ABSTRACT

This paper seeks to rethink the urban as an ecological formation. It argues that contrary to an emphasis on the built environment, articulated through refrains of capital, planning and design, cities are lived achievements, emerging through fabrications between human and other-than-human forces. Ecological formations are fleshed out in three modes: ecologies that involve the cultivated, feral and the wild. There are distinct forms of urban governance affiliated with each, taken as hybrids of biopolitical and vernacular practices. Rethinking cities as ecological formations enables a more radical understanding of the difference and heterogeneity of urban worlds than those on offer in urban theory. It signals a shift from animating urban geographies towards understandings of how other-than-human geographies are constitutive of urban worlds.

Three ecologies: reconfiguring the urban

The urban is bustling with life. Cattle are being embroiled in conflicts over traffic and mobility. Street dogs are emerging as public health concerns. Macaques contest what it means to be an urban denizen. These phenomena are beginning to pose new questions for specifying urbanicity and the meaning of urban life. Scholars ask who or what senses the city and the implications this has for understanding how the urban is apprehended and composed (Barua & Sinha, Citation2017; Metzger, Citation2014). Others query relations between life and the built environment, positing new ways of understanding the politics and ecologies of infrastructure (Barua, Citation2021; Parks, Citation2017). There have been attempts to rethink urban economic practices by foregrounding animals’ metabolic lives (Doron, Citation2020; Gutgutia, Citation2020), just as the presence of animals in cities has prompted new articulations of biopolitics and the governance of metropolitan space (Philip Howell, Citation2015). Taken together, these moves animate the urban and hint at how the latter is a formation co-fabricated with other-than-human life.

The urban has in fact been a central arena for the emergence of what might be termed an ontological turn in human geography and its quest to undo the binaries of nature/society and human/nonhuman that marked the discipline and the wider social sciences of its time. The first impetus of this turn, emerging almost twenty-five years ago as a thought experiment at human geography’s fringes, sought to posit “a trans-species urban theory” that reimagined cities through engagements with animal life (Philo, Citation1995; Wolch, Citation1996; Wolch et al., Citation1995). By recasting animals as marginal social groups, discursively constituted and subjected to socio-spatial inclusions and exclusions from the city, a range of ignored urban practices and power relations came to the fore (P. Howell, Citation2000; Palmer, Citation2003; Wolch et al., Citation2003). A second wave of scholarship, associated with “more-than-human” modes of inquiry (Whatmore, Citation2002), has pushed these provocations further. Emphasizing practice over discourse, shifting from representation to affect, and foregrounding a politics of knowledge rather than the politics of identity, this body of work sees cities and urban life as fashioned by heterogeneous alliances and contested by civic associations forged through more-than-human relations. The urban is fashioned and inhabited against the grain of expert designs, including those of capital, state, science and planning (Hinchliffe et al., Citation2005; Hinchliffe & Whatmore, Citation2006; Whatmore et al., Citation2003). In an affiliate register, scholarship in urban political ecology and urban studies, more broadly, has invigorated the question of urban nature (Gandy, Citation2006, Citation2015). Spurred by the thesis that urbanization is inherently about the urbanization of nature (Heynen et al., Citation2006), there is a sustained inquiry into the novel natures that emerge within an urban milieu (Gandy, Citation2013a; Jasper, Citation2018), their implications for practices of planning and design (Gandy, Citation2013b), and in enacting alternate imaginaries of urban living (Blecha & Leitner, Citation2014).

In this paper, we build upon these bodies of work to posit the urban as an ecological formation, that is, an arrangement of forces and intensities at once spatial, material and ethological, and constituted by heterogeneous forms of practice that include relations, if not alliances, with other-than-human company. An ecological formation, for us, is not something that denotes the peripheries or interstices of urban life, and neither should it occupy the margins of urban theory. Rather, the forces and relations that we draw attention to cut across most dimensions of urbanicity, whether these have to do with dwelling in and knowing the city, the assembly and repurposing of urban form, the reproduction of everyday life and the making of urban economies, as well as the ways in which cities are contested, regulated and governed. Our affirmation and departure from existing specifications are animated by some distinct concerns (also see: Gandy, Citation2021). In spite of considerable investment in attending to other-than-human life in cities, animals’ geographies or the sentient lifeworlds of other-than-humans have themselves received scant sustained inquiry. This, we argue, leaves one with an impoverished analytical repertoire for grasping how other-than-human ways of being and doing are constitutive of the urban fabric itself. Furthermore, we work with strands of urban scholarship that has sought to move beyond the built environment to foreground multiple other ways of dwelling (Simone, Citation2019; Simone & Pieterse, Citation2017). Urbanicity, we contend, must be seen as a lived achievement, where urban form is continually made and remade through the actions and practices of a range of beings. Finally, any such endeavor must be comparative if it is to account for difference: how ecologies diverge are constitutive of the shape and breadth of ecological formations. Comparison enables a much-needed disaggregation of the plural forms urban natures take, just as it fosters drawing meaningful analytical distinctions from different ways of being and dwelling.

Our exposition of ecological formations draws upon field and archival work in Delhi, a city that has been the subject of considerable intellectual investment in specifying the urban ecologies of the Global South (Baviskar, Citation2019; Nadal, Citation2020; Sharan, Citation2014; Sundaram, Citation2010). Four interrelated themes lie at the heart of our inquiry. The first concerns querying who or what constitutes an urban subject. Not only does this have implications for the ways in which urbanicity is specified, it provides insights into how urban worlds might be reimagined (Ruddick, Citation2017). Our second inquiry pertains to urban materiality, particularly relations between infrastructure and other-than-human life, in order to specify the bearings such life has upon urban form. Thirdly, we interrogate what urban metabolism – broadly understood as theorizations of the city based on the exchange, consumption and excretion of material flows – might begin to look like if we took, not abstract systems (Fischer-Kowalski & Hüttler, Citation1998), but material life and economic practices involving other-than-humans as a starting point. Lastly, we attend to urban biopolitics, the ways in which the urban is governed by regulating relations between human and other-than-human life. This analytical raster is mobilized by developing the concepts of the cultivated, feral and the wild as three distinct, yet interrelated, specifications of urban nature (Whatmore & Hinchliffe, Citation2012). The lives of cattle, street dogs and macaques in Delhi, provide windows into the cultivated, the feral and the wild respectively. Whilst this endeavor entails a specific city and a particular suite of interlocutors, they provide a useful, comparative and ethnographic vantage point for understanding ecological formations in their specificity and divergence, a point we return to, in the conclusion, to outline the wider implications of this work beyond the singular case.

Cultivated ecologies

We understand cultivation as a set of “creaturely entanglements” and disentanglements (Ginn, Citation2016, p. 2), where other-than-humans are brought into the field of people’s activity for purposes of human use. Contrary to cultivation being the inscription of human culture upon animate nature, as certain notions of domestication attest, we see cultivation to be a polyvalent field of relations in which both humans and other-than-humans participate. These relations are asymmetric, where people have a greater potential to exercise power and to set up the conditions and environments, within which the cultivated organism takes on its dispositions and forms. Cultivation enables a rethinking of the “production of nature” thesis (Smith, Citation1996), which contends that urban natures are “made” through human script, be it labor, capital, design or planning, for it allows accounting of both human and other-than-human work (Barua, Citation2018a) in the making of urban worlds.

Cattle on Delhi’s streets are an exemplar of cultivated ecologies. According to government estimates, there are 12,000 free-roaming cattle in the city whilst a population of nearly 9,000 animals are kept in metropolitan dairies (Government of India, Citation2019). Some of these are small-scale dairies located in “urban villages”, a distinct arrangement that has emerged because of the rapid and uneven urbanization of places that were villages fifty years ago. People from Jat and Gujjar castes (i.e. communities traditionally engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry) have been keeping cattle for generations, and continue to do so in spite of the enclosure and gentrification of erstwhile grazing land and relentless pressure from the state to relocate. Cultivated ecologies “signify the continuity between villagers’ own pastoralist past and the present” (Baviskar, Citation2011, p. 396), just as they reveal how, in South Asia, the urban and the agrarian are materially and economically co-produced (Gururani & Dasgupta, Citation2018). Cultivated ecologies, therefore, provide much needed antidotes to the neo-Lefebvrian thesis of planetary urbanization that takes the non-urban to have become “thoroughly engulfed” within patterns and pathways of the urban (Brenner & Schmid, Citation2015, p. 174).

The lives of free-roaming cattle allow us to query who or what senses and apprehends the city and how. In her seminal work on Delhi’s cattle, Amita Baviskar shows how cows’

bovine amble traces maps that are etched deep in memory – associations between particular places and nourishment: this dalao (garbage dump), that row of vegetable vendors. The everyday practices of urban cows delineate a carefully crafted route and set of activities: from home to forage and then to rest, often on road medians where the breeze from passing traffic helps keep flies away, before setting off homewards again. They swish their tails placidly, and rise unhurriedly to cross the road … It is not unusual to see a car stopped in the middle of the road, a disembodied hand stretched out of the window to feed stale rotis to a cow in the middle of morning rush-hour traffic. (Baviskar, Citation2011, pp. 395–396)

Cultivated ecologies bring a whole set of non-anthropocentric urban rhythms and mobilities to the fore (Ragavan, Citation2021). Following cattle on the city’s streets allows us to witness the city becoming minotaur, where the urban is woven by bipedal and quadruped movements that intersect and diverge, creating its own sets of rhythms, punctuations and flows. People stopping to provide for cattle on the dividers of roads, touching the feet of the animal as an act of reverence, before moving on to their workplace is a common feature of everyday life in the city. Such acts of provisioning and accommodation reveal how both people and cattle repurpose infrastructure to forge new, if not frail, commons (Ragavan & Srivastava, Citation2020). Yet, cattle’s mobilities are also a source of friction. Attempts to remove cattle from the city has been ongoing since colonial times (Anon., Citation1951), and the creation of specific zones for trades involving cattle was very much a part of the State’s planning imaginary (Delhi Development Authority, Citation1962). Bovine mobility became an even more poignant issue from the late 1980s onwards, as road culture in Delhi underwent a fundamental shift, gravitating towards new discourses of consumption and speed (Sundaram, Citation2010). This led to a major intervention in 2001, when certain sections of the public in New Delhi petitioned the state’s High Court to end “the menace of stray cattle”, for cows, they argued, “squat on roads and throw traffic out of gear, which leads to accidents” (Baviskar, Citation2011, p. 399). The Delhi High Court, in response, ordered the removal of cattle from the city, stating, “The capital city of Delhi should be a show window for the world. The stray cattle on the roads gives a wrong signal” (Singh, Citation2000).

Such frictions are not simply over cattle but have to do with questions of urban livelihoods and ways of being. For many communities, rearing cattle is part of their traditional vocation and they continue to do so in spite of all odds. For others, it is a means of dealing with precarity. Household-led urban dairies, as opposed to commercial dairy farms, are typically family-run enterprises that operate informally, in a gray zone between what is deemed legal and the illegal. The division of labor in caring and tending to cattle is organized through tacit codes and personal arrangements. Milk from the animals is usually sold in the neighborhood or, increasingly, to sweet vendors trading in dairy products. In such enterprises, cattle play a role in enabling social reproduction – the “fleshy, messy, and indeterminate stuff of everyday life” through which the family and the labor force is sustained (Katz, Citation2001, p. 711). The importance of such practices is witnessed in the persistence of urban dairies even after attempts for more than a century to drive cattle out from the city. In 2011, ten years after the Delhi High Court order, there were over 2,000 dairies that continued to operate in the city, many that opened again after being closed down by the Municipal Corporation (Nath, Citation2014).

Human labor is, however, only part of this story of social reproduction. Cattle, one can argue, are invisible workers in such informal economies, which tap into the “metabolic work” (Barua, Citation2018b) the animals perform. Often left to fend for themselves, cattle in Delhi graze amidst the ruins of capitalism: frequenting ephemeral garbage heaps, municipal waste collection depots and landfills, and foraging on the detritus of commodities (). Bovine bodies and their metabolism, therefore, become conduits through which waste re-enters circuits of value. Furthermore, as our fieldwork reveals, the presence of urban dairies spawns a whole other set of economic practices in the city. Many waste-pickers, working in the highly informal and precarious waste sector, salvage vegetables and half-consumed food to sell onto dairy owners, who use such material as cattle feed. As waste, and the waste commons, rapidly become enclosed in urban India (Gidwani & Reddy, Citation2011), salvaging feed for cattle begins to take on a more organized form, constraining the limited opportunities waste-pickers have to earn more than their already meagre wages.

Whilst particular economic practices emerge through relations between bovine metabolism, informality and waste, the garbage heaps in which the animals graze are also toxic. They aggravate and reproduce existing urban inequalities. Cows ingesting plastic, when grazing on waste, has become a major concern for the animals’ welfare. Twenty to thirty kilograms of plastic are routinely found in the stomachs of the city’s bovines, a problem that is now country-wide and which has earned India’s urban cattle the moniker “plastic cows” (Nagy, Citation2020). People often put wet waste in plastic bags, much of which is single-use plastics. Poor segregation that comes about with the privatization of the city’s waste sector, coupled with the rampant enclosure and gentrification of erstwhile grazing land, creates conditions that lead to plastic ending up in bovine stomachs. As a result, urban dairy owners are further stigmatized, for many consider their milk to be of inferior quality. Their produce fetches lower prices on the market, resulting in a cheapening of urban nature – a decline in the price of commodities and a degradation in the ability to reproduce urban life (Moore, Citation2017), both human and other-than-human.

There is a distinct mode of urban governance in relation to cultivated ecologies. This does not necessarily follow the same biopolitical logics as those located in Western modernity, thus enabling one to query ways in which biopolitics is extended to other-than-human bodies and populations (Biermann & Mansfield, Citation2014). Oftentimes, the urban is governed, not through biometrics and calculation, but via “codes of appearance” or an aesthetic order of what should or should not belong (Ghertner, Citation2015). Delhi’s dairies, since colonial times, have been construed as sources of filth, squalor and disease. Equally, planning imaginaries have long associated cattle and dairies with “the rural” and have repeatedly sought to eliminate them from the city (Sharan, Citation2006). Codes of appearance – cattle despoiling a world class city – have been integral to the Delhi High Court’s order to relocate dairies elsewhere (Singh, Citation2000). Rather than a biopolitics of managing and securitizing life, what one witnesses is a “rule by aesthetics”, an attempt to govern life by redistributing the sensible (Ghertner, Citation2015). Furthermore, the bio- and anatomo-politics of bovine bodies is integrally linked to the logics of capitalist production, a point glossed over by much work on more-than-human biopolitics. Commercial dairies intensively tap into the metabolic work other-than-humans perform. Cattle become beings solely for the production of milk and, therefore, bovine life becomes synonymous with the accumulation of dead labor (Federici, Citation2004). The cheapening of urban nature, on the other hand, produce cattle as surplus bodies, where lives are cast outside as waste whilst cattle feed on, and live off, waste. Practices of managing cultivated ecologies, therefore, are hybrids between the biopolitics of capital and a rule by aesthetics, practices that begin to look different if we turn to other ecologies of the city.

Feral ecologies

Street dogs in Delhi are a striking example of ecologies that unsettle domesticity, particularly notions of the domus inherited from the West and normalized as a universal standard of urban inhabitation. Estimates vary, but counts suggest that there are between 300,000 and 500,000 dogs on the city’s streets (Anon., Citation2016). Caught up in practices of controlling urban canid populations, the State refers to these animals as “strays” whilst others prefer the terms “street” or “free-ranging” dogs, as they form companionate relations with pavement dwellers, street vendors and other members of the public. Urban canids are often bound up with loose forms of ownership, not necessarily tied to a home. The latter association of dogs with family and the private sphere, as Philip Howell’s foundational work shows, is a Victorian invention of the late nineteenth century. Material and imaginary geographies of the home rendered dogs familiar, converting a street animal to a domestic pet through a wider apparatus of rescue homes, dog shelters and reformatories (Howell, Citation2015). A look at street dogs, on the other hand, opens up ways for developing a different grammar of urban life, one attentive to difference and to divergences that constitute urbanicity.

The feral, we argue, is a contested but productive term for engaging with the ecological formations street dogs bring to life. In its majoritarian register, the feral is a term that has licensed the exercise of violence toward both humans and animals (Wadiwel & Taylor, Citation2016), partly because ferality is tethered to a burdened history of designating convicts or criminals on the loose. In a more confined, strictly ecological sense, the feral designates those animals that are once again subject to natural selection after a history of artificial selection by human agency. In contrast, the wild is subject to natural selection alone whilst the domestic is the product of artificial selection. We retain the term “street dogs” as opposed to calling them “feral dogs”, as the latter brings in fraught connotations that we neither adhere to nor prescribe. Rather, we want to think with ferality, as it brings to life important tensions and viewpoints in specifying ecological formations. To think with the feral is to reveal how oppressive social orders and majoritarian categories produce other-than-human life. At the same time, the feral enables actualizing other ways of dwelling and inhabiting a city. In a sense, our invocation of the feral harks back to Nietzsche’s philosophical anthropology. Alluding to the figure of the “fugitive” or “deserter”, Nietzsche (Citation1982) deployed ferality as both diagnostic, revealing the organic beneath social constructs, and as therapeutic, invoking ways of being. Feminist and queer studies put this twofold aspect of ferality to generative use. By slipping the leash of domesticity, the feral enables questioning the gendered regulation of bodies to the domestic sphere and their exploitation by patriarchal and heteronormative structures (Belcourt, Citation2016; Montford & Taylor, Citation2016; Sandilands, Citation2017).

Delhi’s urban canines, a large number of which have never been formally homed, bring to life a different set of concerns regarding who or what constitutes an urban subject. Street dogs forage in a liminal zone: obtaining food from people through soliciting or by direct provisioning and often, at the same time, scavenging in garbage heaps. Many Indian street dogs revert to what might be seen as “remnant” canine behavior. They form packs, held together by sentient, intra-species bonds and hierarchies seldom witnessed in the solitary, familial pet. Such packs are not “random associations of unfamiliar dogs” but a form of sociality that canids forge through active choice. They tend to cluster during the mating season, “even at the cost of facing competition over food”, but disperse at other times of the year, choosing to forage singly or in association with preferred partners (Majumder et al., Citation2014, p. 7). Scarcity or competition for resources can lead dogs to start hunting – rats for instance – although this is usually solitary behavior rather than pack activity. When the latter manifests – and there are reported instances (Sinha, pers. obs.) – it involves strategies that require an understanding of one another and of a collective, including the cornering of prey and role-taking, wherein some individuals cut off the quarry whilst others give chase. Here, there is considerable scope of exploring how the enclosure of waste, as a distinct urban phenomenon in Delhi (Gidwani, Citation2015), might trigger feral ethologies, resulting in free-ranging canids expressing a suite of behaviors that are otherwise lost to domestication.

Adept at reading bodies and sensing their everyday environments in perceptive ways street dogs, one could argue, are a different incarnation of the urban flanêur, grasping the transitivity of the city as everyday process through canine dispositions and temperaments. Whilst it is difficult to articulate what such a flanêur might witness and apprehend, ethological studies on street dogs in India provide helpful cues. For instance, dogs living in busy streets and congested bazaars, with their intensities of traffic and pedestrian movement, respond differently to human action than those inhabiting residential neighborhoods. Street canids in crowded spaces are more reticent to approach strangers, responding only when provided food, for they inhabit a milieu where encounters are transient and often laden with frictions. In contrast, canids in residential areas, who tend to be provisioned, interact with strangers more readily (Bhattacharjee et al., Citation2019) (). Dogs thus read people, their emotions and affective dispositions. They reveal how other-than-humans do not simply occur in the city but have their own canine understandings of neighborhoods, localities and streets. Such understandings are different to that of a bipedal, ocular human being, but in no way is this an impoverished view of the city, for people are but only a part of the combinatorial entity that one calls “the urban” (Amin & Thrift, Citation2017).

Figure 2. Street dogs in a residential neighborhood eliciting affection from a human (Photo: Maan Barua).

We might extend this perspective further by turning to relations between street dogs and the material environment. Whilst cattle track a pastoral topography of the city that is ambulatory, canid movement result in the formation of other-than-human urban territories: places marked and defended by street dogs, canine places amidst metropolitan orderings of space. Denning, for example, is an activity that is vital for the reproduction of street dogs, not fully expressed in the familial pet. Dogs actively select dens, but these are not mechanistic choices. Rather, as ethologists argue, canids choose places “in which they are comfortable” (Majumder et al., Citation2016, p. 4, emphasis added). Females form dens in the basement of buildings, in corners of markets, on railway platforms and by the roadside. A number of factors dictates this transformation of the built environment into beastly dwellings. It includes access to water – such as dripping taps – that dogs seek out. Denning in the thick of habitation can also be a choice made to reduce competition with mesocarnivores, like jackals, or predators, such as leopards, who pose threats to canine litters. Mothers can become aggressive while guarding pups and such aggression marks a territorialization of urban space by invoking affects of fear in their human counterparts (S. Srivastava, pers. comm.).

Studies also indicate that pregnant females prefer obtaining food through solicitation – eliciting affects of empathy in people – rather than scavenging in dustbins and ephemeral garbage heaps (Majumder et al., Citation2016). Urban metabolic environments thus become affective, contingent on canine movement, bonds and pack behavior, a cartography of affect drawn in auditory, olfactory and gustatory modes. They emerge in spite of hylomorphic logics of the built environment, logics that take building to be the product of the stamping of human ideas upon inert matter. In one sense, when seen from the viewpoint of design, urban metabolic environments that dogs bring into being are “unintentional landscapes” (Gandy, Citation2016), that is, landscapes in spite of themselves. If the emphasis is shifted to that of a canid flanêur, however, the urban is more akin to an other-intentional landscape, forged through dogs’ own desires, sentience, actions and meanings.

These affective cartographies may be small, but they can have significant social and biopolitical consequences. Sounds of dogs barking are a nocturnal refrain in Delhi. Vital for canid territorialisations, barking can be the ire of the wealthy urban middle class for it untunes their aesthetic of Delhi as a “global city”. Complaints about noise and the loss of sleep are frequent, sparking reactionary bouts of capture and “stray dog” sterilizations. Street canid territorialisations also generate frictions when people take their dogs for walks, a phenomenon that is on the rise with the pet industry boom in Delhi. Incidents of people being bitten when territorial fights between packs ensue or when strangers move through a street dog territory at night, especially on motorcycles, are not infrequent. Delhi registers over 60,000 dog bites each year (Anon., Citation2015), although a majority of interactions with people are typically submissive.

Rabies has long been a concern in India, and the state resorts to strategies of control that target both canids, through vaccination and sterilization, and people, through immunization. In 2018–2019 alone, civic authorities sterilized over 27,000 dogs in the city (Anon., Citation2019a). Histories of canine control in India have operated less through the Western biopolitical model, entailing a supple microphysics of discipline (Howell, Citation2015), but more through racial and colonial logics, vilifying both street dogs and the people they associate with. The cruel invention of the derogatory term “pariah”, denigrating urban canids and dehumanizing people of marginalized castes, runs through these histories. Episodic street dog culls, continued by the postcolonial state well into the 1990s (Nadal, Citation2019), is a form of casteised, colonial necropolitics. Culling programes, in fact, still unfold illegally, sometimes through action by members of civil society or carried out by the State in the informal sphere (Narayanan, Citation2017). Canine biopolitics here does not only have to do with a lack of regulation or licenses; rather, it can be biopolitics in a deregulated mode, operating informally and in a gray zone between the legal and illegal.

Yet, street dogs can also form alliances with people, despite the biopolitical measures enacted by the state. Dogs incorporate people into their worlds, be it those who feed them regularly or indirectly provision them by regularly dropping garbage in bins and waste dumps. Dogs also provide worlds for others, crafting kinship in the contact zones where street dogs and people meet. The city is filled with small stories of the poor – cleaners working in markets, tea stall vendors and wage-labourers employed as security guards – who bond with dogs, taking great effort to feed them despite their slender pockets. And there are the homeless, who have virtually nothing and yet share their meagre food with their almost invariably present canid families. These are small stories of finding company, taking breaks from a demanding day, and affective nourishment amidst weary urban lives. Street dogs too have been shown to build trust and affiliation on the basis of affection rather than food (Bhattacharjee et al., Citation2017), suggesting that intimacy and contact matter for both people and canids. Such human–street dog alliances can become infrastructures of security, occasionally for the middle classes living in gated colonies but far more importantly for the poor in their makeshift dwellings (Ragavan & Srivastava, Citation2020), as dogs are experts at sensing affects, those of danger, intrusion and even familiarity, for that is where the uncanny lies.

Alliances between street dogs and people provide the charge for reconstituting the demos in urban epidemiology, an endeavor vital for “decolonizing rabies” (Srinivasan et al., Citation2019) and undoing its casteist and colonial biopolitical logics. Such a demos must be porous to modes of urban dwelling that do not recourse to domesticity and see feral ways of being not as predatory formations or populations turned into loose ends, but as sentient beings capable of composing other ways to inhabit the city. Such a proposition might will not easily sit with elite, exclusionary aesthetics and punitive biopolitics of the global “world-class” city that has come to mark Delhi (Baviskar, Citation2019), but agonisms can be generative for thinking the urban otherwise.

Wild ecologies

In contrast to the cultivated and the feral, the wild might be associated with a greater degree of autonomy and independence from the domestic sphere. However, its trajectories are intimately bound up with infrastructural environments and the metabolic intensities of cities. Our evocation of the wild is less about the return of nature to cities and more to do with what Jennifer Gabrys terms a becoming urban of the wild, “as part of the urban political ecologies in which they are situated and to which they contribute” (Gabrys, Citation2012, p. 2925). The process of becoming urban reworks the spatial fetishism, taxonomic absolutism and nonhuman exclusivity traditionally associated with the wild as that which is “out there” removed from the “in here” of society (Buller, Citation2014). It is a process that might be understood as “synurbisation”, where creatures have a greater association with urban ecosystems than elsewhere (Francis & Chadwick, Citation2012) and commensality, where wildlife negotiate urban spaces by taking advantage of anthropogenic food (Webber, Citation2017).

There is a specific history to the urbanization of Delhi’s rhesus macaques. In the mid-1950s, rhesus macaque populations across north India were predominantly rural, “rarely seen in parks, gardens … middle and upper class residential areas” (Southwick et al., Citation1961, pp. 707–708). A decade later, however, rural populations declined significantly, largely due to capture for commercial trade. In the fifty-odd years between the mid-1920s and 1970s, India had caught and exported over two million monkeys (Mohnot, Citation1978), a figure unimaginable for any other species of primate anywhere in the world. As macaques in towns and cities were deemed unfit for experimental purposes, on grounds that they may harbor disease, rural populations were targeted for capture. Depopulation of rural macaques and the creature’s adaptation to cities, where they lived in a “niche” comparable to that “of commensal rodents”, led to a gradual “urbanization among the rhesus populations of northern India” (Southwick & Siddiqi, Citation1968, p. 203).

In 1978, the actions of primate conservationists and animal welfare groups (Anon., Citation1978), with support from then Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai (Anon., Citation1977; Sinha, Citation1995), led to an export ban. The rhesus populations recovered; localities, such as Tughlakabad in Delhi, witnessed a 76% rise in populations in five years (Malik, Citation1989), and by the early 1990s, macaque numbers across northern India increased fourfold. The rhesus had shifted from semi-commensal habits to full-fledged commensality: animals that earlier obtained “natural” forage and avoided people in parts of their territories were now more or less reliant on people for food. “Commensal monkeys”, ecologists observed, “now represent the largest population of rhesus in north central India” (Southwick & Siddiqi, Citation1994, p. 228).

The becoming urban of the rhesus macaque reveals another set of relations with the material and infrastructural environment to that of cattle and street dogs. Infrastructures, one could argue, now form a part of macaques’ urban habitus: modulating the creature’s sentient and sensory habits and furnishing a medium of inhabitation or habitat. In Delhi, macaque troops frequently cross crowded streets through the tangle of overhead electric wires, using these infrastructural pathways to negotiate the city. Macaques exapt cables and wires, that is, repurpose infrastructure for their own simian mobilities, taking the latter in directions completely unanticipated in their inaugural installation and intended assembly. Macaques’ adaptation to the infrastructural environment has in fact led to the animals shifting from a rural terrestriality to an urban arboreality. Enmeshments between macaques and electric infrastructures also have socio-political effects: individuals sometimes get entangled in wires and transformers, tripping circuits and leading to power outages that can last for hours. Infrastructure-providers, therefore, now increasingly work with wildlife rescue NGOs to deal with macaques whilst conducting electrical repair work.

The synurbisation of macaques is also intrinsically linked to the metabolic intensities of cities. For instance, processed food – including crisps, ice-cream and fried savories – now constitute a large proportion of urban macaques’ diets, obtained either through salvaging in rubbish bins, snatching from people and raiding homes, or through active acts of being provisioned. Delhi witnesses large-scale feeding of macaques, especially by devotees of the Hindu deity Hanumān or by people who seek to rectify malefic effects of planets on their astrological charts. On the instruction of priests and astrologers, people offer fruit, pulses and cooked food to macaques to receive punya, a diffuse cleansing merit, and through this dān or gift, cosmic energies are harnessed for the individual’s protection. On Tuesdays and Saturdays – days considered auspicious in terms of Hanumān worship – pedestrians stop and buy bananas from street vendors, handing them out to awaiting macaque troops (Barua et al., Citation2021).

Provisioning, and the anthropogenic feeding grounds it generates, has strong bearings on macaques’ ethologies, group dynamics and territories (Sinha & Vijayakrishnan, Citation2017). Macaques distinguish between natural and nutritionally rich, provisioned food (Barua & Sinha, Citation2017), even altering their foraging strategies to access the latter. The patterned activities of urban macaques suggest an awareness of daily and weekly rhythms of provisioning. Most significantly, they can modify their behaviors to elicit affects in people. Bipedal soliciting – standing erect on their hind legs whilst making contact coo calls for food, arms outstretched – is a strategy certain individuals have learnt to deploy in order to spark offerings of food. Corporeally mirroring human bodies, macaques, through postural echo, evoke feelings of sympathy and philanthropy in people (Deshpande et al., Citation2018). These behavioral “innovations” vary according to individual temperament and can be learnt through emulation (Sinha, Citation2005). Such behavioral repertoires, distinct for urban macaques, suggest how becoming urban also leads to the formation of new subjectivities.

Distinct practices of economic make-do emerge with provisioning. Banana vendors – typically individuals living at the margins of urban life – cultivate proximities with macaques, sometimes providing them food and water so that the animals dwell around their make-shift stalls. Macaques draw in customers – devotees who buy fruit to feed the animals – triggering both a transaction of commodities for money and trans-actions between human and simian bodies (Barua, Citation2018a). Street vendors in Delhi typically sell over seventy dozen bananas a day, and in these precarious economies, macaques are vital for the realization of value. In other words, relations between vendors and macaques become infrastructural (Simone, Citation2004), subtending the practice and reproduction of urban life. Whilst written out of accounts of urban economy, be it that of informality or jugaad, i.e. an “innovative fix”, these improvisatory relations show how “the economic” can inhere through more-than-human collaborations and affective exchanges ().

Figure 3. Provisioning macaques. The makeshift stall of a banana vendor is on the left (Photo: Maan Barua).

Like the cultivated and the feral, the commensal and the wild too become object-targets of urban governance. At work here is a hybrid mode of biopolitical and vernacular practices, which do not neatly settle into a Western model of regulation, calculation and surveillance. In March 2007, the Delhi High Court ordered the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) to rid the city of its macaques in three months (Kumar, Citation2007). The order came on the back of widespread complaints regarding the city’s “monkey menace” – macaque incursions into offices, buildings and homes, resulting in agonistic encounters – expressed largely by a vocal urban elite. The unfortunate demise of New Delhi’s Deputy Mayor, when he fell off a balcony whilst trying to ward off macaques (Anon., Citation2007), fueled the capture and relocation drive. State dictate was again steeped in an attempt to “rule by aesthetics” (Ghertner, Citation2015) – to actualize a vision of a modern, clean and globalized capital, where macaques were not to be seen on Delhi’s streets.

Posited as a permanent solution, capture and relocation were implemented by private contractors and trappers under the aegis of the MCD. In three years, they captured 10,000 animals but, as an official remarked, “the problem does not show signs of ending anytime soon” (Anon., Citation2010). To date, over 20,000 macaques have been captured and relocated, but the municipal agency has begun to concede defeat, claiming that in their battle with macaques, “the simians seem to have won” (Anand, Citation2012, no page). Capture has led to other macaque troops moving into evacuated territories, including previously unused areas of human habitation. Individuals have even learnt to get the better of traps. As a result, monkey-catchers are reticent to take up MCD contracts. Everyday practices of offering food continue unabated, some devotees even stating they are willing to pay fines, but nothing can come in their way from appeasing Hanumān or following astrological remedies. Behavioral adaptations of the rhesus and its everyday alliances with people thus successfully subvert State logics and its attempts to control wild life.

Ethnographic attention to existing practices shows how State-led biopolitical strategies to expunge the city of macaques dovetail into vernacular practices of keeping the animals at bay. The latter involves alignments between people and more-than-human company and draws from knowledge practices that are not statist in their formulation. The hiring of captive langurs – long-tailed colobine primates – to ward off macaques from gated colonies of urban elites, government ministries and the residences of high-profile politicians, bureaucrats and judges, is a case in point. The colobines, trained by handlers or langur-wallahs, would be released in select localities to aggressively ward off the much smaller macaques. A form of collaborative labor, entailing both human and animal work (Barua, Citation2018b) – langurs and their handlers – put in nine-hour shifts a day to keep premises macaque-free. Whilst effective, the practice was banned by the government in 2014 when issues of animal welfare and illegal wildlife trade were raised. Amidst public outcry, the MCD decided to hire langur-wallahs to perform the work of the langurs themselves. Erstwhile handlers now work as langur-mimics, employed in offices and residential areas under precarious contracts, where they imitate the sounds of colobines to keep the rhesus at bay. These vernacular practices attempt to work with more-than-human forces rather than upon them. They reveal how the State can ally with or incorporate other, non-statist practices, providing them with a “minor position” within its institutional apparatus (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1986, p. 38).

In fact, the very designations of “commensal” and “wild” can be mobilized for different ends in urban controversies surrounding macaques. Tired of removing macaques from the city, the MCD argues that macaques are not “stray animals” but “wildlife”. The management of their populations and habitat, the civic body maintains, is thus the responsibility of the state’s forest department. In response, the department argues that urban macaques have become “commensal in nature”. By having “evolved by adapting themselves to live close to human habitations” they can no longer be considered “wild” (Anon., Citation2019b). The onus of regulating macaque urban macaque populations, they contend, is then on the civic body. Commensality and wildness are thus not only descriptors of urban ecologies, they become terms mobilized by different state bodies to deflect responsibilities in managing macaques, all of which plays out in a field where macaques overtake human action and render the State’s attempt to police them futile.

Ecologies of comparison

Cultivated, feral and wild ecologies thus provide inroads for animating the urban, not simply by registering the presence of animals in cities but to see how the very fabric of urbanicity, from its infrastructure to material environment, metabolic intensities to ways of reproducing everyday life, is forged with other-than-human life. The urban, we thus argue, is an ecological formation: a spatial, material and ethological arrangement of forces and intensities of phenomena constituting them. Ecological formations take the urban to be a lived achievement, foregrounding a whole other set of vantage points on how cities are fashioned and made. They reveal how planning and design are only one aspect to the rise of urban form. Everyday practices of dwelling and habitation, combinatorial in that they include alliances and relations with other-than-human company, play an equally important role. The cultivated, feral and the wild enable disaggregating other-than-human life to show how, within the same city – let alone across them – the practices, ecologies and politics are different and cannot be subsumed under the singular rubric of “nature”.

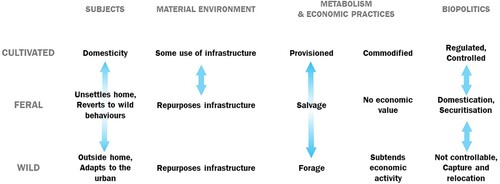

The triad of the cultivated, feral and wild, again, is not a taxonomy but a set of concepts that expand thinking of the urban as an ecological formation. They are creative rather than representational, drawing out productive relations, connections and tensions that stem from an ethnographic and ethological inquiry into urban life. Furthermore, the triad is not a typology, where categories are reified and immovable, but a topology, where ecologies are situated and what constitutes cultivation, ferality or wildness is contingent on the relations in which a creature is enmeshed (). In this sense, we see such categories as fluid, rather than stable, placeholders, amenable to both change and breakdown. As a heuristic, the triad enables disaggregating urban nature or other-than-human life and, in fact, as loci of comparison, they “work through ecologies” (Choy, Citation2011, p. 12), with the world and never cleaved from the situations of their production. Our emphasis in this paper has been on the variations of ecological formations, rather than fixing them in place, while attending to such variations, we believe, is crucial for a nuanced account of many facets of urbanicity.

Figure 4. A simplified heuristic showing the cultivated, feral and the wild, and their respective relations. The triad is a topology rather than typology; as beings shift from one category to another so do their prospective relations. Arrows are indicative of such shifts as well as gradations and overlaps between categories.

The first of these formations pertains to questions of who or what is an urban subject and, therefore, how urban worlds are known and imagined (Ruddick, Citation2017). Cultivated ecologies are closely linked to the domestic sphere, and pets – a category we do not discuss in depth – are exemplary. Yet, cultivation also entails more than the domestic sphere. The pastoral topography of the city that cattle track challenge ideas of planetary urbanization and point to how processes of urbanization in India might be thought of as an agrarian question (Gururani & Dasgupta, Citation2018), where the rural and urban are materially co-produced. Ferality, on the other hand, marks a break from the domestic sphere, whether in terms of exhibiting novel behaviors or by unsettling the idea of home. Street dogs, as urban subjects, show how there are other forms of belonging and inhabiting a city not necessarily tethered to the gated dwellings associated with the Western polis. Not only do street dogs belong, they furnish worlds for others, forging other ways of being for people in the city. With the becoming urban of the wild, we witness a whole other set of adaptations, notably through commensality. In Delhi, the latter is strongly mediated by cultural and religious practices, where macaques become intermediaries to supernatural worlds. All of these have important repercussions for what urbanization is and means. By not taking such forces and potentials seriously, we miss out on a whole raft of phenomena that continually make the city in the everyday.

A second set of features of the urban that the cultivated, feral and the wild foreground have to do with material environments, particularly the relations between other-than-human life and infrastructure. By foregrounding dwelling and inhabitation, we open up different ways through which urban space is made and unmade. For instance, cattle repurpose the dividers of roads for resting and grazing. Cattle’s mobilities also become points of friction with the State and the kinds of automobility that capitalism promotes. With street dogs, where shelter is not always a given, their ability to repurpose urban infrastructure becomes even more important, whether it is for sites to den or for sources of water such as dripping taps. Unlike cattle, street dogs are territorial, drawing affective cartographies of the city along and against the grain of designs. Whilst the territorial activity of dogs can sometimes hinder the mobility of pedestrians, especially at night in unfamiliar neighborhoods, to many, dogs are infrastructures of security, providing safety in situations where the State is unable to do so. With macaques, we see a different repurposing of infrastructure, notably in the ways they use cables and wires to negotiate a city. As the existing practices of infrastructural repair and maintenance show, electricity providers now have to take simian mobility into account. Cultivated, feral and wild ecologies thus point to a wider ontology of infrastructure (Barua, Citation2021), where infrastructure is both habitat and that which can modulate habits of other-than-human life. These are variegated process but they all point to the ways in which material environments are taken in directions other to what is anticipated in infrastructure’s inaugural assembly, often involving other-than-human innovations.

A third set of vistas that the triad opens up has to do with the metabolic intensities of cities and their attendant economic practices, which are inexorably linked to material environments. The cultivated has to do with distinct forms of commodification, which includes cattle as lively commodities, as well as the commodification of feedstuff that go into their maintenance and upkeep. At the same time, the metabolic work that cattle perform show how other-than-human bodies play a role in bringing urban waste back into circuits of value. These are critical aspects to urban economies that much work on “the economic”, emphasizing questions of capital, which gender and class sometimes gloss over. Although intimately bound up with the metabolic life of a city, street dogs are not commodified. Hence, there is variation in terms of how the metabolic intensities of cities are to be grasped and understood. The commensal relations between people and macaques, on the other hand, show how trans-actions between human and simian bodies can become infrastructural, providing a scaffolding for economic make-do, especially when mediated by cultural and religious practices. Ecological formations thus call for not only thicker ethnographies of urban metabolism, attentive to other-than-human life, but also for a more expanded notion of what constitutes the oikos in economy. This reworking of oikos reveals how urban economies are constituted by the ecological from the very outset (Barua, Citation2018a). They open up new ways of specifying the economies of cities, whether to do with informality, forms of make-do or capitalist development.

Finally, the cultivated, feral and the wild allow us to disaggregate how urban governance and the biopolitics of administering other-than-human life operate. When refracted through the cultivated ecologies of cattle, relations between biopower and capitalist accumulation come into view. Here, biopower becomes a question of accumulating dead other-than-human work or of casting aside surplus bodies as waste. At the same time, not all urban dairies are run along capitalist lines. They involve other arrangements of extracting surplus, which can include the organization of labor along family lines. With the feral, we see another set of biopolitical practices that have less to do with enrolling other-than-human life into the realm of accumulation and more to do with securitization. In case of street dogs, the latter proceeds through both State-led mechanisms of neutering as well as control in an informal, deregulated, vigilante mode. In a similar vein, attempts to expunge macaques from the city also proceeds through a hybrid of biopolitical imperatives and vernacular practices, as, for example, enrolling langur-handlers to keep premises free of simians. In the case of Delhi, the imperative to “rule by aesthetics” (Ghertner, Citation2015) cuts across interventions in all three ecologies. It might be commonplace to state that there is a heterogeneous set of logics at stake in the governance of urban life, but what is critical is to not reduce these to a unitary logic of biopower derived from a Western model. The differences at stake count and matter, for it is these specificities of practice that are constitutive of what one calls the urban in all its diversity.

The urban as an ecological formation

To conceptualize the urban as an ecological formation, we have argued, is not simply an endeavor of bringing animals back into the city and into social theory, but to propose more nuanced understandings of how the urban is made and remade. Our methodologies and analyses do not refer to a hylomorphic notion of making – the stamping of human ideas upon an inert world – but to making through practice, through dwelling and inhabitation. To this end, ecological formations are not a series of locations on which attributes are piled but arrangements of forces and intensities, at once spatial, material and living, which constantly undergo ingestions, mergers and ruptures. The themes of urban subjects, materiality, metabolism and biopolitics, outlined in this paper, enable mapping into certain features of such formations, just as the triad of the cultivated, feral and the wild foster the variation that are part of these formations.

The phenomena that we have described and analysed are in no way restricted to the periphery of the city. If they appear peripheral, it is because they lie outside the vision of urban theory, given other-than-human life has largely been ignored in mainstream urban work. As Amin and Thrift (Citation2002, p. 40) have remarked, “too often writings about the city have taken hold of one process and presumed that it will become general, thus blotting out other forms of life.” This trend often stems from starting with analytics cities of the Global North and making them the familiar idiom for specifying urbanicity (Nair, Citation2013). South Asian scholars have begun to push against this trend, building rich accounts of the urban from the very worlds they study (Baviskar, Citation2019; Gururani & Dasgupta, Citation2018). Our specification of the urban as an ecological formation draws upon their arguments to call for other ways to grasp and understand urbanicity. This endeavor of starting from a city where the other-than-human is always in the field of vision addresses dimensions of the lived city that are of equal importance to analyzing the material politics of city-making as the familiar refrains of capital, the state, planning and design.

The cultivated, feral and the wild then are a set of relational diagnostics, derived from a city in the Global South, for an urban theory that must take shape. What this means, in terms of an established method of urban analysis, cannot be reified, but some avenues might be foregrounded. First, this approach invites analysis of a number of currents that cut through the urban, which structure and regulate life at a number of sites and scales, in order to make sense of their power dynamics and recursivity. Second, ecological formations draw attention to a whole arena of social life in defining the urban, including understanding economic activity, institutional and everyday practices, and cultures of social reproduction. Third, it calls for understanding a suite of urban actors that make and contest the urban, whether through improvisation, informality, innovation or by design. Fourth, tracking ecological formations requires a willingness to expand the methodological repertoire of conventional urban studies, where conversations between ethology and ethnography are crucial. There is much to be gained from such an endeavor, not least in terms of enriching a vibrant field of study that resonates across the social sciences.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge a European Research Council Horizon 2020 Starting Grant, entitled Urban Ecologies: governing nonhuman life in global cities, which made this work possible. Gunjesh Kumar, Uriv Gupta and Priyanka Justa conducted fieldwork with MB in Delhi, and offered many insights on the city's urban ecologies that have shaped this paper. AS sincerely thanks Philip Howell and the Department of Geography of the University of Cambridge, which hosted him as a Visiting Scholar and supported his work towards this article. That urban cattle are deemed waste, whilst living on waste, is Jonathon Turnbull's idea, for which the authors are grateful. Sue Ruddick generously invited the authors to be part of this special issue, and three anonymous reviewers as well as the editors of Urban Geography provided helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2002). Cities: Reimagining the urban. Polity Press.

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2017). Seeing like a city. Polity Press.

- Anand, U. (2012, March 15). Conceding defeat to monkeys, MCD says can't catch them. Indian Express.

- Anon. (1951). Cattle Nuisance in Delhi. [Local Government/Chief Commissioner/File No. 11(36)]. Delhi State Archives.

- Anon. (1977, November 15). Desai against export of animals. The Statesman, p. 2.

- Anon. (1978). India bans export of rhesus monkeys. International Primate Protection League Newsletter, 5(1), 2–4.

- Anon. (2007). Monkeys attack Delhi politician. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/7055625.stm

- Anon. (2010, September 9). We don't have enough monkey catchers: MCD. Hindustan Times.

- Anon. (2015). Over 64k dog bite cases in Delhi, north Delhi most affected. Retrieved December 16, 2015, from http://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/over-64k-dog-bite-cases-in-delhi-north-delhi-most-affected/story-2kgHhZBAYWwpqmyGS5vz6O.html

- Anon. (2016). Stray efforts can't solve this problem. Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/27-804-stray-dogs-caught-by-ndmc-in-north-delhi-in-2018-19-119070301487_1.html

- Anon. (2019a). 27,804 stray dogs caught by NDMC in north Delhi in 2018-19. Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/27-804-stray-dogs-caught-by-ndmc-in-north-delhi-in-2018-19-119070301487_1.html

- Anon. (2019b). SDMC shifting responsibility to trap, translocate monkeys, Delhi govt tells HC. Retrieved January 29, 2019, from https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/sdmc-shifting-responsibility-to-trap-translocate-monkeys-delhi-govt-tells-hc/1467862

- Barua, M. (2018a). Animating capital: Work, commodities, circulation. Progress in Human Geography, 43(4), 650–669.

- Barua, M. (2018b). Animal work: Metabolic, ecological, affective. Cultural Anthropology website. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1504-animal-work-metabolic-ecological-affective

- Barua, M. (2021). Infrastructure and non-human life: A wider ontology. Progress in Human Geography, 45(6), 1467–1489.

- Barua, M., Jadhav, S., Kumar, G., Gupta, U., Justa, P., & Sinha, A. (2021). Mental health ecologies and urban wellbeing. Health & Place, 69, 102577.

- Barua, M., & Sinha, A. (2017). Animating the urban: An ethological and geographical conversation. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(8), 1160–1180.

- Baviskar, A. (2011). Cows, cars and cycle-rickshaws: Bourgeois environmentalists and the battle for Delhi's streets. In A. Baviskar & R. Ray (Eds.), Elite and everyman: The cultural politics of the Indian middle classes (pp. 391–419). Routledge.

- Baviskar, A. (2019). Uncivil city: Ecology, equity and the commons in Delhi. Sage Publications Pvt. Limited.

- Belcourt, B.-R. (2016). A poltergeist manifesto. Feral Feminisms, 6(Fall), 22–32.

- Bhattacharjee, D., Sarkar, R., Sau, S., & Bhadra, A. (2019). A tale of two species: How humans shape dog behaviour in urban habitats. arXiv:1904.07113, 106–119.

- Bhattacharjee, D., Sau, S., Das, J., & Bhadra, A. (2017). Free-ranging dogs prefer petting over food in repeated interactions with unfamiliar humans. Journal of Experimental Biology, 220(24), 4654–4660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180643

- Biermann, C., & Mansfield, B. (2014). Biodiversity, purity, and death: Conservation biology as biopolitics. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(2), 257–273.

- Blecha, J., & Leitner, H. (2014). Reimagining the food system, the economy, and urban life: New urban chicken-keepers in US cities. Urban Geography, 35(1), 86–108.

- Brenner, N., & Schmid, C. (2015). Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City, 19(2-3), 151–182.

- Buller, H. (2014). Reconfiguring wild spaces: The porous boundaries of wild animal geographies. In G. Marvin & S. McHugh (Eds.), Routledge handbook of human-animal studies (pp. 233–245). Routledge.

- Choy, T. (2011). Ecologies of comparison: An ethnography of endangerment in Hong Kong. Duke University Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1986). Nomadology: The war machine (B. Massumi, Trans.). Semiotext(e).

- Delhi Development Authority. (1962). Master plan for Delhi. Delhi Development Authority.

- Deshpande, A., Gupta, S., & Sinha, A. (2018). Intentional and multimodal communication between wild bonnet macaques and humans. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 5147.

- Doron, A. (2020). Stench and sensibilities: On living with waste, animals and microbes in India. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 32(S1), 23–41.

- Federici, S. (2004). Caliban and the witch: Women, the body, and primitive accumulation. Autonomedia.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Hüttler, W. (1998). Society's metabolism. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2(4), 107–136.

- Francis, R. A., & Chadwick, M. A. (2012). What makes a species synurbic? Applied Geography, 32(2), 514–521.

- Gabrys, J. (2012). Becoming urban: Sitework from a moss-eye view. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(12), 2922–2939.

- Gandy, M. (2006). Urban nature and the ecological imaginary. In N. Heynen, M. Kaika, & E. Swyngedouw (Eds.), In the nature of cities: Urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism (pp. 63–74). Routledge.

- Gandy, M. (2013a). Marginalia: Aesthetics, ecology, and urban wastelands. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(6), 1301–1316.

- Gandy, M. (2013b). Entropy by design: Gilles clément, parc henri matisse and the limits to avant-garde urbanism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(1), 259–278.

- Gandy, M. (2015). From urban ecology to ecological urbanism: An ambiguous trajectory. Area, 47(2), 150–154.

- Gandy, M. (2016). Unintentional landscapes. Landscape Research, 41(4), 433–440.

- Gandy, M. (2021). Urban political ecology: A critical reconfiguration. Progress in Human Geography, 46(1), 21–43.

- Ghertner, D. A. (2015). Rule by aesthetics: World-class city making in Delhi. Oxford University Press.

- Gidwani, V. (2015). The work of waste: Inside India's infra-economy. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(4), 575–595.

- Gidwani, V., & Reddy, R. N. (2011). The afterlives of “waste”: Notes from India for a minor history of capitalist surplus. Antipode, 43(5), 1625–1658.

- Ginn, F. (2016). Domestic wild: Memory, nature and gardening in suburbia. Routledge.

- Government of India. (2019). 20th Indian Livestock Census - 2019: All India Report. Retrieved from New Delhi.

- Gururani, S., & Dasgupta, R. (2018). Frontier urbanism: Urbanisation beyond cities in South Asia. Economic & Political Weekly, 43(12), 41–45.

- Gutgutia, S. (2020, November 30). Pigs, precarity and infrastructure. Ecologizing Infrastructure: Infrastructural Ecologies. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/pigs-precarity-and-infrastructure

- Heynen, N., Kaika, M., & Swyngedouw, E. (Eds.). (2006). The nature of cities: Urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism. Routledge.

- Hinchliffe, S., Kearnes, M. B., Degen, M., & Whatmore, S. (2005). Urban wild things: A cosmopolitical experiment. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 23(5), 643–658.

- Hinchliffe, S., & Whatmore, S. (2006). Living cities: Towards a politics of conviviality. Science as Culture, 15(2), 123–138.

- Howell, P. (2000). Flush and the banditti: Dog-stealing in Victorian London. In C. Philo & C. Wilbert (Eds.), Animal spaces, beastly places: New geographies of human-animal relations (pp. 37–58). Routledge.

- Howell, P. (2015). At home and astray: The domestic dog in Victorian Britain. University of Virginia Press.

- Jasper, S. (2018). Sonic refugia: Nature, noise abatement and landscape design in West Berlin. The Journal of Architecture, 23(6), 936–960.

- Katz, C. (2001). Vagabond capitalism and the necessity of social reproduction. Antipode, 33(4), 709–728.

- Kumar, S. (2007). New friends colony residents vs Union of India (UOI) and Ors. on 14 March, 2007. W.P.(C) No. 2600/2001. Delhi High Court.

- Majumder, S. S., Bhadra, A., Ghosh, A., Mitra, S., Bhattacharjee, D., Chatterjee, J., Nandi, A. K., & Bhadra, A. (2014). To be or not to be social: Foraging associations of free-ranging dogs in an urban ecosystem. Acta Ethologica, 17(1), 1–8.

- Majumder, S. S., Paul, M., Sau, S., & Bhadra, A. (2016). Denning habits of free-ranging dogs reveal preference for human proximity. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 32014.

- Malik, I. (1989). Population growth and stabilizing Age structure of the tughlaqabad rhesus. Primates, 30(1), 117–120.

- Metzger, J. (2014). The moose are protesting: The more-than-human politics of transport infrastructure development. In J. Metzger, P. Allmendinger, & S. Oosterlynck (Eds.), Planning against the political (pp. 203–226). Routledge.

- Mohnot, S. M. (1978, December). On the primate resources of India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 75, 961–970.

- Montford, K. S., & Taylor, C. (2016). Feral theory: Introduction. Feral Feminisms, 6(Fall), 5–17.

- Moore, J. W. (2017). The capitalocene, part I: On the nature and origins of our ecological crisis. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(3), 594–630.

- Nadal, D. (2019). To kill or not to kill? Negotiating life, death, and one health in the context of dog-mediated rabies control in colonial and independent India. In C. Lynteris (Ed.), Framiing animals as epidemic villains: Histories of non-human disease vectors (pp. 91–118). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nadal, D. (2020). Rabies in the streets: Interspecies camaraderie in urban India. The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Nagy, K. (2020). Plastics saturate us, inside out. Feral Atlas. https://feralatlas.supdigital.org/poster/plastics-saturate-us-inside-and-outside-our-bodies

- Nair, J. (2013). Is there an ‘Indian’ urbanism? In A. M. Rademacher & K. Sivaramakrishnan (Eds.), Ecologies of urbanism in India: Metropolitan civility and sustainability (pp. 43–70). Hong Kong University Press.

- Narayanan, Y. (2017). Street dogs at the intersection of colonialism and informality:‘subaltern animism’as a posthuman critique of Indian cities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(3), 475–494.

- Nath, D. (2014, May 11). Over a thousand illegal dairies in Delhi. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/over-a-thousand-illegal-dairies-in-delhi/article5997887.ece

- Nietzsche, F. (1982). Twilight of the idols (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). Viking Penguin Inc.

- Palmer, C. (2003). Colonization, urbanization, and animals. Philosophy & Geography, 6(1), 47–58.

- Parks, L. (2017). Mediating animal-infrastructure relations. In M.-P. Boucher, S. Helmreich, L. W. Kinney, S. Tibbits, R. Uchill, & E. Ziporyn (Eds.), Being material (pp. 144–153). MIT Press.

- Philo, C. (1995). Animals, geography, and the city: Notes on inclusions and exclusions. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 13(6), 655–681.

- Ragavan, S. (2021). Between field and home: Notes from the balcony. Cultural Geographies, 28(4), 675–679.

- Ragavan, S., & Srivastava, S. (2020). Commoning infrastructure. Ecologizing infrastructure: Infrastructural ecologies. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/commoning-infrastructures

- Ruddick, S. M. (2017). Rethinking the subject, reimagining worlds. Dialogues in Human Geography, 7(2), 119–139.

- Sandilands, C. (2017). Some ‘F’ words for the environmental humanities: Feralities, feminisms, futurities. In U. Heise, J. Christiensen, & M. Niemann (Eds.), The Routledge companion to environmental humanities (pp. 443–451). Routledge.

- Sharan, A. (2006). In the city, out of place: Environment and modernity, Delhi 1860s to 1960s. Economic & Political Weekly, 41(47), 4905–4911.

- Sharan, A. (2014). In the city, out of place: Nuisance, pollution, and dwelling in Delhi, C. 1850-2000. Oxford University Press.

- Simone, A. M. (2004). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429.

- Simone, A. M. (2019). Improvised lives. Polity Press.

- Simone, A. M., & Pieterse, E. (2017). New urban worlds: Inhabiting dissonant times. Polity Press.

- Singh, A. D. (2000). Common Cause (Redg Society) vs Union of India (UoI). W.P.(C) No. 3791/2000. Delhi High Court.

- Sinha, A. (1995). Whose life is it anyway? A review of some ideas on the issue of animal rights. Current Science, 69(4), 296–301.

- Sinha, A. (2005). Not in their genes: Phenotypic flexibility, behavioural traditions and cultural evolution in wild bonnet macaques. Journal of Biosciences, 30(1), 51–64.

- Sinha, A., & Vijayakrishnan, S. (2017). Primates in urban settings. In A. Fuentes (Ed.), International encyclopaedia of primatology. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119179313.wbprim0458

- Smith, N. (1996). The production of nature. In G. Robertson, M. Mash, L. Tickner, J. Bird, B. Curtis, & T. Putnam (Eds.), Futurenatural: Nature, science, culture (pp. 35–54). Routledge.

- Southwick, C. H., Beg, M. A., & Siddiqi, M. R. (1961). A population survey of Rhesus Monkeys in northern India: II. Transportation routes and forest areas. Ecology, 42(4), 698–710.

- Southwick, C. H., & Siddiqi, M. F. (1994). Primate commensalism: The rhesus monkey in India. Review of Ecology, 49(3), 223–231.

- Southwick, C. H., & Siddiqi, M. R. (1968). Population trends of Rhesus Monkeys in villages and towns of northern India, 1959-65. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 37(1), 199–204.

- Srinivasan, K., Kurz, T., Kuttuva, P., & Pearson, C. (2019). Reorienting rabies research and practice: Lessons from India. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 1–11.

- Sundaram, R. (2010). Pirate modernity: Delhi's media urbanism. Routledge.

- Wadiwel, D. J., & Taylor, C. (2016). A conversation on the feral. Feral Feminisms, 6(Fall), 82–94.

- Webber, A. D. (2017). Commensalism. In A. Fuentes (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of primatology (Vol. I, pp. 211–212). Wiley Blackwell.

- Whatmore, S. (2002). Hybrid geographies: Natures, cultures, spaces. Sage.

- Whatmore, S., Degen, M., Hinchliffe, S., & Kearnes, M. (2003). Vernacular ecologies in/for a convivial city: Lessons from Bristol. Paper presented at the Urban and Regional Development of the ISA (RC21), Milan.

- Whatmore, S., & Hinchliffe, S. (2012). Ecological landscapes. In D. Hicks & M. C. Beaudry (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of material culture studies (pp. 440–458). Oxford University Press.

- Wolch, J. (1996). Zoöpolis. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 7(2), 21–47.

- Wolch, J., Emel, J., & Wilbert, C. (2003). Reanimating cultural geography. In K. Anderson (Ed.), Handbook of cultural geography (pp. 184–206). Sage.

- Wolch, J., West, K., & Gaines, T. E. (1995). Transspecies urban theory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 13(6), 735–760.