ABSTRACT

This chapter draws on the papers in this volume to help develop a global comparative perspective on religion and war. It proceeds by establishing two forms of religiosity: immanentism, versions of which may be found in every society; and transcendentalism, which captures what is distinctive about salvific, expansionary religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. This chapter does not suggest that either immanentism or transcendentalism enhance the likelihood of collective violence in themselves. It does, however, argue that these types of religiosity are distinctive in how they drive war, allow enemies to be identified, and rationalize or legitimize collective violence. Some of the paths by which societies may become more bellicose (prone to war) or martial (heavily shaped by a military ethos) are sketched out and certain elective affinities between imperial expansion and transcendentalist systems are proposed. The place of Confucianism in this interpretative schema is discussed towards the end. Many scales of comparison are considered throughout, especially whether the categories of ‘transcendentalism’, ‘monotheism’ or ‘Christianity’/‘Islam’ afford the most comparative insight in understanding patterns of violence.

The purpose of this Afterword is to use the assembled papers to help develop a global comparative perspective on religion and war. There are many reasons why this might have unsettling results from the perspective of the specialist. If comparison is arguably an intrinsic feature of the entire anthropological endeavour, it is one routinely subject to angst and rarely pursued at the level of creating truly global forms of analysis (Hausner Citation2020; Freiberger Citation2019). Thus, the recent ontological turn has focused attention on the way that the emic conceptions of the fieldwork society can and should transform the etic conceptions used to interpret it (Holbraad and Pedersen Citation2017). However, this normally involves an interplay between the ontological orders of the analyzer and the analyzed; it is a quite different task to construct terms that could take be put to work across dozens of far-flung cases.Footnote1 As for global history, while the majority of works tend to proceed by tracing connections, fruitfully transgressing the boundaries between societies and regions, the comparative perspective demands that we identify distinct case study units to set against each other – thereby running head-on against the whole problem of delimiting cultures, societies or even civilizations which has troubled anthropologists since at least the 1980s.Footnote2 Moreover, while the specialist frequently considers their role to be that of complicating popular generalizations and easy summations of their field, the comparativist must insist that some form of generalization – however subtly deployed – is the only route by which a truly global vantage point may be constructed. The global comparative method thus offends many of the instincts that have prevailed in the past generation in both history and anthropology, and this must be underscored from the outset.

What do we gain, by it then? Clearly, in this case, we will derive a sense of just how divergent cultures of violence may be – and therefore whether any given case is idiosyncratic or run-of the-mill. But we also acquire one of the few tools available for making progress on the question of causation. Philippe Buc (preface) is quite right to point out that our master question cannot be that which animates much public discussion – does religion in general exacerbate or reduce violence? – given that it is frankly impossible to answer. The question must rather be: how does religion shape violence. More specifically, the question addressed in this Afterword is: do different types of religion shape violence in patterned ways? The types I have in mind derive from a distinction between ‘immanentist’ and ‘transcendentalist’ forms of religiosity, which will be described below (and as sub-categories of the latter, between the monotheist and the Indic). It is not suggested here that immanentism or transcendentalism can be associated with greater or lesser degrees of bellicosity. But they do offer a framework for understanding certain patterns in how religion shaped the conduct of war, how enemies were identified, and the manner in which violence was justified and emotionally processed.

What is religion and what causal value does it have?

The introduction offers a reasonable solution to the venerable problem of defining religion, deploying James Benn’s account of it as

a set of practices and discourses shared with greater or lesser intensity by the members of a human group, structured by a community, institution or both. These practices and discourses deal with non-human entities or non-living humans to whom are attributed powers not normally available to human beings.

As simple as it is – we shall have cause to complicate it soon enough – this definition has many virtues. Note that it does not at all entail that the people in question themselves deploy a concept of ‘religion’ or of belonging to ‘a religion’ – notions frequently noted for their absence in ethnographic accounts. In this light, William Cavanaugh’s argument (Citation2009) against the possibility of identifying the role of religion in the early modern European ‘wars of religion’, insofar as contemporaries themselves did not distinguish between the religious and the political – appears a little puzzling, as Buc notes.Footnote3 Cavanaugh’s point reflects a quite widespread misapprehension that the applicability of etic concepts rests on their equivalence to emic ones. The point becomes much clearer once we move to the global perspective afforded by this volume, for it is surely obvious that societies such as the fifteenth and sixteenth-century Aztecs or twelfth-century Chinese elites did not have concepts which were straightforwardly equivalent to twenty-first-century notions of religion and politics. We understand well enough that these are outsiders’ terms, deriving their meaning from our world rather than theirs, and deployed for that reason.

In the fallout from 9/11 and the waves of organized violence perpetrated in the name of Islam, a dangerously reductive understanding of the way religion relates to violence took hold of some parts of public discussion. In reaction, many commentators and politicians were moved by the urge to take religion – even ideology itself – out of the picture and therefore away from the clutches of Islamophobes and demagogues.Footnote4 Various assumptions were drawn on in the process: that all major religions are essentially similar in their core features; that they are benign in effect (that is, if ‘correctly’ followed; malign effects being ipso facto corruptions of the faith); that this is the result of their ethical focus and pro-social function; and that to be truly religious is to be knowledgeable of the teachings comprising the core of the tradition and to adhere to mainstream interpretations of them. These all reflect what I shall describe as deeply transcendentalist understandings of religion.Footnote5 Connected to this was a focus on the inner motivations behind any activity, which were then measured up against a very high bar for what counted as ‘religious’. In truth, not much behaviour commonly granted as religious would survive being traced back to the muddy ground of motivation in this way: is attending a church service ‘religious’ if what finally levered you out of bed in the morning was the chance to show off your fine new Sunday best to the family down the road? Another approach focused on non-religious motivations and structures for a quite different reason, namely an unwillingness to grant that religion could really be a causal agent in its own right, when surely it was economic and social dynamics that were the real engines of history. Thus it could not be mere ideas, or stories, or values or metaphysics that drove terrorism but had to be oppression, criminality, alienation, and geopolitical inequality – as if the ideological and material conditions of existence were not deeply inter-twined, as if the meaning of our predicaments was not a function of the larger narratives and symbolic orders by which we live. If the manoeuvres above were enabled by transcendentalism, this one was a legacy of secularization (in the sense proposed by José Casanova and others).

These arguments should sit uneasily with the perspective of Anthropology, which has long worked with greatly expanded – or indeed exploded – concepts of religion, while remaining predominantly inimical to materialist and universalist reading of human nature. Meanwhile in history too, in part as a long legacy of the influence of anthropology itself from the 1960s and 1970s, the influence of religion or popular culture as a causal power or generative structure has long been recognized. At the same time, it is presumably no less evident to any scholar doing serious work in this area that if we do choose to divide up the world into the ‘religious’ and the ‘non-religious’, we will be immediately obliged to put the two back together again, recognizing that these qualities interlace in an intimate manner – and that mono-causal explanations are therefore absurd.Footnote6 It is true that this leaves much room for debate as to how far the particularities of any religious system shape the enactment of violence and how far religious discourse is merely epiphenomenal – drafted in to legitimize behaviours that would have occurred anyway for quite other reasons. Hence, the preoccupations of this volume.

For the more distant past explored by these chapters, political pressures exert much less (though hardly non-existent) force, and so it becomes easier to acknowledge that dark, terrifying, and uneducated acts may be no less ‘religious’ than more respectable ones – which is only to say that they are bound up with peoples’ relationships with the metapersons who have ever surrounded them and the social arrangements founded on these relationships. Thus religious preoccupations, ideas, and norms are deeply implicated in efforts to capture an enemy in battle, and then flay his skin off in precise stripes while he is tied to a stone; in having thousands of people executed at the hands of their own tribesmen; in the anger of an urban mob tearing apart traitors; or in the slow tortuous death of a captive carried out by taunting women and children.

Since at least Durkheim we have understood that a principal reason why religion has been such an ineradicable part of the human existence is its capacity to create both community and hierarchy: to generate a communal sensibility through ritual participation and mutual purpose, and to generate inequality through its registers of purity and divinity. Until very recently in world history, it was primarily by reference to metapersons and the powers they were held to command that social groups were formed. Let us consider the case of an Iroquois raiding party, intent on exacting revenge in order to avenge the aggrieved ancestors. The raid probably has a psychological basis as an expression of grief and anger, and a political utility in replacing lost tribal members, and it is obvious that the social power of religion is deployed to serve these ends – that narratives uniting people to action are more compelling when they invoke the feelings of the (living) dead. This is not to yield whole-heartedly to functionalism – for the results may be chaotic – and nor is it a form of reductionism – for these understandings may then shape or override the psychological and political dimensions in turn. It does entail, however, conceiving the production of social groups and political projects as fundamental dimensions of what religion is and does rather than as enterprises that are somehow extraneous or even antithetical to its most authentic forms.Footnote7 A long line of anthropology has explored the inextricability of state and cult, from A. M. Hocart (Citation[1936] 1970) onwards. This has recently been revivified in Marshall Sahlins and David Graeber’s On Kings (Citation2017), and their striking argument that, anthropologically and historically, the primary form of sovereign authority was that wielded by ancestors, spirits and deities; the development of ‘actual’ states and hierarchies was something that followed in a subset of human societies.

The foundational categories

The theoretical inspiration for the core categorizations deployed here derives from Axial Age theory. The Axial Age was Karl Jaspers’ (Citation1953) name for the period in the mid-first millennium BCE when a series of largely disconnected cognitive revolutions broke out across the settled cores of Asia, giving rise to the systems of thought that dominated human history thereafter, including all the monotheistic faiths, the Indic traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism, the Chinese traditions of Daoism and Confucianism, and Greek philosophy. In Anthropology, this field of scholarship has only had intermittent and minor influence, most recently in the works of David Graeber (Citation2011) and Joel Robbins (Citation2012), and before them in certain writings of Gananath Obeyesekere (Citation2002, Citation2012) and Stanley Tambiah (Citation1986).Footnote8 Indeed, it is only really within the historical sociology of religion, for example in the works of Robert Bellah (Citation2005, Citation2011) and Shmuel Eisenstadt (Citation1986), that it has achieved something like mainstream influence.

Drawing on this literature and using it to think through a range of historical and anthropological case material, I have suggested that one reason why the problem of defining religion persists is because it strains to cover two quite distinctive phenomena (Strathern Citation2019). The default mode is immanentism. This may be defined in terms of ten characteristics, which do not all need to be listed here. In essence, immanentism is based on the understanding that any form of flourishing requires productive relations with metapersons (ancestors, spirits and deities) (Strathern Citation2019, Chapter 1). Either the simple definition of religion given by Tylor, or the more comprehensive one provided by Benn, therefore, work just fine here. These metapersons are, in an important sense, profoundly immanent in the world and may choose to bestow or withhold the powers that allow the fields to be fertile, the sick to heal, and battles to be won. They tend to be defined by their sheer power rather than by their relationship to the ethical sphere. And everywhere humans attempted to communicate with them through the mechanisms of ritual, above all sacrifice. Immanentist systems do not look back to the revelations of an historical great teacher, they are not founded in canonized texts, and do not demand labour in the inner lives of individuals.

Underlying the universality of many features of immanentism are presumably evolved features of the human mind such as a bias towards social reasoning or agency detection. We also find various features that are surprisingly widespread in disconnected immanentist systems, even if they are not definitive of the entire genre. For example, Gabbert notes that the Iroquois and Huron (a) imagined that when people died they became ancestors who exerted a great power to influence the lives of the living for good or ill, (b) that their afterlife was essentially similar to this life, and (c) that death was generally not perceived as ‘natural matter’ but was frequently attributed to the ill-intentions of other agents. These same intuitions could be found in West Africa and Melanesia as much as in North America. Thus ‘immanentism’ as a category has the capacity to disrupt region-based generalizations about religion and is certainly difficult to explain in terms of diffusionist or connected forms of global history.

Yet in Asia, especially from the mid-first millennium BCE onwards, certain traditions of thought began to emerge that yielded a very different enterprise: transcendentalism. Eventually, this came to define the monotheistic and Indic forms that now dominate the world, especially Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and certain strands of Hinduism.Footnote9 Transcendentalism is oriented towards liberation from an inherently unsatisfactory mundane sphere, attaining an ineffable future state of being representing the highest end of man.Footnote10 Attaining this salvation is associated with assent to universal truth claims, which it is understood that others will wrongly reject, and to a defined set of ethical principles, which function as a guide to the interior reconstruction of the self. So: soteriology, epistemology, morality, interiority.Footnote11 The core transcendentalist revolutions took place as movements entirely disconnected with the state. In their most definitive forms, they looked back to the uniquely authoritative teachings of a unique individual who had articulated a vision of meaningful order that far transcended the realm of any one state or society. Over time, these visions were canonized into sacred texts that were deployed to curtail the significance of subsequent revelations. This opened up the potential for religion to reproduce itself through the ‘doctrinal mode’ (Whitehouse Citation2000), driven by routine participation in rites of indoctrination and the extension of literacy. And it created clerical elites who evolved unusually strong institutional traditions; they preserved a distinct autonomy from the state and a certain capacity to hold it to account.

The role played by morality is particularly important to our discussion because all the transcendentalist traditions insist upon an emphatically universal ethics. All enshrined a version of the ‘golden rule’ such that all other human beings or even sentient creatures were potentially inducted into an overarching moral community. This in turn necessitated a profound problematization of violence. In this, and so many other ways, the quest for salvation served to flip the normal criteria of human flourishing upside down, endowing status and soteriological glamour upon suffering, celibacy, poverty, death and defeat.Footnote12 This was a vision that set out to jar common sense; they were ‘offensive’ (Gellner Citation1979) insofar as they were primed to challenge and defeat alternative worldviews. The virtuosos of this new ethos were renouncers and monastics – and there was a vital sense in which these quintessentially non-violent individuals were deemed superior to kings. In many cases, they re-embodied the charisma of the founding teachers as rebels against conventional morality. Thus, Jesus was not a warrior but a sacrificial victim, and Buddha may have been born a prince but he renounced that status and all it stood for.

However other characteristics of transcendentalism pointed in a quite different direction. The soteriological desideratum could serve to subordinate all concerns regarding the suffering inflicted in this plane of existence, which was now an unsatisfactory and corrupt dimension of reality. And this formed the premise for a very powerful legitimation of violence visited upon those who failed to subscribe to the salvific project or were seen to undermine it from within. Therefore, what several theorists of religion and violence point to as the absolutist quality of religion (Cavanaugh Citation2009, 18–26) is actually a property of transcendentalism per se. There were in fact several features of transcendentalism that pulled hard against its potential to implant pacific norms. The moral focus of transcendentalism, its formidable institutional structures, its reified scripture, and its inherent portability combined to generate new opportunities for developing highly charged group identities which could be shared across vast and dispersed imagined communities. In other words, just as they have the potential to dissolve all ascriptive identities of clan, kin, polity into a universal humanity, transcendentalist systems also allow living beings to be divided up between those who have seen the light and those who remain blind to it. It must be underlined very heavily that this was far more profoundly a feature of the monotheistic traditions than it was of the Indic variants – a point that is reiterated at various points below.

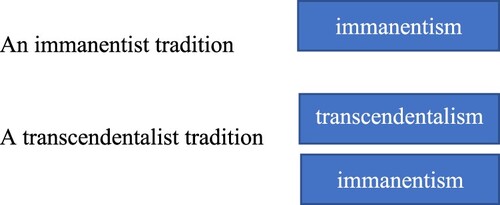

We have been referring to religious systems as either ‘immanentist’ or ‘transcendentalist’, but this conceals something rather important, that conveys.

It is true that throughout most of human history, immanentism has persisted in forms that are essentially untouched by any admixture. This is represented here by the Aztec and Iroquois/Huron cases.Footnote13 But transcendentalism is different; it is inherently unstable and can only materialize as an amalgamation with immanentism. This is, indeed, one reason why we shall have to be subtle in identifying any implications for the nature of violence. For all transcendentalist traditions necessarily carry within them a whole array of immanentist practices and understandings – including a tendency to be deployed as a form of battle magic. Thus, we may find objects, rites, prayers associated with the Christianity of Medieval Europe and the Islam of the Almohad and Almoravid empires, which are deployed to bring military good fortune. But these two cases display a further distinguishing feature of transcendentalist traditions: just as they are liable to be transformed from within by the basic pull of immanentism, so they also produce movements that attempt to enhance the dominance of the transcendentalist elements, from the foundation of ascetic-monastic orders to the appearance of arguments insisting upon adherence to the literal truth of scripture. All this may be placed under the heading of ‘reform’. How Confucianism in Song China fits into this taxonomy, meanwhile, will require its own discussion.

It ought to be emphasized that many different scales of cultural difference will need to be brought in and out of play to help illuminate any given problem. At the top end of the scale we may conceive of universals of human behaviour; just beneath that resides the immanentist/transcendentalist dichotomy; the latter may be divided into the monotheistic and the Indic forms; while monotheism may be divided into Islam and Christianity. But we may well need to go on, of course, for the vast and diverse world of ‘Islam’ may be divided into many different regional, sectarian or chronological units, of which this volume presents us the cases of the Almohads versus the Almoravids versus the post-Ummayad Iberian polities. Yet each of the latter may in turn be broken down into different phases, dimensions and conflicting discursive strands – and so on. These are all no more or less than heuristic devices. Indeed, we may wish to draw our boundaries quite differently – but, in order to appreciate cultural difference, draw boundaries we must. The trick for the comparativist is to work out which scales of differentiation have greatest explanatory power in any given task. Specialists are naturally best placed – and naturally inclined – to emphasize the force of the local, and, indeed, for some issues, the most pertinent scale will be extremely local indeed. But only the comparative perspective will help us determine if that is so.

Immanentism

Since so much of the literature on religion and violence is, in effect, about the transcendentalist traditions – especially, the world religions of Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism – we may need to begin discussing immanentism in terms of what it is not. Quite simply, immanentist traditions are not used as the basis for group self-identification in themselves. Has there ever, in the whole of the record of history, been a war fought in the name of an immanentist religion? The question is almost an absurdity: immanentist systems do not have names nor do they tend to generate emic concepts equivalent to that of religion. If we wish to bring them into legibility we have either to borrow derogatory and generic terms created by transcendentalisms (pagans, idolaters); invent rather empty placeholders such as ‘local religion’ or ‘traditional religion’; or simply add the term religion to their ethnonym or culture name – viz, Nuer religion (Strathern Citation2019, 45–47). The issue is a little more complex than the rhetorical question above implies, for groups may fight in defence of their inherited religious practices even when they don’t conceive of them as constituting an isolable and coherent system.Footnote14 But note that this happens most visibly when monotheistic societies violently intrude upon them or claim the conversion of their rulers. Immanentist systems are not premised on the falsity or malignancy of other peoples’ gods, and often allow those other gods to be assimilated to or translatable in terms of their own.Footnote15

Indeed, it is only a little less redundant to ask whether war is shaped by religion in immanentist societies, for what we bracket out as ‘religion’ is a dimension of every facet of existence, and certainly vital to any attempt to achieve success.Footnote16 Gabbert cites a Jesuit report on the Iroquois that ‘their superstitions are infinite; their feasts, their medicines, their fishing, their hunting, their wars – in short, almost their whole life turns upon this pivot’. For immanentism is a means of effecting whatever ‘social work’ needs doing – whether that be allowing trade between strangers or treaties to be ratified through the swearing of oaths, entrenching hierarchies of age and gender, and so on. It could be used to prevent egotistical individuals rising to positions of permanent authority, or contrarily become the essential means by which sacred chiefs and kings were elevated. Among this infinitely extendable list, then, was the business of creating either war or peace. Reid observes that non- or pre-Abrahamic religions could serve to restrain the exercise of violence and might be ‘concerned primarily with the preservation of life, and the maximisation of fertility and productivity’. True, but immanentism may be pressed into the service of domination, predation and revenge no less readily.

One of two principal forms of group-cohering religiosity identified by Harvey Whitehouse (Citation2000), the ‘imagistic mode’, is particularly characteristic of immanentism. Whitehouse and McQuinn (Citation2013) point out the way in which ‘rare and traumatic’ one-off ritual experiences fuse the identities of participants to create ‘intense cohesion within small cults’, which in turn may enhance ‘hostility and intolerance towards outgroups’ and the capacity for self-sacrificial violence. The prototypical example would be the terrifying and painful ordeals at the centre of many initiation rituals, which become lodged as an enduring reference point in episodic memory.Footnote17 The deliberately transgressive practices (including cannibalism) associated with membership of and authority among the war-bands known as Imbangala in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Angola are a particularly direct example (Heywood Citation2017, 119–124) of the potential relationship between imagistic experience and violence.

One of the advantages of such a comparative perspective is that the essentially political concerns that inevitably build up within any one field of scholarship can be gently laid to one side. Thus, Reid observes that invoking a ‘spiritual’ framework for African agency in matters of armed violence could be taken for a rehearsal of racialized Western colonial-missionary tropes – but his chapter sensibly endorses the importance of such a framework nonetheless. The point is that once we see this logic as structuring countless settings throughout world history, and as described by many diverse commentators, then such anxieties fizzle away.Footnote18

The above discussion has been conducted, of course, in highly etic terms. The perspective of the actors themselves would revolve around the need to engage in productive relations with metapersons.Footnote19 For the peoples of the Eastern Woodlands of North America, this involved sacrificial rites. As Gabbert notes, ‘the torture and killing of captives were not just secular affairs to frighten off the enemy but often considered sacrifices to deities or means to renew the spiritual strength of lineages, clans and villages’. The capture of enemies (rather than their slaughter) was therefore the chief means by which a warrior’s skill was assessed. The Iroquois seem to have dedicated prisoners as sacrificial victims to deities of the Sun or Sky, or the god of War, and in return they would be blessed – with victory. The practice of war, the taking of victims, and their dispatch were all highly ritualized affairs. There was further a sense that the animative powers of the victims – often held to reside especially in the heart – could be transferred to their sacrificers.

Does it need spelling out that much of this would apply no less well to the Aztecs? Indeed, we could find versions of these basic postulates at work across the entire spectrum of political hierarchicalization. Close to one end of that spectrum would come the essentially acephalous societies of the Iroquois and Huron, while the Aztecs would hold down the other end as a great imperial order; midway between them would come the Polynesian societies of the Pacific such as Tahiti, Tonga and Hawaii. (Perhaps all belonged to a broader culture region taking in the Americas and the Pacific, but we certainly see elements of these ideas in many other immanentist societies worldwide.). In the Pacific by the eighteenth century, ‘aristocratic’ families had begun to distinguish themselves from commoners and slaves, complex forms of chiefly authority had arisen, and in the case of Hawaii, according to some analysts (Kirch Citation2010), something like archaic statehood and sacred kingship had emerged. We find across this region that the ambitions of chiefly contenders were expressed through relations with bloodthirsty gods of war. In the case of Tahiti, this took the form of a new kind of aristocratic cult society (the ‘ariori) devoted to ‘Oro (Newbury Citation1980) while the attempts of Kamehameha to unite the Hawaiian islands led to the elevation of the war god Ku (Sahlins Citation1992; Strathern, Citationforthcoming). Both demanded sacrificial victims and conferred victory while the rite of sacrifice itself was held to impart mana to the sacrificers.Footnote20

The Aztecs represented the pinnacle of imperial projection in Mesoamerica by the fifteenth century, and their tutelary god of the Aztecs, Huitzilopochtli, was also of course a god of War, indeed ‘an enemy of peace’. The functioning of the entire cosmological system, the pulsation of life-energy throughout every aspect of it, depended upon the shedding of blood, whether through the sanguinary rites of auto-sacrifice or the dispatch of war captives. Hence warfare became primarily a matter of capturing enemies rather than killing them – for entirely pragmatic reasons, note, given the local understandings concerning the metapersons whose affairs were also involved.

Caroline Dodds Pennock is surely right to argue that this ideology both reflected and drove the state’s will to power, just as Iroquois beliefs about the vengeful dead were both an obvious transposition of fairly universal reactions of grief and anger to the plane of the ancestors and a cultural complex that drove the incessant cycles of raid and counter-raid – at one and the same time. That is to say, if religion is a means of doing ‘social work’, its particular forms also shaped understandings of what ‘social work’ needed doing (as in ‘practice theory’: Ortner Citation1984)! Most of the time, presumably, this work was operated through organic dynamics of which the actors involved were essentially unaware, but we do not need to rule out more deliberate interventions. At certain moments, the hand of a more calculating designer may be discerned – as with the ‘consciously manufactured’ official histories of the Aztecs (Pennock Citation2022).

Transcendentalism

Consider Huitzilopochtli, the tutelary deity of the Aztecs, emerging from the womb fully arrayed and beheading his sister and hunting down his brothers, and then driving his chosen people onwards to ceaseless war and conflict. This is a vivid image of the way that projects of violent expansion in immanentist settings are likely to be relatively ‘non-euphemized’ (Strathern Citation2019, 189–190) by their translation to the supernatural sphere. Contrast with the god of the Spanish conquistadors: a crucified victim of state violence. At issue is not the actual propensity to violence, which the Spaniards indulged in with extraordinary avidity in the New World, while the Aztec insistence on ritual killing rather than battlefield slaughter may have limited the mortality of battle. But the rigmarole of the Requerimiento – a lengthy document read out in Spanish to indigenous peoples inviting them to receive evangelization or face an attack, the absurdities of which were fully evident to contemporaries – the famous debates at Valladolid around the rights of the conquered peoples, the impassioned writings of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas (Citation[1542] 1992) castigating the horrors of empire, the establishment of a permanent council engaging with moral theology, a ‘Board of Conscience’ for dealing with imperial matters on the part of the Portuguese (Marcocci Citation2014) – all these are not mere trivia either. They represent an important feature of how violence was cognitively and emotionally processed.Footnote21 Was all this either irrelevant to or merely a minor burden on the pursuit of power?

A certain strain of cultural evolutionary theory and cognitive psychology (Norenzayan Citation2013; Henrich Citation2020) has developed a strongly functionalist reading of world history in which the emergence of ‘big gods’, moralizing religions and salvific teachings was primarily a response to the need to develop forms of cohesion over increasingly large-scale and complex social orders.Footnote22 It remains to be seen how well this approach copes with the true diversity of historical evidence.Footnote23 Certainly, there can be no straightforward relationship between successful large-scale political projects and the world religions or transcendentalist religious systems. The latter created their own distinctive forms of disunity, which are given great emphasis in the analysis below.Footnote24 After the conversion of Constantine, the quarrelsome bishops ensured that there would be ‘ever-escalating faction, division, and violence among the churches’.Footnote25 And, as has been pointed out (Baumard and Boyer Citation2013), thereafter, in a process that culminated in circa 500 CE, the Western half of the empire was infiltrated or invaded by immanentist peoples, destroyed as a polity, and eventually transformed into a plurality of so-called sub-Roman barbarian kingdoms.

Nevertheless, the appeal of transcendentalist traditions for imperial systems – whatever their ultimate effect – seems to be a more difficult to deny (Strathern Citation2019, 132–141). Despite the fact that the major forms of transcendentalism arose outside the state and even in opposition to it, they were adopted by the imperial formations that seeped over Eurasia in the centuries before and after the advent of the common era, and were then increasingly spread over the world. It makes sense to consider if there is a structural element undergirding this pattern. There are, moreover, some striking counter examples to the case of Rome, (the decline of which must naturally take into account multiple lines of causation for which religion is largely irrelevant). There is no greater example of the extraordinary enhancement of social power generated by the adoption of a transcendentalist system than the first few generations of Islamic history, in which the tribes of the Arabian peninsula suddenly overcame their internecine history as they took on the teachings of Muhammad and surged outwards to create a huge imperial zone with astonishing rapidity (Hodgson Citation1974).

Partly on these grounds, it is worth exploring what an elective affinity between transcendentalism and empire might look like. The conjecture is that this affinity rested upon a janus-faced quality of transcendentalism, which in turn corresponded to two conflicting imperatives of imperial expansion. On the one hand, empires depend on the successful deployment of violence, rolled out along their frontiers and against rebellious elements alike, to which the capacity of transcendentalism to mobilize fighters and glorify their deeds spoke loud and clear. On the other hand, empires also endeavour to create expansive zones of internal peace, suppressing cycles of inter-clan retribution, eruptions of parasitical banditry, or provincial rebellions. Hence the utility for the ‘other face’ of transcendentalism: its capacity to problematize violence, its explicit moral codes, its association with literacy and education and legalism, its machinery of self-discipline. All this chimed with the reservation of the legitimate use of violence for an imperial elite.

These rather abstract speculations do not imply that imperial forms necessarily produce such transcendentalisms as a matter of evolutionary necessity: these traditions are the product, ultimately, of particular Asian intellectual spasms, and their circulation remained confined to Eurasia and parts of Africa until relatively recently. In the Americas until the arrival of Catholicism, for example, expansionary states pressed immanentist forms into the service of imperial supremacy – as the Aztec example makes plain. Still, it does seem as if the Aztec religious system neither aimed at nor achieved the kind of integration of consciousness and loyalty across its constitutive parts that polities might achieve through the expansion of traditions such as Christianity or Islam (Brumfiel Citation1982).Footnote26

The characterization of transcendentalism presented above echoes a diagnosis that Buc (Citation2015, 12, 23; Citation2020) has made elsewhere about Christianity in particular: that it was structured by a dialectic between bellicism and irenicism. Buc observes that the utopian dimension of Christianity inhibited some of the typical forms of conflict resolution present in traditional (aka immanentist) societies, and also compares it to ‘secular’ revolutionary ideologies in this regard, including that which animated the French Revolution.Footnote27 In pre-modernity, the closest phenomena to modern revolutionary movements were millenarian movements, which I have referred to as a global type as ‘supernatural utopianism’.Footnote28

However, the larger point here is that the salvific urge, wherever it is expressed, always implies a form of utopian thinking, even if the utopic state is only to be realized in the afterlife rather than some imminent transformation on earth. And when set against that utopic state, any mundane suffering necessitated by the quest for its attainment could come to seem of lesser significance. A version of this argument may be found in Shmuel Eisenstadt’s work (Citation2000), which likewise traces the potential for sharply defined, large-scale, ethicized identity-creation back to the fundamental features of the Axial Age revolutions. Eisenstadt also, however, points out that this was much more strongly a feature of the monotheistic variants than of the Indic. In particular, he notes that the Christian church represented an unusual setting in which a concept of orthodoxy – and therefore heresy – could both harden and come to be enforced (Citation2000, 29).

Eisenstadt, therefore, brings in and out of play at least three scales of comparative unit: transcendentalism; monotheism; Christianity. Jan Assmann (Citation2010; Buc Citation2021) has made one of the most powerful interventions in emphasizing the second of these categories. For Assmann, the visions of Jewish prophets who translated the authoritarian demand for loyalty to a sacred king to the loyalty to a jealous heavenly lord constituted a major break in world history. The Israelite covenantal theology of Deuteronomy established the ‘Mosaic distinction’ by which a special people were defined by their unmediated relationship with God, a relationship that excluded all other peoples who were now held to worship false gods. Thus was born ‘total religion’ in which the will of god subsumes and directs all aspects of culture (Assmann Citation2014). The results of this move have resounded throughout all the Abrahamic faiths to the present day. Thus, Reid can report on the way the Ethiopian chronicle Kebre Negast revelled in sanctified total violence, which was ‘justified by God and the Covenant’ and ‘a mandate to spread fire and devotion among the supposedly savage peoples surrounding them’, or that under Zara Yaqob (1434–1468) pagans risked the death penalty. Fundamental to this culture of violence is the deep ethicization and epistemological ‘offensiveness’ inherent to the Mosaic distinction. Jehovah is infinitely more powerful than other deities, yes, but the crucial point is that he the only true deity, that the gods of other peoples are wicked, false, demonic. They are the enemies of God, and His enemies are potentially, the enemies of all right-thinking people. Reid indeed is willing to argue that the Abrahamic faiths introduced not only ‘a much wider and deeper set of justifications for killing and destruction than locally rooted cosmological and spiritual orders and cultures’ but ‘new levels of heightened violence and martyrdom and destruction’.

Of the three potential scales of comparison, Buc’s work (Citation2016b, Citation2020) has also recognized the analytical value of both monotheism and Western Christianity per se. However, in this volume, the chapters by Buresi and Buc adopt slightly different methodological approaches. Buresi’s study of the three contrasting case studies (the Andalusian Taifas, the Almoravid emirate and the Almohad caliphate) underlines the internal diversity of Islamic discourses and practices of violence – although it does finish by hinting at an overarching framework that would enable a fruitful comparison with Christianity. Buc considers common themes across mediaeval Catholicism, and in a recent monograph (Citation2015) across the whole vast expanse of Western Christian world history, to illuminating effect. There is no reason why the same may not be attempted for the case of the Islamic world, although one would then need to stand back from both traditions and consider them against the global range of religiosities in order to see the full extent of their common ground.Footnote29 Any such analysis would surely note that the implications of the Mosaic distinction pervaded Muslim history no less profoundly (if no less variously). Buresi’s account of the Muslim Mahgreb hardly needs to marvel at the fact that this was a world in which notions of ‘infidels’ and ‘jihād’ were basic fixtures, or in which religious identities were acute enough to determine taxation rates. These features have become clichés of contemporary political discussion, and therefore it may be a more interesting scholarly task to determine exactly how these did and did not operate in specific cases, how they interacted with secular norms and diplomatic strategies and so on. But from a global comparative perspective, these features represent a highly unusual mentality peculiar to monotheism – that is to say, from a global comparative perspective, banalities may become important truths!

The absurdity of the Spanish Requerimiento is therefore analogous to (and probably has its origins in) a principle that Buresi notes for the Almoravids (a general norm across Islamicate polities), that ‘an invitation to convert or submit to God’s law had to be made and rejected before battle could be joined’ (Seed Citation1995). Here I shall touch on three further points of comparison that arise out of the Catholic Christian and Islamic chapters and which illustrate central features of monotheism: that both cases saw an intense interplay between religious duty as a matter of physical violence and as a matter of inner struggle; that reformist movements might arise which enhanced the distinctiveness of monotheistic violence; that this was connected to the propensity to create schisms among the moral community.Footnote30

For the first point we may start with Buc’s observation that in both the Aztecs and mediaeval Europe cases, domestic populations could be corralled into efforts of deity propitiation to assist their warriors. This does indeed reflect a shared immanentist understanding of ‘spiritual warfare’ across the two cases – in the sense of an entirely instrumentalist attempt to attack the enemy albeit through supernatural means. In both cases, too, forms of ‘pollution avoidance’ or what Buc refers to as ‘semi-asceticism’ on the part of the home front could be mustered to that end.Footnote31 Yet there is a vital difference. In the case of the Aztecs, this seems to have been entirely a matter of ritual propriety; among the Christians it could also be conceived as a matter of ethical-cum-soteriological status.Footnote32

The latter introduces a very different meaning of the term of ‘spiritual warfare’ – as a struggle against inner corruption, against sin, against anything that obstructed the path to salvation.Footnote33 Thus Buc notes the way that monks, as the real militia Christi, ‘fought the critical combat, that against demons and vices’, an imagery that then transferred to the military sphere proper as Crusaders saw their violence as a means to ensure their own salvation and vested themselves in versions of monastic asceticism. Of course, this association between the project of reconstructing the self and reconstructing the world is captured perfectly in the semantic range of jihād. It was, on the one hand, a complete expression of legitimate violence against those outside of the moral community, and was particularly important for the Almoravids according to Buresi. On the other hand, the term could also be used to turn the inner landscape into a field of battle, of ‘asceticism, introspective effort and living memory … “in the path of God” (fī sabīl Allāh)’, which was the form it took in in al-Andalus in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. This intense conflation of soteriological and physical conflict was a structural feature of monotheism over the longue durée.

In both cases too – and this is the second point – movements of soteriological striving were also directed inwards, towards the rejuvenation of the faith. Christianity and Islam were thus characterized by the recurrent eruption of movements of reform – in the sense defined above of re-transcendentalization. Recall that all transcendentalist traditions are unstable amalgamations with immanentism: the Buddha’s tooth relic; Christ as the Word made flesh … (Cannell Citation2005). The point is that monotheistic reformist pushbacks against the recrudescence of immanentism tended to have implications for the exercise of violence too.Footnote34 Mass movements taking in the laity tended to involve a hardening of exclusionary identity boundaries, enhancing the cohesion of the moral community within and the authority to wield violence against those without. The context for the rise of the Almoravids was a project of Islamic reform sweeping over the partially Islamized people of the Sahara, ‘to proclaim the truth, fight against the violations of the Law, and suppress illegal taxes’. It is most apposite that Buresi tells us that one etymology for the Almoravids in Arab sources is those who form ‘a highly cohesive group’. But the Almohads too presented themselves in the idiom of reform. They waged jihād against the Almoravids (the ‘veiled infidels’) themselves, reformulating the concept in the process. In a letter to his followers, the founding figure Ibn Tūmart claimed the following about the Almoravids: ‘Indeed, they have attributed a bodily aspect to the Creator – May He be glorified –, rejected monotheism (tawḥīd), and were rebellious against the truth.’

This is, in effect, a charge of a corrupting immanentism – of paganism. The Almohads would cleanse the world of these stains, thereby upholding the Truth, ‘correcting’ the religion and flattening the earthly world. The authority to mount this challenge derived from the messianic claims surrounding Ibn Tūmart, identified as ‘the Mahdī, the Messiah who was to come at the end of time to fight the forces of the Antichrist’. Such figures have emerged time and again in Islamic history (Buc Citation2020). Reid refers us to a messianic Jihadist operating in Somali territories in the early sixteenth century, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, whose cause to take back Ethiopia from Christians represented both a more aggressive Islam and an ascetic code of self-discipline among his warriors. The Christians themselves understood this logic. In the mid-nineteenth century, Emperor Tewodros of Ethiopia may not have been a messianic figure but his rule combined, again, a reformist edge – this time directed against his own ‘flaccid, parasitic clergy’ – and a ratcheting up of violence against outsiders. Meanwhile, Buc notes the way that in Europe Pope Innocent III ‘linked the “reformation of the universal Church” to the “liberation of the Holy Land”’.

The third point has already been signalled in the material above: that the logic of reform entailed the logic of both purge and schism. Thus, the social power generated by transcendentalizing forces split apart larger collectivities. The Almohads’ reprehension of the Almoravids fissured the broader moral community by generating a harder, smaller one. Buresi explicitly argues that the bloody purge was alien to the life of the Atlas tribes before the introduction of an Abrahamic structure, ‘Old Testament eschatology, via its Qur’ānic interpretation’. One purge by Ibn Tūmart’s successor ʿAbd al-Mu’min (r. 1130–1163), saw, apparently, 32,000 people murdered at the hands of their fellow tribesmen. In Ethiopia, the Europeans brought their wars of religion in the seventeenth century, fracturing the Christian community between converts to the Catholicism and ‘traditionalist’ Orthodox Christians.

Both Islam and Christianity shared an abhorrence of apostates, a crime punishable by death in Islamic law (Sahner Citation2018, 3). Buc raises the question, however, of how far the great taboo against religious side-switching shaped purely political notions of treason too, and therefore the nature of the violence enacted against traitors and turncoats. He shows that it was most emphatically in the Christian West that a cognitive-emotional template of infidelity migrated from the sacred to the secular.

There is no opportunity here to properly address the issue of how far any of these themes could be extended to the wider set of transcendentalisms, which would involve a serious consideration of Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. I will only note that there may be more family resemblances than would appear at first sight.Footnote35 Buddhism, too, provided a means by which enemies of the true upholders of the dharma might be identified as legitimate targets for violence (Strathern Citation2017, 224–225; Frydenlund Citation2017; Deegalle Citation2006) In the sacred chronicle tradition of Sri Lanka beginning with the fifth or sixth century CE Mahavamsa, we find – to use a Christian idiom – an image of a blessed land, a chosen people, and an ultimate destiny for both in the upholding of the Buddha’s dispensation. By this means, non-Sinhala speaking non-Buddhist groups arriving onto the island could be identified as enemies at once sacred and profane. Thus the ‘demala’ – especially associated with Tamil speakers – could be construed as demonic threats and illegitimate co-residents. When the Kalinga King Māgha (1215) who set up rule in Jaffna introduced his Saivism in an assertive manner, the Pali chronicle Cūḷavaṃsa (Citation[1925–1929] 1980, 54–70), accused him of forcing people to convert to ‘wrong views’: ‘Thus the Damila warriors in imitation of the warriors of Māra, destroyed in the evil of their nature the laity and the order.’

Buc observes that

Theology provided Western European culture of war with the figure of the Apostle Paul’s ‘false brother’ the script for the internal enemy, the political traitor and adversary in civil wars, around whom enormous fantasies crystallized themselves, arguably without equivalent in non-monotheistic cultures.

The place of supernatural assistance in war

The immanentist dimension to all transcendentalist traditions has been referred to a number of times. Each of these traditions managed this relationship differently. Contrary to what we see in the Indic variants, there is an important sense in which the Abrahamic deity simply represents an inflation of the theistic urge apparent in any immanentist system – a transition that has left traces in the Old Testament itself. This may be one reason why it was so easy for Christian rulers to consider Him as a magnified god of war. Around the same time as the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine, the ruler of the kingdom of Aksum in Ethiopia, Ezana, became the first ruler of the region to convert to Christianity, and a contemporary inscription conveys the sense that a particularly powerful god of war had now been won over to his side: ‘May the might of the Lord of Heaven, who has made me king, who reigns for all eternity, invincible, cause that no enemy can resist me, that no enemy may follow me!’ (Munro-Hay Citation1991; Strathern Citation2019, 272).

A thousand years later, Reid tells us, the chronicle Kebre Negast represented Ethiopian kings as endowed ‘with supernatural strength and superhuman qualities as they vanquished and conquered’ These deeply immanentist qualities were crucial in allowing such traditions to expand and take foothold in the popular imagination. I have argued elsewhere, for example, that when Christianity was adopted by the rulers of Kongo in the late-fifteenth century, it was initially understood as a species of battle magic, with baptism configured as the principal rite of an initiation cult that conferred the powers of the dead on its members (Strathern Citation2018, Citationforthcoming). This was not at all alien to a major element of Portuguese religiosity, which arrived in Kongo flourishing crusader battle-winning standards, magical relics, and stories of the miraculous visions of St. James coming to the aid of Christian forces. Indeed, when prince Afonso made a bid to acquire the throne in 1506, he was challenged by a ‘pagan’ rival backed up with much greater manpower, and – so our sources insist – St. James did indeed appear in the clouds and drive them back. This miracle became a foundational element of authority of the kings of Kongo from that point who long remained the font of an enduringly Christian influence in the region (Fromont Citation2014).

But this image reminds us of a signal irony. In the introduction, Buc noted that we see such explicit claims of concrete divine intervention in battle in both the Catholic West/Byzantium and Japan – the heirs to the transcendentalist traditions of Christianity and Buddhism respectively – while for our immanentist cases of Sub-Saharan East and West Africa, the indigenous peoples of the Northeast, and the Aztecs, there is, apparently, no record of such visitations outside of the mythical histories! It must be underlined that this not to say that supernatural power was conceived as being any less immanent in warfare in the latter societies. On the contrary, the doings of the metapersons and the operations of cosmic forces were surely omnipresent – why else would Aztec warriors make offerings to the gods before setting out for battle, or their families conduct rituals for them while they were in the field? The gods were carried into battle; and victory depended on the maintenance of the sacrificial system. Meanwhile, the Iroquois preparation for war was a ritual activity: attaining a state of ‘purity’ in the sense of a productive relations with the divinity would grant victory or defeat; they went into battle laden with charms and incarnated spirits. If immanentism is an attempt to secure life from the jaws of death, this was nowhere more apparent than in moments of military jeopardy.

Nevertheless, why this irony? Why is it among the battles of the Christian world and in Japan that the presence of divine power must be made so explicit, so visually immanent as a discrete event? Considering the methodological caution about flexibility in scales of comparison noted above, it may well be that the abstractions of immanentism/transcendentalism are simply unhelpful here, and that we must turn to smaller scales of analysis to gain any insight. Given that it is a particular feature of Christianity, it may simply result from the accounts of the wars of the ancient Israelites described in the Old Testament (Moynihan Citation2021), or be a legacy of the paradigmatic conversion miracle of the Roman emperor Constantine at Milvian Bridge in 312 CE, itself shaped by pagan notions of divine intervention by celestial patrons. While in Japan there may be something about the specific manner in which Buddhism had fused with an essentially immanentist form of kami worship, as Buc hints, that explains the situation there.Footnote38

Still, it is possible to make some speculative suggestions that do return us to some of the implications of the master abstractions. In the immanentist imagination, all the conditions of existence are continually shaped by the operations of supernatural power, from the fattening of roots in the ground to the movements of winds blowing the rain clouds above. Yes, metapersons may materialize in dreams or trances, but they are no less present to the senses in the form of an unusual rock formation, a drought or a skin disease. Our scholarly analyses have not always taken this seriously enough. One reason for this has been the currently high status of genealogical critiques in the academy, which has produced an adverse reaction to categories such as ‘paganism’ and ‘animism’. Recent work in anthropology has realized that this critique constitutes an over-correction which obscured cultural diversity as much as revealing it – and so ‘animism’ has undergone a remarkable renaissance (Descola Citation2013). Immanentism is a broader category than animism but the terms share an emphasis on the this-worldly presence of ‘supernatural’ entities and forces. The scare quotes here signal the emic irrelevance of the nature/supernature distinction in immanentist societies, and in many ways, subject/object distinctions were also submerged (Viveiros de Castro Citation1998). The more we appreciate this, the more that the standard language of material objects ‘representing’ ancestors or deities seems inadequate.Footnote39 And the less the concept of a miracle makes sense.

It is true that Christianity also, in many of its lived realities, saturated the world with supernatural agency. Nevertheless, the sense of God as a more distant entity, one that stood outside of creation and exceeded it in all possible dimensions, may have stimulated a greater need for his manifestation to be made visible, and the approval issuing from his inscrutable will to be made evident. Similarly, the transcendent God described by the Jewish prophets also stimulated the need for his succour to take a material form in the shape of a Messiah. Moreover, the ‘offensive’ quality of transcendentalists’ traditions may be relevant here. Christianity began in Jesus’ lifetime as a movement of miracle-working competing in a spiritual marketplace and making outlandish claims. Even when Christianity achieved near-monopoly status, as in later phases of European history, it was understood that ardent faith may fall away and need to be restored, or that the true affinities of the Lord would need to be discerned (Ward Citation2011). Christians then, needed signs and wonders as proof of their own deity, of their relationship to him and their ability to interpret him. As I say, these are tentative speculations. They tell us little about Japanese Buddhism, which I leave to one side here, and the question of how this relates to Islam would need much further thought, for it would appear that battle apparitions were far less common in the Muslim world.

Martialism to irenicism

It is helpful to distinguish between two ways of ways of characterizing societies with regard to collective violence. First, would be the simple propensity to go to war, which (rather arbitrarily) we may refer to as bellicosity. Second would be how far the whole life of the community – its norms and narratives, its culture and cosmology – is dominated by the business of waging war. Let us call this martiality. Obviously, the two are likely to be strongly related. Yet equally, it is not difficult to conceive of bellicose societies, especially successful empires, in which the business of war is contracted out to specialist groups while society at large sustains many other values and ways of life. Modern empires have been particularly prone to this – the exportation of violence to the geographic and cultural periphery (Porter Citation2006).

A spectrum of bellicosity or martiality might carry suspect intimations of nineteenth-century comparativism, with its ethnology of ‘warlike’ tribes vs effete peoples. And yet so often the reaction against cultural essentialism leads to a failure to secure analytical purchase on cultural difference. The essays in this volume, and as articulated in the preface, indicate that some such spectrum is broadly possible. The Aztecs, especially, and the Iroquois, reside firmly on the martial end of that spectrum, to which the role of women and the domestic sphere in certain aspects of the business of war is testimony. Buc notes sensibly that religion is only one of several major factors that might shape the degree and quality of martiality. One thinks of Athens and Sparta: sharing overarching forms of Greek culture and religion but yet famously different in terms of the cultural valence of violence.

The chapters collected here indicate at least two factors that will be relevant to a comparative sociology of martiality.Footnote40 Buresi and Lorge’s contributions suggest an important means by which non-violent forms of elite masculinity might arise: the development of urban literate classes – scholars, jurists, artists – who are able to profit from the specialization of violence and the peace created by enduring political orders. This is to evoke Ibn Khaldun and his account of how dynamic tribes (cohered by religious mission – daʿwa) overwhelm settled societies but eventually fall victim to the refinements of civilization themselves. ‘In the eleventh century, the cities of al-Andalus were at the very end of the evolutionary process that Ibn Khaldūn had foreseen: the rise of culture, civilisation and its refinements’ – and thus evince little affinity for military jihad.Footnote41 The specialization of warfare is a double-edged sword for the question of martiality: on the one hand, in order to be effective the warrior class must be endowed with a certain kind of elevated status; on the other hand, their business now represents only one such way of life and sphere of normativity among others.Footnote42

Military specialization tends to involve the erection of status or class hierarchies, and this could also entrench violence at the heart of the social order. This would certainly help explain the case of Spartan society, which was predicated on the need to keep a helot class in check through establishing an atmosphere of permanent bodily threat – thereby producing an image of encompassing military discipline that still excites the fascist tendency today (Murray Citation1980, 153–173). Buc underlines the importance of an aristocratic mode of masculinity found repeatedly across the pre-modern world, founding honour in military glory and de-humanizing the lower orders.

These and other principal causal factors probably operate regardless of whether the cultural setting is immanentist or transcendentalist. It may happen to be the case that a great proportion of societies without specialist divisions of labour and professional military classes have been immanentist. But that is simply because there is, in Eurasian history at least, a general association between the development of states, urbanization, literacy, complex economies, monetization, class and status stratification and the importation of transcendentalist religions (Graeber Citation2011). We can however retain hold of a smaller claim, which is simply to return to an aspect of the irenic strand of transcendentalism, and the way it promoted the emergence of status hierarchies that depended on bookish rather than bellicose attainment (scholars, clerics, jurists) or were even modelled on the rejection of violence (monastics, ascetics, renouncers).

Transcendentalism also produced mechanisms for taming the charismatic authority of successful war-leaders. The following discussion, continued in relation to China below, constitutes an endorsement of Buc’s insight on the changing role of war charisma in the evolution of empires. But first it is necessary to note an important paradox, and one that acts as a further complication to any simplistic connection between transcendentalism and large imperial polities. For there are several reasons why the process of imperial expansion promotes the immanentist mode of sacred rule, which I have referred to as divinized kingship.Footnote43 First, ambitious and successful rulers who have driven such expansionary feats tend also to chafe at any limitations on their agency presented by religious specialists, and will therefore attempt to unite religious and political authority in their own person. Regardless of the cultural framework, this frequently draws upon an assertion of their own proximity to the divine. Second, remarkable feats of military glory do indeed generate reserves of charismatic authority that have frequently found expression in much more emphatic and even transgressive claims of divinization on the part of rulers (Strathern Citation2019, chs 2, 3).

The Almohads constitute an excellent example of both processes. The imām-caliphs led their huge armies into battle themselves and surely reaped the benefit in terms of charismatic glamour. Indeed, Buresi has suggested that they functioned as a living-relic, allowing the transcendent God to produce immanent efficacy.Footnote44 At the same time, they needed to establish a form of religious authority that would trump both the claims of other dynasties brandishing the title of Caliph and the legal authority of recalcitrant ulema. They, therefore, drew upon a range of motifs deployed throughout Islamic history (Al-Azmeh Citation2022; Gommans and Huseini Citation2022) to make themselves ‘sole intercessor with God’, including Neoplatonism, mahdism, and notions of proximity to God (wilāya). They would now become the ‘the sole interpreter of God’s revelation and Tradition’, one dimension of a more general attempt at absolutist control. If the Almohads generated social power through the transcendentalist project of reform, they also did it through the immanentist project of their own quasi-divinization.

As Weber pointed out, charismatic authority is inherently unstable unless it is subordinated to an ideological system capable of routinizing and restraining its operation. What happens when the victories turn into defeats? Or when emperors stop leading troops into battle and other generals win acclaim in the field, when challengers burst on the scene with improbable victories, when delinquent sons succeed conquering fathers … ? As Buc notes, the question of how to manage war charisma is particularly a problem of ‘mature empires’ once the initial bursts of conquest have given way to the imperatives of settled order. Somehow, the gravitas of static emperors must be maintained over the glamour of fleet-footed upstarts, the status of the law placed above the appeal of the transgressive individual, and the esteem of civilian authorities preserved over that of their military counterparts. This is where the capacity of transcendentalist discourses to uphold the status of the righteous ruler over the divinized one, scripture over deed, and the pen over the sword, proved its worth.

China and the case of civil values

There is no space here to put meat on the bones of this proposition with regard to the varieties of transcendentalism touched on thus far, Christianity, Islam and Buddhism. Instead, it will be explored in relation to another of the great Eurasian products of the Axial Age, which has been entirely excluded thus far from the present analysis: Confucianism. One reason why a discussion of Confucianism has been quarantined to the end of this piece is that, more than any other ideological system, it is difficult to characterize in terms of the immanentist – transcendentalist conceptualization. In fact, in a forthcoming publication (Strathern, Citationforthcoming; also Puett Citation2022) it will be shown how the Chinese Axial Age (of which Confucianism was one major product) may indeed be understood in terms of these categories – but the complexities of this discussion cannot be conveyed in any satisfactory way here. Instead, we shall have to jump to the conclusion, which is that Confucianism may be thought of as functionally transcendentalist in certain ways. That is to say, if it lacked the definitive qualities of an ontological breach between transcendent and mundane orders and the salvific imperative, it nevertheless gave rise to an ethicized reading of human nature and political authority, established a literati who appealed to universal moral codes set down in a canon of philosophical texts, and appealed to the rather abstract principle of Heaven. If there is nothing equivalent to the Mosaic distinction (instead Confucianism here typically co-existed with salvific creeds and local cults), here too strong universal ethics went hand-in-hand with a hierarchical differentiation of those within and without the moral community – that is, the civilized vs the barbaric. At the same time, Confucianism as religious practice remained fundamentally immanentist insofar as it retained ritual and indeed sacrificial acts at its heart (Puett Citation2022).

If Confucianism always co-existed with various versions of Buddhism and Daoism, it nevertheless retained an unusual capacity to dictate the terms by which these traditions related to the body politic. All the major transcendentalist traditions produced clerisies who doubled as both religious specialists and the administrative functionaries of state power – monks, churchmen, ulema, brahmins. But, more successfully than any other product of the Axial Age, Confucianism crystallized a form of masculine elite social status for the governing class as a whole – the scholar-gentleman – that was not defined primarily by military values or linked fundamentally to military attainment. The system of governance was rather built upon education and examination, and therefore amounted to an attempt to establish certain meritocratic-bureaucratic norms far earlier than we see in any other part of the world until perhaps the nineteenth century (Woodside Citation2006). It is obviously possible to misuse Weber’s evocation of Confucianism as ‘pacifist’ (Lorge), but relatively speaking, surely one result of all this was that China occupied a position rather closer to the pacific end of the ‘martiality spectrum’ of pre-modern societies in a number of ways. Once again, what look like stale clichés to the specialist become striking truths from a global comparative perspective.

To be sure, the Tang and Song regimes exerted control over some of the most extensive imperial domains in the world and, like all Chinese polities, had to absorb and contend with the predatory ambitions of Inner Asians on their borders. This could not have been achieved without the cultivation of a flourishing militiarism. It is not surprising therefore that in China too we see the need to reward state-sanctioned violence, elevate it in terms of a moral narrative, and express its social role through ritual performance. But, ironically, the sheer size of the Song military (over a million men) also necessitated the development of large civilian bureaucracy. This corresponded to ‘a key discursive binary … the duality wen (文) – wu (武), civil – martial’ (Buc, drawing on Lagerwey) that operated over the long-term. Indeed, there was a constant interplay between the respective positions of civic vs martial affairs, which different rulers resolved in different ways. It is, however, comparatively notable that ‘civil officials saw themselves as superior to military officials and particularly army officers who carried out that violence’. The Tang period had seen significant Confucian opposition to the Martial temple in the 780s, which was downgraded as a result. But once standing armies and a permanent specialist military class were established under the Song, the re-established status of the Martial temple was both an attempt to affirm the importance of martial affairs and to thoroughly subordinate it to the authority of the emperor and the civil order. If imperial titles reflected both spheres of authority, emperors did not fight in the field in person, and nor were the generals who did

distinguished for their personal fighting ability, but rather for their ability to direct armies. None of the martial exemplars were emperors or even kings, making it very clear that to be a martial exemplar was to serve a legitimate ruler.

No wonder that Lorge comments on silence of generals in the historical record, their voice effaced to an unusual degree. This is martiality endorsed insofar as it is decisively tamed. We are a world away from the sacrifice of captives to a god of war.

Conclusion

This remit of this essay has been shaped by the papers collected in this volume, which I have sought to interpret through the lens of a particular conceptualization of religion. It represents what are very much first thoughts on the question of how this theoretical approach might relate to the question of war – rather than a sustained engagement with the huge literature on religion and violence in general. Although the category of transcendentalism collapses the Abrahamic traditions into a broader family of Asian movements, most notably forms of Buddhism and Hinduism, the latter are not represented as chapters in this volume and so have only occasionally been brought into the analysis. It is not argued here that the categories of immanentism and transcendentalism allow us to make predictions about the levels of either bellicosity or martiality exhibited by a particular society. However, to the extent that religious elements do seem to implicated in shaping warfare, immanentist and transcendentalist forms of religiosity differ in how they drive war; allow enemies to be identified; and rationalize or discursively contain collective violence.

The chapters on the Aztecs and the Iroquois suggest one means by which immanentist forms may drive a social group towards enhanced bellicosity or martiality. The immanentist imagination establishes the flourishing of society on its ritualized relations with ancestors, spirits and deities, and – at least remarkably frequently if not invariably – considers sacrifice a primary means of conducting these relations. In a very diverse subset of immanentist societies, this gave rise to the understanding that such metapersons demanded the capture, torture, killing and sacrifice of human beings in order to be honoured or sustained or revenged. Of course, we may imagine that such understandings functioned, in part, as sublimations of the will to power or other aggressive urges on the part of clans, aristocracies, war-bands or empires. Yet there seems no reason to doubt that these beliefs could in turn play some part in both perpetuating conflict and determining how it was carried out. These were not wars in the name of ‘a religion’; they merely arose out of a sphere of social relations that happened to include metapersons. There was a kind of morality involved, but it was one oriented to the tangible this-worldly fortunes of the particular society in question rather than one rooted in a universal ethics. To modern eyes, indubitably shaped by successive waves of both transcendentalism and secularization, there is something remarkably ‘non-euphemized’ or barely disguised about the results. However, it must be underlined rather heavily that the cultures of violence of the Aztecs and Iroquois cannot be taken as generic to immanentist societies per se and that immanentism was an essential means of achieving almost any social-political outcome, including conflict-resolution, peaceful trade, de facto egalitarianism and the establishment of alliance. There was no necessary connection with either sacrificial-victim hunting or warfare more generally.

Transcendentalism contained within it a powerful paradox. It was a means of creating infinitely expandable moral communities, stigmatizing violence, denying the value of its deployment for earthly ends, allowing certain non-violent actors to attain a superior status, and rubbishing the quest for power itself. All such traditions made human sacrifice an anathema, for example. But if they appealed to canonized texts, theological or legalistic discourses, and elaborate traditions of just war theory in order to make sense of contemporary conflicts, this might work to legitimize violence all the more profoundly. Moreover, all transcendentalisms are founded upon a utopian vision which might easily exalt the imperative of salvation over concern for the suffering of flesh and blood in the here and now. This was much more significantly a feature of the monotheistic variants, which established a ‘Mosaic distinction’ between the godly faithful and the ungodly peoples beyond the pale. Thus, wars could be launched in the name of revelations that had emerged long ago and far away, against those within or without who failed to abide by those revelations or appeared to pervert them.