ABSTRACT

The Gauteng City-Region (GCR) in South Africa is a paradigmatic example of extended urbanization, in which the legacy of mining and apartheid continue to impact spatial practices and the experience of everyday life. The dynamics between urban centralities such as Johannesburg and regional-scale peripheries established by this legacy characterize the “spatiality of poverty” that exists in the GCR today. Yet the relational urbanization processes occurring on these under-researched urban peripheries are also driven by the choices and strategies of people, or “popular agency,” as they negotiate both local and regional-scale spaces in pursuit of opportunities. Utilizing the northern part of the GCR as a case study, the article presents ethnographic research including a purposive sampling of informal settlement residents, government officials, and planning experts to discuss how socio-technical strategies focused on capital expenditure for infrastructure and affordable housing often reinforce existing socio-spatial inequalities. At the same time, new “popular centralities” are emerging as individual people exercise their agency to move around the region and produce alternative forms of space. Considering the agency of people calls for a decentered and transdisciplinary approach to urban analysis and spatial planning, with significant implications for both the theory and practice of urban and regional studies today.

Introduction

Contemporary urban research is confronted with multi-scalar urbanization processes unfurling far beyond commonly recognized city centers. The extended structure of this urban fabric increasingly manifests as a complex and polycentric mesh, in which urbanization processes transform the existing and create new configurations of centers and peripheries (cf. Brenner & Schmid, Citation2012; Peberdy et al., Citation2017). The Gauteng City-Region (GCR) in South Africa, which contains the centralities of Johannesburg and Pretoria, shows how a disconnect can arise between the conception of such large-scale spaces and how the region functions through people’s everyday movements and interactions. Related to widespread calls to create a new vocabulary for urbanization (Schmid, Citation2014; Schmid et al., Citation2018) and renewing the canon of urban theory from a postcolonial perspective (Robinson, Citation2006; Roy, Citation2008, Citation2014), this article suggests a means of conceiving such a complex landscape of interests and actors. It brings the discourse on centrality and peripherality from extended urbanization into conversation with the concept of poverty as a managed and enacted territory (Roy & Shaw Crane, Citation2015), demonstrating how uneven geographies like the GCR are produced by both representations of space – plans and policies and political-economic forces – as well as people’s choices as they go about their daily lives. As they seek opportunities within the material fabric of the urban, their spatial practices can either be ingrained, or iterate space anew.

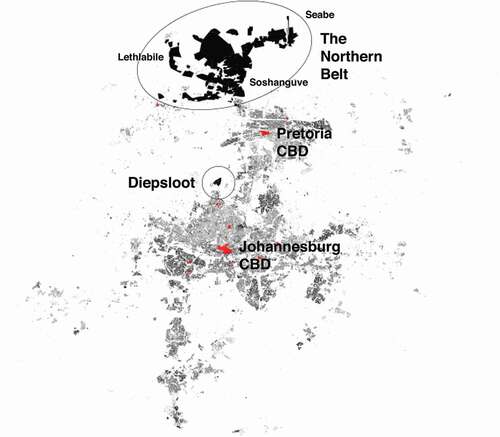

The regional dynamics of the GCR generate what the paper thus terms a spatiality of poverty: certain people and spaces are privileged through access to centrality, and others are underprivileged, or precluded from these spatial resources. This phenomenon has historical roots, the traces of which continue to influence the mega-regional urban fabric today. How the GCR operates was territorialized through mineral extraction as early as the 1880s (cf. Crankshaw & Parnell, Citation2004, pp. 348–9). State strategies for control during apartheid capitalized upon these existing characteristics, and strived to create a complete overlap of race and class (Whitehead, Citation2013) by further transposing their institutional constructs into space. While the metropolitan centralities of the region are often framed as the center of power relations and the development discourse, the “thin oil of urbanization” (Gotz et al., Citation2014) has always drawn people in from the functionally integrated areas of the overall urban region, nearly 200 kilometers in diameter ().Footnote1

Figure 1. Map of the Gauteng City-Region with centralities in red, showing primary place names discussed in the article

To unpack this, the article pursues two inherently spatial questions: How is poverty managed? And how do people respond? Currently, the primary tool utilized to counteract the spatial legacy of mining and apartheid is transit-oriented development (TOD), intending to bring geographically distant and marginalized populations to centralities. However, as the article describes, TOD, with its focus on corridor densification, is both too broad of an approach and too disjointed in its execution to account for people’s movements through this extended urban region, as they seek to “enlarge their space of operation” from the peripheries (Simone & Abouhani, Citation2005, p. 1). Accordingly, the article proposes the term popular centralities to describe how new concentrations of exchange and interaction are constituted through the agency of people, as they successfully circumvent or subvert policies emphasizing large-scale infrastructure investment. The paper discusses these phenomena in light of the continued need to innovate urban research methods and planning instruments, seeking to address the kind of development that occurs beyond known spaces, and to shift strongly ingrained historical patterns of inequality.

First, the article introduces the spatiality of poverty as a means of explaining a diachronic and synchronic conceptualization of the GCR: the structure and patterning of space and social relations as they are today, from a synchronic perspective, cannot be fully executed without recognizing how this space has evolved. The mixed-methods empirical research this article utilizes for this analysis was conducted across multiple scales to describe how the state conceives of and manages poverty in the GCR. This includes geospatial analysis, a survey conducted with 368 respondents, a total of 96 expert interviews conducted with a purposive sampling of GCR residents, government officials, and planning experts, and spending multiple days with 30 participants between 2014 and 2017. It reveals how decentralized levels of post-apartheid governance have disparate goals, often in conflict with one another. Spatial planning strategies are even further complicated by the urbanization processes occurring in spaces that are rendered invisible, due to their geographical remoteness.

Second, the article presents the agency of people as a means of explaining the micro-processes that produce the GCR’s spatiality of poverty outside the typical representations of space. Working from a decentered perspective (cf. Hart, Citation2014; Parnell & Robinson, Citation2012) – specifically, from the geographical urban peripheries – more fully reveals how the underprivileged assert “informality” as a resource in certain spatiotemporalities. This kind of agency is often connected to forms of social organization that exist within, and despite, the “formal” material spaces of urban development (Rankin, Citation2011); activities such as waste picking or street vending in Johannesburg impact the regional spatiality of poverty, as people move to access the opportunities urban centralities provide (Charlton, Citation2014; Kihato, Citation2013). Although individual people, particularly the underprivileged, are less powerful than the hegemonic forces of multi-scalar urbanization processes, their movements and interactions are just as important to the production of space. For example, in her research into cross-border shopping in the Johannesburg CBD, Zack (Citation2017) shows how informal trade comprises an estimated 10 billion ZAR (670.5 million USD) each year, in defiance of normative conceptions of economic or urban space.

To discuss such popular agency, the article relies on extensive ethnographic research conducted between 2011 and 2017 that provided insight into the dynamics of center and periphery in the GCR. It emerged from mapping the mobility patterns of 368 survey participants, who also completed several studies collecting qualitative data and volunteered geographic information (VGI) across the city-region (Howe, Citation2021). Narratives illustrating the connections between spaces on the peripheries of the GCR, and how mobility is a strategy for people living in poverty to negotiate these spaces, demonstrate the social realities that manifest in extended urban areas. The spaces of the northern part of the GCR – referred to in this article as the Northern Belt – constitute a paradigmatic representation of extended urbanization and stand in stark contrast to places like the emerging centrality of Diepsloot. There, popular agency remakes what planning attempts to delineate, infusing spaces with new context and meaning, in what Thompson (Citation2017, p. 88) describes as “an assertion of authorization that individuals invoke to create realms of opportunity.”

Aligned with critical ethnographies of development (cf. Watts, Citation2001), analyzing the GCR as a territory of poverty in which “racialized and financialized impoverishment is enacted” (Roy, Citation2015, p. 2) represents a poignant case study into the challenges facing the analysis of inequality and spatial development in extended urban areas today. By conducting multi-scalar analysis of the area as a relational whole, focusing on the reproduction of poverty, it becomes clear that neither policies nor theories adequately incorporate the popular territory-building processes in the extended urban region of the GCR, nor the distinctive spatial outcomes thereof. While the GCR has a diachronic and synchronic distinctiveness, the rhetoric surrounding poverty and centrality is widely applicable and remains under-researched in urban and regional studies. This article therefore suggests a means of analyzing and approaching planning for highly complex urban areas from a territorial perspective, by uniting questions of urbanization and everyday life. It concludes that recognizing the relational dialectics between spatial structure and poverty in the production of space could allow us to think beyond practices like TOD, and instead imagine alternative forms of centrality or propose innovative means of addressing deeply ingrained structural spatial inequality.

The spatiality of poverty

Urbanization generates a spatiality of poverty, defined in this article as the dynamic pattern of the urban fabric that effects a specific manifestation of privileged and underprivileged spaces. Spatial plans and practices tend to have a strong path dependency, as they inscribe elements of the built environment into the terrain. Yet, as evidenced by the GCR, they can be shifted through new projects and dynamics, as the macro-scale processes of extended urbanization are iterated locally through the social reproduction of centers and peripheries (Lefebvre, Citation1991 [1974], pp. 85–6, 401–4). Stanek (Citation2008, p. 74) notes: “the ‘dialectic of centrality’ consists not only of the contradictory interdependence between the objects gathered but of the opposition between center and periphery, gathering and dispersion, inclusion (to center) and exclusion (to periphery).” Where people live, where they go, how they get between these places, and what they do on the way is a product of the structure of space itself: the hidden infrastructure that enables a region to function. This dynamic is essential to understanding how impoverishment is enacted in places like the GCR, because it grounds both the management of poverty (through planning and development) and the practices of poverty (everyday subversions of the system) into space and time.

The management of poverty in the GCR has far-reaching implications for everyday life, with its 150-year-long legacy of mining and apartheid (cf. Rubin & Parker, Citation2017). Lefebvre, Citation1991 [1974], pp. 280–1) discusses the “spatiality of the state” as the primary driver of territorial production; part of this process is how a state conceives a means of categorizing and partitioning space. Theorizing from 1960s and 1970s Paris, Lefebvre (ibid., pp. 101) discussed the state-led production of urban centralities – spaces of exchange, encounter, and assembly – and agency as the reactions to this spatial production. But although his Paris-based observations about the processes of urbanization can be well-operationalized to understand the complexity of extended urban areas today (Schmid et al., Citation2018), the manifold forms of urbanization unfolding in places like Sub-Saharan Africa require questioning his assumption that spatiality is driven largely by the state (cf. Mbembe & Nuttall, Citation2004; Pieterse & Simone, Citation2013). Especially considering the access to information and technology available today, people are countering the spatiality of the state, as their agency shapes the territories in which they are not included in visions for development (cf. Ogunyankin, Citation2019).

This section of the article presents a brief diachronic history of how the GCR came to be a territory of poverty, before turning to the current state of space and spatial planning, or synchronic strategies for dealing with the “problems” of poverty and peripherality. The approach of extended urbanization – analyzing the territorial scope of the urban through qualitative research with comparative case studies (cf. Arboleda, Citation2015; Monte Mór, Citation2017) – provides insight into how these strategies are produced by policies and practices. The concept of relational poverty, urging a shifting of analysis from “places” of poverty to “territories” in which poverty is enacted (Roy, Citation2015), is also a particularly useful framework to grasp how marginalized areas must be understood within the context of the multi-scalar urban whole. Leaning on the criticisms posed by planetary urbanization (Brenner & Schmid, Citation2012), these two lenses demonstrate the relational nature of spatial and social change across multiple spatial scales and spatiotemporalities. Adopting this territory-centered view allows a connection between macro-scale urbanization processes with micro-scale movements, yielding an incredibly variegated picture of centralities and peripheries in the GCR.

Anchoring poverty into the terrain

The spatiality of poverty that exists in the GCR today began as a deliberate strategy for colonial domination, in which the spaces of a region nearly 200 kmin diameter were interdependently connected through economic, political, and social processes. According to the Gauteng Province’s current development framework: “Gauteng does not function in isolation, but has strong economic, movement and functional linkages with towns and cities that fall outside the provincial boundaries, resulting in a much larger functional economic space” (GSDF Gauteng Spatial Development Framework, Citation2013, p. 5). Yet recognition of these extents is a recent phenomenon.

Historically, the region was strongly influenced by national policy, implemented by local municipalities according to their own interpretations and governance strategies (Mabin, Citation2013, pp. 10–22). As has been documented by South African urban scholars, and in related fields such as development studies and critical ethnography, colonial rule established tight control over “native populations” over the course of the 1800s and anchored these systems of social control into emerging cities (Drakakis-Smith, Citation1992). The city of Pretoria was founded in 1855 by descendants of Dutch settlers, the Boers, who saw themselves as pioneers among agriculturally- based tribal societies (Worden, Citation1994, p. 37). When gold was discovered in what is now downtown Johannesburg in 1886, miners began extracting it with racially segregated laborers and global financial capital (Harrison & Zack, Citation2012, p. 558). Racial groups were allotted different jobs, according to what was known as the “Colour Bar,” and were geographically separated from one another into different settlement areas (Van Onselen, Citation1982). This was effectively colonial capitalism at the interstice of political and social practices, resulting in the formation of a deliberately constructed territory of poverty.

On the peripheries, at the sites of mineral extraction, races and ethnicities also continued to be spatially separated (Crush et al., Citation1991). What began as de facto policies were slowly codified into law by the first half of the twentieth century across South Africa and the GCR: interracial “mixing” was banned nationally in 1949; the Group Areas act restricted races to specific spatial locations in 1950; the 1952 Pass Laws Act meant Africans had to carry identification at all times outside of ethnically designated areas on the distant urban peripheries. Ethnicity also played a significant role in the peak of the apartheid project in the 1970s: ethnically constituted “homelands,” or Bantustans, to which all “Native” populations were legally relegated, forced people to commute from peripheries into urban centers with state-financed bus and train transit (Platzky & Walker, Citation1985).Footnote2 As Kihato (Citation2013, p. 5) explains, the apartheid spatial landscape “produced a group of people who lived and depended on it, but could not claim it as their home … and although they toiled in its mines, industries, and streets, they had no rights to live in it or make decisions about its future” ().

Figure 2. The “cruciform” of the city-region and its peripheral “Bantu residential areas” for nonwhite racial groups, NRDC Red Report, 1957, map no. 19, from Fair (Citation1975) (left). The boundaries of the Bantustans in the 1970s compared to current provincial boundaries, GCRO GIS Map Viewer, http://gcro1.wits.ac.za/gcrojsgis (right)

As the centralities of Pretoria and Johannesburg expanded, growing white-designated areas often came into conflict with areas designated for other racial groups. These racial majorities were almost always forcibly removed to even more remote geographical peripheries (cf. Murray, Citation1987). Regional-level planning bodies were established in the 1970s to control these movements, an implicit recognition that the “spatiality of the state” enacting apartheid was necessary on multiple scales (Fair, Citation1975, p. 11). Yet a strong resistance to the regional tier of analysis and development persisted, in part due to the historical independence of the major metropolitan municipalities and trajectories of their respective developments (Mabin, Citation2013, pp. 20–22).

Accordingly, the spatiality of poverty that exists today began as a strategy of control over a landscape of extraction. It was shaped by successive waves of relegation (cf. Wacquant, Citation2016) outward for nonwhite populations, which characterized apartheid territory-building on the regional scale. Yet at the end of apartheid in the 1990s, the seemingly rigid structure of the city-region began to shift. A “mushrooming” of informal settlements occurred when access to centralities was permitted for all races, and people were legally allowed to exercise their agency (Huchzermeyer et al., Citation2014). Todes et al., Citation2008, p. 7) examined demographic changes after apartheid, including migration and urbanization rates, noting: “access to employment is a smaller motivating factor in choice of location, with some 42% locating in places where they have social networks, and another 30% where they are able to access secure tenure.” Such phenomena remain observable among the GCR’s urban centralities, although the emergence of new informal settlement areas has slowed significantly since 2008 (Huchzermeyer et al., Citation2014). But the new configuration of spaces on the regional scale resulting from these shifts is incredibly complex, and the processes occurring on the GCR’s peripheries – the apartheid project’s sites of exploitation and population control – often remain obscured. These are the spaces in which poverty continues to be enacted, as multi-scalar analysis of ongoing policies and social practices reveals.

Disjointed conceptions of poverty and TOD

There are multiple tiers of governance responsible for spatial planning and urban development in the GCR today, each of which approach the legacy of extended urbanization from colonialism, mining, and apartheid in different ways (cf. Mabin, Citation2013). Their strategies for grappling with this spatiality of poverty are often in conflict with one another. The Gauteng Province is responsible for regional transit and human settlements. It promotes the idea of cruciform urban development, like the bars of a kite: a north-south axis along the national highway connecting Pretoria through Johannesburg down to the energy-producing center of Vereeniging on the Vaal River, and an east-west axis connecting the two airports of O.R. Tambo and Lanseria through northern Johannesburg.Footnote3 Along the edges of this “kite,” on the distant peripheries of this nearly two-hundred-kilometer-in-diameter region, they have conceived “mega human settlements” to deliver the most housing possible on the cheapest land available, connected by highways (Ballard & Rubin, Citation2017).

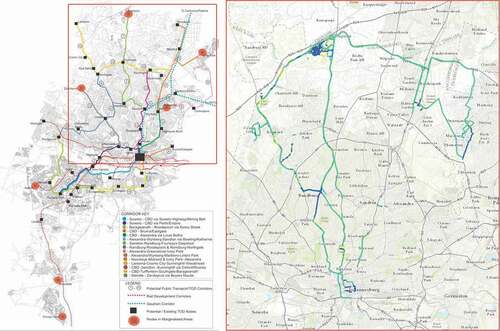

In direct contrast to this, the City of Johannesburg is actively promoting a strategy of densification, and of setting a mandatory urban edge on outward growth.Footnote4 They, too, promote transportation – in particular through an initiative once entitled the “Corridors of Freedom” (cf. Harrison, Citation2017) – but they have little control over what happens outside their borders. They see Gauteng as an interdependent “region of cities.” And yet another state agent, the City of Tshwane metropolitan municipality containing the city of Pretoria, is fixated almost entirely on connecting former Bantustan spaces of the north to the city center with transit, continuing to build peripheral housing and developing “urban core densification” for retail in these remote spaces (CoT City of Tshwane, Citation2016). These responses to the legacy of apartheid all seek to address spatial inequalities, yet the question remains: How can planning realistically address such dynamics of complex, urban centralities and peripheries, which are highly ingrained into both physical spaces and social practices?

These provincial and municipal attempts to reconfigure urban space do not fully address the multi-scalar spatiality of poverty in the GCR, which precludes them from understanding poverty as constructed “territory” rather than as “places” (cf. Roy, Citation2015). This is particularly evident when their objectives diverge, and when the national government applies pressure to provide as much housing as possible.Footnote5 Government spatial planners and developers typically view the problem of poverty as socio-technical: they counter impoverishment with infrastructure and private sector, state-subsidized affordable housing or infrastructure. Yet this does not lead to high-quality urban spaces on the peripheries, as an urban planner with the City of Johannesburg noted: “Developers aren’t interested in the long-term impact of things … the costs aren’t theirs to worry about, so it’s hard to motivate them.” A former City Manager also cited a lack of concern for “social good” in development practices: specifically, the overriding power of developers to drive where development occurs rather than considering whether or not people can truly inhabit the spaces of the urban periphery where the cheapest land is available.Footnote6 It is simply easier to work with existing models for mass producing housing as a tabula rasa on cheaper, peripheral land than it is to negotiate the complex palimpsest of the existing urban fabric. This was done during the apartheid era, and today, it follows neoliberal logics of housing production Roy (Citation2010) has described as “poverty capitalism.”

Several million people reside on the peripheries of the northern GCR, which are so geographically remote that transit completely dominates everyday life in these mass housing environments (Howe, Citation2021). Yet there is very little academic research into such spaces (cf. Gotz et al., Citation2014; Simone, Citation2004b). The Gauteng City-Region Observatory has conducted some, which shows that there are higher concentrations of multi-dimensional poverty in areas far away from urban centers (cf. Mushongera et al., Citation2018, pp. 113–6). They conclude that more extensive area-based studies to develop specific solutions on the district level are required. While this is certainly true, area-based strategies do not adequately address the powerful path dependencies of urbanization and inequality that underlie the multi-scalar production of space in the GCR. “The urban landscape still has the poorest the farthest away … so the distant urban peripheries have changed from a racial to an economic division” noted a Gauteng Province transit planner. This sentiment was echoed by the CEO of an affordable housing development company, who explained “a strategy that doesn’t seek to reduce travelling distances can never be the main apparatus of development, because transit can’t magically create local growth or reduce inequality”.Footnote7

Yet innovative strategies for the specific spaces of the peripheries remain almost entirely absent from this discourse – in part, because the fact that so many people are living so peripherally presents a true conundrum for spatial planning, requiring new and potentially more risky development models (cf. Butcher, Citation2016). In 96 interviews with a wide range of stakeholders – from government officials to academics to the residents of peripheral settlements and the NGOs who represent them – regional-scale peripheries like the Northern Belt were almost always absent from the discourse. Instead, transport-oriented development (TOD) is simply equivocated with improvements in sustainability and access to opportunities for the poor (cf. Croese, Citation2017).

TOD has several implications for the GCR. First, it has many unintended consequences that are challenging to predict in advance, ranging from the evolution of the urban land market to what happens to people who are displaced by development (Howe, Citation2018). Harrison (Citation2017) discusses the challenges of enforcing affordable housing creation in corridor development in the GCR, despite well-formulated planning policy. Secondly, TOD is based on what expert planners recognize as centers and connecting the peripheries to them, rather than analyzing the conjunctural relationships between them and the new “transversal” modes of spatial production that unsettle the logics of markets and state strategies (cf. Caldeira, Citation2017). While asset provision such as housing on the urban peripheries has led to slight increases in absolute household income and savings for the poor in the GCR, there is little evidence of changes in peoples’ actual residential locations or their trajectories through the city (Charlton, Citation2013). Third, policies in which the objective is to move people to centers does not mean that these people find opportunities in highly competitive established centralities. TOD is therefore often ill-equipped to incorporate micro-scale behaviors – so crucial to the context of urbanization in the GCR – and risks concentrating privilege along the very corridors it intends to make more equitable. Its success is predicated upon strong incentives for developers and considerable buy-in from underprivileged communities, if it is not to result in significant displacement (Todes & Robinson, Citation2019), continuing to perpetuate or even exacerbate the existing spatiality of poverty.

As Hart (Citation2006, p. 995) discusses, centers and peripheries “continually make and remake one another” through political-economic and cultural-political processes – highlighting the missing link between the macro-scale of urbanization processes and the micro-scale of everyday movements of human bodies that physically produce a region. Formulating more appropriate policies would mean following the everyday movements and choices of people throughout the region, in the fabric between the bars of the “kite” conceived by provincial master plans, where the vast majority of the population resides. Like fabric, people living in poverty rely upon a certain degree of elasticity and flexibility to navigate difficult terrain and generate their own form of power, and do not necessarily make the kinds of choices one might expect regarding opportunity and movement. Although ethnographic narratives can be “cryptic and extended” (Simone & Pieterse, Citation2017, p. 121), they provide us with a grounded means of approaching the popular centralities. As the next section illustrates, examining these forces calls into question whether approaches like TOD can really contest the multi-scalar inequality of the GCR. If people are finding ways to create their own kind of centrality, could supporting this become a means of shifting the spatiality of poverty in extended urban regions instead?

New centralities through popular agency

Popular agency is defined in this article as the spatial practices of individual people, as they move through and interact in space to generate “realms of opportunity” (Thompson, Citation2017, p. 88). In South Africa, for example, there have always been ways in which people subverted the structures of apartheid spatial planning through the multi-scalar practices everyday life, ranging from people constructing their own housing to municipalities failing to enforce the Group Areas Act (Chaskalson, Citation1986) and the evolution of the minibus taxi system. Such phenomena contributed to the eventual collapse of apartheid (Bonner & Nieftagodien, Citation2008). Agency is thus able to rearticulate both local spaces as well as the greater urban fabric, through the shifting of spatial practices that imbue places with new power and meaning.

This section examines the process of how people either produce their own centralities or commute to existing ones, exercising their agency by moving throughout the Gauteng City-Region. As a result of the specific spatiality of poverty in the GCR, institutions tend to build peripherally and it is assumed people stake their claims to space to “valuable” places by commuting to existing centralities, as was the practice under apartheid. Mixed-methods research into mobility in the GCR using volunteered geographic information (VGI) points at a multitude of reasons why this occurs, but it is largely a result of the confluence of geographic and economic peripherality. The interdependent urban region is simply too large for people to move to its primary centralities (Johannesburg and Pretoria) on a regular basis without significantly impacting everyday life.

Instead, people do not always move in the ways one might expect, for example, between peripheries and the nearest centers according to major transit corridors: they utilize the distinctive complexity of the region. Some travel at regular intervals to very different destinations, often seeking work using many modes of transit; some are able to walk to opportunities because they have carved out a precarious “toehold” for themselves in the urban fabric; others spend intervals living between members of their family on distant peripheries and more centrally located areas (Howe, Citation2017). Maps of these popular trajectories reveal that what were once considered peripheral parts of the region’s urban edge are becoming new kinds of centralities, as people connect into these spaces and break from apartheid-era commuting patterns.

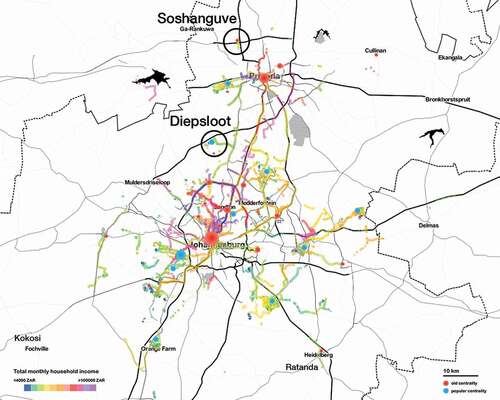

How “people as infrastructure” (Simone, Citation2004a) impact the spatiality of poverty is well-illustrated by the northern part of the GCR, stretching from the edge of the City of Johannesburg through Pretoria across provincial lines, into what was once the Bantustan of Bophuthatswana. Strong patterns of movement were established in what this article entitles the Northern Belt under apartheid, controlling the means of production and everyday life (Drummond, Citation1991, p. 343). Today, this space contains very different degrees of opportunity, as apartheid plans and trajectories are being popularly reconfigured by people. Adding to this complexity, the ability of people to exercise their agency is impacted by how the urban peripheries are being commodified, linking to analysis of neoliberal attempts to address poverty through internationalized, “pro-poor” and “pro-market” models linked to market-based principles (Katz, Citation2015, p. 69). The following ethnographic narratives from the Northern Belt emerged from four participants in expert and mobile interviews from 2015 to 2017, and VGI studies with 30 participants and 368 participants in 2015 and 2016, respectively. They show how these urban peripheries are iterated, and how the specific structure of space has a significant impact on everyday life in this extended urban region ().

Figure 3. Map of participants in a 2016 study collecting VGI on everyday mobility in the Gauteng City-Region, in which the color of pathways corresponds to income on a color gradient. Major established centralities like the CBDs of Johannesburg (red) contrast with emerging popular centralities for marginalized populations like Diepsloot (orange) and illustrate the continued disconnect between social groups in the GCR

A region of peripheries …

A vast sea of houses occupies the furthest expanses of the GCR, spilling out of the Gauteng Province into the coal, iron, and platinum-producing mines of the North West Province and Mpumalanga. While the Northern Belt may evoke lower-middle class suburbia upon first impression, these areas are extremely geographically remote spaces that reveal the dynamic interplay between center and periphery. During apartheid, bus and rail routes were established to connect them to the centrality of Pretoria, requiring multiple hours of travel per day for people removed from the city in 1974 (Drummond, Citation1991, p. 339). The Northern Belt, on average, is located 92 km from the Johannesburg CBD and 50 km from the Pretoria CBD, sometimes utilizing a set of rural roads passing by lodges and private game reserves. The combined population of these areas is more than 1.2 million people and it covers roughly 960 square kilometers; the famous township of Soweto, by comparison, has a similar population, yet is only around 200 square kilometers (cf. Howe, Citation2017, pp. 139–143). Peripherality and commuterization have had two primary consequences for space and everyday life in the Northern Belt: there is less pressure for land, so people have more personal space – but they spend most of their time commuting elsewhere to take advantage of the resources lacking in their own areas. For people residing there, travel is their primary household expenditure: on average more than 50% of the total monthly income reported by fieldwork respondents in 2015 and 2016. This mobility is a form of agency, disconnecting people from space locally and instead launching them throughout the GCR in search of opportunity.

There are also significant differences in the degree of precariousness, gradient of access, and level of development across the Northern Belt. “Lettie” lives in Zone 7 of Soshanguve VV – one of the 63 “blocks” of government-subsidized housing that contain Soshanguve’s estimated population of 403,162 (Firth, Citation2011).Footnote8 This is one of the points of the Northern Belt nearest to Pretoria. “The traffic here is horrible!” Lettie exclaimed while walking around her neighborhood: rush hour starts just after 5.00 am and it takes over 1.5 hours to reach Pretoria at 6.30 am, as opposed to 30 minutes at off-peak times. Yet she continues to live in “Sosh VV,” to a large extent, due to the state-subsidized housing that makes her life affordable and the taxi system that connects her to her workplace. Lettie lives in what she calls “an affordable home”: a state-subsidized house, for which her parents pay according to their income. The rate of their mortgage is 3,500 Rand (245 USD) per month and the original sale price was 320,000 Rand (24,000 USD). Most of Lettie’s travel begins at the local mall, Soshanguve Crossing, where she can use free WiFi. She usually walks or takes a local taxi to get there, and another to get to Pretoria. For 64 Rand (4.50 USD) per day – considering there are approximately 21 working days per month – this means she spends around 1,350 Rand (95 USD) on transportation, which was approximately 40% of her income at the time. She could only afford to stay in Sosh VV because so many extended family members shared mortgage costs and daily expenses.

There are even more remote parts of the Northern Belt that are dependent on the mega-regional scale of the GCR. “Olga” is thirty-six years old; she and her husband grew up in a small Setswana-speaking village named Seabe, a strip of land that was the easternmost islet of Bophuthatswana.Footnote9 Following the same trajectories as apartheid, she often commutes to a job in Pretoria. She works a maximum of four hours per day, because she travels over three hours in each direction to get there from Seabe. Olga wishes the train were still running, “ … but they had to close it down, because of violence, because too many people were getting stabbed and robbed.” She must depart Pretoria by approximately 14.15 to get a taxi home; otherwise she may be stranded there until the next day.

The damaging spatiality of apartheid – an enactment of poverty – not only affected the territorial formation of space, but continues to impact family structures and individual lives. Olga and her family represent this disjuncture in lived space, permanently locked into cycles of semi-migration in pursuit of the opportunities the region has to offer. Her husband, “Thabo,” has been living separately in Tembisa, a large settlement in Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality east of Johannesburg for twenty years, working as a gas station attendant near O.R. Tambo International Airport. Their two sons reside with her in Seabe; her teenage daughter lives with Thabo to attend school. Lettie, too, spread her family across multiple provinces among relatives. Her newborn son was living with her at the time she was interviewed, but she has two older daughters who live with her parents over 270 km away in the small Limpopo village of Ga-Masemola. This trip costs approximately 190 Rand (13 USD) per direction and lasts four hours; Lettie can afford to do this approximately once a month.

These spatial practices occur not just in the Northern Belt, but all around the GCR. Thus, from the perspective of the GCR’s inhabitants, this regional-scale territory appears less as a region of cities traversed by central axes, and more as a complex mesh of trajectories between spaces of family and opportunity. These pathways are flexible and adaptable in ways that infrastructure investment like TOD is not. In such an extended urban region, TOD may even exacerbate patterns of structural racism, “for instance, by diverting funding from bus transit that serves minority communities, creating new physical boundaries that reinforce segregation, and of course creating new pressure on land prices in low-income areas” (Chapple & Loukaitou-Sideris, Citation2019, p. 16). Considering that most of the population in the GCR lives within this mesh – the fabric rather than the axes of the kite – strategies for fostering centralities where people live are urgently required, rather than simply transporting them to existing ones.

… and popular centralities?

Diepsloot is a relatively well-located settlement, 45 km away from the CBDs of both Johannesburg and Pretoria. To many, Diepsloot represents the paradigmatic informal settlement Harber (Citation2011, p. 5) has described as: “the hard reality of South African poverty … a dense forest of shacks, crowds of unemployed people milling on the streets, and attempts by some at small-scale commerce in makeshift stands.” Yet analyzing spatial practices in Diepsloot reveals much more complexity than simply a “place of respite outside of the state’s gaze” (Kihato, Citation2013, p. 18). While it may often be referred to as an informal settlement, the land was designated by the state to relocate people from another township; it then ceded control to these people to construct their own environment. Today, a wide range of actors create spaces across a spectrum of so-called “informality,” from self-building to rental arrangements, government-subsidized housing, and private developer loans. The state is complicit in the production of such spaces throughout the GCR, calling into question the usefulness of formality/informality as a binary concept.

Over time, through this implicitly sanctioned agency, Diepsloot evolved into one of the major gateways for growth and migration into Johannesburg (cf. Landau, Citation2016). One of the primary reasons people can exercise their agency is there because of its geographical location, allowing them to assert a form of power that is generating centrality. The pathways for opportunity are considerably shorter than for people living in the Northern Belt. It is well-connected the national highways with the minibus taxi system, to access domestic work in nearby gated communities or jobs in industrial parks. The taxis that travel to the Johannesburg CBD typically cost 18 Rand (1.35 USD) and require 60–90 minutes of travel at peak time; those headed to Pretoria cost 16 Rand and require 45–60 minutes of travel at peak times. Rush hour traffic begins at 5.30 am toward Johannesburg; however, many job seekers rise as early as their more northern counterparts to begin moving throughout the dense urban fabric of the region.

As a result, people can enact their own kind of control and structure over this space locally, while also using it to connect to other spaces regionally. Their agency is crucial to subverting the macro-processes of development and capital accumulation that centralize power in space and time, in ways which they cannot do if tied to such intense patterns of commuting or nearer to more regulated urban centralities (). For example, while unemployment is high in Diepsloot according to census data (StatsSA Statistics South Africa, Citation2011), there is a proliferation of local businesses that operate outside the constraints – and taxes – of the formal market system.

Figure 4. Comparison of the City of Johannesburg’s “Corridors of Freedom” (COF) proposed bus-rapid-transit TOD route connecting Diepsloot to the global financial district of Sandton (left), and the paths people currently take primarily with the minibus taxi system (right). The latter is a map of a volunteered geographic information smartphone study participant, showing multiple modes of transport; dark blue is for walking, green for taxi transport, and yellow for “tilting” when the person was looking at their phone). The COF is a municipality-level plan, and Diepsloot is not a part of TOD plans for the City of Tshwane (Pretoria)

Mome’s Place is a pub located near one of the settlement’s primary thoroughfares.Footnote10 Mome immigrated from the Limpopo Province to Diepsloot in 1996, after completing his high school education. Through his network, he began a streetside business in Diepsloot selling fruits and vegetables; he was able to upscale his business into a shebeen, or local tavern, and start supplying other shebeens as a beverage distributor. Mome gradually solidified his position as the primary distributor of liquor in the area, lending him significant social and economic power. His pub is a regular meeting place for members of the current party in power, the African National Congress (ANC). Although he claimed in interviews to reside in Diepsloot, his home address is in Bryanston – one of the most expensive areas of the region to own property, in the elite, former white area directly adjacent to the international financial hub of Sandton. However, being a member of the community remains important to his identity as well as his business model. His story is indicative of how people residing in places that become more central can subvert economic and cultural domination through accumulation of spatial and social capital. Mome’s story therefore hints at both the patronage networks characteristic of the township, as well as the alternative social relations poverty necessitates, which Halvorsen (Citation2018, p. 11) describes as “alternative ideas and practices of urban territory.”

Demonstrating the interdependencies of the GCR, Diepsloot also provides spatiotemporal opportunities for people from the Northern Belt. Miss Vi lives in Lethlabile, one of the last apartheid-era mass resettlements from 1985, on the border of former Bophuthatswana.Footnote11 She resides with one of her sons in a concrete-block structure on her parents’ property; this land was given to them by the apartheid government. Neither she nor her parents pay any sort of monthly fees except for electricity; her other son lives with his father in Randfontein, west of the Johannesburg CBD, to attend school. Miss Vi’s essential costs are her daily expenses, those of her children, and transportation. It costs 11 Rand (75 cents) to the nearby platinum mining town of Brits, 38 Rand to Pretoria, and 90 Rand (6.50 USD) to reach Diepsloot. “In town you don’t have this kind of space and life is too hectic. People are always wanting something from you, you have to hustle all the time, it’s not safe and you can’t be happy,” she explains.

Places like Diepsloot provide a toehold for people from further away to access the opportunities of the cities, becoming more central itself in the process. Miss Vi estimated that 30% of area residents seek work in the City of Johannesburg 110 kmaway; she lived in Diepsloot for five years trying to find work as an entertainer, singing and auditioning for TV shows. Her children were both born during this time, and were sent to live with her parents. She commuted home each weekend, locked into a pattern of what could be termed circular regional migration. She eventually landed a role on a nationally televised show, playing a character in a women’s prison; it films two months of the year in Johannesburg. During this time, she lives in Diepsloot; otherwise, she lives at home with her parents and younger son. Relative fame has obtained her a place of significance in Lethlabile. She began running her own entertainment company, producing events for hip-hop artists in local pubs and attracting external sponsors, such as radio stations, to fund these events. Both her local connections to her home and her mobility around the region allow Miss Vi to exercise her agency in ways which would otherwise not be possible. This is true in the Northern Belt and all around the edges of the entire territory, in places whose names only seem to appear in census data: Ratanda, Kokosi, Zamdela, Ekangala.

Supporting or precluding popular agency

Understanding such narratives is crucial to the pursuit of rethinking urban analysis and policymaking through the multi-scalar processes of urbanization and everyday life. Current planning initiatives in the Northern Belt focus almost exclusively on large-scale capital expenditure proposals for housing, transportation, nodes with retail-oriented national and international chains, and a very limited scope of office space (CoT City of Tshwane, Citation2016). Situating development on the urban edge of the entire region means following this same patterning of commuter settlements that shaped the GCR’s landscape of extraction. It also effectively creates a captive market on the peripheries, which is being internationalized and financialized by ongoing development. Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life notes that colonial imperialism has been integrated into new strategies for economic and cultural domination in the form of “massive trading posts (supermarkets and shopping centres); absolute predominance of exchange value over use; [and] dual exploitation of the dominated in their capacity as producers and consumers” (Lefebvre, Citation2008, p. 26). These phenomena in the Northern Belt illustrate the kind of distinct complicity in development by the state and capitalism (cf. Hart, Citation2002, pp. 6–7).; Hart, Citation2014). Ligthelm (Citation2008) has noted a decline in informal vending and increasing debt exposure in Soshanguve – the part of the Northern Belt where Lettie resides – since the implementation of malls since 2000, describing it as a patriarchal model of development.

While Diepsloot is peripheral and precarious in an economic and socio-cultural sense, compared to many other places in this highly unequal region, it is not invisible. Like the more famous townships of Soweto and Alexandra before it, Diepsloot is a centrality for a specific segment of the population, and carries ever more weight in the spatial structure of the territory – which is being widely subjected to such predatory forms of development too. For example, Diepsloot receives high levels of capital expenditure from the state (cf. Harber, Citation2011) and most of the funding has been allocated for affordable housing, health and human services, and education. However, many commercial developments, primarily malls, have also gradually arisen over the past decade.Footnote12 Development is a double-edged sword, because the “formalization,” or commodification, of transactional activities discourages network-based strategies for income generation on which so many of the settlement’s inhabitants rely. Like in Soshanguve, this kind of centrality is based on extraction, and symbolizes the increasing commodification of informal relations by the state and private capital on the peripheries. It is a threat to the kind of social organization and activities that have succeeded within and despite deeply entrenched structural spatial inequality.

Spaces like the Northern Belt pose a poignant dilemma for spatial planning and urban development. The size and scale of its population makes it impossible to relocate people closer to opportunities, and better connecting them to existing centralities does not mean that their fundamental problems will be alleviated. In relatively monofunctional, remote settlements, it is also harder to attract attention from a government with limited resources and many urgent challenges. Due to the specific spatiality of poverty in the GCR, other places – in particular, areas where wealth and poverty collide – receive this attention instead. It is more convenient to discount the peripheral spaces as the jurisdiction of another municipality, or another province, neglecting how the interdependent whole is produced relationally (cf. Leitner & Sheppard, Citation2018).

“City” can be made of the existing fabric of the urban, like it has emerged in Diepsloot. If the ingrained spatial legacy of mining and apartheid are to be overcome in places like the Northern Belt, people should be supported in exercising their agency to create such centralities from below, so they can break cycles of commuting and access valuable spaces more easily from where they reside. Because centrality emerges through connection – proximity to the activities of exchange and encounter – programs and spaces could be reoriented to support this. Much more research is required into how people are actually moving and interacting, if policy is to better foster civic life, build on existing socioeconomic opportunities, and support families in their daily lives.

Conclusions and implications

This article utilizes the Gauteng City-Region (GCR) to demonstrate how uneven geographies result from the governance of poverty and people’s corresponding tactics to negotiate or subvert these forces. A long history of relegation across this region, conceived of by the state as an element of the apartheid system, established a persistent spatial structure between urban centralities and remote, dependent peripheries. As a result, commute-oriented places like the Northern Belt are both locally and regionally isolated, and people have few opportunities to overcome these spatial dynamics. However, places like Diepsloot, despite appearing as pockets of poverty, can generate centrality because people are surrounded by pockets of affluence, and they can access social and economic opportunities throughout the regional-scale space. Thus, these case study areas reveal how space itself is an invaluable resource. Understanding the specific ways in which poverty is being inscribed into space, how it is being reproduced by policy and in practice, is therefore essential to formulating new, more accurate terminologies for what is occurring, and new strategies to overcome it.

To demonstrate this, the article draws from geospatial analysis, a survey, expert interviews, and site analysis to show how urbanization driven by mining and apartheid anchored poverty into the terrain in the GCR. This articulated the terrain to create a spatiality of poverty managed and enacted through policy decisions and spatial strategies, which are based on the existing material environment and lack a territorial perspective. This occurs, in part, because planners conceive of poverty statically, in terms of areas, rather than in terms of the process generating a relational whole. It is also because socio-technical measures like transit-oriented development (TOD) are typically proposed as the solution to countering centuries of inequality. Multiple tiers of government exacerbate the problem of static conceptualization with conflicting visions of what the GCR should be, even if they do agree on utilizing TOD. The provincial government’s “kite” plan for developing infrastructure and peripheral mega human settlements, for example, competes directly with the “region of cities” concept for density purported by the Johannesburg local municipality. Considering poverty as bounded areas within the greater urban fabric, regardless of which conception prevails, means that the root causes of structural spatial inequality are not being addressed.

The article points out the dichotomy between conceptions of centralities and peripheries and lived realities, because the agency of people – or people’s everyday lives and movements and choices – driving urbanization and reconfiguring space is not adequately incorporated. In contrast, the article presents an empirical analysis of how the GCR functions using mixed-methods research: specifically, extensive ethnographic narratives and a smartphone application collecting volunteered geographic information. It presents the GCR as a paradigm of extended urbanization, articulating centralities and peripheries across vast scales as people move and interact in space and time. Responses in geographically remote, peripheral spaces like the Northern Belt – home to millions of people – reveal persistent apartheid-era commuting patterns, as the article describes through the narratives of Lettie and Olga. Peripherality has dramatic consequences for their everyday lives and their families. TOD, as a representation of space, simply isn’t comprehensive enough to address this complexity in how people in this territory of poverty are living and moving.

However, new urban centers are emerging in the form of popular centralities: places like Diepsloot are created largely by people themselves, where poverty is arguably less stringently managed and alternative social and economic opportunities arise. The empirical work the article discusses suggests that poverty can be more usefully conceived when considering the trajectories people take through the region, how these spaces relate to one another, and what kind of alternative practices they already contain. This hidden infrastructure, a subversion of geographical and economic constraints, continually shifts and decenters the GCR to inscribe new forms of power and opportunity into space and provide a toehold for people marginalized by the legacy of mining and apartheid. As the narratives of Mome and Miss Vi demonstrate, people can enact their own kind of control and structure over this space locally, while also using it to connect to other spaces regionally. However, such multi-scalar, lived experiences are simply not adequately included into the canon of urban theory or planning practices, and this prevailing conception precludes formulating innovative development strategies that could better support the agency of people.

The concept of extended urbanization is useful in describing the new scales and forms of the urban, and the altered structure of space far beyond recognized urban centers (cf. Brenner & Schmid, Citation2012; Topalovic, Citation2017). However, the literature on extended urbanization does not attempt to “follow the people” (Marcus, Citation1995), or analyze relational poverty and inequality. The approach described in this article shows how much can be revealed about the processes of multi-scalar territorial production through explicitly analyzing the spatiality of poverty and popular agency. People, as they move around and interact in the GCR, are embedded into urbanization processes, and the management of poverty is actually a mode of territorial production. Identifying the manifold forms of poverty in such an extended urban region should therefore be considered essential to understanding the relational production of territory. Places like the Northern Belt and Diepsloot belong in the canon of urban theory, and the value of popular agency should be seriously considered by urban planners.

The implications of popular centralities are not yet clear. In the Gauteng City-Region, the core-periphery dynamics, alternative forms of social relations, and complicity of state in production of poverty are phenomena visible in many territories today. The methods described in this article allow us to identify which questions to ask and which future research directions could engender urban transformation. Urban studies and poverty studies could therefore greatly benefit from being brought into further dialogue with one another, using empirical and comparative cases to find linkages between critical theory, practice, and activism in pursuit of creating more equitable and sustainable urban environments. As Rankin (Citation2011, p. 106) describes: “Unexpected similarities in experience across connected historical geographies could become the foundation for critical practices, common responses, and alterative trajectories.” We need to think policies through these findings, through spatiality and agency, revealing the enactment of poverty and seeking ways to better support people where they are rather than moving them to centralities. This could gradually shift static conceptions of poverty based on demographics and statistics that reduce difference to generalized socio-technical policies, and better incorporate multi-scalar, lived experiences of the urban into novel approaches for urban planning and research.

Acknowledgments

Profound thanks are extended to Jennifer Robinson and Christian Schmid for their invaluable comments on the drafts of this paper. I’m also indebted to Philip Harrison and Jennifer van den Bussche, among many others in and around Gauteng, for leading me to the fascinating places and people the article discusses, and to Vanessa Joos for her support from the very beginning. To Susie Cramer-Greenbaum and Alice Herzog-Frasier as well as the three anonymous referees from Urban Geography, thank you so much for your insight and expertise in reviewing this work.

Disclosure statement

All information included in the report was used with the full consent of study participants and interviewees.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The GCR roughly contains roughly 12.5 million people including the metropolitan centralities of the City of Johannesburg with its estimated 4.5 million residents, Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality with 3.2 million, and the City of Tshwane (Pretoria) with over 2.9 million residents. Mid-decade estimates StatsSA indicate growth from 12.4 million in Gauteng to 13.5 million, or 24% of the total population of South Africa. Population statics derived from the last South African National Census (StatsSA Statistics South Africa, Citation2011).

2. Johannesburg’s Planact office executive (pers.comm., 21 October 2014).

3. Provincial MEC Minister of Transit (pers.comm., 15 October 2014).

4. Gauteng City-Region Observatory executive (pers.comm., 20 January 2015).

5. Spatial planning professor and postdoc at the University of the Witwatersrand (pers.comm., 16 October 2014). They noted the peripheries as a space invisible to spatial planning, in part due to the challenges of the urban land market as well as higher pressure for government to solve problems near centralities.

6. City of Johannesburg Development Planning Department official (pers.comm., 26 June 2016) and Johannesburg City Manager official (pers.comm., 23 August 2016).

7. University of Johannesburg and 25-year ITMP collaborator (pers.comm., 23 October 2014) and JOSHCO affordable housing executive (pers.comm., 21 October 2014).

8. “Lettie” (pers.comms., 2016–2017), study participant in Soshanguve.

9. “Olga” (pers.comms., 2016–2017), study participant in Tembisa and Seabe.

10. Mome (pers.comms., 2015), study participant in Diepsloot.

11. Miss Vi (pers.comms., 2017), study participant in Lethlabile and Diepsloot.

12. Sticky Situations NGO executive (pers.comm., 1 May 2017).

References

- Arboleda, M. (2015). In the nature of the non-city: Expanded infrastructural networks and the political ecology of planetary Urbanization. Antipode, 48(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12175

- Ballard, R, & Rubin, M. (2017). A ‘marshall plan’ for human settlements: How mega projects became South Africa’s housing policy. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 95(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2017.0020

- Bonner, P, & Nieftagodien, N. (2008). Alexandra: A history. Wits University Press.

- Brenner, N, & Schmid, C. (2012). Planetary Urbanization. In M. Gandy (Ed.), Mobile Urbanism(pp. 161–162). Jovis.

- Butcher, S (2016). Infrastructures of property and debt: Making affordable housing, race and place in Johannesburg (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Minnesota.

- Caldeira, T. (2017). Peripheral Urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global South. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 35(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816658479

- Chapple, K, & Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2019). Transit-oriented displacement or community dividends? Understanding the effects of smarter growth on communities. MIT Press.

- Charlton, S (2013). State ambitions and peoples’ practices: An exploration of RDP housing in Johannesburg (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Sheffield.

- Charlton, S. (2014). Waste pickers/informal recyclers. In A Todes, C Wray, G Gotz, & P Harrison (Eds.), Changing space, Changing City (pp. 539–545). Wits University Press.

- Chaskalson, M (1986). The Road to Sharpeville, In African Studies Seminar Papers No. 199. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand, 1–50.

- CoT City of Tshwane. (2016). Regional spatial development framework. City of Tshwane. Region 1 and Region 2, Retrieved July 20, 2019, from http://www.tshwane.gov.za.

- Crankshaw, O, & Parnell, S. (2004). Johannesburg: Race, inequality, and urbanization. In J Gugler (Ed.), World Cities beyond the West: Globalisation, development and inequality (pp. 348–370). Cambridge University Press.

- Croese, S. (2017). International case studies of transit-oriented development – Corridor implementation. In P Harrison (Ed.), Spatial transformation through transit-oriented development in Johannesburg research report series. University of the Witwatersrand Press.

- Crush, J, Jeeves, A, & Yudelman, D. (1991). South Africa’s labour empire: A history of black migrancy to the mines. David Philip.

- Drakakis-Smith, D. (1992). Urban and regional change in Southern Africa. Routledge.

- Drummond, J. (1991). The demise of territorial Apartheid: Re-incorporating the Bantustans in a ‘New’ South Africa. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 82(5), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.1991.tb00797.x

- Fair, TDJ. (1975). Commuting fields in the metropolitan structure of the Witwatersrand. South African Geographer, 5(1), 7–15.

- Firth, A (2011). Community profile databases and GEOGRAPHICAL AREAS, Statistics South Africa National Census 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2019, from http://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/798013043.

- Gotz, G, Wray, C, & Mubiwa, B. (2014). The ‘thin oil of urbanization?’ Spatial change in Johannesburg and the Gauteng city-region. In A Todes, C Wray, G Gotz, & P Harrison (Eds.), Changing space, Changing City (pp. 42–62). Wits University Press.

- GSDF Gauteng Spatial Development Framework. (2013). Gauteng spatial development framework 2030, Gauteng Planning Division, Office of the Premier.

- Halvorsen, S. (2018). Decolonising territory: Dialogues with Latin American knowledges and grassroots strategies. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518777623

- Harber, A. (2011). Diepsloot. Johnathan Ball Publishers.

- Harrison, K. (2017). Transit corridors and the private sector: Incentives, regulations and the property market. In P Harrison (Ed.), Spatial transformation through transit-oriented development in Johannesburg research report series. University of the Witwatersrand Press.

- Harrison, P, & Zack, T. (2012). The power of mining: The fall of gold and rise of Johannesburg. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 30(4), 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2012.724869

- Hart, G. (2002). Disabling globalization. Places of power in post-apartheid South Africa. University of California Press.

- Hart, G. (2006). Denaturalizing dispossession: Critical ethnography in the age of resurgent imperialism. Antipode, 38(5), 977–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00489.x

- Hart, G. (2014). Rethinking the South African crisis: Nationalism, populism, hegemony. University of Georgia Press.

- Howe. (2017). Thinking through peripheries. Structural spatial inequality in Johannesburg (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). ETH Zurich.

- Howe. (2018). Paradigm Johannesburg: Control and insurgency in South African urban development. International Development Planning Review, 40(4), 349–369. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2018.15

- Howe, L B. (2021). Thinking through people: The potential of volunteered geographic information. Urban Studies, 004209802098225. January 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020982251

- Huchzermeyer, M, Karam, A, & Mania, M. (2014). Informal settlements. In A Todes, C Wray, G Gotz, & P Harrison (Eds.), Changing space, Changing City (pp. 154–175). Wits University Press.

- Katz, MB. (2015). What kind of problem is poverty? The archeology of an idea. In A Roy & E Shaw Crane (Eds.), Territories of poverty: Rethinking North and South (pp. 39–78). University of Georgia Press.

- Kihato, CW. (2013). Migrant women of Johannesburg: Everyday life in an in-between city. Wits University Press.

- Landau, LB. (2016). The means and meaning of interculturalism in Africa’s Urban age. In G Marconi & Ostanel (Eds.), The Intercultural City(pp. 65–78). I.B. Tauris.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991 [1974]. The production of space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Basil Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. (2008). Critique of everyday life (Vol. 3). Verso.

- Leitner, H, & Sheppard, E. (2018). Provincializing critical Urban theory: Extending the ecosystem of possibilities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12277

- Ligthelm, AA. (2008). The impact of shopping mall development on small township retailers. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 11(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v11i1.376

- Mabin, A (2013). The map of Gauteng: Evolution of a city-region in concept and plan, GCRO Occasional Paper 5, Gauteng City-Region Observatory, Johannesburg.

- Marcus, GE. (1995). Ethnography in/of the World system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review Anthropology, 24(95), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

- Mbembe, JA, & Nuttall, S. (2004). Writing the World from an African Metropolis. Public Culture, 16(3), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-347

- Monte Mór, RL. (2017). Extended Urbanization: Implications for urban and regional theory. In R Horn (Ed.), Emerging Urban spaces: A planetary perspective (pp. 201–216). Springer.

- Murray, C. (1987). Dispaced Urbanization: South Africa’s Rural Slums. African Affairs, 86(344), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097916

- Mushongera, D, Tseng, D, Kwenda, P, Benhura, M, Zikhali, P, & Ngwenya, P (2018). Poverty and inequality in the Gauteng City-Region, GCRO Occasional Paper 9, Gauteng City-Region Observatory, Johannesburg.

- Ogunyankin, GA. (2019). ‘The City of Our Dream’: Owambe Urbanism and low-income women’s resistance in Ibadan, Nigeria. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(3), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12732

- Parnell, S, & Robinson, J. (2012). Retheorizing cities from the Global South: Looking Beyond Neoliberalism. Urban Geography, 33(4), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.4.593

- Peberdy, S, Harrison, P, & Dinath, Y (2017). Uneven spaces: Core and periphery in the Gauteng City-Region, GCRO Occasional Paper 6, Gauteng City-Region Observatory, Johannesburg.

- Pieterse, E, & Simone, A. (2013). Rogue Urbanism: Emergent African cities. Jacana Media.

- Platzky, L, & Walker, C. (1985). The Surplus people: Forced removals in South Africa. Ravan Press.

- Rankin, K. (2011). Critical development studies and the praxis of planning. In N Brenner, P Marcuse, & M Mayer (Eds.), Cities for people not for profit (pp. 102–116). Routledge.

- Robinson, J. (2006). Ordinary cities. Between modernity and development. Routledge.

- Roy, A. (2008). The 21st-century Metropolis: New geographies of theory. Regional Studies, 43(6), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701809665

- Roy, A. (2010). Poverty capital: Microfinance and the making of development. Routledge.

- Roy, A. (2014). Worlding the south. Toward a post-colonial urban theory. In S Parnell & S Oldfield (Eds.), The Routledge handbook on cities of the Global South(pp. 9–20). Routledge.

- Roy, A. (2015). Introduction. In A Roy & E Shaw Crane (Eds.), Territories of Poverty: Rethinking North and South (pp. 1–38). University of Georgia Press.

- Roy, A, & Shaw Crane, E (eds.). (2015). Territories of Poverty: Rethinking North and South. University of Georgia Press.

- Rubin, M, & Parker, A (2017). Motherhood in Johannesburg: Mapping the experiences and moral geographies of women and their children in the city, GCRO Occasional Paper 11, Gauteng City-Region Observatory, Johannesburg.

- Schmid, C. (2014). Patterns and pathways of global urbanization: Towards comparative analysis. In N Brenner (Ed.), Implosions/Explosions: towards a study of planetary Urbanization (pp. 203–217). Jovis.

- Schmid, C, Karaman, O, Hanakata, N, Sawyer, L, Streule, M, Wong, KP, Kallenberger, P, & Kockelkorn, A. (2018). Towards a new vocabulary of urbanization processes: A comparative approach. Urban Studies, 55(1), 20–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017739750

- Simone, A. (2004a). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-407

- Simone, A (2004b) The invisible: Winterveld, South Africa. For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities. Durham: Duke University Press, 63–90.

- Simone, A, & Abouhani, A. (2005). Urban Africa: Changing contours of survival in the city. Unisa Press.

- Simone, A, & Pieterse, E. (2017). New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting dissonant times. Polity Press.

- Stanek, L. (2008). Space as Concrete abstraction. Hegel, Marx, and modern urbanism in Henri Lefebvre. In K Goonewardena, S Kipfer, R Milgrom, & C Schmid (Eds.), Space, difference, everyday life: Reading Henri Lefebvre (pp. 62–79). Routledge.

- StatsSA Statistics South Africa. (2011). Statistical release census 2011, Retrieved July 20, 2019, from http://www.statssa.gov.za.

- Thompson, DK. (2017). Scaling statelessness: Absent, present, former, and liminal States of Somali experience in South Africa. PoLAR Political & Legal Anthropology Review, 40(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/plar.12202

- Todes, A, Kok, P, Wentzel, M, Van Zyl, J, & Cross, C. (2008). Contemporary South African Urbanisation dynamics. Urban Forum, 21(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-010-9094-5

- Todes, A, & Robinson, J. (2019). Re-directing developers: New models of rental housing development to re-shape the post-apartheid city? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(2), 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19871069

- Topalovic, M. (2017). Palm Oil. Territories of extended urbanization. In S Cairns & T Devisari (Eds.), Future cities laboratory: Indicia01 (pp. 170–182). Lars Müller.

- Van Onselen, C. (1982). Studies in the social and economic history of the Witwatersrand 1886–1914. Longman.

- Wacquant, L. (2016). Revisiting territories of relegation: Class, ethnicity and state in the making of advanced marginality. Urban Studies, 53(6), 1077–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015613259

- Watts, M. (2001). Development ethnographies. Ethnography, 2(2), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661380122230939

- Whitehead, K. (2013). Race-class intersections as interactional resources in post-apartheid South Africa. Sage.

- Worden, N. (1994). The making of modern South Africa: Conquest, segregation and apartheid. Blackwell.

- Zack, T (2017). Johannesburg’s inner city: The Dubai of southern Africa, but all below the radar. The Conversation, 5 November https://theconversation.com/johannesburgs-inner-city-the-dubai-of-southern-africa-but-all-below-the-radar-86557