ABSTRACT

Through a comparative analysis of Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis, this paper examines the emergence of financialized austerity urbanism as a mode of governance through which racialized patterns of infrastructure inequalities are produced, particularly regarding water and sewer provision. Following the 2008 financial crisis, Black-majority cities have employed disciplinary financial rules and routines around debt collection when issuing loans in the bond market to make up for budget shortfalls, a process which has led to mass water shut offs, housing foreclosures and wage garnishments to collect on increasing household water and sewer debt. This paper explores the interactions of race, municipal finance and urban governance by providing case study evidence on the implications of racism and racialization embedded within credit ratings in the municipal bond market. I demonstrate how there has been a financial deepening of Black-majority cities through pressure to satisfy municipal bondholders and meet their debt obligations. Punitive methods such as mass water shut offs and other debt collection practices are the outcomes of downloaded debt onto local spheres following the 2008 economic crisis, and what happens when residents are squeezed to their limits. The innerworkings of austerity urbanism, I argue, is driven by the logics of financialization and operates through urban geographies of racial capitalism.

Introduction

According to the US Fines & Fees Justice Center, the criminalization of poverty is one of the main factors driving police violence in the United States (FFGC, Citation2020). With George Floyd and countless others before him, law enforcement uses alleged crimes of poverty to justify dehumanizing and killing people of color. Only a few years ago after a police officer killed Michael Brown in Ferguson in St. Louis for selling CDs, the Justice Department’s investigation found a pattern of racially discriminatory practices incentivized by the city’s dependence on the criminal justice system to raise revenue (U.S DOJ, Citation2015). On a more mundane level, the same practices exist to manage debt and the fiscal crises of municipalities caused mostly by the dynamics of the financial market. American cities, and in particular, Black-majority cities, rely on the punitive enforcement of fines and fees to fund basic municipal services in an austere fiscal environment produced by the 2008 financial crisis. These punitive practices are increasingly being used to collect debt for local services, such as water and sewer provision. Over the last 10 years, there has been a wave of mass water shut offs happening across US cities in tandem with rising bills due to ongoing austerity policies (Food and Water Watch, Citation2018). In this sense, infrastructure financialization in post-industrial, Black-majority cities is contingent on uneven terrains of racialized urban development and geographies of austerity through decades-long historical disinvestment in urban infrastructure systems in Black communities (Melosi, Citation2000). Considering work that articulates how infrastructure, race and capital produce “hierarchical regimes of reproduction” (McIntyre & Nast, Citation2011, p. 1466) and “surplus populations” in inner-cities (Gilmore, Citation2002; McIntyre & Nast, Citation2011), the collusions of municipal finance, austerity governance and debt can articulate how financial risks are unevenly placed on Black cities and households. Municipal bond institutions and practices devalue Black spaces through accounting measures of debt collection methods and rates of delinquency as preconditions to issue loans to municipalities to measure creditworthiness. Such financial practices have led to a water access and affordability crisis in Black-majority US cities.

By using approaches on the intersections of racial capitalism and municipal debt and the extractive relationship between white and black enclaves through municipal finance techniques (Seamster and Purifoy, Citation2021), I highlight how debt expropriation is a racializing process embedded in the financialized austerity governance of cities. The intent is to facilitate a dialogue between the emerging literatures on Black urban geographies, financialization, and austerity urbanism that takes seriously the racialized dimensions of austerity, and how debt serves as a method of dispossession in an age of financial capital. By drawing on case studies of the unaffordability and insecurity of water in Black-majority US cities and the types of local practices being rolled-out to manage debt, this research highlights new emerging trends of environmental injustices and infrastructure inequities between white and black spaces.

This paper argues that the financial sector and the municipal bond system reinforce racial inequality and uneven racialised development in U.S cities. Bond lending to municipalities and its financial logics are a racializing process that makes certain subjects suitable for expropriation and where finance capital is incentivized to increase the pool of urban residents marked “risky” to increase value and thereby extract profits in the municipal bond market. I use, as a case study, three Black-majority and post-industrial cities (Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis). The analysis is based on 60 semi-structured interviews and participant observation carried out with government officials, municipal bond financial experts, water and social justice organizations, and households from November 2018 to June 2019. The objective of these interviews was to engage with participants in their respective communities to highlight important narratives of their situated experiences as well as to provide a detailed picture of factual information. In addition, data was collected from local policy documents and financial statements, and local and national media coverage. This data enabled key points of contention to be placed within the wider shifting geographies of financialization, fiscal austerity and infrastructure provision across Black-majority US cities.

In the first section, I review literature on the relationship between austerity urbanism, financialization, and racial capitalism within the context of its potential to engage with prevailing patterns of racial domination to better understand how contemporary capitalist and financialized processes rely on certain racial preconditions to reproduce itself in the urban. Next, I provide the context of a water affordability crisis across Black-majority US cities created by speculative arrangements to finance infrastructure, and the institutionalization of disciplinary bond market rules and routines around debt collection this is increasingly demanded by bondholders as leverage. Third, I outline three debt collection methods in the form of water shut offs, housing foreclosures, and garnishing assets used in Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis. This paper concludes with two arguments and outlines further engagement. First, austere governance strategies, such as water and sewer debt collection practices, are unevenly dispensed in racialized ways. These strategies are institutionalized in municipal bond market procedures through municipal creditworthiness that operate through socio-spatial relations of racialization revealing urban moments of racial capitalism of racialized value creation where “coconstructed dynamics of empire play out in global cities” (Ponder, Citation2021, p. 1). Secondly, the distinctive austere measures employed by each city to collect owed debt is being used to make up for revenue shortages following the 2008 financial crisis (Aalbers, Citation2019; Singla et al., Citation2020; Wang, Citation2018).

Financialization, austerity, and racial capitalism

In the context of the financialization of infrastructure, scholars have looked at how this has reconfigured the role of local governance to take on market-oriented risk (Farmer, Citation2014; Fields, Citation2017; Furlong, Citation2020; Weber, Citation2010). In some cases, this means governance expands the scope of financialized infrastructure regulation beyond the asset itself to encompass “punitive” activities needed for continuous accumulation of capital (Farmer, Citation2014). As global finance capital unlocks value embedded in the material-spatial configuration of infrastructure – it expands its power over everyday urban life. This can be understood as what Rosenman (Citation2019) describes as “finance-as-governance” (p. 1129) where local governments are increasingly using debt collection practices as revenue-generating mechanisms to meet municipal debt obligations and protect the interest of financial investors. In this sense, bondholders and the practices of rating agencies monitor and discipline municipalities to adhere to fiscal and economic policy that benefits investors in a similar way that the IMF and World Bank serve as policing institutions to adhere to a neoliberal order in the Global South. Municipal bond rating agencies have been understood by Hackworth (Citation2007) as the most influential “police officers” of neoliberal urban governance.

The punitive enforcement of local revenue demonstrates the financial power into the public functions of the city where municipalities are finding new mechanisms for extracting fees from residents under austere agendas. To better understand how the municipal bond market regulates access to water, this paper reads financialization alongside work of racial capitalism (Bhattacharyya, Citation2018; Bledsoe & Wright, Citation2019; Gilmore, Citation2007; Lowe, Citation2015; Melamed, Citation2015; Robinson, Citation2000) and urban governance, particularly emerging literature around the racialized unevenness of austerity urbanism, the environment, and municipal finance (Bonds, Citation2018; Jenkins, Citation2021; Ponder & Omstedt, Citation2019; Pulido, Citation2016; Ranganathan, Citation2016). I draw on the literature on racial capitalism to interrogate the racial logics of municipal finance and austerity urbanism.

The term “racial capitalism” explains the vital role of race and racism in the development of capitalist society. Scholars use racial capitalism to describe how race/racialization/racism combined with capitalist relations to describe the origins of industrial capitalist development through periods of slavery and colonization (Bhattacharya, 2018; Kelley, Citation2017; Robinson, Citation2000 [1983]) and to highlight how coercion is integral for capital investment (Baptist, Citation2014; Gilmore, Citation2002; Johnson, Citation2017; Robinson, Citation2000). Finance, municipal debt, and forms of post-crisis urban governance have begun to be theorized through the lens of racial capitalism (Jenkins, Citation2020; Citation2021; Millington & Bigger, Citation2020; Ponder, Citation2017; Pulido, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2018). According to Wang (Citation2018), local, state, and federal institutions “manage” Black communities through tactics, such as extracting and looting, confinement, and gratuitous violence. Wang goes to great lengths to demonstrate that this “policing as plunder” is explicitly raced, through what refers as the “racial kapitalstate.” When local budgets are struggling, it is imperative that “municipalities must fuck over residents by instituting austerity measures […] As demonstrated by the case of Ferguson, in order to remain solvent, municipalities develop a parasitic relation to the people they are supposed to serve” (Wang, Citation2018, p. 182).

Others such as Jenkins (Citation2020, Citation2021) and Ponder (Citation2017) show how the municipal bond market structures racial advantages for whites based on creditworthiness, an assessment of investment risk understood by bond market analysts to be grounded in “objective economic conditions” (Jenkins, Citation2020). This then, determines who gets access to public services and who does not. Through the financial accounting of key indicators, such as “net debt to assessed valuation ratio, overlapping debt, and “economic” and “socioeconomic” factors such as population, industry, tax base, and welfare costs” bond analysts postulate future economic growth and the amount and interest rates on the loans based on these determinations (Jenkins, Citation2020). In this sense, municipal finance is measured based on the socio-economic spatialities of pre-existing racial inequalities, and thus, financial markets can never be insulated from power relations, such as race/racialization/racism.

A stream of literature on the financialization of local government examines a move towards more sophisticated techniques, such as derivatives instruments, to manage interest rates and risk (Hendrikse & Sidaway, Citation2014), reconfiguring the governance of municipal operations into private or public–private partnerships to capitalize on future income streams from public services and utilities (Allen & Pryke, Citation2013; Ashton, Doussard, & Weber, Citation2016; Whitfield, Citation2016), or marketing poverty management as a more inclusive financial instrument (Rosenman, Citation2019). Others such as Furlong (Citation2019) understands processes of infrastructure degradation in cities coping with the effects of state-restructuring form the central justification for financialization which places cities in an “infrastructural trap” (p, 574). Financialized urban governance for majority-Black cities entails moving towards more sophisticated techniques, such as derivative instruments, to lower interest rates and risk, and manage debt (Aalbers, Citation2019; Hendrikse & Sidaway, Citation2014). This has created what Jenkins (Citation2020) refers, to as a segregation of infrastructures. Urban geographies of racial capitalism can therefore be analyzed thorough the configuring of municipal debt in tandem with the neoliberalization of cities that has constituted the underdevelopment of Black America.

I, therefore, situate the political economy of Black-majority municipal debt within this framework, arguing that financialization has reshaped austere governance in Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis towards a local state that is dependent on extractive and coercive debt collection methods to make up for revenue shortfalls and to meet debt obligations for the interest of investors. Although water shut offs, for instance, have been used by local governments in the past when bills are unpaid, the mass scale of water shut offs across US cities came to fruition following 2008. Thus, austerity policies and its shifting responsibility from the state onto citizens are imposed differently in Black-majority cities than in white majority cities. For Black-majority cities, austerity has materialized into policing Black debt through carceral techniques that are embedded in municipal bond practices. This includes punitive debt collection practices, such as housing foreclosures, service shut offs, garnishing wages, and forms of incarceration for failure to pay municipal and civil fines, to squeeze revenue out of low-income residents by use of obfuscated force and dispossession for residents who could not afford to pay for those municipal services when fees were added or increased. An important question this paper examines is what are the ways in which cities are generating revenue to meet their contractual obligations to bondholders when households in Black-majority cities have been squeezed to their limits? What local mechanisms of austere governance have been used? This paper brings light to the interconnectedness of everyday financialization, race, and austere governance through the policing of debt in Black-majority cities.

Bond market discipline over black-majority cities

With the onset of the deregulation of the financial sector in 2000, traditional banking (through big banks) no longer provides short and long-term finance to municipalities, rather it is institutional investors, such as pension funds, hedge funds, insurance companies, and mutual funds (Sinclair, Citation2005, pp. 5–6). With this shift, bond rating agencies stepped in to provide an intermediary disciplinary role to satisfy investor demands for information on cities through superficial evaluation in the form of ratings (Omstedt, Citation2019; Paudyn, Citation2014). More importantly, beginning with the 1970s fiscal crisis that resulted in several defaults for municipalities, investors became worried about municipal debt and tightened control by pushing for more complete information on municipal bonds (Sinclair, Citation2005). The rating agencies responded by becoming more intrusive than they had been in the past on a municipalities’ fiscal policies.

The outcome of this led to bond rating agencies having a greater influence in shaping local governance as cities are forced to keep expenses low and revenues high to maintain a positive rating. Research on the municipal bond market since financial deregulation in 2000 shows that Black-majority cities are rated more speculatively than other cities (Ponder, Citation2018). Other influential work in economic sociology by Norris (Citation2021) highlights how credit ratings and scores operate as tools to institutionalize racism through municipal finance. Municipal credit ratings use inputs and methods for their criteria that are sourced from spaces of racial unevenness, such as whether cities have large populations that require more social support (Norris, Citation2021, p. 7). This can be related to how Black household debt is disciplined through using unconventional banking institutions, such as cash chequing institutions and payday loans with exorbitantly high interest rates. According to Seamster (Citation2019), Black debt is a key industry for creating white wealth as racial discrimination shapes who feels debt as crushing and who experiences it as an opportunity (p. 33). The result of this in cities has created a Black debtors’ prison compounded across neighborhoods and cities enforced through disclaimer measures, but where debt works relationally as it performs as an asset to bond rating agencies and the municipal bond market. For Black-majority cities, a municipality’s debt collection practices have become an important indicator of asset performance in the municipal bond rating process for investors who want assurance that there are local policies and practices in place for cities to collect on unpaid bills. The most prominent examples being Detroit’s filing for Paper 9 Bankruptcy, both Cleveland and Philadelphia’s attempt to structurally adjust to balance their budgets following declines in property taxes, and Jackson, Mississippi insolvency of their water department.

In October 2008, the Government Revenue Collection Association (GRCA) was founded by debt collection industry leaders. The organization works with the local and state governments across the United States to improve and enhance revenue recovery. Many US states since 2008 have allowed localities to privatize their debt collection services to third parties. For instance, a collection agency called Receivable Solutions Specialists, Inc. was recently hired by Adams County, Mississippi to collect $2 million in court and outstanding garbage collection fees and fines. In addition, Mississippi passed the Local Government Debt Collection Setoff Act that authorizes counties to collect debts against a person’s income tax refund (Robertson, Citation2019). Other examples include Chicago and Kendall County, Illinois hiring Harris & Harris to collect unpaid traffic tickets. Municipalities are increasingly outsourcing debt collection services or are creating new revenue-generating mechanisms through additional fines and fees for unpaid bills to make up for budget shortfalls. This includes a wide array of city services, such as unpaid property taxes, sanitation fees, traffic tickets, court fees, and water and sewerage services.

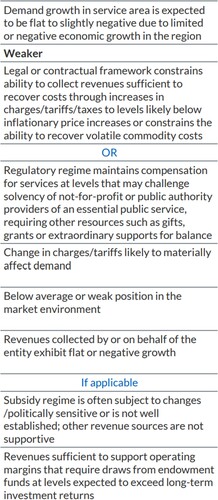

Processes of urban restructuring following 2008 have included “roll-out” technicalities and accounting measures used in the municipal bond market through rating agencies and investors to regulate and discipline debtors (Omstedt, Citation2019). Bond rating agencies and investors monitor a city’s collection rate and debt collection methods, and it is an integral part of the accounting process for rating bonds (p. 2). For instance, shows how Fitch Ratings categorizes a weak municipal water and wastewater credit rating based on debt collections.

In the case of water and sewerage services, utilities are required to disclose their debt collection practices for nonpayment of service to ensure leverage to investors. For Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis this includes late penalty charges, water shut offs, liens on property, garnishing wages, and housing foreclosures. There is a financial incentive to engage in egregious practices, such as water shut offs, if a city wants to access credit but has a high number of delinquencies (people who are unable to afford to pay their water bills), and therefore, are categorized and rated through the bond market as “high risk.” According to a financial investor who deals with the financial underwriting and creditworthiness of municipal entities, when it comes to water and sewer bonds, there is a due diligence questionnaire for each borrower to complete which asks municipalities to provide information on their debt collection methods, how they are being enforced, and what their collection rates are versus billing.Footnote1

Part of knowing that bondholders can get a return on investment is examining all the structures municipalities have in place so they can collect and hence, “bondholders require evidence that you’re going to be able to pay off your debt and meet your debt service obligations, this includes collection rates and methods.”Footnote2 Particularly, if one is a fiscally distressed borrower, “if they want to keep a certain credit rating so their bonds are cheaper, they have to be very aggressive on their collection. There is greater insurance to get better terms on loans the more effective these methods are.”Footnote3 For instance, in 2012, Philadelphia $71 million water and sewer revenue bonds were downgraded by Fitch Ratings. In the credit report, “below-average collection rates” were cited to be the major factor for their downgrade. The report also cited their collection rates of only at 87% which needed to be higher for a better rating, and that their enforcement debt collection methods through property tax liens were “only somewhat effective” (Fitch Ratings, Citation2012).

When a city is looking for investors to loan them money in the form of a municipal bond, they are required to disclose debt collection information about the bond offering through their preliminary offering statement to banks as well as their official statement.Footnote4 Some of the information that is included on debt collection methods are details of the types of penalties and fees charged, shut off policies, third-party debt collection agencies used, and so forth.Footnote5 In addition, other municipal officials mention how debt collection methods have become a selling point for municipal governments when looking to issue bonds. When meeting with investors, such methods are included in their presentations and reports.Footnote6 When local governments conduct presentations to credit rating agencies in advance of issuing water and sewer bonds, you can guarantee there will be a section on collection rates, water shut offs, and or forms of debt collection utilities decide to use based on the requirements municipalities have to disclose in their preliminary Official Statement that serves as an informational document on why investors should lend you money. Debt collection methods and collection rates are a key selling feature and are considered “good policy” to bondholders according to the Chief Financial Officer of Detroit’s Great Lakes Water and Sewerage Authority (GLWA).Footnote7

Debt collection practices can also be part of a municipal bond covenant. The cornerstone of a bond’s legal structure is its covenants, which are legally binding rules to which the utility agrees when issuing the bonds. Utilities abide by many different types of covenants, which can include debt service coverage, what water and sewer rates should be set at, the debt service reserve fund, and other things that will assure investment risk such as, ways of collecting debt. Utilities usually enter a debt service coverage covenant under which they pledge to achieve a given level of coverage each year. The covenant ensures that the utility utilizes its assets to generate sufficient income to pay bondholders and cover operating and capital expenses, plus more to adjust for any sort of future financial risks. This means that often water and sewer rates need to be set where they can meet a 1.2× – 3.0× coverage (in this case, making a profit of one to three times more than needed to operate for bondholder insurance). Weak covenants that allow the utility to operate on a thin margin (1.0x) often mean utilities are rated speculatively and will pay higher interest on their loans (Moody’s, Citation2014, pp. 13–16). This can create a cycle of raising water and sewer rates to appease bondholders and bond rating agencies to meet these covenants, but in turn making these services unaffordable. In this way, disclosing debt collection practices and setting water and sewer user fees to fund water and sewerage services has become institutionalized in the politics of municipal bond rating. I extend this argument below by demonstrating the socio-spatial variations of debt collection techniques used to manage austerity and financial risks in each city.

Water shut offs

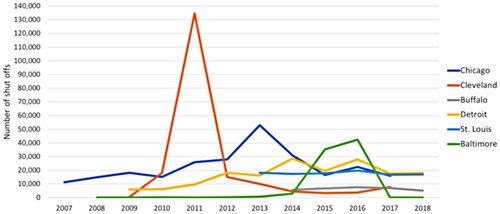

The most common and widespread debt collection practice in US cities for water debt is shut offs. At their peak, Detroit shut off 30,000 households’ water in 2014, Baltimore shut off 42,000 in 2016, and St. Louis shut off water to nearly 21,000 households in 2016, their highest number of shut offs recorded (see ). According to Roger Colton, a leading water affordability expert in the United States, “the data shows that we’ve got an affordability problem in an overwhelming number of cities nationwide that didn’t exist a decade ago, or even two or three years ago in some cities.” Between 2010 and 2018, water bills have increased from 27% to 154% in US cities, although median household incomes increased only 3% per year (Lakhani, Citation2020).

Figure 2. Annual water shut offs in black-majority US cities (2007–2018).

Due to rising capital costs and diminishing federal funds, some cities have downloaded these responsibilities onto its citizens to please municipal bond market investors using punitive measures, such as water shut offs, tax liens (a legal claim on a house linked to an unpaid water debt), and through debt collection agencies by garnishing wages. Like mortgage foreclosures, water shut offs and liens can force affected households to abandon their homes. Water debts are clustered in communities of color which disproportionately devalues their homes and neighborhoods. The average majority-Black city had a water bill burden more than twice that of the average majority-white city (Food and Water Watch, Citation2018, p. 9).

The Head of St. Louis’ Water Division understood water shut offs as the only available mechanism to mitigate financial risks of losing revenue from delinquencies and not being able to meet debt obligations, indicating “we have a process that when we have delinquent bills, our method of collection is to turn off because we have leverage.”Footnote8 Similarly, a State of Michigan policymaker that leads the EPA State Revolving Funds program that gives loans for water infrastructure to Detroit, rationalizes water shut offs for cash-strapped cities who have high levels of debt and a declining tax base because the money has got to come from somewhere to keep the water and sewerage systems operating and “the ultimate hammer is shut offs.”Footnote9 In these cities, water departments began charging additional fees and penalties, such as a disconnection and reconnection fee, and only offering a short amount of time to pay their bills before facing shut off. Detroit was more punitive than Baltimore and St. Louis, for instance, in requiring households to pay an upfront cost or a down payment, usually a percentage of their water debt before the city reconnected their water. On top of having unaffordable water rates, these cities add additional fees to punish those who fail to pay, placing many in a cycle of long-term water debt. is a comprehensive list of each city’s water shut off policy showing the timeframe of household disconnections with unpaid water and sewer bills and showing additional charges utilities add to late or unpaid bills ().

Table 1. City-level water shut off policies.

The examples of Detroit, Baltimore, and St. Louis are broadly similar, but the details vary significantly. The next sections address the conditions that led to the hyper policing of debt collection and municipal fine farming of water and sewer services, and alternative methods of criminal prosecutions, housing foreclosures, and court orders, that are being used in each city.

Detroit’s Municipal Bankruptcy and criminalizing the right to water

Detroit is marked by inequality materialized in the city’s infrastructures. This is rooted in remnants of the loss of their manufacturing industry, and institutional racism in city planning, housing and the labor market (Safransky, Citation2014; Sugrue, Citation2014). In 2014, shortly after filing the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history, the city launched a massive water shut off program that has disconnected at least 170,000 households since.Footnote10 Massive water shut offs were so severe during this time that the United Nations were called and concluded the debt collection scheme violated human rights and condemned the disproportionate impact on Black communities (Carmody, Citation2014). Although water delinquencies existed before Detroit was declared in state of financial emergency by Governor Rick Snyder (State of Michigan, Citation2013), there was no history of mass water shut offs until the bankruptcy.Footnote11 Mass water shut offs were part of emergency management’s local state-restructuring plan following 2008 to make the water department’s municipal bonds “more marketable for privatization and to sell off Detroit’s biggest asset – its water system” by showing to bondholders and rating agencies they were serious about collecting delinquent water accounts.Footnote12 Detroit’s financial crisis quickly became a water crisis. Eric Rothstein, who was hired by the city’s emergency manager as a financial consultant to restructure Detroit’s water department, acknowledges that he viewed the bankruptcy as being the catalyst that “put pressure on the city to make sure that you’re able to collect revenue to meet your obligations to bondholders.”Footnote13

Leading up to the bankruptcy in March 2013, restructuring consultants hired by the State of Michigan and city department officials created a report to oversee DWSD’s assets and to make recommendations on the future viability of the water department under the control of the city. In the report it was concluded that “the city’s financial distress has directly negatively impacted Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) bond rating, making it more expensive for DWSD to borrow money to fund capital projects” (DWSD, Citation2014, p. 2). The report also emphasizes the benefits of potentially transitioning DWSD into a private authority that would effectively create “a more autonomous DWSD operational model that would be designed to provide a recurring revenue stream to the City of Detroit, enhance DWSD’s operational and legal independence from the City, and better ensure compliance through financial stability” (DWSD, Citation2014, p. 2).

The report outlines the dire financial situation of the water department, which caused two rounds of bond rating downgrades – a high risk of default for DWSD debt obligations – and the incurrence of additional indebtedness through interest rate swaps. For DWSD to resolve these issues, it ultimately led to higher costs of capital for DWSD and higher rates for its customers (DWSD, Citation2014, p. 1). The report further indicates “delinquencies” as an impediment to access the municipal credit markets that has contributed to DWSD’s incapacity to maintain upfront capital costs needed to invest in their ageing and deteriorating infrastructure, which became so dire that the city’s water and sewerage system was at a point of “non-functioning” (DWSD, Citation2014, p. 2).

As of 2014, DWSD’s credit rating was categorized as deep-junk status and had been significantly downgraded over the last several years since the financial crisis. According to Fitch Ratings, bonds issued on behalf of the DWSD were downgraded to below investment grade in 2014 due to “weak financial performance [and] believe economic improvement over the near term is unlikely given recent disclosure regarding the full scope of customer delinquencies” (Fitch Ratings, 2012).

In a time of low budgeting and economic stagnation in Detroit, finding new and innovative service provision strategies has provided a lexicon for urban austerity through a series of public–private partnerships, specifically transitioning the operation of public utilities from city departments into private authorities. While Detroit had been privatizing many of its services prior to their bankruptcy, new emergency manager laws, along with having the opportunity to enforce debt-cutting measures without local elected officials involved in the process, made privatizing vital services, such as water and sewerage, a strikingly attractive avenue to do so.

Private authorities can access the bond market with lower interest rates considering a private authority is viewed by credit agencies as a separate legal entity that is no longer associated with the City of Detroit, and rather it is a joint entity between its rate users and the governance structure of the private authority (GLWA, Citation2015, p. 15). As part of Detroit’s bankruptcy process to reduce municipal debt, core public services have been shifted to private authorities. This includes transitioning Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department into the Great Lakes Water Authority (Disclosure Statement, Citation2014, p. 114). City officials and financial consultants view this new governance arrangement as a reset button to improve services by giving more operational and management control to the suburbs in order to address the high number of delinquencies that were blamed on poor Black Detroiters (Phinney, Citation2018, p. 621).

According to We the People, a grassroots water justice organization “mass water shut offs in Detroit all goes back to who controls the infrastructure in the region during the bankruptcy, and how are we going to offload the debt we have so that it looks better in the eyes of the people who own our debt, i.e. the banks.”Footnote14 In this sense, the city was trying to prove to its creditors during the bankruptcy that they are “cracking down on people, they are getting tough” under this new public–private management structure as a way to get access to higher rated bonds.Footnote15

Policing the right to water in Black communities

A three-year contract to shut off water to Detroit residents was outsourced to a private demolition company called Homrich Wrecking Inc. The contract was first signed in 2013 for $5.6 million and has since increased to $12.7 million by emergency managers, and without city council approval (Cwiek, Citation2020). According to records, the contract involved a target of water shut offs to meet, where Homrich was required to continue at an average of 540 per week during non-winter months until 2017. In 2014, when the city experienced the highest numbers of water shut offs, overall collections increased $15 million to $310 million through aggressive extractive tactics used by Homrich (Kurth, Citation2016). From reports received from residents in their community work, Hydrate Detroit, revealed that in some instances if a household had been shut off and was found to be turned back on, Homrich Wrecking Inc, “would destroy the valve where you turn it back on and after, pour concrete over it. If that family then found money to pay their bills, they would have to pay someone to replace the entire water valve.” There were also stories of them just smashing and destroying the valve, rather than turning it off. There was no expectation by Homrich that water bills would be paid, or it would get turned back on again.Footnote16 Permanently cutting off water to households indicates the implausibility of households ever getting out of debt.

In an interview with Detroit News, Gary Brown, Director of Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department, acknowledged that “shut offs are now a fact of life.” Due to the severity, and difficulties of getting your water turned back on due to the high upfront debt payments DWSD requires, many residents began bypassing the water department and turning on their water “illegally.” Particularly in 2014, individuals organized themselves and began going neighborhood to neighborhood and turning back on households’ water that was disconnected because of unpaid bills.Footnote17 In order to deter this, the State of Michigan passed a law to change water service reconnections after being shut off from a civil infraction to a criminal offense (Carmody, Citation2019). As a result, many activists and residents have been fined, criminally charged, and jailed due to illegal access to water. Policing the right to water through criminalizing those who try to access it in Detroit is one example that shows the growing punitive environment that is embedded in austerity governance in majority-Black cities.

City of Baltimore: housing foreclosures via water debt

In the last several years, Baltimore has been very aggressive in handling delinquent water accounts. Water rates have more than quadrupled since 2000 (Food and Water Watch, Citation2018). Water bills are now unaffordable for about one-third of households in Baltimore (Food and Water Watch, Citation2015). Between 2008 and 2016, the City of Baltimore had over 82,000 water shut offs (FOIA request, 2019). At the time City Council President (who is serving as acting mayor as of May 2019) Bernard C. Young expressed support for water shut offs, claiming that “I like it better than taking people’s houses and putting them into foreclosure.” After receiving negative media press and pressure from water activist groups, the Department of Public Works stopped shutting off water in homes and instead, turned to foreclosing on homes to collect unpaid water bills. According to Mary Grant from Food and Water Watch, an activist group working to eradicate water poverty in Baltimore, “they city only knows how to collect water bills through punitive measures.”Footnote18 Under the renewed debt collection city policy, a homeowner could lose their house and its entire equity for an unpaid water bill for as a low as $750 (an increased from the previous amount of $350), and for an unpaid property tax bill for as low as $250. Every year in February, a “Final bill and Legal Notice” is sent to each property owner who has not been paying their water bills. In March, a list of properties with delinquent bills is then published in newspapers, the Baltimore Sun and the Daily Record. Moreover, they are also posted in the Baltimore City tax sale website at http://www.bidbaltimore (see ).

During the annual auction, properties are sold to the highest bidder if unpaid water bills have not been paid in full by the homeowner. Those who bid and win the right to a property at the action also now earn the right to charge interest and fees to homeowners seeking to redeem their properties, as well as the right to foreclose. To redeem their property: owners must pay their unpaid bills, plus 18% interest and hundreds (sometimes thousands) in court costs and legal fees to investors. For instance, a $500 water bill can climb to $3,000 two years after the tax sale when the lien on their home is bought by investors. The pay-out from the interest and fees goes to investors, not to the city. Moreover, investors who do not receive full repayment from the property owner can file a foreclosure. Baltimore’s interest rate on unpaid property taxes and water bill debt is among the highest in the State of Maryland. Hartford County for instance, has interest rates set at 12%. Even in Washington D.C, and New York – the interest rate is also at 12% that a tax lien investor can charge (Jacobson, Citation2015, p. 10). Moreover, in both Washington, D.C and New York, their laws prevent a property from going to tax sale for an unpaid water bill. Baltimore’s high-interest rate, along with legally allowed fees for lawyers have made it almost impossible for low-income, Black homeowners to redeem their properties. A homeowner with a lien that is sold at tax sale can pay as much as $1,500 in attorney fees on top of the lien plus 18% interest, as well as title searches up to $325, and court fees.Footnote19 In addition to the expensive costs, Amy Hennan, a lawyer that works for the Pro Bono Resource Center of Maryland, claims the city’s housing tax sale is a complicated process to navigate, and unfortunately many do not have the upfront costs to pay for a legal team, and end up losing their property because of not submitting the proper legal documents.Footnote20

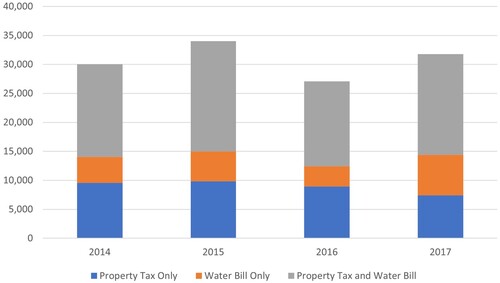

In 2017, nearly half of properties that entered Baltimore’s housing auction sale were for standalone unpaid water bills (meaning they were not behind on their property taxes, but only their water bills) (see ). The other properties consist of a combination between owed property tax and water bill debt.

Figure 4. Unpaid water bills that led to housing tax sale, 2014–2017.

Although the city has been auctioning properties for unpaid bills for decades, the practice has increased due to double-digit increases to water rates, and water shut offs no longer being used as a debt collection practice by the city’s water department. Baltimore County, where mostly the white, upper-class suburbs are located, does not include properties with unpaid water bills in the tax sale. This is due to the City of Baltimore owning the public water system that serves suburbs in Baltimore County. Although the city bills county property owners for water use, the city has no legal authority to put a lien on a property for an unpaid water bill – even if those bills are not paid. This means that suburban residents benefit from the investments in the city’s water and sewer infrastructure but do not have to deal with the costs of austerity measures, such as housing foreclosures, when they are unable to pay their bills. Since the city does not have jurisdictional authority in the suburbs as they are considered their own separate municipality, suburban residents are not at risk of losing their home for unpaid water bills in the same way they are in the City of Baltimore. Black homeowners are forced into foreclosure for an unpaid water bill and punished, yet white suburbanites are untouched and can retain their property and its equity.

Data from the Pro Bono Resource Center of Maryland shows that most homeowners who were at risk of losing their homes from unpaid water bills were overwhelming low-income, Black residents (80% in 2016 and 73% in 2017) with a household income under $30,000. Moreover, based on data of clients who visited tax prevention clinics organized by various lawyers, 78% of clients had delinquent water bills in 2016 and this rose to 86% in 2017 (Jacobson, Citation2015, p. 5). Baltimore’s debt collection practice of placing water liens on homes and selling the liens to investors is reported to have contributed significantly to the loss of Black homeownership in the city (Sullivan, Citation2020). The Black homeownership rate fell from 45% to 42% from 2007 to 2017. Though other racial groups have recovered from the massive foreclosures that hit the City of Baltimore since the economic crisis, the Black community has not seen the same rebound – and my findings indicate this is attributed to tax sale housing auctions (Sullivan, Citation2020).

When asked about the recent increasing numbers of houses that enter the tax auction each year due to water debt, a city official refers to the high capital expenditures to replace old water and sewerage infrastructure that needs to be matched by utility revenues through higher rates. Moreover, unlike some other water departments, the City of Baltimore does not have a collection agency in-house to collect on unpaid bills or the funds to use for third-party agencies. In other words, utilizing tax auctions is understood as the local governments’ only option at their disposable to collect on our water debt. Placing water debt on tax liens was a new local strategy that came into full effect beginning in 2007, but it wasn’t until 2014 that it became the central debt collection practice used for water and sewer bills by the Department of Public Works (NCLC, Citation2012). As a city official responded on the benefits for this debt collection process, “It is a very effective way of getting people to pay their bills and get revenue for the city.”Footnote21 This example speaks to the ways in which water departments have become reliant on user rates and fees to fund their operations and capital expenses and to meet debt obligations. As municipal and public debt is financialized and the funds to cover municipal expenditures is supplied by the financial market, over time, it has a de-democratizing effect where local governance works for the benefit of financial markets, rather than the public good. This resonates with work that suggests the state is “both object and agent of financialization” (O’Brien, O’Neill, & Pike, Citation2019: 6) and may mobilize financialization for the interests of private investors or what Aalbers (Citation2019) argues, to simply “get by” in a context of urban austerity and state-rescaling.

The spatialization of water and sewer debt collection lawsuits in St. Louis

In St. Louis, the practices of racial capitalism shaped Black areas through local labor and housing markets but also through physical infrastructure and public service provision, or lack thereof. In 1970 the US Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR) heard testimony from residents living in the St. Louis region on the racial implications of uneven development (USCCR, Citation1971, p. 3). Black residents testified that despite paying taxes their neighborhoods suffered from inadequate drinking water and lack of sewerage connection (USCCR, Citation1971, p. 304). According to Heck (Citation2021, p. 10), it was the poor provisioning of municipal services in St. Louis, such as water, that later codified redlined neighborhoods as blighted and targeted these areas for federal urban renewal programs. Historical forms of racial oppression embedded in the built environment have shaped contemporary water insecurity in the region for Black communities.

From 2014 to 2019, the City of St. Louis had over 100,000 water shut offs (FOIA requests, 2019). This means approximately 1 out of 6 St. Louis residents had their water shut off during this period.Footnote22 Alongside water shut offs, the City of St. Louis uses additional local policy measures, such as court orders through garnishing assets and wages from people. This is done using third-party debt collectors to collect unpaid water and sewer debt. A garnishment is a legal order directing a third party to seize assets, usually wages from employment or money in a bank account, to settle an unpaid debt (Kagan, Citation2019). Water shut offs are harmful, but a Missouri state official, claims what is just as harmful is the collection process thereafter that allows St. Louis’ water and sewerage utilities to take a person’s assets and garnish wages for unpaid water and sewer bills through a judicial process.Footnote23 In St. Louis, over 100,000 judgments were passed down in debt collection lawsuits from 2008 to 2012. Between 2008 and 2012, debt collectors seized an estimated $34 million from residents in mostly black neighborhoods in the St. Louis area (Constantineau, Citation2017, p. 487). The majority of this was wages lost through garnishments. This financial strain through punitive debt collection drives families even further into debt because they seek out new loans to repay the initial debts.

The Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District (MSD) provides service to the city of St. Louis and its surrounding suburban counties. In 2012, St. Louis signed a consent decree agreement with the EPA (Trickey, Citation2017). It is a $4.7 billion project, named Project Clear, over a span of 20 years to cut down on sewer and stormwater overflow. As a result of having to issue billions of dollars in revenue bonds to pay for infrastructure to fix their combined sewer overflow system, sewer rates have tripled since 2005 (MSD, Citation2020). Over the last 10 years, MSD used some speculative financial arrangements to fund sewer infrastructure development through advance refunding revenue bonds in the municipal bond market. In 2010, MSD decided they had too many delinquent bills and so they increased their collection efforts by using third-party debt collectors and filing lawsuits against residents who owed debt from their sewer bills. MSD went from filing 3,000 suits in 2010 for unpaid bills to 11,000 in 2012 (Kiel & Waldman, Citation2015). In 2012, MSD filed more suits for debt collection efforts than any other company in Missouri.

Through data obtained by Pro Publica, MSD judgements were in overwhelming filed against residents in Black communities in St. Louis, even though most of MSD’s customers are from the suburban, mostly white counties. It found that debtors who owed money to MSD in majority-black communities are more than twice as likely as income-equivalent debtors living in majority-white neighborhoods to have debt collectors attempt to recover delinquent debts through legal action. Additionally, MSD obtained judgements where they could garnish wages and charge interest fees on unpaid debt in mostly Black neighborhoods at a rate of about four times than in majority white ones (Kiel & Waldman, Citation2015).

Under Missouri law, a judgment-creditor may legally garnish 25% of a debtor’s disposable income (Thompson, Citation2019). Moreover, the Missouri Revised Statutes state that a creditor can charge additional annual interest rates between 9-20% for unpaid bills if the judgement favors the creditor. Therefore, water and sewer debts that originated in the hundreds of dollars can quickly “balloon” to tens of thousands of dollars.

When MSD sues, the debts can be quite small, even as little as $350. Although this is only a small amount – many residents are unable to navigate the judicial process and cannot afford legal counsel to fight the sewer department’s lawsuit. In St. Louis, defendants had counsel in less than 8% of debt collection cases filed between 2008 and 2012. And in lower-income black neighborhoods, just 4% had a lawyer (Constantineau, Citation2017, p. 492). This is in part due to this being a civil court case, in which there is no right to a public defender. Lance LeComb, who is the public relations official for MSD, said the utility is trying to work with delinquent customers who are behind on their bills, but that MSD has a duty to pursue owed debt to the full. When asked about the utility’s debt collection methods, MSD Financial Officer Marion Gee, stated that unfortunately just like any other service or product, “MSD has to be aggressive in order to function and to raise revenue” and to primarily be able to pay for bonds for infrastructure improvements.Footnote24

Judgments from MSD lawsuits are concentrated in areas of St. Louis that are majority black, revealing an aspect of racial disparity in the debt-collection process in lower-income St. Louis communities. This debt regime operates not only through categorizing and targeting certain racialized subjects for debt collection of owed sewer bills – but it also involves extracting value by operating through racially segregated neighborhoods across the St. Louis region to function. In this way, residents from Black communities are spatially exposed to debt predation and are disposable populations, where their owed debt and the fees attached have become a target for revenue extraction.

In the City of St. Louis – and other Black-majority municipalities in the region – between 25 and 35% of local revenue comes from municipal fines and fees. Whereas middle-class, white communities in St. Louis County, such as Kirkwood and Ladue, draw only about 5–10% of their revenue from this (Gordon, Citation2015, p. 60). The criminalization of debt, as understood through fines and fees, is all too familiar for Black communities in St. Louis. During the 2008 Great Recession, city managers from St. Louis and other surrounding Black-majority municipalities, such as Ferguson, pressured courts, and the police department to increase the cost and collection of fines and fees to close the municipal budget gap created by declining sales and property tax receipts (US DOJ, Citation2015). Under this local system, residents can spend years, even decades, in a jail (called “the workhouse”) if they cannot afford to pay traffic fines, such as a speeding ticket, or technical violations, such as having an unmowed lawn or jaywalking (Sharma & Randall, Citation2020). It has been referred to as a modern-day “debtors’ jail” by activists interviewed from ArchCity Defenders where St. Louis functions through “an arrest and incarcerate model” to deal with poverty, and this includes those with unpaid water and sewer bills.Footnote25 At the same time, the proliferation of variegated municipal debt collection practices for unpaid water and sewer bills, as is the case with wage garnishments in St. Louis, is that municipalities are redrawing local strategies to facilitate the needs and wishes of bondholders, as Ashton and Christophers (Citation2015) mention, to find ways to facilitate the transformation of urban products (i.e. water and sewer services) as financial assets.

Conclusion

This paper examines the contemporary juncture of austerity policies and the financialization of water and sewer infrastructure that has created a wave of water insecurity crises across cities. Widespread water shut offs in cities like Detroit in which United Nations was called in to observe the situation illuminate the extreme forms austerity prevailing following 2008. Catarina de Albuquerque, the UN Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, said the City of Detroit was violating human rights by shutting off water to those who can’t pay their bills at an “unprecedent scale,” which disproportionately affected poor African Americans (Kwesell, Citation2014).

In Black-majority cities, these water crises have been the product of local state “solutions” governing in a fiscally distressed environment over the last decade in which they have been unable to economically recover. These “solutions” have served to keep residents paying and revenue flowing to not risk financial troubles for local governments in a time of recession. Local officials’ decisions to use municipal fines and fees through debt collection practices reveal the unequal position Black-majority cities are placed in the municipal bond market. How debt is collected in a city is a key element used to provide credit ratings to municipal governments. Governments with higher amounts of debt as a percentage of their revenue receive lower ratings according to this criterion, but as shown through this paper, this is also dependent on racialized and punitive methods of debt collection. This is racialized using specific inputs through their poor creditworthiness which signifies a degree of expendability in the financial sector and the ways in which urban governance, as Aalbers (Citation2019, p. 596) argues, can be captured by finance and at the same time, municipalities can use and invite finance to achieve their objectives. The racialization of municipal finance has created differentiated opportunities and threats for local governments of Black-majority cities that have been examined. Consequently, this has meant these local governments rely more on speculative borrowing tools to finance infrastructure and have had to structurally adjust towards utilizing debt collection practices to manage debt obligations. As the financialization literature suggests, more commonly investors are the ones increasingly “calling the shots” to restructure urban plans to favor their financial interests (Kaika & Ruggiero, Citation2016; Waldron, Citation2019). As outlined, resident debt collection has become institutionalized in the bond lending process to make up for revenue shortages to be able to meet debt needs and to favor bondholders’ interests. These debt collection practices make it so that poor Back residents are the ones subsidizing the accumulation process, compensating for revenue gaps created by financialization and debt incurred by municipalities to appease investors. Debt is one of the few mechanisms that Black-majority municipalities have for attempting to manage financial crises. Moreover, as was shown, debt can be relative and is evaluated differently based on creditworthiness. Aggressive debt collection techniques to pay for water and sewer infrastructure have now become institutionalized in the bond rating process for cities to access credit. In this way, the municipal bond market plays a decisive role in regulating the right to water across US cities.

Municipal water debt collection through water shut offs, housing foreclosures, and garnishing wages through court orders is framed as a mechanism for enabling better ratings in the bond market, less costly debt terms, and low financial risk, but it is structured through existing racialized geographies of inequality. Detroit for instance, used more harsher methods in the form of charging higher interest fees for unpaid debt and applying criminal offenses for those who illegally turn on their water in comparison to St. Louis, who are using legal avenues to deduct wages for unpaid bills. All these case studies show similarities in terms of the financialization and commodification of water and sewer services and the imperative to use some method of debt collection to be able to access better credit ratings from the municipal bond market. These practices serve as requirements to access the bond market throughout different stages of issuing bonds and are increasingly asked about and of importance to municipal bond investors according to my findings with experts in the field. Illustrating how city credit ratings function as a tool perpetuating racial inequality generates important theoretical and empirical takeaways for the study of race in geography.

Nationally, more federal funding programs are needed to ease high water debt burdens and to redistribute costs through a more progressive funding streams where cities are not solely dependent on the bond market to fund water and sewer infrastructure improvements. Increased federal funding can also assist low income-families with water and sewer bills. For example, the federal government could expand the current Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which is a federal block grant program that provides states with funds to assist low-income households with expenses for heating and cooling, as well as energy crisis interventions and weatherization (Montag, Citation2019, p. 72). Families are eligible for assistance if their incomes are at or below 150% of the federal poverty line or 60% of the state median. Most LIHEAP funds are used to help families pay for heating assistance, and funds currently cannot be used for water or sewer bills. An expanded program could help mitigate and household water insecurity the battle for affordable water.

This paper calls for further engagement with critical geographies of race/racialization to advise urban and economic geography scholarship on urban governance to better understand the connections between long-term capital flight and racial capitalism that are redefining how Black-majority cities are responding to fiscal crises. Conceptually, by drawing together Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis, I highlight the need for fine-grained, comparative analyses of racial capitalism in Black-majority cities to better understand the relational geographies of urban financialization, associated patterns of local state-restructuring, and how these processes are “lived out” in cities.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of interviewees for this research, especially to the organizers, activists and families that welcomed me in Detroit, St. Louis, and Baltimore. A sincere thank you to Dr. Cristina Temenos, Professor Kevin Ward, Dr. Nate Millington, and Dr. Desiree Fields for their input and guidance during subsequent drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Baltimore Local Government Interview, March 2019.

2 Water and Sewer Financial Consultant Interview, June 2019.

3 Water utility goverment official Interview, March 2019.

4 Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District Interview, January 2019.

5 Water Utility Financial Expert Interview June 2019, Water Utility Goverment Official Interview March 2019.

6 Detriot City Government Interview, May 2019.

7 Great Lakes Water Authority Interview, June 2019.

8 St. Louis Water Department Interview, February 2019.

9 State of Michigan Water Division Interview, June 2019.

10 FOIA request in March 2019, water shut off data sent November 2019.

11 Detriot Bankruptcy Lawyer, May 2019.

12 Detroit Community Organizer Interview, May 2019; Detriot City Government Interview, 2019.

13 Water Utility Financial Consultant Interview, June 2019.

14 We the People Interview, June 2019.

15 We the People Interview, June 2019.

16 We the People Interview, June 2019.

17 Hydrate Detroit Interview, June 2019.

18 Mary Grant Interview, Community Organizer, April 2019.

19 Abell Foundation Interview, April 2019.

20 Utility Lawyer Interview, April 2019.

21 City of Baltimore Official Interview , April 2019.

22 This is not an exact number, but an approximation of total shut offs as the data received could include multiple shut offs for some residents.

23 State of Missouri Interview, June 2019.

24 Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District Interview Feb 2018.

25 St. Louis Community Organizer Interview, February 2019.

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2019). Financial geography III: The financialization of the city. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853922

- Allen, J., & Pryke, M. (2013). Financialising household water: Thames water, MEIF, and ‘ring-fenced’ politics. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6(3), 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rst010

- Ashton, P., & Christophers, B. (2015). On arbitration, arbitrage and arbitrariness in financial markets and their governance: Unpacking LIBOR and the LIBOR scandal. Economy and Society, 44(2), 188–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013352

- Ashton, P., Doussard, M., & Weber, R. (2016). Reconstituting the state: City powers and exposures in Chicago’s infrastructure. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1384–1400.

- Baptist, E. E. (2014). The half has never been told: Slavery and the making of American capitalism. Hachette UK.

- Bhattacharyya, G. (2018). Rethinking racial capitalism. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bigger, P., & Millington, N. (2020). Getting soaked? Climate crisis, adaptation finance, and racialized austerity. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 3(3), 601–623. http://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619876539

- Bledsoe, A., & Wright, W. J. (2019). The anti-blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818805102

- Bonds, A. (2018). Refusing resilience: The racialization of risk and resilience. Urban Geography, 29(8), 1285–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1462968

- Carmody, S. (2014). UN team says Detroit water shutoff program violates human rights. Michigan Radio. https://www.michiganradio.org/post/un-team-says-detroit-water-shutoff-program-violates-human-rights

- Carmody, S. (2019). Michigan lawmaker proposes lessening penalty for reconnecting shut-off water service. Michigan Radio. Web. https://www.michiganradio.org/post/michigan-lawmaker-proposes-lessening-penalty-reconnecting-shut-water-service

- Constantineau, A. (2017). Fair For whom? Why Debt-Collection Lawsuits in St. Louis Violate the Procedural Due Process Rights of Low-Income Communities. American University Law Review, 66(2), 479–538. http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol66/iss2/

- Cwiek, S. (2020). Civil rights groups sue Detroit over water shutoffs. Michigan Radio. Retrieved May 15, 2021, from https://www.michiganradio.org/term/detroit-water-shutoffs

- Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD). (2014, August 14). Memorandum of understanding: Regarding the formation of the Great Lakes Water Authority. Detroit, MI: City of Detroit, Web.

- Disclosure Statement. (2014, February 21). U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Michigan (pp. 1–440). Doc 2709.

- Farmer, S. (2014). Cities as risk managers: The impact of Chicago’s parking meter P3 on municipal governance and transportation planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(9), 2160–2174. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130048p

- FFGC. (2020, June 3). George Floyd, police violence, and our work. Fines & Fees Justice Center. https://finesandfeesjusticecenter.org/2020/06/03/george-floyd-police-violence-and-our-work/

- Fields, D. (2017). Unwilling Subjects of Financialization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijur.12519

- Fitch Ratings. (2012, October 9). Fitch rates Philadelphia’s water, sewer rev ‘A+.’ Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSWNA712320121009

- Food and Water Watch. (2015, April 23). One-third of Baltimore residents can't afford ever-increasing water rates. https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/news/one-third-baltimore-residents-cant-afford-ever-increasing-water-rates

- Food and Water Watch. (2018). America’s secret water crisis: National Shutoff survey reveal water affordability emergency affecting million (pp. 1–17).

- Furlong, K. (2019). Geographies of infrastructure I: Economies. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519850913

- Furlong, K. (2020). Trickle-down debt: Infrastructure, development, and financialisation, Medellín 1960–2013. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(2), 406–419. http://doi.org/10.1111/tran.v45.2

- Gilmore, R. (2002). Fatal couplings of power and difference: Notes on racism and geography. Professional Geographer, 54(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00310

- Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. Berkeley and Los Angeles. University of California Press.

- Gordon, C. (2015). Segregation and uneven development in greater St. Louis, St. Louis County, and the Ferguson-Florissant School District. Expert Report submitted on behalf of plaintiffs in Missouri State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. https://clas.uiowa.edu/history/sites/clas.uiowa.edu.history/files/Gordon%20FF%20Report%20Final%20Signed%20w%20Exhs.pdf

- Great Lakes Water Authority (GLWA). (2015). Regional Sewage Disposal System Lease Agreement (pp. 1–30). 2015 [Detroit] City of Detroit. Web. February 13, 2016.

- Hackworth, J. (2007). The neoliberal city: Governance, ideology, and development in American urbanism. Cornell University Press.

- Heck, S. (2021). Greening the color line: Historicizing water infrastructure redevelopment and environmental justice in the St. Louis metropolitan region. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 0(0), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1888702

- Hendrikse, R. P., & Sidaway, J. D. (2014). Financial wizardry and the golden city: Tracking the financial crisis through pforzheim, Germany. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12024

- Jacobson, J (2015). The steep price of paying to stay: Baltimore City’s tax sale, the risks to vulnerable homeowners, and strategies to improve the process (pp. 1–39).

- Jenkins, D. (2020). Debt and the Underdevelopment of Black America. Roundtable 3: Race and Money. Retrieved January 12, 2021, from https://justmoney.org/d-jenkins-debt-and-the-underdevelopment-of-black-america/

- Jenkins, D. (2021). The bonds of inequality: Debt and the making of an American city. University of Chicago Press.

- Johnson W. (Ed.). (2017). Race, capitalism, justice forum 1. Boston Review. https://bostonreview.net/forum-i

- Kagan, J (2019) Garnishment. Investopedia, Retrieved September 29, 2019, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/garnishment.asp

- Kaika, M., & Ruggiero, L. (2016). Land financialization as a ‘lived’ process: The transformation of Milan’s Bicocca by Pirelli. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413484166

- Kelley, R. D. G. (2017). ‘What is Racial Capitalism and Why Does It Matter?’, recorded at the Kane Hall, University of Washington, Seattle, WA – Video.

- Kiel, P., & Waldman, A. (2015). The burden of debt on Black America. The Atlantic. Web. Retrieved October 9, 2015, from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/10/debt-black-families/409756/

- Kurth, J. (2016). Contract for Detroit water shut offs doubles in one year. Detroit News. Web. Retrieved 14 October 14, 2016, from https://eu.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2016/10/13/contract-detroit-water-shutoffs-doubles-one-year/92031538/

- Kwesell, A. (2014). In Detroit, city-backed water shut-offs ‘contrary to human rights,’ say UN experts. UN News. Web. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2014/10/481542-detroit-city-backed-water-shut-offs-contrary-human-rights-say-un-experts

- Lakhani, N. (2020). Revealed: millions of Americans can’t afford water as bills rise 80% in a decade. The Guardian. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/23/millions-of-americans-cant-afford-water-bills-rise?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

- Lowe, L. (2015). The intimacies of four continents. Duke University Press.

- McIntyre, M., & Nast, H. J. (2011). Bio(necro)polis: Marx, surplus populations, and the spatial dialectics of reproduction and “Race”1. Antipode, 43(5), 1465–1488. http://doi.org/10.1111/anti.2011.43.issue-5

- Melamed, J. (2015). Racial capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076

- Melosi, M. (2000). The sanitary city: Urban infrastructure in America from colonial times to the present. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District (MSD). (2020). MSD consent decree. Retrieved from https://portal.laserfiche.com/Portal/DocView.aspx?id=2193043&repo=r-a96260ce

- Montag, C. (2019). Water/color: A study of race & the water affordability crisis in America’s Cities. In A report by Thurgood Marshall Institute NAACP (pp. 1–100).

- Moody’s. (2014). US Municipal Utility Revenue Debt. Web. https://www.amwa.net/sites/default/files/moodys-rfc-municipalutilitybonds.pdf

- National Consumer Law Center (NCLC). (2012, July). The other foreclosure crisis: Property tax liens sales. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/foreclosure_mortgage/tax_issues/tax-lien-sales-report.pdf

- Norris, D. (2021). Embedding racism: City government credit ratings and the institutionalization of race in markets. Social Problems, spab066, 1–21.

- O’Brien, P., O’Neill, P., & Pike, A. (2019). Funding, financing and governing urban infrastructures. Urban Studies, 56(7), 1291–1303. http://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018824014

- Omstedt, M. (2019). Reading risk: The practices, limits and politics of municipal bond eating. Environment and Planning A, 53(3), 611–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19880903

- Paudyn, B. (2014). Credit ratings and sovereign debt: The political economy of creditworthiness through risk and uncertainty. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Phinney, S. (2018). Detroit’s municipal bankruptcy: Racialised geographies of austerity. New Political Economy, 23(5), 5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1417371

- Ponder, C. S. (2017). The life and debt of Great American Cities: Urban reproduction in the time of financialization [Doctoral thesis]. The University of British Colombia.

- Ponder, C. S. (2018). The difference a crisis makes: Environmental demands and disciplinary governance in the age of austerity. In M. Davidson & K. Ward (Eds.), Cities Under Austerity: Restructuring the US Metropolis. SUNY: Albany. SUNY.

- Ponder, C. S. (2021). Spatializing the municipal bond market: Urban resilience under racial capitalism. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1866487

- Ponder, C. S., & Omstedt, M. (2019). The violence of municipal debt: From interest rate swaps to racialized harm in the Detroit water crisis. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 132,1–10.

- Pulido, L. (2016). Flint, environmental racism, and racial capitalism. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 27(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013

- Ranganathan, M. (2016). Thinking with flint: Racial liberalism and the roots of an American water tragedy. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(3), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1206583

- Robertson, S. (2019). $2.6M in garbage fees owed by residents. Natchez Democrat. Retrieved October 22, 2019, from https://www.natchezdemocrat.com/2019/10/22/2-6m-in-garbage-fees-owed-by-residents/

- Robinson, C. (2000). Black Marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. University of North Carolina Press.

- Rosenman, E. (2019). Capital and conscience: Poverty management and the financialization of good intentions in the San Francisco Bay area. Urban Geography, 40(8), 1124–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1557465

- Safransky, S. (2014). Greening the urban frontier: Race, property, and resettlement in Detroit. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 56, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.003

- Seamster, L. (2019). Black debt, white debt. Contexts, 18(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504219830674

- Seamster, L., & Purifoy, D. (2021). What is environmental racism for? Place-based harm and relational development. Environmental Sociology, 7(2), 110–121. http://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2020.1790331

- Sharma, M., & Randall, C. (2020). St. Louis’s shameful workhouse jail must be shut down. Jacobin. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://jacobinmag.com/2020/07/close-workhouse-st-louis-missouri-board-bill-92-lewis-reed

- Sinclair, T. J. (2005). The New masters of capital: American bond rating agencies and the politics of creditworthiness. Cornell University Press.

- Singla, A., Kirschner, C., & Stone, S. B. (2020). Race. Representation, and revenue: Reliance on fines and forfeitures in city governments. Urban Affairs Review, 56(4), 1132–1167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419834632

- State of Michigan. (2013). Financial recommendation letter. Retrieved March 1, 2013, from https://www.michigan.gov/documents/treasury/Detroit-Determination-Letter-March-1-2013_415660_7.pdf

- Sugrue, T. J. (2014). The origins of the urban crisis: Race and inequality in postwar Detroit. Princeton University Press.

- Sullivan, E. (2020). Activists Plead Scott to follow promise to remove homeowners from tax sale, April £0, 2021. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.wypr.org/wypr-news/2021-04-30/activists-plead-scott-to-follow-promise-to-remove-some-homeownersfrom-tax-sale

- Thompson, R. (2019). State Wage Garnishment Laws. Web. Retrieved April 11, 2019, from https://www.fair-debt-collection.com/defend-debt-lawsuits-and-fight-wage-garnishment/state-wage-garnishment-laws.html

- Trickey, E. (2017, Apr 20). How a sewer will save St. Louis. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/04/20/st-louis-infrastructure-sewer-tunnelwater-system-215056s

- United States Commission on Civil Rights. (1971). Hearing before the United States Commission on Civil Rights. Hearing held in St. Louis, Missouri, January 14–17, 1970. U.S. Govt. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102144931

- US Department of Justice. (2015). Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department. Web. Retrieved March 4, 2015, from https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_police_department_report.pdf

- Waldron, R. (2019). Financialization, urban governance and the planning system: Utilizing ‘development viability’ as a policy narrative for the liberalization of Ireland’s post-crash planning system. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(4), 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12789

- Wang, J. (2018). Carceral capitalism. MIT Press.

- Weber, R. (2010). Selling city futures. Economic Geography, 86(3), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01077.x

- Whitfield, D. (2016). The financial commodification of public infrastructure [Research Report No. 8]. European Services Strategy Unit.