ABSTRACT

The majority of the province of Saskatchewan’s craft breweries are housed in the two largest cities, Saskatoon and Regina. Current planning practices in both cities direct breweries to limited geographies in central established areas. I argue that the extent to which craft breweries play a role in processes of gentrification in mid-sized cities is directly tied to planning practices which regulate the geography of craft beer. In order to assess the potential for gentrification, I focus on neolocalism and third places, two consumption practices which shift the image and identity of a space, and which are intertwined with processes of urban change. Drawing together an analysis of community plans, zoning bylaws, local media, site observation, and brewery websites, I demonstrate how in the case of Saskatoon and Regina, strategic planning approaches aimed at increasing intensification in the central areas, coupled with regulations directing breweries into limited zones, has positioned craft breweries as agents of urban change. The findings suggest that craft breweries that display strong neolocal practices and develop third places are the most likely to trigger/extend gentrification. These breweries are typically located in close proximity to residential zones with consumption as a primary focus (taprooms, tasting rooms, in-house restaurants).

Introduction

Over the past decade, Canada’s beer industry has experienced rapid growth, rising from 242 breweries in 2012 to 1210 in 2020 (Beer Canada, Citation2021). According to the latest industry trends, “craft breweries” make up most of the industry, defined by the Canadian Craft Brewers Association as small, independently owned, and operated sites which “embody a culture shaped by a belief in authenticity, community and environmental responsibility” and which “reinvest in their communities and in many cases revitalize them” (CCBA, Citation2021). The “craft” nomenclature is utilized by small-scale breweries to highlight specialized production which carries cultural and social capital. The term is used to differentiate this class of breweries (small-scale output with independent ownership models) from national and transnational industrial breweries. As small-scale locally situated breweries gained market share in Canada, industrial breweries acquired these smaller operations to offset capital losses, a process whereby ownership of these smaller breweries changed, but the product and labeling remained (Eberts, Citation2014). This presents difficulties for consumers to differentiate between small-scale breweries that are owned by a large corporation and small-scale independent breweries as both may carry the “craft” nomenclature. I use the term “craft brewery” in this research to refer to small-scale independent breweries (microbreweries, nanobreweries, and brewpubs), with the understanding that the term “craft” is complicated and that not all small-scale beer producers adopt this nomenclature.

Building upon research linking craft breweries with gentrification processes in large metropolitan areas (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014; Walker & Fox Miller, Citation2019; Weiler, Citation2000), in this paper, I examine the role of craft breweries to effect urban change in two mid-sized peripheral cities on the Canadian prairies, Saskatoon and Regina. Despite the distribution of craft breweries across the urban hierarchy, the influence of this sector in peripheral sites is currently underdeveloped. The questions guiding this research are: (a) what role do craft breweries play in processes of gentrification in peripheral locations? and (b) how does urban planning influence the relationship between gentrification and craft beer?

Urban researchers demonstrate how craft breweries can trigger gentrification (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014; Weiler, Citation2000) or deepen the process already at play (Walker & Fox Miller, Citation2019). On the latter, craft breweries “may not be catalysts of urban revitalization so much as respondents to changing neighborhood demographics” (Barajas et al., Citation2017, p. 2). Gentrification is defined as a process of upgrading and reinvestment that causes displacement and/or turnover by middle to upper-class users/uses. There are numerous examples of craft breweries being utilized in redevelopment processes during the first wave of tenancy (Canadian examples include Vancouver’s Granville Island, Toronto’s Distillery District, and Ottawa’s Lebreton Flats) to develop a unique place identity (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014). By rejecting mass production in favor of locally situated, small-scale production processes premised on distinction, craft breweries develop new spaces for cultural consumption (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014). The presence of the breweries attracts interest (and an upscale consumer base) spurring additional investment in a process now dubbed “beer-oriented development” (Hawley, Citation2015).

The potential for craft breweries to contribute to gentrification is defined, in part, by urban planning. Urban planning practices direct the geography of craft beer, marking out where these manufacturers are permitted/discretionary/prohibited. The relationship between urban planning and craft beer is largely underdeveloped in the literature (see as an exception Barajas et al., Citation2017; Nilsson et al., Citation2018) despite the role that this process plays in guiding the location of craft beer production/consumption. As Nilsson et al. (Citation2018) highlight, “traditionally … breweries have been defined as alcoholic manufacturers and therefore restricted to light and heavy industrial districts away from residential neighbourhoods” (p. 117). This has led many cities in the United States to implement changes to their zoning regulations to encourage craft breweries to locate within their limits, recognizing the potential of the industry to create vitality and interest (Barajas et al., Citation2017; Nilsson et al., Citation2018; Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017a). Zoning regulations are also beginning to shift in the Canadian context (expanding into mixed use and commercial zones) to account for the scale, nature, and contributions of craft breweries. While research to date has focused on the location of craft breweries alongside built form (Flack, Citation1997; Reid, Citation2018; Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017b), it has not interrogated why these locations are taken up by craft breweries as a product of zoning regulations and overall urban planning approaches (Barajas et al., Citation2017). Ultimately, craft breweries are directed by a set of legal parameters (e.g. zoning, official community plans) that set out where this form of manufacturing is permissible.

In the case of Saskatoon and Regina, planning practice has limited the location options for craft breweries to industrial and (more recently) commercial zones in centralized areas. The regulations have resulted in a concentration of breweries in both municipalities, aligned with strategies to repopulate central areas through intensification planning. As a response to decentralization trends from the twentieth century (e.g. low density, automobile dependent, single use suburban development), municipalities across Canada have emphasized intensification as a key planning strategy (e.g. mixed use, centralized, compact development) to direct growth to central established areas (Filion et al., Citation2010; Graham et al., Citation2019). Intensification planning in Saskatoon and Regina directs growth inward to central areas, but operates without limitations set for outward growth, despite significant peripheral and exurban expansion (Graham, Citation2018). As a result, both cities have failed to meet intensification targets that seek to create vitality and complete communities in central areas. The combination of intensification planning and zoning regulations has positioned craft breweries in both cities as potential agents for urban change.

In the remainder of the paper, I engage with the relationship between craft breweries, gentrification, and urban planning. First, in order to analyze the extent to which craft breweries may catalyze/deepen gentrification, I draw on the practices of neolocalism and third places. The literature review lays out the effects of these practices on urban spaces and their association with gentrification through the lens of craft beer. Next, I lay out the methodology guiding the research and the urban planning context for Saskatoon and Regina. Lastly, I analyze the potential association between craft breweries and gentrification across multiple planning zones and building sites in the two mid-sized cities.

Neolocalism, third places & gentrification

To interrogate the potential for craft breweries to become intertwined with gentrification processes, I focus on two consumption practices representative of the craft beer industry: neolocalism and third places. Neolocalism reflects a celebration of local production and connections to place (e.g. history, location, features), while third places create sites for gathering and exchange between the first place (home) and the second place (work) (Oldenburg, Citation1989). Both practices contribute to placemaking and provide craft breweries with a particular aesthetic and status (Apardian & Reid, Citation2020). It is important to note that the degree to which craft breweries establish connections with the local varies, and that not all craft breweries participate in the practice of neolocalism. Similarly, not all craft breweries create spaces for exchange, as some focus instead on production output. These two consumptive practices, while varying in their extent within the sector, provide useful markers of gentrification. The craft beer sector has the capacity to shift the image of an urban site, and to “provide craft beer drinkers with a sense of urban cultural identity and a sense of place and belonging” (Schroeder, Citation2020, p. 218). The ability for breweries to reimage place and to establish belonging (through an emphasis on the “local”) positions them as an active force within processes of gentrification.

The concept of “neolocalism” refers to the shift in consumer demand towards place-based offerings (Flack, Citation1997), and the extent to which the “local” is packaged into consumer products (Mclaughlin et al., Citation2014; Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017b). Neolocalism establishes strong connections to place, including the revival of traditions and values that may have eroded under global economies (Parnwell, Citation2007). As Eberts (Citation2014) highlights, craft breweries typically celebrate the local and place as part of their brand. As small, locally owned, independent enterprises, craft breweries contribute directly to the development of a “sense of place” through local attributes (Fletchall, Citation2016; Schnell & Reese, Citation2003; Wolf-Powers et al., Citation2017). This includes the incorporation of local beer varieties and locally sourced ingredients into production processes (Patterson & Hoalst-Pullen, Citation2014). Craft breweries also develop place attachment through the use of location names, local sites, historic events and/or other place features into the brewery name, beer labels, and the interior aesthetic (Eberts, Citation2014; Holtkamp et al., Citation2016; Myles & Breen, Citation2018; Schnell & Reese, Citation2003). As such, craft breweries are “promoted and consumed as part of place” (Schroeder, Citation2020, p. 218) and are a “very effective form of place-making” (Fletchall, Citation2016, p. 540) given the connections to the local (e.g. imagery, naming) and the experiential nature of the activity itself (e.g. imbibing in the brewery). In short, neolocalism is used by craft breweries to attach value and identity to a commodity as part of the marketing process (Ikäheimo, Citation2021).

The focus on the “local” gives breweries adopting neolocalism a sense of “authenticity” as a mode of consumer distinction. By consuming locally produced craft beer, consumers are rejecting globalizing forces (Schnell & Reese, Citation2003). The emphasis on what is locally available supports development (Everett & Aitchison, Citation2008; Pena et al., Citation2012) and attracts tourists (Eades et al., Citation2017; Murray & Kline, Citation2015; Plummer et al., Citation2005; Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017a). The return to traditional techniques and recipes, as well as the shift towards small-scale production, translates into a cultural experience (Plummer et al., Citation2005). Moreover, the creation of brewery districts fosters the potential for ale trails or passports to encourage consumption and to create a sense of place (Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017a). The placemaking potential of craft breweries is not limited to a particular geographic scale. As Eberts (Citation2007, Citation2014) demonstrates, craft breweries develop an identity that is highly correlated with the unique qualities of place regardless of population size. This place-based identity is imbued within the product and the brewery space which hold symbolic capital and prestige for consumers (Baginski & Bell, Citation2011; Mathews & Picton, Citation2014; Murray & O’neill, Citation2012).

Neolocalism in the food and beverage industry is associated with an upscale clientele and gentrification (Buratti, Citation2019). As an artisanal good, craft beer is aligned with prestige (Murray & O’neill, Citation2012; Slocum, Citation2016) and craft beer consumers are described as educated, sophisticated and affluent purveyors of taste (Feeney, Citation2015; Mathews & Picton, Citation2014). Moreover, the characterization of the typical craft beer producer and consumer as white and male highlights how the industry struggles with diversity (Chapman et al., Citation2018). In smaller centers, widespread support of local breweries by a diverse cross-section of residents complicates understandings of beer products as holding the same signifiers of taste, prestige and symbolic capital that is typical in metropolitan centers (Baginski & Bell, Citation2011). Putting aside the discrepancies surrounding craft beer consumers, the popularity of these sites as social spaces creates urban vitality, often in areas that are unexpected.

Craft breweries occupy a range of building types, with a preference for transforming existing buildings to take advantage of locational benefits (e.g. accessibility and centrality) and lower land costs (Reid, Citation2018). The use of “marginal properties” allows breweries to “leverage comparatively low rents to make profitable the production of a value-added product” (Myles & Breen, Citation2018, p. 166). Because craft breweries aren’t reliant on cutting edge technology infrastructure, they have greater flexibility and choice of building types and locations.

Substantive start-up costs associated with the industry (e.g. specialized equipment, structural accommodations) pushes craft breweries into devalorized areas (Walker & Fox Miller, Citation2019). While early research on the industry focused on the renovation of historic buildings as a conceptual fit (Flack, Citation1997), this formula has expanded beyond historic buildings and craft breweries are increasingly occupying, and transforming, a range of building types (Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017b). Craft breweries recognize the value of place and benefit from any changes that might follow their presence in a place (Myles et al., Citation2020).

The ability for craft breweries to function as third places is, in part, dependent on where they are permitted/discretionary/prohibited within the urban planning process. The physical site of the brewery affects how consumers may engage the “local” and what type of interaction and exchange (if desired by the brewery) is possible. Oldenburg (Citation1989) argued that people need to have a place to mediate between the individual and society which affords a level of social interaction. Ideally, these places are true public spaces, without barriers to entry, but at a time when true public spaces are in decline, third places take on a broader meaning. Rojak and Cole (Citation2016) document the important role that craft breweries play in establishing third places in their communities as meeting places and their ability to foster attachments to place. At the same time, by catering to a particular demographic of consumers (e.g. white/male/upper middle class), craft breweries can become exclusionary spaces, setting at play processes that lead to displacement and turnover (Myles et al., Citation2020). Oldenburg (Citation1989) presented third places as harmonious sites, conjuring up a nostalgia for communal forms of engagement, yet third places can also create conflict, and exist in a “fragile condition” (Goode & Anderson, Citation2015, p. 346). As Thompson and Arsel (Citation2004) describe, “[i]n the fragmented and individuated age of postmodern consumer culture, a nostalgic view of community has become a highly commercialized trope through which consumers are able to forge an ephemeral sense of interpersonal connection via common consumption interests” (p. 639). Similarly, Papachristos et al. (Citation2011, p. 221) point to the “commodification of third place nostalgia” in marketing practices to ascribe status to a product. In working to create a specific identity and experience, third places may not welcome everyone from a community and/or may feel unwelcoming to particular populations (Myles et al., Citation2020). Ultimately, the social spaces of craft breweries are wrapped up with “social class, power, and aesthetic preferences” (Schroeder, Citation2020, p. 205). While these critical engagements provide a useful corrective to the almost universal depiction of third places as positive sites of community exchange, analysis of the function of third places across the urban hierarchy and across different zones and building types is needed.

Craft breweries utilize practices of neolocalism and third places to varying degrees to establish (and commodify) connections to place. These practices can in turn shift place identity and meaning and become intertwined with gentrification. Neolocalism works to redefine the identity of the local and establishes connections to a commodity, production process, and physical site. Similarly, third places establish a site for gathering and exchange, which creates value and interest. While craft breweries can function as important gathering spaces in their community where they encourage exchange and instill a sense of place, they can also form zones of exclusivity and displacement. As Myles et al. (Citation2020) note, craft breweries engage in placemaking; whether the placemaking associated with craft beer can be considered beneficial to everyone is largely dependent on the place itself. There is evidence of breweries operating as early gentrifiers, strategically brought into project development to catalyze urban change (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014). At the same time, craft breweries aren’t necessarily gentrifiers with examples of breweries working to redefine their relationship with local communities (Myles et al., Citation2020; Tuttle, Citation2020). Whether the brewery is more production-oriented or consumption-oriented will lead to different effects on gentrification, due to location and level of social exchange/placemaking. The uneven effects of craft breweries on places and populations points to the need for further analysis into the microgeographies of craft beer. In particular, understanding the role that urban planning (e.g. official community plans, zoning, reports) plays in fostering specific outcomes is critical to understanding the relationship between craft beer and gentrification.

Methodology

In this paper, I draw on a multi-method approach including site analysis, discourse analysis of planning documents (e.g. official community plans, zoning bylaws, reports) and media reports, and a neolocal assessment using craft brewery websites. First, to document contemporary beer production in Saskatoon and Regina, I completed a site analysis of 14 craft breweries from September 2019 to February 2021. This represented all the craft breweries (microbreweries, nanobreweries, and brewpubs) with bricks and mortar locations at the time of writing where craft beer production was a central function at the site. Of the 14 sites, 13 were microbreweries and one was a brewpub. All of the operations were independent and held membership with the Saskatchewan Craft Beer Association.Footnote1 The site analysis of the 14 locations marked out the current building use and condition, location characteristics and neighboring properties. I utilized a combination of photographic evidence and written descriptions to capture these elements. Photographs are included in the paper to capture the diversity of built form and location attributes. I followed up with property assessments and tax summaries through the City of Regina and the Saskatoon Assessment Office to confirm the age of each building. I classify buildings older than 50 years as “historic” in this research (constructed prior to 1971) to highlight the propensity for craft breweries to reuse spaces that might be at a higher risk of demolition, but which offer conceptual fit. Second, I analyzed official planning documents including official community plans, zoning bylaws, and reports in Saskatoon and Regina to mark out current development strategies and challenges, and the regulations surrounding craft breweries. A media analysis was performed on each brewery in the two cities, focusing on community linkages, sense of place, neolocalism, and the transformation of individual sites.Footnote2 Craft breweries that are in closer proximity to residential zones were better represented in these categories in the media. Lastly, I analyzed the websites for all the craft breweries to assess neolocal practices and orientation of the brewery (consumption/production). I looked specifically for branding (e.g. name of brewery, beer names, ingredients, and images on labels and on websites) and collaborations with other businesses/community partners. This assessment is used as a method to gauge the degree to which breweries connect with the “local” across different zones.

Saskatchewan (beer) context

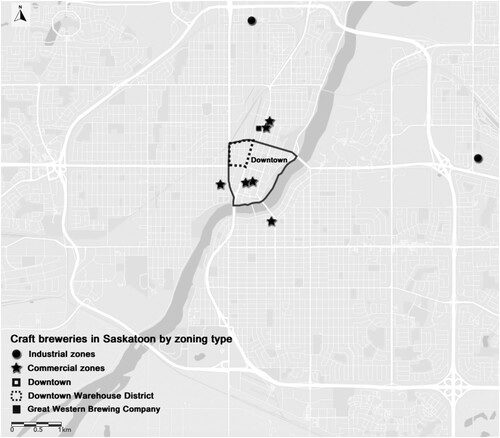

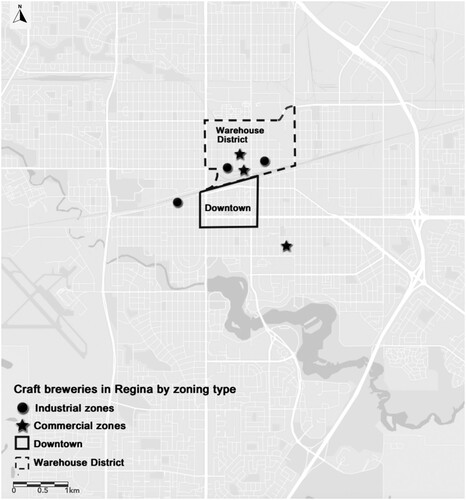

In Saskatchewan, craft breweries fall under the category of a craft manufacturer, producing between 50 and 30,000 hectoliters of beer annually (SLGA, Citation2021). In 2018, the craft beer industry in Saskatchewan produced a $30 million-dollar net benefit and 250 full-time jobs (Mark Heise, cited in Bernacki, Citation2019). Capturing approximately 3% of market share provincially, the craft beer industry has room to grow. As a leading comparator, in 2018 Ontario’s craft breweries climbed to 8.9% of provincial market share (OCB, Citation2020). Breweries in Saskatchewan have access to locally grown malt barley which is a strong locational advantage (Economic Development Regina, Citation2017). The province of Saskatchewan has a rate of 4.6 brewing facilities per 100,000 inhabitants, placing it above the national average of 3.4 (Beer Canada, Citation2021). Across the province, there are 21 craft breweries with bricks and mortar locations at the time of writing. The majority of these (14/21) are located within the two largest cities, Saskatoon (8) and Regina (6), providing a useful lens into the microgeographies that are critical to understanding the processes, and the presence, of craft breweries in mid-sized cities. Within both municipalities, there is significant clustering in central established areas ( and ). The majority of the craft breweries in the two cities (12/14) have made use of existing buildings, most of which were constructed 50 years ago or more. The trend towards adaptive reuse and historic building rehabilitation may simply be the result of limitations of where breweries are permitted/discretionary and the types of buildings available in these locations. Older buildings within more established areas provide craft breweries with lower land costs due to down filtering and the potential for creative experimentation.

Urban planning regulations for breweries in Saskatoon and Regina up until recently, were based on production-oriented, industrial breweries which required greater physical space and separation from residential and commercial zones due to compatibility issues. Industrial locations for breweries provide the least resistance in the planning process given that they avoid conflicting land uses such as proximity to schools and/or residences. For breweries, locating in a zone that permits alcohol production translates into a more streamlined process with less delays and potential for setbacks.

Saskatoon and Regina are both characterized by a decentralized urban form where outward expansion through the addition of new neighborhood developments has proceeded without concomitant investments and development into central established areas. Supply has outweighed demand resulting in high vacancy rates (Lynn, Citation2019) with growing rental housing in new suburban developments that lack public transit and access to community services. While both municipalities have implemented strategies to encourage repopulation in central areas (e.g. central business district and inner city), continued outward expansion has resulted in a failure to meet intensification targets for infill development and rehabilitation of existing buildings. There are numerous challenges in Saskatoon and Regina associated with “disrupting the status quo of peripheral growth, which perpetuates for a multitude of factors including the influence of powerful interest groups such as the development industry, consumer preferences or the limited power of planning as a regulatory tool affecting urban growth management” (Graham et al., Citation2019, p. 517). Given this context, the craft beer sector in Saskatoon and Regina is situated to play a role in each city’s intensification goals, adding interest and gathering spaces in central areas. In the subsequent sections, I document industrial and commercial zones where breweries are permitted/discretionary use in each city to demonstrate how these sites engage in neolocal practices and develop third places. I highlight the potential for these sites to contribute to gentrification processes given the shift in image and identity associated with the space, and the surrounding uses.

Saskatoon: planning for breweries

As Saskatchewan’s largest city, Saskatoon (264,637 in 2021) is home to eight bricks and mortar craft breweries, most of which opened within the last five years. Most of the city’s craft breweries are located in close proximity to the city center. Of the eight craft breweries currently in operation in Saskatoon, four resulted from discretionary use applications, three were permitted use, and one was approved in a zone (general light industrial) that until recently prohibited breweries. The majority (6/8) are in zones classified as commercial use with the remainder classified as industrial use. Craft breweries are prohibited in all residential zones owing to concerns with incompatible use, consistent across comparable municipalities in Canada.

Saskatoon is currently undergoing a zoning bylaw review (projected completion 2022) and is changing the regulations for craft breweries. The revisions to the current standards respond to “provincial regulatory changes and shifting consumer preferences” that “have led to a growing trend of small-scale producers” without regulations in the bylaw to support their entry into the market (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020a). Under current zoning regulations (bylaw 8770), breweries are permitted in heavy industrial zones and in the Downtown Warehouse District (City of Saskatoon, Citation2009a). In addition, craft breweries can be classified as “taverns” or “nightclubs” if the brewery constitutes a secondary use. Taverns and nightclubs are considered discretionary uses in a broader number of land use categories in Saskatoon zoning (institutional and mixed-use).

The revised bylaw (9691) distinguishes between breweries without on-site consumption and breweries with on-site consumption, “intended to address different land use implications of the operations” (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020a).Footnote3 While it is common in the United States to differentiate between microbreweries and brewpubs, Canadian municipalities do not typically differentiate between the two forms of consumption (CCBA, Citation2021). Under the new bylaw (bylaw 9691), craft breweries without on-site consumption are now permitted in heavy industrial and general light industrial zones and are considered discretionary in mixed-use districts (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020a). The spatial concentration of craft breweries in Saskatoon in central established areas is not consistent with previous zoning regulations. Instead, it reflects craft breweries applying for discretionary use applications and seeking out provincial licencing as taverns (where brewing is considered a secondary use) to expand zoning options. The revision to bylaw 9691 concerning craft breweries as a primary use, simply brings zoning into alignment with current practice.

Saskatoon’s revised zoning bylaw, especially as it pertains to craft breweries without on-site consumption, indicates a response to a growing consumer demand for small-scale producers. Moreover, the inclusion of additional zones in which breweries are permitted and/or discretionary uses will expand access to different types of built form. The addition of mixed use and light industrial zones for craft breweries without on-site consumption will offer greater contextual fit with access to foot traffic. The second amendment to the bylaw (projected completion 2022) will consider breweries with on-site consumption and is expected to lead to further expansion of zones.

Intensification planning

Saskatoon’s current Official Community Plan (OCP) (bylaw 8769) lays out the principles of compact development with strategic infill encouraged in established neighborhoods and in rapid transit corridors (City of Saskatoon, Citation2009b, pp. 8–9). The OCP was approved in 2009 and is currently undergoing a draft redesign to update the policy framework. There are several additional plans and reports, approved within the past decade, that direct current planning practice. The Growth Plan Technical Report (bylaw 9437) establishes the direction of development through strategic infill in several central areas (including the Downtown), as well as neighborhood infill in established residential areas (City of Saskatoon, Citation2016). These two target areas are intended to support 35% of growth. Between 2014 and 2018, on average, 14.8% of total new dwellings were infill (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020b). Saskatoon’s Vacant Lot & Adaptive Reuse Incentive Program is aimed at spurring development of chronically vacant sites in established areas (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020c). Specifically, the program works “to encourage development on existing vacant or brownfield sites, and the reuse of vacant buildings in established areas of the city, including the Downtown, by providing financial and/or tax-based incentives to owners of eligible properties” (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020b). As part of the plan to grow Saskatoon’s corridors, the Brownfield Strategy is intended to provide direction for development of lands with real and/or perceived threats of contamination from commercial/industrial use (City of Saskatoon, Citation2020d). Based on current and proposed municipal policy, Saskatoon has several active tools to foster intensification of existing communities. At present however, there are no impediments to peripheral growth. The outcome is an oversupply of housing at the periphery and exurban areas resulting in a waning demand for housing in central areas. The revision to the zoning bylaw which expands the zones that are permitted and discretionary for craft breweries fits with current intensification planning (nearly all the craft breweries are located in Downtown and established neighborhoods) aimed at creating vitality in central areas. In addition, the use of existing buildings by craft breweries works towards their goals of brownfield development and adaptive reuse.

Craft brewery location types

Of the eight craft breweries currently in operation in Saskatoon, half (4/8) are housed in historic buildings. The majority (6/8) adaptively reused an existing building with the remaining breweries constructing purpose-built infill spaces on vacant lots. Craft breweries in Saskatoon are spatially concentrated across several building types and locations. Over half (6/8) are located along commercial corridors in the Downtown and in central established areas, consistent with the growth plan. There are two outliers located in industrial zones away from the central city.

Industrial zones. There are two craft breweries located in industrial zones in Saskatoon: Paddock Wood Brewing Co. and High Key Brewing Co. Both breweries engage to a minimal extent with neolocal practices (e.g. incorporation of place names, histories, ingredients). High Key invested in creating a social space, but functions more as a destination site. Neighboring uses are primarily industrial in both cases with low walkability and a reliance on private vehicle use.

Paddock Wood, opened in 2002, is the oldest craft brewery in Saskatoon. Located in a strip mall within a light industrial zone, a mix of industry, multifamily units, and warehouse spaces surrounds the site. There is little visibility of the brewery from the road and the site mostly functions as a production facility. There are some links to local place referents in the brewery name and beer line-up (Paddock Wood is an area in Saskatchewan and beer names include Prairie Blonde and Saskatcheweizen). The potential for the site to catalyze gentrification (or engage in placemaking) is minimal given the neighboring uses and focus on production.

The High Key Brewing Company, established in 2018, is in a heavy industrial zone in close proximity to a rail line (). The building was formerly occupied by a Weber BBQ Store before falling into vacancy. Considering the location and former use of the space, the modern aesthetic in the interior is out of place in the industrial zone, as are the long, shared tables. High Key collaborates with local food trucks to provide patrons with a food option. Beyond this collaboration, neolocal practices in branding are minimal (there is a Boreal Pine Pale Ale as part of the beer lineup). The adjacent land uses include a granite/marble countertop distributor and an automotive repair center. Directly opposite is a steel and metal industrial outfit and a uniform rental company. The brewery is a destination point, offering a space for consumption in a location that is predominantly industrial. While the brewery attracts craft beer consumers, at present, the placemaking (e.g. shift in image and identity) is restricted to the site itself. The effect of the brewery on neighboring sites (e.g. turnover of tenants, change in the built form or character of a site) is minimal given the current land classification and tenant occupancy.

Commercial zones. The six craft breweries located in commercial zones in Saskatoon display varying degrees of neolocalism and third places. In part, the extent to which these indicators are present is dependent on proximity to a residential zone and whether the brewery is consumption-oriented (e.g. taproom, in-house restaurant, tasting room). The discussion that follows is separated into two categories relating to proximity to residential areas to mark out differing levels of neolocal practice and the establishment of gathering sites within this zoning classification.

Commercial zone within residential neighborhood. The four breweries that display strong neolocal practices and development of third places are located along trendy commercial districts close to neighborhoods that are gentrifying/gentrified.

In 2015, 9 Mile Legacy Brewing Co. converted an old pawn shop into a nanobrewery in the gentrifying neighborhood of Riversdale. The brewery is located along a commercial corridor known for its mesh of mom-and-pop shops, trendy retail stores and restaurants (). 9 Mile earned clout when Vogue Magazine listed it as a hip location in Saskatoon (Schwartz, Citation2017). The brewery engages in neolocal practices through naming (several beers reference local hockey leagues and others were created in partnership with local organizations), the inclusion of old historic artifacts (old trolly tracks uncovered during the renovation were refashioned into footrests), local ingredients, and collaboration with local businesses. While the motivations for locating in the area for 9 Mile co-owner Shawn Moen speak to a desire to return the neighborhood into “a very vibrant community … with lots of different cultures and people” (cited in Modjeski, Citation2019), community organizers worry about who is included in this vision, noting how “the introduction of new businesses and developments have increased living costs, making life more difficult for residents, without contributing any supports” (Erica Lee, cited in Modjeski, Citation2019). The brewery is situated close to a residential area which is currently seeing an influx of higher income residents attracted to the hip and trendy offerings and lower house values. This has placed pressure on the most vulnerable members of the community as costs of living continue to rise under gentrification (Bradshaw, Citation2018).

The Prairie Sun Brewery moved from its previous location in the city’s northern industrial district into a new purpose-built site in the historic Nutana neighborhood in 2019.Footnote4 Its current location on Broadway Avenue, a trendy commercial district, draws cues from local precedents in its design features and works to establish strong connections to the local. The building site was previously home to Lydia’s Pub (demolished in 2015), a popular and historic gathering space for the community. Prairie Sun incorporates bricks and timbers from the demolition into the interior and plans on creating a small museum geared to local history (Quenneville, Citation2019). The brewery will likely deepen gentrification processes (e.g. commercial and residential upgrading, displacement) already at play. Prairie Sun’s relocation onto Broadway Avenue coincided with a great deal of business turnover (e.g. trendy new restaurants and retail stores). The executive director of the Broadway Business Improvement District suggested that “the addition of the Prairie Sun Brewery has helped “tighten up” vacancies in the area” and reenergize the commercial strip (DeeAnn Mercier, cited in CBC, Citation2019). The Prairie Sun brewery engages in neolocalism in its naming practices (e.g. the brewery name itself alongside a couple of beers, Prairie Lily Lager and Broadway Black), the incorporation of historic artifacts and stories, and local ingredients. The pet friendly patio and tavern license attempt to create an inclusive gathering site for patrons, but as other researchers note about third places, marginalized actors may be excluded from the space (Myles et al., Citation2020).

Saskatoon Brewery and Better Brother Brewery are in the City Park neighborhood, a former industrial district. This mixed-use neighborhood is now known for its art galleries, historic buildings and close proximity to the Downtown. The population is middle-income with single family houses alongside apartment buildings. Saskatoon Brewery has a taproom that can be accessed through Earl’s Restaurant, a popular chain which also sells the brewery’s beer on tap. Ingredients Artisan Market is in the same complex, specializing in local products and high-end artisan goods. The brewery is not visible from the street and is instead tucked in behind the restaurant along an alleyway. Despite the lack of street visibility, it benefits from its relationship with Earl’s. It engages in neolocalism in naming (Saskatoon Brewery and a beer named Saskatoon Berry Dark) and collaborates with local businesses. Steps away from the Saskatoon Brewery is Better Brother Brewery, one of Saskatoon’s newest craft breweries, opened in 2020. With a small expanding beer line-up, there is currently one beer that references the local (Boundary Dam Porter, referencing a power station in Saskatchewan). Both breweries are close to the Great Western Brewing Co. on 2nd Avenue North (Better Brother is opposite and Saskatoon Brewery is diagonal), one of Saskatchewan’s oldest regional breweries. The Great Western brewing location dates to 1927 (originally established as the Hub City Brewing Co.).Footnote5 The brewery earned recognition when an impending closure of the site resulted in 16 workers pooling their resources together to form the Great Western Brewery. There is a great deal of brewing history associated with 2nd Avenue North in Saskatoon and the connection between beer and place is strong. The houses near the three breweries are mostly postwar single detached houses that have undergone minimal renovations to the exterior, and multifamily units. Given its visibility (and contextual fit) in the neighborhood, there is potential that the Better Brother Brewery will initiate further upgrading in the area as it establishes itself.

Commercial zone within a commercial district. The remaining two breweries in the commercial zoning classification (Shelter Brewing Co., 21st Street Brewery) are located in the Downtown and display minimal neolocal practices and third places geared to a more mobile population. There is limited media discussion of these breweries relating to community linkages, sense of place, and/or local connections.

Shelter Brewery is located in a commercial corridor in the Downtown surrounded by chic restaurants and retail offerings. The brewery partners with Dylan and Cam’s Tacos to provide a food option. There are no references to place in naming or branding. The nanobrewery provides a small gathering space and references their desired image as a community hub on their website. The 21st Street Brewery is also located in the Downtown, in the basement of the Hotel Senator, a formerly underdeveloped space. The landmark building, constructed between 1906 and 1908, is a heritage-protected site, minimizing the potential to radically alter its built form or character. In other words, the presence of the brewery adds to the offerings already on site without any drastic changes to place identity and/or image, and is accessible through Winston’s Pub, a space which was established when the hotel first opened in 1908. Neolocalism is seen in the brewery name (21st Street) and in one beer (Uptown Brown). The brewery will likely have minimal effects on neighboring sites given that the addition, surrounded by well-established tenants, does not radically shift the present offerings.

Regina: planning for breweries

With a population of 224,996, (Statistics Canada, Citation2021), Regina is home to six craft breweries, the majority of which (4/6) are spatially concentrated in the Warehouse District, an industrial area adjacent to the Downtown. Whereas Saskatoon differentiates between craft breweries and large-scale breweries in their zoning regulations, Regina does not define what constitutes a brewery and does not differentiate between different types of consumption. In 2018, the prairie city was ranked fourth best beer town in Canada (Baxter, Citation2018). The title reflects the craft brewery offerings as well as the presence of the Ale & Lager Enthusiasts of Saskatchewan (ALES) club. The ALES club is where many of the city’s craft brewers began their careers. In addition, Rebellion Brewing Co. hosts the Lady Rebels Beer Club, which supports women in craft beer through special meetings, events, and brewing opportunities. There is a strong sense of collaboration across breweries in Regina. All the craft breweries participate in the annual Hop Circuit self-guided tour sponsored by Tourism Regina and the Regina Warehouse District (Regina’s Warehouse District, Citation2021). As Myles and Breen (Citation2018, p. 167) demonstrate, the influence on place is present at the level of individual breweries but becomes stronger when breweries collect together.

In 2019, Regina approved a new zoning bylaw (bylaw 2019-19) which has expanded the geography of craft breweries (City of Regina, Citation2019). Any applications submitted prior to this date will follow zoning bylaw 9250 which classifies breweries as manufacturing use, permitted only in industrial zones (light, medium, and heavy) and in the Warehouse District Direct Control District (City of Regina, Citation1992). This former zoning bylaw (9250) has largely directed the geography of beer in the city up until this point. The new bylaw (2019-19) expands the potential land use classifications for breweries: breweries are now permitted and/or discretionary use in seven Direct Control Districts, the majority of mixed-use zones (mixed low rise, mixed high rise, and mixed large market zone) and industrial zones (light, heavy, and prestige). Of the six craft breweries in operation in Regina, all are housed in zones where breweries are permitted. Each brewery is located in a distinct land use zone, three under the broad category of commercial use and three under the category of industrial use. In both the former bylaw and the new bylaw, breweries are prohibited in all residential zones.

Intensification planning

Regina’s OCP, Design Regina, states an intensification target of 30% of new growth to take place in established areas (City of Regina, Citation2013). The proportion of new dwellings constructed in established areas in Regina between 2014 and 2018 was closer to 14% (White-Crummy, Citation2018), with the majority developed on outlying greenfield sites. Within the city’s intensification boundary, the Underutilized Land Study (City of Regina, Citation2018) found 585 sites that were empty or underutilized, 130 surface parking lots and close to 40 vacant buildings (p. 27). Similar to the City of Saskatoon, the City of Regina is trying to find the right balance between greenfield development and intensification planning to accommodate growth. The Underutilized Land Study (City of Regina, Citation2018) notes that “[i]t has been proven that strong urban growth containment policies generate more interest in redeveloping underutilized lands” (p. 1), yet the City of Regina has not curtailed peripheral growth. Instead, they established an Intensification Levy (effective October 2019 and repealed in November 2021) directed at all development within the established areas of Regina that will lead to intensification, “intended to cover a portion of capital infrastructure costs, ensuring growth pays for growth” (City of Regina, Citation2020). This boundary encapsulated all intensification development from suburban development sites to vacant and underused sites in the central areas of the city. Since the 1980s, intensification development in central areas was exempt from these charges; the levy was charged on all central area intensification development to offset servicing costs. At a time when the city is falling behind on its intensification targets, the levy created a disincentive for central area development.

Craft brewery location types

Of the six craft breweries currently in operation in Regina, the majority (5/6) are housed in historic buildings, and all adaptively reused existing buildings. There is significant clustering in the Warehouse District (4/6), owing to the former zoning bylaw. It is worth noting that there is a strong history of beer production in this area, housing Regina’s two original breweries.Footnote6 The Warehouse District is presently gentrifying, housing a mix of loft dwellers and independent retailers juxtaposed with light industrial tenants. In the discussion that follows, I separate the analysis into industrially zoned and commercially zoned breweries.

Industrial zones. The three craft breweries located in industrial zones in Regina vary in their use of neolocal practices and development of third places. As a result, their potential to catalyze and/or deepen gentrification processes varies. While District Brewing is a production-oriented facility with a small tasting room, Bushwakker and Pile O’ Bones are consumption-oriented breweries. Bushwakker is a brew-pub, with over 50% of its sales arising from the restaurant side, and Pile O’ Bones has a large taproom and partners with an onsite restaurant.

Established in 2013, District Brewing in Regina is located in a heavy industrial zone in the Warehouse District (). The brewery transformed a large boxy space constructed in the 1960s for gymnastics use into a production-based facility. In addition to brewing under their brand, they contract brew for a number of Saskatchewan breweries. The adjacent and surrounding land uses are industrial/commercial. Given the former use of the space, the structure is familiar to community members. The addition of a small outdoor patio and public tours have repositioned this area in people’s imaginations. Besides the brewery name (a reference to the Warehouse District), there are no additional expressions of neolocalism. The potential for this site to spur gentrification or displacement is minimal given its production focus and current surrounding uses.

Bushwakker Brewing and Pile O’ Bones Brewing Co. share many similarities. They are both consumption-oriented and display strong connections to the community. As one of the oldest craft breweries in the province dating back to 1991, the Bushwakker brewpub is a landmark in the Warehouse District (). Located on the main floor of a renovated 1914 building, the brewpub was brought in as the anchor tenant of the conversion and further catalyzed the area’s transition from an industrial district into a thriving mixed-use area with a substantive residential population living in upscale converted loft spaces (Mathews, Citation2019). The adjacent land use classifications are retail and entertainment on the ground floors and residential on the upper levels. The interior is clad with local historic photos and showcases Saskatchewan art and music (Coles, Citation2015). A handful of the beer names reference local attributes (Northern Lights Lager, Regina Pale Ale, Stubblejumper Pils – the latter referring to a field of wheat after harvest or a term for a person from the prairies). Across from the Bushwakker is the Rail Yard Renewal Project, a 17.5-acre site approved for a mixed-use development. While the portion of the Warehouse District housing the brewery is already gentrifying, as the planning context of the Rail Yard unfolds, there could be further waves of upgrading. The Pile O’ Bones Brewing Co. is located in an industrial zone within the gentrifying Cathedral neighborhood. Originally opened in 2016 in the Downtown district, the brewery moved locations in 2019, adaptively reusing a former automotive dealership. The surrounding uses include retail and home renovation suppliers and a rail yard directly across the street. Of note, the stadium for the Saskatchewan Roughriders, a professional Canadian football team, is within walking distance of the brewery which translates into crowds on game day. Pile O’ Bones engages in neolocal practices in naming and branding. Based on the website description, the brewery name, Pile O’ Bones, is Regina’s unofficial nickname and the logo features a plains bison, a reflection of Indigenous life on the prairies prior to the arrival of settler colonists. The majority of the beer cans feature a grain elevator, an image associated with the prairie province. The taproom offers guest taps and the brewery partners with an onsite restaurant featuring local ingredients. The brewery has reimaged an individual site, and in time may deepen gentrification processes already at play.

Figure 6. The Bushwakker Brew-Pub is housed in a heritage-protected, mixed-use building in Regina's Warehouse District.

Commercial zones. There are three craft breweries located in commercial zones in Regina: Malty National Brewing Corp., Warehouse Brewing Co., and Rebellion Brewing Co. While Malty National is located in a neighborhood undergoing gentrification, the other two breweries are located in the Warehouse District which, as noted earlier, has pockets of gentrification.

When the owners of Malty National proposed converting an underused commercial building in an inner-city neighborhood into a craft brewery (), they faced opposition from some residents concerning potential intoxication and proximity to schools. The site was zoned as a contract zone in the city’s Heritage neighborhood, allowing a unique development opportunity to create desired results. Adam Smith, one of the owners, responded in the media: “We’re not going to be a bar at all … We’re not going to have anybody intoxicated here” (quoted in CBC, Citation2015). In 2016, the rezoning application was approved by City Council and the brewery opened up shortly after. Since establishing the brewery in the neighborhood, an existing retail cluster on the next block underwent a turnover in tenancy, adding a diner and hair salon. The brewery partners with 33 1/3 coffee roasters and incorporates local wares for sale into the space. Neighboring land uses are predominately residential with a hospital and schools in walking distance. Malty National refers to itself as a community space and indicates on its website that it is pet friendly and child friendly. One resident of the area who regularly visits the brewery with their children, described the brewery as, “this hub of community action and a place for everyone to go to feel welcome” (Risa Payant, cited in Ackerman, Citation2017). The neighborhood is facing pressures of gentrification with an influx of middle-class uses/users and a loss of affordable rental sites (Core Community Association, Citation2008). With high levels of neolocalism (partnerships) and development of a community hub third place, the brewery may spur further rounds of upgrading.

The two commercially zoned breweries housed in the Warehouse District express neolocalism and have developed social spaces. Warehouse Brewing Co. is housed in the historic Weston Bakery, built in 1929. The brewery draws a narrative and visual representation of the history of the building and area on its website. It evokes place through its name, and the majority of the beers make reference to the building and/or the prairies (Factory Stout, Loading Dock Lemon Ale, Sask Harvest Helles Lager). As one of the newest breweries in Regina (opened in 2020), the conversion of the Weston Bakery has transformed a section of the Warehouse District for a middle to upper-class clientele. Another part of the building was recently converted into Local Market YQR, a space which offers a grocery store and delivery service premised on local producers, a food hall and on-site event venue. The addition of the Warehouse Brewery adds to this destination complex focused on local production. The Rebellion Brewery is situated along a historic corridor, in a 1990s warehouse building. The brewery prides itself on using local ingredients wherever possible (e.g. honey from Tisdale, Saskatchewan, berries from Lumsden, Saskatchewan). They work towards inclusivity by partnering with local charities and organizations and collaborating with other businesses. Adding to their connections to the local, the brewery hosts biweekly podcasts featuring local talents and interests. El Tropezon, a restaurant featuring Mexican fare, is available in the taproom. The standard beer lineup contains two beers that reference place in name and/or image (Lentil Beer referencing local production of the grain legume, and Zilla IPA which features a grain elevator on the can design).

Discussion on craft breweries in Saskatoon and Regina

The analysis of craft breweries in Saskatoon and Regina highlights how craft beer sites become intertwined with gentrification (as catalysts or accelerants) dependent on their orientation (production-oriented or consumption-oriented), and neighboring uses. The majority of the breweries in the two cities have adaptively reused existing buildings, many on brownfield sites (e.g. industrial buildings) and vacant lots that were difficult to transition. These sites of craft brewing, while indicative of “conceptual fit” and authenticity (Flack, Citation1997; Reid & Gatrell, Citation2017b), are also tied to regulations that direct breweries into particular geographies where industrial/historic built form is more prevalent. The craft breweries located in commercial zones in Saskatoon and Regina with a consumption focus, especially those neighboring residential areas, display the strongest potential to trigger/extend gentrification given the shift in the identity of the area and development of third places. All of the breweries in this classification engage with neolocal practices and express strong connections to place. Production-oriented breweries are located in industrial zones in both cities. In these instances, reimaging of an individual site is present, but there is limited spillover given neighboring uses. These breweries engage to some extent with neolocal practices, through collaborations with local businesses and the inclusion of local referents in names, and are unlikely to function as third places. Craft breweries located in industrial zones with an orientation towards consumption on the other hand, engage in neolocal practices and function as third places. In cases where these breweries are in close proximity to residential areas, they are able to tap into a neighborhood identity (and consumer base) and establish connections to place, which over time may deepen/trigger gentrification processes.

As craft brewing sites are associated with middle to upper-class tastes and consumption practices (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014; Murray & O’neill, Citation2012), in zones where gentrification potential is high, the two municipalities might consider the addition/retention of community services, and affordable housing and rental units to lessen potential displacement. Given the exponential growth of the sector across Canada, zoning for craft breweries should be reviewed every five years to minimize unwanted effects.

The need to create places for informal public life through third places is especially amplified in cities such as Saskatoon and Regina that have lost some of their core vitality. Saskatoon and Regina recently expanded the geography of beer, approving additional zones (e.g. mixed-use, commercial, light industrial) where craft breweries are permitted/discretionary in their land use bylaws. The expansion of craft breweries into additional zones satisfies the goals for intensification planning to attract vitality and population to central areas. Craft breweries are prohibited in both municipalities from locating within residential zones. As Oldenburg (Citation1996) suggests, “planners can help foster the conditions in which [third places] might emerge. One way is by eliminating the policies prevalent in so many zoning codes of prohibiting commercial uses … from locating where people live” (p. 10). The separation of (perceived) incompatible uses within the zoning regulations limits the extent to which breweries may serve as “catalyst[s] for the (re)evolution of places” (Myles & Breen, Citation2018, p. 167). Understanding the potential effects of craft breweries across zones in Saskatoon and Regina is integral to balancing the desire for intensification with the needs of the community.

Conclusion

Understanding the where of craft breweries is critical to understanding the types of effects that breweries are having on place. This paper builds on the emerging body of research on craft breweries and gentrification in large metropolitan areas (Mathews & Picton, Citation2014; Walker & Fox Miller, Citation2019; Weiler, Citation2000) with a focus on two mid-sized peripheral cities in the Canadian prairies. Using zoning bylaws and strategic planning approaches, I highlight how craft breweries in Saskatoon and Regina are positioned as agents of urban change as part of a broader goal for intensification of central areas. Currently, there is little research on the role of zoning and urban planning policies to direct and limit the location of craft breweries (see Nilsson et al., Citation2018). My findings contribute to this research gap through an analysis of how zoning influences brewing locations, and how zoning can be used to assess gentrification potential.

In order to analyze the nexus between zoning and gentrification, I examine the extent to which a set craft breweries transform place (shifting image and identity) using two concepts that are connected with gentrification and are characteristic of the brewing industry: neolocalism and third places. While neolocalism is tied to a shift in consumer preferences towards place-based offerings and production processes, the development of third places creates connections between place, identity, and belonging. In the two mid-sized cities interrogated in this paper, the presence of craft breweries in central established areas is intertwined with gentrification in sites that are consumption based (taprooms, in-house restaurants, tasting rooms) and which are located in commercial zones, especially those in close proximity to residential areas. These sites display strong neolocal tendencies and develop third places that provide community exchange and place attachments (Rojak & Cole, Citation2016).

Saskatoon and Regina are two mid-sized cities that have different economic and political pressures (outward expansion and weakened intensification) compared to other cities along the urban hierarchy. Additional case studies are needed to build understanding of the relationship between urban planning and gentrification across urban contexts to assess how different planning issues and approaches (e.g. zoning bylaws, community plans) work to direct the place (and effects) of craft breweries. Lastly, more research is needed to mark out how the location preferences (and building types) of craft breweries are directed, and potentially limited, by urban planning.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editor Nathan McClintock for their thoughtful and constructive feedback. Jessica Merk provided research assistance for the media analysis component.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In addition to the 14 craft breweries included in this research, there are a number of brewpubs (chains and independents) in Saskatoon and Regina that form part of the local beer scene. These additional brewpub sites offer a diversity of food and alcoholic beverages, have off-sale licensing (allowing for the sale of beer, wine, and spirits for off premise consumption) and a handful produce beer on site as a secondary function.

2 The Regina Leader-Post, Saskatoon Star Phoenix, and CBC Saskatchewan were the news sources used in the media analysis.

3 The zoning bylaw revision differentiates between large-scale breweries (regional/national breweries with annual output > 20,000 hectoliters) and small-scale breweries (annual output < 20,000 hectoliters).

4 Saskatoon’s first site of historic beer production was housed in the Nutana neighborhood. The Hoeschen-Wentzler Brewing Co. was established in the neighborhood in 1906, and became Saskatoon Brewing Co. (1915), and finally Labatt Brewery (1960). The original building was demolished.

5 The Hub City Brewing Co. went through several name changes and turnovers, becoming Western Canada Brewery (1930), Drewry’s (1932), Carling, and finally Carling O’Keefe (1974). In 1989, Molson’s acquired Carling O’Keefe and initiated a plan to close the brewery. Former workers of the plant purchased the brewery and formed the Great Western Brewery.

6 Similar to Saskatoon, there were two historic sites of beer production in Regina. Both were housed in the city’s industrial area north of the railway where the concentration of contemporary beer production continues in the present Warehouse District. The first site housed the Regina Brewing Co. and was established in 1907. Prior to this, other breweries had brief periods of operation in Regina stretching back to 1887. The Regina Brewing Co. became Sick’s Brewing (1948), and then Molson’s Brewing (1959), eventually closing in 2002. The second site was established in 1928 as the Adanac Brewery (Canada spelled backwards). Through a process of acquisitions, mergers, and name changes, it became Drewry’s (1935), Blue Label (1952), Carling (1954), and finally Carling O’ Keefe before closing in 1989. Both buildings were demolished.

References

- Ackerman, J. (2017, October 29). Local businesses helping transform Heritage neighbourhood into tight-knit community. Leader-Post. https://leaderpost.com/news/local-businesses-helping-transform-heritage-neighbourhood-into-tight-knit-community.

- Apardian, R. E., & Reid, N. (2020). Going out for a pint: Exploring the relationship between craft brewery locations and neighborhood walkability. Papers in Applied Geography, 6(3), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/23754931.2019.1699151

- Baginski, J., & Bell, T. L. (2011). Under-tapped?: An analysis of craft brewing in the southern United States. Southeastern Geographer, 51(1), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.2011.0002

- Barajas, J. M., Boeing, G., & Wartell, J. (2017). Neighbourhood change, one pint at a time: The impact of local characteristics on craft breweries. In N. G. Chapman, J. Slade Lellock, & C. D. Lippard (Eds.), Untapped: Exploring the cultural dimensions of craft beer (pp. 155–176). West Virginia University Press.

- Baxter, D. (2018, September 7). Regina ranked 4th best beer town in Canada. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/4435145/regina-ranked-4th-best-beer-town-in-canada/.

- Beer Canada. (2021). 2020 Industry trends. https://industry.beercanada.com/statistics.

- Bernacki, J. (2019, November 13). Relaxed regulations, improved collaboration spur growth of craft brewing industry. CTV News. https://saskatoon.ctvnews.ca/relaxed-regulations-improved-collaboration-spur-growth-of-craft-brewing-industry-1.4684648.

- Bradshaw, C. D. (2018). I think we’re all having the wrong conversation: The relationship between the gentrification of Riversdale and the well-being of local residents [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Regina.

- Buratti, J. P. (2019). A geographic framework for assessing neolocalism: The case of Texas hard cider [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Texas State University.

- CBC. (2015, March 3). Microbrewery will be asset to Regina neighbourhood, businessman says. CBC Saskatchewan. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/microbrewery-will-be-asset-to-regina-neighbourhood-businessman-says-1.2979955.

- CBC. (2019, September 7). As Saskatoon street fair celebrates 36th year, business owners say ‘Broadway is coming back’. CBC Saskatchewan. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/saskatoon-broadway-rebirth-street-fair-1.5274833.

- CCBA: Canadian Craft Brewers Association. (2021). About. https://ccba-ambc.org/about/.

- Chapman, N. G., Nanney, M., Lellock Slade, J., & Mikles-Schluterman, J. (2018). Bottling gender: Accomplishing gender through craft beer consumption. Food, Culture & Society, 21(3), 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2018.1451038

- City of Regina. (1992). Zoning bylaw (bylaw 9250).

- City of Regina. (2013). Design Regina: The official community plan. https://www.regina.ca/about-regina/official-community-plan/.

- City of Regina. (2018). Underutilized land study. https://www.regina.ca/export/sites/Regina.ca/business-development/land-property-development/.galleries/pdfs/Planning/Undertulized-Land-Study.pdf.

- City of Regina. (2019). Zoning bylaw 2019-019. https://www.regina.ca/bylaws-permits-licences/bylaws/Zoning-Bylaw/.

- City of Regina. (2020). Intensification levy. https://www.regina.ca/export/sites/Regina.ca/business-development/land-property-development/.galleries/pdfs/Land-Development/Intensification-Levy-Brochure-2020.pdf.

- City of Saskatoon. (2009a). Zoning bylaw 8770. https://www.saskatoon.ca/sites/default/files/documents/city-clerk/bylaws/8770.pdf.

- City of Saskatoon. (2009b). Official community plan (bylaw 8769). https://www.saskatoon.ca/sites/default/files/documents/city-clerk/bylaws/8769.pdf.

- City of Saskatoon. (2016). Growth plan technical report (bylaw 9437). https://www.saskatoon.ca/sites/default/files/documents/community-services/planning-development/integrated-growth-plan/growing-fwd/growth-plan-technical-report_february-2016-1.pdf.

- City of Saskatoon. (2020a). Land use application: Proposed zoning bylaw text amendment – general regulations for microbreweries. File No. PL 4350 – Z3/17.

- City of Saskatoon. (2020b). Growth monitoring report. https://www.saskatoon.ca/sites/default/files/documents/community-services/planning-development/research/miscellaneous/appendix_1_-_2020_growth_monitoring_report.pdf.

- City of Saskatoon. (2020c). Vacant lot & adaptive reuse strategy. https://www.saskatoon.ca/business-development/planning/neighbourhood-planning/vacant-lot-adaptive-reuse-strategy9.

- City of Saskatoon. (2020d). Brownfield renewal strategy. https://www.saskatoon.ca/sites/default/files/documents/community-services/planning-development/integrated-growth-plan/growing-fwd/brownfield_panels_for_website.pdf.

- Coles, S. (2015, October 1). Bushwakker Brewpub: Marking 25 years of pouring pints in the Warehouse District. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/bushwakker-brewpub-marking-25-years-of-pouring-pints-in-the-warehouse-district-1.3250648.

- Core Community Association. (2008). The core neighbourhood sustainability action plan. https://heritagecommunityassociation.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/final-core-plan-08.pdf.

- Eades, D., Arbogast, D., & Kozlowski, J. (2017). Life on the “beer frontier”: A case study of craft beer and tourism in West Virginia. In S. Slocum, C. Kline, & C. Cavaliere (Eds.), Craft beverages and tourism (pp. 57–74). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eberts, D. (2007). To brew or not to brew: A brief history of beer in Canada. Manitoba History, 54, 2–13.

- Eberts, D. (2014). Neolocalism and the branding and marketing of place by Canadian microbreweries. In M. W. Patterson, & N. Hoalst-Pullen (Eds.), The geography of beer: Regions, environment, and societies (pp. 189–199). Springer.

- Economic Development Regina. (2017). Craft brewing impact study on the Greater Regina Area. https://economicdevelopmentregina.com/about/publications#craft-brewing-impact.

- Everett, S., & Aitchison, C. (2008). The role of food tourism in sustaining regional identity: A case study of Cornwall, South West England. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(2), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost696.0

- Feeney, A. E. (2015). The history of beer in Pennsylvania and the current growth of craft breweries. Pennsylvania Geographer, 53(1), 25–43.

- Filion, P., Bunting, T., Pavlic, D., & Langlois, P. (2010). Intensification and sprawl: Residential density trajectories in Canada’s largest metropolitan regions. Urban Geography, 31(4), 541–569. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.31.4.541

- Flack, W. (1997). American microbreweries and neolocalism: ‘Ale-ing’ for a sense of place. Journal of Cultural Geography, 16(2), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873639709478336

- Fletchall, A. M. (2016). Place-making through beer-drinking: A case study of Montana’s craft breweries. Geographical Review, 106(4), 539–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2016.12184.x

- Goode, A., & Anderson, S. (2015). “It’s like somebody else’s pub”: Understanding conflict in third place. In K. Diehl, & C. Yoon (Eds.), NA - Advances in consumer research (Vol. 43, pp. 346–351). Association for Consumer Research.

- Graham, R. (2018). PLAN North West, Autumn 2018 (pp. 27–30). https://www.albertaplanners.com/sites/default/files/PlanNW_Fall2018_WEB.pdf

- Graham, R., Han, A. T., & Tsenkova, S. (2019). An analysis of the influence of smart growth on growth patterns in mid-sized Canadian metropolitan areas. Planning Practice & Research, 34(5), 498–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2019.1601800

- Hawley, C. (2015, March 9). Beer-oriented development (BOD). Visit Buffalo Niagara: Food & Drink. https://www.visitbuffaloniagara.com/buffalos-beer-oriented-development-bod/

- Holtkamp, C., Shelton, T., Daly, G., Hiner, C. C., & Hagelman, R. (2016). Assessing neolocalism in microbreweries. Papers in Applied Geography, 2(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/23754931.2015.1114514

- Ikäheimo, J. P. (2021). Arctic narratives: Brewing a brand with neolocalism. Journal of Brand Management, 28(4), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00232-y

- Lynn, J. (2019, December 16). Housing ‘oversupply’ tilts prairie market in favour of buyers. CTV News Saskatoon. https://saskatoon.ctvnews.ca/housing-oversupply-tilts-prairie-market-in-favour-of-buyers-1.4732559.

- Mathews, V. (2019). Lofts in translation: Gentrification in the Warehouse District. The Canadian Geographer, 63(2), 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12495

- Mathews, V., & Picton, R. (2014). Intoxifying gentrification: Brew pubs and the geography of post-industrial heritage. Urban Geography, 35(3), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2014.887298

- Mclaughlin, R. B., Reid, N., & Moore, M. S. (2014). The ubiquity of good taste: A spatial analysis of the craft brewing industry in the United States. In M. W. Patterson, & N. Hoalst-Pullen (Eds.), The geography of beer: Regions, environment, and societies (pp. 131–154). Springer.

- Modjeski, M. (2019, May 9). Bar owners hope balance, responsibility will prevent booze-fueled problems on 20th Street. Riversdale BID. https://www.riversdale.ca/news-post?hid = 129.

- Murray, A., & Kline, C. (2015). Rural tourism and the craft beer experience: Factors influencing brand loyalty in rural North Carolina, USA. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8-9), 1198–1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.987146

- Murray, D. W., & O’neill, M. A. (2012). Craft beer: Penetrating a niche market. British Food Journal, 114(7), 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701211241518

- Myles, C. C., & Breen, J. (2018). (Micro)movements and microbrew: On craft beer, tourism trails, and material transformation(s) in the city. In S. L. Slocum, C. Kline, & C. T. Cavaliere (Eds.), Beers, ciders and spirits: Craft beverages and tourism in the U.S (pp. 159–170). Palgrave.

- Myles, C. C., Holtkamp, C., McKinnon, I., Baltzly, V. B., & Coiner, C. (2020). Booze as a public good?: How localized, craft fermentation industries make place, for better or worse. In C. C. Myles (Ed.), Fermented landscapes: Considering how processes of fermentation drive social and environmental change in (un)expected places and ways (pp. 21–56). University of Nebraska Press.

- Nilsson, I., Reid, N., & Lehnert, M. (2018). Geographic patterns of craft breweries at the intraurban scale. The Professional Geographer, 70(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2017.1338590

- OCB: Ontario Craft Brewers. (2020). Facts and figures. http://www.ontariocraftbrewers.com/factsandfigures.html.

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place: Café, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. Paragon House Publishers.

- Oldenburg, R. (1996). Our vanishing third places. Planning Commissioners Journal, 25(4), 6–10.

- Papachristos, A. V., Smith, C. M., Scherer, M. L., & Fugiero, M. A. (2011). More coffee, less crime? The relationship between gentrification and neighborhood crime rates in Chicago, 1991 to 2005. City & Community, 10(3), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2011.01371.x

- Parnwell, M. J. G. (2007). Neolocalism and renascent social capital in Northeast Thailand. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(6), 990–1014. https://doi.org/10.1068/d451t

- Patterson, M. W., & Hoalst-Pullen, N. (2014). Geographies of beer. In M. W. Patterson, & N. Hoalst-Pullen (Eds.), The geography of beer: Regions, environment, and societies (pp. 1–8). Springer.

- Pena, A., Jamilena, D., & Molina, M. (2012). The perceived value of the rural tourism stay and its effect on rural tourist behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(8), 1045–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.667108

- Plummer, R., Tefler, D., Hashimoto, A., & Summers, R. (2005). Beer tourism in Canada along the Waterloo-Wellington ale trail. Tourism Management, 26(3), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.12.002

- Quenneville, G. (2019, August 28). The Sun shall rise: Here’s a sneak peek inside the new Prairie Sun Brewery on Broadway. CBC News Saskatchewan. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/the-sun-shall-rise-here-s-a-sneak-peek-inside-the-new-prairie-sun-brewery-on-broadway-1.5261949.

- Regina’s Warehouse District. (2021). Hop circuit: A self-guided tour of Regina’s craft breweries. https://www.warehousedistrict.ca/news/hop-circuit.

- Reid, N. (2018). Craft breweries, adaptive reuse, and neighbourhood revitalization. Urban Development Issues, 57(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.2478/udi-2018-0013

- Reid, N., & Gatrell, J. D. (2017a). Craft breweries and economic development: Local geographies of beer. Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal, 7(2), 90–110.

- Reid, N., & Gatrell, J. D. (2017b). Creativity, community, & growth: A social geography of urban craft beer. Region, 4(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.18335/region.v4i1.144

- Rojak, D., & Cole, L. B. (2016). Place attachment and the historic brewpub: A case study in Greensboro, North Carolina. Journal of Interior Design, 41(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/joid.12066

- Schnell, S. M., & Reese, J. F. (2003). Microbreweries as tools of local identity. Journal of Cultural Geography, 21(1), 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873630309478266

- Schroeder, S. (2020). Crafting new lifestyles and urban places: The craft beer scene of Berlin. Papers in Applied Geography, 6(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/23754931.2020.1776149

- Schwartz, A. (2017, January 15). Canada’s Prairies - vaguely exotic, totally obscure, and an absolute must-visit destination. Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/article/saskatoon-winnipeg-canada-prairie-travel-guide.

- SLGA: Saskatchewan Liquor and Gaming Authority. (2021). Fact sheet Saskatchewan beverage alcohol manufacturing. https://www.slga.com/liquor/for-craft-producers.