ABSTRACT

At Florida Gulf Coast University, Art Appreciation is a high-enrollment, general education course taught through Canvas, the learning management system. Instead of a traditional print textbook, the course is taught with a text developed by the Art faculty using open-access resources, self-generated images and media, and library resources. This article explores national trends in online course design, as impacted by evolving fair-use standards and increased availability of open-access resources, and provides a case study of the course. It also includes recommendations for librarians, professors, and course designers using open-access resources and subscription-based resources.

Introduction

Textbook affordability has become an issue of national concern, and the movement to replace or supplement textbooks with free online resources and/or library resources is a growing priority in higher education. In fact, in Florida, one metric that impacts state funding of public universities is tuition and textbook costs (Florida Board of Governors [FLBOG], Citation2016). Across the U.S., many academic libraries have already responded to the crisis by offering textbook copies in reserve for their students or helping faculty develop their own content for their courses. In many ways, this is no different from the traditional service librarians have always provided—helping users find, evaluate, and use information. Even when faculty decide to write their own textbooks and develop their own intellectual content, librarians can help them discover and evaluate resources to support their project. In particular, open-access (OA), open educational resources (OER), and online library resources (such as multiuser e-books and streaming video) are well suited for large classes and are easy to embed or link to.

One example of this is at Florida Gulf Coast University. In 2016, the art faculty developed a free online textbook alternative for Art Appreciation in Canvas, the learning management system. This is a high-enrollment, general education course enrolling approximately 450 students a semester in three sections. It is taught by three professors, several preceptor/graders, and a course coordinator. The “textbook,” written by a team of faculty collaborators, is illustrated with a mix of images and video including free online resources (such as YouTube and Flickr), self-generated images and media, and subscription-based resources (such as ArtStor). From the outset, the goal was to produce a course that would stay within fair-use guidelines, as far as these could be understood, and would model best practices in the use and citation of intellectual property in the context of an online, limited-access college course. The Education & Arts Librarian was occasionally consulted on course content and was later invited to teach a section of the course. This article explores national trends in online course design, as impacted by evolving fair-use standards and increased availability of OA resources, and provides a case study of the course. It also includes recommendations for librarians, professors, and course designers using OA resources and subscription-based resources.

Defining open-access (OA) and open educational resources (OER)

Some definition of terms is appropriate here since OA is the preferred term of the authors, as many of the online resources discussed do not completely fulfill all the expectations of an OER. OER commonly refers to a freely available online resource specifically supporting an educational purpose. OERs often include learning content, tools and/or implementation resources (OECD, Citation2007). OA is a broader term referring to freely available scholarly content online (ALA, Citation2017). In this context, a Flickr image, if used for a scholarly purpose, could be an OA resource. However, a YouTube video with substantial pedagogical content or tools could arguably be an OER. In any case, some liberty was taken even when classifying images as OA resources. Images may not be “scholarly” but they are primary sources for art educators. It is likely that the definitions of both terms will continue to evolve as new resources and new delivery methods are created.

National trends in course design and the evolving role of the librarian

An ongoing national trend among subject or department-liaison librarians involves moving the librarian away from his/her office in the library and into the academic department itself. Depending on the resources and staff levels of the individual library, librarians now offer walk-in research consultations in the academic department office, provide specialized research and grant-writing support, advise on program reviews and curriculum changes, and help faculty develop research assignments for their courses. The idea then of librarians assisting faculty in discovering quality content to teach their course, and even participating in teaching the course, is not far-fetched. Of course, this level of service would be limited to the staff levels of the library and the depth of librarian’s subject knowledge.

One might think of course-development services as an extension or intensification of embedded librarianship. In embedded librarianship, librarians are added as a teaching assistant to a course to provide point-of-need research instruction and guidance to students enrolled in a course. This may also include developing research assignments, providing citation help, presenting information literacy sessions online or in-person, answering research questions, participating in discussion forums, or creating self-guided tutorials or learning objects.

Most of the literature regarding librarian course designers explores offering traditional information literacy services through the learning management system in new creative ways. For example, librarians at the University of Maryland, College Park, developed information literacy modules directly in Canvas and were added as librarian-instructors to track student progress. Using a flipped-classroom approach, students completed the module prior to an in-class activity in which teams of students present on information literacy concepts (Carroll, Tchangalova, & Harrington, Citation2016).

Similarly, at Central Piedmont Community College in North Carolina, librarians offer extensive embedded services that have recently developed into some targeted course-design services. A coordinator oversees the embedded program, which includes online information literacy instruction, multiple classroom visits, personal research consultations, and creating course-specific learning objects. Ultimately, the embedded program became difficult to sustain due to the increase in faculty requests for embedded services. Instead, an online course was developed, which included integrated information literacy activities. This proved to be easier to sustain and offered assessment opportunities, such as reviewing annotated bibliographies (Coltrain, Citation2015).

As librarians become more involved in course development and enhanced embedded services, they may find they need to further develop their expertise in the subject area. In a recent study by librarians at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, a librarian providing research assistance to a graduate-level course, Concepts of Research Methodology, first attended continuing education courses related to medical records and health informatics before providing embedded services. The graduate students reported significantly increased confidence in several research competencies, including searching the discipline-specific databases, evaluating sources and writing in APA format (Kumar, Wu, & Reynolds, Citation2014).

The literature is mostly silent on librarians directly helping faculty develop discipline-specific course content beyond information literacy modules, but librarians can begin exploring this opportunity by developing an awareness of how and why faculty use OA or self-developed materials in course design. Perhaps the biggest game-changer in do-it-yourself textbooks using self-generated or OA resources is the proliferation of new technologies that make it easy and fun. For example, in 2012, Kevin Ahern at Oregon State University and Indira Rajogopal designed their own OA textbook, “Biochemistry Free and Easy,” which has been downloaded over 160,000 times. Ahern supplements his textbook with uploaded live lectures on YouTube and “Metabolic Melodies,” in which Ahern personally sings over 100 biochemistry songs (similar to Weird Al Yankovic) (Ahern, Citation2017).

In another example, hospitality faculty at Indiana University/Purdue University decided to publish their own e-textbook specifically for iPads (although the next iteration will be on a universal platform). The faculty not only wanted to save their students money, they also wanted to tailor the content to address real-world trends in the hospitality industry that would make their students more employable after graduation. Many open resources (such as links to hotel Web sites) were used. Some of the advantages of the self-published textbook included low student costs, customized content, easy updating, and control of one’s intellectual property. One critical disadvantage is that many institutions do not yet acknowledge this activity as scholarship and it tends to be overlooked in tenure considerations, although that may change as the concept of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) becomes more universally recognized and appreciated (Coussement, Johnson, & Goodson, Citation2016).

In fact, self-published textbooks, in which the faculty member has full control, may have a significant advantage over OA textbooks. What once was OA can change or transition to another model. Librarians at the University of Windsor secured funding to offer students in some courses OA or commercial e-textbooks in their study to analyze student online vs. print preference. However, “during the study the OA publisher [Flat World Knowledge] transitioned away from a fully open model” (Johnston, Berg, Pillon & Williams, p.68). Although OA e-textbooks was not the main focus of their study, it was interesting that they found that students using e-textbooks indicated a preference for print but they did not seek out a print equivalent, indicating, perhaps, that students will adapt (Johnston, Berg, Pillon, & Williams, Citation2015).

As these examples illustrate, developing a course with OA or self-developed content can be a very creative and rewarding process, yet very time consuming with very little scholarship recognition. In fact, a recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education suggests that the open resources movement has “reaches adolescence” (Gose, Citation2017, para 6). Some educators are even gaining respect for commercially produced textbooks, as they discover that using open materials, organizing them, and continuously maintaining them is much more costly and time consuming than they anticipated. Some institutions are considering a middle-road approach with nominal student fees that would compensate faculty course developers and even pay for full-time OER librarians (Gose, Citation2017).

Currently, librarians appear to be mostly at the marketing and advertising end of the OA conversation. OA marketing is a critical service librarians can offer faculty course designers, and for many libraries with limited staff and resources, it may be the extent of the librarians’ role. Many librarians list OA and OER recommendations on their LibGuides, and their opinions on the quality of these resources are also very abundant in the literature. One example of this is an excellent overview of trusted open software and instructional materials provided by Blake and Morse (Citation2016), but is indicative of the librarian mind-set. Librarians tend to focus on what’s available, expecting the faculty to browse these resources and select what they need. However, as our case study demonstrates, course-designing faculty have very specific information needs in mind and will use whatever is most relevant and easy to access.

Using visual images and audio–visual content: Course-design challenges

The information needs of art and humanities faculty developing new courses and textbook equivalents can present special challenges. For these faculty, visual images and audio–visual content, specifically DVDs and streaming videos, are critical resources and often have more copyright restrictions. A lengthy discussion of current copyright law and the interpretation of fair use, particularly section 107 of the Copyright Act 17 (U.S.C. § 107), is beyond the focus of this article. However, it is worth mentioning that the case study of this course, which utilizes audio–visual content, is reflective of a national trend of frustration among university faculty who need to use short clips of film or media for educational use. This continues to deter faculty from writing their own textbooks or textbook substitutes and from making use of critical resources that enhance students’ educational experience. Currently, there are prohibitions on circumventing technological protection of DVDs and streaming services such as Netflix. Circumvention would allow faculty to create a presentation that would have several short clips shown back to back. Very recently, Decherney and Carpini (Citation2015) represented the College Art Association and the Library Copyright Alliance, among others, in their petition to the U.S. Copyright office to seek “renewal of the previously granted DMCA [Digital Millennium Copyright Act] exemption for motion pictures and DVDs and acquired via online distribution services when circumvention is undertaken” (p. 23).

In fact, one of the authors of this article, Bouché was cited twice in her comments regarding the benefits of the 2012 Fair Use Exemption and her frustrations with obtaining permission to use video clips. Bouché's response (2014) response to the online survey was cited in Decherney and Carpini’s petition (Citation2015):

We wanted to include a major discussion of the work of the environmental artist Andy Goldsworthy, including an excerpt from a video documentary of his work called Rivers and Tides. We obtained the DVD and made several attempts to get permission to use an excerpt but could not even identify or get into contact with the holder of the rights. We would have needed to “unlock” I suppose, if we had ever gotten permission, but we didn’t get that far. So instead we are forced to link to inferior copies on YouTube, which change every semester. (p. 19)

The video discussed above is just one example of several audio–visual resources that were difficult to access for the course discussed below and perhaps is indicative of a common disconnect between library resources and the faculty’s intended use. Even after the librarian purchased the Goldsworthy video for the library, it was not in a format easily accessible to an online course with an enrollment of 450 students a semester, and YouTube proved to be a good temporary solution, with the library copy as a back-up. Today’s librarians need to have a competent working knowledge of the shifting sands of copyright and have good working relations with their faculty to continually seek out new solutions.

In addition to audio–visual content barriers, restrictions to personal photography in foreign countries are another copyright issue that critically impacts art and humanities faculty, since they frequently take their own photos of outside public art and architecture while travelling and intend to use these images later in their courses. “Freedom of Panorama” is the term used to describe the legal constraints that apply to photographing (or using self-made photographs) of copyrighted art and architecture that are in accessible public spaces. This is defined differently in different countries and jurisdictions. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_of_panorama). In some countries, sculpture or architecture whose designs are still in copyright, if visible from the street or a public place, can be photographed and the photo can be used without permission. In other countries, one must get permission from the artist or the architect. The complexities of this issue are such that faculty must plan ahead and educate themselves on the restrictions of each country before they travel.

Still another barrier to obtaining access to images frequently occurs when the copyright is severely restricted. For example, images of works by the twentieth-century artist Pablo Picasso are mostly still in copyright. The rights to use Picasso’s works are so aggressively controlled by the owning entity, that even ArtStor does not have many useable images. Yet one cannot responsibly teach Art Appreciation or concepts like the deconstruction of pictorial space in modern art without at least some discussion of Picasso.

The faculty course designers of Art Appreciation, which will be discussed below, decided to take the risk of including some Picasso anyway, though they kept their use of Picasso to a minimum. To support that minimum, they used their own photographs of Picasso’s works that are on public display in museums, or used photography that was available on repository Web sites or publicly accessible Web sites. The faculty felt that, morally if not legally, they are not damaging Picasso or his heirs, by teaching his works to new generations of undergraduates in the context of a password-protected online classroom. Ultimately, the monetary value of Picasso’s work is enhanced, not diminished, by educating the public about its importance through legitimate academic channels. If the faculty had to pay individual licensing fees to all artists whose works are still in copyright, in order to teach their works, they would not be able to teach modern and contemporary art at all in online courses.

However, the future is looking brighter in other areas, particularly access to online museum collections and other cultural repositories. Increasingly museums, for example, are following the principle enunciated in the federal court decision of Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., which, according to the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, determined that “…copyright-free material also includes faithful photographic reproductions of two-dimensional artworks, which are distinct from the artworks they depict” (College Art Association, Citation2015, p. 7).

In that spirit, many public repositories are becoming less restrictive about the use of their images for teaching, and are making two-dimensional works (and even some three-dimensional works) available for that purpose online. For example, the British Museum posts small images of their holdings on their Web site but freely supplies higher-quality images on request for teaching, images for which they used to charge heavy fees. The Bibliotheque National in Paris explicitly labels many high-quality online images of their older out-of-copyright holdings as being in the public domain.

It is the opinion of lead course designer Bouché, that Google Art Project /Google Cultural institute has also had a positive effect on practice. If a repository has chosen to make images of their older out-of-copyright holdings available through Google Art Project (one of Bouché's favorite sources) there is a reasonable expectation that these images are intended to be used, at least for fair-use purposes like teaching.

Art appreciation at Florida Gulf Coast University, a case study

In 2012, faculty in the Bower School of Music and the Arts of Florida Gulf Coast University assisted by Elspeth McCulloch, a course designer and E-Learning specialist employed by the campus, redeveloped HUM 2510, Understanding Visual and Performing Arts, an existing online core course that was required for all students. The goal was to improve the quality of the student experience and improve the experience of faculty teaching the course.

Rather than using a textbook, as was used previously, the faculty decided to write their own intellectually coherent textbook substitute. The 1,750 students enrolled per semester each saved over $130 that the previous required textbook had cost. Some years later, when the Florida State Legislature mandated a statewide core curriculum, HUM 2510 was retired and the art content from that course was further developed and expanded to create ARH 2000, Art Appreciation.

To create and deliver the course’s content, the designers used Softchalk, a simple Web-authoring interface that allows educators to insert interactive activities, links to external and internal resources, and media (images, video) into lessons. The lessons reside in Softchalk Cloud and are accessed through links in Canvas. The lessons open directly in the Canvas browser or in a new window. From the students’ point of view, they look like Web pages. If Softchalk pages need to be tweaked, they can be revised immediately while the course is running, without having to re-link the lesson or take it down.

Initially, the art and music faculty were very concerned about staying well within Fair Use Guidelines, which at that time were rather narrowly interpreted. For example, for HUM 2510’s music content, the faculty licensed sound files from Naxos, the costs being covered by a lab fee. For images, the designers used Creative Commons licensed materials, many of which were found on Wikimedia or on Flickr, an online service that provides image storage and dissemination. The designers also used ArtStor (which the Library licenses), and self-photographed or self-created images. The copyright information for each image was stored in the metadata of the image file, with an indication of the license type and a link to its source if it came from an online source. With the publication of the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts (2015), the practices of the faculty in building the course were generally found to be well within the guidelines, and even a bit overly restrictive, and images from some additional image sources, like the Google Art Project, were added to the mix. In a few cases, when a needed image was copyright-protected, the faculty obtained written permission directly from the copyright owners. As seen in , most images were cited directly in the Softchalk pages via a credit line under the image.

Figure 1. Screen capture from ARH 2000, showing the student view of one page from a lesson written in Softchalk. Reprinted with permission of Anne-Marie Bouché.

Smaller thumbnail images (such as those used as links) were not credited, but their sources were tracked via the image file metadata. Credit lines were also not used for images used in assessments and assignment prompts, since the information in the credit might have given away too much information or distracted students from focusing on the visual cues only. In most cases, the image was already credited elsewhere in the course.

Video was more difficult. Some videos of Florida Gulf Coast University art students talking about their work were made internally, but most had to be linked from YouTube. This was not ideal because not all of these links are permanent and had to be checked every semester to ensure they still worked. Overall, most of the still photography in the course is Creative Commons licensed or OA content, but video content is mostly provided as links to the online source.

Writing their own content with mainly OA or self-generated media has allowed the designers to create a living course that represents the faculty who teach that course. The course designers customize it to Florida Gulf Coast University, use examples from the immediate environment, and include material generated by our art colleagues and students. With the recent broadening of the scope of fair use in educational settings, Bouché believes this is an option that should be more widely explored, rather than using “lowest common denominator” commercial products or (often rather weak) open Web content.

Self-written content also liberates the course and the instructor, as well as the students, from dealing with third-party vendors of online instructional materials, whose systems are often far from robust and trouble-free, even when their content is wholly satisfactory. For some kinds of courses (Chemistry, Math, e.g.,), Bouché believes third-party vendors might be a better solution, but for art history and art appreciation what commercial publishers have to offer is not interesting enough to justify the expense or the trouble.

As a way of providing self-generated course content, Softchalk or any other Web-authoring tool is more flexible and resilient than video. Unless expertly delivered and professionally produced, video lectures are often tedious to watch, much more so than when seen live in a classroom. Video demands more elaborate technology and skills than many individual faculty members are equipped to provide.

More significantly, it is difficult to modify or update self-generated video. Flaws can be fixed and lessons can be updated very easily in Softchalk as soon as a problem is noticed, whereas a video lecture would have to be re-recorded or expertly edited to make a modification. The natural tendency would be to leave it in its original state, rather than to continually refresh and develop it.

In addition, a lesson delivered as a Softchalk Web page can incorporate interactive learning experiences, such as single-question pop quizzes, hyperlinked pictures and diagrams that can be clicked on to explain the parts, and even games like terminology crosswords (autogenerated by the Softchalk program). Softchalk may not be the perfect tool––it too has its weaknesses and limitations. However, it is easy to learn, easy to use, and quite technically robust. The course designers have not experienced any problems with students being unable to access material on Softchalk Cloud that were caused by the Softchalk interface or server.

A team effort

One advantage of this project was the contributions and unique talents from several individuals across departments. Professor Anne-Marie Bouché, the lead course designer in the course, is a Medieval art historian and former librarian, and thus has a rich subject knowledge and a unique perspective of copyright and OA resources. Professor Patricia Fay is a ceramicist and as a practicing contemporary artist, has knowledge of the technical aspects of art as well as current developments in the contemporary art world. Professor Cori Montoya is an experienced full-time art history instructor who teaches both lower and upper art history courses. She also contributed to and provided feedback on the development of the course. The last module of the course, “Art Now,” was particularly creative and featured “guest lectures” by the Art Gallery Director, John Loscuito, the University Photographer/Graphic Designer and Photography Instructor James Greco and the Associate Professor of Art in Digital Media Design, Michael Salmond. Elspeth McCulloch, formerly of FGCU's E-Learning and Instructional Technology department, is a course designer and e-learning specialist. She was the lead faculty developer's primary collaborator in creating the original course and its successor. In addition to providing course design and technical expertise, she assisted and trained the other team members, and, after the course launched, acted as a preceptor for several semesters, grading assignments in order to evaluate and suggest further improvements to the assignments and their rubrics. Lisa Courcier, the full-time online course coordinator, monitored all activities of three sections of the course to resolve technology issues, ensured grading consistency and fairness, and provided an even distribution of preceptors (graders) to assess student work. She also uploaded the modules from semester to semester, assisted with editing the course, and was copied on all course communication to help answer student questions.

The course-design team enjoyed close collaboration with Rachel Cooke, the Education and Arts Librarian. She did not contribute to the text, but was consulted about some of the visual resources used, copyright issues, and contact information for some of the rights-holders. The librarian has an M.A. in Art History, and has taught the Art History survey course for several years. She is currently one of the instructors of Art Appreciation as well as an earlier version of the course, Understanding Visual & Performing Arts. After the course was developed, Bouché, Montoya, and Cooke taught the beta version of the course for the first two semesters and made additional improvements. In Spring 2017, Bouché, Montoya, and Cooke each taught one section of 150 students, with the assistance of several preceptors and the course coordinator.

The art appreciation modules

As mentioned earlier, Bouché, the Art Historian on the team, a former librarian, was the lead designer of the course and wrote much of the Softchalk text and selected most of the visual resources. As seen in , the one library-subscription resource, ArtStor, was used only occasionally for visual content. The Creative Commons image database via Flickr was the most used resource, indicating that faculty teaching courses are looking for very specific content to fulfill their teaching needs.

Table 1. Visual Media Used in Modules 2–5.

The visual resources listed in differed in terms of image size and resolution and this became critically important during the image selection process. The library database, ArtStor has highly variable image quality, but some of their images are outstanding and zoom in to very high resolution. Flickr, on the other hand, has the advantage of an internal communication system. Users can email anyone who is a member of Flickr directly from Flickr, and many Flickr images are Creative Commons licensed. Some Flickr images are very large, but some are not; however, if you can find it licensed for Creative Commons in Flickr you can use it very easily and if not, permission is usually easy to get by directly emailing the owner of the image.

The librarian on the team had recommended some library-owned architecture e-books, streaming video, and reference sources, but these were ultimately not used. This is a particularly interesting phenomenon because librarians often assume that library-subscription resources are the easiest and safest resource to use for research and scholarship. Faculty course developers however are often not looking for “content” in general, where the narrative is controlled by an outside provider, but for specific examples or units that support the faculty member’s own narrative and vision for their course.

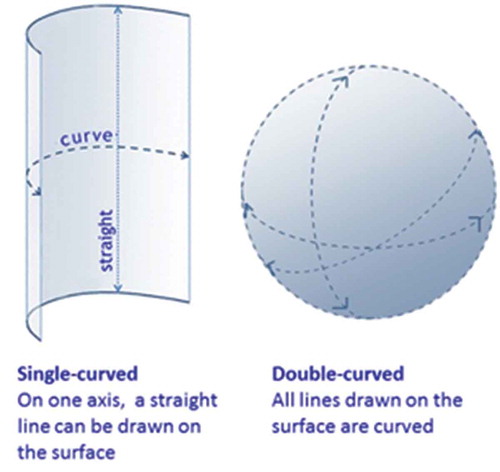

The search for visual resources often extends well beyond the footprint of “academic” collections and archives. Bouché sought out pictures of everyday objects to illustrate course concepts. For example, she used an image of a domed camping tent to illustrate the characteristics of an arcuated structure, and one of an egg to illustrate the mechanical properties of double curvature. The open Web was the most efficient place to find this type of image, but the faculty member would then have to track down the rights holder, whether it was a company or a private individual.

In nearly all cases, she reported that she received a prompt reply and generous permission once the rights holder was informed that the image or video was for educational use and would only be accessed by students currently enrolled in the course. In one case, a commercial photographer shared his historical images of the houses of so-called “Marsh Arabs” in southern Iraq because he thought that their way of life was threatened and that students should be aware of this. Permission was never in fact denied, although two or three queries received no response. Although the process of securing rights may appear burdensome, Bouché reported that she enjoyed this process and formed new relationships with artists and commercial entities all over the world. Most entities contacted were not just willing, but excited by the idea that their images would be used in an educational setting.

Student assessment is not a focus of this case study, but a brief overview of the assignment types and layout of the course, as seen in , may provide some additional background of the course design and the visual resources needed to support the text. It is worth noting that the main modules are organized by art media: architecture, three-dimensional art (sculpture and ceramics), two-dimensional art (painting, drawing, and printmaking), and concluding with more experimental media (global expressions, video games, etc.) explored in a final, “bonus” module called “Art Now”. This organizational scheme would have certainly helped the faculty course designers to systematically search and find similar groups of art objects efficiently in batches. Also, utilizing local resources was a major factor contributing to the success of the course. Two of the major paper assignments required students to write about one of the public sculptures on campus or visit one of the local art exhibitions, of which one popular option has always been a free-admission on-campus exhibition. Similarly, in assignment five, students must make extensive use of the open resource, Google Art Project, in creating their virtual art exhibition.

Table 2. Art Appreciation Course Assessments.

Conclusion and recommendations

This was an exciting, successful project from which the librarian on the team has benefited significantly. When faculty develop their own textbook, they save their students money and may find they enjoy the creative process as well as the freedom to tailor their content to the specific needs of their course. However, it is also a very time consuming (and often frustrating) process both to develop one’s own content and seek (and retain) access to OA material. This achievement often comes with little or no compensation or scholarship credit. Humanities faculty face the additional challenge of accessing audio–visual content, which is critical to their pedagogy. As seen in this case study, the faculty were successful in creating a free text for the Art Appreciation course because they had specific content in mind, were persistent in getting permissions, had good technology (Softchalk), and benefited from the collaborative efforts of experts across the campus. They were also motivated to save their students money and to have a course that was uniquely relevant to their students’ success.

Having a new perspective on the challenges and opportunities of teaching this course, the librarian can provide the following recommendations to other librarians who want to provide enhanced research services to their faculty course designers. Likewise, the faculty course developers have provided additional tips to faculty designing their own course.

Recommendations for librarians assisting course designers

First, and perhaps most importantly, librarians should continue to aggressively market library-subscription and library-recommended OA materials as an alternative to traditional textbooks to save students money. Even if only one textbook is replaced, students will appreciate the savings. Promoting library resources in this way is simply a continuation of a basic service that librarians regularly provide, so this is low-cost to implement.

At a higher service level, librarians can save faculty members precious time by assisting them in searching for resources. It is important to find out exactly what they need. Just like any other patron served, faculty have a very specific information need to be filled. When helping course designers, conduct a full reference interview to determine that information need, when they need it, what format they need it, and what permissions they need.

Librarians should remember that course design is very time consuming and faculty are under intense time constraints, working toward getting their course up and running by a “drop-dead” due date. They may not have the luxury of time to browse for library e-books, reference sources, or streaming video via the catalog. Offer to search the catalog and databases for them and create permanent URLs. Embedded librarians can even offer to paste these URLs into modules and monitor access issues. Many faculty may not know the full extent of what is available nor the “bells and whistles” of specialized resources which may become critically useful (app downloads, citation and URL generators, video/audio transcriptions, quick-time video, RSS feeds, and research alerts, to name a few) and the librarian can save the time of the user.

When helping faculty select resources, think broadly. In some cases, subscribing to a new database will help replace a textbook. At Florida Gulf Coast University, the Theatre Appreciation course was able to replace all their required textbooks with full online PDFs of play scripts from Drama Online. The database was available for perpetual purchase with a small access fee. The librarian collaborated with the professor of the course to write a persuasive justification for the proposal and the purchase, using the enrollment figures and the total amount of money saved by the students by not having to purchase a textbook.

Another critical consideration when selecting resources is accessibility. Ease of access is very important to both professors and students. Librarians need to think “outside the box” as there are multiple options available to access content. A small technology fee charged to the students for specific online content may still mean considerable savings for the student. For example, the Understanding Visual & Performing Arts course included embedded music clips purchased directly from Naxos Music Library. Each enrolled student was charged $16 for accessing the links within the modules of the course. Initially, the librarian believed this was unnecessary, as the library already subscribed to Naxos and the clips could be created for free via the instructor-generated playlist feature and permanent proxy-linking to the URL. However, this option would have required students to login to the proxy link and the course designers believed the additional charge was worth keeping the clips fully embedded within the course modules. Librarians need to be aware that ease of access is extremely important to the success of an online class and remain flexible and responsive.

Once the resource is selected, librarians can assist with researching and negotiating permissions to placing materials online. For example, the Theatre faculty needed to stream the video, A Jury of Her Peers for their large-enrollment Introduction to Theatre online course. The DVD was not available online, so the librarian contacted the rights holders, Women Make Movies, and the company agreed to allow the technology department to stream the video for a reasonable annual fee if the library purchased a DVD copy for the library. The cost of the annual fee was transferred to the students via a small technology fee, which still meant cost-savings for the student.

Finally, continuous maintenance is crucial. It is important to keep faculty aware that a lot of library-licensed material is just as fluid and impermanent as open source material. Images, e-books, and streamed videos may suddenly disappear from databases as companies lose licensing to content. Sometimes the library is notified, sometimes not. Faculty course designers and the librarians that help them need to have an awareness of this issue and some flexibility with course content if resources disappear and need to be purchased elsewhere or replaced with something similar.

Faculty recommendations to other faculty course designers

At the outset, the developers of this course had little idea of how much work it would take, and how much ongoing commitment would be required even long after the course was launched. To justify that amount of effort, a considerable lifespan should be anticipated for the course––at least 5 or 10 years. Continuous development and maintenance must be part of the plan. Written text is much easier to edit than video lectures, and it is therefore easier to improve a course organically over time if the narrative content is presented as text, and videos, if included, are used as punctual illustration or demonstration. To make development easier, the course was structured from the beginning as a modular design with short lessons.

The choice of which technology to use to present the content is a critical one. At Florida Gulf Coast University, the decision to use Softchalk, (made in consultation with the campus’s E-Learning department) was based on its relative ease of use and its ability to provide in-page interactive features. However, advanced features alone are not the only factor. It is important to evaluate the level of long-term support provided by the software company, the technical robustness of the platform and the needs for ongoing maintenance and hosting services. One reason Softchalk was selected was that it was advertised to be “platform agnostic” in that the lessons, created in Softchalk, could be moved from one learning management system to another without major disruption. That proved to be critical when Blackboard acquired Angel, the system that was in use on campus when the course was initially developed, and the campus then decided to migrate to Canvas.

It is best to keep all images in a master file and that they be saved using Adobe Photoshop or any image editing program that will allow metadata to be stored with the image file. The developers found that the best place to keep track of an image’s provenance and licensing is in the image file itself, in the metadata, though the filename and the image caption used in the course material can also store some information.

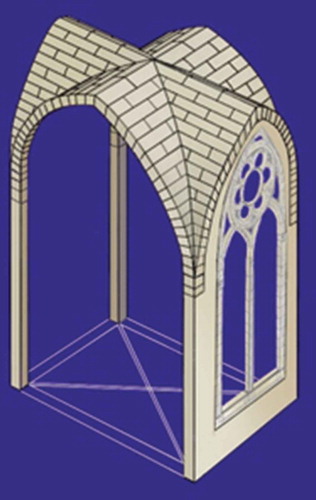

Developers who have some graphic or photography skills should not hesitate to create their own images, charts, and diagrams. Microsoft PowerPoint has surprisingly powerful graphic tools that can be used to create many types of graphic content. Most of the diagrams created for the course (see –) were made with PowerPoint and (in some cases) some additional simple editing in Adobe Photoshop.

Figure 2. Diagram used to explain the difference between double and single curvature in three-dimensional forms, made using Microsoft PowerPoint drawing tools and Adobe Photoshop. Reprinted with permission of Anne-Marie Bouché.

Figure 3. Color wheel diagram, made in Adobe Photoshop. Reprinted with permission of Anne-Marie Bouché.

Figure 4. Diagram of a Gothic bay. This image is a composite made from two separate Public Domain diagrams, one of a Gothic bay, and one of a Gothic tracery window, using Microsoft PowerPoint drawing tools and Adobe Photoshop. Reprinted with permission of Anne-Marie Bouché.

When designing a new course, faculty should consider the practical challenges of implementing best practices for working with visual images and sound in an environment where some students may have physical limitations. For video material, provide closed-captioning or a transcript of the video for students with auditory challenges. Adaptive requirements (such as individually describing each image, or using technology that is compatible with screen readers) can be very labor-intensive or difficult to implement especially if not planned from the outset. The present iteration of the Art Appreciation course has significant limitations in this regard that the developers do not have the resources to address at present.

Utilize the potential of the technology. In the Art Appreciation course, relatively small images (height about 300 pixels) are used in the lessons, but each major image is linked to a larger version (at least 1200 pixels on the long side). Clicking on the small image brings up a larger version for close study. Similarly, the in-text hyperlinked pop-up feature in Softchalk was used to provide definitions for technical terms that students might find unfamiliar. These popups can include images as well.

Finally, good organization and the implementation of best-practice design principles for online courses were essential to the success of the course. All resources should be linked from or accessed through the learning management system. Students in online courses need to access all their materials easily and immediately without having to log in to another resource.

The creation of a team-developed online course continues to provide many challenges, but it also has brought remarkable rewards in the form of stronger bonds between art history and studio faculty, instructional staff, the librarian and the E-Learning professionals who participated. The rewards are a more coherent course, targeted to a specific student body and environment, substantial cost savings to students, and a newfound collective sense of common purpose. In addition to a greatly improved course for students, the collective lessons that everyone learned from the experience have more than justified the labor involved. Everyone’s skills and their understanding of pedagogy, online learning and course-design principles have been enhanced by the collaboration, and these gains are bearing fruit in other courses and endeavors.

References

- Ahern, K. (2017). Teaching biochemistry online at Oregon State University. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 45 (1), 25–30. doi:10.1002/bmb.20979

- American Library Association. (2017). Libraries and the internet toolkit: Open access. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/iftoolkits/litoolkit/openaccess

- Blake, M. R., & Morse, C. (2016). Keeping your options open: A review of open source and free technologies for instructional use in higher education. Reference Services Review, 44 (3), 375–389. doi:10.1108/RSR-05-2016-0033

- Carroll, A. J., Tchangalova, N., & Harrington, E. G. (2016). Flipping one-shot library instruction: Using Canvas and Pecha Kucha for peer teaching. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 104 (2), 125–130. doi:10.3163/1536-5050.104.2.006

- College Art Association. (2015). Code of best practices in fair use for the visual arts. Retrieved from http://www.collegeart.org/programs/caa-fair-use/teaching-tools

- Coltrain, M. (2015). Collaboration: Rethinking roles and strengthening relationships. Community & Junior College Libraries, 21 (1–2), 37–40. doi:10.1080/02763915.2016.1148998

- Coussement, M. A., Johnson, S., & Goodson, L. A. (2016). Developing an e-textbook for the consumer and family sciences classroom: Challenges and rewards. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 108 (2), 64–72. doi:10.14307/JFCS108.2.64

- Decherney, P., & Carpini, M., American Association of University Professors, College Art Association, International Communication Association, Library Copyright Alliance, & Society for Cinema and Media Studies. (2015). In the matter of section 1201 Exemptions to prohibition against circumvention of technological measures protecting copyrighted works (Docket No. 2014-07. U.S. Copyright Office, Library of Congress). Retrieved from https://alair.ala.org/bitstream/handle/11213/1026/02-06-15%20LCA%20Class%201%20Comments%20Regarding%20a%20Proposed%20Exemption%20for%20Audiovisual%20Works.pdf;sequence=1

- Florida Board of Governors. (2016). Performance funding model discussion items November 3, 2016. Retrieved from http://www.flbog.edu/board/office/budget/_doc/performance_funding/Changes_2017-18.pdf

- Gose, B. (2017, April 9). Growing pains begin to emerge in open-textbook movement The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/article/Growing-Pains-Begin-to-Emerge/239701

- Johnston, D., Berg, S. A., Pillon, K., & Williams, M. (2015). Ease of use and usefulness as measures of student experience in a multi-platform e-textbook pilot. Library Hi Tech, 33 (1), 65–82. doi:10.1108/LHT-11-2014-0107

- Kumar, S., Wu, L., & Reynolds, R. (2014). Embedded librarian within an online health informatics graduate research course: A case study. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 33 (1), 51–59. doi:10.1080/02763869.2014.866485

- Organisation For Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2007). Giving knowledge for free: The emergence of open educational resources. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/38654317.pdf