ABSTRACT

Cities need social infrastructure, places that support social connection in neighborhoods and across communities. In the face of austerity in many places, the provision of such infrastructures are under threat. To protect such infrastructures, it is important to have robust arguments for their provision, maintenance, and protection. Through a case study of a dispute about the appropriate use and provisioning of an everyday park located in London, UK, this article examines what social infrastructure is and why it matters. The dispute has brought to the surface a number of critical questions about how to fund and provide collective, public social life. It has also raised questions about what types of social and collective life should be valued. To examine the dispute a sixfold typology is developed to explore the different registers of sociality afforded by social infrastructure: co-presence, sociability and friendship, care and kinship, kinesthetic practices, and civic engagement.

1. Introduction

It is a typical late summer Saturday in Finsbury Park. In the morning 300 runners gathered for the weekly 5 km parkrun. Two dozen volunteers in hi-viz jackets helped support the two laps of the main roadway that loops the park. Joining the runners and walkers are plenty of dog-walkers, out before the park gets too busy. Also there early, sheltered in the middle of the park amongst the trees, is a regular yoga class. By lunchtime the tennis and basketball courts are packed. Young families are making full use of the adventure playground and picnic area next to the independent cafe and the small boating lake. As the afternoon unfolds families and groups of friends set up alfresco birthday parties on the main field in the southern part of the park. With a busy high street just through the main gates, the park is well used as a place to stop, eat and drink. These gatherings and activities extend well into the evening – until the floodlit athletics track is the only facility still in use. This is an everyday urban scene. Different groups of people – different kinds of bodies – all making use of a park for a whole range of uses. ()

In all sorts of ways Finsbury Park is an exemplary case for understanding contemporary parks in the UK. Situated in an economically and ethnically diverse part of North London,Footnote1 the park is a focal point for families, sports and fitness enthusiasts, and local residents, including many with no outdoor space of their own. The park has experienced a number of institutional transformations over the past decade. In the face of cuts from central government, the local authority that runs the park – Haringey Council – has developed a range of radical strategies to maintain and fund it. Some of these changes are not obvious to the general public. Parts of the park have been handed over to a sports trust run by local clubs and businesses. Others are more conspicuous. Haringey Council has pursued a number of strategies for generating revenue directly from the park. Finsbury park now hosts a number of large scale music events. Attracting crowds of up to 40,000 people, these raise significant sums for the upkeep of the park – as well as providing opportunities for quite spectacular kinds of social life. These changes have been controversial, creating conflict and contestation between the council, residents, and park users. Community groups have pushed back against the commercial use of the park, arguing that it undermines the very purpose of the park as a public space; objecting to how commercial events restrict free access to the park, and the nuisance and anti-social behavior surrounding these events.

To understand what is at stake in this dispute is useful to take a step back and ask, how conceptually should we be approaching places such as Finsbury Park? It is a public space, certainly; and this suggests certain issues are at stake. But it is much more than just a public space. It is also a place that affords and supports all kinds of social life. Finsbury Park is not only a public space, it is a key piece of social infrastructure for this part of North London. The dispute around the funding of Finsbury Park – and the commercialization of this – is a dispute about provisioning, funding, and maintenance of such social infrastructures. It is also a dispute about the kind of social infrastructure the park is; a dispute about what kinds of social life are permitted, sanctioned or celebrated. What is compelling about this case is that it is a well used park with at times complementary and other times conflicting uses. To understand what is at stake it is critical to be able to recognize the different social lives of the park. The dispute around Finsbury Park’s funding and use might easily be subsumed into existing debates around the commercialization, privatization, even festivalisation of public space. Our central contention is that it is essential to think carefully about the different registers that make up the social in social infrastructure – and by association the social in public space – to properly understand why access to a well-provisioned and maintained park matters; and thus what is at stake in disputes such as that at Finsbury Park.

Through the case study of Finsbury Park, we aim, then, to demonstrate how thinking about public space as social infrastructure enhances understandings of the public life of cities. For readers who like to know where they are going, here is the plan. In section two we situate the concept of social infrastructure in the literature on infrastructure and on public space, we then describe – drawing on ethnographic and survey observations – the kind of space Finsbury Park is in section three. Section four develops a sixfold typology that grapples with the different registers of social life to be found in the park, and in turn how the “social” in “social infrastructure” might be analyzed. Finally, in section five, the discussion turns directly to the dispute. Drawing on the concept of social infrastructure and the different socialities it can support, it highlights the potential of what public parks can be, but also the challenges there are in realizing that potential. If we want to make cities better places to live, understanding how to provide social infrastructure is a key terrain of inquiry.

2. Social infrastructure, public facilities, and the collective life of cities

Looking at public spaces in cities there is a strong temptation to see them through the frame of the political: they are places where people meet and recognize strangers; places where people make claims; spaces where people are excluded, and they fight back from that exclusion; spaces where people can participate in democratic life (Iveson, Citation2007; Koch & Latham, Citation2012; Staeheli & Mitchell, Citation2007). Of course public space is about these things. But public – and quasi-public – spaces also form the backdrop to people’s – and neighborhood’s – ordinary life (Amin, Citation2008; Sennett, Citation2017; Watson, Citation2006). Sidewalks, corner-shops, and buses. Hair-salons, barbers, and markets. Swimming pools, skate-parks and gyms. Church halls, schools, and community centers. If you look, most cities have an enormous variety of public spaces. Spaces of public transport and mobility. Spaces for collective experience – and consumption. Spaces for leisure, sport and fitness. These spaces matter. As Klinenberg (Citation2018) argues, these kinds of spaces can be understood as social infrastructure – spaces that support and create the opportunities for social connection (see also: Latham and Layton, Citation2019b). In all kinds of ways social infrastructures make life in cities liveable. Liveable in that they create affordances for – and make available – a range of essential services.Footnote2 And liveable in an expanded sense of helping make life better. This matters not only in a quality of life sense, but can also have profound implications for people’s life chances, well-being, physical and mental health (Klinenberg, Citation2002, Citation2015).

To talk about social infrastructure then, is to talk in some way about infrastructure; a term that has developed a high valence in urban geography. Building on the work of Graham and Marvin (Citation1995, Citation2001), critical attention has been paid to the splintered landscape of infrastructural provision where in many cities certain groups are systematically excluded from water, power, and sanitation (McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017; Rogers & O’Neill, Citation2012). Here the focus is often on the ways that infrastructural networks pull resources and nature into a highly uneven political economy (Heynen et al., Citation2006; Wakefield, Citation2018). Infrastructure is also a term that many have found attractive for its theoretical and metaphorical resonances (Anand et al., Citation2018; Gandy, Citation2014; Larkin, Citation2013); for the ways in which it can “mediate certain recurrent binaries in critical thought – macro and micro, object and agent, human and non-human” (Tonkiss, Citation2015, p. 384). Infrastructure has proven to be a fertile concept to think with. But amongst all this attention to infrastructure as vehicles of social power, it should be remembered that the term is interesting because it orients attention toward a whole range of objects, systems, and institutions that allow things to happen. This is to go back to the most basic definition of infrastructure, that it is the in-between structures and systems that afford and support action. From a social theoretic perspective the key issue is recognizing that infrastructure is not only interesting as a noun – as the pipes, cables, switches, and surfaces – but also interesting as a verb or adverb – as something that modifies, supports and exists in relation to other activities. That is to say infrastructure is relational (Star, Citation1999).

Put another way, infrastructure is useful precisely because it is about the dynamics of facilitating activity. Thinking with infrastructure – its provision, scope, accessibility, maintenance and durability – can help explore why certain cities are more liveable than others, why certain cities have lower mortality rates, higher rates of reported happiness, and more equitable distribution of resources (Amin, Citation2006; Peter Hall, Citation2014; Talen, Citation2019). Drawing on Sen (Citation1999, Citation2009), infrastructure can be framed as a way to build capacity into a city, and increase people’s freedom to pursue activities. This capacity could well be about supporting reliable electrical power, clean running water, hygienic sewage systems, and fast telecommunications, but it can also be about supporting a whole world of social activity. By alighting on the term social infrastructure, Klinenberg (Citation2018) found a way to talk about the background structures and systems of cities that can encourage sociality. Where it can be asked: What are the infrastructures that support social connection? What kinds of infrastructures can facilitate the pursuit of shared interests? How could infrastructures encourage a collective public culture?

With the term social infrastructure we are thinking about the networks of spaces, facilities, institutions, and groups that create affordances for social connection. Others in urban geography and urban studies have considered the sociality of infrastructure (Amin, Citation2014; Graham & McFarlane, Citation2015; Silver & McFarlane, Citation2019) – recognizing that a lot of human work can go into making infrastructure function (Cesafasky, Citation2017), or in some cases even replaces and substitutes for more typical hard infrastructures (Simone, Citation2004). Fewer have drawn attention to the infrastructures that facilitate sociality. Writers like Hall (Citation2020a, Citation2020b), Penny (Citation2019), and Shaw (Citation2019), have recognized the value of social infrastructures, and shown how in the context of austerity in the UK, places like libraries, schools, and parks are under increased financial pressure. Others have used the term social infrastructure to make links between literatures on infrastructure and those on social reproduction and labor precarity (Cowan, Citation2019; Nethercote, Citation2017; Strauss, Citation2019). Adding to this important work we see social infrastructure as being a way to explore and understand the ways that collective social life can be achieved in cities.

In particular there are two key dimensions of social infrastructure that are useful to think with. First, is social infrastructure’s emphasis on the facilitation of social connection which foregrounds the breadth, depth and textures of different kinds of sociality that can take place in cities – and parks like Finsbury Park. In much of urban geography and urban studies the archetypal kind of social contact is a form of fleeting encounter between strangers (Koch & Miles, Citation2020; Wilson, Citation2017). With social infrastructure it is possible to recognize the diverse types of sociality that are supported in urban environments. This can be the encounter of unknown others as found in markets, buses, or parks. However in cities it is also possible to find relations of dependency, cooperation, community, and solidarity. Moreover, the concept is a reminder that the values we might want to encourage in urban environments – conviviality and community (Neal et al., Citation2019); encounter with strangers and refuge (Amin, Citation2012; Anderson, Citation2011); a public ethos (Sennett, Citation2017); a democratic mindedness (Barnett, Citation2014; Parkinson, Citation2012); and inclusiveness (Staeheli et al., Citation2009) – often flow from the connections people are able to make in and around particular spaces, places, and facilities (Klinenberg, Citation2018; Talen, Citation2019). Or, to borrow the language of Amin (Citation2008), social infrastructure can help to think concretely about the ways that “social surplus” can be realized.

Second and following on from this, the public landscapes where much of this social life takes place, is afforded, supported, and facilitated by concrete spaces and facilities. And the specific texture of sociality afforded, depends on the qualities of the social infrastructure. The social life of a football pitch in a park, will no doubt be quite different to the social life that is supported by a church. Yet both serve important functions to the people that use them. Or, as Wilste (Citation2007) explores with swimming pools in the context of racism in American cities, two functionally identical rectangular bodies of water can have radically different social outcomes depending on their funding, management, regulation, and cultural norms practiced around them. Social infrastructure orients us to the materials that support social life. As seen during the Covid-19 pandemic, it becomes so much harder to maintain and nurture the social connections that enable urban life to flourish when social infrastructure functionally vanishes. Workarounds can be achieved. But they are often a poor substitute for a robust, well maintained, open and accessible set of spaces where people can go to gather, play, eat, drink, read, rest, relax, and spectate together.

With its attention to material provision, and diverse social outcomes, the concept of social infrastructure can enable new thinking about parks like Finsbury. The dispute – introduced at the start – around how Finsbury Park is being used for events and festivals, is in many ways a dispute about the kind of social infrastructure the park is, the kinds of social life it should be supporting, and how it should be supporting it. Rather than framing this singularly as a dispute about public space, working with the concept of social infrastructure we can begin unpacking the different dimensions of sociality to be found in the park – and why some have become the focus of conflict and contestation and others not.

3. The Finsbury Park case and how we studied it

Parks are surprisingly dynamic institutions. Originally conceived – in Northern Europe and North America at least – as spaces to contain both an unruly nature and unruly urban populations, contemporary urban parks take on a remarkable range of form and functions (Cranz, Citation1982; Low et al., Citation2005; Rosenzweig & Blackmar, Citation1992). Parks that support rest, repose and engagement with nature still exist, but so too do parks predominantly dedicated to sports and fitness or children’s play. Some parks – like Hyde Park in London – lean into their heritage as a site of public address, others have become open spaces suited to events such as Fashion Week (Prospect Park, Brooklyn) or the Fringe Festival (Adelaide). Parks are also often seen as a key way to introduce biodiversity into urban areas (Lachmund, Citation2013). The cultural imaginary of the function and form of parks varies from place to place. In some places the forested nature of parks is prioritized, in others there is a tradition for smaller neighborhood spaces, and – depending on physical geography – a park’s ability to incorporate the coast, mountainous areas, or snow can be important. When we begin to think about these park spaces in general – and as social infrastructure in particular – what can feel like known and stable institutions, can be seen as morphologically and socially diverse.

Before turning directly to the question of what type of urban park Finsbury is, it is necessary to take a short detour to set out the methods through which the empirical material presented here was gathered. To understand the social life of the park, a series of structured observations were undertaken during the summer of 2018 – May through September – drawing on the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC) method (McKenzie et al., Citation2006). This involved taking a set walking route around the park noting the different levels of activity in different areas of the park. These observations were done periodically throughout the day, on different days of the week. These survey observations directed follow-up visits for longer periods of ethnographic observation of the busier areas and times – such as at the basketball courts, and parkrun. In addition, interviews were undertaken with key stakeholders (volunteers, sports and fitness participants, management staff and members of the public), this was designed to provide more detail about how the park was used and managed.

Through our engagement with the park, it became clear that the festival licensing dispute would be a productive way to further explore the park as a piece of social infrastructure. This meant it was necessary to develop a second strand of inquiry that followed the dispute around the festivals. This involved a systematic review of the debate as it was happening in public. This included: how the issue was covered in local and national newspapers, as well as on social media;Footnote3 documents produced by the council relating to the park (council minutes, and minutes from the Finsbury Park Stakeholder Group meetings); and a comprehensive review of the documents produced for the court proceedings in 2017, as well as the licensing review in 2018. These consolidated the “for” and “against” of the dispute from key actors including Haringey Council, Live Nation/Festival Republic, the Open Spaces Society and the Friends of Finsbury Park. We also attended regular Friends of Finsbury Park meetings – as a way to engage with how local community groups were responding to the dispute.

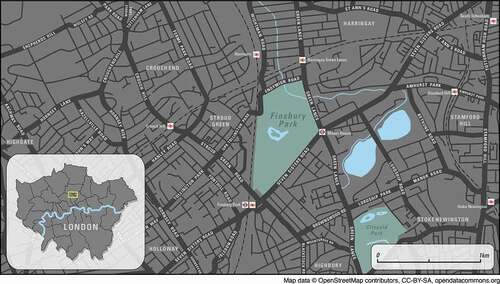

Through this research, Finsbury Park revealed itself as a popular place that supports multiple – albeit sometimes contrasting – uses. (see , the figure with all the different activity)

Figure 2. A) Map extracted from Haringey Council (Citation2019) Introducing: Finsbury Park [pdf leaflet]. B) Photo of basketball courts courtesy of Sean Fitzimmons. C) Photo of Finsbury Park bench licensed under creative commons from “spiraltri3e” www.flickr.com. D) Photo of footballers “12. They are Here” licensed under creative commons, installation at Furtherfield Gallery, photographer: Annalisa Sonzogni. E) Photo of perimeter fences, authors own. F) Photo of field with sign, authors own. G) Photo of major event, authors own

![Figure 2. A) Map extracted from Haringey Council (Citation2019) Introducing: Finsbury Park [pdf leaflet]. B) Photo of basketball courts courtesy of Sean Fitzimmons. C) Photo of Finsbury Park bench licensed under creative commons from “spiraltri3e” www.flickr.com. D) Photo of footballers “12. They are Here” licensed under creative commons, installation at Furtherfield Gallery, photographer: Annalisa Sonzogni. E) Photo of perimeter fences, authors own. F) Photo of field with sign, authors own. G) Photo of major event, authors own](/cms/asset/76c5317f-9c4f-479f-8b57-b4fde744fa6c/rurb_a_1934631_f0002_oc.jpg)

Originally laid out in the mid-19th century the park has many features characteristic of Victorian era English city parks: gated entrances, a rose garden, boating lake, pavilions, a “tree-trail” as well as wide tree-lined boulevards. As a place for respite and gentle leisure, these kinds of uses can still be observed today. The rose garden (the McKenzie Gardens) is used as a place to sit, read and picnic. However it is also used as a place for exercise – each weekend “British Military Fitness” will use the gardens as a station for exercise. The “tree-trail” with its cultivated horticultural diversity in the North Eastern part of the park is popular with young adults and families for activities at the weekend – cricket, football, frisbee, rounders. And throughout the summer, every Saturday, a volleyball court is set up amongst the trees. Also on the weekend underneath the “yoga tree” (a hornbeam that’s part of the “tree-trail”), regular yoga classes take place. The wide boulevard that loops the park is rarely seen without at least one of the following: dog walkers, joggers, cyclists, people on scooters, skateboards and roller-blades. Just off the main boulevard on the eastern edge of the park, organized sports teams (football, netball, touch rugby) set up to practice on Saturday and Sunday afternoons – and while it’s light enough, during evenings through the week. This formal layout continues to support all kinds of social activity.

The park hasn’t simply remained static in its 150 year history.Footnote4 It has been renovated and redesigned a number of times. Most recently, after a £4.9 million heritage Lottery grant between 2001 and 2006 the whole park was refurbished; including the addition of a number of new elements, most notably a cafe, toilets, and adventure playground. In many ways the cafe is the center of the social life of the park; independently run, it’s a popular place for breakfasts on the weekend, and ice creams throughout the day and after school. When organizing interviews with people involved with the park, it was often suggested as the most sensible meeting place for a conversation. Nor is it uncommon to find local MP, and former leader of the Labor Party, Jeremy Corbyn, having a coffee there and taking time to speak with members of the public. The adventure playground – at times the noisiest part of the park – is often busy, and makes for “an easy place to bring the kids”.

An important step in the evolution of the park has been the introduction of different sports facilities dotted throughout. Along the Western edge there is: a skate park, tennis courts, netball and basketball courts. At the Northern end, a baseball diamond and two outdoor gyms. And in the center there’s a bowling green, which is adjacent to the gated athletics track (with sandpit and throwing cage) and American Football field. Of these facilities, the most regularly well-used are the basketball courts. Throughout the observations, it was rare to find fewer than 10 people – often men, and often from Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds – regardless of time or day of the week, using the courts: practicing, training, and often just hanging-out. As one of the players explained, the courts are “the place to be – there’s always people here”. While on occasion the athletics track was hired to local schools for their sports days.

The largest physical change to the park throughout the year, is the construction of a perimeter fence that encompasses a little under 50% of the park. This is so that the park can be set up as a festival venue. Although porous, with open gates and walkways, the fence does disrupt activity in the Southern half of the park. It restricts the way the main field by the Finsbury Gate can be used for walking, jogging, playing, birthday parties, picnicking, and rounders. When the park is being used for events, some 40,000 people visit the park to watch live music: at Community Festival for indie rock, Wireless for grime, hip-hop and R&B, and for one off gigs (in 2018 this included: Liam Gallagher and Queens of the Stone Age). In 2018, a year prior to headlining Glastonbury Festival, Stormzy – the London grime artist – headlined Wireless festival in the park. As a showcase of the UK grime scene, Wireless has become a space for predominantly young, Black and Minority Ethnic communities to celebrate a marginalized culture in a prominent, public, location (Hancox, Citation2018).

The park is dynamic and evolving. It supports the kinds of social life that might traditionally be expected in parks. But also, in many ways, challenges preconceptions around what a park is for, how it might be used, and who it is for. With so much activity going on it pushed us to re-think the language we use to make sense of parks, but also to think what the social in “social infrastructure” means and is made up of. Festivals such as Wireless have been at the center of the dispute about what Finsbury Park is for, and how the facilities within it should be provisioned. To be able to navigate this dispute, and before we can properly engage with the arguments around the park, it is necessary to think more carefully about how the social life observed can be made sense of.

4. What is the social in social infrastructure?

Much of the literature on the social lives of parks and public spaces focuses on the ways that they can be spaces of encounter and conviviality across lines of gender, race and class (Neal et al., Citation2015; Low et al., Citation2005; Carr et al., Citation1992). Or have evolved to become venues for social life (Carmona, Citation2010). Others have considered the way that certain public spaces can facilitate play and enjoyable engagement (Jones, Citation2014; Stephens, Citation2007). However as Koch and Miles (Citation2020) neatly summarize: “Encounters with unknown others are widely regarded as a defining feature of the urban experience.”

Reflecting on the activity observed in Finsbury Park – encounter certainly captures some of the activity to be found in the park. For example, many of the people in the park are just walking and watching other people, as they play tennis and basketball, or slack-line. This speaks to the background sense of trust found there, and the complex sets of conventions, norms and material provision that facilitates the co-presence of unknown others (Amin, Citation2008; Goffman, Citation1971; Lofland, Citation1973). Thinking with this idea of co-presence it’s possible to see the way the park actively encourages and invites people in, to spend time in the proximity of others (Carmona, Citation2010; Gehl, Citation2011) – through the provision of diverse sports facilities, public restrooms, and well-maintained grounds. As Neal et al. (Citation2019) argue such spaces create the opportunity for conviviality to be practiced. The capacity for the park to support comfortable co-presence has an ethical dimension. Although an encounter with unknown others is not sufficient for achieving inclusion (Valentine, Citation2008), it can certainly suggest tolerance, and recognition of shared participation in an everyday urban scene (Amin, Citation2012; Elkin, Citation2016; Wilson, Citation2017).

Yet the social life of the park is not reducible to co-presence and encounter. It was evident that some of the social life supported by the park was thicker and more durable. Take the basketball courts. Although some of the basketball players will turn up on their own to play with whoever happens to be there. Through interviews it became apparent that often friends would arrange to meet at the courts – an ideal free activity that could be done together. Moreover people that started out as strangers, over a period of time became acquaintances and friends. For these young Black and Minority Ethnic men, the basketball courts were an important site of sociability. More than being a site where they could “encounter” other people, the courts were a place where they could share an activity, hang-out, and play together – sharing time and space (Bunnell et al., Citation2012; Vincent et al., Citation2018). These relations of friendship and sociability are an important dimension of the social life of cities (Klinenberg, Citation2012; Pahl, Citation2000; Wellman, Citation1979) – and one that is well supported by the kinds of activity facilitated by parks.

When thinking about the more durable kinds of social ties that are maintained and practiced in parks, it was also clear that Finsbury supported a range of intimate relations of care and mutual dependence. This is a clear way to make sense of how the families made use of the adventure playground. It was an engaging and safe space for parents to spend quality time with their children. Moreover it was clear (because of the banners on trees, balloons, and presents) that some of the picnics observed were actually birthday parties. Family events taken to the park as an open accommodating space. It’s important not to reduce relations of care and mutual dependence to family alone, and to recognize that the burden of this work often falls disproportionately to women (Hall, Citation2020b). For many – particularly in cities – the line between kinship and friendship has become blurry (Roseneil & Budgeon, Citation2004; Sandercock, Citation2003; Weeks et al., Citation2001).Footnote5 Talking with the participants in the yoga group, and the volunteers in the parkrun, there was a clear sense that their activity involved an ethos of care. By taking part in a shared activity, individuals were able to develop a loose sense of kinship through practices of sharing and commonality (Hall, Citation2019; Power & Williams, Citation2020; Sennett, Citation2012).

Spending time in Finsbury Park, it became apparent that the social life being observed was entangled with a whole range of sporting practices: walking, cycling, scooting, running, jumping, balancing and stretching. In order to be able to make sense of the tennis being played, the basketball and volleyball games, and the multiple personal trainers – it was necessary to recognize the importance of the kinesthetic activity at hand (Latham and Layton, 2019). As writers like McNeill (Citation1997), Ehrenreich (Citation2008), and Sebanz et al. (Citation2006) have highlighted there is a particular kind of sociality to shared physical activity. Part of the reason the “British Military Fitness” exercise groups are so popular – and regularly well-attended – is that a sense of togetherness is formed in the midst of shared endeavor. parkrun, is another key example. Every Saturday morning 300 or more runners attend Finsbury Park to do their 5 km run. Taking part in this activity with so many other people each week, is an intensely physical form of sociality; a being with created through shared movement. Taking part in sport and physical activity is also a good excuse for spending time with friends. And for the solo-exercisers in the park, it is possible to see how their activity brings them into proximity with others. This can potentially create time and space for co-presence; even if there is no direct social interaction, there is a social dimension to being amongst other people with fellow exercisers (Hitchings & Latham, Citation2017; Krenichyn, Citation2006; Middleton, Citation2018). It is necessary to take people’s amateur sport and fitness interests seriously to understand the social life of Finsbury.

It was clear that this park was also a space of revelry and exuberant fun. Foremost here, to make sense of the social phenomena that are the major festivals in the park, it is necessary to recognize the sociality of crowds. Crowds and crowding don’t simply magnify an experience, they can also transform them. The collective massing together of people – that happens with Wireless, Community Festival, and the major gigs – creates a sense of liminality where the normal rules and conventions of ordinary life no longer apply. Part of what makes these festivals work is their exceptionality. The collective and carnivalesque can also be found on much smaller scales. Finsbury Park is used for smaller events – funfairs and parties. In 2014 the park was used to celebrate the 60th Birthday of London’s iconic Routemaster bus. During September of the observations, the park was used for a “Rough Runner” event – an obstacle course set around the park. Part of the fun of the event was the out-of-the-ordinary nature of it, a series of bouncy castle obstacles for adults in the middle of a park. This was followed two weeks later by the Cancer Research UK “Race for Life”, a fun run that encourages pink fancy dress to raise money for a good cause. The social life of these events is in their collective and spectacular form.

The more we looked at the social life of the park, the more we found people working in the background making things happen. One of the examples not yet mentioned – Pedal Power – a cycling club for those with learning difficulties, is a great club to have in the park. Yet it has taken the work of the organization – and the volunteers who drive it – to raise money and storage for the specialist bikes, find locations where it can happen, and encourage people to take part. This is a register of social life that is to do with volunteering, community organizing, and political campaigning (Holston, Citation2008; Stenning, Citation2020; Whitten, Citation2019). In Finsbury Park, one of the key actors behind the scenes is the Finsbury Park Sports Partnership – the trust that owns and looks after some of the key sports facilities. When they took over the management of the Athletics grounds in 2012, they were able to raise money to get the track re-laid and the gym refurbished – making it a facility the park could be proud of. Although this kind of activity can often simply be thought of as “political” activity – it is also social; closely related to the kind of social capital talked about by Putnam (Citation2000) and others (Cento Bull & Jones, Citation2006; Portes, Citation1998). Civic engagement can also be seen as akin to the idea of forming publics – groups of people concerned with a material problem that they want to have addressed (Marres, Citation2012; Warner, Citation2002). This idea of civic engagement is about coming together with others to make something happen (Hou, Citation2010; Sharkey, Citation2018).

Reflecting on all this activity in Finsbury Park, it is clear that the social in social infrastructure covers a diverse range of social connections. Following from this, it is analytically important to differentiate the registers of the social that social infrastructures support. For all its strengths, existing work on social infrastructure and public life has glossed over how this differentiation should best be conceptualized, focussing on either the dynamics of encounter with strangers or on the production of social capital. The social life of cities is not reducible to just these dimensions. Through our observations of Finsbury Park it is possible to sketch-out a more differentiated analytical typology of registers of social life that social infrastructures like public parks support. These are: co-presence; sociability and friendship; care and kinship; kinesthetic practices; carnivalesque and collective experience; and civic engagement (see ). This is a typology for exploring the different kinds of social life that social infrastructure can support. As summarized in , there is a diverse body of social research that examines each of these different registers.

Table 1. Six registers of sociality

5. Dilemmas of provisioning in times of austerity: a park in material transformation

This typology is all well and good, but how does it relate to the dispute around the funding and usage of Finsbury Park? To recall. The past decade has seen an expansion of commercial festivals in the park. Festivals that have meant that large areas are unavailable through the summer – but which also create quite spectacular forms of social life for those attending and help fund the facilities and upkeep of the park. In response, community groups have protested these festivals, going as far to take the local authority to court. Working through the details of this dispute, in this section, we argue that what is at stake is not a straightforward erosion of the public qualities of Finsbury Park, but rather something more ambiguous. This becomes apparent when the distinctive registers of social life that animate the park are examined; the registers that give meaning and value to the diverse collection of people who use it. This is what the typology is for.

From 2010 Finsbury Park faced dramatic cuts to its funding. As central government aimed to reduce spending in response to the financial stresses of the Great Recession, local authorities were forced to carry a disproportionate burden – with funding being squeezed by almost 60% between 2010 and 2020.Footnote6 This has put local authorities in a difficult situation. They have a statutory obligation to provide a range of services (things like adult social care, schools, waste collection) whilst other services – that many citizens feel are essential – do not have this protection. Parks and recreational facilities are an example of this. As a result the money available to invest, maintain, and staff parks across the UK has been severely limited. To address this shortfall, local authorities have experimented with novel ways to both save money and generate revenue. Innovations have included transferring the management of public facilities to non-governmental bodies (such as charitable trusts, or social enterprises), selling public assets, reducing the hours certain facilities are available (reduced library services for example), and – central to the transformations at Finsbury – looking to events, including music festivals in parks, to generate income.

In the case of Finsbury Park, Haringey Council has by some measures been wildly successful. Formed in 2012, the Finsbury Park Sports Partnership has raised over £1 million to refurbish the Park’s running track and gym. And, with the introduction of the Outdoor Events Policy in 2014, Finsbury Park now regularly hosts events of tens of thousands of people in the park during the summer – generating over £1 million each year. It is the extension of the festivals that has been the source of controversy. A coalition of residents have built a campaign protesting the use of the park for major events including festivals. Their key concerns have been the level of disruption these events cause local residents, and how they limit access to the park during the summer. Their campaign – led by the Friends of Finsbury ParkFootnote7 – has gone as far to take Haringey to the High Court over their events policy (The Friends of Finsbury Park v Haringey Council, Citation2017); a case which they ultimately lost. In their view the council’s efforts to save the park have in fact eroded its viability as a properly public space.

If the point of a park is to provide green space and relaxation away from the hustle of city life, then the encroachment of festivals is clearly an erosion to the qualities of that space. The major events involve long periods – in some cases several weeks – where 12 foot high perimeter fences close off a little under 50% of the park.Footnote8 As well as these physical fixtures, the noise of the festivals makes it difficult to use the parts of the park that remain open – and is a noisy disturbance into the night for local residents. The festivals also spill out into the surrounding neighborhood as attendees come and go; littering, urinating, shouting, and drinking. Beyond these practical concerns, the campaign against the festivals has also been explicitly concerned with a more abstract idea of public-ness. These concerns have centered around the “over commercialisation” of public parks, and the way that these events restrict the access of the general public to the space of the park (FoFP, Citation2016). These restrictions it is argued prevent free use of the park, and severely limit people’s ability to sit and enjoy the peace and quiet a park can afford. This is certainly true. But in many ways it reduces the public-ness of the park to a single dimension. Using the concept of social infrastructure and the social registers they support, it is possible to think about the multiple ways a space like Finsbury Park is social – and public – even within the context of Haringey’s events policy.

Starting with the festivals themselves, their multiple social and public dimensions can be recognized when thinking through the breadth of socialities that a park is able to support. In all sorts of ways these contemporary music festivals can be seen as examples of carnival and collective experience. As mentioned above Wireless in particular is important as a publicly visible opportunity to celebrate the music of hip-hop, grime, and R&B – music emerging from BAME communities (Hancox, Citation2018; White, Citation2017, Citation2020), and which is rarely given a public stage in the middle of a busy city like London. It is also important to recognize the ways that the events have become financially entangled with the other forms of social life found in the park. Here the basketball courts are a prime example. In 2015 new courts were laid that have developed a reputation as some of the best courts in North London. Providing a high quality resource which is especially popular with young BAME men being social in a profoundly kinesthetic register, which also supports a great deal of sociability and friendship. These courts were funded from the money raised by the music festivals.

Other areas of the park have also experienced this increase in quality provisioning. The tennis courts have been resurfaced and floodlights installed, and a new outdoor calisthenics gym has been built, further increasing the opportunity for kinesthetic sociality. High-capacity bins have been introduced and the rose garden has been refurbished; these features operate in the background allowing more people to be co-present comfortably. An adventure playground has been re-constructed – popular with children and families, supporting care and kinship. Grant funding has also been increased, one use of which was to support the park’s 150th birthday celebrations. Here people came together to celebrate the park’s history and continued use with talks, music, and family events – an example of civic engagement. In all sorts of ways the capacity of the park to support social life has been improved through the investments that have been made as a result of the commercial success of the music festivals.

At the same time, it is necessary to recognize that this increase in funding has raised important questions around equity and distribution. And, it is important to ask: How much should festivals be allowed to impinge on the more routine use of the park? And what the parameters of that disruption should look like? The local residents have valid concerns about the extent of the park that is restricted to the non-festival-going public throughout the summer. How decisions about these logistical arrangements get made is important. As is the kind and extent of input citizens are able to have. It is also necessary to reflect on how and where the money raised in the park gets spent and invested. Finsbury Park has benefited from the money that has been raised by the festivals and invested in the park; yet other parks in the borough of Haringey have not been so fortunate. Those parks have experienced similar levels of funding cuts, but not been able to compensate for that income with events. This problem has been amplified by the outcome of the Friends of Finsbury Park’s unsuccessful High Court case against Haringey, that led to a legal clarification whereby all money raised in Finsbury Park has to be spent in Finsbury Park. The other parks in the borough of Haringey will not be able to be invested in and maintained to anything like the same level that Finsbury is.

Central to this dispute is that parks need to be funded. In the face of austerity it is not clear how this is best done. Also at stake is the shifting social life of parks – in Finsbury Park different registers of sociality have come into conflict. On the one hand, the park’s role as a site of respite – a place of quiet co-presence and relaxed sociability and friendship – is disrupted each year by the music festivals hosted there. On the other hand, Wireless itself is a significant site of carnival and collective experience for communities that are otherwise not always included in the life of parks. In addition, the money generated through hosting the festivals has been invested in a whole range of high quality facilities – such as the basketball courts and outdoor calisthenics gym already mentioned – but also the resurfaced netball and volleyball courts, and improved lighting, all of which invites popular forms of kinesthetic sociability. Again, these additions are supporting people that might not otherwise feel comfortable or provided for in the park; the basketball courts popular with young BAME men, and the lighting to ensure areas of the park are safe after dark. In many ways the park has become more inclusive, more welcoming, more a site for care and kinship, and more used as a result of the influx of festival funding. The underlying tension is that Haringey and the surrounding neighborhoods have ended up with a better park – but one that’s funding model at times amplifies its public-ness and at others times dampens it. Finsbury Park demonstrates what can be achieved when a park is well funded and cared for. But also highlights the tensions and conflict that can occur when a local authority has to look to temporary festivalisation to fund a prominent and valued public space.

6. Conclusion: why social infrastructure matters

Social infrastructure is fundamental for creating inclusive, socially just, and lively cities. To argue for social infrastructure, it is critical to appreciate the different registers of sociality that such infrastructures support. We need – and this has been a central argument of this article – a developed analytical language to engage with what the “social”, in “social infrastructure” is. Looking at an urban public park, we should not take it as self-evident what is going on in these places. Urban public parks are used in a diverse range of ways depending on the facilities they contain, the neighborhoods they are in, and the people that use them. To understand social infrastructure in general, and Finsbury Park in particular, we need to understand what activity infrastructure supports. This involves approaching infrastructure from a slightly different angle to how urban studies often analyses it. Infrastructures tend to be approached as vehicles of power – from which people are systematically excluded or which entrenches inequalities (Amin, Citation2013; Graham & Marvin, Citation2001; McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017). Drawing on the language of Sen (Citation1999, Citation2009), the provision of social infrastructure can be seen as fundamentally about building the capacity of certain environments; increasing people’s freedom to gather, be social, and undertake particular activities. Social infrastructures only function as social infrastructures if they are expanding such capacities. Still, if social infrastructures are by definition a public and social good, their provision is not guaranteed. Nor are the different social lives they afford necessarily harmonious and uncontested. As seen with the case study here, it is precisely disagreements about how social infrastructure should be provided, and conflicts over appropriate uses of social infrastructure, that allow us to see what is at stake in its provision.

The controversies in Finsbury Park have been sparked by the policies of austerity. Haringey Council has looked to novel – and controversial – ways of replacing lost funding. It would be easy to see this as the erosion and degradation of the public life of Finsbury Park – and indeed this is one of the arguments that has been made about the “over commercialisation” of the park. The public life of a city is rarely clear cut. A park like Finsbury plays multiple roles in the social life of its neighborhood and wider city – from being a space of rest and relaxation, through supporting multiple sporting communities, to being a place to spend a day with the family, and yes, even as a site for music festivals. These different roles are complicated and by no means harmonious. Each of the registers of sociality that Finsbury Park supports requires the provisioning and maintenance of surfaces, lighting, water, greenkeeping, gardening, storage. Following the different registers of sociality in the park highlights the ways that the influx of funding has been invested to increase the capacity of the park to support a diverse public social life, including for a number of otherwise marginalized groups. This is not an argument for unchecked commercialization of parks. Rather, this is an argument to recognize what substantial investment in a park can achieve – particularly investment directed toward communities that might not otherwise find a home in the park. Moreover it is an argument that the public social life of a park is dynamic and evolving, and rests upon robust material provisioning. And, it is a call to study the dilemmas of provision that austerity creates.

Social infrastructures within cities are messy, ambivalent, imperfect. When we study such infrastructures we need to recognize that. Parks can be extraordinary pieces of social infrastructure. Well designed and maintained public parks support the capacity and freedom to gather. Making it easier to be co-present. Allowing people to be friendly and sociable. Configuring spaces in such a way that they support care and kinship. Curating spaces that encourage all kinds of bodies to be kinesthetically active. Creating time and space for people to collectively experience the carnivalesque. Providing the resources for people to engage civically. It is important to be able to acknowledge this messiness. If we want to help make better social infrastructures in our cities – and better public spaces – we should not let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone who gave up their time to be interviewed for the research presented in this article. Thanks also to everyone that contributed to the session we hosted at the AAG 2019 in Washington D.C. which helped us to develop our ideas on the topic of social infrastructure. Further we would like to thank the editorial input from Susan Moore and the other editors at Urban Geography for guiding us through the peer-review process. The comments of the two anonymous reviewers really helped us to sharpen the structure and focus of the article. A big thanks also to the students of the “Public Space and the City” masters module at UCL, who came on site visits to Finsbury Park and asked us probing questions about our research on social infrastructure and the park. And finally, Jack would like to acknowledge the funding provided by the ESRC award no. 1622384.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. According to Haringey Council’s (Citation2019) “State of the Borough” report: 28% of the borough is open space, compared to the London average of 33% (although this is unevenly distributed within the borough); it is the 4th most deprived local authority in London (49th in the UK); 38% of residents are from BAME groups and 26% identify as “white other”; and the median hourly pay is 20% lower than the London average.

2. The term “affordance” comes from the cognitive psychologist James Gibson (Citation1979). It refers to the way in which an environment creates the conditions for – without instructing or determining – a particular kind of action. The concept has been taken up by influential writers including Nigel Thrift (Citation1996) and Tim Ingold (Citation2000).

3. These included: the Islington Gazette, the Hackney Gazette, the London Evening Standard, the Guardian, and the Times. The dispute online was followed through keyword searches on twitter: “Wireless”, “Finsbury Park”.

4. For those interested in a full history of the park see “A Park for Finsbury” by Hugh Hayes. A second edition is currently under work (https://www.thefriendsoffinsburypark.org.uk/news/book-launch-a-park-for-finsbury/).

5. It is worth noting that ideas of kinship have been taken up by a number of scholars thinking about alternative forms of social relationship. Notably feminist writers like Hayden (Citation1982), Harraway (Citation2016), Butler (Citation2002), and Lewis (Citation2019) have thought in different ways about how to re-imagine patriarchal family life. And as a range of sociological and anthropological work has unpacked, ideas of family kin can extend well beyond blood-ties (Carsten, Citation2003; Young & Willmott, Citation1957).

6. Center for Cities (Citation2019) Cities outlook. Center for Cities, London. Available from: https://www.centreforcities.org/publication/cities-outlook-2019/. Haringey Council has had its grant funding from central government reduced by £124 million since 2010 – a reduction of 62% (https://www.haringey.gov.uk/news/budget-fairer-haringey-have-your-say).

7. Friends of Finsbury Park is a charity that was formed in 1986. See Whitten (Citation2019) for a more detailed discussion about the wider role of friends groups in the organization of parks in London.

8. 12 foot = 3.6 meters.

References

- Amin, Ash. (2006). The good city. City, 43(5–6), 1009–1023. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600676717

- Amin, Ash. (2008). Collective culture and urban public space. City, 12(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810801933495

- Amin, Ash. (2012). Land of strangers. Polity.

- Amin, Ash. (2013). Telescopic urbanism and the poor. City, 17(4), 476–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.812350

- Amin, Ash. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7–8), 137–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490

- Anand, Nikhil, Gupta, Akhil, & Appel, Hannah. (2018). The promise of infrastructure. Duke University Press.

- Anderson, Elijah. (2011). The cosmopolitan canopy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 595(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716204266833

- Barnett, Clive. (2014). What do cities have to do with democracy? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(5), 1625–1643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12148

- Borch, Christian. (2012). The politics of crowds: An alternative history of sociology. Cambridge University Press.

- Bunnell, Tim, Yea, Sallie, Peake, Linda, Skelton, Tracy, & Smith, Monica. (2012). Geographies of friendship. Progress in Human Geography, 36(4), 490–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511426606

- Butler, Judith. (2002). Is kinship always already heterosexual? Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 13(1), 14–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-13-1-14

- Carmona, Matthew. (2010). Contemporary public space, part two: Classification. Journal of Urban Design, 15(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13574801003638111

- Carr, Stephen, Francis, Mark, Rivlin, Leanne, & Stone, Andrew. (1992). Public space. Cambridge University Press.

- Carsten, Janet. (2003). After kinship. Cambridge University Press.

- Center for Cities. (2019). Cities outlook. Center for Cities, London. https://www.centreforcities.org/publication/cities-outlook-2019/

- Cento Bull, Anna, & Jones, Bryn. (2006). Governance and social capital in urban regeneration: A comparison between Bristol and Naples. Urban Studies, 43(4), 767–786. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600597558

- Cesafasky, Laura. (2017). How to mend a fragmented city: A critique of ‘infrastructural solidarity’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(1), 145–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12447

- Cloke, Paul, & Conradson, David. (2018). Transitional organisations, affective atmospheres and new forms of being‐in‐common: Post‐disaster recovery in Christchurch, New Zealand. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(3), 360–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12240

- Cloke, Paul, May, Jon, & Williams, Andrew. (2017). The geographies of food banks in the meantime. Progress in Human Geography, 41(6), 703–726. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516655881

- Cowan, Thomas. (2019). The village as urban infrastructure: Social reproduction, agrarian repair and uneven urbanisation. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619868106

- Cranz, Galen. (1982). The politics of park design: A history of urban parks in America. MIT Press.

- DeLand, Michael. (2012). Suspending narrative engagements: The case of pick‐up basketball. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 642(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212438201

- Ehrenreich, Barbara. (2008). Dancing in the streets: A history of collective joy. London: Granta.

- Elkin, Lauren. (2016). Flaneuse: Women that walk the city in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London. Chatto & Windus.

- Finkel, Rebecca, & Platt, Louise. (2020). Cultural festivals and the city. Geography Compass, 14(9), e12498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12498

- Friends of Finsbury Park. (2016). About us. (2020 May 20) https://www.thefriendsoffinsburypark.org.uk/about/

- Gandy, Matthew. (2014). The fabric of space: Water, modernity, and the urban imagination. MIT.

- Gehl, Jan. (2011). Life between buildings: Using public space. Island Press.

- Gibson, James. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Goffman, Erving. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. Basic Books.

- Graham, Stephen, & Marvin, Simon. (1995). Telecommunications and the city: Electronic spaces, urban places. Routledge.

- Graham, Stephen, & Marvin, Simon. (2001). Splintering urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. Routledge.

- Graham, Stephen, & McFarlane, Colin. (2015). Infrastructural lives: Urban infrastructure in context. Routledge.

- Hall, Peter. (2014). Good cities, better lives: How Europe discovered the lost art of urbanism. Routledge.

- Hall, Sarah. (2019). Everyday austerity: Towards relational geographies of family, friendship and intimacy. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 769–789. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518796280

- Hall, Sarah. (2020a). Revisiting geographies of social reproduction: Everyday life, the endotic, and the infra-ordinary. Area, 52(4), 812–819. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12646

- Hall, Sarah. (2020b). Social reproduction as social infrastructure. Soundings, 76(winter), 82–94.

- Hancox, Dan. (2018). Inner city pressure: The story of grime. HarperCollins.

- Haringey Council. (2019). State of the borough profile. Haringey Council website (May 20, 2020) https://www.haringey.gov.uk/sites/haringeygovuk/files/state_of_the_borough_final_master_version.pdf

- Harraway, Donna. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Cthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Hayden, Dolores. (1982). The grand domestic revolution: A history of feminist designs for American homes, neighbourhoods, and cities. MIT press.

- Heynen, Nick, Kaika, Maria, & Swyngedouw, Erik. (2006). In the nature of cities: Urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism. Routledge.

- Hitchings, Russell, & Latham, Alan. (2017). How ‘social’ is recreational running? Findings from a qualitative study in London and implications for public health promotion. Health & Place, 46, 337–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.10.003

- Holston, James. (2008). Insurgent citizenship: Disjunctions of democracy and modernity in Brazil. Princeton University Press.

- Hou, Jeffrey. (2010). Insurgent public space: Guerrila urbanism and the remaking of contemporary cities. Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. (2000). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. Routledge.

- Iveson, Kurt. (2007). Publics and the city. Wiley.

- Jones, Alisdair. (2014). On South Bank: The production of public space. Routledge.

- Klinenberg, Eric. (2002). Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

- Klinenberg, Eric. (2012). Going solo: The extraordinary rise and surprising appeal of living alone. Penguin.

- Klinenberg, Eric. (2015). Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Klinenberg, Eric. (2018). Palaces for the people: How to build a more equal and united society. Penguin Random House.

- Koch, Regan, & Latham, Alan. (2012). Rethinking urban public space: Accounts from a junction in West London. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 37(4), 515–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00489.x

- Koch, R., & Miles, S. (2020). Inviting the stranger in: Intimacy, digital technology and new geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 0309132520961881.

- Koch, Regan, & Miles, Sam. (2020). Inviting the stranger in: Intimacy, digital technology and new geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 030913252096188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520961881

- Krenichyn, Kira. (2006). ‘The only place to go and be in the city’: Women talk about exercise, being outdoors, and the meanings of a large urban park. Health & Place, 12(4), 631–643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.015

- Lachmund, Jens. (2013). Greening Berlin: The co-production of science, politics, and urban nature. MIT Press.

- Larkin, Brian. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Latham, Alan, & Layton, Jack. (2019a). Kinaesthetic cities: Studying the worlds of amateur sports and fitness in contemporary urban environments. Progress in Human Geography, 44(5), 852–876. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519859442

- Latham, Alan, & Layton, Jack. (2019b). Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces. Geography Compass, 13(7), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12444

- Lewis, Sophie. (2019). Full surrogacy now: Feminism against family. Verso.

- Lofland, Lyn. (1973). A world of strangers: Order and action in urban public space. Basic Books.

- Low, Setha, Taplin, Dana, & Scheld, Suzanne. (2005). Rethinking urban parks: Public space and cultural diversity. The University of Texas Press.

- Marovelli, Brigda. (2019). Cooking and eating together in London: Food sharing initiatives as collective spaces of encounter. Geoforum, 99, 190–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.006

- Marres, Noortje. (2012). Material participation: Technology, the environment and everyday publics. Palgrave.

- McFarlane, Colin, & Silver, Jonathon. (2017). Navigating the city: Dialectics of everyday urbanism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(3), 458–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12175

- McKenzie, Thomas, Cohen, Deborah, Sehgal, Amber, Williamson, Stephanie, & Golinelli, Daniela. (2006). System for observing play and recreation in communities (SOPARC): Reliability and feasibility measures. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3(Feb, Suppl. 1), S208–S222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s208

- McNeill, William. (1997). Keeping together in time: Dance and drill in human history.. MA. Harvard University Press.

- Middleton, Jenny. (2018). The socialities of everyday urban walking and the ‘right to the city’. Urban Studies, 55(2), 296–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016649325

- Milligan, Christine, & Wiles, Janine. (2010). Landscapes of care. Progress in Human Geography, 34(6), 736–754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510364556

- Neal, Sarah, Bennett, Katy, Cochrane, Allan, & Mohan, Giles. (2019). Community and conviviality? Informal social life in multicultural places. Sociology, 53(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518763518

- Neal, Sarah, Bennett, Katy, Jones, Hannah, Cochrane, Allan, & Mohan, Giles. (2015). Multiculture and public parks: Researching super‐diversity and attachment in public green space. Population, Space and Place, 21(5), 462–475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1910

- Nethercote, Megan. (2017). When social infrastructure deficits create displacement pressures: Inner city schools and the suburbanization of families in Melbourne. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12509

- Pahl, Ray. (2000). On friendship. Cambridge: Polity.

- Parkinson, John. (2012). Democracy and public space: The physical sites of democratic performance. Oxford University Press.

- Penny, Joe. (2019). ‘Defend the ten’: Everyday dissensus against the slow spoiling of Lambeth’s libraries. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(5), 923–940. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819893685

- Portes, Alejandro. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Power, Emma, & Williams, Miriam. (2020). Cities of care: A platform for urban geographical care research. Geography Compass, 14(1), e12474. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12474

- Pries,Jönsson,& Mitchell. (2020). “Parks and Houses for the People.” Places Journal, May 2020. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22269/200512

- Putnam, Robert. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Rogers, Dennis, & O’Neill, Bruce. (2012). Infrastructural violence: Introduction to the special issue. Ethnography, 13(4), 401–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435738

- Roseneil, Sasha, & Budgeon, Shelley. (2004). Cultures of intimacy and care beyond ‘the Family’: Personal life and social change in the early 21st Century. Current Sociology, 52(4), 135–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392104041798

- Rosenzweig, Roy, & Blackmar, Elizabeth. (1992). The park and the people: A history of Central Park. Cornell University Press.

- Sandercock, Leonie. (2003). Cosmopolis II: Mongrel cities of the 21st Century. Bloomsbury.

- Sebanz, Natalie, Bekkering, Harold, & Knoblich, Günther. (2006). Joint action: Bodies and minds moving together. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(2), 70–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.009

- Sen, Amartya. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Sen, Amartya. (2009). The idea of justice. Penguin.

- Sennett, Richard. (2012). Together: The rituals pleasures, and politics of cooperation. Penguin.

- Sennett, Richard. (2017). Building and dwelling: Ethics for the city. Penguin.

- Sharkey, Patrick. (2018). Uneasy peace: The great crime decline, the renewal of city life, and the next war on violence. W. W. Norton.

- Shaw, Ian. (2019). Worlding austerity: The spatial violence of poverty. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(6), 971–989. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819857102

- Silver, Jonathon, & McFarlane, Colin. (2019). Social infrastructure, citizenship and life on the margins in popular neighbourhoods. In Charlotte Lemanski (Ed.), Citizenship and infrastructure practices and identities of citizens and the state (pp. 22–42). Routledge.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. (2004). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-407

- Smith, Andrew. (2012). Events and urban regeneration: The strategic use of events to revitalise cities. Routledge.

- Staeheli, Lynn, & Mitchell, Don. (2007). Locating the public in research and practice. Progress in Human Geography, 31(6), 792–811. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507083509

- Staeheli, Lynn, Mitchell, Don, & Nagel, Caroline. (2009). Making publics: Immigrants, regimes of publicity and entry to ‘the public’. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 27(4), 633–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/d6208

- Star, Susan Leigh. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

- Stenning, Alison (2020). Tackling loneliness with resident-led play streets [report]. Newcastle upon Tyne university, (20 May 2020) https://playingout.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Tackling-Loneliness-with-Resident-Led-Play-Streets-Final-Report.pdf

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The ludic city: exploring the potential of public spaces. London: Routledge.

- Strauss, Kendra. (2019). Labour geography III: Precarity, racial capitalism and infrastructure. Progress in Human Geography, 44(6), 1212–1224. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519895308

- Talen, Emily. (2019). Neighbourhoods. Oxford University Press.

- The Friends of Finsbury Park v Haringey Council (2017). Court of appeal (civil division) on appeal from the high court, case C1/2016/2662. (2020 September 13). https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/fofp-v-haringey-lbc-judgment-16112017.pdf

- Thrift, Nigel. (1996). Spatial formations. Sage.

- Till, Karen. (2012). Wounded cities: Memory-work and a place-based ethics of care. Political Geography, 31(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.10.008

- Tonkiss, Fran. (2015). Afterword: Economies of infrastructure. City, 19(2–3), 384–391. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1019232

- Tupper,Atkinson,& Pollard. (2020) Doing more with movement: Constituting healthy publics in movement volunteering programmes. Palgrave Communications,6(94), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0473-9

- Valentine, Gill. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133308089372

- Vincent, Carol, Neal, Sarah, & Iqbal, Humera. (2018). Friendship and diversity: Class, ethnicity and social relationships in the city. Palgrave.

- Wacquant, Loıc. (2004). Body & soul. Oxford University Press.

- Wakefield, Stephanie. (2018). Infrastructure of liberal life: From modernity and progress to resilience and ruins. Geography Compass, 12(7), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12377

- Warner, Michael. (2002). Publics and counterpublics. MIT Press.

- Watson, Sophie. (2006). City publics: The (dis)enchantments of encounters in public space. Routledge.

- Webb, Darren. (2005). Bakhtin at the seaside: Utopia, modernity and the carnivalesque. Theory, Culture & Society, 22(3), 121–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276405053724

- Weeks, Jeffrey, Heaphy, Brian, & Donovan, Catherine. (2001). Same sex intimacies: Families of choice and other life experiments. Routledge.

- Wellman, Barry. (1979). The community question: The intimate networks of East Yorkers. American Journal of Sociology, 84(5), 1201–1231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/226906

- White, Joy. (2017). Urban music and entrepreneurship: Beats, rhymes and young people’s enterprise. Routledge.

- White, Joy. (2020). Terraformed: Young black lives in the inner city. Repeater.

- Whitten, Meredith. (2019). Blame it on austerity? Examining the impetus behind London’s changing green space governance. People, Place and Policy, 12(3), 204–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3351/ppp.2019.8633493848

- Wilson, Helen. (2013). Collective life: Parents, playground encounters and the multicultural city. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(6), 625–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.800220

- Wilson, Helen. (2017). On geography and encounter: Bodies, borders and difference. Progress in Human Geography, 41(4), 451–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516645958

- Wilste, Jeff. (2007). Contested waters: A social history of swimming pools in America. University of North Carolina Press.

- Wittel, Andreas. (2001). Toward a network sociality. Theory, Culture & Society, 18(6), 51–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/026327601018006003

- Woodbine, Onaje. (2016). Black gods of the asphalt: Religion, hip‐hop, and street basketball. Columbia University Press.

- Young, Michael, & Willmott, Peter. (1957). Family and kinship in East London. Routledge.