ABSTRACT

Public housing is a crucial means of providing sufficient housing solutions worldwide. However, many experts criticize the harsh architecture, the absence of public space, and lacking social infrastructure in these densely populated public housing projects in the Global North. In China, previous research has mainly focused on the effect of public rental housing (PRH) on real estate values, employment trajectories of rural migrants, and their life challenges. Few studies have explored the dynamic relationship between rural migrants, their daily social life, and how it interacts with the environment. By conducting multiple site observations and 120 semi-structured interviews with rural migrants living in three different PRH sites in Chongqing, this study addresses these gaps and uncovers the complexities of their daily social lives. The findings show that rural migrant residents have established neighborhood networks, provided mutual support, and developed a sense of place attachment to their new homes through various strategies in their daily social lives. The research enriches the theoretical debate on migration theories and deepens our understanding of rural migrants’ social experiences in urban settings. It also sheds light on China’s sustainable urban development and the overall well-being of migrating populations.

Introduction

Rural migrants are individuals who have relocated from rural to urban areas in search of improved job opportunities and better access to education, healthcare, and services (Fan, Citation2003). Rural-urban migration is a common phenomenon in many countries, particularly in countries in the Global South where resources may be scarce in rural regions. As one of the major Global South nations, China has witnessed an unprecedented surge in internal rural-urban migration. The urbanization rate in China increased from 19.8% to 63.9% between 1980 and 2021 (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021). The rapid urbanization is accompanied by the exploitation of rural migrants who provide cheap labor for the factories and contribute to China’s glamorous economic miracle (Fan, Citation2007). Millions of rural migrants currently have no choice but to live in informal housing, such as in urban villages (Lin et al., Citation2011), and encounter various problems in their everyday lives. To address this issue, the Chinese central government has directed local governments to construct public rental housing (Hereafter PRH) on a large scale to accommodate rural migrants after the 20th CPC National Congress in 2022.

PRH is a new type of public housing that aims to provide affordable and stable housing with rents regulated by the government to primarily rural migrants and low-income urbanites with secure jobs. Shortly, millions of rural migrants are expected to move to PRH, provided by various municipalities throughout the country. Like public housing in the Global North, PRH units are designed to accommodate a large population with relatively low income, allowing them to enter and engage with the urban economy. However, in Western cultures, public housing is often associated with significant drawbacks. For instance, it may burden low-income communities, increasing transportation expenses and limiting residents’ access to social networks (de Duren, Citation2020). Residents of public housing estates feel they lack educational, economic, and social opportunities and often avoid revisiting these estates (Hastings, Citation2004).

In contrast to public housing in Western cultures, PRH programs in China operate differently due to the country’s socio-economic structure. The budget allocated by the central and local governments funds PRH, which provides affordable rent. Rural migrants who lack sufficient money and networks in the cities tend to rely on PRH to establish themselves in urban areas. Therefore, further research is necessary to comprehend their experiences within these neighborhoods, as rural migrants often encounter numerous challenges in their daily urban life (Hu, Citation2023c; Lin & Gaubatz, Citation2017). As Lefebvre et al. (Citation2017) and Soja (Citation1996) indicated, the impact of everyday life on human beings is diverse. It includes feelings of alienation, the influence of commodity culture, and urban living experiences. When rural migrants move to PRH, their daily lives change significantly due to the altered environment. One area that is particularly affected is their everyday social lives, which encompasses the daily mundane and ordinary activities that individuals engage in within a society. Recent studies have delved into various aspects of the daily practices of rural migrants, including their relocation to PRH (Hu, Citation2023c), their daily work (Hu, Citation2023b), their children’s schooling (Hu & Lu, Citation2023), and the challenges posed by institutional barriers (Hu, Citation2022, Citation2023d). As a result, the everyday social life of rural migrants in PRH in China, meaning the times people spend interacting with others, has not been studied adequately.

Furthermore, many international studies have explored the social ties and social lives of international immigrants living in various types of public housing in the Global North (Dominguez, Citation2008, Citation2011; Kleit & Manzo, Citation2006; Teixeira, Citation2014). However, studies have produced inconclusive findings regarding the impact of public housing on social life, with some indicating positive outcomes through the establishment of community ties (Lewicka, Citation2011; Varady & Walker, Citation2000) while others suggest the opposite (Méndez & Otero, Citation2018; Teo & Huang, Citation1996). Therefore, it is essential to study a Chinese case to enrich the current debate. Moreover, rural-urban migration in China presents different challenges than international migration. While international immigrants and internal rural migrants share many similarities, such as having low socio-economic statuses, the theoretical framework of international migration cannot be directly applied to internal migrants, especially Chinese rural migrants who typically face more institutional restrictions (Huang & Ren, Citation2022). Consequently, Chinese rural migrants’ everyday social lives differ from those of international immigrants. Although recent studies have examined the social lives of Chinese rural migrants, they have mainly focused on private housing (Chang et al., Citation2023; Tynen, Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2012) and informal housing (Liu, Zhang, Liu, et al., Citation2017; Liu, Zhang, Wu, et al., Citation2017) but overlooked PRH (except Chen & Li, Citation2015; however, the paper is written in Chinese). PRH is distinct from gated private housing estates and informal housing such as urban villages (Liu et al., Citation2015), and it may significantly impact the everyday social life of rural migrant residents. It thus deserves careful consideration. The present study investigates the everyday social life of rural migrants living in PRH by exploring their daily practices, including social interactions, relationships, mutual trust between community members, and attachment-building processes. The finding sheds light on the social lives of these migrating populations and China’s sustainable urbanization.

Literature review

The construction of social ties, their relationship to economics, environmental spatial configurations, and the community’s everyday social life is a complex topic. From the everyday perspective, Lefebvre et al. (Citation2017) contend that capitalism in Western countries can colonize our imaginations and permeate our everyday lives in incomprehensible ways. The context in China and Western capitalist countries differ, resulting in varying “lived spaces” and “perceived spaces” in their social relations and ties (Tynen, Citation2019). From the migration angle, the internal rural migrants in China are dramatically different from many immigrants living in public housing in the Global North, as Huang and Ren (Citation2022) argued. In addition, China’s PRH differs from other Chinese affordable housing (e.g. urban villages) from a spatial configuration perspective. Hence, this study aims to enhance the literature and theory of everyday geography by providing an empirical case in PRH neighborhoods in China. For the literature review, the article discusses three aspects: (1) the existing discoveries of social ties construction of rural migrants; (2) the PRH neighborhoods in China and their spatial context; and (3) the relationship between physical spaces and everyday experiences of rural migrants.

Social relations and social ties for rural migrants

Social relationships are generally considered beneficial for maintaining one’s psychological well-being (Kawachi & Berkman, Citation2001). Cultivating social connections, such as intimate relationships, community networks, or organizational involvement, has increased the likelihood of accessing support and coping with stressful events. For rural migrants who need to integrate into a new labor market and adjust to cultural differences, social ties and human capital are important indicators. Previous studies have found that social ties have a significant impact on the future trajectories of rural migrants (Korinek et al., Citation2005) and immigrants’ health (Viruell-Fuentes & Schulz, Citation2009). They often have positive effects on incomes and employment opportunities in destination cities (Pfeffer & Parra, Citation2009). Zhou and Guo (Citation2023) classified the social relations of rural migrants into three categories: local connections with the destination city, trans-local connections such as family and hometown relations, and fellow town connections. The first category pertains to how well the migrants integrate with the local community in their destination city. The second category includes connections beyond the local area, encompassing family members in the destination city and those back in their hometowns. The third category is the social network created by migrants from the same hometown in the destination city. Lastly, hometown relations are connections to their origin and may provide additional social support or services from their hometown communities. Zhou and Guo (Citation2023) found that local social connections are linked to better health outcomes for rural migrant communities, but too much reliance on family or fellow townsmen in destination cities can negatively impact their well-being. Social ties are vital to promote social interactions between migrants and local communities. This includes enhancing connections beyond the closed circle of fellow townspeople, which will be examined in this study.

Public housing neighborhoods and spatial context

The topic of neighborhoods and communities is frequently discussed in urban studies. But before we delve into it, we need to clarify the meaning of these terms. According to Wu and Logan (Citation2016), a neighborhood is where a group of people live in a bounded area. In China, neighborhoods are typically gated residential areas with clear boundaries (Chang et al., Citation2020). By contrast, a community refers to a social group living in a specific neighborhood with shared interests and values engaged in collective activities and practices (Chang et al., Citation2020). Despite the different definitions, neighborhoods, and communities are interconnected through the daily lives of their residents. Neighborhoods are crucial in studying the everyday life of rural migrants in China, as neighborhoods are the basic components of residential areas (Chang et al., Citation2020; Lu, Citation2006; Wu & Logan, Citation2016).

Public housing has a long-standing history and has been debated in the Global North. Residents of these housing projects are often connected to their communities. However, some projects, like Pruitt-Igoe, were poorly designed and lacked social support, protection, and informal social control, leading to negative perceptions and stigma (Yancey, Citation1971). Some scholars found that although residents engage in community work, they are hesitant to establish roots or build a strong sense of place attachment, fearing the stereotype of being seen as belonging to subsidized housing (Blokland, Citation2008). In contrast, studies in other parts of the world indicated that community ties were positively formed by establishing social relations in residents’ everyday lives. This, in turn, facilitated socio-spatial relations among residents, indirectly improving the sense of attachment (Lewicka, Citation2011). Consequently, many public housing residents had a sentimental attachment to the neighborhood and were unwilling to leave (Varady & Walker, Citation2000). The study of Kissane and Clampet-Lundquist (Citation2012) also found that community ties were beneficial to building social interactions and mutual support in public housing neighborhoods. However, some studies showed that public housing had negative social impacts on the neighborhoods, characterized by community deterioration and a lack of a sense of place in the US and Singapore post-war public housing (Heathcott, Citation2012; Méndez & Otero, Citation2018; Teo & Huang, Citation1996).

Since the findings of international studies are inclusive and have no consensus on this matter, examining a case from China is essential to enrich the literature and extend the debate from the Global North to Global South countries. In China, PRH and private housing have been found to have distinctive characteristics in terms of the built environment, residents’ socio-economic status, and social milieu (Chang et al., Citation2020; Gan et al., Citation2016). PRH is a modern approach to housing that differs from traditional socialist welfare housing. It consists of high-rise buildings on the outskirts of cities and is designed individually. In China, PRH units are limited to 90 square meters but offer significantly better living conditions than public housing units before the 1998 housing reform (Chen et al., Citation2014). Up till now, studies have evaluated the social space and social reproduction of public housing neighborhoods, such as the assessment of residents’ satisfaction (Gan et al., Citation2019), social integration (Chen & Li, Citation2015), and community attachment (Chang et al., Citation2020). However, literature gaps still exist. For example, Chang et al. (Citation2020) compared community attachment among residents living in public and private housing in China. However, the researchers neither focused on the perspective of rural migrant inhabitants nor thoroughly studied their everyday social lives. Considering the important role everyday social life plays in forming social ties in public housing in the Global North (Kleinhans et al., Citation2007), this is an essential gap in knowledge in China.

Everyday life and spatial configurations

In this paper, we refer to Eyles (Citation1989)’s concept that everyday life encompasses the routines and experiences of an individual or a social group, shaping and maintaining both their actions and environment. It is both a social context and a personal experience that has the power to reconstruct and redefine individuals and groups. Based on this concept, everyday social life is defined as the regular social activities, interactions, practices, and behaviors that individuals engage in as part of their daily lives. These activities may appear commonplace, but they are significantly influenced by the social, economic, and cultural structures in which individuals exist, as well as the broader sociological understanding of their context (Vaiou & Lykogianni, Citation2006). The physical spaces where daily life unfolds – such as homes, public spaces, and urban environments – significantly shape everyday social life. Much research in the Western world indicates the essential role of physical spaces in creating and transforming social ties. Lefebvre (Citation1974)’s concept of the Production of Space was the early frontier writing in highlighting the importance of physical space, and the ideological construction of experience related to the physical world. Soja (Citation1980)’s concept of “Socio-spatial Dialectic” was built on Lefebvre (Citation1974)’s discovery and further argued that space is not the scientific object to be eliminated from ideology and politics. Jacobs (Citation2016) and Simmel (Citation2011) have also emphasized the role of physical spaces in shaping and improving social interactions in low-income neighborhoods. Furthermore, a study by Kleinhans et al. (Citation2007) found that stronger social connections among residents are correlated with strong place attachment in public housing in the Netherlands. Therefore, to understand the effects of public housing on low-income residents, we can analyze the link between social life and attachment to the community. Taking an “everyday” view is a useful approach to assessing the neighborhood’s social lives and the level of attachment among its low-income inhabitants (Vaiou & Lykogianni, Citation2006).

In China, some recent studies showed that the everyday social practices of rural migrants positively shaped their bonds that revolve around their collective struggles, aspirations, and shared identities (Lin & Gaubatz, Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2015; Wu & Logan, Citation2016). These studies have provided a valuable platform for understanding the social lives of Chinese rural migrants in the rapid urbanization. Nevertheless, the existing studies have not focused on the daily social life of rural migrants in PRH or its relationship to spatial configurations. Lin and Gaubatz (Citation2017) contended that their daily life was socially and spatially segregated. However, the study did not investigate their residential neighborhoods’ spatial configuration. Previous studies have investigated the daily social practices of residents in private estates (Chang et al., Citation2023; Tynen, Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2012) and informal housing (Liu, Zhang, Liu, et al., Citation2017; Liu, Zhang, Wu, et al., Citation2017). However, PRH has not received much attention in this regard, except for a paper by Chen and Li (Citation2015), which is written in Chinese. PRH is distinct from gated private housing estates and informal housing such as urban villages (Liu et al., Citation2015), and it may significantly impact the everyday social life of rural migrant residents. Recent studies have investigated several facets of the everyday routine of rural migrants, such as their move to the PRH (Hu, Citation2023c), their work routine (Hu, Citation2023b), the education of their children (Hu & Lu, Citation2023), and the obstacles they face every day due to institutional barriers (Hu, Citation2022, Citation2023d). There has been inadequate study of the daily social life of rural migrants in PRH in China, which deserves careful consideration. The current study aims to fill these gaps by examining the daily social practices of rural migrants residing in PRH. This includes investigating their social ties, neighborhood networks, and processes for building attachments.

Methodology

The case of Chongqing

Chongqing, a rapidly growing megalopolis, was chosen for this study due to its unique spatial-political context and the fact that it was the first and only city to provide an extensive supply of PRH. While other Chinese municipalities began constructing PRH in 2011, the provision was limited, except for Chongqing (Huang & Ren, Citation2022). Since 2022, the Chinese government has decided to construct PRH on a larger scale throughout the country. The knowledge gained from studying PRH in Chongqing, which has been implemented on a large scale for a decade, can be applied to other pilot cities in China.

For centuries, Chongqing was part of Sichuan and shared similar dialects, cultures, and customs. However, in 1997, Chongqing was separated from Sichuan and became the only directly-controlled municipality (zhixiashi 直辖市) in western China, alongside Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin. These four cities are considered critical sites in China’s space economy (Bao et al., Citation2019; Hidalgo Martinez & Cartier, Citation2017). Chongqing is the newest of the four, with a historic urban core that spans a vast, underdeveloped rural area. The Chinese government’s decision to assign a strategic position to Chongqing was due to its importance in new rounds of urban and economic development in southwestern China and the Belt and Road Initiative (Smith, Citation2022).

Moreover, Bo Xilai’s “Chongqing Model” was crucial in developing Chongqing’s state-led urbanization. During Bo’s tenure as a party secretary from 2007 to 2012, Chongqing became the first city to systematically carry out urbanization reforms on a broad scale. This included implementing policies such as the dipiao policy (Hu, Citation2022), the massive distribution of local urban hukou (Hu, Citation2023d), and the extensive provision of PRH for rural migrants. For example, in 2011, the municipality launched an ambitious PRH program to build 40 million square meters (about 670,000 units). By 2017, nearly 360,000 PRH units had been provided in Chongqing, while in Shanghai, the PRH supply had only reached 115,000 units in the same year (Kanshangjie.com, Citation2020). As of the beginning of 2022, around 564,000 PRH apartments had been allocated to nearly 1.5 million people on the Chongqing periphery. More importantly, Chongqing eliminated the usual institutional barriers to allow rural migrants to access PRH, with applicants only needing to be over 18 years old, hold stable employment, and have made pension contributions for over six months. This made PRH a great driving force to accommodate rural migrants and promote Chongqing’s urbanization process, with half of the PRH tenants being rural migrants (Chongqing Municipal Government, Citation2022; Xinhua Net, Citation2019). By contrast, only 1% of the residents in PRH in Beijing were rural migrants in 2011 (Kaifeng Foundation, Citation2011). However, PRH in Chongqing has faced criticism for contributing to community decline and social decay (Lafarguette, Citation2011). This, in turn, could adversely impact the daily social interactions among rural migrants. The Chongqing case thus offers a unique perspective on the everyday social lives and struggles of rural migrants residing in PRH.

Place of fieldwork

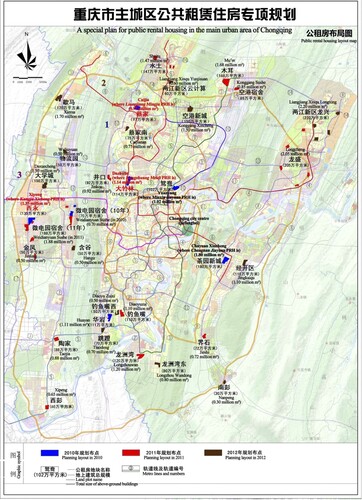

Between 2018 and 2020, 21 PRH sites were available in Chongqing, as shown in . Out of these, Kangzhuang Meidi (康庄美地), Liangjiang Mingju (两江名居), and Kangju Xicheng (康居西城) were the first batch of 5 PRH sites that were built in the city between 2012 and 2013 (see ). We selected these older PRH sites because the residents have lived there for a long time and could provide an insider’s view of their everyday social life in the PRH compared to other newly constructed PRHs. The other two PRH sites of the first batch were not considered due to potential biases in the social lives and daily experiences of rural migrants in those areas. These two sites are popular PRH sites that have received significant attention from the mass media and are often used for social propaganda.

Figure 1. Locations of PRH sites in Chongqing (Chongqing Public Rental Housing Administration Authority, Citation2012).

Table 1. Data of the selected PRH sites.

Sampling strategy, interviews, and observations

The study employed two methods of data collection – interviews with 120 rural migrants and site observations conducted in 2018 and 2019. Follow-up interviews were conducted with key informants in 2019 and 2020. The study randomly approached different participants in PRH and used snowballing to reach saturation. The qualified participants were selected if they were rural migrants over 18 years of age living in the three chosen PRHs in Chongqing for more than a year. This is based on Abu-Ghazzeh (Citation1999) finding that occupants of a dwelling no longer consider themselves temporary residents after one year. The researchers also ensured that only one participant represented each household. This ensured that the experiences of individuals and each family living in PRH were well understood. A total of 40, 34, and 46 interviewees were selected from Kangzhuang Meidi, Liangjiang Mingju, and Kangju Xicheng, respectively. The interviews were divided into three sections and lasted anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours. The first section was a structured interview that gathered information about the interviewee’s demographic and socio-economic background. In the second part, the respondents participated in a semi-structured discussion about their everyday social life. The questions included topics such as where and how they socialize with other PRH residents daily, how often they participate in community events in PRH, and some specific methods they used to build up their social life in PRH. The final section allowed for follow-up responses to the semi-structured discussions, such as whether residents feel at home in PRH daily and plan to continue living and socializing there. The collected interview data was transcribed, and direct quotes were selectively presented throughout the article. Pseudonyms are used to protect the privacy and anonymity of informants.

We conducted field observations at various times and days to locate how rural migrants utilize public spaces in PRH for everyday social interaction, and to provide testimony to the interview results. Non-participant and structured observations were used to collect qualitative and quantitative data on outdoor daily activities in PRH. Drawings and field notes were also used to record the everyday social life and activities of rural migrants. Selected data from site observation and secondary sources were transcribed, analyzed, and visually represented through mapping techniques and hand sketches to illustrate informants’ daily social interactions and events in public space in PRH.

Results and discussion

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

presents the demographic and socioeconomic data of the 120 participants in the study. The gender distribution was almost equal, with 52% (n = 62) identifying as male and 48% (n = 58) as female. Young rural migrants under 45 accounted for 60% (n = 72) of the participants. Over half of the respondents, 57% (n = 68), were originally from Chongqing, while the remaining participants were primarily from neighboring provinces such as Sichuan (28%, n = 34) and Guizhou (10%, n = 12). The study found that Chongqing PRH mainly attracts local and interprovincial rural migrants nearby, especially those from Sichuan, which shares a long history and similar culture. In terms of earnings, over half of the participants, 57.5% (n = 69), earned less than 3,000 CNY monthly. Conversely, only a small fraction of respondents, 15% (n = 18), reported earning over 5,000 CNY monthly. Regarding education levels, nearly three-quarters of the respondents (71%, n = 85) had completed China’s 9-year compulsory schooling encompassing primary and junior high school. However, most participants (92%, n = 110) had not pursued higher education. These findings align with prior studies and national data indicating that rural migrants have lower educational attainments and are situated at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder (Hu, Citation2023c; Lin & Gaubatz, Citation2017; National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2020). Regarding residency, four in five participants (81%, n = 97) lived in the PRH neighborhood for over two years. This suggests that it is likely that residents of PRH have formed social connections and feel a sense of attachment and belonging to their respective neighborhoods, given the previously reported positive association between length of residency and the development of social relationships (Abu-Ghazzeh, Citation1999). More than four in five (83%, n = 100) were living with their family, reflecting the household-oriented nature of the PRH in Chongqing, which in turn reflects the high value traditionally placed in China on family cohesion (Hu, Citation2023a, Citation2023c). The following section will examine how rural migrants have established community ties by employing various approaches and methods in their daily social activities.

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (n = 120).

Social lives based on kinship and territorial bonds

The interview data showed that rural migrants used three main strategies to connect with their new neighbors. These strategies included getting an introduction from fellow villagers (laoxiang 老乡) and relatives, using their children, and participating in informal community activities. All three strategies were found to be equally important during different stages of the relocation process. In PRH neighborhoods, initial social connections were established based on kinship and territory. This means most respondents brought their relationships from the countryside to the city. None of the participants had close ties with social groups outside their pre-existing rural networks, and certainly none with influential individuals in the city. Mr. Jia, a middle-aged migrant from Sichuan, shared his sincere thoughts on this topic.

We had lived in the country for most of our lives and barely had chances to connect to urban friends and relatives. When we first arrived in PRH, we had no other way to get to know anyone except for the old folks and village fellows. (interview No. 50b, 21 September 2019, Kangju Xicheng)

Furthermore, the quantitative data collected from the interviews reinforces the argument along with the qualitative data. As per , when the participants were asked how they had met new neighbors when they first moved to the PRH, almost half (45%, n = 54) established social connections in PRH via introductions from their relatives and fellow villagers. Only a few participants (1.5%, n = 2) met their neighbors through urban friends or colleagues. Many respondents who moved to PRH initially only had access to daily social life based on their rural background. However, they were able to develop a strong network based on kinship and territorial ties. This helped them establish new relationships and social life and maintain group unity. Numerous studies have shown that immigrant and migrant groups within China and abroad often form group unities and collective ties based on kinship and territorial connections (Lin & Gaubatz, Citation2017; Portes & Manning, Citation2019). By drawing on their pre-existing social networks, they could create new social networks and connections. However, their everyday social lives were limited to those within their existing interpersonal and territorial networks.

Table 3. How did rural migrants meet neighbors before (n = 120).

Social lives based on developing neighborhood networks

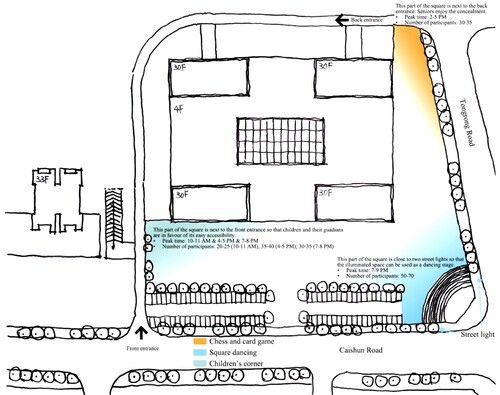

Social lives based on kinship and territorial networks are initially relatively simple, traditional, and exclusive. As a result, this type of social relationship does not help rural migrants to make new connections in PRH. However, the present study found forming neighborhood networks in PRH has expanded the social lives of rural migrants in their everyday lives. Many respondents have reported meeting other PRH residents through informal community activities in the community squares. These activities have become venues for socializing, such as morning exercises, caring for children and grandchildren, and playing cards and mah-jong. The square is also one of the most significant daily events after sunset, around 7 or 8 pm, where it serves as a venue for voluntary community activities such as the performance of square dancing (see ). Some respondents, mainly middle-aged and elderly rural migrants, relied more on square dancing to enrich their daily social lives. Mrs. Yuan is a full-time housewife in her early forties with her young family. She said:

I had never tried square dancing before relocation to the PRH, as its popularity is only increasing among city residents … Because being a full-time housewife at home was somewhat dull, my fellow villagers and I started dancing with other PRH residents, many of whom are urbanites. Subsequently, all the dancers became familiar with each other and started to talk more. And now, neighborhood chit-chat has become an ingrained part of our daily life. (interview No. 59, 11 May 2018, Liangjiang Mingju)

Figure 2. Square dancing in Kangzhuang Meidi PRH (Author, January 2018).

I agree (with Mrs. Yuan). Having neighborhood gossip is a way to exchange information in the city. It has become part of our daily life. Initially, the conversations with other square dancers were random and incomplete. Subsequently, however, most dancers became familiar with each other and started to say hello and talk more. (interview No. 58, 11 May 2018, Liangjiang Mingju)

Table 4. How do rural migrants meet neighbors nowadays (n = 120).

In addition, multi-functional spaces offer valuable opportunities for informal community activities, which can help build strong neighborhood networks and further expand everyday social lives. These spaces are designed to be human-scale, with a mix of commercial and social functions, including atriums in shopping malls, shaded teahouses, and temporary outdoor cinemas in PRH. Chongqing is amongst the three cities in China known as the “Three Furnaces” due to the hot and humid climate during summer. As a result, indoor shopping malls have become popular public spaces for various neighborhood events. Due to limited income, these communities rarely patronize commercial premises and prefer cost-free recreational venues like the atriums in shopping malls (). Over time, shopping malls and their adjacent open spaces have evolved into centralized squares in each PRH, not only for commercial purposes, but also for everyday social life and recreational activities. shows the “centralized square” in Liangjiang Mingju is an “L” shaped open space approximately 120 m × 30 m in scale and can accommodate multiple large-scale activities simultaneously. Like PRH, urban villages also have open spaces catering to everyday social activities. However, these spaces are much smaller, typically spanning only 10–20 meters. Even the larger squares do not exceed 35 meters in size. Consequently, daily social life in urban villages revolves around smaller-scale activities, and it is unlikely to have larger events, such as mass square dancing, that require bigger spaces, as seen in PRH areas.

Figure 3. Shopping mall and community square as public space (Image: author).

Figure 4. Activities and social interaction in the community square at Liangjiang Mingju (Image: author).

Besides the community squares and atriums, shaded areas under trees and street frontages between retail shops and pedestrian streets are the preferred multi-functional spaces for daily recreation and meeting with friends. Business owners have responded to this trend by setting up parasols to create a teahouse or positioning TV screens facing the sidewalks (see ). This has created multi-functional spaces with a human scale for social interaction in PRH, which facilitates the daily social life of individuals. Mrs. Pang’s noodle restaurant is an excellent example of using these spaces for both commercial and social purposes. After moving to Liangjiang Mingju PRH five years ago, she started her business and has been successful.

My restaurant is unlike other teahouses where you must pay to sit. Instead, I often tell neighbors, friends, and customers that they are welcome to sit and talk anytime but do not need to buy anything. Of course, this is a commercial strategy. Most people will buy something after sitting here for a while … A few middle-aged mah-jong players always like to come here for chitchat. The specialty of my restaurant is that it provides them with a space for socializing and exchanging neighborhood information. (interview No. 14, 7 February 2018, Liangjiang Mingju)

From neighborhood networks to mutual support

Manzo et al. (Citation2008) argue that mutual support, which forms the foundation of a sense of community, is established through daily interactions among neighbors. In the case of PRH in Chongqing, empirical evidence suggests the presence of mutual support among its residents. Many respondents have reported that they would seek help from their neighbors if needed, and Mrs. Sun is one of them. She is a senior migrant in her late 50s who moved to PRH to care for her granddaughter. She expressed satisfaction with her relationship with her new neighbors in PRH and believed that the mutual support came from their neighborhood networks.

I am satisfied with my relationships with the new neighbors in PRH. My old neighbors in the countryside always complained about little neighborliness in high-rise condominiums in the city … But in my experience, neighborliness in PRH is good … We [neighbors and I] chat daily while grocery shopping and exercising. So, I would consider my neighborhood networks in the PRH as strong as those in the countryside. (interviewee No. 22, 8 February 2018, Kangzhuang Meidi)

Table 5. Rural migrants’ neighborhood networks in PRH (n = 120).

Outside my family, I would ask my neighbors for help, especially neighbors in the same building … Most of my family members and relatives are in the countryside. Thus, it is better to have a neighbor who is near than a brother far off (远亲不如近邻) … I have an excellent interpersonal relationship with the neighbors. I guess that is why it was always my neighbors who offered help. Vice versa, when my neighbors are in trouble, I generously provide my support. (interview No. 22, 8 February 2018, Kangzhuang Meidi)

In contrast to Mrs. Sun’s case, Mrs. Pang, who utilized multi-functional spaces to establish neighborhood networks and grow her business, is an example of how mutual support can be developed from her perspective. Mrs. Pang commented:

Because of my business, I know many neighbors well. Because I know these neighbors well, they always visit my noodle shop often … I think it is partially because the neighbors want to suppose my business and partly because they trust the food provided is hygienic and delicious … I appreciate their support and trust. In turn, I always give them a discount to support them. As I said earlier, they are not only my customers but also my neighbors. (interview No. 14, 7 February 2018, Liangjiang Mingju)

From neighborhood networks to spatial attachment

The study found that some rural migrants who lived in PRH for a while continued to maintain their social lives by purchasing properties nearby. This allowed them to physically express their sense of social connectedness. Some respondents who had accumulated sufficient economic capital considered purchasing property for their families over time. Surprisingly, many decided to buy a property close to PRH, where they had lived for years. Through daily social practice in PRH, these respondents have produced an emotional attachment to the neighborhood and its people and wish to maintain their relationships and social lives. One of the respondents who considered buying a flat and was hesitant to move out of Liangjiang Mingju PRH is Mrs. Pang, a successful migrant businesswoman who manages a noodle restaurant in the PRH where she lives. She explained her family’s decision.

We are still deciding to buy a private flat because we are unsure about moving out of the PRH as we have settled here for over six years. The whole family has adapted well to our PRH unit and is familiar with all neighborhoods … Like we remember the street corners, community squares, and the night market … If we have to leave one day, I will miss this place, my noodle restaurant, and the people here throughout the years. (interview No. 14c, 4 October 2019, Liangjiang Mingju)

Another respondent, Mrs. Wang, demonstrated how neighborhood networks could lead to spatial attachment and help maintain rural migrants’ daily social life. Mrs. Wang is a middle-aged housewife who has been living in Kangzhuang Meidi PRH with her parents, husband, and two kids for over five years. Recently, her family purchased a small flat in a private estate next to the PRH, and her parents moved there. However, Mrs. Wang noticed that her mother did not enjoy living in the private estate,

While the private estate is quiet, with plenty of green space, there are rarely any community activities available for the residents. For example, square dancing is limited due to noise complaints, leaving walking in the open space as the only option. (interview No. 9, 2 February 2018, Kangzhuang Meidi)

My mother moved to a new house but always returned to the PRH neighborhood because she missed it. The PRH neighbors and her have certain locations within the neighborhood where they gather, such as an outdoor deck where they play mah-jong together year-round. (see ). Although cheap teahouses are available nearby where people can play mahjong, they choose not to go. (interview No. 9, 2 February 2018, Kangzhuang Meidi)

Conclusion

Our research contributes to the growing body of literature on public housing, the struggles and challenges rural migrants face, the theory of place attachment, and the relationship between people and their environment. We conducted empirical research in the social sciences to gain insight into the true sentiments of rural migrants towards the PRH that accommodates them, and how their past and future life experiences relate to the community and physical neighborhoods. This study examines the daily social life of Chinese rural migrants residing in Chongqing’s PRH and enhances our understanding of the social experiences of rural migrants in urban settings. The major finding is that rural migrants living in PRH have created neighborhood networks, provided mutual support, and developed a sense of place attachment to their new homes through various strategies in their daily social lives. Their social lives initially relied on existing rural kinship and village connections and expanded into a voluntary decision based on shared interests, mutual support, and group unity. As time passed, their everyday social lives not only continued to exist as a way for people to bond socially, but also rooted in a strong attachment to these physical spaces in PRH.

Moreover, some significant findings and observations are pertinent to the existing literature. In the past, public housing in Western cultures has generally received negative feedback, as they tend to segregate social classes, burden residents, and even stigmatize communities. However, this study presents a distinct scenario where the residents of three Chongqing PRH sites felt differently. Despite having lower levels of education and below-average wages, they attempted to engage with city residents, leverage their existing networks, and expand their social circles through public housing. The interview results indicate that the residents developed a deep sense of attachment to their neighbors, the PRH, and the environment surrounding them. There were various places such as shopping malls, shaded teahouses, temporary outdoor cinemas, Mrs. Pang’s restaurant, and the outdoor deck for mah-jong, which acted as informal spaces facilitating social life for rural migrants. Place attachment is a crucial factor for designers and planners, as these physical spaces hold special meaning, and creating social spaces can foster connections and strengthen bonds between individuals, groups, and communities (Owens et al., Citation2023). This study explores how PRH residents use these spaces to build routines, find comfort, support, and confidence to survive in the city, and discover meaning and connections.

Lastly, the research indicates that PRH is designed and built differently than private housing estates and informal housing in China. For example, open spaces in urban villages are much smaller than those in PRH, making it impossible to have a centralized public square and host large-scale events; open spaces within private estates have become privatized neighborhood environments that lack social attributes (Zhu et al., Citation2012). The findings show that rural migrant residents have successfully practiced different definitions of value and effectively produced their own social space and daily social lives. For instance, rural migrants utilize the multi-functional space in the neighborhood to establish and maintain their social lives, while also displaying reluctance to leave their new home (PRH) where they have developed social lives. This confirms Tynen’s (Citation2019) observations of low-income individuals residing in the old city center of Nanjing, China. In this regard, the present study extends the discussion by shifting the research focus from private housing (Chang et al., Citation2023; Tynen, Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2012) to informal housing (Lin & Gaubatz, Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2015) to PRH. Starting in 2022, the Chinese government has undertaken a large-scale construction of PRH to provide shelter for rural migrants. Therefore, this study also provides significant information about the social experiences and consequences of rural migrants in PRH, which is crucial to ensure China’s sustainable urban development and the overall well-being of migrating populations. This study has a limitation in that it primarily concentrates on rural migrants from “local” Chongqing and Sichuan, as most permanent resident holders are from these regions. To enhance future research, it would be advantageous to incorporate rural migrants from different areas to diversify the sources.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) would like to express their gratitude to Professor Duanfang Lu at the University of Sydney, the journal editor, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. The previous drafts of this paper were immensely improved by the constructive feedback provided by Professor Youqing Huang and Professor Carolyn Cartier. A special thanks to Professor Blair Kuys from Swinburne University of Technology for his exceptional support towards young scholars.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abu-Ghazzeh, T. M. (1999). Housing layout, social interaction, and the place of contact in Abu-Nuseir, Jordan. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19(1), 41–73. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1998.0106

- Bao, H. X., Li, L., & Lizieri, C. (2019). City profile: Chongqing (1997–2017). Cities, 94, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.06.011

- Blokland, T. (2008). “You got to remember you live in public housing”: place-making in an American housing project. Housing, Theory and Society, 25(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090601151095

- Brehm, J. M., Eisenhauer, B. W., & Krannich, R. S. (2004). Dimensions of community attachment and their relationship to well-being in the amenity-rich rural west. Rural Sociology, 69(3), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1526/0036011041730545

- Chang, J., Chen, H., Li, Z., Reese, L. A., Wu, D., Tan, J., & Xie, D. (2020). Community attachment among residents living in public and commodity housing in China. Housing Studies, 35(8), 1337–1361. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1667489

- Chang, J., Lin, Z., Vojnovic, I., Qi, J., Wu, R., & Xie, D. (2023). Social environments still matter: The role of physical and social environments in place attachment in a transitional city, Guangzhou, China. Landscape and Urban Planning, Online first, 232, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104680

- Chen, H., & Li, Z. (2015). Social integration of social housing communities in big cities of China: A case study of Guangzhou city (中国大城市保障房社区的社会融合研究——以广州为例). City Planning Review (城市规划), 39, 33–39.

- Chen, J., Yang, Z., & Wang, Y. P. (2014). The new Chinese model of public housing: A step forward or backward? Housing Studies, 29(4), 534–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.873392

- Chongqing Municipal Government. (2022). Circular of General Office of Chongqing Municipal People’s Government on printing and distributing the 14th Five-year Plan for Urban Housing Development of Chongqing (2021–2025) (重庆市人民政府办公厅关于印发重庆市城镇住房发展“十四五”规划 (2021—2025年)的通知). https://www.cq.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgkml/zfgb/2022/d7q/202205/t20220505_10682294.html.

- Chongqing Public Rental Housing Administration Authority. (2012). A special plan for public rental housing in the main urban area of Chongqing (重庆市主城区公共租赁住房专项规划). Chongqing Public Rental Housing Information Network (重庆市公共租赁房信息网). http://gzf.zfcxjw.cq.gov.cn/gzfxmzs/snztgh/.

- de Duren, N. R. L. (2020). The social housing burden: Comparing households at the periphery and the centre of cities in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. In P. Monkkonen (Ed.), Housing policy innovation in the Global South (pp. 11–37). Routledge.

- Dominguez, S. (2008). A tale of two projects: Bridging Latin-American immigrant women in public housing. Journal of City and Community, 42(3/4), 309–327.

- Dominguez, S. (2011). Getting ahead: Social mobility, public housing, and immigrant networks. NYU Press.

- Eyles, J. (1989). The geography of everyday life. Horizons in Human Geography, 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19839-9_6

- Fan, C. C. (2003). Rural-urban migration and gender division of labor in transitional China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00429

- Fan, C. C. (2007). China on the move: Migration, the state, and the household. Routledge.

- Fan, C. C., Sun, M., & Zheng, S. (2011). Migration and split households: A comparison of sole, couple, and family migrants in Beijing, China. Environment and Planning A, 43(9), 2164–2185. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44128

- Gan, X., Zuo, J., Baker, E., Chang, R., & Wen, T. (2019). Exploring the determinants of residential satisfaction in public rental housing in China: A case study of Chongqing. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 34(3), 869–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09691-x

- Gan, X., Zuo, J., Ye, K., Li, D., Chang, R., & Zillante, G. (2016). Are migrant workers satisfied with public rental housing? A study in Chongqing, China. Habitat International, 56, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.05.003

- Hastings, A. (2004). Stigma and social housing estates: Beyond pathological explanations. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 19(3), 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-004-0723-y

- Heathcott, J. (2012). Planning note: Pruitt-igoe and the critique of public housing. Journal of the American Planning Association, 78(4), 450–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2012.737972

- Hidalgo Martinez, M., & Cartier, C. (2017). City as province in China: The territorial urbanization of Chongqing. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58(2), 201–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2017.1312474

- Hu, W. (2022). Evaluating the ‘Dipiao’ policy from the perspectives of relocated peasants: An equitable and sustainable approach to urbanisation? Urban Research & Practice, 15(4), 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2022.2085377

- Hu, W. (2023a). A family-based approach to public rental housing in Chongqing, China: A perspective of rural migrant households. Town Planning Review, 94(3), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2022.13

- Hu, W. (2023b). Housing and occupational experiences of rural migrants living in public rental housing in Chongqing, China: Job choice, housing location and mobility. International Development Planning Review, 45(1), 95–120. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2022.8

- Hu, W. (2023c). Motivations and barriers in becoming urban residents: Evidence from rural migrants living in public rental housing in Chongqing, China. Journal of Urban Affairs, 45(10), 1804–1823. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.2011302

- Hu, W. (2023d). Why did Chongqing’s recent hukou reform fail? A Chinese migrant workers’ perspective. Urban Geography, 44(8), 1833–1842. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2022.2125667

- Hu, W., & Lu, D. (2023). Educational opportunity and public rental housing choice of rural migrant families in Chongqing, China. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2023.2237140

- Huang, Y., & Napawan, N. C. (2021). “Separate but equal?” Understanding gender differences in urban park usage and its implications for gender-inclusive design. Landscape Journal, 40(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.40.1.1

- Huang, Y., & Ren, J. (2022). Moving toward an inclusive housing policy?: Migrants’ access to subsidized housing in urban China. Housing Policy Debate, 1–28.

- Jacobs, J. (2016). The death and life of great American cities. Vintage.

- Kaifeng Foundation. (2011). A Report of Investigations of Public Rental Housing in Beijing and Chongqing (重庆北京公租房调研报告). Retrieved February 10, 2020, from http://www.kaifengfoundation.org/kfgyjjh/tabid/384/Default.aspx.

- Kanshangjie.com. (2020, July 14). How big is the impact of the largest provision of public rental housing in the universe on Chongqing in the end? (全宇宙最多的公租房,对重庆影响到底有多大?). Retrieved April 29, 2021, from http://www.kanshangjie.com/article/168039-1.html.

- Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78(3), 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.3.458

- Kissane, R. J., & Clampet-Lundquist, S. (2012). Social ties, social support, and collective efficacy among families from public housing in Chicago and Baltimore. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 39, 157.

- Kleinhans, R., Priemus, H., & Engbersen, G. (2007). Understanding social capital in recently restructured urban neighbourhoods: Two case studies in Rotterdam. Urban Studies, 44(5–6), 1069–1091. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701256047

- Kleit, R. G., & Manzo, L. C. (2006). To move or not to move: Relationships to place and relocation choices in HOPE VI. Housing Policy Debate, 17(2), 271–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2006.9521571

- Korinek, K., Entwisle, B., & Jampaklay, A. (2005). Through thick and thin: Layers of social ties and urban settlement among Thai migrants. American Sociological Review, 70(5), 779–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000503

- Lafarguette, R. (2011). Chongqing: Model for a new economic and social policy? China Perspectives, 2011(4), 62–64. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.5749

- Lefebvre, H. (1974). La production de l’espace. L’Homme et la société, 31(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.3406/homso.1974.1855

- Lefebvre, H., Rabinovitch, S., & Wander, P. (2017). Everyday life in the modern world. Routledge.

- Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

- Lin, Y., De Meulder, B., & Wang, S. (2011). Understanding the ‘village in the city’ in Guangzhou: Economic integration and development issue and their implications for the urban migrant. Urban Studies, 48(16), 3583–3598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010396239

- Lin, S., & Gaubatz, P. (2017). Socio-spatial segregation in China and migrants’ everyday life experiences: The case of Wenzhou. Urban Geography, 38(7), 1019–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1182287

- Liu, Y., Li, Z., Liu, Y., & Chen, H. (2015). Growth of rural migrant enclaves in Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China: Agency, everyday practice and social mobility. Urban Studies, 52(16), 3086–3105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014553752

- Liu, Y., Zhang, F., Liu, Y., Li, Z., & Wu, F. (2017). The effect of neighbourhood social ties on migrants’ subjective wellbeing in Chinese cities. Habitat International, 66, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.05.011

- Liu, Y., Zhang, F., Wu, F., Liu, Y., & Li, Z. (2017). The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities, 60, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.10.008

- Lu, D. (2006). Remaking Chinese urban form: Modernity, scarcity and space, 1949–2005. Routledge.

- Manzo, L. C., Kleit, R. G., & Couch, D. (2008). “Moving three times is like having your house on fire once”: The experience of place and impending displacement among public housing residents. Urban Studies, 45(9), 1855–1878. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008093381

- Méndez, M. L., & Otero, G. (2018). Neighbourhood conflicts, socio-spatial inequalities, and residential stigmatisation in Santiago, Chile. Cities, 74, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.11.005

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2020). 2019 annual survey report of migrant workers (2019 年农民工监测调查报告). China Statistics Press. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202004/t20200430_1742724.html.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Main data of the seventh national population census (第七次全国人口普查主要数据情况). China Statistics Press. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817176.html.

- Owens, P. E., Koo, J., & Huang, Y. (2023). Outdoor environments for people: Considering human factors in landscape design. Taylor & Francis.

- Pfeffer, M. J., & Parra, P. A. (2009). Strong ties, weak ties, and human capital: Latino immigrant employment outside the enclave. Rural Sociology, 74(2), 241–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2009.tb00391.x

- Portes, A., & Manning, R. D. (2019). The immigrant enclave: Theory and empirical examples. In D. Grusky (Ed.), Social stratification (pp. 568–579). Routledge.

- Simmel, G. (2011). Georg Simmel on individuality and social forms. University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, N. R. (2022). Continental metropolitanization: Chongqing and the urban origins of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Urban Geography, 1–21.

- Soja, E. W. (1980). The socio-spatial dialectic. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 70(2), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1980.tb01308.x

- Soja, E. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Blackwell Publishing.

- Teixeira, C. (2014). L iving on the “edge of the suburbs” of Vancouver: A case study of the housing experiences and coping strategies of recent immigrants in Surrey and Richmond. The Canadian Geographer/le Géographe Canadien, 58(2), 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2013.12055.x

- Teo, P., & Huang, S. (1996). A sense of place in public housing: A case study of Pasir Ris, Singapore. Habitat International, 20(2), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(95)00065-8

- Tynen, S. (2019). Lived space of urban development: The everyday politics of spatial production in Nanjing, China. Space and Culture, 22(2), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218774480

- Vaiou, D., & Lykogianni, R. (2006). Women, neighbourhoods and everyday life. Urban Studies, 43(4), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600597434

- Varady, D. P., & Walker, C. C. (2000). Vouchering out distressed subsidized developments: Does moving lead to improvements in housing and neighborhood conditions? Housing Policy Debate, 11(1), 115–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2000.9521365

- Viruell-Fuentes, E. A., & Schulz, A. J. (2009). Toward a dynamic conceptualization of social ties and context: Implications for understanding immigrant and Latino health. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2167–2175. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.158956

- Wu, F., & Logan, J. (2016). Do rural migrants ‘float’ in urban China? Neighbouring and neighbourhood sentiment in Beijing. Urban Studies, 53(14), 2973–2990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015598745

- Xinhua Net. (2019, March 27). Chongqing has allocated 505,000 units of public rental housing (重庆市累计分配公租房 50.5 万套). Retrieved February 10, 2021, from http://m.xinhuanet.com/cq/2019-03/27/c_1124287435.htm.

- Yancey, W. L. (1971). Architecture, interaction, and social control: The case of a large-scale public housing project. Environment and Behavior, 3(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391657100300101

- Zhou, M., & Guo, W. (2023). Local, trans-local, and fellow townspeople ties: Differential effects of social relations on physical health among China’s rural-to-urban migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49(1), 272–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2088485

- Zhu, Y., Breitung, W., & Li, S.-m. (2012). The changing meaning of neighbourhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Studies, 49(11), 2439–2457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011427188

- Zhu, Y., & Chen, W. (2010). The settlement intention of China’s floating population in the cities: Recent changes and multifaceted individual-level determinants. Population, Space and Place, 16(4), 253-267. doi:10.1002/psp.544