Introduction

While attention has been given to the ways in which nineteenth century anthropologists were motivated by their desire to develop their field as an empirical and rational science (Fowler and Parezo Citation2017; Hinsley Citation1994; Jenkins Citation1994; Stocking Citation1991), less emphasis has been placed on retracing proto-subdisciplinary and experimental methodologies which emerged during the museum period from the 1870s to the 1920s. By examining how ethnologists at the United States National Museum (USNM) in Washington DC developed collaborative practices around the unit which became known as the ‘Anthropology Laboratory’, I consider how their creative approaches imaginatively explored and mediated different aspects to humanity prior to their establishment as sub-fields within anthropology.Footnote1 I also examine how they materialized ethnological knowledge via mannequins, ‘life groups’ and dioramas, as well as through studying technological processes. This included the re-enactment of archaic technologies, during which ethnologists conceived of their own bodies as research instruments. My lens on what I characterize as ‘processes of realization’ – modelling, testing, and exhibiting different materializations of race, technological innovations, and sociality – provides new insights into the extent to which they distinguished between the cognitive, physical, and social aspects of humanity. What emerges is a somewhat different history of a creative media-based discipline through which ethnologists and artists collaboratively realized analytically salient elements of humanity via their manifestation as exhibits.

Museums are often seen as one of the birthplaces of the classificatory and evolutionary-based schemas that created typologies and hierarchies of humanity (physical and cultural), with histories of anthropology retracing how organizing people and objects – and people as objects – have shaped the discipline, both intellectually and ethically (Darnell Citation1969; Hinsley Citation1994; Jenkins Citation1994; Redman Citation2016; Stocking Citation1985). Museums have also been at the centre of the study of the relationship between fieldwork, anthropology, and colonialism, as well as how these were materialized through collections, catalogues, and exhibits (Berringer and Flynn Citation1998; Bennett et al. Citation2017; Coombes Citation1997; Edwards, Gosden, and Phillips Citation2006; Gosden and Knowles Citation2001; Turner Citation2020; Vawda Citation2019). Certain aspects of the creative nature of anthropological practices within museums in the mid to late nineteenth century, however, have been glossed over and viewed only as methods supporting the evolutionary schemas that were later discarded in favour of university-based anthropology.Footnote2 The problems of perceiving this as a straightforward history with defined ideological divisions between museums as the proponents of evolutionary schemas, and Boas’ university milieu as the ones who advocated for cultural relativism, has already been raised in order to consider the contributions of Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) ethnologists, such as Frank Hamilton Cushing and James Mooney (Isaac Citation2005; Jacknis Citation2016). Understanding the creative practices of museum ethnologists within this proto-subdisciplinary landscape and within the context of museums in the latter part of the nineteenth century, however, is still an area needing alternative lenses other than only classificatory ones.Footnote3 Similarly, the use of the term ‘museum method’ in reference to taxonomic schemas, does not take into account the plurality of methods that were and remain intrinsic to museums and anthropology.

Records from the USNM housed at the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) describe a specific unit and approach that by 1908 had become officially known as the ‘Anthropology Laboratory’ (Austin et al. Citation2005). This reveals how the media-based methods they used resulted in a convening hub for testing out experimental material approaches. Analysing the development of this innovative community of practice also provides insight into how present-day boundaries in expertise between the fine arts, natural sciences, anthropology, and museology were not yet fully formed.

Asking how and when anthropology becomes a discipline with the often cited four field approach or sub-disciplines results in as many multiple entry points and origin stories as questions asked of its history(ies). As Fowler and Parezo suggest, even today ‘there is no one definition of anthropology’, with disciplines, more generally, being understood as ‘ever changing and continuously debated constellations of intellectual heritage’ (Fowler and Parezo Citation2017, 388). To understand the heterogenous origins of anthropology in the mid nineteenth century, scholars have traced when scientific societies in Europe and America became dedicated to formalizing the concepts of ethnology, ethnography, and latterly, anthropology (Fowler and Parezo Citation2017; Kuklick Citation2008; Roldan and Vermeulen Citation1995; Sera-Shriar 2013; Stocking Citation1991). This includes the role of museums in object-centred studies (Bronner Citation1989; Jenkins Citation1994), and methodologies around embodied knowledge (Isaac Citation2010), as well as how these shaped broader forms of experiential knowledge and the museum as a space for teaching anthropology (Gosden and Larson Citation2007). The role of the anthropological museum in the US and the ‘museum method’ in wider social contexts include establishing a corelation between power, knowledge, and classification practices (Bennett et al. Citation2017; Coombes Citation1997; Turner Citation2020). Attention has also been given to when anthropology was established within university departments and its further professionalization through degree programs and sub-disciplines (Darnell Citation2021). The period in the US during which museums and world fairs were part of shaping the discipline has also been explored (Hinsley and Wilcox Citation2016; Jacknis Citation2016; Parezo and Fowler Citation2007), as well as how exhibits mediated cultural difference and shaped representational genres of race and culture in the twentieth century (Griffiths Citation2002; Jacknis Citation1985).

There has also been a growing interest in the history and role of mannequins, life groups, and dioramas in the development of anthropology as a museum-based profession in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Arnoldi Citation1999; DeGroff Citation2012; Étienne Citation2017; Citation2020; Fitzhugh Citation1997; Glass Citation2009; Citation2010; Griffiths Citation2002; Isaac Citation2010; Citation2011; Citation2013; Citation2021, Citationforthcoming; Jacknis Citation1985; Citation2015; Citation2016; Qureshi Citation2011; Sandberg Citation2003; Varutti Citation2017; Wakeham Citation2008; Westerkamp Citation2015; Zittlau Citation2011). Their extensive use within international expositions to exhibit culturally distinct ethnic groups and colonial subjects has been well documented (Rydell Citation1985) and interpreted as cultural representations critical to the visual genres of the time (Jacknis Citation1985, Citation2016). Anthropologically informed life-groups have also been studied to illustrate how spectatorship was being shaped in the late 19th and early twentieth century (Griffiths Citation2002), as well as exposing the tensions between visualizing tradition and modernity (Sandberg Citation2003). Tribal museums’ contemporary use of mannequins and dioramas has been explored regarding how they present cultural concepts of technology, reality, and artifice in museum displays (Kalshoven Citation1993), as well as address issues around the control of Indigenous bodies (Isaac Citationforthcoming).

Mannequins and dioramas using life groups have also been viewed as archaic museum props that embody the problematic vestiges of racist theories of 19th and twentieth century anthropology, resulting in them being disposed of or relegated to museum basements (Isaac Citationforthcoming; Westerkamp Citation2015; Zittlau Citation2011). Their ability to remind of us of the untidy, problematic, and discarded veins of anthropological practice, however, should prompt us to reconsider more fully the numerous and intersecting aspects underlying their creation that continue to provoke these tensions today (Isaac Citationforthcoming). As a result, consideration of museum anthropologists’ engagement with nationalist and colonialist concepts of race is also crucial to this history, especially regarding their embodiment of power relationships that shaped how anthropology materialized within the museum through the process of developing exhibits.

By looking at the experimental practices involved in the recreation of the human body in dioramas which merged the social and physical aspects of humanity – I follow a route through the developmental years that facilitate the contemplation of proto-subdisciplinary methodologies without a priori assumptions about anthropology’s shift from museums to the academy, or from evolutionary schemas to regional cultural histories. There is already recognized scholarship on the tensions in the late-nineteenth century that arose between the USNM’s Otis Tufton Mason’s comparative taxonomic classifications based on invention, and the relative individual histories advocated by Boas (Hinsley Citation1994; Jacknis Citation2016). I am interested, however, in the areas of practice these debates have overshadowed – especially those pointed out by Jenkins (Citation1994) as the non-lexical or non-discursive ones. As suggested by Jenkins, ‘rather than reducing anthropological practice to language’ especially in the case of the history of anthropology in the context of museums, ‘it seems more prudent, complex, and interesting to explore the historically contingent relationships between the discursive and the nondiscursive’ (Jenkins Citation1994, 270).

I begin with the origins of museum-based mannequins and life groups to show how these are linked to the materialization of what was considered anthropological knowledge of the time. I examine their production at the USNM for world fairs and how this contributed to the creation of the Anthropology Lab. I also explore links between nineteenth century experimentation around embodied knowledge and the development of life groups. are included to show the developmental trajectory of Smithsonian ethnology exhibits and how they began with typological displays of material culture and the display of face casts of Native Americans, followed by the development of individual mannequins to show physical types dressed in cultural attire, succeeded by mannequins demonstrating specific types of technology, and finally, life groups which combined technological processes, environmental knowledge, and sociality. depict the creative spaces and performative processes though which these kinds of exhibits were conceived of and constructed. Lastly, I discuss current lenses on the politics of colonialism and the objectifying of race through museum exhibits. This contemporary lens also elicits recognition of new collaborative and experimental approaches in museums that are created with and by Indigenous communities, and how this is a leading factor in shaping museum anthropology in the twenty-first century.

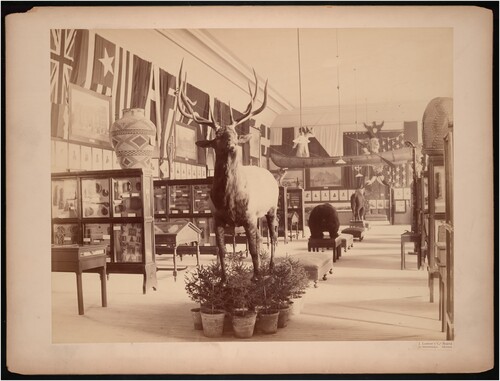

Figure 1. Archaeology and ethnology exhibits in the Upper Main Hall of the Smithsonian Institution building, now known as the ‘Castle’. Photograph likely taken between 1877 and the early 1880s as the anthropology exhibits were moved to the National Museum building in 1881. Classical busts are displayed on exhibit cases, and a series of head casts of the Fort Marion captives (made in 1877) displayed on top of the cases at the back of the Hall. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 11-006, Box 006, Image No. MAH-2962

Figure 2. USNM ethnology displays at the Columbia Historical Exposition in Madrid, Spain (1892–1893). Image shows five individual mannequins, including the central one of Rosa White Thunder created by U. S. J. Dunbar. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 64, Folder 02, Image No. SIA_000095_B64_F02_003

Figure 3. USNM ethnology displays at the Columbia Historical Exposition in Madrid, Spain (1892–1893). Photograph shows canoe of birch bark ‘manned’ by two mannequins of ‘Algonquin Indians’ (Report of the Colombian Historical Exposition at Madrid 1892: 183). Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 64, Folder 02, Image No. SIA_000095_B64_F02_001

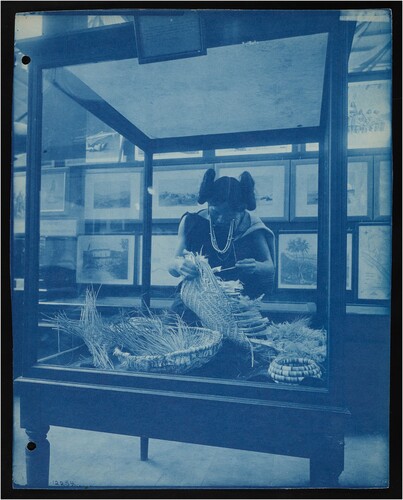

Figure 4. Mannequin of Hopi basket maker that was presented as part of the Dept. of Ethnology and Bureau of American Ethnology exhibits in the United States Government Building at the World’s Colombian Exposition (Chicago World’s Fair), 1893. Display designed to demonstrate technological processes in action, with the baskets in a series showing each stage of manufacture. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 61, Folder 11A, Image No. SIA_000095_B61_F11A_014

Figure 5. Life group of Navajo silversmiths created by the Dept. of Ethnology and Bureau of American Ethnology for the World’s Colombian Exposition, 1893. Like the basket maker mannequin, the silversmithing process is revealed in distinct stages as demonstrated by each individual mannequin. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image M NH-12279.

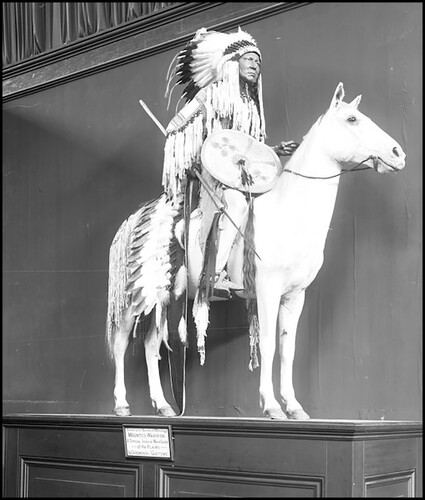

Figure 6. Northwest Coast family group exhibited by the Department of Anthropology in the United States Government Building at the Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, NY, 1901. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 62A, Folder 12, Image No. SIA_000095_B62A_F12_002

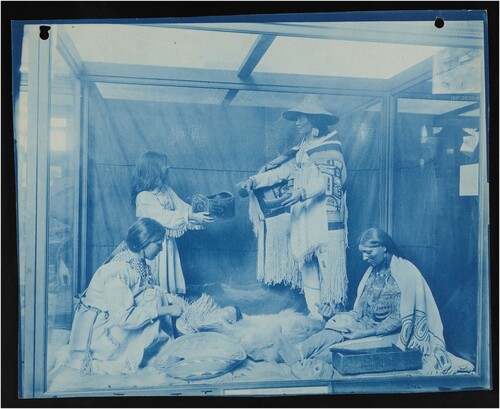

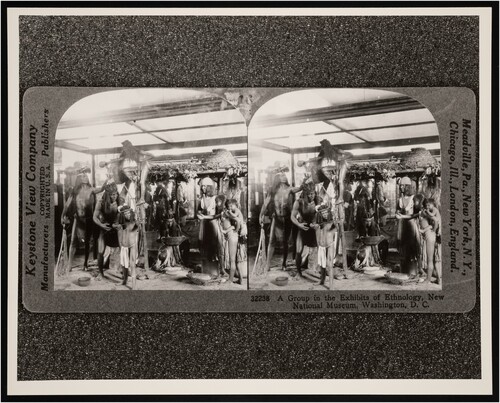

Figure 7. Stereograph (front) of family group of Cocopah Indians, ethnology exhibits in the ‘New National Museum’ now known as the National Museum of Natural History. Image most likely dates to around 1910, which was the date of the opening of the United Stated National Museum (USNM) building. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 44, Folder 01, Image No. SIA_000095_B44_F01_022

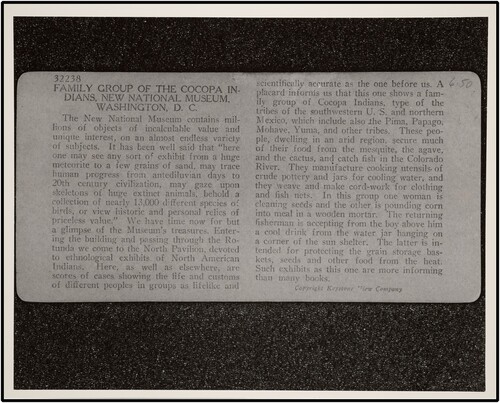

Figure 8. Stereograph (back) with text describing the ‘New National Museum’ and ethnology exhibits, as well details about the activities of each mannequin in the life group of Cocopah Indians. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 44, Folder 01, Image No. SIA_000095_B44_F01_023

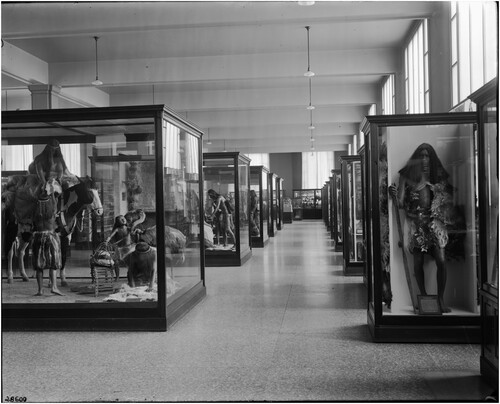

Figure 9. Exhibit cases showing both family groups and the individual mannequins in the Anthropology Hall of the United States National Museum, 1911. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 44, Folder: 2, SIA-NHB-28600.

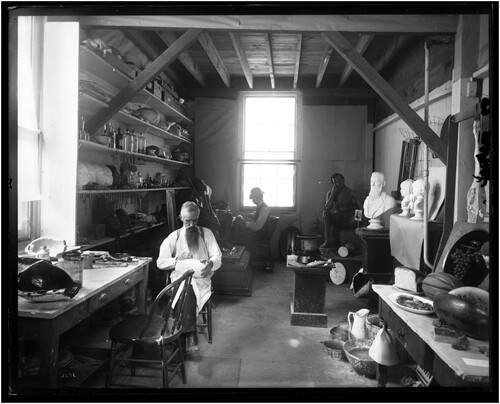

Figure 10. Sculptor, John W. Hendley, working on exhibit preparation at the National Museum in the 1880s. Image is undated, but Hendley’s recorded dates are between 1885–1886 (SI Preparators’ Reports, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 408, USNM). Photograph from the Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 11-006, Box 009, Image No. MAH-3678.

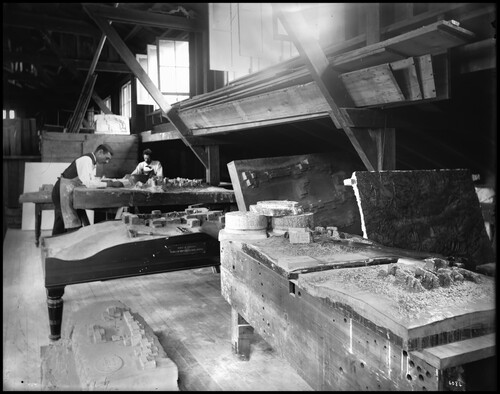

Figure 11. Models being prepared by Victor and Cosmos Mindeleff (1885) based on their architectural studies of the Southwest Pueblos. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 28, Folder: 31SIA-MNH-3674.

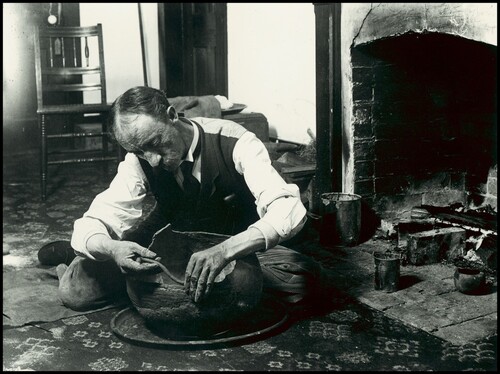

Figure 12. BAE ethnologist, Frank Hamilton Cushing, demonstrating the coil technique in pottery making. National Anthropological Archives. Smithsonian Institution (Port 22a).

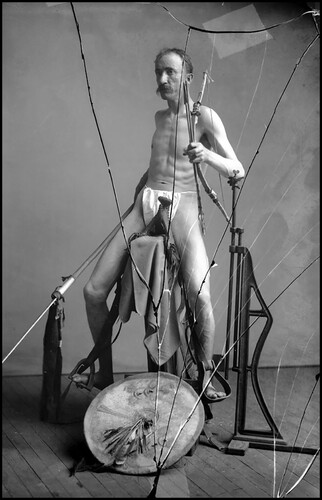

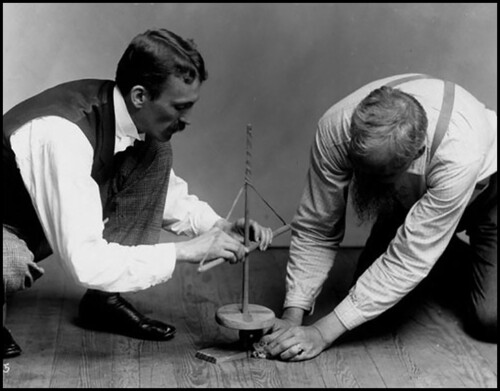

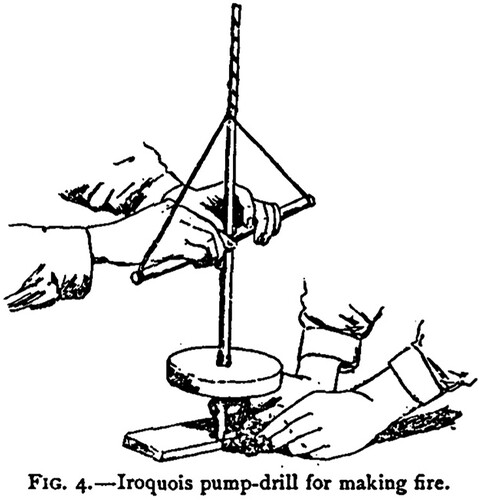

Figure 13. Archaeologist and ethnologist for the Department of Anthropology, Walter Hough, demonstrating the fire pump drill, National Museum, Smithsonian Institution. Photograph most likely taken around 1890 in preparation for Hough’s publication on fire-making tools, American Anthropologist (1890). National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (MNH_5614a).

Figure 14. Illustration based on the re-enactment photograph of the fire pump drill in , used by Walter Hough in his publication on fire-making tools, American Anthropologist (1890).

Mannequins and life groups at world fairs and exhibitions

The origins of anthropologically informed exhibit mannequins and life groups can, in part, be traced back to the human shows of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that exhibited living people from foreign and colonized lands (Qureshi Citation2011). By the mid nineteenth century, this type of entertainment had developed into large-scale economic ventures in urban centres like London, Paris, and Hamburg, resulting in the commercialized spectacle of foreign peoples (Altick Citation1978; Ames Citation2009; Qureshi Citation2011). The practice further expanded with the advent of world fairs, many of which transported and reproduced entire villages to be exhibited for public entertainment and study, with these later being referred to as ‘human zoos’ (Blanchard Citation2012).

The use of waxwork mannequins to represent ethnic groups can be traced back to their use in commercial ventures in London, such as the Chinese Collection in 1842 and the Oriental Turkish Museum in 1854 (Jacknis Citation1985). The first use of mannequins for proto-anthropological displays also occurred in London in 1854 at Crystal Palace, once the exposition had moved from Hyde Park to Sydenham. The English philologist and nascent ethnologist, Robert Gordon Latham, worked alongside Edward Forbes, a professor of botany at Kings College. Together they established the Natural History Department of Crystal Palace and constructed displays of mannequins representing people from around the world alongside the flora and fauna of each region (Qureshi Citation2011). These were arranged according to Old and New World categories, including a series of ethnic groups from Tibet and Java, North America, and Africa. Latham employed a taxonomic approach in which humans, like plants and animals, were regarded as distinct ‘physical types’ and organized according to natural history and geographic categories (Qureshi Citation2011). Interestingly, this approach lived on far beyond the exhibits, especially since the guidebook accompanying them became recognized as one of the most widely read publications of its time, and one that helped to establish the emerging field of anthropology (Qureshi Citation2011).

A subsequent fair that further experimented with mannequins was the International Exhibition in Paris in 1867, during which the Swedish artist, Carl August Soderman, created life-like wax mannequins of the Saami people of Norway and Finland. Soderman’s exhibits consisted of small life groups made up of mannequins in traditional dress conducting everyday activities. While less emphasis was given to the environmental context, more attention was given to developing new techniques to provide life-like human appearances. Mannequins latterly became popular devices in Scandinavian folk museums for re-enacting historic events, as well as for depicting the diversity of Scandinavian cultural traditions (Sandberg Citation2003). Artur Hazelius, the Swedish ethnographer and museum pioneer who was concerned over the loss of Scandinavian traditional ways of life to the industrializing of Europe, later hired Soderman to produce a series of life-like mannequins to be displayed in his ethnographic museum, as well as at international expositions in Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1878) and Chicago (1893) (DeGroff Citation2012; Sandberg Citation2003).Footnote4

In the United States, the Smithsonian Institution started to experiment with exhibition mannequins by introducing them to their displays at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition (Jacknis Citation2016). The assistant secretary to the Smithsonian, George Brown Goode, recorded that the initial idea had come from museum staff who had visited Europe and had been influenced by the ‘historic figures in Castas’s ‘Panopticum’ in Berlin … Madame Tussaud in London … [and] the representation of races of mankind at Sydenham’ (Goode Citation1895, 52). While there is a paucity of visual documentation of these first attempts by the Smithsonian, their construction methods were documented in texts as being somewhat crude, thereby resulting in efforts for their improvement. By 1878, USNM staff had recreated a series of mannequins for display that represented the Artic explorer, Elisha Kent Kane, alongside an Inuit couple, (Fitzhugh Citation1997; Goode Citation1895; Jacknis Citation2016). The need to further experiment and improve production techniques for the mannequins is clear in the except from the 1893 Annual Report for the National Museum written by the Assistant Secretary, who stated that ‘It is scarcely worthwhile to mention the ghastly wax figures of Kane, the arctic explorer, and his companions, in costumes of fur, which were displayed in the old Smithsonian Museum as early as 1870. These, and the equally crude manikins of Eskimo Joe and his wife Hannah, made in 1873, have long since been discarded and have no place in the history of recent efforts’ (Report of the National Museum 1893, 52).

Smithsonian ethnologists’ use of mannequins and life groups was also in response to negative reviews of their earlier exhibits – now well-known via the debate between Otis Mason, who was interested in comparative and natural history methods that followed evolutionary typologies, and Franz Boas, who argued for a regional and historical approach (Jacknis Citation2016; Stocking Citation1991) depicts these early anthropological displays of the 1870s at the Smithsonian in what is now known as the ‘Castle’ and show the emphasis on the typological arrangements of objects in cases rather than dioramas []. From the late 1870s onwards, USNM department heads sought for and received funding to produce exhibits for a series of world fairs, with many of these increasingly using mannequins and eventually life groups as the principal mode for displaying what the ethnologists envisioned as the key facets to the emerging discipline. These included physical types, cultural and geographically arranged groups, as well as the sociality of humans.

Throughout these experimental years, Smithsonian ethnologists tried out increasingly more animated means of communicating what they saw as the link between human behaviour, environment and the developing of culture via human technological advancements. This resulted in life groups demonstrating technical processes – such as weaving, pottery, bread making and silversmithing. Interestingly, while Mason adapted to external critiques of the initial displays and was the first to exhibit human inventions according to what he saw as the ‘geo-cultural’ methods, Boas eventually became more prominent in the history of anthropology for his critiques of the typological evolutionary schemas. Mason and his Smithsonian colleagues’ contributions to the development of life groups and early experiments in realizing anthropological concepts beyond classificatory schemas, however, have largely been overlooked. Furthermore, Boas is sometimes incorrectly attributed as the person who introduced anthropological dioramas to the US.Footnote5

While this history reveals the ways in which anthropology was being shaped through the production of public exhibits, we also need to look behind the scenes at the USNM at how these mannequins and life groups were created as experimental bodies of knowledge, around which curators conjoined artistic practices with new ideas about psychology and the cognitive history of humanity. Mannequins, in this regard, were not merely pedagogical instruments for curators for the communication of cultural difference, but also mobile components useful in their hypothesizing about and externalization of the analytically salient components of humanity – which latterly became the subdisciplines of ethnology, archaeology, linguistics, cognitive and physical anthropology.

Realizing sociality or racial types or both?

Staff from the USNM Department of Ethnology and the Bureau of Ethnology (which later became the Bureau of American Ethnology or BAE) worked together with artists, exhibit preparators, photographers, and a wide range of technicians and preparators to produce exhibit materials for a remarkable ten world fairs, including the Philadelphia Centennial (1876), the Columbian Historical Exposition in Madrid (1892), World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893), Cotton States and International Exposition (1895), Trans-Mississippi Exposition (1898), Pan-American Exposition (1901), Jamestown Exposition (1907), Alaskan-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (1909), Panama-California Exposition and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (1915). Monies to produce exhibits for the fairs were sometimes allotted by the US Congress to the USNM, resulting in this exhibit-based funded work playing a vital role not only in shaping how the emerging discipline of anthropology was communicated to the public, but how it was practiced and conceived of in the museum.

Initial experiments with mannequins commenced with individual figures for the display of ‘costumes’ and ‘to show the characteristics of the different races, and … illustrate the methods of the use of weapons and instruments and the processes of various arts and handicrafts’ (Ewers Citation1959, 519). These are most evident in the exhibits the USNM created for the Columbian Historical Exposition in Madrid of 1892 []. Individual mannequins standing erect and not in active poses were exhibited ‘outside the cases’ and included a Kiowa woman and warrior modelled by Theodore Mills with clothing collected by James Mooney; a Sioux woman and Sioux warrior; a Zuni male figure with the head ‘modelled from life by Clark Mills’ and clothing collected by James Stevenson, as well as an ‘Eskimo man’ (Goode Citation1895, 183). These exhibits did, however, include one active grouping which consisted of a canoe of birch bark ‘manned’ by two mannequins of ‘Algonquin Indians’ suspended from the ceiling (Goode Citation1895, 184) [].

Artists working with the ethnologists experimented with life casting methods to replicate physical and racial characteristics. The artists listed as modellers for mannequins displayed at the Madrid Exposition included Theodore A. Mills, U. S. G. Dunbar, and Clark Mills (Goode Citation1895, 183). The Smithsonian Institution’s interests in collecting face casts of Native Americans had an earlier origin, with the assistant secretary, Spencer Fullerton Baird, commissioning plaster face moulds and casts to be made by Clark Mills in 1877 of Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Caddo, and Comanche captives at Fort Marion, Florida. Baird subsequently argued these types of casts should be ‘standard objects in the principal ethnological collections of the world’ (Baird cited in Pratt Citation1878, 201). Baird’s interests also followed a prevalent belief of the time that Native Americans would either be assimilated or destroyed by the onslaught of Euro-American ‘civilization’, and that museums and ethnology could play a critical role in preserving them as collections – both in terms of accumulating their material cultural, as well as physical duplicates of them as racial typologies for display in the museum (Isaac and Colebank Citation2023).Footnote6

During experiments by USNM ethnologists and artists with face casts for mannequins, however, they discovered that while these could duplicate the correct dimensions of a person’s facial features, life casting methods resulted in expressionless and mask-like faces:

Life masks, as ordinarily taken, convey no clear notion of the people. The faces are distorted and expressionless, the eyes are closed, and the lips compressed. Like the ordinary studio portrait of primitive sitters, the mask serves chiefly to misrepresent the native countenance and disposition; besides the individual face is not necessarily a good type for the group. (Holmes Citation1903, 201)

Experiments are still in progress, and it is believed that figures still more truthful and life-like than any that have yet been produced will be the result. The most serious difficulty to overcome is in the treatment of the surface of the figure and their coloring … Plaster of Paris has only one objection, which is the roughness of the surface. It is now believed that the smoothness and texture of the flesh can be produced by the use of some of the mineral waxes. (Goode Citation1895, 55)

Both during and after the introduction of these activity-based life groups, however, some of the USNM ethnologists continued to produce static individual mannequins to show physical types adorned in cultural attire. For example, Mason and his ethnology assistant, Walter Hough, produced a series of individual mannequins for the Cotton States Exposition in 1895 depicting what they imagined as the ‘four divisions of mankind’ organized by skin colour rather than geography. These consisted of: ‘Black Types’ (Papuan, Australian and Zulu examples modelled from photographs); ‘Brown-Red Types’ (including a Jivaro American Indian modelled from a painting, Dyak and Maori examples modelled from photographs); ‘Yellow Types’ (with an ‘Eskimo’ modelled from photographs and life masks, Tibetan, and Siamese examples modelled from photographs); and ‘White Types’, (including an ‘Arab Sheik’ which was a replica of a figure from the Trocadero Museum, an Armenian modelled from life, and a Berber modelled from a photograph) (Goode Citation1896, 615–617). Interestingly, at the same time, Mason also helped to produce a series of life groups, such as ‘Navajo women weaving blankets’, and ‘a Crow warrior painting his blanket’ (Goode Citation1896, 634–635). While the static individual mannequins emphasized the physical attributes of their subjects, and the life and family groups demonstrated their sociality. The fact that these two different approaches were produced by the same department and by overlapping cohorts of ethnologists reveals that subdisciplinary lines and professional methodologies between physical anthropology and ethnology were still not yet defined in the 1890s.

In regard to these different approaches, Holmes, who had become head curator of anthropology in 1897, argued that family groups were the more compelling method for providing a unified approach to racial types and social groups. He stated that ‘the most important unit available for illustrating a people is the family group – the men, women, and children, with their costumes, personal adornments, and general belongings’ (Holmes Citation1903, 200). The evolution of the life groups as family groups is most evident in the dioramas created for the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY in 1901 []. Holmes also argued that reproducing cultural ‘types’ was preferable to physical ones: ‘Especial effort was made to give a correct impression of the group as a whole, rather than to present portraits of individuals, which can be better presented in other ways’ (Holmes Citation1903, 201). The apex of these types of family groups are evident in the stereographs produced for the public when the USNM opened its galleries in 1910 as the new Natural History Building. The stereographic photographs of the Cocopah family depict this melding in the diorama of technological processes (basket weaving and pottery production) subsistence in a desert environment (gathering mesquite, agave and cactus), and the sociality of the family group, including the gifting of food []. The text on the back of the stereograph also reveals how these aspects to Cocopah ways of life were the ones seen to be important to realize in the diorama and through anthropological studies [].

Whereas Holmes emphasized family groups to provide compelling narratives about human sociality, Hough continued to see racial categories as a primary organizing factor. For example, when in 1920 Holmes left the USNM, Hough chose to refocus more intently on his interests in using physical types as the principle for arranging the exhibits. In 1922, in an annual report on the life groups and their role in the anthropology exhibits, although Hough credits Holmes with the development of the family groups, he stated his main organizational criteria was ‘racial types’. While he no longer classified mannequins according to skin colour as he had for the Cotton States Exposition, he used the term ‘racial groups and figures’ to summarize the expanded exhibits under his supervision. He explained how these were ‘selected to represent the salient features of the people, their arts and industries, their costumes, and their physical characteristics; and such features of their environment as can be utilized within the available space’ (Hough Citation1920, 613). Even by the early part of the twentieth century, therefore, the USNM both isolated racial typologies via individual mannequins and organized them as racialized socio-cultural groups. shows the USNM gallery with family groups on the left and the individual mannequin style on the right, showing that in the early 1920s, the museum had not yet divided their galleries or displays between physical and cultural anthropology [].

It is worth noting that Ales Hrdlička, who was trained in medicine and anthropometry and hired by the USNM Dept of Anthropology in 1903, was later recognized as one of the founders of physical anthropology in the United States. In 1915, Hrdlička exhibited what he envisioned as the science of physical anthropology at the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego through a series of busts that emphasized detached physical facial features and racialized types from their social bodies. In preparing the exhibition, Hrdlička’commissioned individuals to do fieldwork around the world and photograph front and profile poses of people, as well as make face casts. Accompanying the photographs now held in the NAA (Photo Lot 9, USNM ACC 61302) are notes that include the designated tribe, age, sex, name(s), photographer, and number of the corresponding bust. The contrasts between Hough’s racial types in the USNM galleries and Hrdlička’s typologies of racial busts for the Panama Exposition are not well documented. What these two simultaneously occurring yet different exhibit approaches suggest, however, is that between the 1900s and 1930s and while the concept of physical anthropology was emerging – including via Hrdlička’s methodologies and displays – the museum had not yet unanimously conceived of how to communicate it as a distinct subdiscipline within their galleries.

The emergence of the USNM anthropology laboratory

Between the 1870s and 1900s, collaborative work towards the development of exhibits at the USNM had taken place within workshops referred to as ‘preparatory laboratories’ at the Smithsonian (Rathburn Citation1906). Work by artists, such as John W. Hendley, included duplicating a range of objects for display, as well as plaster face casts for ethnological purposes []. Architects Victor and Cosmos Mindeleff, who worked for the BAE, are also shown in photographs creating miniature models based on their surveys of the Southwestern Pueblos []. This creative media-based work epitomizes the breadth of expertise found in these collaborative spaces. Annual reports also reveal the USNM’s desire to set the standards for others in methodology around exhibit development and material science (1893, 52). The creation of life groups was considered part of this pioneering work, with staff expected to explore experimental media and techniques as ways to elevate the manufacture of life-like mannequins and props for exhibits.Footnote7

These creative media-based laboratory spaces within the museum also supported experimentation with new conservation techniques, such as the processing of collections with pesticides, as well as the repair of objects (pottery, wood, baskets, etc.). In reporting these activities in 1906, the then administrator, Robert Rathburn, wrote:

In the preparatory laboratories of the Department of Anthropology there was no cessation of activity at any time during the year. It is there that all the casting, modeling, and coloring of specimens are done, that the lay figures [mannequins] are prepared for the exhibition cases, and that the poisoning and cleaning of objects are conducted. (Rathburn Citation1906, 29)

Within this media-based laboratory, curators and preparators were actively involved not only in the development of exhibits, but in the physical care of collections, as ‘evidenced by their reports and records, which specifically indicated their contributions to treatment, cataloguing, mounting, and pest management activities’ (Austin et al. Citation2005, 189). Their involvement across the exhibit, conservation and research activities is of significance, as they are indicative of a period before this labor and expertise was hived off and assigned to professionalized fields and the roles of conservator, collections manager, etc. It also alerts us to the extent to which these ethnologists and archaeologists were gaining experiential knowledge from this hands-on work with material culture and collections. Like the emergence of distinct sub-disciplines within anthropology, the creation of the Anthropology Laboratory indicates a phase in which the convening of media-based work with curators, artists and preparators alike, was developing into specializations that, although they initially contributed to the realization of anthropological concepts, eventually led to the professionalization of material and conservation sciences in museums.

‘A laboratory habit of mind' and the re-enactment of embodied knowledge

During the 1870s, and as anthropology was emerging as a discipline in the United States, scientific philosophers such as Charles Sanders Pierce and William James were exploring concepts of human agency and the development of experience-based consciousness over time. Herbert Spencer’s writings on Darwin’s theory of evolution introduced to the scientific community the possibility that not only the body, but also the mind was the result of natural processes. Through methodology based on usefulness and experience (Pierce) and introspection and ‘pure experience’ (James), the movement of pragmatism was born, and is considered the first Western philosophical movement original to the United States (Reck Citation1967). As the initial founder of this school of thought, Pierce ‘proposed the adoption of the empirical, experimental attitude – what he called the ‘laboratory habit of mind’’ (Reck Citation1967, 48). James, who is also considered the founding father of psychology in America, suggested in 1875 to the President of Harvard that he develop a graduate course to explore ‘in a truly anthropological way’ a union of both ‘the biological and introspective approaches’ (DeArmey Citation1986, 23).

The link between ideational and manufactural practices in the creative process of realizing anthropology via exhibits at the USNM is best understood through these theories. This is especially the case with how the ethnologists employed their own bodies as instruments in the study of the developmental history of the human mind (Isaac Citation2010). Frank Hamilton Cushing, the young BAE ethnologist who was later recognized as the first to practice participant observation techniques in the field, became one of the leading proponents for adopting experimental approaches to exploring historic cognitive developments through learning manual crafts. For Cushing, this was a mechanism for understanding the mental aptitudes of ancient societies. Latterly, he became ‘well known among ethnologists’ for these experimental approaches (McGee Citation1900, 363). He was also one the first to re-enact for a public audience archaic flint-knapping methods used by Native Americans (Isaac Citation2010). By the 1890s, he had developed a body of theory that connected the making of things and the mind-sets involved with evolutionary trajectories of technology and culture. In his article on ‘manual concepts’, he stated that:

The hand of man has been so intimately associated with the mind of man that it has moulded [sic.] intangible thoughts no less than the tangible products of his brain … For the hands have alike engendered and attended at the birth of not only all primitive arts, but also many primitive institutions, and it is not too much to say that the arts and institutions of all early ages are therefore memorized by them. (Cushing Citation1892, 308)

Similar practices were being explored in Britain, with the re-enactment of non-European and archaic technology playing a role in the training of the first students in anthropology. According to this line of thinking, objects were imagined to materialize past and present cultural knowledge and, in learning how to make these, students could internalize and better understand ‘a form of intellect generated through physical actions and interactions’ partaking in ‘a scheme aimed at training the body as well as the mind’ (Gosden and Larson Citation2007, 124). As Gosden and Larson outline in their study of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Lieutenant-General Pitt Rivers believed that anthropology students should obtain ‘a practical knowledge of the manufacture of flint implements, flaking, secondary chipping’ and ‘boring holes’ (Gosden and Larson Citation2007, 124). Additionally, Edward Burnett Tylor, the first professor of anthropology at Oxford, also followed this methodology, such that he argued ‘the best way to understand a primitive craft was to practice it’ (Gosden and Larson Citation2007, 127).

Correspondence between Henry Balfour, the curator for the Pitt Rivers Museum, and Walter Hough at the USNM, reveal a relationship formed around the methodology of replicating fire-making tools. Like Cushing, Balfour ‘made himself proficient in the art of chipping and flaking flint’ as a method towards appreciating ‘the techniques employed by ancient and modern peoples’.Footnote9 At the start of their communication with each other, Balfour was open with Hough about the difficulties he was facing in mastering this technology: ‘I have succeeded in churning out dense volumes of smoke with the model, though have not obtained the actual spark’ (April 28; Citation1890). Apparently, Hough helped Balfour in solving these challenges, and in a subsequent letter, Balfour wrote: ‘Many thanks … for the pieces of wood which I now put in, I am glad to say that I have been able to drill fire with these several times, without difficulty’ (September 25; Citation1890). Balfour attempted to learn first-hand a range of fire-making technologies: ‘I have had some success with fire sawing with two pieces of bamboo, and have obtained fire by the Bornean method … and the more ordinary mode as practiced in Celebes and the Nicobar group. I should greatly like to try Forbes method (New Guinea) with a strip of rattan & stick, it is something very special’ (Balfour to Hough: December 13; Citation1890).

Photographs housed in the NAA provide further insight into how re-enactment techniques became part of creative media-based approaches to the experimental modelling of cultural knowledge []. The photographic medium served numerous purposes, including the documentation of the process of re-enactment that was used for illustrating publications, as well as for the development of exhibits. depict the performative nature of these experiments and how the ethnologists were investigating creative methods to record and disseminate the intangible aspects of fieldwork and anthropology, as well as the evolution of the human mind, translating these into the tangible facets of the discipline through publications as seen in , and exhibits as seen in and [].

The extent to which re-enactments were tied to the process of realization and dissemination of anthropological knowledge is best understood through these performances and creative spaces in which mannequins and life groups were manufactured. Here, the ethnologists themselves become bodies of experimental practice, as well as the embodiments of fieldwork knowledge.

USNM ethnologists also used these experiments as part of the comparative study of technology – both contemporary and historic. Ewers notes these studies involved ‘intense efforts to describe and classify American Indian artifacts on the basis of their manufacture, form and function’ (Ewers Citation1959, 518). These were not merely descriptive studies based on morphology, they were also interested in understanding the physical and cognitive processes that were a part of the manufacturing of these objects:

During the 1880s anthropologists in the museum experimented with primitive tools to determine how Indians [sic.] worked stone, bone, shell and copper. They analyzed the techniques Indians employed in dressing skin, weaving baskets, and making pottery, as well as harpoons, throwing sticks, knives, pipes, cradles, fire-making apparatus, and other artifacts in the collection. (Ewers Citation1959, 518)

According to Ewers, ‘this technological approach, which absorbed the interests of the ethnologists in the museum laboratories was adopted by them in planning and arranging the American Indian exhibits for the public’ (Hinsley and Holm Citation1976, 518). Within the evolutionary paradigms, an ‘industrial art’ or technology such as weaving was viewed as indicative of a culture's position in the evolution of human development. This also resulted in the ethnologists closely documenting the steps that made up each technological practice – much like the concept that later became known in archaeology as the theory of chaîne opératoire, which looks at the processes and acts in a step-by-step creation, use and disposal of material culture (Audouze Citation2002). There are photographic records from BAE ethnologists Matilda Coxe Stevenson and James Mooney that speak to this practice as an area of interest to them (Isaac Citation2005; Jacknis Citation1990). Stevenson, who conducted fieldwork in the Southwest, was a pioneer in using the camera to record filmic sequences which detailed each stage and process involved in preparing wool for weaving, playing games, collecting water, and manufacturing adobe bricks (Isaac Citation2005). Thus far, however, there is no evidence that her photographs were used for developing life groups. The decision to use photography to document technical processes for developing life groups, however, was discussed explicitly by Mooney, who wrote about this after he was commissioned to collect materials for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In describing this work at Hopi, Mooney wrote:

I spent several days … watching the women at work grinding flour and making bread, noting all the arrangements for milling and baking, learning the different kinds of corn and flour, and finding out for myself how they tasted. The women were very good-natured in explaining everything … We arranged with two of the women to come down to the trading post and set up a flour mill and furnace like those in the houses and grind corn and make breads so that I could photograph them at work and afterward buy the outfit and send it on to Washington … After the photographs were made the mill and the furnace were taken to pieces and boxed up, together with complete costumes sufficient to dress figures to show all the different steps of the process, and specimens of corn, flour, bread, … sent on to Washington where a group of bread-makers has been prepared (Mooney cited by Jacknis Citation2016, 308–309).

Bodies as objects of knowledge and the objectification of race

A curious aspect to the work done in the Lab was the amalgamation of the ethnologists’ bodies with the racialized subjects of the anthropological face castings. Following the use of ethnologists as physical models to demonstrate their field-based knowledge, artists joined the fabricated bodies based on these poses with the replicated faces of the Indigenous people that had been cast and re-sculpted. The results were mannequins that were hybrid creations in which the ethnographer and the ethnographic subject became one.

The conceptual and physical mutability that the ethnologists awarded their own bodies by employing them to realize these mannequins speaks to a form of hubris in their attitudes about their role as ‘models’ for the racialized bodies of ‘others’. While they had the privilege to ‘try-on’ garments and ‘adopt’ what they believed were the poses of their Indigenous subjects, these were temporal states that could easily be discarded, allowing them the freedom to shift between their performances and back again to their own lives – with all the advantages from which their subjects were distinctly withheld. Being museum ethnologists at the USNM afforded them the means to create exhibits that realized their ideas about cultural and racial difference in a nationalistic space, mimicking Indigenous bodies that were under the punitive control of the US government. This potency of a combined geographic and authorial position, however, clearly influenced how nineteenth century museums exhibited the concept of anthropology. For example, this medial position divided the world into the ‘periphery (the colonized countries) and center (the museums of the Western world)’ such that collecting and displaying ‘emphasized a division inherent in the power relationships of colonialism’ (Laukötter Citation2011: 184).Footnote11

The human body also became the essentializing site through which colonial power materialized within museums and, therefore, an axis of power around which difference was manifested:

… bodies are not so much the origin but rather the battleground of negotiating identity and ascription; they serve as carriers and markers of imputed difference. This is especially true for culture contacts; during the age of European expansion, physical characteristics described in terms of ‘racial’ – and, as an implicit or explicit deduction, behavioral or cultural – difference often made bodies the sites that served to explain and legitimate power relations. (Thode-Arora 2011:141)

Participant observation – an insider approach that relied on empathy, subjectivity, and close contact with one's subjects – existed in continual tension with the analytical system building of objective, outsider comparative anthropology. Like … vanishing Indian ideology, ethnography offered powerful-and powerfully conflicted-ways of seeing, conceptualizing, and interacting with both Indian people and other Americans. (Deloria Citation2022, 1993)

… it is clear that the men in the National Museum were ‘playing Indian’ in a presumptuous manner. The danger and limitation in the method lay in assuming that demonstration of supposed conditions and techniques of invention constitute a sufficient anthropology; that knowledge of structure or technical process is, in fact, knowledge of invention or creativity. (Hinsley Citation1994, 105)

Conclusions

A deeper understanding of the experiential knowledge and media-based experiments that were used by USNM ethnologists in exhibit design in the 19th and early twentieth centuries comes from viewing these alongside the philosophical schools of the time, such as pragmatism and ideas about ‘a laboratory state of mind’ (Reck Citation1967). The history I have charted here reveals how technical reproduction and re-enactment methodologies were used to explore the cognitive aspects of humanity. The values ascribed to the making of life groups by the USNM ethnologists can also be compared to similar ones given to scientific models, especially in their use in the externalization and evaluation of the production of knowledge. Similarly, Moormann and Bélanger situate museum dioramas as models that ‘give access to a scientific way of thinking’ (Citation2019, 103), and as such, life groups can be equated with ‘model-based reasoning’ (Citation2019, 106). As Étienne has also suggested, life groups operate as ‘images having a cognitive dimension’ which ‘play an important role in the elaboration of scientific understanding’ (Étienne Citation2017, 58). As I have demonstrated here, by employing these media-based processes of realization, USNM ethnologists tested out emerging anthropological concepts, either emphasizing race or sociality, or both.

To summarize, this inquiry around proto-subdisciplinary anthropology within the USNM reveals a more creative multi-media and cognitively experimental field of investigation than previously depicted. It is also one that considers the non-lexical aspects to the early practice of anthropology in museums. Methodologies underlying the USNM’s production of exhibits forged now overlooked intersections between art, psychology, history and science, and between what we now conceptualize as social ‘narrative’ and physical ‘data’ – endeavours that can be seen at this early stage in the disciplines’ development to have positioned anthropology as a social science. As such, this museum-based community of practice attempted to create ‘forms capable of giving expression to a new and expanded conception of humanity’ (Grimshaw Citation1997, 37). Ultimately, for the USNM ethnologists discussed here, the study of culture was sought in both physical and material realms (bodies and material culture), as well as the mind (cognitive development and psychology), thereby conceiving these as connected. Furthermore, the locus of culture was in their synthesis as a means to uncover the evolution of the mind over time. Through exploring what I have term their ‘processes of realization’, which include the materialization, externalization, and critique of ideas via exhibits, I show that bodies became materialized objects of study into how the mind developed cultural traits over time. This approach, while still based in evolutionary schemas, reveals the developmental stages of methodology in sociocultural, physical, and cognitive anthropology before these concepts emerged as discrete subdisciplines.

In reflecting on the relevance of this history today, museums like the NMNH continue to undergo transformation as sites that necessitate the development of experimental collaborative communities of practice. This is especially the case with recent explorations in developing new collaborative approaches to curatorial principles designed to address Indigenous critiques of the colonial legacies of museums (Ames Citation1992; Peers and Brown Citation2003; Lonetree and Cobb Citation2008). Indigenous informed approaches to museums are also shaping the renegotiation of unequal cultural power dynamics via Indigenous ontologies and concepts of being (Isaac et al. Citationforthcoming). Rather than retaining the ‘museum method’ and evolutionary schemas as anthropology’s only legacy for museums, the concept of the ‘museum as process’ – a phrase used by Ray Silverman (Citation2014) to think about how we learn through the ‘messiness’ of collaboration – is pertinent here. The ‘museum as process’ imagines a dialectical approach to anthropology in museums, alongside an increasingly central role for communities and the privileging of cross-cultural and culturally responsive ways of realizing, communicating, and critiquing theories about diversity and humanity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In his essay ‘Does Anthropology Still Need Museums?’ William C. Sturtevant (Citation1969) classifies the ‘museum period’ as spanning from 1840–1890, with a subsequent phase ‘the museum-university period’ from 1890–1920. My study looks at the practices at the USNM between the 1870s to the 1900s, and therefore understands that it is considering museum practices across these two phases.

2 According to Ira Jacknis, the phrase ‘museum method’ was used by Boas (Citation1893) and formed the analytical framework for Jacknis’ essay ‘Franz Boas and Exhibits: On the Limitations of the Museum Method in Anthropology’, in George Stocking’s Objects and Others (Citation1985).

3 In Ira Jacknis’ exploration of exhibits produced for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, he discusses the extent to which USNM staff adhered to the evolutionary theories: ‘the personnel at Chicago represented a transition in anthropological culture theory. The older generation, such as Mason and Holmes, were resolute evolutionists. Cushing was somewhat intermediary, combining a comparative evolutionism with localized ethnography. Mooney and Boas represented a more progressive cultural relativism’ (Jacknis Citation2016, 266). Also see Isaac (Citation2005) on how the use of photography in the field contributed to ethnologists’ comprehension of social change.

4 See the Free Library of Philadelphia catalog for photographs from the Philadelphia Centennial – the Centennial Exhibition Digital Collection: https://libwww.freelibrary.org/CenCol/index.htm Subjects for the life-groups exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition included: ‘Laplander and Reindeer’, ‘The Clockmaker’, ‘Baby’s Death’, ‘The New Baby’ and ‘The Dying Elk’, all of which appeared in the Swedish section, and ‘Laplanders from Norway’ and ‘Norwegian Peasants’ in the Norwegian section of the exposition.

5 It is not clear why Boas is incorrectly cited as the one who introduced anthropological mannequins and life groups to the US, but this most likely because less has been written about Mason, Holmes, and Cushing as the ethnologists who experimented with them initially. For example, the misperception that ‘the person responsible for exporting them to the New World was Boas’ (Etienne Citation2017, 59).

6 The face casts commissioned by Baird represent the beginning of a practice that, by 1915, had become a major preoccupation of the physical anthropologist Ales Hrdlička’at the NMNH, who started using it during fieldwork and as a technique to collect and transport to the museum physical duplicates and measurements of people’s faces, eventually amassing hundreds of casts for the national collections (Isaac and Colebank Citation2023).

7 Artists such as the French sculptor, M. Achille Colin, produced the portrait bust of a Yankton Sioux woman named Kan-Ku-Wash-Te-Win (The Good Road Woman) and a Medawankaton Sioux man named CheTa-Wau-Kou-Va-Ma-Ni (The Hawk That Hunts Walking). These were then painted by the artist, A. Zeno Shindler (1813 or 1823–1899). The artist U. S. J. Dunbar (1862–1927) created the full-length mannequin of Rosa White Thunder – a pupil at the Indian School at Carlisle – to display her traditional dress in the exhibit halls. Dunbar used the face casting method to get an accurate copy of White Thunder’s features. Likewise, in pursuing the most accurate features of his subjects, the artist Theodore Mills created a figure of a Bantu boy ‘from life’ as well as with the aid of casts (Goode Citation1895, 54).

8 Fowler and Parezo (Citation2017) note that the term ‘laboratory’ was also used for the spaces at world fairs organized for anthropometric practices, with Boas operating one at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and a larger one being organized for St Louis in 1904 (Fowler and Parezo Citation2017, 394). While these had a narrower purpose in comparison with the exhibit-based Lab at the USNM, which oversaw a wider range of activities, both can be seen as spaces to produce material-based knowledge as well as the performance of ethnographic knowledge collected in the field.

9 A. E. Haddon’s obituary for Balfour, Balfour Papers, Pitt Rivers Museum. Balfour often found stone-tool making difficult and admitted that ‘I have at times tried flint arrow head making but cannot master at all the surface flaking’ (emphasis original, Balfour to Hough, 17 March, 1891).

10 It is worth noting the difference between the images of NMNH ethnologists posing for mannequins in which they are unclothed and therefore provide anatomical information for each pose, versus the photographs they had taken of them re-enacting technology and/or object manufacture for which they are fully clothed, indicates the emphasis for these latter types was more about the material process, rather than anatomical information.

11 At the USNM, Mason was interested in emulating concepts based on Gustav Klemm’s natural history methods exploring environmental contexts, evolutionism, and the perceived stages of a developmental hierarchy, which gave rise to his ‘geo-ethnic’ life groups. These ‘early Smithsonian life groups were intended to link the prevailing ideas by Smithsonian anthropologists about environmentalism with theories of race and evolution’ (Arnoldi Citation1999, 706). As such, these life groups ‘served rather than questioned the superiority of Victorian American culture’ (Hinsley Citation1994, 112).

References

- Altick, Richard D. 1978. The Shows of London. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press.

- Ames, Eric. 2009. Carl Hagenbeck’s Empire of Entertainments. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Ames, Michael 1992. Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Arnoldi, Mary Jo. 1999. “From the Diorama to the Dialogic: A Century of Exhibiting Africa at the Smithsonian's Museum of Natural History.” Cahiers d'études africaines, Prélever, exhiber. La mise en musées 39 (55–156): 701–726.

- Audouze, F. 2002. “Leroi-Gourhan, a Philosopher of Technique and Evolution.” Journal of Archaeological Research 10: 277–306. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020599009172.

- Austin, Michelle, Natalie Firnhaber, Lisa Goldberg, Greta Hansen, and Catherine Magee. 2005. “The Legacy of Anthropology Collections Care at the National Museum of Natural History.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 44 (3): 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1179/019713605806082301

- Barringer, Tim and Tom Flynn, eds. 1998. Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum. London: Routledge.

- Bennett, Tony, Fiona Cameron, Nelia Dias, Ben Dibley, Rodney Harrison, Ira Jacknis, and Conal McCarthy, eds. 2017. Collecting, Ordering, Governing: Anthropology, Museums and Liberal Government. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Blanchard, Paul, ed. 2012. Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage. Arles: Actes Sud.

- Boas, Franz. 1893. “Ethnology at the Exposition.” A World’s Fair, 1893.” A Special Issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine 15 (5): 607–609.

- Bronner, Simon J. 1989. “Object Lessons: The Work of Ethnological Museums and Collections.” In Consuming Visions: Accumulation and Display of Goods in America, 1880–1920, edited by Simon J. Bronner, 217–254. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Coombes, Annie. 1997. Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Cushing, Frank H. 1892. “Manual Concepts: A Study of the Influence of Hand-Usage on Culture-Growth.” American Anthropologist A5 (4): 289–318. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1892.5.4.02a00020.

- Darnell, Regna. 1969. “The Development of American Anthropology 1879–1920. from the Bureau of American Ethnology to Franz Boas.” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

- Darnell, Regna. 2021. The History of Anthropology: A Critical Window on the Discipline in North America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- DeArmey, Michael H. 1986. “Anthropological Foundations of William James’s Philosophy.” In The Philosophical Psychology of William James, edited by Michael H. DeArmey and Stephen Skousgaard, 17–40. Washington, DC: Center for Advanced Research in Phenomenology and the University Press of America.

- DeGroff, Daniel. 2012. “Ethnographic Display and Political Narrative: The Salle de France of the Musee d’ethnographie du Trocadero.” In Folklore and Nationalism in Europe During the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Timothy Baycroft and David Hopkin, 113–135. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004211834_008.

- Deloria, Philip. 2022. Playing Indian. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, Chris Gosden, and Ruth B. Phillips, eds. 2006. Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture. Oxford: Berg Press.

- Étienne, Noémie. 2017. “Dioramas in the Making: Caspar Mayer and Franz Boas in the Contact Zone(s).” Getty Research Journal 9: 57–74.

- Étienne, Noémie. 2020. Les Autres et les ancêtres – Les dioramas de Franz Boas et d’Arthur C. Parker à New York, 1900. Dijon: Les presses du Réel.

- Fear-Segal, Jacqueline, and Rebecca Tillet, eds. 2013. Indigenous Bodies: Reviewing, Relocating and Reclaiming. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Ewers, John C. 1959. “A Century of American Indian Exhibits in the Smithsonian Institution.” In The United States National Museum, The Smithsonian Report for 1958, 513–552. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Fitzhugh, William. 1997. “Ambassadors in Sealskins: Exhibiting Eskimos at the Smithsonian.” In Exhibiting Dilemmas: Issues of Representation at the Smithsonian, edited by Amy Henderson and Adrienne Kaeppler, 206–245. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Fowler, Don D., and Nancy J. Parezo. 2017. “Nomenclature Wars: Ethnologists and Anthropologists Seeking to Be Scientists, 1840-1910.” Journal of Anthropological Research 74 (3): 388–411. https://doi.org/10.1086/698699

- Glass, Aaron. 2009. “Frozen Poses: Hamat’sa Dioramas, Recursive Representation and the Making of a Kwakkwaka’wakw Icon.” In Photography, Anthropology and History, edited by Christopher Morton and Elizabeth Edwards, 89–118. London: Ashgate Press.

- Glass, Aaron. 2010. “Review Essay: Making Mannequins Mean: Native American Representations, Postcolonial Politics, and the Limits of Semiotic Analysis.” Museum Anthropology Review, 4 (1): 70–84.

- Goode, George Browne. 1895. Report of the United States Commission to the Columbian Historical Exposition at Madrid 1892-93. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Goode, George Browne. 1896. “Report Upon the Exhibit of the Smithsonian Institution and the United States National Museum at the Cotton States and International Exposition, Atlanta GA., 1895.” In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 1895, edited by The Smithsonian Institution, Board of Regents, 613–635. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Gosden, Chris, and Chantal Knowles. 2001. Collecting Colonialism: Material Culture and Colonial Change. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- Gosden, Chris, and Frances Larson. 2007. Knowing Things: Exploring Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum 1885–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Griffiths, Alison. 2002. Wondrous Difference: Cinema, Anthropology and Turn-of-the-Century Visual Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Grimshaw, Anna. 1997. The Ethnographer’s Eye: Ways of Seeing in Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hinsley, Curtis M. 1994. The Smithsonian and the American Indian: Making a Moral Anthropology in Victorian America. Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington and London.

- Hinsley, Curtis M., and Bill Holm. 1976. “A Cannibal in the National Museum: The Early Career of Franz Boas in America.” American Anthropologist 78 (2): 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1976.78.2.02a00040

- Hinsley, Curtis M., and David R. Wilcox, eds. 2016. Coming of Age in Chicago: The 1893 World’s Fair and the Coalescence of American Anthropology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Holmes, William Henry. 1903. “The Exhibit at the Department of Anthropology, Report on the Exhibits of the U.S. National Museum at the Pan-American Exposition Buffalo, New York, 1901.” In Annual Report of the US National Museum for 1901, edited by The Smithsonian Institution, Board of Regents, 200–218. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Hough, Walter. 1890. “Aboriginal Fire-Making.” American Anthropologist A3: 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1890.3.4.02a00070

- Hough, Walter 1920. “Racial Groups and Figures in the Natural History Building of the United States Museum.” In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 1920, edited by The Smithsonian Institution, Board of Regents, 611–656. Washington, DC. Government Printing Office.

- Isaac, Gwyneira. 2005. “Reobservation and the Recognition of Change: The Photographs of Matilda Coxe Stevenson (1879–1915).” Journal of the Southwest. 47(3): 411–455.

- Isaac, Gwyneira. 2010. “Anthropology and Its Embodiments: 19th Century Museum Ethnography and the Re-Enactments of Indigenous Knowledges.” Etnofoor 22 (1): 11–29.

- Isaac, Gwyneira. 2011. “Whose Idea Was This?” Current Anthropology 52 (2): 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1086/659141.

- Isaac, Gwyneira. 2013. “We:Wha Goes to Washington.” In Reassembling the Collection: Ethnographic Museums and Indigenous Agency, edited by Rodney Harrison, Sarah Byrne, and Anne Clark, 143–170. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Isaac, Gwyneira. 2021. “From Life: Histories of and Contemporary Perspectives on Modeling Humankind at the Smithsonian.” In Mannequins in Museums, edited by Bridget Cooks and Jennifer Wagelie, 28–44. London: Routledge Press.

- Isaac, Gwyneira, and Sadie Colebank. 2023. “Anthropological Face Casts: Towards an Ethical Processing of Their Histories and Difficult Legacies of Intimacy and Ambiguity.” Journal of Material Culture 28: 324–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591835221123995.

- Isaac, Gwyneira, Klint Burgio Ericson, Lea McChesney, Adriana Greci Green, Karen Charley, Kelly Church, and Wasson Dillard. forthcoming. “Making Kin is More Than Metaphor: Implications from Indigenous Knowledge and Artistic Traditions for Museums.” Museum Anthropology.

- Isaac, Gwyneira. Forthcoming. “Body Politics and Museums: Understanding Face Casts of Native Americans as Sensitive Objects.” In Material Culture of Difficult Histories, edited by Robert Ehrenreich. Ithaca: University of Cornell Press.

- Jacknis, Ira. 1985. “Franz Boas and Exhibits: On the Limitations of the Museum Method of Anthropology.” In Objects and Others: Essays on Museum and Material Culture, edited by George Stocking, 75–111. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Jacknis, Ira. 1990. “James Mooney as an Ethnographic Photographer.” Visual Anthropology 3 (2/3): 179–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.1990.9966532.

- Jacknis, Ira. 2015. “In the Field / En Plein Air: The Art of Anthropological Display at the American Museum of Natural History, 1905-30.” In The Anthropology of Expeditions: Travel, Visualities, Afterlives, edited by Joshua A. Bell and Erin L. Hasinoff, 119–173. New York: Bard Graduate Center.

- Jacknis, Ira. 2016. “Refracting Images: Anthropological Display at the Chicago World’s Fair 1893.” In Coming of Age in Chicago: The 1893 Word’s Fair and the Coalescence of American Anthropology, edited by Curtis Hinsley and David R. Wilcox, 260–336. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Jenkins, David. 1994. “Object Lessons and Ethnographic Displays: Museum Exhibitions and the Making of American Anthropology.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 36 (2): 242–270. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500019046

- Kalshoven, Petra Tjitske. 1993. “Magic of the Mannequin: A Guided Look Through the Dioramas in the Mashantucket Pequot Museum.” Acta Americana: Tidskrift För Svenska Amerikanistsällskapet 16 (2): 5–25.

- Kuklick, Henrika, ed. 2008. A New History of Anthropology. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lonetree, Amy, and Amanda Cobb. 2008. The National Museum of the American Indian: Critical Conversations. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Laukötter, Anja. 2011. “The ‘Colonial Body’ as Object of Knowledge in Ethnological Museums.” In Embodiments of Cultural Encounters, edited by Sebastian Jobs and Gesa Mackenthun. Münster: Waxmann.

- Manderson, Lenore. 2019. “Humans on Show: Performance, Race, and Representation.” Critical African Studies 10 (3): 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2019.1610009

- McGee, William James, et al. 1900. “In Memoriam.” American Anthropologist 2 (2): 354–380. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1900.2.2.02a00100.

- Moormann, Alexandra, and Charlene Bélanger. 2019. “Dioramas as (Scientific) Models in Natural History Museums.” In Natural History Dioramas—Traditional Exhibits for Current Educational Times, edited by A. Schhersoi and S. D. Tunncliffe, 101–112. Spring Nature Switzerland.

- Parezo, Nancy J., and Don D. Fowler. 2007. Anthropology Goes to the Fair: The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Peers, Laura and Alison K. Brown, eds. 2003. Museums and Source Communities. London: Routledge.

- Pratt, R. 10H. 1878. “Catalogue of Casts Taken by Clark Mills, Esq., of the Heads of Sixty-Four Indian Prisoners of Various Western Tribes, and Held at Fort Marion, Saint Augustine, Fla., in Charge of Capt.” In Proceedings of the United States National Museum, edited by R. H. Pratt, 201–214. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Qureshi, Sadiah. 2011. Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rathburn, R. 1906. “General Work on the Collections.” In Report on the Progress and Condition of the United States National Museum for the Year Ending June 30, 1906, edited by The Smithsonian Institution, Board of Regents, 28–32. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Reck, Andrew J. 1967. Introduction to William James. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Redman, Samuel J. 2016. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Roldan, Arturo Alverez and Han Vermeulen 1995. Fieldwork and Footnotes: Studies in the History of European Anthropology. London: Routledge Press.

- Rydell, Robert W. 1985. All the World's a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sandberg, Mark B. 2003. Living Pictures, Missing Persons: Mannequins, Museums, and Modernity. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Silverman, Raymond, ed. 2014. Museum as Process: Translating Local and Global Knowledges. London: Routledge Press.

- Stocking, George, ed. 1985. Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Stocking, George, ed. 1991. Victorian Anthropology. New York: The Free Press: Maxwell Macmillan Inc.

- Sturtevant, William C. 1969. “Does Anthropology Need Museums?” Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 82: 619–649.

- Turner, Hannah. 2020. Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Varutti, Marzia. 2017. “Materializing the Past: Mannequins, History, and Memory in Museums. Insights from the Northern European and East Asian Contexts.” Bodyworks. Nordisk Musesology, I, S.5–S20.

- Vawda, Shahid. 2019. “Museums and the Epistemology of Injustice: From Colonialism to Decoloniality.” Museum International 71 (1-2): 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13500775.2019.1638031

- Wakeham, Pauline. 2008. Taxidermic Signs: Reconstructing Aboriginality. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Westerkamp, Willem. 2015. “Ethnicity or Culture: The Career of Mannequins in (Post) Colonial Displays.” In Sites, Bodies and Stories: Imagining Indonesian History, edited by Susan Susan Lege^ne, Bambang Purwanto, and Henk Schulte Nordholt, 89–112. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Zittlau, Andrea 2011. “Dreamlands of Culture: Ethnographic Dioramas and their Prospects.” In Embodiments of Cultural Contact, edited by Sebastian Jobs and Gesa Mackenthun, 161–179. Münster: Waxmann.

Unpublished Sources

- National Anthropological Archives (NAA)

- Henry Balfour, letters to Walter Hough: April 28, 1890; December 13, 1890 (Walter Hough Papers ca. 1889-1930).

- Reports of the Anthropology Laboratory 1913–73. Department of Anthropology (DOA) Series 11, Box 70, Anthro Lab 1-2.