ABSTRACT

Despite the rise of social media as a major factor in protests since the early 2010s, scholars have documented the continued importance of urban space and “place-based networks” for social movements. However, the 2019–2020 Hong Kong Anti-ELAB protests saw a shift from occupying symbolic public space to a more variegated use of urban spaces in the city. Combining network analysis of Telegram channels and georeferencing of protest events, this study shows how new digital media platforms such as Telegram enabled a diverse array of protest activities, as well as a shift from formal centrally located civic spaces to a wider range of everyday spaces including malls, offices, and industrial buildings. This study also asks why this occurred, situating the shifting geography of protests as a response to several factors: new social media technologies, strengthening of state surveillance of physical and digital space, and collective learning from the perceived failures of past movements. The implications of these shifts for the future of urban social movements and the “public sphere” are discussed.

Introduction

As I prepared to land at Hong Kong’s International Airport on 13 August 2019, I realized I would be flying directly into the ongoing Hong Kong protests. The protest had begun a few months earlier in response to the Hong Kong government’s proposed law to permit extradition of criminal subjects to mainland China, but had quickly snowballed into a general revolt against the government and its failure to deliver on earlier promises of universal suffrage. Upon landing, the departure board at the airport showed my next flight canceled. Entering the arrival hall, I was greeted by the sounds of protest chants and crowds of young people handing out fliers to arriving passengers.

The airport protest had not been planned long in advance. Using a variety of online chatrooms and message boards, protesters called for an occupation of the airport in order to pressure the government after several months of protest. Shutting down one of the world’s busiest airports cost the economy and put pressure on the authorities. Images of mostly young people bringing the airport to a standstill brought a global spotlight on the events in Hong Kong.

Within a few hours, police entered the airport and dispersed the occupation. But this would not end the movement. That was precisely the logic of the movement’s oft-referenced Bruce Lee mantra “be water”: to continuously adapt and regroup. By avoiding a commitment to a particular space, the movement sought to maintain momentum and avoid police crackdowns. In a city where freedom of assembly remained formally legal, activists applied for permits for the large street marches and rallies in the city’s Central district. But as protests deepened, the police grew hesitant to approve events. Protests shifted away from symbolic public spaces in the city center to peripheral spaces such as malls, MTR stations, schools, parks in distant neighborhoods.

Research questions

This study examines the relationship of digital media tools to the spatiality of protest movements, using the case of the Hong Kong 2019–2020 Anti-ELAB protests. Having found myself in the middle of the airport protest, I began to wonder if these protests were departing from the spatial and organizational logics seen in previous social movements. While recent scholarship on social movements has examined the importance of digital platforms such as Twitter and Facebook (Castells, Citation2012; Juris, Citation2005; Tufekci, Citation2018), physical urban space remains as vital as ever to social movements. This was true in the Arab Spring and Occupy protests, which first saw the widespread use of online social media, and remains true of recent protests in Hong Kong, Thailand, Myanmar, and in the United States. Yet, the Hong Kong protests of 2019–2020 warrant a reexamination of protest logics in light of the use of new communications tools and new protest formats that crystallized in Hong Kong during the summer of 2019. Extended occupation of symbolic public spaces transformed into a more spontaneous and dynamic format utilizing an array of spaces across the city. Social media remained important but was also changing: Twitter and Facebook were still used but were no longer the only platforms – new Reddit-like message boards and the encrypted messenger app Telegram now played equally if not more important roles, alongside more ad-hoc specially built interfaces, such as a local mapping application HKMap.Live.

This study attempts to account for these changes, focusing on the interplay between changing technological platforms and the use of physical urban space in social movements. (1) First, this study documents through textual and geospatial analysis, the spatial dispersion of protest sites and diversification of protest formats. (2) This study also asks how new social media platforms may have contributed toward a more spatially heterogenous and tactically diverse repertoire of urban protest. As recent studies of social movements have shown, local social networks and “place-based social capital” remain crucial even as digital tools have enabled more rapid diffusion of protest tactics and messages (Rovisco & Ong, Citation2016; Tufekci, Citation2018). Yet, the ways in which protesters use space could be influenced by new digital platforms that differ in crucial ways from open platforms of Facebook and Twitter, particularly in the ways they allow creation of new hyperlocal networks to manage neighborhood events and integrate them with the wider movement. However, it would be too simplistic to attribute changing spatiality of protests to technology alone. Avoiding such technological determinism, this study also asks (3) how evolving protest repertoires can be contextualized amidst systemic or external trends, chiefly the increase in state surveillance of both digital and physical space.

As I spoke with those involved in the protests, I repeatedly heard a preference for anonymity and discreetness. Many feared exposing their political sympathies within existing social networks, such as church groups (Interview with “April”, January 2020 in Hong Kong). While social media platforms are increasingly seen as a cause of political polarization harmful to democratic traditions (Conover et al., Citation2011), this study asks (4) how certain digital tools might strengthen neighborhood-based social capital? This is an important question not only for Hong Kong, but also globally, given the observed decline of traditional forms of social capital (Putnam, Citation2000) and global rise in authoritarianism.

Literature review

In order to understand how evolving digital tools relate to the spatiality of protest, it’s useful to consider how scholars have conceptualized the relationship between a social movement’s use of physical space and their deployment of digital tools. The function of digital tools has often been understood in relation to a social movement’s dual needs of building trust and sustaining momentum among a core of activists, often in a particular place, while simultaneously building bridges to related struggles or allies, often in distant locations.

Social networks and urban space

Scholars of social movements have long documented the importance of place in catalyzing collective action. In The City and the Grassroots, Castells (Citation1983) showed through city-specific cases how neighborhood identities and community dynamics shaped various social movements, broadening Marxist theories of social movements that emphasized the purportedly determinative role of class structure. The importance of “strong ties” resulting from neighborhood personal networks has been a key factor in protests from the Paris Commune (Gould, Citation1993) to more contemporary struggles (Miller & Nicholls, Citation2013; Nicholls, Citation2009; Nicholls et al., Citation2013). At the same time, research on contemporary social movements has shown the important role of digital technologies and global networks in facilitating protests (Bonilla & Rosa, Citation2015; Castells, Citation2012; Tufekci, Citation2018; van Haperen et al., Citation2018). Yet, despite Castell’s early description of digital networks as providing a “space of autonomy” (Citation2012) for protesters to evade control of authorities, the continued importance of physical urban space for social movements suggests that digital technologies have not diminished the value of physical urban space for protesters, nor do they operate autonomously (Juris, Citation2012; Rovisco & Ong, Citation2016).

Yet, even as scholars acknowledge the interplay of urban space with digital technologies, there is still a tendency to treat “local networks” as existing separately or a priori from the “global networks” facilitated by digital platforms. While studies of digital tools have emphasized the ability of such tools to “bridge” between activists in different places, or in enabling movements to “scale shift” (Tarrow & McAdam, Citation2005) from local to global, this study of Hong Kong’s Telegram ecosystem shows how digital tools were employed at the “hyperlocal” scale to coordinate activities within urban neighborhoods and deepen local organizing capacity.

Scholars have long argued that place-based social networks are crucial for social movements. Gould (Citation1993, p. 748) showed how in the Paris Commune of 1871 “insurgent mobilization depended on neighborhood rather than trade solidarity.” Even with the rise of digital tools, geographically proximate activists remain crucial to contemporary movements, as studies have documented in the Spanish 15 M movement, (Borge-Holthoefer et al., Citation2011), Black Lives Matter protests in the United States (Haffner, Citation2019), and immigrant rights struggles (Nicholls & Uitermark, Citation2016). Nicholls (Citation2009, p. 84) argued that places enable the development of “stored social capital in existing relational networks,” which can foster trust and common norms among activists. Van Haperen et al. (Citation2018, p. 410) have argued that “people tend to sustain interaction more readily with others who are like them and geographically nearby.” Sampson et al. (Citation1997) point to social cohesion and trust in facilitating “collective efficacy,” the willingness of citizens to intervene on behalf of the common good. Thus, “sense of place,” or the ways in which place fosters common identity based on shared experiences, interests, and values (Martin, Citation2003; Tuan, Citation1977), is crucial to most urban social movements. It is not merely physical proximity per se, but the emotional bonds forged through shared experience, that provide critical support for social movements.

Place-based solidarities, however, can also hinder a movement’s expansion (Harvey, Citation2001; Nicholls, Citation2009). Therefore, movements often form alliances with other groups, either proximate or distant. The early 2010s Occupy and Arab Spring protests were among the first instances of globally networked protests enabled partially by newly emergent forms of social media (Castells, Citation2012; Tufekci, Citation2018). Digital networks like Facebook or Twitter are thought to facilitate “weak ties” (Granovetter, Citation1977), or what Tufekci (Citation2018, p. 21) described as “bridges between disparate groups.” Twitter and Facebook have obvious affordances for rapid broadcasting and sharing of protest messages and images, as well as sharing tactics. Some have termed this “nonrelational diffusion” (Rane & Salem, Citation2012; Soule, Citation1997; Soule & Roggeband, Citation2018) to distinguish from “close ties” and “interpersonal networks” that are thought to play a role in sparking or catalyzing protests within particular places.

Such diffusion may allow movements to “scale shift,” moving struggles from local or national contexts to transnational levels, taking advantage of political opportunities elsewhere when local action may be prevented by authoritarian control or other obstacles (Sikkink, Citation2005; Tarrow & McAdam, Citation2005). However, such a “nested” scalar imaginary implies a separate “global scale” as existing above or beyond the “local.” In fact, global networks themselves are facilitated by processes occurring in specific places. Sassen (Citation1991) showed how certain “global cities” served as “command and control hubs” of the global financial system. Nicholls and Uitermark (Citation2016, p. 28) make a similar argument that certain cities function as protest hubs, where “well-connected activists … broker relations between local allies and geographically distant comrades,” facilitating diffusion of tactics, strategies, and ideas across space.

The literature on place and protests highlighted above suggests that protests often begin from a core nucleus of geographically proximate actors who have preexisting relations (Diani & McAdam, Citation2003) or strong ties, then diffuse through open digital networks to other distant clusters. However, in 2019, social messaging platforms like Telegram also helped catalyze new hyperlocal place-based ties, a process of micro-diffusion within Hong Kong, rather than simply outward diffusion to distant locations. This was enabled by the platform’s “Channel” feature, which allowed the rapid ad-hoc creation of breakout channels in specific neighborhoods (Urman et al., Citation2021) following broader citywide calls for collective action. The temporal progression of the 2019 Anti-ELAB movement complicates the dichotomy between locally based social networks and distant digital networks. As the movement progressed, new digital tools helped drive deeper neighborhood engagement.

The state strikes back: technology and social movements

The “square occupations” that characterized the protests of the “early social-media era” caught many governments off-guard. Recently, however, states have learned how to respond to such protests with a range of tactics including more sophisticated censorship but also more subtle tactics of strategic patience and misinformation. As Tufecki observed, “Governments have learned how to respond to digitally equipped challengers and social movements, and have even adopted portions of their repertoire” (Tufekci, Citation2018, p. 225). The digital sphere is no longer, if it ever was, the “autonomous space” that Castells (Citation2012, p. 250) described. States, long obsessed with maintaining visibility of its cities and citizens (Foucault, Citation2012; Scott, Citation1998), have developed new methods for surveillance including mobile phone tracking, CCTV cameras and facial recognition, and big data analysis. China is a leading developer of these technologies and actively exports them to other governments (Andersen, Citation2020; Greitens, Citation2020; Mozur et al., Citation2019).

The changing spatiality of protest alongside emergent social media platforms can be seen as a “counter response” to increasingly sophisticated state strategies of repression and surveillance. Whereas the early 2010s saw the rise of open platforms like Facebook and Twitter, encrypted messaging platforms such as Telegram have become increasingly important (Vir & Hall, Citation2018). Telegram offers key affordances (Gibson, Citation1977; Hutchby, Citation2001) for countering increased state repression. For instance, anonymous posting enables quick formation of breakout threads and channels, which allows for formation of smaller groups to coordinate specific activities while allowing users to remain anonymous (Liu & Wong, Citation2019; Urman & Katz, Citation2020). While Hong Kong police did surveil Telegram protest groups (Schectman, Citation2019), this did not appear to hinder Telegram’s overall utility for the movement, at least until the June 2020 National Security Law. However, Telegram may be less ideal than open platforms for wider dissemination of messages beyond the activist core or to distant locations.

From the early days of the Internet, scholars have been trying to understand the impact of information and communications technologies (ICTs) on urban space (Castells, Citation1992; Graham & Marvin, Citation1995; Mitchell, Citation1996; Townsend, Citation2000). The proliferation of smart phones has brought about Townsend’s prophecy of a “real time city” (Townsend, Citation2000), and what Picon (Citation2015) describes as a “sentient urban space” resulting from the blanketing of cities with cameras, cell phones, and other technologies. Hatuka and Toch (Citation2016, p. 2193) describe how “on the one hand [technology] turns public spaces into venues surveyed and controlled by authorities; on the other they enhance the flexible use of personal devices by individuals.” This paradox is particularly relevant for understanding how social movements adapt to increasingly surveilled urban spaces and online networks. The coevolution of place-based and digitally driven protest activities is addressed more specifically below in relation to the Hong Kong protest movement.

Hong Kong: evolving repertoires in a “city of protest”

Shifts in Hong Kong protest tactics from the 2015 Umbrella Movement to 2019 show how movements respond to changing conditions such as increased state repression. The recent history of Hong Kong’s social movements suggests technology’s role in social movements is not determinative, but is embedded in evolving “repertoires of collective action” (Tilly, Citation1978; Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015). These repertoires incorporate tactics of earlier movements (such as Umbrella) yet also evolve as activists learn from successes and failures of previous protests and employ new tactics and tools in response to the evolving tools and strategies of states.

The 2015 Umbrella Movement, like the Arab Spring and Occupy movements, has been characterized as a decentralized “networked protest” (Liu & Wong, Citation2019) that utilized platforms like Facebook (Lee et al., Citation2015; Lee & Chan, Citation2016) but also involved a lengthy occupation of Central Hong Kong. Youth activists, led by Joshua Wong’s Scholarism Group, had first occupied a fenced-in plaza in front of the Admiralty Government Headquarters during the 2012 protest against a proposed patriotic education law. In 2014, Scholarism again occupied the space, hastening professor and lawyer Benny Tai to call citizens to “Occupy Central with love and peace,” to oppose a proposal for suffrage that would require pre-vetting of candidates by Beijing (Dapiran, Citation2017, p. 73).

Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement was symbolized by the encampment in the heart of Hong Kong Island. The camp generated an outpouring of artwork, texts (Veg, Citation2016), and slogans. The protesters’ respectfulness and cleanliness was widely documented by media (Barber, Citation2014; E. W. Cheng, Citation2019, p. 65). The main encampment was at Harcourt Road (nicknamed “Umbrella Square”) in Admiralty near the government offices, although more confrontational protesters in the neighborhood of Mong Kok, formed an alternative protest camp in the city (Yuen, Citation2018, p. 397). Disagreement among activists as to the use of more violent or radical tactics manifested in these diverging protest sites and would resurface again in 2019.

After three months, authorities cleared the Umbrella site as citizens tired of the disruption to daily life and the movement struggled to maintain momentum. According to Tufekci (Citation2018, p. 234),

Occupy Central had suffered from the strengths and weaknesses of other digitally fueled movements. It was able to scale up quickly and control its own narrative. However, it was unable to effectively respond to the government’s countermeasures and advance the momentum of the movement.

This failure was interrogated as the 2019 protests began, leading to a different strategy characterized by the mantra of “be water.” Protesters called for constant adaptation and flexibility in order to avoid government and police action and also maintain momentum (Holbig, Citation2020; Lam et al., Citation2019).

The first protests of 2019 were organized, as in other movements, by a core of activists and organizations with preexisting ties dating at least to the 2015 Umbrella Movement, such as Joshua Wong’s Demosisto party, Hong Kong Federation of Students, and more “traditional” pan-Democratic parties in Hong Kong such as the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF).Footnote1 Social media helped diffuse images of Hong Kong’s protests globally, as well as within the city. While the initial mass marches through Central Hong Kong in June 2019 resembled the occupation of the 2015 Umbrella Movement, the ensuing months saw the evolution of more spatially and tactically variegated repertoires of collective action, which spread the movement throughout city neighborhoods.

While social movement scholarship emphasizes the importance of in-place, strong-tie networks to protests, the 2019 Anti-ELAB protests saw a proliferation of place-based groups that largely did not originate from preexisting ties or existing civic organizations. In some respects, this fits with earlier scholarship documenting a decline of traditional parties and political institutions across much of the “developed world” (Bennett, Citation1998; Putnam, Citation2000). Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2013) described a shift from “collective” to “connective” action, while Pasotti (Citation2020) highlighted a rise of “experiential tools” such as festivals and events, which are supposedly part of this turn towards “personal action frames” (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2013, p. 743). The array of creative art and memes shared on Telegram can be seen as more “personalized” forms of political expression.

Despite these similarities, it would be simplistic to treat the protest logics in Hong Kong as resulting entirely from the same trends observed in Democratic countries. For one, Hong Kong has recently seen a growing “collective” Hong Kong identity, even if not primarily driven by specific political institutions (Chow et al., Citation2020; Veg, Citation2017). New political parties did form after the 2015 Umbrella Movement, but the government curtailed their ability to organize or hold power. Protesters in 2019 went to greater efforts to conceal their identities for fear of being exposed by new surveillance systems (Mozur, Citation2019). New digital tools would ideally circumvent some of these state efforts, but emerging digital tools did not entirely obviate the role of organized groups like the CHRF, labor and student federations, all of which developed sizeable followings of their own on Telegram.

Amidst strengthening state surveillance, social messaging platforms helped catalyze new ad-hoc place-based weak ties. This aligns with recent scholarship showing the continued importance of place-based organizing alongside digital networks. Yet, the particular use of these tools complicates binaries between “place-based strong-tie networks” and “digitally-enabled geographically distant networks.” As argued in this paper, social messaging platforms like Telegram helped “micro-target” communication to specific neighborhoods and circumvent police approval required for protests in central locations. However, new technologies are not determinative of this shifting dynamic. Rather, protest repertoires in Hong Kong were co-produced through a dynamic interaction between protesters and civic organizations, the state, and technologies themselves. In Hong Kong, Telegram allowed protesters to partially circumvent state surveillance and adopt new tactics that deepened citizen participation in the protests, a form of collective learning from the perceived failures of the 2015 Umbrella Movement to engage a wider swath of Hong Kong.

Methods

The study of protest movements through analysis of digital and online texts has become a useful method to investigate protests that themselves employ digital platforms. Spatial analysis of protest activity has been undertaken in a variety of contexts (Bastos et al., Citation2014; Rodríguez-Amat & Brantner, Citation2016), often using geolocated digital activity to map protests. Analysis of online media has been used to study protest tactics in Hong Kong such as that of text and images in the Umbrella Movement by Veg (Citation2016), and analysis of postings in online groups (E. W. Cheng, Citation2019; Lee & Chan, Citation2016, Citation2018; Leung, Citation2016; Porta et al., Citation2015). A recent study also examined the structure of Telegram in the recent Hong Kong protests (Urman and Katz, Citation2021). However, there have been few attempts to explore the dynamic interplay between the use of online platforms and spatiality of events over different phases of a protest movement.

To investigate these issues, a mixed-method sampling approach was employed (Onwuegbuzie & Collins, Citation2007) involving textual analysis of online posters that advertised protest events, spatial georeferencing of the events advertised, and network analysis of Telegram channels. To assess the changing spatiality and format of protest events, photos from three of the main Telegram channelsFootnote2, which advertised events throughout the city from the first large rallies in June 2019 until January 2020, were downloaded. After downloading 22,058Footnote3 images, the location and date of 400 unique events were extracted and a database of these events was compiled. The events were categorized and coded (Saldaña, Citation2013) according to the types of spaces in which they occurred (plaza, park, mall, street, etc.) and the types of activities they entailed (large assembly, lunchtime march, pop-up market, etc.). A limitation of this approach is that it primarily captures events that are planned and advertised in advance on Telegram channels but excludes “spontaneous” events that occurred after planned events, such as skirmishes between protesters and police. However, this method is able to capture the bulk of organized events.

This study also examined the relationship between the spatiality of protest events and the structure of the communications platform. While Telegram can be used for peer-to-peer chatting, it also features channels that allow dissemination of information to an unlimited number of participants (Urman & Katz, Citation2021). Unlike Facebook or Twitter, channels are difficult to search for and are typically found by being linked from other channels. Protesters also used other digital platforms such as Reddit and a local forum LIHKG.com, as well utilizing AirDrop to quickly and securely transmit data in real time among protesters in the same place. However, the rapid proliferation of numerous specialized Telegram channels with specific functions beginning in June 2019 eventually formed an ecosystem with unique affordances that influenced the spatiality and tactics of the movement.

A partial network map of relationships between channels was created using snowball sampling. Starting with the three largest “aggregator” channels, chat histories for the eight-month period of the most intense protest activity (June 2019–January 2020) were downloaded. These chat histories were scraped for mentions of other channels. This same procedure was followed for channels mentioned by the original three “source” channels, particularly channels advertising events, as compared to, for example, those reporting news, sharing resources, or reconnaissance of police movements (see Appendix). The “network” package in R was used to analyze 580 edge pairs (relationships) among 357 nodes (individual channels). The resultant network graph represents the edges as lines and the nodes (channels) as circles, which are sized proportionally to degree centrality, the number of links a given channel has to other channels.

Findings

The data on protest activities and location, collected from a period of June 2019 to January 2020, show how the protest evolved over this period. This evolution comprised: (a) continuous adaptation over time, with a push of activities into new formats and peripheral neighborhoods of Hong Kong; (b) a diversity of Telegram channels catering to specific types of protest and specific neighborhoods; and (c) Use of new spaces that afford quick entry-egress and that allow residents to participate as part of their daily routines.

Diversification of protest

While protests against the proposed extradition bill began in March 2019, the movement was fully galvanized by the rally of over one million people on June 9, followed by another rally of similar size on June 16. These large rallies continued through summer. Many of the large rallies were organized by CHRF and obtained the required police “letters of no objection.” Such events often began at Victoria Park, site of the annual vigil for Tiananmen Square victims held in Hong Kong since 1989. Crowds then snaked their way through the skyscraper canyons of Hong Kong Island through Wan Chai to the Government Center and Legislative Council in Admiralty. Other protests were held at Edinburgh Place or Chater Garden, part of a large plaza in the heart of the city fronted by the British-built Old Supreme Court, now the Court of Final Appeal.

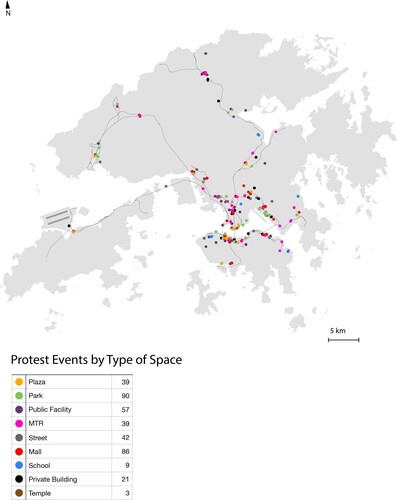

Over time, the movement developed new types of protest. Large-scale rallies in these symbolic central locations in the city did not end entirely, but they were supplemented by an increasingly diverse range of protest typologies held in more locations throughout the city (see ). From the start of protests, there was an attempt to avoid infighting between “peaceful rational nonviolent” protesters (called holifei) in Cantonese, and the “valiant” protesters (yungmoh), who confronted police directly often in the evening following the conclusion of planned events. One protester commented to me that, “You can choose a character, and I think by August or September many people have decided who they are” (personal communication, “HK Tomorrow,” April 2020). The protests were often described as “leaderless,” and while this may be an overgeneralization, the use of voting to decide location and course of protest events did entail a crowdsourced decision making process behind the choice of where many protest events would occur (Vincent, Citation2019).

Figure 1. (a) This map of the entirety of Hong Kong SAR shows the dispersion of events in different spaces across the territory. (b) This inset map of central Hong Kong shows the type of space events were held in as well as frequency. Hong Kong Island remains a frequent site of events but there are clusters of events in Mong Kok, Sha Tin, Kwun Tong, and elsewhere.

Violent confrontations early on galvanized the movement, but government response and protesters’ deliberations eventually led to growth of new protest types that were less confrontational. A protest at Sha Tin’s New Town Shopping Mall on July 14 evolved into a violent clash with more hardcore activists later on. An attack by alleged Triad members on protesters at the Yuen Long Subway Station on July 21 further enraged citizens and deepened mistrust of police, who were widely seen to be complicit in the attack. Escalation following these events led to a crescendo of pitched street battles throughout the summer, culminating in the occupation of Hong Kong Airport on August 12 and 13, during which protesters were able to bring one of the world’s largest airports to a halt. The events brought news attention but also internal doubt as to whether the occupation had harmed the movement’s image.

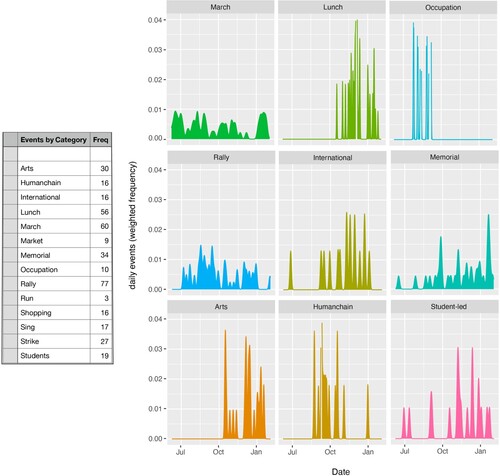

In October, a new call among protesters for “blossoming everywhere” or pien dei hoa fa sought to evade increasing government restrictions on large gatherings (Hale, Citation2019). Many new Telegram Channels organizing new forms of protest emerged during this time. Malls, streets, private buildings, and MTR (subway) stations became more common locations for events. In addition to a diversification of protest venues, there was also a rise of novel event types, particularly beginning in October including “lunch” protests, “arts related events”, while frequency of rallies and marches remained steady or even declined after October ().

Figure 2. Time series graphs show how the frequency of various forms of protest changed over the course of the protest from June 2019 until January 2020. More traditional formats such as marches, rallies, and occupation of government buildings are relatively constant or decline in frequency toward the latter half of the period, while new formats increase particularly in October such as art-themed events, lunchtime protests, memorials, and student-led protests.

Telegram networks

The structure of Telegram helped facilitate the proliferation of protest venues and activities. Users can subscribe to channels, which then post streams of news including photos or links to upcoming events. The difficulty of searching for channels means that they are typically shared by being mentioned or forwarded by other preexisting channels (Urman et al., Citation2021). As a protester described to me of his own involvement, “There would be groups formed with thousands of people inside them, and those would divide into smaller groups as well so they can launch channels and things like that. That’s how the Telegram culture in Hong Kong got started” (personal communication with “Benji,” April 2020). Telegram’s mobile-first interface allows for rapid creation of new channels and threads, facilitating sub-groups such as those formed in various neighborhoods.

An examination of the network structure of the Channels provides detail about how they functioned as an ecosystem for the movement. While some estimated there were 1800 Telegram channels linked to the protest movement (Urman et al., Citation2021), I selected only channels related to sharing of protest events and organizing activity. Despite being described as “leaderless,” the network structure nevertheless suggests a degree of centralization. Key channels, which I term “aggregators,” collected advertisements of daily events across the city from many smaller channels. Aggregator channels, some of which had around 160,000 followers at the peak of their activity, mostly started in June. Other channels, which were created over the following months, served a range of functions including dissemination of news, discussing tactics, monitoring police activity, and reporting planned events throughout the city. Many of them focused on specific neighborhoods, or specific protest types ().

Figure 3. This network graph shows the connections between Telegram channels, particularly those focused on advertising events. They are categorized according to their role as “aggregator” channels, neighborhood-specific channels, and protest-type specific channels. Size of circles corresponds to number of links to that channel (degree), while lines indicate a relationship (a link to a channel) between one channel and another.

Specialized network channels enabled more diverse and spatially heterogenous protest activities. Many channels focused on particular neighborhoods, allowing residents to find and participate in nearby events. Other channels advertised particular types of protests, such as the “human chains,” “lunch time protests,” or “shopping” events. They posted event plans, organized polls of users on desired courses of action, and shared information on police activity in neighborhoods. Some of their content was forwarded to larger audiences through the aggregator channels that have larger followings. For example, a channel that maintained the Lennon WallsFootnote4 throughout the city “Lennonovazed_channel,” had around 18,000 followers in February 2020 and linked to neighborhood Lennon Walls around the city, each of which had their own smaller channels. A protester involved with maintaining Lennon Walls described to me that

a lot of people would focus on helping maintain their neighborhood Lennon Walls, but occasionally a notice would go out across the city that a certain wall was ‘not quite as flourishing as we would like it to be’ and people from all over would come and help maintain it. (personal communication with “Benji”, April 2020)

These intermediate channels strengthened place-based social networks while simultaneously tying local events into the larger protest movement. The channels selected for network analysis were ones that organized events (see Appendix), but there was also a wide range of channels sharing news such as a “Citizens Press Conference” channel, legal resources for protesters, and many others.

Another type of channel performed reconnaissance of police. For example, the channels “HKMapLive” forwarded maps from a crowdsourced website in which users submitted the latest location and direction of police movements. These real-time crowdsourced information hubs were a critical part of the “be water” mentality, allowing adaptation in real time during the course of an event. In addition to the overall Hong Kong map, there were many neighborhood channels dedicated to reporting police activity in their specific neighborhoods, thus forming a citywide network of reconnaissance. For example, a channel “Southern Scout” tracked police in the southern part of Hong Kong Island.

Affordances of specific places

The data suggests that the protest movement created new locations and protest formats over time. But why did the protesters choose the locations they did? In the following section, I detail some of the more common locations for protests and the affordances (Gibson, Citation1977; Hutchby, Citation2001) they offered. In general, these new locations allowed for the routinization of protest into spaces of everyday urban life. They also permitted quick entry and exit and did not require lengthy occupation or police permits. Rather than confronting the state through occupation of symbolic spaces, these events enabled more casual participation and quick adaptation.

Plazas and parks

Many of the early marches in June began in Victoria Park and culminated at Tamar Park in front of the Legislative Council Building, including the July 1 protest that led to the occupation of the Legislative Council chambers itself. “Rallies were often held at Chater Garden, an urban park in the heart of Hong Kong's central business district adjacent to the colonial-era Court of Final Appeals building, or at nearby Edinburgh Place”. As the movement continued, many large events continued to be held in these “symbolic” public spaces due to their size, centrality, and imageability as public spaces. Many of the rallies and marches that were held here had broad themes and often targeted international audiences, for example, an 14 October 2019 “Hong Kong-Catalonia Solidarity Assembly”, or the 22 December 2019 “Human Rights Rally of Solidarity with Uyghurs.”

Parks and Plazas are often symbolic civic places connoting the “public sphere,” and have been common settings for urban protests in many cities (Davis & Raman, Citation2013; Hatuka, Citation2018). Victoria Park and Tamar Park both have local significance: Victoria Park as the location for the annual June 4 vigils of Tiananmen Square, and Tamar Park because of its adjacency to the Legislative Council and location of protests in the Umbrella Movement. However, in the case of Chater Garden/Edinburgh Square, the local connotations mattered less than the spatial qualities that make it an imageable “public space.” As with Cairo’s Tahrir Square or Istanbul’s Gezi Park, the images of protesters filling such spaces are easily transmitted to global audiences (AlSayyad, Citation2012; AlSayyad & Guvenc, Citation2015). Even as protests spread to new locations, such symbolic spaces continued to be the setting for events targeting international audiences.

Malls

The use of malls as protest sites in Hong Kong originates from “shopping protests” that emerged at the end of the Umbrella Movement as protesters used the innocuous act of shopping as cover for protests (Ng, Citation2014). On 14 July 2019, a major protest at Sha Tin New Town Plaza marked the first large-scale protest in a mall during this movement (Hui, Citation2019). New Town Plaza in Sha-Tin is one of the largest malls in Hong Kong and a community center for the middle-class residential new town of Sha Tin (Chu, Citation2018). In addition to Sha Tin, other malls frequently chosen for protests include Pacific Place in Admiralty and Taikoo Place in Eastern Hong Kong Island.

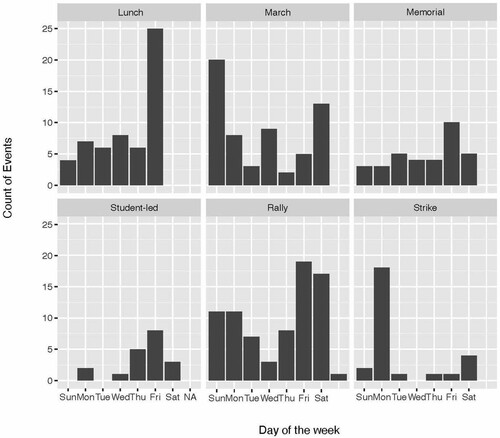

Malls offered several affordances for protests: easy accessibility for residents of the city, quick entry and egress due to their location adjacent to or above MTR stations, and in some cases a sense of safety from police due to the perceived political allegiances of the malls’ ownership.Footnote5 The city’s privately managed MTR corporation has long perfected the co-location of large retail and office complexes adjacent to or above its stations (Lin, Citation2002). Malls in Hong Kong often function as combined retail and civic spaces (Al et al., Citation2016; Chu, Citation2018). Many of Hong Kong’s largest malls, including Sha Tin’s New Town Plaza and Mong Kok’s Langham Place feature cavernous atriums, dramatic backdrops for thousands of protesters shouting protest chants. Furthermore, the co-location of commercial office buildings around malls made them ideal sites for the “lunch with you” protests that targeted office workers on their lunch break. Malls were ideal for weekday protests, whereas large rallies in Chater Garden or Edinburgh Place often occurred on weekends ().

Figure 4. This series of graphs shows the temporal rhythm of event types. Lunches are more likely on Fridays, while marches are held more often on Saturdays and Sundays, and rallies tend to be held on Fridays and Saturdays. Strikes tend to occur on Mondays. This suggests different event types accommodate people on different days of the week: for example, lunchtime protests are geared toward office workers.

Pop-up markets and the “yellow economy”

The rise of pop-up markets selling protest-related art and crafts emerged in response to the government’s order to ban officially sanctioned Chinese New Year markets from selling protest-related paraphernalia (Cheng, Citation2019). These events occurred mainly in January during the run-up to Chinese New Year, often in nondescript industrial buildings only accessible to those who discovered the location through social media, such as Telegram channels. Some of these events occurred in the former industrial district of Kwun Tong, where several adjacent buildings hosted pop-up markets on rooftops and small interior shops. Maps of the participating businesses were circulated on Telegram in advance, but some of the locations were deep inside industrial buildings – ideal for evading the police. These events in January were also the beginnings of the so-called “Yellow Economic Circle,” which saw an effort to channel consumer spending to businesses supportive of the protests. This became yet another “protest format” with its own channels and resources, including mobile apps showing all “yellow” businesses that were supportive of the movement.

MTR stations enabling “transit-oriented protests”

Hong Kong’s MTR system has long been considered one of the world’s most efficient subway systems. This efficiency was utilized by protesters: many events occurred inside or above MTR stations, and many posters wryly incorporate the visual language of the subway system to make their point. Additionally on August 23, a citywide “Hong Kong Way” human-chain event saw thousands of people link arms along the streets above three of the city’s main subway lines. The subway system proved to be the perfect infrastructure for the “flowering everywhere” ethos that the movement embraced. However, as the protests continued, MTR authorities went to greater lengths to ban protesters, for example, by closing stations in advance of planned movements. Protesters began using anonymous Octopus cards when they traveled to avoid having their location recorded when attending protests.

Several stations also became sites of memorialization after violent attacks on protesters. This was seen following a violent attack on protesters by supposed Triad gangs that occurred at the Yuen Long MTR Station on July 21 and by police at Prince Edward Station on August 31. As in the Umbrella Movement, memorialization of spaces was an important way for the movement to create new meaning by commemorating events that occurred in certain locations. After these incidents occurred, memorial events were held in these locations at the same day each month. These events sought to highlight police brutality and honor protesters.

Digital-physical nodes: Lennon Walls and message boards

Further evidence of such memorialization could also be seen in the creation of poster information walls. For example, in January 2020 I observed a pop-up information wall of posters in Sha-Tin’s New Town Plaza – the site of a major rally in July and many subsequent “shopping” events. This type of wall was a variation of the “Lennon Walls” of Post-It notes that emerged in the Umbrella Movement and that had flowered across the city again in 2019 and 2020 (Hou, Citation2020). However, as I slowed to observe, I recognized many of the posters from the Telegram channels I had been scrolling through in my phone. An elderly woman was taping up a protest slogan calling for “Real Universal Suffrage” as a few others examined schedules of upcoming events and the crowd of shoppers and commuters streamed past. Many of the posters that circulated through online channels were also printed out for heavily trafficked subway stations, malls, and pedestrian overpasses. The events that had occurred here (beginning with the large rally on July 14) turned the mall into a node within a network of protest spaces across the city: a physical waystation and also a place for commemoration of the rallies that occurred here previously. This small information hub was a physical equivalent of the Telegram channel, a place where images from Telegram were fixed to actual urban space, allowing those who weren’t on the network to learn of upcoming events ((a–c)).

Figure 5. Selected photos of protest events. (a) A large rally held on 19 January 2020 at Chater Garden (Photo by author, January 2020). (b) Passersby examine a protest event wall at Sha-Tin New Town Plaza (Photo by author, January 2020). (c) Pop-up Chinese New Year market held at an industrial building in Kwun Tong (Photo by author, January 2020).

Discussion

This study focused on the changing spatial pattern of urban protest as it evolved in relation to new digital tools used to organize protest events. This coevolution of place-based and digital forms of protest was examined specifically in the context of the Hong Kong 2019–2020 Anti-ELAB protest. The study also sought to identify certain contextual factors that likely influenced this dynamic interaction between digital tools and urban space. By analyzing the spatial dispersal of protest events over the course of the movement, and performing a partial network analysis of Telegram channels, this research documented the increasing geographic dispersion of protest activities over time and the role of Telegram in facilitating a shift to neighborhood-level organizing. As the movement responded to state repression, the shift away from open occupation of central locations to more ad-hoc neighborhood events allowed the movement to deepen support within the city and create alternative place-based social networks.

The Anti-ELAB protests ground to a halt due to the restrictions on protests imposed during COVID-19 and the National Security Law that passed in June 2020. However, subsequent protests against military-led governments in Thailand and Myanmar borrowed many of the “be water” tactics innovated in Hong Kong (Solomon, Citation2020), suggesting the relevance of the emerging protest dynamics discussed in this paper in other contexts, particularly other non-democratic countries. This is one avenue for further research. While this research focuses on Hong Kong, there are important implications for the future of urban protest more generally. These include: (1) a shift toward the use of diverse urban spaces as protest venues, (2) the potential for digital tools to strengthen local social capital; and (3) the continued tension between social movements and state repression in the use and development of technology.

Diversity of protest sites

The first of these implications pertains to how physical spaces within a city are utilized for protests. While symbolic public spaces such as squares and parks have been popular choices for urban protests worldwide (AlSayyad, Citation2012; Davis & Raman, Citation2013; Hatuka, Citation2016, Citation2018), the 2019–2020 protests revealed how quotidian spaces within Hong Kong were creatively mobilized as spaces of protest: for instance, streets, MTR stations, mountaintops, malls, empty industrial buildings, and university campuses. Faced with a government unaccountable to citizens, protesters shifted away from trying to “challenge socio-spatial distance” (Davis, Citation1999; Hatuka, Citation2016) with the Hong Kong government by occupying central spaces. This involved a “reverse scale shift” (Tarrow & McAdam, Citation2005) to neighborhoods to maintain momentum and consolidate the movement within the city. Symbolic squares and parks were used primarily to organize events with international themes, suggesting that symbolic public spaces in Hong Kong had more importance in communicating the protest to a global audience than in confronting the Hong Kong SAR government. The digitally networked “global public square” still depended on the occupation of physical urban space, and the synchronous hosting of events in Hong Kong with sympathetic activists in cities such as London, New York, Melbourne, and Toronto.

Meanwhile, quotidian spaces like malls served as convenient locations for protesters in different neighborhoods to gather. Malls in Hong Kong, with their dual function as sites of both consumption and community centers (Al et al., Citation2016; Chu, Citation2018) were transformed into politicized spaces through the actions of protesters. Given the centrality of malls to global consumer culture and their geographic centrality within cities and neighborhoods (particularly in Asian cities) the mall could become a common site for future protests. Bangkok’s anti Royalist protests in 2019 and 2020 also flocked to the city’s central malls. As frequent destinations for young people, malls may become more significant in future movements than the symbolic sites in the city where protests have typically occurred. Does this suggest a turn away from the “public sphere” as traditionally conceived (Calhoun, Citation1992; Habermas, Citation1962), or simply a new evolution of the public sphere?

Social capital and neighborhood networks

Related to the question of the “public sphere” is the concept of social capital. The decline of traditional civic institutions has been widely documented, particularly in the post-industrial world (Putnam, Citation2000). The decline of unions and mainstream parties has been accompanied by a corresponding shift from “collective” to “personal” action frames in social movements (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2013), and a turn toward “experiential protest” (Pasotti, Citation2020). Some of these trends can be observed in Hong Kong, particularly the rise of experiential protests such as pop-up markets, singing, and the “yellow economy” of pro-protest shops.

Yet, it would be misleading to wholly explain Hong Kong’s protests with theories generated from elsewhere. New forms of protest in Hong Kong didn’t necessarily involve a rise in “personal action frames” at the expense of “collective action” frames. In fact, the emergence of a Hong Kong collective identity is evident in the Anti-ELAB protests. Labor unions, school groups, and other organizations remained active in the protests, including on Telegram. Therefore, the rise of what I term “new ad-hoc place-based networks” did not obviate a role for institutions and groups. Rather, Telegram provided new modes for participation at the hyperlocal scale, bringing people into the movement, and allowing for additional neighborhood-based groups to emerge.

This begs the question: could tools innovated during the movement actually strengthen civic engagement rather than weaken it? As the protests tapered off in 2020, the deployment of Telegram groups for other non-protest uses such as community information boards offered some evidence of increased community engagement. As of January 2021, some neighborhood Telegram channels were being used for other purposes. At least one Telegram channel “Reclaim Hung To” that originally formed to advertise protests in the neighborhood of Hung To on July 27 2019, subsequently posted news from a pro-Democracy local district councilor. Tufekci (Citation2020) argued that the civil society infrastructure fostered during the protests helped citizens share information about COVID-19 despite public mistrust of the government. While some social capital fostered on Telegram may have endured, the National Security Law passed in June 2020 chilled Hong Kong’s civil society. The government, with China’s backing, has used the law to curtail even the most innocuous forms of dissent, eroding many of the remaining freedoms of speech and protest that Hong Kong once enjoyed.

One limitation of Telegram compared to Facebook and Twitter is that it was less useful for communicating messages beyond Hong Kong. In fact, a crucial failing of the movement was its inability to reach sympathetic audiences on the mainland, which could have pressured the Chinese government to make concessions. Of course, it’s difficult if not impossible for protest messages to circumvent China’s “Great Firewall.”

The future of urban protest in an age of global authoritarianism

The findings from this study suggest that the theories and scholarship generated from the social media fueled protests of the early 2010s requires updating. Recent scholarship has emphasized the continued importance of place to digitally networked movements (Haffner, Citation2019; Miller & Nicholls, Citation2013; Nicholls, Citation2009; van Haperen et al., Citation2018). Yet, most of this scholarship has focused on movements in democratic countries where protest remains protected by law. With the rise of global authoritarianism (Diamond et al., Citation2016), the future of urban protest is increasingly uncertain. Digital networks and other communications technologies, far from enabling a “space of autonomy,” as (Castells, Citation2012) hoped, have become tools of state repression. In societies like Hong Kong, where heightened government surveillance led to a fear of protesting openly, the role of place and social networks differs from that observed in other contexts. Instead of relying primarily on existing place-based networks or stored social capital, movements may need to innovate new networks on the go, forming new solidarities that paradoxically rely on a degree of anonymity to ensure the trust and participation of those fearful of arrest.

Subsequent events in the region displayed both the attractiveness and limitations of these new forms of protest. Protests against military governments in Myanmar and Thailand adopted many of the “be water” tactics directly from Hong Kong. Yet in June 2020, Hong Kong passed a National Security Law targeting “terrorism, subversion, secession, and collusion” with foreign forces, which has since been used to curtail many forms of political expression (Ramzy, Citation2021).

Conclusions

This study brings together earlier investigations of the role of urban space and place-based networks in protest movements with literature on the role of social media in urban protests. By so doing, this research has been able to explicitly examine the dynamic interplay between place-based events and online organizing over an extended period of time.

One limitation of this study is that it utilized materials downloaded from online channels and did not include structured interviews or surveys of movement participants. Those methods might have shed additional light on the motivations and strategies of protestors. While the study foregrounded the relationship between Telegram channels and planned event locations, it did not examine other aspects of spatial use in a detailed way, such as protestors’ use of real-time crowdsourced mapping and countersurveillance of police movement. These additional facets of the “be water” strategy warrant further study.

This study contributes to the literature on social movements in some important ways. At an empirical level, the spatial analysis of Hong Kong protest events presented here reveals the increasing spatial dispersion of protest venues and diversification of protest events that occurred from the Umbrella Movement in 2014 through the Anti-ELAB protests in 2019–2020. Analysis of Telegram channels indicates how they facilitated the formation of neighborhood-based social networks that took on a greater role in organizing events as the movement continued. The findings suggest a dynamic coevolution of place-based and online organizing: while preexisting networks were instrumental in the early stages of the movement, the Telegram neighborhood groups played a greater role as state repression gradually weakened the capacity of existing institutions to organize large rallies. Whereas open platforms like Facebook and Twitter are useful for disseminating information to wider audiences, Telegram played a coordinating function. The Telegram ecosystem allowed for some centralization of information while enabling breakout channels to organize a wider variety of events. This allowed participants to engage in ways they felt comfortable and may have helped avoid the internal divisions seen in the Umbrella Movement. This digital ecosystem knit together citywide and neighborhood groups, and incorporated specialized functions such as countersurveillance, sharing of tactics, and legal and psychological support, just to name a few.

These findings suggest that while “place-based social networks” remain crucial to social movements, scholars should consider the ways in which both technology and the changing forms of state repression condition how such networks themselves are constituted and evolve over time. The advent of “hyper-local” protest organizing is an iteration on the “digitally networked protests” first seen in the early 2010s. The increasing ubiquity of smartphones, means that digital devices are intercalated with urban space at a finer spatial scale, allowing social movements to use urban space more dynamically in real time and for a wider variety of formats. At the same time, given the increasing ability of authoritarian governments to surveil both digital and physical space, the autonomy and durability of local social capital cannot be taken for granted. Encrypted platforms offer one way of creating place-based weak ties on the fly in social movements, thus helping catalyze new forms of place-based solidarity that supplement existing or “traditional” place-based institutions. Whether this new form of social capital will endure is an open question. As in other social movements, the impact may not be fully discernible now but will be seen in the ways future movements learn from and build upon the tools and tactics innovated in the streets of Hong Kong.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Brent D. Ryan, Diane E. Davis, and Jeffrey Wasserstrom for their early suggestions, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments during the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Founded in 2002, CHRF was an alliance of most of Hong Kong’s “pan-Democratic” opposition parties, and was involved in organizing many of the large marches and rallies such as those in June 2019. It disbanded in August 2021, following the National Security Law.

2 These channels are with their name followed by link: 香港人抗爭日程表文宣頻道 (t.me/HK_Schedule), 反送中 文宣谷 Channel (t.me/hkstandstrong_promo), and 香港人日程表整合頻道 (t.me/hongkongertimetable).

3 Many of the posters refer to the same events or do not reference a specific event.

4 During the Umbrella Movement, participants created walls of post-it notes with slogans on them, and this practice continued during 2019–2020. For more see, Hou (Citation2020).

5 Pacific Place and Taikoo Place are both owned by Swire, a British-owned Hong-Kong-based conglomerate with a long history dating back to the Colonial era. This foreign ownership was thought by some to make them more sympathetic to the protests.

References

- Al, S., Cartier, D. C., Chu, C. L., Lai, T.-Y. S., Mathews, G., Nowek, A., Shane, D. G., Shelton, B., & Solomon, J. D. (2016). Mall City: Hong Kong’s dreamworlds of consumption. University of Hawaii Press.

- AlSayyad, N. (2012). The virtual square: Urban space, media, and the Egyptian uprising. Harvard International Review, 34(1), 58–63.

- AlSayyad, N., & Guvenc, M. (2015). Virtual uprisings: On the interaction of new social media, traditional media coverage and urban space during the ‘Arab Spring’. Urban Studies, 52(11), 2018–2034.

- Andersen, R. (2020, July 29). The panopticon is already here. The Atlantic, September 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/china-ai-surveillance/614197/

- Barber, E. (2014, December 12). Inside Hong Kong’s (surprisingly comfortable) protest camps. Time. https://time.com/3581690/life-in-hong-kong-occupy-protest-camps/

- Bastos, M. T., Recuero, R. D. C., & Zago, G. D. S. (2014). Taking tweets to the streets: A spatial analysis of the vinegar protests in Brazil. First Monday, 19(3), Article 3.

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, W. L. (1998). 1998 ithiel De Sola pool lecture: The UnCivic culture: Communication, identity, and the rise of lifestyle politics. PS: Political Science and Politics, 31(4), 741–761.

- Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4–17.

- Borge-Holthoefer, J., Rivero, A., García, I., Cauhé, E., Ferrer, A., Ferrer, D., Francos, D., Iñiguez, D., Pérez, M. P., Ruiz, G., Sanz, G., Serrano, F., Viñas, C., Tarancón, A., & Moreno, Y. (2011). Structural and dynamical patterns on online social networks: The Spanish May 15th movement as a case study. PLoS One, 6(8), e23883.

- Calhoun, C. J. (1992). Habermas and the public sphere. MIT Press.

- Castells, M. (1983). The city and the grassroots: A cross-cultural theory of urban social movements. University of California Press

- Castells, M. (1992). The informational city: Economic restructuring and urban development (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age. Polity Press.

- Cheng, E. W. (2019). Spontaneity and civil resistance: A counter frame of the umbrella movement. In N. Ma & E. W. Cheng (Eds.), The umbrella movement (pp. 51–76). Amsterdam University Press.

- Cheng, K. (2019, November 7). Hong Kong gov’t bans dry goods, including satirical items, at Lunar New Year fairs. Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. https://hongkongfp.com/2019/11/07/hong-kong-govt-bans-dry-goods-incl-political-satire-lunar-new-year-fairs-citing-crowd-control/

- Chow, S.-l., Fu, K.-w., & Ng, Y.-L. (2020). Development of the Hong Kong identity scale: Differentiation between Hong Kong “locals” and mainland Chinese in cultural and civic domains. Journal of Contemporary China, 29(124), 568–584.

- Chu, C. (2018). Narrating the mall city. In S. Al (Ed.), Mall City: Hong Kong’s dreamworlds of consumption (pp. 83–90). University of Hawaii Press.

- Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M., Goncalves, B., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2011). Political polarization on twitter. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 5(1), Article 1. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14126

- Dapiran, A. (2017). City of protest: A recent history of dissent in Hong Kong. Penguin Random House Australia.

- Davis, D. E. (1999). The power of distance: Re-theorizing social movements in Latin America. Theory and Society, 28(4), 585–638.

- Davis, D. E., & Raman, P. (2013). The physicality of citizenship: The built environment and insurgent urbanism. Thresholds (41), 60–71.

- Diamond, L., Plattner, M. F., & Walker, C. (2016). Authoritarianism goes global: The challenge to democracy. JHU Press.

- Diani, M., & McAdam, D. (2003). Social movements and networks: Relational approaches to collective action. Oxford University Press.

- Doerr, N., Mattoni, A., & Teune, S. (2015). Visuals in social movements. In D. Della Porta & M. Diani (Eds.), The oxford handbook of social movements (pp. 1–13). Oxford University Press.

- Foucault, M. (2012). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage.

- Gibson, J. (1977). The theory of affordances. In R. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting, and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology (pp. 76–82). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Gould, R. V. (1993). Trade cohesion, class unity, and urban insurrection: Artisanal activism in the Paris commune. American Journal of Sociology, 98(4), 721–754.

- Graham, S., & Marvin, S. (1995). Telecommunications and the city: Electronic spaces, urban places. Routledge.

- Granovetter, M. (1977). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 347–367.

- Greitens, S. C. (2020). Dealing with demand for China’s global surveillance exports. Brookings.

- Habermas, J. (1962). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. John Wiley & Sons.

- Haffner, M. (2019). A place-based analysis of #BlackLivesMatter and counter-protest content on Twitter. GeoJournal, 84(5), 1257–1280.

- Hale, E. (2019, October 13). Hong Kong protesters use new flashmob strategy to avoid arrest. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/13/hong-kong-protesters-flashmobs-blossom-everywhere

- Harvey, D. (2001). Spaces of capital: Towards a critical geography (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Hatuka, T. (2018). The design of protest. University of Texas Press.

- Hatuka, T. (2016). The challenge of distance in designing civil protest: The case of resurrection city in the Washington mall and the occupy movement in zuccotti park. Planning Perspectives, 31(2), 253–282.

- Hatuka, T., & Toch, E. (2016). The emergence of portable private-personal territory: Smartphones, social conduct and public spaces. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2192–2208.

- Holbig, H. (2020). Be water, My friend: Hong Kong’s 2019 anti-extradition protests. International Journal of Sociology, 50(4), 325–337.

- Hou, J. (2020, January 4). Hong Kong’s sticky-note revolution. Smithsonian Magazine, January 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/hong-kongs-sticky-note-revolution-180974042/

- Hui, M. (2019). How shopping malls became a battleground in Hong Kong’s protests. Quartz. https://qz.com/1671507/shopping-malls-are-battlegrounds-in-hong-kongs-protests/

- Hutchby, I. (2001). Technologies, texts and affordances. Sociology, 35(2), 441–456.

- Juris, J. S. (2005). The new digital media and activist networking within anti-corporate globalization movements. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 597(1), 189–208.

- Juris, J. S. (2012). Reflections on #Occupy everywhere: Social media, public space, and emerging logics of aggregation. American Ethnologist, 39(2), 259–279.

- Lam, J., Ng, N., & Su, X. (2019, June 22). Be water, my friend: How Bruce Lee has protesters going with flow. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3015627/be-water-my-friend-protesters-take-bruce-lees-wise-saying

- Lee, F. L. F., & Chan, J. M. (2018). Media and protest logics in the digital era: The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. Oxford University Press.

- Lee, F. L. F., & Chan, J. M. (2016). Digital media activities and mode of participation in a protest campaign: A study of the Umbrella Movement. Information, Communication & Society, 19(1), 4–22.

- Lee, P. S. N., So, C. Y. K., & Leung, L. (2015). Social media and Umbrella Movement: Insurgent public sphere in formation. Chinese Journal of Communication, 8(4), 356–375.

- Leung, Y. M.. (2016). Mediating movement in occupied spaces : documentation on social media pages in the context of the Umbrella Movement. In J. C. Ong & M. Rovisco (Eds.), Taking the square: Mediated dissent and occupations of public space (pp. 139–156). Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Lin, L. (2002). City and quasi-public space: A study of the shopping mall system in Hong Kong. China Perspectives, 39(January February 2002), 46–52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24051014

- Liu, N., & Wong, S.-L. (2019, July 2). How to mobilise millions: Lessons from Hong Kong. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/0008b1aa-9bec-11e9-9c06-a4640c9feebb.

- Martin, D. G. (2003). “Place-Framing” as place-making: Constituting a neighborhood for organizing and activism. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(3), 730–750.

- Miller, B., & Nicholls, W. (2013). Social movements in urban society: The city as a space of politicization. Urban Geography, 34(4), 452–473.

- Mitchell, W. J. (1996). City of bits: Space, place, and the infobahn. MIT Press.

- Mozur, P. (2019, July 26). In Hong Kong protests, faces become weapons. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/26/technology/hong-kong-protests-facial-recognition-surveillance.html

- Mozur, P., Kessel, J. M., & Chan, M. (2019, April 24). Made in China, exported to the world: The surveillance state. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/24/technology/ecuador-surveillance-cameras-police-government.html

- Ng, E. (2014, December 17). Explainer: Umbrella Movement lives on with the rise of the “Shopping Revolution”. Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. https://hongkongfp.com/2014/12/17/umbrella-movement-lives-on-with-the-rise-of-the-shopping-revolution/

- Nicholls, W., Miller, B., & Beaumont, J. (2013). Spaces of contention: Spatialities and social movements. Routledge.

- Nicholls, W., & Uitermark, J. (2016). Cities and social movements: Immigrant rights activism in the US, France, and the Netherlands, 1970-2015 (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Nicholls, W. (2009). Place, networks, space: Theorising the geographies of social movements. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 34(1), 78–93.

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Collins, K. M. T. (2007). A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report, 12(12), 281–316.

- Pasotti, E. (2020). Resisting redevelopment: Protest in aspiring global cities. Cambridge University Press.

- Picon, A. (2015). Smart cities: A spatialised intelligence. John Wiley & Sons.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Ramzy, A. (2021, October 25). With new conviction, Hong Kong uses security law to clamp down on speech. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/hong-kong-security-law-speech.html

- Rane, H., & Salem, S. (2012). Social media, social movements and the diffusion of ideas in the Arab uprisings. Journal of International Communication, 18(1), 97–111.

- Rodríguez-Amat, J. R., & Brantner, C. (2016). Space and place matters: A tool for the analysis of geolocated and mapped protests. New Media & Society, 18(6), 1027–1046.

- Rovisco, M., & Ong, J. C. (2016). Taking the square: Mediated dissent and occupations of public space. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

- Sassen, S. (1991). The global city: New York, London, Tokyo (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Schectman, J. (2019, August 31). Exclusive: Messaging app Telegram moves to protect identity of Hong Kong protesters. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-telegram-exclusive-idUSKCN1VK2NI

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Sikkink, K. (2005). Patterns of dynamic multilevel governance and the insider-outsider coalition. In D. Porta & S. Tarrow (Eds.), Transnational protest and global activism (pp. 24). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Solomon, F. (2020, October 18). Thailand’s protests shift tactics, influenced by Hong Kong. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/front-lines-and-hand-signals-thailands-protests-shift-tactics-influenced-by-hong-kong-11603039354

- Soule, S. A., & Roggeband, C. (2018). Diffusion processes within and across movements. In D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, H. Kriesi, & H. J. McCammon (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to social movements (pp. 236–251). John Wiley & Sons.

- Soule, S. A. (1997). The student divestment movement in the United States and tactical diffusion: The shantytown protest. Social Forces, 75(3), 855–882.

- Tarrow, S., & McAdam, D. (2005). Scale shift in transnational contention. In D. Della Porta & S. Tarrow (Eds.), Transnational protest & global activism (pp. 121–151). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Tilly, C. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. Addison-Wesley.

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2015). Contentious politics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Townsend, A. M. (2021). Life in the real-time city: Mobile telephones and urban metabolism. Journal of Urban Technology, 7(2), 85–104.

- Tuan, Y.-F. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Tufekci, Z. (2018). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest (Reprint ed.). Yale University Press.

- Tufekci, Z. (2020, May 12). How Hong Kong did it. The Atlantic, May 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2020/05/how-hong-kong-beating-coronavirus/611524/

- Urman, A., Ho, J. C.-t., & Katz, S. (2021). Analyzing protest mobilization on Telegram: The case of 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill movement in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE, 16(10).

- Urman, A., & Katz, S. (2020). What they do in the shadows: Examining the far-right networks on telegram. Information, Communication & Society, 0(0), 1–20.

- van Haperen, S., Nicholls, W., & Uitermark, J. (2018). Building protest online: Engagement with the digitally networked #not1more protest campaign on Twitter. Social Movement Studies, 17(4), 408–423.

- Veg, S. (2016). Creating a textual public space: Slogans and texts from Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. The Journal of Asian Studies, 75(3), 673–702.

- Veg, S. (2017). The rise of “localism” and civic identity in post-handover Hong Kong: Questioning the Chinese nation-state. The China Quarterly, 230(June 2017), 323–347.

- Vincent, D. (2019, June 29). How apps power Hong Kong’s “leaderless” protests. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-48802125

- Vir, J., & Hall, K. (2018). News in social media and messaging apps. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University. http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/publications/2018/news-social-media-messaging-apps/

- Yuen, S. (2018). Contesting middle-class civility: Place-based collective identity in Hong Kong’s occupy Mongkok. Social Movement Studies, 17(4), 393–407.