ABSTRACT

Focusing on humorous cartoons about the Conquest published between 1945 and 1970 in an Argentinian popular comic magazine and on a Colombian educational and politically militant comic-book narrative history of the same events, published in 1978, I analyse how the publications used mixed temporalities when relating historical events. I challenge the common idea that disrupting linear timelines by mixing temporalities necessarily has politically progressive effects. The humorous cartoons typically portray Indigenous Americans from the fifteenth century as ‘primitives’ who nevertheless behaved in ‘modern’ ways, but this temporal disruption in fact works to erase the responsibility of dominant classes for Indigenous disadvantage. In contrast, the educational comic-book brings Indigenous people from the conquest into the present, talking directly to the readers and interpellating them as comrades in the struggle. Yet this comic-book also portrays Indigenous people in generic stereotyped ways, illustrating the difficulty of shaking off these colonial ‘recursions’ (Ann Stoler).

Introduction

In this article, I look at the way encounters between Europeans and Indigenous Americans have been depicted in twentieth-century Latin American comics of very different types.Footnote1 I focus on an Argentinian weekly publication (1944-1972) called Rico Tipo, light-hearted and humorous, addressing a wide audience; and on a 1978 Colombian publication, a 90-page booklet called La resistencia indígena al conquistador (Indigenous resistance to the conquistadors), with a serious pedagogical and, one might say, decolonial approach, which had limited distribution. The reason for comparing two such different publications is, first, that they both portray the fifteenth-century Spanish conquest of the Indigenous population of the Americas and, second, that they both make use of mixed temporalities, shifting between the past and the present in particular, sometimes anachronistic, ways. My aim is to interrogate the political effects of mixing temporal frames and to challenge that idea that disrupting linear timelines in this way is likely to have progressive results.

I argue that the use of mixed temporal frames in Rico Tipo, in which Indigenous Americans from the fifteenth-century Caribbean are made to appear in some ways as ‘modern’, has specific and contradictory effects. While Indigenous people are constantly and stereotypically portrayed as very different from Europeans and having conflicting interests, they are also made to seem similar to twentieth-century readers in having remarkably ‘modern’ attitudes and values. This conveys the idea of an underlying common humanity, which may seem progressively egalitarian in its undermining of what Fabian (Citation1983) calls allochronism and Kirtsoglou and Simpson (Citation2020) call chronocracy – the denial of coevalness by assigning of non-Western peoples to the past, which is a key element in their depiction as Other. However, because these ‘modern’ attitudes involve the possession of worldly-wise street smarts – known in Argentina as viveza criolla (native wit or shrewdness) – the ultimate effect is to displace any idea of Indigenous peoples as victims of, or of having been disadvantaged by, conquest. It places them on an equal footing with twentieth-century Argentinians, not just as humans but as citizens and economic actors, thus freeing the urban reader from any sense of moral responsibility for the present-day consequences of conquest on Indigenous Argentinians.

La resistencia indígena also depicts fifteenth-century Indigenous Americans in stereotypical – albeit now straightforwardly heroic – fashion and it mostly locates them as actors in the past. But the comic also locates them in the reader’s present, not by having them display anachronistically modern attitudes as in the Rico Tipo cartoons, but rather by having them directly address the readers from the page, looking out at them and speaking to them in the present tense. This use of mixed temporalities invites affective solidarity from the reader in a progressive political project to challenge the inequalities of the past and present. However, this political effect is still haunted by traces of temporal and stereotypical othering. The comic’s authors try to disrupt linear temporalities and make Indigenous people coeval with the readers and thus also their equals, but it is hard to shake off the insistent images of Indigenous people as generic ‘non-moderns’.

In the next section, I explore some approaches to the representation of time and its political effects, focusing on allochronism and anachronism. I show that allochronism has been perceived as a tool of dominance, while anachronism, which mixes temporalities and ‘queers’ the linear timeframe of allochronism, has been seen by some as disruptive and politically progressive. However, I observe that this effect is far from guaranteed. Next, I analyse time in the Rico Tipo cartoons where anachronism appears to make indios into coevals of the readers, but also absolves the readers of ethical responsibility for racialised oppression. A subsequent section analyses how the pedagogical comic-book also uses anachronism to make indios temporally and politically equal to the reader, but with the very different progressive intent of highlighting ethical accountability. However, this intention is undermined by durable traces of allochronistic othering.

Mixed temporalities and power relations

The political effects of temporal framing in the textual and visual representation of people and societies were described for anthropology by Fabian (Citation1983) with his critique that the discipline made a subordinate Other of contemporary non-Western peoples by locating them in the past, a process he termed ‘allochronism’. Anthropology (at least until the 1970s) aimed to represent some ‘original’ version of ‘primitive’ society (in the sense of denoting an early evolutionary stage), masking the fact that data were collected in the political economy of colonialism. People who were in fact contemporary with the Western anthropologist were being located in a distant past represented by the anthropologist. Techniques for achieving this included the anthropologists’ absenting themselves, as present-day subjects, from their ethnographic accounts and also using the ‘ethnographic present’ tense in their descriptions, which created an air of timelessness and denied historicity.

For Fabian, this could be classified as mere anachronism, narrowly understood as an error of chronology.Footnote2 But this was not enough: ‘I am trying to show that we are facing, not mistakes, but devices (existential, rhetoric [sic], political)’. These devices were complicit in and reproduced colonial relations of power to such an extent that Fabian argued that ‘a clear conception of allochronism is the prerequisite and frame for a critique of racism’ (Citation1983, 32, 202).

Importantly, although Fabian was focusing on anthropology and ethnographic writing, he located his critique in a broad account of the function of temporality in Western scientific and philosophical discourses (Fabian Citation1983, ch. 1). Anthropological allochronism is rooted in ideas about progress, modernity, civilization and barbarism that have been foundational to Western thought, historiography, art and literature; ideas that, in Latin America (and elsewhere), consistently associate Indigeneity (and Blackness) with the past and white Europeanness with ‘modernity’ across a range of visual and textual representations (Alberto and Elena Citation2016; Aguiló Citation2018; Rifkin Citation2017; Rose and Vuletić Citation2018; Nederveen Pieterse Citation1992; Pacheco de Oliveira Citation2016; Muñoz-Rojas Citation2022; Mills Citation2020; Sá and Pereira Citation2020; Casagrande, Lincopi, and Martínez Citation2022). Almost forty years later, inspired by Fabian, anthropologists Elizabeth Kirtsoglou and Bob Simpson, coined the term chronocracy, which they defined not only in relation to anthropology but also more generally as ‘the discursive and practical ways in which temporal regimes are used in order to deny coevalness and thereby create deeply asymmetrical relationships of exclusion and domination either between humans (in diverse contexts) or between humans and other organisms and our ecologies’; for them, ‘Western historicism’, based on ideas of progress, is ‘one of the building blocks of chronocracy’ (Citation2020, 3, 9).

Analysts in other disciplines have also noted the way depictions of time interweave with exclusion and domination. For example, literary scholar Valerie Rohy sees nineteenth-century racial science and sexology as casting both black (and other non-white) people and homosexuals as archaic, primitive ‘anachronisms’ in a world in which linear temporal schemes led towards a white heterosexual modern future. For her, anachronism refers to representing certain things as temporal anomalies: black and homosexual people did not fit properly in the modern world and thus should be ‘prevented, punished, or expelled’ (Rohy Citation2009, xiv).

Like Fabian and Rohy, philosopher Jacques Rancière sees temporality as linked to power relations. In his account, linear temporality organizes particular ‘scientific’ approaches to writing history – he takes aim at the French Annales school – according to which historians should understand each epoch in its own terms, including its particular ‘regime of truth’. For such an approach, the ‘mortal sin’ of anachronism then consists in viewing one (past) period through the lenses of another (usually contemporary) one (Citation2015, 26). For Rancière, the idea of anachronism is a means of policing the linear periodization that sees time as divided into successive periods or epochs, each with its own characteristics. Like Rohy, he sees anachronism as an accusatory label that has disciplinary effects.

However, some scholars see critical potential in mixing different temporalities by placing things in time frames where they are deemed by dominant views not properly to ‘belong’ and to be anomalous, untimely and anachronistic. In Rancière’s view, things that are ‘out of their time’ should not be discounted as anachronisms, but understood as elements that may create change and unsettle the status quo of a particular epoch. Whereas Rancière prefers not to speak of anachronism as such, believing that we need to think in terms of a ‘multiplicity of lines of temporality present in any "one" time’ (Citation2015, 46), others positively welcome the concept. Literary scholar Jeremy Tambling says that ‘being anachronistic has the potential of unsettling readings of history which see the times as moving forward steadily’ and that anachronism ‘counters a reading where events happen within a definable historical framework, with "before" and "after", cause and effect’ (Tambling Citation2013, 2, 4). Also from literary studies, Mary Mullen observes that postcolonial and queer theorists ‘celebrate anachronism as a visible site of dislocation that calls what counts as timely and what constitutes history into question’ (Mullen Citation2018, 567).

In anthropology, seeing critical potential in bringing distinct temporalities together is evident in Fabian’s collaborative work with the Zairean painter-historian Tshibumba Kanda Matulu in the 1970s (Fabian Citation1996). Fabian consciously avoids comparing Tshibumba’s History of Zaire, drawn from his own experiences, with an academic account deemed more chronologically veracious: for Fabian, an escape into relativism is unnecessary ‘when we grant to Tshibumba’s History the same status we must grant to academic historiography’ (Citation1996, 316). Both accounts properly belong to the present moment and we have to live with these mixed temporalities. Although he does not use the term, Fabian clearly sees this as a way to avoid the othering effects of allochronism (Fabian Citation1996, ch. 5). Likewise, Alfred Gell’s critique of anthropologically relativist approaches to time and his insistence on ‘a unifying approach to time as an organising principle of human affairs’ is described by Kirtsoglou and Simpson (Citation2020, 6) as an attempt to ‘banish precisely this allochronism’ – although Gell (Citation1992) does not use the word and he and Fabian do not cite each other’s works.

On the other hand, and in line with her general contention that ‘history is always ahistorical, progress is inextricable from backwardness, and that the time lines of the past live on in today’s difficult conversations’ (Citation2009, xvi), Rohy argues that mixing temporalities in the form of anachronism does not have a single political valence. Anachronism can unsettle linear time by working against its grain and creating ‘undecidability’ (Rohy Citation2009, xvi). But anachronism can also be constitutive of linear temporalities, because the thing defined by them as a temporal anomaly (e.g. black people, homosexuals) acts as the Other in relation to which the desirable is defined; thus the label of anachronism can even haunt queer and anti-racist projects that attempt to challenge these straight white temporalities.

In sum, anthropological ideas about power and temporality can illuminate the analysis of time in a range of disciplines and media. This includes comics, particularly because ‘comics have the aptitude to make various temporalities coincide within a single panel’ (Baetens and Pylyser Citation2016, 308).Footnote3 My overall argument is that, while allochronism and the denial of coevalness are established techniques of power, evident in many fields of knowledge, attempts to counter them by simply mixing temporal frames – for example, through anachronisms – are not straightforward. The task is to assess the different effects – existential, rhetorical, political – of Rancière’s multiple ‘lines of temporality’ that are present in a given context.

The comic side of temporal anomaly

I argue that these serious-minded reflections on temporalities and their political valences and effects apply to comics such as La resistencia indígena, which had a serious-minded purpose, albeit packaged in an accessible way, but also to more light-hearted comics, such as Rico Tipo. In fact, it is very relevant that a common use of temporal anomaly is in humour and, especially, satire. Humour can of course be used as a tool in conveying any kind of message, progressive or reactionary. Even political satire can have contradictory effects: it has ‘the capacity to promote scrutiny of political life yet also dumb down political critique’ as Noelle Molé (Citation2013, 291) argues for late twentieth-century Italy, in a context in which satire was being consumed by a cynical audience that enjoyed the frisson of a satirical jibe, but whose apathy ultimately colluded in the behaviour that was being satirized or in the status quo that gave rise to that behaviour.

So what difference is made by presenting mixed temporalities in a funny or light-hearted way? The use of humour allows the writer or performer to draw in an audience by inviting them to share laughter and by extension the, often tacit, values underlying the joke or satire (Sue and Golash-Boza Citation2013). The affective draw of the invitation to share laughter is such that one may laugh in spite of oneself, automatically smiling at a joke that arises from values one rejects, especially if other people are laughing along and apparently accepting the values. Humour also invites readers to suspend disbelief in – and withhold critique of – the exaggerations, simplifications and stereotypes being used to make a satirical point or joke, even if the joke aims to contest the hierarchies underlying the stereotypes. This is one reason why, as Matthias Pauwels (Citation2021: 91) remarks, ‘it may prove impossible to have the counter-hegemonic effects of racial stereotype humour, without also unleashing its hegemonic effects’. Rejecting the joke or gravely critiquing the exaggerations and stereotypes means assuming the role of ‘killjoy’ (Ahmed Citation2023). That this is a hard and disruptive role to adopt is testament to the power of humour to enjoin conformity to the values it expresses.

However, the power of laughter is more salient in some circumstances than in others. I believe that the more counter-intuitive the content of the message being conveyed, the more prominent humour will be in the delivery of the message. Incongruity is funny in itself and the greater the incongruity being conveyed, the funnier it can be. But the reverse is also true: the greater the incongruity, the more it depends on humour as a medium for the message.

The comics and cartoons I analyse below show interesting uses of mixed temporalities in their depictions of encounters between Indigenous Americans and European conquerors in 1492 and after. The comic format combines image and text in successive panels to narrate a story, while the cartoon uses the image/text combination (or sometimes just an image) in a single panel to evoke or suggest a narrative that is often a stock, almost mythical, storyline. In both cases, elements of graphic exaggeration, visual stereotype and the incongruities of anachronism all indicate to the reader a clearly humorous intent or simply a certain lightness of touch. However, as I show below, the incongruity of the mixed temporalities is particularly strong in the case of the Rico Tipo cartoons – the audience is asked to accept, for a moment, a blatantly fantastic premise – and as a result they aim for absurdity and the belly-laugh. In contrast, in the graphic educational history of La resistencia indígena, the aim is mostly to make serious matters more approachable for a diverse audience and so the incongruity of the mixture of temporalities is less salient and the tone is more light-hearted than absurd and laugh-out-loud.

Both cases reinforce the argument I made above that mixing temporalities has no single political valence, but what is intriguing and revealing are the complex and ambivalent effects produced. Far from being simply a voice from the past, which is either made to represent Otherness or used to critique twentieth-century Western society, Indigenous Americans from the fifteenth century are made to display traits of modernity, in ways that generate varied meanings. Linear timelines are disrupted in absurd and jarring ways in Rico Tipo, but, as I demonstrate below, this does not result in effects that one might want to ‘celebrate’, as anachronism has, according to Mullen, been celebrated by recent postcolonial and queer theorists. For La resistencia, the disruption of temporal linearity is harnessed to a self-consciously ethical project of political solidarity, which some people (myself included) might want to celebrate – yet the reader is also asked to indulge portrayals of Indigenous people that are much more stereotypical than the depictions of Spaniards. Ambivalence and complexity characterize the effects overall.

Rico Tipo cartoons

Rico Tipo (published in Argentina, 1944-72) was a humorous, slightly racy magazine with a satirical edge, without being primarily a satirical publication. The magazine’s founding director Guillermo Divito aimed Rico Tipo at a middling urban sector and it had its greatest success in 1940s and 1950s: by 1945 it was already printing 350,000 copies a week and it even influenced middle-class ideas about fashion. In the late 1960s it began to decline, as more liberal attitudes to sex made its timid salaciousness seem a little dated, while government repression made political issues, which Rico Tipo did not address, seem more relevant.

I focus on cartoons that were produced to commemorate the 12 October, the anniversary of Columbus‘s first encounter with Indigenous Americans on the Caribbean island of Guanahani, a date often called El Día de la Raza (the day of the race) in Latin America.Footnote4 Popular depictions of Indigenous figures in twentieth-century Argentina had a contradictory role (Alberto and Elena Citation2016; Gordillo and Hirsch Citation2003). On the one hand, nation-building elites liked to highlight the racially ‘whitening’ and morally ‘civilising’ effects of the massive European immigration the country had experienced between the 1870s and 1940s. This migration had overlapped with late nineteenth-century genocidal military campaigns in the rural hinterlands to crush and displace Indigenous communities. Famous paintings of that period depicted Indigenous people as marauding barbarians, attacking the forces of civilization. By the 1940s, real Indigenous peoples were seen as remnants, marginal and barely visible.

However, while a white Europeanized national image was highly valued, some kind of authenticity was needed to lend national distinctiveness. Here, a caricatured and domesticated Indigeneity could be harnessed to the quality of criollo. The term criollo (creole), widely used in Latin America, refers to American-born people and things that are seen as largely European but, because of their birth and development in the America, are likely to have elements of Indigenous (or, in some countries, African) ancestry as a result of processes of mestizaje (the cultural and biological mixture between Indigenous, European and African populations that generated ‘mestizo’ [mixed] people). In Argentina, things criollo are proudly valued based on their authentic roots in el pueblo (the people, the masses), who often have Indigenous and African ancestry (Adamovsky Citation2014; McAleer Citation2018; Vitulli and Solodkow Citation2009). A famous example of an Indigenous figure harnessed to this criollo agenda is Patoruzú, a comic-strip Tehuelche chief, whose adventures featured in the extremely popular eponymous magazine (1936-1977), in which he is constantly referred to as indio (‘Indian’), but also portrayed as criollo (McAleer Citation2018; Merino Citation2015).

Indigeneity in the mid-twentieth century was thus marginalized, but also present as ‘a tense absence, a non-recognized force that was nevertheless there as a latent point of reference in hegemonic narratives’ (Gordillo and Hirsch Citation2003, 5). For the middle-class Argentineans, who ‘feared to be seen as indios by Europeans or North Americans’, anxieties ‘about the "subtle Indianness" of the country’ (Gordillo and Hirsch Citation2003, 5) were exacerbated after 1946 with populism of president Juan Perón (1946-1955), which not only gave political space to the dark-skinned working classes, but also framed the emerging struggles of Indigenous groups, exemplified by the 1946 march on Buenos Aires by Kolla people from the north-west demanding land titles (Gordillo and Hirsch Citation2003, 14). Middle-class readers of the Rico Tipo period would therefore have been accustomed to seeing Indigenous figures portrayed in the comforting style of Patoruzú, allaying anxiety about the nation’s – and their own – ‘subtle Indianness’.Footnote5

A full collection of Rico Tipo is held by the National Library, which archives many publications of this kind. I reviewed seven issues from 1945, 1950, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1968 and 1970, with about 50 cartoons and four front covers. Over this period, there were some marked changes in political climate, but this was not obvious from the cartoons, which retained a consistent flavour throughout.Footnote6 The theme of encounter was often featured on the relevant issue’s front cover, drawn by Divito himself, while the centre-fold spread featured multiple cartoons on the topic. The diverse artists involved gave a different graphic style to the images, but the themes and jokes were similar over time.

Linear temporalities in Rico Tipo

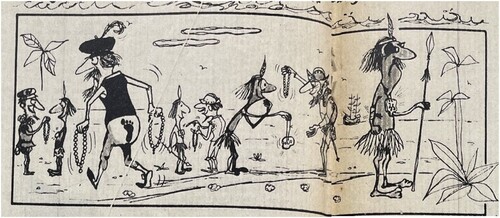

Although anachronism is a salient feature of the Rico Tipo cartoons, there is also a strong sense in which a more linear temporality operates, in which Indigenous people are portrayed as primitive Others. In the scenes of encounter, which often take place on the beach at the ‘moment’ that Columbus and his crew first met the native population, the cartoons depict Indigenous Americans as stereotypically different from Europeans. The Indigenous Americans are dressed in loincloths or grass/feather skirts (and bikini-like tops in the case of women), headbands with feathers, armbands and shell necklaces. The Europeans wear clothing of the period: doublets, breeches and hose, often with military accoutrements (helmets and cuirasses).

The depiction of the bodies of the Indigenous Americans depends on the graphic style of the artist. For example, in the 1945 issue (which featured colour for the cartoons located in the inside pages), ‘Fantasio’ (Juan Gálvez Elorza) drew all his figures as tall, thin, and with small or sharp noses; he was unusual in drawing the Indigenous Americans as very dark-skinned with big red lips; one man is shown with a bone in his hair. Stereotyped cartoon images of Africans and possibly Polynesians are evoked. In the same issue, ‘Oski’ (Oscar Esteban Conti) shows Indigenous Americans as short, rotund and big-nosed, like all his figures, but also dark-skinned. In Toño Gallo’s 1950 cartoons, Indigenous Americans are shown as darker-skinned than the Spaniards, but not by much; the main difference is in the clothing. Likewise, in 1960, ‘Quino’ (Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón) gives Indigenous Americans and Spaniards slightly different skin colours and very different attire. Interestingly, Pedro Seguí changed from shading the Indigenous Americans’ bodies in 1968 to drawing them as identical in skin colour to the Spaniards in 1970, when clothing was the only difference. Overall, although there is a tendency over time to background the phenotypical in favour of the cultural, difference is always clearly drawn.

Standardized, almost mythical, versions of difference are also apparent in the cartoons’ portrayal of the exchanges that take place in the encounter of two distinct worlds. In three issues (1950, 1960 and 1970), Europeans are shown giving beads and mirrors in exchange for gold. While this has some basis in historical fact (Keehnen and Mol Citation2021), it is also an element in a mythical story about the ‘Discovery’, in which Indigenous Americans happily give up items of great value in return for trinkets – as judged by European standards. This, of course, uses an image of Indigenous Americans as innocent and naïve – and outside modern times – to mask the value that Indigenous Americans attached to their gold artifacts as well as the violence Europeans routinely used to expropriate them.

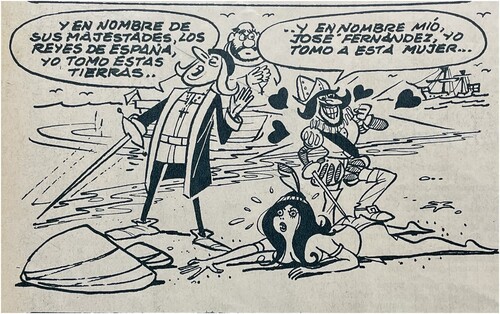

The images frequently reference other historico-mythical elements, which are linked to scientific and economic rationalities and temporalities – e.g. that Columbus’s voyage was intended to prove the world was round; that his voyage was financed by Queen Isabella pawning her jewelsFootnote7 – but the most recurrent is the depiction of sexual encounters. In thirteen cartoons, European men are shown as lusting after, being love-struck by or chasing native women, who may accept their advances or not, with native men on five occasions depicted as reacting to these relationships in different ways – with resentment, suspicion or amused indifference. The complexities surrounding sexual encounters between Indigenous Americans and Europeans during the early colonial period are legion (Wade Citation2009, ch. 3). But the point here is the reiteration of the idea that a foundational relation that led to the colonial societies that would become Latin American nations was non-violent, consensual sexual encounters, which engendered the mixed (mestizo) populations that would later be used in nationalist narratives as emblems of national identities. Only in one 1970 cartoon by Seguí (text by R. Lavalle) is violence implied (see ): Columbus stands on the beach imperiously claiming the land in his majesties’ name; beside him, a grinning conquistador, with his boot on the backside of a prostrate curvaceous and startled-looking Indigenous woman says ‘And in my name, José Fernández, I take this woman … ’ (7 October 1970).

Figure 1. Cartoon by Pedro Seguí; text by R. Lavalle. Rico Tipo, 7 October 1970.

(Source: Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno de la República Argentina).

Thus far the dominant temporal frame is the linear timeline of primitive Indigeneity being taken by the modernizing forces of European conquest. This encounter is presented as non-violent and as being facilitated by the liminal space of the beach that recurs in these cartoons and that mediates between opposed elements, softening their antagonism. The encounter is also shown as kick-starting a linear process of mestizaje that would eventually lead to nationhood. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – and into the twenty-first (Wade Citation2017) – mestizaje was parsed by nation-building elites as temporally structured in ways that associated Indigenous and African origins with the past and backwardness (although also with a distinctive national authenticity, as we have seen), while Europeanness was seen as modern and forward-looking.

Mixed temporalities in Rico Tipo

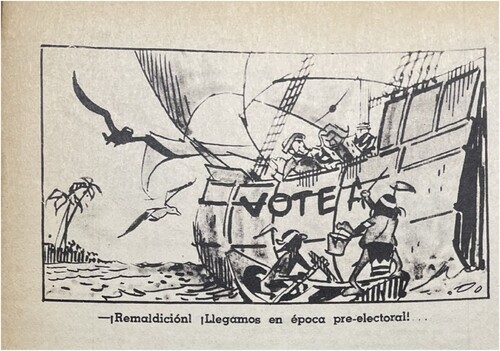

The unsettling of linear timelines, on the other hand, is also a striking feature of these cartoons. The Indigenous Americans are routinely depicted as exhibiting anachronistically modern behaviours, which leave the fifteenth-century Europeans startled and bewildered. The absurd incongruity is designed to amuse the cartoons’ readers. Virtually every cartoon has some element of this.Footnote8 In one issue (11 October 1945), Fantasio depicts an Indigenous American as a customs officer, upbraiding a dismayed Columbus for smuggling treasure, saying ‘So, contraband, eh?’. In another cartoon in the same spread, an Indigenous American man asks Columbus: ‘How are things going in Europe?’. A 1961 cartoon by Gallo (see ) shows Columbus arriving in his ship La Niña only to encounter the Indigenous Americans already daubing the sides of his vessel with electioneering slogans, ‘Vote … ’. Columbus curses: ‘Damn it all, we arrived in the run-up to elections’ (11 October 1961).

Figure 2. ‘Damn it all, we arrived in the run-up to elections’. Cartoon by Toño Gallo, Rico Tipo, 11 October 1961.

(Source: Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno de la República Argentina).

In the 1950 series, Gallo draws a three-panel comic strip showing Columbus giving a piece of cloth to a surprised and pleased Indigenous man; in the final panel the man is shown at a market stall giving a sales pitch to two young women beneath a sign that says ‘Cloth imported from Europe’ at $35 pesos a metre (11 October 1950). A neighbouring panel shows Indigenous Americans in a canoe parlaying with Columbus on his ship. In the canoe, there is a life belt and one man wears a white nautical cap. An Indigenous man shouts: ‘The pilot says a tow to the dock will cost you ten little mirrors and twenty coloured beads!’

This theme of Indigenous Americans having modern business acumen and a profiteering mentality is repeated in a 1960 cartoon by Quino that shows a classic beach scene with pairs of conquistadors and Indigenous Americans in the background, happily exchanging strings of beads for gold artifacts (12 October 1960). In the foreground, a disgruntled Spaniard is exiting stage left, holding his strings of beads. Displaying a bare footprint on his backside, he has evidently been sent packing by an Indigenous man standing stage right, with his back turned to the Spaniard, holding a spear and with a jeweller’s loupe in his eye (see ). We surmise that he examined the beads with an expert eye and found them to be wanting. Quino also shows an Indigenous man talking to Columbus, saying, ‘I’ll stay here, don Cristóbal: now we’ve discovered America, I can invent the American bar!’ He gestures at another Indigenous man in the foreground wearing a pair of cool sunglasses.

Figure 3. Cartoon by Quino (Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón), Rico Tipo, 12 October 1960.

(Source: Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno de la República Argentina).

Malicia indígena

The depiction of a modern, profiteering, market-driven mentality in fifteenth-century Indigenous Americans needs to be seen in relation to the concept of malicia indígena (literally, Indigenous malice). An idea that has been developed mostly in Colombia (Morales Citation1998), it refers to a kind of awareness, smartness and wiliness that Indigenous peoples supposedly evolved to deal with colonial oppression, though evasion, duplicity and always having an eye for chances to cunningly avoid onerous impositions or gain some advantage. This quality is said to have become part of the national character, having been assimilated into the trait of being vivo (literally alive, but figuratively smart, astute), with both negative and positive aspects. On the one hand, having malicia indígena or being vivo means you can get ahead in difficult circumstances through smart problem-solving; you can overcome fate and cleverly empower yourself by turning disadvantage into something beneficial. On the other hand, it means you will push in front of others, treading them underfoot in your determination to gain advantage for yourself, and you will bend or ignore the rules, deploy underhand tactics and cheat, leading to a lack of respect for others, a disregard for principles of fairness and a disdain for the rule of law, leading to endemic corruption.Footnote9

Interestingly, a trait that is associated with Indigenous origins has become assimilated into the national character through the temporal advance of mestizaje, losing some of its Indigenous identity when it becomes viveza (the quality of being vivo). The concept of viveza criolla, found particularly in Argentina but elsewhere too, makes this especially clear (Hein Citation2020).

In their hard-headed and canny dealings with the Spanish, the fifteenth-century Indigenous Americans in the Rico Tipo cartoons display classic viveza criolla. They show themselves to have the traits associated with mainstream twentieth-century Argentinian culture and its people, many of whom like to see themselves as having mostly European ancestry, but who nevertheless value criollo cultural traits. The malicia indígena that the cartoon Indigenous Americans display is not any longer really Indigenous, but is viveza criolla and thus an element of the national culture – for good or for bad.

The effects of anachronism in Rico Tipo

I argue that the pervasive use of anachronism that makes Indigenous Americans seem modern and savvy aligns them with the readers of Rico Tipo and their everyday knowledge of the world – especially twentieth-century Argentinian society. This is far from the classic temporal distancing and othering techniques that Fabian refers to for anthropology and that others have noted for a range of knowledge practices. In some senses, allochronism is indeed at work in the linear temporality suggested by the stereotyped depictions of indios, the portrayal of foundational encounters, the invocation of well-known myths about Columbus and the repeated allusions to the originary sexual encounters that initiate the narrative of mestizaje (even if, in the Argentinian case, the national myth of mestizaje was displaced by the recent immigration of Europeans, which facilitated a story about the country as white and European – although still criollo …). In another sense, allochronism is powerfully belied by the depiction of fifteenth-century indios as possessing the viveza criolla seen by readers as typical of their own urban society.

However, I argue that this unsettling of linear timelines does not align with postcolonial or queer critiques of straight white temporality, which value anachronism’s bringing of the marginal, the forgotten and the erased into ‘the present’, thus countering dominant narratives about the order of things. The very depiction of the Indigenous Americans as ‘modern’ and particularly the suggestion that Indigenous people are vivos implies that they are the same as the reader in a specific way: the depiction of them as wily, astute and shrewd suggests they would feel at completely at home in the market-driven world of twentieth-century Argentinian capitalism and commercialism.

This evocation of a timeless homo economicus inside both twentieth-century Argentinians and Indigenous Americans, including in the fifteenth century, has the effect of displacing any moral responsibility away from European colonists and white Argentinians for the negative impacts they have had on Indigenous Americans. These cartoon vivos were certainly not victims. They were out for what they could get, whether in fifteenth-century encounters between Europeans and Indigenous Americans, or in the late nineteenth-century Argentinian context in which Indigenous peoples were branded as barbarian marauders and cattle thieves and crushed in genocidal military campaigns, or in the mid-twentieth century context of Peronist populism and the stirrings of Indigenous protest.

Readers of Rico Tipo could feel safe with the suggestion – packaged as an absurd joke – that Indigenous people were, and are, no more victims than them. The cartoons’ anachronism short-circuits any of the distanced reflection and stepping back from everyday routines and normative frames that Laidlaw (Citation2002) identifies as central to the process of deciding how to live an ethically good life. It provides the readers with an everyday, routinized way of thinking about Indigeneity by assimilating it to their familiar world – and thereby also giving readers a safe ethical space in which to locate themselves, insofar as ‘how I respond to the claims of the other, as well as how I allow myself to be claimed by the other, defines the work of self-formation’ (Das Citation2010, 377). The effect of anachronism is to by-pass all thorny questions of responsibility by flattening time and asserting equality of agency in the market place of society.

La resistencia indígena al conquistador

This 90-page didactic and educational book – subtitled ‘la historia de las luchas de nuestros antepasados’ (the history of our ancestors’ struggles) – is very distant from the cartoons of Rico Tipo. The booklet, published in a third edition in 1978, has no information about its publisher, but a copy of it is held by El Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP), a Jesuit institution created in 1972 in Bogotá, Colombia, whose archives include this kind of popular pedagogical material, shaped by Marxism and Liberation Theology. The booklet takes a clearly decolonial approach, in line with CINEP’s stated goal of adopting ‘a critical and alternative view of Colombian reality’ and working with ‘a preferential option for excluded communities and victims’.Footnote10 Yet it too uses anachronism in conveying its message and, although the effects are different from those produced by the Rico Tipo cartoons, there are certain subtle parallels that undermine its decolonial intent.

The Colombian racial formation is different from the Argentinian one. The ideology of mestizaje as the keystone of national identity has been more powerful and, although whitening has been a strong element, it never gained the dominance made possible in Argentina by mass European immigration. Indigeneity and to a lesser extent Blackness have long been a more visible aspect of national identity, although Black and Indigenous peoples have always been politically and economically marginalized (Wade Citation1993; Citation2000). From a background of resistance by rural workers and subsistence farmers, which included the 1966 formation of the communist guerrilla force, FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia), the 1970s saw the emergence of a self-consciously Indigenous national movement centred on the fight for land rights, exemplified in the 1971 founding of the pioneering organization CRIC, Consejo Regional Indígena del Cauca (Cauca Regional Indigenous Council).

This is the context in which the educational comic-book appeared. The front cover shows a drawing of fifteenth-century Indigenous warriors fighting conquistadors; the title page has a photograph of an Indigenous man, identifiable from his dress as from the northern Sierra Nevada region, with his fist raised; inside there is a presentation text outlining the need to convey the history of centuries-long resistance by Indigenous peoples and ‘el Pueblo Colombiano’ (the Colombian people), identified as a mix of Spaniards, indios and negros. The history of struggle is linked to the contemporary presence of ‘guerrilla groups fighting in the mountains’. The text is signed by Centro de Estudios Antonia Santos in Bucaramanga, a major Colombian city.Footnote11 The booklet ends with a statement taken from a pamphlet issued in 1973 by CRIC, which highlights the struggles of various Indigenous peoples, but also says the struggle involves all the campesinos (small-scale farmers) in Colombia.

The comic in the booklet gives a detailed history of the conquest of the area that became colonial New Granada, with separate chapters on the conquest of specific territories (Cartagena, Santa Marta, Popayán, the lands of the Chibcha people). The comic adopts a format that is familiar from this kind of publication, with the narration being delivered to the reader by two campesinos talking to each other, one acting as ignorant listener/questioner, the other being the teacher/explainer.Footnote12 The narrators use speech bubbles and there are also panels of free-standing text that do much of the narration and explanation. Other panels show various actors, such as Indigenous Americans, conquistadors, Spanish royalty and churchmen (but no Africans), who use speech bubbles to convey the action.

Mixed temporalities show up in various ways in the comic. First, anachronism of the Rico Tipo sort occasionally appears: fifteenth-century characters use modern idioms of speech. For example, an Indigenous man, speaking of Peru, says (42), ‘esa joda queda po’allá abajo’ (that funny business [i.e. the country] is down there [i.e. to the south]).Footnote13 Or a conquistador, facing concerted Indigenous resistance, is shown saying (56), ‘Las cosas se están poniendo peludas por estos lados’ (things are getting hairy [difficult] around here). The effect of this is not satirical or even very humorous; like the whole comic format of the book, it is an attempt to engage the reader and make the material easily approachable. The reader is not being asked to accept an incongruity that is as absurd and fantastical as in the Rico Tipo cartoons, therefore humour is not so important as a lubricant.

Also anachronistic in simple fashion is the irruption into the flow of the narrative of single panels showing twentieth-century Latin American individuals, presented as continuing the legacy of the conquistadors. The Chilean dictator Pinochet appears twice, wearing sunglasses with skulls on the lenses; a Colombian army commander, Alvaro Valencia Tovar, is shown once, claiming to have ‘the same blood’ as the conquistador Francisco García Tovar. The incongruity here is much greater, but the plainly satirical intent of the juxtaposition persuades the reader to suspend disbelief.

But this simple kind of anachronism does not exhaust the way mixed temporalities work in this comic. Mixed temporal frames work in what seems, at first sight, a quite straightforward way. In one temporal frame, the two narrators are contemporaneous with the reader: they talk to each other but also look directly out from the page at the reader and they describe events in the past tense. The free-standing blocks of text also address the reader directly and speak in the past tense. In another temporal frame, the characters located in the fifteenth-century generally do not look out from the page at the reader: they look off to the side or at another adjacent character and they generally talk in the present tense. This is different from the so-called historic or dramatic present frequently used in Spanish, when a narrator speaks to a contemporary audience about the past, but using the present tense in order to give an air of immediacy. In contrast, the present tense used by the comic characters places them and the action in the past, where they talk to each other, while the reader observes them from a temporal distance.

However, on closer examination, there are significant variations here. Occasionally a conquistador – or a churchman – will appear to look at the reader and/or will talk in the past tense, both of which actions implicitly locate him in the same time frame as the reader. Very rarely does a conquistador both look at the reader and use the past tense in a single drawing.Footnote14 Other exceptions are occasional peripheral characters, such as pirates, who appear just twice, also looking at the reader and describing actions in the past tense.

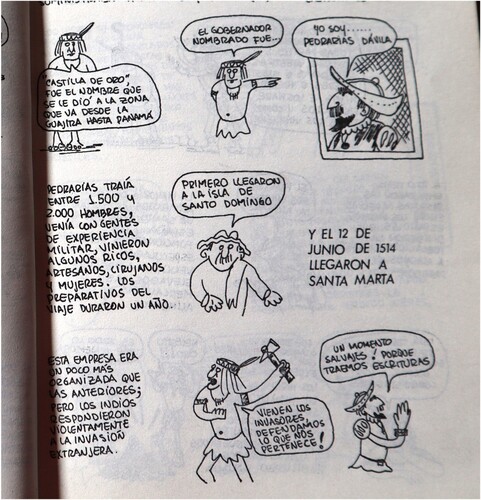

In clear contrast, Indigenous Americans often break out of their fifteenth-century past, looking directly at the reader and speaking in the past tense at the same time.Footnote15 They even frequently adopt the role of narrator alongside the two campesinos. Within the space of a few panels, they move back and forth between being in the fifteenth century, where they interact with conquistadors in the present tense, and speaking in the past tense to describe events of the conquest to the twentieth-century reader (see ). The effect of this is to locate the Indigenous Americans in the distant past, while at the same time making them anachronistically contemporary with the reader – at a very different level from the occasional temporal break-outs performed by conquistadors and churchmen.

Figure 4. Page from La resistencia indígena al conquistador, 3rd edition, Bogotá, 1978.Footnote16

(Source: Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular, Bogotá).

As with Rico Tipo, then, the Indigenous American appears as a time traveller, but the end results are different. Far from erasing the reader’s moral responsibility by casting the Indigenous people as non-victims, the comic makes abundantly clear who is to blame for the crimes of the past. The named conquistadors and bishops are all portrayed as violent, rapacious, duplicitous and greedy, whereas the generic indio comes across as heroic and brave. A connection is made to the legacy of these crimes in the present, via the very occasional use of military figures, such as Pinochet, and the bookending of the comic narrative with militant political statements, which link the conquistadors to present-day guilty parties, identified as ‘the exploiting class’, ‘the exploiters’, ‘a small group of families who own the government and weapons’, ‘gringo-thieves’, landowners, millionaire cattle-ranchers and oil companies. It is also clear where the readers are located in this moral universe: the opening presentation text addresses the readers as compañeros – literally companions, but roughly equivalent to the English term comrades, as used in left-wing circles. That text also interpellates ‘those who fight for their land’ and ‘those who suffer hunger and poverty’.

The mixed temporalities of the comic thus try to create an affective bridge between Indigenous people who resisted during the conquest and the comic’s intended audience which is Indigenous people, campesinos and ‘el Pueblo Colombiano’, but also the young people who populate the country’s ‘schools and colleges’ in which, the text says, ‘false history’ is taught. The reader is asked to identify with the subaltern classes, racialized as indio, negro, or mestizo, who are clearly identified as the victims of the morally bankrupt ‘exploiting class’, albeit victims with agency and a legacy of brave and effective resistance. Notably, the temporal incongruity of fifteenth-century indios talking directly to a modern reader is not very funny: at most it perhaps produces a sympathetic smile. The underlying invitation to political solidarity is not in itself incongruous and therefore has less need of the lubricating power of humour.

However, this affective political interpellation of the reader is undermined by the presence of clearly linear time lines and associated allochronism and Othering. Indigenous Americans are stereotyped, homogenized and very rarely individuated. They are uniformly show as wearing loincloths, armbands and headbands with a feather – except for one Chibcha person who wears a long robe and an Indigenous narrator who for a few pages appears wearing a short robe with one shoulder strap. Only on four occasions is an Indigenous American named, all of whom are historical caciques (leaders, chiefs); otherwise they are unnamed or sometimes referred to by ethnonym (e.g. Chibchas, Quillacingas, Quimbayas) or located by reference to a place name. In contrast, in addition to Columbus and the king and queen of Spain – not to mention a French pirate – over thirty-five historical Spanish figures are individually named, including four bishops. Of course, it may not have been possible to name as many Indigenous historical figures, but it would have been possible not to name as many Spaniards. In addition, many named conquistadors are drawn differently, with heavier inking or as a simulacrum of a colonial engraving (see ), slowing the reader’s gaze and giving the figures more individuality than the Indigenous Americans who are all drawn with simple lines that speed up the gaze. The generic portrayal of indios and the individuation of Spanish people work against the stated aim of the comic-book to highlight the agency and resistance of Indigenous people. It aligns with allochronic timelines of Eurocentric modernization.

Conclusion

The Rico Tipo cartoons, while evoking a background of primitivized Indigenous otherness, work as jokes by highlighting the starkly incongruous placing of the present into the past. This gives the Indigenous Americans an air of ‘modernity’, which challenges the simple allochronism that, in Western knowledge practices (including anthropology) – at least pre-1970s – and in national narratives of Latin American mestizaje, routinely places Indigenous people in the past and sees them as incongruous in the ‘modern’ urban world. But, by the same token, making them seem ‘modern’ in the specific sense of possessing viveza criolla collapses inequalities of power and thus removes from the reader any sense of ethical responsibility. The cartoons work temporally in two directions simultaneously, partially reinscribing colonial, scientifically racist and eugenicist views of Indigenous primitiveness, while also doing the opposite by de-primitivising Indigeneity, but in a way that evades ethical issues by denying that Indigenous people were victims in histories of conquest and subsequent relations of Indigenous people with mainstream Argentinian society.

The comic La resistencia indígena also has this dual temporality. The indios anachronistically address readers in the present, interpellating them as compañeros, while simultaneously being depicted as generic figures acting in the distant past. As opposed to Rico Tipo, where modern behaviours are grafted onto fifteenth-century Indigenous Americans, in this educational comic Indigenous people from the conquest are being transported to the present, talking to the reader in the past tense about what happened long ago. The effect is to highlight, rather than evade, issues of moral responsibility. The Indigenous person brought into the present acts as a critical friend to the reader, interrogating not only the past, but the legacies of that past in the present. Yet the generic indio located in the past remains as a clear trace in this comic-book, standing in for present-day Indigenous peoples.

What does this tell us about the political valence of mixing up temporalities? One might think that when it brings the past into the present – which from one point of view is close to being simply ‘history’ or the idea that the past somehow shapes the present, which is one definition of what historians study – mixing temporalities often has a retrogressive politics insofar as it involves what Ann Stoler calls the ‘recursion’ of imperial elements – e.g. stereotyped indios located in the past – into post-imperial social formations in the form of ‘partial reinscriptions, modified displacements, and amplified recuperations’, as opposed to straightforward continuities (Stoler Citation2016, 27). This supports oppressions and inequalities. History gives us a way of revealing these recursions and putting them into critical perspective and maybe judging them as undesirable. La resistencia indígena comic both reproduces and challenges those recursions. When mixing temporalities brings the present into the past, as in Rico Tipo, the effect is different and perhaps more disruptive of linear temporalities. But, as we have seen, the apparent temporal disruption of these cartoons has more politically conservative aspects in its erasure of inequalities and violence.

The comparison of Rico Tipo and La resistencia indígena indicates that, although the artists of the former used time frames to devictimize Indigenous people and thus give comfort to their non-Indigenous readers, the creators of the latter, in using time frames to highlight victimization and its responsible parties and invite solidarity from their readers, still found it hard to avoid the stereotypes that sustain racialized hierarchies. In sum, Rancière’s idea that there is a ‘multiplicity of lines of temporality present in any “one” time’ (Citation2015, 46) means that these lines can be articulated to weave narratives with very different political effects. Mixing temporalities and disrupting standard timelines does not always produce effects that should be celebrated, while even disrupting temporality for progressive purposes may still be haunted by colonial recursions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This article draws on the project Comics and Race in Latin America (AHRC grant AH/T004606/1), directed by James Scorer, on which I am Co-Investigator. I would like to thank James and other colleagues on the project, Abeyamí Ortega and Malena Bedoya, as well as Jasmin Wrobel, for comments on earlier drafts. Thanks also to the anonymous peer reviewers for History and Anthropology.

2 The OED defines anachronism as ‘the placing of something in a period of time to which it does not belong’. Sub-types include prochronism, ‘an error in chronology that places an event earlier in time than its true date’ and parachronism ‘an error in chronology, especially the placing of an event later than its real date’ (OED).

3 While some anthropologists, such as Dimitrios Theodossopoulos and Nayanika Mookerjee, use comics as a collaborative mode of representation, anthropology has not contributed much to the analysis of comics themselves. See, however, Rappaport (Citation2018, Citation2020).

4 La raza in this context usually refers to populations seen as having a distinctive biocultural heritage, influenced to a greater or lesser extent by Indigenous contributions (Hartigan Citation2013). Celebrations of the Día de la Raza were common in Latin America after the Unión Iberoamericana proposed a commemorative day in 1913. Recently, 12 October has been renamed in some countries. Argentina, for example, now officially calls it Día del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural (day of respect for cultural diversity), while in Nicaragua it is the Día de la Resistencia Indígena, Negra y Popular (day of Indigenous, Black and popular resistance).

5 On the use of a Black figure, ‘el negro Raúl’, in a comic of the period, and his relation to middle-class identity, see Alberto (Citation2022).

6 The period 1945–1970 saw shifts from populism under Juan Perón, through nominal civilian rule with the military behind the scenes, to overt military rule (from 1968).

7 By 1492, most literate people accepted the world was round. Royal jewels were often pawned during this period to generate ready cash, but it is unlikely that this was the source of funding for Columbus’s trip (Desai Citation2014).

8 The same pattern can be found in other comics, such as Argentina’s Avivato (see e.g. 13 October 1958) and Colombia’s Mini-Monos (see e.g. 13 October 1973).

9 Gil and Sabayu (Citation2023), of the Wiwa people of Colombia, argues that the negative aspects, parsed as malicia indígena, are linked to Indigenous people, while the positive aspects, seen as being vivo, are valued as part of the Colombian national character. Apparently in Spain the phrase malicia indígena is being used to target Latin American immigrants as untrustworthy (Ana Vivaldi, personal communication, 15 February 2023).

11 Antonia Santos (1782-1819) was a grass-roots independence rebel leader from the region around Bucaramanga, whose name adorns city neighbourhoods, schools and an army brigade.

12 For a similar format, see Historia ilustrada de América: 500 años de resistencia indígena, negra y popular, by Felix Posada and Gelman Salazar Roque (Bogotá, 1992, 3rd edition, 5 vols.).

13 Joder as a verb (lit. to fuck; fig. to mess about/up, annoy) dates from the eighth century (spelled foder), but joda as a noun (joke, fun, annoyance) is a more recent usage.

14 In over 930 drawings of individual actors, a conquistador looks out at the reader and talks in the past tense only eight times.

15 An indio looks at the reader and talks in the past tense about 100 times.

16 The text reads:

Indio: ‘Castilla de Oro’ was the name given to the zone between La Guajira and Panama.

Indio: The Governor appointed was …

Spaniard: I am … Pedrarías Dávila.

Text: Pedrarías brought between 1500 and 2000 men; he brought people with military experience, some rich people, artisans, surgeons and women. Preparations for the voyage lasted a year.

Campesino: They arrived first at the island of Santo Domingo.

Text: And on the 12 of June 1514, they arrived at Santa Marta

Text: This expedition was a bit better organised than the previous ones; but the indios reacted violently to the foreign invasion.

Indio: The invaders are coming, let’s defend what is ours!

Spaniard: One moment, savages! We bring scriptures.

References

- Adamovsky, Ezequiel. 2014. “La cuarta función del criollismo y las luchas por la definición del origen y el color del ethnos argentino (desde las primeras novelas gauchescas hasta c. 1940).” Boletín del Instituto de Historia Argentina y Americana “Dr. Emilio Ravignani” 41: 50–92.

- Aguiló, Ignacio. 2018. The Darkening Nation: Race, Neoliberalism and Crisis in Argentina. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2023. The Feminist Killjoy Handbook. London: Allen Lane.

- Alberto, Paulina L. 2022. Black Legend: The Many Lives of Raúl Grigera and the Power of Racial Storytelling in Argentina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Alberto, Paulina, and Eduardo Elena. 2016. Rethinking Race in Modern Argentina. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Baetens, Jan, and Charlotte Pylyser. 2016. “Comics and Time.” In The Routledge Companion to Comics, edited by Frank Bramlett, Roy Cook, and Aaron Meskin, 303–310. Oxford: Taylor & Francis.

- Casagrande, Olivia, Claudio Alvarado Lincopi, and Roberto Cayuqueo Martínez. 2022. Performing the Jumbled City: Subversive Aesthetics and Anticolonial Indigeneity in Santiago de Chile. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press

- Das, Veena. 2010. “Engaging the Life of the Other: Love and Everyday Life.” In Ordinary Ethics: Anthropology, Language, and Action, edited by Michael Lambek, 376–399. New York, NY: Fordham University Press.

- Desai, Christina M. 2014. “The Columbus Myth: Power and Ideology in Picturebooks About Christopher Columbus.” Children's Literature in Education 45 (3): 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-014-9216-0.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1996. Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Gell, Alfred. 1992. The Anthropology of Time: Cultural Constructions of Temporal Maps and Images. Oxford: Berg.

- Gil, Conchacala, and Ismael Sabayu. 2023. “¿Qué es malicia indígena?” Memoriaindigena.org, Accessed 17 February. http://www.memoriaindigena.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/que-es-la-malicia-indigenas.pdf.

- Gordillo, Gaston, and Silvia Hirsch. 2003. “Indigenous Struggles and Contested Identities in Argentina: Histories of Invisibilization and Reemergence.” Journal of Latin American Anthropology 8 (3): 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlat.2003.8.3.4.

- Hartigan, John. 2013. “Translating “Race” and “Raza” Between the United States and Mexico.” North American Dialogue 16 (1): 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/nad.12001.

- Hein, Jan. 2020. “Cultural Keywords in Porteño Spanish: Viveza Criolla, Vivo and Boludo.” In Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication: Meaning and Culture, edited by Bert Peeters, Kerry Mullan, and Lauren Sadow, 35–56. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Keehnen, Floris W. M., and Angus A. A. Mol. 2021. “The Roots of the Columbian Exchange: An Entanglement and Network Approach to Early Caribbean Encounter Transactions.” Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 16 (2-4): 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2020.1775729.

- Kirtsoglou, Elisabeth, and Bob Simpson. 2020. “Introduction: The Time of Anthropology: Studies of Contemporary Chronopolitics and Chronocracy.” In The Time of Anthropology: Studies of Contemporary Chronopolitics, edited by Elisabeth Kirtsoglou, and Bob Simpson, 1–30. London: Routledge.

- Laidlaw, James. 2002. “For an Anthropology of Ethics and Freedom.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 8 (2): 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.00110.

- McAleer, Paul Robert. 2018. “The Multiple Functions of Criollo, Gaucho and Indigenous Symbols in la Historieta Patoruzú, 1936-50: The Conflicts of Peronism, Nationalism and Migration.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 27 (2): 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569325.2017.1402753.

- Merino, Ann. 2015. “Fake Nostalgia for the Indian: The Argentinean Fiction of National Identity in the Comics of Patoruzú.” In No Laughing Matter: Visual Humor in Ideas of Race, Nationality, and Ethnicity, edited by Angela Rosenthal, David Bindman, and Adrian W. B. Randolph, 149–175. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

- Mills, Charles W. 2020. “The Chronopolitics of Racial Time.” Time & Society 29 (2): 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463x20903650.

- Molé, Noelle J. 2013. “Trusted Puppets, Tarnished Politicians: Humor and Cynicism in Berlusconi's Italy.” American Ethnologist 40 (2): 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12021.

- Morales, Jorge. 1998. “Mestizaje, malicia indígena y viveza en la construcción del carácter nacional.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 1: 39–43.

- Mullen, Mary L. 2018. “Anachronism.” Victorian Literature and Culture 46 (3-4): 567–570. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150318000256.

- Muñoz-Rojas, Catalina. 2022. A Fervent Crusade for the National Soul: Cultural Politics in Colombia, 1930–1946. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Pacheco de Oliveira, João. 2016. O nascimento do Brasil e outros ensaios: “pacificação”, regime tutelar e formação de alteridades. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa.

- Pauwels, M. 2021. “Anti-racist Critique Through Racial Stereotype Humour.What Could Go Wrong?” Theoria 68 (169): 85–113. https://doi.org/10.3167/th.2021.6816904.

- Pieterse, Nederveen. 1992. White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rancière, Jacques. 2015. “The Concept of Anachronism and the Historian's Truth (English Translation).” InPrint 1 (3): 21–52. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7VM6F.

- Rappaport, Joanne. 2018. “Visualidad y escritura como acción: Investigación Acción Participativa en la Costa Caribe colombiana.” Revista Colombiana de Sociología 41 (1): 133–156. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcs.v41n1.66272.

- Rappaport, Joanne. 2020. Cowards Don't Make History: Orlando Fals Borda and the Origins of Participatory Action Research. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rifkin, Mark. 2017. Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rohy, Valerie. 2009. Anachronism and its Others: Sexuality, Race, Temporality. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press.

- Rose, Diana C., and Snežana Vuletić. 2018. “Indigenous Decolonization of Western Notions of Time and History Through Literary and Visual Arts.” On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture 5. http://dx.doi.org/10.22029/jlupub-7079.

- Sá, Lúcia, and Felipe Milanez Pereira. 2020. “Painting Racism: Protest art by Contemporary Indigenous Artists.” In Living (il)Legalities in Brazil: Practices, Narratives and Institutions in a Country on the Edge, edited by Sara Brandellero, Derek Pardue, and Georg Wink, 160–178. London: Routledge.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2016. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in our Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sue, Christina A., and Tanya Golash-Boza. 2013. “‘It was Only a Joke’: How Racial Humour Fuels Colour-Blind Ideologies in Mexico and Peru.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (10): 1582–1598. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.783929.

- Tambling, Jeremy. 2013. On Anachronism. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Vitulli, Juan M., and David M. Solodkow. 2009. Poéticas de lo criollo: la transformación del concepto criollo en las letras hispanoamericanas, siglos XVI-XIX. Buenos Aires: Corregidor

- Wade, Peter. 1993. Blackness and Race Mixture: The Dynamics of Racial Identity in Colombia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Wade, Peter. 2000. Music, Race and Nation: Música Tropical in Colombia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wade, Peter. 2009. Race and Sex in Latin America. London: Pluto Press.

- Wade, Peter. 2017. Degrees of Mixture, Degrees of Freedom: Genomics, Multiculturalism, and Race in Latin America. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.