ABSTRACT

In this study, we examine whether the spatial structure produces differences in access to social capital and the status homogeneity of networks in Santiago, the capital of Chile—a highly segregated city. We hypothesize that residents of different areas, especially those living in spatial contexts of poverty and wealth, differ considerably in terms of the social resources to which they have access. We combine survey data with georeferenced data from 700 residents in 181 census tracts. The spatial structure is measured as a combination of spatial conditions, such as land values, density, and urban violence. Our results show that the spatial structure determines network resources, even after considering social class. Specifically, living in privileged areas is associated with highly resourceful networks, whereas living in marginalized areas goes together with network poverty and low-status contacts. Taken together, our results suggest that spatial segregation reinforces differential social resources among classes.

Introduction

From the famous Plaza Baquedano (also known as Plaza Italia) in Santiago, Chile’s capital, you have the option of walking in one of two directions: “abajo” (down) toward the southwest, or “arriba” (up) toward the Andes in the northeast. The first option takes you literally and symbolically down toward the lower-class districts, while the second leads to the wealthy ones. The contrast between the two parts of the city is dramatic and reflects Chile’s extreme economic inequality, a reality which in late 2019 sparked large-scale demonstrations centered on Plaza Baquedano.Footnote1 Above, you find the “winners” who have benefitted from the long-term neoliberal policies implemented in the 1970s during the Pinochet dictatorship and who live in safe, green neighborhoods with private facilities and fancy shopping malls. Below, you find people deprived of decent living standards, residing in crowded slums without adequate provision of public healthcare and education (e.g. Agostini et al., Citation2016; Borsdorf et al., Citation2016; Garretón, Citation2017; Link et al., Citation2015). The areas in the “middle” counterbalance this pattern of segregation, showing that the spatial concentration of affluent or deprived groups tends to occur alongside other urban dynamics such as gentrification, social mixing, and urban sprawl (see also López-Morales, Citation2016; De Mattos et al., Citation2016).

Although the causes and trends of spatial segregation in Santiago have been explored extensively, there is relatively less knowledge concerning the consequences of spatial inequality in terms of residents’ life opportunities. Researchers have shown that spatial segregation in Santiago has led to marked differences regarding neighborhood cohesion, lifestyles and identities, accessibility to services, fear of crime, educational outcomes, and perceived residential stigma among residents from different spatial configurations (Brain & Prieto, Citation2021; Cortés, Citation2021; Dammert, Citation2004; Márquez & Pérez, Citation2008; Méndez et al., Citation2021; Otero, Carranza et al., Citation2021; Otero, Méndez et al., Citation2021). Despite these valuable contributions, however, we still do not know how spatial segregation affects one essential aspect of societal life: the way in which people make social connections and form social networks that can help them to climb the social hierarchy, or more precisely, how and why various features of urban geography are associated with social capital. To address this gap in knowledge, we examine differences in access to social capital across the spatial structure in Santiago.

Social capital researchers have been especially concerned with understanding the association between social class and social capital in different countries, including Chile (see Otero, Volker et al., Citation2021). Several endeavors have focused on examining the role of space in access to social capital and the degree of homogeneity of such network resources (e.g. Marques, Citation2015; Pinkster & Volker, Citation2009; Small, Citation2007; Van Eijk, Citation2010). In general, however, research has focused on urban poverty or lower-class areas and has left aside specific explanations of how spatial segregation may influence access to resourceful networks across the entire urban structure (c.f., Wiesel, Citation2019). To shed light on this issue, we provide a theoretical overview of the ongoing process of neoliberal urbanization (e.g. the commodification of housing and colonization of new spaces) – of particular relevance in Chile (Garretón, Citation2017) – before critically engaging with arguments on concentrated poverty and urban marginality (e.g. Wacquant, Citation2008; Wilson, Citation1987) and literature on upper middle-class residential strategies (e.g. Andreotti et al., Citation2015; Méndez & Gayo, Citation2019) in order to further understand the implications of spatial inequality for social capital.

The main objective of our study is to examine spatial differences in access to social capital. As social class is a well-known condition that explains differences in access to social resources, we test whether the spatial structure itself has additional consequences for social capital. We also argue that a strong influence of spatial patterns on social capital may result in largely homogeneous networks, as spatial characteristics shape people’s opportunities to make contacts. Spatial segregation may play an important role in reinforcing patterns of social stratification through inequality in social resources, whether constraining access to structures of opportunities among the urban poor or increasing opportunity hoarding among the urban privileged (e.g. Espinoza, Citation1999; Kaztman, Citation2001; Lomnitz, Citation1977).

Our research questions are as follows:

To what extent is the spatial structure of Santiago associated with inequality in access to social capital?

More specifically, to what extent is the spatial structure associated with homogeneity of network resources?

To address these questions, we combine survey and georeferenced data collected in 2016 from a total of 700 residents between 18 and 75 years of age, living in 181 census tracts. The paper is structured as follows: in the next section we elaborate on our theory concerning the impact of neoliberal urbanism on spatial segregation before making a specific distinction between “neighborhood as constraint” and “neighborhood as opportunity” in terms of social capital acquisition. We then describe the essential spatial characteristics of Santiago before presenting our data, measurements, and analyses. Finally, we discuss our findings.

Theoretical background

Neoliberal urbanism, spatial segregation, and social capital

There are multiple perspectives regarding what social capital entails. Here, we take a “resource perspective”, whereby social capital is understood as the resources embedded in people’s social networks (Bourdieu, Citation1986; Flap & Volker, Citation2004; Lin, Citation2001; Lin & Erickson, Citation2008). Those with large networks of high-status individuals and/or who know people with a varied set of occupations are said to have a high level of social capital. This type of social capital has shown to be strongly associated with class, favoring members of the upper class, and has demonstrated being crucial for the achievement of important goals and obtaining support in various aspects of life (e.g. Contreras et al., Citation2019; Rözer & Brashears, Citation2018; Van Tubergen & Volker, Citation2015).

When attempting to understand the role of space in the creation and distribution of social capital, residential segregation is key. Segregation refers to the concentration of groups, usually in terms of socio-economic status, class, or income, leading to spatial clustering of wealth, power, or other resources (Marcuse, Citation2005). Drawing on critical theoretical arguments, we contend that spatial segregation is primarily the result of neoliberal restructuring projects, an ideology which has advanced through the devaluation of the role of the public sector in the provision of social protection and the promotion of the market as an essential agent in the distribution of resources (Brenner & Theodore, Citation2002; Peck et al., Citation2013). More precisely, urban neoliberalism has pushed cities toward capital accumulation through the commodification of urban spaces, which involves, for instance, increasing land values, the speculative interests of private developers, and the marketization of social housing (see also Fainstein, Citation2010).

The implementation of neoliberal policies has been radical in some Latin American countries, and in Chile especially. Initially promoted and installed during the military dictatorship (1973–1990), Chilean neoliberalism has been characterized by intense privatization reforms in the industrial and basic needs sectors, including in the education, healthcare, and pensions systems (Taylor, Citation2003). These market-oriented policies have become further institutionalized since the return to democracy, leading to stark differences in educational opportunity and large inequalities in well-being among the social classes (e.g. Gayo et al., Citation2019; Rotarou & Sakellariou, Citation2017).

In terms of urban policy, neoliberal urbanism has encouraged various market-led implementations (Garretón, Citation2017). One example is urban renewal in historic central areas, including mega-scale interventions (e.g. financial districts and commercial centers) and high-rise residential developments. These transformations have driven gentrification and displacement, along with increased densification and considerable loss of urban heritage in urban centers (López-Morales, Citation2016). In addition, public policy regarding housing subsidies has increasingly relied on private supply (Hidalgo et al., Citation2019). Housing programs (for lower-income residents) have offered minimal compliance with construction standards and have generally been sited on the urban periphery, almost exclusively in areas where land prices are lowest and access to services is poorest. This kind of social housing has reinforced the concentration of marginality and poverty driven initially through the informal production of housing and characterized subsequently by high social homogeneity and overcrowded conditions (see also Hidalgo, Citation2019).

The ongoing process of neoliberal urbanization has also provided fertile ground for the emergence and expansion of “neoliberal subjectivity”, represented by self-selection on the part of more privileged groups in Santiago (Méndez et al., Citation2021). Studies have shown the considerable capability of the upper middle classes to choose their place of residence and satisfy their increasing preference for living “among equals” in selective suburbs and enclaves (Méndez & Gayo, Citation2019). A relatively large portion of this group have pushed themselves into inaccessible gated communities, which have become subcenters surrounded by schools, shopping malls, and private healthcare centers (Borsdorf et al., Citation2016). The high land value of affluent residential environments logically allows upper middle-class residents to increase their social and physical distance from others.

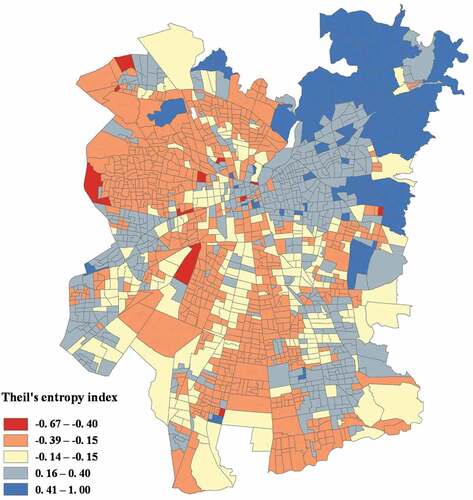

In short, the functioning of neoliberal urbanism has severely restricted the role of the state in establishing and assuring adequate residential conditions for those who experience resource deficits, while promoting a kind of spatial differentiation at the top of the spatial structure. As a result, Santiago now presents a clear spatialization of social classes, with levels of segregation comparable only to the racial segregation found in the most unequal US cities (Agostini et al., Citation2016). As shown in , most of the people from the lower classes have been pushed toward the southern and western peripheries of Santiago (red and orange census tracts) where social housing projects have been built over the past four decades. Although public healthcare and education are available in these areas, the level of quality and infrastructure has systematically deteriorated. Sustained disinvestment in these urban spaces has led to chronic levels of urban violence, and class distinctions have become more acutely visible in terms of place confinement, the demonization of social housing, and territorial stigmatization (Otero, Méndez et al., Citation2021). By contrast, since the 1980s, people from the middle classes have clustered in suburban houses and high-rise apartment blocks in more central districts (light blue census tracts), while from the 1990s onwards, the upper classes have settled and become consolidated in the north-eastern part of the city (blue census tracts), enjoying privileged access to green spaces and recreational facilities, as well as safe and secure environments (Garretón, Citation2017).

The current state of segregation in Greater Santiago suggests that the most privileged and the most impoverished groups have become largely separated, with almost no spatial connection between them. As such, spatial segregation is likely to be reinforcing class divisions, in particular, conditioning the opportunities available to the lower classes and increasing the advantages of the privileged in terms of social capital acquisition. Our argument is that network segregation, driven by processes of urban neoliberalization, (re)produce differences in social resources across the spatial structure through several mechanisms. For instance, spatial segregation arguably shapes a reality in which the everyday lives of the affluent and the rest (especially the lower classes) increasingly take place in different locations, thereby restricting social connections to similar-class others. In the following sections, we elaborate further on how spatial segregation might foster differential social capital, especially at either end of the spatial spectrum.

Living in lower-class areas: “Neighborhood as constraint”

The urban deprivation of the lower classes caused by exclusionary urban policies greatly restricts individuals’ chances of establishing social bonds with dissimilar-class others. The so-called “social isolation” thesis was initially proposed by Wilson (Citation1987) as a means of understanding the racial and social class exclusion generated by processes of post-industrialization in the US. People living in poor or low-income areas are said to suffer from a lack of contact with (upper) middle-class individuals, not only due to physical distance, but also because they have limited opportunities to formally participate in mainstream institutions, especially the labor market. Some of this reasoning is similar to that employed in the 1960s and 1970s by scholars who developed the theory of marginality in Latin America, addressing the rapid urbanization and emergence of a “marginal” mass in major cities in the context of dependent industrialized economies (e.g. Lomnitz, Citation1977). However, despite its prominence, this perspective has been criticized and widely abandoned in Latin America, as it represents a somewhat simplified illustration of low-income areas and urban peripheries. These social realities feature not only employment exclusion, but also land conflict, urban abandonment, urban violence, citizenship mobilization, and many other experiences (e.g. Caldeira, Citation2009), all of which are potential drivers that may further explain social isolation among the most deprived urban residents (e.g. Espinoza, Citation1999; Kaztman, Citation2001; Marques, Citation2015).

Some Latin American scholars have described a rapid worsening of urban infrastructure and accessibility to services due to state cuts in service provision and disinvestment practices operated by private agents in lower-class areas (e.g. Caldeira, Citation2017; Janoschka & Salinas, Citation2017). These include, for instance, inferior public services and goods (e.g. schools, healthcare), inadequate retail services, poor recreational facilities and community buildings, and lack of maintenance of public space. In some cases, these chains of abandonment and land value depreciation have been followed by gentrification in the form of revitalization policies and large-scale investment by private actors (see Janoschka et al., Citation2014; López-Morales, Citation2016). All these processes can logically have devastating implications for people living at the lower end of the spatial spectrum, not only in terms of degrading their living conditions, but also the reduction of spaces of sociability that are essential to the creation of social capital.

In contexts of extreme inequality such as those found in Latin America, far-reaching neoliberal policies and their consequences in terms of unequal distribution of resources in urban spaces can be seen as a cause of crime and violence among the urban poor, including widespread theft, mugging, burglary, drug-dealing, gang violence, and homicide (Caldeira, Citation2000). This kind of violence is argued to be a sign of “status frustration” and a form of political violence that is closely associated with modes of state intervention in relegated neighborhoods (see also Auyero, Citation2015). Although urban violence has the potential to give rise to collective action, it is more likely to discourage interactions between neighbors and make these areas unattractive destinations for visitors (Van Eijk, Citation2010). Consequently, it can also result in smaller social networks and fewer opportunities for people living in marginalized areas to form and preserve non-local ties with residents of other neighborhoods.

In addition, urban deprivation can translate into more symbolic forms of stratification, such as residential stigma, further reinforcing the exclusion of the urban poor (Wacquant, Citation2008). Residential stigma has become especially visible on the outskirts of large cities in Latin America (Wacquant et al., Citation2014). In Santiago, long-standing territorial stigma has even become part of internal perceptions among the inhabitants of areas characterized by high concentrations of poverty, land devaluation, density, and overcrowding (see Otero, Méndez et al., Citation2021). These poor internal and external reputations can exacerbate discrimination and impede labor market participation, as well as restricting sociability between residents and access to valuable social networks available outside their neighborhoods (e.g. Wacquant, Citation2008; Warr, Citation2005).

In short, our arguments highlight the different constraints endured by people living in deprived areas in terms of creating social capital in the form of resourceful networks. This means that although residents might have many relationships with similar others (e.g. Hill et al., Citation2014), these connections are unlikely to involve the levels of resources, social power, and prestige available to those in middle-class or affluent areas, and probably restrain their opportunities for social mobility (Espinoza, Citation1999; Link et al., Citation2017; Marques, Citation2015).

Living in affluent areas: “Neighborhood as opportunity”

Spatial segregation can result in unequal access to social capital, not only due to the urban deprivation of lower-class residents, but also because of the social and material aspects that motivate the affluent to “shape and control” homogeneous upper-class neighborhoods (e.g. Andreotti et al., Citation2015; Massey, Citation1996; Pinçon-Charlot & Pinçon, Citation2018). Affluent (segregated) areas are often configured beyond the contact range of individuals perceived to be socially different or dangerous, and likely allow privileged residents to further increase their advantages (Atkinson, Citation2008). This pattern of self-segregation among the privileged has been particularly strong in Latin American cities (e.g. Borsdorf et al., Citation2016), but has also spread to more egalitarian contexts such as the capital cities of Europe (e.g. Musterd et al., Citation2017).

To begin, the self-segregation of the upper (middle) classes logically causesthe privileged to be physically closer to one another, and consequently produces the concentration of social resources (Wiesel, Citation2019). Social interactions among upper-class individuals are particularly likely when neighborhoods offer plenty of meeting places where people can gather and engage in joint activities, which is common in affluent neighborhoods (e.g. Volker et al., Citation2007). It is well known that the upper middle classes precisely focus on gaining access to high-quality establishments and facilities within their chosen residential sector (Bacqué et al., Citation2015). Selective affluent residential areas in Santiago, for instance, are characterized by high-quality infrastructure, providing access to extensive green areas, cultural facilities, commercial areas, and social clubs (e.g. Garretón, Citation2017). This implies that residents of wealthier areas have spaces in which not only to relax with relatives, friends, and pets, but also to meet and engage with similar-class neighbors, share interests in agreeable surroundings, form bonds, invest time, express their emotions, and maintain their class sociability (e.g. Méndez & Gayo, Citation2019). These opportunities contrast strongly with those available in more deprived areas.

Related literature on the upper middle classes and place attachment has also shown that the privileged tend to incorporate their own biography into their chosen residential places (e.g. Savage et al., Citation2005). In other words, they generally select neighborhoods that match their “class habitus”, that is, places appropriate to their class trajectories (e.g. Benson, Citation2014). This strategy, in turn, has proved to produce a strong sense of belonging among those living in affluent places and to considerably boost the way in which the urban privileged experience their local cohesion (Maloutas & Pantelidou-Malouta, Citation2004). A recent study of Santiago, for instance, showed that neighborhood cohesion operates as a form of privilege, in the sense that it is more common among residents of affluent areas (see Méndez et al., Citation2021). Residents reported high levels of identification, feelings of physical belonging, trust in neighbors, and local participation, all of which are essential to fostering access to more socio-economically valuable social contacts and the construction of homogeneous networks.

Although the symbolic factor of residential stigma is closely associated with deprived areas and likely has detrimental consequences for the urban poor, it is also probable that residential reputation represents an important factor in boosting the social and economic advantages of the urban privileged (e.g. Permentier et al., Citation2008). In this case, visual signals of wealth, such as manicured green areas and cleanliness, serve as indicators of affluence and demonstrate the importance of the neighborhood as a focal point for convergence of the upper classes and its inaccessibility to others. In Santiago, other factors like public safety and low density have also been linked to concentrated affluence and residential reputation (see Otero, Méndez et al., Citation2021). Ultimately, the latter allows residents of affluent areas to further increase the high land value, exclusiveness, and status of their neighborhoods, thereby restricting entry to others and promoting social homogeneity.

Whatever the factors that enable the urban privileged to gain more prestigious social contacts and form class-homogenous networks, our approach suggests that affluent segregated residential areas are spaces where social capital is produced and accumulated. Indeed, these areas provide insulation within which residents can embrace social similarity and avoid contact with social difference, constituting what Atkinson (Citation2008) has termed a “misanthropic” form of social capital. In the end, these valuable social networks – instances of “managerial” social capital – in the urban space are likely an essential condition for reproduction of privilege (see also Wiesel, Citation2019).

Summary

In Santiago, strong patterns of spatial segregation have endured and even worsened over time due to the spread of neoliberal urbanism, and this is likely to be reinforcing inequality and social distances between classes. The urban geography may present a wide range of opportunities for those living in “privileged” areas to access greater social capital and reinforce their class sociability. In contrast, the urban poor probably have limited opportunities to meet others of different status. Residents of areas in the “middle” may not have the same proportion of high-status contacts as their upper-class peers, but their networks are likely to be more diverse than those of the other groups, with contacts from both ends of the social hierarchy.

Based on these arguments, we expect spatial segregation to have contrasting consequences in terms of social capital creation for those living in urban areas of poverty and wealth. Specifically, we suppose that the former suffer a reduction in access to social capital, while the latter enjoy an increase. In addition, spatial segregation might be forging parallel lives whereby people from different social classes rarely meet and interact, remaining separated by economic and cultural barriers and by socio-spatial boundaries. As such, spatial segregation expressed through concentrated poverty and affluence may also reinforce segregation of social capital on both sides of the divide, restricting social connections to similar-class others. We therefore additionally expect to see spatial segregation to increase homogeneity in terms of the status of network resources.

Data, measurements, and methods

Data

We used survey data collected in 2016 during the first wave of the Chilean Longitudinal Social Survey (ELSOC), designed by the Center for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES) (see ELSOC, Citation2018). The sample frame was proportionally stratified by population strata (six population scales), and respondents participated in face-to-face interviews following random selection of households within 1,067 city blocks. The overall response rate of the survey was 62%. For the purposes of this study, we analyzed only the data of respondents who reside in the Metropolitan Area of Greater Santiago – a total of 700 residents. Greater Santiago has over 7 million inhabitants – approximately 40% of the current Chilean population.

This individual data was complemented with georeferenced administrative information for 181 census tracts. The georeferenced information was produced by the Center for Territorial Intelligence (CIT) and based on a range of administrative sources, including the pre-census survey from 2011 and information from social protection (welfare) records held by the Ministry for Social Development.

The position generator as a measurement of social capital

The Position Generator is a well-established survey instrument used to measure access to social capital (see Lin, Citation2001). The Position Generator captures the connections that people have with others from different levels of the occupational structure, e.g. taxi drivers, doctors, and accountants. In our case, we posed the following question to our respondents (our own translation from Spanish):

Now I will ask you about some of your acquaintances. It does not matter whether they are close to you (family members or friends) or not. An acquaintance is someone you know at least by first name and with whom you might talk if you came across each other in the street or at a shopping mall. Think only of people who live in Chile. Can you tell me, based on the following card (and even if only approximately), how many people you know who are … ?

Respondents were then shown a list of thirteen occupations, namely: (1) manager of a large firm, (2) street vendor, (3) secretary, (4) car mechanic, (5) shop assistant, (6) attorney, (7) office cleaner, (8) doctor, (9) preschool teacher, (10) taxi driver, (11) waiter, (12) accountant, and (13) university professor. Seven response alternatives were available: none, one, 2–4, 5–7, 8–10, 11–15, and 16 or more. For analysis, we assigned midpoints to the original intervals (e.g. range 2–4 was coded as “3”).

Based on respondents’ answers, we built six variables to represent access to social capital:

Number of contacts. The total number of people known across all of the thirteen occupations included in the Position Generator.

Contact variety. The number of different occupational status positions accessed within the respondent’s social network. This is a traditional measure in the social capital literature (e.g. Van Tubergen & Volker, Citation2015).

Contact status. The average occupational prestige weighted by the number of contacts of each occupation that an individual has in his or her network (e.g. Contreras et al., Citation2019). Occupational prestige scores were assigned according to the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI). Table S1 (in the Supplemental Materials) presents further information about the occupations included and the ISEI scores assigned.

Network composition (three measures). We separated the occupations included in the Position Generator into three occupational levels, closely resembling the Goldthorpe class scheme: higher- (ISEI range: 65–88), medium- (ISEI range: 40–64), and lower- (ISEI range: 16–39) status positions (see Table S1 in the supplemental materials). We then calculated three different measures, namely the proportion of high-status, medium-status, and low-status contacts in respondents’ social networks.

Measuring the (urban) spatial structure

We investigate the variations in access to social capital across the spatial structure, especially in the privileged and marginalized areas. Analytically, this implies that we must identify the different spatial configurations that exist within the city, i.e. areas with similar characteristics. Clustering techniques are a suitable method for achieving this goal because they permit the identification of units that are homogeneous with respect to each other but heterogeneous with respect to others. In this study, we specifically applied Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC) using georeferenced data obtained at the census tract level. Here, different principal components methods are used as a pre-procedure in order to facilitate a more reliable clustering solution later (see Husson et al., Citation2011).

In our case, the first step of the HCPC is based on a Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which is used to reduce the georeferenced (continuous) data to a set of fewer dimensions. We incorporated 15 spatial characteristics, including the proportion of residents in five socio-economic strata (SES), land value (per square meter), accessibility to green spaces within a 15-minute walk (square meters), and criminal behavior (two scores). In addition, we included spatial segregation based on SES using an adjusted Theil’s entropy index that quantifies SES balance across geographic units. While values closer to 1 represent more segregated areas, those closer to 0 indicate a socio-economic mix. The values of predominantly lower-SES areas (low and poor) were multiplied by −1 to capture segregation at the two poles of the spatial structure. This spatial indicator forms the basis of , which represents the spatial segregation of Santiago.

In our analysis, the first four principal components explain 77.5% of the total variance, which is an acceptably large portion. The first component of the PCA clearly represents SES polarization across the spatial structure, while the other components represent the presence of Peruvians, Colombians, and Central Americans; the presence of medium-SES population; and residential density, respectively. Table S2 (in the Supplemental Materials) shows the detailed results of the PCA analysis.

The second step of the HCPC was performed by means of a hierarchical clustering using Ward’s criterion on the selected principal components, and the final step was conducted using a k-means clustering algorithm to improve the previous partition. Based on these analyses, we arrived at a five-spatial-cluster solution that accurately represents the (urban) spatial structure of Santiago. These are reasonably robust and meaningful groups. We assigned a name to each cluster in order to distinguish them in subsequent analyses. There follows a brief description of the spatial clusters and their size, and Table S3 (in the Supplemental Materials) presents more detailed information regarding the distribution of spatial characteristics between spatial clusters.

Affluent areas (17.1%): Concentrated wealth, very high years of schooling, low unemployment, high land value, high levels of material appropriation but no urban violence, very low density, accessibility to green spaces, residential fluctuation, and relatively large presence of primarily type 1 immigrant population (Europeans, North Americans, Argentinians).

Middle-class areas (27.1%): Middle-class concentration, average years of schooling, low unemployment, low land value, low levels of material appropriation and urban violence, lack of accessibility to green spaces, and small presence of immigrant population.

Mixed areas (9.9%): Middle-class mixed areas, high years of schooling, high land value, high scores of material appropriation and urban violence, high density, accessibility to green spaces, residential fluctuation, and relatively large presence of type 2 immigrant population (Peruvians, Colombians, Central Americans).

Lower-class areas (23.2%): Lower-class concentration, low years of schooling, unemployment, low land value, low levels of material appropriation and urban violence, very low density, residential stability, and small presence of immigrant population.

Marginalized areas (22.7%): Concentrated poverty, very low years of schooling, unemployment, low land value, very low levels of material appropriation but very high urban violence, very high density, lack of accessibility to green spaces, residential stability, and very small presence of immigrant population.

Given the relevance to the present study of differences in opportunities regarding residential choice between people from different spatial areas, we analyzed whether or not residents were able to choose their current place of residence, which was one of the questions included in the survey. We found that residential choice is mostly limited to those living in affluent areas, where 82% of respondents reported having residential choice. This figure then fell to 59% in mixed areas, 55% in middle-class areas, 36% in lower-class areas, and 32% in marginalized areas. This considerable discrepancy in residential choice across the spatial structure indicates that the lower classes are generally confined – through no choice of their own – to marginalized areas and suggests a possible role of the upper classes as “segregators”.

Measuring social class

To measure social class, we aggregated three important sources of social stratification: the highest level of education obtained, occupational class, and total monthly household income. With respect to education, we used five categories: no formal education, primary, secondary, vocational, and university education. Occupational class was measured using the classification devised by the UK National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC) and based on the influential Goldthorpe class schema. Household income was recoded into five categories to enable analysis along with the other (categorical) variables.

Finally, we applied the same strategy as that for the measurement of spatial structure; that is, an agglomerative hierarchical clustering with selected principal components. In this case, the first pre-processing step of the analysis was conducted using Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), which permits the calculation of clusters in categorical data. We obtained a solution of five clusters that were clearly different from one another (see Table S4 in the Supplemental Materials). For instance, upper middle-class individuals (representing 11.1%) have high financial capital (average monthly household income of approximately USD 3,800); tend to work as higher managers/professionals (56.2%), e.g. engineering professionals, lawyers, doctors; and have university education (85.9%). Conversely, individuals from the poorest class (representing 11%) have low financial capital (average monthly household income of approximately USD 350), have no formal education (46.2%), and tend to be unemployed or retired. Individuals from the established middle, emerging middle, and working class represent 14.6%, 39.4%, and 23.9% of the total, respectively.

The extent to which the two generated classifications (individuals’ social class and spatial clusters) are crossed may have several consequences for the results. We therefore inquired into the relationship between class and spatial structures in Greater Santiago. We found that of the upper middle class, 55.6% live in affluent areas, 24.8% in middle-class areas, and 19.6% in other areas. Of the poor/precariat, 42.7% live in marginalized areas, 35.9% in lower-class areas, and 21.4% in other areas (see Table S5 in the Supplemental Materials). As such, there is almost no spatial connection between the two extremes of the spatial structure.

Analytical strategy

Multilevel models were used to examine differences in access to social capital across the spatial structure. Unlike traditional regression analysis, multilevel models consider the nested structure of the data (Snijders & Bosker, Citation1999). In our case, observations at the individual level (residents) are nested within census tracts. In these models, social capital measures represent the dependent variables, whereas the spatial clusters are the main independent variables, along with social class. We also included four key control variables: gender (1 = woman), age (years), having a partner (being married or cohabiting), and home ownership. The analyses involved fitting four different regression models for each dependent variable in order to test the separate and joint “effects” of spatial and class structures on social capital.

Findings

Descriptive analyses

We begin by analyzing descriptive findings (see ). First, regarding general network characteristics, we observe that social networks of upper middle-class individuals tend to be larger, more varied, and more prestigious in terms of status positions than middle- and lower-class networks. The gaps are especially large in terms of contact status: upper middle-class individuals have networks whose contacts average 62.5 points, while those of members of the poor/precariat are as low as 41.8 points.

Table 1. Access to social capital and network composition by social class and spatial cluster

Inequality in access to social capital is also noticeable across the spatial structure. shows that the average number of contacts of those people who reside in affluent areas is 28.9, while those living in marginalized areas have approximately 15.5 contacts. Differences in contact variety are also relevant. Those living in affluent areas have, on average, access to 7.3 occupations through their connections, whereas those living in the most spatially disadvantaged area have access to 5.2 occupations. The differences in contact status are even more noticeable. Residents of affluent areas have social networks whose contacts average 61.6 prestige points – the most prestigious networks across the spatial structure. Average contact status drops to approximately 51.6 and 50.2 points among residents of mixed and middle-class areas, respectively. Those living in lower-class and marginalized areas average 45.3 and 41.6 points, respectively. As such, the urban poor exhibit the lowest social capital in terms of accessed prestige.

When analyzing network composition, we see that people from the highest and lowest classes have more homogenous networks than do those from the middle classes: on average, the upper middle class reported 54.1% similar-class contacts, while the poor/precariat have slightly more similar-class contacts, at 56.5%. More interestingly for our purposes, we observed clear indications that spatial segregation is associated with network homogeneity. Residents of affluent areas have social networks that include 51.7% high-status contacts, while people living in marginalized areas with a high concentration of poverty have networks in which 53.3% of contacts are low status. Conversely, residents of mixed areas have the most balanced (heterogeneous) networks. This strong social adjustment between residential segregation (both concentrated wealth and poverty) and network homogeneity is perhaps the most relevant result found in the Chilean data.

Explanatory analyses

We estimated a series of multilevel regression models for access to social capital and homogeneity of network resources in order to examine whether the differences described above remain stable when class and spatial structures are analyzed together, and control variables are included in the models. These multivariate analyses allow us to provide a clear indication of whether the spatial structure is associated with inequality in access to social capital and homogeneity of network resources beyond social class.

Inequality in social capital across the spatial structure

We begin by interpreting the results for the traditional indicators regarding access to social capital summarized in , starting with an analysis of the number of contacts accessed. Models 1 and 2 show that both social class and the spatial structure are significantly related to network size when included separately. When all variables are considered together in Model 3, our results indicate that respondents from the upper middle class and the established middle class have, on average, 14 and 11 more contacts in their social network, respectively, whereas the poor/precariat have, on average, access to 7 fewer contacts than those from the emerging middle class (the reference). In this last estimate, we see that social class clearly reduces the spatial “effects” previously reported in Model 2 and, more importantly, that the spatial structure loses statistical significance as a predictor of network size. This indicates that space does not produce additional differences after accounting for social class.

Table 2. Multilevel regression models for social class and spatial structure on access to social capital

Regarding our second measure, Model 1 shows that the higher the social class position, the higher the contact variety, whereas Model 2 indicates that living in marginalized areas is negatively related to greater occupational variety in contacts. Our final estimate (Model 3) incorporates both class and spatial structures simultaneously and shows that respondents from the upper middle class and the established middle class have access to 1.4 and 1.2 more occupations, whereas those from the poor/precariat and the working class have access to 1.6 and 0.7 fewer occupations than members of the upper middle class (the reference). Although social class accounts for most of the influence of the different spatial clusters on contact variety, living in marginalized areas significantly reduces residents’ contact variety (by a little less than 1 accessed occupation).

There are also substantial differences in access to more socio-economically valuable contacts (contact status) according to social class and the spatial structure. Model 1 indicates that social class strongly determines contact status, with upper-class individuals forming more prestigious networks. Model 2 shows that spatial divisions of poverty and wealth are also highly relevant to explaining contact status, with affluent areas related to higher social prestige and spatial deprivation linked to lower social prestige when compared to middle-class areas (the reference). When class and spatial structures are included together in Model 3, we see that individuals from the upper middle class and established middle class have networks that are around 9.4 points and 4.5 points more prestigious, respectively, whereas those from the poor/precariat and the working-class form networks that are 5.4 and 2.1 points less prestigious, respectively, than those of emerging middle-class individuals (the reference). Although there is a clear overlap between class and spatial “effects”, the spatial structure of Santiago remains an important predictor of contact status. Specifically, residence in affluent areas is significantly associated with more prestigious networks compared with residence in other spatial clusters, while living in marginalized areas significantly lowers people’s access to prestigious networks, regardless of their own social class.

In summary, although individuals’ social class is the most relevant predictor of social capital in the three measures considered, we found that the spatial structure plays an additional role in explaining access to high-status contacts. These findings are illustrated in , where predicted values by class and spatial structure are graphically presented for all last estimates. In effect, we see the importance of class in access to social capital, but also how the spatial structure produces additional differences in contact status. Specifically, while expected network prestige for respondents living in affluent neighborhoods is approximately 56.9 points, it drops to 52.1 points for those living in mixed areas, 49.3 points for those living in middle-class areas, 45.4 points for those living in lower-class areas, and 44.1 points for those living in marginalized areas. These stark differences produced by the spatial structure indicate that although mixed areas might provide opportunities to socialize with high-status contacts, spatial segregation probably reinforces inequality in access to social capital, especially at either end of the spatial spectrum.

Figure 2. Relationship between class/spatial structures and access to social capital

(a). Number of contacts by social class. (b). Contact variety by social class. (c). Contact status by social class. (d). Number of contacts by spatial cluster. (e). Contact variety by spatial cluster. (f). Contact status by spatial cluster. Predictive estimates with 95% confidence intervals.

Network homogeneity across the spatial structure

Finally, we present the results for the analyses of network composition, i.e. the proportion of high-status, medium-status, and low-status contacts in residents’ social networks. As shown in , class and spatial structures are clearly relevant in determining the proportion of high-status contacts in social networks. Model 1 indicates that the higher the social class, the higher the proportion of high-status contacts, whereas Model 2 shows that living in affluent areas significantly increases the proportion of high-status contacts. Our final estimate (Model 3) includes class and spatial structures simultaneously and illustrates that both factors are relevant predictors of – or independently associated with – the proportion of high-status contacts in social networks. In terms of class differences, our last estimate indicates that people from the upper middle and established middle classes have, on average, 22.2 and 8.7 percentage points more high-status contacts in their social networks, respectively, than the emerging middle class (the reference), whereas those from the poor/precariat and the working class have 7.8 and 4.2 percentage points fewer. Regarding the spatial structure, Model 3 indicates that living in affluent areas implies 16.1 percentage points more high-status contacts in social networks compared to living in middle-class area (the reference), whereas living in lower-class and marginalized areas translates into 6.5 and 6.4 percentage points fewer.

Table 3. Multilevel regression models for social class and spatial structure on the proportion of high-, medium-, and low-status contacts in the social network

The results are less clear regarding the proportion of medium-status contacts in social networks. Model 1 indicates that people from the upper middle class and the poor/precariat have a significantly lower proportion of medium-status contacts, whereas Model 2 shows that living in both affluent and marginalized areas reduces the proportion of medium-status contacts in residents’ social networks. These associations remain in Model 3 when class and spatial structures are included simultaneously.

Regarding the explanation of the proportion of low-status contacts in social networks, Model 1 indicates that the lower the social class, the higher the proportion, whereas Model 2 shows that living in lower-class and marginalized areas is significantly and positively associated with the proportion of low-status contacts. When social class and spatial clusters are included simultaneously in Model 3, we see that class and spatial “effects” overlap, but both are independently associated with the proportion of low-status contacts in social networks. More precisely, individuals from the upper middle and established middle classes have, on average, 14.3 percentage points and 8.3 percentage points fewer lower-status contacts in their social networks, respectively, than emerging middle-class individuals (the reference), whereas those from the poor/precariat have a higher proportion (14.5 percentage points). With regard to the spatial structure, Model 3 shows that living in marginalized areas increases the proportion of low-status contacts by 12.3 percentage points, whereas living in affluent areas reduces the proportion by 7.2 percentage points. As such, the spatial structure reinforces homogeneity in network resources among the urban poor.

In summary, we have shown that social class and the spatial structure both explain the composition of social networks. In other words, the spatial structure determines the proportion of high- and low-status contacts in residents’ networks beyond social class, in particular at either end of the spatial structure. Again, we plotted the predicted values based on our last estimates (for the three variables) in order to graphically summarize the main results. In short, shows that social class produces clear differences in network composition. More interestingly for our purposes, the figure illustrates that the proportion of high-status contacts in residents’ social networks is significantly higher for respondents living in affluent areas (40.9%) than for individuals living in mixed areas (30.6%), middle-class areas (24.9%), lower-class areas (18.5%), and marginalized areas (18.4%). It can also be observed that the predicted proportion of low-status contacts in residents’ social networks for respondents living in affluent areas is around 28.1%, while among those living in mixed and middle-class areas it is around 32.5% and 35.3%, respectively. Higher proportions of low-status contacts in social networks are found for individuals living in lower-class areas (45.9%) and marginalized areas (47.7%).

Figure 3. Relationship between class/spatial structures and network homogeneity

Predictive estimates with 95% confidence intervals.

Taken together, these patterns suggest that the spatial segregation of Greater Santiago reinforces the status homogeneity of network resources for individuals living in marginalized and affluent areas, whereas in the city’s few mixed areas there seems to be more cross-class interaction.

Conclusions

In the present article, we sought to contribute to the understanding of the relationship between space, social capital, and network composition in terms of status homogeneity. We focused on Santiago, Chile, a city that is strongly segregated by social class. We theorized that spatial segregation, driven partly by neoliberal urbanism, would affect social capital, especially through the spatial divisions of poverty and wealth.

Our results revealed large differences in access to social resources across the spatial structure. They indicate that space complements and reinforces the well-known relationship between social class and social capital (e.g. Otero, Volker et al., Citation2021). Residents of marginalized areas have reduced access to social capital, especially in terms of contact variety and contact prestige, which is in line with earlier studies (e.g. Pinkster & Volker, Citation2009; Small, Citation2007; Van Eijk, Citation2010). Furthermore, we found that urban deprivation fosters network homogeneity or, more precisely, networks dominated by low-status contacts. This confirms prior research in Latin America (e.g. Link et al., Citation2017; Marques, Citation2015). Overall, this homogeneity is the most relevant feature in the explanation of why social networks contribute to sustaining poverty and social inequality (Espinoza, Citation1999). It suggests that the urban poor are socially isolated and lack potentially valuable connections for gaining useful information and getting ahead (Kaztman, Citation2001).

In addition, we have confirmed that the neighborhood acts as an “opportunity” for those individuals living in relatively privileged areas. Due to favorable spatial conditions, they have access to greater social capital – specifically, more resourceful and homogenous networks – than the rest. Indeed, living in affluent areas facilitates access to networks of high status and power, while ensuring social distance from the networks of those who are less advantaged. This suggests that the self-selection of more privileged groups in Santiago not only leads to greater neighborhood cohesion and better educational outcomes, as found by prior research (e.g. Méndez et al., Citation2021; Otero, Carranza et al., Citation2021), but also provides further opportunities for affluent residents to make valuable social contacts and forge parallel lives within the city. As such, rather than serving as a coping mechanism used in deprived areas to counter increasing structural disadvantage and urban marginality, our study indicates that social capital emerges strongly in affluent areas, arguably as a condition for the reproduction of privilege (e.g. Wiesel, Citation2019).

Although for most Latin American cities, including Santiago, the spatial division between marginalized and affluent areas is remarkably visible, the spatial structure is more complex than this duality. Most cities contain extensive middle-class residential environments that tend to be less segregated. In some contexts, there are also mixed neighborhoods where residents with different social class and ethnic backgrounds coexist, share public space, attend similar educational institutions, and use common means of transportation. In this regard, we have additionally found that the social networks of those living in mixed areas are more prestigious and include a higher proportion of high-status contacts than networks of individuals living in middle-class and lower-class areas. Mixed-area networks are also more balanced in terms of status, that is, they are more heterogeneous. This may be the case because central areas in Santiago, in which the social mix is more pronounced, have become increasingly colonized (or gentrified) by the established middle classes (e.g. López-Morales, Citation2016). If so, the inherently dynamic nature of gentrification, which typically happens in a staged progression, possibly leads the original population in these areas to be fully displaced and, as such, the (heterogeneous) networks now observed are likely to change in the future.

In sum, we found that the spatial structure (re)produces inequality in access to social capital above and beyond social class. Our findings additionally support that spatial segregation goes hand in hand with class homogeneity in networks, in particular at the extremes of the social spectrum. In the context of neoliberal urbanism, the affluent increasingly seal up their neighborhoods and arguably gain from the fact that most of their neighbors are similar to themselves. The urban deprived, however, suffer a different kind of social isolation, not only enduring minimal infrastructure and poor environmental conditions, but also scarce social resources that might enable them to escape their context and overcome their deprivation.

Our study has some limitations that should be mentioned here. First, although we used a wide variety of georeferenced data, we have not been able to explain the way in which the well-known spatial transformations of Greater Santiago have generated changes in the unequal distribution of social capital among residents. Another problem is our focus on networks both within and beyond residential environments, which meant that we could not establish the extent to which the social contacts in individuals’ networks are located within their specific neighborhood. Finally, we were unable to directly test the role of certain spatial forces in access to social capital, for example, the role of structural proximity or meeting places, neighborhood cohesion, and territorial stigma or reputation. Future studies that address these challenges may help to improve our understanding of the role of spatial segregation in the network boundaries that are forged between classes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies – COES.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. During these demonstrations, protestors symbolically renamed the square Plaza de la Dignidad (Dignity Square).

References

- Agostini, Claudio, Hojman, Daniel, Román, Alonso, & Valenzuela, Luis. (2016). Segregación residencial de ingresos en el Gran Santiago 1992 – 2002: Una nueva aproximación metodológica. EURE, 42(127), 159–184. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612016000300007

- Andreotti, Alberta, Le Galès, Patrick, & Moreno-Fuentes, Francisco. (2015). Globalised minds, roots in the city: Urban upper-middle classes in Europe. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Atkinson, Rowland. (2008). The flowing enclave and the misanthropy of networked affluence. In Talja Blokland & Mike Savage (Eds.), Networked urbanism: Social capital in the city (pp. 41–58). Ashgate.

- Auyero, Javier. (2015). The politics of interpersonal violence in the urban periphery. Current Anthropology, 56(S11), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1086/681435

- Bacqué, Marie-Hélène, Bridge, Gary, Benson, Michaela, Butler, Tim, Charmes, Eric, Fijalkow, Yankel, Jackson, Emma, Launay, Lydie, & Vermeersch, Stéphanie. (2015). The middle classes and the city. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Benson, Michaela. (2014). Trajectories of middle-class belonging: The dynamics of place attachment and classed identities. Urban Studies, 51(14), 3097–3112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013516522

- Borsdorf, Axel, Hidalgo, Rodrigo, & Vidal-Koppmann, Sonia. (2016). Social segregation and gated communities in Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires. A comparison. Habitat International, 54, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.033

- Bourdieu, Pierre. (1986). The forms of capital. In John Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

- Brain, Isabel, & Prieto, Joaquin. (2021). Understanding changes in the geography of opportunity over time: The case of Santiago, Chile. Cities, 114, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103186

- Brenner, Neil, & Theodore, Nik. (2002). Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism”. Antipode, 34(3), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00246

- Caldeira, Teresa. (2000). City of walls: Crime, segregation and citizenship in Sao Paulo. University of California Press.

- Caldeira, Teresa. (2009). Marginality, again?! International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(3), 848–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00923.x

- Caldeira, Teresa. (2017). Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global south. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816658479

- Contreras, Dante, Otero, Gabriel, Díaz, Juan, & Suárez, Nicolás. (2019). Inequality in social capital in Chile: Assessing the importance of network size and contacts’ occupational prestige on status attainment. Social Networks, 58, 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2019.02.002

- Cortés, Yasna. (2021). Spatial accessibility to local public services in an unequal place: An Analysis from patterns of residential segregation in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago, Chile. Sustainability, 13(2), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020442

- Dammert, Lucía. (2004). ¿Ciudad sin ciudadanos? Fragmentación, segregación y temor en Santiago. EURE, 30(91), 87–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612004009100006

- De Mattos, Carlos, Fuentes, Luis, & Link, Felipe. (2016). Mutations in the Latin American metropolis: Santiago de Chile under neoliberal dynamics. In Oriol Nel-lo & Renata Mele (Eds.), Cities in the 21st Century (pp. 110–126). Routledge.

- ELSOC. (2018). Estudio Longitudinal Social de Chile 2016. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0KIRBJ

- Espinoza, Vicente. (1999). Social networks among the urban poor: Inequality and integration in a Latin American city. In Barry Wellman (Ed.), Networks in the global village (pp. 147–184). Westview Press.

- Fainstein, Susan. (2010). The just city. Cornell University Press.

- Flap, Henk, & Volker, Beate. (2004). Creation and returns of social capital. Routledge.

- Garretón, Matías. (2017). City profile: Actually existing neoliberalism in Greater Santiago. Cities, 65, 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.02.005

- Gayo, Modesto, Otero, Gabriel, & Méndez, María-Luisa. (2019). Elección escolar y selección de familias: Reproducción de la clase media alta en Santiago de Chile. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 77(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2019.77.1.17.310

- Hidalgo, Rodrigo. (2019). La vivienda social en Chile. La construcción del espacio urbano en el Santiago del siglo XX. Colección de Estudios Urbanos UC – RIL Editores – Instituto de Geografía UC.

- Hidalgo, Rodrigo, Santana, Luis, & Link, Felipe. (2019). New neoliberal public housing policies: Between centrality discourse and peripheralization practices in Santiago, Chile. Housing Studies, 34(3), 489–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2018.1458287

- Hill, Jessica, Jobling, Ruth, Pollet, Ruth, & Nettle, Daniel. (2014). Social capital across urban neighborhoods: A comparison of self-report and observational data. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8(2), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099131

- Husson, François, Lê, Sébastien, & Pagès, Jérôme. (2011). Exploratory multivariate analysis by example using R. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Janoschka, Michael, & Salinas, Luis. (2017). Peripheral urbanisation in Mexico City. A comparative analysis of uneven social and material geographies in low-income housing estates. Habitat International, 70, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.10.003

- Janoschka, Michael, Sequera, Jorge, & Salinas, Luis. (2014). Gentrification in Spain and Latin America—a critical dialogue. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1234–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12030

- Kaztman, Rubén. (2001). Seduced and abandoned: The social isolation of the urban poor. Cepal Review, 75, 163–180. https://doi.org/10.18356/bfee741f-en

- Lin, Nan. (2001). Social Capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge University Press.

- Lin, Nan, & Erickson, Bonnie. (2008). Social capital: An international research program. Oxford University Press.

- Link, Felipe, Greene, Margarita, Mora, Rodrigo, & Martinez, Cristhian. (2017). Patrones de sociabilidad en barrios vulnerables: Dos casos en Santiago, Chile. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 27(3), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v27n3.42574

- Link, Felipe, Valenzuela, Felipe, & Fuentes, Luis. (2015). Segregación, estructura y composición social del territorio metropolitano en Santiago de Chile. Complejidades metodológicas en el análisis de la diferenciación social en el espacio. Revista De Geografía Norte Grande, 62, 151–168. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022015000300009

- Lomnitz, Larissa. (1977). Networks and marginality. Academic Press.

- López-Morales, Ernesto. (2016). Gentrification in Santiago, Chile: A property-led process of dispossession and exclusion. Urban Geography, 37(8), 1109–1131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1149311

- Maloutas, Thomas, & Pantelidou-Malouta, Maro. (2004). The glass menagerie of urban governance and social cohesion: Concepts and stakes/concepts as stakes. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(2), 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00528.x

- Marcuse, Peter. (2005). Enclaves yes, ghettos no. In David Varady (Ed.), Desegregating the city: Ghettos, enclaves, and inequality (pp. 15–30). State University of New York Press.

- Marques, Eduardo. (2015). Urban poverty, segregation and social networks in São Paulo and Salvador, Brazil. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1067–1083. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12300

- Márquez, Francisca, & Pérez, Francisca. (2008). Spatial frontiers and neo-communitarian identities in the city: The case of Santiago de Chile. Urban Studies, 45(7), 1461–1483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008090684

- Massey, Douglas. (1996). The age of extremes: Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography, 33(4), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061773

- Méndez, María-Luisa, & Gayo, Modesto. (2019). Upper middle class social reproduction: Wealth, schooling, and residential choice in Chile. Palgrave Pivot Series.

- Méndez, María-Luisa, Otero, Gabriel, Link, Felipe, López-Morales, Ernesto, & Gayo, Modesto. (2021). Neighbourhood cohesion as a form of privilege. Urban Studies, 58(8), 1691–1711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020914549

- Musterd, Sako, Marcińczak, Szymon, Van Ham, Maarten, & Tammaru, Tiit. (2017). Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geography, 38(7), 1062–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1228371

- Otero, Gabriel, Carranza, Rafael, & Contreras, Dante. (2021). Spatial divisions of poverty and wealth: Does segregation affect educational achievement? Socio-Economic Review (Online First). https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab022

- Otero, Gabriel, Méndez, María-Luisa, & Link, Felipe. (2021). Symbolic domination in the neoliberal city: Space, class, and residential stigma. Urban Geography (Online First). https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1887632

- Otero, Gabriel, Volker, Beate, & Rözer, Jesper. (2021). Open but segregated? Class divisions and the network structure of social capital in Chile. Social Forces (Online First). https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soab005

- Peck, Jamie, Theodore, Nik, & Brenner, Neil. (2013). Neoliberal urbanism redux? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12066

- Permentier, Matthieu, Van Ham, Maarten, & Bolt, Gideon. (2008). Same neighborhood different views? A confrontation of internal and external neighborhood reputations. Housing Studies, 23(6), 833–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030802416619

- Pinçon-Charlot, Monique, & Pinçon, Michel. (2018). Social power and power over space: How the bourgeoisie reproduces itself in the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(1), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12533

- Pinkster, Fenne, & Volker, Beate. (2009). Local social networks and social resources in two Dutch neighbourhoods. Housing Studies, 24(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030802704329

- Rotarou, Elena, & Sakellariou, Dikaios. (2017). Neoliberal reforms in health systems and the construction of long-lasting inequalities in health care: A case study from Chile. Health Policy, 121(5), 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.03.005

- Rözer, Jesper, & Brashears, Matthew. (2018). Partner selection and social capital in the status attainment process. Social Science Research, 73, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.03.004

- Savage, Mike, Bagnall, Gaynor, & Longhurst, Brian. (2005). Globalisation and belonging. Sage.

- Small, Mario. (2007). Racial differences in networks: Do neighborhood conditions matter? Social Science Quarterly, 88(2), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00460.x

- Snijders, Tom, & Bosker, Roel. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage.

- Taylor, Marcus. (2003). The reformulation of social policy in Chile, 1973-2001: Questioning a neoliberal model. Global Social Policy, 3(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680181030030010101

- Van Eijk, Gwen. (2010). Does living in a poor neighbourhood result in network poverty? A study on local networks, locality-based relationships and neighbourhood settings. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-010-9198-1

- Van Tubergen, Frank, & Volker, Beate. (2015). Inequality in access to social capital in the Netherlands. Sociology, 49(3), 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514543294

- Volker, Beate, Flap, Henk, & Lindenberg, Siegwart. (2007). When are neighbourhoods communities? Community in Dutch neighbourhoods. European Sociological Review, 23(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcl022

- Wacquant, Loic. (2008). Urban outcasts: A Comparative sociology of advanced marginality. Policy Press.

- Wacquant, Loic, Slater, Tom, & Pereira, Virgilio. (2014). Territorial stigmatization in action. Environment and Planning A, 46(6), 1270–1280. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4606ge

- Warr, Deborah. (2005). Social networks in a ‘discredited’ neighbourhood. Journal of Sociology, 41(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783305057081

- Wiesel, Ilan. (2019). Distinction, cohesion and the social networks of Australia’s elite suburbs. Urban Geography, 40(4), 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1500250

- Wilson, William. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press.