ABSTRACT

Although the urban fabric is often associated with relevant infrastructures that foster young refugees’ experiences of settlement and future imagining, a critical notion of place remains largely absent from the literature. This paper investigates refugee youths’ urban arrival and settlement processes by examining the role of public space, place and identity in their imagination of possible future selves. We use place identity as a dynamic, translocal and contested concept to explore how future selves are emplaced in multiple and contradictory ways. The paper reports on an eight-month ethnographic study in an underprivileged neighborhood in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, that is characterized by functionalism, social housing and a high concentration of refugee arrivals. We find that personal referents of public neighborhood places are important for nurturing young refugees’ specific hardships and traumas that threaten future self-imagination. We further demonstrate how momentary belongings due to diverse yet intertwined neighborhood identities foster the emergence of multiple possible future selves. Lastly, we show how local racialized discourses of place endanger and “trap” possible future self-concepts. We conclude that urban refugee youths’ future self-imaginations develop alongside multiple contested places and temporalities, and contribute to a relational understanding of urban processes and experiences of forced mobility and displacement.

Introduction

In the heart of the Molenwijk, a densely-populated yet green high-rise neighborhood in Amsterdam, Mehmet (24) and Deniz (22), both refugees from Turkey, are hanging out in a sheltered area surrounded by dense vegetation and tall trees (see ). They sit on a bench and, whilst chatting enthusiastically, Mehmet shows Deniz the “Insta” of a female classmate he fancies. Deniz laughs and points out she is way out of Mehmet’s league. Looking down, the pavement is covered with sunflower seed hulls. They say sunflower seeds are a snack they often enjoy whilst hanging out here – not to the liking of many passers-by and neighbors, though. Mehmet says: “They say we should take our ‘rubbish’ home because this is not normal!”. When asked about life in the Molenwijk, they say that they often seek out more secluded places like this to spend time together, escape their turbulent lives and alleviate their stress. And because of the large number of neighborhood green spaces, they do not have to travel far. Although Deniz’s home is located elsewhere in the city district of Amsterdam North, he mentions he spends several days a week here. His friend Mehmet, whom he met during their concurrent stay in an asylum seeker center far away in the countryside, lives in the Molenwijk with his family. Now, they go to school together – except for today as there is no school due to the autumn break. “We’re bored man. There isn’t really much to do here, and everything’s too far away”, Mehmet says. He sighs: “You know, it’s not that I don’t like it here, it’s just that I eventually want to live somewhere else” (Informal conversation Mehmet and Deniz, 18 September 2021).

Figure 1. One of the several benches hidden away in the Molenwijk’s green areas (Photo by first author).

The above provides a brief glimpse into young refugees’ various and often understudied relations with urban residential neighborhoods. Although their movements significantly shape and are shaped by the sociospatial organization of urban spaces, it is only recently that research has started to explore the entanglements between forced migration and the uneven production of urban space (see e.g. Basu & Fiedler, Citation2017; Bose, Citation2018; Darling, Citation2021; El-Moussawi & Schuermans, Citation2021; Hamann & El-Kayed, Citation2018; Kreichauf & Glorius, Citation2021; Walton-Roberts et al., Citation2020). Due to urban developments and internal processes of marginalization, cities produce displacement that affects refugees’ lives long after their “arrival” (Bhagat, Citation2020; van Liempt & Bygnes, Citation2023). In the Netherlands, the state regulates dispersal and settlement, and refugees largely depend on social housing areas throughout the country. Although refugees remain mobile subjects throughout their settlement process (van Liempt & Bygnes, Citation2023), they also have to cope with restrictive urban sites that are characterized by the consequences of displacement, such as everyday politics of austerity and inadequate housing (Hamann & El-Kayed, Citation2018; Soederberg, Citation2018). This is problematic, as the concentration of disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in urban deprived neighborhoods with marginal public spaces may cause fragmentation and competition among its residents, which in turn can impede good conditions of life and a sense of hope for a secure and meaningful future (Madanipour, Citation2004; Phillimore & Goodson, Citation2006). Consequently, the acute and multidimensional vulnerabilities of “weaker” social groups can turn the public spaces of underprivileged neighborhoods into sites of conflict and disorder (Valentine, Citation2008).

“The spacetime of resettlement”, as Secor et al. (Citation2022, p. 2) maintain, “is itself the site of crisis”. Future thinking and potentially recognizing goals, aspirations, hopes, fears and threats are often postponed in displacement. Although migration and mobility are central to how young people experience and organize their lives (Evans, Citation2008; Hopkins, Citation2010), refugee youth experience and navigate uncertain and unpredictable futures where concrete predictions can be unattainable and deceiving (Finlay et al., Citation2022). Young refugees’ transition into adulthood are emotionally demanding due to translocal identities and relations, and multi-sited senses of belonging (Brickell & Datta, Citation2011; Evans, Citation2020). Additionally, they often cope with politicized and racialized discourses of nation and citizenship that often surface in public space (De Backer et al., Citation2023; Huizinga, Citation2022). Adolescence, nevertheless, is a key time in which future conceptualization is highly noticeable, omnipresent and relevant (Prince, Citation2014). To prevent lost or canceled futures of urban refugee youths, it is crucial to understand how they conceptualize and cognitively represent their emplaced futures and possible trajectories as urban subjects and active producers of urban space (Darling, Citation2017).

This paper contributes to this knowledge gap by focusing on the ways young refugees conceptualize and articulate their future self-concepts in-place after arrival and settlement in an underprivileged neighborhood in Amsterdam. We use Prince’s (Citation2014, p. 1) “emplaced future self-concept” as it foregrounds the inclusion of place in young people’s identity formation processes and the intersections between theories of place and possible future selves. We focus on the neighborhood, as neighborhood spaces are often a central domain of young people’s lives given the extensive amount of time they spend in such locales (Hopkins, Citation2010; Prince, Citation2014). The research further zooms in on the contested nature of public spaces since these are places where young people deal with stringent control and surveillance, but also mobilize their own identities and exert power by claiming space (e.g. Evans, Citation2008; Hopkins, Citation2010; Pain, Citation2001). Although public space is closely linked to young refugees’ experiences of inclusion/exclusion, belonging and participation (e.g. van Liempt & Staring, Citation2021; Rishbeth et al., Citation2019), it needs critical examination as intercultural interaction and encounter do not necessarily always translate into meaningful contact and belonging (Basu & Fiedler, Citation2017; Huizinga & van Hoven, Citation2018; Valentine, Citation2008).

We address the following research question: How do mutually constitutive relationships between constructions of place and identity shape the contested imaginations of the future selves of young refugees in the Molenwijk? The paper begins with a review of relevant works on the intersections of young refugees, place identities and emplaced future selves. We move on to discuss the methodological decisions made and the methods used. We then provide an in-depth socio-historic overview of the research area. This is followed by a discussion of the various patterns found in the data: personal referents of place and the nurturing of future selves; “lived” momentary belongings and emergent future selves; and racialized discourse of place and endangered future possibilities.

Emplacing young refugees’ possible future selves

Possible future selves are “the selves we imagine ourselves becoming in the future, the selves we hope to become, the selves we are afraid we may become, and the selves we fully expect we will become” (Oyserman & Fryberg, Citation2006, p. 19). Coined by Markus and Nurius (Citation1986), the concept is a socio-psychological construct to identify self-relevant cognitions of emotions, experiences, aspirations and needs used to render an idea of the person someone wants to become. Although youth issues and inequalities are central in many policy debates, young people tend to be socially constructed as future adults, lacking critical consideration of their subjectivities (Evans, Citation2008). Consequently, thinking about and voicing imagined desired future selves are both highly relevant for young people, considering the crucial and formative aspects of this period for the safe and sustainable transition to adulthood (Hopkins, Citation2010; Pain, Citation2001). Moreover, as possible future selves are socially constructed and negotiated relationally (Oyserman & Fryberg, Citation2006), it is important to understand how youths from various backgrounds envision future selves and how marginalized social identity markers are navigated in the present (see also Prince, Citation2014).

Imagining one’s future self contains an important cognitive element as well as a motivational element; understandings of future possibilities can only be produced through present behavior, and the courses of action needed to pursue relevant imaginings of one’s future self might otherwise not be known (Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016; Prince, Citation2014; Strahan & Wilson, Citation2006). Although critics point out future selves may not be “real” because they are an imaginary construct, others demonstrate that imagined future selves do have “real” everyday life consequences as these imaginations affect current identities and motivations (see e.g. Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016; Strahan & Wilson, Citation2006). Markus and Nurius (Citation1986) provide two main reasons for this. First, carving out a future self-concept is related to everyday attitudes and behaviors that adhere to the image of one’s future self. Second, the future self-concept assists individuals to interpret and evaluate views of the present self. The conceptualization of a possible future self thus functions as a blueprint for individual identity development and shapes everyday behavior that reflects desired developmental trajectories (Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016; Markus & Nurius, Citation1986; Prince, Citation2014).

Dunkel and Kerpelman (Citation2006) highlight how more positive evaluations of future selves increase young people’s self-esteem, rendering possible selves sites of both individual agency and social determination. Vice versa, young people whose ideas of possible future selves are less clear or defined, or whose imagined selves are largely disconnected from their present selves, are more likely to organize their lives accordingly (Strahan & Wilson, Citation2006; see also Hopkins, Citation2010). Thinkers on imaginative work point out that imagination “is neither purely emancipatory nor entirely disciplined but is a space of contestation” (Appadurai, Citation1996, p. 4). Consequently, as Markus and Nurius (Citation1986) stress, although individuals are in theory free to carve out possible future selves, the social and historical relations of the individual determine which particular imaginations of future selves will be overtaken by the passing of time and become irrelevant.

Carabelli and Lyon (Citation2016) note the fluid nature of future self-imagination and how various forms of future orientation may blend into one another. Strahan and Wilson (Citation2006) emphasize the relevance of temporality to understand the ways in which future selves are constantly shaped and negotiated between different times. A past self, according to Markus and Nurius (Citation1986), can become a conceptualization of a possible future self, depending on whether this past is remembered vividly (see also Strahan & Wilson, Citation2006). Strahan and Wilson (Citation2006) argue that if recalling the past self is paired with positive emotions, a perceived successful or admired past self may become an example of a desired future self. On the other hand, comparing oneself to a “supposedly inferior past self” (p. 5) may lead to a more positive self-evaluation in the present conditions.

To understand these relationalities, recent work emphasizes that youth’ ability to envision a possible future self is one that is interwoven with notions of space and place (e.g. Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016; Hopkins, Citation2010; Prince, Citation2014). To deal with insecurity, people draw parallels between the ways in which they self-identify and how they perceive place-related distinctive social and physical dimensions (Twigger-Ross & Uzzell, Citation1996). Prince (Citation2014, p. 700) therefore argues that “one cannot imagine the future without place” since the question of whom one wants to become is inherently connected to spatial features, relations and orderings. The conceptualization of possible future selves is thus necessarily partial and subjective as we make sense of who we are through where we are (Massey, Citation2005). Imaginations of future selves reflect the embodied geography and discursive actions of everyday life (Dixon & Durrheim, Citation2000). At the same time, the ability to register and cognitively process spatial information is key to carving out a future self-concept (Markus & Nurius, Citation1986). Thus, because recently arrived refugee youths have limited embodied knowledge of the city, it is difficult for them to imagine the future due to disorientation and dispossession (Finlay et al., Citation2022).

Place, then, is a critical ingredient to disentangle the developmental trajectories of young refugees and how they perceive and interpret future possibilities. Like other identities, those associated with place and localities can be better understood by appreciating the processes, relationalities and intersections associated with them (Hopkins, Citation2010). Places have multiple identities due to their ongoing connections and relations to other places (Massey, Citation2005). Place identities are shaped in relation to specific memories, present behaviors and future imaginations through translocal geographies and relations of migrants’ everyday lives (Brickell & Datta, Citation2011). Specific places or locations within the neighborhood that young people find themselves in also act as important markers of identity and sense of identification (Hopkins, Citation2010). Consequently, individuals’ daily spatial environments are essential to identify and repair a distorted sense of self, as everyday significant places fulfill various needs such as familiarity, privacy, comfort, healing and self-development (Dixon & Durrheim, Citation2000; Huizinga & van Hoven, Citation2018; van Liempt & Staring, Citation2021).

Place identity may tell us something about one’s personal identification with place, but places, such as the neighborhood, may contain and perpetuate hegemonic discourses on identity (e.g. Antonsich, Citation2010; Dixon & Durrheim, Citation2000; Paasi, Citation2001; Pinkster, Citation2016). Consequently, possible future selves are influenced by what social others want or expect a person to become (Oyserman & Fryberg, Citation2006). Hopkins (Citation2010) writes that living in a remote neighborhood that has a poor reputation due to a concentration of social housing negatively impacts the wellbeing and life opportunities of young people due to stigmatization. Damaging images associated with particular people because of place may stereotype young people as lazy, unreliable and/or welfare recipients (Bauder, Citation2001). Hopkins found that future work and education-related aspirations were lower in neighborhoods dominated by social housing. Pain (Citation2001) points out that public space is governed by adults. Consequently youth is “increasingly subject to control, regulation and surveillance” on the streets and in presumed homelike places (Pain, Citation2001, p. 165). But also territoriality tends to be stronger in disadvantaged neighborhoods and communities, where limited opportunities, restricted horizons and possibly even difficult family circumstances shape young people’s engagement with their local area (Hopkins, Citation2010).

In the context of neighborhood change, places are made sense of and produced via interactions, indicating the relational character of neighborhood identities and belongings (Pinkster, Citation2016; Williamson, Citation2016). Pinkster (Citation2016) illustrates how dominant neighborhood groups claim to belong through symbolic boundary drawing by means of everyday encounters and desirable ways of “doing the neighbourhood”. Other research illustrates how resettled young refugees often find themselves in existing racial hierarchies and local struggles over belonging (Bose, Citation2018). Such stereotypes tie in with contemporary discriminatory discourses around young refugees in the Netherlands, who are often accused of being a threat, “robbing the welfare state” or lacking aspirations (see e.g. Huizinga, Citation2022). Social processes, such as those associated with the media or neighborhood rumor, work to stereotype particular places – and the future self-thinking of people living in such communities – in negative or positive ways (Hopkins, Citation2010). Although “places have the potential to affirm a sense of place” and place belonging through positive cognitions of place, negative cognitions may lead to non-belonging, place aversion and a sense of entrapment (Prince, Citation2014, p. 699). Everyday experiences of marginalization and stigmatization, Prince concludes, can be internalized by young people and develop into a “blunted” future self-concept causing young people to organize their lives solely in the “here and now”.

Methodology

Here, we report on an ethnographic study conducted in the Molenwijk, Amsterdam, between September 2021 and April 2022. The first author collected rich ethnographic accounts of sociospatial life focused on young refugees’ everyday experiences and practices within public space. Areas of interest for observation and informal conversation were the neighborhood’s bike paths and footpaths, squares and various green areas. More semi-public spaces – such as the local library, the neighborhood community room (De Molenwijkkamer), the local fish shop, a neighborhood-based art atelier and several youth centers – were also frequented sites. The principal researcher participated on a regular basis in neighborhood activities, including “meet your neighbours” bingo sessions, “chatter time” meetings and art-based workshops. Additionally, a weekly Dutch language café for neighborhood newcomers was co-organized. During the study, some of these activities and places were inaccessible due to Covid-19. This impacted participants’ future self-thinking as school-related activities were postponed or canceled. However, most local social activity spaces remained open throughout this period due to the Molenwijk’s classification by the municipality as a “vulnerable neighbourhood” (Gemeente Amsterdam, Citation2020).

Various forms of data were collected to investigate participants’ conceptualizations of future selves related to the neighborhood and other meaningful places. The principal researcher had repeated conversations with twelve young refugees, of whom seven participated in in-depth interviews. Eleven expert interviews with various stakeholders in the neighborhood – such as the “neighbourhood fathers”, local social and artistic organizations and social workers focused on youth wellbeing – were held. The principal researcher sought out and accompanied participants to youth and community centers, sports facilities and shopping centers in the broader area of Amsterdam Noord. In total, the principal researcher spent over 170 h in the field. Field notes were written after each fieldwork day and interviews were transcribed verbatim. All the collected materials were uploaded into NVivo 12, thematically coded and analyzed with a focus on the intersections of public space, place identities and the development of future selves.

The young refugees – who appear in this paper under pseudonyms – were aged 18–32 (see ). Youth is generally defined through the chronological age range of 16–25 (e.g. Evans, Citation2008). Some participants were thus older chronologically, but can be considered youths socially as they were not adults and experienced power relations that are part of being young, such as difficulties with educational systems, negotiating restrictive households and the crucial role of public space in their everyday lives (Hopkins, Citation2010). Of the twelve refugees who participated, five were female and seven were male. They had arrived from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Somalia, Palestina, Syria and Turkey and sought asylum in the Netherlands. All were granted refugee status after spending time in asylum-seeker centers, after which they were assigned social housing in the Molenwijk. Some had arrived only recently in the neighborhood and were still exploring the urban fabric whilst taking Dutch language classes and studying for their civic integration exam. Others had been residents of the neighborhood for several years (as many as six). They either studied at university or were unemployed. All self-identified as either Christian or Muslim. Religiosity consumed a significant part of their everyday lives, but although religion was experienced differently and religious practices varied, such practices did not emerge in our investigation of public space.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants.

Amidst the remnants of urban renewal: a sociospatial history of the Molenwijk

One does not need to enter the Molenwijk to understand why participants mostly talk about their neighborhood with a certain sense of pride. Upon approaching the Molenwijk, one cannot overlook the typical high-rise flats backgrounded by early twentieth-century garden villages (see ). Both the Molenwijk and the better-known Bijlmermeer were built in the late 1960s as a response to a perceived decline in livable neighborhoods in Amsterdam. Building plans were inspired by modernist and functionalist urban planning views, representing a radical break with Amsterdam’s urban planning tradition. However, whereas in recent decades Bijlmermeer has undergone several spatial interventions due to progressive insights, the Molenwijk remains largely untouched.

Figure 2. The Molenwijk from above (Photo by Marco van Middelkoop/HH/ANP).

The segregation of living and recreation functions, and work, transport functions and other economic activities in the Molenwijk greatly impact everyday life (see and ). The abundance of green spaces and the relative quietness (motorized vehicles are not allowed in the neighborhood) were considered important features for future residents’ right to a decent life. However, this also makes the neighborhood a less lively place due to a lower perceived degree of social control and safety (Gemeente Amsterdam, Citation2020). Madanipour (Citation2004) argues that rigid designs for single-purpose spaces are often less successful in an environment where needs vary widely among different social groups. High-quality public spaces, he continues, are functional when they can be used for a variety of purposes. The presence of people at different times of day, as informal owners or guardians of the public sphere, makes the streetscape more enjoyable and safe.

Figure 3. Cars can only access the neighborhood by crossing one of the four short viaducts (photograph by first author).

Figure 4. Footpaths meander through the high-rise buildings and green areas (Photo by first author).

Some features that characterize Amsterdam as a whole are present or enlarged in the Molenwijk, whereas other features seem to have completely disappeared – if they were there in the first place. Being located on the outskirts of Amsterdam has implications for local residents’ sense of mobility and, according to a municipal survey, invokes a sense of spatial isolation (Gemeente Amsterdam, Citation2020). Unlike the city, the neighborhood has limited social and cultural infrastructures, which is crucial for arrival of newcomers (Kox & van Liempt, Citation2022), and young people as a result experience little ownership of public spaces. During fieldwork, however, residents and participants simultaneously mentioned that the remote location is also part of its identity and gives the neighborhood its distinctive feel.

The neighborhood consists of 1,417 mostly high-rise flats, of which 81% are social housing. In 2022, 3,035 residents lived in the Molenwijk. Their flats are relatively outdated compared to other social housing in the city, but due to their large surface area, they remain attractive to larger families. This is one of the reasons the social housing association tends to accommodate more refugee families compared to other social housing associations in Amsterdam. When viewed from above, the buildings are positioned to resemble the sails of a windmill (windmolen). Accordingly, all the buildings are named after popular types of Dutch windmill. Furthermore, the neighborhood’s bordering roads run along dikes. This not only seems to provide an idyllic image of the Dutch regional countryside but also gives the feeling of being inside an enclave.

The neighborhood landscape therefore reflects a distinct political story and ideology. Despite its contemporary diversity and multiple ethnic communities, the politics of belonging and moral behavior are mostly formed by the neighborhood’s original residents. When the Molenwijk was developed, certain apartment buildings were designated for “respectable” professional and intellectual groups, such as teachers, doctors and dentists. Potential candidates had to satisfy a committee if they wished to live there. Enchanted by the romantic setting of prosperity and an imaginative identity of the neighborhood, the Molenwijk was granted particular privileges in terms of autonomy, marking its territoriality by clear neighborhood boundaries. The original residents remain proud of this and are most active in local neighborhood initiatives, decide what is on the agenda and often maintain and control close relationships with social workers or local government officials.

In recent decades, ageing and migration have transformed the demography of the neighborhood, thereby impacting residents’ attitudes toward living with differences. The neighborhood has a layered history of immigration, which has led to a highly diversified population, featuring many ethnicities, languages and religions (Gemeente Amsterdam, Citation2020). Moroccan and Turkish labor migrants found housing in the Molenwijk in the 1970s, whilst more recent newcomers from, for example, Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan were settled in the neighborhood as refugees. Local and regional understandings of the neighborhood are highly polarized between a romanticized, dreamy and idyllic neighborhood on the one hand and an image of decline, poverty and criminality on the other (Gemeente Amsterdam, Citation2020).

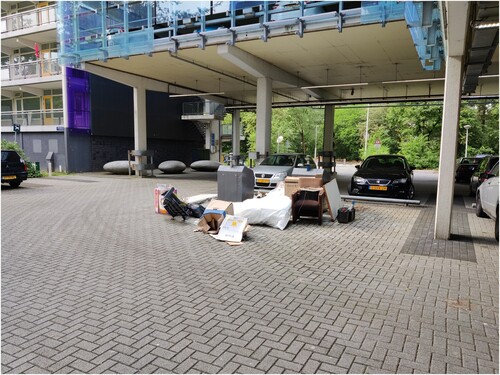

Several neighborhood residents pointed out the lack of maintenance and the neglect of public neighborhood spaces. Paths are uneven and muddy; during the autumn and winter, footpaths and bike paths are difficult to traverse. Oftentimes, the neighborhood is littered with rubbish. Between the high-rise buildings the wind has a free hand and plastic bags, boxes and other materials are scattered throughout the neighborhood (see ). The voluntary “cleaning team” mentioned that residents throw rubbish and food scraps from their balconies, attracting the rats and gulls that plague the neighborhood. Amsterdam’s municipal government has made available extra funds to renovate the neighborhood’s physical and social infrastructures. Bike paths and footpaths, for example, have been renewed and the facades, balconies and interior spaces of the flats renovated or cleaned. The brochure rack in the local library revealed an array of initiatives to reach local, vulnerable groups such as children, young people and older adults.

Figure 5. One of the several places where rubbish and litter accumulates in the Molenwijk (photo by first author).

Young refugees and the “translocal organisation” of everyday life

Refugee youths in the Molenwijk experience and identify with the neighborhood in different ways based on various everyday life patterns, activities and relations. All mentioned living quite turbulent lives. Some had part-time jobs in the delivery sector or as translators for social organizations, while others pursued hobbies, such as calligraphy, dancing, running or boxing. Most, however, were fully immersed in extensive educational programs, ranging from university or professional education for those who had been in the Netherlands for a longer period of time, to Dutch language classes for those who had just arrived. Work, school and internships, however, were mostly located in other city districts. To arrive on time, then, most had long commutes due to the unfavorable positioning of the neighborhood and poor connections with the public transport system.

Participants were involved in all sorts of activities and performed various roles and identities in the family that are typical for young people (see also Hopkins, Citation2010). Participants frequently talked about an obligation to accompany their parents to formal meetings or appointments, such as their GP, the housing association, the municipality or the immigration office. Older brothers or sisters performed care duties within their families, as they collected siblings from school or played with them in one of the neighborhood’s many playgrounds. Although the young people said they were happy to do this, they were confused about their new role in the family and the way it changed family dynamics. These practices were generally considered pleasant and meaningful, but participants talked about the importance of escaping their crowded households and going out with friends to the local shopping mall or hanging out in other spaces to avoid social control (Pain, Citation2001).

Everyday life in the Molenwijk was thus quite different from how social life was perceived and organized prior to migration. Migration and settlement through asylum was never part of imagining a future self. Now, translocal identities and relations were very much present in everyday life post-migration. Participants were regularly in contact with friends and family in other parts of the world through social media or phone conversations. These connections had a significant impact on their everyday lives, as they introduced additional emotional complexity and work. Intisad (27) explained:

Sometimes I don’t want to see anybody. I don’t know, I realise now that homesickness is really affecting my life here. What’s hard for me is that I often hear from my friend, my best friend in Syria, that the situation for people there is so difficult. That’s really intense for me to hear. (Intisad, 27)

Analyzing these intertwined geographies and relations, three dimensions of place identity surfaced most clearly in young refugees’ imaginations of possible future selves. A mixture of meaningful personal and social referents were deployed by participants to construct their identities in-place. Here, we first illustrate how personal referents of place are meaningful elements of participants’ place identities to process trauma and hardships and to nurture conceptualizations of possible future selves. Second, we show that place identities shape and are shaped through momentary belongings between participants and residents, enabling young refugees to carve out emergent future selves. Third, we pinpoint dominant, racialized discourses of place and identities in the Molenwijk and connect this to the development of an endangered perception of the present and a blunted future self-image.

Personal referents of place and future self-care

First, we zoom in on the personal relationships that participants maintain with the local, physical environment and how these relationships affect the imagination of future possibilities. In a settlement phase mainly typified by mobility restrictions (see van Liempt & Bygnes, Citation2023), a pattern emerged from the data that highlights the local, physical aspects that characterize the Molenwijk and set it apart from other neighborhoods in Amsterdam. The fieldwork emphasizes the relative peacefulness in neighborhood public spaces and the abundance of green spaces in which to sit, hang out or exercise, and how these referents of place feed into participants’ place identities and imaginations of future selves.

Despite the multiple and sometimes contradictory dimensions of place identities that were brought up, most of the refugee youths mentioned feeling a strong emotional bond with the neighborhood. These affective ties were mostly related to the characteristic physical features and thus what Twigger-Ross and Uzzell (Citation1996) call the “place-related distinctiveness” of the Molenwijk. Many young refugees experienced difficulties in self-understanding in the post-migration and post-arrival context due to the blurry overlap between past and present identities and the limited knowledge they had about future opportunities in the Netherlands. These insights resemble Prince’s (Citation2014) argument that “mobility capital lacking” young people tend to face more difficulties imagining the future. The salient and evident physical elements of the neighborhood, then, were often used by participants to derive stable self-definitions from place because of their distinctiveness. Alaa (19), who had been living in the Molenwijk for a bit over two years, talked about his connections to the neighborhood:

It’s like a home to me. I’m proud that I live here in the Molenwijk. And when someone asks me “where do you live?”, then I say with pride “I live in the Molenwijk”. And to be honest, I was in several neighbourhoods, and this neighbourhood looks and feels different. Even if I move away in the future, it’s simply a part of me. It will be there for the rest of my life. I’m not going to forget. (Alaa, 19)

What often surfaced as more concrete sites of self-identification with the neighborhood were its green and often secluded spaces, and the capacities of these spaces to nurture future selves. Among a range of urban actors, Darling (Citation2021, p. 909) for example fleshes out a “desire for stillness and stability in the turbulent conditions of being made mobile by dispersal”. Many participants had to perform various translocal identities in everyday life, and were often living together in crowded households, suffering from multiple stressors and anxieties. Intisad (27) explained why she often goes for a walk in the neighborhood:

If I’m missing my country, then I have trouble to stay at home. I sometimes have difficulty to express my feelings. So yeah, it is intense to stay inside with my family. Thus I just go outside for a walk. Not to forget or anything, but to give myself and my brain a little rest. Yes. Just to accept that my feelings are like that. That this is normal every now and then, to have these feelings […] otherwise it will be difficult with my sort of life. I need to rest. And to stop overthinking things. I have this every now and then. But a walk here in the park helps to stop this process and to get some rest. (Intisad, 27)

The examples provided here by Alaa and Intisad are part of a more complex and multilayered relationship to place that Paasi (Citation2001, p. 25) terms a “cumulative archive of personal spatial experience”. This archive is important as these self-defining memory structures are, according to Prince (Citation2014), the “building blocks” of how individuals make sense of information, based on which future possible selves can be carved out. Moreover, although the configuration of green areas in the Molenwijk was already in place, these places were imbued with new place experiences and thus meanings by the participants. By referring to their places in the Molenwijk with specific identifying features and by using the neighborhood through their specific practices, the young refugees partially transformed the neighborhood place into an identity marker in itself, triggering new discourses of home and belonging. Consequently, such practices allow them to create and maintain coherent imaginations of self and develop fertile conditions and motivational resources to navigate the present and pursue imaginations of a desired self (Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016; Dixon & Durrheim, Citation2000). As a result, the identified similarities between participants’ selves and place – at least in that moment – provided a stable ground on which to nurture conceptualizations of possible selves.

Momentary belongings and emergent future selves

Place identities and participants’ ideas of possible future selves are shaped and made sense of through social life in the neighborhood. Local place identities are in part constructed relationally through social interactions and encounters in neighborhood places and influence the emotional bond individuals maintain with their local environment. The data illustrate how social contact with local residents from other ethnic backgrounds helped the young refugees to obtain and process information to understand how future selves are conceptualized relationally between different contexts. This in turn sparked feelings of momentary belonging to the Molenwijk due to shared commonalities and identity features. Additionally, these encounters enabled and empowered young refugees to carve out elements of possible future selves that they considered relevant.

For the youths in our study, fleeting encounters with neighborhood residents in the Molenwijk’s public areas were considered meaningful opportunities to self-identify with the neighborhood and carve out future options. In summer, the distinct layout of the apartment blocks and neighborhood fabric provided important spaces for encounters. Since the neighborhood is criss-crossed by bike paths and footpaths, encounters with other people were quite common as residents were almost bound to run into each other. The local library and shopping mall were also seen as places where they not only received practical and emotional forms of care and comfort but also could engage in conversation with others about opportunities for development that they could not access through formal channels. Such unplanned, routine encounters proved meaningful, at least momentarily, as was exemplified by Nadera:

Sometimes you just know someone from the Molenwijkkamer, for example. And sometimes someone just knows my mother or my family. I don’t know the woman, but she just knows my mother. And because of this she recognises me. And then we have a short conversation. We talk about a lot of different things to help me. (Nadera, 29)

A related pattern not only illustrates the importance of fleeting encounters and momentary belongings in cognitively identifying possible future selves, but also highlights the crucial role of cultural diversity in the Molenwijk. Encounters with difference might make diversity more visible but also “commonplace”, as residents learn how to live with it through accumulated moments of interaction with others (Wessendorf, Citation2014). Although this may overcome prejudices and encourage feelings of home and belonging (Peterson, Citation2020; Valentine, Citation2008), it may also grant access to symbolic mobilities such as the accumulation of social capital (Williamson, Citation2016). For many participants, the multilayered demographics specific to the Molenwijk thus offer a dynamic context in which young refugees can situate themselves. Alaa explained:

It’s a mix here, from everywhere. I know people from Syria, Turkey, Romania and India. From everywhere. I met so many people […] it’s easier to make contact here I think. But if they’re good friends remains to be seen. It’s more that you see familiar faces the whole time […] I also learned a lot from various people. I learned from multiple cultures in the Molenwijk. And this for me is very important to grow. (Alaa, 19)

A racialized discourse of place and endangered future possibilities

Place lastly influenced young refugees’ identities in the Molenwijk as they are confronted with hegemonic ideals of place, namely dominant place identities of the Molenwijk, which shape and are shaped by place-related discursive actions and political dimensions (Dixon & Durrheim, Citation2000). In addition to a more positive emphasis on migration and diversity as a fundamental part of the Molenwijk, discrimination and racism are simultaneously part of the same neighborhood (see also Pinkster, Citation2016). Places are relationally produced, meaning that the politics of a place are constantly questioned and contested, which may end up in a competition as to how lives and relationships in the Molenwijk are to be organized. The data show that young refugees have to navigate the complexities of existing sociospatial inequalities in sites of everyday diversity, and avoid jeopardizing future possibilities.

Many neighborhood experts and residents mentioned the perceived impoverishment and decline of the neighborhood in recent decades and its impact on living with difference. Local youth social workers observed that information services around schooling and work often do not reach youths and parents in the neighborhood, as initiative organizers tend to avoid the Molenwijk. Other issues concerned the outdated state of the apartment buildings and facilities, as well as the poor condition and maintenance of public spaces. Throughout the fieldwork, it became clear that these physical realities of the neighborhood also take on symbolic meanings. They fold into persistent prejudices and stereotypes that stretch further than the neighborhood and invade participants’ everyday lives in various ways. Neighborhood representations (e.g. at the time of the fieldwork, the Molenwijk was the setting for a movie on “Moroccan mobsters”) reinforced intersections of migrant identities and criminality, which established tensions between the Molenwijk and surrounding areas. Alyaa explained:

The language coach visits us in the evening. But first she didn’t want to come because of what she heard. She comes by car and she asked my mother if my brother can walk with her to the car in the parking garage. She was scared. She didn’t want to be alone in the parking garage. She doesn’t live in the Molenwijk, but 30 minutes away. (Alyaa, 21)

Discriminatory and racialized neighborhood representations were also found among groups of residents themselves, particularly in racialized narratives shared by the original residents. During neighborhood activities, racist remarks were not uncommon in conversations about the “right” ways of “doing the neighbourhood” (Pinkster, Citation2016). The migration histories and the diversification of the neighborhood were often termed as problematic and seen as a cause of its deplorable and poorly maintained conditions. Informal conversations with mostly older residents revealed that many felt that the neighborhood’s public spaces had been transformed as “new” groups of residents used and claimed space through “other” everyday practices (Bose Citation2018; Madanipour, Citation2004). The large-scale presence of rats, for example, was often connected to “newcomers” by referring to their food practices and how they dispose of their waste. But participants’ clothing styles and religious practices and routines were also sometimes problematized, which visibly impacted some young people’s experience of safety and security in public space. The group that consider themselves the first “Molenwijkers” therefore played a disruptive role in the place identity narratives of participants by attempting to “purify” local identity as their perceived symbolic ownership of the place was threatened (Madanipour, Citation2004). Alaa recalled:

There are people here who – how can I put this? – who are maybe not racist, but they don’t like to share their things with others. Because first they live together nicely and then suddenly strangers come in. In their own circle […] look, they have negative ideas about us and I think this is because of people who arrived here before us. In their eyes, Turks and Moroccans – who have been here longer – did negative things here in the neighbourhood. I’m Syrian, but they also have negative ideas about Syrians who came here in the last few years. (Alaa, 19)

At least as a group, then, the original residents still hold and maintain authoritative power in the neighborhood due to their predominance in the local neighborhood association and their close connections with neighborhood governing institutions and social workers. The struggle for authority, for example, transpired through the type of activities that may be organized in the Molenwijkkamer. Because of its size, the Molenwijkkamer was a popular place for larger migrant families to host birthday parties, family rituals or religious festivities. However, as a community space, the neighborhood association determined that the Molenwijkkamer should be a “neutral” space, free of religion and open to activities that are inclusive for all neighborhood residents.

The racialized discourse is further reflected in how the availability of activities and the use of public neighborhood spaces, such as parks or squares, is highly regulated. After a neighborhood bingo session, Stephen (32), from Somalia, recalled how several years previously various migrant groups used public space for community activities, until these activities were reported by the local neighborhood association as being undesirable. He said:

This is all nice. I’m happy they invite newcomers to introduce themselves at the bingo, but in the end I’m just sitting here by myself. I feel welcome, but at the same time I don’t […] there were other activities here. We used to do big barbecues for example. Outside on the grass with music and festivities. But they cancelled all that. (Stephen, 32)

Conclusion

Through the conceptual lens of emplaced future selves, this paper shows that the relations young refugees have with the Molenwijk can be defined along a spectrum between attachment and detachment, belonging and non-belonging, and clear-cut and distorted future self-concepts. Their various interactions with social and physical elements of public neighborhood spaces produce a translocal geography of timely needs, and future possibilities and constraints that are often not connected to young refugees’ everyday lives (De Backer et al., Citation2023). We found that the specific emotional conditions and vulnerabilities resulting from migrant histories, identities and relations – namely insecurity, unfamiliarity, anxiety, stress and trauma – cause young refugees to self-identify with the neighborhood as they relate to the comforting, nourishing and empowering qualities of place. At the same time, the endangerment of future self-thinking due to marginalization and racialization, plus a lack of ownership and perspective that young refugees perceive in this neighborhood, appear to trouble local place identities and evoke place aversion (see also Bose, Citation2018; Huizinga, Citation2022). Through an iterative process of multiple and contradictory experiences, the neighborhood thus narrates who they are and who they are not, as well as who they can be or might risk becoming. This paper contributes to understanding localized urban systems of lived experiences and everyday practices, and the complex tensions and exclusionary politics of forced displacement and local emplacement in relation to work on the imagination of emplaced possible future selves (e.g. Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016; Prince, Citation2014). Below we highlight three points for further consideration.

First, the empirics contribute to understanding refugee youths as active producers of local urban spaces (Darling, Citation2017; Evans, Citation2020). By mobilizing their own agencies, histories and aspirations, and thereby “colouring” the neighborhood with patterns of their own translocal lives, young refugees contribute to lively urban place identities and functional public spaces that foster future self-conceptualization (Massey, Citation2005; Walton-Roberts et al., Citation2020). This paper provides insights into where and when urban public space functions for young refugees as a forward-looking opportunity (Hopkins, Citation2010), as well as a restorative place (Sampson & Gifford, Citation2010). By examining the distinct “material, imaginative and discursive realms” of refugee youths, it shows how these youths progressively shape the contours of the neighborhood, co-determine its identity and the “right” ways of “doing” the neighborhood (Basu & Fiedler, Citation2017, p. 44). As such, they too contribute to resisting contemporary nationalist imaginations and boundary making practices that tend to forget about the local (Walton-Roberts et al., Citation2020).

Second, this paper challenges representations of the “here and now” of refugee settlement being characterized solely by safety and freedom (Secor et al., Citation2022). Young refugees’ arrival is contingent on local identities and imaginations of territorial boundaries (Walton-Roberts et al., Citation2020). Everyday experiences of entrapment, exclusion and racism in arrival neighborhoods are both shaping and constraining emplaced conceptualizations of future selves. In fact, the city, as a “situated and contested interlocutor for state discourses and practices” (Darling, Citation2017, p. 192; see also Kreichauf & Glorius, Citation2021), remains a site that needs further scrutiny to understand how power continues to affect young refugees’ lives throughout their urban settlement experience.

Third, this paper illustrates how urban arrival areas characterized by underprivilege, socioeconomic disadvantage and stigma shape migrant and refugee trajectories in both negative and positive ways (see also Hanhörster & Wessendorf, Citation2020). It draws attention to the need to create urban conditions for mobile and multiple forms of self-identification and belonging for refugee youths and emphasizes that the neighborhood is more than merely social characteristics and aggregated numbers. This multidimensional perspective might be a suitable and complementary alternative in policy debates on refugee dispersal and settlement to the more stereotypical and exclusionary narratives around multicultural neighborhoods. Rather than focusing on young refugees’ “achievements” as individuals or as a group, this paper contributes to an understanding of local and contextual opportunity structures (Phillimore, Citation2020) and the development of young refugees’ trajectories in-place.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone who participated in this study and shared their experience with us. Our gratitude also goes out to the editor and reviewers for their invaluable and constructive comments to help further develop this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antonsich, M. (2010). Meanings of place and aspects of the self: An interdisciplinary and empirical account. GeoJournal, 75(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-009-9290-9

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press.

- Basu, R., & Fiedler, R. S. (2017). Integrative multiplicity through suburban realities: Exploring diversity through public spaces in Scarborough. Urban Geography, 38(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139864

- Bauder, H. (2001). Work, young people, and neighbourhood representations. Social and Cultural Geography, 2(4), 461–480.

- Bhagat, A. (2020). Governing refugees in raced markets: Displacement and disposability from Europe’s frontier to the streets of Paris. Review of International Political Economy, 29(3), 1–24.

- Bose, S. (2018). Welcome and hope, fear, and loathing: The politics of refugee settlement in Vermont. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(3), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000302

- Brickell, K., & Datta, A. (2011). Introduction: Translocal geographies. In K. Brickell & A. Datta (Eds.), Translocal geographies: Spaces, places, connections (pp. 3–21). Ashgate.

- Carabelli, G., & Lyon, D. (2016). Young people’s orientations to the future: Navigating the present and imagining the future. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(8), 1110–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1145641

- Darling, J. (2017). Forced migration and the city: Irregularity, informality, and the politics of presence. Progress in Human Geography, 41(2), 178–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516629004

- Darling, J. (2021). Refugee urbanism: Seeing asylum “like a city”. Urban Geography, 42(7), 894–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1763611

- De Backer, M., Hopkins, P., van Liempt, I., Finlay, R., Kirndörfer, E., Kox, M., Benwell, M. C., & Hörschellman, K. (2023). Refugee youth: Migration, justice and urban space. Bristol University Press.

- Dixon, J., & Durrheim, K. (2000). Displacing place-identity: A discursive approach to locating self and other. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466600164318

- Dunkel, C., & Kerpelman, J. (Eds.). (2006). Possible selves: Theory, research and applications. Nova Science.

- El-Moussawi, H., & Schuermans, N. (2021). From asylum to post-arrival geographies: Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Belgium. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 112(2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12469

- Evans, B. (2008). Geographies of youth/young people. Geography Compass, 2(5), 1659–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00147.x

- Evans, R. (2020). Picturing translocal youth: Self-portraits of young Syrian refugees and young people of diverse African heritages in South-East England. Population, Space and Place, 26(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2303

- Finlay, R., Hopkins, P., Kirndörfer, E., Kox, M., Huizinga, R. P., De Backer, M., Benwell, M. C., Van Liempt, I., Hörschelmann, K., Felten, P., Bastian, J. M., & Bousetta, H. (2022). Young refugees and public space. Newcastle University.

- Gemeente Amsterdam. (2020, September 23). Verkenning van kansen in Molenwijk. Principenota.

- Hamann, U., & El-Kayed, N. (2018). Refugees’ access to housing and residency in German cities: Internal border regimes and their local variations. Social Inclusion, 6(1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v6i1.1482

- Hanhörster, H., & Wessendorf, S. (2020). The role of arrival areas for migrant integration and resource access. Urban Planning, 5(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2891

- Hopkins, P. (2010). Young people, place and identity. Routledge.

- Huizinga, R. P. (2022). Carving out a space to belong: Young Syrian men negotiating patriarchal dividend, (in)visibility and (mis)recognition in the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 46(13), 3101–3122.

- Huizinga, R. P., & van Hoven, B. (2018). Everyday geographies of belonging: Syrian refugee experiences in the Northern Netherlands. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 96, 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.002

- Kox, M., & van Liempt, I. (2022). “I have to start all over again.” The role of institutional and personal arrival infrastructures in refugees’ home-making processes in Amsterdam. Comparative Population Studies, 47, 165–184.

- Kreichauf, R., & Glorius, B. (2021). Introduction: Displacement, asylum and the city – Theoretical approaches and empirical findings. Urban Geography, 42(7), 869–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1978220

- Madanipour, A. (2004). Marginal public spaces in European cities. Journal of Urban Design, 9(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357480042000283869

- Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.

- Oyserman, D., & Fryberg, S. (2006). The possible selves of diverse adolescents: Content and function across gender, race and national origin. In C. Dunkel & J. Kerpelman (Eds.), Possible selves: Theory, research and application (pp. 17–39). Nova Science.

- Paasi, A. (2001). Europe as a social process and discourse: Considerations of place, boundaries and identity. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977640100800102

- Pain, R. (2001). Age, generation and lifecourse. In R. Pain, J. Gough, G. Mowl, M. Barke, R. MacFarlane, & D. Fuller (Eds.), Introducing social geographies (pp. 141–163). Arnold.

- Peterson, M. (2020). Micro aggressions and connections in the context of national multiculturalism: Everyday geographies of racialisation and resistance in contemporary Scotland. Antipode, 52(5), 1393–1412. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12643

- Phillimore, J. (2020). Refugee-integration-opportunity structures: Shifting the focus from refugees to context. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(2), 1946–1966. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012

- Phillimore, J., & Goodson, L. (2006). Problem or opportunity? Asylum seekers, refugees, employment and social exclusion in deprived urban areas. Urban Studies, 43(10), 1715–1736. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600838606

- Pinkster, F. M. (2016). Narratives of neighbourhood change and loss of belonging in an urban garden village. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(7), 871–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1139169

- Prince, D. (2014). What about place? Considering the role of physical environment on youth imagining of future possible selves. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(6), 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.836591

- Rishbeth, C., Blachnicka-Ciacek, D., & Darling, J. (2019). Participation and wellbeing in urban greenspace: ‘Curating sociability’ for refugees and asylum seekers. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 106, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.014

- Sampson, R., & Gifford, S. M. (2010). Place-making, settlement and well-being: The therapeutic landscapes of recently arrived youth with refugee backgrounds. Health & Place, 16(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.004

- Secor, A. J., Ehrkamp, P., & Loyd, J. M. (2022). The problem of the future in the spacetime of resettlement: Iraqi refugees in the U.S. EPD: Society and Space, 0(0), 1–20.

- Soederberg, S. (2018). Governing global displacement in austerity urbanism: The case of Berlin’s refugee housing crisis. Development and Change, 50(4), 923–947. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12455

- Strahan, E. J., & Wilson, A. E. (2006). Temporal comparisons, identity and motivation: The relation between past, present, and possible future selves. In C. Dunkel & J. Kerpelman (Eds.), Possible selves: Theory, research and application (pp. 17–39). Nova Science.

- Twigger-Ross, C. L., & Uzzell, D. L. (1996). Place and identity processes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1996.0017

- Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133308089372

- van Liempt, I., & Bygnes, S. (2023). Mobility dynamics within the settlement phase of Syrian refugees in Norway and The Netherlands. Mobilities, 18(3), 506–519.

- van Liempt, I., & Staring, R. (2021). Homemaking and places of restoration: Belonging within and beyond places assigned to Syrian refugees in the Netherlands. Geographical Review, 111(2), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167428.2020.1827935

- Walton-Roberts, M., Veronis, L., Cullen, B., & Dam, H. (2020). A tale of three mid-sized cities: Syrian refugee resettlement and a progressive sense of place. In L. K. Hamilton, L. Veronis, & M. Walton-Roberts (Eds.), A national project: Syrian refugee resettlement in Canada (pp. 243–267). McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Wessendorf, S. (2014). Commonplace diversity: Social relations in a super-diverse context. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Williamson, R. (2016). Everyday space, mobile subjects and place-based belonging in suburban Sydney. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(14), 2328–2344. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1205803