ABSTRACT

Recent approaches to urban borderlands employ border studies theories to analyze urban socio-spatial differentiation. Such approaches highlight how patterns of segregation generate not only social divisions, but also new interactions and connections. This article moves beyond analytic parallels between geopolitical borders and urban borderlands by tracing connections between changing border regimes and urban landscapes in Africa. Drawing on fieldwork in eastern Ethiopia, we show how shifting meanings and enforcement practices at Ethiopia’s international and subnational borders reshaped the socio-spatial landscape of Jigjiga, capital of Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State. The re-drawing of Ethiopia’s internal borders through federalism in 1991 altered spatial enactments of identity in the ethnically-divided city. Since 2010, new approaches to border governance have driven a shift from urban ethnic polarization toward class-oriented differentiation. We mobilize a trans-scalar analytic that theorizes geopolitical borders and urban borderlands as intertwined milieus where groups create and regulate connections, mobilities, and resource circulations.

Introduction

Widespread border securitization efforts since 2001 have multiplied barriers to mobility and heightened surveillance over financial and material circulations in what some analysts equate to “militarized global apartheid” (Besteman, Citation2020). Security logics and the enforcement of borders to uphold economic inequality between countries parallel trends in cities, where inequality and segregation are on the rise and the livelihoods of lower-class workers and urban poor are often precarious (Lees et al., Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation2014). While recognizing these realities, critical approaches emphasize how boundary-drawing and regulatory processes at geopolitical borders and within cities can create new opportunities and connections for some people even as they exclude others (Feyissa & Hoehne, Citation2010; Hammar & Millstein, Citation2020; Karaman & Islam, Citation2012; Ramírez, Citation2020). “Urban borderlands” theorists mobilize insights from border studies to critique urban studies’ emphasis on segregation, instead drawing attention to “borders and boundaries which not only divide, but also join [urban enclaves] together” (Iossifova, Citation2015, p. 91). This article moves beyond drawing parallels between processes at geopolitical borders and intra-urban boundaries, instead theorizing their mutual imbrication as sites where people enact and transgress spatial divisions in their efforts to manage circulations and connections. We show how shifting political-economic regimes of geopolitical border enforcement worked to transform Jigjiga, Ethiopia – capital of Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State (SRS) and among eastern Ethiopia’s largest cities – from an ethnically-segregated town embedded in regional circulations into a globalizing hub of diaspora return and increasing class-based socio-spatial differentiation.

Using Jigjiga’s transformation as a case study, we argue for a trans-scalar borderlands analytic that foregrounds how people utilize multiple types of borders as spatial technologies for regulating relationships and material circulations. Nation-state border policies play a major role in shaping who and what circulates through cities. This is addressed in some studies of “nationally-contested” cities and migration-and-cities research that highlight how national policies related to border security, mobility, and citizenship shape urban belonging and economic dynamics (De Genova, Citation2015; Shtern, Citation2016). We approach nation-state borders as one of several sites at which people manage mobilities and circulations that affect urban space. What is at stake in our analytic approach is not a theory of urban borderlands and geopolitical borders as interacting scales of social relations in which one level or another is determinant. Rather, we trace how people (including officials and “everyday” actors) work to align social groups across geopolitical landscapes that include (often colonially-imposed) borders and historically-sedimented urban geographies. In eastern Ethiopia, multiple types of intra-national borders demarcating ethnic areas and administrative zones shape urban circulations, connections, and opportunities. In addition, these relationships are not one-directional: what goes on in cities in terms of social connections and collective mobilization can also impact enforcement regimes at geopolitical borders around cities.

The intersection of border regimes, enactments of identity, and transnational connections in Ethiopian cities provides a potent context for theorizing the co-constitution of geopolitical borders and urban borderlands in postcolonial and ethnically-divided contexts amidst present-day shifts in global approaches to border security. The border-related transformations we assess here stem from the (uneven and gradual) implementation of Ethiopia’s ongoing ethnic-based federal decentralization project. In 1991, a coalition of rebel groups overthrew Ethiopia’s soviet-backed Derg regime. By 1995, this coalition (the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front or EPRDF) re-drew Ethiopia’s internal borders to recognize the country’s diverse “nations, nationalities, and peoples.” The system, formally termed multinational federalism but commonly called ethnic federalism, created six ethnically-defined states, three multi-ethnic states (which include ethnicized sub-state divisions), and two federal cities. Several million ethnic Somalis living in eastern Ethiopia, historically stereotyped as secessionists, were now transformed into “Ethiopian Somalis” as Somali officials gained control over the newly established SRS. These geopolitical transformations unleashed shifts in Jigjiga’s social geography and the circulations shaping its economy. Jigjiga transformed from an ethnically-segregated colonial city to a “Somalized” regional capital, still embedded in local cross-border circulations. New border regulation strategies since 2010 have clamped down on these circulations, while also creating new political-economic coalitions and opportunities for the global Somali diaspora to reengage with SRS.

Our analysis lends itself to three suggestions about urban borderlands. First, shifting regimes of enforcement at multiple types of boundaries (not only nation-state borders) shape the relative legitimacy of identity groups in city. Second, it is not only state policies regarding borders or citizenship that affect urban division, but also everyday actors’ engagement in cross-border networks and mobility patterns that use the city as a base for broader connections. Third, urban inequalities and forms of dispossession can emerge from investments and mobilities grounded in non-capitalist rationalities such as kinship and ethnic loyalties. This means that urban segregation does not imply the same dynamics of social and economic separation in every context. Indeed, if such urban inequalities foster not only division, but also new connections with groups linked beyond the city (such as transnational populations), this can increase the political power of urban constituencies.

The following section frames our theoretical approach, specifies our methods, and offers some context. Subsequent sections analyze transformations at geopolitical borders and intra-urban boundaries during three periods: (1) from Jigjiga’s establishment to the introduction of federalism (ca. 1890–1991); (2) the first two decades of federalism (1991–2010); and (3) what some informants call “new federalism” associated with decentralization strategies pursued in 2010–2018. We trace these transformations through a combination of mapping, survey research, and ethnography. The lead author conducted research in Jigjiga for 11 months in 2017–2018 and shorter periods in 2015, 2016, and 2019. The other authors reside there. The final section reflects on the study’s implications for understanding urban borderlands in Africa and elsewhere.

Borderlands urbanism: framework and methods

In the early 21st century, public discourse in much of the world emphasizes borders’ divisive functions. Such a notion can obscure that borders operate in various ways that change over time. Some territorial lines marked on maps are not enforced at all, or only periodically. Some of today’s geopolitical borders were erected to defend existing identity groups and others to corral various ethno-linguistic communities into a governable colonial territory. Geopolitical borders are multi-dimensional or multifaceted, with their own context-specific histories and meanings (Bauder, Citation2011; Johnson et al., Citation2011). This also means borders are “polysemic”: “they do not have the same meaning for everyone” (Balibar, Citation2002, p. 81).

Although today’s logics of global security and migration management tend to treat porous nation-state borders as deficient and in need of securitization (Frowd, Citation2018), the varying modes and degrees of border enforcement also reflect different historically-embedded cultural logics connecting human groups to territories. In Africa, fixed territorial borders are fairly recent techniques for regulating belonging and access to space (Mbembe, Citation2000). Ethnic, religious, and kinship groups have long reproduced themselves through means of defining “inside” and “outside” that are not always spatialized (Barth, Citation1998). As the globe was divided into fixed territories during the 20th century, colonially-imposed borders intersected with such groupings in a variety of ways. In some cases, international or imperial borders imposed on peripheral groups reshaped relations within ethnic groups and created new incentives to identify by national citizenship. In other cases – such as in eastern Ethiopia – international borders remained unenforced for lengthy periods. Unlike nation-building efforts in parts of Europe and elsewhere, Ethiopia has seen minimal sustained efforts to forge a homogenizing national identity – much like numerous African countries. In such contexts, national borders may be less determinant of people’s mobility, belonging, and commercial activity than other territorial or non-territorial divisions.

Borders and cities

If the nation-state is one among many relational groupings, it is nevertheless one whose territorialization has major impacts on many contemporary urban contexts. Conflicts over geopolitical borders and these borders’ relationship to ethnic belonging, political power, and citizenship shape cities, some of which have been analyzed as “contested” or “polarized” cities – such as Beirut, Belfast, Jerusalem, or Johannesburg (one of the few widely-discussed African cases) (Bollens, Citation2012; Bou Akar, Citation2012; Murray, Citation2011). In “nationally-contested” cities, as Shtern (Citation2016) summarizes a common thread of argument, urban encounters “are dictated by the sectarian logic of the macro level national conflict, thus deepening spatial segregation.” A similar emphasis on national-scale bordering shapes literature on migrants and cities, especially a strand of thinking on the “internalization” of national border regimes into cities – what De Genova (Citation2015) calls “a re-scaling of border struggles as urban struggles.” In these analyses, national border regimes manifest themselves in urban neighborhoods and mark migrant bodies through policing practices and migration policies that render foreign “others” deportable or otherwise precarious (Darling, Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2014). Yet, paralleling trends in the contested cities literature, “migration scholarship remains entangled with the national scale” (Çağlar & Glick Schiller, Citation2011, p. 9).

Nation-state geopolitics shape struggles over political and economic inclusion in African cities, especially in the Ethiopian context where, despite the relative lack of nation-building, state-led development remains a guiding principle (Bonsa, Citation2012; Mains, Citation2019). However, in many eastern African cities, homogenizing nationalization efforts appear less important in daily life than more localized and subnational efforts to define belonging according to ethnicity, kinship, and even city- or neighborhood-level groups (Bryceson, Citation2009; Carrier, Citation2016; Landau, Citation2015; Scharrer & Carrier, Citation2019). An important dynamic in these contexts is the relational and thus ever-changing meaning of ethnic identification. The diversity of identity groups in eastern Africa – for example, an official tally of over 80 ethno-linguistic groups in Ethiopia – reflects a historical dynamic Kopytoff (Citation1987) analyzes in terms of “internal frontiers.” Historically, much of Africa exhibited low population density, which created opportunities for people to escape territorialized political control. In this context, control over relationships developed as a more important source of power than territorial sovereignty. This does not mean territorial borders remain less relevant today, but they exemplify distinct logics. Rather than primarily sites of exclusion, borders operate alongside crossroads, roadblocks, and towns as sites at which people work to manage circulations and relationships of dependence (Mbembe, Citation2018). This relativization of national borders as one site of regulating relationships and mobility makes the notion of “border internalization” or of re-scaling national borders into cities appear rather Eurocentric.

This relativization of national borders as part of a broader landscape of governing circulations and relationships intersects with a strength of emerging “urban borderlands” literature: its effort to disrupt scalar analytic hierarchies such as those that prioritize the national level. Urban borderlands researchers and related literature on urban encounters emphasize the multi-scalar nature of everyday boundary-making processes that (re)define group relations (Iossifova, Citation2015, p. 93; Ramírez, Citation2020, p. 148; Valentine, Citation2008). However, in part because such analyses tend to focus on localized urban spaces, the interplay between these urban geographies and borders outside of cities remain underconceptualized. Approaching geographical scale as a flexible and context-specific construct (Marston, Citation2000), we can ask: how do people understand relationships between intra-urban differentiation and more geographically encompassing boundaries? What forms of connection and disconnection link intra-urban processes to geopolitical boundary-making? Addressing such questions requires a trans-scalar analytic that moves across administrative divisions and follows circulations through cities and across borders, seeking to understand how people manage relationships and circulations within and across these spaces. This is important not only for understanding patterns of intra-urban differentiation (e.g. ethnic or class segregation), but also the makeshift alliances, transitory relationships, and “ensembles” that are central to urban life in the global South (Simone, Citation2019; Simone & Pieterse, Citation2017). Such relationships and alliances are often transnational, but little has been written on how multi-scalar boundary-making processes in an age of globalizing border security affect them.

Methods and context

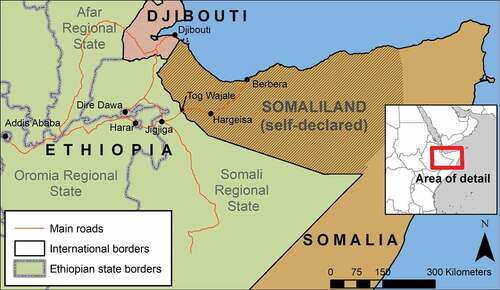

This article presents part of a broader mixed-methods study of border trade and diaspora investment in Jigjiga. During the main study period (July 2017-July 2018), we walked the city and conducted participant-observation with businesspeople and officials daily, documenting relationships between border regulation practices, people’s trans-border connections, and their urban lives and livelihoods. We traveled to the border of the self-declared Somaliland Republic (henceforth Somaliland), as well as from Jigjiga to other Ethiopian cities including Harar, Dire Dawa, and Addis Ababa (see ). Observations were documented with field notes. We interviewed 55 Somali businesspeople (including diaspora investors, cross-border traders, and urban merchants) and eight city and regional officials. One interview section investigated experiences of Jigjiga’s socio-spatial landscape and its change over time. As part of this broader analysis of urban change, we selected key informants to sketch landmarks and neighborhoods on a printed map of Jigjiga. These sketch-map interviews involved up to three maps depending on interviewees’ residence history. Sketch-map participation was limited by low cartographic literacy. Three longtime residents labeled a 1965 aerial photograph and five marked a 1996 aerial photograph. The most up-to-date sketch map was created by labeling 2016 Google Earth imagery (labeled by five participants). For each map, we found that participants’ sketches aligned with each other and with information we gleaned from observation and interviews. We synthesized sketch maps into a schematic map of Jigjiga during each period, adding our own observations to the 2016 map.

Jigjiga’s “internal” social geography over the past century has been tied to its location amidst overlapping ethnic, geopolitical, and lineage-based territorialities. In today’s terms, the “international” but non-ethnic Ethiopia-Somaliland border lies 70 kilometers eastward. The “intranational” ethnic border between SRS and Ethiopia’s Oromia Regional State (ORS) lies 40 kilometers to the west (). Jigjiga’s main east-west thoroughfare bisects the city and connects these borders. The regional capital and a border trade hub, Jigjiga is SRS’s largest city, with an estimated population of over 300,000. Though predominantly Somali today, it has always been ethnically mixed. Statistics on ethnic populations are unavailable, but official marketplace data and our market surveys indicate Somalis comprise 65–70% of Jigjiga’s business owners, followed by Amhara and Gurage (8–13% each), Oromo (2–5%), and other groups. This does not include the significant presence of Oromo and southern Ethiopian laborers and itinerant traders. Cross-border connections and mobility drive Jigjiga’s trade-centered economy and the position of ethnic, national, and Somali clan constituencies within it. These positions have shifted during government changes over the past 130 years (). In the following section, we synthesize the relationship between borders and urban organization during the period of Ethiopian and European imperialism, before upheavals of the 1970s-80s led to federalism’s introduction.

Table 1. Jigjiga administrative timeline

An imperial frontier town, 1891-1991

The Jigjiga Valley was a well site and meeting place for Somali pastoralists before its permanent settlement, but the town’s sustained establishment (ca. 1891) resulted from settler colonialism as the ethnic Amhara-dominated Ethiopian Empire expanded into Somali-inhabited space. This expansion was linked to European colonial extension into the region: Ethiopian claims over the Jigjiga area sought to counter French, British, and Italian claims over the neighboring territories that became Djibouti, British Somaliland, and Italian Somalia. This confrontation between Ethiopian and European governance drove transformations in Ethiopian approaches to managing space and circulations across it. The territorially fluid Ethiopian empire gained fixed borders demarcating it from surrounding European colonies. In the eastern Somali-inhabited region, the Ethiopian economy that had been characterized by in-kind tribute and extraction of agricultural surplus intersected with an expanding British-dominated Indian Ocean sphere of commercial exchange and currency circulation (Thompson, Citation2020). At this juncture, towns became important points for controlling commerce and for seeking to draw Ethiopia’s diverse ethnic groups into forms of imperial citizenship (Bonsa, Citation2012; Carmichael, Citation2001).

Despite their formal status as Ethiopian subjects and the emergence of some alliances between Ethiopian officials and Somali authorities in Jigjiga, most Jigjigan Somalis associated “Ethiopian” governance and identity with ethnic Amhara (locally termed Habeshas, a designation that also includes Tigrayans) and violent practices of over-taxation and livestock raiding (Thompson, Citation2020). On a regional level, this provoked persistent rebellion among Somalis. Anticolonial struggle erupted in 1899 and persisted periodically over the following century. This tended to deepen ethnic tensions between Somalis and Ethiopian non-Somalis.

The story of this imperial confrontation and its manifestations in the colonized frontier town is not only one of violence and division, however. From the viewpoint of Jigjiga’s merchants, borders created new opportunities for urban-based power and profit. The Somaliland-Ethiopia border’s establishment in 1897 generated avenues for officially-sanctioned import-export activities as well as smuggling. Two crucial dimensions of the border affected Jigjiga’s urban development. The first was the border’s porousness – Somalis were permitted to cross the border to graze livestock. The second dimension was British Somaliland authorities’ efforts to leverage border controls to advance British commercial interests in Ethiopia. While preventing Ethiopian authorities from crossing the border into Somaliland, British Somaliland officials encouraged British subjects including Somalis as well as Muslim Arab and Indian merchants to trade in Ethiopia. These non-Ethiopian merchants dominated Jigjiga’s commerce early in the century (Eshete, Citation2014, pp. 16–30). Such divisions were heightened when European powers took control of Jigjiga midcentury: Italians (1935–1941) and then British imperialists (1941–1955) occupied eastern Ethiopia. During this interlude in Ethiopian state-building, Somalis gained increasing control over cross-border circulations, enabled by their kinship connections and local knowledge. From 1935 until the final return of Jigjiga to Ethiopian sovereignty in 1948 (followed by the nearby border areas in 1954–55), European administrators encouraged these trans-border links, downplaying Ethiopian borders’ relevance while envisioning the Horn as part of a unified ethnic Somali space (Barnes, Citation2007). Given this history, it is hardly surprising that even after the Ethiopian Empire regained sovereignty, Jigjiga remained a hub of (largely illicit) border trade and anti-Ethiopian sentiment.

Urban frontier dynamics

The 1960s is the first period for which we have both cartographic data and oral histories documenting the town’s geography and its relationship to broader social dynamics. As in other African colonial towns, mobility between the city and countryside was an important element of local Somalis’ livelihoods and capacity to resist or undermine imperial authority. Unlike in other contexts, however, the proximity of a lengthy and porous border meant that Somalis maintained dominance over urban trade in part through their capacity to move across the border, beyond Ethiopian control. Jigjiga’s urban space was shaped by a bifurcation between Amhara-dominated governance and effective Somali control over commercial circulation, especially so-called “contraband” (a generic term for untaxed goods). By the 1960s-1970s (the final decades of Ethiopian imperialism), this bifurcation underpinned sharp intra-urban differentiation in a town already shaped by the historical residues of three imperial administrations. Italian and British administrators of the 1930s-1940s had worked to enforce urban ethnic differentiation, mapping out a Somali-dominated “native district” and a primarily Amhara “national district” while politicizing ethnicity (Thompson, Citation2020, pp. 545–547). Despite an absence of formal policy enforcing ethnic segregation in the 1960s-1970s, the sedimented political-economic and religious meanings of ethnicity shaped daily practices upholding intra-urban boundaries.

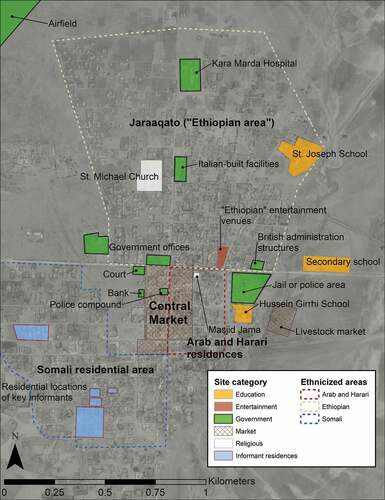

South Jigjiga was a “Muslim side” differentiated into an Arab and Harari section to the southeast, and Suq Somali to the southwest, where all our informants grew up (). The Muslim side contains the Masjid Jamaʿ (Jigjiga’s oldest mosque) as well as shrines and graveyards dedicated to local sheikhs. North Jigjiga, meanwhile, was “Ethiopian”. According to Aden,Footnote1 a diaspora returnee from the US who grew up in Jigjiga, Most Somalis “never crossed to that side”. North Jigjiga’s “Ethiopianness” carried three associations. One was the prevalence of government functions, reflecting the dichotomy between Somalis as colonial subjects and “Ethiopians” as participants in the Amhara-dominated empire. Second was a perception of moral difference. Aden said of north Jigjiga: “We’d never go there. … Anybody who goes there, they’d be like prostitutes, drunks, and all those things … . And so the mentality was, ‘Oh, don’t go there’; it’s – you know, bad people go there” (interview, 1/11/2017). What is evident in such testimonies is the subjective feeling that urban-scale differentiation reflected a broader-scale spatial disjuncture: that Ethiopia was a different place from Jigjiga, separated by a cultural and moral divide. These Somali perspectives on urban division in an Ethiopian garrison town indicate that it is not always people with political power who enforce urban division. Rather than contest non-Somali dominance by seeking political control or integration, Jigjigans at the time sometimes transgressed these urban borders, but often upheld them.

Figure 2. Sketch map of Jigjiga, 1960s-1970s. 1965 aerial photograph background provided by the Ethiopia Mapping Agency

This dynamic is reflected in the third association informants made: connections between urban segregation and people’s broader networks, mobility, and commercial circulations. North Jigjiga was connected to the highland Ethiopian imperial center. For example, Aden recalled the “Ethiopian theater” in north Jigjiga, “where when bands would come from Ethiopia – they would play there” (interview, 1/11/2017). Highland administrators and soldiers also circulated through this space, occasionally deciding to stay (some such families remain today). Meanwhile, Jigjiga’s Somalis faced exclusion and limited mobility within Ethiopia: “For a Somali person to even go past Dire Dawa and to be recognized as Ethiopian was a challenge”, recounted one informant (interview, 3/30/2018). This contrasts with the capacity for mobility and opportunities for trade within eastern Ethiopia and across its borders, from the Somali-Oromo ethnic borderlands around Harar to the Somaliland coast. The mid-century introduction of graded roads and cars sped up livestock exports to Somaliland as well as regional circulations of agricultural goods such as chat – a regionally popular stimulant drug grown in the Harar area and which requires rapid transport due to its perishability (cf. Stepputat & Hagmann, Citation2019). Somalis who upheld Jigjiga’s colonial-era spatial divisions were not simply carving out their own urban space, but also leveraging Jigjiga as a node of social connection amidst cross-border circulations that defied state control.

Due in part to Ethiopia’s tight formal restrictions on trade (even though these restrictions were undermined by the border’s length), networks facilitating such circulations tended to be personalized and embedded in the Somali clan system that undergirded trust in the absence of “formal” economic regulation (Ciabarri, Citation2010). These circumscribed relational networks and circulations created interests among Somalis in upholding certain types of social boundaries and territorial borders to protect their opportunities from “foreign” competition (including by Somalis from neighboring territories). Jigjigans thus often worked to maintain ethnic and territorial differentiations while also creating relationships across such differentiations (cf. Barnes, Citation2010). For example, Aden’s father was a borderlands broker and sometime smuggler of livestock and chat. He established connections to the eastern highlands’ chat-growing areas by marrying a Harari woman and maintaining her household in the Harar area, distinct from his Somali family in Jigjiga. Members of several Somali clans established themselves in the town and utilized its emerging transport and social infrastructures to make broader connections and engage in what Stepputat and Hagmann (Citation2019) describe as projects of circulation, moving resources across international and ethnic borders. The kinship-oriented nature of these links and associated settlement patterns in Jigjiga is manifest in some of our informants’ sketch-map delineations, for example, Ḥaffadda Ablele – Ablele District – named for a Bartire (Jidwaq) subclan ().

Placing Jigjiga’s imperial-era urban geography in this broader spatial context yields three insights connecting urban differentiation to border regimes. First, attending to intra-urban and geopolitical borders as sites that not only divide, but also join spaces and people together (Iossifova, Citation2015) reveals that Jigjiga’s intra-urban differentiation was driven partly by the relative openness of Ethiopia’s international border for Somalis. Second, this means urban ethnic segregation was not only about struggles over belonging and citizenship dictated by national-level (or imperial-level) logics. It involved struggles between Ethiopian governance strategies and local projects of mobility and circulation in the pastoralism- and trade-oriented Somali lowlands. Upholding ethnic divisions in urban space could be seen in this context as part of a strategy to maintain cross-border connections. Third, although Somalis were subjected to violence and dispossession amidst Ethiopian imperialism, the story of Jigjiga’s urban borderlands is not solely one of enclosure and foreclosure, as might be the case elsewhere (Ramírez, Citation2020). Connecting urban borderlands to broader geopolitical relations reveals that marginalization and limitation in the city might in some contexts enable people’s participation in geographically broader social fields.

Jigjiga’s geography would change during the 1970s as the region plunged into conflict. The Arab and Indian population fled the city, and SRS emerged from decades of violence as a federal region under Somali ethnic authority in the 1990s, which unleashed new urban dynamics.

Federalism and the changing meanings of borders

The introduction of ethnic federalism in the 1990s set the stage for shifts in the meanings of, and regulation at, geopolitical borders around Jigjiga and unleashed urban transformations. Federalism’s first two decades – from 1991 until 2010 – are widely described by Jigjigans as a transitional period characterized by the tenuous rise of Somali administrative control over the city and region (“Somalization”), combined with de facto continued non-Somali (Amhara and Tigrayan) political dominance. This section discusses federalism’s initial impacts on urban organization, and the following section explores changes that unfolded from 2010–2018.

Whereas intra-Ethiopian ethnic divides were formerly in a sense “informal”, federalism politicized and territorialized ethnicity. It created new geopolitical boundaries within Ethiopia that ostensibly reflected preexisting ethnic territories, although in fact historical spatial boundaries between groups are difficult to discern. Muslim Oromos who had long played active roles in Jigjiga and intermarried with Somalis were now marked as foreign to SRS, exemplifying how federalism’s logic prioritizes ethnicity over other forms of connection and identification. Federalism has been plagued by conflicts along intranational borders where historically connected groups were now divided into distinct ethno-regional (and sub-regional zone) power structures (Kefale, Citation2013). Ethnic-based relational logics rearranged patterns of access to political territory and urban space. Despite their exclusion from federal leadership, Somalis felt new ownership over SRS and its capital. From an imperial frontier city, Jigjiga transformed haltingly into a Somali-dominated political-administrative city, while remaining a cross-border trade hub.

Conflict, displacement, and cross-border links

Two armed conflicts reshaped the sociopolitical landscape around Jigjiga leading into the 1990s, and recurrent violence has continued to shape urban society into the 21st century. First, in 1977, Somalia’s government supported Somali rebels in Ethiopia and eventually launched an invasion. When Ethiopian forces retook the region in 1978, thousands of Ethiopian-born Somalis fled to Somalia. Some Jigjigans re-crossed into Ethiopia after the war and re-occupied their homes. According to local narratives, however, Jigjiga stagnated. One property owner, a woman named Ubaḥ, recounted that in the 1980s the “mostly Habesha government” appropriated Somali-owned houses and gave them to military personnel (interview notes, 5/20/2012). Escaping across Ethiopia’s borders resulted, for some, in loss of property – although this pales in comparison to the loss of life during the war and subsequent Ethiopian military operations to counter Somali secessionism.

The second conflict – Somalia’s 1991 collapse – initiated a larger stream of return migration from Somalia and marked a geopolitical shift at the Cold War’s end. Somalia’s government disintegrated in January 1991. Many Somalis from Ethiopia joined the exodus of refugees, including to countries of the global North where they formed the Somali diaspora. Meanwhile, as Somalia collapsed, revolutionaries led by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) overthrew Ethiopia’s socialist regime. Many Somalis fleeing Somalia found themselves (back) in Ethiopia as the country reorganized. The Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), a prominent Ethiopian Somali opposition group, collaborated with the TPLF and other rebel groups working to reorganize Ethiopia. The partnership was not equal, however. Somalis continued to feel marginalized in Ethiopia, and the ONLF attempted to hold a referendum on secession in 1994. Federal authorities ousted the party, and the ONLF re-initiated armed insurgency that intensified into the 2000s.

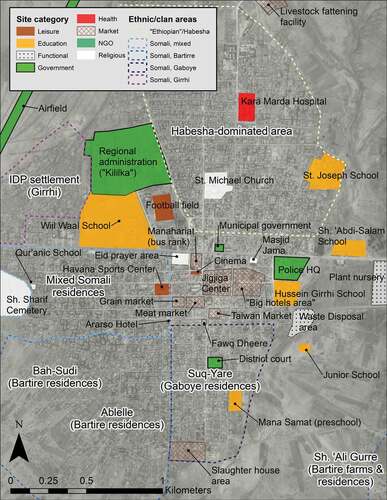

Similar to imperial-era dynamics, during much of the 1990s-2000s effective Ethiopian rule hardly extended past Jigjiga. Beyond the regional capital, cross-border trade and pastoralism continued much as they had before, but the ONLF conflict and the emergence of radical Islamist movements in Somalia legitimized federal government domination in the name of security. Therefore, even as Somalis gained de jure regional autonomy, ethnic Tigrayan and Amhara officials continued to control finance and security in SRS (Hagmann, Citation2005). Thus, even as Jigjiga became more “Somalized” (Emmenegger, Citation2013), inhabitants continued to associate Habeshas with administration and Somalis with cross-border links, mobility, and trade. Jigjiga’s Somalis celebrated their newfound semi-autonomy, even as new conflicts erupted along intranational borders. Violence along the SRS-ORS border has flared periodically since 1991 and intensified as regional borders were finally being demarcated during our study period in 2017. Some Somalis (especially of the Girrhi clan) fled to Jigjiga as internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the 1990s and settled in the city’s northwest quadrant (). Federalism did not lead to complete separation of ethnic groups – Oromos continue to live in Jigjiga, and Somalis live and trade in ORS towns – but it did tend to make the livelihoods of Ethiopians living outside their ascribed “home” region more precarious.

Figure 3. Sketch map of Jigjiga, 1990s. 1996 aerial photograph background provided by the Ethiopia Mapping Agency

Displacement and dispossession did not necessarily translate directly into destitution and powerlessness. By the late 1990s, refugee camps hosting Somalia’s displaced became new hubs of borderlands trade (Ciabarri, Citation2008). Likewise, even displacement-fueled urban growth presented opportunities for Jigjiga’s market expansion. One aspect of this was opportunity to lease or sell urban land on a relatively unencumbered market – despite formal state ownership of land (interview, 12/8/2017; Mahamed, Citation2014). Another aspect was the intensification of cross-border trade. After 2002, when the “contraband” market in Hartisheikh Refugee Camp was forcibly closed, Jigjiga reemerged as the hub of imports from Somaliland. The city’s reliance on foreign-manufactured imports is signaled in the local name for the city’s center: “Taiwan Market”. Even as federal authorities including the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) and the Ethiopian Revenues and Customs Authority (ERCA) formally controlled cross-border mobility and trade, “contraband” flowed freely (Kefale, Citation2019).

Borders in the city

Jigjiga’s pre-federal ethnic-sectoral segregation began to disintegrate as Somalis gained formal power over urban affairs and diverse clans settled in the city. Still, during the 1990s, “Jigjiga was like the Amhara areas and the Somali areas,” says one informant (see ). “Only the market was a shared place” (interview, 12/8/2017). Yet the meanings of these differentiations shifted. Recollections of the 1990s focused on how ethnic differentiation became a terrain not just of federal politics, but of localized contestation between ethnicized neighborhood gangs known (for unclear reasons) as “China groups.” During these years, additional Somali clans also settled and gained more visible presence. Some were noted for their marginal position, including the “ghetto”-like enclave of Suq-Yare, inhabited by Gaboye Somalis. Others arrived through government connections. Says one former official, “Sometimes Ogaden clan were president, then all of the people of that clan were coming here. Some other times Isaq became the president, then those people were coming … ” (interview, 12/8/2017). There had been 10 regional presidents by 2010, resulting in the layering of lineage groups over sedimented ethnic divisions. Ogadenis and others who moved to the city for political reasons did not settle in delimited areas, but bought houses across the city, especially formerly Amhara-owned residences in north Jigjiga. By the 2000s, vestiges of ethnic segregation persisted, but the social boundaries of clan identity, localized neighborhood territories, and regional government connections increasingly displaced strict ethnic separation.

Even if ethnic spatial segregation broke down somewhat, sectoral differentiations between different types of government work and commerce continued to shape urban social power. Federal authorities managed SRS presidential appointments and were responsible for the rapid turnover in leadership. Ogaden Somalis, the largest population group in the region, became associated in local views with regional politics. Meanwhile, local Jidwaq clans controlled urban institutions, including the position of Jigjiga mayor (this would change after 2010) (Emmenegger, Citation2016, p. 66). Somalis still commonly associate Habesha ethnicities with governance functions, but the majority of Amhara and Tigrayans in Jigjiga from the 1990s to the present have been taxi drivers, store owners, manual laborers, and officials in branches of Addis Ababa-based institutions (e.g. government-owned utilities, banks, and non-governmental organizations).

Federalism rendered these non-Somalis “foreign” to Jigjiga in new ways that complexified the Somali/Ethiopian dichotomy. Sadam, who grew up in Jigjiga during the 1960s, reflected on the changing nature of ethnicity: “To me, as a child, I thought everybody coming from the highlands was Amhara” (interview, 3/30/2018). Now he recognized numerous ethnicities among non-Somalis. This recognition of complexity did little to ameliorate non-Somalis’ feelings of political exclusion, however. As one Gurage bank official explained:

I was born in Jigjiga and grew up in Jigjiga, but if I want to run in an election, I can’t because I’m not Somali. I could never be the mayor of Jigjiga if I wanted to. Instead of someone who is not Somali but who knows the city very well, they will bring a Somali who has never been to Jigjiga and make him the mayor. (Field notes, 09/24/2017)

The result of federalism’s implementation on urban organization reflects elements of Yiftachel and Yacobi (Citation2003) “urban ethnocracy” model that connects urban ethnic conflicts to state power, class projects, and ethnonational contests over citizenship. Jigjiga’s ascent as ethno-regional capital ethnicized urban organization and unraveled some spatial and sectoral polarizations between “Ethiopian” politics and Somali trade. Somalis gained new political influence, though under the thumb of federal institutions. In places like the Israeli cities Yiftachel and Yacobi analyze, groups struggle for control of urban space within a national context dominated by one of the groups involved. The case of Jigjiga suggests more complex dynamics in multi-level ethnicized governance structures like Ethiopian federalism. Here Somalis jostled for regional and urban power in part by seeking connections with non-Somali federal authorities. Federalism’s border re-drawing realigned ethnic relations within government hierarchies in ways that encouraged Somali political elites to forge relations with non-Somalis in higher positions, while simultaneously marginalizing Jigjigans from these same non-Somali ethnic groups.

An important dimension of urban power that persisted from the imperial era into the first decades of federalism was the continued porousness of the Ethiopia-Somaliland border, which enabled Somali merchants to continue their dominance over cross-border circulation and mobility. At the same time, new tensions emerged among Somalis, who now comprised both the majority of “contraband” traders and an increasing proportion of officials in charge of regulating border trade. Tighter control over cross-border circulations would be at the center of urban transformations that unfolded after 2010.

“New federalism” and transnational connections

In 2010, federal elites appointed ʿAbdi Moḥamoud ʿUmar – locally known as ʿAbdi Iley – SRS president, where he would remain until his arrest in August 2018. Jigjigans often describe this period as “new federalism.” It was characterized by dramatic changes in governance over mobility and access to SRS, shifting the terrain of ethnicity, national identity, and opportunity in Jigjiga. New securitization regimes at both the Ethiopia-Somaliland border and administrative borders within SRS extended government control over circulations that had previously eluded officials. Ethnicity remained relevant, but Jigjiga’s urban divisions increasingly differentiated those who could gain access to government-controlled opportunities for trade and investment (often through kinship or patronage connections) and those who could not.

As context, a foundation of ʿAbdi Iley’s rise was the devolution of security functions from federal military forces to a regional paramilitary force, the Liyu (“Special”) Police, under ʿAbdi’s command. The ENDF had been fighting the ONLF and other rebel groups for a decade with little success. The Liyu Police subdued the ONLF insurgency by 2012 through a combination of cooptation and counterinsurgency. Relative “peace” was established in part through mass arrests, executions, and other human rights abuses (Hagmann, Citation2014; Human Rights Watch, Citation2018). Despite fears of arbitrary arrest and experiences of violence, the advent of a more autonomous SRS administration increased some Somalis’ confidence to invest in Jigjiga. The city grew explosively, nearly tripling in settled area between 2006 and 2019 from 14.18 sq. km. to over 39 sq. km (estimated based on Google Earth imagery). This rapid growth was driven not only by increased local investor confidence, but also by federal disbursements granted to the region in return for effective counterinsurgency – and, surprisingly given the recent violent conflict, by the influx of hundreds of diaspora returnees from overseas. SRS practices of border regulation played a key role in Jigjiga’s urban growth as well as in an incipient shift from ethnic-based to class-based spatial differentiation.

Governing relationships through border control

Regional officials utilized management strategies at both the international border with Somaliland and at sub-regional borders to place traders in positions of dependence on government elites. Along the Somaliland border, SRS agencies partnered with the ERCA to clamp down on untaxed circulations. By 2015, roving anti-contraband militias and incentives for reporting illicit trade directed cross-border trade flows onto regulated routes, especially the Tog Wajale-Jigjiga road. Many formerly successful smugglers were arrested, leaving a trickle of semi-tolerated small-scale contraband (Thompson, Citation2021). Crucially, increasing restrictions of such borders were not simply exclusionary or meant to impede circulations. Exemplifying the logic of borders and crossroads as sites of governing deterritorialized relationships (Mbembe, Citation2018), multiple types of borders as well as government-controlled urban land became sites the regional government leveraged to create a transnational constituency.

International border regulations were paired with a new system of subnational trade regulation that determined who could trade what, and where. Ethiopia’s regions are subdivided into administrative units known as zones and lower-level kebeles. As summarized in one Food and Agriculture Organization report, the SRS administration “issued Franco Valuta (FV) license[s] to 27 hand-picked traders/cooperatives (3 for each administrative zone) to import and distribute basic food items” (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], Citation2012, p. 6). In effect, numerous mini-monopolies were created by dividing the region into differentiated spatial and sectoral markets. Inside Jigjiga, a relatively open market prevailed with strong competition driven by “contraband” imports, but a new elite class emerged: people who had become rich through exclusive SRS trade licensing at surrounding (international and intranational) borders.

Subnational borders gained new relevance not only for trade, but also for administration. ʿAbdi’s government launched a program known as “renaissance” (dib-u-ʿurasho) in which officials were rotated into regional zones where they were not embedded in local kinship structures. Under this guise, complained former city officials, Ogaden Somalis connected to the president but who had no immediate interest in Jigjiga came to dominate the Jigjiga City Administration and control urban affairs (interview, 12/8/2017).

The strategic management of border-dependent opportunities rearranged relationships beyond the region as well. As SRS officials used border regulation to “build businesspeople” (interview, 6/12/2018), they also offered exclusive investment opportunities and trade licenses to diaspora Somalis living abroad (Thompson, Citation2021). From 2010 onwards, ʿAbdi Iley traveled to diaspora hubs like Minneapolis (USA) and Melbourne (Australia), inviting diaspora Somalis to invest. Many diaspora Somalis were already financially supporting relatives in Ethiopia, and jumped at the invitation to open businesses and seek lucrative trade licenses (perceived to be granted in return for supporting ʿAbdi’s SRS administration). The diaspora had been famous before 2010 for their support to ONLF rebels. In a sudden about-face, the diaspora became a linchpin of ʿAbdi’s support. As heightened security clampdowns and suppression of dissent alienated locals, ʿAbdi Iley leveraged border controls to secure a transnational clientele.

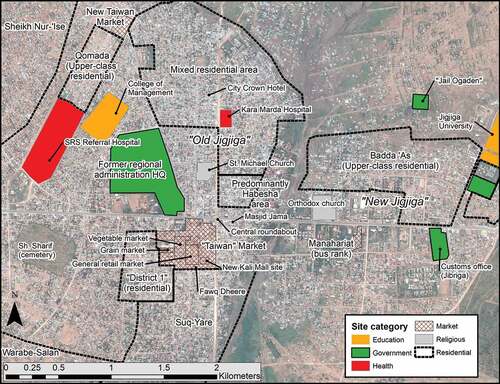

By 2018, Jigjiga’s central roundabout was surrounded by multi-story hotels and business centers under construction, owned by government-connected traders and diaspora capitalists. An office center owned by a licensed import-exporter was completed in 2019. To the east, two new hotels belonged to the region’s most prominent licensed chat exporters. What some informants described as the “predominantly Habesha area” had compressed into a small island amidst ethnically mixed settlement (). If Jigjiga’s landscape before federalism was characterized by a bifurcation between trade and government functions, this has shifted toward a divide between precarious small-scale traders and government-allied elites, many engaged in cross-border trade or monopolizing zonal markets (Thompson, Citation2021).

Transnational relations and urban differentiation

Even many diaspora Somalis who were not connected to officials bought land, built houses, and invested. Ethiopian nationals owned most of Jigjiga’s largest businesses, but diaspora-owned hotels, restaurants, and other enterprises emerged (e.g. Jigjiga’s garbage collection service was contracted to Australian Somalis). Would-be diaspora investors flowed constantly into Jigjiga to scope out business opportunities. This transformation ushered in two apparent paradoxes that show the importance of a trans-scalar approach to urban borderlands.

The first paradox is that Jigjiga’s increasing inequality looks like class-based segregation at the urban scale, but is driven in part by a decrease in international-scale separation as diaspora Somalis moved from abroad into the regional capital. Return migrants reinscribed international wealth disparities within the city as they built houses that by local standards were mansions. Local elites and diaspora returnees bought land primarily in two locations: Jigjiga’s former airfield (known as Qomadaha) and the former farmlands northeast of the city’s earlier extent (known as Badda ʿAs or “Red Sea,” for its red tile roofs). Most visibly in Qomadaha, the Jigjiga City Administration used urban land as a means of attracting diaspora investors and “buying off” business elites by allegedly easing their access to government-owned land (interviews, 12/31/2017; 5/12/2018). Plots in these neighborhoods tend to be priced beyond the power of most Ethiopian nationals. A decent middle-income salaried job paid around US $250-$300 per month. In 2018, 20-by-20-meter plots in Badda ʿAs sold for around ETB 600,000 (about US $20,000) (interview, 12/19/2017). Monthly rent for a modest 3-bedroom house in these areas in 2017–2018 could top ETB 15,000 (US $500). A taxi driver referred to these neighborhoods’ inhabitants as “royal people,” reflecting a common perception of increasing socio-spatial segmentation (field notes, 6/10/2015).

Diaspora Somalis also invested in central areas – in businesses in and around Taiwan Market, and in houses in various residential areas, including the former “Ethiopian area” (). Suq-Yare, inhabited by stigmatized Gaboye Somalis, remained a “ghetto,” in the words of several informants. To the southwest, Warabe-Salan, formerly described as belonging to the Ablele subclan, was increasingly inhabited by local Somalis of diverse clan origins, as was another emerging suburb to the northwest called Sheikh Nur-ʿIse. During our fieldwork, some locals who had been pushed from central areas by rising prices and government initiatives such as 2016 road-widening demolitions were moving to these areas.

Walking through the streets in these neighborhoods, one could imagine Jigjiga as increasingly a class-divided city, with new urban borders created by processes of gentrification and dispossession. Jigjiga’s dominant house form is a walled compound defended by razor wire and broken glass atop plaster barricades. However, looking beyond a static cartography of division indicates a second apparent paradox: people’s everyday practices reveal how emerging urban differentiations also enable connections and relationships (Iossifova, Citation2015). We noted that many diaspora Somalis were already supporting family members in the region, and such kinship obligations facilitated return migration. These investors were embedded in (usually kinship-based but also Islam-infused) relationships of mutual support and obligation. Jigjigans and relatives abroad have often maintained social connections despite Ethiopian nationals’ difficulty crossing international borders (especially in the post-2001 border security environment). When they settle in the city, diaspora investors and local business elites hardly find themselves socially segregated from less well-off relatives and friends. Relatives from rural areas commonly live in part of an elite investor’s house. Sharing some money among family is a widespread cultural expectation. Such relations tend to persist regardless of individuals’ spatial location, though they may take on different forms depending on the spatial proximity between individuals.

This does not mean urban-scale boundaries are irrelevant. Prime residential location in a segmented space can be a resource, akin to geopolitical borders (Feyissa & Hoehne, Citation2010) – not only for the wealthy who reside there, but also for locals who forge connections with relatives or friends in such spaces. Upholding intra-urban boundaries may be one way “ordinary” Jigjigans defend exclusive relationships with wealthy and powerful people. Indeed, many Ethiopian nationals, however they might criticize the prodigious wealth of some diaspora returnees (by local standards), also use diaspora investment as an opportunity to make claims for redistribution on diaspora relatives who are now more accessible than when they lived overseas. For example, the taxi driver who resentfully called Badda ʿAs and Qomadaha the domains of “royal people” celebrated the return of his own wealthy uncle from the US. Far from resenting his uncle’s wealth, he visited his uncle and worked to position himself as a potential business partner or local manager for this relative’s investments.

Struggles for the borderlands city

Foregrounding these interactions across multiples types of borders brings into perspective how people imagine their place in the city. This includes resisting dispossession (Ramírez, Citation2020, p. 150), but the borderlands perspective employed here reveals that such struggles may involve alliances and networks that cross-cut neighborhood boundaries and international borders as well as distinctions between more powerful and more marginalized groups. That diaspora investors are not simply gentrifiers or impersonal “capital” means this is not a binary conflict between poverty and wealth. One local businessperson who was otherwise critical of diaspora investment pointed out when asked about diaspora real estate purchases:

Somalis are religious people. They don’t like to take something from others, because there is a hadith that says, “Do not take land from people—even one hand-length.” It’s forbidden. Otherwise, in the hereafter … Allah will put that land on your head. It’s very heavy; it can’t be carried. So the people believe that hadith and they don’t touch the land. (Interview, 12/3/2017)

While state strategies of defining and regulating geopolitical borders shape understandings of belonging as well as access to trade opportunities, the state itself does not necessarily provide the most important social framework for access and property rights. Shifts at geopolitical borders gave Somalis – including some far beyond Ethiopia’s borders – new understandings of their belonging and new opportunities in the city, but these geopolitical shifts interacted with shared religion and cultural norms. The SRS administration that attracted investment might collapse at any time. Thus, even though Somalis did use state avenues to secure their claims to urban land (Emmenegger, Citation2013), investing in social relations was essential. The upshot of these connections is both the increasing imbrication of border regimes with urban social relations, and heightened tensions surrounding strict border controls. On one hand, SRS strategies of border regulation were shaping struggles over urban space by privileging government-connected elites. On the other, the city became a locus of transnational resistance to ʿAbdi’s harsh regime – including the border controls that facilitated these urban connections.

Events at the end of our study period indicated that it was not only border regimes that affected urban organization, but also that trans-border relationships articulating in cities can impact border regimes. In September 2017, in response to a massacre of Somalis in a nearby ORS town, SRS officials evicted the city’s massive Oromo population to “their own” ethnic region. Already marked as “foreigners” in SRS under ethnic federalism, Oromos born and raised in Jigjiga were forcibly trucked to ORS. This constitutes an extreme version of state efforts to leverage the ethnicized meanings of geopolitical borders to dispossess non-Somalis (akin to the re-scaling of national borders in cities elsewhere). However, what the eviction of Oromos from Jigjiga revealed was the simultaneous precarity and crucial importance of trans-border and inter-ethnic relations in urban life. Several prominent businesses owned by Somalis who had Oromo links were shuttered, leading to an outcry among the diaspora business community. More generally, business activity stalled due to a sudden shortage of labor and of non-Somali customers. Diaspora and local activists together called for ʿAbdi to step down as SRS president and pushed for an easing of border trade restrictions and security measures. Several months later, in August 2018, federal forces surrounded Jigjiga and took ʿAbdi to prison in Addis Ababa. An immediate result was that a pro-ʿAbdi gang burned and looted non-Somali-owned businesses. However, a new administration soon rose to power and quickly eased border trade restrictions while also de-emphasizing ethnic divisions between Somalis and Oromos.

Shifting regimes of border enforcement around the city had played a major role in reorganizing urban socio-spatial relations. Our observations raise the possibility, yet to be traced more fully, of ways in which struggles for access and rights in cities can also lead to transformations in geopolitical border regimes. In a regional context characterized by persistent patterns of cross-border mobility and efforts to govern circulation (Scharrer & Carrier, Citation2019; Stepputat & Hagmann, Citation2019), the densification of trans-border social relations in urban spaces generate new possibilities. These urban-centered relationships – exemplified in diaspora return migration to Jigjiga – may drive apparent spatial segregation, but can also create opportunities for local Ethiopians marginalized by heightening 21st-century border securitization. The social transformations reshaping Jigjiga’s urban landscape – and, we would suggest, those of other cities in Africa and beyond – must be understood with reference to regimes of geopolitical border regulation and cross-border circulations that shape urban borderlands.

Toward a trans-scalar borderlands analytic

We have argued that people’s efforts to construct trans-spatial relationships and manage circulations in a world of geopolitical borders are intimately connected to the formation and transformation of urban borderlands. Jigjiga’s history as a “contraband” hub shows how urban differentiation is not solely driven from “above”, by the state or capital. Urban divides are also upheld in daily life by people engaged in informal or illicit modes of mobility and circulation who use urban space as a site for making social connections across geopolitical borders – borders that are exclusionary for some groups of people and connective for others. The transformations wrought on Jigjiga by federalism’s 1991 introduction and the post-2010 strategic use of border controls to attract transnational investment push analysis of urban-scale differentiation beyond the city toward the shifting modes of border regulation that shape access and opportunity in urban space. This relational space of diaspora links, transnational mobility, and projects of circulation – which characterizes not only Jigjiga, but also other cities and neighborhoods in Africa and elsewhere (Banerjee & Chen, Citation2013; Scharrer & Carrier, Citation2019; Terrefe, Citation2020) – is best understood through a borderlands analytic that moves beyond the city and takes into account multiple geopolitical border regimes. While security and mobility regimes at national borders do appear increasingly important in shaping access and circulation in cities, national border regimes interact with other spatial (sub-national) and social (ethnic, kinship, religious) boundaries that may be equally relevant.

This analytic approach offers three insights that link the interplay of division and connection across intra-urban boundaries as explored by Iossifova (Citation2015) and others (e.g. Hammar & Millstein, Citation2020) to the construction of (dis)connection at geopolitical borders. First, it speaks to how multiple types of geopolitical borders can restructure “the relational co-existence of a city’s ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ inhabitants” (Ramírez, Citation2020, p. 149). Shifts in the meanings of and regulations at geopolitical borders may play key roles in marginalizing or stigmatizing foreign migrants residing in cities (De Genova, Citation2015). This also applies similarly in Ethiopia’s case to the relative (dis)empowerment of co-nationals of different ethnicities. In Jigjiga, non-Somalis are frequently marked as illegitimate inhabitants even though members of these same identity groups govern Ethiopia and sanction Somalized regional governance. On the other side, however, ethnicized exclusion does not mean that the “right” identity guarantees opportunities or spatial access. Ethnicity is not inherent, but enacted in specific cultural milieus and amidst shifting relations with other groups (Barth, Citation1998). In Jigjiga, Somalis tended to legitimize and secure their investments not through ethnicity per se, but through a combination of government connections and enactments of social responsibility (especially among kin). Struggles for urban inhabitation in this context take shape amidst relationships and expectations for redistribution, political support, and moral responsibilities that span borders.

Second, beyond disrupting the idea that national borders play the determinant role where urban economies are closely linked to cross-border circulation, our analysis also indicates the sometimes ambivalent role that ethno-national state power plays in urban borderlands. While ethnically exclusionary states in some contexts play a role in planning and reinforcing urban ethnic divisions (Bollens, Citation2012; Shtern, Citation2016; Yiftachel & Yacobi, Citation2003), “everyday” actors also may work to maintain divides for a variety of reasons oblique or opposed to state projects. Urbanites engaged in cross-border mobilities and circulations might acquiesce to or even uphold a degree of urban segregation where their isolation protects these trans-border links – as Somalis did to some extent in Jigjiga historically. In other contexts, urban divisions also emerge where ethno-national groups mobilize to take border enforcement into their own hands where national or regional authorities are perceived as too lenient toward cross-border flows, as with responses to migration in cities like Johannesburg (Thompson, Citation2017). In such processes, ethnicized boundary-making may mobilize ethnic power as an end in itself, but claims of ethnic and “local” authority can also be means of forging connections and enabling circulations of material resources through personalized networks that in practice span ethnic and geographical boundaries.

Third, this trans-scalar borderlands analytic addresses how urban economic inequalities may emerge in border-dependent relationships that are intertwined with relational systems other than capitalist logics and financial circuits. To be sure, borders often enable exploitation and tend to favor capital over labor in many contexts by rendering mobile workers precarious (Darling, Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2014). However, reading emerging urban inequalities in Africa as driven predominantly by the extension of neoliberal or capitalist logics and relationships may elide other relationalities and rationalities that bring globalized inequalities into cities. Transnational webs of personalized relationships and mutual responsibilities linking African cities to diaspora populations may also influence the re-scaling of borders and inequalities into cities. In contexts where relational logics of dependence and patronage have long influenced opportunity (Mbembe, Citation2000, Citation2018), urban-scale economic segregation may not mean the same thing to urbanites or imply the same dynamics of social and economic separation as in more individualistic settings.

Urban spatial differentiations interact with boundary-making and boundary-transgressing processes across broader spaces that are often treated as distinct scales of analysis “outside” or “above” the urban scale. It remains to be examined in more depth how the increasing securitization of international borders at present shapes intra-urban differentiation in various contexts, without assuming either that urban borderlands are independent of geopolitical boundary-making processes or that they are directly determined by border regimes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Urban Geography editor Nathan McClintock and three anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All informant names in the text are pseudonyms.

References

- Balibar, Étienne. (2002). Politics and the other scene (Christine Jones, James Swenson, and Chris Turner, Trans.). Verso.

- Banerjee, Pallavi, & Chen, Xiangming. (2013). Living in in-between spaces: A structure-agency analysis of the India-China and India-Bangladesh borderlands. Cities, 34(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.06.011

- Barnes, Cedric. (2007). The Somali Youth League, Ethiopian Somalis, and the Greater Somalia Idea, ca. 1946-48. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 1(2), 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050701452564

- Barnes, Cedric. (2010). The Ethiopian-British Somaliland boundary. In Dereje Feyissa & Markus V. Hoehne (Eds.), Borders and borderlands as resources in the horn of Africa (pp. 122–131). James Currey.

- Barth, Fredrik. (Ed.). (1998). Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of cultural difference. (Reissued ed.). Waveland Press.

- Bauder, Harald. (2011). Toward a critical geography of the border: Engaging the dialectic of practice and meaning. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(5), 1126–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2011.577356

- Besteman, Catherine. (2020). Militarized global apartheid. Duke University Press.

- Bollens, Scott A. (2012). City and soul in divided societies. Routledge.

- Bonsa, Shimelis. (2012). City, state and society: The making of Urban Ethiopia, the 20th century. Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 45, 1–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44325772

- Bou Akar, Hiba. (2012). Contesting Beirut’s frontiers. City & Society, 24(2), 150–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-744X.2012.01073.x

- Bryceson, Deborah F. (2009). The urban melting pot in East Africa: Ethnicity and urban growth in Kampala and Dar Es Salaam. In Francesca Locatelli & Paul Nugent (Eds.), African cities: Competing claims on urban spaces (pp. 241–259). Brill.

- Çağlar, Ayşe, & Glick Schiller, Nina. (2011). Introduction: Migrants and cities. In Nina Glick Schiller & Ayşe Çağlar (Eds.), Locating migration: Rescaling cities and migrants (pp. 1–19). Cornell University Press.

- Carmichael, Tim. (2001). Approaching Ethiopian History: Addis Abäba and Local Governance in Harär, ca. 1900 to 1950 [ Ph.D. Dissertation]. Michigan State University.

- Carrier, Neil. (2016). Little Mogadishu: Eastleigh, Nairobi’s Global Somali Hub. Oxford University Press.

- Ciabarri, Luca. (2008). Productivity of refugee camps: Social and political dynamics from the Somaliland-Ethiopia border (1988-2001). Afrika Spectrum, 43(1), 67–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40175222

- Ciabarri, Luca. (2010). Trade, lineages, inequalities: Twists in the Northern Somali path to modernity. In Markus V. Hoehne & Virginia Luling (Eds.), Peace and milk, drought and war: Somali culture, society and politics (pp. 67–85). Hurst & Company.

- Darling, Jonathan. (2017). Forced migration and the city: Irregularity, informality, and the politics of presence. Progress in Human Geography, 41(2), 178–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516629004

- De Genova, Nicholas. (2015). Border struggles in the migrant metropolis. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 5(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/njmr-2015-0005

- Emmenegger, Rony. (2013). Entre Pouvoir et Autorité. Propriété Urbaine et Production de l’État à Jigjiga, Éthiopie. Politique Africaine, 132(4), 115–137. https://doi.org/10.3917/polaf.132.0115

- Emmenegger, Rony (2016). Writing Space and Time: An Ethnography of State Sedimentation in the Ethiopian Somali Frontier [ Ph.D. Thesis]. University of Zurich.

- Eshete, Tibebe. (2014). Jijiga: The history of a strategic town in the Horn of Africa. Tsehai Publishers.

- Feyissa, Dereje, & Hoehne, Markus V. (2010). State borders and borderlands as resources. In Dereje Feyissa & Markus V. Hoehne (Eds.), Borders and borderlands as resources in the Horn of Africa (pp. 1–25). James Currey.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2012). Policy brief: Informal cross border livestock trade in the Somali Region. FAO Regional Initiative in Support to Vulnerable Pastoralists and Agro-Pastoralists in the Horn of Africa.

- Frowd, Philippe M. (2018). Security at the borders: Transnational practices and technologies in West Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Hagmann, Tobias. (2005). Beyond clannishness and colonialism: Understanding political disorder in Ethiopia’s Somali region, 1991-2004. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 43(4), 509–536. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X05001205

- Hagmann, Tobias. (2014). Punishing the Periphery: Legacies of State Repression in the Ethiopian Ogaden. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 8(4), 725–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2014.946238

- Hammar, Amanda, & Millstein, Marianne. (2020). Juxtacity: An approach to urban difference, divide, authority, and citizenship. Urban Forum, 31(2), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09402-8

- Human Rights Watch (2018). “We are like the dead”: Torture and other human rights abuses in Jail Ogaden, Somali Regional State, Ethiopia. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/ethiopia0718_web.pdf.

- Iossifova, Deljana. (2015). Borderland urbanism: Seeing between enclaves. Urban Geography, 36(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2014.961365

- Johnson, Corey, Jones, Reece, Paasi, Anssi, Amoore, Louise, Mountz, Alison, Salter, Mark, & Rumford, Chris. (2011). Interventions on rethinking “the border” in border studies. Political Geography, 30(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.01.002

- Karaman, Ozan, & Islam, Tolga. (2012). On the dual nature of intra-urban borders: The case of a romani neighborhood in Istanbul. Cities, 29(4), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2011.09.007

- Kefale, Asnake (2019). Shoats and smart phones: Cross-border trading in the Ethio-Somaliland corridor. DIIS Work Paper 2019, No. 7. Danish Institute for International Studies.

- Kefale, Asnake. (2013). Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia: A comparative regional study. Routledge.

- Kopytoff, Igor. (1987). The internal African frontier: The making of African political culture. In Igor Kopytoff (Ed.), The African frontier: The reproduction of traditional African societies (pp. 3–84). Indiana University Press.

- Landau, Loren B. (2015). Recognition, solidarity and the power of mobility in Africa’s urban estuaries. In Darshan Vigneswaran & Joel Quirk (Eds.), Mobility makes states: Migration and power in Africa (pp. 218–236). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lees, Loretta, Shin, Hyun Bang, & López-Morales, Ernesto. (2016). Planetary gentrification. Polity Press.

- Lewis, Hannah, Dwyer, Peter, Hodkinson, Stuart, & Waite, Louise. (2014). Hyper-precarious lives: Migrants, work and forced labour in the Global North. Progress in Human Geography, 39(5), 580–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514548303

- Mahamed, Jemal Y. (2014). An Assessment on Informal Land Market in Peri-Urban Areas of Somali Region, Jig-Jiga City [ Masters thesis]. Ethiopian Civil Service University, Addis Ababa.

- Mains, Daniel. (2019). Under construction: technologies of development in urban Ethiopia. Duke University Press.

- Marston, Sallie A. (2000). The social construction of scale. Progress in Human Geography, 24(2), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200674086272

- Mbembe, Achille. (2000). At the edge of the world: Boundaries, territoriality, and sovereignty in Africa. Steven F. Rendall (Trans.). Public Culture, 12(1), 259–284. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-1-259

- Mbembe, Achille (2018). The idea of a borderless world. Africa Is a Country. https://africasacountry.com/2018/11/the-idea-of-a-borderless-world.

- Murray, Martin J. (2011). City of extremes: The spatial politics of Johannesburg. Duke University Press.

- Ramírez, Margaret M. (2020). City as borderland: Gentrification and the policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(1), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819843924

- Scharrer, Tabea, & Carrier, Neil. (2019). Introduction. Mobile urbanity: Somali presence in Urban East Africa. In Neil Carrier & Tabea Scharrer (Eds.), Mobile urbanity: Somali presence in Urban East Africa (pp. 3–25). Berghahn Books.

- Shtern, Marik. (2016). Urban neoliberalism vs. Ethno-national division: The case of west Jerusalem’s shopping malls. Cities, 52, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.019

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. (2019). Improvised lives: Rhythms of endurance in an urban south. Polity.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq, & Pieterse, Edgar. (2017). New urban worlds: Inhabiting dissonant times. Polity Press.

- Stepputat, Finn, & Hagmann, Tobias. (2019). Politics of circulation: The makings of the berbera corridor in Somali East Africa. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(5), 794–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819847485

- Terrefe, Biruk. (2020). Urban layers of political rupture: The “new” politics of Addis Ababa’s megaprojects. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14(3), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2020.1774705

- Thompson, Daniel K. (2017). Scaling statelessness: Absent, present, former and liminal states of somali experience in South Africa. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 40(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/plar.12202

- Thompson, Daniel K. (2020). Capital of the imperial borderlands: Urbanism, markets, and power on the Ethiopia-British Somaliland Boundary, ca. 1890-1935. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14(3), 529–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2020.1771650

- Thompson, Daniel K. (2021). Respatializing federalism in the horn’s borderlands: From contraband control to transnational governmentality. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2021.1943494

- Valentine, Gill. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133308089372

- Yiftachel, Oren, & Yacobi, Haim. (2003). Urban ethnocracy: Ethnicization and the production of space in an Israeli “Mixed City.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21(6), 673–693. https://doi.org/10.1068/d47j