, in excluding neighborhood dynamics, these models are essentially non-spatial and thus do not directly capture our primary focus on spatial sorting.

Conclusion

Through an examination of detailed longitudinal register data for the Netherlands, our analyses reveal patterns of increasing spatial polarization in house values confirming our first hypothesis – with growing divergence between “hot” versus “cold” property markets. We further see an acceleration in such spatial polarization for the most recent years. In other words, where one buys has gained importance in securing future housing wealth accumulation. Investigating the flow of young adults into the housing market, we further uncover sharply divided access to neighborhood property markets. The results revealed significant sorting of homebuyers into higher or lower gain neighborhoods across socio-economic lines in terms of income and education levels. The findings confirm our second hypotheses with income as a predictor of buying into higher-gain neighborhoods (Hypothesis 2a). On the other hand, some unexpected associations regarding employment position were found (Hypothesis 2b), with self and temporary employed young home-buyers instead correlating with higher-gain neighborhoods. Part of the explanation seems to be the somewhat larger role that parental wealth plays for this subgroup, as the interaction-effect model suggests.

In all our analyses, we further reveal parental wealth as a crucial determinant of access to high-gain areas (Hypothesis 3a). In overall population sorting into deciles we also see a stronger effect of parental non-housing wealth (Hypothesis 3b). This, along with the interaction results and the moderating effect of siblings, underscores the mechanism of direct financial parental support in accessing more lucrative submarkets.

On the basis of these empirical findings we can make various broader, analytical contributions. Our paper demonstrates the importance of considering multiple dimensions of socio-economic status in assessing divided housing access. Income and employment position remain crucial, but socio-economic inequalities also depend on multiple interacting factors. Increasing labor market precarity makes it more important to differentiate between temporary and permanent contracts. Deepening generational divides amplify the importance of parental support. The role of parental resources in accessing higher rates of housing wealth accumulation implies a crucial mechanism of the intergenerational reproduction of inequalities. While we looked specifically at new buyers, such divisions among homeowners only supplement further inequalities between homeowners and renters entirely excluded from property wealth accumulation (see Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2018). These dynamics are often reinforced over time, as homeowners who accumulate substantial assets are again more able to move into high-gain areas. Our findings thus point to multiple intersecting socio-economic cleavages in housing asset accumulation trajectories.

Our spatial analyses further highlight clear and consistent increases in spatial inequality in house values, with capital gains increasingly concentrating in (certain) major cities. Where one buys has become more important in achieving future housing-wealth accumulation. Increasing spatial disparities are thus set to become more important in producing and reproducing social inequalities.

These findings imply significant policy relevance. The active role of space in amplifying unequal asset accumulation demands a careful consideration of policies that may mitigating spatial divides. These relate to macro-level policies in dampening housing financialization and marketization, such as mortgage regulation and reducing homeowner tax benefits, as well as policies that may promote a de-commodification of housing (i.e. regulations against speculative property investment and increasing non-market housing options). This could further involve spatially-targeted measures, particularly in overheated markets, as well as a broader reconsideration of state policies that promote uneven development.

Above all, the research exposes underlying mechanisms driving growing housing wealth inequalities. Our research promotes a crucial spatial understanding of wealth accumulation – one that may also be relevant to interpret other societal inequalities. It is not just a question of owner-occupiers versus renters, as our analyses indicate notable segmentation between buyers. Buying in the right place may enable some low-status households to make windfall gains, but polarization suggests benefits mostly concentrated among already-privileged households, and increasingly so. Wealth inequalities are not only mapped onto space, but space itself figures prominently in reproducing and amplifying such inequalities. In other words, where you buy matters: shaping both individual life-courses as well as societal inequalities. This only becomes more critical as spatial polarization intensifies.

Data Availability Statement

This paper draws on author calculations of non-public micro-data from the Systems of Social-statistical Datasets (SSD) from Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors on request. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/onze-diensten/methoden/onderzoeksomschrijvingen/korte-onderzoeksbeschrijvingen/stelsel-van-sociaal-statistische-bestanden--ssb--

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. While our discussion of housing and housing markets throughout refers to the entirety of both building and land value, for an interesting overview of the particular role of land markets see the work by Murphy (Citation2018) on the UK.

2. Defined as having a head of household aged between 16 and 39 years old.

3. For example, land-registry data is missing for the municipality of Steenbergen (10,006 dwellings distributed over 18 neighborhoods in 2016) and most of Bernheze. Due to the small size of both municipalities, their omission does not influence our findings.

4. Unfortunately, the structure of our dataset does not allow us to also include the employment situation of all partners, although we do capture income at the combined household level alongside household type.

5. Very minor discrepancies between tax and insurance datasets exist, albeit unlikely to skew results.

6. In the regression analyses we control for the total number of siblings as this may influence how much financial support one child may receive.

7. Haarlem is unlabeled on the map, but identifiable as the green cluster west of Amsterdam.

8. This is partly because we focus on young adults and homebuyers – both groups with higher education levels than the total population.

9. We focus on the non-housing wealth as being the most “liquid” and potentially readily accessible to support adult children’s housing trajectories.

References

- Aalbers, Manuel. (2007). Geographies of housing finance: The mortgage market in Milan, Italy. Growth and Change, 38(2), 174–199.

- Aalbers, Manuel. (2008). The financialisation of home and the mortgage market crisis. Competition & Change, 12(2), 148–166.

- Aalbers, Manuel. (2016). The financialisation of housing: A political economy approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Aalbers, Manuel, Bosma, Jelke, Fernandez, Rodrigo, & Hochstenbach, Cody. (2018). Buy-to-let: gewikt en gewogen. Leuven/Amsterdam: KU Leuven/University of Amsterdam.

- Aalbers, Manuel, & Christophers, Brett. (2014). Centring housing in political economy. Housing, Theory and Society, 31(4), 373–394.

- Albertini, Marco, & Kohli, Martin. (2012). The generational contract in the family: An analysis of transfer regimes in Europe. European Sociological Review, 29(4), 828–840.

- Allegré, Guillaume, & Timbeau, Xavier. (2015). Does housing wealth contribute to wealth inequality? A tale of two New Yorks. Paris: Sciences Po.

- Ansell, Ben. (2014). The political economy of ownership: Housing markets and the welfare state. American Political Science Review, 108(2), 383–402.

- Appleyard, Lindsey, & Rowlingson, Karen. (2010). Home-ownership and the distribution of personal wealth. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Arundel, Rowan. (2017). Equity inequity: Housing wealth inequality, inter and intra-generational divergences, and the rise of private landlordism. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(2), 176–200.

- Arundel, Rowan, & Doling, John. (2017). The end of mass homeownership? Changes in labour markets and housing tenure opportunities across Europe. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(4), 649–672.

- Arundel, Rowan, & Ronald, Richard (2019). The false promise of homeownership. (HOUWEL Working Paper Series). University of Amsterdam.

- Bell, David, & Blanchflower, David. (2011). Young people and the great recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(2), 241–267.

- Biegert, Thomas. (2014). On the outside looking in? Transitions out of non-employment in the United Kingdom and Germany. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(1), 3–18.

- Bischoff, Kendra, & Reardon, Sean. (2014). Residential segregation by income, 1970–2009. In Logan John (Ed.), Diversity and disparities: America enters a new century (pp. 208–233). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Boterman, Willem (2012). Residential practices of middle classes in the field of parenthood (PhD thesis). University of Amsterdam.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. (2005). The social structures of the economy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brenner, Neil. (2004). New state spaces: Urban restructuring and state rescaling in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, Neil, Peck, Jamie, & Theodore, Nik. (2010). Variegated neoliberalization: Geographies, modalities, pathways. Global Networks, 10(2), 182–222.

- Christophers, Brett. (2011). Revisiting the Urbanization of Capital. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(6), 1347–1364.

- Christophers, Brett. (2018). Intergenerational inequality? Labour, capital, and housing through the ages. Antipode, 50(1), 101–121.

- Clark, William, & Dieleman, Frans. (1996). Households and housing: choice and out- comes in the housing market. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University.

- Cooke, Thomas, & Denton, Curtis. (2015). The suburbanization of poverty? An alternative perspective. Urban Geography, 36(2), 300–313.

- Coulter, Rory. (2017). Local house prices, parental background and young adults’ homeownership in England and Wales. Urban Studies, 54(14), 3360–3379.

- Desmond, Matthew. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American City. New York, NY: Broadway.

- Dewilde, Caroline, Hubers, Christa, & Coulter, Rory. (2018). Determinants of young people’s homeownership transitions before and after the financial crisis: The UK in a European context. In Beverley Searle (Ed.), Generational interdependencies: The social implications for welfare (pp. 51–73). Delaware: Vernon Press.

- Doling, John, & Ronald, Richard. (2010). Home ownership and asset-based welfare. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(2), 165–173.

- Dotti Sani, Giulia, & Acciai, Claudia. (2018). Two hearts and a loan? Mortgages, employment insecurity and earnings among young couples in six European countries. Urban Studies, 55(11), 2451–2469.

- Druta, Oana, & Ronald, Richard. (2017). Young adults’ pathways into homeownership and the negotiation of intra-family support: A home, the ideal gift. Sociology, 51(4), 783–799.

- EMF [European Mortgage Federation]. (2018). HYPOSTAT 2016: A review of Europe’s mortgage and housing markets. Brussels: EMF.

- Emmeneger, Patrick. (2012). The age of dualization: The changing face of inequality in deindustrializing societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Etherington, David, & Jones, Martin. (2009). City-regions: New geographies of uneven development and inequality. Regional Studies, 43(2), 247–265.

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, & Aalbers, Manuel. (2016). Financialization and housing: Between globalization and varieties of capitalism. Competition & Change, 20(2), 2.

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, Hofman, Annelore, & Aalbers, Manuel. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and Planning A, 48(12), 2443–2461.

- Filandri, Marianna, & Bertolini, Sonia. (2016). Young people and home ownership in Europe. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(2), 144–164.

- Forrest, Ray, & Hirayama, Yosuke. (2015). The financialisation of the social project: Embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and home ownership. Urban Studies, 52(2), 233–244.

- Forrest, Ray, & Hirayama, Yosuke. (2018). Late home ownership and social re-stratification. Economy and Society, 47(2), 257–279.

- Forrest, Ray, & Murie, Alan. (1989). Differential accumulation: Wealth, inheritance and housing policy reconsidered. Policy & Politics, 17(1), 25–40.

- Friedman, Sam, Laurison, Daniel, & Miles, Andrew. (2015). Breaking the ‘class’ ceiling? Social mobility into Britain’s elite occupations. The Sociological Review, 63(2), 259–289.

- Gastner, Michael, & Newman, Mark. (2004). Diffusion-based method for producing density-equalizing maps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(20), 7499–7504.

- Green, David, & Bentley, Daniel. (2014). Finding shelter: Overseas investment in the UK housing market. London: Civitas.

- Hamnett, Chris. (1992). The geography of housing wealth and inheritance in Britain. Geographical Journal, 158(3), 307–321.

- Hamnett, Chris. (1999). Winners and losers: Home ownership in modern Britain. London: UCL.

- Harvey, David. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism. Geografiska Annaler B, 71(1), 3–18.

- Häusermann, Silja, & Schwander, Hanna. (2012). Varieties of dualization? Labor market segmentation and insider outsider divides across regimes. In Patrick Emmeneger, Silja Häusermann, Bruno Palier, & Martin Seeleib-Kaiser (Eds.), The age of dualization: The changing face of inequality in deindustrializing societies (pp. 27–51). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hay, Colin. (2004). Common trajectories, variable paces, divergent outcomes? Models of European capitalism under conditions of complex economic interdependence. Review of International Political Economy, 11(2), 231–262.

- Helderman, Amanda, & Mulder, Clara. (2007). Intergenerational transmission of homeownership: The roles of gifts and continuities in housing market characteristics. Urban Studies, 44(2), 231–247.

- Hills, John, Cunliffe, Jack, Gambaro, Ludovica, & Obolenskaya, Polina. (2013). Winners and losers in the crisis: The changing anatomy of economic inequality in the UK 2007–2010 (social policy in a cold climate, research report 2). London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, LSE.

- Hochstenbach, Cody. (2017). State‐led gentrification and the changing geography of market‐oriented housing policies. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(4), 399–419.

- Hochstenbach, Cody. (2018). Spatializing the intergenerational transmission of inequalities: Parental wealth, residential segregation, and urban inequality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(3), 689–708.

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Arundel, Rowan. (2019). Spatial housing market polarisation: national and urban dynamics of diverging house values. Transactions Of The Institute Of British Geographers. doi: 10.1111/tran.12346

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Boterman, Willem. (2017). Intergenerational support shaping residential trajectories: Young people leaving home in a gentrifying city. Urban Studies, 54(2), 399–420.

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Musterd, Sako. (2018). Gentrification and the suburbanization of poverty: Changing urban geographies through boom and bust periods. Urban Geography, 39(1), 26–53.

- Kalleberg, Arne. (2018). Job insecurity and well-being in rich democracies. The Economic and Social Review, 49(3), 241–258.

- Kohl, Sebastian. (2018). The political economy of homeownership: A comparative analysis of homeownership ideology through party manifestos. Socio-Economic Review, 0–28.

- Kurz, Karin, & Blossfeld, Hans-Peter (Eds.). (2004). Home ownership and social inequality in a comparative perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Lennartz, Christian, Arundel, Rowan, & Ronald, Richard. (2016). Younger adults and homeownership in europe through the global financial crisis. Population, Space and Place, 22(8), 823–835.

- Lersch, Phillip, & Dewilde, Caroline. (2015). Employment insecurity and first-time homeownership: evidence from twenty-two european countries. Environment and Planning a, 47(3), 607-624.

- Ley, David. (1996). The new middle class and the remaking of the central city. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lijzenga, Jeroen., & Boertien, Diana. (2016). De rol van woningcorporaties op de woningmarkt: Een WoOn 2015-verkenning. Arnhem: Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

- Martinez‐Fernandez, Cristina, Audirac, Ivonne, Fol, Sylvie, & Cunningham‐Sabot, Emmanuele. (2012). Shrinking cities: Urban challenges of globalization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(2), 213–225.

- McKee, Kim. (2012). Young people, homeownership and future welfare. Housing Studies, 27(6), 853–862.

- Milanovic, Branko. (2016). Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Mulder, Clara, & Hooimeijer, Pieter. (1999). Residential relocations in the life course. In Leo van Wissen & Pearl Dykstra (Eds.), Population Issues (pp. 159–186). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Murie, Alan, & Forrest, Ray. (1980). Wealth, inheritance and housing policy. Policy & Politics, 8(1), 1-19.

- Murphy, Luke. (2018). The Invisible Land: The hidden force driving the UK’s unequal economy and broken housing market. In (IPPR discussion paper). London: IPPR Commission on Economic Justice.

- Musterd, Sako. (2014). Public housing for whom? Experiences in an era of mature neo-liberalism: The Netherlands and Amsterdam. Housing Studies, 29(4), 467–484.

- Musterd, Sako, & Andersson, Roger. (2005). Housing mix, social mix, and social opportunities. Urban Affairs Review, 40(6), 761–790.

- Musterd, Sako, Marcińczak, Szymon, Van Ham, Maarten, & Tammaru, Tiit. (2017). Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geography, 38(7), 1062–1083.

- Nolan, Brian, Salverda, Wiemer, Checchi, Daniele, Marx, Ive, McKnight, Abigail, Tóth, István György, & Van de Werfhorst, H. (2014). Changing inequalities and societal impacts in rich countries: Thirty countries’ experiences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], (2016). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising (OECD Publications). Retrieved from doi:10.1787/9789264119536-en

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. (2019a). Housing prices (indicator). doi:10.1787/63008438-en.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. (2019b). Under pressure: The squeezed middle class. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/689afed1-en

- Öst, Cecilia Enström. (2012). Parental wealth and first-time homeownership: A cohort study of family background and young adults’ housing situation in Sweden. Urban Studies, 49(10), 2137–2152.

- Reuten, Geert. (2018). De Nederlandse vermogensverdeling in internationaal perspectief. Een vergelijking met 26 andere OECD-landen. TPEdigitaal, 12(2), 1–8.

- Rijskoverheid (2018). Hoe bepalen gemeenten de WOZ-waarde?. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/waardering-onroerende-zaken-woz/vraag-en-antwoord/woz-waarde-bepalen

- Ronald, Richard. (2008). The ideology of homeownership: Homeowner societies and the role of housing. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rose, Damaris. (1984). Rethinking gentrification: Beyond the uneven development of Marxist urban theory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2(1), 47–74.

- Rowlands, Rob, & Gurney, Craig. (2000). Young peoples? Perceptions of housing tenure: A case study in the socialization of tenure prejudice. Housing, Theory and Society, 17(3), 121–130.

- Sampson, Robert. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sampson, Robert, & Sharkey, Patrick. (2008). Neighborhood selection and the social reproduction of concentrated racial inequality. Demography, 45(1), 1–29.

- Sassen, Saskia. (1991). The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sassen, Saskia. (2014). Expulsions. Brutality and complexity in the global economy. Cambridge/London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Schwartz, Herman, & Seabrooke, Len. (2008). Varieties of residential capitalism in the international political economy: Old welfare states and the new politics of housing - Springer. Comparative European Politics, 6(3), 237–261.

- Smith, Neil. (1979). Toward a theory of gentrification a back to the city movement by capital, not people. Journal of the American Planning Association, 45(4), 538–548.

- Spilerman, Seymour, & Wolff, Francois-Charles. (2012). Parental wealth and resource transfers: How they matter in France for home ownership and living standards. Social Science Research, 41(2), 207–223.

- Statistics Netherlands. (2019a). Voorraad woningen; eigendom, type verhuurder, bewoning, regio. Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82900NED/table?dl=1EBE2

- Statistics Netherlands. (2019b). Woningvoorraad naar eigendom; regio, 2006–2012. Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/71446ned/table?dl=21BAC

- Statistics Netherlands (2019c). Bestaande koopwoningen; verkoopprijzen; regio; prijsindex 2015=100. Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83913NED/table?dl=2325B

- Stiglitz, Joseph. (2012). The Price of Inequality. London: Penguin.

- Stockhammer, Engelbert. (2013). Why have wage shares fallen? An analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution. In Wage-led growth (pp. 40–70). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Terhorst, Pieter, & Van de Ven, Jacques. (1995). The national urban growth coalition in The Netherlands. Political Geography, 14(4), 343–361.

- Van Bavel, Bas, & Salverda, Wiemer. (2014). Vermogensongelijkheid in Nederland. Economisch Statistische Berichten, 99(4688), 392–395.

- Van Gent, Wouter. (2013). Neoliberalization, housing institutions and variegated gentrification: how the ‘third wave’ broke in amsterdam. International Journal Of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 503-522.

- Van Ham, Maarten, Hedman, Lina, Manley, David, Coulter, Rory, & Östh, John. (2014). Intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood poverty: An analysis of neighbourhood histories of individuals. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(3), 402–417.

- Wind, Barend, & Hedman, Lina. (2018). The uneven distribution of capital gains in times of socio-spatial inequality: Evidence from Swedish housing pathways between 1995 and 2010. Urban Studies, 55(12), 2721–2742.

- Wind, Barend, Lersch, Phillip., & Dewilde, Caroline. (2017). The distribution of housing wealth in 16 European countries: Accounting for institutional differences. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(4), 625–647.

- Wyly, Elvin, & Hammel, Daniel. (1999). Islands of decay in seas of renewal: Housing policy and the resurgence of gentrification. Housing Policy Debate, 10(4), 711–771.

Appendix.

Multilevel random-effects regression models. Dependent variable: percentage change in house values 2014–2018 of the destination dwelling