ABSTRACT

Development zones are largely missing from discussions on urbanization in China. This is a surprising omission given the centrality of these zones in economic and urban growth patterns. In this paper, we argue that development zones have become a back door to urbanization as local governments are locked in competition to attract new residents and sources of employment. While the long-term purpose behind most of these zones has been to facilitate industrialization, they are at the same time considered a quick and effective means of accelerating economic growth and boosting the promotion chances of leading officials. We set this in the context of horizontal struggles between local governments and vertical struggles that see central government attempting to re-direct development zones away from urbanization towards advanced high-tech industries. Our cases studies illustrate how this process occurs in divergent contexts. In the relatively disadvantaged Chizhou prefecture-level city in Anhui Province, local governments mutually compete by designating development zones and building the physical and social infrastructure to make them desirable places in which to live and work, but without significant success. Meanwhile, the flagship Suzhou Industrial Park, having fought off a nearby rival, builds for a growing population, positioning itself strategically vis-à-vis Shanghai.

Introduction: development zones as instruments of urbanization

China’s unprecedented urbanization has been studied from multiple angles: commodification of housing, gentrification, suburbanization, peri-urbanization, financialization, ghost towns, and many more. In this article, we approach urbanization from a direction which is central and yet has been largely neglected, that of development zones, meaning in the Chinese context industrial zones. We argue firstly that without a clear appraisal of the role of development zones as “back doors” to urban growth, the nature of urbanization in China cannot be fully understood.

The foundational and primary purpose of development zones remains that of attracting inward industrial investment. This “front door”, however, is hard to achieve, and so local governments use zones as back doors to urban expansion, sidestepping thereby tight controls on land conversion. Following on from this, we deploy the concept of competitive urbanization to argue that development zones themselves are the outcome of competitive pressures to boost local economies. By showing how development zones are being transformed into city-building projects, we contribute to debates about the nature of urbanization in China, aiming specifically to refine ideas on how and why urban areas expand. Our article focuses on the scramble for growth in a resource-poor prefecture in Anhui Province and contrasts this with the ostensibly untroubled expansion of a development zone in wealthy Suzhou. Despite repeated interventions from the central government, local governments in much of China have established and expanded development zones in order to urbanize further and faster, seeing immediate gains from urbanization as a passport to more long-term benefits from industrialization. They promote urbanization and industrialization because of the competitive pressure under which they operate, pressure that emanates from institutional specificities of the Chinese party-state system.

This competitive urbanization among local governments manifests itself also in scalar struggles between governments of different levels (province, prefecture, etc.) and between local and central governments, as our two case studies illustrate. Central government issues repeated guidelines on reducing the number of zones and focusing them on the transition to high-tech industry. Local governments look to a different approach, one that involves prioritizing the provision of urban facilities – infrastructure, housing, schools. They do this in the hope that investment will follow: this remains an important target. Previous studies have for the main part failed to present a critical picture of development zones as instruments of urbanization – as tools, in other words, that allow for significant urban expansion leading then to inward investment in manufacturing and services. Their tendency to focus on suburbanization has led, we argue here, to an inappropriate and ultimately misleading picture of the urbanization process.

The creation of economic enclaves of various types has been one of the mainstays of orthodox development policies as pursued by the World Bank and other global institutions. China’s deployment of this strategy comes from an apparently divergent ideological position. Nevertheless, nowhere would it seem that development zones have been as successful as they have been in China. It is generally accepted that they contributed massively to the country’s economic growth, particularly from the 1980s through to about the time of China’s pump-priming reaction to the global financial crisis of 2008, when infrastructure construction and urbanization became the primary foci of growth policies (Wu, Citation2022). Development zones have however remained the easiest route to rapid urban expansion for smaller cities throughout China. So much is this the case that development zones with large tracts of empty land and vacant buildings have become a common feature of the Chinese landscape. Despite this state of satiety, local governments are continuing to raise the funds and build the infrastructure for these zones – from roads to schools – as well as subsidizing the construction of ranks of standardized factory buildings.

For decades now, attempts have been underway to prune the number of zones. They are seen by central government as too numerous, eating up too much land that should be in agricultural use. Current central government policy, as evidenced in a number of State Council guideline documents, is one of upgrading of zones – transitioning to high-tech industries – and reducing vacant land. Central government believes that its local counterparts focus excessively on commercial and property development thereby changing the nature of zones. Local governments, on the other hand, are for the main part intent on growing their cities to enhance local prestige and personal advancement, Nova Techsetting development zones through urbanization processes, ensuring that they become mixed-function zones with a high degree of the residential component. Local governments have played elaborate games of cat and mouse with higher-order authorities in order to be able to sidestep regulations and restrictions and open and expand these zones at will, at the same time competing ferociously against each other.

In this research, we have chosen as our principal case study Chizhou, a prefecture-level city in the south of Anhui Province; we see it as representative of relatively poorer parts of inland China that struggle to attract investment and grow their economies, and set it alongside Suzhou to provide a contrasting experience of a similar phenomenon. Chizhou provides a fitting choice as a case study firstly because of its lack of “success” among the prefecture-level cities of Anhui Province, and secondly because of its liminal location, geographically close to the highly developed Yangtze River Delta and yet stuck in the competitive quagmire of a provincial backwater positioned within the poorer central area of China. In terms of GDP Chizhou is the poorest prefecture in Anhui, highlighting thereby the contrast with Suzhou. Chizhou contains various types of zone, whose creation has often been made possible by the post-facto legalized transfer of cultivated land on the basis of preferential policies. This has led to zones with vastly over-drawn boundaries all trying to attract the same industries, resulting in high vacancy rates and vast swathes of land that are either unutilized or still being cultivated by the farmers from whom the land was expropriated. Local governments have now taken to building new towns in these zones, chasing a population that has ceased growing in the context of an urbanization shaped by competition not only within the city and province but also across provincial boundaries (Zhou, Citation2020).

Ostensibly, Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) provides a significant contrast. It is situated in a wealthy part of the country next to one of China’s most iconic cities. The industrial park has an important history involving the Singaporean state, making it a model zone. This notwithstanding, it was for a long period involved in a competitive struggle with an expanding rival development zone. In recent years it has undergone a rapid increase in the expanse that has seen it become a “hyper-urbanized” zone of multiple CBDs and commercial and residential infrastructure alongside its industrial facilities. Its landscape of power and wealth contrasts sharply with the empty spaces, degrading industrial facilities, and rush to build urban infrastructure that characterize many development zones in Chizhou and similar inland areas.

In this paper, we use the words “development zone” to translate the Chinese kaifaqu. Kaifaqu is the generic term for delineated enclaves with special status and relates to a range of zones including special economic zones, bonded zones, export processing zones, border economic cooperation zones, eco-city zones, and national tourist resort areas. The zones we discuss here, however, are more specifically industrial development zones (chanye kaifaqu) and their title normally includes the words economic or high-tech alongside industrial, each of which defines a legally based zone type (Ngo et al., Citation2017). “Suzhou Industrial Park” (Suzhou chanye yuan) is an exception, but the park is nonetheless a development zone.

This research is based on four field trips conducted in Chizhou from 2015 to 2020 and two visits to Suzhou in 2018 and 2019. In Chizhou, we interviewed a total of 25 senior officials, sometimes more than once, in each of the relevant administrative units – Chizhou City Government, Guichi District Government, and Qingyang County Government – as well as the development zones. These officials were responsible for economic development, and in particular the planning and development of zones. To provide a more rounded picture we also interviewed a banker, a real estate developer, and other leading figures from the local business community, as well as the head of a local city planning company. During our visit in June 2017, we held separate group discussions with local government planners, officials of the local development zones, and academics at local institutions of higher education. These meetings varied in numbers attending, and were generally rather cagey affairs, with participants reluctant to divulge precise information on sensitive issues like vacancy rates in development zones. This will come as no surprise to anyone who has undertaken research in China (or indeed in many other countries), but we were able to verify information and pursue our questions much further in some very informative interviews referred to above, as well as in informal and off-the-record conversations, especially with members of local elite networks with whom we were in contact. In Suzhou, we interviewed three senior officials from the SIP Management Committee and three senior officials in charge of planning and upgrading SIP, as well as four planners in Suzhou City Government and the provincial Jiangsu Planning Institute. Additionally, we spoke with five owners of small factories, all of whom had been settled in the park for 20 years or longer and were familiar with the park’s development process and in particular with the fluctuating attitude of local government toward small-scale manufacturing enterprises. In a number of cases, follow-up telephone interviews were conducted, and where possible all material was triangulated, much of it through widely available online data and documents.

The paper continues with a review of writing on urbanization, drawing attention in particular to the pivotal role of the state. We also examine debates over development zones, the story of whose excessive growth and later culling is covered in the section that follows. Our two case studies form the central part of this paper. We introduce the first development zones in Chizhou, showing how they are used to further strategies of growth. We look subsequently and more briefly at SIP, whose scale and functions strike a contrast with Chizhou and make it indistinguishable from a “normal” city. We conclude with reflections on the competitive urbanization that fuels the growth of the development zone.

Urbanization processes and competitive development zoning

Our contention in this paper is that competitive urbanization and scalar struggles around development zones are part of the same context. In much of the literature, however, the urbanization process and the story of development zones are covered separately. We examine each of these pieces of literature here, bringing them together by arguing that zones are primary instruments in China’s competitive urbanization.

In the Chinese context, urbanization has been conceptualized in at least two principal ways. Firstly, some studies are cast in terms of suburbanization driven by capital investment, whether private or issuing from the state (see, for example, Liu et al., Citation2017). They have, for example, drawn attention to the role of the market and of investor and consumer demand in accelerating the process of suburbanization: “Without pent-up demand for new housing on the urban edge, recent suburban expansion would not have occurred on such a mass scale” (Shen & Wu, Citation2013, p. 1824). Or they have placed suburbanization in the context of land-based growth coalitions and capital accumulation (Jiang et al., Citation2016a; Shen & Wu, Citation2017).

A second emphasis, far more important in the urbanization process, is on the creation of new towns and cities in areas adjacent to existing settlements, with the state – generally the local state – as a driver of this urbanization process (Miao et al., Citation2019; Wu & Phelps, Citation2011). Various examples spring readily to mind: amongst tier one cities, Beijing’s new administrative center, Tongzhou (Zou & Zhao, Citation2018); amongst tier two cities such as Zhengzhou and Kunming (Wu & Waley, Citation2018; Xue et al., Citation2013); and amongst lower tier cities, for example, Hebi in Henan Prefecture (Liu et al., Citation2012). Other examples include master-planned suburban communities, university towns, and eco-cities (Caprotti, Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2014; Pow, Citation2018; Shen & Wu, Citation2012). It follows that many of these planned communities are either built around housing or, as Miao (Citation2017) writes in her commentary on housing for science park employees, need a residential component to attract the qualified workforce they are appealing to.

Implicit in many of the above accounts but largely missing from this picture is the part played by development zones as back doors to urbanization. Among a small number of studies to mention development zones in this context, Wu and Phelps (Citation2011, p. 415) observe that, “Most established city jurisdictions in China have, either by themselves or in conjunction with central government, designated new districts as a means of developing what are essentially large suburban employment nodes in the form of industrial parks or zones”. Wu and Phelps’ focus, however, lies elsewhere, on the fragmented governance of Yizhuang New Town, which they conceptualize as a form of post-suburbia. Li et al. (Citation2020) identify three forms of suburbanization in Guangzhou: market-led new towns, state-led development zones, and “society-led” villages. Theirs is a valuable intervention, but it does raise questions about the validity of distinctions between state, market, and society, given the state’s ubiquitous presence in the market (Jiang & Waley, Citation2018). Yew (Citation2012) highlights the significance of development zones as a means for local government to expand the amount of land under its jurisdiction and increase its ability to extract rent. She calls this “pseudo-urbanization”, but as our case studies show, this might better be seen as back-door urbanization; the re-classification of land as development zone for industry is treated by local government as a first step toward urban construction. Urbanization in China occurs for the most part through administrative land grab and then a process of urban in-fill.

The sheer number of development zones, as illustrated in the following section, makes it clear that this is local government’s preferred avenue to urban expansion and economic growth. This has led to intense levels of competition between and even within local governments as they all apply the same formulae for urban aggrandizement. Given its ubiquity, and we exemplify it here in the two contrasting territories of Chizhou and Suzhou, this type of competitive urbanization has received surprisingly little comment in the academic literature (but see Yew, Citation2012; and Jiang et al., Citation2016b). Competitive urbanization is fierce and all-encompassing, a significant intensification of the inter-local competition that can be found in many parts of the world and that can be attributed in large part to global neoliberal currents. It is a process of conflictual urban aggrandizement fired specifically by four concurrent elements: by the relentless promotion of people and place and by moves to attract investment and well-qualified young people.

Central to competitive urbanization is, firstly, the personnel promotion system, part of the wider and more nebulous world of party-state culture (Cartier, Citation2019). This hinges around promotion and punishment for officials in the context of meeting targets (Chien, Citation2013; Guo, Citation2020; Pang et al., Citation2018; Smith, Citation2013; Yan & Yuan, Citation2020). While there has been a recent move to incorporate a wider range of criteria (Gao & Tyson, Citation2020), economic growth however measured remains the default factor conditioning promotion (or its opposite) and as a consequence spurring competitive urbanization and the creation of development zones. Secondly, alongside this sits a geopolitical system built around a hierarchical scale of territories (including development zones), whose full impact on urbanization processes is seldom conveyed (but see Cartier, Citation2011). Promotion up the territorial ladder, from, for example, county-level to sub-prefecture-level city, results in greater powers and more budgetary control (He et al., Citation2018). To attain these ends, economic growth remains paramount, and the creation of development zones is the surest means of attaining them. Thirdly, competitive urbanism involves the attracting of inward investment to bring about economic growth (what we call here the front door). While this is the primary purpose of development zones, attracting inward investment is hard to manage because of the intensity of competition (Jiang & Waley, Citation2020); it is far easier to designate the zones, allowing thus for land conversion and urbanization, and creating the possibility for subsequent inward investment. Urban infrastructure such as educational facilities can then be used to attract university graduates and other “creative talent”, whose presence should serve to draw inward investment (Gong & MacLachlan, Citation2021; Wang & Li, Citation2019). This is the fourth element. On a more general level, competitive urbanization, propelled by the state, is part of a much broader system of competitive activities conditioned by certain important institutional factors, including the dual land system, local governments’ need for extra revenue, and the commodification of housing, all of which is well covered in the literature (see, for example, Shen & Wu, Citation2013). Although he does not use the term, competitive urbanism is cleverly parodied in Yan Lianke’s novel (Citation2016/2013) translated into English as The Explosion Chronicles (Qian & An, Citation2021).

The establishment and enlargement of development zones lies at the heart of this competitive urbanization. Indeed, over several decades this produced a competitive frenzy, famously characterized as “zone fever” (Cartier, Citation2001). The competition can be extraterritorial, horizontal, and vertical. It is extraterritorial as with the prominent example of Singapore’s foundational involvement in Suzhou Industrial Park, the Singaporean state seeking to create the space for its companies to export both capital and expertise and thereby to Nova Techsette its economy internationally (Phelps, Citation2007). It is also horizontal, between local administrative entities, as zone competes against other zone in a process amply illustrated by our Chizhou case studies (Phelps et al., Citation2020). Above all, it is vertical, between central and local governments, as again exemplified in Chizhou. In terms of vertical competition, development zones can be seen as a weapon in scalar struggles between central government in Beijing and provincial and prefecture-level governments (Guo, Citation2020; He et al., Citation2018; Jiang & Waley, Citation2020). Central government calibrates the degree of its control to allow for experimentation in a process that Miao and Phelps (Citation2021) term policy sprawl. However, questions have arisen and debate has been engaged on whether zoning represents a process of centralization. Cartier (Citation2011) has argued that it should be seen as a process of recentralization after some years of decentralization. Others have interpreted these tensions in terms of downscaling and upscaling, seeing these processes as occurring contemporaneously (Li et al., Citation2014).

Recent developments would appear to reinforce the argument that leans towards a qualified form of recentralization, reflecting what Liu and colleagues (Citation2012) refer to as “administrative urbanization”. The first of these developments is the creation of “new districts” (xinqu) such as Binhai (in Tianjin, 2006) and Liangjiang (in Chongqing, 2010) (Li, Citation2015). The second are the so-called “feature towns” (tese xiaozhen), modeled on pilot schemes in Zhejiang Province, and in particular around its capital city, Hangzhou (Miao & Phelps, Citation2019). Miao and Phelps (Citation2019) see these featured towns as part of a design to balance industrial and residential functions. Zou and Zhao (Citation2018) point to the dangers of these zones actually exacerbating competition and simply becoming vehicles for real estate development.

Perhaps, in summary, the situation can best be conceived as a process of central initiative, followed by, but also overlapping with, multiple local-level projects whose very proliferation has given rise to a long drawn-out but intensifying process of recentralization.

It is on these insights that our research builds; our paper not only straddles these two strands of literature – on processes of (sub)urbanization and on development zones as struggles between central and local governments – but it brings them together by affirming the role of development zones as agents of urbanization deployed by local governments that are embroiled in competition for economic growth.

Development zones as growth package

For much of the 70 years of the People’s Republic, the relationship between the urban and the industrial has been a close and intricate one. Work units were the principal agents of production; and production, the primary consideration, during the Maoist era. Work units often built housing outside of plan, either within the work unit compound or close by it (Lu, Citation2006). The early development zones – the four special economic zones established in the south of China in 1980 – represented a very different approach to the prioritizing of production, but one in which housing, in particular, remained a secondary concern. It was only first with the commodification of housing in the 1990s and then after the emergency four trillion yuan stimulus package of 2008 that housing and the construction of infrastructure became the foremost priority, as urbanization took over from industrialization as the leading form of capital accumulation.

The perceived success of the four (subsequently five) first special economic zones as models in term of investment and development set off a boom in the construction of development zones in the eastern cities of China. In 1988, the State Council licensed local governments at the provincial level to approve the establishment of local development zones. Subsequently, zone fever spread throughout the country. Local governments at various levels tried to attract foreign investment, develop industries, and promote local economic development in specially designated zones. As a consequence, a variety of development zones with a wide range of names have been established (see ). Throughout the 1990s and into the present century, the number of development zones expanded rapidly, even at the rural county and township level (Cartier, Citation2001). Much of China’s economic growth in the last 30 years has been derived from development zones, particularly in the years 1984–2008. This is mainly reflected in four indicators: GDP, fiscal revenue, tax revenue, and total foreign investment (see ).

Table 1. The 552 national development zones and their categories in 2018.

Table 2. Main economic indicators of 219 national development zones in China in 2018.

The State Council, as well as other government organs, routinely refers to development zones as “successful practices” of opening-up and reform, or uses similar terminology. This is hardly surprising when one considers the figures provided in . Development zones have been both the symbols of opening-up and reform and the driving force behind economic growth to an extent almost without parallel elsewhere in the world (Yeung et al., Citation2009). But alongside them, we must not neglect the importance of investment from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the Chinese diaspora. Nor should we underestimate the importance of joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, a move that led to many of the conditions of SEZs being extended beyond their territory (Yeung et al., Citation2009).

For some years now, central government has been attempting to limit the number of development zones, but local governments have reacted by changing their names (Cartier, Citation2001; Ngo et al., Citation2017). Local governments have also been able to hide behind the preference of the State Council for issuing guidelines rather than binding regulations (Cartier, Citation2011). There have been repeated government policy pronouncements on this subject, notably in 2003 and 2005, pronouncements that very specifically identify the problem and inveigh against “unauthorized” (shanzi) development zones (State Council, Citation2003; State Council, Citation2005). They stipulate that on no account should quotas of land for conversion from agricultural to urban use be exceeded nor should land be illegally expropriated from farmers. In July 2003, the State Council carried out a review of the number and quality of development zones across the country. By December 2004, their number had been reduced from 6,866 to 1,568, covering a total area of 38,600 square kilometers (MLR, Citation2005). Central government followed this up by removing its recognition from some development zones and forcing them to merge, particularly in small cities, including Chizhou.

These measures were not effective for long. By 2018, the number of China’s development zones of all types and names had increased to 2,543, including 552 national development zones and 1991 provincial development zones, according to data released in the China Development Zone Directory 2018 (NDRC, Citation2018). These figures do not include the countless small development zones that lower-tier governments have been allowed to establish since 1988. In Anhui Province, there were 117 development zones in 2018 with 21 at national level and 96 at provincial level, but their number had been reduced from 162 in the preceding year as a result of State Council pressure. Similarly, in Jiangsu Province, a total of 174 development zones were listed, including 71 state-level development zones and 103 provincial-level development zones (NDRC, Citation2018).

One of the principal reasons why local governments have generally been so keen to attract industry is that industrial establishments bring in long-term tax revenue. Wu and Phelps (Citation2011, p. 242) have argued that, “Under the current land-use system, the incentives are for local government to release land for industrial and not residential uses. Since there is no property tax in China, land for residential use only brings a once and for all lump-sum land premium, in contrast to industrial land uses which generate sustained taxes to local governments.” As urbanization has become ever more central to local economic growth, however, so local governments have prioritized development zones as a growth package within which the residential and commercial component plays a central part. This is notwithstanding the fact that rising land and property prices resulting from land-based growth regimes increase the production cost of manufacturing (interview, local government officials, 26 December 2018).

Local governments, particularly those in small cities, use the cachet attached to development zones to attract companies, regularly using subsidies to encourage investment (Yang & Wang, Citation2008). But companies need employees. Development zones have as a consequence become increasingly multi-functional, with schools and hospitals, in order to become comfortable and appealing, especially for high-tech industries and their educated and highly qualified workforce (Miao, Citation2017).

Local governments are also adept at circumventing the supposedly stringent regulations that limit the amount of land that can be converted from agricultural to urban use. The system of conversion quotas has until 2020 been centrally driven, but local governments find various ways to deal with the quotas (Yang & Wang, Citation2008). One is to participate in land exchanges; these can be organized by local governments within the same province, as happens in Jiangsu Province, or as part of a more complex scheme of rights transfers, as operated around Chengdu in Sichuan Province (Shao et al., Citation2020; Shi & Tang, Citation2020). A second involves building on land that is not designated as agricultural; this is often hilly or otherwise unsuitable for agriculture. Thirdly, local governments can evade the restrictions if their project is designated as a key national project as is the case with Suzhou Industrial Park and Anhui Jiangnan Industrial Concentration Zone, discussed below.

Central government, on the other hand, wants to engineer a move of investment from property to industry. Xi Jinping has talked about housing not being for speculation and the need to return to territorial spatial planning. The State Council has for some years been encouraging a transition in development zones to high-tech and innovative industries, seeing this as a key to realizing industrial upgrading, all the more so in view of trade friction with the U.S. Successive State Council guidelines have been issued in recent years, calling for moves toward high-tech and innovative industries and attracting foreign investment (State Council, Citation2017; State Council, Citation2019). The unwritten subtext would appear to be that more needs to be done. Nevertheless, while such a transition may make sense in the context of wealthier parts of the country, in provinces and prefectures with fewer cards to play, they appear to be of little significance, as the case of Chizhou demonstrates.

Keeping up with the zones(es) in a small prefecture-level city in Anhui Province

In Chizhou, we find a confusion of development zones whose status often changes as they shift from being local to provincial and even to national. The confusion is such that local government officials themselves are sometimes unsure of their status. The rush to build development zones has been intensified by the zeitgeist of competition that infects all areas of official life and leads to a strategy of government best crystallized in the old adage, “Keeping up with the Joneses”.

Chizhou was only created as a prefecture-level city in 2000 after a bewildering number of shifts in administrative affiliation; it has jurisdiction over Guichi District, Qingyang County, Dongzhi County, and Shitai County (see ). It is the weakest of Anhui’s prefecture-level cities in terms of GDP and fiscal revenue, and has a population that has flat-lined in recent years at around 1.6 million. Rumors abound that it will be swallowed up, as happened recently to the nearby city of Chaohu. On account of the relatively small size of its central urban area, which falls within the Guichi District, the former mayor and party secretary of Chizhou tried to build a larger urban framework. As the population was insufficient to justify building a new town, it was felt that the only way to grow the city was by designating development zones (interview, local officials, February 17, 2020). Thus the burst of zone designations was motivated by the existential necessity to expand the prefectural economy by the fastest means at hand. This, however, led to conflicts with central government policy (zone numbers had to be rationalized) and to conflicts between local governments at different scales (primarily between Chizhou and Qingyang County); at a personal level, it created winners and losers among local government officials and party cadres, as we show below.

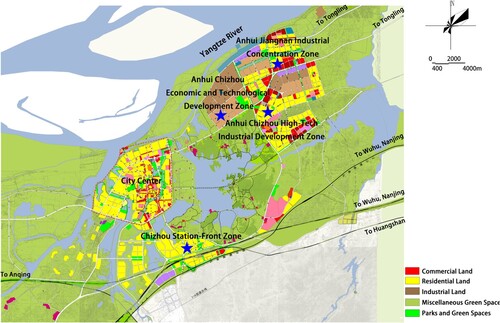

Figure 1. Chizhou City’s central Guizhi District, indicating the location (but not the borders) of the three more central of Chizhou’s six development zones; Anhui Jiangnan Industrial Concentration Zone includes large swathes of land to the east. Source: Adapted from a Chizhou City Government map.

The national strategy, propagated in the 1990s through preferential policies, of promoting the industrial base by creating designated zones was pursued with particular vigor during her five years of tenure (2010–2015) by Chizhou’s former mayor, who pushed for the construction of further development zones and the enlargement of existing ones in order to enhance Chizhou’s economic position in Anhui Province. These moves were dogged, however, by fierce competition between the city and district governments as each was intent on attracting more people and investment into the zones that they administered. At its peak, around the year 2015, Chizhou contained 13 development zones. The consequence of this policy of growth for growth’s sake has inevitably been zones with large tracts of empty land and numerous empty factory buildings even as the local government continues to use funding from banks to provide infrastructure in the form of roads, schools, and hospitals.

In 2018 and 2019, in response to repeated directives from central government echoed by Anhui Province, Chizhou City Government reduced the number of its development zones through mergers and closures, with the result that there are only six zones that have been preserved (see ). Chizhou’s four constituent counties/districts were allowed to keep only one zone each, while the prefecture-level city retained two. This is in line with the State Council’s policy principle of one zone per county (interview, local officials, 28 September 2019).

Table 3. The situation of development zones at various levels in Chizhou city.

In the paragraphs that follow we provide a variety of examples of the role development zones play in the competitive process of urbanization. The preeminent case of a development zone in which state-led urbanization has trumped a stuttering industrialization is Anhui Chizhou High-Tech Industrial Development Zone, a zone funded and managed by Guichi District Government. Initially named Guichi Industrial Park, the zone was established in March 2003 by the district government, which spent 110 million yuan to requisition 120 hectares and build the necessary infrastructure. Three years later, in February 2006, in order to comply with an adjustment in the main urban area and create space for the construction of a new high-speed railway station, the zone was relocated to a much larger site a short distance to the northeast. In February 2006, it was approved by the Anhui Provincial Government as a provincial-level development zone. In April 2010, it was approved by the national government, and, in 2016, it was officially renamed Anhui Chizhou High-Tech Industrial Development Zone (interview, city government officials and planners, 22 August 2018).

The high-tech industrial zone has the advantage of being near the central city (Guichi District), making it easier (at least in theory) for the Guichi District Government to attract residents there. In fact, the relocated zone has come to be treated as a new town. Most notably, two of the district’s leading schools have been relocated to the zone to encourage people to buy an apartment there. In order to enhance the confidence of investors, the offices of the Guichi District Government and its related departments were all relocated to the zone. As of 2020, at least 120 enterprises of various types had settled in the high-tech industrial development zone. Among this number were 26 companies in electronic information, 34 in mechanical equipment manufacturing, and 31 in new energy-saving materials and environmental protection. In 2017, industrial output in the zone was valued at 7.2 billion yuan, and tax revenues were 400 million yuan (interview, local official, 21 December 2018).

The situation on the ground is rather different. Based on interviews with local officials from the Chizhou City planning department, as well as our own observations, we found that there is a 60–70 percent vacancy rate in the zone. One official described the situation in the following terms: “We are facing huge pressure to attract factories and companies as we have invested big sums into around half a million square meters of standardized factory buildings. Some of them have been built by [private] property development companies [to whom] … local government has provided a five percent subsidy” (interview, local official, 20 December 2018). Our visits to the zone revealed empty three-lane boulevards, expanses of vacant land, and, most surprisingly, unused hulks of factory buildings.

Anhui Jiangnan Industrial Concentration Zone is the largest development zone in Chizhou, by some distance. It is one of two zones established on the orders of central government expressly to gather together Anhui Province’s scattered industrial establishments. Few of its 216 square kilometers have yet been built on; it is in effect primarily a land bank for future urbanization. A city government official informed us that the zone is likely to be increasingly transformed by the city government into an urban district (interview, city government official, 22 December 2018). Another official, involved directly through the zone’s management committee, was more specific: “After five to ten years of hard work in the Jiangnan Concentration Zone, a modern industrial new district – an ecological riverside new city – will rise on this 216 square kilometers of land” (interview, city government official, 22 December 2018).

Anhui Qingyang Economic Development Zone is the only zone in Chizhou not to be struggling to attract investments. Indeed, in a reverse process to other Chizhou zones, it has exploited its relative success by implementing ambitious plans for a new urban center. The zone was founded by the local Qingyang County Government (one of the lower-level authorities within Chizhou) and was promoted to provincial level in 2015. It has been unusually successful in attracting inward investment despite a local policy decision not to offer subsidies. On the back of its success, the county government has pushed ahead with the construction of an ambitious new town in which commercial, government, and welfare services, including two of the prefecture’s best-rated schools, are located. So successful has it been that county government officers claimed to us that prefectural government officials had snatched away some large projects from their zone using policy and administrative inducements. The party secretary of Qingyang County, principal protagonist behind the urbanization project, was promoted in 2015 to the position of deputy mayor of the prefecture-level city in a shake-up that led, as we have seen, to the sidelining of the mayor as a result of what was considered to be Chizhou City’s poor economic performance (interviews, local officials, 28 August 2015; 4 September 2016; and 21 June 2017). Later official planning reports indicated, however, that a property glut had occurred in the county’s new town; this is not surprising given that the population throughout Chizhou has risen only relatively slowly in the last ten years (from 1.43 million in 2008 to 1.47 million in 2018).

Chizhou Station-Front Zone (Chizhou zhanqian qu) supports the contention advanced by Wu and Phelps (Citation2011) that there is no clear dividing line between the development zone and an urban new town: examples of the former normally include urban housing and amenities, while examples of the latter contain quasi-industrial functions. Thus, Chizhou Station-Front Zone has been developed using the same techniques and logic as a development zone, even if it is not formally classified as one. As with standard development zones, the boundaries have been substantially over-drawn, giving the zone an expanse of 31 square kilometers, with an anticipated population of 117,800. Chizhou City Government planned the zone to capitalize on the opening in 2015 of a new high-speed railway station. The aim, not yet fully realized at the time of writing (in 2021), is for the zone, alongside its residential component, to have an important commercial and quasi-industrial function as a location for services such as distribution logistics, producer services, large-scale retail malls, offices, and leisure and tourism facilities (interview, city government officials, 22 December 2018, and 29 August 2021). Many of these facilities had yet to be constructed in 2019, while new housing compounds had only been partially completed.

Such are the personal and commercial consequences of the competitive urbanization that colors life in an inland city. There is in Chizhou an immersion in a competitive grasp for investment and for population growth and little suggestion of a response to central government’s policy of transition to high-tech industry. In Suzhou, on the other hand, the situation is very different: while an element of competition remains present, the emphasis on high-tech industry sits comfortably with local aspirations even as the park “hyper-urbanizes”.

Suzhou’s development zone complete with lake and CBDs

The China-Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) can be considered to have almost the same iconic significance in China’s contemporary development as the first four Special Economic Zones and as Pudong in Shanghai, whose planning and construction occurred at approximately the same time. It originated in a high-level attempt involving Singapore’s founding father and former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and the Chinese president, Jiang Zemin. The aim was strategic, to learn from Singapore’s success in economic planning and development by creating an industrial growth pole.

SIP, which was officially designated a national-level economic development zone by the State Council, has undergone several stages since its establishment in 1994 through the creation of a joint Sino-Singaporean development company in which the Singaporean government had a majority shareholding. The story of Singapore’s increasingly fractious involvement in SIP has been widely discussed elsewhere and need not detain us (Miao, Citation2018; Pereira, Citation2002; Phelps et al., Citation2020). Germane to the discussion in this paper is the fact that back in 1992 Suzhou officials had proposed to the Singaporean authorities that they establish their new joint Sino-Singaporean venture in Suzhou New District, but were turned down (Yeung, Citation2000). Nevertheless, the New District expanded even faster than its better known counterpart across the city, prompting the Singapore government to reduce its stake. Despite this competition and the reduced Singaporean involvement, SIP grew rapidly, and by 2003, its main economic indicators had reached the levels of those of Suzhou City ten years earlier, a speed equivalent to building a new Suzhou in ten years. In 2006, with the approval of the State Council, the industrial park’s planned area was expanded by 10 square kilometers. More recently, since 2012 SIP has seen successive measures to promote high-tech industries of various kinds, to the point where by 2017 it ranked fifth among China’s high-tech zones (interview, SIP official, 20 August 2018).

By 2019, SIP had grown radically and consisted of an administrative area of 278 square kilometers, of which over 150 square kilometers were either built up or available for development, the rest being green space and lakes (see ). In the process, it had absorbed large expanses of residential land and had eight street committees under its jurisdiction, with a total resident population of 1.15 million (interview, official from Jiangsu Planning Institute, 26 November 2019). SIP’s current development plan calls for further significant expansion. According to an official from the provincial government’s Jiangsu Planning Institute, the objective of SIP’s Management Committee is “to build a modern, livable new city with high-end industry, cultural wealth, prosperous residents, and a beautiful environment” (interview, 20 June 2019).

Figure 2. Suzhou Industrial Park. Source: Adapted from a map published by Suzhou Industrial Park Management Committee.

Despite its status as a development zone, SIP in fact would be hard to distinguish from any other Chinese city. It is today so large that it contains a number of CBDs, at the center of which stands Jinji Lake. It consists of five main functional areas – business, science and education innovation, tourism, high-end manufacturing, and international trade. In 2019, the largest of its CBDs contained 87 commercial buildings in which a number of high-tech and high-end business service companies have offices. Alongside the construction of these large commercial centers, SIP Management Committee has worked to attract a number of schools and universities, seeing this as the best way to assure an inflow of highly qualified workers (interview, Jiangsu Planning Institute official, 28 August 2020). Suzhou University and Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University both have campuses in the park, and they have set up affiliated middle and high schools. Two international schools have also been established. All of this appears to contradict central government’s desire to steer development zones away from policies of urbanization and towards a concentration on industrial upgrading. Such is the size of SIP, however, that it can accommodate both urbanization and industrial upgrading.

SIP exists in an interesting relationship with Shanghai, both competitive and more recently collaborative. A number of foreign-funded high-tech enterprises that settled in the park in its early years had chosen SIP because of low labor and land costs and proximity to Shanghai. As costs increased, however, many of them withdrew from the park (interview, SIP official, 28 August 2018). In recent years, all the policy pressure has been toward economic transition and upgrading. Nevertheless, attempts to upgrade inward investment were hit in 2017, when Shanghai City Government launched a movement to demolish so-called illegal small factories in its suburbs, as a result of which many moved into existing buildings in SIP. This had an inevitably negative impact on industrial transition in the park (interview, local officials and planners, 22 August 2018; interview, three owners of small factories, 22 July 2019). Now, however, production costs are high in both locations, and competition has shifted to the construction of new commercial and business centers and efforts to attract the head offices of service companies. Thus, a SIP Management Committee official told us that it was important to, “connect with Shanghai Free Trade Zone, copy its development, and promote the industrial transition and upgrading of Suzhou Industrial Park” (interview, 20 December 2018).

These challenges need, however, to be placed in perspective. SIP faced off severe competitive pressure from Suzhou New District. It saw its plans for upgrading buffeted by developments in Shanghai, but it appears now to look toward Shanghai’s zones in a spirit of collaboration (Phelps et al., Citation2020). The contrast with Chizhou is striking. There, administrations use development zones in internecine struggles for survival. SIP, on the other hand, now sails serenely forward, expanding and urbanizing, confident that people and investments will follow.

Reflections and conclusions on zone confusion and competitive urbanization

In this paper, we have argued firstly that development zones are seen to present a quick route to urbanization. In a relatively struggling prefecture-level city like Chizhou, officials fear that their city could go the way of others in the province and be disbanded and swallowed up by neighbors. They do, however, have very few policy brushes in their palette box from which to choose. Almost inevitably, they look to establish or expand development zones. But there is a limit to the number of companies that can be persuaded to invest, even when the “nest” is prepared for them and other inducements offered. The situation is different when it comes to building housing and other urban infrastructure in development zones. Here there are immediate financial gains available by taking advantage of the rent gap between the price paid to farmers for land and the onward sale to developers. Equally, there are planning gains as development zones present land for urbanization projects. This was illustrated in Chizhou by Anhui Chizhou High-Tech Industrial Development Zone, which, while failing to attract significant inward industrial investment, was considered to provide a suitable location for government offices as well as schools and housing. What we see here is local governments desperately trying both to boost industrial production at a time of slowing overall growth and attempting to attract new residents in an era of almost static demographic change.

Our second argument in this paper is that the institutional architecture of China’s party-state creates a form of competitive urbanization that often plays itself out in scalar struggles. The Chinese state has been described as a “dynamic, complex, heterogeneous and self-conflicting institutional ensemble” (Yang & Wang, Citation2008, p. 1039). Its constituent parts are as a consequence constantly embroiled in competitive struggles that are played out at both horizontal and vertical scales. In Chizhou, this is seen in the competitive creation of infrastructure to attract a pool of limited if not actually declining resources, often in tacit defiance of central government guidance. Jiangnan Industrial Concentration Zone, created at the behest of central government, was designed to eliminate excessive construction of development zones, but it remains a vast body of idle land in which industry is anything but concentrated. In nearby Qingyang County officials claim that the success of their park has provoked a form of “project theft” as the higher-level prefecture-city government allegedly attempts to wheedle companies out of Qingyang and into Chizhou’s more central high-tech zone. This bears testimony to the profusion if not confusion of zones at varying levels.

In Suzhou, on the other hand, the situation is on most counts a significant contrast. SIP’s Management Committee has been able confidently to map out grandiose plans for expansion of its urban infrastructure, confident both that high-end industries will continue to choose it as an investment location and that well-qualified workers will continue to want to live there with their families. Nevertheless, not even SIP has been spared the consequences of competitive urbanization. Rivalry with the city government’s Suzhou New District eventually contributed to the Singapore government’s partial withdrawal, but with continued fast economic growth in the Yangtze River Delta, both zones have been able to expand in recent years. In both struggling Chizhou and soaring Suzhou, urbanization is an unquestioned strategy to reap the economic rewards that stem from urban aggrandizement. In both locations, development zones are the leading vehicle for the realization of this strategy.

China has been fast urbanizing for some decades. In this paper, we have shown one significant way in which this is happening that differs from the more conventional paths laid out in the literature. This is not the demand-led suburbanization process as depicted by Shen and Wu (Citation2013). Nor does it equate precisely to the urban expansion occasioned by the construction of new towns, science cities, eco-cities, and the like. Designating development zones represents a different, important, and yet under-reported means of urbanization. It is, above all, a back-door urbanization driven by local governments competing to enhance their own position vis-à-vis both rival authorities and those above them in the urban hierarchy. Strict land conversion quotas mean that the establishment of development zones is one of the very few tools at the disposal of local governments to accelerate urban growth. Development zones are first and foremost designed to attract inward investment, and this remains an important aim, whether in Chizhou or in Suzhou. But zones are too numerous and inward investment is generally insufficient. Besides, urbanization projects promise immediate budgetary gains, population increase, and then, it is presumed, the investment that brings economic expansion. Local governments thus use development zones as weapons in competitive struggles for administrative survival and prosperity in the face of long-standing central government attempts to limit their number and recent efforts to re-exert central control. This panoply of measures and countermeasures appears to set the Chinese case somewhat at odds with policies and outcomes elsewhere, and it remains to be seen whether China’s export of its model of zones, as for example to various African countries, results there too in a similar process of back-door urbanization.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend special thanks to all those local officials who granted us interviews for their generous provision of time and information. Equally, we would like to thank academics in local institutions of higher education for their help in setting up interviews and coordinating other aspects of our field work in Chizhou. Without the kind help of all these people, this research would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Caprotti, Federico. (2014). Critical research on eco-cities? A walk through the Sino-Singapore Tianjin eco-city, China. Cities, 36, 10–17.

- Cartier, Carolyn. (2001). Zone fever’, the arable land debate, and real estate speculation: China’s evolving land use regime and its geographical contradictions. Journal of Contemporary China, 10(28), 445–469.

- Cartier, Carolyn. (2011). Urban growth, rescaling, and the spatial administrative hierarchy. Provincial China, 3(1), 9–33.

- Cartier, Carolyn. (2019). Exemplary cities in China: The capitalist aesthetic and the loss of space. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 60(4), 376–399.

- Chien, Shiuh-Shen. (2013). New local state power through administrative restructuring: A case study of post-Mao China county-level urban entrepreneurialism in Kunshan. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 46(1), 103–112.

- Finance. China [Zhongguo wang caijing]. (2019, May 29). Ministry of Commerce: The nationwide total of 219 national-level development zones become a major point of growth. http://finance.china.com.cn/news/20190529/4992789.shtml.

- Gao, Hong, & Tyson, Adam. (2020). Poverty relief in China: A comparative analysis of kinship contracts in four provinces. Journal of Contemporary China, 29(126), 901–915.

- Gong, Yue, & MacLachlan, Ian. (2021). Housing allocation with Chinese characteristics: The case of talent workers in Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62(4), 428–453.

- Guo, Jie. (2020). Promotion-driven local states and governing cities in action—re-reading China’s urban entrepreneurialism from a local perspective. Urban Geography, 41(2), 1–22.

- He, Shenjing, Li, Lingyue, Zhang, Yong, & Wang, Jun. (2018). A small entrepreneurial city in action: Policy mobility, urban entrepreneurialism, and politics of scale in jiyuan, China. International Journal of Urban and Rural Research, 42(4), 684–702.

- Jiang, Yanpeng, & Waley, Paul. (2018). Shenhong: The anatomy of an urban investment and development company in the context of China’s state corporatist urbanism. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112), 596–610.

- Jiang, Yanpeng, & Waley, Paul. (2020). Small horse pulls big cart in the scalar struggles of competing administrations in Anhui Province. China. Environment and Planning C, 38(2), 329–346.

- Jiang, Yanpeng, Waley, Paul, & González, Sara. (2016a). Shifting land-based coalitions in Shanghai’s second hub. Cities, 52, 30–38.

- Jiang, Yanpeng, Waley, Paul, & González, Sara. (2016b). Shanghai swings: The Hongqiao project and competitive urbanism in the Yangzi River Delta. Environment and Planning A, 48(10), 1928–1947.

- Li, Lingyue. (2015). State rescaling and national new area development in China: The case of Chongqing Liangjiang. Habitat International, 50, 80–89.

- Li, Zhigang, Chen, Yanyan, & Wu, Rong. (2020). The assemblage and making of suburbs in post-reform China: The case of Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 41(7), 990–1009.

- Li, Zhigang, Li, Xun, & Wang, Lei. (2014). Speculative urbanism and the making of university towns in China: A case of Guangzhou University Town. Habitat International, 44, 422–431.

- Liu, Yong, Yue, Wenze, Fan, Peilie, Peng, Yi, & Zhang, Zhengtao. (2017). Financing China’s suburbanization: Capital accumulation through suburban land development in Hangzhou. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(6), 1112–1133.

- Liu, Yungang, Yin, Guanwen, & Ma, Laurence J.C. (2012). Local state and administrative urbanization in post-reform China: A case study of Hebi City, Henan Province. Cities, 29(2), 107–117.

- Lu, Duanfang. (2006). Remaking Chinese Urban Form: Modernity, Scarcity and Space. Routledge. pp. 1949–2005.

- Miao, Julie. (2017). Housing the knowledge economy in China: An examination of housing provision in support of science parks. Urban Studies, 54(6), 1426–1445.

- Miao, Julie. (2018). Parallelism and evolution in transnational policy transfer networks: The case of Sino-Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP). Regional Studies, 52(9), 1191–1200.

- Miao, Julie, & Phelps, Nicholas. (2019). Featured town’ fever: The anatomy of a concept and its elevation to national policy in China. Habitat International, 87, 44–53.

- Miao, Julie, & Phelps, Nicholas. (2021). Urban sprawl as policy sprawl: Distinguishing Chinese capitalism’s suburban spatial fix. Annals of the American Association of Geographers.

- Miao, Julie, Phelps, Nicholas, Lu, Tingting, & Wang, Cassandra. (2019). The trials of China’s technoburbia: The case of the Future Sci-tech City Corridor in Hangzhou. Urban Geography, 40(10), 1443–1466.

- Ministry of Commerce. (2019). Principal economic conditions and indices of national level economic and technology development zones. Retrieved May 14, 2019, from http://ezone.mofcom.gov.cn/article/n/201905/20190502862821.shtml.

- MLR (Ministry of Land and Resources). (2005). Ministry of Land and Resources: verifying a reduction of 4,800 development zones at all levels. Urban and Rural Development [Chengxiang Jianshe], 1(19), 1. http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id = 11718322&from = Qikan_Article_Detail.

- NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission). (2018). China Development Zone Directory 2018. https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/lywzjw/zcfg/201803/t20180302_1047056.html.

- Ngo, Tak-Wing, Yin, Cunyi, & Tang, Zhilin. (2017). Scalar restructuring of the Chinese state: The subnational politics of development zones. Environment Planning C, 35(1), 57–75.

- Pang, Baoqing, Keng, Shu, & Zhong, Longna. (2018). Sprinting with small steps: China’s cadre management and authoritarian resilience. The China Journal, 80, 68–93.

- Pereira, Alexius. (2002). The transformation of Suzhou: The case of the collaboration between the China and Singapore governments and transnational corporations (1992–1999). In John Logan (Ed.), The new Chinese city: Globalization and market reform (pp. 121–134). Blackwell.

- Phelps, Nicholas. (2007). Gaining from globalization? State extraterritoriality and domestic economic impacts: The case of Singapore. Economic Geography, 83(4), 371–393.

- Phelps, Nicholas, Miao, Julie, & Zhang, Xiao. (2020). Polycentric urbanization as enclave urbanization: A research agenda with illustrations from the Yangtze River Delta Region (YRDR), China. Territory, Politics, Governance.

- Pow, Choon-Piew. (2018). Building a harmonious society through greening: Ecological civilization and aesthetic governmentality in China. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(3), 864–883.

- Qian, Junxi, & An, Ning. (2021). Urban theory between political economy and everyday urbanism: Desiring machine and power in a saga of urbanization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45(4), 679–695.

- Shao, Zinan, Xu, Jiang, Chung, Calvin King Lam, Spit, Tejo, & Wu, Qun. (2020). The state as both regulator and player: The politics of transfer of development rights in China. International Journal of Urban and Rural Research, 44(1), 38–54.

- Shen, Jie, & Wu, Fulong. (2012). The development of master-planned communities in Chinese suburbs: A case study of Shanghai’s Thames Town. Urban Geography, 33(2), 183–203.

- Shen, Jie, & Wu, Fulong. (2013). Moving to the suburbs: Demand-side driving forces of suburban growth in China. Environment and Planning A, 45(8), 1823–1844.

- Shen, Jie, & Wu, Fulong. (2017). The suburb as a space of capital accumulation: The development of new towns in Shanghai, China. Antipode, 49(3), 761–780.

- Shi, Chen, & Tang, Bo-xin. (2020). Institutional change and diversity in the transfer of land development rights in China: The case of Chengdu. Urban Studies, 57(3), 473–489.

- Smith, Graeme. (2013). Measurement, promotions and patterns of behavior in Chinese local government. Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(6), 1027–1050.

- State Council. (2003). State Council General Office notice concerning bringing order to all levels of development zone to strengthen the management of construction land. Retrieved September 2, 2003, from http://www.gd.gov.cn/gkmlpt/content/0/136/post_136504.html#7.

- State Council. (2005). State Council General Office forwards a notice from the Ministry of Commerce and other departments concerning some guidelines for the promotion of national-level economic and technology development zones moving toward an improved level of development. Retrieved May 18, 2005, from http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/g/200505/20050500094067.shtml.

- State Council. (2017). State Council General Office, concerning the promotion of development zones: some guidelines on reform and innovation development. Retrieved February 6, 2017, from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-02/06/content_5165788.htm.

- State Council. (2019). State Council, concerning the promotion of innovation in national-level economy and technology development zones: Guidelines on building a new high level of reform and opening up. Retrieved May 28, 2019, from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-05/28/content_5395406.htm.

- Wang, June, & Li, Mingye. (2019). Mobilising welfare machine: Questioning the resurgent socialist concern in China’s Public Rental Housing Scheme. International Journal of Social Welfare, 28(2), 318–332.

- Wu, Fulong. (2022). Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China. Land Use Policy, 112, 104412.

- Wu, Fulong, & Phelps, Nicholas. (2011). (Post-)suburban development and state entrepreneurialism in Beijing’s outer suburbs. Environment and Planning A, 43(2), 410–430.

- Wu, Qiyan, & Waley, Paul. (2018). Configuring growth coalitions among the projects of urban aggrandizement in Kunming, Southwest China. Urban Geography, 39(2), 282–298.

- Xue, Charlie Q.L, Wang, Ying, & Tsai, Luther. (2013). Building new towns in China: A case study of Zhengdong New District. Cities, 30, 223–232.

- Yan, Lianke. (2016/2013). The Explosion Chronicles (Carlos Roja, Trans.). London: Vintage.

- Yan, Yang, & Yuan, Chunhui. (2020). City administrative level and municipal party secretaries’ promotion: Understanding the logic of shaping political elites in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 29(122), 266–285.

- Yang, Daniel You-Ren, & Wang, Hung-Kai. (2008). Dilemmas of local governance under the development zone fever in China: A case study of the Suzhou region. Urban Studies, 45(5), 1037–1054.

- Yeung, Henry W.C. (2000). Local politics and foreign ventures in China’s transitional economy: The political economy of Singaporean investments in China. Political Geography, 19(7), 809–840.

- Yeung, Yue-man, Lee, Joanna, & Kee, Gordon. (2009). China’s special economic zones at 30. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50(2), 222–240.

- Yew, Chiew Ping. (2012). Pseudo-Urbanization? Competitive government behavior and urban sprawl in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 21(74), 281–298.

- Zhou, Jing. (2020, March 24). Interview with Lu Ming: Interpreting the ‘Delegation of [conversion] land approval in the context of urbanization and urban agglomerations’. Jiemian. https://www.jiemian.com/article/4163659.html.

- Zou, Yonghua, & Zhao, Wanxia. (2018). Searching for a new dynamic of industrialization and urbanization: Anatomy of China’s characteristic town program. Urban Geography, 39(7), 1060–1069.