ABSTRACT

This paper explores asylum seekers’ experiences of urban arrival infrastructures, illustrating how these provide asylum seekers with opportunities for familiarization with the reception location and its inhabitants. Drawing on two qualitative case studies in Augsburg, Germany, three different subsets of arrival infrastructures emerged as relevant to familiarization; infrastructures for information, for language learning and for social connection. The analysis shows how asylum seekers are differentially positioned towards accessing informational, language-learning and social infrastructures due the intersection of spatial, institutional and personal constraints. Public and semi-public spaces proved to be indispensable to asylum seekers’ informational, language learning and social infrastructures. The paper concludes by highlighting the ambiguity and political nature of urban arrival infrastructures: While state-provided, formal infrastructures often undermined the process of familiarization and contributed to asylum seekers’ differential access to opportunities and resources, informal, citizen-provided infrastructures were crucial in supporting asylum seekers’ needs during the periods of uncertainty.

Introduction

While the relationship between migrants and urban areas is a cornerstone of urban geographical writing, theorizing and analysing relationship between forced migrants and urban areas is newer in focus (Darling, Citation2017). Earlier studies of forced migration have predominantly examined the role of the nation-state in managing and controlling migration, with forced migrants as the “voiceless victim” whose “rightful place” is the camp (Sanyal, Citation2012). Recent contributions in urban geography are calling instead for a focus on “the city as a space for refugee politics” (Darling, Citation2017, p. 2), highlighting how cities are not only sites of everyday bordering and state control (Dempsey, Citation2020), but also sites of where state discourses and practices are negotiated and contested (Darling, Citation2013, p. 2017; Squire & Darling, Citation2013). Within this reading, forced migrants are themselves city makers engaging in protest, activism and place-making processes (Kreichauf & Glorius, Citation2021; Simsek-Caglar & Schiller, Citation2018).

The tensions between cities as sites of “policing” as well as of “politicization” (Darling, Citation2017) are captured within work on urban infrastructures and how these facilitate, negotiate or politicize the arrival and future mobilities of forced migrants (Darling, Citation2021; Kreichauf & Mayer, Citation2021; Meeus et al., Citation2019). What is still insufficiently understood within this literature is which material and immaterial aspects of arrival infrastructures provide opportunities or create constraints for asylum seekers to find a sense of temporary stability beyond a teleological focus on the permanency or temporariness of migration. In this paper, arrival is approached as a period of familiarization with the local context and its inhabitants; a period in which in-depth knowledge and direct experience with the reception location and its inhabitants proves crucial to asylum seekers’ future trajectories. Based on thirty interviews with current or former asylum seekers living in two asylum centres in Augsburg, Germany, the article illustrates how asylum seekers’ experiences of arrival are profoundly shaped by being able to access different urban arrival infrastructures. Arrival in an urban reception location means access to infrastructures for information, language learning and social connection. The article also shows how asylum seekers’ subjectivity and personal needs, such as eating or sleeping, intersect with institutional and spatial constraints, thereby preventing access to urban arrival infrastructures.

By focusing on asylum seekers’ experiences of urban reception locations and how differential access to urban arrival infrastructures influences the process of familiarization, the paper contributes to debates on urban infrastructures (Schwanen & Nixon, Citation2019) and its intersection with infrastructures of migration, reception and arrival (Meeus et al., Citation2019; Nettelbladt & Boano, Citation2019). The following section lays out the theoretical framework of the article, consisting of an overview on how the concept of infrastructure is taken up within urban migration studies and how differential access to infrastructures can be understood. The next two sections give a short introduction to the methods employed in the research and the reception and accommodation of asylum seekers in Augsburg. The empirical sections are structured according to the three subsets of arrival infrastructures found to be of relevance to interviewees, namely infrastructures of information, infrastructures for language learning and infrastructures for social connection. The conclusion identifies three main contributions of the article, namely its focus on the relationality between urban arrival infrastructures and asylum accommodation and on the accessibility and ambiguity of urban arrival infrastructures.

Accessing arrival infrastructures: opportunities for familiarization?

This paper addresses the relationality between asylum accommodation, conceived as part of “infrastructures of reception”, and “urban arrival infrastructures". The paper thereby builds on geographical thought recognizing that spaces are not homogeneous entities, but a product of interrelations with other spaces and times (Massey, Citation2005). In order to illustrate how differences in the accessibility of urban arrival infrastructures shape asylum seekers’ sense of familiarity with a reception location during arrival, the first subsection brings together scholarship on infrastructures as it has been taken up within urban geography more generally and in migration studies more specifically. The second subsection further conceptualizes the accessibility of urban arrival infrastructures.

The infrastructures of arrival

Arrival in a reception location and the subsequent period of applying for asylum is often characterized by waiting and uncertainty until a decision on an asylum application has been made (Hess & Johanna, Citation2017; Hinger & Schäfer, Citation2019; Weidinger et al., Citation2021). Although waiting is often associated with boredom and passivity (Conlon, Citation2011), other studies found that the period of applying for asylum is also an active period during which familiarization with the reception location and its residents takes place (Brun, Citation2015). Being or feeling familiar or unfamiliar with someone or someplace describes a relation characterized by closeness or distance and is acquired through both knowledge and experience (Szytniewski & Spierings, Citation2014). Everyday encounters with known and unknown others in public and semi-public spaces can also create a sense of public familiarity which Blokland and Nast (Citation2014) link to a sense of belonging. Therefore, acquiring a sense of familiarity with the reception location and its residents is a result of both individual agency and the socio-material infrastructures of a city.

Within urban geography, infrastructure has become a popular concept through which to theorize and analyse cities, as it “decentre(s) certain prevailing units of analyses in existing studies to foreground other actants” (Ho, Citation2022, p. 1255). More than just physical elements, infrastructures are understood to be made up of both social and technical elements and inherently political and power-laden (Larkin, Citation2013; Schwanen & Nixon, Citation2019). An example of one kind of urban infrastructure are social infrastructures, conceived by (Latham & Layton, Citation2019) “the networks of spaces, facilities, institutions, and groups that create affordances for social connection”. Viewing the period of asylum through the lens of infrastructure makes visible how specific configurations of social and technical elements shape experiences of asylum seekers, as well as their future trajectories.

Star (Citation1999, p. 381f) outlines several characteristics of “infrastructures": First, infrastructures are embedded “into and inside of other structures, social arrangements, and technologies”. Second, infrastructures have a certain reach or scope, they are not one time but recurring events. Third, infrastructures are “learned as part of membership”, meaning that new members first have to familiarize themselves with its usage. Fourth, infrastructures are “built on an installed base”, from which they obtain both strengths and limitations. Lastly, infrastructures “become visible upon breakdown”, meaning that infrastructures usually function without being noticed, but become visible when they stop working. Moreover, Star (Citation1999, p. 380) highlights that infrastructure “is a fundamentally relational concept, becoming real infrastructure in relation to organized practices”. In other words, the properties of infrastructures emerge only in interaction between “people and things", they are hence not inherent to the things themselves but depend on the human element for their functioning.

Meeus et al. (Citation2019, p. 1) conceptualize arrival infrastructures as “those parts of the urban fabric within which newcomers become entangled on arrival, and where their future local or translocal social mobilities are produced as much as negotiated”. In contrast to “migration” and “humanitarian” infrastructures which focus on factors that shape the mobility of migrants or related governance mechanisms (Pascucci, Citation2017; Xiang & Lindquist, Citation2014), the concept of arrival infrastructures shifts more attention to the material and immaterial elements of urban areas that enable newcomers to “arrive” and settle in a specific place, even if only for a temporary period (Kox & Van Liempt, Citation2022; Miellet, Citation2022). Arrival infrastructures are highly ambiguous, meaning that there is an inherent tension between state-provided, municipal and grassroots provided infrastructures (Felder et al., Citation2020; Gill, Citation2018). Although state-provided asylum accommodation can be considered a part of arrival infrastructures as asylum seekers “become entangled” within these upon arrival, this paper refers to asylum accommodation as “infrastructures of reception” in order to better illustrate the inherent ambiguity of arrival infrastructures as well as the extent of their embeddedness within the urban (Nettelbladt & Boano, Citation2019).

Combining the more general characteristics of infrastructures outlined by Star (Citation1999) with the more recent thinking on arrival infrastructures delivers an understanding of arrival infrastructures as embedded within the urban and its “structures, social arrangements and technologies". Viewing arrival infrastructures as embedded in the urban draws attention to the points where they intersect, which material or immaterial elements of urban infrastructures become part of asylum seekers’ arrival infrastructures. Building on Amin and Thrift (Citation2017, p. 4), arrival infrastructures are viewed “from the inside out […] because cities work from the ground up”. As arrival infrastructures are embedded in urban infrastructures, they are similarly political and socially selective, granting access to some, and limiting access of others (Amin, Citation2014). Consequently, the next subsection discusses factors that mediate asylum seekers’ access to urban arrival infrastructures.

Accessing arrival infrastructures

In many European countries, asylum seekers and to some extent refugees often have little choice in reception location due to national dispersal policies, making it paramount to understand how differences between reception locations influence asylum seekers’ experiences of reception, their access to justice and their future trajectories (Burridge & Gill, Citation2017; van Liempt & Miellet, Citation2021). As outlined in the introduction, studying the relation between urban areas and forced migrants makes it possible to focus not solely on the containment and exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in camps and camp-like spaces, but to analyse how spaces of reception and camp spaces are produced in and through urban spaces. In other words, the urban is now used as an analytical framework to understand geographies of asylum (Darling, Citation2021; Kreichauf & Glorius, Citation2021).

This article builds on work interrogating the spatial relations and disconnections between asylum accommodation and urban arrival infrastructures to understand how uneven geographies of asylum create differences in asylum seekers’ access to opportunities and resources (Hanhörster & Wessendorf, Citation2020; Nettelbladt & Boano, Citation2019). In their analysis of asylum seekers’ access to justice and legal aid, Burridge and Gill (Citation2017) demonstrate how “uneven geographies of asylum” contribute to asylum seekers’ experiences of precarity and marginalization. The authors argue for a spatial understanding of precarity which addresses differences between reception locations, but also how individuals are “differentially exposed” to precarity based on their socio-legal status. To better comprehend how arrival infrastructures are accessible to some and not to others, it is hence necessary to consider accessibility from the perspective of the individual and how asylum seekers are differentially positioned towards infrastructures through their subjectivity in terms of legal status, gender, age or ethnicity (Schultz, Citation2020).

According to Tonkiss (Citation2013), infrastructures always imply the question of accessibility, as “urban inequalities are expressed in differential access to infrastructural systems and goods”. The ambiguity of arrival infrastructures makes it necessary to identify who or what is part of it and who it excludes. Accessibility as a concept is historically linked to discussions on the relation between transportation, mobility and social exclusion and is often equated with spatial proximity or distance to transportation opportunities (Cass et al., Citation2005; Lucas, Citation2012). Farrington and Farrington (Citation2005) define accessibility as “the ability of people to reach and engage in opportunities and activities”, arguing that the spatial dimension of the concept is a starting point for understanding the occurrence of injustice or inequality. In this sense, the accessibility of arrival infrastructures can be understood not simply as the spatial distance between asylum accommodation and urban arrival infrastructures, but as asylum seekers’ ability to reach and engage with these infrastructures.

The accessibility of arrival infrastructures is defined in this paper as three types of constraints, borrowing its terminology from time geography (Hägerstrand, Citation1970). Hägerstrand defined three types of constraints, capability constraints, authority constraints and coupling constraints, which in this paper are referred to as personal (capability), institutional (authority) and spatial (coupling) constraints. Capability or capacity constraints refer to an individual’s physiological and mental restrictions, such as eating or sleeping. Authority or steering constraints refer to relations of power in a society, that is, the institutional and societal context consisting of laws, regulations and norms. The concept of coupling constraints is fundamental to time geography, as these “stem from people’s opportunities and the need to couple and de-couple” (Ellegård, Citation2018, p. 44). In other words, coupling constraints “define where, when, and for how long, the individual has to join other individuals, tools, and materials in order to produce, consume, and transact” (Hägerstrand, Citation1970, p. 14), meaning that individuals can only be in one place at a time, thereby limiting their options of being in other places during that time period. The next section gives a brief overview of the methods employed in this research.

Methods

The aim of this paper is to understand asylum seekers’ everyday experiences of differential access to arrival infrastructures in an urban reception context and how this influences the process of familiarization. The data was collected by the author of this paper as part of her PhD research which compared two different cases of asylum seeker accommodation and how differences in spatial, material and institutional open- or closedness influenced familiarization between asylum seekers and local residents (Zill, Citation2022). The research was conducted between September 2016 and November 2017 in Augsburg, Germany, following a comparative case study approach and combining several ethnographic methods, namely participant observation, semi-structured and walk-along interviews. This approach helped compare and contrast between spatial, material and institutional characteristics of urban asylum seeker accommodation and how these shaped asylum seekers’ perceptions and experiences of both asylum seeker accommodation and urban arrival infrastructures.

The research opted for a heterogeneous sample in terms of age, gender, legal status, country of origin and length of residence in the asylum centre to allow for a range of experiences and opinions regarding access and barriers to urban arrival infrastructures (see ). Asylum seekers in the first case study were recruited by directly approaching them in the semi-public spaces of the house, while only few were recruited through snowballing or gatekeepers. Due to its more closed character, asylum seekers living in the second case study were recruited mostly through gatekeepers, which were members of the neighbourhood support group or via a fellow asylum seeker. Although differences in participant recruitment may affect the sample of interviewees, this effect was partially compensated for by participating in a homework tutoring class taking place in the second case study as this facilitated additional contacts with several families residing in the centre.

Table 1. Overview Respondents GHC and GUO.

Thirty semi-structured interviews with asylum seekers were conducted, five of which as walk-along interviews in (semi)-public spaces of the city. Rather than pre-determining which material or immaterial aspects of arrival infrastructures were of relevance to asylum seekers, the semi-structured approach of the interviews allowed for new insights to emerge in a bottom-up manner. The interviews with asylum seekers took place in a setting of their choice, which was often their room or a nearby café. The majority of interviews were conducted in either English or German, a translator was used only in a few cases, reflecting the fact that many residents had already lived in Germany centre for at least a year, in some cases for several years and were therefore relatively fluent in German. For some interviewees, taking part in the interview was also an opportunity to practice speaking German. Quotes in the results section are marked either with “O” meaning “original” and are taken from interviews conducted in English, while quotes marked with “T” are translated from German. After gaining consent from participants, all interviews were recorded, transcribed and anonymized, all names of asylum seekers in this paper are pseudonyms. Interviews were analysed together with observations in MAXQDA.

Paying close attention to questions of research ethics and positionality is paramount when conducting research with asylum seekers and refugees. All research participants, including asylum seekers, were informed about the content and goals of the project at the beginning of research, before the actual interviews took place. In addition, the extended presence of the researcher in both research locations enabled potential research participants to ask questions about the research and helped establish a higher degree of trust between researcher and participants. In order to minimize potential harm, no questions were asked about the migration experience itself. In cases where participants shared difficult experiences that occurred after arrival in Germany, they did so on their own accord as they expressed that they wanted their experience to be publicly known. In order to further ensure research participants’ anonymity, all personally identifying characteristics were removed, including the location and names of the two asylum centres where the research was undertaken, as these are not central to understanding the results of this paper. The author sought to “give back” wherever possible, for instance by helping with translations, providing homework tutoring or helping participants in their informational needs.

To recognize and reflect on questions of positionality and their implications on research process and findings, this research adopted a practice of critical reflexivity (Rose, Citation1997), which was facilitated by the use of a field diary. Several asylum seekers of the first case study perceived the author to be one of the volunteers working in the centre, being not only from the area, being a young, white woman of German nationality. This contributed to initial distrust between the author and potential research participants, as some asylum seekers resident in the centre were distrustful of the volunteers present, believing that over-involvement with volunteers would impact their chances on asylum (see also Zill, Citation2022). While the more “socially closed” character of the second case study made it more difficult to establish contact with resident asylum seekers, its social closedness made me more visible as a person “from the outside” and brought more attention to my positionality as a researcher. The differences in positionality both between the two case studies, as well as over time reflect the insight that a researcher’s positionality does not remain stable, but shifts with each research encounter and setting (Rose, Citation1997).

Seeking asylum in Germany, arriving in Augsburg

Claims to asylum are processed on national level by the federal office of migration and refugees (BAMF); individuals arriving in Germany seeking to apply for asylum are directed to a local branch of the BAMF. After their application for asylum has been registered, asylum seekers are dispersed to a first reception facility in one of the sixteen federal states where they receive a so-called “certificate of arrival” with their personal data (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, Citation2021). Until 2018, asylum seekers were dispersed to a second reception facility after a mandatory stay in a first reception facility of about three months. Since 2018, first reception and secondary accommodation are combined in so-called “ANKER” facilities, which seek to accelerate procedures and increase efficiency in the “voluntary” return and deportation of migrants (Münch, Citation2022). The dispersal of asylum seekers follows a quota system, the “Königssteiner Schlüssel”, based on the number of inhabitants of the state and its tax revenues. While the national government is responsible for granting asylum, the sixteen federal states are tasked with the reception and accommodation of asylum seekers. The federal level is characterized by a high variability in reception practices, as federal states operate different federal policies, support structures and minimum accommodation standards (Wendel, Citation2014; Hess & Johanna, Citation2017).

Living conditions of asylum seekers in Germany have progressively worsened since the 1980s, as political measures had been taken which aimed at the deterrence of asylum seekers by reducing their living standards. The “Asylum Seekers Benefits Act” (ASBA) of 1993 further restricted benefits asylum seekers receive as well as introduced benefits in kind, such as housing, clothing or food, in addition to the denial of working permits, residential obligations, the safe-third-country principle and the mandatory stay in collective accommodation facilities. These measures effectively separated asylum seekers from the rest of the population in terms of welfare (Müller, Citation2010). During the late 2000s, asylum accommodation located more frequently in inner-city and residential areas instead of very isolated areas, creating a higher visibility of asylum seekers (Hinger, Citation2016). The separation of asylum seekers from accessing welfare benefits through the ASBA has effectively laid the groundwork for current mechanisms of socio-spatial control and exclusion observable in current practices of asylum accommodation.

Until 2015, asylum seekers were barred from accessing integration measures; only individuals who were granted a refugee status had access to state-provided language and integration courses as well as to forms of employment. Since 2015, the so-called “asylum procedure acceleration act” (APAA) created a categorical division between asylum seekers with a “good prospect of staying” and those with “poor prospects of staying”, based on the likelihood of being granted asylum. Those with good prospects were granted early access to integration schemes and the labor market, while asylum procedures and deportations were accelerated for those with poor prospects (Schultz, Citation2020). While the terms for integration are still controlled on a national level, the role of municipalities in Germany regarding the integration of asylum seekers and recognized refugees has become more pronounced in recent decades (Bommes, Citation2018). Passing the APAA in 2015 gave municipalities more financial leeway, as some state-provided integration measures such as integration and language courses are now made accessible to those asylum seekers with good prospects of staying. While the integration of asylum seekers was often treated in a pragmatic and unofficial manner, municipalities are now officially required to play an active role in the integration of asylum seekers and recognized refugees (Aumüller, Citation2018).

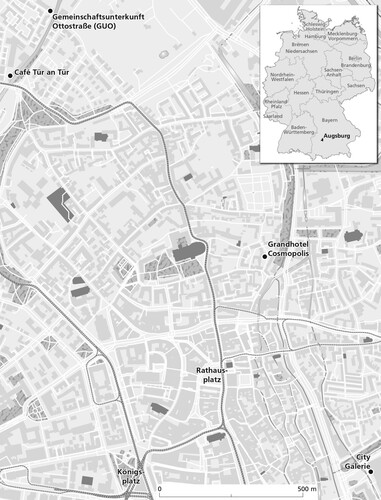

The location of this case study is Augsburg, a middle-sized city in of nearly 300.000 inhabitants in the federal state of Bavaria, South Germany. Up to 1256 asylum seekers are accommodated in Augsburg in three types of temporary collective accommodation, consisting of 12 state-administered collective asylum centers (Ger. “Gemeinschaftsunterkunft” or “GU”), 38 municipal decentralized housing units with no more than 50 asylum seekers each and several facilities for unaccompanied minors. In 2018, the majority of asylum-seeking persons in Augsburg came from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria and Somalia; about 65% of these were registered as male, 35% as female (Stadt Augsburg, Citation2019). Two collective asylum centers were selected as case studies for this research, which were both located in the inner-city of Augsburg (see ).

Figure 1. Map of the inner-city of Augsburg, including the location of the two case studies and several public and semi-public spaces mentioned by interviewees.

The first case study, the Grandhotel Cosmopolis (GHC), is an experimental form of asylum seeker accommodation combining housing for asylum seekers, hotel rooms for tourists, a restaurant, café and event spaces. Located in a former elderly care home, it opened its doors in 2012 and is the longest-running project of its kind (Grandhotel Cosmopolis, Citation2019). It offers space for 56 asylum seekers and has 12 hotel and 10 hostel rooms (Grandhotel Cosmopolis, Citation2018). The case study was selected based on the uniqueness of its concept, as it offers the possibility to study the effects of higher degrees of spatial, material and institutional openness on familiarization (Zill et all., Citation2020). The second case study, the “Gemeinschaftsunterkunft Ottostraße” (GUO), is a state-run asylum center located in a former manufacturing plant and was selected for its different material and institutional dimensions, accommodating about twice the number of inhabitants as the GHC. The researcher opted for a comparative case study located in the same city in order to minimize the contextual differences (Zill et al., Citation2021).

Arrival infrastructures: providing opportunities for information, language learning and social connection

The following three subsections depict how asylum seekers experienced urban reception locations and how these contrasted with their experiences of more rural reception locations. Three subsets of urban arrival infrastructures emerged which captured interviewees’ experiences of urban asylum, namely informational, language-learning and social infrastructures. The findings illustrate not only how personal, institutional and spatial constraints limited asylum seekers’ access to these infrastructures, but also demonstrate asylum seekers’ and local residents’ agency in obtaining and facilitating access, thereby revealing the contested nature of asylum seekers’ arrival.

Infrastructures for information

Being able to access information regarding legal services, education, health or employment is crucial for establishing a sense of familiarity with the local context and its residents during the period of arrival (Hanhörster & Wessendorf, Citation2020). More, access to information on legal services may be a decisive factor on the outcome of an application to asylum (Burridge & Gill, Citation2017). An important source of localized information are social networks, which are considered an integral part of any migration experience (Strang & Ager, Citation2010). A consequential difference between asylum seekers and other types of migrants is that in many European countries asylum seekers and to some extent recognized refugees have limited choice regarding their residential location. Although the principle of family reunification is still upheld in most European countries, meaning that asylum seekers can apply for housing close to or with family members, those without family ties are dispersed on a no-choice basis to locations in which they have few pre-existing social contacts (van Liempt & Miellet, Citation2021). Consequentially, dispersal policies deny asylum seekers access to information through already existing ties to family, friends or migrant communities, thereby increasing the importance of building new localized social networks in their dispersal location and securing the means to digital connectivity (Adam et al., Citation2019).

Interviews with research participants reflected the importance of access to information via social networks, as well as how the spatial location of accommodation in an urban or rural setting facilitates or withholds access to information. Several research participants compared their accommodation experiences of more urban and more rural locations. Overall, respondents agreed that access to information via social networks proved challenging in very remote locations, as it increased their dependency on volunteers or acquaintances. The remoteness of accommodation proved especially challenging for single travelling female asylum seekers, such as Nur, a woman in her mid-thirties. She recounted how she had been dispersed to a small, privately run asylum center located in a village of only a couple hundred inhabitants. Being cut off from access to migration services including translators, she became dependent on a man that exploited and abused her in exchange for help:

The difference between [my current accommodation] and the previous asylum centre is unbelievable, because, once, in [my home country], I watched a documentary about Guantanamo, and I found this image in [this village]. I thought, okay, this is Europe, Germany and there are human rights here, but in [this village], it was so horrible, it was like a prison, a strong prison. […] I was the only woman there. […] When I first came, I didn’t know the language, so I couldn’t organize my own affairs, I needed people that knew my language and eventually I found a man [from my home country], he helped me a few times, but demanded that I sleep with him in return. (Nur, T)

Comparing their experiences with between more rural and more urban locations, respondents highlighted how being accommodated in urban areas meant not only greater proximity to important institutions and public services such as the foreigners’ office, social services, but also to volunteers, social welfare employees and non-governmental refugee organizations with close ties to the centres they were accommodated in. Respondents such as Abrik explained that while it was initially difficult to know where to find help, information soon “came to them” through volunteers and social workers with close ties to the centre. An example of information provided by volunteers is a map of the area showing shopping facilities and services nearby (see Supplementary material).

If you just walk on the street, talk to nobody, you won’t receive any information. But there, information came to us. And I met many people there that have continued to help me up to this day. […] Some refugees say, it’s great, we get help, others say, we don’t get enough information. C’mon, people, if you don’t ask, then you won’t get information. Just ask. (Abrik, T)

Access to information was not only determined by the spatial and social proximity of accommodation to diverse social networks, but also by its spatial proximity and technical linkages to digital infrastructures. In contrast to countries such as the Netherlands, a right to internet access within reception facilities is not included in German asylum policy. Instead, the ASBA specifies that asylum seekers are to receive about thirty-five Euros per month for the purpose of digital communication. In practice, this is not sufficient, as it only allows for expensive mobile data packages and cannot replace access to high-speed internet (Biselli, Citation2015; Bayerischer Flüchtlingsrat, Citation2021).

As is common for asylum accommodation in the federal state of Bavaria, internet was not provided for in the two asylum centres part of this study. Instead, volunteers and non-governmental refugee organizations financed and built the technical infrastructure to provide the two centres with wireless and cable internet access. While initially the district administration was against internet provision, as this would set a centre apart from others in the area, the district administration ultimately permitted this “informal” provision of internet under the condition that the district administration did not have to pay for the expenses of installing the digital infrastructure in the building. Volunteers and non-governmental refugee organizations of both case studies depended upon their ability to negotiate with municipal and district governments and thereby circumvent state-mandated institutional constraints in order to provide internet in both centres. This reflects how in the context of urban asylum, local state-actors and municipalities do not simply enact state policies, but often have considerable leeway in developing “pragmatic” solutions for the reception of forced migrants (Kreichauf & Mayer, Citation2021).

Given asylum seekers’ constraints in accessing the internet within asylum accommodation, free wireless internet provision in public and semi-public spaces of the city became a vital part of asylum seekers’ access to digital infrastructures. Public places and squares such as “Königsplatz” and semi-public places such as fast-food restaurants or shopping malls in Augsburg that offered free internet were mentioned by several respondents as places they regularly went to in order “to connect” (see ). Simultaneously however, asylum seekers’ visibility in public and semi-public places also exposed asylum seekers to the danger of police controls, as the following quote by Amadou from Senegal shows:

Because [the shopping mall] is really nice, there is a square, it has Wifi. You can connect, watch youtube or go there with friends. But Königsplatz or Rathausplatz I don’t like so much, there are many broken people, they behave like shit. And sometimes you are controlled by the police, I don’t like that. (Amadou, T)

Infrastructures for language learning

Despite the importance of language proficiency for future employment and integration (Hou & Beiser, Citation2006), access to formal language training in Germany, also known as “integration classes", is restricted to recognized refugees and asylum seekers with a high likelihood of being granted refugee status (Schultz, Citation2020). Among the thirty interviewees, less than half attended an official integration course, the other half came from countries that were not considered to have a good “prospect of staying”, such as Afghanistan, Nigeria or Senegal, and were therefore not granted permission to attend an integration course. In addition, several of these interviewees had their application to asylum rejected and were living in Germany with an insecure status. Isaad, a young Afghan man in his early twenties, reflected on his experience of being an unaccompanied minor accommodated in a town close to Augsburg. Being barred from accessing state-provided language courses, he wanted to attend informal language classes offered in Augsburg, but eventually lost interest as his limited allowance was not enough to cover transportation costs, forcing him to walk to Augsburg in order to attend classes:

Three years after [arrival] I couldn't really speak German, because I didn't have much contact to Germans. I was always with the other Afghan guys. Now you're allowed to attend a German course, but back then that wasn't the case. […] I first met Germans in Café Tür an Tür. They offered a German course, not very long, one month or so, once or twice a week. We didn't have a bike or a ticket [for public transportation] so we lost interest in attending the course … We wanted to take the streetcar but we didn't want to risk getting fined, so we had to get up very early and walk all the way, it took us one and a half hours. (Isaad, T)

In contrast to Isaad’s experience, most interviewees living in the two urban asylum centres that were part of this research had taken or were at the time of research taking a language course offered by a non-profit organization. Moussa, a Senegalese man in his mid-twenties, had received a negative decision on his asylum application, yet continued attending informal language courses as he considered this his only opportunity to learn German:

When I came to Germany, only here I learned German, in Tür an Tür. But one and a half hours is not enough. In other schools, courses are four or eight hours. […] I come [to the café] when I have homework to do, every Wednesday I come here at three, there are people that help with homework, good people. (Moussa, T)

Personal constraints such as care obligations also influenced female asylum seekers’ ability to access language courses, often intersecting with legal status and country of origin. Similar to findings by Bernhard and Bernhard (Citation2022), unmarried, female interviewees without care obligations were more likely to attend a German course and often had a larger social network through forms of voluntary work or religious activities and a higher language proficiency than female married interviewees with care obligations. Female asylum seekers’ constraints in accessing language courses illustrate the gendered nature of arrival infrastructures, as already demonstrated by Nur’s experience in the previous subsection. The gendered nature of language learning infrastructures also highlights that a sole focus on differences between urban or rural reception locations is not enough to explain to what extent individual, especially female, asylum seekers have access to the resources and opportunities necessary during arrival. The differences between female asylum seekers in accessing infrastructures for information and language learning stress that there is no single, gendered experience, but that gendered access to infrastructures always intersects with other dimensions of an positionality.

The findings also highlighted how urban semi-public spaces, such as language cafés and informal settings, become part of asylum seekers’ infrastructures for language learning.

Several interviewees experienced difficulties in making contact with locals in open public spaces due to previously experienced prejudice. For a majority of interviewees, attending a language course was in itself not sufficient to feel comfortable communicating in German in everyday settings, as their fear of making mistakes or being misunderstood made them hesitant in approaching people. In order to overcome the fear of making mistakes and feel comfortable speaking German, many interviewees emphasized the importance of semi-public spaces in which they could practice German in an informal manner. Especially since 2015, language cafés and other informal settings have been created by citizens, non-governmental institutions and charities across Germany (Neis et al., Citation2018). Miremba, a Ugandan woman in her late twenties, described how volunteering in the café of the local refugee NGO “Tür an Tür” not only helped to improve her language skills, but also helped her expand her social network:

In “Tür an Tür”, I made friends there, and I was actually one of the people who helped with, volunteered, the first time they open up the café, they needed people to serve and it was nice, yeah, having made a language course there also, I got to know fellow students, also the teachers, so yeah, I got to know some, quite a lot of people. (Miremba, O)

Infrastructures for social connection

A third integral aspect of asylum seekers’ experiences of urban in contrast to more rural asylum accommodation was the greater accessibility of different types of social infrastructures. Interviewees like Ikemba, a Nigerian man in his thirties, recounted his experience of being accommodated in a more rural reception location with fewer public spaces to go to. Not only did he feel inhibited in his movement, but also observed by others:

In small town, it’s very very different, because you don’t move very well, if you have to move, you don’t see anybody around, everywhere it’s quiet, you understand, so you feel somehow, or you go to the garden, like the park, you sit down there, they start looking everywhere, you know most times, there are some old people, they look at you, just be looking at you, wow, I say they are cameras (laughs). (Ikemba, O)

In contrast to Ikema’s experience of hypervisiblity in a rural reception location, Fred from Kongo explained how Augsburg’s commercial spaces were spaces where he could blended in with the crowd and by being able to “see many people” temporarily escape the boredom of the asylum centre:

When it’s cold, I go there, go inside and watch people. Just watch people. Sometimes in the weekend there are lots of people in City Galerie. I’m bored at home, I want to see people, I go there. I go to city Galerie, Saturday, when I see many people, that feels like – I like that.

(Fred, T)

When I have a lot of stress, I go to the city, when I see people, going for a walk, my stress will be less … but if you are there where everybody is in their house, you don’t see anyone, just woods or corn or so … it’s too boring. But in the city, when you can’t do anything, you can go to the cinema, you can go to a quiet café, you can do many things. (Mamadou, T)

In the city, you can just go anywhere, you can make a friend. (Abeke, O)

Sometimes I go out to Königsplatz, I love to sit there and talk to friends. At least with time, everything is getting better, no? It’s like a meeting point, completely in the center of the town. So, you meet there, you can discuss, you feel free there, you feel free in Königsplatz or City Galerie. […] Because … each time I want to think about the situation of life, if I go there I will see people passing, see some kind of people playing, then I will feel at home. I say wow, this is nice, then your thoughts will come out from where you think you know, you have to focus on what you are seeing. (Abeke, O)

Conclusion

This paper argues that asylum seekers’ sense of arrival and familiarity with a reception location depends on not only on the availability, but perhaps more importantly on the accessibility of urban arrival infrastructures. Based on thirty interviews with asylum seekers living in two inner-city asylum centres in Augsburg, Germany, the paper identifies three subsets of urban arrival infrastructures crucial to familiarizing with a reception location, namely infrastructures of information, infrastructures for language learning and infrastructures for social connection. The interviews revealed how urban public and semi-public spaces form integral parts of asylum seekers’ informational, language learning and social infrastructures, providing access to opportunities and resources for familiarization. For instance, free internet in public squares helped circumvent restrictions in internet access and provided opportunities to form social connections and share information, thereby mediating the effects of spatially isolating national dispersal policies. Access to these informational, language learning and social infrastructures contributed to a temporary sense of freedom and belonging and created opportunities to temporarily overcome the boredom and restrictions experienced in asylum accommodation.

The article makes three main contributions. First, it highlights the relationality between asylum accommodation and urban arrival infrastructures, arguing that asylum accommodation is produced through its connection and disconnection with socio-material infrastructures of the city. The article thereby builds on scholarship analysing the relationship between forced migrants and urban spaces (Darling, Citation2017; Meeus et al., Citation2019), showcasing how asylum seekers’ sense of arrival and familiarity is both “policed” and “politicized” in and through urban spaces through their ability to access to urban arrival infrastructures. By identifying and comparing three different subsets of urban arrival infrastructures within one paper, namely infrastructures for information, language learning and social connection, the article illustrates how arrival infrastructures are often not exclusive to arrival but are visibly and invisibly embedded within other urban infrastructures.

Second, by focusing on the accessibility of urban arrival infrastructures, the article conceptualizes asylum seekers’ experiences of socio-spatial exclusion not as an inherent characteristic of asylum accommodation, but as conditional upon asylum seekers’ differential access to urban arrival infrastructures, with differential access being an outcome of intersecting spatial, institutional and personal constraints. The article thereby builds on and extends scholarship revealing the “unevenness" of geographies of asylum (Burridge & Gill, Citation2017), with differences in asylum seekers’ marginalization being not simply a result of differences between reception locations or socio-legal status, but also a result of their differential positioning towards urban arrival infrastructures due to differences in gender, age or ethnicity.

Third, the paper also illuminates the inherent ambiguity and political nature of urban arrival infrastructures. By providing access to resources otherwise denied by state policy such as free internet, volunteers and NGOs challenged dominant conceptions and policies of arrival, highlighting the need for digital connectivity for asylum seekers (Gill, Citation2018; Mayblin & James, Citation2019). Urban arrival infrastructures are inherently ambiguous as state-provided, formal infrastructures often did not support but undermine the process of arrival, thereby contributing to asylum seekers’ differential inclusion (Cuttitta, Citation2016). The tensions between the provisions of formal and informal, citizen-provided infrastructures also demonstrated the increased importance of and reliance upon informal infrastructures during periods of uncertainty.

While it is too simple to reduce the ambiguity within arrival infrastructures to state versus non-state actors, the disconnections between asylum accommodation and urban arrival infrastructures do reveal different conceptions of what constitutes arrival. These different conceptions are a product of European and national deterrence policies resulting in everyday bordering processes and revolve around the questions of who is permitted to arrive (Yuval-Davis et al., Citation2018). The ambiguity and disconnection between state-provided reception and urban arrival infrastructures is symptomatic for policies of deterrence which seek to make the period of arrival appear as unattractive as possible in order to further deter asylum seekers from remaining in the host country (Dempsey, Citation2020; Nettelbladt & Boano, Citation2019). Deterrence policies which are targeting asylum seekers that are already in the country hence work against the potential future integration of asylum seekers by depriving them of the means necessary to “arrive”.

In summary, asylum seekers can only make use of the opportunities provided by urban arrival infrastructures if these are accessible to them. Future research could further explore the socio-economic and political consequences of an increased reliance on informally provided urban arrival infrastructures, as well as the potential of local migration policies to address the needs of diverse types of migrants through urban arrival infrastructures.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all those who gave their time and insight to the research on which this paper is based. The author would also like to thank all anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive feedback. The paper also greatly benefitted from the intellectual support and insight of Ilse van Liempt, Bas Spierings and Pieter Hooimeijer. The research would not have been possible without the support of the Grandhotel Cosmopolis e.V., UnterstützerInnenkreis Ottostraβe and Tür an Tür e.V. Augsburg.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, Francesca, Föbker, Stefanie, Imani, Daniela, Pfaffenbach, Carmella, Weiss, Günther, & Wiegandt, Claus Christian. (2019). Social contacts and networks of refugees in the arrival context - manifestations in a large city and in selected small and medium-sized towns. Erdkunde, 73(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2019.01.02

- Amin, Ash. (2008). Collective culture and urban public space. City, 12(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810801933495

- Amin, Ash. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7-8), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490

- Amin, Ash, & Thrift, Nigel. (2017). Seeing like a city (1st ed.). Polity Press.

- Aumüller, Jutta. (2018). Die kommunale integration von flüchtlingen. In Handbuch lokale integrationspolitik. Springer VS.

- Bayerischer Flüchtlingsrat. (2021). “W-Lan in Bayerischen Unterkünften.” Retrieved December 7, 2021 (https://www.fluechtlingsrat-bayern.de/w-lan-in-bayerischen-unterkuenften/).

- Bernhard, Sarah, & Bernhard, Stefan. (2022). Gender differences in second language proficiency—evidence from recent humanitarian migrants in Germany. Journal of Refugee Studies, feab038. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab038

- Biselli, Anna. (2015). “Internet Für asylsuchende: Warum dieses wichtige werkzeug Der selbstbestimmung meist verwehrt bleibt.” Netzpolitik.Org. Retrieved December 7, 2021 (https://netzpolitik.org/2015/internet-fuer-asylsuchende-warum-dieses-wichtige-werkzeug-der-selbstbestimmung-meist-verwehrt-bleibt/#comments).

- Blokland, Talja, & Nast, Julia. (2014). From public familiarity to comfort zone: The relevance of absent ties for belonging in Berlin's mixed neighbourhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1142–1159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12126

- Bommes, Michael. (2018). Die rolle Der kommunen in Der bundesdeutschen integrations- Und migrationspolitik. In Handbuch lokale integrationspolitik. Springer VS.

- Brun, Cathrine. (2015). Active waiting and changing hopes toward a time perspective on protracted displacement. Social Analysis, 59(1), 19–37. doi: 10.3167/sa.2015.590102

- Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (2021). “Ankunft Und Registrierung.” Retrieved January 25, 2022 (https://www.bamf.de/DE/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylverfahrens/AnkunftRegistrierung/ankunftregistrierung-node.html).

- Burridge, Andrew, & Gill, Nick. (2017). Conveyor-Belt justice: Precarity, access to justice, and uneven geographies of legal Aid in UK asylum appeals. Antipode, 49(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12258

- Cancellieri, Adriano, & Ostanel, Elena. (2015). The struggle for public space. City, 19(4), 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1051740

- Cass, Noel, Shove, Elizabeth, & Urry, John. (2005). Social exclusion, mobility and access. The Sociological Review, 53(3), 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00565.x

- Conlon, Deirdre. (2011). Waiting: Feminist perspectives on the spacings/timings of migrant (Im)Mobility. Gender, Place & Culture, 18(3), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.566320

- Cuttitta, Paolo. (2016). Mandatory integration measures and differential inclusion: The Italian case. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(1), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0410-0

- Darling, Jonathan. (2011). Domopolitics, governmentality and the regulation of asylum accommodation. Political Geography, 30(5), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.04.011

- Darling, Jonathan. (2013). Moral urbanism, asylum, and the politics of critique. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(8), 1785–1801. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45441

- Darling, Jonathan. (2017). Forced migration and the city. Progress in Human Geography, 41(2), 178–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516629004

- Darling, Jonathan. (2021). Refugee urbanism: seeing asylum “like a city”. Urban Geography, 894–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1763611

- Dempsey, Kara E. (2020). Spaces of violence: A typology of the political geography of violence against migrants seeking asylum in the EU. Political Geography, 79, 102157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102157

- Ellegård, Kajsa. (2018). Time geography. Routledge.

- Farrington, John, & Farrington, Conor. (2005). Rural accessibility, social inclusion and social justice: Towards conceptualisation. Journal of Transport Geography, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2004.10.002

- Felder, Maxime, Stavo-Debauge, Joan, Pattaroni, Luca, Trossat, Marie, & Drevon, Guillaume. (2020). Between hospitality and inhospitality: The janus-faced 'Arrival infrastructure'. Urban Planning, 5(3), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2941

- Freedman, Jane, Kivilcim, Zeynep, & Baklacıoğlu, Nurcan Özgür. (2017). A gendered approach to the Syrian refugee crisis (1st ed). Routledge.

- Gill, Nick. (2018). The suppression of welcome. Fennia - International Journal of Geography, 196(1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.70040

- Grandhotel Cosmopolis. (2018). “Konzept | Grandhotel Cosmopolis AugsburgGrandhotel Cosmopolis Augsburg.” Retrieved July 2, 2018 (https://grandhotel-cosmopolis.org/de/konzept/).

- Grandhotel Cosmopolis. (2019). “Pressearchiv.” Retrieved June 11, 2019 (https://grandhotel-cosmopolis.org/de/category/presse/).

- Hägerstrand, Torsten. (1970). What about people in regional science? Papers of the regional science association, 16.

- Hanhörster, Heike, & Wessendorf, Susanne. (2020). The role of arrival areas for migrant integration and resource access. Urban Planning, 5(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2891

- Hess, Sabine, & Johanna, Elle. (2017). Leben Jenseits von Mindeststandards. Dokumentation Zur Situation von Gemeinschaftsunterkünften in Niedersachsen. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen.

- Hinger, Sophie. (2016). Asylum in Germany: The making of the ‘crisis’ and the role of civil society. Human Geography, 9(2), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861600900208

- Hinger, Sophie, & Schäfer, Philipp. (2019). Making a difference – The accommodation of refugees in Leipzig and osnabrück. Erdkunde, 73(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2019.01.06

- Ho, Elaine Lynn-Ee. (2022). Social geography II: Space and sociality. Progress in Human Geography, 46(5), 1252–1260. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221103601

- Hou, Feng, & Beiser, Morton. (2006). Learning the language of a new country: A ten-year study of English acquisition by south-east Asian refugees in Canada. International Migration, 44(1), 135–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2006.00358.x

- Kox, Mieke, & Van Liempt, Ilse. (2022). “I have to start All over again.” The role of institutional and personal arrival infrastructures in refugees’ home-making processes in Amsterdam. Comparative Population Studies, https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2022-07

- Kreichauf, René, & Glorius, Birgit. (2021). Introduction: Displacement, asylum and the city – theoretical approaches and empirical findings. Urban Geography, 42(7), 869–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1978220

- Kreichauf, René, & Mayer, Margit. (2021). Negotiating urban solidarities: Multiple agencies and contested meanings in the making of solidarity cities. Urban Geography, 979–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1890953

- Larkin, Brian. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Latham, Alan, & Layton, Jack. (2019). Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces. Geography Compass, 13(7), e12444. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12444

- Lucas, Karen. (2012). Transport and social exclusion: Where Are We Now? Transport Policy, 20, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.01.013

- Massey, Doreen. (2005). For space. Sage.

- Mayblin, Lucy, & James, Poppy. (2019). Asylum and refugee support in the UK: Civil society filling the gaps? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(3), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1466695

- Meeus, Bruno, Arnaut, Karel, & Heur, Bas van (eds.). (2019). Arrival infrastructures. Migration and urban social mobilities. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Miellet, Sara. (2022). From refugee to resident in the digital Age: Refugees’ strategies for navigating in and negotiating beyond uncertainty during reception and settlement in The Netherlands. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(4), 3629–3646. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab063

- Müller, Doreen. (2010). Flucht Und asyl in europäischen migrationsregimen: Metamorphosen einer umkämpften kategorie Am beispiel Der EU, Deutschlands Und Polens. Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Münch, Sybille. (2022). Creating uncertainty in the governance of arrival and return: Target-group constructions in bavarian AnkER facilities. Journal of Refugee Studies, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab104

- Neis, Hans Joachim, Meier, Briana, & Furukawazono, Tomoki. (2018). Welcome city: Refugees in three German cities. Urban Planning, 3(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v3i4.1668

- Nettelbladt, Gala, & Boano, Camillo. (2019). Infrastructures of reception: The spatial politics of refuge in mannheim, Germany. Political Geography, 71, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.02.007

- Pascucci, Elisa. (2017). The humanitarian infrastructure and the question of over-research: Reflections on fieldwork in the refugee crises in the Middle East and north Africa. Area, 49(2), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12312

- Rose, Gillian. (1997). Situating knowledges: Positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography, 21(3), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913297673302122

- Sanyal, Romola. (2012). Refugees and the city: An urban discussion. Geography Compass, 6(11), 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12010

- Schultz, Caroline. (2020). A prospect of staying? Differentiated access to integration for asylum seekers in Germany. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(7), 1246–1264. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1640376

- Schwanen, Tim, & Nixon, Denver V. (2019). Urban infrastructures: Four tensions and their effects. In Handbook of Urban Geography (pp. 147–162). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. (2021). Ritornello: “People as infrastructure”. Urban Geography, 1341–1348. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1894397

- Simsek-Caglar, Ayse, & Schiller, Nina Glick. (2018). Migrants and city-making: Multiscalar perspectives on dispossession. Duke University Press.

- Squire, Vicki, & Darling, Jonathan. (2013). The “minor” politics of rightful presence: Justice and relationality in city of sanctuary. International Political Sociology, 7(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12009

- Stadt Augsburg. (2019). “Asyl in Augsburg. Zahlen Und Fakten.” Retrieved May 17, 2019 (https://www.augsburg.de/umwelt-soziales/asyl-in-augsburg/zahlen-fakten/).

- Star, Susan Leigh. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist.

- Strang, A., & Ager, Alastair. (2010). Refugee integration: Emerging trends and remaining agendas. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23(4), 589–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq046

- Szytniewski, Bianca, & Spierings, Bas. (2014). Encounters with otherness: Implications of (un)familiarity for daily life in borderlands. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 29(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2014.938971

- Tonkiss, Fran. (2013). Cities by design. The social life of urban form. Polity Press.

- van Liempt, Ilse, & Miellet, Sara. (2021). Being far away from what you need: The impact of dispersal on resettled refugees’ homemaking and place attachment in small to medium-sized towns in The Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(11), 2377–2395. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1845130

- Weidinger, Tobias, Kordel, Stefan, & Kieslinger, Julia. (2021). Unravelling the meaning of place and spatial mobility: Analysing the everyday life-worlds of refugees in host societies by means of mobility mapping. Journal of Refugee Studies, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez004

- Wendel, Kay. (2014). Unterbringung von flüchtlingen in deutschland: Regelungen Und praxis Der bundesländer Im vergleich. am Main.

- Xiang, Biao, & Lindquist, Johan. (2014). Migration infrastructure. International Migration Review, 48(1_suppl), 122–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12141

- Yuval-Davis, Nira, Wemyss, Georgie, & Cassidy, Kathryn. (2018). Everyday bordering, belonging and the reorientation of British immigration legislation. Sociology, 52(2), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517702599

- Zill, M. O. (2022). Familiar strangers, distant neighbours: How the openness of asylum accommodation influences familiarization between asylum seekers and local residents [Doctoral thesis, Utrecht University]. Utrecht. https://doi.org/10.33540/1482

- Zill, M. O., van Liempt, I., & Spierings, B. (2021). Living in a ‘free jail': Asylum seekers' and local residents’ experiences of discomfort with asylum seeker accommodation. Political Geography, 91, 102487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102487

- Zill, M. O., van Liempt, I. C., Spierings, B., & Hooimeijer, P. (2020). Uneven geographies of asylum accommodation: Conceptualizing the impact of spatial, material, and institutional differences on (un)familiarity between asylum seekers and local residents. Migration Studies, 8(4), 491–509. http://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mny049