ABSTRACT

What constitutes the “landing” of “traveling planning concepts” (TPCs) in new places remains conceptually elusive in the literature. To explore this process, this paper proposes a multidimensional conceptual framework that identifies key recurring activities during landing. The framework is applied to a qualitative analysis of the ongoing development of an innovation district in the rising yet unequal city of Medellín. The analysis reveals a process during which introductions of the concept with add-on components were legitimized based on translations adjusting it to the local circumstances, while governance procedures coordinated mandates for action, and a version of the concept gradually materialized. These recurring activities constituted mechanisms that generated the progression of landing through subsequent phases. In Medellín, the TPC resulted in a distributed model that corresponds neither to the prevailing innovation district concept nor the locally intended socially inclusive version. This paper contributes by showing why the analysis of landing processes is key to understanding whether, how, and in what form traveling planning concepts appear in new destinations. This novel framework enables a systematic and comprehensive identification of the causal process comprising the mechanisms that make both the TPC landing and the version of the TPC it produces unique.

Introduction

Cities monitor each other’s urban planning solutions. When those solutions convey values and ideals that are broadly esteemed or originate in prestigious places (Healey, Citation2013, p. 1512; Wood, Citation2015a), they are imitated, albeit in different socioeconomic conditions (Healey, Citation2013, p. 1511). They become what Healey (Citation2010) calls traveling planning concepts (TPCs). In her view, such concepts are “likely to be shaped by their origins and by the channels through which they have traveled” (Healey, Citation2011, pp. 200–201). In related literature on policy mobilities (PM), mobile policies have been said to be “in part made through their travels” (Ward, Citation2018, pp. 276–277). More precisely, there are three main instances in the “travels” in which TPCs may change. First, they may change when they are “packaged” (González, Citation2011, p. 1403) or “codified” (Peck & Theodore, Citation2010b, p. 207) for travel. Then, they can be modified by the intermediaries (e.g. planners, consultants) who carry them (cf. McCann, Citation2011; Prince, Citation2012). Finally, they are adjusted to new local conditions (e.g. Healey, Citation2010, p. 6; Perera, Citation2010, p. 146; cf. Cochrane & Ward, Citation2012, p. 5; Ward, Citation2002, pp. 6–9). It is this third instance, the “landing” (Healey, Citation2011, Citation2013) of TPCs, that we are interested in. Landings are key episodes in the overall journeys of TPCs, and we will argue that their careful analysis helps reveal whether, how, and in what form traveling planning concepts appear in new destinations.

We take the landing of a TPC in a new context to be the process that culminates in the operationalization of a locally produced version of the concept, which is expected to generate sufficient desired outcomes and to maintain the support of relevant local communities (cf. Healey, Citation2013, pp. 1520–1521; Peck & Theodore, Citation2012, p. 24). How landing occurs, however, remains ambiguous in previous literature. While some authors acknowledge the complexity (a characteristic of the landing process) and the mutations that take place in the concepts during landing (a causal consequence of the complex landing process), very little analytical depth can be found in the study of this process. In some of the literature, it appears as if landing was a simple “importation”, “adoption”, or “translation” of existing concepts. We emphasize that this is not a single occurrence but an iterative process, and it is during this often extended process that TPCs become adjusted to the context of landing and gain their shape. To understand the complexity and scope of this process and how adjustments during it may make concepts distinct from those in other places, we raise the following research questions: How does TPC landing take place? How does the landing process affect TPCs?

To precisely conceptualize and analyze the landing process, we propose a multidimensional framework that enables a systematic analysis of the process of TPC landing over time. We apply this framework in an empirical study of the landing of the innovation district (ID) concept in Medellín, Colombia’s second-largest city. This concept, originating in advanced innovation-driven economies, was adopted in the developing country context to support Medellín’s transformation from its traditional manufacturing basis toward a “knowledge-based economy” after years of economic downturn and devastation as a narco-warzone. In this case, the environment of TPC landing differs profoundly from its origins, which helps reveal the influence of landing on the TPC.

IDs embody the policy trends of innovation-led urban economic development and the planning of knowledge-intensive urban economic spaces (e.g. Hutton, Citation2004). They are urban areas with mixed land use that serve as hubs for business, research, and education and facilitate access to diverse advanced resources through proximate interactions with actors in different sectors (Katz & Wagner, Citation2014). They are also strongly externally connected through extended networks (cf. Monardo, Citation2018, p. 331). They are planned to provide high-quality urban environments, housing, services, street life, and leisure activities for the workforce in innovative firms, start-ups, research institutes, etc. (Blakely & Hu, Citation2019; Esmaeilpoorarabi et al., Citation2020b; Katz & Wagner, Citation2014). High hopes for revitalizing inner cities and creating jobs have been placed in IDs (Esmaeilpoorarabi et al., Citation2020b; Katz & Wagner, Citation2014). However, doubts have been raised about their capacity to generate public engagement and benefits for adjacent neighborhoods and the broader economy (Arenas et al., Citation2020; Esmaeilpoorarabi et al., Citation2020a, p. 10; Heaphy & Wiig, Citation2020).

Further concerns have been expressed about IDs disproportionally privileging investors and technology firms (Gómez, Citation2022) and thereby engendering segregation and gentrification, particularly in cities of the global South (Goicoechea, Citation2014, Citation2018; Lederman, Citation2020). Regardless, this concept diffuses to destinations worldwide due to imaginaries of “world-class urbanism” involving the appealing rhetoric of socially inclusive creative processes in urban economic activities, which is advocated in transnational circuits diffusing international “best practices” (e.g. Bertelli, Citation2021; Lederman, Citation2020).

Our analysis is structured as follows. We provide a brief overview of the literature on TPCs, with support from the literature on PM, and propose a multidimensional framework that captures the elements of TPC landing processes. We then introduce our data and methods, Medellín, and report our qualitative analysis of the Medellín ID landing process. Subsequently, we discuss the usefulness of the multidimensional framework in generating novel insight into landing as a causal process and into the evolution of TPCs during landing. We conclude by suggesting that this approach helps pin down the mechanisms that make both the process and the version of the TPC it produces unique. This study thus contributes by offering a more thorough analysis of the causal process of TPC landing than what is found in the earlier literature.

A multidimensional framework for analyzing TPC landing

The vaguely theorized landing process

Of the two lines of research on mobilities that inform our analysis, the first, which focuses on TPCs, draws on eclectic sources to provide a critical analysis of the transnational flows of planning ideas and practices (Healey, Citation2013; Healey & Upton, Citation2010). The second, which focuses on PM, analyzes mobile policies, their mutations (Peck & Theodore, Citation2010a) and assemblages (e.g. McCann & Ward, Citation2012, Citation2013) and is often concerned with the spread of neoliberal policies (Peck & Theodore, Citation2001) from a structuralist perspective (Healey, Citation2013, pp. 1519–1520). The former is informed by the latter (see Healey, Citation2013), but the reverse is not the case (cf. Cook, Citation2015, p. 836; Jacobs, Citation2012, p. 413), and the literature on PM seems to subsume TPCs without distinguishing them as planning solutions (e.g. McCann, Citation2011). Despite differences in predispositions, these studies share an interest in the phenomenon of traveling/mobile planning/policy concepts/ideas that are spread by various carriers, adopted around the world, and adapted to local circumstances while maintaining a relation with extralocal actors and developments. In practice, planning and policy ideas and concepts often travel together and influence each other. We recognize that the traveling objects are frequently hybrids. They constitute elements in locally emerging “assemblages” of planning and policy practices, actors, and institutions (cf. e.g. Healey, Citation2013, pp. 1514, 1516; McCann & Ward, Citation2012, Citation2013; Ong & Collier, Citation2005; Prince, Citation2010). In this study, we place more emphasis on TPCs because the traveling concept we study, the ID, centrally involves an urban planning aspect.

Concepts are often sourced from leading cities in advanced economies (Yigitcanlar et al., Citation2008) but can also originate from cities in the global South (Montero, Citation2017; Wood, Citation2015a) or be combined from disparate origins (e.g. Bertelli, Citation2021; Bunnell, Citation2015; Robinson, Citation2015). A key observation in the literature is that concepts and policies change as they cannot be replicated identically in new contexts. Change occurs when concepts become entangled in context-specific social interactions and reciprocally transformative urban processes (Healey, Citation2013) or when policies are “translated and re-embedded within and between different institutional, economic and political contexts” (Peck & Theodore, Citation2001, p. 427). Through adaptation in place-specific social processes, the locally adjusted version of the concept may become idiosyncratic. In addition, the literature recognizes the role of local political processes resulting in specific coalitions’ interests being served (cf. Temenos & McCann, Citation2012). Systematic conceptualization and analytical precision are needed to understand how all of this happens (cf. McCann, Citation2011, p. 111).

The literature provides versatile conceptualizations to capture what is at stake when external concepts and ideas arrive in new places, but the process of TPC landing remains vague or only partially discussed. Often, rich empirical narratives of actual landing processes are accompanied by narrow – that is, partial and therefore weak – conceptual frameworks, emphasizing specific aspects of the process. This results in excluding other aspects and their interrelations. The aspects that are identified – albeit often in passing – include translation (e.g. Bertelli, Citation2021; Healey, Citation2013; Müller, Citation2015; Peck & Theodore, Citation2001), legitimation (e.g. Goicoechea, Citation2014; McCann, Citation2011), governance (e.g. Prince, Citation2012; Ward, Citation2018), politics (e.g. Prince, Citation2010; Temenos & McCann, Citation2012, pp. 1390–1401), embeddedness in territorially constituted social relations (McCann & Ward, Citation2010, p. 180), cities’ planning policies (McCann & Ward, Citation2010, p. 181), organizational structures and policies (cf. Borén et al., Citation2020, p. 253), and adherence to local assemblages (e.g. Healey, Citation2013, p. 1514; McCann & Ward, Citation2012, p. 328). Instead of focusing on such ad hoc, partial, and isolated aspects of the phenomenon, we propose a multidimensional framework that supports a comprehensive analysis of the landing process. This framework helps account for the process’s constitutive causal elements, the range of actors representing different voices in urban society, and the ways in which the process changes TPCs.

A multidimensional process

Our multidimensional framework identifies key activities involved in producing the landing process. The activities recur successively or simultaneously and coevolve. They represent five dimensions of the TPC landing process. Some of them are discussed ad hoc in the TPC and/or PM literature. Others were inferred during our data collection and early analysis.

We propose introduction as the first dimension of the TPC landing process. The introduction involves the identification of a planning concept by referring to a model case or an idea circulating among planning professionals and presenting it as an applicable model in a given local context. The initial introduction gives a rough idea of a desired solution to some local issues. As landing ensues, learning about the possibilities of the concept and local needs occurs, and the concept or aspects of it may need revision and reintroduction in a more specific or new form. Thus, while for Wood (Citation2015b), introduction refers to persistent failed attempts at gaining approval for a given concept preceding its eventual adoption, for us, introduction is a dimension of a landing process that recurs as new elements are adjoined to the TPC.

Our second dimension, translation, is discussed inconsistently in the literature. Translation takes place in international circuits of planning knowledge (Healey, Citation2013; cf. Ward, Citation2018); it is understood as “the processes through which an idea or technique moves from one site to another” (Healey, Citation2013, p. 1516; citing Callon et al., Citation2009); as the work related to concept mobility and the add-ons involved in those processes (Jacobs, Citation2012, p. 418); or as the entire landing process, as “[t]he ‘translation experiences’ through which exogenous planning ideas and practices become ‘localized’” (Healey, Citation2013, p. 1520; cf. Bertelli, Citation2021; Cochrane & Ward, Citation2012, p. 9). Translation has even been specified as the impact of mobile policy adoption on the landing site (Müller, Citation2015, p. 192).

Boxenbaum and Battilana (Citation2005) understand the translation of managerial practices as “adapting a foreign practice to own institutional context” (p. 356). Similarly in our analysis, translations reflect the necessity to adjust concepts to local urban and social structures, public and private capabilities, the interests and needs of inhabitants, and existing policy and planning assemblages (cf. McCann & Ward, Citation2013; Prince, Citation2010). More precisely, translation is the form and function given to a TPC as it is adapted to the specific circumstances of a new place. It involves selecting aspects of a concept (and thus rejecting, reframing, or modifying others) or adding new elements. Translation evolves as new features, associations of multiple understandings, influences of changing circumstances, and precision are instilled in the concept. Several rounds of translation are likely required before the concept is fully tailored to a new site.

Our third dimension, legitimation, ensures that actions are “desirable, proper, or appropriate” in a social context at a particular time (cf. Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). This is a prerequisite for gaining resources and support in the surrounding institutional environment (Scott & Meyer, Citation1992, p. 140). Legitimation is critical for TPCs sourced from divergent institutional environments. The TPC/PM literature notes the need to locally legitimize planning/policy action (e.g. Healey, Citation2013, pp. 1518–1521; McCann, Citation2003, p. 162, Citation2011, p. 119) and urban experiments, policies, and planning concepts (López & Montero, Citation2018; Montero, Citation2017; Prince, Citation2012; Sorensen, Citation2010, p. 118, 135). Here, legitimation as a dimension of landing helps focus systematically on the role of diverse acts of legitimization throughout landing processes. Legitimation is an interactive process requiring consensus building within organizational fields (Suddaby et al., Citation2017, pp. 451–452). Legitimation strategies vary depending on the stakeholders involved, the audiences targeted, the nature of the support sought, and the stage of the process. New landing developments create a recurrent need to persuade key stakeholders and the public of the appropriateness of adopting and translating a given concept or idea. Failing to legitimize an intended TPC among relevant audiences may provoke contestation against the concept and the coalitions involved.

In our fourth dimension, governance, TPC landing is enmeshed in interactions, negotiations and power relations that influence the assumptions and expectations adhered to TPCs (cf. Dzudzek & Lindner, Citation2015; Healey, Citation2013, p. 1523). These collective processes are coordinated through networks and partnerships between local governments and various stakeholders controlling critical resources (e.g. Pierre, Citation2014, p. 874). Due to the involvement of multiple actors, agendas, and rationalities, the processes remain in flux and are vulnerable (cf. Beunen et al., Citation2015). Powerful agents may influence decision-making, change the scope of the TPC or jeopardize the landing. Changing circumstances during landing may emanate new relationships and require adjustments to the TPC to maintain the interests and commitment of old and new coalition members.

Finally, our fifth dimension, materialization, involves the tangible outcomes of the progression of TPC landing. Materialization is rarely addressed explicitly in the TPC or PM literature, although most studies consider successful planning projects or policies, that is, ones that have materialized. Some authors studying unfinished policies consider them failures (Stein et al., Citation2017, p. 45). We suggest that seeing materialization as one of the evolving dimensions of landing makes all materializations (whether complete, incomplete, or failed) crucial in explaining the progression and outcomes of landing processes. Materializations may be partial, occur sporadically, and generate unintended outcomes (cf. Wood, Citation2015b). However, they coevolve with the other dimensions and recur in different forms. Materializations may concern the built environment, organizations, plans, etc. Each materialization epitomizes what can possibly be achieved in the landing process at a given time.

The progression of landing

The landing process unfolds through phases, that is, temporal brackets that occur sequentially over time and serve as comparative units of analysis. The phases comprise progressions of activities and events, separated by discontinuities in the temporal flow. Temporal bracketing allows for examining causality in a process and how developments in the previous phases change the context and impact subsequent phases. (Langley et al., Citation2013, p. 7) It assists in identifying mechanisms that explain the progression of the process (cf. Tsoukas, Citation1989; Van de Ven & Poole, Citation2005).

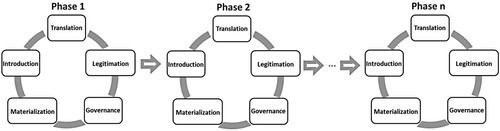

The phases of a landing process are qualitatively different, as the activities along the theoretically identified dimensions differ. Through the coevolution of the activities along the various dimensions in each phase, conditions are generated for the following phase. Therefore, in each phase, the rationales and forms of action tackle new issues, solve different problems, and give rise to different effects. Each phase evinces the progression of TPC landing. This process can be discussed in terms of mechanisms. Explanatory mechanisms are multilevel (Machamer et al., Citation2000): higher-level mechanisms can be explained by lower-level mechanisms. In TPC landing, diverse activities on the proposed dimensions recurring during the process constitute the lower-level mechanisms ().

Jointly, the lower-level mechanisms constitute phase-specific higher-level mechanisms that generate discontinuities or critical events that distinguish the phases and contribute to the causal process of landing.

We apply this framework in the analysis of the landing of the ID concept in Medellín.

The landing of the innovation district concept in Medellín

Data and methods

Qualitative analysis enables the uncovering of the subtle dynamics of the ID landing process. The primary data stem from on-site observations and 27 semi-structured interviews (24 were conducted in Medellín in September 2016 and November 2017, and three in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in April 2017). The interviewees () represented the views of five interest groups: public and private organizations involved in the ID landing and/or liaison officers working with the neighboring or business communities on ID planning and innovation projects. Secondary data on the evolving ID and contextual conditions during the landing process consist of planning documents and public reports, mostly available on the internet.

Table 1. Interviewees.

The interview data were recorded, transcribed, and thematically coded using NVivo software. The codes corresponded to the dimensions of the TPC landing process. The content analysis focused on the activities carried out by key agents and their interconnections. Some interviewees provided contrasting narratives regarding the role and the focus of the ID, but through data triangulation, we aimed at a neutral account.

The context of ID landing

Medellín, the provincial capital of Antioquia, is a long-standing economic hub in Colombia. Initially a producer of coffee and raw materials, the city transformed into the country’s industrial capital by the 1970s. It then lost competitiveness in key sectors (textiles, processed food, chemicals) and declined radically for two decades while at the same time receiving a rural migration influx that nearly tripled the population. The ensuing high unemployment (ca. 60%), and precarious urban conditions provided fertile ground for a drug trafficking boom (Departamento Nacional de Planeación, Citation1991, p. 5). The city was shattered under decades of narcotraffic, economic recession, fragmented development, inequality, violence, and weak government institutions.

Change gradually started to occur in the 1990s (Promo2; Pub1; cf. Betancur & Brand, Citation2021, pp. 18–19). The local institutional capacity improved with local democracy (popular mayoral elections since 1988), decentralization (increased administrative and financial responsibilities and competences), and support from the national government and international organizations. Solutions to Medellín’s social problems were sought through new modes of governance, including broad collaboration with community leaders, civil society, academics, and the private sector (Betancur & Brand, Citation2021, p. 8; Pub1). An ideological turn was apparent in the approaches to tackling violence, inequality, and economic growth (Ferrari et al., Citation2018),Footnote1 reflected in the development plans of the Mayors’ office that subsequently guided the city’s economic development (Dolan, Citation2020, p. 117; Leyva, Citation2010). The ID concept underscoring urban regeneration was sourced from abroad.

Analysis of the ID landing process in Medellín

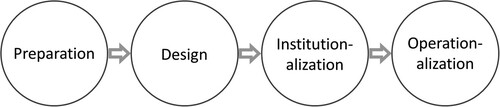

We analyze the progression of the landing through four qualitatively distinct phases that we identified while handling the raw data. The start and end of each phase are not marked by a definite date but a year during which a new type of dynamism started to emerge. This is indicated in the variation in the activities along the five dimensions from phase to phase. presents the scheme for our data analysis and summarizes the main results.

Table 2. The landing of the Medellín Innovation district 2008–2017.

We analyze the landing process through a narrative as follows.

SEARCH: setting the stage for the ID landing (2008–2011)

The local government’s quest to implement effective urban economic development initiatives set the stage for the ID landing process. With mounting unemployment, the city’s development plan for 2008–2011 introduced a flagship building project to support entrepreneurship (Alcaldía de Medellín & Salazar Jaramillo, Citation2008). Public intervention in terms of “an entrepreneurial block” would contribute to the renovation of the surrounding decaying neighborhoods in an economically strategic area near the city center, adjacent to leading universities, a university hospital, significant cultural and recreational facilities, and along the city’s main metro line (RN6).

To define this project, the Mayor’s Office commissioned a multidisciplinary team of professionals from local government agencies, public enterprises, and universities (RN6). Through planning tourism, the team benchmarked urban planning models in advanced cities, including Boston, Barcelona, Madrid, and Singapore, as well as cities in Chile, Argentina, and Brazil (Ruta N, Citationn.d.). They found entrepreneurship increasingly considered in the context of the knowledge-based economy and agreed that the building plan intended to support entrepreneurship should now more broadly promote science, technology, and innovation (STI) activities (RN6). This new way of thinking was translated to support the city’s knowledge-based transformation.

The redefined building was expected to benefit a broader set of local stakeholders and to support key ongoing urban agendas, including education and entrepreneurship, which had been the main pillars in overcoming the crisis in Medellín since 1991. These agendas were supported by established urban coalitions where public, private, and civil society organizations collaborated to create social opportunities (Pub1). The STI elements were expected to facilitate the diffusion of innovation activities in the city (Alcaldía de Medellín & Salazar Jaramillo, Citation2011, p. 66), educate high-skilled labor, and provide support for “the new economy” (RN4).

As a hub for innovation activities, the planned building would epitomize the city’s STI agenda advocated since 2003. This agenda was steered by the triple-helix strategic alliance CUEE (Leyva, Citation2010; Morales-Gualdrón et al., Citation2015, p. 141), comprising top decision-makers from powerful local conglomerates, main universities, the Governor’s and Mayor’s offices, and directors of relevant national and regional organizations (Ramírez Salazar & García Valderrama, Citation2010; Uni2). CUEE endorsement conferred broadly based support in legitimizing the planned building (Uni2).

Finally, the plan resonated with the internationalization and branding agendas of the city: promoting business tourism through international events (i.e. the Annual Board of Governors of the Inter-American Development Bank, 2009; the General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS), 2008) and showcasing the city’s social innovations to top leaders (cf. Brand & Dávila, Citation2011; Promo2; RN6). Renowned social innovations are a key element of the city’s brand (Doyle, Citation2019; Hernandez-Garcia, Citation2013). They connect Medellín’s informal settlements to urban public infrastructure networks via significant urban and architectural landmark interventions such as metrocables, escalators, architecturally prominent public libraries, cultural centers, and schools (Dolan, Citation2020; McQuirk, Citation2012). These social innovations have contributed to the city’s modern image and encouraged foreign investments (Dolan, Citation2020, p. 124).

Combined, the different urban agendas advanced Medellín’s internationalization. For instance, having participated in the 2008 OAS General Assembly, the U.S. Secretary of State Rice referred Hewlett & Packard’s (HP) management to the city’s potential. In 2010, HP established its Regional Development Center in the city. The entry of a prominent foreign multinational in Medellín was taken to be a result of the well-defined STI strategy, including the building plan (Promo1; Promo3; RN6), with funding guaranteed by the municipality and publicly owned corporations (EPM, utilities; UNE, telecommunications). As observed, “At that precise moment in history, the services it [HP] brought and the bet we wanted to make at STI – it was a perfect match” (RN6).

This large foreign investment was seen as legitimizing the city’s STI-motivated building plan and the concerted efforts of the broad urban coalitions supporting it. HP entry also fast-tracked the new building construction and received additional support as the EAFIT university built an extra floor in a campus building to temporarily host HP to ensure its entry. (Promo1; Promo3; RN6)

The search phase materialized, first, in the 2009 establishment of the Ruta N Corporation, a nonprofit public organization dedicated to STI activities (Alcaldía de Medellín & Salazar Jaramillo, Citation2011, p. 87) and second, in the 2011 completion of an architecturally notorious and internationally certified green building for the Ruta N Innovation and Business Centre (Ruta N, Citation2018; we will refer both to the organization and the building as Ruta N in what follows). The former managed the latter. Ruta N signaled the “new North” of Medellín’s knowledge-based transformation (RN6). After Ruta N was built, other technology firms started to flow in (Gómez, Citation2022).

The search process and the efficient build-up of Ruta N stemmed from the governance arrangements and the interlocking urban coalitions behind Ruta N. As members of the local elite, they represented various key stakeholders in the city (the public sector and the local private and semipublic conglomerates), enabling them to coordinate broad administrative and material resources in the city (cf. MIT1; Promo1; RN6). The city’s persisting social and economic problems triggered a strongly felt social transformation ethos within what we call a developmental ecosystem, a loosely coupled but broadly based constellation of resourceful decision-makers for whom the development opportunities offered by Ruta N in the nonaffluent neighborhood complemented the city’s optimistic development trajectory. This governance arrangement, however, allowed private influence on public policy and developmental outcomes (cf. Betancur & Brand, Citation2021, p. 19; Franz, Citation2018, pp. 94–95).

VISION: an innovation district (2011–2013)

In this phase, the idea of a significant building supporting STI development obtained a concept definition: the ID concept that was introduced during an informal visit by a team of MIT architects. The Ruta N team presented the visitors with plans to support the transformation of the city to a knowledge economy. The MIT team identified these as “the kind of thing that we are working on, that’s called an innovation district” (RN1).

To fit the circumstances in Medellín, the ID concept was translated into a socially inclusive ID model, with the aim of also creating synergies with the (partly informal) low-tech businesses predominant in the low-income neighborhoods surrounding Ruta N. Unlike the prevalent ID models in innovation-driven economies, the Medellín ID was designed to serve as a platform to initiate a local innovation ecosystem (Ind7; RN3). The model had to benefit two disparate communities. On the one hand, a complete transformation of the area into a “world-class” urban environment was supposedly required for the entrepreneurs, managers, and employees of the growing number of technology firms (RN5). On the other hand, a full transformation would hurt the livelihoods of the neighboring low-income landowners, residents, and firm owners (RN2; RN3). The solution was seen in an incrementally growing, socially inclusive ID involving small-scale entrepreneurs and landowners in diverse economic activities (Ratti & Frenchman, Citation2012; RN2). As stated, “In the 21-century idea of innovation, you do not need big footprints. You need small enterprises to develop side by side in smaller blocks, the size of a house” (MIT1).

The tailoring of the Medellín ID set it apart from the benchmarked IDs and helped build legitimacy among stakeholders. The model was developed with foreign advisors. Barcelona shared its experiences in developing the renowned local government driven 22@ district (RN1; Ruta N, Citation2013a; cf. e.g. González, Citation2011). To complement that knowledge, the academic team from MIT with associated consultants (Carlo Ratti Associati, Mobility in Chain, and Accenture) was hired to develop a strategic plan for the Medellín ID (RN1; Ruta N, Citation2013b). Additionally, a social enterprise accelerator from Buenos Aires consulted on developing transformative business models and living labs to support the socioeconomic inclusion of neighboring residents and to create synergies with technological entrepreneurs (RN2; RN3). The planning process also included the participation of local experts, representatives of private and public sectors, and the neighboring communities. This broad participation contributed to the transparency of the process (RN1; RN2).

The 2012 “Innovative City of the Year” title (Wall Street Journal, Citation2012), awarded for Medellín’s social innovations, helped further legitimize the chosen socially inclusive ID model and strengthen the image of a growing innovation culture. Prizes awarded by transnational organizations help convince local stakeholders about the credibility of the pursued “world-class” ideals (Lederman, Citation2020, p. 106). The ID “added to the narrative of Medellín working in social issues, because [the ID area] is a poor area of the city” (MIT1). The title helped normalize the concept of a specialized area for innovation (RN4) “in a place where people were not necessarily acquainted with the idea of innovation” (RN4).

The materialization in this phase was the Medellinnovation District strategic plan (MID) (Ratti & Frenchman, Citation2012). It extended the intended redevelopment area around Ruta N from 16 hectares (Alcaldía de Medellín & Gaviria Correa, Citation2012, p. 113) to 196 hectares (Ratti & Frenchman, Citation2012, p. 102). Ruta N became central in the governance of the ID landing. It received a mandate to lead this process supported by a board of directors with a high-ranking representation from the local government as well as public and private local conglomerates (RN1). Ruta N built consensus among diverse local stakeholders in the participative planning process envisioning the ID and the role that different parties could play in it (RN2).

PLAN: formalization of the ID (2013–2017)

The MID was introduced as the basis for the formalization of the urban planning and implementation instruments. These instruments gave rise to the technical translations of the ID. An urban plan was crafted according to the goals set in the MID and in compliance with the national planning legislation (RN1). National legislation curtailed the bold vision of the ID, however, as no legal standards existed for an area dedicated to innovation activities. The area was therefore categorized as “urban renewal”, normally used for large land units developed by the private sector. This categorization required landowners or developers to provide urban infrastructure and social upgrading, an expensive option (RN1; RN2). Additionally, it prevented an intended key feature of MID, namely, its incremental (plot-by-plot) development “rather than wholesale clearance” of the area (Ratti & Frenchman, Citation2012, p. 25; cf. MIT1). The partial plan for the area allowed the development of mid-sized land units, but that required 51% approval of sometimes up to 20 landowners (RN1). This slowed down development and made the area less attractive for private investors (RN1).

The alignment of the ID with formal statutes and local stakeholder interests contributed to its legitimacy. Business models were crafted to address a major challenge set by the MID: the generation of opportunities for the neighboring communities. A dedicated team at Ruta N worked with these communities to enhance their absorptive capacity and competences as well as to form synergies between formal and informal businesses, create institutional ties, and open experimental spaces (Morisson & Bevilacqua, Citation2019, p. 3; RN3). Additionally, the 7th UN-Habitat Conference held in Medellín in 2014 contributed to the legitimation of the city’s development model, including the ID. The presence of 23,000 representatives of the international planning community and their recognition of Medellín’s “bold vision of social urbanism” that went beyond physical development to a commitment to social inclusion and equality (Turok, Citation2014, p. 575).

The planned ID involved new actors in governance, and Ruta N worked toward building consensus among them. The decision-making process and ID implementation necessitated an organization able to both manage construction and support socioeconomic development and innovation. An organizational model that established a division of labor between the municipality (overall operation of the ID), the public Urban Development Enterprise (physical infrastructure), and Ruta N (socioeconomic development and innovation) was designed in consultation with the World Bank. (RN1)

The materialization in this phase comprised the inclusion of the ID in the Territorial Ordinance Plan (Alcaldía de Medellín, Citation2014), i.e. it was written into planning legislation. The approval of the plan granted the necessary conditions for realizing the ID and established legal bases for further development. The ID was foreseen as the most significant concentration of STI activities in Medellín (Distrito de Innovación Medellín, Citationn.d.) and the consolidation of the local innovation ecosystem within approximately a million square meters to be developed in the subsequent 12 years (RN1; RN4).

MISSION: the Medellín ID model (2017–)

After the formal planning phase, the implementation of the ID officially started in 2017, although the Ruta N building had already been fulfilling many functions of an ID since 2011. By 2016, it had hosted 143 technology firms from 22 foreign countries as well as domestic ones. Such a concentration of foreign technology firms made the Medellín ID stand out in Latin America (RN4).

Investing in the ID area was cumbersome and costly. Small landowners lacked the money, capacity, and incentives to initiate building projects. Ruta N had the mandate to develop the area but lacked the resources to buy land or build (RN1; RN3). The technology firms had no interest in office ownership or in developing the ID territory. Their demand for fully serviced office spaces attracted international operators to set up coworking spaces in the more affluent business district in the south of the city, endowed with urban amenities and safety and ensuring higher returns on investment (RN1). Thus, the location of the ID was problematic, as observed,

It is there because it is a political decision, not because it is the best place to put the district. […] [H]ere you are not dealing with the people who are interested in this thing. (MIT1)

Until the mission phase, the ID landing had the support of all power holders in the city, and Ruta N could use its mandate to make progress. Then, the volatility of urban governance processes became apparent. Having been founded by earlier administrations, by 2015, the ID no longer was a key priority. The new local government shifted its focus to other urban agendas, leaving the district to market forces (RN1). After their maximum two-year tenure at Ruta N, technology firms relocated to other areas as the district offered no other options. Investors were interested in more lucrative projects. The lack of private and limited public investments in the ID undermined its rapid development and started to erode its legitimacy.

Legitimacy for the ID among neighboring communities was sought by maintaining inclusive development as a driving principle of the ID (RN3). However, it has not been easy to unite disparate worlds. The technology and business communities had little interest in the area, and the implementation of the socioeconomic inclusion plans depended on funds acquired by developing the built environment (RN2). Persistent attempts have been made to create synergies between the communities and to expose residents to the latest technologies, albeit on a small scale (Morisson & Bevilacqua, Citation2019; RN2). Despite good intentions, interactions with nearby communities have been rare, and Ruta N has been perceived as an isolated island of innovation in the district (Arenas et al., Citation2020). In general, urban social innovations have not helped eradicate poverty and inequality in the city (cf. Brand, Citation2013; Franz, Citation2017, Citation2018). The local conglomerates that supported the ID since the beginning see value in its overall development, but within limits: they “do not want to think about it as a social project, and they control the political backing” (MIT1).

In this phase, one large building infrastructure with innovation potential was planned in the ID, the University of Antioquia’s “City of Health” campus. Lacking private investors, other major building plans have failed to materialize. While the development of the designated ID area became slow and uncertain, the ID was seen as progressing because a budding urban innovation culture was maintained by diverse initiatives around the city. Ruta N was a strategic partner and a broker in the nascent networked ID model, supporting different innovative initiatives and coworking spaces around the city. Its strategy became “to navigate in the medium term [and] prove to the city that this is going to work” (RN1). Ruta N consolidated what had materialized thus far: an emerging networked ID model with Ruta N as its hub. It helped develop the city’s overall innovation ecosystem and at the same time advanced the original ID plan, insisting “We have to keep the flame on during this administration and try to engage the next one” (RN1).

Discussion

The Medellín ID provides an instructive case for the study of TPC landing, as the ID concept was drastically shaped during the landing process to fit the local conditions. At the same time, this case representatively demonstrated the complexity of landing, manifested in several qualitatively distinct phases. Our conceptual framework enabled us to unravel more systematically and comprehensively than has been done in previous literature how the landing of TPCs takes place and how they are shaped through the process.

The analysis of the ID landing process in Medellín in terms of multidimensional and multilevel mechanisms demonstrates the relevance of the framework in the advancement of theory building on TPC landing. It revealed the structure of the causal process of landing. Five categories of lower-level mechanisms generate the dynamics in the process. Throughout the phases, (1) introduction draws stakeholders’ attention to a solution to issues relevant in the phase, an initial planning concept and subsequent specifications; (2) translation changes what is introduced so that it is suited to the contextual circumstances; (3) legitimization ensures support among stakeholders who control relevant resources under those circumstances; (4) governance processes create sufficient coordination on pressing issues within and among the coalitions involved and address potential contestation; and (5) materialization ultimately epitomizes the concrete achievable outcomes in each phase. Jointly, the lower-level mechanisms in each phase constitute the higher-level mechanisms that generate the unique progression of landing. In the Medellín ID case, the first phase (“search” in our empirical narrative) prepared the ground for the landing, the second (“vision”) produced the design for the district, the third (“plan”) institutionalized the formal plan, and the fourth (“mission”) operationalized a distinctive ID model () and brought the landing process to a conclusion.

The detailed contextual analysis of the landing process also helps avoid the pitfalls of missing out on some of the causal factors contributing to the process or providing partial explanations for the landing. The latter can result from referring to only some of the dimensions or prematurely identifying an intermediate materialization (or lack thereof) as the ultimate outcome of a landing process, as was observed in the literature.

Existing literature on TPCs and PM suggests that mobile ideas and concepts do not come alone but are integrated into assemblages of planning and policy practices, actors, and institutions. This suggests that TPC landing often takes place in the context of a set of other urban development goals, possibly benefiting from them and facilitating their implementation. In Medellín, we observed how the ID landed interwoven with the idea of the knowledge economy and was adjusted to fit a broader assemblage of socioeconomic development agendas in place in the city. Additionally, add-ons (mobile concepts or ideas in their own right) may supplement and modify the original concept to suit the landing site. In Medellín, add-ons were sourced from international agencies and advanced economies as well as cities more comparable to Medellín. Contrary to Jacobs (Citation2006, p. 13; Citation2012, p. 418), for whom add-ons are any changes that are made to an original concept in a translation (as in, say, changing the color of a passenger car or adding another gear; it still carries people from a to z), we propose that they are modules that extend the form and function of the TPC (like a caravan extends the form and function of a passenger car). Add-ons are amalgamated as modular components in focal TPCs and can help adjust and legitimize them.

The ID landing was set in motion by an intention to bring in an externally originating concept to solve local problems. It was progressively shaped during the landing process. The proximate cross-sector interactions associated with the standard internationally traveling ID concept (Katz & Wagner, Citation2014) and the locally designed socially inclusive model have only developed on a small scale in the designated area. While Arenas et al. (Citation2020) understood the limited development of the ID as a landing failure, in our interpretation, the ID actually developed capitalizing on the dynamics set in motion under the specific circumstances of landing. In those circumstances, the plans for the area were challenged by twofold institutional inertia: national legislation prevented incremental land development, and prevailing business practices discouraged involvement and investments in the low-income neighborhoods. However, fueled by the ID landing, small nodes of innovation activities emerged elsewhere in the city and, in coordination with Ruta N, gave rise to a city-wide network model, extending the prevailing ID concept. Without a thorough analysis of the landing process enabling the identification of diverse stakeholders in the entire city, the network model could have gone unnoticed. This model does not prevent the more comprehensive development of the originally designated area in times to come.

Conclusion

Landings are key episodes in the travels of TPCs. Our study is the first attempt at conceptualizing the overall structure of TPC landing as a multidimensional iterative process that begins when an externally originating concept is sought to solve local problems and ends in its local operationalization. The process approach facilitates a detailed analysis of the progression of TPC landing through successive phases driven by multilevel mechanisms and reveals the factors that influence the evolution of the concept during the process.

In Medellín, the ID concept originally suited the aspirations of a city striving toward economic revival by advancing its knowledge-based economy. The mismatch between the globally traveling concept, advocating urban regeneration and support for the highly skilled, and the realities of the local circumstances in a primarily poor area of the city made it necessary to add other concepts and policy ideas and create new features in the Medellín ID model. These add-ons helped create legitimacy but also rendered the landing process arduous. Thus far, it has resulted in an alternative ID model, one that was possible and that the local coalitions managed to implement given the happenstances of the process. Undeniably, the ID has not boosted radical change in the designated neighborhoods, but neither has it exacerbated gentrification as witnessed in other cities of the global South (cf. Goicoechea, Citation2014, Citation2018; Lederman, Citation2020).

The advancement of the TPC model was contingent upon the limits set by the environment: the resource constraints, the interests and agendas of the parties involved, and the notorious need to find solutions to the conundrums in urban development. The idiosyncratic landing process that took place in challenging circumstances produced a distinctive ID model. Thus, established TPCs may be modified and transformed into qualitatively new kinds, generating diversity among TPCs. These may start new rounds of circulation, making smoother landings in similar institutional environments elsewhere (cf. Temenos & McCann, Citation2013), avoiding imaginaries of “world-class urbanism” that remain disengaged from the context (cf. Lederman, Citation2020).

Complementing the literature on TPCs and PM, this systematic analysis of the landing process of the ID concept in Medellín suggests that the specifics of the landing process are the key to understanding whether, how, and in what form a given TPC appears in a particular place. Detailed comparative analyses on landings are needed in the future to capture the diversity of such processes and their transformative power on mobile concepts and the places that adopt them. Another issue for further consideration is whether it is possible to identify types of landings supportive of specific types of concepts and localities and even identify landings as another kind of entity that could travel. Finally, our analysis was limited to studying TPC landing, not its effects on the destination city. Future analysis can draw conclusions about the wiseness of Medellín in adopting this particular TPC concept.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These approaches included a Barcelona-inspired model of social urbanism in the policy discourse (Brand, Citation2013, p. 3) emphasizing inclusion, education, culture, entrepreneurship, and social coexistence as drivers of social development (Dolan, Citation2020; Sotomayor, Citation2015), innovation and high technology advocated in economic policy as means of transforming the former industrial center into a hub in the “knowledge economy” (Promo1; RN6; Sánchez Jabba, Citation2013), and broadly publicized urban interventions in the poorest neighborhoods (Betancur & Brand, Citation2021, p. 2).

References

- Alcaldía de Medellín. (2014). Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial del Municipio de Medellín [Territorial organization plan of the municipality of Medellín].

- Alcaldía de Medellín, & Gaviria Correa, A. (2012). Proyecto de Acuerdo Plan de Desarrollo “Medellín un hogar para la vida” 2012–2015 [Development plan draft agreement “Medellín a home for life” 2012–2015].

- Alcaldía de Medellín, & Salazar Jaramillo, A. (2008). Plan de desarrollo 2008–2011: Medellín es solidaria y competitiva [Development plan 2008–2011: Medellín is supportive and competitive].

- Alcaldía de Medellín, & Salazar Jaramillo, A. (2011). Informe final de gestión: “Plan de desarrollo 2008–2011” [Final management report: Development plan 2008–2011].

- Arenas, L., Atienza, M., & Vergara Perucich, J. F. (2020). Ruta N, an island of innovation in Medellín’s downtown. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 35(5), 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094220961054

- Bertelli, L. (2021). What kind of global city? Circulating policies for ‘slum’ upgrading in the making of world-class Buenos Aires. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(6), 1293–1313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X21996356

- Betancur, J. J., & Brand, P. (2021). Revisiting Medellín’s governance arrangement after the dust settled. Urban Affairs Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874211047938

- Beunen, R., Van Assche, K., & Duineveld, M. (2015). The search for evolutionary approaches to governance. In R. Beunen, K. Van Assche, & M. Duineveld (Eds.), Evolutionary governance theory (pp. 3–17). Springer.

- Blakely, E. J., & Hu, R. (2019). Crafting innovative places for Australia’s knowledge economy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Borén, T., Grzyś, P., & Young, C. (2020). Intra-urban connectedness, policy mobilities and creative city-making: National conservatism vs. urban (neo) liberalism. European Urban and Regional Studies, 27(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420913096

- Boxenbaum, E., & Battilana, J. (2005). Importation as innovation: Transposing managerial practices across fields. Strategic Organization, 3(4), 355–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127005058996

- Brand, P. (2013, September 9–11). Governing inequality in the south through the Barcelona model: “Social urbanism” in Medellín, Colombia [Paper presentation]. Interrogating urban crisis: Governance, contestation, critique conference, De Montfort University. https://www.dmu.ac.uk/documents/business-and-law-documents/research/lgru/peterbrand.pdf

- Brand, P., & Dávila, J. D. (2011). Mobility innovation at the urban margins: Medellín’s Metrocables. City, 15(6), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2011.609007

- Bunnell, T. (2015). Antecedent cities and inter-referencing effects: Learning from and extending beyond critiques of neoliberalisation. Urban Studies, 52(11), 1983–2000. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013505882

- Callon, M., Lascoumes, P., & Barthe, Y. (2009). Acting in an uncertain world: An essay on technical democracy. MIT Press.

- Cochrane, A., & Ward, K. (2012). Researching the geographies of policy mobility: Confronting the methodological challenges. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44176

- Cook, I. R. (2015). Policy mobilities and interdisciplinary engagement. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(4), 835–837. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12256

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación. (1991). Programa presidencial para Medellín y el área metropolitana [Presidential program for Medellín and the metropolitan area] (Documento 2562 DNP-UDS-DIPSE y P.P.M).

- Distrito de Innovación Medellín. (n.d.). Inicia etapa de sostenibilidad del macroproyecto distrito. Cómo vamos – Se aprueba el plan de ordenamiento territorial por medio del acuerdo municipal 048 de 2014. http://www.distritomedellin.org/como-vamos/

- Dolan, M. (2020). Radical responses: Architects and architecture in urban development as a response to violence in Medellín, Colombia. Space and Culture, 23(2), 106–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218770368

- Doyle, C. (2019). Social urbanism: Public policy and place brand. Journal of Place Management and Development, 12(3), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-01-2018-0006

- Dzudzek, I., & Lindner, P. (2015). Performing the creative-economy script: Contradicting urban rationalities at work. Regional Studies, 49(3), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.847272

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N., Yigitcanlar, T., Kamruzzaman, M., & Guaralda, M. (2020a). How does the public engage with innovation districts? Societal Impact Assessment of Australian Innovation Districts. Sustainable Cities and Society, 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101813

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N., Yigitcanlar, T., Kamruzzaman, M., & Guaralda, M. (2020b). How can an enhanced community engagement with innovation districts be established? Evidence from Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. Cities, 96, 102430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102430

- Ferrari, S. G., Smith, H., Coupe, F., & Rivera, H. (2018). City profile: Medellin. Cities, 74, 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.12.011

- Franz, T. (2017). Urban governance and economic development in Medellín. An “urban miracle”? Latin American Perspectives, 44(2), 52–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X16668313

- Franz, T. (2018). Power balances, transnational elites, and local economic governance: The political economy of development in Medellín. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 33(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094218755560

- Goicoechea, M. E. (2014). The city of Buenos Aires as the scope and purpose of business. Reflections around urban policy of the technology district in Parque Patricios. Quid 16: Revista del Área de Estudios Urbanos (4), 161–185.

- Goicoechea, M. E. (2018). Creative districts in the south of the City of Buenos Aires (2008–2015). Urban renewal and new logics of segregation. Quid 16: Revista del Área de Estudios Urbanos (9), 224–227.

- Gómez, L. (2022). MNEs and knowledge creation in Medellín’s emerging ICT hub. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. doi:[t.b.a.].

- González, S. (2011). Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in motion’. How urban regeneration ‘models’ travel and mutate in the global flows of policy tourism. Urban Studies, 48(7), 1397–1418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010374510

- Healey, P. (2010). Introduction. In P. Healey & R. Upton (Eds.), Crossing borders: International exchange and planning practices (pp. 1–25). Routledge.

- Healey, P. (2011). The universal and the contingent: Some reflections on the transnational flow of planning ideas and practices. Planning Theory, 11(2), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095211419333

- Healey, P. (2013). Circuits of knowledge and techniques: The transnational flow of planning ideas and practices. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1510–1526. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12044

- Healey, P., & Upton, R. (Eds.). (2010). Crossing borders: International exchange and planning practices. Routledge.

- Heaphy, L., & Wiig, A. (2020). The 21st century corporate town: The politics of planning innovation districts. Telematics and Informatics, 54, 101459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101459

- Hernandez-Garcia, J. (2013). Slum tourism, city branding and social urbanism: The case of Medellin, Colombia. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331311306122

- Hutton, T. A. (2004). The new economy of the inner city. Cities, 21(2), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2004.01.002

- Jacobs, J. M. (2006). A geography of big things. Cultural Geographies, 13(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1191/1474474006eu354oa

- Jacobs, J. M. (2012). Urban geographies I: Still thinking cities relationally. Progress in Human Geography, 36(3), 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511421715

- Katz, B., & Wagner, J. (2014). The rise of innovation districts: A new geography of innovation in America. Brookings Institute.

- Langley, A., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.4001

- Lederman, J. (2020). Chasing world-class urbanism: Global policy versus everyday survival in Buenos Aires. University of Minnesota Press.

- Leyva, S. (2010). El proceso de construcción de estatalidad local (1998–2009): ¿La clave para entender el cambio en Medellín? [The process of constructing local statehood (1998–2009): The key to understanding Medellín’s change?]. In M. Hermelin Arbaux, A. Echeverri Restrepo, & J. Giraldo Ramírez (Eds.), Medellín: medio ambiente, urbanismo y sociedad (pp. 271–293). Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT.

- López, O. S., & Montero, S. (2018). Expert-citizens: Producing and contesting sustainable mobility policy in Mexican cities. Journal of Transport Geography, 67, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.08.018

- Machamer, P., Darden, L., & Craver, C. F. (2000). Thinking about mechanisms. Philosophy of Science, 67(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1086/392759

- McCann, E. (2003). Framing space and time in the city: Urban policy and the politics of spatial and temporal scale. Journal of Urban Affairs, 25(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9906.t01-1-00004

- McCann, E. (2011). Urban policy mobilities and global circuits of knowledge: Toward a research agenda. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2010.520219

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2010). Relationality/territoriality: Toward a conceptualization of cities in the world. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.06.006

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2012). Policy assemblages, mobilities and mutations: Toward a multi-disciplinary conversation. Political Studies Review, 10(3), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00276.x

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2013). A multi-disciplinary approach to policy transfer research: Geographies, assemblages, mobilities and mutations. Policy Studies, 34(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2012.748563

- McQuirk, J. (2012, April 11). Colombia’s architectural tale of two cities. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/apr/11/colombia-architecture-bogota-medellin

- Monardo, B. (2018). Innovation districts as turbines of smart strategy policies in US and EU. Boston and Barcelona experience. In F. Calabrò, L. Della Spina, & C. Bevilacqua (Eds.), New metropolitan perspectives (pp. 322–335). Springer.

- Montero, S. (2017). Study tours and inter-city policy learning: Mobilizing Bogotá’s transportation policies in Guadalajara. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(2), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16669353

- Morales-Gualdrón, S. T., Gómez, G., & Suleny, A. (2015). Análisis de una innovación social: el Comité Universidad Empresa Estado del Departamento de Antioquia (Colombia) y su funcionamiento como mecanismo de interacción [Analysis of a social innovation: The enterprise state university committee of the department of Antioquia (Colombia) and its functioning as a mechanism of interaction]. Innovar, 25(56), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v25n56.48996

- Morisson, A., & Bevilacqua, C. (2019). Beyond innovation districts: The case of medellinnovation district. In F. Calabrò, L. Della Spina, & C. Bevilacqua (Eds.), New metropolitan perspectives: Local knowledge and innovation dynamics towards territory attractiveness through the implementation of Horizon/E2020/Agenda2030 (pp. 3–11). Springer.

- Müller, M. (2015). (Im-) mobile policies: Why sustainability went wrong in the 2014 Olympics in Sochi. European Urban and Regional Studies, 22(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414523801

- Ong, A., & Collier, S. J. (2005). Global assemblages: Technology, politics, and ethics as anthropological problems. Blackwell.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2001). Exporting workfare/importing welfare-to-work: Exploring the politics of third way policy transfer. Political Geography, 20(4), 427–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(00)00069-X

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010a). Mobilizing policy: Models, methods, and mutations. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.01.002

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010b). Recombinant workfare, across the Americas: Transnationalizing “fast” social policy. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.01.001

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2012). Follow the policy: A distended case approach. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44179

- Perera, N. (2010). When planning ideas land: Mahaweli’s people-centered approach. In P. Healey & R. Upton (Eds.), Crossing borders: International exchange and planning practices (pp. 141–172). Routledge.

- Pierre, J. (2014). Can urban regimes travel in time and space? Urban regime theory, urban governance theory, and comparative urban politics. Urban Affairs Review, 50(6), 864–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413518175

- Prince, R. (2010). Policy transfer as policy assemblage: Making policy for the creative industries. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(1), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4224

- Prince, R. (2012). Policy transfer, consultants and the geographies of governance. Progress in Human Geography, 36(2), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511417659

- Ramírez Salazar, M. D. P., & García Valderrama, M. (2010). La Alianza Universidad-Empresa-Estado: una estrategia para promover innovación [The University-Enterprise-State Alliance: A strategy to promote innovation]. Magazine School of Business Administration, 68, January–June.

- Ratti, C., & Frenchman, D. (2012). Transforming technologies, markets and the city. Medellinnovation district: Strategic plan (Report, Informe de proyecto de equipo de expertos del MIT para Ruta N). Ruta N.

- Robinson, J. (2015). ‘Arriving at’ urban policies: The topological spaces of urban policy mobility. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(4), 831–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12255

- Ruta N. (2013a). Un distrito tecnológico para la ciudad del conocimiento. Opinión. https://www.rutanmedellin.org/en/opini%C3%B3n/item/un-distrito-tecnologico-para-la-ciudad-del-conocimiento-15012019

- Ruta N. (2013b). Expertos del MIT aportan al sueño del distrito de innovación [Experts from MIT contribute to the innovation district dream]. Actualidad. https://www.rutanmedellin.org/es/actualidad/noticias/item/expertos-del-mit-aportan-al-sueno-del-distrito-de-innovacion-11

- Ruta N. (2018). We are the Innovation and Business Center of Medellín. About us. https://www.rutanmedellin.org/en/about-us.

- Ruta N. (n.d.). ¿Por qué nace Ruta N? [Why did Ruta N emerge?]. Inicio. https://www.rutanmedellin.org//es/¡Por qué nace Ruta N?

- Sánchez Jabba, A. (2013). La reinvención de Medellín [The reinvention of Medellín]. Lecturas de economía, 78, 185–227.

- Scott, W. R., & Meyer, J. W. (1992). The organization of societal sectors. In J. W. Meyer & W. R. Scott (Eds.), Organizational environments: Ritual and rationality (pp. 129–153). Sage.

- Sorensen, A. (2010). Urban sustainability and compact cities ideas in Japan: The diffusion, transformation and deployment of planning concepts. In P. Healey & R. Upton (Eds.), Crossing borders: International exchange and planning practices (pp. 141–164). Routledge.

- Sotomayor, L. (2015). Equitable planning through territories of exception: The contours of Medellin’s urban development projects. International Development Planning Review, 37(4), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2015.23

- Stein, C., Michel, B., Glasze, G., & Pütz, R. (2017). Learning from failed policy mobilities: Contradictions, resistances and unintended outcomes in the transfer of “business improvement districts” to Germany. European Urban and Regional Studies, 24(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776415596797

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Suddaby, R., Bitektine, A., & Haack, P. (2017). Legitimacy. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 451–478. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0101

- Temenos, C., & McCann, E. (2012). The local politics of policy mobility: Learning, persuasion, and the production of a municipal sustainability fix. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(6), 1389–1406. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44314

- Temenos, C., & McCann, E. (2013). Geographies of policy mobilities. Geography Compass, 7(5), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12063

- Tsoukas, H. (1989). The validity of idiographic research explanations. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 551–561. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308386

- Turok, I. (2014). The seventh world urban forum in Medellin: Lessons for city transformation. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 29(6-7), 575–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094214547011

- Van de Ven, A. H., & Poole, M. S. (2005). Alternative approaches for studying organizational change. Organization Studies, 26(9), 1377–1404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605056907

- Wall Street Journal. (2012). City of the year. http://online.wsj.com/ad/cityoftheyear

- Ward, K. (2018). Policy mobilities, politics and place: The making of financial urban futures. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776417731405

- Ward, S. V. (2002). Planning the twentieth century: The advanced capitalist world. Wiley.

- Wood, A. (2015a). The politics of policy circulation: Unpacking the relationship between South African and South American cities in the adoption of Bus Rapid Transit. Antipode, 47(4), 1062–1079. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12135

- Wood, A. (2015b). Multiple temporalities of policy circulation: Gradual, repetitive and delayed processes of BRT adoption in South African cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(3), 568–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12216

- Yigitcanlar, T., Velibeyoglu, K., & Martinez-Fernandez, C. (2008). Rising knowledge cities: The role of urban knowledge precincts. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(5), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270810902902