Abstract

In this article, I explore the biographies of three professional black-and-white photographers of the 1970s from Batcham, West Cameroon. They are Edouard Fofou, alias Photo-Edouard; Michel Kenne, also known as Photo-Kmichel and Gaspard Vincent Tatang, alias Tagavince. They and their work stands as an example of the very many African photographers whose work could be archived but probably will not be. If we know of a few celebrated names like Malik Sidibe but not Vincent Tatang it is as much by chance as anything else. This then is an exploration of a possible but unrealized archive. What we could call an archival path not taken.

Following the pioneering work of Edwards (Citation1992) on early photographic archives, anthropologists working in Africa such as Bajorek (Citation2010), Buckley (Citation2008), Geary (Citation1986, Citation1990, Citation2013), Haney (Citation2010), Morton (Citation2012), Werner (Citation1996) and Zeitlyn (Citation2010, Citation2015a) have drawn attention to the importance of the work of African studio photographers. This paper provides an exploration of some studio photographers from a small town in West Cameroon, and considers ways in which their work may be a resource for historians and anthropologists but only if it is, somehow, archived. There are many reasons why material does not end up in archives. Le Febvre (Citation2015) gives one account of the historical, macro- and micro-political reasons why a local archive was not established. In this paper, I consider the history of material which is eminently archivable but is very likely never to be so treated. Inspired by work such as Dilley (Citation2014) on the life and work of a colonial administrator and Herzfeld (Citation1997) on a Greek novelist, and the earlier micro-history work of Ginzburg (Citation1980) this piece takes a biographical approach to the creators of the contents of archives.Footnote1 The careers of these photographers exemplify the complexity of historiography. In their life stories we “find futures that are known and anticipated, but their achievement is uncertain and often contested” Hirsch and Stewart (Citation2005, 271). Moreover, since at the time of writing there is little chance of the work of these men actually being archived, these biographies have a particularly poignancy, tracing the historical contexts of archives not-to-be. It would be a welcome irony if as a consequence of writing this article, their work were to be archived after all. I leave for another occasion the discussion of historical causality (and the causality of historians) that this would necessitate. As Zeitlyn discusses in the introduction to this issue, we must consider the hypothetical roads not taken, including those turnings caused by our own actions.

Somewhat forgotten today even in the town where they worked, Edouard Fofou, alias Photo-Edouard; Michel Kenne, also known as Photo-Kmichel and Gaspard Vincent Tatang, alias Tagavince, were once the most celebrated black-and-white professional photographers of 1970s Batcham, an administrative district of the larger department of Bamboutos.Footnote2 Kenne established himself in nearby Mbouda,Footnote3 where the photographer Jacques Toussele was prominent. Tagavince practiced his trade first in Nkongsamba,Footnote4 then throughout Cameroon, and finally, elsewhere in Africa. Fofou learnt photography when working on a plantation on the coast before returning to Batcham to establish his studio. The work of these three photographers declined in the mid-1980s as colour photography became increasingly popular. With varying degrees of success, each tried to adapt to this turn of events. In this paper, I will consider their professional paths and their primary accomplishments. How did they respond to the decline in their profession? What is the current state of their work and its archival legacy (negatives, photographs and materials)?

Influenced by pan-Africanism and its advocates, Vincent Gaspard Tatang describes himself to be of “African nationality”. He was born on 28 February 1957, in Kumba (his parents were from Batcham). While in Nkongsamba, he found a social association for Bamiléké emigrants from the Mungo region. At the urging of his older brother, Jean Jacques, Tatang applied for a place in the 6th form at Manengouba High School, where Jean Jacques had also studied. It was there that, in 1972, in the 5th form, he discovered photography and enrolled in the school's photography club.

I discovered correspondence photography lessons by chance. Photography became a passion and I've taken many photos. I've even travelled abroad to present my photographic works. We put together a collective exhibition in the 1990s that pretty much went all around the world. So I've truly embraced photography. For me, it's an extremely significant art, because from one photograph, you can write an entire book; and also because we operate in a civilization that celebrates the image. Unfortunately, this “civilization of the image” comes at a time when photography as a profession has an arrow in its wing: today, everyone thinks they can be a photographer. For me, photography should remain an art. (Gaspard Vincent TatangFootnote5)

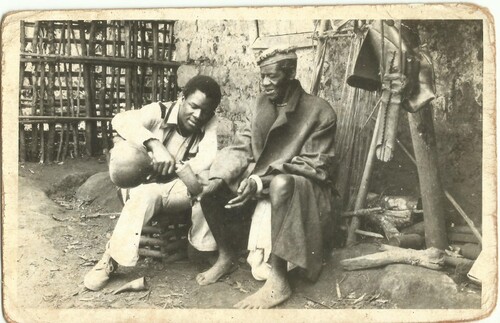

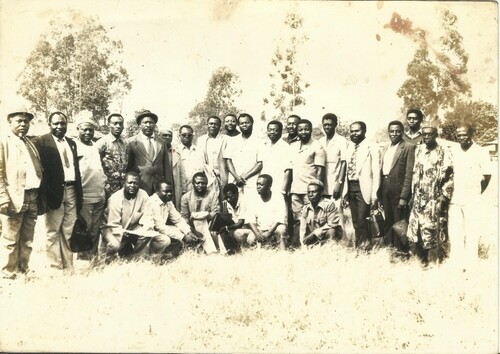

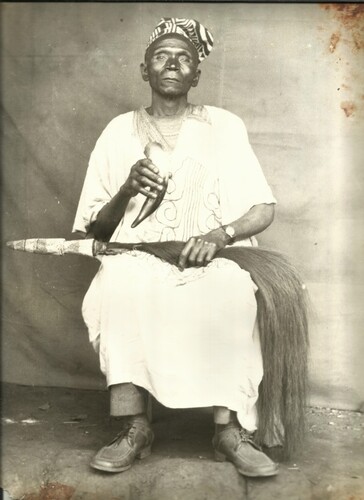

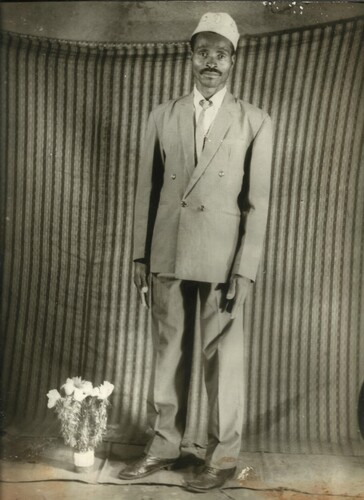

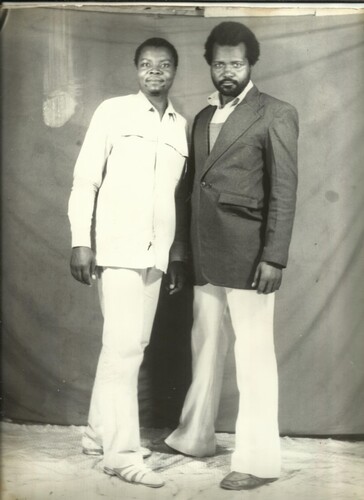

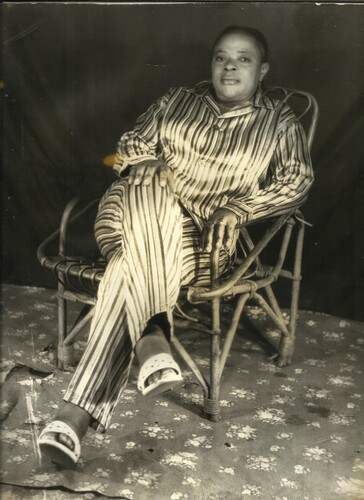

Tatang took a correspondence course in photography with Eurelec which was based in France. From 1974 to 1977, he was president of his high school's photography club. Some two years later, he covered events and wrote occasional pieces for the local newspaper Les Nouvelles du Mongo, of which Bernard Essomba was then the editor-in-chief. Tatang became so intrigued by photography that he neglected his studies, which led to him resitting the 3rd form. His older brother bought him an expensive camera—more precisely, he says, a smart camera that cost 150,000 FCFA, Footnote6 an automatic Konica with an interchangeable lens. During school vacations, he would take the camera back to his village to shoot. One key moment from that time was the opportunity to photograph Malam Doukou, who, after spending a long period of time in the sultanate of Bamoun, had helped introduce the Kana dance to Batcham. Below are a few images selected from Gaspard Tatang's own collection of his work ( –).

In 1978, Tatang interrupted his studies and embarked on a country-wide photographic tour of Cameroon. After this, in 1979, he moved to Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, where he toyed with the idea of becoming a professional journalist. In 1983, he landed a job with the magazine Journal Perspective, covering such events as the unsuccessful Coup d'Etat (6 April 1984).

I was in a sort of no-man's land, neither with the loyalists nor with the rebels. Several of my works from elsewhere were hanging in the museum. A state-certified nurse was living in the same house as me. I altered his white blouse, cut out a red cross, and stuck it on the shirt. I can say honestly that I was overwhelmed as a first-aid worker. In my bag, I carried my camera, which I could shoot and film through a hole in the bag; it was an autofocus camera. I'd done so many photos by then that I knew what focal width was needed. I knew at what distance I could snap something. I salvaged several cartridge cases from that event that I still have, because I feel that they are a keepsake that I should preserve.

Asked if he was afraid of being arrested, Gaspard replies in the negative. He notes that he had already shot events for many newspapers, and that every event deserves to be recorded. I took enormous risks because it wasn't easy. It was local newspapers that published my photos such as Le Patriote and L'Africain magazines. I still have some copies of Le Patriote, he says.

Tatang regrets that he no longer has any negatives or full prints from the time of the April 1984 putsch. But even if I don't have those photos anymore, I do have some contact sheets from that era. They're still useable because a journalism image isn't like a studio image, where you have to add a bit of powder in order to produce the photo. The goal of the contact sheet is to reduce waste. We bill it to the client because a lot of clients still can't understand that many customers aren't well-placed to judge a photo, he adds. When a photo was not as good as it could be, Tatang would not deliver it to his client. He remembers bickering with his wife over a photograph which she thought was a waste of paper. I threw away so many photos that I didn't find beautiful, but that she thought were beautiful, because I wanted a photo stamped as my work to be … something special, he says.

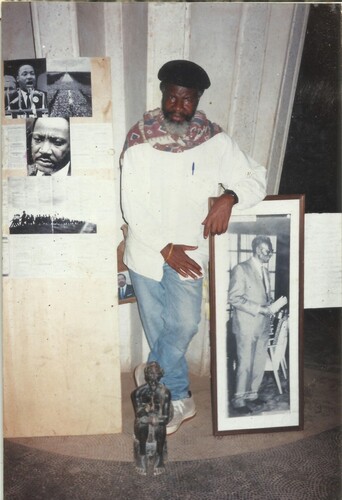

Since 1986, Tatang has been conducting research in Egyptology and cultural history. That same year, Cheikh Anta Diop spent some time in Yaoundé. Tatang describes that occasion as like a dream, because he wondered if a man like the Cheikh really existed in flesh and bone like himself. He was not sure, so he decided to meet the Cheikh. When he arrived at the Hôtel des Députés, where the Cheikh was staying, he was disappointed by one thing: the pseudo-intellectuals had already formed a tight inner circle and were full of themselves. I came in my jeans, my tennis shoes, and my beret, Tatang recalls. He told the men of his desire to meet the Cheikh, but they were against the idea and dismissed him as crazy. Yet a few minutes later, he said, he glimpsed the Cheikh who was around 10–20 metres away, and instinctively waved to draw his attention. The Egyptologist came over and took him by the hand. We went up to his suite in the Hôtel des Députés. He sat down and said, “My son, what can I do for you?” I told him, “The fact that you picked me out means that you've already given me everything, but, just as my appetite is strongest when I eat, I would really like to talk more with you.” So he gave me an appointment at SOFITEL that night, where I was able to photograph him.

I talked with him for a good twenty minutes … among those pseudo-intellectuals, there were some who watched us and understood nothing of what we said. He really taught me how to think, and so, in a way, did Martin Luther King: those two Africans carved and illuminated my path. If, in a single instant, just 20% of Africans could follow that path, we would no longer be asleep on our backs. Looks at what's happening in Ivory Coast, what's happening in Libya; at the same time as these events, people here drank champagne, ate rich food, spent the Cameroonian taxpayers' money, up to billion FCFAs, to celebrate 50 years of [Cameroonian] independence.

Yet, Tatang, for his part, feels that Cameroon is more dependent now than it was 60 years ago. He asks himself how a country that no longer possesses anything resembling the sovereignty of a modern state can believe itself to be independent. I knew SONEL (the National Electricity Society) in the past, when we had a say in its operations, but today, those who own SONEL (AES-SONEL [now American-owned]), can get rid of it if they want to. It's their cash drawer that matters, not your mouth …

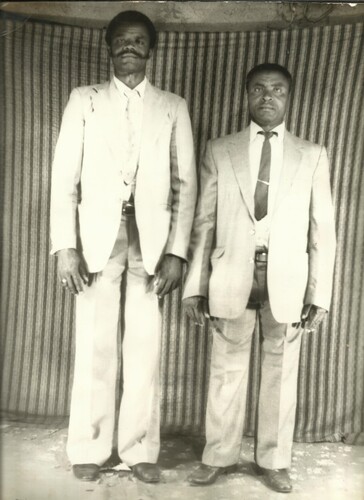

Tatang has always envisioned the existence of a Pan-African museum of photography. He did not know all of the Pan-African leaders, but he went to great lengths to have their images. He adds that in that era, photography permitted him a decent lifestyle. He notes that he made beautiful photos and was much sought-after. According to him, there were not many photographers who made such beautiful photos or who had such demanding clients. As proof, he states that the photo below cost his client 45,000 FCFA: beautiful things merit their price, he remarks.

Tatang stresses that he has many souvenirs. For him, what is interesting is that these souvenirs are not strictly material. As he explains:

Today, I've showed [my portrait of] Cheikh Anta Diop everywhere. There are artists who are very famous today because of my photos. Take the example of the choreographer Bartelo, and Ekeme who directed the Olympic Club in Bastos in Yaoundé. The photo that you saw on the wall there, in the open-air show at the French Cultural Center—I took that photo. I showed it in at least four countries: in Ivory Coast, in Cameroon, on the island of Madagascar, and in Senegal. For other countries, the photo went there, but I didn't accompany it.

From 1994 to 1998, Tatang participated in several photography and journalism exhibitions, both in Cameroon and abroad. He was one of the artists invited to MASA, the Marché des Arts Africains (Market of African Arts), which included a photography exhibition. At least seven countries were represented, and he represented Cameroon. After the show, he staged another exhibition, and the newspaper Le Jour d'Abidjan published his photos of the group Nyamakalas from Guinée Conakry and the group N'dai N'daï. The extract in shows one of the photos the paper published, entitled “D'une soirée à l'autre [From one party to another]”.

Tatang also showed his works twice in Dakar. The first time, he was invited to an international symposium organized to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of Cheikh Anta Diop's death. For that event, he mounted an exhibition at the Cameroonian Ministry of Information and Culture. He also put on a show at Cheikh Anta Diop University, and still has pamphlets and workbooks from these exhibitions. He also remembers the appeals of his fellow photographers who invited him to present in the Caribbean, and regrets letting himself be distracted from pursuing this.

I was careless, but I can always restart things with them, because I can say, without bragging, that I am the photographer who has the last beautiful images of Cheikh Anta Diop. In Cameroon, there was the photographer from the Ministry of Information and Culture who had covered the symposium, and there was the Institute of Human Sciences, but no one could take as many photos as I could. I went straight to the interviewer. It's a shame that the interview wasn't published. It wasn't published because in 1990, with my bad experience—I call it my bad experience in parentheses because I was lucky to escape from Chad with my skin; my boss at the time created problems that could have cost me my life and my money—I put the interview aside. Since that date, I've decided … I've put certain photos and documents underneath an embargo, so to speak, to show that I will only publish them in a paper of which I am the director of publication.

Tatang says that he possesses an official declaration about his work, but laments setting the bar for publishing his work at what he recognizes is a utopian level—in short, for setting that bar at very high heights. He believes that had he started at a lower level, for example, with a “tabloid” pamphlet of twelve pages, he would have had ample time to scale the art photography ladder. Yet he also feels that it is not too late, and that his interview with Cheikh Anta Diop, given its depth and relevance, should be published despite that it has been more than twenty years since the interview itself took place. Nevertheless, he feels that the interview remains relevant, because the warning the Cheikh sent to African youth is applicable today: “If you youth do nothing”, the Cheikh said, “you will live in hell in Africa, even though God made Africa to be paradise”.

Explaining the circumstances and reasons as to why he took photos of celebrities, Tatang declares that:

At the time, it was sufficiently complicated, even for a well-recognized photographer, to take photos of people of that stature here in Cameroon. Under Ahmadou Ahidjo, you had to make phone calls [to take photos], and in order to make those calls, you had to submit an application with a photo and a photocopy of your identity card. So I went to work for a newspaper, and with that affiliation I had access to people and events. But for the past 15 years, I've refused to take such photos for personal reasons. Today, the photos I take are for my research work (he is working to publish a tourist guide).

Remembering the difficulties he encountered as a professional photographer, Tatang reveals that he was once questioned during “Les années de braise” [the “Burning Years”, a reference to a particular period of social and civil unrest in the early 1990s] by a colonel of the SED (Secrétariat d'Etat à la Défense camerounaise [Secretary of State for Cameroonian Defense]).

I was held in custody for 24 hours because I had been taking photos of the damage caused when a bus was set on fire. He stopped me for questioning. I said, “No, this is my work; tomorrow, people will need to know what happened, and if we don't have images, we'll have to have really beautiful writing to make up for it. You have to understand, we're living in a civilization of the image; these days, the image practically speaks for itself.” He didn't understand at all … I spent 24 hours at SED, and then he released me. He took the film that was in my camera, but forgot that I had already taken other films, he recalls.

Despite these difficulties, Tatang remains firm:

When you have passion, love for something, he insists, no matter what the difficulties, you just can't give up, although I admit that I'm not someone who's familiar with discouragement … I have a problem: it's that I don't know how to be afraid. Maybe that's the reason why I'm still alive … I'm convinced that fear makes more trouble than trouble itself. I've been assaulted by bandits several times, been held up at gunpoint, but with my cold blood I always succeeded in getting out of the situation. He also feels that his profession steered him clear of a materialistic lifestyle. I missed out on a lot of things because of photography, but I'm satisfied morally, because my travels around the world are due in large part to photography, he emphasizes.

He points out that he is a relatively self-taught man (apart from his early correspondence course) and had the privilege of reading the lectures of Cheikh Anta Diop.

Tatang says that photographers today are primarily interested in the profession for financial reasons. Because they place money before art, Tatang feels that such photographers are not capable of creating photographs of the same caliber as his. Yet he does not blame them for acting as they do. When asked if his profession brought him happiness, he has much to say ( and ):

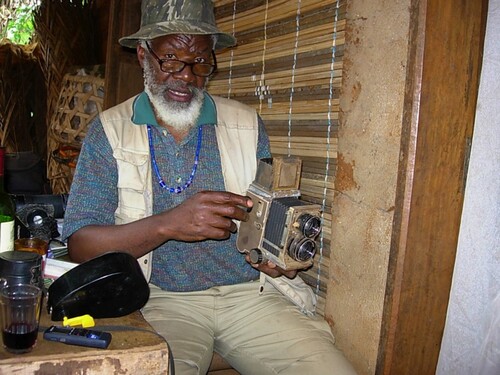

… there are people for whom happiness is perhaps a little bit of wine that they drink, there are those for whom happiness primarily consists of money … for me, it's something totally relative. When I say that to people, as I often do, they usually reply, “He says that because he's penniless.” But by what standard am I poor? Someone who owns lots of things but has an empty head has nothing … I prefer my photos. I still have faith in photography. I can't lie to you—I'm slow to attach myself to digital photography, because it pains me. I'm nostalgic because photography today has become like a free-market: it's a free-for-all, everybody nowadays takes photos … if you ask a photographer, talk to him in technical terms, he'll be completely lost. He can't keep up with the conversation. Happily, I'm currently setting up a museum within the framework of l'Institut Panafricain d'Etude et de Recherches Appliquées pour la Renaissance Africaine de Batcham (IPERARABATCH [The Pan-African Institute for Study and Applied Research on the African Renaissance in Batcham]). All the photographic accessories that I've purchased over the years will be housed in this museum. For example, it will house the densitometer that I've had since 1979.

Tatang was not the only photographer working in Batcham. Among the contemporaries of Tatang were Photo-Samuel (also known as Major), Edouard Fofou (alias Photo-Edouard) and Martin Mbou. While Mbou and Major are deceased, Fofou was still available for interviews in late 2012 and it is to him that we now turn.

Edouard FofouFootnote7 entered photography in 1975, and was trained by Jean Mermoz, who was from Bangang. The latter had himself learned photography from a Nigerian who had taken up residence in the Cameroonian town of Melong. Fofou came to photography through an unusual route: when he was born, his father did not formally register his birth. Despite the lack of documentation of his age, Fofou was able to attend primary school, but in his second year of middle school had to leave for lack of a birth certificate. His father then suggested that he take up photography, but Fofou, angry at being expelled, went to various colonial plantations in search of farm work. During this period, in 1960, his father died.

First he worked for COC in Foumbot where he amassed some small savings at their bank. It was the death of his father that made Fofou decide to leave the COCFootnote8 and travel to Niabang (Melong), where one of his childhood friends was working. There, he was recruited to work on a small farm that was part of a larger coffee plantation owned by the colonialist Gremelor. Armed with some small savings from this work, Fofou remembered his father's suggestion and apprenticed himself to a local photographer from Bangang village known as <Jean Mermoz>.Footnote9 The apprenticeship cost him 25,000 FCFA—then the equivalent of thirteen and a half months of work. When his photography apprenticeship ended, Fofou returned to work at the farm in Niabang. The money Fofou earned from this farm work permitted him to travel to Douala to purchase a full set of photographic materials. While there, he also bought a five-year old Yashica camera for 25,000 FCFA as well as an old enlarger for 30,000 FCFA; equipped with these, he returned to Batcham to start his own photographic studio. In addition to his work as a studio photographer, he also worked as an itinerant photographer. Fofou still has some of the first photos he took, though most of these early photos are now in his children's possession ( –).

For Fofou, the arrival of colour photography brought about the decline in black-and-white photography:

We filmed and we were the ones who fostered development and instruction … in short, we were the ones who did everything. When the color photography cameras came out, our activity started to decrease. But what really pushed me into quickly abandoning the profession was that I realized that my eyesight was starting to weaken.Footnote10

Fofou attributes the decline in his visual acuity to his profession, in particular to dark room photographic processing. However, remembering black-and-white photography, he says:

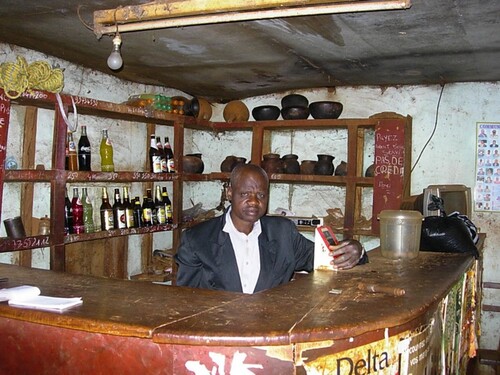

As I was an orphan, it's thanks to photography that I built my first house. And this, in turn, allowed me to gather the dowry for my first wife. After that, I built a take-away stand next to my photo studio where I sold alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks.

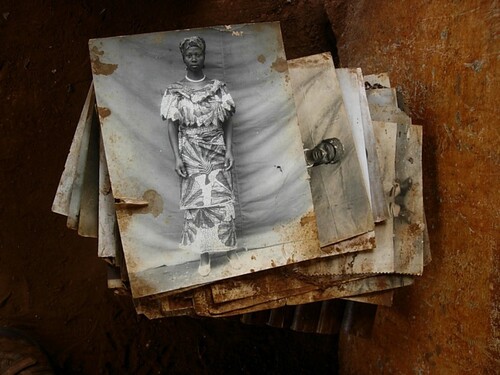

Fofou also notes that in conjunction with the decline in black-and-white photography, the equipment itself has also aged. I gave my equipment to an acquaintance so that he could use it to make ends meet, he says, adding that that he knew only one other person, now deceased, who was interested in black-and-white photography. For Fofou, people today are not truly interested in photography; instead, they are only attracted to it because the act of taking a photo has become very easy. The climate of Western Cameroon poses conservation difficulties for photographs, and Fofou has seen his negatives decay in storage. Nevertheless, he still possesses an impressive collection of black-and-white photos commissioned but never collected by his clients ( and ).

The third Batcham photographer I consider here is Michel Kenne. He was born around 1941 in Batcham. His father, Mathias Tsakeng, a former envoy first of the Germans, then of the Franco-British alliance, chose to send his son to a Western school. Yet after finding no success in an educational environment, Kenne left the school in 1963. Gaston Tsakeng, Kenne's older brother, had already discovered the advantages of the photographic profession, and suggested to Kenne that he begin an apprenticeship in the profession. Gaston put his brother in touch with a professional photographer, Joseph Keino, who was then based in Dschang but had been born in the village of Baleveng. This was hard work. Kenne struggled particularly with a technical part of his training: handling the film in the dark room. He had to be very strict with the development timings else the negatives were either too dark or too light. However, he succeeded in mastering it and at the end of his apprenticeship in 1970, Kenne opened his first studio in Mbouda, where the photographer Jacques Toussele, (known as Photo Jacques), also worked. In the same year two of Jacques's pupils (known as Photo Pascal and Photo K. Etienne; the latter was also trained by Keino), also began to work that in Mbouda and the neighbouring villages. Kenne received his materials from Douala and Bafoussam, and sold surplus stock to other photographers and some amateurs.

In 1988, Kenne returned to Batcham-Ville, where he opened another studio. He remained there until 1994, when he moved to Batcham-Chefferie (Quartier Baguié). This was because of the decline in black-and-white photography, as well as the traditional duties associated with his role as a lineage senior. Despite the decline of interest in photography, Kenne continued to take some photographs after his return to the village centre. However, he says, his (informal) supplier of materials, jealous of his success, stopped supplying him. At this point Kenne then took up subsistence farming which he continues to practice in 2014.

Kenne is nostalgic for the prosperous years of black-and-white photography. When my father died in 1957, this compound was idle; it was the revenue that photography brought me that enabled me to rebuild it and run it. He also regrets the disappearance of black-and-white photographic equipment: if this equipment hadn't disappeared, I would have been in this profession to the point where I would rather have gone completely blind before I abandoned it, he laments.

According to Kenne, the abandonment of black-and-white photography was due to the scarcity of its equipment and the proliferation of colour film that students could buy at low cost.

We used to count on holiday periods to bring us money: students would take a lot of photos during those times as well as during exam grading periods. Schools would ask us to take identity photos, and that also brought us in lots of money. We also took photos for adult identity cards. It was the government agencies responsible for identification that made us withdraw from this market, because now it's the police who are in charge of taking photos for identity cards and passports. During holiday periods, young people are now going to their rich friends with cameras in order to take photos; they don't go to studios anymore. And so that's how the black-and-white photo lost so much importance that I had to abandon it, he says.

Michel Kenne, following his photographic training, preserved all of his film negatives and ordered them chronologically. Unfortunately, one conservation difficulty he has encountered since retiring has been rodents: mice have eaten away a good part of his archives. Furthermore, while the photos he stored in closed boxes remain in good shape, the photographs that were once on display in his shop are now covered in dust ().

Conclusions

All three of the photographers considered here have preserved some of their photographic work, but only Tatang seriously hopes that his work will be archived. Their example stands as a message for all such photographers, that they need to conserve their own photographic collections (slides, negatives, videotapes, photographs, newspapers, letters and rare documents). In order to avoid the physical deterioration that has already affected much of their collections, the material needs conservation, to be stored in safe boxes and indexed appropriately. Ideally multiple copies should be made, some of which should be sent to the Cameroonian National Archives and local universities as has been done with the Jacques Toussele archives.

In his introduction to this special issue, Zeitlyn (Citation2015b) discusses Paula Amad's analysis of a French film archive. She summarizes an archive as “a bet against the future” (Citation2010, 1). In effect the archivists are betting that the records stored will be found useful at some point, for some purpose. The concern here is that the bet may never be laid, and the processes for archiving the photographic material that remains after the exigencies of village storage may never get underway. Although very different from Le Febvre's discussion based on research in the Negev in Israel (Citation2015) the final result is the same.

As we have seen these three photographers have had quite different careers, yet at the outset there was little to distinguish them from one another. Their histories exemplify the arbitrariness of fame and international success: why do many know of Seidou Keita and not of Gaspard Tatang? In the article I have concentrated on the careers of these three photographers, as examples of the creators of potential archives. In the introduction I mentioned some biographical approaches to history, ranging from Ginzburg's micro-history to Herzfeld's reflections of his conversation and discussions with his friend, the novelist Andreas Nenedakis. The cases I have considered here allow us to raise the issue of success since biographies are usually only written about the famously successful (or infamously criminal). It may be that the photographers I have considered have more in common with Domenico Scandella (Menocchio) the Sixteenth-Century miller whose opinions Ginzburg could trace through the chance survival of a heresy trial than with contemporaries such as Nenedakis. Dilley (Citation2014) explored the archives of family and state in writing his life of the West African colonial administrator Henri Gaden, but one wonders how that would read when contrasted with, for example, the (yet to be written) biography of a somewhat earlier colonial officer Northcote Whitridge Thomas, (1868–1936) who having served in the British Colonial Service in Nigeria and Sierra Leone in the early years of the twentieth century left under a cloud during the first world war, and whose subsequent career is unclear. Success or its lack has no official place in historical methodology except when it is implicit: we study people who achieve prominence, which is usually a synonym for success. Even in subaltern studies and studies of “the everyday” which ostensibly are about those who are not successful in worldly terms, we still tend to study the leaders and not the followers. The studies of protest and revolutionary movements, my own included, tend to focus on the leaders and opinion shapers for these are the individuals who leave archival traces. In terms of the contrasts used in Papua New Guinea the focus continues to be on the “Big Men” (with archival traces) not the “Rubbish Men” (without archival traces) for all that the bulk of the human population falls into the latter category. Be that as it may, to return to the immediate theme of this paper, the cases I have presented are examples of potential archives, the “roads not taken” that could have led to archiving, the penumbra of possibility which archival studies should acknowledge: for every document included there are many that have not made it across the portal, that have not been accessioned.

Finally, we should return to the arguments of the pioneering authors cited in the introduction, and the suggestion that the work of these photographers and their work should be taken as a resource for historians and anthropologists.Footnote11 Like many other small artisans from the early years of postcolonial African states such photographers remain a relatively understudied topic of study and their work provides the raw material for a wide range of historical and anthropological research on the display of self and the visual environment. Indeed, we can see the work of these photographers as exemplifying the struggle to be modern in a recently independent African state, both in their individual biographies and in the photographic work they created during their careers. These photographers have documented modernity in the course of creating it.

Translated by Elizabeth Durham.

Notes

[1] There is a large literature on biography and life writing in anthropology and history. Zeitlyn (Citation2008) provides an introductory survey.

[2] For more information on the origins of this village, see Kenne Fouédong (Citation1991).

[3] For discussion of the creation of this subdivision, see Tatsitsa (Citation1996, 3).

[4] For more information on Bamiléke emigration toward Nkongsamba, see Guiffo (Citation1992, 105).

[5] Note: the interview with Gaspard Tatang was conducted in French.

[6] Then worth 3000 French Francs, c $700 in 1975.

[7] Edouard Fofou, personal interview, 5 November 2012, Batcham.

[8] The Compagnie de l'Ouest Cameroun (COC) was the largest coffee farm in West Cameroon (2400 ha) owned by group of French investors. They also ran a savings bank (see Uwizeyimana Citation2009, 333).

[9] The nickname borrows the name of a French aviator from the 1930s.

[10] The interviews with Edouard Fofou and Michel Kenne were conducted in Ngyemba (the local Bamiléké dialect). I transcribed the Ngyemba and then translated it into French.

[11] A first step is the recent thesis (Mboulla Citation2014).

References

- Amad, Paula. 2010. Counter-Archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn's Archives de la Planète, Film and Culture Series. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bajorek, Jennifer. 2010. “Photography and National Memory: Senegal around 1960.” History of Photography 34 (2): 160–171. doi: 10.1080/03087290903361480

- Buckley, Liam. 2008. “Photography, Elegance and the Aesthetics of Citizenship.” In Visual Sense: A Cultural Reader, edited by Elizabeth Edwards and Kaushik Bhaumik, 183–192. London: Bloomsbury.

- Dilley, Roy. 2014. Nearly Native, Barely Civilized: Henri Gaden's Journey through Colonial French West Africa (1894–1939), African History. Leiden: Brill.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, ed. 1992. Anthropology and Photography 1860–1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with The Royal Anthropological Institute.

- Geary, Christraud M. 1986. “Photographs as Materials for African History: Some Methodological Considerations.” History in Africa 13: 89–116. doi: 10.2307/3171537

- Geary, Christraud M. 1990. “Impressions of the African Past: Interpreting Ethnographic Photographs from Cameroon.” Visual Anthropology 3 (2–3): 289–315. doi: 10.1080/08949468.1990.9966536

- Geary, Christraud M. 2013. “The Past in the Present: Photographic Portraiture and the Evocation of Multiple Histories in the Bamum Kingdom of Cameroon.” In Portraiture and Photography in Africa (African Expressive Cultures), edited by J. Peffer and E. L. Cameron, 213–252. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 1980. The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Guiffo, J. P. 1992. Nkongsamba: Mon Beau Village. Yaoundé : C.I.A.G.

- Haney, Erin. 2010. Photography and Africa. London: Reaktion Books.

- Herzfeld, Michael. 1997. Portrait of a Greek Imagination: An Ethnographic Biography of Andreas Nenedakis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hirsch, Eric, and Charles Stewart. 2005. “Introduction: Ethnographies of Historicity.” History and Anthropology 16 (3): 261–274. doi: 10.1080/02757200500219289

- Kenne Fouédong, S. P. 1991. “Tradition historique de la chefferie Batcham (Bamboutos) des origins à 1903.” Master's thesis in History, Yaoundé, University of Yaoundé I.

- Le Febvre, Emilie K. 2015. Contentious Realities: Politics of Creating a Photographic Archive with the Badū an-Naqab in Southern Israel. History and Anthropology. 10.1080/02757206.2015.1074900

- Mboulla, Damboum Alimatou. 2014. Les Photos de Tatang Gaspard Vincent de Batcham (ouest cameroun): Inventaire, Archivage et Contribution a l’écriture de l'histoire. Mémoire, L'Université de Maroua, Cameroun.

- Morton, Christopher. 2012. “Double Alienation: Evans-Prichard's Zande & Nuer Photographs in Comparative Perspective.” In Photography in Africa: Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by Richard Vokes, 33–55. Woodbridge: James Currey.

- Tatsitsa, J. 1996. “U.P.C.: Tensions sociales et guerre révolutionnaire dans la subdivision de Mbouda de 1950 à 1965.” Master's thesis, Yaoundé, University of Yaoundé I.

- Uwizeyimana, Laurien. 2009. “Après le Café, le Maraîchage? Mutations des Pratiques Agricoles Dans les Hautes Terres de l'Ouest Cameroun.” Les Cahiers d'Outre-Mer 62: 331–344. Accessed November 17, 2014. http://com.revues.org/5675. doi: 10.4000/com.5675

- Werner, Jean-François. 1996. “Produire des Images en Afrique: l'exemple des Photographes de Studio.” Cahiers d'Etudes Africaines 36 (1–2): 81–112. doi:10.3406/cea.1996.2002

- Zeitlyn, David. 2008. “Life History Writing and the Anthropological Silhouette.” Social Anthropology 16 (2): 154–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2008.00028.x

- Zeitlyn, David. 2010. “Photographic Props/The Photographer as Prop: The Many Faces of Jacques Toussele.” History and Anthropology 21 (4): 453–477. doi:10.1080/02757206.2010.520886.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2015a. “Redeeming Some Cameroonian Photographs: Reflections on Photographs and Representations.” In The African Photographic Archive: Research and Curatorial Strategies, edited by Darren Newbury and Christopher Morton, 61–75. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2015b. “Looking Forward, Looking Back.” History and Anthropology. 10.1080/02757206.2015.1076813.