ABSTRACT

Starting from the idea that race is an assemblage, the author investigates two instances of touch in anthropometry. Firstly, the detailed instructions for mechanized measurements of “the living”. Second, the practices involved in actual measurements of Papuans in Dutch New Guinea during two expeditions in 1903 and 1909.

Touch

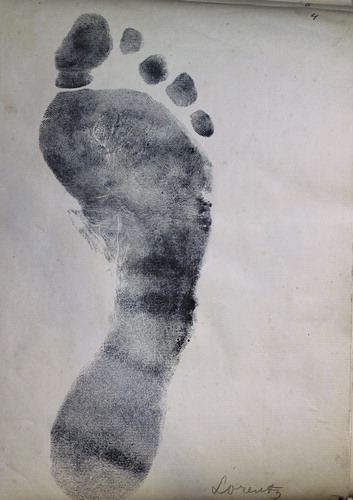

After a long day at the Dutch National Archives looking for traces of the physical anthropologists and their anthropometrical work in the archives of H. A. Lorentz—who was involved in three famous, early twentieth-century expeditions in Dutch New Guinea—I walked over to the nearby Royal Library to pick up a publication by one of them, L. S. A. M. von Römer. To my surprise I was not handed printed matter, but two stacks of loosely bound paper, one with handwritten, sloppily completed anthropometry forms used during the 1909 expedition and the other consisting of original foot and handprints (Römer Citation1909). A hand reaches out to me, almost in greeting. Over 100 years later someone is gesturing to me from a faraway place. There is a surreal realness to this. I can touch the ink this man from another world once touched. This moved my inquiry further into the history of anthropometry ().

Thinking of the latter has often made me imagine the strange encounter of bodies, a meeting between people who did not know each other, who—literally and figuratively—hardly spoke each other’s languages, and who nevertheless touched. Anthropological historian Peter Pels proposed taking the aspect of “tact” in contact more seriously in studies on ethnographic fieldwork encounters. As opposed to a visualist perspective or a focus on “conversation” (based on speech and the audible), which both allow distance, contact and material mediation would necessarily also touch the fieldworker’s body (Pels Citation1999, 20–29). Contact as a concept and a focus on material practices thus allows for a critical history of anthropology that literally affects the anthropologist. Following Pels’ call for attention to the materialities, practicalities and embodiedness of colonial contact, this article will highlight the elaborate anthropometrical efforts made precisely to obliterate subjective embodiment.

In her rich and innovative La mesure des sens, a study of nineteenth-century anthropological scientists’ work on the senses, Nélia Dias describes how touch—the tactile sense—was scientifically analyzed at the time. Touch came close to vision in the scientific hierarchy and was even often seen as the basis for all senses. Touch could observe volume, structure, form, temperature, weight, it could provoke pain and pleasure, it could be passive and active, even manipulative. With regard to bodies, touch could probe, palpate or penetrate. This active element was particularly valued for scientific experimental purposes. But active touch did not necessarily exclude being touched: touching and being touched could occur at the same time and to varying degrees (Dias Citation2004).

With Dias’ description of nineteenth-century notions of touch in mind, I want to describe the encounter between physical anthropologists and the people they measured as an effort to touch others without being touched. Often trained as physicians, physical anthropologists would of course not avoid physical contact. However they tried avoiding to be affected by strictly, precisely distributing the active and passive elements of touch. To this end, anthropometric touch had to be “mechanized”. This required an enormous anthropometrical apparatus. Adopting an actor-network-theory (ANT) approach as recently proposed in this journal by Bennett, Dipley, Harrison and others, this apparatus of anthropometry can be seen as an assemblage of skills, people, material objects, knowledge, “centers of calculation” (Latour Citation1986), infrastructures of travel and more (Bennett, Dibley, and Harrison Citation2014; Dibley Citation2014).

At the time, anthropometry was meant to study race and racial difference, among other things. Recently, the history of racial anthropometry in Oceania has attracted increased attention and started to include both practicalities in the field and the actorship of the people measured (Douglas and Ballard Citation2008, Citation2012; Howes Citation2013; Roque Citation2010; Schüttpelz Citation2005; Sysling Citation2013; Sibeud Citation2012). Anthropometric photography has also been studied in depth (Edwards Citation1992, Citation2006, Citation2014; Morris-Reich Citation2016). These studies provide a rich context for a “praxeographical” analysis of race in which race is considered an enactment (Mak Citation2012; M’Charek Citation2013; Mol Citation2002). I will thereby follow Amade M’Charek’s proposal to overcome the dichotomy between race as biological fact or race as societal fiction or “construction” by arguing how “race does not materialize in the body, but rather in relations established between a variety of entities, including bodies” (M’Charek Citation2013, 434). Therefore, rather than analyzing historical theories on race and racial classifications that reveal different, conflicting or shifting (European) ideas about race, I aim to examine which version of race came into being within a particular network of (human and non-human) actors. I will analyze the instances of “anthropometrical touch” as nodes of relating entities, together enacting a particular version of “race”. However, because these instances are themselves related to other nodes (where race is also, but differently enacted), I will outline a chain of nodes of which only two are central to this article: anthropometrical touch as it was envisioned and taught at Rudolf Martin’s influential school of anthropology in Germany (Morris-Reich Citation2013), in relation to anthropometrical touch in the field in Dutch New Guinea during the first decade of the twentieth century.

Two scientific expeditions to Dutch New Guinea will be considered, one to the Northern part which was led by Arthur Wichmann in 1903, and one to the South led by H.A. Lorentz in 1909. The anthropologist on the first expedition was G.A.J. van der Sande, a Dutch colonial army physician who trained in physical anthropology with Rudolf Martin for a year in 1901. He was very dedicated to the latter and referred to him as “my friend”. Part of the German school that strictly separated physical anthropology from ethnography, Rudolf Martin was mainly interested in improving anthropometrical methods. His 1200 page manual from 1914 was re-edited and published until after the Second World War and is still used today (Morris-Reich Citation2013; Proctor Citation1988). Reading his meticulous instructions is very helpful when trying to understand how “touch” was mechanized. In turn, Van der Sande instructed his successors by writing extensive letters to Lorentz who would become the leader of the next expeditions to Dutch New Guinea.Footnote1 In 1909, colonial army officer L.S.A.M. von Römer joined Lorentz’s expedition as its anthropometrist.Footnote2 Van der Sande promised Lorentz that he would also give Von Römer “practical training”. Together, Martin’s instructions, the forms Von Römer filled in, Van der Sande’s publication and letters, Lorentz’s diaries and Wichmann’s report on the 1903 expedition allow me to expose the apparatus of anthropometry these Dutch physical anthropologists used in order to re-embody the allegedly disembodied “mechanical” objectivity of anthropometric touch (Martin Citation1914; Römer Citation1909; Van der Sande Citation1907; Wichmann Citation1917).Footnote3

Selfless scientists

The work of Rudolf Martin, known as a the liberal physical anthropologist who strove for a neutral, standardized, universal method of measuring human variation, has recently been much more critically assessed by Amos Morris-Reich (Morris-Reich Citation2013, Citation2016, 49–63). His argument concentrates on the fact that Martin made a major contribution to the scientific status of anthropometry without preventing his pupils from using this scientific authority to underwrite their racist agendas. Moreover, Morris-Reich shows how Martin’s photography, whilst theoretically meant to solely constitute the basis for precise measurements, appears in Martin’s work in such a way that it strongly suggests racist classifications (for example, the juxtaposition of a chimpanzee, a person from the Ainu people in Japan and a Khoikhoi child) (Morris-Reich Citation2013, 510–511). Moreover Morris-Reich has revealed that Martin never addressed the fundamental problem of racial sampling. He did not explain how “racial types” could be sampled as a category without being based on already existing categories or “trained judgment” (Daston and Galison Citation2007; Morris-Reich Citation2013, 491, 507–513). Following up on this critical stance towards the ostensibly liberal and neutral Martin, this article critically engages with measuring practices during colonial expeditions, concentrating on the enactment of race implied and embedded within such practices.

Morris-Reich and others have also pointed out the way in which Martin’s use of anthropometric photography related to the epistemic ideal that Daston and Gallison labelled “mechanical objectivity” (Morris-Reich Citation2013, 490–491; Sysling Citation2013, 142–147). These epistemic ideals of mechanical objectivity came with a specific ideal of the scientific self, according to Daston and Galison: a self-negating self (Daston and Galison Citation2007, 192–252). To analyze this ideal within anthropology adds a complicating factor however: how does the selfless scientist encounter the human-as-object? One of the problems of the epistemic ideal of self-negation, pointed out by Simon Schaffer and later described and analyzed meticulously by Nélia Dias, is the functioning of the scientist’s body during observation (Dias Citation2004; Schaffer Citation1992). According to Dias, anthropologists became self-conscious of their own bodies, their embodied and limited vision, touch, smell and other senses. Anthropological attention therefore turned to examining the scientists’ senses. How could one measure (and take into account) a scientist’s ability to see, for example? And how could scientists account for the differences between their observations? The ideal of self-effacement, the scientist as a transparent instrument for observing the objective world, therefore conflicted with this attention to the embodied character of the senses.

There is another question, however, which Dias mentioned but did not further explore. In contrast to the other senses, touch and taste imply physical contact with the object sensed. You are literally also touched yourself (Dias Citation2004, 62). How could scientists act as disembodied, selfless observers of other people’s bodies during examinations involving touch? This ambiguity of touch—as both active and passive—is of interest here. It can be related to the opposing roles of a scientist as both passive observer and active experimenter, that emerged from the 1860s onwards. Daston and Galison cite Claude Bernard:

Yes, no doubt, the experimenter forces nature to unveil herself, attacking her and posing questions in all directions; but he must never answer for her nor listen incompletely to her answers by taking from the experiment only the part that favors or confirms the hypothesis. (Daston and Galison Citation2007, 243)

Avec Bernard, les fondements de la médecine expérimentale passent par un nouveau régime sensoriel qui n’est plus celui du regard “neutre” du clinicien et qui présuppose l’action sur l’objet d’observation. Ainsi, l’expérimentateur doit, selon lui, “pouvoir toucher le corps sur lequel il veut agir, soit en le détruisant, soit en le modifiant, afin de connaître ainsi le rôle qu’il remplit dans les phénomènes de la nature”. (Dias Citation2004, 59)

Daston and Galison describe the ethical-epistemological ideal of the selfless scientist as a psycho-drama in which the ideal scientific subject has to fight his own will (Daston and Galison Citation2007, 231). By doing so, they draw a vivid picture of what this scientific epistemological ideal entails in the (ideals concerning) scientific personae. However, in doing so they also picture it as an individualized ideal. It is as if the scientist’s heroic struggle to juggle disciplined observations and creative impulses is lonely. I would like to invoke Donna Haraway’s concept of “situatedness” here to bring to mind that the ideal of selflessness is not only personal, but also embedded in a much larger political and scientific apparatus (Haraway Citation1988). As I hope to show in this micro-study of mechanized anthropometric touch, the effort to create “objective” facts (about racial difference) by erasing subjectivity whilst measuring humans entails the creation of a huge anthropometric apparatus that both actively manipulates bodies and creates an illusion of “mechanical” and universal observation. It thereby attempts to filter out subjective variations between individual scientists. This “apparatus of anthropometry” thus enacts race in a specific way, whilst making it seem selfless and unsituated. It is this apparatus that I intend to make tangible here ().

Figure 2. Lorentz’s footprint (Römer Citation1909).

I consider the apparatus of anthropometry an assemblage or network of human and non-human actors. As such, many different nodal points—which can be explored in many different ways—could serve as a point of departure for analysis. I will take the act of anthropometric touch as the central node to which I will stick quite closely. I will first explore the preparations in Europe by examining the development of instruments and the instruction and training of physical anthropologists. I will then, after having roughly outlined the preconditions for contact between Dutch and local people, focus on the negotiations and other practices needed to gain access to Papuan bodies, and on the type of anthropometric contact established. Elsewhere, I hope to extend this analysis of the “micro-politics of colonial power” (Edwards Citation2014) to other crucial nodes in this anthropometrical enactment of racial difference such as the infrastructure which enabled these expeditions and involved all kinds of local or regional people or the “centres of calculation” at which the data collected was elaborated, displayed and shared (Bell and Hasinoff Citation2015; Fabian Citation2000; Latour Citation1986).

Preparations in Europe

A form of touch

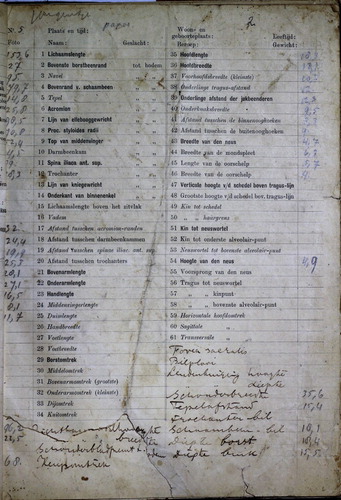

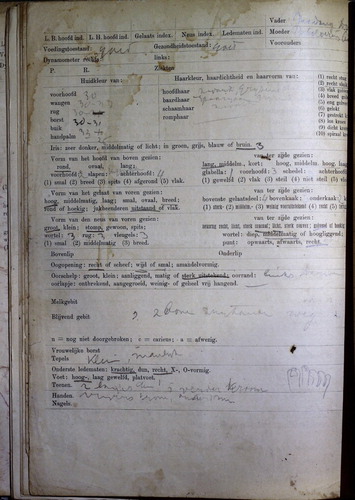

Besides the hand and footprints, the source closest to the moment of touch is the bundle of stained, crumpled partially completed forms I found in the Royal Dutch Library. There is a certain immediacy to them, as the forms were present and completed during or just after the measurements were taken. I took these forms as my starting point to get as close as possible to the actual moments of touch and to unravel the apparatus behind them. The form was designed by Dutch anthropologist Van der Sande, who published extensively on the anthropometric measurements he took of forty-three Papuans during the first scientific expedition to Dutch New Guinea (Van der Sande Citation1907).Footnote4 Comparison to other forms and questionnaires and to Martin’s comments on forms makes it clear that Van der Sande incorporated many of Martin’s ideas about forms in this Dutch version (Broca Citation1865; Luschan Citation1906; Martin Citation1914; Virchow Citation1875).

Compared to the form his teacher Rudolf Martin designed ten years later for the anthropometric laboratory in 1914, Van der Sande’s was quite modest. Yet, an enormous range of measurements were actually (meant to be) taken. The front consisted of “quantitative measures” and had two columns: on the left thirty-four measurements for various body parts, on the right twenty-seven different measurements for the head. To provide an impression, the left column measurements included:

Distances from the ground to, for example: the upper edge of the breastbone, the navel, the upper ridge of the pubic bone, the nipple, the tip of the middle finger, the knee

Body length in a seated position

The distance between the crests of the iliac bones

The lengths of the upper and lower arms as well as hands

The circumference of, for example, breasts, pelvis and thigh.

Measurements of the head (the most important ones, printed in bold) were:

Head length and head width

Distance between the cheekbones

Width of the nose

Vertical height of the skull above the tragus

Chin to the base of the nose

The reverse consisted of “qualitative measures”, often with multiple choice answers.

These consisted of:

Information about parents and ancestors, health and illnesses

Measurements from the dynamometer (strength in both hands)

Skin colour measured at forehead, cheek, back, breast, stomach and palm

Hair colour, thickness and type on the head, face, pubes, torso; a choice of ten different hair types was provided

Colour of the iris

Shape of the head from above, in profile and from the front

Shape of the nose in profile and from the front

Shape of the ocular cavity

Shape of the ear

Information on teeth, female breasts, the shape of the extremities: feet, toes, hands and nails

The very first conclusion that can be drawn from this relatively modest anthropometric form is that it fragmented the human body into numerous parts. Moreover, the focus on the body’s surface is remarkable. The latter constitutes the interface between the physical and the social body. To concentrate on the body’s surface was specific to the anthropometry of the living and differed substantially from the increasingly inwardly oriented “medical gaze” of modern European medicine (Foucault Citation1963). As I have argued for cases of hermaphroditism, in clinical practice this turn inwards happened much later than in Foucault’s classic study that is, only after surgery became more or less a clinical routine (Mak Citation2012). It is precisely the relationships and translations or “travelling” between visible bodies and “internal” bodies that remains an important issue in cases of sex and race categorization (M’Charek Citation2013). The focus on surface in the anthropometry of the living can be understood as an attempt to objectify and de-familiarize everyday, ordinary observations of visible human difference. Taken individually and from a myopic perspective, visible body parts lost their direct everyday social meaning, becoming alienated. A similar argument has recently also been made concerning Bertillon-based fragmentation of portrait photography for anthropometric use (Ellenbogen Citation2012; Morris-Reich Citation2016, 36–41).

Furthermore, the form shows how bodies became encoded, primarily by numbers. According to Dias, late nineteenth-century anthropologists became increasingly distrustful of descriptions; the latter being viewed as subjective as they used inconsistent comparisons such as chestnut-brown or the size of a pigeon egg, etc. Descriptions were to preferably be replaced by numbers in order to become objective, exchangeable and quantifiable. Measuring instruments would ideally enable anthropologists to transform the subjective descriptions of their visual impressions into objective, quantitative data (Dias Citation2004, 167–170). Van der Sande’s warning to use Broca’s colour chart with its rows of numbered squares depicting skin tones demonstrates this point perfectly.

It is absolutely necessary to bring a skin color chart (…). When you check the literature on N. Guinea, time and again you notice how visitors who do not mention the numbers of a color chart, who apparently did not carry such a chart and mostly described the color only from memory or provide a rough estimate, indicate shades that are much too dark: dark negro black, deep charcoal black and such terms. If numbers from Broca’s scale are mentioned you will generally notice that it is precisely the darkest numbers of all the horizontal color rows that are never mentioned; this clearly establishes the benefit of this system.Footnote5

In the instructions Martin provided for its use, he explains that the colours on the chart are surrounded by the white of the paper. In order to make a good comparison, a piece of paper with a square hole the size of the coloured areas of the chart should be made, which could then be held against the skin of the body measured. Von Römer, who indeed mentioned Broca’s numbers on some forms, therefore had to hold a piece of paper up against the forehead, cheek, back, breast, stomach and palm of his subjects.

Just looking at external appearance—which created distance between subject and object—was no longer good enough: subjective descriptions had to be transformed into measured numbers or standardized options. This measuring procedure involved the manipulation of the body as well as the touching thereof, often mediated by instruments. Paradoxically then, distancing oneself from subjective impressions involved bringing the bodies to be measured much closer to the scientist’s body. The instructions for measuring body length clarify how much effort was invested in taming this paradox.

Body length

Even though Von Römer filled in the forms very sloppily (see and ), body length was usually recorded. His sloppiness stands in sharp contrast to the detailed instructions and high standards set for the measuring instruments developed in Europe. Instructions and manuals for anthropometry of the living had developed over time and were shared between various European countries. The first extensive manual was written by French anthropologist Paul Broca (Broca Citation1865); in Germany, several editions of Neumayer’s manual for travellers, Anleitung zu wissenschaftlichen Beobachtungen auf Reisen contained instructions for anthropometrical methods by Rudolf Virchow and Felix von Luschan respectively (Luschan Citation1906; Virchow Citation1875). Van der Sande used a form developed by Rudolf Martin, which he later adapted for Dutch use (Van der Wichmann Citation1903). In 1914, Martin published his meticulous, 1200-page manual for anthropometry. According to Morrison-Reich, Rudolf Martin’s work was primarily aimed at perfecting and standardizing these measurement protocols in order to make measurements from all over the world comparable (Morris-Reich Citation2013). As we saw above, this is precisely the lesson Van der Sande took to heart. So, even whilst Martin’s instructions and instruments were probably not as developed in 1903 as they were in 1914, it can be stated that Van der Sande’s methods were already based on Martin’s obvious attempts to heavily particularize and standardize anthropometrical methods.

Figure 3. Two-sided form designed by Van der Sande and filled in by Römer (Citation1909).

Figure 4. Two-sided form designed by Van der Sande and filled in by Römer (Citation1909).

First of all, the instruments were carefully designed. Martin’s description of the measuring rod or the “Anthropometer”, which you could buy from Hermann in Zürich for 53.60 Marks in 1914, provides an impression:

The Anthropometer consists of an easily dismantled metal tube with millimeter calibration from 0 to 2 m. Along this tube glides a solidly-guided metal slide, with a horizontally adjustable, similarly calibrated metal ruler that tapers to a point at the end. A window has been cut in this slide’s upper edge—which is situated level with the point of the metal ruler—that allows the height of any point of the body from its standing or sitting surface to be read. (Martin Citation1914, 112–113)

Such precision instruments were therefore designed, produced and traded in close cooperation with anthropometrical scientists. Other prominent anthropologists such as Broca (Citation1865) and Bertillon (Cole Citation2001) also had their names linked to particular instruments. Martin explains why good instruments are so important:

All anthropological instruments (…) should be useable both in the laboratory and during travel in all zones and climates. Therefore for their construction not just material, but also handiness, weight, capacity for disassembly, portability and so on have to be considered. (Martin Citation1914, 109)

The anthropometer is just one example of the many instruments and devices designed, produced and traded for anthropometrical use. The 1928 edition of Martin’s manual contains an extensive list of instruments with the names of their manufacturers (Martin Citation1928, 122–144). Of course, travellers could not take that many instruments with them, so Martin also provided instructions for travellers’ measurement kits. Martin designed a set of two sailcloth cases for travellers. One of them contained calipers, a sliding compass, a tape measure, a pencil and an instrument for measuring the height of ears (“Ohrhöhenadel”). The other contained an anthropometer. He also recommended charts for measuring eye, hair and skin colours, a “dynamometer” (for measuring hand strength) and an inkpad for finger, hand and foot prints. All had to be nickel-coated, packed in tins and lightly oiled (Martin Citation1914, 202–204). This would enable anthropological apparatus to travel. What is more, it should afford the “travelling” of the data gathered—making it comparable across contexts and times thanks to calibration.

The mechanization of touch also involved the precise discipline of the measuring bodies. The links between measuring person’s body, instruments, other devices and the person measured ideally enabled the desired mechanical measurements. Simon Cole aptly described Bertillonage’s instructions as “a meticulously choreographed set of gestures” (Cole Citation2001, 34–35). Martin’s instruction for measuring the length of the body starts with a careful positioning of the body to be measured (see ):

To have their body measured the individual has to stand up straight against a flat surface, either leaning with buttocks and back (not the back of the head) against a wall or stake or without touching the surface, naked or in very light underwear, without shoes. Their heels should touch also touch the wall. The axes of the feet should be directed slightly outwards. The arms should be stretched as much as possible and should hang down beside the body with the palms flat against the side of the thighs. If there is no flat surface the individual has to be stood on a low box or perhaps on an assembled portable board of no less than 70 cm square which should be perfectly horizontal; to be checked with a spirit level. If there is no vertical surface, you should observe the full stretching of the body very keenly and position the anthropometer for measuring body length not in the front, but behind the individual. (Martin Citation1914, 104)

The measuring itself was to be carried out as follows:

You position yourself on the right-hand side, the anthropometer exactly in the median sagittal plane in front of the person to be measured; [you] lead the instrument’s slide down with your right hand just until the pulled out slide rests gently on the skull, which should be controlled by the left hand. One has to make certain that the anthropometer is kept as vertical as possible, without pushing the slide too hard on the skull, because the individual (in particular children) will otherwise give in to the pressure and the measurement will turn out too low. (Martin Citation1914, 132–133)

One has to use both eyes and use a hand to feel. The latter often is capable of establishing slight unevenness or bends of surfaces which the eye cannot see or only under favorable lighting. Sight and touch therefore have to support each other. I search for the points in the median sagittal plane either with the pad of the right index finger or with the medial ridge of the thumb’s pad, according to what is needed. Bilaterally available measuring points can best be felt with both hands, because in that way one can quickly orient oneself and notice existing asymmetries. (Martin Citation1914, 106–107)

The meticulous precision with which Martin prescribes the procedure for every single measurement might seem a bit overdone. Martin warned, however, that every single little difference in procedure, the tiniest variations in which reference points were used for measurements, would make the worldwide comparison of data impossible (Martin Citation1914, 57–59). In Martin’s anthropometry, the “selflessness” of the scientist also meant: to measure in exactly in the same way as others, not to “stand out”. Only if all anthropometrists who studied living people around the world measured in exactly the same way, using the same instruments, would it be possible to compare measurements of all the world’s “races”. Calibration was therefore deeply connected to the idea of a universal eye, an imaginary, neutral place from which “all races” could be discerned by comparison. Far from being imaginary and neutral, however, this eye in fact had a concrete location: in Europe, the colonial centre where—at the time—the scientists were based who travelled the world and where the data returned to “centres of calculation”.

In practice, this ideal of standardization was hardly ever completely achieved. Van der Sande had studied for a year with Rudolf Martin in Zürich and wrote to Lorentz that this was far too short. However, he must have been one of the best trained travelling anthropometrists at the time, particularly when compared to, for example, the French travellers, army physicians and traders Sibeud describes, who often took barely a week to learn the skill (Sibeud Citation2012). Van der Sande acted as an instructor for his successor by writing letters with instructions to Lorentz, but he also promised to train Von Römer. They planned two days of training: on the first day, Van der Sande would show how to measure using Von Römer and the following day Von Römer would practice the measurement techniques on Van der Sande. However, the second day Von Römer was ill and he never did have another day of training.Footnote6 Even though Von Römer had a physician’s skills, he could hardly have been able to carry out measurements in a machine-like manner.

In touch

Racial bodies related to function

Even though the Wichmann expedition resulted in a series of large, internationally published, richly illustrated volumes there have been almost no substantial historical studies of the results until now. What is more, in contrast to many recent studies that aim to “unpack” the often hidden practices which were utilized during expeditions to collect data and materials (Bell, Brown, and Gordon Citation2013; Bell and Hasinoff Citation2015; Fabian Citation2000; Roque Citation2010; Konishi, Nugent, and Shellam Citation2015), the single, substantial publication available on the Wichmann expedition still exudes strong admiration for the “adventures” of the expedition’s members who filled in “blank spaces” without critically addressing either the work of the many expeditions’ non-Western members nor the exploitative colonial foundations enabling them (Duuren and Vink Citation2011, 47–59). I intend to unpack the practicalities of anthropometric measuring during this expedition, with the same intention with which authors such as Fabian, Bell, Hasinoff and Roque have exposed the practices of collecting ethnographic and anthropometric material. I will thereby concentrate on the data gathered instead of on materials or photographs collected.

The Wichmann expedition was a Maatschappij ter Bevordering van het Natuurkundig Onderzoek der Nederlandsche Koloniën initiative (a Dutch society for the advancement of the scientific study of the Dutch colonies). It was co-organized with the “sister organization” the Indisch Comité [Indonesian committee] located in Batavia [Jakarta]. The ministry of colonial affairs joined the enterprise with the explicit assignment to investigate prior coal discoveries. Finally, and not unimportantly, a trader in “naturalia” [exotic natural objects] (probably birds of paradise) was talked into joining the expedition. His knowledge of the local situation, language and culture proved to be very important. In all probability, he made use of the informal structures created by the divide-and-rule practices surrounding the hunting and trading of birds of paradise (Hille Citation1906, 453).Footnote7 Scientific interests and (possible) colonial exploitation motivated the expedition, whereas a thin infrastructure of hunting and trading practices enabled entry to the area. Moreover, the speech by the director of the Batavian botanical gardens and a member of the “Maatschappij” M. Treub at the start of the expedition, reveals how much the enterprise was seen as a competition with England and Germany, who were considered far ahead with respect to research in New Guinea (Treub Citation1903). This makes the expedition the first in a series of which the later ones are described in the catalogue of the exhibition Race to the Snow (Ballard, Vink, and Ploeg Citation2001). Elsewhere, I hope to analyze in detail the enactment of race within the huge organization and networks of the expedition and its local infrastructures that over 100, mostly colonized people were involved in. Here I will show how this expedition involved touching between two Dutch physicians and Papuan people.

Contact

How did Van der Sande and Von Römer get in contact with Papuans? During the 1903 Wichmann expedition, local Papuans acted as carriers, interpreters and guides. Sometimes Papuans provided the expedition with food and a lot of contact was made through the exchange of ethnographic artefacts for trade goods such as knives, axes, beads and tobacco. This was entirely different during the 1909 Lorentz expedition, where contact with Papuans was solely established on the coast. As soon as the expedition started to travel inland, it only encountered deserted Papuan huts and villages, with the exception of one (anxious and nervous) encounter with a Papuan village to which they were very urgently invited to stay overnight (an encounter Von Römer did not experience as he had stayed behind at their basecamp “Alkmaar”). The atmosphere of fear, distrust, anxiousness and the care taken to ensure military back-up may have had to do with an “incident” in the same region two years previously during which a Papuan was killed. Lorentz had been severely reprimanded by the colonial administration for digging up the buried body and bringing it to the Netherlands for anthropometrical research as the administration feared that this would cause tension and trouble.Footnote8 The outspoken difference in contact with the Papuan people accounts for the huge difference in the quality and quantity of anthropometric data Van der Sande and Von Römer brought home. Other historians of the anthropometry of living people have noted similar differences caused by circumstances surrounding contact (Schüttpelz Citation2005; Sysling Citation2013).

Van der Sande stayed in Metu Debi at Lake Sentani for about six weeks and submitted a meticulously detailed report on his anthropometrical findings, to which I will return below. Von Römer never published his findings, which ended up as the bunch of forms I happened to find in the Dutch Royal Library. In fact, most of his completed measurements involved not Papuans, but the expedition’s coolies. Much more can be said about the networks and infrastructures behind the expeditions in relation to anthropometry, but, for now, it suffices to know that in Van der Sande’s case, a decades-old infrastructure of trading with Europeans probably helped a great deal in convincing Papuans into serving as anthropometric objects of study.Footnote9 To get a little closer to anthropometric practices “in the field” I will have to restrict myself to Van der Sande’s published and unpublished reports, and his correspondence with Lorentz.

Van der Sande lived in a part of the trader’s building with the other Europeans, only he had a backdoor that “natives” could come in through if they had any ailments (Wichmann Citation1917, 149–151). He was available as a physician on a daily basis: “My patients often showed themselves very satisfied with the results of the medical treatment, to which I devoted much time and trouble nearly every day (…)” (Sande Citation1907, 318–319, see also 276). This was probably the most important basis for getting into close contact with the Papuans and allowed Van der Sande to observe their bodies.

The long chapter Van der Sande wrote on physical anthropometry was only the last chapter of a voluminous and beautifully illustrated ethnographic study. In a kind of transition from ethnography to anthropometry, he carefully described the functioning of bodies in Papuan society, keenly observing many aspects thereof, reporting about on the latter with authority and distance:

Belching is not retained, neither does it offend, flatus only when the smell is offensive. The act of defaecation is always committed in secret; also for mixturiation one disappears or turns away from the company. Squatting on the stage of a pile dwelling built in the water, the urine is simply allowed to run away between the laths of the flooring. (315)

He also describes squatting, sitting and standing, carrying weights and walking. The distanced tone—observations from a position that seems unrelated to the people described—disappears for a moment when he relates: “The female Nagramádu carriers of the expedition, after a day’s march, rubbed their bodies and limbs with the leaves of a shrub, the species of which I do not know, growing in the forest” (316). What he knows about these bodies is related to how they functioned in the expedition: these women carried the expedition’s loads.

After describing swimming and climbing in a similar manner, Van der Sande starts to slip in reports on body functions he had actively measured or tested. He measured the difference in strength between the right and left hand with the “dynamometer”, and followed this with observations of right or left-handedness in daily life whilst “eating a sago dinner” (316). The smooth textual shift between observation and test is also nicely illustrated by how Van der Sande continues:

“Pain as a rule is dreaded and many of my patients were so accustomed to their chronic ulcerations, which were the prevailing complaint, that they were unwilling to endure any pain on that account. The Papuans I came into contact with appeared very capable of withstanding heat and cold. Local freezing of the skin with ethyl chloride only caused surprise. (317)Footnote10

Measuring in practice

How did Van der Sande persuade Papuans to have themselves measured? Apparently, in his clinical practice he used local anaesthesia with ethyl chloride (see above) and full anaesthesia, especially when treating the many ulcers: “My patients liked the western art of surgery, if not too painful, and were willing to be anaesthetized with chloroform; they said I made the people dead, without stopping the heartbeat, and after the operation made them live” (327). Their bodies would have been perfectly inert, which made me wonder whether perhaps Van der Sande abused the situation to also perform anthropometric measurements. He does not say so and one thing argues against it: all the people he measured were also photographed. They all have a number and a name, and in his reports on the data he sometimes refers to those numbers when he mentions specific or exceptional data. So even if he conducted these measurements on anaesthetized bodies, he also must have gained consent to take pictures.

However, the anaesthesia may have provoked awe for Van der Sande’s power, as the above quote indicates, and Van der Sande did not eschew theatricality:

I remember an instance when I had narcotized with chloroform a Sentáni boy to operate on a large wound in his foot. At the moment when I began to remove the granulation tissue with a sharp spoon, to prevent too great a loss of blood in a quick, apparently cruel manner, the father of the boy uttered a plaintive “sobä!” (from the Malay sobat = friend). I could very well understand this and appreciated it in this father. Not so the spectators, his fellow-villagers, squatting round;—with a general, loud “sis!” they silenced the man, afraid that for the sake of the father I should interrupt this, to them unusual and attractive spectacle. (317)

When settling at Asé in June 1903, I expected to see a large number of patients turn up for medical help from the neighbouring villages; however what I had not foreseen was that not a single stranger would risk himself in this village. (278)

As a physician, Van der Sande could therefore almost literally use a physical language to communicate with the Papuans, treating the painful ulcers they came to show him, impressing them with his powers to make people dead and bring them back to life. The Papuans apparently trusted him to handle bodies: touching them, cutting them, administering medicine and creating miraculous effects. However, this communication was very restricted. How did he instruct them when he wanted to measure them? It turns out there was an interpreter in Tobadi, the Papuan village closest to Metu Debi, called Waru, who had spent a year in Ternate where he had learned Malay. Two other Europeans learned to speak the local languages quickly, according to Wichmann, but Van der Sande was not among them. Van der Sande therefore must have been dependent on Waru for his communication with Papuans. The trading infrastructure with regular shipping to Ternate, the trader’s island Metu Debi and the existence of an experienced Tobadi interpreter were therefore of crucial importance (Sande 1907, 314–315).Footnote11

The expeditions brought plenty of trade goods: tobacco, beads, knives, mirrors, iron axes and penny whistles. It is clear that Van der Sande also used these to seduce Papuans into having themselves measured, but he does not mention these practices much. At one point, whilst discussing the difficulty of measuring boys and women, he observes: “Giving presents to children did not help either; according to Papuan custom such things are immediately confiscated by an elder brother or father. Hardly did one give a boy a penny whistle and one sees his father practicing on it”.Footnote12

Van der Sande only measured four of the twelve Papuan carriers who were taken to Ternate on the European steamer at the end of the expedition. Being in service therefore did not guarantee Van der Sande permission to measure the Papuans. Yet, in Von Römer’s case, most of the measurements were taken from the expedition’s Dayak coolies. Given the serial numbers of the form, he measured them after the failed and incomplete attempts at measuring Papuans.

Anthropometric touch

How did Van der Sande’s anthropometry touch and manipulate Papuan bodies? We have already seen how he administered ethyl chloride to test their reactions to cold and heat. The next clearly anthropometrical measurement described is skin colour:

I owe to the reader this practical hint: without previous washing a correct opinion of the colour of the skin can seldom be obtained. After washing with soap half of a young man’s face at Horna, this proved 1 or 2 shades of Broca lighter than the other half. All the natives of the interior, but especially the Sekanto and the mountaineers, looked dirty. (…) I could not take any plaster casts or imprints of the hands without a previous washing. (329)

Next, Van der Sande took ink prints of eighteen people’s hands and feet; ninety prints in total. He used thick ink, thinly rolled out over a failed, used glass negative with a rubber roller:

(…) then let the delinquent (! GM) put his finger on it under moderate pressure, then print the finger onto a piece of paper close to the edge of a table. You can also have the finger lift up at the top somewhat to get a good long print, and also have the finger roll over its longitudinal axis over the paper to get a large print (…). To get the whole palm of the hand or sole of the foot, I rolled the roller over the hand or sole of the foot until all embossed wrinkles were black and then pressed them onto paper. Think to bring some tough paper for this purpose (emphasis in original).Footnote13

What follows, at least in the case of nine right-handed people, is the meticulous measuring of fingernails:

I determined the lineal as well as the bent breadth of all the finger-nails of the right hand, 3 times also of the left. The bent breadth was almost the same with the corresponding fingers of both hands, but the lineal breadth, which on the right (from thumb to little finger) amounted to 14.5, 11, 12, 11, 9 m.m., was on the left from ½ to 1 m.m. less. (331)

The next topic, Papuan hair, was certainly among Van der Sande’s favourites. He wrote several pages about the specific curling patterns of the tufts and in his letters give detailed instructions of how to get samples in the hope of having his earlier findings confirmed:

But then the collector should only collect hair samples from people who neglect their hair, so that the natural spiraling has not suffered from combing, attachments of clay, treatment with lime, smoke or braiding. Secondly, the hair should preferably not be cut with scissors, but shaved off close to the skin (emphasis in original).Footnote14

Another extensively discussed issue is the plaster casts of the teeth; Van der Sande’s letters again testify to the extent to which material, techniques, routines and skills were employed to be able to acquire data. But here we also know a little more about the Papuan’s responses.

(…) the dental spoons I used for making plaster casts of the teeth, which were not designed for the Papuan built of the jaws and teeth, probably caused an unpleasant sensation. After having made a couple of casts of a boy, his playmates disappeared rapidly when the topic of anthropological measurement was raised.Footnote15

He tried to fix the problem to no avail: “(…) even the extension of 1 cm soldered on was not always sufficient. They also were too wide at the back, and after the lengthening they could, in some instances, not be introduced into the mouth” (339–340). Trying again on board the ship with the Papuan coolies:

Again I experienced great difficulties with making casts of the teeth, because the dental spoons used in Western Europe did not fit. (…) The future researcher will save himself effort and disappointment, and his Papuan objects unpleasant pain if he takes this into consideration.Footnote16

At the end of his report on the anthropometry of the living, Van der Sande related the results of body and head measurements in seventeen different tables, from body height to width of the nose, without mentioning (problems with) the measuring procedures.

All in all, Van der Sande tested Papuan skin-sensitivity with ethyl chloride; made Papuans wash their hands and washed (some of their) faces; held pieces of paper up against several places on their skin; rolled fingers through ink and printed these onto paper, rolled ink over their hands and feet, and asked them to press these onto pieces of paper; meticulously measured their fingernails; took hair samples and inspected facial, pubic and armpit hair; he used dental spoons to enter their mouths and made them bite into plaster; he made plaster casts of hands and feet, and, finally, he had them stand and sit for some time to take at least seventeen precise measurements, probably very much in line with how Martin had instructed him to do so. These were intense, manipulative ways of touching bodies, which for the time being were rendered passive, inert and non-functional in the ordinary sense.

Connecting two instances of anthropometrical touch

This article focused on two nodes in the colonial scientific networks enacting race at the start of the twentieth century which both concerned anthropometric touch: the instructions for taking anthropometrical measurements in the classic manual by Rudolf Martin and the employment of a prior version of such instructions during two expeditions in Dutch New Guinea during the first decade of the nineteenth century. The analysis of Martin’s instructions shows how anthropometric touch strove to achieve mechanical objectivity by meticulously prescribing instrument design, measuring situations and procedures as well as the development of automated routine. Standardization of every aspect of the measurement aimed to guarantee the opportunity for data to “travel”, to be compared and combined. At the time only Western empires organized expeditions that physical anthropologists could take part in and Western universities constituted the centres where collected, standardized data were compared. So, whilst suggesting disembodiment, objectivity and universal overview, the aim and actual opportunity for comparison implied a fundamentally Western colonial vantage point.

The immense apparatus involved in the expeditions that enabled anthropometrical touch becomes evident when you consider the practices involved in measuring Papuans in Dutch New Guinea in more detail. The measurements involved the momentary subjection of the measured body, which had to be approached up close, disciplined into holding still, touched, manipulated and sometimes literally appropriated. This measuring enacted bodies as docile, fragmented, objectified parts, detached from their ordinary functions. The thereby collected data only enact race in relation to the European (in particular Rudolf Martin’s) physical anthropological programme that aimed to create a worldwide comparison between such standardized measurements. After all, the descriptions and measurements as such, disconnected from such a comparative scientific programme, do not “tell” much.

The two nodes analyzed here show how the colonial macro-politics of the global comparison of populations through standardization connected to a micro-politics of rendering Papuan bodies inert and fragmented during meticulously detailed measurements. Each temporary touching gesture by a single European physician towards a single Papuan therefore contained both the enormous apparatus of the expedition and the Western ambition of worldwide overview and comparison.

Epilogue: a Papuan answer

There is only very fragmentary evidence available as to how the measured Papuans experienced these procedures or which meaning they gave to them. Curiosity, awe, pain and fear were noticed as well as both willingness and unwillingness to undergo the procedure in exchange for goods. The difficult, fragile negotiations necessary to gain access to bodies for the purpose of measurements shows that Papuans were definitely actors in the process who may have profited from the latter from their own point of view. According to Van der Sande’s own ethnographic observations, Papuan body manipulations such as the wearing of wigs or other people’s hair, painting the skin, tattoos and scarification are often related to either social relations or marked important, ritual moments in life. To provide an example that might indicate how removing tufts of hair could have been interpreted, I quote his notes about wearing other people’s hair:

(…) the use of wigs occurs in commemoration and adoration of blood or

close relations. Thus a dark haired young man may be seen with a wig of grey hair, obtained from the dead body of his father, an elderly widow with a wig of dark hair, obtained from the early deceased husband. But it appears however that the married woman also sometimes wears hair of the still living partner and even generally, as a further mark of esteem of her master, must have her own hair shaved. It does not appear that mothers are thus remembered by their children, nor wives by their widowers, neither do the fathers appear to wear the hair of their deceased children and there is never any reason for an aged man to wear a wig. For, this must be noticed in the first place that here originally mixed feelings as well of attachment, as of respect and submission are brought to a visible expression. (Sande Citation1903, 64)

But I owe the reader one Papuan response. Among Van der Sande’s ethnographic observations, under the heading customs and government, is a section on “contact with strangers”:

After the first contact, an invitation to squat down is to be considered in Papua Talandjang as a proof that you are trusted, and if you squat down voluntarily this is appreciated on your part as a proof of friendly confidence. On Lake Sentáni they appeared to appreciate this highly, and then all squatted down around me with a contented: “angên numbô”. (Sande 1907, 277)

Acknowledgements

The Max Planck Institut für Wissenschafsgeschichte in Berlin provided me with an excellent environment in which to start this study with a visiting scholar grant in 2014 and I particularly appreciated the stimulating presence of Daniel Midena, Judy Kaplan and Eric Hounshell. As always, it has been a pleasure to work with Titus Verheijen who corrected my English. I also wish to thank Annemarie Mol, Rebecca Jordan-Young and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and critical readings of earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8.

2. In the Netherlands, L.S.A.M. von Römer is better known as the author of the first Dutch defence of homosexuals. I intend to write elsewhere about the relationship between his interest in sexology and anthropometry.

3. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File Nos. 8, 11, 38, 43, 44.

4. “Different forms” was the working title of my project at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, September–October 2013 that compared various anthropometrical practices. See for an analysis of forms as paper technology, Saskia Bultman and Mak (forthcoming).

5. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Letter from Van der Sande to Lorentz, Amsterdam, 22 February 1906; See also Bultman and Mak (Citationforthcoming). See Martin (Citation1914, 184–186) for an extensive description of color measuring techniques; Dias (Citation2004) for measuring colour and colour scales, 75–112, 139–166; Howes (Citation2013, 133–138) for a detailed discussion of the use of Broca’s scale in anthropometry two decades before Van der Sande’s research.

6. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Letter to Lorentz, Soerabaia, 11 June 1909.

7. I would like to thank my student Timo de Jong for this reference and many more useful insights into the trade in birds of paradise in his master’s thesis.

8. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 38.

9. I would like to thank my student Timo de Jong for having provided me with many of the details about the trade and shipping networks the Wichmann expedition was part of.

10. Measuring sensibility to pain, cold and heat was a procedure already used by Lombroso in criminological physical anthropology (Horn Citation2006). To my knowledge, Van der Sande had no special device to measure sensitivity.

11. This is also noted by Van der Sande himself, in his chapter on trade and communication, 314–315.

12. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Ethnografisch verslag, 10 June 1903–July 1903.

13. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Amsterdam, 29 November 1906.

14. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Amsterdam, 22 February 1906.

15. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Ethnografisch verslag, 10 Juni 1903–Juli 1903.

16. NL-HaNA, Lorentz, 2.21.183.51, File No. 8, Ethnografisch verslag, 28 Juli–4 September 1903.

References

- Ballard, Chris, Steven Vink, Anton Ploeg, and Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen. 2001. Race to the Snow: Photography and the Exploration of Dutch New Guinea, 1907–1936. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute.

- Bell, Joshua A., Alison K. Brown, and Robert J. Gordon. 2013. Recreating First Contact: Expeditions, Anthropology, and Popular Culture. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

- Bell, Joshua A., and Erin L. Hasinoff. 2015. The Anthropology of Expeditions: Travel, Visualities, Afterlives. New York: Bard Graduate Centre.

- Bennett, Tony, Ben Dibley, and Rodney Harrison. 2014. “Introduction: Anthropology, Collecting and Colonial Governmentalities.” History and Anthropology 25 (May 2015): 137–149. doi:10.1080/02757206.2014.882838.

- Broca, Paul. 1865. Instructions générales pour les recherches anthropologiques à faire sur le vivant. Paris: Société d’anthropologie de Paris, G. Masson.

- Bultman, Saskia, and Geertje Mak. Forthcoming. “Forms of Identity: Paper Technologies in Dutch Anthropometric Practieces around 1900.”

- Cole, Simon A. 2001. Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. 2007. Objectivity. New York: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press.

- Dias, Nélia. 2004. La mesure des sens: les anthropologues et le corps humain au XIXe siècle. Paris: Aubier.

- Dibley, Ben. 2014. “Assembling an Anthropological Actor: Anthropological Assemblage and Colonial Government in Papua.” History and Anthropology 25 (May 2015): 263–279. doi:10.1080/02757206.2014.882831.

- Douglas, Bronwen, and Chris Ballard, eds. 2008. Foreign Bodies Oceania and the Science of Race 1750–1940. Canberra: ANU E Press.

- Douglas, Bronwen, and Chris Ballard. 2012. “Race, Place and Civilisation.” The Journal of Pacific History 47 (3): 245–262. doi:10.1080/00223344.2012.713577.

- Duuren, D. A. P. van, and Steven Vink. 2011. Oceania at the Tropenmuseum. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 1992. Anthropology and Photography, 1860–1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the Royal Anthropological Institute, London.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2006. Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford: Berg.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2014. “Photographic Uncertainties: Between Evidence and Reassurance.” History and Anthropology 25 (May 2015): 171–188. doi:10.1080/02757206.2014.882834.

- Ellenbogen, Josh. 2012. Reasoned and Unreasoned Images: The Photography of Bertillon, Galton, and Marey. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Fabian, Johannes. 2000. Out of Our Minds Reason and Madness in the Exploration of Central Africa: The Ad. E. Jensen Lectures at the Frobenius Institut, University of Frankfurt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 1963. Naissance de la clinique; une archéologie du regard médical. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599.

- Hille, J. W. van. 1906. “Reizen in West-Nieuw-Guinea.” Tijdschrift van Het Koninkllijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genenootschap 2e serie (23): 451–540.

- Horn, David G. 2006. “Making Criminologists. Tools, Techniques and the Production of Scientific Authority.” In Criminals and Their Scientists, edited by Richard Becker and Peter Wetzel, 317–336. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Howes, Hilary Susan. 2013. The Race Question in Oceania A. B. Meyer and Otto Finch Between Metropolitan Theory and Field Experience, 1865–1914. Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang.

- Konishi, Shino, Maria Nugent and Tiffany Shellam (eds.). 2015, Indigenous Intermediaries: New Perspectives on Exploration Archives. Acton: ANU Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 1986. “Visualization and Cognition. Thinking with Eyes and Hands.” Knowledge and Society. Studies in the Sociology of Culture, Past and Present 6: 1–40.

- Luschan, Felix von. 1906. “Anthropologie, Ethnographie Und Urgeschichte.” In Anleitung Zu Wissenschaftlichen Beobachtungen Auf Reisen in Einzel-Abhandlungen. Band II, edited by Georg Balthasar von Neumayer and Dritte Auf, 1–123. Hannover: Max Jänecke.

- Mak, Geertje. 2012. Doubting Sex: Inscriptions, Bodies and Selves in Nineteenth-Century Hermaphrodite Case Histories. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Martin, Rudolf. 1914. Lehrbuch der Anthropologie in systematischer Darstellung mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der anthropologischen Methoden für Studierende Ärzte und Forschungsreisende. Jena: G. Fischer.

- Martin, Rudolf. 1928. Lehrbuch der Anthropologie in systematischer Darstellung, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der anthropologischen Methoden, für Studierende, Ärzte und Forschungsreisende, von Rudolf Martin. Zweite, vermehrte Auflage. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- M’Charek, Amade. 2013. “Beyond Fact or Fiction: On the Materiality of Race in Practice.” Cultural Anthropology 28 (3): 420–442. doi:10.1111/cuan.12012.

- Mol, Annemarie. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Morris-Reich, Amos. 2013. “Anthropology, Standardization and Measurement: Rudolf Martin and Anthropometric Photography.” The British Journal for the History of Science 46 (3): 487–516.

- Morris-Reich, Amos. 2016. Race and Photography: Racial Photography as Scientific Evidence, 1876–1980. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pels, Peter. 1999. A Politics of Presence: Contacts Between Missionaries and Waluguru in Late Colonial Tanganyika. Amsterdam: Harwood Adademic Publishers.

- Proctor, Robert. 1988. Racial Hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Römer, L. S. A. M. von. 1909. Voet- en handafdrukken verzameld tijdens de Nieuw-Guinea-expeditie, 1909. S.l.: s.n.

- Roque, Ricardo. 2010. Headhunting Colonialism: Anthropology and the Circulation of Human Skulls in the Portuguese Empire, 1870–1930. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sande, G. A. J. van der. 1903. “Verslag over Anthropologische En Etnografische Werkzaamheden.” Bulletin Maatschappij Ter Bevordering van Het Natuurkundig Onderzoek Der Nederlandsche Koloniën (45).

- Sande, G. A. J. van der. 1907. Nova Guinea. Uitkomsten der Nederlansche Nieuw-Guinea-Expeditie in…= Nova Guinea: résultats des expéditions scientifiques a la Nouvelle Guinéeen… Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Schaffer, Simon. 1992. “Self Evidence.” Critical Inquiry 18 (2): 327–362. doi:10.1086/448635.

- Schüttpelz, Erhard. 2005. “‘Sie Zu Messen, War Leider Trotz Aller Mühe, Die Ich Mir Gab, Und Trotz Aller Geschenke Unmöglich.’ Die Anthropometrische Interpellation.” In Antthropometrie, edited by Gert Theile, 139–154. München: Fink Verlag.

- Sibeud, Emmanuelle. 2012. “A Useless Colonial Science?: Practicing Anthropology in the French Colonial Empire, circa 1880–1960.” Current Anthropology 53 (5): S83–S94. doi:10.1086/662682.

- Sysling, F. H. 2013. “ The Archipelago of Difference: Physical Anthropology in the Netherlands East Indies, Ca. 1890–1960.” Thesis, Amsterdam University, Amsterdam.

- Treub. 1903. “Korte Samenvatting van de Toestpraak Etc.” Bulletin. Maatschappij Ter Bevordering van Het Natuurkundig Onderzoek Der Nederlandsche Koloniën 41: 30–31.

- Virchow, Rudolf. 1875. “Anthropologie Und Prähistorische Forschungen.” In Anleitung Zu Wissenschaftlichen Beobachtungen Auf Reisen: Mit Besonderer Rücksicht Auf Die Bedürfnisse Der Kaiserlichen Marine, edited by Georg Balthasar von Neumayer, 571–590. Berlin: Oppenheimer.

- Wichmann, Arthur. 1917. Bericht Über eine im Jahre 1903 ausgeführte Reise nach Neu-Guinea. Leiden: E.J. Brill.