ABSTRACT

Among the many issues that have been discussed under the scholarship of entrepreneurial state, the place of and strategies to mobilize, a shadow state apparatus have so far received little attention. It is particularly relevant from state practices in the Global South. This article gives an account of shadow practices that an entrepreneurial state undertakes in its attempt to deliver a smart city project. It documents a host of practices that essentially blur the boundaries of the formal and shadow state to smoothen business deals and take the neoliberal agendas of the entrepreneurial state forward. The article demonstrates that these shadow practices by formal state actors take place due to the demands of the entrepreneurial zeal of the state, a key facet of neoliberalism. The article contributes toward the scholarship by bringing into focus the salience of caste and kin networks in the quotidian operations of the shadow state.

Introduction

Tripathi (pseudonym), a senior officer in the Town Planning Authority of the provincial Gujarat government was scathing in his attacks on the Chandori Special Investment Region (SIR) Development Authority (CSIRDA), acknowledging errors in the SIR Act and its implementation in Chandori.Footnote1 His admission was significant, as he has chaired many meetings where crucial decisions concerning the planning and implementation of Chandori SIR were taken. Knowing that I was from a UK-based university, Tripathi proudly talked about his son, a graduate in Town Planning from a reputed UK university. He then called his son seated in a room within Tripathi’s office. Tripathi’s large office had adjoining cabins, spacious enough to act as regular offices. After a brief introduction, I followed his son to one of the cabins. As we conversed about different things, life in Gujarat or in the UK, I realized this cabin was effectively his de facto office for the planning and architecture consultancy services he offered. According to him, he often attended to his clients here as he was learning the trade from his experienced father. Even though he started his consultancy very recently, he had an envious portfolio of projects.

Unsurprisingly, he did not acknowledge how the location of his own office inside his father’s office fetched him business. In a society where patronage, favors and bribes are rampant, clients who visit or seek favor from the father with an important office, would often be obliged to hire the son. Here is an individual without any association with the stateFootnote2 undertaking private business by using state spaces. As Harriss-White (Citation2003, p. 89) noted “the shadow state spills into the lanes surrounding state offices and … officials’ residences.” The shadow elements of the state here physically spill into, and are found inside the state offices undertaking private business. These are vivid images of the formal and shadow elements of a state working in tandem with one another, a theme that has not been widely explored in the scholarship on urban entrepreneurialism despite its significance and prevalence.

The above vignette and discussions in the next sections raise questions around the shadow nature of urban governance in India as the state attempts to be entrepreneurial. Such shadow practices of the state actors are widespread and come in different shapes and forms and raise questions around the actors of the state as well as the idea of the state. The state here becomes the field of struggle for the private interest of powerful individuals and blocs. Given the seamless connection between the shadow and the formal elements of the state, an inquiry into these practices is key to understand the idea of the state through its functioning. Disentangling the various facets of the shadow state in practice, this article analyses state policymaking and the institutional architecture that implement projects such as the Chandori SIR. While scholars have covered the Gujarat state’s overlap with the private from a range of perspectives,Footnote3 this article illuminates how personnel and institutions undertake shadow practices due to the pressure on the state to become more entrepreneurial while also trying to corner benefits for themselves. Hence, the reasons are not just a neoliberal logic but also personal motives. It builds upon two different set of concepts, state entrepreneurialism and shadow state, to argue how they are interconnected thereby contributing to newer understandings of the working of the state in the neoliberalFootnote4 era especially within the context of urban entrepreneurialism.

The article brings into focus the salience of caste and kin networks in the quotidian operations of the shadow state. It contributes to our understanding of the shadow state by showing the micropolitics of caste, and kin networks shaping state agendas in the neoliberal era. This shadow state conceptualization advances our understanding of such micro-practices differing subtly and elaborate on other scholars such as Harriss-White's (Citation2003) original coinage of the shadow state.

Understanding Gujarat’s neoliberalism, state entrepreneurialism, its market-friendly policies or its shadow state practices in the recent years requires a reading into the current Indian Prime Minister’s tenure as the Chief Minister heading the Gujarat provincial government from 2001 until 2014.Footnote5 Amongst his key policies, was the SIR Act passed in 2009 to “create large size investment regions and industrial areas” and “develop them as global hubs of economic activity supported by world class Infrastructure” (Government of Gujarat, Citation2009; also see Datta, Citation2015). Chandori was amongst the earliest proposed SIRs. As smart city discourses proliferated across the world, it was claimed that Chandori will be developed as a smart city and hence, came to be referred to as Chandori smart city. To hide the identities of the interviewees, I do not give further details of the place. Notable here is that Chandori is amongst the key projects which he continued to champion and became a key talking point during his first Prime Ministerial campaign in 2014.

The article focuses on the everyday workings of the bureaucracy and its interactions with society, and corporations studying the state through its actors, institutions, and discourses from local to global level, as the state in its everyday form cannot be disconnected from macro-processes and structures (Gupta & Sharma, Citation2006; Joseph & Nugent, Citation1994). Taking forward the possibility of studying the state through everyday bureaucratic practices (Gupta & Sharma, Citation2006; Mitchell, Citation1991), it follows a few key bureaucrats, when they interact with citizen-subjects or international agencies. Specifically exploring the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) called the CSIRDA tasked with delivering the Chandori SIR project, the article brings attention to how the practices of the shadow state transform the newer institutions of the state in the neoliberal era. The SPV here instantiate the shadow state facilitating the blurring of the boundary between state and non-state.

The SPV is located in Udyog Bhawan (Industries’ Building), a large office complex in Sector 19 in Gandhinagar, the provincial capital. I interviewed 10 bureaucrats from CSIRDA involved in the planning and management of the SIR project along with two board members. Simultaneously, I followed them in the office and attempted the same when they visited the Chandori SIR site. Beyond interviews, the fieldwork involved spending long hours hanging out at the office-reception, arriving early for interviews or spending time after the interviews to follow the everyday work taking place at the office.

Next section of the article analyses the concept of state entrepreneurialism and its connections with the shadow state in India. This is followed by an explanation on the entrenchment of neoliberal ideas amongst bureaucrats and the outcome of the presence of non-state actors within state spaces. The following section then provides an insider’s perspective on how there are constant pressures to help investors even if by circumventing the state’s own regulations. This is followed by a story of a powerful bureaucrat’s use of casteFootnote6 and kin relations to carry out successful private real estate projects in Chandori. Through these vignettes, the article explores the inner workings of the state focusing on the importance of caste and kin relations in the functioning of the shadow state in the neoliberal era.

The entrepreneurial shadow state

Scholars including Abrams (Citation1988), or Mitchell (Citation1991) have argued that the entity of state is difficult to define. The state has been interpreted “as a set of discourses” (Hansen & Stepputat, Citation2001; Mitchell, Citation1991), a web of bureaucratic personnel, institutions and practices (Evans et al., Citation1985), a field of politics and power (Bardhan, Citation1984; Jessop, Citation1977; Miliband, Citation1969), a set-up in which the distinction between public and private is blurred (Gupta, Citation1995), or even a unit in which significant action often takes place in proto-state “shadows” dominated by non-state actors (Harriss-White, Citation1997) (summarized in Sud, Citation2008, pp. 3–4). Importantly, the state in practice in Chandori is a multi-faceted, internally differentiated, pluralized entity rather than a homogenous one (Sinha, Citation2011). Through this, the article will point toward a more nuanced, situated understanding of how state policies emerge, how they take root in a particular place, and their impact on the entity of the state.

The term “shadow state” has been initially used to refer to the state in countries such as Sierra Leone which were characterized by “the emergence of rulers drawing authority from their ability to control markets and their material rewards” (Reno, Citation1995, p. 3) especially through the exploitation of precious resources. In a different context, Geiger and Wolch (Citation1986) introduced the term “shadow state” to theorize structural changes in the US and UK nonprofit sectors during the 1970s and 1980s (Mitchell, Citation2001; Trudeau, Citation2008; Wolch, Citation1990). In the context of India, Harriss-White (Citation2003) explained how intermediate classes “colonise the state to further their interests” and expand the scope of what she called the “shadow state” which exists alongside and, in some ways, interlocking with the formal state. The formal state, here, refers to the set of institutions of political and executive control centered upon government while the shadow state represents the practices that are outside the formal counterparts. However, when one analyses the (formal) state and practices of its actors, the line between formal and shadow elements are often blurred. This is certainly the case in Chandori.

At the same time, such shadow practices often have an element of corruption. The shadow state and the practices discussed in this article may or may not be categorized under corruption. Here, the term, shadow, is used under broad categorization to document the presence of an apparatus or a field where various blocs struggle to corner material gains without debating which of those is/are illegal. Some of these practices can be obvious corruption while others are extra mile steps taken by state actors for ease of doing business. In that sense, one can argue that the concept is closer to Partha Chatterjee’s (Citation2001) much discussed political society that described a parallel field of governance in which claims are advanced based on morality rather than legal rights. While this is not the case under the shadow state in the article, both the concepts exist only in relation to the state as they both implicate public servants in informality, and they have a profound influence on the city. However, this article focuses on the state and elites’ practices.

So, is the state a field of competition and conflict or is the state itself a field of struggle? Poulantzas’s (Citation1978) scholarship on the capitalist stateFootnote7 is particularly relevant here as he argued that the principal political role of the capitalist state is organizing the power bloc and disorganizing the popular masses. Its “different apparatuses, sections, and levels serve as power centers for different fractions or fractional alliances within the power bloc and/or as centers of resistance for different elements among the popular masses” (cited in Jessop, Citation1999, p. 48, also see Jessop, Citation1985). Hence “the state here is the strategic field formed through intersecting power networks that becomes a favorable terrain for political maneuver by the hegemonic fraction” (Jessop, Citation1999, p. 48). It is through constituting this terrain that the state helps to organize the power bloc and thus, the state is a field where competing interests ultimately struggle for power. In similar ways, instead of looking at the shadow practices of the state as a marker of corruption, this article analyses it as a reaction to the pressure from the power blocs. The practices that many of the state actors undertake are motivated by disparate intentions.

A key turn to how the state is analyzed is often associated with the advent of neoliberalism, Neoliberal policies were introduced by the federal Indian government in 1991.Footnote8 Although these policies argued for the retrenchment of the state if not outright withdrawal, realities were often different. As with the global trend, the Indian state did not wither away following the introduction of neoliberal policies. Its “central role in social change, politics, and policymaking” remains an “empirical reality” (Mooij, Citation1999, p. 44) while retaining a preeminent place in the popular imagination of the citizens. Importantly in Gujarat, the pressure on the state to step back, or the forward march of non-state actors precedes the 1990s and has been a key reason behind the province’s skewed development and rampant inequality across class, gender and caste.Footnote9

On the other hand, provincial governments competed for investment in the pre-liberalization era. Often referred to as the License Raj, provinces regularly lobbied the central government in New Delhi for a greater share in the Five-year Plans (Kohli, Citation2009; Sinha, Citation2005). There are also many instances of favoritism for designated corporations. Thus, neoliberalism did not necessarily introduce competition amongst provincial governments nor introduced shadow state practices. In similar ways, instead of looking at the shadow practices of the state as a marker of corruption, this article analyses it as a reaction to the pressure from the power blocs. Such shadow practices undertaken by state actors are motivated by disparate intentions. Sometimes it could be entrepreneurialism and at other times, it is the private profit motive of a certain power bloc that uses the state as a field.

The outcome of the neoliberal policies of 1991 was a fundamentally restructured Indian economy which also fueled the growth of urban and real estate sectors. This was manifested in the urban geographies across most cities of the country. The city “captured the imagination of both the state and the private sector as the most important engine of national growth and development and as the site of market expansion and investment” (Gooptu, Citation2016, p. 216). Provincial governments often proposed spatial policies seeking domestic and international investments from private sectors with an idea of competition and free markets gaining prominence in these policies. The Special Economic Zones (SEZ) of the late 1990s and early 2000s are representative of such spatial neoliberal policies in India (Jenkins et al., Citation2014) and the SIRs are mere extensions. Tax breaks, subsidized resources (such as land or water), and provision of physical infrastructure were central to those policies which Harvey (Citation1989) calls part of the state’s attempts at “urban entrepreneurialism.”

To deliver these policies, to become more entrepreneurial and compete against each other for private investments, the Indian state at various levels reformed its institutional architecture making it more market-oriented through institutions such as Special Purpose Vehicles (CSIRDA is an example here). They also became part of governance delivery beyond the implementation of just a certain project. Such distinctive characteristic of this form of state intervention is referred to as state entrepreneurialism where state agencies or certain bureaucratically run public sector units indulge in risk taking and profit maximizing activities (Chen, Citation2013; Pow, Citation2002). Studying the Chinese local state’s role in planning that has seen a profound shift toward state entrepreneurialism, Wu (Citation2018) defines it as state engagement with the market through institutional reform as it demonstrates a greater interest in introducing, developing and deploying market instruments and engages in market-like entrepreneurial activities. Projects such as Chandori SIR are physical manifestations pushing to build a more energetic and entrepreneurial set of state or semi-state organizations.

A growing literature has looked at state entrepreneurialism in India, including in enclaves such as SEZs and SIRs (Das, Citation2015; Datta, Citation2015; Goldman, Citation2011; Kennedy, Citation2013; Kennedy & Sood, Citation2019; Sood & Kennedy, Citation2020). The shadow nature of the phenomenon has also been examined such as the outsourcing of state functions to private groups and consultants (Kennedy & Sood, Citation2019; Sami & Anand, Citation2021). The Gujarat case has been examined in the work of scholars such as Sampat (Citation2016), among others. Hurl and Vogelpohl (Citation2021) provide a global perspective. The case of the Chandori SIR and the shadow practices of the state here adds a new dimension by illuminating the existence of an increasingly blurry boundary between the state and non-state actors who are key stakeholders in the private sector. It demonstrates how public officials occupy non-state spaces for private benefits using their official positions, while private-sector actors function as de facto state representatives for their own benefits. In all, the Gujarat model of state-entrepreneurialism reflects a mode of governance which goes the extra mile to suit the market and private interests characterized by motives of personal benefits delivered through caste and kin relations.

The article makes two inferences which contribute to our understanding of the state. First, neoliberal policies have affected how non-state actors appropriate the state and take up the role of the state, often becoming the face of the state. Second and extended from this is that many such state actors undertake a host of shadow practices to take forward the project of neoliberalism even if often with a motive of personal gain. Shadow practice is a salient feature of state entrepreneurialism in India as the state enthusiastically modifies and adjusts its rules and practices. Whether such practices escalate the speed with which projects are undertaken is one matter, but in the process, a number of usual bureaucratic procedures are skipped.

Making the state efficient and entrepreneurial: neoliberalism and bureaucracy

Das (Citation2005) in his work on the role of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) argues that “the idea that India should liberalise entered the IAS thinking in the early 1980s and gained visible support towards the middle of the decade.” While the support or opposition toward neoliberal policies amongst the IAS was not unified, the upper echelons often formulated policies with full commitment (Das, Citation2005). Following the idea of a small state, the size of the bureaucracy has certainly been trimmed down with significant outsourcing of tasks. Even the number of village level officials in Gujarat, called Talati,Footnote10 has decreased. Earlier, each Talati in the Chandori region had one village to look after. With very few new appointments over the last two decades since the 1990s, most Talatis now are responsible for at least two-three villages. Outsourcing can be witnessed in the revenue department at sub-district levels too. The land record offices contracted private companies to keep IT records, who in turn employ computer operators on paltry salaries.

Neoliberalism amongst bureaucrats

The role of bureaucrats in Gujarat in taking the project of neoliberalism forward is extremely important. Newspaper and magazine articles in Gujarat often mention the role of some of the key bureaucrats in the success of institutions such as Vibrant Gujarat. These same bureaucrats were moved to the Prime Ministers’ Office in New Delhi after the then Gujarat Chief Minister won the national elections in 2014. While the initial reaction toward economic liberalization amongst high-ranking bureaucrats was mixed, by the end of the 1990s, there seemed to be a consensus amongst the higher levels of bureaucracy about the role of neoliberal policies in advancing India’s economy (Das, Citation2005; Mooij, Citation2005). Many of these bureaucrats became cheerleaders for these policies.

Since the staff of INFINITY (the global consultants hired for Chandori SIR) and CSIRDA shared the same office, I once asked a senior manager at CSIRDA, about how he views the overlap of the role of INFINITY and CSIRDA. He had this to say:

Importantly, here we have government officials who work for 8 hours a day continuously. That is because they see the INFINITY people, seated in the same office, (work) for 10 hours a day. There is pressure on our people, so they are much more efficient now … We need to learn the ethos from private sector and then we can become efficient and entrepreneurial. Whatever organisational structure and system we are developing for Chandori, there will be a brand of corporate-government culture. We are not strictly government because if we follow government rules and way of working, nothing can happen … We have to become entrepreneurial … (Therefore), having INFINITY inside has improved our speed, made us more efficient and productive … . (Interview with CSIRDA bureaucrat, in 2017)

I see it as a very positive development. Firstly, we do not want government departments to swell too much. That talk is everywhere. (The government needs) to cut down on size and expenditure. It is better to outsource, to achieve higher efficiency. (Secondly), there is a perception that government departments are very bad and not managed properly, and private sector is good … However, (with INFINITY) we are engaging world-class consultants, to create a world-class city … In the future, however, it will also lead to capacity building of government organisations. When the contract with INFINITY terminates, CSIRDA will have a team strong enough to handle what INFINITY has been doing. (Interview with CSIRDA bureaucrat, in 2017)

Similarly, both underlined the need to make the state more “entrepreneurial,” a neoliberal tenet. In the infrastructure and urbanization sectors in particular, such endeavor was made through institutions such as SPVs. In achieving “state entrepreneurialism,” the CEO found a key role for INFINITY as it brought “world-class” practices to the countryside of Gujarat. In the longer run, INFINITY in his view would contribute toward the capacity building of CSIRDA. Such statements are evidence of the state’s attempt to be entrepreneurial.

The state/non-state conundrum: the case of INFINITY

Beyond making the CSIRDA’s staff work for longer hours, the outcome of INFINITY’s involvement was rather different from what the CEO claimed. Analyzing the practices of the state here, it is worth noting the everyday practices inside the state office that reflect a negotiation of state vs. non-state relations. INFINITY’s staff have created a space for themselves and are often perceived as state actors. In fact, INFINITY embodies what one observer described as “the only constant in the office.”Footnote12 INFINITY plays a key part in the processes of negotiation of the CSIRDA. INFINITY staff were often the face of the project to deal with a possible investor visiting the CSIRDA office. Whereas this could have involved a synergy between INFINITY and CSIRDA in managing daily affairs, such practices instead involved INFINITY staff acting on behalf of the state, creating an impression that they were part of the state.

This was evident from my interactions with visitors to the CSIRDA office. Those who visited multiple times (such as real estate developers from Chandori) named the staff of INFINITY as the “high-ranking officials who are very good at getting things done.” They could rarely differentiate between the INFINITY staff and the bureaucrats of CSIRDA. Many of them considered Srivastava (Project Lead from INFINITY) to be the head of CSIRDA and described him as the “constant” presence whereas “people like CEO (he spelled the name) keep coming and going.” To a business delegate, Srivastava exuded “confidence, power and continuity while interacting with them even if in the company of state officials.”Footnote13

Srivastava represented a center of power in the office other than the CEO of CSIRDA. Srivastava was the mainstay whereas the IAS officers in charge of CSIRDA were transferred or promoted regularly. The CEO whom I interviewed, for instance, was transferred in August 2019, exactly two years after he joined whereas the INFINITY lead staff remained the same. For a long time, the CEO post remained vacant or was delegated to officers as an additional responsibility. Discussing the role of Srivastava, a junior INFINITY staff told me:

It is because of Srivastava sir that the project is still on … He is decisive and knows whom to pressurise and how to handle the bureaucrats. I will give you an example: getting the water for Chandori … We kept revolving around five different sources and were back to square one after a year or two. Then, we had a meeting with the Principal Secretary and Srivastava sir made sure that all those five bureaucrats (head of these water sources) were summoned. He told them that “if you are not giving me water, I can get other sources but do not mess around with me. You will be transferred in two years. Someone new will come to ask me to start it again” … . (Interview with INIFINITY staff, in February 2018)

… The country needs the project. It will give a sudden boost to the economy. You must have seen Mr. Prime Minister stressing on its importance. The key aspect is the size and scale of Chandori. It is bigger than Singapore. Mr. Prime Minister wants this to be realised as soon as possible and we are putting our best efforts. He is behind us … . (Interview with INIFINITY staff, in February 2018)

The position of INFINITY, the authority of Srivastava and the perception that businesses have of them raise a fundamental question: are these corporate actors part of the state? This is especially significant in the post-liberalization context in India when existing bureaucratic structures have collaborated with new actors such as INFINITY. INFINITY’s staff are not officially part of the bureaucratic structure of CSIRDA but work from the same space and hence straddle the formal and shadow spaces of the state. In working simultaneously from both inside and outside of the state spaces, INFINITY mediates the relations between state and businesses. Through these practices, they have become part of the state in Gandhinagar.

Figure 1. Local property dealer welcoming a Chinese business delegate. This was on the sideline during the visit of a Chinese group to Chandori SIR. Source: The picture is from the official websites of the real estate companies.

The governing body of CSIRDA: politicking and breaching of the state

As the state tries to become more entrepreneurial and lure investors, state actors undertake a host of shadow practices. Here, the formal and shadow elements flow into one another smoothly and their movement create a new image of the state as well as new state actors who constitute the state. These new actors blur the lines between formal and shadow elements in light of a large infrastructure project, as we witness the state’s changing relationship with society and the market or business. They underline the importance of practices in the shadow state, and as I show below, these practices occur even at the highest echelons of the state, whether amongst Board Members of CSIRDA or bureaucrats, architects and planners who have worked with CSIRDA in various capacities.

Mishra (pseudonym) is one of the Board Members of CSIRDA. Once while talking about how there was always political pressure on the members to move forward in the project without particular care for the details, he described certain events during the stages of Chandori’s initiation. While looking into the details of the companies, which signed Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with the government, I came across one company, which was registered under the name of Chandori even before the announcement of the project.Footnote16 Mishra told me about an interaction with one senior bureaucrat, Saha (pseudonym) after a board meeting that took place around November-December 2008. The Chandori SIR project was being finalized around this time and a conceptual “Master Plan” had just arrived from the consultants:

… At the meeting when we were shown the “conceptual master plan” of Chandori for the first time, Saha said: “We will implement this.” I said: “The plan has to be worked out. It is still sketchy.” (Saha said:) “Sir, whatever you have to do, you can do later. You please approve it today. Write your complaints, we will look into it. However, if you are going to sit on this or reject, I am going to lose my job tomorrow … .” (I said:) “But this is incomplete. Even the zones are not complete.” He went on: “Sir, I will come to your home for dinner. We can arrange some funds for your institute (takes the name) … Or else I will have to change the board. You will not be in the board from tomorrow … Vibrant Gujarat is in 2 months’ time. We have the investors from Singapore … are (sic) onboard. Where will we give them lands from if this is not approved?” The board approved this … . (Interview with Mishra in February 2018 in Gandhinagar)

Similar incidents of exceptions are quite widespread, such that the state of exception is so common that it comes across as routine (Das & Poole, Citation2004). For example, the government launched the Chandori port project in 2002. Surprisingly, a company named “Chandori Port and Special Economic Zone Limited” was already registered in 1998 as records from the website of MCA21, operated by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs of India, clarify. This was much before anything was heard about the Chandori port project and more interestingly, even before the concept of SEZ was in place. From the analysis of land sale records of the Chandori SIR region it was clear that the first set of sudden sales or outside buyers arriving in Chandori began around 2000 and although the port project along with an industrial estate was officially launched in 2002. Offices of real estate companies started mushrooming around 2000. Hence, peak land sale started before the announcement of the project underlining the insider information that must have been used.

However, such exceptions in the name of ease of business have been a commonplace in the Indian state, both historically and in the current scenarios. As argued earlier, the era of “License Raj” is wrought with such favoritism (Sinha, Citation2005). In the neoliberal period, however, as scholars across the globe (Ong, Citation2006) or on India (Sood & Kennedy, Citation2020) have shown, such exception has also received an official mechanism. The observations raise questions whether these practices signify illegality, corruption and also, why I prefer to call them shadow. On one hand, these “exceptions” are an outcome of the entrepreneurial zeal which the state needs to inculcate to become more “efficient” or “professional” as the CSIRDA bureaucrats earlier argued. At the same time, this entrepreneurial zeal has resulted in a series of shadow practices by the state and by the many people with such information who used them to corner personal benefits. The passing of information to businesses, possibly by bureaucrats, is one case in point. Whether these practices escalate the speed of project delivery is one matter, but in the process, a number of usual bureaucratic procedures are skipped. The informal luring, threatening or arm-twisting to approve the planning drawings of the project illustrate how shadow practices are undertaken. While the obligations of a neoliberal ideology may compel the state or its personnel to become “competitive” and “entrepreneurial,” the state undertakes shadow practices and becomes the “state of exception” (Ong, Citation2006). At the same time, this is also motivated by private interests as the next section will document.

An official’s use of caste, kinship and the state

A salient feature of the shadow state proposed in this article is the network of caste and kin relationships that often thrive the shadow practices. Shadow state practices overlap with caste and kin networks and understanding these networks is key to illuminating the practices and disentangling the idea of the state. Scholars have pointed out that the state is no neutral arbiter when it comes to the social relations of caste or kin (Harriss-White, Citation2003, p. 191). Since the neoliberal policies were launched in the 1990s, the state or the market never attempted to abolish or transform such existing relations. Rather, it “encourage(d) them to rework themselves as economic institutions and to persist” (Harriss-White, Citation2003, p. 191). As both caste and religion are practiced in a flexible manner, they “generate exclusive, networked forms of accumulation and corporatist forms of economic regulation” as the vignette below manifests (Harriss-White, Citation2003, p. 191).

Mihir (pseudonym) was previously a muscleman cum middleman operating in land deals. His role involves brokering a land deal charging a fixed sum from the buyer. However, when he comes across obstinate sellers, using muscle power is “part of the job.” Once, he vividly explained his first major deal: a “Collector” from Gandhinagar was buying land for a company named “Suzlon” that deals in wind energy and planned to set up an SEZ in Chandori.

… This company (Suzlon) wanted more land from that area. Kaushik Dhanani did the entire deal for Rampur’s (name of village) land … Being a Patidar,Footnote18 he was the main person of the Minister’s daughter in Chandori … What happens is companies like Suzlon cannot buy such a massive tract of land. They hire people like Kaushik … They ask Kaushik to buy as he is responsible, being a government official. Then, he can buy in anyone’s name; Suzlon is not concerned because they will get hold of Kaushik whenever they want … Then, Kaushik needs us to buy the land on the ground … So, after a couple of months … Kaushik started his projects in Nagar (pseudonym) from the same money probably.

Which project?

Smart Township (name changed) next to Chandori Hotel (name changed) on the highway … I am not sure about the real owner, but the Minister’s daughter is certainly there. However, he is the man behind it and some other projects as well.

While this set of promotions in such a brief span is remarkable, Kaushik’s moonlighting is no less extraordinary, illuminating the intricate working of the shadow state taking caste and kin networks onboard in neoliberal India. Real estate dealers in Chandori often claimed that the Smart Township project (mentioned above) has been very successful in the region. The informants argue: “it belonged to Patidars and second, they have connections in the ministry and the SIR Office” (Interview with real-estate dealers in Chandori). In a society where caste is a consistent marker of personal, professional or political relationships, Patidar buyers first went to Kaushik. Secondly, their bureaucratic and political connections in Gandhinagar gave buyers additional faith in their transactions. Also, the project was supposedly owned by the daughter of an important Minister, who was a Patidar.

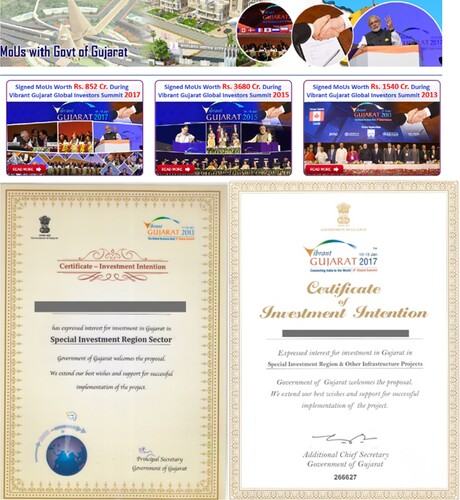

Kaushik’s private office dealing with these projects was in Sector 8 where he undertook his shadow role while his government position at GIDB/CSIRDA in Sector 19 was barely 3 kilometers away. When I looked at the Registrar of Company’s records to find the registration details of the company that promoted Smart Township, the address of the company was the same as where Kaushik’s residential office in Sector 8 was located. On the website of Smart Township, MoUs worth billions of Indian rupees (INR)Footnote19 signed with the Government of Gujarat during the biennial VGGS were uploaded. At the 2015 VGGS, when Anandiben Patel (a Patidar) was the Chief Minister, the website claimed to have signed MoUs worth INR 36 billion, which dipped to INR 8 billion in the VGGS 2017 by the time a new Chief Minister was in place (). Along with its own projects, the website regularly uploaded recent pictures on the progress of construction of SIR undertaken on behalf of the government. This often created an ambiguity and made Smart Township appear like a government-promoted project. At the Gujarat Patidar Business Summit 2018 held in Gandhinagar, Kaushik’s company participated actively () and drew immense interest being the only representation from the much talked about Chandori smart city.

Figure 3. Screenshots of Smart Township’s MoUs. Source: Smart Township website.

Figure 4. Smart Township’s stall at the Gujarat Patidar Summit. Source: Smart Township website.

However, around 2017–2018, Kaushik has been facing the heat from various sides after a new Chief Minister came to power in Gujarat. A departmental inquiry was launched against him although information has not been divulged. This was further corroborated by a number of complaints against Kaushik and Smart Township, which appeared online on multiple websites that report consumer complaints (). Complaints ranged from cheating to how Kaushik used his connections to suppress the voices of complainants. One buyer, who worked as a small businessperson in Ahmedabad complained of being cheated as there was not much progress in the Township.

Figure 5. Screenshots of online complaints against Kaushik and his company on consumer forums. Source: Compiled by author.

These networks are hard and risky for researchers to break into, while finding a document trail to prove it is near impossible. Yet the evidence above suggests that these claims are not completely unfounded. The Minister’s daughter has been caught in a massive land fraud in a nearby district for getting government-owned land at a 92% discounted rate.Footnote20 One cannot ignore the fact that when the Chief Minister was a Patidar, Kaushik’s company signed MoUs worth more than four times compared to two years later, when the Patidar Chief Minister was replaced. At the same time, Suzlon Energy Limited, for which Kaushik was buying land through Mihir, was owned by a Patidar. A bureaucrat like Kaushik blurs the line between the state and non-state. He enabled a large private company such as Suzlon to aggregate land, and for that he used his position at the revenue department and later at the GIDB. To target a specific seller, one needs to know the survey numbers and ownership details of the land that Kaushik automatically had access to from these offices.

In addition, Kaushik drew power from his Patidar kinship networks to undertake his shadow practices. Hence, within these dynamics involving the shadow state manifesting neoliberalism, traditional caste and kin relations play an important role, something scholars of the Indian political economy has earlier established. David Mosse (Citation2020) has argued that current economic and political forces have simultaneously weakened and revived caste in ways that defy easy generalization. Historically accumulated “caste capital” is flexible enough to “suit new institutional orders and opportunity structures” (Bandyopadhyay, Citation2016). Similarly, Harriss-White (Citation2003, pp. 176–200) argued that under market economy caste continues to be what she calls a “social structure of accumulation” for Indian capitalism. Kaushik’s moonlighting that blurs the public–private or formal-shadow boundaries sums up the entrepreneurial state, be it in Gandhinagar or in Chandori. Importantly, these fuzzy boundaries of the public–private or state–non-state are not just an outcome of their poor categorization but arise from the shadow practices of state actors such as Kaushik who constantly unmake these boundaries. Caste and kin relationships become the logic through which shadow practices are undertaken while also taking forward the project of neoliberalism.

Conclusion

Through an ethnography of state practice in the urban development projects in India, the articles documented the prominence of caste and kin networks in the quotidian operations of the shadow state especially in the neoliberal era. The micropolitics of such caste and kin networks shaping these agendas are key to understand the shadow state that is in practice. Organizations such as SPV that are tasked with delivering such projects become the key field for these practices as highlighted in the article. The article examined the consequences of shadow practices of state and non-state actors in the neoliberal era through a series of disparate but connected vignettes. As services are outsourced, such practices help theorize how the state’s relationship with the society and market has emerged. Two key ideas emerge here that contribute toward our understanding of the state. First, neoliberal policies have affected how new entrants into the state’s bureaucratic architecture appropriate the state and often become the face of the state. Second, state actors undertake a host of shadow practices with motives of personal gain that may also help take forward the project of neoliberalism. Occasionally, there are shadow practices that take place due to the demand of the entrepreneurial zeal of the state as well.

The article also sheds light on new entrants such as private consultants that have now come to represent the state manifesting the new emerging state structures in the neoliberal era. Not only do state actors advocate the intrinsic virtue in private entities participating in public affairs, but bureaucrats use a neoliberal argument to explain why the public sector needs to learn from the private: the traditional state is inefficient or unprofessional and these new state actors represent the opposite. As private consultants collaborate with the state to undertake functions previously the preserve of the state, the state is being re-imagined at every level in the process. Non-state personnel are often perceived as representing the state by citizens as they experience the state through these actors. Despite being located outside the formal bureaucratic apparatus, the private consultancy has very much become integrated into the state and entrenched in bureaucratic hierarchies.

This also opens the field of the state for shadow practices. In order to professionalize the state or make it more efficient and entrepreneurial, a number of shadow practices are adopted that also ensure private benefits. Usual bureaucratic procedures or protocols are bypassed by the entrepreneurial state to become “more efficient and get business done.” The ubiquity of business transactions makes shadow practices routine, and such activities are no longer the exception. Hence, it opens up spaces for caste and kin relations to corner the benefits using the state. The vignettes also underline how studying, following and observing the bureaucrats’ many interactions with citizens or with international organizations tasked with delivering a certain tenet of development provides us new understandings of the state.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of my PhD thesis completed at the University of Oxford. I received greatly valuable critically engaging feedback from Nikita Sud (PhD Supervisor), Sudheesh R C (National Law School of India University, Bengaluru), Fulong Wu (UCL), Nick Phelps (University of Melbourne) at various stages of this article. Special thanks to the two anonymous reviewers and Ayona Datta at Urban Geography for their insightful suggestions. Thanks also to the anonymous interviewees in Gujarat, India for their time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Gujarat is a province along the western coast of India and Gandhinagar is its administrative capital. All names of interviewees and places are anonymized (unless otherwise stated) to protect the identity of the individuals. Chandori is not the real name of the place. The provincial government of Gujarat passed the Special Investment Region (SIR) Act in 2009 specifically to develop new townships and industrial areas (See Datta, Citation2015).

2 “State” and the shadow state are discussed in more detail in later sections. Indian regions are also called “states”. However, I prefer to use “province” throughout the article to avoid confusion.

3 Existing scholarship has covered Gujarat state’s shadow practices from different dimensions. Guha Thakurta, Citation2015; Jaffrelot (Citation2019) shed light on what is mostly labelled as crony capitalism. Others including Bahree (Citation2014), Lobo and Kumar (Citation2009), Sud (Citation2009) cover instances of state’s role in land grab in Gujarat for corporations. Sud (Citation2009) has made an argument in the case of Gujarat that it exemplified a “business friendly” pattern, more than a “market-friendly” economy that Kohli (Citation2006a, Citation2006b) argued for India. Also, see note 5.

4 Neoliberalism refers to the laissez-faire economic liberalism practiced since the 1980s, including policies such as privatisation, free trade agreements between nations, state deregulation, the opening up of financial markets, encouragement of foreign direct investment, and reductions in government spending in order to increase the role of the private sector in the economy (Harvey, Citation1989, Citation2005).

5 This should not undermine the importance of the existing business friendly policies before 2001. Gujarat has been one of the most economically liberal states since India’s independence possibly down to its mercantile history due to its location along the Indian Ocean with a long coastline. In fact, a number of policies (such as Special Economic Zones) and institutions (Gujarat Infrastructure Development Board) were already in place. The Chief Minister (2001–2014) then promoted a slew of new policies such as the SIR Act while implementing the existing policies with a mix of entrepreneurial and authoritative tendencies and a dose of right-wing Hindu nationalism. Scholars have shown how right-wing Hindu nationalism was packaged together with neoliberal policies (See Akhtar, Citation2022; Bhattacharjee, Citation2019; Desai, Citation2008; Mahadevia, Citation2005; Simpson, Citation2013; Spodek, Citation2011; Sud, Citation2012; Yagnik & Sheth, Citation2005).

6 Caste in India refers to the four subdivisions of the traditional Hindu hierarchy: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (merchants), and Shudras (labourers). Dalits, treated as the “untouchable” caste lie outside it.

7 As explained earlier, the current Indian state is certainly closer to a capitalist state and the Gujarat state is no exception. Also, the last vestiges of socialism were wiped out with the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s.

8 The scholarship on Indian neoliberalism covers most aspects on the context or the events leading to its initiation as well as its outcomes over the decades. Refer to Bardhan (Citation2000), Bhagwati (Citation1993), Jenkins (Citation1999), Kohli (Citation2006a, Citation2006b), Mooij (Citation2005). For the scholarship on spatial policies of the state, refer to Kennedy (Citation2013), Levien (Citation2018), Mahadevia (Citation2005).

9 Scholars have shown that this was very clearly the case of Gujarat’s political economy from the 1970s until the 1990s. See Breman (Citation1985), Hirway (Citation1995), Hirway and Mahadevia (Citation2005); Rutten (Citation1995), Streefkert et al. (Citation2002).

10 Talatis are government officials in rural Gujarat tasked with duties such as maintaining crop and land records of the village, collection of tax revenue and irrigation dues.

11 The words commonly appeared during the interviews with both officials.

12 Interview with business delegate, a manager of a real estate company, in January 2018 in Ahmedabad.

13 Interviews with business delegate in December 2017 and January 2018. The quoted texts are from interviewees.

14 Interview with business delegates in February 2018 and in November 2017.

15 Interview with business delegates in November 2017 and January 2018.

16 Due to the sensitive nature of the information and to protect the security of the interviewee, I do not provide the granular details.

17 These records can be accessed officially for a small fee from the website of MCA21 and operated by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs of India (http://www.mca.gov.in/).

18 Patidar is a landed upper-caste community mainly from the province of Gujarat and has a significant diaspora spread across Europe, North America, and Africa.

19 “INR” (₹) or variously termed “Rupees” or “Rs” refers to the currency of India. At the current exchange rate (as of September 2021), 1 GBP equals INR 103.

20 While this news was published in national and regional newspapers, I am not citing it to hide the names.

References

- Abrams, P. (1988). Notes on the difficulty of studying the state (1977). Journal of Historical Sociology, 1(1), 58–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.1988.tb00004.x

- Akhtar, R. (2022). Protests, neoliberalism and right-wing populism amongst farmers in India. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2096446

- Bahree, M. (2014, March 28). Doing big business in Modi’s Gujarat. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/meghabahree/2014/03/12/doing-big-business-in-modis-gujarat

- Bandyopadhyay, S. (2016). Another history: Bhadralok responses to Dalit political assertion in colonial Bengal. In U. Chandra, G. Heierstad, & K. Nielsen (Eds.), The politics of caste in West Bengal (pp. 35–59). Routledge.

- Bardhan, P. (1984). The political economy of development in India. Basil Blackwell.

- Bardhan, P. (2000). The political economy of reform in India. In Z. Hassan (Ed.), Politics and the state in India (pp. 158–174). Sage Publications India.

- Bhagwati, J. (1993). India in transition: Freeing the economy. Clarendon Press.

- Bhattacharjee, M. (2019). Disaster relief and the RSS: Resurrecting ‘religion’ through humanitarianism. Sage Publications.

- Breman, J. (1985). Of peasants, migrants and paupers: Rural labour circulation and capitalist production in west India. Oxford University Press.

- Chatterjee, P. (2001). On civil and political society in post-colonial democracies. In S. Kaviraj & S. Khilnani (Eds.), Civil society: History and possibilities (pp. 165–178). Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, Y. (2013). Neoliberal-inspired large-scale urban development projects in Chinese cities. In M. E. McCarthy (Ed.), The Routledge companion to urban regeneration (pp. 77–87). Routledge.

- Das, D. (2015). Hyderabad: Visioning, restructuring and making of a high-tech city. Cities, 43, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.11.008

- Das, S. K. (2005). Reforms and the Indian administrative service. In J. Mooij (Ed.), The politics of economic reforms in India (pp. 171–196). Sage Publications.

- Das, V., & Poole, D. (2004). Anthropology in the margins of the state. School of American Research Press.

- Datta, A. (2015). New urban utopias of postcolonial India. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565748

- Desai, R. (2008). The globalising city in the Time of Hindutva: The politics of urban development and citizenship in Ahmedabad, India [PhD thesis, dissertation, University of California, Berkeley]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/304697081?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Evans, P. B., Rueschemeyer, D., & Skocpol, T. (Eds.). (1985). Bringing the state back in. Cambridge University Press.

- Geiger, R. K., & Wolch, J. R. (1986). A shadow state? Voluntarism in metropolitan Los Angeles. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 4(3), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1068/d040351

- Goldman, M. (2011). Speculating on the next world city. In A. Roy & A. Ong (Eds.), Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global (pp. 229–258). Blackwell.

- Gooptu, N. (2016). Divided we stand: The Indian city after economic liberalization. In K. A. Jacobsen (Ed.), Routledge handbook of contemporary India (pp. 216–231). Routledge.

- Government of Gujarat. (2009). The Gujarat Special Investment Region Act, 2009. The Gujarat Government Gazzette, L(3), 1–18. https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_states/gujarat/2009/2009Gujarat2.pdf and https://www.gidb.org/pdf/sirord.pdf

- Guha Thakurta, P. (2015). The incredible rise and rise of Gautam Adani: Part one. The Citizen. https://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/NewsDetail/index/1/3375/The-Incredible-Rise-and-Rise-of-Gautam-Adani-Part-One

- Gupta, A. (1995). Blurred boundaries: The discourse of corruption, the culture of politics, and the imagined state. American Ethnologist, 22(2), 375–402. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1995.22.2.02a00090

- Gupta, A., & Sharma, A. (2006). The anthropology of the state: A reader. Blackwell Publishing.

- Hansen, T. B., & Stepputat, F. (2001). States of imagination: Ethnographic explorations of the postcolonial state. Duke University Press.

- Harriss-White, B. (1997). Informal economic order: Shadow states, private status states, states of last resort and spinning states: A speculative discussion based on S. Asian case material (QEH Working Paper Series, 6(1)). Queen Elizabeth House.

- Harriss-White, B. (2003). India working: Essays on society and economy. Cambridge University Press.

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Hirway, I. (1995). Selective development and widening disparities in Gujarat. Economic and Political Weekly, 30(41/42), 2603–2618.

- Hirway, I., & Mahadevia, D. (2005). Gujarat human development report, 2004. Mahatma Gandhi Labour Institute.

- Hurl, C., & Vogelpohl, A. (2021). Professional service firms and politics in a global era. Public policy, private expertise. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jaffrelot, C. (2019). Business-friendly Gujarat under Narendra Modi: The implications of a new political economy. In C. Jaffrelot, A. Kohli, & K. Murali (Eds.), Business and politics in India (pp. 211–233). Oxford University Press.

- Jenkins, R. (1999). Democratic politics and economic reform in India. Cambridge University Press.

- Jenkins, R., Kennedy, L., & Mukhopadhyay, P. (2014). Power, policy, and protest: The politics of India’s special economic zones. Oxford University Press.

- Jessop, B. (1977). Recent theories of the capitalist state. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1(4), 353–373.

- Jessop, B. (1985). Nicos Poulantzas: Marxist theory and political strategy. Macmillan.

- Jessop, B. (1999). The strategic selectivity of the state: Reflections on a theme of Poulantzas. Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora, 25(1–2), 1–37.

- Joseph, G., & Nugent, D. (Eds.). (1994). Everyday forms of state formation: Revolution and the negotiation of rule in modern Mexico. Duke University Press.

- Kennedy, L. (2013). The politics of economic restructuring in India: Economic governance and state spatial rescaling. Routledge.

- Kennedy, L., & Sood, A. (2019). Outsourced urban governance as a state rescaling strategy in Hyderabad, India. Cities, 85, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.09.001

- Kohli, A. (2006a). Politics of economic growth in India, 1980–2005: Part I: The 1980s. Economic and Political Weekly, 41(13), 1251–1259.

- Kohli, A. (2006b). Politics of economic growth in India, 1980–2005: Part II: The 1990s and beyond. Economic and Political Weekly, 41(14), 1361–1370.

- Kohli, A. (2009). Democracy and development in India: From socialism to pro-business. Oxford University Press.

- Levien, M. (2018). Dispossession without development: Land grabs in neoliberal India. Oxford University Press.

- Lobo, L., & Kumar, S. (2009). Land acquisition, displacement and resettlement in Gujarat: 1947–2004. Sage Publications India.

- Mahadevia, D. (2005). From stealth to aggression: Economic reforms and communal politics in Gujarat. In J. Mooij (Ed.), The politics of economic reforms in India (pp. 291–321). Sage Publication.

- Miliband, R. (1969). State in capitalist society. Quartet Books.

- Mitchell, K. (2001). Transnationalism, neo-liberalism, and the rise of the shadow state. Economy and Society, 30(2), 165–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140120042262

- Mitchell, T. (1991). The limits of the state: Beyond statist approaches and their critics. The American Political Science Review, 85(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962879

- Mooij, J. (1999). Food policy and the Indian state: The public distribution system in South India. Oxford University Press.

- Mooij, J. (Ed.). (2005). The politics of economic reforms in India. Sage Publication.

- Mosse, D. (2020). The modernity of caste and the market economy. Modern Asian Studies, 54(4), 1225–1271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000039

- Ong, A. (2006). Neoliberalism as exception: Mutations in citizenship and sovereignty. Duke University Press.

- Poulantzas, N. (1978). State, power, socialism. Verso.

- Pow, C. (2002). Urban entrepreneurialism, global business elite and urban mega development: A case study of Suntec city. Asian Journal of Social Science, 30(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685310260188736

- Reno, W. (1995). Corruption and state politics in Sierra Leone. Cambridge University Press.

- Rutten, M. F. (1995). Farms and factories: Social profile of large farmers and rural industrialists in west India. Oxford University Press.

- Sami, N., & Anand, S. (2021). Expert advice? Assessing the role of the state in promoting privatized planning. In C. Hurl & A. Vogelpohl (Eds.), Professional service firms and politics in a global era (pp. 273–292). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sampat, P. (2016). Dholera: The emperor's new city. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(17), 59–67.

- Simpson, E. (2013). The political biography of an earthquake: Aftermath and amnesia in Gujarat, India. Hurst.

- Sinha, A. (2005). The regional roots of developmental politics in India: A divided leviathan. Indiana University Press.

- Sinha, A. (2011). An institutional perspective on the post-liberalization state in India. In A. Gupta & K. Sivaramakrishnan (Eds.), The state in India after liberalization: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 65–84). Routledge.

- Sood, A., & Kennedy, L. (2020). Neoliberal exception to liberal democracy? Entrepreneurial territorial governance in India. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1687323

- Spodek, H. (2011). Ahmedabad: Shock city of twentieth-century India. Indiana University Press.

- Streefkert, H., Shah, G., & Rutten, M. (Eds.). (2002). Development and deprivation in Gujarat. Sage Publications.

- Sud, N. (2008). Narrowing possibilities of stateness: The case of land in Gujarat (QEH Working Paper Series QEHWPS163). University of Oxford, Queen Elizabeth House.

- Sud, N. (2009). The Indian state in a liberalizing landscape. Development and Change, 40(4), 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01566.x

- Sud, N. (2012). Liberalization, Hindu nationalism and the state. Oxford University Press.

- Trudeau, D. (2008). Towards a relational view of the shadow state. Political Geography, 27(6), 669–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.07.002

- Wolch, J. R. (1990). The shadow state: Government and voluntary sector in transition. The Foundation Center.

- Wu, F. (2018). Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Studies, 55(7), 1383–1399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017721828

- Yagnik, A., & Sheth, S. (2005). The shaping of modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva and beyond. Penguin Books.