ABSTRACT

The emerging literature on the globalization of real estate has addressed how internationally circulating capital has increasingly found its ways into housing markets of the “Global South”. With relatively underdeveloped financial and real estate markets, these countries have discursively and materially been rebranded as emerging markets, that is, they have been shaped into frontiers in the global urbanization of capital. In this paper we scrutinize the transnational real estate networks that shape and reshape the Cuban housing market. First, we reconstruct how, following the 2011 legalization of housing prices set between buyers and sellers, Cuban migrants and a few foreign investors, in cooperation with Cubans residing in Cuba, are buying properties in Cuba’s cities, beach resorts and other towns. Second, we explore the economic and extra-economic motives behind such transnational property transactions, highlighting how residential properties are bought and converted into private restaurants or hotels. Central to our analysis is that the present development is not simply shaped by local or national demand and processes but also by international investment. We contend that a pattern of economic globalization unfolds where transnational remittances, rather than institutional investments or mortgage finance, steer Cuba’s emerging property market, along with local investments among Cuban citizens.

1. Introduction

Recent studies on the globalization of real estate demonstrate how select cities in the Global North, including London, New York, Sydney and Vancouver, have become “safe deposit boxes” for globally circulating capital of large investment funds and transnational wealth elites (Fernandez et al., Citation2016; Ley, Citation2017; Rogers et al., Citation2015; Sassen, Citation2014). Other studies suggest that the relatively undeveloped credit and real estate markets of the Global South provide big investment opportunities for those seeking to profit from surging real estate prices (Rolnik, Citation2013; Wyly, Citation2015). From the rise of internationally funded secondary mortgage markets in Mexico and Brazil (Pereira, Citation2017; Soederberg, Citation2015), over to the subprime urbanization of Tangier and Beirut (Krijnen, Citation2018; Kutz & Lenhardt, Citation2016), to economic migration and transnational gentrification in Panama City, Cuenca, and other Latin American cities (Hayes, Citation2015; Janoschka et al., Citation2014; Sigler & Wachsmuth, Citation2016), scholars argue that cities of the Global South are not insulated from transnational developments. Indeed, the materialization of new urban frontiers is driven by the rolling out of real estate finance techniques “invented” in the US, such as mortgage securitization and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), to the Global South (Bassens, Citation2012; Pereira, Citation2017; Sanfelici & Halbert, Citation2018; Soederberg, Citation2015). This is increasingly realized through the creation of alternative financial infrastructures through which capital can flow into real estate and land markets (AlShehabi & Suroor, Citation2016; Buckley & Hanieh, Citation2014; Mosciaro et al., Citation2021; Shatkin, Citation2017; Zhang, Citation2018).

The globalization of real estate is not a “neutral” process because the connections between North and South are shaped and reshaped by inherited patterns of uneven development (Pollard, Citation2012; Wissoker et al., Citation2014). On the one hand, the emerging “global” or “glocal” management, production, and consumption of real estate is associated with capital switching dynamics between Global North and South (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2019; Murphy, Citation2008). On the other, the globalization of urban real estate in the Global South is perceived as a local strategy of city governments to attract private capital from the Global North as a means to boost local housing developments (Murphy, Citation2008; Searle, Citation2014; Shatkin, Citation2017). Kutz and Lenhardt (Citation2016), for example, write about city officials in the Moroccan city of Tangiers that deliberately introduced urban policies to open up their urban housing market to flows of European investment capital.

However persistent such hierarchical patterns may be (Rolnik, Citation2013; see also Gotham, Citation2016), increasing evidence suggests that the globalization of real estate entails more than a mere rolling out of financial (and institutional) capital into housing economies of the South (Pollard, Citation2012). For example, Krijnen et al. (Citation2017, p. 2890) argue that academic research should move beyond the “appraisal of ‘traditional’ vectors of globalization”, and instead focus on the role of other financial intermediaries, including expatriate and migrant communities. Other studies have demonstrated that a growing number of retirees and middle-class investors from the North are buying up (residential) properties in the South (Hayes, Citation2015; Kutz & Lenhardt, Citation2016; Sigler & Wachsmuth, Citation2016). In other words, the globalization of real estate is not solely triggered by formal (and institutional) procedures and practices of “market making”; informal (and sometimes semi-legal) housing dynamics are equally important for understanding transnational ownership patterns in urban housing markets.

In developing this alternative framework, we first explore how patterns of “expatriate world-city formation” (Beaverstock, Citation2010; Cook, Citation2010) can trigger globalizing tendencies in the urban real estate markets of Southern economies. Krijnen (Citation2018), for example, highlights state practices in Lebanon that enabled real estate actors to attract capital not only from neighboring countries but also from the Lebanese diaspora as a source of wealth to be absorbed into Beirut’s housing market. Indeed, an increasing number of migrants consider urban land and housing as an attractive investment opportunity – especially now that global property prices are surging (De Haas, Citation2006; Obeng-Odoom, Citation2010). Thus, we argue that foreign investments in the Global South are not exclusively coming from the super-rich and institutional investors from the Global North. Rather, transnational middle-class investors living in the Global North, but having personal ties with the Global South, play an under-estimated and under-studied role in fueling local housing booms.

Second, we emphasize that due to domestic barriers like the nonexistence of a mortgage market, securitization or REITs, the export of the “financialized” housing model to the Global South remains a challenge for investors and financial institutions from abroad (cf. Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2019; Pereira, Citation2017). Yet, foreign capital can still find its way into urban real estate of Southern economies, albeit not always involving the “traditional” actors or market segments (Krijnen, Citation2018). For example, Sigler and Wachsmuth (Citation2016) show how “cosmopolitan transnational residents” have increasingly bought homes in Panama City that are considered architecturally interesting, thereby tying international capital flows to redevelopment and gentrification. Likewise, Hayes (Citation2015) discusses the acquisition of many residential homes in the Ecuadorian city Cuenca by U.S. citizens who intend to retire there or spend holidays. In other words, evidence from the Global South shows that transnational sub-markets for leisure, (medical) tourism, and (professional) retirement are rapidly emerging, involving especially middle-class investors and not always large banks or institutional consortia (Bianchi, Citation2009; Yrigoy, Citation2016).

We contribute to debates on real estate globalization and housing financialization by exploring the case of Cuba where recent housing reforms have legalized housing prices set between buyers and sellers (Peters, Citation2014b). Our central finding is that in the absence of mortgage markets a significant amount of housing transactions is funded by Cuban migrants and a few foreign investors which provide the monetary resources to locals for buying residential properties. This triggers a pattern of economic globalization where transnational remittances, rather than institutional investments or mortgage finance, steer Cuba’s emerging property market. We also show how this geographically uneven trend gives rise to emerging sub-markets as a significant number of properties are converted into private restaurants or hotels funded or run by transnational networks of Cuban migrants and local middlemen (testaferros). Although such middlemen play a pivotal role in mediating money flows, they are not registered actors, contrary to e.g. real estate developers who mediate the urbanization of capital in southern India (Rouanet & Halbert, Citation2016).

Current trends in the Cuban housing economy offer a unique opportunity to study actually existing “market making” processes and practices in a socialist context where private homeownership was historically predominant, but with restrictions for buying, selling, and investing (Grein, Citation2015). Our findings therefore also dialogue with the literatures on “market making” and “marketization” in general (Boeckler & Berndt, Citation2012; Corpataux & Crevoisier, Citation2016; French et al., Citation2011; Hall, Citation2010), on real estate in particular (Hofman & Aalbers, Citation2019; Searle, Citation2014; Waldron, Citation2018; Wijburg & Aalbers, Citation2017), and on situations of emerging market socialism or (post-)socialism more specifically (Bitterer & Heeg, Citation2012; Bohle, Citation2014; Büdenbender & Aalbers, Citation2019; Büdenbender & Golubchikov, Citation2017). Our findings also sharpen existing debates on financial globalization, uneven development, and dependency theory in an increasingly connected “world of cities” (Brenner & Schmid, Citation2014; Robinson, Citation2016). As transnational capital flows into “tourism property”, remittances can increasingly take a two-way direction because they are also returned in the monetary form of shared profits (García Pleyán, Citation2018).

In this introduction we have emphasized the importance of: (1) private and middle-class investors and exile or expatriate and migrant communities; (2) emerging sub-markets for private investment, such as luxury homes and tourist-led housing; and (3) informal remittance economies which steer transnational investments in the Global South. In this paper, we analyze Cuba’s housing trajectory from a socio-geographical and political-economic perspective. We focus on the recent shift in Cuba’s economy toward diversified international trade, transnational remittances, and the inflow of U.S. Dollars. Subsequently, we show how this broader dynamic profoundly changes the form of private homeownership under Cuban socialism. In the empirical sections we scrutinize the current investment patterns in Cuban cities and their transnational ownership structures. We focus on Cuban migrants that moved to the U.S. in the 1990s and 2000s, but also on foreign investors. In the conclusion, we reflect on the general prospects regarding Cuba’s housing future, stipulating the incomplete and contested nature of institutional change in Cuba more generally.

The absence of comparable real estate data, the political sensitivity of the topic in Cuba, and the uncertainties with regards to the future housing policies of the new government of Díaz-Canel and to the U.S.-Cuba relations under the Trump administration, make it difficult to sketch a definitive picture of Cuba’s ongoing but premature housing transformations. Recognizing the methodological challenges for doing research in Cuba (Bell, Citation2013; Bono, Citation2019), we proceeded as follows. First, we based our study on the consultation of various policy documents, newspaper articles, and important policy reports from Cuban research institutes in and outside Cuba. Second, our study is informed by semi-structured interviews with Cuban migrants residing in the U.S. and with Cubans residing in Havana (2018–2019). We particularly scrutinize the transnational dynamics in the “hot” market of Havana and much less in other areas.

2. Cuba’s transforming (International) political economy

It is well understood that Cuba has undergone dramatic changes since the collapse of European communism (LeoGrande, Citation2015). The path to post-socialism by Eastern Europe and Russia left many commentators speculating on Cuba’s future as an emerging market socialist or post-socialist economy (e.g. LeoGrande, Citation2015). Whether Cuba’s political economy may eventually morph into market socialism or liberal capitalism has become a recurring topic.Footnote1 However, the direction of institutional change in the Cuban context has always been difficult to assess considering that an ideal-typical “model” of socialism was never fully implemented nor fully abandoned by the Cuban government (Backer, Citation2014; Font & Janscis, Citation2015). Like many other planned economies, Cuba shows a Polanyian “pendulum movement” between periods where ideology and moral incentives prevail to ensure acceptance of the socialist goals by the population and periods where pragmatism and material incentives become more important to solve the tensions between socialist promises and slow economic growth (Bono, Citation2018; Gu et al., Citation2015). The changes that Cuba has undergone could therefore be seen as part of a constantly changing economic system, rather than a radical break with the past.

Cuba’s export-oriented economy long depended on one commodity – sugar – and one trading partner – first Spain, then the U.S., and finally the Soviet Union. The shocking, almost overnight, disappearance of the latter dramatically reduced Cuba’s capacities to import which led to a severe economic crisis, called the “Special Period” (1991–2000) (LeoGrande & Thomas, Citation2002). Suddenly, Cuba had to abandon its model of import-substitution where the Soviet Union was the main trading partner and insert itself into the international capitalist economy. To do so, Cuban leaders had to rapidly find new ways to earn hard currency. The main strategies that the government adopted were: attracting foreign investment capital, legalizing the U.S. Dollar market (which already existed for diplomats), opening dollar stores for the general public, and building up the tourist industry (Brenner et al., Citation2014). On the one hand, there were firms that were financed with foreign currency and aimed to be competitive. On the other hand, there was the traditional sector that remained regulated by the allocation of resources and shaped to maintain the coherence of the socialist project (Villalón-Madrazo, Citation2011).

This dual economy generated a permanent tension that affected efficiency, salaries, and prices (Egozcue & Mario, Citation2014). This was reinforced by remittances from abroad that rose to over 1 USD billion annually while the purchasing power of the Cuban peso receded (Brenner et al., Citation2014). The increase of remittances also contributed to the legalization of the U.S. Dollar, which had three main goals: discouraging the illegal black market, capturing dollars that could be used to import necessities, and further encouraging Cubans who live abroad to send more money to their families (ibid.). Along with the 1994 introduction of the convertible peso (CUC) pegged at a 1:1 rate to the U.S. dollar and used by tourists and Cubans with access to CUC in retail outlets (Morales, Citation2018), the transnational flow of money to Cuba increased rapidly (Pérez, Citation2006).

At the same time, markets were segmented into different circuits using different currencies (Egozcue & Mario, Citation2014). Joint ventures were established to boost Cuban tourism and businesses, sometimes also to provide residential and retail services to foreign diplomats and companies (Jayawardena, Citation2003). The tourism industry, along with Cuban services abroad, replaced the sugar industry as Cuba’s primary source of hard currency and became a critical element of Cuba’s economic recovery (Brenner et al., Citation2014; Egozcue & Mario, Citation2014; Jiménez, Citation2014). Yet, it highlighted and aggravated social inequality between Cubans who had access to dollars and those who did not (Brenner et al., Citation2014; LeoGrande & Thomas, Citation2002). A class of “new rich” entrepreneurs emerged (Henken & Vignoli, Citation2015) and the expansion of the tourism sector was accompanied by the increase in illegal activities such as prostitution and gambling.

The 1993 Decree-Law 141 on self-employment replaced Decree-Law 14 (1978), marking the emergence of what is widely considered as the small private business of contemporary Cuba (Antúnez Sánchez et al., Citation2013; Brenner et al., Citation2014; Egozcue & Mario, Citation2014; Radfar, Citation2016; Rojas, Citation2014). The new decree legalized 55 types of self-employment, which were often remittance- or tourist-funded. This was expanded to 117 types just two years later and by 2002 there were 157 types registered (Antúnez Sánchez et al., Citation2013).

Further economic transitions happened during the 2000s and 2010s. “Market making” and “marketization” became key components of Cuba’s overall economic model. In 2006, when Fidel Castro fell ill, his brother Raúl took over the command and stressed the need for both conceptual and structural changes to Cuban society (Piñeiro Harnecker, Citation2014). In the following years, he introduced a series of reforms to “update” Cuba’s economic model. Ultimately, the 2011 Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba approved the Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social (Guidelines of Economic and Social Policy, Lineamientos in short) aimed at increasing economic performance and international competitiveness (Piñeiro Harnecker, Citation2014). Additionally, Law no. 118 revised the 1995 law on foreign investment to further incentivize foreign investment and ensure it contributes to the country’s sustainable economic development as defined in the Lineamientos (Ley no. 118; see also MINCEX, Citation2017).Footnote2

Other key features of the Lineamientos are administrative decentralization – increasing the role of local governments in local economic activities – and reducing the presence of state companies in economic life, giving more room for other types of economic entities like cooperative associations and self-employed workers. During the Special Period and following the aforementioned Decree-Law 141, a new type of private businesses had already emerged that was permitted but not desired or promoted. From the Lineamientos, this cuentapropismo (self-employment) was treated as a “permanent and dynamic part of the economy, not as a barely tolerated appendage” (LeoGrande, Citation2014, p. 67). Thus, the reforms present an important departure from the assumption of a mutually exclusive dichotomy between state and market (Egozcue & Mario, Citation2014). While private entrepreneurship was previously treated as a “necessary evil”, it is now perceived as a “strategic necessity” for the government to cut costs, but also to contribute to Cuba’s economic development (Peters, Citation2014a).

Although private entrepreneurship in the Cuban non-state sector is predominantly self-funded (Vidal & Viswanath, Citation2019), entrepreneurial activities in Cuba’s tourism sector are strongly backed by remittances from Cuban migrants or tourist tips (Henken & Vignoli, Citation2015; Duany, Citation2016, p. 87). In the past decade, Cuba’s remittance economy has become more business-oriented. Increasingly, money coming into Cuba is used for funding or starting (tourism-related) private enterprises such as restaurants or hotels (Morales, Citation2018). Because the profits of these enterprises partly flow out of Cuba, this recent development exemplifies a change in the supposed one-way direction of (more traditional) remittances; both donor and receiver benefit from shared profits (Sergio & Perez-Lopez, Citation2003; see also Anderson & Serpa, Citation2018).

In sum, Cuba has not become the playground of some sort of borderless global capital. Cuban authorities have encouraged select marketization – that is, select market mechanisms in select sectors – by ensuring that the domestic economy was not fully opened to the external pressures of the global market economy (Scarpaci et al., Citation2002). Nevertheless, the increased importance of the remittance economy, along with the massive inflow of hard currency encouraged by international tourism, shows that transnational economic activities began to shape and reshape the Cuban dual economy in profound and often unforeseen ways (Gonzalez-Corzo & Justo, Citation2017). We maintain that (post-)Special Period reforms did not undermine Cuban socialism but rather entailed a transition to more reliance on market mechanisms and private self-employment. We elaborate on this in the next section where we analyze the changing role of private homeownership in Cuba’s transnationalizing housing sector.

3. The changing role of private homeownership in socialist Cuba

The previous section discussed the selective (but rapid) opening of Cuba’s transforming political economy to the flows of international capital, not only by diversifying foreign trade. Transnational remittances from Cuban migrants and foreign direct investments in joint ventures and other Cuban (often tourist-related) enterprises have become more important for Cuba’s economy. How, then, is the intensification of the dual economy in Cuba linked to transformations in the Cuban housing sector? And in what ways did the Cuban housing market open to flows of international remittances and transnational investments?

Although social renting was the dominant housing model in most European socialist regimes, private homeownership became an important pillar of Cuba’s socialist housing economy (Hamberg, Citation1986; Grein, Citation2015). In 1960, the new Revolutionary government introduced the Urban Reform Law, which abolished the private rental sector that had existed under Fulgencio Batista (1952–59), and before. Landlords were forced to give up their properties but gained financial compensation provided in installments over time. Most sitting tenants became homeowners, gaining a bundle of rights, including exchanging, leasing, giving away or bequeathing their properties, but not selling them at market-set prices. A fee was paid to the government to compensate for the amortization of a dwelling’s purchase (Peters, Citation2014b). The slogan for Cuban housing policy became “a house to live in and not to live from” (Ibid); “personal property” was identified as part of the socialist project.

Residents in newly state-built dwellings would still be considered long-term leaseholders (usufructarios) and paid ten percent of household income as rent (Hamberg, Citation2012, p. 71). No such regulations were introduced for self-built units. However, in 1984 and 1988, the General Housing Laws “converted most leaseholders into homeowners, [and also] legalized most illegal and ambiguous tenure situations of tens of thousands of self-builders and others” (Ibid, p. 72). As such, Cubans could own their homes as personal property and exchange homes of equivalent value as determined by the 1984 and 1988 laws, rather than market-set prices. Private market renting was also legalized with the introduction of the 1984 General Housing Law (Jariwala, Citation2014, p. 57), and has over time been expanded from renting two rooms in a dwelling to an entire house or apartment. This gave rise to the increase of B&Bs in Havana and other tourism areas of the country (Scarpaci et al., Citation2002).

The substantial growth of tourism and the legalization of the U.S. Dollar also transformed the housing market as the Cuban government allowed Cubans to rent (part of) their homes to tourists as ‘casas particulares’Footnote3 or to create “paladares”.Footnote4 Many Cubans who received tips (in CUC) by working in the tourism sector, reinvested this money into their housing (Duany, Citation2016, p. 87). Consequently, with more Cubans gaining hard currency, the preexisting informal market for housing sales only heightened and deepened in the 1990s and 2000s. At the Paseo del Prado, a promenade in the historical district of Havana, Cubans who were interested in moving would gather every Saturday morning for home swaps (permutas) (Peters, Citation2014b). These swaps were integral to the Cuba’s housing system allowing households or families to move. Profit-making was formally not allowed but “under the table” pesos or in-kind goods like refrigerators or motorcycles were offered to compensate for these exchanges.

However, the function of homeownership under Cuban socialism really changed in 2011 when Decree-Law 288, which permitted and regulated “free market” sales, was implemented (Grein, Citation2015). The official justification for the housing reform was that it would improve the allocation mechanisms within the housing market. For example, Hamberg (Citation2012, p. 73) describes how “cash poor but property rich families couldn’t downsize and obtain money to live on, while households seeking more space couldn’t legally use their savings or remittances to expand.” In other words, the reforms were intended to deal with such issues, allowing for greater flexibility and residential mobility. At the same time, the reforms were also meant to reduce corruption in the informal housing sector, along with the bribes of government officials (Ibid).

The Decree-Law, essentially, legalized the sale of residential properties at prices set between buyers and sellers: Cubans and foreign residents residing in Cuba can buy and sell at prices set by themselves but homeownership remains restricted to one primary residence and one vacation home (Decreto-Ley 288). Real estate transactions need to be officially registered with a government official (notario). Transactions have to occur through bank accounts and only legally acquired money can be used for acquisitions. Buyers pay an asset transfer tax of 4% of the home’s value. Sellers make a lump sum income tax payment of the same amount. In the first eleven months after the introduction of the Decree-Law, around 200,000 property transfers were registered in Cuba, of which 80,000 were sales and the remainder swaps (Peters, Citation2014b).

Additionally, the Cuban government also sought to boost international investments in the housing sector. In the 1990s and 2000s, a private rental market targeted at foreigners (diplomats or employees of foreign firms with offices in Havana) had already emerged (Scarpaci et al., Citation2002). The 2010 Decree-Law 273 expanded and facilitated foreign investment in international tourism. To this end, the 1987 Surface Law (which concedes the right of property of buildings and infrastructure on State-owned land, while the land remains in hands of the State) was extended to a period of 99 years (Decreto-Ley 273). Moreover, the Cuban government introduced the 2014 Foreign Investment Act (Ley 118), further incentivizing foreign investment in the real estate sector (Ley 118, Chapter 6) besides other sectors including hotel management, infrastructure, and logistics (Valdes-Fauli, Citation2014). Foreign actors can invest in houses for Cubans or tourists, houses or offices for foreign legal persons, and in real estate development for tourism while obtaining ownership of the buildings (Ley 118, Art. 17.1). Various tax breaks and incentives are provided to foreign investors that are partners in joint ventures or parties to contracts of international economic associations.

4. Setting the scene for a thriving property market

In this section we discuss the evidence for an emerging housing and tourism property market in Cuba and particularly Havana. We look at the role of remittances and indirect investment into Cuban real estate by Cubans – and to a lesser extent others – living overseas (4.1). We show the possibilities and especially difficulties of transnational investment in Cuba’s housing market. One opportunity, discussed in more detail in 4.2, is in “tourism property”, where those with spare cash to invest can exploit rent gaps. As the potential for tourism services is highly spatialized, this results in deepening uneven development in the Havana metropolitan areas as well as Cuba at large. Finally, we present how Cuban-international joint ventures have fared in the real estate sector and how corporate investment in Cuba is affected by changing Cuba-US relations (4.3).

4.1 Remittances and a transnational housing economy

In the absence of a mortgage market, most housing acquisitions in Cuba are funded by lump sums, although the Central Bank of Cuba also distributes some loans for home renovations by citizens. Only Cubans residing in Cuba and legal residents can buy properties in the country (Peters, Citation2014b). Consequently, Cubans with enough funds (often in CUC) have been investing in housing to solve housing issues for themselves and their families (García Pleyán, Citation2018, p. 6).

However, because Cubans often lack the means to buy real estate properties, it is a public secret that Cuban migrants with spare cash play a crucial role and invest together with family members or local business partners (Wainwright, Citation2016). For instance, in an interview during our fieldwork, one resident of Havana, who manages properties on behalf of United States-based investors, confessed:

I tell you where the money is coming from. All the money comes from the United States, I tell you. It is transferring between American banks. Cuban-Americans collect the money and bring it here on a plane or in a suitcase. But then you need testaferros (middle men) to invest the money. You know me, we are family or friends. I buy the house. I start the business. But it is yours.

Thus, many housing transactions are funded by informal housing remittances coming from the Cuban migrant community in especially the U.S. and Miami. Particularly recent migrants, with less resentment for the Cuban authorities, send or bring money to their families in Havana (Nijman, Citation1997, Citation2011). This also spurs investment rationales, as for instance, one resident of Havana confirmed to us in an interview:

They want to buy my house for 30,000 CUC and I can use the money because I may migrate to the United States where my family lives. But they are restoring the neighborhood [Old Havana], so my sons tell me not to sell. The building [or the land] will be worth much more.

Some Cuban-Americans who have economic or social motives for returning to Cuba, have also become keen on investing in Cuban housing. One interviewee, who was preparing to return to Cuba after having lived in the U.S. for decades, explained:

When my son came to the U.S., he went to live in my house together with his family. The house was getting crowded and I had no place to go back to, like a home. … The medical bills in the U.S. are very high and I cannot always afford them. My quality of life has changed a lot. I went from being an active person and a worker to someone dependent. I decided to buy a home in Cuba, in Cienfuegos, my hometown, and I am now preparing myself to stay there. I bought the house so that I could retire and take good care of my disease. I am also with family members, who live here with me, and now have better living conditions too. I do not have the Cuban benefits anymore, but I bought the house and put it on my niece’s name. She is the owner, but the house has been paid with my money.

The prospect of Cuban real estate also attracts a few adventurous investors from Europe or Latin-America, some of whom marry Cubans before they invest. Some newspapers covered stories of foreigners trusting a Cuban resident to buy a home, and later finding out they lost the property as their marriage ended or because the house was claimed on the basis of legal rights (Peters, Citation2014b; The Washington Post, Citation2015). Nevertheless, one Havana resident told us about the risk that some foreigners are willing to take to buy real estate:

I know a guy here. He’s not even Cuban. He’s from Ecuador. He bought an apartment in Cuba. However, he’s risking losing it because he has no legal rights in Cuba. … But yeah, eventually he sells, and now he’s already making profit.

Thus, international remittances and other financial donations from abroad make it possible to specifically buy and sell residential properties as financial assets. On the one hand, many Cuban migrants and their local relatives or business partners speculate on increasing land or house price values, even if the purchased homes are still used for living in.Footnote5 On the other, a sub-market in which property-related business opportunities present themselves emerges. This emerging market can be understood as extension of Cuba’s already existing market for housing exchanges (Grein, Citation2015, see also previous section).

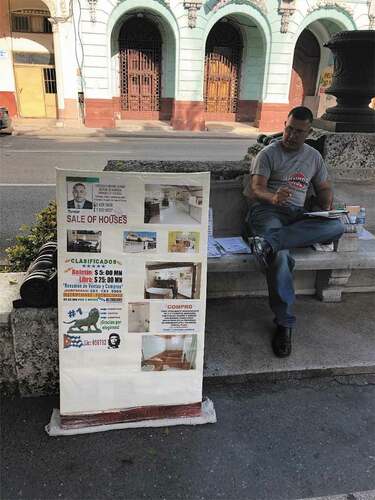

Indeed, a look at Havana’s streetscape shows that a sub-market is emerging in which “free market” housing has become a strategic asset for tourism-related entrepreneurial activities (Forbes, Citation2015). shows two adjacent homes in Old Havana for sale, providing the opportunity to be bought together and merged into a commercial property. One block away two similar residential units have already been turned into a hotel and private restaurant (). shows construction workers remodeling a recently acquired residential building for commercial purposes.

Figure 2. A former residential unit in Old Havana turned into a hotel and boutique store.

4.2 Emerging sub-markets and housing-related entrepreneurialism

Most Cuban migrants in the U.S. that buy residential properties hold no legal status in Cuba and therefore need to trust their local partners, while not getting caught by the Cuban government that officially does not allow indirect investments by individuals. This – in combination with certain taboos, especially among the older generation of exile Cubans, and the U.S. trade embargo – explains why such transnational investment activities are occurring, but are never out in the open. One interviewee, whose U.S.-based family member tried to open a restaurant in Havana, said:

My brother was buying a property in Havana to open a restaurant. But he gave up for now, because it was risky at that time. I also know about people that wanted to invest in restaurants and paper towel factories, but decided not to do so because they are formally not allowed by the Cuban government. … Nevertheless, people are betting on the future of real estate in Cuba and are willing to take that risk. In general, people are very discrete about it. [Cuban] expats are not allowed to do business in Cuba, they are usually financing the enterprises but their names are never in the open.

Many of the Cuban migrants that invest in Cuba are middle-class and work closely together with local entrepreneurs or family members (García Pleyán, Citation2018). However, their economic and extra-economic motives for investing in residential properties vary greatly depending on the family or business situation. In the so-called “high market segment” (over CUC 50,000), García Pleyán (Citation2018, p. 6) distinguishes between Cubans that have family abroad with capital to invest in a business or residential property, Cubans residing abroad that help to solve housing issues for their family in Cuba, or foreigners or Cubans abroad that want to invest in businesses on the island, a holiday home, or simply want to invest in real estate.

However, considering that wages and rents in Cuba are low and that government regulations remain tight (Portela, Citation2018), the potential of rent gap formation is primarily related to tourism property. Rent gaps are always highly localized, but in the case of Cuba particularly shaped by the potential to use property as “tourism property”. Since most of these tourists pay in the highly valuable CUC currency, profits accumulate rapidly and can be reinvested in the yet thriving property sector, enabling local entrepreneurs and their financiers to scale up investments. For instance, a testaferro residing in Havana recalls how investors sometimes buy entire apartment complexes and convert them into new businesses:

You have these apartment buildings which were once publicly owned but then split by the government. People with money come and they buy all the apartments. They flip the entire complex and turn it into a hotel.

Although many of those investors operate with “street smart” gut feeling, they also use technologies and additional services. For example, in 2013, real estate agents became eligible to work as cuentapropista (self-employed) (Peters, Citation2014b, p. 9), making it possible to establish transnational real estate networks for sales or housing exchanges (see also ). Improved internet connectivity also plays a crucial role in the lives of these entrepreneurs. Not only does it enable them to communicate with their business associates or family members living outside of Cuba, the Internet can also be used as a platform to reach out to tourists interested in renting a house or private accommodation. In 2015, the online sharing platform Airbnb started operating in Cuba, even allowing Americans to book accommodations under certain conditions (Bloomberg, Citation2015). The possibility to rent out refurbished homes to tourists and other travelers provides an opportunity to make a lucrative income or to pay-off the investment costs for buying a home in Cuba. One Havana resident said:

There are many possibilities in Havana, or outside of it. For 50,000 [CUC] Dollars you can buy a very nice house in Vedado [a neighborhood in Havana]. You can rent it out for 50 [CUC] Dollars per night, so within a year [sic, it is actually within three years, assuming almost-full occupancy], you have paid it off.

Figure 5. A real estate broker offering his services at the Paseo del Prado. That he offers his services both in Spanish and English exemplifies that he targets an increasingly transnational market.

Besides mediating between tourists, urban entrepreneurs, and private homeowners, the Internet is also widely used for advertising Cuban homes for sale to an international clientele (The Washington Post, Citation2015). Following the legalization of the broker’s profession, various internet platforms or online magazines offer homes for sale and clearly target foreign buyers as the sale prices are considerably high (see e.g. OnCuba, 2015, an online magazine which in 2015 provided classified ads for sales, among other updates on real estate, architecture and design in Cuba). Home sales are also advertised online to facilitate (non)-domestic housing demand for Cuban real estate. Cubisma.com, Porlalivre.com and Revolico.com are three examples of websites where interested buyers can look for local real estate offerings.Footnote6

The thriving residential property sector has given hope to Cuban migrants and entrepreneurial Cubans that they can earn a middle-class income in Cuba’s emerging property market. Official real estate data is lacking but Pérez and Almeida (Citation2014, Citation2015) used online advertisement statistics to calculate that in Cuba’s “low market” homes are sold for around 10,000 USD and in the “middle market” for between 30,000 and 33,000 USD. In the more luxurious “high market” sales were valued at around 130,000–150,000 USD between 2014 and 2015. House price increases are sharper in cities like Matanzas, Varadero, and Havana. Morales (Citation2014) documents that most sellers in the market are migrating Cubans that can now cash out without handing their properties over to the government without compensation.

However, the current transition within the housing sector may also come with a price. First, the inequality between Cubans who have access to dollars and those who have not is aggravated. Not only does net payment (including tips in hard currency) in the tourism sector tend to be higher (LeoGrande & Thomas, Citation2002), many of the newly opened private restaurants or hotels also attract more tourists than their public counterparts. Additionally, these paladares can use their CUC currency to buy large stocks of food from local stores, public restaurants, and other public storage rooms or distribution centers. This further inflates the country’s food prices and increases food shortages (Bono, Citation2018). It also makes paladares more appealing for tourists as these are less affected by shortages and offer better cuisine, further increasing the customer base at the expense of public restaurants and thus Cubans without accesses to CUC. One testaferro said:

I don’t expect that the government can hold this much longer. At some point, it may not be controllable anymore. The new riches with their money will become too powerful. … They are already buying groceries for their restaurants in local supermarkets. And workers from the public restaurants sell their chicken to private entrepreneurs because they can make more money that way.

In other words, the combination of economic opportunities with the existence of a parallel currency implies that existing shadow markets, by definition fundamentally uneven, are used, potentially deepened, and partially monopolized by entrepreneurs active in the private tourism industry.Footnote7

Second, the first signs of local housing booms emerge in some Cuban cities (Wainwright, Citation2016), including some neighborhoods in Havana, Matanzas, and Cienfuegos and the uneven development of housing prices throughout the country (cf. García Pleyán, Citation2018). In major cities like Havana, for instance, the market dynamics are quite strong. Yet elsewhere in the country the house price increases are less dynamic or even stagnant. This has resulted in uneven opportunities, along with arbitrary treatment by the government to discourage market transitions in cities where they can still exercise control. One Varadero restaurant worker in a paladar confirmed:

In Havana they cannot hold it back. Here [in Varadero] they can still control it. We originally had a door [in front of the veranda], but the government officials wanted it removed. … We had a separate kitchen room for cutting vegetables. They wanted us to integrate it into the larger kitchen. … As a private worker, I need a license and I need to pay taxes, even when my income is low. … In Varadero, they are holding it back still. They have the hotels. And they want to keep it like that.

It thus remains to be seen whether Cuba’s housing boom will last and whether the government allows housing-related private businesses to expand further (Portela, Citation2018).

4.3 Joint ventures and foreign investments

The 2011 housing market reforms were received with euphoria and enthusiasm in Miami and elsewhere in the U.S. and the Global North. The Guardian, for instance, headlined “Havana is now the big cake – and everyone is trying to get a slice” (Wainwright, Citation2016). Facing Cuba’s economic transformation, it was commonly believed that the housing economy would open up more and that land and real estate prices would increase (Forbes, Citation2015). This enthusiasm was also partly encouraged by Decree-Law 273 and the 2014 Foreign Investment Act (Ley 118) which further opened the housing sector to foreign investments in joint ventures (MINCEX, Citation2017).Footnote8 Many such joint ventures have traditionally been formed in the tourism sector where Spanish, French, Italian, Dutch, and Canadian developers develop and manage hotels (González et al., Citation2014; Scarpaci et al., Citation2002). However, the new regulations also made it possible for other foreign parties to develop luxury resorts and temporary residences for retirees and wealthy foreigners (Valdes-Fauli, Citation2014).

In recent years the initial euphoria came to a halt because many ambitious joint venture partnerships failed to deliver (Hirschfeld Davis, Citation2017). One interesting example of such a partnership is Esencia, a British company specializing in tourism and real estate in Cuba. Together with its Cuban partner, Esencia intended to invest in the Carbonera Club development, a luxury resort and gated community with 1,000 residences arranged around an 18-hole golf course (Financial Times, Citation2013). This project is still not completed and it is unclear whether Esencia is still involved. Another example is that of Fuego Enterprises, a diversified holding company based in Miami, that gained public recognition for facilitating inroads to foreign investors interested in doing business in Cuba (The New Yorker, Citation2015). Like Esencia, many of the intended business activities of Fuego Enterprises have not been realized, although in 2016 the company invested in Porlalivre.com, one of Cuba’s major internet platforms that also advertises housing sales (PR Newswire, Citation2016).

Since its establishment, the U.S. embargo has imposed severe restrictions on foreign direct investment and trade in Cuba (Pérez, Citation2006). Nevertheless, under the 1996 Helms-Burton Act American investors were allowed to own shares of non-Cuban corporations that engage in commercial dealings in or with Cuba, provided that this entity was not controlled by Americans and that a majority of its revenues were not derived from Cuba (Valdes-Fauli, Citation2014). Furthermore, the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations suspended Title III of the Helms-Burton Act. Title III allows American nationals and Cuban-Americans – including those who lived in Cuba and did not have U.S. citizenship at the time of the nationalization – to sue (foreign or American) companies doing business with Cuban companies if the profits of these companies are derived from, or exposed to, property and land assets legally owned by American nationals but confiscated by the Cuban government after 1959 (Padgett, Citation2019).Footnote9 Thus, particularly during the Obama administration, several investment funds were eyeing Cuban property market developments. For example, Miami investor Thomas J. Herzfeld, who runs a large closed-end fund investing in Cuba, anticipated to do more business in the country (Rescigno, Citation2015).

However, since the shift to the Trump administration, Cuba’s alleged openness for international (and real estate-related) joint ventures has been negatively affected (Hirschfeld Davis, Citation2017). Not only has the Trump administration increased economic pressure on Cuba by generally withdrawing Obama’s rapprochement politics and introducing new restrictions on Cuban travel, business, and remittances to Cuba in particular (Gámez Torres, Citation2019). The administration also no longer suspends Title III, creating serious litigation risks for many foreign or American companies that consider engaging in joint ventures or hotel management of properties that without their knowledge were confiscated from American nationals (Jackson, Citation2019). Thus, while the market has opened when it comes to housing prices set between sellers and buyers, it has not necessarily opened to American entrepreneurs involved in joint ventures, whose leisure or tourism-related real estate activities now face higher risks.

These examples show that introducing international capital into the Cuban housing economy remains contested. Indeed, the traditional “vectors of globalization” (Krijnen et al., Citation2017), i.e. commercial investment banks and institutional investors, play a marginal role in providing funding for ownership transfers in Cuba. In combination with the complex U.S.-Cuba relations, this contributes to a particular globalizing landscape where Cuban migrants and a few foreigners are the main protagonists of transnational Cuban real estate. Cuban socialism, with all its inconsistencies and contradictions, now enters a new historical phase in which transnational money is increasingly funneled into the urban built environment. That this money comes especially from the Cuban migrant community and not so much from global business, is a striking pattern of “market making” in a socialist and Latin-American housing context.

5. Conclusion

“Cuban socialism”, as any regime, has been in constant flux. During the Special Period that started with the fall of European socialist regimes, Cuba started introducing some marketization practices. This has not quite resulted in a form of “post-socialism” but rather in a hybrid form of “emerging market socialism”. This does not imply that Cuba is becoming a market society but rather that the country is slowly and selectively introducing market elements that coexist within an otherwise largely socialist framework, but which gradually may result in a different Cuban political economy. Several reforms in the early 2010s further cemented the road toward marketization and internationalization. Decree-Law 273 allowed foreign consortia and developers surface rights over urban land for the purpose of international tourism and housing development whereas Tax Decree-Law 288 allowed Cubans to buy a primary and secondary residence for the first time in the revolutionary history of the island. Together with a number of other regulatory changes these decree-laws have led to the emergence of a residential private property market.

As restrictions exist, and financial regulation and instruments remain limited, Cubans either rely on additional income, e.g. from the tourism sector, or on remittances and investments from Cuban migrants in the U.S. to acquire property. At the same time, nonresidents by-and-large need to rely on Cubans to be able to invest in the Cuban property market in the first place. This double bind has resulted in the development of different market segments, some mostly populated by Cuban buyers and sellers – thereby effectively forming a patchwork of local markets – others by a complicated mix of Cuban residents, migrants, and other nonresidents. The latter markets tend to be concentrated in select areas of Havana and in beach towns and resorts. The internationalization of Cuba’s, and particularly Havana’s, housing market is both highly selective and extremely partial. In other words, our paper demonstrates that the globalization of real estate is not solely triggered by formal (and institutional) procedures and practices of “market making”; informal property dynamics are equally important for understanding transnational ownership patterns in urban housing markets. We also showed that the remittance economy is changing as it is increasingly focused on business opportunities in the country of origin.

Notwithstanding the hybrid nature and spatialities (Golubchikov et al., Citation2014) of the Cuban property market transformation, it would be wrong to conclude that little has changed. The marketization of private residential property not only changed how Cubans find housing, but also re-introduced the idea that land and property have an exchange value and can therefore become an asset to invest in. In other words, houses are no longer solely seen as a form of accommodation but as possible sources of income. Cubans transform private homes into casas particulares (private accommodations) and paladares (private restaurants) that suit tourists’ needs. Taken together, we see the emergence of a secondary market in which houses become a strategic asset for tourist-led activities.

How, then, should we interpret and assess this housing transformation in Cuba? In many other (former) socialist as well as Latin American countries, housing transformations eventually unlocked land and urban real estate markets for international and semiprofessional investors operating in the global market economy. We do not necessarily dismiss the idea that Cuba may follow a similar pathway toward some kind of post-socialist or even capitalist future. That said, economic globalization has not so much undermined but rather reconstituted Cuban socialism (Pérez, Citation2006). Therefore, it could be hypothesized that Cuban authorities will continue to tightly regulate the housing market and mainly introduce quasi-liberalizing housing policies as a means to ensure acceptance of the socialist project: “el gobierno aprieta pero a veces tiene que aflojar”.Footnote10 Yet the fact that urban property markets have become more dynamic than ever before, and that a thriving class of urban entrepreneurs profits substantially from new housing developments, also suggests that Cuban authorities can no longer stop the train and will now be required to introduce subsequent housing reforms. The legalization of “free market” sales and modifications in land regimes may become a catalyst for wider changes in the Cuban economy and society (cf. Polanyi, Citation1944/2001), e.g. in agriculture and food, areas which are already plagued by significant problems, including scarcity and geographic and social inequalities (Bono, Citation2018; Bono & Finn, Citation2017).

Beyond the context of Havana and Cuba, we conclude that there is a dire need to study uneven patterns of real estate internationalization in other urban settings of the Global South, from cities in the Caribbean and Central America (Payne, Citation1994; Soederberg, Citation2015; see also Whiteside, Citation2019) to cities in South America, Africa, Central Asia, and the Middle East (Krijnen, Citation2018; Kutz & Lenhardt, Citation2016; Zoomers et al., Citation2017). Indeed, the question whether such housing transitions in the Global South may also trigger gentrification effects is an urgent one (Janoschka et al., Citation2014), not in the least because it touches upon broader income-related dynamics in national and urban political economies. We have demonstrated that rent gap formation is primarily tied to the potential of properties – and thus locations – to be used as “tourism property”. In other words, we argue that tourism potential is fundamental in opening up – and closing – the rent gap, implying that gentrification is not necessarily state-led, developer-led or finance-led but can also be tourism-led. More fundamentally, however, we conclude that future research should analytically distinguish better between different modes of internationalization and the dialectics of formal and informal flows of capital. This essential point, also put forward by Krijnen et al. (Citation2017), not only emphasizes that investments by migrant communities and lifestyle migrants are an important manifestation of economic globalization, but also shows that the internationalization of land and real estate in an urbanizing world is shaped and reshaped by different – and at times antagonistic – actors, and in variegated and uneven ways.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers of this journal as well as Annia Martinez, Liettyca H Ricabal, Ingrid Martinez Sollano and Richard Waldron for their comments, suggestions and valuable help.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. For instance, the Miami-based Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE) was established following the collapse of the Soviet Union and has as its mission the study of “the transition to a free market economy … in Cuba” (www.ascecuba.org).

2. In 1982, Decree-Law 50 already institutionalized a legal framework for foreign investment.

3. Casa Particular: these Bed and Breakfasts are the most popular form of tourist accommodation. The owners usually have some family ties abroad and benefit from remittances. Additionally, because the prices are paid in CUC, the owners earn considerably more than Cubans who earn in the national currency. But they need a license and pay high taxes.

4. Paladares: private and licensed restaurants, usually family-run.

5. Some Cuban migrants even went through the process of official “repatriation” to live and legally own real estate properties in Cuba. Some of them repatriated so that they can own properties in their name but still travel back and forth abroad and hold employment outside of Cuba. In total, there are about 500,000 Cubans with residency in Cuba who are currently visiting or living abroad.

6. Morales (Citation2014) documents that many homes offered on the Internet are described as “capitalist construction houses”. This advertising strategy highlights and differentiates the construction quality of the property compared to homes built after 1959.

7. At some paladares it is also possible to exchange U.S. Dollars for CUC at a better rate than at currency exchange offices where commissions are fixed at 10% for U.S. Dollars. Workers at paladares use these Dollars to send abroad, to use abroad, or to exchange at a better rate. Currencies can also be exchanged at hotels, among other places. At street level, U.S. Dollars can be exchanged illegally at more favorable rates.

8. In 2007, García Pleyán and Núñez Fernández, (Citation2007, p. 100) estimated that Cuban institutions associated with foreign entities invested about500 million USD in Cuban tourism and real estate. The new Investment Act is meant to increase this number further.

9. Most of the lawsuits under Title III have come from Cuban Americans whose families (before 1959) owned such things as an airport, a shipping dock or a cruise terminal. Housing ownership is excluded from Title III lawsuits.

10. Cuban proverb: “The government squeezes but sometimes has to loosen up”.

References

- AlShehabi, Omar Hesham, & Suroor, Saleh. (2016). Unpacking “Accumulation By Dispossession”, “Fictitious Commodification”, and “Fictitious Capital Formation”: Tracing the Dynamics of Bahrain’s Land Reclamation. Antipode, 48(4), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12222

- Anderson, Isobel, & Serpa, Regina. (2018). Cuba: Private home ownership recognised for first time since the revolution. Boston, MA: The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/cuba-private-home-ownership-recognised-for-first-time-since-the-revolution-100204

- Antúnez Sánchez, Alcides Francisco, Martínez Cumbrera, Jorge Manuel, & Ocaña Báez, Jorge Luis (2013). El Trabajo por Cuenta Propia. Incidencias en el Nuevo Relanzamiento en la aplicación del Modelo Económico de Cuba en el Siglo XXI. Madrid: Nómadas. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=18127008002.

- Backer, Larry Catá. (2014). The Cuban communist party at the center of political and economic reform: Current status and future reform. Working Papers Coalition for Peace and Ethics, 7(2), 1-59.

- Bassens, David. (2012). Emerging markets in a shifting global financial architecture: The Case of Islamic Securitization in the Gulf Region. Geography Compass, 6(6), 340–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00500.x

- Beaverstock, Jonathan V. (2010). Transnational elites in the city: British highly- skilled inter-company transferees in New York city’s financial district. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(2), 245–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183042000339918

- Bell, K. (2013). Doing qualitative fieldwork in Cuba: Social research in politically sensitive locations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.653217

- Bianchi, Raoul V. (2009). The “critical turn” in tourism studies: A radical critique. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903262653

- Bitterer, Nadine, & Heeg, Susanne. (2012). Implementing transparency in an Eastern European office market: Preparing Warsaw for global investments. Articulo - Journal of Urban Research, 9, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4000/articulo.2139

- Bloomberg. (2015). Airbnb is now available in Cuba. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-02/airbnb-is-now-available-in-cuba

- Boeckler, Mark, & Berndt, Christian. (2012). Geographies of circulation and exchange III: The great crisis and marketization “after markets.”. Progress in Human Geography, 37(3), 424–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512453515

- Bohle, Dorothee. (2014). Post-socialist housing meets transnational finance: Foreign banks, mortgage lending and the privatization of welfare in hungary and Estonia. Review of International Political Economy, 21(4), 913–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2013.801022

- Bono, Federica. 2018. “Psst … Tengo Papas!” A Substantive Approach to Cuba’s Food Economy. KU Leuven. Unpublished manuscript

- Bono, Federica. (2019). Illegal or Unethical? Situated ethics in the context of a dual economy. Qualitative Research, 146879411988617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119886179

- Bono, Federica, & Finn, John. (2017). Food diaries to measure food access: A case study from rural Cuba. The Professional Geographer, 69(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2016.1157499

- Brenner, Neil, & Schmid, Christian. (2014). The “Urban Age” in Question. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), 731–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12115

- Brenner, Philip, Jiménez, Marguerite Rose, Kirk, John M., & LeoGrande, William M. (Eds.). (2014). A Contemporary Cuba Reader. The Revolution Under Raúl Castro. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Buckley, Michelle, & Hanieh, Adam. (2014). Diversification by urbanization: Tracing the property-finance nexus in Dubai and the Gulf. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12084

- Büdenbender, Mirjam, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2019). How subordinate financialization shapes urban development: The rise and wall of Warsaw’s Służewiec business district. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(4), 666–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12791

- Büdenbender, Mirjam, & Golubchikov, Oleg. (2017). The geopolitics of real estate: Assembling soft power via property markets. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2016.1248646

- Cook, Andrew. (2010). The expatriate real estate complex: Creative destruction and the production of luxury in post-socialist Prague. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(3), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00912.x

- Corpataux, José, & Crevoisier, Olivier. (2016). Lost in space: A critical approach to ANT and the social studies of finance. Progress in Human Geography, 40(5), 610–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515604430

- De Haas, Hein. (2006). Migration, remittances and regional development in Southern Morocco. Geoforum, 37(4), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.11.007

- Decreto-Ley No. 273 of 19 July 2010 Modifica El Código Civil en sus Artículos 221 y 222. Gaceta Ordinaria no. 33. (2010, August 13). La Habana: Gaceta Oficial. gacetaoficial.gob.cu.

- Decreto-Ley No.288 of 28 October 2011 Modifica la Ley NO.65 de 23 de diciembre de 1988 «Ley General De La Vivienda». Gaceta Extraordinaria no.35. (2011, November 2). La Habana: Gaceta Oficial. gacetaoficial.gob.cu.

- Duany, Jorge. (2016). Recent changes in U.S.-Cuba relations. Romanische Studien, 3, 85–90. Retrievable from http://www.romanischestudien.de/index.php/rst/article/viewFile/117/367

- Egozcue, Sánchez, & Mario, Jorge. (2014). Challenges of economic restructuring in Cuba. In Philip Brenner, Marguerite Rose Jiménez, John M Kirk, & William M Leogrande (Eds.), A Contemporary Cuba Reader. The Revolution Under Raúl Castro (pp. 125–136). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2019). Housing financialization in the global South: In Search of a Comparative Framework. Housing Policy Debate, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1681491

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, Hofman, Annelore, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment & Planning A, 48(12), 2443–2461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16659479

- Financial Times. (2013). Cuba’s real estate rumba. http://www.esenciagroup.com/downloads/2013-06-21_FThousehome.pdf

- Font, Maurico, & Janscis, David. (2015). From planning to market: A framework for Cuba. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 35(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.12409

- Forbes. (2015). Cuba: The next best real estate investment for Americans? Washington, DC: Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/omribarzilay/2015/09/09/cuba-the-next-best-real-estate-investment-for-americans/

- French, Shaun, Wainwright, Thomas, & Leyshon, Andrew. (2011). Financializing space, spacing financialization. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510396749

- Gámez Torres, Nora. (2019) Trump administration imposes new limits on remittances to Cuba. The Miami Herald. Retrievable from https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article234796257.html

- García Pleyán, Carlos. (2018). El mercado immobiliaro en Cuba: Carencias legislativas y tributarias [Paper Presentation]. Working paper presented at the Congreso 2018 de la Asociación de Estudios Latinoamericanos, Barcelona, Spain, 23–26 May.

- García Pleyán, Carlos, & Núñez Fernández, Ricardo. (2007). La Habana se rehace con plusvalías urbanas. Temas críticos en políticas de suelo en América Latina. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 22 pp. https://www.scribd.com/doc/99309674/La-Habana-Se-Rehace-Con-Con-Plusvalias-Urbanas

- Golubchikov, Oleg, Badyina, Anna, & Makhrova, Alla. (2014). The hybrid spatialities of transition: Capitalism, legacy and uneven urban economic restructuring. Urban Studies, 51(4), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013493022

- González, Jésus M., Salinas, Eduardo, Navarro, Enrique, Artigues, A. A., Remond, Ricardo, Yrigoy, Ismael, … Arias, Y. (2014). The City of Varadero (Cuba) and the Urban Construction of a Tourist Enclave. Urban Affairs Review, 50(2), 206–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413485218

- Gonzalez-Corzo, Mario A., & Justo, Orlando. (2017). Private Self-Employment under Reform Socialism in Cuba. Journal of Private Enterprise, 32(2), 45–82. Retrievable from http://journal.apee.org/index.php/2017_Journal_of_Private_Enterprise_vol_32_no_2_Summer_parte3.pdf

- Gotham, Kevin Fox. (2016). Re-anchoring capital in disaster-devastated spaces: Financialisation and the Gulf Opportunity (GO) Zone programme. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1362–1383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014548117

- Grein, John. (2015). Recent reforms in Cuban housing policy. Chicago: Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 7.

- Gu, Chaolin, Kesteloot, Christian, & Cook, Ian G. (2015). Theorising Chinese urbanisation: A multi-layered perspective. Urban Studies, 52(14), 2564–2580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014550457

- Hall, Sarah. (2010). Geographies of money and finance I: Cultural economy, politics and place. Progress in Human Geography, 35(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510370277

- Hamberg, Jill. (1986). Under Construction: Housing policy in revolutionary Cuba. Center for Cuban Studies.

- Hamberg, Jill. (2012). Cuba opens to private housing but preserves housing rights. Race, Poverty & the Environment, 19(1), 71–74. Retrievable from http://www.reimaginerpe.org/node/6930

- Hayes, Matthew. (2015). Moving South: The economic motives and structural context of North America’s emigrants in cuenca, ecuador. Mobilities, 10(2), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2013.858940

- Henken, Ted A., & Vignoli, Gabriel. (2015). A taste of capitalism? Competing notions of Cuban entrepreneurship in Havana’s Paladares. Human Geography, 10(3), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861701000308

- Hirschfeld Davis, Julie. (2017). Moving to Scuttle Obama Legacy, Donald Trump to Crack Down on Cuba. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/15/us/politics/cuba-trump-obama.html

- Hofman, Annelore, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2019). A finance- and real estate-driven regime in the United Kingdom. Geoforum, 100, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.014

- Jackson, Dylan. (2019). As Cuba Lawsuits heat up, not all are sold on Helms-Burton’s Promise. New York: Law.com. https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/2019/08/19/as-cuba-lawsuits-heat-up-not-all-are-sold-on-helms-burtons-promise-392-66070/

- Janoschka, Michael, Sequera, Jorge, & Salinas, Luis. (2014). Gentrification in Spain and Latin America — A critical dialogue. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1234–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12030

- Jariwala, Saumil A. (2014). Cuban housing privatization: A comparative perspective on the future of housing in Havana, Cuba. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania. Retrievable from https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/184/

- Jayawardena, Chandana. (2003). Revolution to revolution: Why is tourism booming in Cuba? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110310458990

- Jiménez, Marguerite Rose. (2014). The political economy of leisure. In Philip Brenner, Marguerite Rose Jiménez, John M Kirk, & William M Leogrande (Eds.), A contemporary Cuba reader. The revolution under Raúl Castro (pp. 173–182). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Krijnen, Marieke. (2018). Beirut and the creation of the rent gap. Urban Geography, 39(7), 1041–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1433925

- Krijnen, Marieke, Bassens, David, & van Meeteren, Michiel. (2017). Manning circuits of value: Lebanese professionals and expatriate world-city formation in Beirut. Environment & Planning A, 49(12), 2878–2896. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16660560

- Kutz, William, & Lenhardt, Jennifer. (2016). “Where to put the spare cash?” Subprime urbanization and the geographies of the financial crisis in the Global South. Urban Geography, 37(6), 926–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1118989

- LeoGrande, William M. (2014). After Fidel: The communist party of Cuba on the brink of generational change. In P. Brenner, M. R. Jiménez, J. M. Kirk, & W. M. LeoGrande (Eds.), A contemporary Cuba reader. The revolution under Raúl Castro (pp. 59–72). Rowman & Littlefield.

- LeoGrande, William M. (2015). Cuba’s perilous political transition to the Post-Castro era. Journal of Latin American Studies, 47(2), 377–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X15000103

- LeoGrande, William M., & Thomas, Julie M. (2002). Cuba’s quest for economic independence. Journal of Latin American Studies, 34(2), 325–363. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X02006399

- Ley, David. (2017). Global China and the making of Vancouver’s residential property market. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2015.1119776

- Ley No. 118 of 29/03/2014: Ley de la Inversión Extranjera. Gaceta Extraordinaria No. 20/2014 (April 16, 2014). La Habana: Gaceta Oficial. gacetaoficial.gob.cu

- Mesa-Lago, Carmelo. (2014). Institutional changes of Cuba’s economic-social reforms. Washington, DC: Foreign Policy at Brookings.

- MINCEX. (2017). Cuba: Portfolio of opportunities for foreign investment 2017–2018. Ministerio del Comercio Exterior Y La Inversión Extranjera.

- Morales, Emilio. (2014). Mercado inmobiliario en Cuba: 88 mil casas vendidas el pasado año. Miami: cafefuerto.com. http://cafefuerte.com/csociedad/15586-mercado-inmobiliario-en-cuba-88-mil-casas-vendidas-el-pasado-ano/

- Morales, Emilio. (2018). Remittances to Cuba diversify and heat up the payment channels. Miami: The Boston Consultancy Group. http://www.thehavanaconsultinggroup.com/en-us/Articles/Article/63

- Mosciaro, Mayra, Pereira, Alvaro, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2021). The financialization of urban redevelopment: Speculation and public land in Porto Maravilha, Rio de Janeiro. In The Speculative City: Emerging Forms and Norms of the Built Environment. University of Toronto Press. Retrievable from https://www.academia.edu/38289671/The_Financialization_of_Urban_Redevelopment_Speculation_and_Public_Land_in_Porto_Maravilha_Rio_de_Janeiro

- Murphy, James T. (2008). Economic geographies of the global south: Missed opportunities and promising intersections with development studies. Geography Compass, 2(3), 851–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00119.x

- The New Yorker. (2015). Opening for business: A former Marielito positions himself as an entrepreneur in the new Cuba. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/07/20/opening-for-business

- Nijman, Jan. (1997). Globalization to a Latin beat: The Miami Growth Machine. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 551(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716297551001012

- Nijman, Jan. (2011). Miami: Mistress of the Americas. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Obeng-Odoom, Franklin. (2010). Urban real estate in Ghana: A study of housing-related remittances from Australia. Housing Studies, 25(3), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673031003711568

- Padgett, Tim. (2019). Trump AND Title III: Will Exile lawsuits drive investment out of Cuba – or Fizzle? Miami: WLRN. https://www.wlrn.org/post/trump-and-title-iii-will-exile-lawsuits-drive-investment-out-cuba-or-fizzle

- Payne, Anthony. (1994). US hegemony and the reconfiguration of the Caribbean. Review of International Studies, 20(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210500117863

- Pereira, Alvaro. (2017). The financialization of housing: New frontiers in Brazilian cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 604–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12518

- Pérez, Elisabeth, & Almeida, Yudivián. (2014) Mercado inmobiliario en Cuba: Algunos indicios y consideraciones. Miami: Revista ONCUBA. https://oncubamagazine.com/economia-negocios/mercado-inmobiliario-en-cuba-algunos-indicios-y-consideraciones/

- Pérez, Elisabeth, & Almeida, Yudivián. (2015) Comprar una casa en La Habana: Algunos apuntes. Revista ONCUBA. http://oncubamagazine.com/comprar-una-casa-en-la-habana-algunos-apuntes/

- Pérez, Louis A. (2006). Cuba: Between reform and revolution. Oxford University Press.

- Peters, Philip. (2014a). Cuba’s entrepreneurs: The foundation of a new private sector. In Philip Brenner, Marguerite Rose Jiménez, John M. Kirk, & William M. LeoGrande (Eds.), A contemporary Cuba reader. The revolution Under Raúl Castro (pp. 145–152). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Peters, Philip. (2014b). Cuba’s new real estate market Latin America initiative working paper. Washington: Foreign Policy at Brookings.

- Piñeiro Harnecker, Camila. (2014). Cuba’s new socialism: Different visions shaping current changes. In P. Brenner, M. R. Jiménez, J. M. Kirk, & W. M. LeoGrande (Eds.), A contemporary Cuba reader. The revolution UNDER Raúl Castro (pp. 49–59). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Polanyi, Karl. (2001 [1944]). The great transformation. The political and economic origins of our time. Beacon Press.

- Pollard, Jane. (2012). Gendering capital: Financial crisis, financialization and (an agenda for) economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 37(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512462270

- Portela, Armando H. (2018) Cuba’s real estate market is booming. But will it last? Miami: The Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article217887040.html

- PR Newswire (2016). Fuego Enterprises, Inc. desarrolla el primer sitio web de comercio electrónico de Cuba. Chicago: PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fuego-enterprises-inc-desarrolla-el-primer-sitio-web-de-comercio-electronico-de-cuba-588123952.html

- Radfar, Gabriela (2016) Una mirada crítica a la legislación laboral en Cuba: Del “Periodo Especial” y la “Batalla de Ideas” a la “Actualización del Modelo” CLALS Working Paper Series, no. 12, available online http://ssrn.com/abstract=2768377.

- Rescigno, Richard. (2015). Investing in Cuba: Tom Herzfeld sizes up the prospects. Barrons. https://www.barrons.com/articles/investing-in-cuba-tom-herzfeld-sizes-up-the-prospects-1424493673?mod=mw_quote_news

- Robinson, Jennifer. (2016). Comparative Urbanism: New geographies and cultures of theorizing the urban. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12273

- Rogers, Dallas, Lee, Chyi Lin, & Yan, Ding. (2015). The politics of foreign investment in Australian Housing: Chinese investors, translocal sales agents and local resistance. Housing Studies, 30(5), 730–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2015.1006185

- Rojas, Osmar Laffita (2014) El Pequeño Sector Privado en Cuba: Una Incógnita por Descifrar. Annual Proceedings, The Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, no.24. Miami: Florida International University.

- Rolnik, Raquel. (2013). Late neoliberalism: The financialization of homeownership and housing rights. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1058–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12062

- Rouanet, Hortense, & Halbert, Ludovic. (2016). Leveraging finance capital: Urban change and self-empowerment of real estate developers in India. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1401–1423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015585917

- Sanfelici, Daniel, & Halbert, Ludovic. (2018). Financial market actors as urban policy-makers: The case of real estate investment trusts in Brazil. Urban Geography, 40(1), 83-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1500246

- Sassen, Saskia. (2014). Expulsions: Brutality and complexity in the global economy. Harvard University Press.

- Scarpaci, Joseph L., Segre, Roberto, & Coyula, Mario. (2002). Havana: Two faces of the antillean metropolis. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Searle, Llerena Guiu. (2014). Conflict and commensuration: Contested market making in India’s private real estate development sector. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12042

- Sergio, Díaz-Briquets, & Perez-Lopez, Jorge. (2003). The role of the Cuban-American community in the Cuban transition. Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies, University of Miami.

- Shatkin, Gavin. (2017). Cities for profit: The real estate turn in Asia’s urban politics. Cornell University Press.

- Sigler, Thomas, & Wachsmuth, David. (2016). Transnational gentrification: Globalisation and neighbourhood change in Panama s Casco Antiguo. Urban Studies, 53(4), 705–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014568070

- Soederberg, Susanne. (2015). Subprime housing goes south: Constructing securitized mortgages for the poor in Mexico. Antipode, 47(2), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12110