ABSTRACT

The “where” of urban geography as a discipline, and Urban Geography as a journal, has changed significantly over the last 40 years. Here, we take a quantitative and qualitative look at this history. We find, unsurprisingly, some articles about African cities in the journal before 2010, and a notable and ongoing uptick since. Drawing on debates over how southern cities ought to be studied, we identify different framings and lines of argumentation. Some authors frame their case in reference to theories derived primarily from global northern cities, while others focus their literature review on regional scholarship. Some push against, and some seek to advance, universal understandings of what a city is, and ought to be. We reflect on positive changes as well as where we collectively might head as the field and journal continue working to make sense of how to theorize, and where to theorize from.

This is an introduction to a virtual collection on African cities and urban geography, which can be accessed at https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/rurb20/collections/African_cities_in_conversation.

What is the relationship between African cities and urban geography (both the sub-discipline and the journal)? For as long as African cities have been studied, there has been a fraught relationship with the orthodox canon of urban thought. Earlier works on African cities were often written through the lens of development, published in conversation with other literatures (Robinson, Citation2006). Where they entered urban studies, African cities were often framed as exceptions, not sites to theorize from, with their residents and built form described as not-quite-urban (Lawhon et al., Citation2020a). Many have emphatically argued that we ought not simply import and apply ideas generated primarily from northern cities (e.g. Sheppard et al., Citation2013), but Robinson’s (Citation2006) compelling, foundational work usefully and provocatively insists that we both place African cities within urban studies and think with them to contribute to urban theory. How exactly this is to be done, and with what outcomes, remains the subject of debate (Lawhon & Truelove, Citation2020).

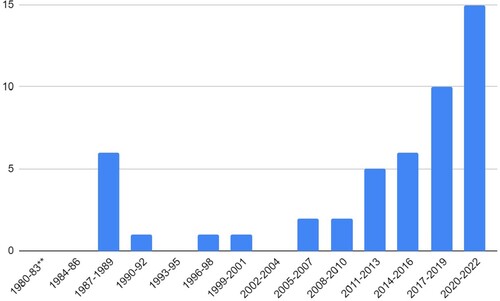

In this context, for this virtual collection, we first collected all articles focused on African cities in Urban Geography (see ). Looking through the title, abstract and keywords from the journal’s first volume in 1980 until the 43rd (2022), we found 49 articles, as well as a number of Urban Pulse pieces and shorter commentaries. What is surely most apparent in is the growing inclusion, a point recognized by Guma and Monstadt (Citation2021, p. 4) who note, “Southern cities in general, and African cities in particular are beginning to gain more traction”. We find this positive and exciting, responding to the broad thrust of Robinson’s (Citation2006) call.

Figure 1. Number of articles per 3 year cluster*. (*The total number of papers in the journal per year has grown, so the percentage of content about African cities has grown less quickly than this figure implies. **To divide 43 more easily, we have made this first unit 4 years.)

Beyond this, it is rather less clear what should be done with such a collection of articles. Some might oppose separating them out in the first place, and the implication that they are a natural set. Alternatively, a regionalist geographical approach might attempt to find commonalities and themes, working towards a clearer understanding of the (imperfect, constructed) category “African cities” and how it has changed over time.Footnote1 Yet doing so is not quite in the spirit of putting African cities into conversation with the broader field of urban geography.

Instead, we use these papers as a lens through which to consider how authors writing about African cities engage with the geography of urban geography. Focusing primarily on conceptual argument (exemplified in the literature review and framing of different articles), we asked: what is the geography of the theory being used to frame data from African cities? Where is the imagined point of departure and comparison? What is the geography of the theories being reviewed, critiqued and advanced? Who do the authors suggest their audience is, and thus who should be learning what from African cities?

Unsurprisingly, we find various versions of this task and, to a lesser extent, some shift in how this is done. Below, we work through what might be loosely conceptualized as a spectrum from exceptionalism to a cosmopolitan global urban theory (see Lawhon & Truelove, Citation2020). Our intention here is not so much to categorize, quantify and evaluate this; useful as such a project would be, it goes beyond the thrust of a Collection. Instead, we work to show difference, and draw our collective attention explicitly to the implications and possibilities associated with various approaches, urging more collective reflection on such questions. Our articles, then, are not a set of what we authoritatively deem “the best” works, but a set of papers purposely selected to highlight these differences.

We also have a slightly more pragmatic intention: to point the reader (and reviewers!) to the diversity of ways of successfully framing cases (at least, where success is defined by getting published!). Our hope is that making these choices explicit might enable potential authors (as well as reviewers and editors) to reflect on these different strategies, and for more scholars to successfully publish about African cities in Urban Geography.

From exceptionalism to global urban theory?

African cities have long been positioned as not-quite properly urban and/or not well-explained by canonical urban theory. This position is clear in the provocative 1989 piece “West African urbanization: Where Tolley’s model fails” (Kilbourne & Berry, Citation1989). Setting aside the model itself and focusing instead on the style of argument: perhaps ironically, given the title, the authors of this piece suggest that, with some tweaks, Tolley’s model does still have useful predictive power in explaining/analyzing urbanization in a few West African countries. In response, Fox (Citation1989) insists: the assumption that African urban patterns can be usefully read through “economic” theories of markets and capitalism is flawed. “Kilbourne and Berry’s paper seems to have been only marginally affected by their reading of African literature and their experience of African reality” (p. 499). Engagement with the African context is seen to matter here, and “urban theory” only can make sense if put into conversation with broader literature about the place where it is to be applied.

Taking a different approach but continuing to (implicitly) frame (South) African cities as somehow different, are the five articles in the 1988 special issue on South Africa.Footnote2 All do have literature reviews – but nearly all (sometimes, all, e.g. Pirie, Citation1988) of the literature cited is South African. Where scholarship writing about other places is mentioned, it is cited in a very broad way. Hart, for example, includes a single paragraph with four citations from what might be considered “mainstream international” urban theory to frame debates over the relative significance of economic and political analyzes. She then suggests that, in contrast to this other literature, her study “underscores the role of the South African state as the prime motor of geographical change” (Citation1988, p. 619).

The question of the extent to which “mainstream” urban theories can and should be usefully applied to African cities, and what kinds of theory can be generated from African cities, continues to be relevant – at times implicit, at times explicit – over subsequent decades of writing in the journal. Some later pieces frame their contribution in regional terms, not directly engaging with literature from outside Africa. Page and Sunjo (Citation2018), for example, focus on West African urban literature in their review of middle class housing. Similarly, Asante and Helbrecht (Citation2019) place their argument in the context of work on African urban regeneration, focusing in particular on scholarship about Ghana. These works do not explicitly say that African cities are different or that theories from elsewhere are inapplicable, but leave open the question of how their arguments relate to other geographies. Notably, this writing style parallels much writing about the United States and Europe: literature and concepts are drawn from nearby, similar cities, and the implications for “elsewhere” are rarely considered.

While individual works developing insights from the U.S. and Europe often do not consider the implications for other places, scholars writing about African cities have often applied and stretched ideas from very different places southwards. (It is much less common for scholars to take ideas developed from African cases and stretch them northwards, although see Myers, Citation2014.) Authors may well emphasize the need to consider African cities, but in contrast to Page and Sunjo (Citation2018) and Asante and Helbrecht (Citation2019), work to make more established urban theory apply. Kutz and Lenhardt (Citation2016), for example, note that existing theory is “provincial” and that there is a need to “decenter” existing accounts, challenging the ability of scholars to narrate a “global crisis” from scholarship on northern cities. Here, they suggest the need to “make it [urban theory] more applicable” (Citation2016, p. 926). They then provide an overview of literature rooted very much in northern urban political economy. By “rescaling” the theory with experiences of the 2007–2008 financial crisis in Tangier, Morocco, Kutz and Lenhardt (Citation2016) suggest we might come to a more complete understanding of global phenomenon, one that provincializes and supplements – but does not otherwise challenge – existing explanation.

In contrast, other papers directly take on the geography of theory and suggest that writing from African cities may require different theorizations (cf Sheppard et al., Citation2013). Drawing across a wider geography is Gillespie’s (Citation2017) work on quiet encroachment. Here, we find a paper that explicitly starts with what is characterized as a conceptualization from the south: quiet encroachment. His work is both an affirmation and advancement of the idea, pushing forward theory through considering the politics of encroachment in a multi-party democracy. Like many other studies of informality more generally, the paper draws on scholarship beyond Africa, yet roots arguments in reference primarily to their significance for southern cities (see Roy, Citation2009).

Finally, a more capacious argument – one that questions the relevance of theory beyond the south – can be found in two of our selected papers. Alda-Vidal et al. (Citation2018, p. 3) place their work within “the emergence and consolidation of decentered perspectives that seek to destabilize the application of northern norms across urban theory in order to better explain the dynamics of cities across a variety of contexts.” Through what they term as a “process-based analysis” they highlight how the practices of formal water operators in Lilongwe exacerbate existing water inequalities. They suggest that paying attention to everyday practices on infrastructures in cities in the margins helps decenter global frameworks. The exact “variety of contexts” to which their argument applies, however, is not entirely clear: in their conclusion, the authors seek to consider their work in relation to African cities and “the majority world”. Yet they seem to leave open the possibility that their analysis of “the normality of disruptions in urban infrastructure” might tell us something about how infrastructure works in the global north too (Citation2018, p. 117).

Taking this style of analysis a step further, Parnell and Robinson (Citation2012) argue against simply deploying the term “neoliberalism” to African cities, instead insisting on considering diverse urban processes that should be taken seriously in their own right. The insights they draw from South Africa are, importantly, not argued to have relevance just for African or southern cities, but instead are framed as insights into international urban processes. While this paper does not quite show the relevance of this argument for the global north (reasonably; one paper can only do so much), later work exemplifies that the limits of neoliberal explanation apply elsewhere (see Robinson et al., Citation2022 for ongoing development on this argument). Both Alda-Vidal et al. and Parnell and Robinson insist that what is happening in African cities ought not to be treated as unique instances, but as grounds for theoretical reflections. Neither set of authors are quite ready to propose grand alternative theorizations, instead cautiously attending to difference, building up data and analysis towards alternative accounts.

What are we to make of this list and our selection? To note again, the clearest pattern is an uptick in the number of papers about African cities in Urban Geography. Beyond this, there is also a stronger push to theorize from African cities. How, exactly, this engagement happens varies, and it is surely reasonable enough to find variance: some literatures and concepts are more relevant to African cities, and some are more or less relevant in particular parts of particular African cities. And some might well have relevance far beyond African cities. New concepts were less apparent, but framed as something to work towards through slow and careful analysis.

Reflecting on this wider collection, however, it still seems hard to know whether to situate work within the old canon and stretch existing terms and ideas, insist on a more inclusive canon, or write from an emergent southern one. It is also hard to know what kinds of reviews each author has to respond to in order to publish their work. In this context, we have sought to attend to different ways that authors have approached such uncertainties not so much to resolve them, but to help us collectively reflect on this moment of plurality and uncertainty within the scholarship.

Perhaps a virtual collection might end here, with this set of observations about our past. Yet, nudged a little by Urban Geography’s editor, we also take this opportunity to reflect a little towards the near-term and longer future (see also Lawhon et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Our hope is that pointing out geographies of literature reviews and argumentation might provide authors, reviewers and editors with a range of examples that enable greater success of submissions about urban Africa. Change in the academic context can be slow, yet it is crucial that we recognize it! Despite positive change, there is, quite simply, still a need to know more about the diversity of African cities. Our hopes, however, are not just about a quantitative uptick; they are also about how we understand and theorize. We are optimistic about the possibilities associated with the shift from thinking about African cities as “exceptions” (that might require tweaking established theory to make it relevant) to thinking about African cities as “sites from which to theorize”.

We do appreciate the caution in recent publications about African cities that do not overstretch the significance of findings that point to the possibilities of broader considerations without making universalizing claims. Plenty of problems have come from generalizing too quickly, too widely and insisting on the relevance of “here” to “there”. Perhaps, though, we are in a moment where authors might be permitted (by themselves as well as reviewers and editors) to push a little further. Perhaps Urban Geography might be a place where authors can more confidently submit work that examines African cities not only to understand the continent but to theorize in ways that shape how we think about urban places, processes and politics more generally. But it cannot be the job of scholars writing about African cities to think through their wider significance alone. Perhaps, too, Urban Geography could be a place where more authors writing about other cities are permitted (by themselves as well as reviewers and editors) – encouraged, even – to engage more deeply with scholarship about Africa and be inspired to think through the significance of theorization generated from writing about African cities for elsewhere.

Notes

1 Or note that 22 of these focused on South African cities, including a special issue in 1988 and 8 of the first 9 papers about African cities in the journal. North Africa is nearly absent, with the exception of Tangier, examined in Kutz and Lenhardt (Citation2016), and a perhaps surprising absence of studies of Cairo.

2 A brief look at the titles suggests that there is something wrong with these cities: the focus of analysis includes underdevelopment, constraint, conflict, segregation, manipulation, razing, resistance, and violence. Surely, we agree that these are relevant considerations for apartheid urbanism, but it is also telling about the way that African cities were first written about in the journal.

References

- Alda-Vidal, C., Kooy, M., & Rusca, M. (2018). Mapping operation and maintenance: An everyday urbanism analysis of inequalities within piped water supply in Lilongwe, Malawi. Urban Geography, 39(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1292664

- Asante, L. A., & Helbrecht, I. (2019). Changing urban governance in Ghana: The role of resistance practices and activism in Kumasi. Urban Geography, 40(10), 1568–1595. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1631109

- Fox, R. (1989). West African urbanization: A reassessment. Urban Geography, 10(5), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.10.5.495

- Gillespie, T. (2017). From quiet to bold encroachment: Contesting dispossession in Accra’s informal sector. Urban Geography, 38(7), 974–992. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1191792

- Guma, P. K., & Monstadt, J. (2021). Smart city making? The spread of ICT-driven plans and infrastructures in Nairobi. Urban Geography, 42(3), 360–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1715050

- Hart, D. M. (1988). Political manipulation of urban space: The razing of district six, Cape Town. Urban Geography, 9(6), 603–628. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.9.6.603

- Kilbourne, B. J., & Berry, B. J. L. (1989). West African urbanization: Where Tolley’s model fails. Urban Geography, 10(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.10.1.1

- Kutz, W., & Lenhardt, J. (2016). “Where to put the spare cash?” Subprime urbanization and the geographies of the financial crisis in the Global South. Urban Geography, 37(6), 926–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1118989

- Lawhon, M., with contributions from le Roux, L., Makina, A., & Truelove, Y. (2020a). Making urban theory: Learning and unlearning through southern cities. Routledge.

- Lawhon, M., Le Roux, L., Makina, A., Nakyagaba, G. N., Singh, A., & Sseviiri, H. (2020b). Beyond southern urbanism? Imagining an urban geography of a world of cities. Urban Geography, 41(5), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1734346

- Lawhon, M., & Truelove, Y. (2020). Disambiguating the southern urban critique: Propositions, pathways and possibilities for a more global urban studies. Urban Studies, 57(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019829412

- Myers, G. (2014). From expected to unexpected comparisons: Changing the flows of ideas about cities in a postcolonial urban world. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 35(1), 104–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12046

- Page, B., & Sunjo, E. (2018). Africa’s middle class: Building houses and constructing identities in the small town of buea, Cameroon. Urban Geography, 39(1), 75–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1286839

- Parnell, S., & Robinson, J. (2012). (Re)theorizing cities from the Global South: Looking beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geography, 33(4), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.4.593

- Pirie, G. H. (1988). Housing essential service workers in Johannesburg: Locational constraint and conflict. Urban Geography, 9(6), 568–583. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.9.6.568

- Robinson, J. (2006). Ordinary cities: Between modernity and development. Routledge.

- Robinson, J., Wu, F., Harrison, P., Wang, Z., Todes, A., Dittgen, R., & Attuyer, K. (2022). Beyond variegation: The territorialisation of states, communities and developers in large-scale developments in Johannesburg, Shanghai and London. Urban Studies, 59(8), 1715–1740. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211064159

- Roy, A. (2009). The 21st-century metropolis: New geographies of theory. Regional Studies, 43(6), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701809665

- Sheppard, E., Leitner, H., & Maringanti, A. (2013). Provincializing global urbanism: A manifesto. Urban Geography, 34(7), 893–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.807977