ABSTRACT

Despite controversy over the meaning of financialization, there are two major dimensions to understanding whether the city is financialized. This paper explores these dimensions in China, namely whether the Chinese city (increasingly) uses financial instruments to carry out its urban development tasks and whether the utilization of financial instruments imposes a financial logic on urban governance. Financing the Chinese city involves creating land collateral and financial vehicles, extending shadow banking, formalizing and securitizing local government debts, and “deleveraging” developers’ debts through urban redevelopment. Applying land instruments leads to financial securitization, showing a financial logic in operation. However, financializing the Chinese city is engineered by the state through its credit expansion to cope with the Global Financial Crisis and the ramifications of the entrepreneurial model of the “export-oriented world factory.” It is a state-led financial turn, in which the financial logic is imperative but may not occupy a central position.

Introduction

Despite its wide use, financialization is a fundamentally fragmented concept (Christophers, Citation2015). The concept is associated with three traditions: first, Arrighi (Citation1994) and later Krippner (Citation2005) consider the increasing dominance of financial institutions over non-financial institutions, that is, intensified financial involvement (Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016). Krippner (Citation2005) refers to the intensification of financial approaches as “a pattern of accumulation in which profit-making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production” (p. 14). Second, financialization is about the growing financial logic in economic governance, for example, shareholder or bondholder value (Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016). Third, financialization is seen as the expansion of the financial sphere into everyday lives, for example, lived realities of credit and debt (Kaika & Ruggiero, Citation2016).

Applying the concept to housing, Aalbers (Citation2017) provides the most comprehensive definition as “the increasing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, and measurements, and narratives, at various scales, resulting in a structural transformation of economies, firms” (p. 3). While the intensification of the financial process in urban development is noted as financialization, it is important to distinguish financing from financializing, as the former refers to financial sources while the latter implies a consequential turn triggered by using financial sources, appropriately in the sense of governance. This can be seen in Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016) study of the transformation of Detroit. They do not use the term “financing” but rather financializing, to illustrate the “financialization of American urban governance.” They describe this consequential “financial turn” as “compounding a shift toward entrepreneurial urban governance, cities now find themselves in an operating environment that has been constitutively financialized” (p. 235).

According to Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016):

‘financialization is taken to refer to a historic process of systematic financial intensification, which is reflected, inter alia, in an increased reliance on (and resort to) financial intermediation and financial engineering, along with a host of financial logics, metrics, and rationalities; in the empowerment of financial sector institutions and agents, including credit rating agencies, technocratic managers and overseers, bond market players, and legal advocates and arbitrators; and in the disciplinary roles played by shareholder-value pressures, capital-market interests’, and ‘the budgetary restraint’. (p. 237)

They contextualized Detroit in the post-crisis landscape of “debt-machine dynamics” in which bondholder value and financial gatekeepers play a dominant role.

The literature of financialization seems to suggest two major dimensions to understanding whether the city is financialized. This paper aims to explore these two major dimensions in the Chinese city. First, does the Chinese city tend to use and increasingly use financial instruments to carry out its urban development? The first dimension includes the assetization of the city, for example, converting land into an asset which can be treated in financial terms. We need to distinguish financialized approaches from “usual” development and consumer finance, for example, development loans and housing mortgages. Mortgage securitization in the US (Gotham, Citation2009) and institutional investors in rental markets in European cities (Fields & Uffer, Citation2016; Wijburg et al., Citation2018) are clear examples of treating housing in a financialized way. In the UK, although the government treats public land as a source for subsidizing housing development operation, such a policy led to land being financialized by the private sector (Christophers, Citation2017). Second, to what extent is the development logic of the Chinese city financialized? Illustrative cases would include Detroit and Atlantic City, the New Jersey casino capital, which are subject to austerity urbanism and debt-machine dynamics (Peck, Citation2017; Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016). Other cases suggest a more active role of the municipality in utilizing financial approaches (Ashton et al., Citation2016; Van Loon et al., Citation2018; Weber, Citation2010) with an apparent financial logic in governance. Similarly, in China, the need to refinance debts has been addressed by consequential waves of new financial methods. In this sense, we may find evidence that financial logic is operating.

The paper seeks to explore the above two dimensions. The next section will review the overall trend of treating the city as a financial asset and the consequential governance shift. Then, the stages of urban development and the history of financing Chinese cities are reviewed. The core section of this paper is an examination of processes and conduits in China’s urban financialization, including land collateral, local government financial vehicles (LGFVs), shadow banking, financializing local government debts, and the financialization of urban redevelopment. Following the discussion of financial instruments, financialization in China is argued as a state strategy of spatial fix. Finally, I revisit the meaning of financializing the Chinese city and conclude.

Financializing the city

Despite controversy over the exact meaning of “financialization” (Christophers, Citation2015), financializing the city can broadly include financial treatments of major components of the built environment: land (Christophers, Citation2017; Kaika & Ruggiero, Citation2016), housing (Aalbers, Citation2008; Fields, Citation2018; Fields & Uffer, Citation2016), and infrastructure (Ashton et al., Citation2016; Pike et al., Citation2019; Rutland, Citation2010; Weber, Citation2010). There is a long tradition of political economic studies on urbanization, land, and the city, dating back to Harvey’s (Citation1978, Citation1982) three capital circuits and the “urbanization of capital” – the shift from the primary to the secondary circuit as the spatial fix. While it is difficult to trace the actual capital flows, both Beauregard (Citation1994) and Christophers (Citation2010) provided indirect evidence of the “increasing financial role” in real estate development and an intensification of the economics of rent. For example, in the UK there has been a tendency of the growing financialization of property as “rentier capitalism – a capitalism, that is, that seeks to profit from rent rather than from direct productive activity” (Christophers, Citation2010, p. 106). Treating land as financial assets can be found in the process of “assetization” (Ward & Swyngedouw, Citation2018), namely using the asset to raise financial capital and in turn for profit making.

Recent studies on a variety of “residential capitalisms” (Schwartz & Seabrooke, Citation2009) provide an understanding of the concrete mechanisms of housing financialization in different capitalist societies. The home is seen as a safe-deposit box (Fernandez et al., Citation2016; Hofman & Aalbers, Citation2019). Applying the regulation perspective, Hofman and Aalbers (Citation2019) describe the combined effect of finance- and real estate-driven development in the UK, which relies on private housing debt – a form of privatized Keynesianism. In East Asia, property development plays a central role in the regime of capital accumulation (Haila, Citation2015; Shatkin, Citation2017; Smart & Lee, Citation2003). In China, Wu (Citation2015) examines the close association between the property boom and the use of properties by residents to counter inflation. He explains that property occupies a central position in post-reform development. The notion of real estate–driven development in the UK bears some similarity with the Chinese state in that not only has real estate development become an important sector driving economic growth but also the private consumption of housing has intrinsically promoted the overall feasibility of financialized development through pumping household savings into development finance and allowing further land value capture by a state–developer alliance (Wu et al., Citation2020).

Financializing through financial instruments

Financialization is achieved through global financial deregulation and liquidity, as shown in the financialization of housing (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016). A wide range of financial instruments has been applied in urban development, ranging from more macroeconomic urban development initiatives in the European Union (Anguelov et al., Citation2018) and urban tax increment finance (TIF) (Weber, Citation2010) to concrete project-level infrastructure leasing (Ashton et al., Citation2016; Pike et al., Citation2019). Rutland (Citation2010) reviewed the use of financial instruments such as asset-backed securities and REITs in urban redevelopment, linked to monetary policies on low interest rates, which facilitated the pool of capital for property purchase and development. The application of REITs has been widely documented, for example, in Brazil (Sanfelici & Halbert, Citation2019), Ireland (Waldron, Citation2018) and France (Wijburg, Citation2019). Fields (Citation2018) describes how securitizing the rental income of foreclosed homes created a new asset class. For some institutional investors, the long-term possession of rental housing is for value appreciation (Wijburg et al., Citation2018). In Brazil, the financialization of housing in the late 2000s was associated with a large-scale subsidized housing programme which facilitated the expansion of the housing market (Pereira, Citation2017). Tax incentives for real estate-backed securities and decreasing interest rates on public bonds fostered securitization and REITs. However, the extent of securitization is limited in Brazil as low-income housing is not mortgaged in the global capital market (Pereira, Citation2017). The financialization of low-income housing has been achieved through the state-supported commodification of housing extending the informal to the formal housing market.

In the United Kingdom, local councils establish Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) to deliver housing targets (Beswick & Penny, Citation2018) and sell public housing to subsidize councils’ operation costs (Christophers, Citation2017). While not intended to financialize the city, the outcome of selling public land provides a chance for private sector developers to utilize this land privatization and treat it as a financial asset (Christophers, Citation2017). For example, the Peel Group is able to use land for speculative financial mobilization (Ward & Swyngedouw, Citation2018). The local state either directly maximizes land rent through TIFs in the United States or supports landowners to maximize land rent in the United Kingdom, indirectly treating land as a financial asset (Harvey, Citation1982). In Belgium, the municipal corporation has been transformed into a more profit-oriented developer which serves as a financial instrument (Van Loon et al., Citation2018). In Canada, Canada Lands Company – a state owned enterprise, treats surplus public land as a financial asset (Whiteside, Citation2019). In short, these instruments can be in the sphere of either real state practices or state governance. Hofman and Aalbers (Citation2019) argue that “it was not either changing state practices and regulation or changing real estate practices and market making that enabled the shift to a finance- and real estate-driven regime of accumulation, but that these trends together have contributed to this shift” (original emphasis, p. 90). Therefore, we may need to examine both instruments deployed by the state and private sector mechanisms such as trusts and bonds. In China, for example, the state management system itself has been experiencing shareholder reform (Wang, Citation2015, see later elaboration).

Financializing as a governance shift

In a mega urban redevelopment project on the outskirts of Paris, Guironnet et al. (Citation2016) discovered that the local authority had relatively “uneven” (read “weak”) capacities in design negotiation, while investors’ expectations and rent-seeking motivations dominated the redevelopment process. They show that due to the limited capacities of the local authority, the development was increasingly managed through modern portfolio management theory as land assets were transferred to the private sector developer. Reacting to this rising role of investors, Theurillat, Vera-Büchel et al. (Citation2016) suggest that we have begun to see a “financialized city” where there has been a shift from the entrepreneurial city of the public sector to financial operators and investors in trading rooms according to financial performance. They not only reconfirm the earlier mega urban project literature that reveals the nature of the private sector but also hint at the new nature of late entrepreneurialism, which is best dissected by Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016), Peck (Citation2017), and Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016) suggest “a regime of financialized urbanism,” focusing on the meaning of financialization as governance change from entrepreneurial city strategies to financialized urban rules. In the case of Detroit, they emphasized “debt machine” dynamics and regard financialized urbanism as a continuation of entrepreneurial urbanism but with an important “financial turn,” because these entrepreneurial operations have been increasingly led by financial actors and instruments, following financial imperatives, rather than an entrepreneurial public sector. Through this “testbed for austerity models,” they illustrate the governing rationalities of US cities through the “invasive processes of financial colonization” in urban development, subject to bondholder-value pressures.

In the study of financialization of public land in the United Kingdom, Christophers (Citation2017) distinguishes the subtle yet significant difference between the treatment of land as financial assets and austerity governance which led to land financialization. He found that instead of treating land “as a financial asset per se by developing, letting, trading, actively speculating with,” “the state has rather enabled such a treatment to be generalized by strategically selling its land to actors that do treat land in such a way – actors, that is to say, in the private sector” (p. 63). Christophers (Citation2017) argues that “the UK state has manifestly contributed to the wider tendency for land to be ‘financialized’ by that private sector” (original emphasis, p. 81). But “the state has not itself treated its land as a financial asset” (p. 81). Instead, it has treated and evaluated public land as an operational asset. In other words, financialization does not occur through the state’s direct use of land as financial assets but rather as a consequential operation of entrepreneurial urbanism. This description better fits China’s “state entrepreneurialism” which has its own rationality beyond treating the city as a financial asset. But at the same time the Chinese state has to use market instruments to achieve its “strategic aims,” in this case coping with the severe impact imposed by the GFC. This calls for situating the Chinese state in global capitalism and the external environment upon which its accumulation regime depends after the open-door policy and globalization. Similar to Christophers (Citation2017), the logic of financialization does not dictate the use of land in China. As will be illustrated, the operation of the state’s credit expansion led to financialization as a by-product. In this sense, we argue that this is state-led financialization. In the United Kingdom, council-owned real estate companies are set up as SPVs, which, according to Beswick and Penny (Citation2018), shows “financialized municipal entrepreneurialism.” Alternatively, the state can more directly facilitate financial operations. In Spain, “the state also increasingly promotes land rents as a source of liquidity creation” (Yrigoy, Citation2018, p. 594), as the state helped with the reorganization of distressed assets as investment opportunities.

From commodification to financialization in China

In China, the topic of financialization is relatively new but there is a proliferating literature on China’s land development and land finance (Lin & Yi, Citation2011; Tao et al., Citation2010; Tian, Citation2015; Wu, Citation2019; Ye & Wu, Citation2014). The literature indicates that appropriation of rural land at a lower price with selling at a higher price in the land market in the cities contributes to local public finance, and hence to the notion of “land-based finance” (Huang & Chan, Citation2018; Lin & Yi, Citation2011) arises. Land-based finance is a key mechanism for infrastructure finance (Wu, Citation1999). Recent studies indicate the role of Urban Development and Investment Corporations (UDICs) in organizing land development and capturing land value (Huang & Chan, Citation2018; Feng et al., Citation2020; Jiang & Waley, Citation2020; Li & Chiu, Citation2018; Theurillat, Citation2017; Zhang & Wu, Citation2021). An important mechanism for land value capture is “industrial linkage and spillover” (Su & Tao, Citation2017). In this approach, the local government tries to sell land at a cheaper price to attract industrial development which boosts local GDP as a key performance indicator for local officials. At the same time, population growth creates a spillover demand for residential and commercial land. The local government then maximizes the land price through limited supply and competitive bidding. But the current literature has not paid sufficient attention to land collateral as a process of development finance mobilization (Wu, Citation2019). Besides recent attention to UDICs, Wang (Citation2015) examines the change in the role of the state in the process of financialization, suggesting the rise of the Chinese “shareholding state,” and refers to it as the financialization of economic management, because it is through the introduction of shareholder value that state asset management bodies become responsible for the management of state assets. The case of Central Huijin Investment Ltd, a gigantic central government financial corporation, embodies the formation of the Chinese shareholding state. Seen from this perspective, the financialization of the state is the “corporatization of its public sector” (Wang, Citation2015, p. 604).

Recent studies in China have begun to pay attention to the macroeconomic changes that set the conditions for the financialization of the Chinese economy. Bai et al. (Citation2016) find that the stimulus package was largely financed through off balance sheet operations by Local Government Financial Vehicles (LGFVs) that borrowed on behalf of local government. Chen et al. (Citation2020) point out the rapid growth of shadow banking activities after 2012 as a result of the four-trillion-yuan stimulus package, and suggest that “Chinese local governments financed the stimulus through bank loans in 2009 and then resorted to nonbank debt financing after 2012 when faced with rollover pressure from bank debt coming due” (p. 42). While these studies are not about urbanization and the built environment, they provide some insights into the context of structural changes. Specific to urban development, Shen and Wu (Citation2017) examined the development of new towns in Shanghai as a “space of capital accumulation” and confirm that land development in new towns contributed to Shanghai’s public finance. The development of critical infrastructure such as the transit-oriented development metro line to Songjiang uses financial instruments leveraged on property development. Hence transit infrastructure development is linked with property development (Shen & Wu, Citation2020; Wu, Citation1999).

China’s housing commodification was the prelude to financialization. Between 1979 and 1997, the initial stage was to introduce a market mechanism into housing development to solve housing shortages, which mainly encouraged the market approach to housing production. However, housing as a welfare benefit was not radically changed until the abolition of welfare allocation in 1998. In response to the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the second stage of commodification started. The Chinese government chose the housing market to boost domestic consumption and initiated the mass commodification of housing. That is, in-kind welfare housing allocation was suspended and all new housing had to be purchased from the housing market. Public housing was also privatized. Housing became a household asset for private consumption. Housing mortgages were introduced to support housing consumption. At this stage, housing development increasingly involved the financial approach, for example, using land as collateral to borrow development finance. Housing commodification established the Chinese real estate sector and turned it into a driver for economic development. Thus, land finance contributes to public finance.

The third stage started after the GFC in 2008. The fiscal stimulus package injected massive investment in infrastructure and property development, which led to a large-scale housing boom. However, credit expansion was based on land as major collateral (Feng et al., Citation2020; Wu, Citation2019). Faced with land appreciation, UDICs quickly mobilized capital for land development. They transformed from development agencies to local financial platforms (hence known as LGFVs) (Feng et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Pan et al., Citation2017; Wu, Citation1999). The debts incurred by UDICs, due to local government guarantees, created an alarming scale of local government debts. In order to refinance bank loans, financialization was adopted as a strategy. UDIC bonds (also known as “chengtou bonds”) are issued as corporate bonds, while municipal bonds formally allow the local government to utilize the capital market to finance its development projects. The introduction of these bonds started a process of securitization in China. Moreover, to control property speculation, the central government began to tighten housing finance. The suppression of housing finance channels has consequently driven developers to find alternative financial resources, which started a process of financialization of development finance. From this history from commodification to financialization, we can see that China’s financialization of urban development has been associated with external financial crises. In fact, financialization is a strategy adopted by the state to cope with the impact of financial crises. The question is whether there is a financial logic underneath the urban dynamics. The answer is partially yes, because once a new financial instrument has been introduced it creates its own contradictions and tensions, which demand a new fix in order to avoid financial risks. Thus, the introduction of financial instruments into China’s urban development does bring in an additional dimension for decision-making. But, as will be shown later, the process of financialization is constantly restrained or shifted with new waves of financialization.

Financializing the Chinese city: motivations and conduits

In this section, we discuss the new array of financial instruments introduced and the motivations that have compelled this. Specifically, we investigate how actions were taken and how refinancing the debt created by credit expansion imposed new logics of financialization.

Financing development to cope with the financial crisis: land collateral and financial vehicles

A widely known model for financing urban development in China is land finance. UDICs play a key role in implementing this land finance model. Land collateral is a specific form of land finance. Right after the establishment of a land leasing system in China, Shanghai experimented with the financial land model known as “virtual capital circulation.” The municipal government injected land into four development corporations in Pudong new district to be their assets. However, the land was not valued because of the absence of a land market. The municipal government supported the value of the land by presenting a fiscal budget–backed “cheque” to the bank, indicating that it was willing to buy back the land if the development failed. With this public finance backup, the four development corporations managed to obtain loans, organized land development, and generated a land profit to cover the loans. This was a rudimentary type of land collateral which has been widely replicated in China since then.

By using land as collateral, UDICs obtain land-based mortgages to carry out development tasks. However, the role of the UDIC as a development agency has experienced profound changes especially since the GFC (Wu, Citation2019). The function of financial instruments has been strengthened in response to credit expansion under the stimulus package. While land finance is widely known, the process of capital mobilization has been less scrutinized. The function of financialization is particularly important for a specialized kind of UDIC known as the “land reserve center.” Its function is almost entirely financial, representing the municipal government to acquire land and organizing land preparation leading to land sales. It is a local land agency but with an ambiguous status between public institution and enterprise. The land reserve center uses the model of “virtual capital circulation” to borrow bank loans with implicit or explicit government guarantees. The land reserve center is thus virtually an asset management company with privileged government status. The asset injected by the local government into the land reserve center is “reserve land.” The proportion of the use of reserve land to obtain land mortgages in total land mortgages has risen sharply, suggesting that the function of reserve land is for capital mobilization rather than land utilization. The reserve land is in fact a form of collateral based on local government guarantees rather than land ownership (because the land does not have salable property rights).

UDICs are state-owned enterprises supported by the local government to carry out urban development tasks (Feng et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Jiang & Waley, Citation2020). One of the earliest UDICs was Shanghai Municipal Investment Corporation (SMI) established in 1992. SMI managed to leverage financial resources with limited government financial input. Most UDICs borrow bank loans to fulfil infrastructure projects and land development. The loans are mortgaged on land injected by the local government as company assets. The revenue from land sales will eventually pay back the bank loan. This model of development is widely known as “land-leverage-infrastructure” (Tsui, Citation2011) or “rolling development” (Jiang & Waley, Citation2020). In this typical land-based finance approach, development aims to generate land profits (Lin & Yi, Citation2011; Su & Tao, Citation2017; Tao et al., Citation2010). However, the main role of UDICs has changed from development to financialization. The land reserve center, as mentioned earlier, illustrates well this financial function of land. This is important as the concern is not to generate profits but the mobilization of financial resources. This has become particularly important since 2008. The fiscal stimulus package provided credit but needed a physical collateral form to transform credit into investment funds. Huang and Du (Citation2018) stress the importance of land collateral and the role of LGFVs in the acquisition of land as an asset to obtain bank loans. It is in this stage of financialization that we began to see the linkage between land and finance.

Land is used as collateral to obtain investment rather than simply revenues for local public finance (Wu, Citation2019). After the GFC, land was not seen as a major approach for attracting manufacturing investment due to the rising cost of development and declining demand. What was important for local governments was to inject land as an asset into UDICs to finance infrastructure and urban development. This can be seen as an approach similar to assetization by private developers in the UK (Ward & Swyngedouw, Citation2018). Before the recent tightening of land policy, unserviced and underdeveloped land could be used as a reserve for bank loans. Since 2016 it has been forbidden to use untitled land as collateral for bank loans. In other words, the municipal government must allocate funding from the fiscal budget to acquire land and prepare the conditions ready for sale. Only when land receives a formal title can it be used as collateral. This change in land collateral policy is intended to restrain land speculation because in the booming land market the local government used unserviced land before there had been a proper appropriation procedure to obtain capital. The motivation was to wait for land value appreciation. This could become a self-fulfilling prophecy as more borrowed capital flowing into the land market boosted land prices.

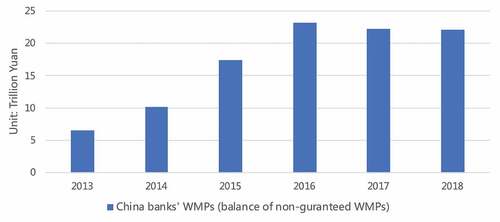

Refinancing the debt: the rise of shadow banking

To solve the financial pressure left by the stimulus package, since 2012, four years after the GFC, shadow banking was widely introduced, which started de facto financial liberalization. Wealth Management Products (WMPs) absorbed household savings at a higher interest rate than savings and invested in various UDIC projects. WMPs are opaque because they are off balance sheet, often without payback guarantees. shows the rapid growth of WMPs. Another shadow banking approach is the use of trusts. Through collaboration with trust companies, municipal governments obtained capital for their projects. Chen et al. (Citation2020) suggest that “the non-banking local government debt becomes increasingly significant relative to shadow banking activities in the overall Chinese economy, rising from 1.5% in 2008 to 48% in 2016” (p. 44). Other evidence for the linkage between excessive loans and shadow banking, according to Chen et al. (Citation2020), is that provinces with more bank loans took more entrusted loans in later years as a way of refinancing debt. They reported that in 2016, 62% or the equivalent of 4.2 trillion Yuan in chengtou bonds were invested by WMPs. The rise of shadow banking hence is a way to shift debts off balance sheets through converting bank loans to WMPs and entrusted loans. The problem is that public infrastructure projects may not have a constant and defined revenue, which adds to the financial pressure for UDICs to pay back their debts.

Figure 1. Growth of Wealth Management Products (WMPs) in China

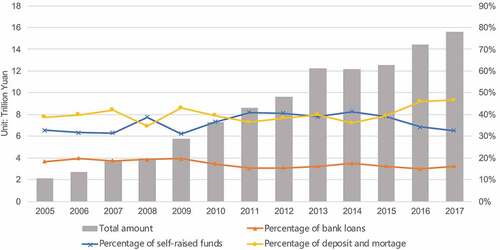

With increasing concern over financial risks, the central government began to control the housing market and has been tightening up on loans made available for developers since 2010. Developers in China have traditionally resorted to direct finance, that is, mainly bank loans. Faced with the tightening of direct finance, developers have begun to expand financial conduits in two ways. First, they use the housing presale system to absorb consumer credits and capital. The system, originated in Hong Kong and widely adopted on the mainland, allows developers to sell their properties to homebuyers as long as the project has met some initial construction conditions, for example, completing the foundation work. In terms of the volume of finance, in 2017 banks provided 8.32 trillion Yuan of formal development loans to developers, accounting for only 13% of total investment (). Mortgages provided 31% of the development finance, while down payments (deposits) accounted for 15%. Altogether consumer credit covered 46% of development finance. A major tactic of the “successful” developer is to create a quick turnover model, using bank loans to bridge the gap in development finance.

Second, the developer uses various financial conduits to “self-raise” the funds. Some may incur greater financial risk. Besides bank loans, developers use offshore/onshore corporate bonds or senior notes, joint ventures and strategic alliances, perpetual bonds, trust firms, P2P lending and crowdfunding, and finally REITS, although the last are in fact private equity funds rather than the standard public REITS (Jones Lang Lasalle [JLL], Citation2017). The so-called joint venture and “strategic alliance” may hide the nature of debt financing. The practice is known as “borrowing capital in the name of equity,” “debt in the name of equity,” or “fake equity, real debt” (minggu shizhai). The developer, in order to gain capital, signs an agreement with the lender for a fixed income (debt). The financial institution does not really participate in the joint venture or development operation. But these financial contributions need to be guaranteed by assets, often on the land, for paying back the “debt.” Because it is disguised as equity finance, the capital is not treated as a land mortgage. Most “self-raised funds” refer to these finance sources through financialized channels. The financialization of the development sector is a result of the combination of a unique housing presale system and a financial depression which suppressed the direct channel of development finance.

Financing local government debt: municipal bonds

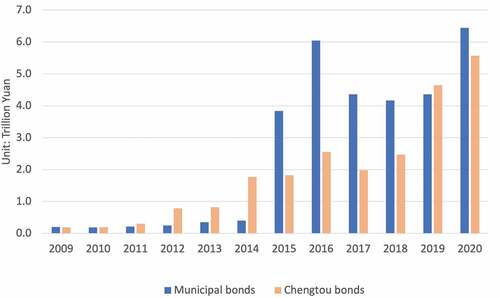

Faced with the financial pressures and risks brought about by shadow banking, the government adopted the policy to “close the back door and open the front door,” meaning that the conduits of off-balance borrowing between financial institutions and local governments were cut off, while a formal channel of securitized financing was created for local governments. In this process, UDICs are first separated from the local government and restored to the status of enterprises. The local government pays back its debt to UDICs for infrastructure development. UDICs are then financed by the corresponding chengtou bonds without government guarantees. To finance the local government debt, municipal bonds are securitized based on the local government’s fiscal budget (Chen et al., Citation2020). shows a significant increase since 2015 in municipal bonds (also known as “local government bonds”) as well as chengtou bonds.

Figure 3. The rise of bonds in local government finance in China

The policy started a new wave of financialization of local government debts. In fact, dating back to 2010, fearing heated growth and a rapid increase in local government debts, the central government began to enforce a stricter regulation of LGFVs’ borrowing and restrained the issuance of chengtou bonds. But in 2014, because of the pressure of rollover, these policies were relaxed, which enabled LGFVs to borrow from the bond market (Chen et al., Citation2020). Supported by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Finance (MoF), in 2014 and 2015 special local government bonds were created; in 2015, the local government debt–bond swap was formally launched to absorb local debts. This is known as the debt–bond swap programme (Theurillat, Lenzer et al., Citation2016). In 2016, No. 4 Decree of Finance Regulation Policy forbade enterprises to use bank loans or other financial instruments for land purchase. UDICs should be transformed into the status of enterprises without government guarantees. For the land reserve centers, the decree requires that all functions of capital mobilization and secondary land development should be transferred to other enterprises which are separate from government and that the land reserve center should maintain the status of a public agency that relies on the government budget for their development work. The policy restrains land reserve centers from acting as LGFVs.

Since 2015, there has been significant progress in financializing local government debts. Special local government bonds reached about 10 trillion Yuan and the debt-swap bond (zhihuan zhaijuan) amounted to 14 trillion Yuan (Ren, Citation2019). This means that besides hidden debts, through formal securitization Chinese local government debts were presented in a “hard” securitized form of nearly 27 trillion Yuan in 2019, accounting for about 30% of GDP (see ). Although special bonds only started in 2015, their scale has increased significantly. From 2015 to 2019, the annual issuance of special bonds increased from 0.10, 0.40, 0.80, 1.35 and to 2.15 trillion Yuan.

Figure 4. The composition of bonds for local government debts in 2018

In 2018 the China Bank Regulatory Commission (CBRC) promulgated No. 76 Decree to require the slowing down of deleveraging and allowing financial institutions to provide funding for qualified enterprises and financial platforms. The State Council issued No. 101 Document to allow reasonable support for financial platforms while continuing to forbid the raising of additional debts through government investment funds and other PPP projects. All these measures temporarily eased the pressure on LGFVs. In 2019, to rescue local financial enterprises in Zhenjiang in Jiangsu and Xiangtan in Hunan, which were in severe financial difficulty, the National Development Bank issued long-term bonds to swap for short-term debts. The central government, however, stressed that the central government would not be responsible for local government debts.

With nearly 27 trillion Yuan of local debts in the form of bonds together with a hidden debt, it was estimated that local government debts could reach 50 trillion Yuan (Ren, Citation2019); in comparison with a 90 trillion Yuan GDP with 11 trillion Yuan of public finance revenue, this means that the pressure on local governments is significant (Ren, Citation2019). In short, the new financial reform started the securitization of local government debts.

“Deleveraging” developers’ debt: financializing urban redevelopment

The real estate boom had led to unsold housing in small and medium cities (known as third- and fourth-tier cities). At the end of 2015, total unsold commodity housing reached 739 million square meters nationwide. This further created a high debt ratio among development companies which might further implicate state-owned banks. To cope with the increasing financial risk associated with the high debt ratios of development companies, in 2015 the Chinese government initiated a policy of reducing the unsold stock of housing (qukuchun) to “deleverage” developers’ debts.

The policy encouraged housing purchase by reducing the down payment requirement and housing transaction taxes. As the ratio of mortgage to household income was still relatively low in China, the policy de facto shifted the financial burden to the household sector. To realize this aim, large-scale urban redevelopment programmes were initiated, known as shantytown renewal (penggai) (He et al., Citation2020), which started another wave of financializing the Chinese city. More precisely speaking, this is the financialization of urban redevelopment. In 2017 it was announced that 15 million units would be developed from 2018 to 2020 (He et al., Citation2020). To reduce the financial pressure on real estate developers, the National Development Bank borrowed development capital based on its status of “policy bank” and provided funds to shantytown renewal projects. This in turn prevented the spread of risk toward the banking sector. After demolition, shantytown residents were given monetary compensation, encouraging them to buy new housing in these cities. This effectively raised the demand for housing and created a booming market which lured more residents to invest their own financial resources (Wu et al., Citation2020). As the debt of the household sector is considered safer in comparison with local government debt, the financialization of redevelopment is not aimed to recoup financial benefits for financial investors. This is part of the state effort to cope with earlier fiscal/credit expansion and its consequential financial risks and logics.

Financialization as a state strategy of spatial fix

Harvey’s (Citation1978) theory of capital circuits assumes the switch of capital flows between primary and secondary circuits. His capital switching theory depends on the declining rate of profitability as a symptom of over-accumulation. The role of the state in this process of capital switching is implied but has not been explicitly addressed in his description of the dynamics. While the role of the state in enabling financialization has been widely recognized (Gotham, Citation2009; Pike et al., Citation2019; Weber, Citation2010; Whiteside, Citation2019), the operation of financialization remains a black box (Christophers, Citation2017). In the United Kingdom, land financialization is a side effect of local state operations, while in Canada the state explicitly treats surplus public land as financial assets and operates through financial approaches (Whiteside, Citation2019).

The Chinese case shows that financialization is a strategy deliberately adopted by the state to cope with the impact of external financial crises. The strategy can be characterized as credit expansion leading to investment-driven development. The evidence for credit expansion is the growth of broad monetary supply (M2). In 2018 M2 reached 182.7 trillion Yuan, at a ratio of 202.9% to GDP. That is, M2 is twice GDP. The inflow of foreign direct investment in the 2000s fueled and provided a base for monetary supply. The expansion of credit after 2008 was a conscious effort to use the built environment to support credit expansion and in turn create a new space for capital accumulation. Because of the shrinkage of the export market during the financial crisis, export-oriented manufacturing industries faced severe constraints. Credit expansion was realized through investment in fixed assets. Investment in fixed assets as a percentage of GDP rose from 24% in 1990 to 41% in 2005, 56% in 2007, 65% in 2009 and 80.2% in 2016, but declined to 70.6% in 2018 due to the slowdown of the economy and the marginal decline of the credit effect.

These figures for both monetary supply and investment in fixed assets showed significant expansion until recently, providing indirect evidence for continuing capital flow into the built environment. However, this capital flow needs to overcome various institutional and financial barriers. First, the Chinese budgetary law did not allow local governments to resort to direct financing in the capital market until the recent introduction of municipal bonds. Second, distributing credit into investment in fixed assets requires local government matching funds in investment, which is achieved through a process of financialization. The expansion of monetary supply and consequential asset inflation are two sides of the same coin. It is because of the financialization of the city that the strategy of monetary supply and credit expansion could be fulfilled. On the other hand, because of credit expansion, the financialized asset experiences asset value inflation and hence makes financialization into a new channel for profit making. In other words, financialization means a process that such profit making is not limited to production and trade but is able to use financial conduits (Kripper, Citation2005). In China, the expansion of the monetary supply is indigenously generated rather than being a global source of capital seeking investment opportunities in China (Aalbers, Citation2008; Hofman & Aalbers, Citation2019). From the perspective of credit creation, this is due to financialization (especially turning underdeveloped land into financial assets through collateralization). Without housing commodification and land development financialization, the expansion of credit would be difficult. Similar to the notion of the built environment as an outlet for capital circulation, space now serves as a huge “pool for capital” to be stored for value appreciation. Because of this capital pool, credit supply becomes new investment in development projects, and such investment expects a future economic return as a result of this financialized logic. It is in this sense that financialization becomes a strategy of spatial fix.

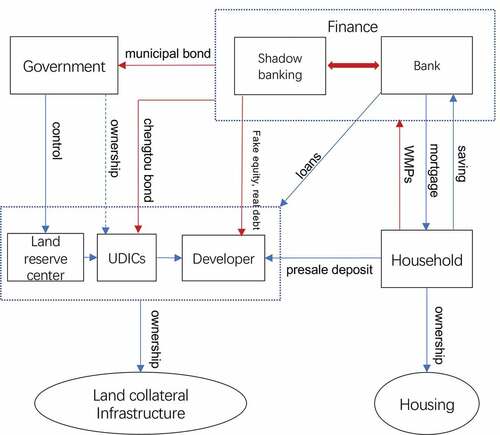

This paper not only highlights the state role but also reveals complex motivations (financing development, refinancing debt, deleveraging financial risks) and maneuvers. illustrates the actual conduits in the aftermath of financialization. Besides the conventional direct finance which characterized the Chinese financial system, new securitized and financialized conduits are formed, including land and housing mortgages, municipal bonds, chengtou bonds and WMPs.

Conclusion

Through (regulated) financial deregulation, the built environment (and more specifically housing) absorbs surplus global capital, according to the literature of housing financialization (Aalbers, Citation2008). This is a consumer-led financialization of housing. In the literature, extensive attention has been paid to the creation of new financial markets through making financial technological changes (Aalbers, Citation2017). Mortgage securitization was a key mechanism leading to the subprime mortgage crisis in the US (Gotham, Citation2009). More recently, the entry of private equity firms, hedge funds, publicly listed real estate firms and REITs into rental markets (Fields & Uffer, Citation2016; Wijburg et al., Citation2018) have been examined. The adoption of new financial instruments in infrastructure, for example, SPVs and TIF, has led to the financialization of public finance (Pike et al., Citation2019; Weber, Citation2010). Further, large developers resort to a financialized approach to create supply-side financialization, which Ward and Swyngedouw (Citation2018) refer to as “assetization.” This paper has identified a series of financial practices, similar to these new financial technologies and instruments, that have led to the transformation of the Chinese city and its governance. One critical trend suggested by the literature is the waves of neoliberalization as governance changes and financialization following the entrepreneurial turns in the 1980s, reflecting austerity urbanism (Peck, Citation2017). In response to the GFC, the Chinese government mobilized massive infrastructure projects and later large-scale shantytown renewal. It was speculated that the Chinese state would make a turn to Keynesianism after Deng Xiaoping’s growth-oriented market entrepreneurialism. However, rather than the restoration of state redistributive policies, the state initiated the stimulus package and adopted consequential financialization approaches to cope with both the externally imposed crisis and internal contradictions (under-consumption, investment-driven, export-oriented development, with comparatively limited domestic consumption). In this respect, the Chinese turn to financialization shows some similarities to the evolution of urban entrepreneurialism in a more crisis-laden globalized world. Despite some local specificities, this article has identified the deployment of a diverse range of financial operations and instruments and their pervasive use as evidence of the financialization of the city. As seen in Detroit where financialization comes from a set of neo-conservative austerity sensibilities, the financialization of urban development in China similarly consists of a range of financial operations, albeit in the form of financial expansion rather than austerity. Both have seen the shift from earlier entrepreneurial governance to a rising financial logic. Yet, the process of financialization is enabled, encouraged, and mediated by the state in the context of strong state capacities, conjunctural global crises, and the challenges of crisis management. Because of the particularities of Chinese context, the financial logic is necessarily intertwined with the territorial logic and state operations and thus is less deterministic.

Regarding the second question as to whether there is a financial logic or even a financial turn in governance, the answer is a partial yes as the financial imperative is salient. However, it is not superimposed externally but is rather a by-product of the operations of the state, namely a pro-active credit expansion and the utilization of financial instruments to implement investment-driven development. In terms of the relationship between the state and financial sector, the rationale of financialization is internalized. That is, the state applies the financial principle during its operation but is not “captured” by the financial sector. After all, the Chinese financial sector is dominated by state-owned banks. The logic is seen as a fix, a short-term solution, but necessary to satisfy practical financial needs. We have seen waves of financial instruments, shadow banking and more recently formal securitization. In addition, a series of policies have been formulated to regulate the process of financialization due to concern over financial risks. Despite the very important role of the state in creating financialization conditions, similar to “budgetary restraint” (Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016), a more stringent financial discipline has been imposed on shadow banking and state financial platforms (Feng et al., Citation2021; Pan et al., Citation2017) and at the same time has resulted in the deleveraging of the debt ratio of development enterprises and the shifting of the financial burden from developers to households. The introduction of more formal finance through municipal bonds and corporate bonds, which it is hoped will follow the rules of the capital market, thus separates government and enterprise debts. With very high local government and enterprise debt (see 2018 figures mentioned earlier) in China compared with relatively high household debt in more developed market economies, the application of financial logic is seen as an imperative imposed by the state rather than external bondholders.

Financializing the Chinese city occurs in the context of financial depression and stronger state control, meaning an artificially low interest rate of savings; lower levels of government being unable to resort to the capital market to fund infrastructure development or public services; and finally an underdeveloped capital market. Due to economic growth and the accumulation of household wealth, bank savings are a major form of financial sources. Housing commodification introduced housing as a private consumption item. But the effect of assetization has become more visible since the GFC (Wu et al., Citation2020). Households are willing to endure financial burdens to divert savings into housing assets and borrow increased mortgages (including the Housing Provident Fund). Through the housing presale system, household finance is a major source for real estate development. The state has used credit expansion to achieve its strategic aims (for example, to cope with the impact of the external financial crisis). The state does not directly distribute additional fiscal funds but rather uses credit expansion. As a result, market instruments (including various financial conduits) have to be used to materialize credit expansion into the development of the built environment. UDICs are increasingly transformed from development agencies to a form of financial vehicle (hence LGFVs). Similarly, the “government-guided investment fund” uses the form of an equity fund but the purpose is to realize the intention to upgrade industries (Pan et al., Citation2020). While the terms LGFV and UDIC are often used interchangeably, the financial function has become more salient since the GFC (Feng et al., Citation2021). The imperative of financialization also originates from the consequent financial operation to reschedule debts, which became the prelude to the financialization of the city. Echoing Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016), financializing the Chinese city is a governance innovation (using shadow banking off the bank’s balance sheet, creating land collateral to create credit, using LGFVs to materialize the credit, and using household finance to deleverage developers’ debts).

Reflecting on the limits of financialization, Christophers (Citation2015) argues the need to consider the limitation of financialization as a concept in two aspects. First, we need to consider “constitutive sociospatial others/outsides that may not be immediately visible to researchers in the ‘core’, but which are no less material for that” (p. 198). So far, extensive attention has been paid to shareholder and bondholder value but not to the state itself. As shown in the Chinese case, financialized agents such as UDICs are “market instruments” invented or utilized by the state (Feng et al., Citation2021; Wu, Citation2018, Citation2020). They are transformed into local government finance vehicles in response to conditions created by the state, and are more indigenously grown, as shown by their legal nature as “state-owned enterprises.” They are the long shadow of the state. Second, Christophers (Citation2015) reminds us that, while attending to the forces that propel financialization, “it is imperative also to consider counter forces and the limits to financialization they impose” (p. 198). Given that the process of financialization is state-led, these same forces can limit, transform, shift or de-financialize the process of financialization. The Chinese state started the process from a rational position inside its own internal logic and the contradictions of the “export-oriented world factory” and the external conditions of the GFC. Over time, with new contradictions of alarming local government debts and financial risks, the same forces could separate government debts from enterprise debts to de-financialize municipal governments, closing the opaque conduits of shadow banking, while “opening the front door” of financialization through municipal bonds, “deleveraging” the debt ratio of developers, and shifting the focus of financialization to households. Here, Chinese urban financialization reveals great flexibility and complex motivations.

Emphasizing that Detroit is “never a typical place,” Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016, p. 263) aim to reveal “the systemic character of the forces that have been driving the city’s restructuring.” They stress that financialization reflects a “transformative urban process.” In a similar vein, this article builds upon recent extensive studies on China’s entrepreneurial governance (Wu, Citation2018, Citation2020) to reveal the origin of this “urban process” in China’s post-reform political economy. The financial logic has been created and superimposed by the more strategic considerations of the state. In this sense, this urban process reveals the financial imperatives of state financial operations, but not yet a fully “financialized form of capitalism.” In other words, precisely because financialization is a long shadow of the state, Chinese cities retain some characteristics of state-centered operation, although Chinese cities demonstrate some characteristics of “financialized urban development.” In a forthcoming special issue in Land Use Policy, the full spectrum of these operations including waterfront regeneration and chengtou as state investment arms is examined. Financializing the city is led and constrained by the financial operations of the state – or “spatial-temporal fixes” (Harvey, Citation1978).

Returning now to Harvey’s (Citation1982) original notion of “treating land as a financial asset” as a fundamental indicator of financializing the city, our question is: by whom? We can see that in the post-reform Chinese political economy, land has been assetized (creating land collateral) and there is the consequential operation of land value capture to finance urbanization (Feng et al., Citation2021; Wu, Citation2019). Similar to the important role of the state in the financialization of public land in the UK (Christophers, Citation2017), the Chinese state creates an accompanying financial logic when it strives to deploy financial instruments. But an understanding of the question of “whom” – to treat the land according to its economic rent – would reveal the characteristics of financialization under “state entrepreneurialism” (Wu, Citation2018, Citation2020) as using financial instruments built upon the city as a financial asset to achieve strategies in which the financial logic is inevitably imperative but may not occupy a central position.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the funding support from UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) on the project entitled ‘The financialisation of urban development and associated financial risks in China’ (ES/P003435/1) and European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant No. 832845 – ChinaUrban. The paper was presented as Urban Geography Public Lecture in the Annual Meeting of American Associations of Geographers. April 2021. I thank Kevin Ward and David Wilson for their invitation, Anne Bonds for chairing the session, two discussants Manuel Aalbers and Heather Whiteside for their insightful comments, and Yi Feng for research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalbers, Manuel B. (2008). The financialization of home and the mortgage market crisis. Competition and Change, 12(2), 148–166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/102452908X289802

- Aalbers, Manuel B. (2017). Corporate financialization. In Douglas Richardson, Noel Castree, Michael F. Goodchild, Audrey Kobayashi, Weidong Liu, & Richard A. Marston (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology (pp. 1–11). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ang, A., Bai, J., & Zhou, H. (2016). The great wall of debt: Real estate, political risk, and Chinese local government financing cost. Georgetown McDonough School of Business Research Paper No. 2603022. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2603022

- Anguelov, Dimitar, Leitner, Helga, & Sheppard, Eric. (2018). Engineering the financialization of urban entrepreneurialism: The JESSICA urban development initiative in the European Union. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12590

- Arrighi, Giovanni. (1994). The long twentieth century: Money, power, and the origins of our times. Verso.

- Ashton, Philip, Doussard, Marc, & Weber, Rachel. (2016). Reconstituting the state: City powers and exposures in Chicago’s infrastructure leases. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1384–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014532962

- Bai, Chong-En, Hsieh, Chang-Tai, & Song, Zheng Michael. (2016). The long shadow of a fiscal expansion. National Bureau of Economic Research, Paper No. 22801, 1–45.

- Beauregard, R.A. (1994). Capital switching and the built environment: United States, 1970-89. Environment and Planning A, 26(5), 715–732. https://doi.org/10.1068/a260715

- Beswick, Joe, & Penny, Joe. (2018). Demolishing the present to sell off the future? The emergence of ‘financialized municipal entrepreneurialism’ in London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 612–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12612

- Chen, Zhuo, He, Zhiguo, & Liu, Chun. (2020). The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes. Journal of Financial Economics, 137(1), 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.07.009

- Christophers, Brett. (2010). On voodoo economics: Theorising relations of property, value and contemporary capitalism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(1), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00366.x

- Christophers, Brett. (2015). The limits to financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615588153

- Christophers, Brett. (2017). The state and financialization of public land in the United Kingdom. Antipode, 49(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12267

- Feng, Yi, Wu, Fulong, & Zhang, Fangzhu. (2020). The development and demise of Chengtou as local government financial vehicles in China: A case study of Jiaxing Chengtou. Land Use Policy, 104793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104793

- Feng, Yi, Wu, Fulong, & Zhang, Fangzhu. (2021). Changing roles of the state in the financialization of urban development through chengtou in China. Regional Studies, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1900558

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2016). Financialization and housing: Between globalization and varieties of capitalism. Competition & Change, 20(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529415623916

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, Hofman, Annelore, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and Planning A, 48(12), 2443–2461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16659479

- Fields, Desiree. (2018). Constructing a new asset class: Property-led financial accumulation after the crisis. Economic Geography, 94(2), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1397492

- Fields, Desiree, & Uffer, Sabina. (2016). The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1486–1502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014543704

- Gotham, Kevin Fox. (2009). Creating liquidity out of spatial fixity: The secondary circuit of capital and the subprime mortgage crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(2), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00874.x

- Guironnet, Antoine, Attuyer, Katia, & Halbert, Ludovic. (2016). Building cities on financial assets: The financialisation of property markets and its implications for city governments in the Paris city-region. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1442–1464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015576474

- Haila, Anne. (2015). Urban land rent: Singapore as a property state. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Harvey, David. (1978). The urban process under capitalism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 2(1–3), 101–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.1978.tb00738.x

- Harvey, David. (1982). The limits to capital. Blackwell.

- He, Shenjing, Zhang, Mengzhu, & Wei, Zongcai. (2020). The state project of crisis management: China’s Shantytown Redevelopment Schemes under state-led financialization. Environment and Planning A, 52(3), 632–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19882427

- Hofman, Annelore, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2019). A finance- and real estate-driven regime in the United Kingdom. Geoforum, 100, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.014

- Huang, Dingxi, & Chan, Roger CK. (2018). On ‘land finance’ in urban China: Theory and practice. Habitat International, 75, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.03.002

- Huang, Zhonghua, & Du, Xuejun. (2018). Holding the market under the stimulus plan: Local government financing vehicles’ land purchasing behavior in China. China Economic Review, 50, 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2018.04.004

- Jiang, Yanpeng, & Waley, Paul. (2020). Who builds cities in China? How urban investment and development companies have transformed Shanghai. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(4), 636–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12918

- Jones Lang Lasalle [JLL]. (2017). Financing China’s real estate: Pragmatism and creativity will prevail.

- Kaika, Maria, & Ruggiero, Luca. (2016). Land financialization as a ‘lived’ process: The transformation of Milan’s Bicocca by Pirelli. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413484166

- Krippner, Greta R. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008

- Li, Jie, & Chiu, LH Rebecca. (2018). Urban investment and development corporations, new town development and China’s local state restructuring – The case of songjiang new town, Shanghai. Urban Geography, 39(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1382308

- Lin, George. C. S, & Yi, Fangxin. (2011). Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land? Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geography, 32(1), 50–79. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.32.1.50

- Pan, Fenghua, Zhang, Fangzhu, & Wu, Fulong. (2020). State-led financialization in China: The case of the government-guided investment fund. The China Quarterly, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741020000880

- Pan, Fenghua, Zhang, Fengmei, Zhu, Shengjun, & Wójcik, Dariusz. (2017). Developing by borrowing? Inter-jurisdictional competition, land finance and local debt accumulation in China. Urban Studies, 54(4), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015624838

- Peck, Jamie. (2017). Transatlantic city, part 2: Late entrepreneurialism. Urban Studies, 54(2), 327–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016683859

- Peck, Jamie, & Whiteside, Heather. (2016). Financializing Detroit. Economic Geography, 92(3), 235–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1116369

- Pereira, Alvaro Luis Dos Santos. (2017). Financialization of housing in Brazil: New frontiers. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 604–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12518

- Pike, Andy, O’Brien, Peter, Strickland, Tom, & Tomaney, John. (2019). Financialising city statecraft and infrastructure. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ren, Tao. (2019). Special report on local government debts. Sina. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from finance.sina.com.cn

- Rutland, T. (2010). The financialization of urban redevelopment. Geography Compass, 4(8), 1167–1178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00348.x

- Sanfelici, Daniel, & Halbert, Ludovic. (2019). Financial market actors as urban policy-makers: The case of real estate investment trusts in Brazil. Urban Geography, 40(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1500246

- Schwartz, Herman M, & Seabrooke, Leonard (Eds.). (2009). The politics of housing booms and busts. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shatkin, Gavin. (2017). Cities for profit: The real estate turn in Asia’s urban politics. Cornell University Press.

- Shen, Jie, & Wu, Fulong. (2017). The suburb as a space of capital accumulation: The development of new towns in Shanghai, China. Antipode, 49(3), 761–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12302

- Shen, Jie, & Wu, Fulong. (2020). Paving the way to growth: Transit-oriented development as a financing instrument for Shanghai’s post-suburbanization. Urban Geography, 41(7), 1010–1032. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1630209

- Smart, A., & Lee, J. (2003). Financialization and the role of real estate in Hong Kong’s regime of accumulation. Economic Geography, 79(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00206.x

- Su, Fubing, & Tao, Ran. (2017). The China model withering? Institutional roots of China’s local developmentalism. Urban Studies, 54(1), 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015593461

- Tao, Ran, Su, Fubing, Liu, Mingxing, & Cao, Guangzhong. (2010). Land leasing and local public finance in China’s regional development: Evidence from prefecture-level cities. Urban Studies, 47(10), 2217–2236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009357961

- Theurillat, Thierry. (2017). The role of money in China’s urban production: The local property industry in Qujing, a fourth-tier city. Urban Geography, 38(6), 834–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1184859

- Theurillat, Thierry, Lenzer, James H, Jr, & Zhan, Hongyu. (2016). The increasing financialization of China’s urbanization. Issues & Studies, 52(4), 1640002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1013251116400026

- Theurillat, Thierry, Vera-Büchel, Nelson, & Crevoisier, Olivier. (2016). Commentary: From capital landing to urban anchoring: The negotiated city. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1509–1518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016630482

- Tian, Li. (2015). Land use dynamics driven by rural industrialization and land finance in the peri-urban areas of China: The examples of Jiangyin and Shunde. Land Use Policy, 45, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.01.006

- Tsui, Kai Yuen. (2011). China’s infrastructure investment boom and local debt crisis. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 52(5), 686–711. https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.52.5.686

- Van Loon, Jannes, Oosterlynck, Stijn, & Aalbers, Manuel. B. (2018). Governing urban development in the Low Countries: From managerialism to entrepreneurialism and financialization. European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(4), 400–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418798673

- Waldron, Richard. (2018). Capitalizing on the State: The political economy of Real Estate Investment Trusts and the ‘Resolution’ of the crisis. Geoforum, 90, 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.014

- Wang, Yingyao. (2015). The rise of the ‘shareholding state’: Financialization of economic management in China. Socio-economic Review, 13(3), 603–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwv016

- Ward, Callum, & Swyngedouw, Erik. (2018). Neoliberalisation from the ground up: Insurgent capital, regional struggle, and the assetisation of land. Antipode, 50(4), 1077–1097. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12387

- Weber, Rachel. (2010). Selling city futures: The financialization of urban redevelopment policy. Economic Geography, 86(3), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01077.x

- Whiteside, Heather. (2019). The state’s estate: Devaluing and revaluing ‘surplus’ public land in Canada. Environment and Planning A, 51(2), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17723631

- Wijburg, Gertjan. (2019). Reasserting state power by remaking markets? The introduction of real estate investment trusts in France and its implications for state-finance relations in the Greater Paris region. Geoforum, 100, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.01.012

- Wijburg, Gertjan, Aalbers, Manuel B, & Heeg, Susanne. (2018). The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: Releasing housing into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation. Antipode, 50(4), 1098–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12382

- Wu, Fulong. (2015). Commodification and housing market cycles in Chinese cities. International Journal of Housing Policy, 15(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2014.925255

- Wu, Fulong. (2018). Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Studies, 55(7), 1383–1399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017721828

- Wu, Fulong. (2019). Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China. Land Use Policy, 104412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104412

- Wu, Fulong. (2020). The state acts through the market: ‘State entrepreneurialism’ beyond varieties of urban entrepreneurialism. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(3), 326–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620921034

- Wu, Fulong, Chen, Jie, Pan, Fenghua, Gallent, Nick, & Zhang, Fangzhu. (2020). Assetisation: The Chinese path to housing financialisation. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(5), 1483–1499. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1715195

- Wu, Weiping. (1999). Reforming China’s institutional environment for urban infrastructure provision. Urban Studies, 36(13), 2263–2282. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992412

- Ye, Lin, & Wu, Alfred M. (2014). Urbanization, land development, and land financing: Evidence from Chinese cities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(sup1), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12105

- Yrigoy, Ismael. (2018). State-led financial regulation and representations of spatial fixity: The example of the Spanish real estate sector. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 549–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12650

- Zhang, Fangzhu, & Wu, Fulong. (2021). Performing the ecological fix under state entrepreneurialism: A case study of Taihu New Town, China. Urban Studies, 0042098021997034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0042098021997034