ABSTRACT

Pelecanus paranensis sp. nov., a new pelican (Aves, Pelecanidae) from the marine Upper Miocene Paraná Formation, which crops out in the Province of Entre Ríos, Argentina, is described. This record constitutes the first report of a fossil pelican from Argentina and the southernmost from South America. The holotypical specimen consists of a very large and nearly complete pelvis, which is characterized by having the cristae iliacae dorsales continuous throughout its entire length and a large foramen acetabuli. The U-shaped morphology of the postacetabular section of the pelvis of the new species as well as the wide incisura sutura iliosynsacralis, allow to infer its phylogenetic position within the New World pelican species clade, showing a close relationship with the clade (P. occidentalis + P. thagus). A probable trans-Atlantic dispersal route for the ancestor of the New World pelicans is thus inferred. The inland Paranaense Sea, which flooded the South American Chaco-Paraná basin during the mid-Neogene, is proposed as a south-north pathway for ancestral forms of the clade (P. occidentalis + P. thagus). These regressive marine paleoenvironments of the Late Miocene may have acted as the evolutionary driver for the transition of pelican species from brackish or freshwater habitats to those inhabiting strictly marine coastlines.

INTRODUCTION

Pelicans are very large waterbirds with a long bill and a distensible pouch. They have a worldwide distribution, except for Antarctica and inland South America, from tropical to warm temperate regions, inhabiting coastal and open brackish and freshwater environments (Elliott, Citation1992). Pelecanidae comprises eight living species in the single genus Pelecanus Linnaeus, Citation1758 (Elliott, Citation1992; Gill et al., Citation2022). Recent studies based on DNA sequences taken from both mitochondrial and nuclear genes allowed to separate these eight species into two well-supported clades: an Old World clade including the Great White (Pelecanus onocrotalus Linnaeus, Citation1758), the Dalmatian (Pelecanus crispus Bruch, Citation1832), the Spot-billed (Pelecanus philippensis Gmelin, Citation1789), the Pink-backed (Pelecanus rufescens Gmelin, Citation1789), and the Australian (Pelecanus conspicillatus Temminck, Citation1824) pelicans; as well as a New World clade grouping the American White (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos Gmelin, Citation1789), the Brown (Pelecanus occidentalis Linnaeus, Citation1766), and the Peruvian (Pelecanus thagus Molina, Citation1782) pelicans (Kennedy et al., Citation2013) (Fig. S1). The latter has been treated as a subspecies of the Brown Pelican (i.e., P. occidentalis thagus; e.g., Nelson, Citation2005), but genetic distances, differences in body size, color of plumage and other soft parts, hypotarsal morphology, as well as absence of interbreeding between their sympatric populations, support the species status of P. thagus (e.g., Gill et al., Citation2022; Harrison and Walker, Citation1976; Kennedy et al., Citation2013; Sibley and Monroe, Citation1990).

The paleontological record of pelicans is relatively poor (for a summary see Table S1), dating back to the late Eocene of Egypt with Eopelecanus aegyptiacus El Adli, Wilson Mantilla, Antar, and Gingerich, Citation2021. Other Old World fossil pelicans assigned to Pelecanus sp. are known from the early Oligocene of France (Louchart et al., Citation2011) and the Middle Miocene of Germany (Göhlich, Citation2017). Pelecanus tirarensis Miller, Citation1966, and Pelecanus fraasi Lydekker, Citation1891, were described from the late Oligocene of Australia and Middle Miocene of Germany, respectively (Olson, Citation1985; Rich and Van Tets, Citation1981; Worthy and Nguyen, Citation2020), and Pelecanus odessanus Widhalm, Citation1886, from the Upper Miocene of Ukraine (Olson, Citation1999; Zelenkov and Kurochkin, Citation2015). Two extinct taxa found in Pakistan and/or India, Pelecanus cautleyi Davies, Citation1880, and Pelecanus sivalensis Davies, Citation1880, are of an uncertain Late Miocene to Late Pliocene age (see Harrison and Walker, Citation1982; Lydekker, Citation1891; Stidham et al., Citation2014). Pelecanus aethiopicus Harrison and Walker, Citation1976, was described from the Upper Pliocene of Tanzania, although may be synonymous with the extant P. onocrotalus or P. crispus (see Louchart, Citation2008). Apart from Eopelecanus, the only fossil pelicans considered different from Pelecanus were placed in Miopelecanus Cheneval, Citation1984, including Miopelecanus gracilis (Milne-Edwards, Citation1867 from the Early Miocene of France, Miopelecanus intermedius (Fraas, Citation1870) from the Middle Miocene of Germany (Cheneval, Citation1984; Heizmann and Hesse, Citation1995), and putative specimens from the Middle Miocene of Kenya (Mayr, Citation2014).

The records of the New World include Pelecanus sp. from the Upper Miocene of Costa Rica (Valerio and Laurito, Citation2013; but see Discussion), Peru (Altamirano-Sierra, Citation2013), and Mexico (González Barba et al., Citation2021). Pelecanus schreiberi Olson, Citation1999, is the only undoubted fossil species described from the Lower Pliocene of Florida and North Carolina (U.S.A.; Olson, Citation1999; Olson and Rasmussen, Citation2001), whereas Pelecanus halieus Wetmore, Citation1933, from the Pliocene of Idaho, is probably a synonym of the living P. erythrorhynchos (see Becker, Citation1986; González Barba et al., Citation2021). Specimens tentatively attributed to Pelecanus erythrorhynchos were also recorded in the Upper Miocene of Oregon (Miller, Citation1944) and the Late Pliocene of California (Cassiliano, Citation1999) of Oregon and California (see González Barba et al., Citation2021). Fossil representatives of P. occidentalis are only known since the Late Pleistocene of North America (see Guthrie, Citation2009, Citation2010) (Table S1), but a fossilized egg from the Middle Pleistocene of Bermuda has also been referred to this species (Olson and Hearty, Citation2013). Pelecanus thagus has only been recorded in deposits from the latest Pleistocene–Holocene of Chile and Peru (see Dillehay et al., Citation2012; Peña-Villalobos et al. Citation2013) (Table S1).

Almost all Quaternary fossil specimens worldwide were assigned to extant species (e.g., Emslie, Citation1995; Louchart, Citation2008; Mead et al., Citation2006; Rich and Van Tets, Citation1981) (Table S1), except for Pelecanus cadimurka Rich and Van Tets, Citation1981 from Australia. The supposedly paleoendemic Pelecanus novaezealandiae described by Scarlett (Citation1966) from the Holocene of New Zealand is now considered a synonym of P. conspicillatus (e.g., Gill et al., Citation2010).

During the Middle–Late Miocene of South America, the record of the Chaco-Paraná basin shows a large seawater ingression (Paranaense or Entrerriense Sea) which, in northeastern Argentina, consists of shallow marginal marine and littoral sedimentary sequences of the Paraná Formation (see Aceñolaza, Citation2000; Iriondo, Citation1973; Orfeo, Citation2005; Orfeo et al., Citation2011). In Entre Ríos Province, the Paraná Formation has provided many records of fossil invertebrates (Pérez, Citation2013a, Citation2013b), but relatively few continental vertebrates (Brandoni et al., Citation2019). Among birds, the fossil record is very scarce and consists of fragmentary remains of a flamingo (cf. Phoenicopterus sp.; Candela et al., Citation2012) and a large darter (Macranhinga paranensis Noriega, Citation1992; see Diederle et al., Citation2012). The discovery of a fossil pelican in the upper levels of the Paraná Formation in northeastern Argentina allows us to analyze for the first time the presence of pelecanids in high latitudes of the southwestern Atlantic Ocean and to discuss paleobiogeographic hypotheses about the origin and dispersal of this cosmopolitan family.

GEOLOGICAL SETTING

In the Province of Entre Ríos, Argentina, the marine Paraná Formation is mostly known from surface studies in different outcrops (e.g., Aceñolaza, Citation2000; Brandoni et al., Citation2019; del Río et al., Citation2018; Frenguelli, Citation1920; Pérez et al., Citation2013), with thicknesses between 5 and 40 m, and consist mainly of siliciclastic sandstone and mudstone layers that show high concentration of cemented bioclastic beds toward the top of the unit. The skeletal concentration described (see Brandoni et al., Citation2019; Pérez et al., Citation2013) is part of a diverse faunal association mostly marine in nature, with few recorded continental terrestrial vertebrates (Candela et al., Citation2012).

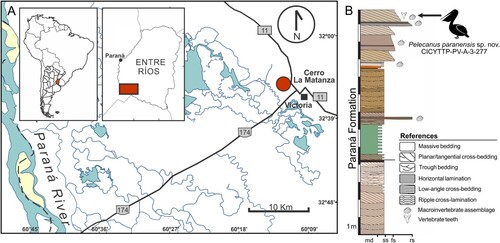

The specimen herein described comes from the sandstone marine beds of the Paraná Formation exposed near Victoria City at Cerro La Matanza locality, Entre Ríos Province, Argentina (). It is associated, as is most of the characteristic fossil content of the unit including rich vertebrate and macroinvertebrate assemblages, with the upper section of the Paraná Formation (see Brandoni et al., Citation2019; Pérez et al., Citation2013). Local deposits of the Paraná Formation () are characterized mainly by white to yellowish cross-bedded sandstone with quartz clasts composition and, less commonly, by bioclastic sandstone and heterolithic levels. They form tabular bodies, 1.5 m thick and tens of meters long, bounded by sharp to slightly erosive surfaces at the base, and compose sets of 0.3–5 m thick. These deposits can be interpreted as sedimentary facies accumulated in shoreface to foreshore environments (Clifton, Citation2006; Collinson and Thompson, Citation1989).

FIGURE 1. A, map of the study area, showing Cerro La Matanza locality (32°35′51″S, 60°11′22″W) in Victoria City (Entre Ríos Province, Argentina), where the holotype of Pelecanus paranensis comes from; B, stratigraphic local profile of the Paraná Formation.

The Paraná Formation has been mostly assigned to the Miocene (Aceñolaza, Citation1976; Aceñolaza and Sprechmann, Citation2002; Camacho, Citation1967; Cione et al., Citation2000; del Río, Citation1990, Citation1991; Frenguelli, Citation1920; Martínez and del Río, Citation2005). Recent analyses of strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr) from bivalves yielded ages of ∼9.47 Ma (Pérez, Citation2013a, Citation2013b) and 7.55–6.67 Ma (del Río et al., Citation2018), which indicate a Late Miocene age at least for the western Entre Ríos Province.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The osteological nomenclature follows Baumel and Witmer (Citation1993) and Livezey and Zusi (Citation2006) for pelvis, and Elzanowski et al. (Citation2000) for quadrate bones. The following comparative specimens were used: Chauna torquata, Phoenicopterus ruber, Vultur gryphus, Pygoscelis adeliae, Diomedea nigripes, Macronectes giganteus, Morus bassanus, Sula leucogaster, Fregata magnificens, Anhinga anhinga, Nannopterum auritum, Ardea herodias, Jabiru mycteria, Ciconia maguari, Scopus umbretta, Balaeniceps rex, Pelecanus occidentalis (6), P. thagus (7), P. conspicillatus (2), P. philippensis, P. rufescens, P. crispus (2), P. onocrotalus (3), and P. erythrorhynchos.

Measurements were made with digital calipers with an accuracy of 0.1 mm.

Institutional Abbreviations—CICYTTP, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Transferencia de Tecnológica a la Producción, Diamante, Argentina; FUR, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia; IMNH, Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello, U.S.A.; MNHT, Museu de História Natural de Taubaté, Taubaté, Brazil; MUSM, Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru; SMF, Senckenberg Research Institute, Frankfurt, Germany; UF, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, U.S.A.; USNM, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, U.S.A.

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Class AVES Linnaeus, Citation1758

Clade AEQUORNITHES Mayr, Citation2011

Order PELECANIFORMES Sharpe, Citation1891

Family PELECANIDAE Rafinesque, Citation1815

Genus PELECANUS Linnaeus, Citation1758

PELECANUS PARANENSIS, sp. nov.

(, )

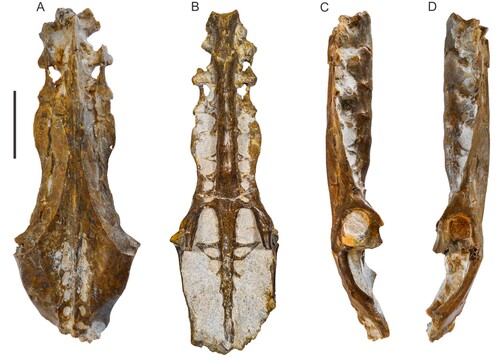

FIGURE 2. Nearly complete pelvis of Pelecanus paranensis (CICYTTP-PV-A-3-277) from Upper Miocene marine strata of Paraná Formation in Cerro La Matanza locality (Entre Ríos Province, Argentina). Holotype in dorsal (A), ventral (B), right (C), and left (D) views. Scale bar equals 50 mm.

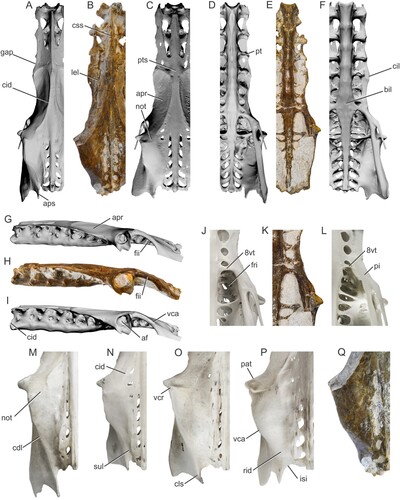

FIGURE 3. Comparisons of Pelecanus paranensis (holotype CICYTTP-PV-A-3-277) with the pelvic girdle of other Pelecanus spp. A, D, and G, Pelecanus erythrorhynchos (IMNH R-1901) in dorsal (A), ventral (D), and lateral (G) views; B, E, and H, Pelecanus paranensis (inverted) in dorsal (B), ventral (E), and lateral (H) views; C, F, and I, Pelecanus occidentalis (IMNH R-1605) in dorsal (C), ventral (F), and lateral (I) views; J–L, ventral detail of the synostotic vertebrae thoracicae and the fossae renales in Pelecanus crispus (SMF 21580, J), Pelecanus paranensis (inverted, K), and Pelecanus thagus (USNM 489428, L); M–Q, detail of postacetabular dorsocaudal section in Pelecanus conspicillatus (FUR 323, M), Pelecanus crispus (SMF, N), Pelecanus onocrotalus (MNHT 1979, O), Pelecanus thagus (USNM 489428, P), and Pelecanus paranensis (inverted, Q). Unscaled images for comparison, measurements in Table 1. Abbreviations: af, foramen acetabuli; apr, ala preacetabularis ilii; aps, ala postacetabularis ilii; bil, bulla intumescentia lumbosacralis; cdl, crista iliaca dorsolateralis; cid, crista iliaca dorsalis; cil, crista iliaca lateralis; cls, cristula lateralis spinae ilii; css, crista spinosa synsacralis; fii, foramen ilioischiadicum; fri, fossae renalis, pars ischiadica; gap, space between the ala preacetabularis ilii and the processus transversalis of the 3th vertebra thoracica; isi, incisura sutura iliosynsacralis; lel, lamina ellipsoidalis lateralis; not, notch for attachment of m. iliotrochantericus caudalis; pat, processus antitrochantericus; pi, pila ilioischiadica; pt, processus transversalis; pts, planum transversalium synsacralis; rid, ridge, reduced caudal crista iliaca dorsolateralis; sul, sulcus; vca, vertex caudolateralis ilii; vcr, vertex craniolateralis ilii; 8vt, synostotic vertebra thoracica (i.e., 8th).

Holotype—A nearly complete pelvis, CICYTTP-PV-A-3-277 (, ).

Etymology—paranensis, from the Paraná Formation, i.e., the stratigraphic provenance of the holotype.

Diagnosis—(1) large-sized species; (2) facies articularis cranialis of first fused vertebra thoracica compressed dorsoventrally; (3) processus transversales of three most cranial fused vertebrae thoracicae wide; (4) gap present between ala preacetabularis ilii and processus transversalis of third fused vertebra thoracica; (5) alae preacetabulares ilii strongly curved laterally; (6) planum transversalium and surface between cristae iliacae dorsales wide; (7) crista spinosa synsacralis robust, emerging cranially to alae preacetabulares ilii; (8) processus antitrochantericus not prominent; (9) cristae iliacae dorsales continuous throughout entire length (i.e., without flat notch for attachment of musculus iliotrochantericus caudalis); (10) postacetabular dorsocaudal section of pelvis U-shaped (i.e., crista iliaca dorsolateralis weak, blunt, and medially curved, caudally abbreviated and reduced to ridge; see below); (11) incisura sutura iliosynsacralis wide and shallow; (12) bulla intumescentia lumbosacralis slender; (13) processus costalis of last synostotic vertebra thoracica (i.e., eighth vertebra thoracica) stout and wide; (14) pila ilioischiadica short; (15) pars ischiadica of fossae renales quadrangular, narrow, and elongated craniocaudally; (16) caudal section of postacetabular synsacrum robust, lacking longitudinal crista; (17) foramen acetabuli large; (18) lamina infracristalis ilii expanded dorsoventrally; (19) foramen ilioischiadicum subelliptical.

Differential Diagnosis—Differs from P. occidentalis in characters (1), (2), (8), (12), (13), (14), and (15); from P. thagus in (2), (4), (8), (12), (13), (14), (15), and (16); from P. erythrorhynchos in (3), (6), (7), (10), (11), (15), (16), and (18); from P. onocrotalus in (4), (5), (6), (8), (10), (11), (15), and (16); from P. conspicillatus in (4), (5), (6), (8), (10), (11), (15), (16), and (18); from P. rufescens in (1), (4), (5), (6), (8), (10), (11), (16), and (18); from P. philippensis in (1), (3), (4), (5), (6), (8), (10), (11), (15), (16), (18), and (19); and from P. crispus in (1), (4), (5), (6), (8), (10), (11), (16), (18), and (19). The characters (9) and (17) are putative autapomorphies of the new species.

Locality and Horizon—The material comes from Cerro La Matanza locality (32°35′51″S, 60°11′22″W) in Victoria City, Entre Ríos Province, Argentina, from the upper sandstone marine beds of the Paraná Formation (). Radiometric and biochronological data indicate that the age of the Paraná Formation corresponds to the Late Miocene (Tortonian–Messinian stage).

Measurements—See .

TABLE 1. Comparative measurements (mm) of the pelvis plus synsacra, distal femora and quadrate bones in living Pelecanus spp., Pelecanus paranensis sp. nov. (holotype CICYTTP-PV-A-3-277), and other selected New World fossil taxa. Combined data from own measurements and those taken from (a) Rich and Van Tets (Citation1981), (b) Olson (Citation1999), and (c) Altamirano-Sierra (Citation2013). Abbreviations: D-cap, depth of caput femoris; L-dv, dorsoventral length; L-mand, length of mandibular articulation; TL, total length; W-II, width of the second vertebra thoracica at the level of its processus transversales; W-acet, width of the foramen acetabuli; W-dist, distal width; W-pa, width between processes antitrochantericarum; W-va, width of the fossa renalis at the level of the processus costales of the vertebra acetabularis.

Description and Comparisons—The pelvis CICYTTP-PV-A-3-277 is referable to Pelecanidae and differs from other Aequornithes, as well as from other large extinct or living South American birds (e.g., Rheidae, Pelagornithidae, Anhimidae, Anatidae, Phoenicopteridae, Palaelodidae, Phorusrhacidae, Cathartidae, Teratornithidae), in the following combination of characters (see also Pycraft, Citation1898:96): (1) three additional vertebrae thoracicae fused cranially to corpora vertebrarum synsacri through well-developed aponeurosis ossificans along their processus transversales (); (2) pila preacetabularis synsacri sturdy, cylindrical and, in lateral view, ventrally aligned in a horizontal plane, lacking any ventral expansion or cristae ventrales (); (3) alae preacetabulares ilii not extended or fused dorsocranially over these two or three most cranial vertebrae (); (4) relatively wide pelvis (not laterally compressed) with a preacetabular section noticeably longer than the postacetabular section (); (5) in lateral view, alae preacetabulares ilii oriented in a markedly horizontal plane (); (6) reduced foramina intertransversaria and present only on the postacetabular section ().

The size of the specimen representing the new taxon falls within the range of the large extant species P. onocrotalus, P. conspicillatus, P. erythrorhynchos, and P. thagus, being larger than P. rufescens, P. philippensis, and P. occidentalis, but smaller than P. crispus ().

In lateral and cranial view, unlike in P. occidentalis and P. thagus, the dorsoventrally compressed facies articularis cranialis of the first fused vertebra thoracica is a character shared by P. paranensis, all the Old World species and P. erythrorhynchos (, ). The great width of the cranial section of the dorsal synsacrum (i.e., the three most cranial fused vertebrae thoracicae) in P. paranensis constitutes a generalized condition which is observed in almost all pelicans (, ), except in P. erythrorhynchos and P. philippensis where it is relatively narrower. In P. paranensis there is a gap between the cranial rim of the ala preacetabularis ilii and the processus transversales of the third vertebra thoracica (, ), a character shared by P. erythrorhynchos and P. occidentalis, but absent or reduced in the other pelicans where the ala preacetabularis ilii rests directly on the processus.

In dorsal and, more evident, ventral views, the cranial section of the ala preacetabularis ilii of P. paranensis exhibits the crista iliaca lateralis laterally flared forming a rounded and prominent lamina ellipsoidalis lateralis (, ). As a consequence of this cranial enlargement, the midsections of the alae preacetabulares ilii show strongly curved or laterally concave contours like in P. erythrorhynchos, P. thagus, and P. occidentalis (); whereas in P. crispus this is even more accentuated, but in the remaining species the cristae iliacae laterales are straighter and near parallel, giving the appearance that the alae preacetabulares ilii have similar transverse widths along the entire length.

In dorsal view, like in P. occipitalis and P. thagus, both the planum transversalium and the space between the cristae iliacae dorsales are wider than in other compared species. The crista spinosa synsacralis has a development similar to that of P. onocrotalus, more robust than those of other Pelecanus spp. and, unlike in P. erythrorhynchos, it originates and rises more cranially (, ).

The processus antitrochantericus of P. paranensis presents a moderate development as in P. erythrorhynchos, not as prominent as in the other compared species. The relative dorsal width between these processes is also similar to that observed in P. erythrorhynchos, being markedly wider in P. onocrotalus, P. occidentalis, and P. thagus (). At this level, the most caudal section of the cristae iliacae dorsales of P. paranensis are strongly developed and extend continuously to the vertex craniolateralis ilii (, ). This condition is unique and contrasts with that displayed by other pelicans, where these cristae are interrupted by a caudal extension of the area for attachment of musculus iliotrochantericus caudalis that define a shallow and flat notch with a variable inter- and intraspecific development (). This latter notch is missing or unapparent in the new taxon.

Although narrower, the relatively shorter and U-shaped postacetabular dorsocaudal section of the pelvis of P. paranensis resembles those observed in P. occipitalis and P. thagus (, ). In dorsal view, this more rounded or globose configuration of the postacetabular pelvis is due to the laminae infracristales ilii being inflated laterally and the crista iliaca dorsolateralis being weak, blunt, and curved toward the sagittal plane, shrinking caudally to a short sigmoid ridge that extends to the cristula lateralis spinae ilii. On the caudodorsal surface of the ala postacetabularis ilii, this ridge laterally outlines a short and shallow sulcus which ends caudally in a wide incisura sutura iliosynsacralis (, ). In the remaining compared extant species, the postacetabular section is relatively longer and V-shaped because the crista iliaca dorsolateralis shows an acute and rather straight development to the cristula lateralis spinae ilii (). In these species, caudal to the vertex caudolateralis ilii, unlike in P. occipitalis, P. thagus, and P. paranensis, the crista iliaca dorsolateralis is longer, more conspicuous, sharper, and outlines a deeper sulcus that ends in a narrower incisura sutura iliosynsacralis ().

In ventral view, the proportions of the preacetabular corpora vertebrarum synsacri of P. paranensis are similar to those of P. erythrorhynchos, P. onocrotalus, and P. rufescens, being stouter than in P. crispus, and thinner than in P. conspicillatus and P. philippensis (mainly at the level of the third and fourth most cranial vertebrae thoracicae). The preacetabular corpora vertebrarum of P. paranensis is also slenderer than in P. occipitalis and P. thagus, where the last vertebrae thoracicae and first lumbares (bulla intumescentia lumbosacralis) are more laterally expanded than in the remaining pelicans. In this section, the processus costalis that joins the last synostotic vertebra thoracica (i.e., the eighth) with the pila ilioischiadica is stout and wide in P. paranensis (), a character shared with the Old World species and P. erythrorhynchos (). Instead, this process is strongly reduced or absent in P. occipitalis and P. thagus and in these species the main synostosis between the synsacrum and the pila ilioischiadica is the processus costalis of the penultimate vertebra thoracica (i.e., the seventh) (). Related to this configuration, the pilae ilioischiadicae in the latter two species show a more elongated and divergent aspect, delimiting much wider and subtriangular fossae renales (pars ischiadica fossae) than in the remaining pelicans, including P. paranensis (). These fossae are near quadrangular in P. paranensis (), but narrower than in P. onocrotalus and P. conspicillatus, and more craniodorsally elongated than in P. erythrorhynchos and P. philippensis, close to the condition observed in P. crispus and P. rufescens. Ventrally, the caudal section of the postacetabular synsacrum in the new species is robust like in P. occidentalis, and lacks a longitudinal crista just as in some individuals of this species.

In lateral view, the foramen acetabuli of P. paranensis is relatively larger than in other pelicans, and the lamina infracristalis ilii is dorsoventrally expanded like in P. onocrotalus, P. occidentalis, and P. thagus (, ). Unlike in P. crispus and P. philippensis, the foramen ilioischiadicum does not appear to have been subquadrangular in shape, but subelliptical.

DISCUSSION

Systematic and Phylogenetic Remarks

The striking similarities between the beak anatomy of fossil and living pelicans have been hypothesized to be indicative of long-term stasis in feeding morphology (Louchart et al., Citation2011). Other explanations for such conservatism consider the influence of flying ability as a constraint on the whole skeletal morphology (Louchart et al., Citation2011; Tyrberg, Citation2002). In a similar sense, Rich and Van Tets (Citation1981; see also Olson, Citation1999) noted a wide uniformity in the general skeletal morphology among extant pelican species, except for that of the New World P. occidentalis (including P. “occidentalis” thagus, currently with full species status).

As evidenced in the comparative description, the pelvis of P. paranensis is no exception from this remarkable morphological uniformity detected from the oldest Paleogene pelicans to the extant taxa (Louchart et al., Citation2011). However, the unique combination of 19 characters provided in the diagnosis of P. paranensis, which includes two exclusive features (cristae iliacae dorsales continuous throughout the entire length without a flat notch for attachment of musculus iliotrochantericus caudalis and large foramen acetabuli), justifies the erection of the new species.

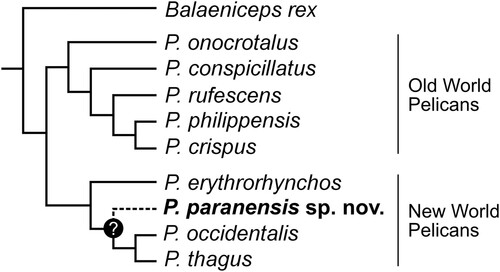

Pelecanus paranensis clearly shows closer affinities to the New World than to the Old World Pelican clade. Potential synapomorphies identified in the pelvis of the American species, including P. paranensis, are the presence of a gap between the cranial rim of the ala preacetabularis ilii and the processus transversalis of the third vertebra thoracica (probably secondarily reduced in P. thagus), and the strongly laterally curved alae preacetabulares ilii. This latter character is also observed, albeit better developed, in the large Dalmatian Pelican P. crispus. Other possible osteological synapomorphies of New World pelicans have been directly or indirectly suggested by previous authors, i.e., trochlea metatarsi II of the tarsometatarsus extending only slightly distal to the trochlea metatarsi IV (see Rich and Van Tets, Citation1981), the presence in the tarsometatarsus of a shallow and ridgeless surface proximal of the crista medialis hypotarsi and a square mid-plantar projection at the proximal end (see Stidham et al., Citation2014).

The general configuration of the pelvis of P. paranensis is more similar to those of the Brown and Peruvian pelicans, P. occidentalis and P. thagus. These three species exhibit a more derived morphology than the presumed ancestral condition observed in the American White Pelican, P. erythrorhynchos, which resembles the Old World taxa. Pelecanus paranensis shares some putative synapomorphic features with the clade (P. occidentalis + P. thagus), mainly the U-shaped postacetabular section and, related to this condition, the presence of a wide incisura sutura iliosynsacralis, but also a wide planum transversalium and space between the cristae iliacae dorsales.

Otherwise, like in P. erythrorhynchos and the Old World pelicans, P. paranensis lacks other possibly derived characters exclusive of the clade (P. occipitalis + P. thagus) such as: a high (not dorsoventrally compressed) facies articularis cranialis of the first fused vertebra thoracica, a well-developed bulla intumescentia lumbosacralis, a reduced or absent processus costalis of the last synostotic vertebra thoracica (i.e., the eighth), and the elongated and divergent pilae ilioischiadica delimiting wider and subtriangular fossae renales.

In sum, the morphology of P. paranensis not only exhibits possible derived characters only shared with P. occidentalis and P. thagus, but it also shows putative plesiomorphic features widespread in the Old World pelicans and P. erythrorhynchos. The mapping of the distribution of all these characters on the topology resulting from the molecular phylogeny of Kennedy et al. (Citation2013) suggests that P. paranensis is close to the clade including the New World species P. occipitalis and P. thagus, with P. erythrorhynchos being outside the clade including these three species ().

FIGURE 4. Hypothesized phylogenetic relationships of Pelecanus paranensis based on the morphological features of the pelvis observed in this study. The tree is based on the molecular phylogeny of extant pelicans of Kennedy et al. (Citation2013).

Comments on the Taxonomy and Phylogenetic Affinities of some New World Fossil Pelicans

Although the absence of homologous elements between P. paranensis and other New World fossil pelicans precludes direct comparisons, the review of the available paleontological record provides new clues to understand, at least preliminarily, the possible phylogenetic relationships among them.

Pelecanus schreiberi from the Lower Pliocene marine beds of Yorktown Formation, North Carolina (U.S.A.) was based on a distal femur and additional referred specimens (i.e., another distal femur and pedal phalanges from the type locality, but also an axis and two quadrate bones from coeval Bone Valley Formation, Florida; see Olson, Citation1999; Fig. S2). The femur of P. schreiberi is larger than those of the living New World species (), only comparable in size to the largest individuals of the largest living Old World species (P. crispus and P. onocrotalus), but the referred quadrates are smaller than those of South American P. thagus (not explicitly included in the comparisons by Olson, Citation1999; see below and ). In any case, the holotype of P. schreiberi shows a very divergent femoral morphology with respect to all living or extinct species of Pelecanus, “so great that it almost suggests a generic distinction” (Olson, Citation1999:504). Furthermore, P. schreiberi also differs in size and morphology from smaller Early–Late Miocene species of Miopelecanus (Olson, Citation1999).

The assignment of a fragmentary specimen from the Upper Miocene of Costa Rica to Pelecanus sp. by Valerio and Laurito (Citation2013) is controversial. The morphology and ossification pattern observed in the figured specimens (i.e., both Pelecanus sp. and Pelagornithidae indet.; see Valerio and Laurito, Citation2013:fig. 2) do not agree with any avian bone, but with autopodial mammal elements.

Prior to this contribution, the only known record of pelicans in the Neogene of South America was represented by an isolated quadrate bone from the Upper Miocene Pisco Formation of Peru (Altamirano-Sierra, Citation2013; Fig. S2), very close in age to P. paranensis (Montemar locality, ∼7.15–6.3 Ma; see Ochoa et al., Citation2022) and referred to Pelecanus sp. Among New World pelicans, the size of the Peruvian fossil specimen (MUSM 583, see ) resembles that of P. thagus, being larger than that of P. occidentalis and P. erythrorhynchos, as well as than those quadrates assigned to P. schreiberi (UF 125031 and UF 125030; Fig. S2) from the Bone Valley Formation (Florida, U.S.A.). Olson (Citation1999:504) did not provide any morphological evidence for an assignment of these latter specimens to P. schreiberi (based on a distal femur from a different locality and stratotype) and relied only on their larger sizes than the respective bones of P. occidentalis and P. erythrorhynchos. Similarly, the Peruvian specimen (MUSM 583) was compared in its original description with P. schreiberi, P. occidentalis, and P. thagus, whereas comparisons with P. erythrorhynchos were excluded (Altamirano-Sierra, Citation2013).

The overall robustness of the quadrates MUSM 583 and UF 125030 is close to that exhibited by P. erythrorhynchos rather than the slender configuration of P. occipitalis and P. thagus (Fig. S2). However, these specimens from Peru and Florida (especially UF 125030) exhibit a combination of unique traits among New World pelicans (e.g., large facies pterygoidea), as well as a mosaic of characters, some of them shared with P. erythrorhynchos (e.g., stoutness of corpus and processes; position and shape of cristae supraorbitalis, medialis, and infraorbitalis; location of condylus caudalis) and others with P. occidentalis and P. thagus (e.g., development and position of capitulum oticum; size of condyli medialis, caudalis, lateralis, and pterygoideus) (Fig. S2).

Thus, the congruence in sharing many characters with the “Brown” pelicans (P. occidentalis and P. thagus), their large sizes, as well as their nearly coeval ages and provenances from marine deposits, seem to suggest a possible close affinity between the specimens referred to P. schreiberi (but not with the holotype), the Peruvian Pelecanus sp., and P. paranensis.

Paleobiogeography of Pelecanidae and Implications of the New Record

The endemic African wading birds included in the families Scopidae and Balaenicipitidae, containing the extant hamerkop (Scopus umbretta Gmelin, Citation1789) and shoebill (Balaeniceps rex Gould, Citation1850), are recovered in molecular phylogenetic analyses together with Pelecanus as a clade different from other pelecaniforms (Cracraft et al., Citation2004; Ericson et al., Citation2006; Hackett et al., Citation2008; Prum et al., Citation2015). These phylogenetic hypotheses, coupled with the restriction of the fossil scopids and balaenicipitids to Africa (Rasmussen et al., Citation1987; Rich, Citation1972; Olson, Citation1984; Smith, Citation2013) and the recent finding of the late Eocene (early Priabonian) oldest known pelican (E. aegyptiacus) in Egypt (see El Adli et al., Citation2021), encouraged some authors to state that pelecanids emerged from Africa or southern Asia before dispersing to Europe, northern Asia, Australia, North America, and finally South America (El Adli et al., Citation2021; Johnsgard, Citation1993; Kennedy et al., Citation2013; Mayr, Citation2009).

Although the putative succession of events of allopatric speciation and dispersal of ancestral populations from Africa to Europe and from there to Asia, Australasia, and the eventual colonization of North America in a steady eastward direction is possible, it appears to constitute a fairly intricate evolutionary scenario. Alternative to this traditional view, the close relationship of P. paranensis to the New World clade, along with both its stratigraphic and geographic provenances, i.e., the Late Miocene (Tortonian/Messinian age) of southern South America, could be indicative of a different route of arrival of the ancestor of pelicans to the Americas. A trans-Atlantic dispersal route from Africa to the Americas could also explain the single colonization of this continent by a common ancestor of the New World clade after its basal divergence from the Old World clade.

South American Miocene Wetlands/Inland Seas’ Transitions: An Ecological Driver for the Radiation of “Brown” Pelicans?

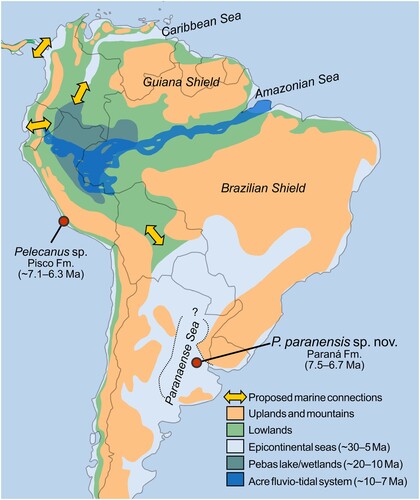

The alleged phylogenetic position of the new taxon would give some clues about the split that gave rise to the strictly marine coastal “Brown” pelicans. Pelecanus paranensis comes from sediments representing the littoral to marginal marine facies of the shallow inland Paranaense Sea, which covered central and northern Argentina during the mid–Late Miocene (Aceñolaza, Citation2000; Alonso, Citation2000; Malumián and Náñez, Citation2011; Marengo et al., Citation2019) ().

FIGURE 5. Tentative late Oligocene–Late Miocene paleogeography and pelican fossil records of South America. Probable extent of the Paranaense Sea indicated in dashed line. Modified from Hoorn et al. (Citation2010), Gross et al. (Citation2015) and references therein.

From the late Oligocene to the Early Pliocene, as the uplift of the Andes progressed and basins rearranged under tectonic loading, rainfall increased in the eastern lowlands (Amazonas/Solimões basins) and the epicontinental seas invaded coastal and inland areas of the northern and southern regions (e.g., Bicudo et al. Citation2020; Hernández et al., Citation2005; Hoorn et al., Citation2010; Jaramillo et al., Citation2017) (). In western Amazonia, a mega-wetland with episodic marine influence from the Caribbean Sea (see, e.g., Wesselingh and Salo, Citation2006), known as the Pebas system, reached its climax phase during the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (Hoorn et al., Citation2010, Citation2022). With global cooling and sea-level drop in the Late Miocene, the Pebas wetland transitioned from a lacustrine to a fluvial or fluvio-tidal system (Acre system), starting its Atlantic drainage through the transcontinental Amazon River ().

Multiple proxies demonstrated that these highly dynamic, heterogeneous and extensive freshwater/marine environments (including lakes, swamps, marshes, tidal channels, estuaries, deltas, and large marine embayments with periods of variable salinity and vast flood-regressive plains) have played a particularly important role in the diversification of the South American biota as selective barriers for terrestrial taxa and speciation hotspots for aquatic taxa during the Early–Late Miocene (e.g., Candela et al., Citation2012; Hoorn et al., Citation2010, Citation2022; Noriega et al., Citation2017; Ortiz Jaureguizar and Cladera, Citation2006).

The impact that the Early–Late Miocene marine ingressions would have had in the cladogenesis of different groups of South American birds has already been discussed, focusing on the idea of the imposition of dividing barriers of terrestrial avian populations (e.g., Cariamidae, Rheidae, and probably Tinamidae) on one or the other side of the marine flooding (Noriega et al., Citation2017). The radiation, dispersal, and extinction of large aquatic birds (i.e., Anhingidae) was even conditioned by the presence of extensive and highly productive marine/freshwater landscapes (Cenizo and Agnolín, Citation2010). Hoorn et al. (Citation2022) proposed that repeatedly altered environmental conditions in the Pebas system by switching from brackish to freshwater due to marine incursions primarily favored the speciation of taxa living along niche gradients.

Although possibly with greater marine influence, this general appreciation can be extrapolated to the transgressive-regressive cycles of the Paranaense Sea. Indeed, the latter has been considered as a shallow seaway, with temperate-warm and brackish waters, not strictly salty, but with a great contribution of fresh water (Marengo et al., Citation2019; Pérez et al., Citation2010).

Considering the habitat preferences of living pelicans from a phylogenetic point of view, it is clear that the truly coastal marine species (P. occidentalis and P. thagus) have a derived ecology compared with P. erythrorhynchos within the New Word clade, as well as the remaining species of the Old World cluster, which are mainly inhabitants of freshwater and/or brackish mudflats (e.g., lakes, lagoons, rivers, wetlands). Likewise, the genetic distances between P. erythrorhynchos and P. occidentalis + P. thagus suggest that the separation of these two clades is evolutionarily long-standing (see Kennedy et al., Citation2013:219), and this is supported by the Late Miocene occurrence of representatives of both lineages (). Kennedy et al. (Citation2013) hypothesized that the split between both habitats may have resulted in the appearance of the brown plumage as an adaptation to the wear and tear of salt water on feathers. In this context, the dynamic freshwater/brackish paleoenvironments associated with the Pebas mega-wetland and/or the Paranaense Sea seems to be the ideal scenario for such an evolutionary transition from ancestral freshwater-adapted forms to more derived, strictly coastal, marine forms. Only future findings of more complete fossil specimens can help evaluate with greater depth and accuracy the past diversity and biogeographic history of pelicans.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JIN and MC drafted the manuscript, LMP and DET gathered the geological data, MC and DB made the figures, JIN, MC, DB, JMD, and PB analyzed the paleontological data. All authors edited the manuscript.

LIST OF SUPPLEMENTARY FILES

Supplementary File 1: Figure S1.tif., full geographic ranges of living Pelecanus spp. with their superimposed phylogenetic affinities.

Supplementary File 2: Figure S2.tif, comparisons of the quadrate bone in fossil and living New World species of Pelecanus.

Supplementary File 3: Table S1.docx, summary of the global fossil record of Pelecanidae and main references.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.3 MB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Bogan (CFA-OR), G. Mayr (SMF), T. Worthy (FUR), D. Jackson, and J. Alarcón-Muñoz (Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile) for providing us with comparative images; M. G. Gottardi (CICYTTP) for preparing the specimen; M. C. Balparda for allowing access to Cantera Cerro La Matanza quarry. Editor V. De Pietri and reviewers G. Mayr and A. Louchart made constructive suggestions for improvement of the manuscript. UADER and CONICET grants supported this research.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aceñolaza, F. G. (1976). Consideraciones bioestratigráficas sobre el Terciario marino de Paraná y alrededores. Acta Geológica Lilloana, 13, 91–107.

- Aceñolaza, F. G. (2000). La Formación Paraná (Mioceno medio): estratigrafía, distribución regional y unidades equivalentes. In F. G. Aceñolaza & R. Herbst (Eds.), Serie Correlación Geológica: Vol. 14. El Neógeno de Argentina (pp. 9–28). Ediciones Magna, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Aceñolaza, F. G., & Sprechmann, P. (2002). The Miocene marine transgression in the meridional Atlantic of South America. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen, 225, 75–84.

- Alonso, R. (2000). El Terciario de la Puna en tiempos de la ingresión marina paranense. In F. G. Aceñolaza & R. Herbst (Eds.), Serie Correlación Geológica: Vol. 14. El Neógeno de Argentina (pp. 163–180). Ediciones Magna, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Altamirano-Sierra, A. J. (2013). Primer registro de pelícano (Aves: Pelecanidae) para el Mioceno tardío de la Formación Pisco, Perú. Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines, 42, 1–2.

- Baumel, J. J., & Witmer, L. M. (1993). Osteologia. In J. J. Baumel, King, S. A. Breazile, J. E., Evans, H. E., & J. C. Venden Berge (Eds.), Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium (pp. 45–132). Publications of the Nuttal Ornithological Club 23, Cambridge.

- Becker, J. J. (1986). Fossil birds of the Oreana local fauna (Blancan), Owyhee County, Idaho. Great Basin Naturalist, 46, 763–768.

- Bicudo, T. C., Sacek, V., & Paes de Almeida, R. (2020). Reappraisal of the relative importance of dynamic topography and Andean orogeny on Amazon landscape evolution. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 546, 116423.

- Brandoni, D., Brea, M., Brunetto, E., Diederle, J. M., Franco, M. J., Góis, F., Lutz, A., Noriega, J. I., Pérez, L. M., Schmidt, G. I., & Zucol, A. F. (2019). Paleontología del Mioceno tardío de la región Noroeste de Argentina. In N. Nasif, G. Esteban, J. Chiesa, A. Zurita, and S. Georgieff (Eds.), Opera Lilloana: Vol. 52. Mioceno al Pleistoceno del centro y norte de Argentina (pp. 131–286). Fundación Miguel Lillo, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Bruch, C. F. (1832). Jena, Expedition der Isis, 1820-1848. In L. Oken (Ed.), Isis von Oken, Vol. 24–41 (pp. 1109–1110).

- Candela, A. M., Bonini, R., & Noriega, J. I. (2012). First continental vertebrates from the marine Paraná Formation (Late Miocene, Mesopotamia, Argentina): Chronology, biogeography, and palaeonvironments. Geobios, 45, 515–526.

- Camacho, H. H. (1967). Las transgresiones del Cretácico superior y Terciario de la Argentina. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina, 22, 253–280.

- Cassiliano, M. L. (1999). Biostratigraphy of Blancan and Irvingtonian mammals in the Fish creek-Vallecito section, southern California, and a review of the Blancan- Irvingtonian boundary. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontolology, 19, 169–186.

- Cenizo, M. & Agnolín, F. L. (2010). The southernmost records of Anhingidae and a new basal species of Anatidae (Aves) from the Lower-Middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Alcheringa, 34, 493–514.

- Cheneval, J. (1984). Les oiseaux aquatiques (Gaviiformes á Ansériformes) du gisement aquitanien de Saint-Gérand-le Puy (Allier, France): révision systématique. Palaeovertebrata, 14, 33–115.

- Cione, A. L., Azpelicueta, M., Bond, M., Carlini, A., Casciotta, J., Cozzuol, M., de la Fuente, M., Gasparini, Z., Goin, F., Noriega, J. I., Scillato-Yané, G. J., Soibelzon, L., Tonni, E. P., Verzi, D., & Vucetich, M. G. (2000). Miocene vertebrates from Entre Ríos, eastern Argentina. In F. G. Aceñolaza & R. Herbst (Eds.), Serie Correlación Geológica: Vol. 14. El Neógeno de Argentina (pp. 191–237). Ediciones Magna, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Clifton, E. H. (2006). A reexamination of facies models for clastic shorelines. In H. W. Posamentier & R. G. Walker (Eds.), SEPM Special Publication, Vol. 84. Facies Models Revisited (pp. 293–337). Society for Sedimentary Geology, Broken Arrow.

- Collinson, J. D., & Thompson, D. B. (1989). Sedimentary structures. Chapmann and Hall, London.

- Cracraft, J., Barker, F. K., Braun, M., Harshman, J., Dyke, G. J., Feinstein, J., Stanley, S., Cibois, A., Schikler, P., Beresford, P., & García-Moreno, J. (2004). Phylogenetic relationships among modern birds (Neornithes). In J. Cracraft & M. J. Donoghue (Eds.), Assembling the Tree of Life (pp. 468–489). Oxford University Press, New York.

- Davies, W. (1880). On some fossil bird-remains from the Siwalik Hills in the British Museum. Geological Magazine, 7, 18–27.

- del Río, C. J. (1990). Composición, origen y significado paleoclimático de la malacofauna “Entrerriense” (Mioceno medio) de la Argentina. Anales Academia Nacional de Ciencias Exactas Físicas y Naturales, 42, 205–224.

- del Río, C. J. (1991). Revisión sistemática de los bivalvos de la Formación Paraná (Mioceno medio) provincia de Entre Ríos-Argentina. Monografía de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 7, 11–93.

- del Río, C. J., Martínez, S. A., McArthur, J. M., Thirlwall, M. F., & Pérez, L. M. (2018). Dating Late Miocene marine incursions across Argentina and Uruguay with Sr-isotope stratigraphy. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 85, 312–324.

- Diederle, J. M., Noriega, J. I., & Acosta Hospitaleche, C. (2012). Nuevos materiales de Macranhinga paranensis Noriega (Aves: Pelecaniformes: Anhingidae) del Mioceno de la provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 15, 203–210.

- Dillehay, T. D., Bonavia, D., Goodbred, S. L., Pino, M., Vásquez, V., & Tham, T. R. (2012). A Late Pleistocene human presence at Huaca Prieta, Peru, and early Pacific Coastal adaptations. Quaternary Research, 77, 418–423.

- El Adli, J. J., Wilson Mantilla, J. A., Antar, M. S., M., & Gingerich, P. D. (2021). The earliest recorded fossil pelican, recovered from the late Eocene of Wadi Al-Hitan, Egypt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 41(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2021.1903910

- Elliott, A. (1992). Pelecanidae. In J. Del Hoyo, Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J. (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World: Vol. 1. Ostrich to ducks (pp. 290–311). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

- Elzanowski, A., Paul, G. S., & Stidham T. A. (2000). An avian quadrate from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 20, 712–719.

- Emslie, S. D. (1995). An early Irvingtonian avifauna from Leisey Shell Pit, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, 37, 299–344.

- Ericson, P. G., Anderson, C. L., Britton, T., Elzanowski, A., Johansson, U. S., Källersjö, M., Ohlson, J. I., Parsons, T. J., Zuccon, D., & Mayr, G. (2006). Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils. Biology Letters, 2, 543–547.

- Fraas, O. (1870). Die Fauna von Steinheim. Mit Rücksicht auf die miocänen Säugethier und Vogelreste des Steinheimer Beckens. Württembergische naturwissenschaftliche Jahreshefte 26 (2–3), pp. 184.

- Frenguelli, J. (1920). Contribución al conocimiento de la geología de Entre Ríos. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba, 24, 55–256.

- Gill, B. J., Bell, B. D., Chambers, G. K., Medway, D. G., Palma, R. L., Scofield, R. P., Tennyson, A. J. D., & Worthy, T. H. (2010). Checklist of the Birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. Ornithological Society of New Zealand and Te Papa Press, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Gill, F., Donsker, D., & Rasmussen, P. (2022). International Ornithological Committee, World Bird List (v12.1). https://doi.org/10.14344/IOC.ML.12.1

- Gmelin, J. F. (1789). Caroli a Linné, Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Decima Tertia, Aucta, Reformata/cura Jo. Frid. Gmelin. Vol. 1, part 3. Lipsiae: Impensis Georg Emanuel Beer, Leipzig, Germany.

- Göhlich, U. B. (2017). Catalogue of the fossil bird holdings of the Bavarian State Collection of Palaeontology and Geology in Munich. Zitteliana, 89, 331–349.

- González-Barba, G., Schwennicke, T., & Goedert, J. L. (2021). First Neogene record of Pelecanus (Aves: Pelecanidae) from México. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 112, 103583.

- Gould, J. (1850). The Athenaeum. Journal of English and Foreign Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts, 1207, 1315.

- Gross, M., Ramos, M. I. F., & Piller. W. E. (2015). A minute ostracod (Crustacea: Cytheromatidae) from the Miocene Solimões Formation (western Amazonia, Brazil): evidence for marine incursions? Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 14, 581–602.

- Guthrie, D. A. (2009). An Updated Catalogue of the Birds from the Carpinteria Asphalt, Pleistocene of California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, 108, 52–62.

- Guthrie, D. A. (2010). Avian material from Rancho del Oro, a Pleistocene locality in San Diego County, California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, 109, 1–7.

- Hackett, S. J., Kimball, R. T., Reddy, S., Bowie, R. C., Braun, E. L., Braun, M. J., Chojnowski, J. L., Cox, W. A., Han, K. L., Harshman, J., & Huddleston C. J. (2008). A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history. Science, 320, 1763–1768.

- Harrison, C. J. O., & Walker C. A. (1976). A new fossil pelican from Olduvai. Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Geology), 27, 315–320.

- Harrison, C. J. O., and Walker, C. A. (1982). Fossil birds from the Upper Miocene of Pakistan. Tertiary Research Special Papers, 4, 53–69.

- Heizmann, E. P. J., & Hesse A. (1995). Die mittelmiozänen Vogel- und Säugetierreste des Nördlinger Ries (MN 6) und des Steinheimer Beckens (MN 7)–ein Vergleich. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, 181, 171–185.

- Hernández, R. M., Jordan, T. E., Dalenz Farjat, A., Echavarría, L., Idleman, B. D., & Reynolds, J. H. (2005). Age distribution, tectonics, and eustatic controls of the Paranense and Caribbean marine transgressions in southern Bolivia and Argentina. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 19, 495–512.

- Hoorn, C., Wesselingh, F. P., ter Steege, H., Bermúdez, M. A., Mora, A., Sevink, J., Sanmartín, I., Sánchez-Meseguer, A., Anderson, C. L., Figueiredo, J. P., Jaramillo, C., Riff, D., Negri, F. R., Hooghiemstra, H., Lundberg, J., Stadler, T., Särkinen, T., & Antonelli. A. (2010). Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution and biodiversity. Science, 330, 927–931.

- Hoorn, C., Boschman, L. M., Kukla, T., Sciumbata, M., & Val, P. (2022). The Miocene wetland of western Amazonia and its role in Neotropical biogeography. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 199, 25–35.

- Iriondo, M. H. (1973). Análisis Ambiental de la Formación Paraná en su área tipo. Boletín de la Asociación Geológica de Córdoba, 2, 19–23.

- Jaramillo, C., Romero, I., D’Apolito, C., Bayona, G., Duarte, E., Louwye, S., Escobar J., Luque, J., Carrillo-Briceño, J. D., Zapata, V., Mora, A., Schouten, S., Zavada, M., Harrington, G., Ortiz, J., & Wesselingh, F. P. (2017). Miocene flooding events of western Amazonia. Science Advances, 3. http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/5/e1601693.full

- Johnsgard, P. A. (1993). Cormorants, Darters and Pelicans of the World. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Kennedy, M., Taylor, S. A., Nádvorník, P., & Spencer, H. G. (2013). The phylogenetic relationships of the extant pelicans inferred from DNA sequence data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 66, 215–222.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, Vol. 1: Regnum Animale; 10th rev. ed. Salvii, L. Holmiae, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, Editio duodecima reformata. Tomus I [part 2]. Typis Ioannis Thomae, Vienna, Austria.

- Livezey, B. C., & Zusi, R. L. (2006). Phylogeny of Neornithes. Bulletin Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 37, 1–544.

- Louchart, A. (2008). Fossil birds of the Kibish Formation. Journal of Human Evolution, 55, 513–520.

- Louchart, A., Tourment, N., & Carrier, J. (2011). The earliest known pelican reveals 30 million years of evolutionary stasis in beak morphology. Journal of Ornithology, 152, 15–20.

- Lydekker, R. (1891). Catalogue of the Fossil Birds in the British Museum. British Museum, London.

- Malumián, N. & Náñez, C. (2011). The Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic transgressions in Patagonia and Fueguian Andes: foraminifera, palaeoecology, and paleogeography. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 103, 269–288.

- Marengo, H. G., Forasiepi, A., & Chiesa, J. (2019). Estratigrafía, paleontología y paleoambientes del Mioceno temprano y medio del Centro y Norte de Argentina. In N. Nasif, G. Esteban, J. Chiesa, A. Zurita, and S. Georgieff (Eds.), Opera Lilloana: Vol. 52. Mioceno al Pleistoceno del centro y norte de Argentina (pp. 15–108). Fundación Miguel Lillo, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Martínez, S. A., & del Río, C. J. (2005). Las ingresiones marinas del Neógeno en el sur de Entre Ríos (Argentina) y Litoral Oeste de Uruguay y su contenido malacológico; In F. G. Aceñolaza (Ed.), Miscelánea: Vol. 14. Temas de la Biodiversidad del Litoral fluvial argentino II (pp. 13–26). Ediciones Magna, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Mayr, G. (2009). Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- Mayr, G. (2011). Metaves, Mirandornithes, Strisores and other novelties: a critical review of the higher-level phylogeny of neornithine birds. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 49, 58–76.

- Mayr, G. (2014). On the middle Miocene avifauna of Maboko Island, Kenya. Geobios, 47, 133–146.

- Mead, J. I., Baez, A. Swift, S. L., Carpenter, M. C., Hollenshead, M., Czaplewski, N. J., Steadman, D. W., Bright, J., & Arroyo-Cabrales, J. (2006). Tropical marsh and savanna of the late Pleistocene in northeastern Sonora, Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist, 51, 226–239.

- Miller, L. (1944). Some Pliocene birds from Oregon and Idaho. The Condor, 46, 25–32.

- Miller, A. H. (1966). The Fossil Pelicans of Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 14, 181–190.

- Milne-Edwards, A. (1867). Recherches anatomiques et paléontologiques pour servir à l'histoire des oiseaux fossiles de la France, t.1. Victor Masson et fils.

- Molina, G. I. (Ed.). (1782). Saggio sulla storia naturale del Chili. Nella Stamperia di S. Tommafo d’ Aquino, Bologna, Italy.

- Nelson, J. B. (2005). Pelicans, cormorants, and their relatives: Pelecanidae, Sulidae, Phalacrocoracidae, Anhingidae, Fregatidae, Phaethontidae. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Noriega, J. I. (1992). Un nuevo género de Anhingidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) de la Formación Ituzaingó (Mioceno Superior) de Argentina. Notas del Museo de La Plata, Paleontología, 21, 217–223.

- Noriega, J. I., Jordan, E. A., Vezzosi, R. I., & Areta, J. I. (2017). A New Species of Opisthodactylus Ameghino 1891 (Aves, Rheidae) from the late Miocene of Northwestern Argentina, with implications for the paleobiogeography and phylogeny of rheas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 37(1). http://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2017.1278005

- Ochoa, D., De Vries, T. J., Quispe, K., Barbosa-Espitia, A., Salas-Gismondi, R., Foster, D. A., Gonzales, R., Revillon, S., Berrospi, R., Pairazamán, L., Cardich, J., Pérez, A., Romero, P., Urbina, M., & Carré, M. (2022). Age and provenance of the Mio-Pleistocene sediments from the Sacaco area, Peruvian continental margin. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 116, 103799.

- Olson, S. L. (1984). A hamerkop from the Early Pliocene of South Africa (Aves, Scopidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 97, 736–740.

- Olson, S. L. (1985). The fossil record of birds. In D. S., Farner, J. R. King, & K. C. Parkes (Eds.), Avian Biology, Vol. 8 (pp. 79–252). Academic Press, New York.

- Olson, S. L. (1999). A new species of pelican (Aves: Pelecanidae) from the Lower Pliocene of North Carolina and Florida. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 112, 503–509.

- Olson, S. L., & Rasmussen, P. C. (2001). Miocene and Pliocene birds from the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina. In C. E. Ray & D. J. Bohaska (Eds.), Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology: Vol. 90. Geology and Paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina (pp. 233–365). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

- Olson, S. L., & Hearty, P. J. (2013). Fossilized egg indicates probable breeding of Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) on Bermuda in the Middle Pleistocene. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 126, 169–177.

- Orfeo, O. (2005). Historia Geológica del Iberá, provincia de Corrientes, como escenario de biodiversidad. In F. G. Aceñolaza (Ed.), Miscelánea: Vol. 14. Temas de la Biodiversidad del Litoral fluvial argentino II (pp. 71–78). Ediciones Magna, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Orfeo, O., Georgieff, S., Anis, K., & Rizo, G. (2011, June 22–25). Depósitos sedimentarios modernos y antiguos del Río Paraná (Corrientes, Argentina): Un Análisis Comparativo. XXIII Congreso Nacional del Agua Resistencia, Chaco, Argentina.

- Ortiz Jaureguizar, E., & Cladera, G. A. (2006). Paleoenvironmental evolution of southern South America during the Cenozoic. Journal of Arid Environments, 66, 498–532.

- Peña-Villalobos, I., Olguín, L., Fibla López, P., Castro, V., & Sallaberry, M. (2013). Aprovechamiento humano de aves marinas durante el Holoceno medio en el litoral árido del norte de Chile. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 86, 301–313.

- Pérez, L. M. (2013a). Nuevo aporte al conocimiento de la edad de la Formación Paraná, Mioceno de la provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina. In D. Brandoni & J. I. Noriega (Eds.), Publicación Especial: Vol. 14. El Neógeno de la Mesopotamia argentina (pp. 7–12). Asociación Paleontológica Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Pérez, L. M. (2013b). Sistemática, tafonomía y paleoecología de los invertebrados de la Formación Paraná (Mioceno), provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina.

- Pérez, L. M., Genta Iturrería, S. F., & Griffin, M. (2010). Paleoecological and paleo-biogeographic significance of two new species of bivalves in the Paraná Formation (late Miocene) of Entre Ríos province, Argentina. Malacología, 53, 61–76.

- Pérez, L. M., Griffin, M., & Manceñido, M. O. (2013). Los macroinvertebrados de la Formación Paraná: Historia y diversidad de la fauna bentónica del Mioceno marino de Entre Ríos, Argentina. In D. Brandoni & J. I. Noriega (Eds.), Publicación Especial: Vol. 14. El Neógeno de la Mesopotamia argentina (pp. 56–70). Asociación Paleontológica Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Prum, R. O., Berv, J. S. Dornburg, A., Field, D. J., Townsend, J. P., Lemmon, E. M., & Lemmon, A. R. (2015). A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature, 526, 569–573.

- Pycraft, W. P. (1898). Contribution to the osteology of birds. Part I. Steganopodes. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1898, 82–101.

- Rafinesque, C. S. (1815). Analyse de la nature ou Tableau de l’univers et des corps organisés. Imprimerie de Jean Barravecchia, Palermo, Italy.

- Rasmussen, D. T., Olson, S. L., & Simons, E. L. (1987). Fossil birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation, Fayum Province, Egypt. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, 62, 1–20.

- Rich, P. V. (1972). A fossil avifauna from the Upper Miocene, Beglia Formation of Tunisia. Notes du Service géologique, Travaux de Géologie de Tunisie, 35, 29–66.

- Rich, P. V., & Van Tets, J. (1981). The fossil pelicans of Australia. Records of the South Australian Museum (Adelaide), 18, 235–264.

- Scarlett, R. (1966). A pelican in New Zealand. Notornis, 13, 204–217.

- Sharpe, R. B. (1891). A Review of Recent Attempts to Classify Birds: an address delivered before the Second International Ornithological of May, 1891, Budapest. Office of the Congress, Taylor and Francis, London.

- Sibley, C. G., & Monroe, B. L. Jr. (1990). Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Smith, N. A. (2013). Avian fossils from the early Miocene Moghra Formation of Egypt. Ostrich, 84, 181–189.

- Stidham, T. A., Krishan, K., Singh, B., Ghosh, A., & Patnaik, R. (2014). A Pelican tarsometatarsus (Aves: Pelecanidae) from the Latest Pliocene Siwaliks of India. PLoS ONE, 9, Article 111210. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111210

- Temminck, C. J. (1824). Nouveau recueil de planches coloriées d'oiseaux, pour servir de suite et de complément aux planches enluminées de Buffon, Vol. 11. F. G. Levrault Libraire, Paris-Strasbourg, France.

- Tyrberg, T. (2002). Avian species turnover and species longevity in the Pleistocene of the Palearctic. In Z. Zhou & F. Zhang (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution (pp. 281–289). Science Press, Beijing, China.

- Valerio, A. L., & Laurito, C. A. (2013). Primer registro de aves fósiles (Pelecaniformes: Pelecanidae y un probable Odontopterygiformes: Pelagornithidae) para el Mioceno Superior de Costa Rica. Revista Geológica de América Central, 49, 25–32.

- Wesselingh, F. P., & Salo, J. A. (2006). A Miocene perspective on the evolution of the Amazonian biota. Scripta Geologica, 133, 439–458.

- Wetmore, A. (1933). Pliocene Bird Remains from Idaho. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 87(20), 1–12.

- Widhalm, J. (1886). Die Fossilen Vogel-Knochen der Odessaer-Steppen-Kalk-Steinbrüche an der Neuen Slobodka bei Odessa. Schriften der Neurussische Gesellschaft der Naturforscher zu Odessa, 10, 3–9.

- Worthy, T. H., & Nguyen, J. M. T. (2020). An annotated checklist of the fossil birds of Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 144, 66–108.

- Zelenkov, N. V., & Kurochkin, E. N. (2015). Class Aves. In E. N. Kurochkin, A.V. Lopatin, & N. V. Zelenkov (Eds.), Iskopaemye pozvonochnye Rossii i sopredelnykh territoryi. Iskopaemye reptilii i ptitsy. Chast’ 3 [Fossil Vertebrates of Russia and Adjacent Countries: Fossil Reptiles and Birds, Part 3] (pp. 86–290). GEOS, Moscow, Russia.