ABSTRACT

As urban governments adopt smart city strategies for delivering services, the need to understand how – and in whose interests – these strategies are formed is imperative. The selection of smart city verticals (or areas of focus for smart city programs) within processes of urban governance has implications for which aspects of the urban agenda become prioritized. Through a study of seven UK smart cities, the paper investigates the framing of city problems, selection of smart verticals, and decision-making logics. The findings highlight that the selection of smart city verticals within the case study cities is rooted in four key considerations: challenges in service delivery, pragmatism, entrepreneurialism, and broader national and global events and policy agendas. These considerations transcend different spatial scales and governance arrangements, raising questions around democratic accountability and transparency. The study concludes that caution is warranted when framing smart cities as a solution to city problems.

Introduction

The aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and austerity policies pursued by many national governments have left many local governments in a weakened fiscal position amidst growing demand for municipal services (Cardullo et al., Citation2019). Hence, in a search for cost-effective and efficient means of service delivery – combined with a drive to appear innovative in order to attract investment – many city leaders have turned to smart cities, often framing them as solution to pressing urban problems (Cook & Valdez, Citation2021; Karvonen et al., Citation2019). While smart cities have grown in popularity over the past two decades, the verticals (or areas of focus) in which smart city initiatives sit and how they are selected remains an under researched issue.

While we return to these verticals and explain some of the common areas of focus for smart city initiatives in the literature review, we maintain that interrogating how smart city verticals emerge in the first instance is important for at least two crucial reasons. First, Hollands (Citation2015) reminds us that “the smart city is made of a diverse range of things and can inadvertently bring together different aspects of urban life that do not necessarily belong together, hiding some things and bringing others to the ideological fore” (p. 64). This implies that smart cities can downplay or overlook some urban problems while privileging others. This has important implications for shaping circulations of power within a city, and for shaping the governance network itself, as Söderström et al. (Citation2014) summarizing Callon (Citation1940) observe that a “crucial step in the creation of socio-technical networks is the problematization of a situation in order to become indispensable actors in a network of solutions” (p. 309). Which issues become prioritized – and in whose interests – and which become overlooked has clear implications for who benefits from the smart city, and for how urban inequalities are tackled or entrenched.

Second, in most urban areas, the provision and management of some urban infrastructures and city services fall within the purview of multiple tiers of local government (Karvonen et al., Citation2019), as is the case in the United Kingdom where waste management falls within the remit of county councils, and city or district councils are responsible for rubbish collection (GOV.UK, Citationn.d.). This means that depending on the area of focus chosen, the selection of verticals could have profound implications for urban governance, in terms of the locus of decision-making and modes of demanding transparency and accountability.

By following this line of inquiry through interviews with individuals involved in smart city governance across seven UK cities (Oxford, Milton Keynes, Nottingham, Leeds, Newcastle upon Tyne, Bristol and Birmingham), we seek to shift the ongoing discussions about smart cities to the decision-making process involved in the selection of their verticals. This is important, as unpacking the roots of vertical selection in local governance networks can help to illuminate why smart city initiatives might or might not be able to address the city problems which are often used as a justification for their relevance. The paper also highlights that the selection of smart city verticals as an aspect of smart city governance is not distinct from the politics and complexities that characterize well-established aspects of urban governance at the local level.

To this end, the paper is organized as follows. In section “Literature review”, we review the literature on smart cities, considering their driving forces, common smart city verticals and some of the initiatives which fall within each category. We ground the selection of verticals in a discussion of urban governance. In section “Methodology”, we outline the research strategy, setting out the justification for the case studies chosen for the research and the methodology and approach to analysis. We present our research findings in section “Findings” and discuss their implications and conclude in section “Discussion and Conclusion”.

Literature review

Smart cities: definitions and discourses

Since the 1990s, smart cities have been understood to encompass “technology-based innovation in the planning, development and operational management of cities” (Tan & Taeihagh, Citation2020, p. 146). However, there is a lack of consensus around precisely how a smart city should be defined. Vanolo (Citation2014, p. 884) observes that the smart city “is an evocative slogan lacking a well-defined conceptual core,” thus allowing different “communities of interests” (including funders, academics, consultants, policymakers) (see Pascavela et al., Citation2015) and a “well-organised epistemic community” (see Cardullo et al., Citation2019) “to use the term in ways that support their agenda” (Vanolo, Citation2014, p. 884).

Meanwhile, Kitchin (Citation2016) suggests that smart cities can be understood from three main perspectives. The first is about how the digital instrumentation of cities can influence the configuration and management of urban infrastructures. The second perspective views smart cities as those which deploy initiatives aimed at strengthening policy-making, and urban governance through the use of information technologies. The third perspective sees the smart city as the application of digital technologies and ICT to advocate a citizen-oriented approach to urban development and management which places emphasis on accountability, innovation, social justice, and transparency (Kitchin, Citation2016).

Critical commentators draw attention to how the city is conceived or framed at both ideological and normative levels (Green, Citation2019), the types of publics conceived (Joss et al., Citation2019), the form of governance enacted (Cardullo & Kitchin, Citation2019; Leleux & Webster, Citation2018), the nature of citizen participation (Shelton et al., Citation2015) and the ethical issues underpinning their governance (Ehwi et al., Citation2022). For example, Cardullo et al. (Citation2019) observe that the smart city frames the city as a system rather than a place and it takes a technological solutionist approach to problem solving.

Commenting on the role of discourses in 5,553 smart cities globally, Joss et al. (Citation2019) suggest that they “shape concepts and programs and constitute key avenues through which ideas and practices are borrowed, transmitted, and reproduced within different geographical, cultural and institutional settings” (pp. 4–5) as they purposefully recast cities from places with histories and lived experiences to ephemeral notions of projects, hubs, laboratories, platforms and urban experiments. Cook and Valdez (Citation2022) also argued that “as smart technologies are embedded in the urban fabric, technical standards become de facto law and technical expertise acquires unintended political powers” (p. 3). Similarly, Söderström et al. (Citation2014) observed that smart cities create “new relations between technology and society” as the latter becomes increasingly dependent on the former for solutions. As part of this process, “discourse around smart cities become a tool to make certain actors and technologies ‘obligatory passage points’ or key actors in the development and implementation of specific forms of urban management solutions” (p. 309).

Smart city verticals

Verticals – or areas of focus – can be thought of as the lens through which city problems are seen and the specific aspect of cities that smart city solutions engage with. Hämäläinen (Citation2020) adds that emphasizing verticals such as transportation or energy influences the type of technologies and standards that are chosen to support the needs and requirements of a particular market or industry. Although “verticals” are a familiar concept in the business and management literature (see Harrrigan, Citation1984), the smart city literature has appropriated it as a shorthand for conceiving the city, allowing city managers to engage with the markets in terms of buying into new partnerships, expertise, funding arrangements, infrastructure and standards (c.f. Angelidou, Citation2015).

Smart city verticals emerge from an instrumental perspective of the city and its problems. Among instrumentalists, comprising but not limited to academic institutions (e.g. universities and research centers), industry (e.g. technology and finance) and governments (at national, regional and city levels) (see Mattern, Citation2019) a central argument is that a city comprises its physical and social infrastructure through which it produces the public sphere (Joss et al., Citation2019), and therefore the embedding of technological devices within existing urban infrastructure, and the subsequent impacts on different aspects of social life, warrant attention in understandings of smart cities (Batty, Citation2012; Joss et al., Citation2019). From this orientation, the city is problematized in a way whereby urban questions are turned into “engineering problems” which can be measured, analysed and solved using quantitative methods. This instrumental view is also supported by a narrative for a radical transformation of how cities are managed following the “big data revolution” and the disruptions caused by breakthroughs in new technologies (Joss et al., Citation2019).

The material manifestation of this perspective is often seen in the application of digital technologies to existing city infrastructures to solve pressing urban problems (Kitchin, Citation2016; Söderström et al., Citation2014). Against this backdrop, several studies have attempted to categorize the areas of focus for different smart city initiatives. For instance, Kitchin (Citation2016) suggests the technologies deployed in smart cities fall under eight domains (or verticals), comprising: (1) Government (e.g. online transactions and city operating systems); (2) Security and emergency services (e.g. centralized control rooms); (3) Transport (e.g. intelligent transport systems), (4) Energy (e.g. smart grids); (5) Waste (e.g. compactor bins), (6) Environment (e.g. sensor networks for capturing data on pollution); (7) Buildings (e.g. Building management systems), and (8) Homes (e.g. smart meters).

For the Future Cities Catapult (Citation2016) six verticals characterize smart city demonstrators. They include: (1) city services (e.g. traffic and waste management demonstrators), (2) smart utilities (e.g. smart meter and smart grid demonstrators), (3) smart healthcare (e.g. assisted living demonstrators), (4) connected and autonomous vehicles (e.g. driver assistance demonstrators), (5) Last-mile supply chain and logistics (e.g. fleet management and drone delivery demonstrators) and (6) connectivity and data (e.g. IoT, LoRaWAN and 5G test networks). Meanwhile, Giffinger et al. (Citation2007) suggest that smart cities comprise six characteristics and a myriad of factors, summarized as: (1) smart economy (e.g. entrepreneurship and economic image), (2) smart governance (e.g. transparent governance), (3) smart environment (e.g. natural resource use), (4) smart people (e.g. affinity for life-long learning), (5) smart mobility (e.g. sustainability and safe transport) and (6) smart living (e.g. social cohesion and housing quality).

As such, it is evident that the categories of smart city verticals identified vary and sometimes overlap. However, there is a need to consider how these domains come to be and the governance and decision-making processes underpinning their selection. We therefore draw upon theoretical insights from the urban governance literature to interrogate decisions made regarding the choice of smart city verticals.

Smart cities and urban governance

In seeking to examine how areas of focus for smart initiatives emerge, it is pertinent to consider as a key line of inquiry how urban governance operates in the process of vertical selection. Processes of framing, in which particular options are constructed as more desirable than others, are essential to understanding how verticals are chosen for smart city development. As Callon et al. (Citation2009) highlight, while technical issues – such as the disposal of nuclear waste, or in our case, the selection of smart city initiatives to address urban problems – are often framed by apparently scientific actors as having an obvious or necessary technical solution, recognition of a multitude of actors highlights that there exists considerable debate on socio-technical issues, and decision-making on such issues is inherently political. Indeed, Farías and Blok (Citation2016) argue that urban power is increasingly to be located within technical infrastructure systems, including data platforms, and that “government has become a techno-political art entailing the design, configuration, maintenance and repair of the infrastructures we live by” (p. 540). The processes by which verticals for smart city development are chosen are therefore revealing of the ways in which urban power operates, and of the crucial moments of decision-making which shape outcomes for urban space.

Several trends in urban governance (in particular, neoliberal urban governance) are of relevance in the debates around smart city management. Smart cities themselves have arisen in the context of a protracted period of austerity and continually diminishing local authority budgets in the United Kingdom, overseen by successive coalition and Conservative governments, which have led many local authorities to seek efficiency-enhancing measures (Hastings et al., Citation2015).

This is a widespread trend, spanning several countries and numerous urban municipalities. In a study of Italian smart cities, Pollio (Citation2016) highlights that while smart city technologies have often hidden urban policy decisions under a veil of technical solutions to addressing urban problems and managing austerity-induced budget cuts, they are far from apolitical. Indeed, smart initiatives represent a political tool aiming to deliver on values of efficiency, and to replace funding-intensive urban projects (which are often impossible within constrained local authority budgets) with a series of short-term experiments in addressing urban challenges, which risks overlooking the long-term structural issues which underlie such challenges (Cowley & Caprotti, Citation2019).

Importantly, the emergence of smart urbanism has been identified as a key development in neoliberal urban governance: Grossi and Pianezzi (Citation2017) argue that the geographical imaginary of the “utopia” represented by much of the rhetoric surrounding the notion of smart cities strongly reflects a neoliberal agenda. They highlight that the increased reliance of local authorities on private sources of funding, and on service-delivery mechanisms which involve public-private partnerships – all of which are part and parcel of many of the smart cities hailed as being for the public good – are characteristic of the neoliberal tendency to exalt inter-urban competition and market-led approaches to dealing with urban problems. Yet while smart cities may be relatively new vehicles of urban neoliberalism, many of the techniques and strategies of urban governance entailed have been well established for several decades.

Entrepreneurialism as a governance approach has long been recognized as part of urban neoliberalism. In the 1980s, Harvey (Citation1989) identified a shift in focus of local urban governance (including not only formal organizations of local government but also a host of other actors) from providing services, to attracting private investment to stimulate local economic growth. Indeed, Harvey (Citation1989) noted that this is a phenomenon which is rooted in transformations in capitalist development which have seen widespread deindustrialization in advanced economies, alongside heightened structural inequalities, and that the subsequent shift towards an entrepreneurial mode of urban governance represents an effort to engage in inter-urban competition for resources in what is framed as a zero-sum game where those cities that fail to effectively compete for capital lose out to more entrepreneurial cities.

Jessop and Sum (Citation2000) define entrepreneurial cities as those which develop and deliver strategies intended to ensure that they remain economically competitive (or become increasingly so). Critically, entrepreneurial cities explicitly project themselves as being entrepreneurial, and include “entrepreneurialism” as part of the narration of their identity (Jessop & Sum, Citation2000). It is easy, therefore, to see how smart cities can in many instances be understood to be entrepreneurial, given that they are often portrayed as centers of innovation, and may be viewed as a key means of attracting investment as a result (see Cardullo et al., Citation2018).

Nonetheless, the entrepreneurial smart city represents a departure of sorts from earlier iterations of entrepreneurial urbanism: McGuirk et al. (Citation2021) argue that smart cities have seen a shift away from the enabling role traditionally played by the entrepreneurial local state, which occurs as organizations of local governance react to the perceived need to prioritize economic growth. They highlight that alongside the characteristic enabling of private investment (often entailing local state absorption of risk) and speculation, entrepreneurial governance in smart cities adds experimental practices (which come with inherent risk) to the mix, and works to actively constitute smart cities through these practices. And while this entrepreneurial governance in smart cities is often aimed at growing a network of knowledge-economy start-ups (see Rossi, Citation2016), and fostering competitiveness on an interurban scale, McGuirk et al. (Citation2021) argue that these are not the only arenas in which “active, constitutive and experimental practices” (p. 1744) play out, with other aspects of urban governance, focused on non-economic facets of city life and the day-to-day running of services, also undergoing changes as a result of these practices.

Studying smart cities therefore offers an opportunity to examine nuances within trends in urban governance (see Rossi, Citation2016). Peck et al. (Citation2013) argue that while neoliberalism is a hegemonic ideology, it is not fixed, and continually evolves in localized settings, where specific local historical contexts shape the conditions of its manifestation. Cities – and indeed, smart cities – are not simply imposed upon by the processes associated with neoliberalism, but are key sites for its continual reiteration (Peck et al., Citation2013). As such, the remainder of this paper seeks to interrogate the specific ways in which neoliberal urban governance occurs across a number of UK cities implementing smart initiatives, and to show how these governance processes shape the landscape of smart initiatives which emerges within and across these settings.

As this paper considers how city problems are framed and verticals (or areas of focus) chosen for smart initiatives within cities, it is worth considering here who makes these choices and how. Decision-making within smart cities has an ethical dimension, whether or not this is explicitly recognized by those making decisions (Ehwi et al., Citation2022). Decisions are often made with reference to a system of norms and values, both personal and organizational, which shape the ethical reasoning carried out by decision-makers (see Hunt & Vitell, Citation2006). As such, the norms and values which filter through an organization are critical in shaping decisions, and given that neoliberal ideology remains hegemonic in urban governance (even if there are local differences in its manifestation), it is possible to trace the ways in which neoliberal values underpin choices in smart city governance. The remainder of this paper considers in depth how specific verticals become the focus of smart city initiatives in cities across the United Kingdom, and considers what the processes of vertical selection can reveal about urban governance.

Methodology

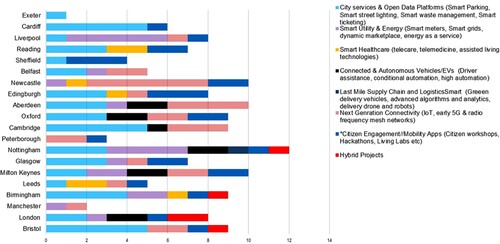

To interrogate how smart city verticals become selected through processes of decision-making in urban governance, the United Kingdom was chosen as the national context for this research. This is partly because the United Kingdom government (via the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills) has funded several smart city initiatives to position the United Kingdom as a leading exporter of smart city consultancy and services (Cardullo et al., Citation2019). Additionally, UK cities such as London, Manchester and Newcastle have featured in both global and European Smart City rankings (Manville et al., Citation2012). Thus, the United Kingdom provides an appropriate context to draw relevant insights about smart city development generally. However, there is a practical challenge, in that there is no official list of UK smart cities and their respective initiatives. So, we began our inquiry by reviewing existing reports that have documented smart city initiatives across the United Kingdom, and found the report on smart city demonstrators by Farías & Blok, Citation2016, to be among the most comprehensive in terms of breadth. Next, we created a database of the demonstrator projects captured in the Future Cities Catapult report to create a chart of different smart city project demonstrators and the verticals they sit in (see ).

Figure 1. Number of different Smart City Demonstrators in UK Cities. Source: Compiled from the Future Cities Catapult's Smart City Demonstrators: A Global Review Report (2016).

Following from , we shortlisted cities that have implemented multiple verticals (at least four verticals), to allow us to engage with questions regarding the selection of the different verticals and their governance. As the catapult report was slightly dated, we visited the websites linked to the smart city demonstrator projects, including websites of their respective city councils to ascertain the status of the reported demonstrator projects. We decided to focus on cities which had smart projects that were still ongoing or had been scaled up.

Local authority officials from seven cities comprising Oxford, Milton Keynes, Nottingham, Leeds, Newcastle, Bristol, and Birmingham agreed to participate in the study. Semi-structured interviews were held with a total of 16 participants comprising 10 council officers managing ongoing smart city initiatives in the respective councils, four elected politicians who sit on committees with remits on economic development and urban regeneration, a technology consultant and an academic working closely with councils on smart city projects.

The interviews took place between June and September 2021 and were organized via Microsoft Teams video calls. The interviews explored questions regarding the problems interview participants believed their cities were facing, the decision-making process regarding the choice of city problems to focus smart initiatives on, the governance and management of smart city verticals and the challenges that come with them, and the ethical considerations regarding the choice of smart city verticals. The interviews were recorded with permission from the participants and later transcribed.

In terms of analysis, the approach to thematic analysis suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2012) was adopted. Both authors independently examined interview transcripts to become “intimately familiar with the data sets” (p. 61). Next, initial codes were generated from the extracts at both descriptive and semantic levels. The authors independently developed themes around identification and framing of city problems, and the factors influencing the selection of smart city verticals and a meeting was later held to compare and refine common themes and also reconcile divergent themes based on criteria such as the depth of the theme, its coherence and evidence base. This peer-review process of data analysis has been found to counteract “sole-author biases” whilst improving the robustness and confidence in the empirical findings reported (see Adzimah-Alade et al., Citation2020). The authors then named the themes by paying attention to how they come together to elucidate how smart city areas of focus or verticals emerge. The final stage entailed combining descriptions, arguments and inferences to answer the research questions whilst embedding the analysis in the existing literature on smart city governance.

Findings

The case study cities

The cities we studied differed in important respects, including their population, UK region, local governance arrangements, and gross weekly pay (See ). These differences have a bearing on the types of problems cities face and the smart city initiatives deployed. However, there are also common features among the cities. For example, cities with larger populations (above half a million people) namely, Birmingham, Leeds and Newcastle are found within metropolitan areas. Similarly, cities in Southern England, namely, Oxford, Milton Keynes and Bristol have higher gross weekly pay (above £650) than their counterparts in the Midlands and Northern England. These similarities suggest that some problems might be common across different cities.

Table 1. Brief information about the selected case study cities.

City problems and their framing

The list of problems cities face is potentially inexhaustive. However, what city stakeholders choose to focus on in their communication is important because it can provide impetus for selecting particular smart city initiatives as well as justification for the decisions made. For the case study cities, interview participants mentioned some city problems much more frequently than others. For example, transportation-related problems (comprising traffic congestion, high carbon emission, ageing transport infrastructure, single person car use, etc.) and poverty-related problems (including incidence of deprivation, social inequalities, child and adult poverty, and street begging, etc.) were among the most frequently cited issues. These were followed by housing-related problems (including unaffordability, homelessness, fuel poverty, and energy inefficient buildings). Other issues highlighted included healthcare and connectivity-related challenges.

Besides the identification, how stakeholders framed and talked about the problems facing their cities were instructive. While some problems were framed as “actually existing” (Brenner & Theodore, Citation2002) or “existent problems” (Dillon, Citation1982), others were framed as “potential” problems (Dillon, Citation1982). These two approaches to framing city problems are significant because with the former, interviewees reasoned that such problems affect or are experienced by the general public on daily basis. Hence, such problems are not difficult to prioritize in terms of gaining public support and investment.

Transport is the top problem … it always comes up. – Council officer (illustration of an “actually existing” problem)

The original plan was [for] a city for 200,000 people, we're now at 280,000, there are plans to grow it to between 450,000 and 500,000 if you include the Greater Milton Keynes area … So, what the Smart Cities stuff is trying to do is effectively get ahead of the curve on some of these challenges, not necessarily the challenges today, but trying to plain and smooth the challenges before it becomes gridlock. And that has drawbacks because, when you're doing things, when people aren't [yet] sitting in a traffic jam for 25 min, the case for change is much more difficult. – Council officer (illustration of a “potential problem”)

So I suppose what I'm going to say I think are the city's priorities, and I won't choose highways, but if you probably spoke to somebody in [the department for] highways, they would say “ours is much more important than the other stuff because without highways or without transport planning, you wouldn't be able to do [x, y or z]”. – Council officer.

Ongoing smart verticals

It is worth briefly discussing here the smart city initiatives happening across the case study cities, and some of the verticals in which they fall. Several smart initiatives are focused on transportation, including e-scooter trials, starship delivery robots, electric bus fleets, and EV charging ports, etc. Next generation connectivity, comprising projects such as the installation of wireless networks in public buildings, and initiatives aimed at addressing digital exclusion, is the second most common vertical across the case study cities. Other verticals included those focused on energy, assistive living, and governance.

Our analysis suggests that, although the prominence of the smart mobility vertical matches with the popularity of transportation-related problems, this is not the case for all verticals. This does not only point to a misalignment between city problems identified and the smart city initiatives deployed, but goes to show how technical solutions cannot be used for some city problems as the quote below illustrates:

… inequalities are not caused by a lack of technology. They're caused by a whole heap of things further upstream. [For instance], racial disparities … will probably not be solved by technology, you could only mitigate it, but it's not solving an issue – Council officer

If you're going to try and solve a problem … you've got to simplify it … with the complexity in mind. And I think also if you're going to develop an innovation, you have to think of the niche. You're not going to solve every problem – Interview participant.

Factors underpinning the selection of smart city verticals

The study found that four broad considerations, including challenges with the delivery of city services, pragmatism, entrepreneurialism, and existing global and national imperatives underpin the selection of smart city verticals. Note that there are some overlaps in the factors identified, and we do not claim that these are the only drivers of vertical selection. Instead, the four factors which emerged from the research findings provide a useful tool for analysing the different ways in which smart initiatives emerge, and for demonstrating the variable ways in which smart city governance operates to produce different smart city agendas in different cities.

Vertical selection based on existing city services

Interview participants suggested that smart city verticals often emerge as a result of challenges identified within the delivery of existing city services. For example, in Newcastle, some residents reportedly expressed dissatisfaction with waste collection services. The council invested in smart bins which helped improve waste collection by ensuring that bins that were full were prioritized during the collection process, eliminating instances of missed bin collections and reducing the need for refuse vehicles to routinely service areas where waste bins are nearly empty. Similarly in Leeds, challenges existed around delivering health care services, as patients’ health records were not harmonized. The council thus made health care a key part of its smart city vertical by leveraging its existing close working collaboration with the National Health Service (NHS) Trust in the city and data hub to ensure that there is responsible data sharing among recognized healthcare providers. Reflecting on the strides the city has been making in smart health, a councillor from Leeds City Council observed that their smart health vertical enables improved data-sharing:

[It] allows you to get access to your health records now so that these are more transportable and transferable. So that if you go to a different health setting, it's a lot easier for your data to be available to someone who's making a decision, whereas in the past … for hospital appointments, [people] had big files in about three or four different departments. And they never ever consolidated these files together. So nobody ever knew whether or not there were any conflicts in [a person’s] health records – Councillor, Leeds

Vertical selection based on pragmatism

City governments often also take a pragmatic approach to vertical selection, choosing initiatives which draw on their existing strengths. This was the case in the selection of verticals in Oxford. Being globally renowned for its higher education offering, as well as several technology start-ups, the city leveraged the strength of its intellectual capital in the beginning of its Smart Oxford Programme. Officials explained that the program started as conversations between university academics, city officials and third sector organizations and resulted in a stock-taking exercise of the range of digital initiatives already happening across the city which could be brought together under the Smart City umbrella. The stock-taking revealed that there were several initiatives happening around mobility, and hence it was pragmatic to feature mobility as a key anchor of the smart city program.

Officials from Nottingham pointed out that city leadership also played an important role in not just the selection of smart city initiatives, but overall smart city strategy:

I think it first of all comes down to who's driving technological revolution within councils and services … I think if you're within the homelessness department, for example, and whilst you're absolutely committed to service improvement, you might not naturally go to that innovation space, certainly around technology as much as another employee. So I think it's historically the types of conversations that happen within those departments, the type of staff, the type of mindset, etc. One of the challenges we have in [the Smart City team] is unlocking that creative thought process across service areas – Council officer, Nottingham

Importantly, in most UK cities pursuing smart agenda, there is often a lack of a well-resourced dedicated smart city team within the local authority, and a lack of a dedicated funding pot to support their smart initiatives. A recent study in the United Kingdom uncovered that just over a quarter of local governments are very confident of the security of their organizations’ digital networks and that only 15 per cent of local governments think that their digital infrastructure allows them to react effectively to change in working processes (Survey iGOV & Virgin Media Business, Citation2019). Also, in the United Kingdom, an estimated 876,000 jobs (representing a 30% reduction) have been lost in local government since June 2010 (GMB Congress, Citation2019, p. 15), resulting in “increased pressure on the remaining workers who are expected to do more with less” (GMB Congress, Citation2019). Owing to this, some leaders of smart programs feel compelled to steer their city’s smart city agenda in directions that pragmatically allow for securing external funding and overcoming skills and labor deficits. The following insights from three council officers leading smart agendas in three different cities are instructive here:

In terms of Smart Cities, we've delivered Smart City projects on a shoestring really. We don't have a Smart Cities team. Essentially, you're looking at him. So, I am [the] Smart Cities [team]. – City A

If there were 10 of me, 10 Smart Cities officers within the city council, then we would look at many different strands, many different opportunities. We can't cover all the different projects that there are. [Our smart city team] literally is just me. A lot of the other local authorities have Smart Cities teams. But I do it on my own – City B

So while we defined the areas where we believe a smart city approach could support [improvements], we were limited in where we could get the funding. So we've done a lot of work in transport because we've been very successful in winning funding in that sector – City C

Vertical selection based on entrepreneurialism

The way in which particular verticals become the focus for urban authorities pursuing a smart city program also has a clear connection to entrepreneurial urbanism. Austerity has imposed cuts on local authorities, and so efforts to reduce spending or increase efficiency of existing services through smart initiatives might well be understood as a pragmatic response. However, there is also evidence of an entrepreneurial tone here, which is understood as necessary amidst the difficulties with managing a restricted budget:

Resourcing [the Smart City programme] is difficult. We haven't got the skills or the number of people to manage lots of programmes. So, we rely on partnership working and bringing in likeminded people – Council Officer

I think the parking [initiative] is sometimes seen as one where there is a very clear business case. And that can help pay for some of the others where perhaps the business case is less clear. – Smart Cities Consultant

Crucially, where exactly smart city governance sits within the local governance structure is of importance when it comes to shaping the intended outcomes of smart initiatives. Indeed, the positioning of a Smart City team within the economic development department of the local authority had a clear impact on the work of the Smart City team in Nottingham:

My role sits in Economic Development. So anything I do, I'm constantly checked and pulled back, and it's like, “have you considered x, y, z local business in this? Please get them involved”. – Council officer, Nottingham

In the work that we've done [on the Smart City programme], we've engaged with our [city’s elected] cabinet members … We know that without their endorsement and their leadership, a lot of this won't happen. So they will be instrumental in that. What role they'll play in the governance is yet to be determined … because what we don't want is [for the smart city to be] seen as a political issue. We want this to be a city issue, where city partners feel that they're not being dictated to by the city council, but they feel part of the family. So there might be some political overview. But I don't think at this stage we're intending to be driven by a political agenda, it'll be driven by a city agenda. – Council Officer, Birmingham

Vertical selection based on global and national imperatives

In addition to local pressures, there is evidence that broader policy imperatives (at global or national level) shape the selection of smart verticals. The ongoing climate crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic were commonly cited by interview participants as influences on the selection of smart initiatives. There was a general consensus that efforts to reduce and mitigate climate change needed to be considered in any smart city vertical because the impacts are not just limited to the environment but could also be seen in other areas such as healthcare and wellbeing, transportation, and the economy. For example, reflecting on how climate change became a key influence on the selection of verticals in the smart city agenda of Leeds, one interview participant observed:

initially, climate wasn't on [our smart agenda] … If you've got a good environment, your health and wellbeing are likely to be improved. The work that you do on transport has an impact on the environment. So, for that reason, we didn't have climate or the environment as a priority area. But once we declared a climate emergency, I'd suggested that we should have climate emergency as one of our priority areas and really highlight that this is a big deal for us in Leeds – Council officer

There was also consensus that the Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in heightened calls for city leaders to embrace digitalization in all aspects of local service delivery. Specifically, it was argued that the pandemic has helped local authorities to appreciate how important it is to invest in smart infrastructure projects that furnish a real-time understanding of the city, in terms of, for example, changes in footfalls to city centers, levels of air pollution along major roads, and opportunities for local authorities to conduct some of their activities remotely. The quote below is illustrative of how the technology being used for one traffic-management initiative in Leeds was also found to be useful for monitoring changes to city center footfall:

So highways are introducing some new technology and as far as they're concerned it’s about traffic management. And yet that solution can help a different part of the Council to better understand how busy the city centre is, and certainly post-COVID, whether we’re getting back to pre-covid levels of people that are going out into the city, and then they can access that data as well – Council officer

I was effectively given a blank canvas as to where to take Smart Cities in Nottingham, and … we’re aiming to be carbon neutral by 2028. So we're the first of the major cities to be the most ambitious in terms of its timescale. So what I was asked to do was to connect the Smart Cities agenda to the carbon-neutral agenda – council officer

Additionally, the United Kingdom government’s decision to consolidate welfare benefit claims into the Universal Credit (UC) system which is accessible through an online portal was cited as influencing vertical selection. To avoid disadvantaging people without digital skills or access to the internet, many local authorities feature digital inclusion as a key vertical in their smart city agendas. The quote below from council officer in another case study city is illustrative of how national government policy directions do not only influence the selection of verticals at the local level but also alter the scope of activities within existing council departments.

This was at a time when the government was rolling out Universal Credit. A lot of our tenants weren't online, didn't have the right skills, and the Universal Credit Scheme was online only because the government was shifting everything to online. So a lot of the people who needed to access Universal Credit couldn't get online and had never been online … This is where the Digital Inclusion team really started to expand – Councillor

Discussion and conclusion

This paper has interrogated problem-framing and vertical selection in smart cities, drawing empirical insights from seven UK cities. It has demonstrated that the urban problems targeted by smart initiatives vary between those which might be considered to constitute pressing existing problems and those which are anticipated as potential future issues. Through the framing of city problems in smart city discourse, potential urban issues which may be currently intangible can be materialized as urgent and imperative issues for both political endorsement and funding.

While this insight concurs with the general observation in the literature regarding the transcendent power of smart city discourses mobilized and often exported from contexts different from where smart city initiatives are eventually deployed (Cook & Valdez, Citation2022; Joss et al., Citation2019; Wiig, Citation2015), our findings focus attention on how within one local context, discourses can be mobilized to prioritize and privilege certain problems over others. This is important given that the privileging of problems to be tackled through smart initiatives requires the use of language, skillsets and ontologies (including beliefs about the city and how people interact with it) that have increasingly become dominated by a handful of tech experts, running the risk of precluding the possibility for citizens to participate in the co-identification of city problems and the co-production of their solutions (Bolz, Citation2018; Goodman et al., Citation2020).

While the interrogation of the framing of city problems within this paper reveals the privileging of some problems over others, it is important to note the inability of technology to solve every problem, as has been acknowledged by interview participants. This invites inquiry into how city problems which do not regularly feature in smart city discourses are given attention by policymakers and how much public or private funding is channeled towards addressing those problems. This is an area which would benefit from further empirical research to deepen our understanding of the relationship between funding allocations for problems that regularly feature in smart city discourse and those that do not.

Our findings suggests that the process of vertical selection is not linear in the sense that smart city verticals are not projected neatly onto the urban problems identified by local authorities. Indeed, while there is evidence that some cities strive to link their smart city verticals to existing local service delivery, thereby suggesting that some existing city challenges do indeed influence vertical selection and the smart city agenda overall, in many cases, verticals have emerged in ways that reflect among other things, financial pressures on local authorities, funding-body priorities, pragmatism, organizational values and norms, and strategic (re)positioning. The variety of ways in which cities choose their smart city verticals indicate that the governance of smart cities is immutable to the deeply political, messy, ambivalent and contested features that have long characterized decision-making within urban governance at local levels of government (Pierre, Citation2012; Rossi, Citation2016; Shelton et al., Citation2015).

Therefore, following Rossi’s (Citation2016) call for a variegated understanding of corporate involvement in smart city development, our study calls for a “variegated” and nuanced understanding of smart city vertical selection. As such, consideration of how smart city verticals emerge raises critical questions regarding the implications for democracy, transparency, accountability and justice which emerge from smart city governance, and how different drivers behind vertical selection interact to produce variable outcomes for urban residents.

Although this study identified four factors driving the selection of smart city verticals, it remains unclear whether all four are present in each of the case study cities. The fact that interview participants in a given city did not allude to a given factor does not necessarily imply that the factor left out is not applicable in the specific context. Similarly, where a number of factors are highlighted in one city does not mean that all are informing vertical selection to the same degree. We suspect that just as the expressions of neoliberal governance are known to vary across geography, modalities and pathways (Brenner et al., Citation2010), the balance of each of the four factors identified as driving vertical selection is likely to vary across cities based on distinct local contexts.

Further empirical research is needed to ascertain the degree to which each of the factors hold sway across different urban contexts. This notwithstanding, the four factors identified can be considered as a lens for thinking through the transformation that is happening in urban environments and in urban governance more broadly, as smart cities become commonplace. It can serve as framework for unpacking the underlying logics and drivers of smart city vertical selection that are often taken for granted or veiled beneath notions of efficiency and improved decision-making (see Batty, Citation2012; Kitchin, Citation2015).

Indeed, the logics which underpin the entrepreneurial governance observed across the case study cities can be usefully understood as representing various types of urban entrepreneurialism: To borrow from Phelps and Miao’s (Citation2020) classification of varieties of urban entrepreneurialism, justifications for smart initiatives which emphasize efficiency can be understood as “new urban managerialism”, while efforts to capitalize upon the smart city label and associated image by boosting the investment potential of the city can be understood as “urban diplomacy”. Tracing the logics of vertical selection also reveals something of the ways in which entrepreneurial approaches to urban governance can transcend growth agendas (see Lauermann, Citation2018), for instance, to enable the delivery of projects or developments for which there is not a clear “business case”. Evidently, tracing the roots of vertical selection enables consideration of precisely what forms of entrepreneurialism are prevalent within particular cities, each with different historical contexts which shape governance approaches.

While popular narratives of smart cities paint them as technical, objective and apolitical, it is clear that this could not be further from reality (Kitchin, Citation2015). Drawing attention to the ways in which certain areas of focus for smart initiatives emerge, and to the variation in smart programs which different drivers for vertical selection produce across different cities, highlights that the processes of decision-making in smart city governance are just as political and complex as in other well-established areas of urban governance.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the research participants from the seven case study cities for their time and invaluable insights without which there will not have been an empirical data to report.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adzimah-Alade, M., Akotia, C. S., Annor, F., & Quarshie, E. N. B. (2020). Vigilantism in Ghana: Trends, victim characteristics, and reported reasons. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 59(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12364

- Angelidou, M. (2015). Smart cities: A conjuncture of four forces. Cities, 47, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.05.004

- Batty, M. (2012). Smart cities, big data. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 39(2), 191–193. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3902ed

- Bolz, K. (2018). Co-creating smart cities. ORBIT Journal, 1(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.29297/orbit.v1i3.66

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Brenner, N., Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Variegated neoliberalization: Geographies, modalities, pathways. Global Networks, 10(2), 182–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00277.x

- Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2002). Spaces of neoliberalism. Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444397499.ch1

- Callon, M. (1940). Elements pour une sociologie de la traduction: La domestication des coquilles saint-jacques et des marins-peˆcheurs dans la baie de saint-brieuc. L’Anne´e sociologique (1940/1948-), 36, 169–208.

- Callon, M., Lascoumes, P., & Barthe, Y. (2009). Acting in an uncertain world: An essay on technical democracy (Graham Burchell, Trans.). MIT Press.

- Cardullo, P., Di Feliciantonio, C., & Kitchin, R. (2019). The right to the smart city. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Cardullo, P., & Kitchin, R. (2019). Smart urbanism and smart citizenship: The neoliberal logic of ‘citizen-focused’ smart cities in Europe. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(5), 813–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X18806508

- Cardullo, P., Kitchin, R., & Di Feliciantonio, C. (2018). Living labs and vacancy in the neoliberal city. Cities, 73, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.008

- Cook, M., & Valdez, A. M. (2021). Exploring smart city atmospheres: The case of Milton Keynes. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 127(October), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.10.015

- Cook, M., & Valdez, A. M. (2022). Curating smart cities. Urban Geography, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2022.2072077

- Cowley, R., & Caprotti, F. (2019). Smart city as anti-planning in the UK. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(3), 428–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818787506

- Cséfalvay, Z. (2011). Searching for economic rationale behind gated communities: A public choice approach. Urban Studies, 48(4), 749–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010366763

- Dillon, J. T. (1982). Problem finding and solving. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 16(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1982.tb00326.x

- Ehwi, R. J., Holmes, H., Maslova, S., & Burgess, G. (2022). The ethical underpinnings of Smart City governance: Decision-making in the Smart Cambridge programme, UK. Urban Studies, 2968–2984. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211064983

- Farías, I., & Blok, A. (2016). Technical democracy as a challenge to urban studies. City, 20(4), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1192418

- Future Cities Catapult. (2016). Smart City Demonstrators: A global review of challenges and lessons learned. Future Cities Catapult.

- Giffinger, R., Fertner, C., Kalasek, R., & Milanović, N. P. (2007). Smart cities. Ranking of European medium-sized cities. Final report. https://doi.org/10.34726/3565

- GMB Congress. (2019). Local government and austerity. CEC special report. Available at: https://www.gmb.org.uk/sites/default/files/GMB19-LocalAusterity.pdf (Accessed 18 April 2021).

- Goodman, N., Zwick, A., Spicer, Z., & Carlsen, N. (2020). Public engagement in smart city development: Lessons from communities in Canada’s Smart City Challenge. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12607

- GOV.UK. (2012). List of councils in England by type. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1140054/List_of_councils_in_England_2023.pdf. (Accessed 15/04/2021).

- GOV.UK. (n.d.). Understand how your council works. Retrieved November 16, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/understand-how-your-council-works.

- Green, B. (2019). Against the Smart City: Putting Technology in its place to reclaim our urban future. Massachusetts University Press.

- Grossi, G., & Pianezzi, D. (2017). Smart cities: Utopia or neoliberal ideology? Cities, 69, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.07.012

- Hämäläinen, M. (2020). A framework for a smart city design: Digital transformation in the Helsinki smart city. In V. Ratten (Ed.), Entrepreneurship and the community: A multidisciplinary perspective on creativity, social challenges, and business (pp. 63–86). Springer. Contributions to Management Science.

- Harding, A., Wilks-Heeg, S., & Hutchins, M. (2000). Business, government and the business of urban governance. Urban Studies, 37(5-6), 975–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980050011190

- Harrigan, K. R. (1984). Formulating vertical integration strategies. Academy of Management Reviews, 9(4), 638–652. https://www.jstor.org/stable/258487

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Gannon, M., Besemer, K., & Bramley, G. (2015). Coping with the cuts? The management of the worst financial settlement in living memory. Local Government Studies, 41(4), 601–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2015.1036987

- HM Government. (2021). Net zero strategy: Build back greener. Crown Copyright.

- Hollands, R. G. (2015). Critical interventions into the corporate smart city. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu011

- Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (2006). The general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146706290923

- Jessop, B., & Sum, N.-L. (2000). An entrepreneurial city in action: Hong Kong’s emerging strategies in and for (inter)Urban competition. Urban Studies, 37(12), 2287–2313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020002814

- Joss, S., Sengers, F., Schraven, D., Caprotti, F., & Dayot, Y. (2019). The smart city as global discourse: Storylines and critical junctures across 27 cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 26(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2018.1558387

- Karvonen, A., Cugurullo, F., & Caprotti, F. (2019). Introduction: Situating smart cities. In A. Karnonen, F. Cugurullo, & F. Caprotti (Eds.), Inside smart cities: Place, politics and urban innovation (pp. 1–12). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kitchin, R. (2015). Making sense of smart cities: addressing present shortcomings. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu027

- Kitchin, R. (2016). Getting smarter about smart cities: improving data privacy and data security. 82.

- Lauermann, J. (2018). Municipal statecraft. Progress in Human Geography, 42(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516673240

- Leleux, C., & Webster, W. (2018). Delivering smart governance in a future city: The case of Glasgow. Media and Communication, 6(4 Reflections and Case Studies), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1639

- Manville, C., Cochrane, G., Cave, J., Millard, J., Pederson, K. J., Thaarup, R. K., Liebe, A., Matthias, W., Massink, R., & Kotternink, B. (2012). Mapping smart cities in the EU. In European Union, Directorate General for Internal Policies.

- Mattern, S. (2019). Instrumental City: The view from Hudson Yards, circa 2019. Places Journal, https://doi.org/10.22269/160426

- McGuirk, P., Dowling, R., & Chatterjee, P. (2021). Municipal statecraft for the smart city: Retooling the smart entrepreneurial city? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(7), 1730–1748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211027905

- Paskaleva, K., Cooper, I., Linde, P., Peterson, B., & Gotz, C. (2015). Stakeholder engagement in the smart city: Making living labs work. In P. M. Rodriguez-Boliva (Ed.), Transforming city governments for successful smart cities (pp. 115–145). Springer.

- Peck, J., Theodore, N., & Brenner, N. (2013). Neoliberal urbanism redux?. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12066

- Phelps, N. A., & Miao, J. T. (2020). Varieties of urban entrepreneurialism. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(3), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820619890438

- Pierre, J. (2012). The politics of urban governance. Urban Policy and Research, 30(3), 344–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2012.702076

- Pollio, A. (2016). Technologies of austerity urbanism: the “smart city” agenda in Italy (2011–2013). Urban Geography, 37(4), 514–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1118991

- Rossi, U. (2016). The variegated economics and the potential politics of the smart city. Governance, 4(3), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2015.1036913

- Shelton, T., Zook, M., & Wiig, A. (2015). The ‘actually existing smart city’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu026

- Söderström, O., Paasche, T., & Klauser, F. (2014). Smart cities as corporate storytelling. City, 18(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.906716

- Survey iGOV & Virgin Media Business. (2019). Smart cities and the digital transformation of local government 2019. Available at: https://www.virginmediabusiness.co.uk/pdf/Insights%20Guides/Built-Environment-Report.pdf (Accessed 16 April 2021).

- Tan, S. Y., & Taeihagh, A. (2020). Smart city governance in developing countries: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030899

- Vanolo, A. (2014). Smartmentality: The smart city as disciplinary strategy. Urban Studies, 51(5), 883–898. doi:10.1177/0042098013494427

- Wiig, A. (2015). IBM’s smart city as techno-utopian policy mobility. City, 19(2-3), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1016275

- Wiig, A. (2016). The empty rhetoric of the smart city: From digital inclusion to economic promotion in Philadelphia. Urban Geography, 37(4), 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1065686