ABSTRACT

This study contributes to the debate on the psychological dimensions of displacement in urban renewal (UR) literature by examining how different modes of UR may disrupt or reconstruct the sense of home for affected residents in urban China. The forms of UR in China have evolved from the intensive pro-growth urban redevelopment that was prevalent in the 1990s and early 2000s to the emerging trend of micro-renewal, which features neighborhood renovation without physical displacement or the remaking of social classes. We distinguish between wholesale redevelopment and micro-renewal, then examine the impacts of these different modes of UR on post-renewal neighborhood attachment (NA). We found that micro-renewal is less likely than redevelopment to disrupt residents’ NA. However, it was the socio-spatial restructuring of their neighborhood, rather than physical relocation, that contributed to the change in residents’ NA. The perceived neighborhood change was also conditional on individuals’ pre-renewal residential satisfaction and post-renewal economic prospects.

Introduction

Urban spaces have become the foreground for capital accumulation (Harvey, Citation2003) through variegated forms of urban renewal (UR), ranging from wholesale redevelopment with extensive demolition and massive displacement to more subtle revitalization with in-situ resettlement or new social mixes, which often cause what Fried (Citation1968) called a sense of “lost home” for neighborhood residents. A central inquiry for UR studies concerns whether and how residents’ emotional and affective bonds to their neighborhood are changed by the renewal process. Informed by gentrification theories, extensive UR studies have documented adverse outcomes of redevelopment-induced direct eviction or exclusionary displacement (Dossa & Golubovic, Citation2019). The implicit assumption is that physical displacement is the primary cause of residents’ weakened sense of place (SoP) or place attachment to their post-renewal residence.

A growing body of studies challenges this assumption by differentiating between the physical and psychological dimensions of displacement. As Davidson (Citation2008) argued, loss of “place” does not equal loss of “space.” Displacement is not always caused by spatial dislocation; it can also result from socio-spatial restructuring (e.g. changes in the social mix and local amenities) that can disconnect residents from their neighborhood (Davidson, Citation2008; Shaw & Hagemans, Citation2015). As such, stay-put residents in redeveloped neighborhoods or neighborhoods where the social mix changes may still experience a sense of lost home.

The displacement literature enhances the understanding of the socio-psychological costs of UR by turning the inquiry about the relationship between physical dislocation and place attachment into a question about the effects of neighborhood restructuring on neighborhood attachment (NA). Nonetheless, existing UR studies mainly focus on redeveloped neighborhoods and relocated residents (Atkinson, Citation2015; Elliott-Cooper et al., Citation2020; Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013; Slater, Citation2013; Zhang, Citation2018). A growing number examine the experiences of stay-put or returned residents in socially mixed neighborhoods where gentrification has been gradual and less visible (see Shaw & Hagemans, Citation2015; Wang & Wu, Citation2019). Further, whereas extensive research focuses on the impact of social restructuring (e.g. new social mixes) on post-renewal community sentiment (Freeman & Braconi, Citation2004), changes in non-social aspects (e.g. the built environment and the economic aspect) of community life remain understudied.

Scholars note that UR is often accompanied by improved housing conditions and neighborhood environment, and hence may provide “personal betterment” or opportunities for disadvantaged residents to improve their dwelling quality (Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013). Further, legal compensation mechanisms and other forms of community support may mitigate some of the negative effects of forced relocations (Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2019). Other scholars believe it is perceived changes in the living environments and lived experiences, rather than their material betterment, that are essential to residents’ SoP (see discussion in Shaw & Hagemans, Citation2015). Post-renewal experiences are also conditioned upon individual residential mobility factors, such as pre-relocation moving intentions, residential satisfaction (Kleinhans & Van der Laan Bouma-Doff, Citation2008), and socio-economic status (Kearns & Mason, Citation2013).

The debate about UR and loss of SoP raises several questions: Can UR without physical displacement and the remaking of social classes achieve the dual goals of neighborhood revitalization and community preservation? How do changes in the social and built environments (BE) of neighborhoods affect residents’ post-renewal NA? Can residents’ loss of place be offset by improvements to their built environment or personal finances? By dissecting different components of UR, we address questions on how the different dimensions (e.g. social, physical, economic) of neighborhood change and the scale of change (re)shape place attachment. This study contributes to the theoretical debates on UR by examining the post-renewal NA of Chinese residents in Guangzhou. It is among the first studies to systematically assess community outcomes by comparing two distinct UR modes in China. In doing so, it complements the existing UR literature, which is situated mainly in the Western context.

Following a long period of intensive redevelopment in the 1990s and early 2000s, China entered an era of “micro-renewal,” which involved an area-based approach to renovating old and dilapidated neighborhoods (State Council of PRC, Citation2020), without resettling residents (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2015). Most of these neighborhoods were built before 2000 and considered by local governments to need repair or upgrade. They contain many traditional housing units built before the founding of the country in 1949, as well as former socialist work unit housing. Unlike Western social mixing projects or wholesale redevelopment projects in China, micro-renewal involves little new-build development and rarely results in new social mixes or social class re-making.

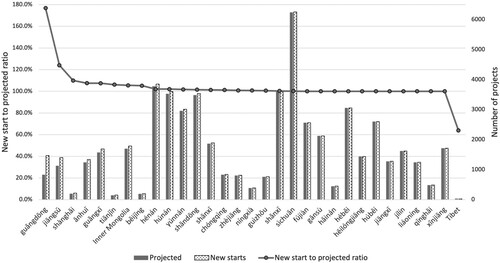

In 2021, 31 provinces and regions initiated a total of more than five thousand micro-renewal projects, which exceeded the national annual target (MHURD, Citation2022) (). The number of new projects initiated increased by 40% from 2020 to 2021. Guangdong province, where this study is situated, outperformed the target by 177%, which was the highest of all regions and indicates a rapid pace of micro-renewal in this province (). The growing prominence of micro-renewal projects in China’s urban agenda offers valuable opportunities to examine how the different modes of UR may have different effects on place-based sentiment.

Urban renewal and neighborhood attachment

The displacement literature uses different terms to describe a sense of lost home or lost community, such as “loss of SoP” (Davidson, Citation2008), “symbolic displacement” (Atkinson, Citation2015), “un-homing” (Elliott-Cooper et al., Citation2020) and “domicide” (Porteous & Smith, Citation2001). Underpinning these concepts is an erosion of place attachment, i.e. a weakening of emotional and affective bonds between people and place, wrought by neighborhood transformations. However, recent studies on urban restructuring and relocation suggest that post-renewal place-based experiences are more complex than the predominantly negative loading attached to the displacement concept used in a gentrification context (Kearns & Mason, Citation2013; Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013).

Relocation studies conducted in China have also revealed mixed outcomes, with some showing that resettled residents perceived improvements in their living conditions and residential satisfaction (Li & Song, Citation2009), while in other cases, satisfaction (Fang, Citation2006), social ties and sense of neighborhood cohesion decreased (Liu et al., Citation2017). These inconsistent findings demonstrate the need for a holistic framework that considers the various confounding factors of residents’ post-renewal experiences (Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013). This study employs the concept of neighborhood attachment (NA), defined as a positive, affective bond an individual develops toward their neighborhood and their tendency to remain proximate to that place (Hidalgo & Hernández, Citation2001). We examine changes in NA before and after renewal projects.

Three bodies of literature pertaining to the relationships among UR, neighborhood change and NA inform our research: gentrification-induced displacement, symbolic displacement, and neighborhood restructuring and place attachment. Due to the paucity of studies on post-renewal community outcomes in urban China, we draw on UR studies outside China, mindful that the relevance of these findings to Chinese contexts may be limited.

Neighborhoods continue to be an important arena for nurturing mutual trust and reciprocity among residents (Hazelzet & Wissink, Citation2012), even as growing urbanity and modernity liberate personal networks from the constraints of the neighborhood. Community social capital (CSC), i.e. shared norms and social trust among residents (Putnam, Citation2000), may be fostered through place-based social identities, such as membership in village committees or homeowners’ associations, or through the articulation of collective interest (Zhu et al., Citation2012). From a social capital perspective, mutual trust and social cohesion among residents form the social foundation of NA, i.e. people are attached to a place because they feel socially integrated into the local community or simply because they enjoy the general social milieu and connectedness among residents (Zhu et al., Citation2012). In different contexts, including Europe (Davidson, Citation2008), Australia (Atkinson, Citation2015), and China (Zhang, Citation2018), UR is often associated with changing social dynamics within a neighborhood, resulting in a loss of SoP.

However, scholars disagree on the factors that drive social-psychological disruption. In the gentrification literature, studies have focused on how place-based social ties are detrimentally affected by the physical displacement induced by redevelopment (see Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013). Similarly, studies in China have found that relocatees of redevelopment projects tend to experience a weaker sense of attachment to their new neighborhood and a lower level of social interaction within it (Li et al., Citation2019). This relocation-focused approach assumes that the absence of physical displacement would ameliorate the social costs of redevelopment projects, thereby justifying urban renewal through social mixing with in-situ resettlement (Shaw & Hagemans, Citation2015).

The symbolic displacement literature, exemplified by the works of Davidson (Citation2008) and Atkinson (Citation2015), suggests that social capital can be eroded even without physical dislocation when UR results in a remaking of a neighborhood’s social mix or social class. This can happen when, on one hand, the services and amenities catering to the original residents, especially those with low incomes, diminish after middle-class residents move in, thereby shrinking opportunities for social interactions and support among original residents and changing overall neighborhood dynamics (Davidson, Citation2008; Shaw & Hagemans, Citation2015). On the other hand, existing social norms and cohesion may be disrupted when tensions arise between original and new social groups (see Li et al., Citation2019). The low-income residents who rely on their local networks for social support and resources are more likely than the new, middle-class residents to feel the impact of UR-induced social disruption. Davidson (Citation2008) considers this form of “social displacement,” to be one of the essential dimensions of displacement.

Place attachment can also arise from the meanings that individuals attach to the physical environment. As scholars (Stedman, Citation2003; Zhu, Citation2015) have argued, people can develop bonds based on appreciation of an overall neighborhood environment, regardless of their social embeddedness there. With the trend toward privatism and individualism, BE may carry more weight than social intimacy when it comes to cultivating a sense of home. Studies show that in post-reform China, residents perceive urban neighborhoods as less of a source of social support and personal contact. Rather, SoP is often articulated through satisfaction with the physical environment that they have endowed with economic, social, or symbolic meanings (Zhu, Citation2015; Zhu et al., Citation2012).

In UR literature, the relationship between BE changes and post-renewal NA has been under-studied and findings are inconclusive. UR may result in a cleaner environment, reduced crime and disorder, an increased range of products and services, and an improved sense of security (Shaw & Hagemans, Citation2015), consequently strengthening residents’ NA. However, the symbolic displacement literature posits that commercial and aesthetic changes, along with other physical upgrading, estrange residents from a once familiar or affordable neighborhood, leading to “neighborhood resource displacement” (Davidson, Citation2008). As Marcuse stated (Citation1985, p. 207), displacement pressure emerges,

“when a family sees the neighborhood around it changing dramatically, when their friends are leaving the neighborhood, when the stores they patronize are liquidating and new stores for other clientele are taking their places, and when changes in public facilities, in transportation patterns, and in support services all clearly are making the neighborhood less and less liveable.”

Existing studies suggest that groups with limited economic and political power, including the urban poor, women, and ethno-religious minorities, are the most vulnerable to gentrification and displacement processes (Doshi, Citation2013; Wu, Citation2016). In China, the right to city space is often stratified along the lines of income, connection to state power, and household registration (hukou) status (Liu et al., Citation2017; Zhu, Citation2014). Low-income households and migrants, therefore, are more susceptible to UR impacts. Women are more likely to report a higher degree of residential satisfaction than men after redevelopment (Li & Song, Citation2009), but gender does not seem to be a significant determinant of NA (Zhu et al., Citation2012).

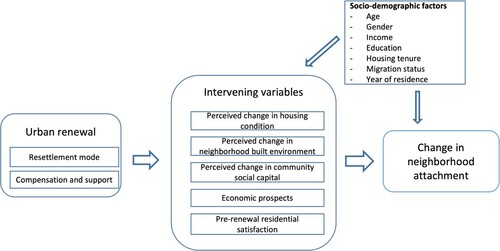

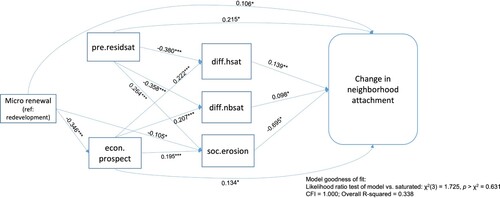

These literature strands lend credence to the framework () we used to examine the change in NA of affected residents in different renewal contexts. We present specific research hypotheses in the Data and Methods section. Overall, however, we expected UR-induced NA change to be directly associated with perceived changes in CSC, housing satisfaction, and BE satisfaction. The effects of these factors are also contingent on pre-renewal experiences, economic prospects, mode of UR, and household socio-demographic factors.

China’s policy shift from wholesale redevelopment to micro-renewal

The evolution of China’s UR policies can be divided into two primary phases since the 1990s: wholesale neighborhood redevelopment that was significantly intensified and swept major cities during the first decade of the twenty-first century, and recently a comprehensive UR scheme with an emphasis on BE rehabilitation and community participation (Zhao et al., Citation2021; Zhu et al., Citation2022). This policy shift responded to the national government’s The New-type Urbanization Plan 2014–2020, which emphasized humanism and community participation as core aspects of the nascent new-type urbanization. The government’s amendment to the Land Administration Law of 2019 reaffirmed requirements for transparent land requisition, community participation, and fair compensation. This triggered growth in the trend toward micro-renewal without physical displacement. The State Council’s Guiding Opinions on Fully Promoting the Renovation of Old Urban Neighborhoods, issued in 2020 (State Council of PRC, Citation2020), elevated micro-renewals to a new level. It set a target of starting the renovations of 39,000 old and dilapidated neighborhoods – involving around seven million households across China – in 2020 (this objective was 100% achieved), and completing renovations of all designated dilapidated neighborhoods by 2035. While regional approaches and governance models for UR vary, wholescale redevelopment and micro-renewal represent two distinct modes of UR that differ both in scale and substance.Footnote1 Below we review the policy evolution, goals, and context of each.

Since the 1980s, local fiscal constraints resulting from fiscal decentralization, coupled with booming real estate demand and land market reform, triggered rampant rent-seeking behaviors by local governments through property-led redevelopment projects (Fu, Citation2015). More than 12 million households in China were affected by urban redevelopment between 2008 and 2012 (Li et al., Citation2019). In 2009, the Guangzhou municipal government became the first to launch a scheme to redevelop the “three-olds,” i.e. old towns, old villages, and old factories. The plan was to completely demolish and reconstruct more than ten million square meters of built-up area, including relocating the six hundred thousand people affected by 2020 (He, Citation2012). According to Guangzhou’s city government, redevelopment is a mode of UR that involves complete demolition and reconstruction (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2015). It targets neighborhoods in locations considered to impede its political agenda of industrial upgrading or world city building (GZURB & GZPDI, Citation2015a). In 2013, an estimated 40% of new construction land and two-thirds of Guangzhou’s land-conveyance revenues came from three-old projects (GZURB & GZPDI, Citation2015a).

In the early years of urban redevelopment, local governments were allowed to demolish private properties if they could not reach an agreement with the occupying household (State Council of PRC, Citation2001). The forced demolitions and unfair compensation that were common in these early years of UR resulted in massive displacement and subsequent resistance from local communities. The most contentious redevelopment projects occurred in urban villages. Unlike old and dilapidated neighborhoods that have long been part of cities, urban villages are former rural settlements previously located at the urban fringe, where peasants subsisted through agricultural activities organized by village collectives. As urban expansion encroached upon these settlements, the state confiscated much of the farmland or converted it to urban uses. However, the residential land remained intact, eventually becoming islands of settlement surrounded by urban landscapes. Having lost farmland, peasant villagers often exercised informal landlordism by renting informally constructed residential spaces to migrant workers who otherwise could not afford housing in the city (Zhu, Citation2014). The redevelopment of urban villages therefore often resulted in the eviction of millions of migrant tenants and led to property disputes among villagers, private developers, and the local government.

In 2011, China’s central government issued the Regulation on the Expropriation of Housing on State-owned Land and Compensation, which prohibited forced demolition and set new regulations to safeguard fair compensation and the interests of property owners (State Council of PRC, Citation2011). Similarly, The Guangzhou government mandates the participation of property owners in decision-making, information transparency, and profit-sharing. Meanwhile, standards for market-based compensation for the demolition of existing buildings were established (GZURB, Citation2016). However, the actual engagement of homeowners and landlords remains limited, and renters are excluded from the decision-making process (Ye et al., Citation2021). Forced demolition can still occur in the name of “public interests,” which are subject to interpretation by local authorities (Han et al., Citation2018). Han et al. (Citation2018) found that most illegitimate housing demolition cases are related to (re)development projects.

Compensation schemes vary depending on local policies and the bargaining power of local community groups. In general, eligible households (mostly property owners) can choose in-kind or cash compensation, or both. In-kind compensation comes in the form of resettlement housing (ex-situ or in-situ) equivalent in size to a household’s legal floor areas, up to the official maximum standard. Legal floor areas are calculated based on the site area of a household’s residential building plot, multiplied by the number of stories. In Guangzhou, the maximum height of urban village residential buildings eligible for compensation is four stories. Floor areas above the maximum height are considered illegal and ineligible for compensation (Li et al., Citation2014). Most redevelopment projects in Guangzhou offer in-situ resettlement. For those involving ex-situ resettlement, the government often relocates residents to urban peripheries. Households that prefer cash compensation receive it based on the legal size of their demolished floor areas, with compensation rates varying by location of the redevelopment site (e.g. generally around 15,000 CNY/m2). Relocatees may also receive subsidies aimed at helping them find temporary accommodation during the redevelopment period.

Different compensation schemes result in different post-renewal outcomes. Households that are resettled to periphery areas have been found to suffer from poor housing conditions and neighborhood maintenance (Fang, Citation2006; Li et al., Citation2019), as well as worsened financial situations due to the inaccessibility of job opportunities and public facilities (Day & Cervero, Citation2010). By contrast, households that are resettled on-site, especially if in prime locations, tend to receive generous compensation, sometimes multiple new apartments (Li et al., Citation2014). It is not uncommon that households receiving in-kind compensation may significantly improve their financial situations. In 2017, Guangzhou local media has reported that some villager households had received up to 20 new apartments as compensation, thereby becoming rich property rentiers.Footnote2 This phenomenon is substantiated in our case study. Multiple residents indicated they received more than one housing unit as compensation for their owned legal floor areas. The additional dwelling units provide an essential and sustainable source of income for these households. Gentrification following redevelopment may further lead to an appreciation of property values and rent incomes, further improving the finances of these households.

However, such property-based income is often unavailable to households who choose cash compensation. In our neighborhood survey, only 20% of households affected by redevelopment who received cash compensation identified rents as income sources, compared to 51% of those with in-kind compensation. Also, while many households might welcome redevelopment as a way to upgrade their living conditions and increase their incomes, only homeowners and landlords are eligible for these compensation schemes. The majority of residents without property rights, such as renters and rural migrants, are ineligible for compensation and are likely to face eviction. In some urban village redevelopment projects, such as Pazhou village in our case studies, the village collective can sometimes generate extra revenues from its collectively owned commercial and business premises and distribute those to villager shareholders as welfare or dividends (Shin, Citation2016).

The National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020) marked another significant shift in the guiding ideology of urbanization in post-reform China. In response, Guangzhou adopted a new UR scheme to achieve the dual goals of social stability and economic growth. In 2015, the Guangzhou municipal government put forward the concept of micro-renewal to renovate neighborhoods by rehabilitating infrastructure, changing building functions, and overall upgrading, while minimizing demolition and reconstruction (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2015).

In contrast to wholesale redevelopment, which primarily serves the objective of economic growth and advancing industrialization (Zhu et al., Citation2022), the policy discourses around micro-renewal were to achieve social sustainability by enhancing residents’ “sense of fulfillment, sense of security, and happiness” (Guangdong Provincial Government, Citation2021). Micro-renewal projects do not involve private properties or household resettlement and mainly target aged and deteriorated neighborhoods (especially those built before 2000) that do not occupy “strategic locations” (GZURB & GZPDI, Citation2015b).

In its national UR guideline, the State Council (2020) classifies micro-renewal into three levels (). Level one is basic rehabilitation includes maintenance and repair of existing infrastructures and shared properties that impact residents’ lives and security, such as utility supply, road repairs, and exterior wall refurbishing. Next, the improvement level aims to provide residents with increased convenience and quality of life by renovating BE and infrastructure, building retrofitting, and improving energy efficiency. These projects include demolition and reconstruction of illegal buildings, and improvements to accessibility, neighborhood green spaces, lighting, age-friendly facilities, parking lots, and recreational or fitness facilities. At the third level – upgrading – micro-renewal primarily consists of providing neighborhood amenities and services, such as health and childcare facilities and convenience stores. The specifics of each micro-renewal project are determined by the local government in consultation with residents (primarily homeowners). Depending on the goal and scope of the project, micro-renewal in Guangzhou may rely on government financing (especially for the basic rehabilitation level), social capital, and/or resident self-financing (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2021).

Table 1. The goals and scope of micro-renewal.

Wholesale redevelopment and micro-renewal are essential components of an integrated UR strategy to “promote Guangzhou’s city competitiveness and sustainable development” (GZURB & GZPI, Citation2015b). The Guangzhou government established a new Urban Renewal Bureau in 2015 to lead, coordinate, and facilitate its city-wide UR scheme (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2015). While continuing redevelopment seeks to re-capitalize the inner city for industrial upgrading and economic growth, the emerging micro-renewal approach aims to maintain social stability and sustainability through BE improvement (Ye et al., Citation2021). As of 2020, the Guangzhou government had initiated 323 micro-renewal projects involving 484 neighborhoods. The renewal of old neighborhoods was to be completed by 2025, with 183 urban villages to be redeveloped by 2030 (GCCCPC, Citation2020).

While social mixing as an approach to poverty de-concentration has been implemented in redevelopment projects in many Western contexts, it has not been part of the policy discourse or an objective in China. However, new social mixes are often an immediate, though not necessarily intended, outcome of redevelopment projects due to the displacement of original residents and new-build gentrification (Zhu et al., Citation2022). Social class remaking is either not present or less visible in the process of micro-renewal.

Data and methods

Surveys and interviews

This study draws on a survey of 639 residents in eight Guangzhou neighborhoods, as well as semi-structured interviews of residents in three of those neighborhoods.Footnote3 Our goal for both the survey and the interviews was to understand how perceived changes in neighborhood built versus social environments mediated the effects of different modes of UR and resettlement on residents’ NA.

We selected the neighborhoods based on the type of renewal they had undergone (redevelopment versus micro-renewal) and location (inner city versus suburb). Five of the neighborhoods are in the inner city, and three in the suburbs. All redevelopment neighborhoods in the survey are urban villages. Among the micro-renewal neighborhoods, Yongtai and Pantang are urban villages, and the other three are dilapidated traditional neighborhoods or former work unit compounds. The levels of micro-renewal projects range from the basic (Pantang) to the improvement (Dunhe and Yinggang) to upgrading (Yongtai and Jiunanhai).

Between June 2020 and January 2021, we worked with neighborhood Residents Committees (juwei)Footnote4 and local scholars to conduct our fieldwork with the assistance of college students. Our survey targeted households and residents who were 18 years or older and had lived in the same neighborhood before renewal. The survey solicited retrospective information from the respondents on their residential history and experiences before and after renewal ().

Table 2. Case study neighborhoods for survey and interview fieldwork.

Within each neighborhood, it was not feasible to conduct systematic random sampling due to the lack of a complete list of households. Therefore, following existing neighborhood research in China (e.g. Wang & Kemeny, Citation2022; Zhu et al., Citation2012), we adopted an interval sampling strategy to recruit households. Also, under China’s zero-COVID policy, strict community mitigation measures in some neighborhoods meant that we could not visit households; hence, we carried out interval sampling in these neighborhoods in communal and public spaces such as parks and playgrounds.Footnote5 Where household visits were allowed, the research team worked with juwei or villagers’ committees to select housing units from each residential building using interval sampling. We set the intervals, e.g. 1 in 3 or 1 in 5 households, based on the size of the neighborhood and the number of households on each floor. The interval sampling allowed us to maximize the spatial and demographic coverage of household samples. The average response rate was 47%. The number of respondents in each neighborhood ranged from 62 to 91 households, representing between 4% to 30% of households affected by UR projects, according to estimates by neighborhood representatives. All questionnaires were administered in person by trained interviewers to ensure respondents understood questions consistently.

We then selected three out of the eight surveyed neighborhoods in which we conducted follow-up qualitative interviews. We chose these neighborhoods because survey respondents in these areas had indicated their willingness to participate and had left contact information. The neighborhoods were as follows: Tancun, a redeveloped urban village, where we conducted 13 interviews; Pantang, which had gone through micro-renewal with basic rehabilitation (14 interviews); and Yinggang (20 interviews), which had micro-renewal at the improvement level. Our interviews focused on residents’ lived experiences before and after renewal. They were conducted in person or over the phone, depending on respondents’ preferences. Each interview was conducted by two trained interviewers. We triangulated these qualitative findings with the survey findings to better understand UR’s socio-psychological impact.

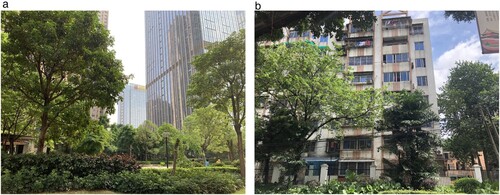

Neighborhood profiles of case studies

Tancun (a) was the last redeveloped urban village near Guangzhou's new central business district (CBD). The project, which began in 2012 and ended in 2017, was led by the municipal government and the village collective. It was financed by a private developer, involving an investment of 0.8 billion CNY on a total land area of 8.3 ha. About 2,000 villager households were involved in the project, most of whom were resettled on-site with compensation. Ninety-five percent of villager households signed the agreement with the developer.

Figure 3. Images of two case study neighborhoods (Taken by author in 2021). a: Tancun (redevelopment). b: Yinggang (micro-renewal).

Pantang is an inner-city urban village. The municipal government initiated a plan to redevelop Pantang in 2007 but aborted it in 2013, though a few hundred households were relocated. Following that failed redevelopment attempt, the Guangzhou government led and financed another attempt to renew Pantang in 2017, using a micro-renewal approach. Pantang’s micro-renewal was at the basic level and focused on the rehabilitation of infrastructure and exterior building walls.

Yinggang neighborhood (b) is a former socialist work unit compound built in the 1980s. It has 428 households. Its micro-renewal at the improvement level was completed in 2019 and covered infrastructure rehabilitation and renovations in shared spaces.

Profiles of survey respondents

Survey respondents were of varied ages, with those 55 years and above accounting for less than 50% of the respondents (). About one-third of respondents had received post-secondary education. Over half were women. The majority of respondents were homeowners (85%), and more than 88% held a local hukou. About 70% of respondents reported an annual income of at or below the average 2019 annual income for Guangzhou, which was 60,000 CNY or less. There did not appear to be systematic differences between the profiles of respondents in the redevelopment and micro-renewal neighborhoods.

Table 3. Profiles of survey respondents by neighborhood.

Among the three redeveloped urban villages, respondents in Pazhou had the highest income level and were relatively young, educated, and primarily male. The higher income of respondents in this village is likely attributable to the fact that its location near the CBD allowed villagers to collect high rents from their properties and generate extra revenues from their collectively owned commercial premises. . Tancun respondents tended to be older, less educated, low-income, and female. Luogang respondents were the youngest and the most educated overall but had the lowest income level. Luogang also had a good gender mix and a higher proportion of renters than the other two villages.

Among the five micro-renewal neighborhoods, respondents in Yongtai were young, mostly women, less educated, and the poorest compared to the overall respondent profile. Pantang had higher percentages of seniors, homeowners, men, and a relatively high proportion of low-income residents. Dunhe’s respondents were diverse in terms of age, education, and gender. This neighborhood also had a lower percentage of low-income households. Yinggang’s respondents were relatively young and had received more education, although were less wealthy. Respondents in Jiunanhai tended to be seniors, while there was a mix of educational levels, age groups, and incomes.

Measures and variables in survey data

summarizes the key variables we used to analyze the survey data, followed by definitions and measures of key concepts. All variables concerning perceived neighborhood change and experience were based on retrospective survey responses. We tried to minimize the cognitive effort respondents needed to answer our retrospective questions, such as by providing recall anchor points and minimizing the survey length. While retrospective questions may introduce measurement errors at the individual level, a recent study showed that at the aggregate level, retrospective information is more consistent and reliable (Hipp et al., Citation2020).

Table 4. Key variables in survey data analysis.

NA Change (diff.nbattach). To measure NA, we asked survey respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following four statements about their pre – and post-renewal neighborhoods, respectively, using a five-level Likert scale: “Overall, I feel a sense of home in this neighborhood;” “If I had to move, I would miss the people in the neighborhood;” “If I had to move, I would miss the environment of the neighborhood;” and, “I feel I am a part of the community.” The Cronbach’s Alpha of these statements shows strong internal consistency: 0.81 for post-renewal scores and 0.78 for pre-renewal scores.Footnote6 We calculated the change in NA by subtracting the before-renewal average from the after-renewal average. Overall, the survey respondents experienced a marginal increase in NA with a mean score of 0.4. About 16% of the sample had negative scores, indicating disrupted NA, compared to 39% with no change and 43% with an improved sense of attachment.

Perceived erosion of post-renewal CSC (soc.erosion). The level of community social capital (CSC) is indicated by perceived mutual trust and reciprocity among residents. We asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed (on a five-level scale) with four statements that compared the degree of CSC pre – and post-renewal. These four statements were: “Compared with the current neighborhood, residents in the pre-renewal neighborhood …

were more willing to help one another before the renewal.

had more interactions.

had stronger solidarity.

had a stronger sense of mutual trust.”

The Cronbach’s Alpha of these statements is 0.88, suggesting strong internal consistency. We used the mean score of the four items to indicate perceived change in CSC after the renewal: a higher score indicates a stronger sense of erosion in post-renewal CSC. This variable had a mean of 3.13, suggesting a weak sense of social capital erosion among respondents overall. Of the respondents, 43% reported a mean score of 4 or above, indicating perceived weaker CSC post-renewal, in contrast to 29% with a mean score below 3 disagreeing with the statements and 28% who were neutral.

Housing satisfaction change (diff.hsat). We assessed respondents’ satisfaction with their physical living environments regarding both their housing conditions and their neighborhood’s BE. For housing satisfaction, we asked respondents to rate their satisfaction on a five-level Likert scale regarding the size of living space and housing quality (e.g. lighting, kitchen, utilities) both before and after renewal. The Cronbach’s Alpha of the two questions was 0.77 for pre-renewal satisfaction and 0.7 for post-renewal satisfaction. Change in housing satisfaction is indicated by the difference in the satisfaction scores before and after renewal. The average change in housing satisfaction was 0.24, with 17% on the negative end and 35% on the positive end, suggesting that respondents were slightly happier with their housing conditions after UR.

Neighborhood BE satisfaction change (diff.nbsat). Change in satisfaction with the neighborhood BE was assessed using a five-level Likert scale for the following aspects: cleanliness, green spaces, low-cost recreation amenities, sense of safety, and neighborhood accessibility to public transit, and health care facilities. The Cronbach’s Alphas are 0.84 for post-renewal and 0.86 for pre-renewal, again showing high internal consistency of the two measures. We used the difference in the mean scores of respondents’ satisfaction with their pre – and post-renewal neighborhood BE to indicate the change in respondents’ neighborhood BE satisfaction. This variable has an average of 0.39, with 19% of the respondents on the negative end and 61% on the positive end.

Pre-renewal residential satisfaction (pre.residsat). To account for pre-renewal residential experience, we asked one question about respondents’ satisfaction with the overall environments of their neighborhoods before UR, rated on a five-level Likert scale. This variable is differentiated from diff.nbsat, which specifically measures satisfaction with the neighborhood’s BE. The average score of pre.residsat is slightly above neutral at 3.2, with 40% being satisfied and 23% being dissatisfied.

Economic prospects (econ.prospect). We used respondents’ self-assessments to indicate the economic impact of UR on their household finances. We asked respondents to “evaluate the general impact of the UR project on your family finances at a five-level scale (significantly worsen, somewhat worsen, no change, somewhat improved, and significantly improved).” About 5% reported a worse financial situation for their household, in contrast to 56% that felt no change and 39% who reported economic betterment.

Type of urban renewal (micro.renewal). This dichotomous variable indicates whether a neighborhood had wholesale redevelopment (micro.renewal = 0) or micro-renewal (micro.renewal = 1). About 60% of respondents were in a micro-renewal neighborhood.

Mode of resettlement (resettlement). We used this as a categorical variable to differentiate among resettlement modes. By policy design, there is a strong overlap between the types of UR and resettlement modes. Whereas the great majority of respondents (97%) in micro-renewal neighborhoods were not resettled, over 93% of respondents from redeveloped neighborhoods were resettled either on-site or off-site. In the three redeveloped neighborhoods, 31% of respondents were relocated from another neighborhood (ex-situ resettlement), and 62% were resettled on-site. Pazhou (43%) and Tancun (44%) had more respondents who were resettled from other neighborhoods. Among those who were not resettled in redeveloped neighborhoods, all were homeowners, and most chose cash compensation.

Type of compensation (compensation). This categorical variable indicates the different types of compensation received by affected households (1 = no compensation; 2 = in-kind only; 3 = cash only or other). Fifty-six percent of the respondents did not receive any compensation, and nearly all of these resided in micro-renewal neighborhoods. Only 7% of micro-renewal residents received some compensation. Almost all respondents in redevelopment projects received either cash (35%) or in-kind (35%) compensation, and 30% received both types. Auxiliary analyses revealed no significant differences in key outcome variables between those receiving in-cash compensation and those receiving both types of compensation; hence, we collapsed the two groups into one variable to improve model parsimony.

Socio-demographic control variables In the survey data analysis, we also accounted for socio-demographic variables that may affect post-renewal residential experiences. These variables include age groups, gender (1 = female; 0 = male), income level (5 interval groups), migrant status (1 = non-local hukou; 0 = local hukou); education (1 = college and above; 0 = below college); housing tenure (1 = owner; 0 = other); and years of residence in the current neighborhood.

Path analysis modeling and hypotheses

We performed two path analysis models to ascertain the relationship between UR and NA. Path analysis is a regression technique that allows researchers to parse direct and indirect relationships among variables (Bowen & Guo, Citation2011). Unlike conventional regression models with only one dependent variable, path analysis models interrelationships among multiple observed dependent variables (i.e. endogenous variables), which are subject to the effects of exogenous variables – variables determined by factors outside the model. For this analysis, we used Stata 17.0 with the SEM package, which produces outputs including model goodness of fit, direct and indirect effects, and standardized and unstandardized coefficients.

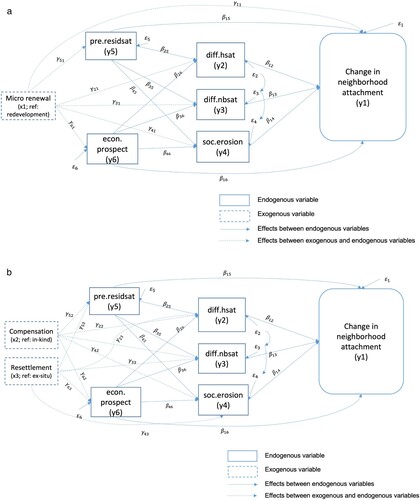

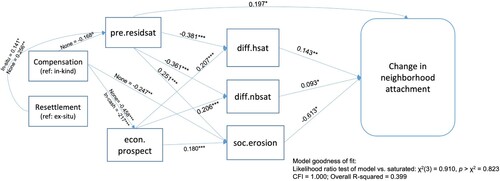

In Model 1, we ran a path analysis model to compare NA change between the two modes of UR. In Model 2, we replaced micro.renewal with resettlement and compensation variables to further decipher the effects of different aspects of renewal.

a and b show model specifications with corresponding coefficients of key variables to be estimated. Arrows should be interpreted as hypothesized associations, rather than causality, among variables based on the theoretical framework. Endogenous variables include the outcome variable – perceived NA change, and intervening variables that mediate UR and NA – three variables measuring housing and neighborhood changes (i.e. diff.hsat, diff.nbsat, and soc.erosion), pre-renewal residential satisfaction (pre.residsat), and post-renewal economic prospects (econ.prospect). These endogenous variables were regressed on exogenous variables, including UR mode, type of compensation, resettlement mode, and socio-economic control variables.

Figure 4. (a) Specifications of path analysis Model 1 (Step 1). (b) Specifications of path analysis Model 2 (Step 2).

Limited quantitative research in the literature and model complexity precluded the development of research hypotheses about each variable. However, we derive the following general hypotheses from the literature to guide the analysis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Residents in micro-renewal neighborhoods are more likely to experience improved NA than those in redevelopment neighborhoods.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Post-renewal NA change is directly and positively associated with perceived changes in housing situation, neighborhood BE, and CSC.

Hypotheses 3 (H3): Effects of pre-renewal residential satisfaction and post-renewal household economic prospects on post-renewal NA are mediated by perceived changes in housing situation, neighborhood BE, and CSC.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Mode of resettlement and compensation are indirectly, rather than directly, associated with post-renewal NA through the effects of the intervening variables, i.e. diff.hsat, diff.nbsat, soc.erosion, pre.residsat, and econ.prospect.

Findings

Descriptive survey results

On average, residents in both micro-renewal and redevelopment neighborhoods expressed improved NA, with the micro-renewal residents reporting greater improvement (). However, this does not mean an absence of NA disruption. About 21% of respondents in redeveloped neighborhoods expressed diminished NA, compared to 13% in micro-renewal neighborhoods (data not shown).

Table 5. Mean change in neighborhood attachment by key variables.

Residents relocated from a different neighborhood (i.e. ex-situ resettlement) generally reported the lowest degree of improved NA, whereas those who were not resettled reported the greatest increase. Residents who received cash or other compensation reported the weakest improvement in post-renewal NA. Those who received no compensation were on par with those who received in-kind compensation.

Simple Pearson correlation coefficients suggest NA change was positively associated with changes in satisfaction with housing and neighborhood BE, and negatively associated with perceived erosion of CSC. Pre-renewal residential satisfaction showed a weak negative correlation with NA change, in contrast to a positive correlation coefficient of post-renewal economic prospects. NA change is negatively associated with years of residence in the neighborhood.

All socio-demographic groups reported a slight improvement in NA. While females and the less educated reported greater improvement in NA, no substantial differences were revealed between homeowners and renters, migrants and locals, or low – and high-income groups.

Path analysis results

Model 1 results are presented in (standardized effects) and (unstandardized effects). The goodness of fit statistics suggests a satisfactory performance of the path analysis model, with an overall R-squared of 0.338 and a Comparative Fit Index (CFI)Footnote7 of 1.000. Standardized effects allow us to compare the magnitude of effects between variables measured with different scales. Only statistically significant results are shown in . gives unstandardized direct, indirect, and total effects. The total effect of a variable is the sum of its unstandardized direct and indirect effects on an outcome variable.

Figure 5. Path analysis result (Model 1), standardized effects.

Notes: ap<0.1; * p<0.05; ** p< 0.01; *** p< 0.001.

Table 6. Unstandardized effects (Model 1).

Table 6. Continued

The total effect of micro.renewal () suggests that residents in micro-renewal neighborhoods were more likely than those in redeveloped neighborhoods to experience improved NA, controlling for other confounding factors. This confirms H1, which posits less disruptive effects of micro-renewal than redevelopment. Indirect effects of micro.renewal on post-renewal NA can be negative via mediation effects of econ.prospect or positive through the pathway of pre.soc (). As shown in , micro-renewal residents were less likely than those in redeveloped neighborhoods to perceive disruption of CSC (coef.micro.renewal = −0.105), which helps preserve NA. However, micro-renewal residents were less likely to report economic betterment (coef.micro.renewal = −0.346), which was positively associated with post-renewal NA. Moreover, micro.renewal showed a positive direct effect on NA (coef.micro.renewal = 0.106). This remaining direct effect may be explained by resettlement and compensation, which will be analyzed below.

Model 1 findings support H2 that post-renewal NA is directly and positively associated with perceived positive neighborhood changes. Among the three neighborhood change variables (), soc.erosion presents the strongest explanatory power (coef.soc.erosion = −0.695). Residents who perceived a stronger erosion of CSC in the post-renewal neighborhood were much less likely to experience improved NA. Increased satisfaction with post-renewal housing (coef.diff.hsat = 0.139) and neighborhood BE (coef. diff.nbsat = 0.098) were positively associated with improved NA, although magnitudes of these effects were weaker compared with soc.erosion.

Pre-renewal residential satisfaction (pre.residsat) and post-renewal household economic prospects (econ.prospect) influenced NA change both directly and indirectly (), partially supporting H3. Direct effects of pre.residsat (coef.pre.residsat = 0.215) and econ.prospect (coef.econ.prospect = 0.134) on post-renewal NA were positive and significant. These two variables had negative indirect effects through pathways of perceived neighborhood changes (). The more a person was satisfied with their pre-renewal neighborhood, the less likely that person was to perceive positive changes in housing satisfaction (coef. = −0.380) and neighborhood BE (coef. = −0.358). However, they were more likely to perceive erosion of CSC (coef. = 0.251), resulting in a negative indirect effect of pre.residsat on post-renewal NA (). Improved family economic prospects after renewal tended to enhance post-renewal satisfaction with housing (coef. = 0.222) and neighborhood BE (coef. = 0.207) (). However, econ.prospect shows a positive association with a sense of CSC erosion (coef. = 0.195), which disrupts NA. This is not surprising. In the context of China’s UR, household financial improvement tends to result from the compensation the household receives for a home demolition caused by redevelopment, which often changes social dynamics.

In Model 2 (, ), we replaced micro.renewal with compensation and resettlement variables. Model performance was satisfactory based on goodness of fit, with an overall R-squared of 0.399 and CFI of 1.000.

Figure 6. Path analysis model result (Model 2), standardized effects.

Notes: ap<0.1; * p<0.05; ** p< 0.01; *** p< 0.001.

Table 7. Unstandardized effects (Model 2).

Table 7. Contined

The effects of intervening variables remained robust, except that the direct effect of econ.prospect became non-significant, likely because its effect was moderated by the compensation variable. The two UR variables did not directly impact post-renewal NA. Their effects were mediated by intervening variables, supporting H4. Resettlement was only significantly associated with pre-renewal satisfaction. In-situ relocatees (coef. = 0.141) and non-relocatees (coef. = 0.256) were more satisfied than ex-situ relocatees with pre-renewal residential environments (). This may be because residents who were dissatisfied with the original neighborhood had stronger motivation to move out, especially when provided with options for ex-situ and in-situ relocations in the redevelopment process. This implies a degree of decision-making agency of relocatees within a set compensation scheme (Li et al., Citation2019; Manzo et al., Citation2008). The direct associations between resettlement and neighborhood change variables (diff.hsat, diff.nbsat, soc.erosion) may be mitigated by the compensation variable because compensation recipients tend to be relocatees.

Compensation only exhibited indirect effects on post-renewal NA through soc.erosion, econ.prospect, and pre.residsat (, ). Residents who received no compensation were less likely to perceive CSC erosion, (coef.none = −0.247) () because compensation was usually accompanied by the demolition of homes and neighborhood restructuring. These results imply that material compensation cannot offset the perceived disruption of social capital. However, compensation indirectly influences perceived changes in housing conditions and neighborhood BE through econ.prospect. shows, compared with in-kind compensation, cash compensation is negatively and indirectly associated with diff.hsat (coef. = −0.116) and diff.nbsat (coef. = −0.099). The direct effect of the compensation variable also shows that in-kind compensation was more likely than no compensation (coef.none = −0.458) and cash compensation (coef.in-cash = −0.217) to result in household financial improvement (). To contextualize these results, because Guangzhou’s redevelopment projects were mainly in prime locations, affected residents who were compensated with new on-site properties tended to receive the double benefit of an improved residential environment in the short-term term, along with economic gains from renting out extra residential space over the long term. These benefits were not available to those who received only cash compensation or no compensation at all.

Receiving compensation was negatively associated with pre-renewal residential satisfaction (coef.none = −0.168), but the effect was only marginally significant (). A plausible explanation is that higher pre-renewal residential satisfaction may have translated into stronger resident motivation to negotiate better compensation (Li et al., Citation2019). Overall, cash compensation was less likely than in-kind compensation to improve NA, as suggested by its total effect (coef.in-cash = −0.176), although the relationship was marginally significant (). This indicates that in-kind compensation was more effective than cash in mitigating the disruptive effects of redevelopment, to the extent that it enhanced post-renewal financial outcomes and residential satisfaction.

In terms of socio-demographic factors ( and ), female and higher-income groups were more likely to experience improved NA. Those who were better educated and had a long residential history were less likely to experience positive NA change. We found no significant differences between owners and renters, migrants and locals, or age groups. Residents with longer years of residence were less likely to experience other positive post-renewal community outcomes regarding housing and neighborhood satisfaction, perceived CSC, and financial betterment.

In sum, the total effects of the path analysis models corroborate an overall more positive NA outcome from micro-renewal than redevelopment (H1). The different community outcomes can be parsed into indirect effects of compensation and resettlement variables, as suggested by Model 2 results. Perceived housing and neighborhood changes were strong direct predictors of post-renewal NA (H2). Regarding pre-renewal residential satisfaction and post-renewal financial betterment, their positive direct effects are offset by their negative indirect effects (through soc.erosion), leading to a non-significant total effect on post-renewal NA, which partially supports H3. As H4 posits, resettlement and compensation influenced NA through intervening variables. The total effect of resettlement on post-renewal NA was non-significant, suggesting physical dislocation is not a necessary condition for disrupted NA. The negative association between cash compensation and economic betterment (with in-kind compensation as a reference group) led to an overall negative total effect of cash compensation on post-renewal NA, whereas those receiving in-kind compensation showed no difference in NA change compared to those with no compensation (e.g. the micro-renewal group). This suggests that the role of compensation in offsetting or mitigating socio-psychological costs of UR is conditional on whether it provides sustainable, rather than one-off, economic benefits.

Semi-structured interviews

Respondents in our three case study neighborhoods generally expressed an improved sense of belonging to their neighborhood after renewal. Confirming survey findings, more residents from the two micro-renewal neighborhoods reported improved NA than in the redeveloped neighborhood, owing to having better housing and neighborhood environments, as well as preserved social connections among original residents.

Most interviewees in the micro-renewal neighborhoods (Pantang and Yinggang) felt a stronger sense of belonging to their post-renewal neighborhood. Many attributed this to having a better neighborhood environment and a stronger sense of security due to upgrades to their BE. These interviewees suggested that micro-renewal does not disrupt pre-existing social relations among residents. Some felt micro-renewal positively affected their neighborly interactions because of BE upgrading (e.g. cleaner environment, additional recreational facilities) and more space and opportunities for interaction:

“I am more willing to come out since the community is so clean now. I appreciate that we have a community stage where the neighbors can enjoy Cantonese opera.” – Male, 70s, native to Pantang, homeowner.

“I feel a stronger sense of home now because the neighborhood is cleaner and tidier, and the rough roads were fixed too.” – Male, 40s, seven years in Yinggang, homeowner.

“I felt happier after the redevelopment. Now the government has taken the land, and I don’t need to work. (So you worked before, and now your income comes from rents?) Yes. … (Did the redevelopment improve your family’s financial situation?) Of course. Before it was redeveloped, the rent for the entire building was 6,000 yuan. Now one apartment can rent more than 6,000.” – Male, 60s, native villager, homeowner.

“I feel more attached now. The village was dirty and wet before, and trash was everywhere. I feel a stronger sense of belonging now … And the rents doubled, so my income increased too.” – Female, 50s, native villager, homeowner.

Consistent with our survey findings, residents frequently cited improved life quality due to better housing conditions and neighborhood environment (for both micro-renewal and redevelopment neighborhoods) and financial improvement (mainly for redevelopment neighborhoods) as benefits of these renewal projects. In contrast, residents often linked disrupted NA to changing social relations within their neighborhood across all cases.

Conclusions and discussion

UR and its effects on community sentiment have long been a focus of urban scholars. This study contributes to the current debate on the psychological dimensions of displacement by examining the relationships between neighborhood change and place attachment in urban China, juxtaposing the two approaches of micro-renewal and wholesale redevelopment.

We found that micro-renewal is much less likely than redevelopment to disrupt NA. But what distinguishes the outcomes of the two approaches to UR is not dislocation or lack thereof. Instead, our results substantiate the argument in the displacement literature that it is the spatial-social restructuring of the neighborhood, rather than physical relocation, that contributes to residents’ sense of “lost home.” We found that improvements to housing conditions and the built environment of the overall neighborhood were conducive to enhanced NA. We also found that CSC was the strongest predictor of post-renewal change in NA among the neighborhood-change variables we analyzed. It could be argued that micro-renewal achieves better community outcomes primarily because it preserves existing CSC, whereas redevelopment tends to change the original social milieu because of an influx of new residents or resettlement. Our interviews show that although residents in both micro-renewal and redevelopment neighborhoods were satisfied with BE improvement, residents in redevelopment neighborhoods were more likely to feel the effects of changing demographics and social relations, leading to a weakened sense of belonging post-renewal. The perceived neighborhood restructuring is also conditioned on individuals’ pre-renewal residential satisfaction and post-renewal economic prospects. Residents who were more satisfied with their pre-renewal neighborhood were less likely to perceive a positive change in NA, in contrast to the ambivalent effects of post-renewal economic prospects.

While some studies point to the positive effects of compensation in mitigating adverse community outcomes, our results show that residents who received in-kind compensation were more likely than those who received cash compensation to experience improved NA because the former improved their housing conditions and provided them with new income sources. However, both groups were equally vulnerable to the erosion of CSC. In other words, the material benefits of compensation can only offset the social costs of losing a home to the extent that they improve residents’ long-term financial situations and access to decent neighborhoods and housing. These compensation effects were primarily found in the redevelopment context because most residents in micro-renewal neighborhoods did not receive any compensation.

Notably, the specifics of the redevelopment processes we studied, i.e. the availability of generous in-kind compensation and in-situ resettlement for eligible owner households, may be unique to China in that these were enabled by China’s dual urban-rural land system, its political will to pursue the dual goals of economic growth and social stability, as well as a strong embedded state power in the redevelopment process (Zhu et al., Citation2022).

This study reveals a complex picture of post-renewal residential experiences, rather than simple and linear relationships between redevelopment and displacement (whether physical or symbolic), as the gentrification literature depicts. Echoing Kleinhans and Kearns (Citation2013) and Li et al. (Citation2019), we find that UR, including when it involves redevelopment and resettlement, does not result in a loss of community for everyone. The heterogeneous post-renewal experiences we observed were directly impacted by perceived changes in residents’ immediate environments, which were further contingent on their pre-renewal residential experiences, long-term economic prospects, and access to support (e.g. compensation) during UR. This study also corroborates findings in the displacement literature that CSC plays a significant role in preserving residents’ SoP and in turn, that the absence of it increases creating symbolic displacement. In this regard, wholesale redevelopment entails much higher socio-psychological costs than micro-renewal. Further, our case studies did not include any migrant workers who were forced to relocate out of their neighborhoods without compensation. This means that the social costs of redevelopment projects can be much higher than those captured in this study.

Despite the relative success of micro-renewal projects in preserving the community, residents in micro-renewal neighborhoods have shared concerns about weak community participation in the renewal process and potential negative long-term outcomes of this approach to urban renewal. For example, the effects of BE upgrades may be dependent on continued government support, which is not guaranteed. Also, long-term gentrification may occur as these neighborhoods become more attractive to businesses and high-income populations, which warrants future studies.

We acknowledge this study’s limitations. Our study only covers eight neighborhoods. Although we considered various key attributes of interest when selecting these cases, our findings still may not apply to the whole city of Guangzhou. Our case study respondents were primarily stay-put residents who tended to be homeowners and local hukou holders. Migrants and renters may be under-represented, as they were less likely to stay in their neighborhoods after renewal. Particularly in redeveloped neighborhoods, many migrants and renters could have been displaced, making it challenging to keep track of this group. Hence, our case studies’ findings do not speak to the experiences of displaced residents who may have experienced more significant disruptions to their community life. Nonetheless, our study sheds light on nuanced relationships between UR and post-renewal community sentiment. Particularly, we show that the high socio-psychological costs of neighborhood restructuring resulting from wholesale redevelopment can only be partially mitigated by exceptionally generous compensation schemes that are limited to certain groups and contingent on local contexts. In this regard, urban renewal through redevelopment is less cost-effective than the micro-renewal approach. Achieving the dual goals of neighborhood revitalization and community preservation requires that UR projects strike a balance between the needs and interests of different community groups while mitigating disruption in the material, economic, social, and psychological aspects of community life.

Acknowledgment

We thank all survey and interview participants in this research who shared their lived experiences and stories with us. We appreciated the assistance from many college students in China who helped to administer the survey and conduct the fieldwork during the pandemic. We also thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments. Yushu Zhu contributes to conceptualization, methodology, first draft writing and manuscript revision, data analysis, and funding acquisition; Changdong Ye contributes to data collection, data analysis, manuscript revision, and funding acquisition. Yushu Zhu and Changdong Ye assert joint first authorship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Redevelopment of industrial land or brownfields is beyond this study’s scope.

2 See report by Sohu News on May 12, 2017: https://www.sohu.com/a/140168019_582024.

3 The data collection procedures received ethics approval from Simon Fraser University ethics office (No. 20200143).

4 These are neighborhood-based urban governance entities under the purview of city district governments.

5 Students trained to conduct the survey were asked to visit different communal spaces within the neighborhood at different points during the day and throughout the week to cover both weekdays and weekends. At each spot, every 10th person was invited to participate. If a person was deemed ineligible, the next person was drawn as a replacement.

6 Acceptable values of alpha range from 0.70 to 0.95.

7 Acceptable model fit is indicated by a CFI value of 0.90 or greater (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

References

- Atkinson, R. (2015). Losing one’s place: Narratives of neighbourhood change, market injustice and symbolic displacement. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(4), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2015.1053980

- Bowen, N. K., & Guo, S. (2011). Structural equation modeling. Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, M. (2008). Spoiled mixture: Where does state-led `Positive' gentrification end? Urban Studies, 45(12), 2385–2405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008097105

- Day, J., & Cervero, R. (2010). Effects of residential relocation on household and commuting expenditures in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(4), 762–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00916.x

- Doshi, S. (2013). The politics of the evicted: Redevelopment, subjectivity, and difference in Mumbai’s slum frontier. Antipode, 45(4), 844–865. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01023.x

- Dossa, P., & Golubovic, J. (2019). Reimagining home in the wake of displacement. Studies in Social Justice, 13(1), 17.

- Du, T., Zeng, N., Huang, Y., & Vejre, H. (2020). Relationship between the dynamics of social capital and the dynamics of residential satisfaction under the impact of urban renewal. Cities, 107, 102933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102933

- Elliott-Cooper, A., Hubbard, P., & Lees, L. (2020). Moving beyond Marcuse: Gentrification, displacement and the violence of un-homing. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519830511

- Fang, Y. (2006). Residential satisfaction, moving intention and moving behaviours: A study of redeveloped neighbourhoods in inner-city Beijing. Housing Studies, 21(5), 671–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030600807217

- Freeman, L., & Braconi, F. (2004). Gentrification and displacement New York City in the 1990s. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976337

- Fried, M. (1968). Grieving for a lost home: Psychological costs of relocation. In J. Wilson (Ed.), Urban renewal: The record and the controversy (pp. 359–378). The M.I.T Press.

- Fu, Q. (2015). When fiscal recentralisation meets urban reforms: Prefectural land finance and its association with access to housing in urban China. Urban Studies, 52(10), 1791–1809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014552760

- GCCCPC. (2020). Guiding Opinions on Implementing and Reinforcing Urban Renewal and Promoting High-Quality Development (in Chinese). Guangzhou City Committee of Communist Party of China (GCCCPC) [2020. No.10].

- Guangdong Provincial Government. (2021). Guangdong provincial government on fully promoting and implementing old neighborhood renovations. Guangdong Provincial Government [2021. No. 03].

- Guangzhou Municipal Government. (2015). Rules and guides for urban renewal in Guangzhou (in Chinese). Guangzhou Municipal Government [No. 134].

- Guangzhou Municipal Government. (2021). The implementation plan of Guangzhou old neighborhood renovations (in Chinese). Guangzhou Municipal Government.

- GZURB. (2016). On cost accounting methods for redevelopment of old villages in Guangzhou (in Chinese). Guangzhou Urban Renewal Bureau (GZURB).

- GZURB & GZPDI. (2015a). Guangzhou urban renewal master plan 2015–2020 (in Chinese). Guangzhou Urban Renewal Bureau (GZURB), Guangzhou City Planning and Design Institute (GZPDI).

- GZURB & GZPDI. (2015b). Guangzhou thirteenth five-year plan of urban renewal, 2015–2020 (in Chinese). Guangzhou Urban Renewal Bureau (GZURB), Guangzhou City Planning and Design Institute (GZPDI).

- Han, H., Shu, X., & Ye, X. (2018). Conflicts and regional culture: The general features and cultural background of illegitimate housing demolition in China. Habitat International, 75, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.04.008

- Harvey, D. (2003). The new imperialism. Oxford . Oxford University Press.

- Hazelzet, A., & Wissink, B. (2012). Neighborhoods, social networks, and trust in post-reform China: The case of Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 33(2), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.2.204

- He, S. (2012). Two waves of gentrification and emerging rights issues in Guangzhou, China. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(12), 2817–2833. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44254

- Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernández, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0221

- Hipp, L., Bünning, M., Munnes, S., & Sauermann, A. (2020). Problems and pitfalls of retrospective survey questions in COVID-19 studies. Survey Research Methods, 14(2), 109–1145.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Kearns, A., & Mason, P. (2013). Defining and measuring displacement: Is relocation from restructured neighbourhoods always unwelcome and disruptive? Housing Studies, 28(2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.767885

- Kleinhans, R., & Kearns, A. (2013). Neighbourhood restructuring and residential relocation: Towards a balanced perspective on relocation processes and outcomes. Housing Studies, 28(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.768001

- Kleinhans, R., & Van der Laan Bouma-Doff, W. (2008). On priority and progress: Forced residential relocation and housing chances in Haaglanden, the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 23(4), 565–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030802101641

- Li, L. H., Lin, J., Li, X., & Wu, F. (2014). Redevelopment of urban village in China – A step towards an effective urban policy? A case study of Liede village in Guangzhou. Habitat International, 43, 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.03.009

- Li, S.-M., & Song, Y.-L. (2009). Redevelopment, displacement, housing conditions, and residential satisfaction: A study of Shanghai. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(5), 1090–1108. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4168

- Li, X., van Ham, M., & Kleinhans, R. (2019). Understanding the experiences of relocatees during forced relocation in Chinese urban restructuring. Housing, Theory and Society, 36(3), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1510432

- Liu, Y., Wu, F., Liu, Y., & Li, Z. (2017). Changing neighbourhood cohesion under the impact of urban redevelopment: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geography, 38(2), 266–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1152842

- Manzo, L. C., Kleit, R. G., & Couch, D. (2008). ““Moving three times is like having your house on fire once”: The experience of place and impending displacement among public housing residents. Urban Studies, 45(9), 1855–1878. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008093381

- Marcuse, P. (1985). Gentrification, abandonment, and displacement: Connections, causes, and policy responses in New York City. Washington University Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law, 28, 195–240.

- MHURD (China Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development). (2022). 2021 Nation-wide new renovation projects of old dilapidated urban neighborhoods (in Chinese). http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-01/25/content_5670300.htm.

- Porteous, J. D., & Smith, S. E. (2001). Domicide: The global destruction of home. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Shaw, K. S., & Hagemans, I. W. (2015). ‘‘Gentrification without displacement' and the consequent loss of place: The effects of class transition on low-income residents of secure housing in gentrifying areas. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(2), 323–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12164

- Shin, H. B. (2016). Economic transition and speculative urbanisation in China: Gentrification versus dispossession. Urban Studies, 53(3), 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015597111

- Slater, T. (2013). Expulsions from public housing: The hidden context of concentrated affluence. Cities, 35, 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.10.009

- State Council of PRC. (2001). The regulation on the management of the demolition of urban dwellings (in Chinese)

- State Council of PRC. (2011). Regulations on the expropriation of houses on state-owned land and compensation (in Chinese). State Council of PRC [No. 590].

- State Council of PRC. (2020). The state council guiding opinions on fully promoting old neighborhoods renovations (in Chinese). State Council of PRC [2020. No.23].

- Stedman, R. C. (2003). Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society & Natural Resources, 16(8), 671–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920309189

- Varady, D., & Kleinhans, R. (2013). Relocation counselling and supportive services as tools to prevent negative spillover effects: A review. Housing Studies, 28(2), 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.767882

- Wang, Y., & Kemeny, T. (2022). Are mixed neighborhoods more socially cohesive? Evidence from Nanjing, China. Urban Geography, https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.2021714

- Wang, Z., & Wu, F. (2019). In-situ marginalisation: Social impact of Chinese mega-projects. Antipode, 51(5), 1640–1663. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12560

- Wu, F. (2016). State dominance in urban redevelopment. Urban Affairs Review, 52(5), 631–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087415612930

- Ye, L., Peng, X., Aniche, L. Q., Scholten, P. H. T., & Ensenado, E. M. (2021). Urban renewal as policy innovation in China: From growth stimulation to sustainable development. Public Administration and Development, 41(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1903

- Zhang, Y. (2018). Domicide, social suffering and symbolic violence in contemporary Shanghai, China. Urban Geography, 39(2), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1298978

- Zhao, W., Li, Z., & Li, Y. (2021). A review of researches on urban renewal in contemporary China and the future prospect: Integrated perspectives of institutional capacity and property rights challenges (in Chinese). Urban Planning Forum (in Chinese), 265.

- Zhu, Y. (2014). Spatiality of China’s market-oriented urbanism: The unequal right of rural migrants to city space. Territory, Politics, Governance, 2(2), 194–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2014.911700

- Zhu, Y. (2015). Toward community engagement: Can the built environment help? Grassroots participation and communal space in Chinese urban communities. Habitat International, 46, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.10.013

- Zhu, Y., Breitung, W., & Li, S. (2012). The changing meaning of neighbourhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Studies, 49(11), 2439–2457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011427188