ABSTRACT

We offer an analysis of embodied utopias, the everyday ways in which children, young people and their families experience urban transformation – urban change which has been imagined, designed and planned to be utopian. Lavasa, a private sector, hill city development in the Indian state of Maharashtra, is one such utopian vision. We use the lenses of citizenship, control, precarity and performance to show how participants embody utopia. In sites of major infrastructural change, development can take years, if not decades. Thus, children are spending their whole childhoods navigating utopian urbanism. We expose a series of intersecting vulnerabilities, impacting on participant mobility, education and livelihood. Despite this, we find a hopeful narrative where participants positioned their bodies as part of urban change. Our focus on embodied utopia complicates understandings of neoliberal utopian urbanism.

First we used candle only … ma’am, before there is so dark, and now … we can see everything. (CH14, Male, 13)

All of the young people and families in this paper are positioned in some way, physically, socially, culturally, and emotionally at the margins of utopian urbanism – their lives are at once marginal, but their bodies are also implicated and entwined with Lavasa as a place and a utopian dream. Given this, we use the opening quote as a starting point for unpacking embodied utopias; by this, we mean the diverse ways in which our participants encountered urban transformation – through their bodies and affective experiences. The metaphor of coming out of the darkness into the light is representative of young people’s experiences of living in the shadows of urban change. For many of our young participants and their families, being intrinsically connected to this land of utopian urbanism, whether it be via schooling, work, play or the proximity of their home, gave participants a window to a brighter, lighter future. This is, however, only an entry point; the contribution of this paper is to show the complexities of their experiences of utopian urbanism to highlight the ambivalence of their lived experience of urban transformation. Young people and their families are entangled in a material, social, political, emotional web – at once marginal, yet central to the infrastructures, provisions, dreams and imaginations of the future city. This research draws on data from 40 families which were involved in multiple research activities over 11 months of fieldwork in 2015. In this paper, we do not tell the stories of specific family units but draw on the perspectives of both young people and others in their family to show how marginal bodies were subsumed in the urban utopia.

We frame Lavasa as a land of utopian urbanism because, at the time of fieldwork, it was – it was a new build city development, which had been imagined, designed and planned to be smart, futuristic and technology-driven. It was an example of Indian private sector involvement in urban transformation, a drive toward safer, cleaner, more intelligent living (Townsend, Citation2013; Caprotti, Citation2014; Datta, Citation2015) – a utopian urbanism to counter the myriad of challenges that faced existing Indian cities. While “utopia” was not used in the everyday articulations of city building, expressions of it emerged in our ethnographic encounters with our participants. The utopian vision was one of future possibilities, control, perfection, hope and order (see also Kraftl, Citation2011; Friedmann, Citation2000). Despite this, there is a wide literature critiquing utopia, see, for example, Geddes (Citation1949) on Eu-topia and Ou-topia; Srinivas (Citation2015) on change from within; and Pinder (Citation2014) on progressive utopianism. In 2002, Pinder argued that “the sense of hope embedded in such utopian projects has now passed” (Citation2002, p. 233). He argued that “this kind of urbanism has been denounced as inherently oppressive” (Citation2002, p. 233) and quotes Harvey who said “no one believes any more that we can build a city on a hill, that gleaming edifice that has fascinated every Utopian thinking since Plato and St Augustine. Utopian visions have too often turned sour for that sort of thinking to go far” (Harvey, Citation1993, p. 18). However, in the context of our research, Lavasa, a new hill city, was very much planned and promoted as a “gleaming edifice” – “a liveable city of the future where residents can live, work, learn and play in harmony with nature” (Lavasa, Citation2013). In the context of Auroville (see Auroville, Citation2022 for more details of this utopian experiment), Namakkal (Citation2021) argues that the learnings from Auroville as a utopian place show that “utopia is hard to enact at home, on known land … ideally, constructing a utopian society requires a stretch of vacant land, uninhabited by people” (p. 92). Ourcase study, Lavasa, in contrast, was built on forested land inhabited by generations, so we show how diverse participants and bodies were folded into the utopian dream.

We use the notion of embodied utopias to enable a fuller unpacking of how city building projects are experienced – to shed light on “everyday utopias” (Cooper, Citation2014) and the “unintended consequences” (Kitsch, Citation2000) of life on the margin of urban development. Our analysis focuses on those who are repeatedly excluded from utopian visions of the city (Brosius, Citation2014) both in terms of visual representations and the physical materialities of city building. It is through the voices and experiences of our participants who live on the margins of Lavasa as a place – physically and socially, that we can show how their bodies and values became consumed in the vision, imagination, infrastructures, and politics of place. Before we do this it is important to recognize that unpacking the embodied dimension of urban utopia in the context of a predominantly Hindu new city development, cannot be disentangled from the question of caste and how caste-based relations shape the socio-material life and the aspirations of children and their families in Lavasa. There is not space to go into the socio-historical underpinnings of the Indian caste system here; however, it is important to recognie that it is “one of the most complex contemporary systems of graded hierarchies between labour and labourers” (Kapoor, Citation2021, p. 165). Caste is complex and it demands deep knowledge of the localized intricacies of social, political and ritual hierarchies – as outsiders, these are difficult to access. From the outset, as European, White female researchers, working with local field assistants who themselves were positioned within caste power relations, we were acutely aware that our access and insights to the caste implications were limited. Our experiences of caste were very much mediated and “translated” for us by our informants, which of course was based on their own positionality and the relationship they had with particular social groups. As such, we did not set out to investigate the underlying caste structures in this place but were aware of the entanglement of caste with embodied experiences of utopia.

We have two key contributions. First, in doing research with those who are routinely moved-on from the land, both physically and rhetorically (Datta, Citation2015; Brosius, Citation2014) – we can contribute to the impact of utopian urbanism on diverse bodies. It has been recognized elsewhere that urban transformation is an “affective event” (Butcher & Dickens, Citation2016); thus it is important to offer an insight into the realities of life at the margin, through the lens of embodied utopia – showing, on the one hand, the splintering inequalities they face, and on the other, the diverse ways in which their bodies are folded in to utopian urbanism. Second, Markus (Citation2002, p. 17) reminds us that “built forms and human bodies are both implicated … [it is] impossible to think about designed or built utopias without thinking about bodies in space” – considering this, we build on a theorization of embodied utopia – to show how bodies at the margins are entangled in the thorny process of building urban futures. Our analytical focus on citizenship, control, precarity and performance coheres with and pushes further our underlying argument about embodied utopia. It is through these lenses and attention to the material realities, embodied performances and affective experiences of our participants that we can get closer to understanding the complexities of urban utopianism.

Indian urban utopias

To frame the paper and to understand the choice of Lavasa as a case study – a new city in the making, it is useful to be reminded of the wider context of Indian urban utopian experimentation. In 2010, the McKinsey Global Institute suggested that, in order for India to progress socially, economically and politically, a planned portfolio of cities was needed to sustain growth (McKinsey Global Institute, Citation2010). The report paved the way for the conception of the 100 Smart Cities agenda – with the aim of developing cities equipped with “core infrastructure,” that was “clean” and “inclusive” to “drive economic growth” (Ministry of Urban Development, Citation2015). The Indian Government hoped that this major program of urban renewal and utopian vision would put India on the map to “act like a light house to other aspiring cities … [to be] replicated both within and outside the Smart City” (Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Citation2018). This agenda was characterized by an emphasis on planning urban perfection (Datta, Citation2015); a utopian ideal that sought to counter the chaotic urbanism that characterizes Indian cities, placing urbanity at the center of the national utopia and relocating the rural in the discourse of Indian tradition (Kuldova & Varghese, Citation2017). Over the last 10 years, urban initiatives have proliferated, including – (i) the development of Dholera, the “entrepreneurial city” (Datta, Citation2015); (ii) the Gujarat International Finance Tech-City (GIFT, Citation2020); (iii) the planning of Andhra Pradesh’s new capital city, Amaravati (Upadhya, Citation2017), (iv) the Government of India’s Smart City agenda (see below) and (v) gated communities, part of neoliberal utopia, coined as “luxotopia” (Kuldova, Citation2017). It is important to situate these urban utopias in the context of the current Hindu nationalist state making project, rooted in the Hindutva ideology, advocated by the Narendra Modi’s Government (Chatterji et al., Citation2019). These “world class” urbanism projects (appropriated from the McKinsey rhetoric) are mobilized to create new formations of citizenship, privilege and right of access based on ethno-religious identity and socio-economic status privileging urban middle-class and business elites. Nowhere this is more evident as in the (contentious) processes of heritagization and urban renewal of (Hindu) religious sites underway in key symbolic cities - such as the Kashi Vishvanath Corridor being implemented in the pilgrimage city of Varanasi (Lazzaretti, Citation2021).

Of course, India is not new to utopian visions of the city, as was the case of Chandigarh, Independent India’s claim to create a different urban landscape, or with Delhi’s post-liberalisation Masterplan that “attempted to re-order it within a framework of ‘world class’, ‘modern’ urban living” (Butcher, Citation2018, p. 729). The Smart City agenda is the most recent expression of newness, characterized by harnessing the imagined potential of technology. The momentum behind the scheme is well underway; civic bodies, the private sector (Moser, Citation2015), international consulting agencies, NGOs and the academic community are all involved in shaping, delivering and critiquing this latest utopian articulation. Not only is the private sector a key player in Narendra Modi’s Smart City initiative (The Economic Times, Citation2016), but smaller scale, none-the-less significant, private-sector-led developers are promising “greener,” “safer,” “cleaner” and “smarter” living (Caprotti, Citation2014). A key feature is an emphasis on using information communication technologies to produce efficient, intelligent, “smart” cities (often using city sensors, tracking tools and real-time monitoring) (Townsend, Citation2013; Datta, Citation2019). In the context of Dholera, Datta argues that this is a “socio-technical manifestation of an urban utopia” (Citation2015, p. 4) where multinational technology companies are playing a part in developing city-wide systems to track bodies and materials.

New developments are planned to be physically and experientially different. At the time of research, advertisements for a “better life” littered India’s highways, billboards and hoardings, “paint[ing] a utopian vision of safety and peaceful seclusion” (Brosius, Citation2014, p. 94). Given this, the conceptualization, planning and lived experiences of such spaces are under increased academic scrutiny (Brosius, Citation2014; Caprotti, Citation2014; Datta, Citation2015; Christensen et al., Citation2017; Hadfield-Hill & Zara, Citation2020, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Alongside the opportunities which exist for urban creativity, commentators (across disciplines) highlight the associated challenges and uncertainties. It is important to note that many of these schemes have an ingrained “rhetoric of urgency” (Datta, Citation2015, p. 5) often critiqued as a tool for social control (Caprotti, Citation2014; Datta, Citation2015). Indeed, the ideology of the Smart City has been used as a way to legitimise the neoliberal urban project (Jazeel, Citation2015), which raises significant concerns for who and what is absent. Datta (Citation2015) asks who is missing and removed from such “world-class” urbanism. She asserts that “Dholera reflects a new global trend in the large-scale expulsion of those that cannot fit” (Citation2015, p. 5). It is imperative that we question who new “utopian” urban spaces are for, recognizing the potential these projects have on exacerbating existing inequalities – excluding, dispossessing and marginalizing the most vulnerable.

The smart, utopian urban agenda is not unique to India, indeed similar visions have emerged across Africa (see for example Gastrow, Citation2017 on Cement Citizens in Angola; and Di Nunzio, Citation2019 on hustlers in Addis Ababa) and Asia. In much of this utopian planning there is an emphasis on completely new cities which are couched in the language of new futures, “futureproofing, fast-forwarding, leapfrogging and jumpstarting” (Datta, Citation2019, p. 397). Utopian urbanism in India is characterized by a rhetoric of fastness and newness. Existing research on what life is like in these new spaces focuses on the technological aspects of smartness (Datta, Citation2019); the aesthetics and belonging in luxurious utopia (Kuldova, Citation2017); and dispossession of those at the margins (Goldman, Citation2011; Kuldova & Varghese, Citation2017; Kuldova, Citation2017; Datta, Citation2015; Srivastava, Citation2014). For Kuldova (Citation2017, p. 39), luxotopia is characterized by enclosed spaces and an emphasis on security and protection as well as an “aesthetics of belonging.” Rightly, there has been focus on those excluded. Goldman (Citation2011) for example, using the case of Bangalore, has shown how rural communities have been “thrown into the center of world-city making” (p. 556), and their experiences characterized by dispossession. This erasure at the margins is what Srivastava (Citation2015) refers to as “residual residents” – those that are left over or left out of the utopian vision for city life. In this paper, we expose a series of more detailed, embodied accounts of life at the margins. We have argued elsewhere that researchers should be “open to multiple, shifting, embodied, intersecting experiences of marginality … moments which may be fleeting, temporary or deeply engrained … experiences which shape people’s past, present and future” (Hadfield-Hill, Citation2019, p. 172).

Lavasa – a utopian dream?

This is an opportune moment to provide a little more context for our case study site, Lavasa – a new planned hill city in the densely forested Sahyadri mountain range. At the time of our fieldwork, this place, for many of our participants was still a utopian dream, while cracks were emerging and the messiness of urban transformation unfolding (as we will come on to) – people were dreaming big and were willing Lavasa as a place, a concept, a city to work. In the quote below, one of our participants, a parent, describes this willingness to succeed, given the relationship between land, people, organization and place:

Today the city has become a golden city, we gave you our lands, we cooperated when and wherever you asked us to … we wanted the project, we got facilities … all because of Lavasa … Lavasa was our land … today you need us and we need you. (PA48, Male, 53)

This city in the making (for a planned population of 300,000 residents) offered an alternative urban experience, a different way of life, an urban space set within a green, clean, “beautiful” landscape. Key planned features included: (i) five self-sustaining towns; (ii) diverse accommodation types including studio apartments, villas, affordable starter … and workforce housing; (iii) an integrated development [for] people to “live, learn, work and play in complete harmony with nature”; (iv) a dedicated city management services team; and (v) award-winning urban design “developed on the principles of New Urbanism” (Lavasa, Citation2014b).

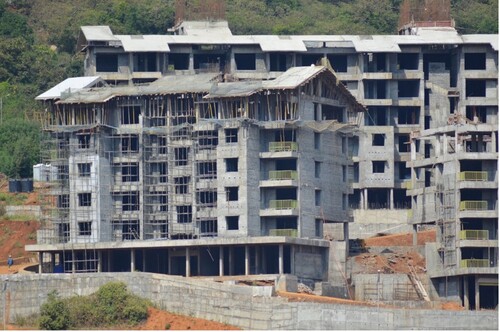

In 2015, the infrastructure and services (including schools, shops, a university, a range of dwelling types, offices, roads and hotels) of Dasve, the first town, was near completion. The other towns remained as plans, with some periodic construction. It is commonplace for such utopian landscapes to imitate urban aesthetics from other countries and contexts, a “cutting and pasting” (Roy and Ong, Citation2011) of architectural styles. In Lavasa, this is no more so evident than with the Promenade, a space designed to mimic the Italian harbor side fishing village, Portofino. The colors, the architecture and street names (i.e. Portofino Street) exude a place “out-of-place” – a little Italy, in India; as critiqued by Brosius (Citation2014, p. xxi) these types of urban form “risk[s] lack and loss of traditions, dilution and inauthenticity of place and spatial practices.” Indeed, we will come on to show that these everyday infrastructures “enforce regimes of control and create geographies of abjection and segregation” (Di Nunzio, Citation2018, p. 1). While we touch on the aesthetic dimensions of place in this paper, particularly in relation to our analytical lenses of control and performance, there is not space to more fully explore the social aesthetics (MacDougall, Citation1999) of utopian urbanism. of incomplete buildings and of a Gaothan show how Lavasa as a place was far from the images which circulate in promotional material (as visualized in ) – showing the tension between utopian imagination and the concrete, material reality. These are the “unintended consequences” (Kitsch, Citation2000, p. 5) of utopian urbanism. During the research, the Indian real estate sector was in crisis, this left the Corporation, the city development, and its people in precarity. At this time the tourism industry was keeping the “dream of Lavasa” alive, with hundreds, if not thousands of visitors making the pilgrimage to the hills in search of monsoon weathers and to experience the “new urban.” The majority of people living and working in Lavasa were employed in tourism, education, construction and servicing.

Figure 3. Photograph of brightly colored buildings which are often used in promotional and sales material, Source: photograph by author.

Since its conception, the Lavasa project has faced critique, with controversies surrounding the environmental clearances (Kahn, Citation2011; Datta, Citation2012) and certification (Buckingham & Jepson, Citation2014) to land acquisition and the focus on the Indian upper-middle class as the target consumer (Datta, Citation2012) – even today, at the time of writing, there are ongoing media reports referring to the petitions about potential illegalities of land ownership and the involvement of the High Court (Business Standard, Citation2022). Controversies and financial uncertainties have grown over time, causing the development to crumble (Aggarwal, Citation2019). An urban dream turned into a dystopian landscape of decay (indeed in the context of Covid-19, it was proposed that Lavasa should be used as a containment camp for patients, utilizing the hotel rooms and empty buildings – although this was opposed locally, see Press Trust of India, Citation2020 for more details). Lavasa appears now as a piecemeal of unfinished infrastructures, far from the bustling city that was imagined and planned. Our participants will be left struggling with the dispossessions, resource and service dependency and environmental vulnerabilities brought in by the promise of a brighter urban future, which failed them. However, it is the making of urban utopia at a time of hopeful participation in, as well as structural marginalization from the city-to-be, that is the focus of our analysis. Earlier we quoted Harvey (Citation1993, p. 18), who said that “no one believes any more that we can build that city on a hill.” However, as we have shown, Lavasa as a utopian hill city was visualized, planned, part-built and lived in, a new city in the making. It is in this context that we are interested in children and their families embodied experiences.

To further set the context for the people, place and marginalization which are central to this paper, it is important to explain how Lavasa “counted” its citizens. Those participants who had a claim to the land were counted not as residents or citizens but as a marginal population who instead were “looked after” by the Community Development Department (CDD). It was via Lavasa’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) program that these families were given a place in the utopian city rather than as fully participating citizens. They were the “population” – those who are governed, as opposed to the “citizens” – rights-bearing subjects who should govern themselves (Chatterjee, Citation2004). However, it is also important to note that these people were also governed by the Gram Panchayat (village council).

During our time in Lavasa, we spent time with the CDD team, it was their responsibility to look after those whose families had historically lived on the land (18 villages). They attended to housing, service supply (i.e. electricity and water), schooling and employment needs. Essentially the team were to keep positive relations between the Villagers and Lavasa as a corporation. In all of our interactions, they appeared to have a sympathetic relationship with the rural communities and were genuine in their work. From the outset, Lavasa were keen not to ask the local villages to resettle outside of the project area (although they were asked to leave their homes and parcels of land), as explained by a representative of the CDD:

Lavasa … never asked [the] community to leave [their] place … they said whoever wants, they can have their own properties here, their lands and they can be with the project but Lavasa will take care of them. (CDD representative)

While we focus on individual bodies, lives and experiences incorporating the story of Lavasa as utopia, through this lens we can also see the macro-story of India as (Hindu nationalist) utopia unfolding. The research took place during the nascent Modi's government, at a time of thriving economy and social aspirations boosted by a decade of steady GDP growth, linked primarily to cities, and massive expansion of information and communications technology (Malik, Citation2015). The country’s urban development has since been the primary ground of the ruling ethno-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party to action a progressive Hinduisation of India. With its predominantly Hindu demographics, Lavasa was not a site of religious tension; for example, the Parsi participants we talked with – a significant regional Zoroastrian minority group – did not express particular concerns in terms of communalism. However, Hindu tradition and folklore were apparent – from the corporation supporting village temple construction, to the city management organizing public worship ceremonies during major Hindu religious events, such as Ganesh Chaturthi. Although the emphasis in Lavasa was laid more on the eco-smartness discourse, the rhetoric and practices of local Hindu heritage were subsumed and embedded in urban future-making – here as elsewhere in Modi’s New India.

Despite the disclaimer that we offered at the outset about caste relations in Lavasa, we noticed that our informants (those who facilitated the research) tended to simplify caste group dynamics using a lexicon that we assume here as a way to reflect their own framing of social relations. So, for example, “villagers”; “sahibsFootnote1”; “Lavasa people”; “labourers”; “katkariFootnote2”; “scheduled tribe”; “forest people” were common terms used to identify groups of people characterized by particular social and caste differences. Young people in the lower caste spectrum often referred to second-home owners and investors in Lavasa as “sahibs”, or “rich people”; for urban middle-class higher education students, tourists and the Lavasa management, caste-based agrarian families were simply “the villagers,” while for rural inhabitants, “Lavasa people” identified as a privileged group in control of local resources and access to jobs. The words “dalit” or “untouchable” were rarely used to identify specific individuals or groups of people, but caste division was apparent, particularly in the material conditions and the discourses surrounding the Katkari community – the “scheduled tribe,” the “forest people” – and the migrant laborers.

Embodied utopias

It is through the lens of embodied utopias that we unpack young people and their families’ experiences of neoliberal city building; in doing this we open up possibilities for theorizing affectual encounters with people and place in the context of utopia. Building on Bingaman et al. (Citation2002) who uses “embodied utopias” to get closer to the “transformative aspects of utopianism … the bodies, indeed the inhabitants and users” (p. 11) – we use it to understand the felt and lived experiences of a city in the making to unpack the multiple ways in which bodies are folded into hopes, dreams and city infrastructures. However, we are aware of the contradiction/challenge of researching utopia whereby visions and articulations are abstract and bodily experiences are fluid and interchangeable (Bingaman et al., Citation2002). We also highlight the failures of utopia – in other words the “unintended consequences” (Kitsch, Citation2000, p. 5) of utopic visions which have in the process of realization been quashed. Similar to Butcher and Dickens (Citation2016, p. 804), we are interested in “urban affective geographies”, where a focus on affect, people, place and infrastructures in the context of urban change gives insight into “new classed and intercultural interactions that generate discomfort and subsequent exclusion” ( p. 805). Our participants' bodies were at once hopeful, yet entangled in marginalization showing the complexities of embodied utopias.

We are informed by post-structural and feminist utopian theory, which encourages us to uncover the “going-on of (utopian) existence” (Kraftl, Citation2006, p. 36) and the hopeful (Webb, Citation2008) narratives of utopia, entwined with dreams (Kraftl, Citation2011). If we take hope to be socially constructed and mediated between bodies, infrastructures and visions for place we need to recognize that “different individuals … at different historical junctures, embedded in different social relations, enjoying different opportunities and facing different constraints, will experience hope in different ways” (Webb, Citation2008, p. 198). Given this, we are interested in the multiplicity of everyday hopeful utopias, where they emerge and how they are experienced and negotiated in the ongoingness of life. Hopeful utopia is undoubtedly emotional, and more-than-representational (Anderson, Citation2006; Kraftl, Citation2006) and this lens enables us to look at the emotions, sensitivities and affectual relationships that people have with material infrastructures of shifting urban environments. We are sensitive to what Amin (Citation2014, p. 139) describes as Lively Infrastructure – where “the circulation of sights, smells, sounds and signs, or the assemblage of buildings, technologies, objects and goods, are seen to shape social behavior as well as affective and ethical dispositions.”

Pinder (Citation2014) advocates for progressive utopia, arguing that everyday utopianism “emphasises the potentialities on the present situation rather than projecting them into another time or space” (p. 239). Considering this, we are interested in the here and the now of the embodied utopia – how our participants experienced the lived realities of a utopian city-building project. We are also aware of the contradiction in terms of embodied utopias in that “the body signif[ies] unpredictability, concreteness and change, and utopias [are] characterised by predictability, abstraction and permanence” (Bingaman et al., Citation2002, p. 2). For this reason, we have four entry points to unpack embodied utopias: citizenship, control, precarity and performance, each of these are on the borderline between unpredictability and abstraction. Let us explain. First citizenship, indeed smart citizenship, in various guises is a strong narrative of the utopian city-building project (Cardullo & Kitchen, Citation2019), however, citizenship on the ground is felt and experienced very differently. Second, the utopian city has control and order at its center – controlling populations of human and non-humans alike; the affective embodied experiences of control are explored in our analysis. Third, precarity – the building of the utopian vision is precarious, it relies on power, people and politics and as a result, precarity is an everyday, embodied, felt experience. Lastly, performance – the utopian city-building project is a performance of aesthetics as well as the building of a stage for diverse bodies to conform to certain expectations. Using these lenses, we pay closer attention to embodied utopia; the unintended consequences, the affectual, material experiences, the ways in which our participants were at once marginalized by the utopian project but also positioned themselves within it.

Researching embodied utopia

Our data collection methods enabled a unique insight into the embodied experiences of utopia. For context, the data emerged from an ESRC-funded project “New Urbanisms in India,” a qualitative study, designed to understand the everyday experiences, expectations and lived realities of living in Lavasa, a new urban development. Data collection was grounded in ethnography; as researchers, we lived in Lavasa, the case study site for most of 2015 (11 months). This approach enabled us to more fully understand the lived experiences of diverse groups (including consumer-citizens buying flats, construction workers, those who had a claim to the land and its past, migrant workers, students studying in Higher Education institutions, hotel and service workers and tourists). We worked with 350 participants, which included 40 participating families. We used a range of qualitative methodologies to gather data on everyday life, including one-to-one interviews with young people and their parents, some of which were conducted as guided walks and Google guided walks (160 interviews), drawing methods with younger participants (78 children’s drawings), community-based workshops (130 participants) and the use of a mobile app “Map my Community” (47 participants) to map mobilities and everyday interactions with community infrastructure. The research was approved by our University ethics committee and guided by ESRC ethical principles of doing qualitative research. While Lavasa as a city building project is named, none of the participants are identified by name or are distinguishable by association. For an overview of the project, see Hadfield-Hill and Zara (Citation2017, Citation2018) and our writing on inequalities and the monsoon (Hadfield-Hill & Zara, Citation2019b); urban multi-species encounters (Citation2019a); and children as geological agents (Hadfield-Hill & Zara, Citation2020).

The data analysis for this paper focuses on one group of participants, those children, young people and their families who had a prior relationship to the land – those who experienced relocation and witnessed the building of a new city (this included 44 participants who had (i) lived in Lavasa continuously since birth [35]; (ii) those who had connections to the land but who spent time elsewhere for work or other family commitments [6]; and (iii) those who were not born in Lavasa but lived on the land since they were young [3]). Our participants were exposed to an infiltration of people, values, concrete, architects, ideas, dreams and more. In the analysis, we draw on our interview and guided walk data, it is through these methods that we are able to write about embodied utopias. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, schools and on the move – we sat and moved with our participants as they told us about their relationship with the land and the changes unfolding around them. During the monsoon season, our guided walks were adapted to Google guided walks, an interview-based around the interactive Google Earth image mapping the opportunities and challenges they were experiencing. These methods, combined with our ethnographic approach enabled us to experience utopian urbanism first-hand – the dreaming and the hoping – but also the precariousness of city building where dreams erode, streets become littered, and the orderly and sanitized becomes unruly. In 2015, the promise and everyday articulation of utopia were very much alive – a dream in the making. It is with this in mind that we share our analysis of embodied utopia.

Unpacking embodied utopia

Citizenship, control, precarity and performance were key tactics and processes through which neoliberal urbanism was enacted in Lavasa. Crucially to the theorizing of embodied utopia, these processes revolve around materiality and the body to put the utopian urban ideology to work. Using these four entry points, we show how urban utopianism is projected onto bodies and forms, how it is felt, made fleshy and performed. In doing this, we expose the bodily and material workings of neoliberal urban utopia – the “social aesthetics” (MacDougall, Citation1999) of this new urban development, that is, the complexity of socio-material and sensory elements producing this new urban experience. It is through embodied, material and affective relations, we argue, that the “ideal(ised)” Lavasa becomes (precariously) alive for those at the margins of the urban dream. We find that our participants embraced, incorporated, questioned, were left out from and hoped for this utopian vision. In fact, it is their precarious and ambivalent positioning as both “in” (through hope, disciplining and alignment) and “out” (through precarity and exclusionary practices) of the urban utopia that we argue is a key finding. We develop a narrative around the entangled, material, hopeful and precarious relationships which dis/connect marginalized social groups in spaces of urban transformation.

Citizenship

In the context of smart city development, citizenship has become a point of investigation – Cardullo and Kitchen (Citation2019, p. 814) for example, argue that “citizens occupy a largely passive role, with companies and city administrators performing forms of civic paternalism (deciding what’s best for citizens) and stewardship (delivering on behalf of citizens).” Indeed, Datta (Citation2018, p. 408) argues that the “smart citizen … reinforces historical and contemporary paradoxes of identity and belonging.” Other research speaks of “propertied citizenship” (Hammar, Citation2017; Roy, Citation2003); and “cement citizens” (Gastrow, Citation2017) in unpacking the relationship between land, housing ownership, bodies and citizenship. Our research shows how citizenship is used as a device to include/exclude bodies that count/do not count as “proper” urban citizens – ultimately based on market-driven criteria and performed as part of a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) agenda. We show what this feels like for our participants – what it feels like to be, or rather not to be counted as a citizen. To understand this, it is necessary to give some context to how Lavasa articulated citizenship. In the day-to-day management, they routinely used the language of resident and citizen – but what did this mean? While we were in the field we became interested in the ways in which different bodies were counted in city life, finding that the expression of resident and citizen had a profound, embodied impact on how our participants experienced life.

Lavasa management was keen to direct us toward their Community Development Department (CDD) to showcase the work they were doing with the “Villagers.” This was the start of our unpacking of the structural relationship between people, place and land. In the excerpt below (from official Lavasa documentation) we show how Villagers, their lives and bodies, were categorized as both in place, and out of place. You will see from the extract that Villagers are taken in under the guise of a rehabilitation program, involving them in the development, as a form of labor. Here we can relate to Brown’s (Citation2016, p. 3) argument that “neoliberalism construes subjects as market actors everywhere, but in which roles – Entrepreneur? Investor? Consumer? Worker?” In the context of Lavasa, Villagers were seen as “Workers” – families who had lived on the land for generations were being “upskilled” in neoliberal city-making:

We have implemented various rehabilitation programmes for original landowners and villagers to make them part of the development of Lavasa … . training villagers … provide contract jobs … such as tree plantation, contour trenching, bush cutting, seed collection, mass plantations, fencing … . (Lavasa, Citation2014, p. 213)

It is going to be a big city … at that time we won’t be counted in that at all … at that time, only your customer’s name, of the owners of these bungalows, they will be mentioned there. (PA48, Male, 53)

this mango tree is for her record … whenever my father felt like meeting my grandmother, his mother, he hugs that tree. (CH06, Female, 11)

Of course, there were participants who spoke about the benefits of living in these new concrete homes – acknowledging some of the materialities of connection, i.e. water, electricity and road. However, it was the moments of disruption which exacerbated marginality. During the fieldwork, we lived through an unsettled period where Lavasa teetered on the edge of bankruptcy – this had an immediate impact on those living on the margins – with school buses cancelled, water tankers delayed and connections severed. This relates to Larkin’s (Citation2013, p. 335) analysis of Lea and Pholeros' (Citation2010) “when is a pipe not a pipe” – arguing that such houses “generate an aesthetic order” (p. 191), “[where] pipes … may not be attached to an affluent disposal system, but … attached to techniques of regulation, audit and administration” (Larkin, Citation2013, p. 335) – to this we would add, in times of crisis, connections can easily be severed. This was the case for the young participant quoted above (CH06); for her, with the new development came access to Lavasa’s brand new English medium primary school, to which she travelled daily on a one-hour bus journey. The bus, also provided by Lavasa, was repeatedly interrupted during the financial turmoil, impacting on her regular access to education. Another example of the promising utopia turning into vulnerability. Citizenship for these participants was something that was way out of reach, they could not walk into the CCC and access the services on offer - they were not the “citizen” that was counted and marked on the board. Their citizenship was negotiated through a CSR program, one that saw Villagers as “others” and as empty vessels devoid of emotion, attachment to place, and deficit of skills and knowledge – a body to be trained, to be monitored, to be controlled, to be moved from one place to another.

Control

We now move on to show how participants’ bodies were controlled. As per the development guidance, Lavasa had two core methods (framed as safety and security), one via the State police force, provided by the local government and second a network of Lavasa-trained and managed security guards (Lavasa, Citation2014) who governed and controlled the populace, including citizens, residents, tourists and others. At the time of fieldwork, there was a significant security presence, particularly on the Promenade, where guards were strategically positioned; they watched and waited for rules to be broken. A high-pitched blow of a whistle signaled that a body was out of place, perhaps veering too close to the water’s edge or signaling that a fruit seller had paused to sit down. Our participants felt that their bodies were controlled, moved on and out of place. In the quote below a parent speaks of not being able to sit and sell fruits on the Promenade (a trade that supports her family). She lived in a modest house, in a rural village 15 km from the core town of Dasve, which she had no other means to reach other than by walking or relying on occasional rides from passing vehicles. She was fully aware of her vulnerable body being controlled and the implications this had on her and her family:

I thought we belong to this area, we are not even allowed to sit here selling fruits. We can’t sit here, we have to sit at the roadside … and if at all we risk ourselves and argue, then the company people immediately call the security or police. So I feel we will face all the more problems in future … I do agree that we should not roam or loiter … I like cleanliness. (PA51, Female, 26)

Bodies were also controlled at the border of Lavasa, security guards checked passes and quizzed those entering. Kuldova (Citation2017, p. 44) reports that, “only carefully screened low-class bodies can enter the luxury compounds in order to clean, repair or work on the construction.” In the case of Lavasa, there were similar experiences of borders and security within the development. The father of one of our young participants describes how the Town Hall was a guarded space with permissions and passes needed to enter:

they say … Do you have a gate pass to come in? Why are you here? Who has sent you? … Who do you want to visit? Do you have permission? Do you have a pass? (PA48, Male, 53)

Precarity

Everyday experiences were shaped by precarity, both physical and financial. Physically, participants lived with, literally – the bricks, the dust, the construction vehicles and exposed wires. Participants told us that the infrastructural shifts had damaging consequences for their land, buildings, and livestock. Landslides caused roads to be blocked, houses to be damaged and livestock injured. Growing up on a building site is precarious for all sorts of reasons – building a city takes years, decades, childhoods (Kraftl et al., Citation2013). In the case of Lavasa, whole childhoods were spent living with incomplete infrastructures. However, in our analysis of the masterplan, speaking with participants and navigating the site ourselves, it soon became apparent that inequalities had been built into the development from the outset. For example, only certain priority roads were made from concrete (akin to Gastrow’s, Citation2017 – “cement citizens”) connecting the investor-citizen homes with surrounding services.

Our participants were materially disconnected to key services. Here we relate to Markus (Citation2002, p. 337) in their aesthetic analysis of infrastructure, arguing that “the hardness of the road, the intensity of its blackness, its smooth finish … produces sensorial and political experiences.” Indeed, our participants were acutely aware of the different road infrastructures, the hardness of the surfaces, the ease of walking, what was and was not connected. During the monsoon season, those roads which were not concretized were washed away, leaving children and their families disconnected – for weeks, sometimes months. Below, a 13-year-old refers to his house being physically severed; life for his family was difficult – in the quote, he asks for cement roads. He lived in the rural fringe of Lavasa, a household of nine in a one-room building, no formal sanitation and ground water as the main drinking source. He walked daily through the forest to the bus collection point, which took him to Dasve’s English medium school (provided by Lavasa as part of their CSR agenda) – a two-hour-forty-minute journey. In the second quote, a young female participant whose family had lived in this forested region well before the arrival of Lavasa, explains how her mother didn’t let her go anywhere, aside from the government school (an hour walk) – the risk of injury due to the unsettled land was too great:

Put cement on that [the road] … because there is no road or no cars, we walk by leg only. (CH14, Male, 13)

My mother doesn’t allow me to go anywhere now, only to the school because anything can fall on down on us due to rain. (YR69, Female 9)

if they decide to shut down the school then 75% children will have to sit at home, and also they won’t get admitted in a [government] school … this is a 100% loss for the children. (PA50, Male, 37)

Performance

During our everyday encounters, whether walking to the shops, to our interviews or sitting on the Promenade, we were spectators to a performance. The Promenade, next to the lake and lined with shops, seating areas, steps, water features and planting was for many, but mostly the tourists, a stage to perform (selfies, staged family portraits, wedding photography and film scene settings). Visitors used their phones, iPads and high-end digital equipment to record and capture movements, poses and their bodies in the space. The fieldnote excerpt below shows one such account – a group of male friends using their bodies and the architecture to perform and capture:

[they were] staggered up the steps, hands in pockets, sunglasses resting on their heads, looking into the distance. They moved from one position to another - contorting their bodies, leaning, reaching, arching – for that desired image. (Fieldnote, Hadfield-Hill)

… [before] you would see people wearing sari and Panjabi dress; now you see they wear half clothes, you will find them wearing jeans, and pants […] there is a girl who wears half pants [points at a female wearing shorts]. (YR75, Female, 10)

[we are] still getting the alignment of the villagers with the, with the urbanisation or the Lavasa smart city concept, it is progressing.’ (CDD representative)

In sanitation or in hygiene, there is lot of improvement that has happened … earlier there was no concept of having the toilet in house … so they have aligned with the urbanisation. (CDD representative)

many, many improvements have happened in me … my teacher tells me, reading makes a man, teaching makes a man perfect. (CH06, Female, 11)

before I was not knowing anything, now I am knowing everything … children are getting school, they are learning more how to live, how it should be done or not be done. (CH05, Female, 12)

Many people come to the Dam so they talk in English so, uh, we also like to … talk in English with them, because we want to improve … (laughs) … we go there to learn English. (CH28, Male, 15)

Participants marginal, yet implicated in utopia

To this point, we have presented a rather depressing picture of how our participants’ bodies and families were marginalized in the utopian city-building project. Through the lenses of citizenship, control, precarity and performance, we have shown how utopia is embodied by those at the margins, how they are caught up in the designing of exclusionary “aesthetic patterns” (MacDougall, Citation1999, p. 5) and wrapped up in atmospheres of vulnerability. We have shown that those at the margins of urban utopia were surveilled, disciplined and controlled; however, our participants were also implicated in other ways. For example, they aspired and worked hard to fit into the new city; they participated in the disciplining of their bodies (as we showed above) and very much wanted to be the “ambassadors” and future good citizens of Lavasa. Yes, they expressed concern at the erosion of their wider environment, but at the same time, they aspired to become “cement citizens” (Gastrow, Citation2017), sharing the neoliberal vision of “good urbanism.”

Our young participants were very much implicated in the “hopeful” (Anderson, Citation2006) narrative of utopian city making and indeed, utopia is dependent on those at the margins (Kuldova, Citation2017). In essence, places like Lavasa need those at the margins to hope and dream with them because neoliberal development depends on it. From speaking with the CDD, it was clear that Lavasa instilled a sense of hope into our young participants. The corporation relied on them to become positive ambassadors for the utopian vision. It was by providing them with essential work and education that this sense of hope was fostered:

They are the brand ambassador for Lavasa … when they are talking to the outside, they talk about Lavasa because they feel proud to say that “I'm staying in Lavasa” … they have experienced … Lavasa’s lifestyle or urban lifestyle. (CDD representative).

They're playing a very important role in making the Lavasa city … many villagers have taken the work contracts … so they're doing the work for Lavasa. (CDD representative)

We take part in building th[ese] buildings, give more ideas how to make the city more attractive. (CH11, Female, 11)

It shouldn’t be this muddy … put cement on it … where there’s mud, it should be removed … they should pour cement on it. (YR74, Male, 10)

Conclusion

We began with a quote from one of our young participants. His family had lived on the land for generations and with the building of Lavasa he described coming out of the darkness into the light – we used this as a metaphor to set the context. With the new city infrastructures, our participants literally had access to light (via electricity) and there was an overarching narrative of hopefulness, of light, of newness.

Our focus on embodied utopia is important because it gets closer to understanding the everyday realities of children, young people and their families who are on the edge of utopia. Bingaman et al. (Citation2002, p. 11) remind us that “one of the flaws in utopias both past and present has been their neglect to consider not just places / spaces but also the bodies, indeed the inhabitants and users, that constitute these spaces … the social and corporeal practice.” Indeed, Grosz (Citation2002) also asks, “how do bodies fit into the utopic? In what sense can the utopic be understood as embodied?” and goes on to acknowledge that “every conception of the utopic, from Plato, through Moore, to present-day utopians, conceptualizes the ideal commonwealth in terms of the management, regulation, care and ordering of bodies” (Citation2002, p. 272). Our participants’ experiences of this utopian city making project were very much embodied, they were real, they were felt. To unpack their experiences, we used four entry points; citizenship, control, precarity and performance. In doing this, we found that our participants were caught in a utopian web of boundless progression – positioned in a sort of evolutionary trajectory from Indigenous, traditional, nature-bound living, to becoming modern, urban subjects. Our analysis showed that their bodies were implicated in the dream of progression and the utopian project was dependent on those at the margins hoping for a better future. Participants’ experiences were shaped by who was “counted” as a citizen of the utopian city. Despite living, working, learning and playing on the land, their bodies were not officially counted as citizens. Their resident status was embodied and emotive. Their experiences were further compounded by atmospheres of difference; not “fitting in” with the utopian vision. Thus, we found citizenship to be constructed upon material (i.e. “property”; gaothans; urban infrastructures vs. rural “backward” precarity), performative (i.e. “aligning with” the urban ethos) and affective (i.e. feeling in/out of place, belonging/not belonging in the new city) markers and devices. These embodied experiences are akin to the “tragedies and ironies” (Chakrabarty, Citation2000, p. 43), which Datta (Citation2015) asks us to unpack in the delivering of the Smart City agenda. Indeed, these atmospheres of vulnerability were compounded by a series of “unintended consequences” (Kitsch, Citation2000), moments and events in the building of utopia, which had significant everyday implications for participants’ mobilities, education, livelihood and indeed, life itself.

Despite these findings, we found that our participants were very much implicated in the hopeful narrative of utopia. They spoke of the key role that they played in building the vision, from constructing the roads and houses, to laying the pipelines. They keenly expressed that their bodies were part of utopia, part of building the dream and vividly narrated their ideas of what they want their city to look like. Their hopeful expressions (Webb, Citation2008) were entwined with neoliberal, capitalist utopia; they embraced utopian urbanism, positioning their bodies as part of it. They used this as a mechanism to counter their “anxieties about being left behind, or left out” (Brosius, Citation2014, p. 4). These hopeful expressions of the utopian city were part of a narrative of going-on, searching for “moments that somehow evoke, represent or engender something that feels like ‘the good life’” (Kraftl, Citation2010,p. 330).

At the time of our fieldwork, cracks were beginning to emerge. While we have touched on how precarity impacted the lives of our participants, this is not a paper about the failures of urban projects or the failure of Lavasa as a place. Today we read reports about “the invisible victims of an unfinished city” (Aggarwal, Citation2019); the potential liquidation of Lavasa Corporation (Business Standard, Citation2020); and hopes for “reviving the project” (The Times of India, Citation2021); indeed it is necessary to revisit to understand what life is like in a place that many are now referring to as dystopic – the end of the utopian dream. For the purpose of this paper, however, at the time of our data collection, children and their families were very much implicated. Urban utopia was materialized through socio-material-corporeal-affectual everyday experiences, performances and hopeful dispositions. We don’t foreground the “mere bodies” of our participants, rather, we show how they were deeply involved in the formation of new urban subjectivities implicated in the Lavasa project - physically and emotionally entwined with the utopian narrative. In doing this, we uncovered a series of vulnerabilities which percolated through the city building project, these were profoundly felt, yet, entangled with a strongly articulated sense of hopefulness, further adding complexity to our understanding of embodied utopia.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Economic and Social Research Council for funding this research. Thanks also to all the reviewers who contributed their own thoughts and perspectives on this piece. Most of all, we are very grateful to the children, young people and their families who so willingly shared their everyday experiences of urban change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Colonial term indicating a man in a position of authority.

2 Indian scheduled tribe from Maharashtra. The Katkari communities are associated to notions of untouchability and exclusionary practices.

References

- Aggarwal, M. (2019). The invisible victims of an unfinished city. Retrieved July 22, 2021, from https://india.mongabay.com/2019/10/the-invisible-victims-of-an-unfinished-city/.

- Ahmed, S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotion. Routledge.

- Amin, A. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7–8), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490

- Anderson, B. (2006). ‘Transcending without transcendence’: Utopianism and an Ethos of Hope. Antipode, 38(4), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00472.x

- Auroville. (2022). Auroville: The city of Dawn. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://auroville.org/.

- Bingaman, A., Sanders, L., & Zorach, R. (2002). Embodied Utopias: Gender, social change and the modern metropolis. Routledge.

- Brosius, C. (2014). India’s middle class: New forms of urban leisure, consumption and prosperity. Routledge.

- Brown, W. (2016). Sacrificial citizenship: Neoliberalism, human capital, and austerity politics. Constellations (Oxford, England), 23(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12166

- Buckingham, K. C., & Jepson, P. (2014). Whose sustainability counts? Reflections on an Indian oasis and the drive for certified bamboo. Asian Geographer, 31(2), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10225706.2014.917687

- Business Standard. (2020). Lavasa hill city hits dirt; lenders may send company to liquidation. Retrieved July 22, 2021 from https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/lavasa-hill-city-hits-dirt-lenders-may-send-company-to-liquidation-120111101748_1.html.

- Business Standard. (2022). Supreme Court issues notice on plea challenging Lavasa land purchase. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/supreme-court-issues-notice-on-plea-challenging-lavasa-land-purchase-122080801609_1.html.

- Butcher, M. (2018). Defying Delhi’s enclosures: Strategies for managing a difficult city. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(5), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1395823

- Butcher, M., & Dickens, L. (2016). Spatial dislocation and affective displacement: Youth perspectives on gentrification in London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(4), 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12432

- Caprotti, F. (2014). Eco-urbanism and the eco-city, or, denying the right to the city? Antipode, 46(5), 1285–1303. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12087

- Cardullo, P., & Kitchen, R. (2019). Smart urbanism and smart citizenship: The neoliberal logic of ‘citizen-focused’ smart cities in Europe. EPC: Politics and Space, 37(5), 813–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X18806508.

- Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe – postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton University Press.

- Chakravarti, U. (2018). Gendering Caste through a feminist lens. Sage.

- Chatterjee, P. (2004). The politics of the governed: Reflections on popular politics in most of the world. Columbia University Press.

- Chatterji, A. P., Hansen, T. B., & Jaffrelot, C. (2019). Majoritarian state: How hindu nationalism Is changing India. Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, P., Hadfield-Hill, S., Horton, J., & Kraftl, P. (2017). Children living in sustainable built environments: New urbanisms, new citizens. Routledge.

- Cooper, D. (2014). Everyday utopias: The conceptual life of promising spaces. Duke University Press.

- Datta, A. (2012). India’s ecocity? Environment, urbanisation, and mobility in the making of Lavasa. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(6), 982–996. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1205j

- Datta, A. (2015). New urban utopias of postcolonial India: ‘Entrepreneurial urbanisation’ in Dholera smart city, Gujarat. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565748

- Datta, A. (2018). The digital turn in postcolonial urbanism: Smart citizenship in the making of India's 100 smart cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(3), 405–419. http://doi.org/10.1111/tran.2018.43.issue-3

- Datta, A. (2019). Postcolonial urban futures: Imagining and governing India’s smart urban age. Society and Space, 37(3), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818800721.

- Di Nunzio, M. (2018). Anthropology of infrastructure, Governing infrastructure interfaces. Retrieved July 6, 2021 from https://lsecities.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Governing-Infrastructure-Interfaces_Anthropology-of-infrastrcuture_MarcoDiNunzio.pdf.

- Di Nunzio, M. (2019). Addis Ababa’s street hustlers helped build the city – now they’re being pushed out. The Conversation. Retrieved July 6, 2021 from https://theconversation.com/addis-ababas-street-hustlers-helped-build-the-city-now-theyre-being-pushed-out-119495.

- Friedmann, J. (2000). The good city: In defence of utopian thinking. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), 460–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00258

- Froerer, P. (2012). Learning, livelihoods, and social mobility: Valuing girls’ education in central India. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 43(4), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1492.2012.01189.x

- Gastrow, C. (2017). Cement citizens: Housing, demolition and political belonging in Luanda, Angola. Citizenship Studies, 21(2), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2017.1279795

- Geddes, P. (1949). Cities in evolution. Williams and Norgate.

- GIFT. (2020). Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT) – A financial and technological gateway of India. Retrieved June 9, 2020. http://www.giftgujarat.in/.

- Goldman, M. (2011). Speculative urbanism and the making of the next world city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(3), 555–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01001.x

- Gopal, M. (2013). Ruptures and reproduction in caste/gender/labour. Economic and Political Weekly, 48(18), 91–97.

- Grosz, E. (2002). The time of architecture in Bingaman. In A. L. Sanders, & R. Zorach (Eds.), Embodied utopias: Gender, social change and the modern metropolis (pp. 265–279). Routledge.

- Guru, G., & Sarukkai, S. (2019). Experience, caste, and the everyday social. Oxford University Press.

- Hadfield-Hill, S. (2019). Margin in Keywords in Radical Geography: Antipode at 50, Chapter 31. https://doi-org.ezproxyd.bham.ac.uk/10.10029781119558071.ch31.

- Hadfield-Hill, S., & Zara, C. (2017). Final report: ‘New urbanisms in India: Urban living, sustainability and everyday life. University of Birmingham.

- Hadfield-Hill, S., & Zara, C. (2018). Being participatory through the use of app-based research tools. In B. Carter, & I. Coyne (Eds.), Being participatory: Researching with children and young people (pp. 147–169). Springer.

- Hadfield-Hill, S., & Zara, C. (2019a). Negotiated, spiritual and destructive multi-species encounters: Childhoods complexifying nature/culture dualisms. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 98, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.036

- Hadfield-Hill, S., & Zara, C. (2019b). Children living through the monsoon: Watery relations and fluid inequalities. Children's Geographies, 17(6), 732–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1648758

- Hadfield-Hill, S., & Zara, C. (2020). Children and young people as geological agents? Time, scale and multispecies vulnerabilities in the new epoch. Discourse, 41(3), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1644821.

- Hammar, A. (2017). Urban displacement and resettlement in Zimbabwe: The paradoxes of propertied citizenship. African Studies Review, 60(3), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2017.123

- Harvey, D. (1993, October 15). Cities of dreams, Guardian, pp. 18–19.

- Idowu, S. O., Vertigans, S., & Burlea, A. S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility in times of crisis. Springer International Publishing.

- Jazeel, T. (2015). Utopian urbanism and representational cityness: On the Dholera before Dholera smart city. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565866

- Kahn, J. (2011). India Invents a City: Lavasa is an orderly, high-tech community with everything. Except people. Retrieved January 11, 2015 from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/07/india-invents-a-city/308549/.

- Kapoor, S. (2021). The violence of odours: Sensory politics of caste in a leather tannery. The Senses and Society, 16(2), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/17458927.2021.1876365

- Kitsch, S. (2000). Higher ground: From utopianism to realism in American feminist thought and theory. University of Chicago Press.

- Kraftl, P. (2006). Spacing out an unsettling utopian ethics. Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal, 1(Spring), 34–55.

- Kraftl, P. (2010). Architectural movements, utopian moments: (In) coherent renderings of the Hundertwasser-Haus, Vienna, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 92(4), 327–345.

- Kraftl, P. (2011). Utopian promise or burdensome responsibility? A critical analysis of the UK government’s building schools for the future policy. Antipode, 44(3), 847–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00921.x

- Kraftl, P., Horton, J., Christensen, P., & Hadfield-Hill, S. (2013). Living on a building site: Young people’s experiences of ‘sustainable communities’ in the UK. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 50, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.08.009

- Kuldova, T. (2017). Guarded luxotopias and expulsions in New Delhi: Aesthetics and ideology of outer and inner spaces of an urban utopia. In T. Kuldova, & M. A. Varghese (Eds.), Urban utopias: Excess and expulsion in neoliberal south Asia (pp. 37–52). Palgrave Macmillian.

- Kuldova, T., & Varghese, A. (2017). Introduction: Urban utopias – excess and expulsion in neoliberal India and Sri Lanka. In T. Kuldova, & M. A. Varghese (Eds.), Urban utopias: Excess and expulsion in neoliberal south Asia (pp. 1–16). Palgrave Macmillian.

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Lavasa. (2013). Lavasa a Smart City. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://india.smartcitiescouncil.com/system/tdf/india/public_resources/Lavasa-A-Smart-City.pdf?file = 1&type = node&id = 2717.

- Lavasa. (2014a). City website. Retrieved July 19, 2015, from www.lavasa.com/high/home.aspx.

- Lavasa. (2014b). Lavasa city guide.

- Lavasa Corporation Limited. (2014). Lavasa Corporation Limited Prospectus. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/attachdocs/1404296879493.pdf.

- Lazzaretti, V. (2021). New monuments for the new India: Heritage-making in a ‘timeless city’. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(11), 1085–1100. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1954055

- Lea, T., & Pholeros, P. (2010). This is not a pipe: The treacheries of indigenous housing. Public Culture, 22(1), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2009-021

- MacDougall, D. (1999). Social aesthetics and the Doon School. Visual Anthropology Review, 15(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1999.15.1.3

- Malik, A. (2015). The India that made Modi’, identity & politics. In F. Godement (Ed.), What does India think? (pp. 34–38). European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/ECFR145_WDIT.pdf.

- Markus, T. A. (2002). Is there a built form for non-patriarchal utopias? In A. Bingaman, L. Sanders, & R. Zorach (Eds.), Embodied utopias: Gender, social change and the modern metropolis (pp. 15–33). Routledge.

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2010). India’s urban awakening: Building inclusive cities, sustaining economic growth. McKinsey & Company.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. (2018). Smart Cities Mission. Retrieved January 21, 2018, from https://smartnet.niua.org/smart-cities-network.

- Ministry of Urban Development. (2015). Smart Cities Mission. Retrieved August 6, 2015, http://smartcities.gov.in/#.

- Moser, S. (2015). New cities: Old wine in new bottles. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565867

- Namakkal, J. (2021). Unslettling Utopia: The making and unmaking of French India. Columbia University Press.

- Pinder, D. (2002). In defence of utopian urbanism: Imagining cities after the ‘end of utopia’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 84(3-4), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2002.00126.x

- Pinder, D. (2014). The breath of the possible: Everyday Utopianism and the street in modernist urbanism. In M. D. Gordin, H. Tilley, & G. Prakash (Eds.), Utopia / dystopia. Princeton University Press.

- Press Trust of India. (2020). Convert properties at Lavasa into Covid-19 facilities: BJP MP from Pune, Retrieved August 10, 2021, from: https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/convert-properties-at-lavasa-into-covid-19-facilities-bjp-mp-from-pune-120073001183_1.html.

- Roy, A. (2003). Paradigms of propertied citizenship: Transnational techniques of analysis. Urban Affairs Review, 38(4), 463–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087402250356

- Roy, A. and Ong. A. (2011). Worlding cities: Asian experiments and art of being global. Blackwell Publishing Limited.

- Srinivas, S. (2015). A place for Utopia: Urban designs from south Asia. University of Washington Press.

- Srivastava, S. (2014). Entangled urbanism. Oxford University Press.

- Srivastava, S. (2015). Entangled urbanism: Slum, gated community, and shopping mall in Delhi and Gurgaon. Oxford University Press.

- Subramanian, A. (2019). The caste of merit: Engineering education in India. Harvard University Press.

- The Economic Times. (2016). Private sector to play pivotal role in smart cities: Report. Retrieved November 24, 2017, from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/infrastructure/private-sector-to-play-pivotal-role-in-smart-cities-report/articleshow/51967685.cms.

- The Times of India. (2021). Senior citizens of Lavasa hill station reach out to CM to revive the project. Retrieved July 22, 2021, from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pune/senior-citizens-of-lavasa-hill-station-reach-out-to-cm-to-revive-the-project/articleshow/82534766.cms.

- Townsend, A. M. (2013). Smart cities: Big data, civic hackers, and the quest for a new Utopia. W N Norton & Company.

- Upadhya, C. (2017). Amaravati and the New Andhra: Reterritorialization of a Region. Journal of South Asian Development, 12(2), 177–202. http://doi.org/10.1177/0973174117712324

- Webb, D. (2008). Exploring the relationship between Hope and Utopia: Towards a conceptual framework. Politics, 28(3), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2008.00329.x