ABSTRACT

The historical narrative of Habsburg grandeur has played a decisive role in branding the Austrian capital of Vienna. While scholars have situated place-marketing strategies within de-historicized frameworks of the neoliberal city, the nostalgic framing of imperial spatial assemblages should be critically interpreted from a historical vantage point. In tourist spaces such as the Kaiserforum, urbanists, museum curators, right-wing groups, and real-estate investors employ the discourse of Habsburg patrimony to leverage past spatial inequalities for contemporary purposes. Such nostalgic narratives obfuscate the historical material conditions of their making. I argue that this very obfuscation constitutes a continuing legacy of empire. I call this process ‘whitewashed empire,’ the redeployment of imperial structures through the preservation, renovation and assemblage of material heritage. As a memorial assemblage of narrative selection and a political economic relation of exploitation, imperial nostalgia extends the work of Habsburg spatial production into the present.

Introduction

In the early morning hours of 29 November 2016, members of the Identitarian Movement of Austria (Identitäre Bewegung Österreich), a white-supremacist anti-migration group, staged a public action to commemorate the anniversary of Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa’s death. Under the cover of night, they shrouded Maria Theresa’s statue, located between the museums of Natural and Art History, with a burqa-like cloth to protest the so-called ‘Islamization’ of Austria. While the cloth was quickly removed by the police, the act brought international media coverage to the group.Footnote1

Bringing together the commemoration of empire, racial-cultural supremacy and claims to ‘European’ urban space, the clandestine action laid bare the ongoing work performed by Habsburg legacy in the centre of Vienna. Located in the middle of a tourist forum which connects the city’s museum quarter with its imperial court, the Identitarians’ politics were both spatial and historical. While nostalgia for the Dual Monarchy has received a substantial amount of attention in the past decade (Ballinger Citation2003; Wolff Citation2012; Kamusella Citation2011; Kozuchowski Citation2013; Arens Citation2014; Schlipphacke Citation2014), scholars of the Habsburg mythos (Magris Citation1966) have shown comparatively less attention to the architectural and material heritage of empire. This is in sharp contrast to the historical significance of Habsburg urban space, which remained a significant part of imperial identity construction from the Eighteenth century onwards (Moravánszky Citation1998; Prokopovych Citation2009).

Today, the preservation, reconstruction and marketing of Austro-Hungarian urbanity plays an important role in a number of cities, as municipal administrations leverage imperial history on the global tourist market. In Vienna, local authorities have employed the Habsburg past as a resource in place marketing strategies since at least the 1980s (Kelley Citation2009; Popescu and Corboș Citation2011). For scholars of critical urban studies, place marketing is a form of ‘urban entrepreneurialism’ which expands the terrain of accumulation by curtailing public services at the expense of growth-oriented policies (Harvey Citation1989; Boyer Citation1992). What such analyses side-line is the important relationship between the material history of inequality and contemporary production of historicized urban space. As the shrouding of Maria Theresa’s statue indicates, the nostalgic backdrop of imperial structures informs contemporary urban politics beyond seemingly neutral strategies of place marketing.

This essay discusses the material history and contemporary reverberations of Habsburg space through my concept of ‘whitewashed empire,’ a term informed by the work of race and postcolonial studies scholars (Bloom Citation1993, 93–94; Gabriel Citation2002, 4). Their use of whitewashing is metaphorical, describing social forces of obfuscation, bleaching, beautification, inclusion and exclusion. My purpose is to bring such metaphors in conversation with theories of architecture and the material transformation of space. White walls can indeed take part in dispossession, a point emphasized by a number of scholars (McClung Citation2000, 110; Deverell Citation2005, 250–51; Rotbard Citation2014). The preference for clean, unornamented facades, a defining feature of architectural modernism, likewise originates in the context of colonialism and unequal translation (Vogt Citation2000).

Keeping in mind that the concept of whitewashing has mostly been employed in studies dealing with race and colonialism, what kind of conceptual and political work can ‘whitewashing’ do in Central Europe? First, it questions the supposed absence of colonial logics and their historical conditions from the cultural space of Habsburg Mitteleuropa (Sauer Citation2002; Feichtinger Citation2003; Ruthner and Scheer Citation2018). Second, it critically engages the material practice of renovating and maintaining architectural assemblages, through their symbolic and political economies. Whitewashed empire approaches imperial historicity at the intersection of its discursive and material construction.

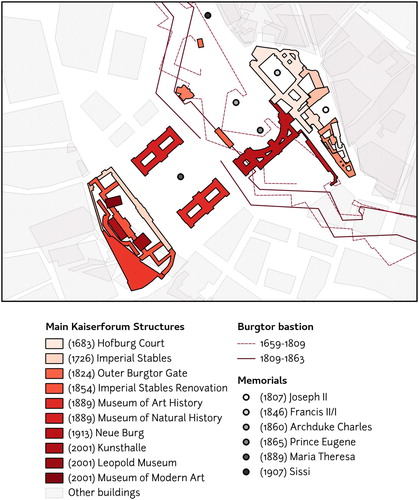

My site of inquiry is Vienna’s Kaiserforum, a monumental square consisting of the Neue Burg, Heldenplatz, Maria-Theresienplatz, the museums of Art History and Natural History, and the Museumsquartier. While other tourist sites within Vienna share a similar Habsburg-nostalgic character, the Kaiserforum is significant precisely because it merges a multiplicity of meanings. It is a quintessentially imperial space that binds together aristocratic and bourgeois cultural artefacts, the production of colonial knowledge, narratives of military might, and modern architecture. By tracing the imperial genealogy of the Kaiserforum, my purpose is to see the city as an archive of unequal development (Harvey Citation1985, Citation2006), upsetting any common-sense reading of urban space as a cultural or political artefact. While such historically-bound readings might differ from narratives immediately accessible to observers of architectural heritage, they also offer disciplined counter-narratives that trouble the relationship between past and present (Walton Citation2016).

In their contemporary configuration, nostalgic narratives of the Habsburg past frame Vienna’s imperial centre as a backdrop to the museum industry, Islamophobic groups, and real-estate investment. Viewed through the lens of ‘whitewashed empire,’ this restoration of imperial heritage leverages historical inequalities while simultaneously obfuscating the terms of their existence. The consequence of this process is a zombie-like imperial formation (Stoler Citation2008) that redeploys past violence even when its underlying structures have seemingly disappeared.

The historical development of Vienna’s Kaiserforum

From its baroque beginnings to its modern institutionalization, the Kaiserforum developed as a quintessentially imperial public space. Arguably, it was inaugurated by the definitive architect of Habsburg baroque, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, whose 1713 project for the new imperial stables envisioned ample space for spectators. Completed by his son in 1725, the stables were designed as a semi-circular structure whose frontal facade faced the castle gate (Burgtor) and the imperial court (). Likely part of a larger, monumental vision (Lorenz Citation2001), the building broke the separation between intramural and suburban Vienna by facing the military training fields (Glacis) outside the city walls.

Figure 1. Historical Evolution of the Kaiserforum (1720–2001). Darker buildings are newer.

Source: QGIS georeferenced historical maps by author. Basemap OSM data by OpenStreetMap.org.

Even though Fischer von Erlach’s project was never fully completed, the monumentality of the stables is clearly visible in period maps.Footnote2 Informed by classical and Islamic architecture, Erlach employed performance, staging and theatricality to portray Habsburg might in elaborate white facades (Caravias Citation2008; Dotson Citation2012). As one of progenitors of architectural Orientalism (Aurenhammer and von Erlach Citation1973), his global outlook was contemporaneous with Habsburg overseas designs in Southeast Africa and India, as well as construction projects in newly-acquired Serbia (Popović Citation1983; Ingrao Citation2000, 214). Contemporaneous with his homage to Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, the Karlskirche, J.B. Fischer von Erlach’s Imperial stables were modelled after monumental sites of classical history (Gottfried Citation2001), demonstrating Habsburg claims on imperial power.

Although monumental plans that traversed the city walls emerged in the Eighteenth century,Footnote3 an unencumbered line of sight between the stables and the court was only established in the Nineteenth.Footnote4 With the reconstruction of the Burgtor bastion, radial paths channelled vistas of the Glacis towards the stables.Footnote5 Between 1850 and 1854, a neobaroque reconstruction of the stables revived Fischer von Erlach’s original design, evoking Eighteenth century Habsburg grandeur.Footnote6 During the same period, baroque monumentality came to be coupled with curated narratives of imperial history and cultural supremacy.

In the Nineteenth century, the Habsburg past came to be personified through several memorial spaces in prominent positions around the imperial court. This was a quintessentially modern form of whitewashing, in which the material heritage of Fischer von Erlach’s stables was brought in conversation with monumental historicist narratives. The objects built included a monument to Joseph II (1807), the reconstructed outer Burgtor gate (1824), the Francis II/I memorial gate (1846) and two equestrian monuments to Archduke Charles (1860) and Prince Eugene of Savoy (1865). Finally, the Maria Theresa monument (1888) completed the memorial assemblage () centred around the axis between the stables and the court established earlier by Fischer von Erlach’s designs.

Figure 2. Wilhelm Burger. Monument to Archduke Charles (1874). View towards the Burgtor with the Imperial Stables in the back right. Imperial Museums and the Maria Theresa monument are still under construction.

Source: OeNB, BA WB 49C(D).

The two monuments to Archduke Charles and Prince Eugene temporally framed Habsburg history by evoking victories against Napoleon and the Ottomans. Both were designed by Anton Dominik Fernkorn, a neo-baroque sculptor inspired by the historicist paintings of Johann Peter Krafft. Unveiled on the 202nd anniversary of his birthday, Prince Eugene‘s monument featured the dates and locations of his military successes against the Ottomans. The pedestal of the Archduke Charles monument included a calendar with twenty-four significant dates, its inscriptions penned by imperial historian Theodor von Karajan (Riesenfellner Citation1998, 82). Putting Nineteenth-century Archduke Charles and Seventeenth-century Prince Eugene in spatial and thematic dialogue with one another, Fernkorn and Karajan curated an imperial historical assemblage.

The Kaiserforum materialized the narrative of imperial reach, showcasing the known world alongside the Habsburg past. Contemporary with plans for the Ringstraße, two museums of natural and art history were envisioned to complement the historical memorials. The chosen design by Gottfried Semper and Carl Hasenauer conceptualized the entire area spanning the Ringstraße as a single forum with two massive court buildings framing the equestrian statues.Footnote7 The Semper/Hasenaur design completed Fischer von Erlach’s whitewashed vision by bringing together historical narrative, architectural grandeur, and institutions of cultural supremacy.

One of the highlights of Semper’s plan had been the museum buildings, meant to house the court collections of art and natural history. Their major part consisted of 133,000 objects collected by an Austrian expedition to Brazil (Schmutzer and Feest Citation2013, 267). In addition to objects and live animals, the expedition brought two captured Aimoré people to Vienna, who lived and worked in the outer Burgtor gardens (Schmutzer and Feest Citation2013, 270–71). Many other objects exhibited in the museum complex were colonial in origin. Among the holdings were items collected by the SMS Novara, an Austrian Imperial Navy vessel which attempted to establish colonial outposts on the Nicobar island of Nancowery during its 1857–9 circumnavigation of the globe (Hermann Mückler Citation2012, 54–56, 214; Sauer Citation2012, 14). Other ethnographic and ornithological collections came from Bari and Shilluk lands in South Sudan, collected by Habsburg missionaries (Cisternino Citation2004, 9–19; Willink Citation2011, 322). Contemporaneously, the city hosted stagings of the empire’s Balkan colony, Bosnia and Herzegovina, representing the Habsburgs’ ‘civilizing mission’ (Reynolds-Cordileone Citation2015). While the ability to display distant items and people presented the Habsburgs as cooperative members of the European imperial family (Sauer Citation2012), for many Viennese, it also meant participation in a metropolitan culture of ‘exotic’ consumption.

The Kaiserforum was Vienna’s only ‘metropolitan image,’ argued the architect Otto Wagner, a site where aristocratic historicism and bourgeois social forces could be negotiated (Schorske Citation1980, 103). Such ‘imperial modernism’ (Crinson Citation2016) infused the exploitation of industry, agriculture and colony with new aesthetic ideas, exemplified by early Twentieth century designs for the forum by Wagner and his contemporary, Camillo Sitte. Presaging Twenty-first century discourses, fin-de-siècle Vienna became a ‘world city’ (Weltstadt) precisely at the Kaiserforum, where imperial history and cultural supremacy could be brought in conversation with one another. Wagner and Sitte’s forum materialized whitewashed empire, articulating a modern aesthetic which bound aristocratic historicism to bourgeois futurity.

Although the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire opened up the possibility of radically re-imagining imperial spaces, historicist linkages reasserted themselves in the interwar period. In 1934, the outer Burgtor was proclaimed as a memorial for fallen soldiers and renamed the Heroes’ Gate (Heldentor). Plans for its redesign included two buildings commemorating the 1683 siege of Vienna and the end of the First World War in 1918.Footnote8 In 1938, Adolf Hitler proclaimed the incorporation of Austria into the Third Reich from the terrace of the Neue Burg; subsequently, a bust of the Führer meant to commemorate the event was designed in 1940, adding him to the pantheon of now-national imperial heroes of the Heldenplatz.Footnote9 Simultaneously, images and plans of the Kaiserforum’s architectural development were exhibited in the Neue Burg together with overseas collections.Footnote10 The equestrian statues of Prince Eugene and Archduke Charles were bricked up for protection from Allied air raids. The continued production of imperial meaning in the Kaiserforum by the Austrofascist and National Socialist regimes emphasized historical continuity between Habsburg and Austrian/German pasts.

My purpose in tracing this history is not to argue that the physical space of the Kaiserforum is necessarily bound to the Habsburg past. As Brantner and Rodriguez-Amat (Citation2016) have recently shown, shared experiences of Viennese anti-fascist protesters at the Kaiserforum can represent new assemblages outside the logic of historicized space. Rather, I argue that the imperial history of spatial production permeates the present in uneven ways, informing existing structures of violence. As a site of place marketing today, the Kaiserforum cultivates imperial narratives that were integral to past structures of exploitation. Because such inherited structures continue to be leveraged in the global market, the logic of empire continues to permeate contemporary spatial relations. This continuity is the work of whitewashed empire, a process of binding Habsburg material heritage to a specific historical narrative and its contemporary material expression.

Contemporary reverberations of imperial space

The 1998–2001 renovation of the imperial stables and the creation of the Museumsquartier produced narratives that linked modern, ‘European’ culture and the imperial past. Their progressive logic often ignored uncomfortable histories of the space, including its National Socialist past. Initial projects to reconstruct the stables into an art and culture forum developed in the 1980s, with various activist groups involved in public debates over its future use (Ehalt Citation1986). After plans to build a shopping centre and hotel became public, cultural activists lobbied to add the stables to the existing federal museum structure (Bogner Citation2001, 37). Ultimately, the planning resulted in a 1985 government draft which relied on place marketing discourse. The project was a chance to increase ‘the attractiveness of Vienna as a museum city,’ create a missing space for large international exhibitions, and form an ‘attractive, lively center for domestic and foreign visitors’ linked to other urban features (Ehalt Citation1986, 71).

While the draft plan floundered, many of its goals were resurrected four years later, after a second reconstruction competition was won by the Ortner & Ortner architectural bureau. Their original design was iconoclastic, focusing on contemporary culture and media (Bogner Citation2001, 38). At the same time, the stables were occupied by autonomous art groups. Ultimately, however, public pressure shifted the architectural intervention towards more conventional linkages with the Habsburg past. As an 18 January 2001 article in Die Zeit noted, the fundamental question of the reconstruction came to be: ‘can tradition and modernity, the imperial and the contemporary Vienna be united at all?’ By the late 1990s, the renovation of the imperial stables became a vessel for this historical narrative, where the Habsburg past informed an imagined collective present.

How did this shift take place? In their initial designs, the Ortner & Ortner bureau countered the spatial logic of Habsburg baroque by including a 67 m library tower that dwarfed the original facade (New York Times, 12 Sep 1993). Yet, defining the (post)imperial space of the Museumsquartier quickly became subject to strategic contestations (De Frantz Citation2005; Abfalter and Piber Citation2016). A public outcry spearheaded by the right-leaning newspaper Kronen Zeitung, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), and the Greens resulted in substantial changes which maintained the primacy of the neobaroque structure. While cancelling the library tower remained a ‘thorn in the flesh,’ the architect Laurid Ortner ultimately described the compromise as an innovative solution to the inner city challenges of ‘all European metropolises’ in an interview with Der Standard (17 Jun 2011). As journalist Ulrike Knöfel sarcastically noted in Der Spiegel on 25 June 2001,

a nostalgic Viennese should not worry that the quarter’s architecture will outdo the neighbouring imperial-period forum. Because such a heresy is unthinkable, the new buildings are placed deep –several stories in the ground – instead of standing out in the cityscape … Whoever stands in front of the decorative front, will notice little of the present and absolutely nothing of the future.

The institutions selected for the Museumsquartier were curated to show a historical affinity between contemporary and imperial bourgeois modernism. The quarter continues to house a collection of late imperial modernist painting (the Leopold Museum), the Museum of Modern Art (MUMOK), a contemporary exhibition space (Kunsthalle Wien), and the national architecture museum (AzW). Alternative visions, some already established in the area prior to its renovation, were either sequestered or deemed incompatible. Public Netbase t0, an open access internet provider and digital activist platform, was excluded from the plans and forced to leave the quarter (Netbase). Others, such as the Quarter21 platform for independent art, were created as support structures ‘where art and business intersect.’ As part of its activities, Q21 curates micro-museums in the passageways of the baroque structure, as ‘alternative exhibition platforms that complement and expand’ the existing museums of imperial modernism. ‘Alternative’ art in the form of comics or sound installations is placed within the material confines of place marketing discourse. Inhabiting the Museumsquartier required compatibility with imperial roots.

Maintaining the integrity of the Kaiserforum has involved various forms of urban management: refusal to build, protection of structures, reconstruction and literal whitewashing through facade protection. Recent proposals for the Heldenplatz and Maria-Theresien-Platz, for example, maintain the visual layout of the square by placing new functions underground (Meinbezirk.at). Throughout these reconstructions, the Kaiserforum’s structures remain in conversation with one another, amplifying each other in ways that obscure past disturbances and the passage of time. This work maintains imperial vistas envisioned by the original designers, whitewashing the textured surface of the Kaiserforum’s historicity. The deep grooves of human time which has chiselled away at empire appear bright from the perspective of the casual visitor. By illuminating the genealogy of material heritage, one of my aims has been to restore the ‘textured historicity’ of imperial space, in line with the perspective forwarded by Walton in the introduction to this volume. Shaped by contemporary capitalist relations and European cultural politics, whitewashed empire subsumes the textured character of lived space. It flattens surfaces, like whitewash mixtures on a façade.

In contemporary images produced for tourist consumers, the viewer’s gaze is drawn to particular points–the equestrian statues, Maria Theresa, the central axis of the square. In its front-page scroller, the Museumsquartier website follows the imagined perspective of Fischer von Erlach’s baroque vision (). Technical differences notwithstanding, the views both accentuate the dramatic central projection and its spatial monumentality. Habsburg material heritage infuses the socio-spatial imaginary with a circumscribed visual language, articulating a continuing legacy of empire.

Figure 3. MuseumsQuartier website scroller (2001) [top, © MuseumsQuartier Wien, photo: Peter Korrak] and Fischer von Erlach’s design for the Imperial Stables (1721) [bottom, OeNB, BA Z85025400]. Collage by author.

![Figure 3. MuseumsQuartier website scroller (2001) [top, © MuseumsQuartier Wien, photo: Peter Korrak] and Fischer von Erlach’s design for the Imperial Stables (1721) [bottom, OeNB, BA Z85025400]. Collage by author.](/cms/asset/e0deaef4-63d7-432c-b208-fc44c5f4da26/ghan_a_1617709_f0003_oc.jpg)

For visitors, the whitewashing of discursive and physical representations of the Habsburg past offers similarly framed vistas. Bisecting the Ringstraße, the central pedestrian axis of the Kaiserforum links cultural production to imperial history. During one of my visits in the fall of 2016, even the side exits of the Museumsquartier reminded passers-by that ‘Vienna has culture.’ Part of a municipal development strategy (wien.at Citation2015), the slogan’s intended message was based on inclusivity, diversity and activism. Yet, a more immediate association to ‘culture’ is produced by the surrounding Habsburg spatial assemblages. Many of my fellow visitors took photographs in front of imperial structures, bridging their immediate perspective with the framework of place marketing. Markedly, the advertisement of Vienna’s cultural bounty was missing from the central entrance. There, the curated arrangement of monuments, buildings and advertisements for historical exhibits ‘speaks for itself,’ a cultural space framed for visitors’ consumption.

Narrative links between the ‘culture’ of imperial space and present-day violence have been drawn explicitly by right-wing and white-supremacist groups, namely the Austrian fraternities (Burschenschaften), the Vienna branch of FPÖ and the Identitarian movement. These groups have employed central structures of the Kaiserforum for various events, protests and functions. Organized annually by the Austrian fraternities, the Academics’ Ball (Akademikerball) in the Hofburg is described as a night of ‘splendour, glamour and tradition’ on its official website (Wiener Akademikerball). It involves a heteronormative performance of quasi-historicized ballroom dancing, where one ‘cannot miss the music of the Strauß family, von Lanner, Lehár, Ziehrer und Kálmán.’ As philosopher Isolde Charim has noted (Citation2017), the ball represents ‘the right performing an old piece in old costumes,’ a politicized reference to aristocratic historicism. For right-wing activists, the claim to the Hofburg is primarily symbolic, linking Habsburg splendour, Hitler’s proclamation of the Anschluss, and present-day racist politics. Although the event has faced strong public protest since 2008, the ball has continued unabashed due to the FPÖ’s status as a parliamentary party. The state officials’ tacit acceptance of the ball strengthens the links between the imperial past and contemporary racist discourse.

The Identitarian Movement Austria, a white-supremacist anti-migration group, has also made such connections. In the past two years, the group organized four major events which refer to the Kaiserforum’s imperial heritage. These included a banner drop on the nearby Burgtheater, the covering of Maria Theresa’s statue that I described at the outset of the essay, a protest against the renaming of Heldenplatz, and an anti-Turkish banner drop featuring a silhouette of Prince Eugene’s equestrian statue. In a Facebook post justifying their action on Maria-Theresien-Platz, the group stated that ‘the empress’ legacy is being trampled by politics today.’Footnote11 Relying on Habsburg-nostalgic assemblages of the Kaiserforum, the Identitarians have sought to popularize dog-whistle terms such as ‘guiding culture’ (Leitkultur) and ‘European values.’

Europeanness and Habsburg culture are brought together in their bourgeois cultural form in the Museumsquartier, where the Leopold Museum hosts a world-renowned exhibit of Secession-era art. Entitled ‘Vienna 1900,’ the exhibit frames the imperial capital as a modernist project of civilizational and cultural development. Raised slightly above the exhibited art and Wiener Werkstätte objects is a panoramic window, allowing visitors to ‘put Vienna’s Ringstrasse in an overall context’ by viewing the Kaiserforum.Footnote12 Opposite, a set of Habsburg-era maps show Vienna’s progressive development during the Nineteenth century. The purpose of this part of the exhibit is to ‘document the groundbreaking achievements of Vienna’s architects,’ bringing architecture into conversation with the fin-de-siècle paintings of Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt. Although the exhibit stresses the ‘lasting influence’ of the Viennese Secession, it’s temporal scope in fact ends with the Habsburg Empire in 1918.

The secondary focus of ‘Vienna 1900’ is multiculturalism, in which the Habsburg modernist tradition is framed as a precursor to an inclusive European present. Near the end of the exhibit, a room entitled ‘Schiele as a European’ frames the painter as an early ideologue of European integration. The display notes that Schiele’s multiculturalism had come from guarding Russian prisoners of war, who represented ‘more interesting countries, more thinking people,’ even in their poverty. The Gustav Klimt exhibit expands upon such fascination with the foreign by including assorted colonial objects in the painter’s workspace. While the influences of Japanese and Chinese art on Klimt’s are represented, the contemporaneous Austro-Hungarian colonial presence in China is absent from the narrative. According to the exhibit, the foreign Other was a distant inspiration for Viennese modernism, which ended in 1918 with the deaths of Klimt, Schiele and the multicultural Habsburg empire.

The colonial heritage of Habsburg and European modernism is clearest in ‘Foreign Gods: Fascination Africa and Oceania,’ a special exhibit of non-European items collected by the museum founder, Rudolf Leopold. ‘Foreign Gods’ begins by declaring that non-Europeans had ‘no word for art,’ and ends with Paul Klee’s statement that ‘there are primitive beginnings in art, such as one usually finds in ethnographic collections or at home in one’s nursery.’ While the origin of some objects exhibited in ‘Foreign Gods’ is unclear, at least fifty-one came from the descendants of Erwin Raisp Edler von Calliga, the first officer of the Austro-Hungarian cruiser Zenta (Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon [Citation1983] Citation2017). The ship is best known for its bombardment of the Dàgū forts during the Boxer War, resulting in Austria-Hungary’s only Chinese colony in Tianjin (Sondhaus Citation1994, 123–69). Like the imperial museums of the 1880s, ‘Foreign Gods’ curates worldly knowledge by displaying the bounty of Habsburg colonial efforts. While the exhibit presents critical voices, such as the work of French-Algerian installation artist Kader Attia, it does so in a physically and thematically sequestered space. On the exhibition website, the curators describe Attia’s work as elucidating ‘the cultural relationship between previously colonized ethnicities and former colonial powers.’ (FREMDE GÖTTER). Such framing structures the narrative of the Museum in which primordial essences are drawn out by cultivated Habsburg modernists, leveraging imperial history to construct European cultural assemblages.

Cultural tourism and Habsburg nostalgia have been part of Vienna’s place-marketing strategies since at least the 1980s. They have been very effective expanding the tourist industry’s share of the city’s economic output, which grew from ten to fifteen percent between 2002 and 2013 (WienTourismus Citation2014, 11). In 2016, the city received over 15 million overnight stays, 81% of which were from abroad (WienTourismus Citation2017). That year’s marketing efforts capitalized on the centenary of Franz Joseph’s death with the motto ‘Imperial and Co(ntemporary),’ showcasing the city’s as a historic and modern place to live. In the words of the city’s ‘business to business’ tourist service website: ‘Vienna proves that the old imperial and modern contemporary are not mutually exclusive.’ (Vienna 2016). Through place marketing efforts, Viennese officials have sought to frame Habsburg heritage as a precursor to modern urbanity.

The real-estate market has likewise looked to empire for the purposes of profit, renovating historical buildings surrounding the Kaiserforum for wealthy consumers in search of cultured living. The Am Kaiserforum loft conversion project at Nibelungengasse 15, for example, capitalizes on the aristocratic history of its building. With fifteen luxury units reaching prices over four million euros, the Am Kaiserforum building advertises ‘representative housing of the aristocracy renovated and revived in the tradition of Viennese salons.’ (Raiffeisen Immobilien). On its website, a scan of the Semper/Hasenauer plan for the Kaiserforum features the Nibelungengasse building circled in red. A few hundred metres away, the Goethegasse Citation1 penthouse offers the would-be purchasers of its multi-million euro apartments a living experience that its website describes as ‘shoulder to shoulder with Gustav Klimt,’ including a 360° view of Vienna ‘and its world-famous artistic and cultural treasures.’ Through Habsburg nostalgia, investors can capitalize on municipal place marketing efforts by leveraging Vienna’s imperial culture on the real-estate market.

Habsburg-nostalgic construction projects depend on another material heritage of empire: the unequal cost of labour between Austria and former Habsburg territories in the Balkans. According to official statistics, 189,000 migrants from former Yugoslavia live in Vienna (Statistik Austria Citation2017) although unofficial estimates are as high as half a million (MSNÖ Citation2014). In 2012, some 37% of registered construction workers were foreigners, most coming from Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo (Ille Citation2012). In the past two decades, Austrian firms have come to dominate the Balkan construction industry, replacing local firms as chief purchasers of labour power. The ‘Am Kaiserforum’ renovation itself was managed by PORR, an employer of seasonal labour from the region. The presence of Balkan and East European builders on Habsburg-nostalgic projects in Vienna represents the lasting imperial legacy of material and political inequality.

The invisibility of migrant labour in the making of Viennese urban space was addressed in a 2015 exhibit by the Viennese-Macedonian artist Milan Mijalkovic. His series ‘Workers’ features a seemingly-automatic balloon dispenser powered by human breath and a monument-like human statue entitled ‘Worker with Sledgehammer’ (). The latter figure references the ubiquitous Viennese historical monuments, positioning a sledgehammer-wielding worker in orange attire on a pedestal made out of a dusty trashcan. While the Viennese construction industry depends on structural inequalities inherited from the imperial period, Habsburg-nostalgic place-marketing decisively obscures such tensions. Physically and discursively, it depends on whitewashing to obscure history’s uneven texture in the present.

Historicity and the material heritage of empire

During my visits to Vienna in 2016 and 2017, smartphones played an important role in visitors’ experiences of the Kaiserforum (). Inserting the self into imperial vistas and the propagation of such images on social networks played a significant factor in people’s consumption of this monumental space. Coupled with a lack of textual information, such forms of spatial consumption dissociate the spectator from imperial structures of violence embedded in the buildings themselves. In the early Twentieth century, the assassin of the Habsburg Archduke Francis Ferdinand, Gavrilo Princip, had prophesized that the shadows of the oppressed would wander the Viennese court.Footnote13 Yet, in its contemporary configuration the Kaiserforum distances its observers from the empire’s ghosts.

Figure 5. Imperial vistas, material heritage, and tourist photography. Heldenplatz [left] and Maria-Theresien-Platz [right], November 2016/March 2017. Photographs by author.

![Figure 5. Imperial vistas, material heritage, and tourist photography. Heldenplatz [left] and Maria-Theresien-Platz [right], November 2016/March 2017. Photographs by author.](/cms/asset/5f53d37e-146b-4177-af05-fde4c133005d/ghan_a_1617709_f0005_oc.jpg)

My point here is not to criticize the visually-focused consumption of imperial space, but rather to argue that in spaces of heightened historicity, individual agency can be subsumed by the thick interplay between historical and contemporary material processes. Subsumption does not mean subjection, and alternative spatial narratives remain accessible even within this circumscribed historical materiality (Brantner and Rodriguez-Amat Citation2016). Yet, the contemporary (re)production of imperial vistas, its interface with global trends of place marketing, and propagation onto the realm of the self(ie) allow material heritage to function as a structure of power. Borrowing loosely from Anthony Alofsin’s linguistic taxonomy (Citation2006, 13–14), my purpose has been to elucidate a spatial ‘language of empire’ by bringing past and present together in an inflected conversation. When Vienna’s buildings speak, they carry the hybrid messages of their time, sieved through present-day forms of inequality.

In the previous two sections, I have sought to juxtapose the history of imperial space to its contemporary articulations. I see spaces such as the Kaiserforum as sites of heightened historicity, in which various imperial pasts and present inequalities relate to and structure one another. They serve as anchor points for present-day imaginings of modernity, history, Europeanness, and culture. They also rely on the complex interplay between material and discursive processes, in which historicity is a feature of architectural and spatial assemblages. In such spaces, whitewashed empire produces coherent narratives out of a multiplicity of (post)imperial meanings.

I have referred to the interplay of these varied processes as ‘whitewashed empire,’ the redeployment of imperial structures through the preservation, renovation and assemblage of material heritage. This is not merely a nationalist phenomenon which retrofits the Habsburg Empire as a form of proto-Austrianness. Like Habsburg-era identity construction, whitewashed empire relies on broader discourses of European supremacy. When alt-right groups lay claim to imperial heritage, they do so precisely because of Europe’s construction as an assemblage of various imperial projects. Such historicist claims necessarily interface with existing historical-spatial assemblages and the work of architectural preservation. Restoring monumental buildings and museums in the name of cultural heritage reproduces the aristocratic-bourgeois synergy embedded in late-Habsburg space-making. These processes are deeply integrated into global flows of capital, as place marketing efforts situate Vienna on the world’s real-estate and tourist markets. For urban managers, imperial historicity represents one answer to the post-industrial conundrum, a way to extract profit from the legacy of material inequality whose original structural framework has long disappeared. European supremacy, the restoration of aristocratic-bourgeois world-views, and the extraction of profit from spatial heritage are three facets of whitewashing that obscure the gritty textures of empire. Bound by imperial nostalgia, they are the narrative framework and material base of empire’s contemporary legacies.

Acknowledgments

I owe my gratitude to Annika Kirbis for introducing me to the Kaiserforum project and the Ajnhajtclub exhibit, Piro Rexhepi for his insights on Austro-Hungarian colonialism, Giulia Carabelli for her advice on material heritage and the production of space, Jeremy F. Walton for his insightful literature suggestions, Léonie Newhouse, Shahd Wari, and Somayeh Chitchian for their advice on South Sudan, GIS visualization, and critical urban studies, Milan Mijalkovic for kindly volunteering his images, Adriana Qubaia, Gruia Bădescu, and Srđan Atanasovski for their feedback on the paper’s early drafts, and Franziska J. Wallner for introducing me to the Museumsquartier through Viennese eyes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Miloš Jovanović http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8528-1013

Notes

1. The Identitarians’ leader, Martin Sellner, was interviewed by large media groups such as BBC and CNN News in December 2016.

2. Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (OeStA) Kriegsarchiv (KA) G I h 772 and OeStA KA G I h 777.

3. Plan von Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt 1724, Albertina Wien, Architektursammlung, AZ6038.

4. Ibid.

5. OeStA HHStA A-V-11/1461.

6. OeStA Haus- und Hof- Staatsarchiv (HHStA) Planarchiv der Burghauptmannschaft Wien (PAB) A-II-15/4418.

7. OeStA HHStA PAB O-13/5015, PAB D-4/1266, PAB D-4/1271.

8. OeStA HHStA PAB O-75/5057/69.

9. OeStA HHStA PAB A-I-5/6083.

10. Sonderausstellungen des Kunsthistorischem Museums in der Neuen Burg. (Wien: Verlag des Vereines der Museumsfreunde, 1940).

12. This and following quotations from museum texts are based on fieldnotes that I recorded on 24 November 2016.

13. The full quote (‘Our shadows will walk in Vienna/roaming through the palace/frightening the gentry’) has been attributed by Yugoslav historian Vladimir Dedijer (Citation1966, 14) to one of Princip’s poems, written during his imprisonment in Terezin.

References

- Abfalter, Dagmar, and Martin Piber. 2016. “Strategizing Cultural Clusters: Long-Range Socio-Political Plans or Emergent Strategy Development?” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 46 (4): 177–186. doi:10.1080/10632921.2016.1211051.

- Alofsin, Anthony. 2006. When Buildings Speak: Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and Its Aftermath, 1867–1933. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

- Arens, Katherine. 2014. Belle Necropolis: Ghosts of Imperial Vienna. New York: Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers.

- Aurenhammer, Hans, and Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach. 1973. J. B. Fischer von Erlach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ballinger, Pamela. 2003. “Imperial Nostalgia: Mythologizing Habsburg Trieste.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 8 (1): 84–101. doi:10.1080/1354571022000036263.

- Bloom, Lisa. 1993. Gender on Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press.

- Bogner, Dieter. 2001. “Zufallsergebnis oder geplante Vielfalt? Das Konzept des Museumsquartiers A Product of Chance or Planned Diversity? The Concept of the MuseumsQuartier.” In MuseumsQuartier Wien: die Architektur – The Architecture, edited by Matthias Boeckl, 33–40. Wien: Springer.

- Boyer, Christine. 1992. “Cities for Sale: Merchandising History at South Seaport Street.” In Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, edited by Michael Sorkin, 181–204. New York: Noonday Press.

- Brantner, Cornelia, and Joan Ramon Rodriguez-Amat. 2016. “Constructing Public Space New ‘Danger Zone’ in Europe: Representations of Place in Social Media–Supported Protests.” International Journal of Communication 10: 299–320.

- Caravias, Claudius. 2008. Die Moschee an Der Wien: 300 Jahre Islamischer Einfluss in Der Wiener Architektur. Eichgraben: Luna.

- Charim, Isolde. “Allein in Der Sperrzone – Wiener Zeitung Online.” Kommentare – Wiener Zeitung Online. Accessed March 17, 2017. http://www.wienerzeitung.at/meinungen/kommentare/798242_Allein-in-der-Sperrzone.html.

- Cisternino, Marius. 2004. Passion for Africa: Missionary and Imperial Papers on the Evangelisation of Uganda and Sudan, 1848–1923. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

- Crinson, Mark. 2016. “Imperial Modernism.” In Architecture and Urbanism in the British Empire, edited by G. A. Bremner. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198713326.003.0007.

- De Frantz, Monika. 2005. “From Cultural Regeneration to Discursive Governance: Constructing the Flagship of the Museumsquartier Vienna as a Plural Symbol of Change.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29 (1): 50–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00569.x

- Dedijer, Vladimir. 1966. Sarajevo 1914. Beograd: Prosveta.

- Deverell, William. 2005. Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of Its Mexican Past. Reprint edition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dotson, Esther Gordon. 2012. J.B. Fischer Von Erlach: Architecture as Theater in the Baroque Era. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung, 1986. “Konzept Für Eine Neustrukturierung Der Bundesmuseen (Museumskonzept),” in Kaiserforum, Museumsinsel, Kulturpalast: Ein Neues Museum Als Jahrhundertchance? Kulturjahrbuch 5, edited by Hubert C. Ehalt, 69–76. Wien: Verlag für Gesellschaftskritik.

- Feichtinger, Johannes, et al. 2003. Habsburg postcolonial. Machtstrukturen und kollektives Gedächtnis. Innsbruck: Studien Verlag.

- ‘FREMDE GÖTTER’. Accessed March 30, 2017. http://www.leopoldmuseum.org/de/ausstellungen/77/fremde-goetter.

- Gabriel, John. 2002. Whitewash: Racialized Politics and the Media. New York: Routledge.

- Goethegasse 1. “Die Penthouses – Goethegasse 1 – Inspiring Space.” Accessed April 6, 2017. http://goethegasse1.at/penthouse.php?lang=en.

- Gottfried, Margaret. 2001. Das Wiener Kaiserforum: Utopien zwischen Hofburg und MuseumsQuartier: imperiale Träume und republikanische Wirklichkeiten von der Antike bis heute. Wien: Böhlau.

- Harvey, David. 1985. The Urbanization of Capital: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization. 1st ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Harvey, David. 1989. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 71 (1): 3–17. doi:10.2307/490503 doi: 10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Harvey, David. 2006. Paris, Capital of Modernity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hermann Mückler. 2012. Österreicher in Der Südsee: Forscher, Reisende, Auswanderer. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- IBÖ (Identitäre Bewegung Österreich). “Erdogan – Hol Deine Türken Ham!” n.d. Accessed April 6, 2017. https://iboesterreich.at/2017/03/22/erdogan-hol-deine-tuerken-ham-identitaere-aktion-bei-der-tuerkischen-botschaft/.

- Ille, Karl. 2012. Kommunikation und Sicherheit auf der mehrsprachigen Baustelle. Wien: Institut für Romanistik der Universität Wien. http://medienservicestelle.at/migration_bewegt/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/IBIB_AK_Baustellenprojekt_Studie.pdf.

- Ingrao, Charles W. 2000. The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kamusella, Tomasz. 2011. “Central European Castles in the Air? A Reflection on the Malleable Concepts of Central Europe.” Kakanien Revisited. http://www.kakanien-revisited.at/beitr/essay/TKamusella1.

- Kelley, Susanne. 2009. “‘Where Hip Meets Habsburg’: Marketing the Personal Story in Contemporary Vienna.” Modern Austrian Literature 42 (2): 61–76.

- Kozuchowski, Adam. 2013. The Afterlife of Austria-Hungary: The Image of the Habsburg Monarchy in Interwar Europe. 1 ed. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Lorenz, Hellmut. 2001. “Die barocke Hofstallungen Fischers von Erlach Fischer von Erlach’s baroque Stables Building.” In MuseumsQuartier Wien: die Architektur – The architecture, edited by Matthias Boeckl, 18–25. Wien: Springer.

- Magris, Claudio. 1966. Der Habsburgische Mythos in Der Modernen Österreichischen Literatur. Translated by Madeleine von Pázstory. Salzburg: O. Müller.

- McClung, William Alexander. 2000. Landscapes of Desire: Anglo Mythologies of Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Meinbezirk.at. “Grünes Licht Für Tiefgarage Heldenplatz.” Accessed March 15, 2017. https://www.meinbezirk.at/innere-stadt/lokales/gruenes-licht-fuer-tiefgarage-heldenplatz-d520463.html.

- Moravánszky, Ákos. 1998. Competing Visions: Aesthetic Invention and Social Imagination in Central European Architecture, 1867–1918. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- MSÖ (Medien Servicestelle Neue ÖsterreicherInnen). 2014. “Serbische Community Zählt Rund 300.000 Personen | Medien Servicestelle Neue ÖsterreicherInnen.” Accessed April 1, 2017, http://medienservicestelle.at/migration_bewegt/2014/03/11/serbische-community-zaehlt-rund-300-000-personen/.

- Netbase. “Netbase t0 Institute for New Culture Technologies.” Accessed April 6, 2017. http://www.netbase.org/t0/intro/03.

- ÖBL (Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815–1950) Band. 8. 1983. Accessed Mar 21, 2017. http://www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_R/Raisp-Caliga_Erwin_1862_1915.xml.

- Popescu, Ruxandra Irina, and Răzvan Andrei Corboș. 2011. “Vienna’s Branding Campaign – Strategic Option for Developing Austria’s Capital in a Top Tourism Destination.” Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 6 (3): 43–60.

- Popović, M. 1983. “Projekti Nikole Doksata de Moreza Za Rekonstrukciju Beogradskih Utvrđenja 1723–1725. Godine.” Godišnjak Grada Beograda XXX: 39–57.

- Prokopovych, Markian. 2009. Habsburg Lemberg: Architecture, Public Space, and Politics in the Galician Capital, 1772–1914. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

- Raiffeisen Immobilien. “Am Kaiserforum 1010 Wien.” Raiffeisen Immobilien. Accessed April 3, 2017. http://www.raiffeisen-immobilien.at/projekt/am-kaiserforum.214 /.

- Reynolds-Cordileone, Diana. 2015. “Displaying Bosnia: Imperialism, Orientalism, and Exhibitionary Cultures in Vienna and Beyond: 1878–1914.” Austrian History Yearbook 46 (April): 29–50. doi: 10.1017/S0067237814000083

- Riesenfellner, Stefan. 1998. Steinernes Bewusstsein I: die öffentliche Repräsentation staatlicher und nationaler Identität Österreichs in seinen Denkmälern. Wien: Böhlau Verlag.

- Rotbard, Sharon. 2014. White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa. London: Pluto Press.

- Ruthner, Clemens, and Tamara Scheer, eds. 2018. Bosnien-Herzegowina und Österreich-Ungarn, 1878–1918: Annäherungen an eine Kolonie. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

- Sauer, Walter. 2002. k.u.k. kolonial. Habsburgermonarchie und europäische Herrschaft in Afrika. Wien: Böhlau.

- Sauer, Walter. 2012. “Habsburg Colonial: Austria-Hungary’s Role in European Overseas Expansion Reconsidered.” Austrian Studies 20: 5–23. doi: 10.5699/austrianstudies.20.2012.0005

- Schlipphacke, Heidi. 2014. “The Temporalities of Habsburg Nostalgia.” Journal of Austrian Studies 47 (2): 1–16. doi:10.1353/oas.2014.0023.

- Schmutzer, Kurt, and Christian Feest. 2013. “Brazil in Vienna: Encounters with a Distant World.” Archiv Weltmuseum Wien 63 (4): 266–285.

- Schorske, Carl E. 1980. Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York: Vintage.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence. 1994. Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

- Statistik Austria. “Bevölkerung nach Migrationshintergrund und Geschlecht 2015 und 2016.” Accessed April 2, 2017. https://www.wien.gv.at/statistik/bevoelkerung/tabellen/bevoelkerung-migh-geschl-zr.html.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2008. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology 23 (2): 191–219. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2008.00007.x.

- “Vienna 2016: Imperial & Contemporary.” Vienna’s B2B Service for the Tourism Industry. Accessed April 6, 2017. https://b2b.wien.info/en/press-media-services/pressservice/2015/09/09-ar/vienna-2016-imperial-and-contemporary.

- Vogt, Adolf Max. 2000. Le Corbusier, the Noble Savage: Toward an Archaeology of Modernism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Walton, Jeremy F. 2016. “Geographies of Revival and Erasure: Neo-Ottoman Sites of Memory in Istanbul, Thessaloniki, and Budapest.” Die Welt des Islams 56 (3–4): 511–533. doi: 10.1163/15700607-05634p11

- wien.at. 2015. “Regierungsübereinkommen 2015 – Wien hat Kultur: für alle, mit allen.” Accessed April 2, 2017. https://www.wien.gv.at/politik/strategien-konzepte/regierungsuebereinkommen-2015/wien-hat-kultur/.

- “Wiener Akademikerball.” Accessed March 17, 2017. http://www.wiener-akademikerball.at /.

- WienTourismus. 2014. Tourismusstrategie 2020. Wien: Wientourismus.

- WienTourismus. 2017. “2016: Knapp 15 Millionen Nächtigungen Für Wien.” Tourismuspresse, Accessed April 3, 2017. https://www.tourismuspresse.at/presseaussendung/TPT_20170125_TPT0003/2016-knapp-15-millionen-naechtigungen-fuer-wien-bild.

- Willink, Robert Joost. 2011. The Fateful Journey: The Expedition of Alexine Tinne and Theodor Von Heuglin in Sudan (1863–1864). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wolff, Larry. 2012. The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

![Figure 4. Milan Mijalkovic ‘Worker with Sledgehammer’ from the series ‘Workers’ (2015) [left] (c) 2015 Milan Mijalkovic. Ongoing restoration work on the Neue Burg using whitewash mixtures, with the unrestored facade partly visible on the ground floor (2017) [right]. Photograph by author.](/cms/asset/98aaf962-e77d-445d-8e52-863bffac49bc/ghan_a_1617709_f0004_oc.jpg)