Abstract

Objective: Asthma control and quality of life (QoL) are important disease outcomes for asthma patients. Illness perceptions (cognitive and emotional representations of the illness) and medication beliefs have been found to be important determinants of medication adherence, and subsequently disease control and QoL in adults with asthma. In adolescents, this issue needs further elucidation. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the relationship between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, medication adherence, disease control, and QoL in adolescents with asthma.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, we used baseline data of adolescents with asthma (age 12–18 years) who participated in the ADolescent Adherence Patient Tool (ADAPT) study. Questionnaires were administrated online, and included sociodemographic variables and validated questionnaires measuring self-reported illness perceptions, medication beliefs, medication adherence, disease control, and QoL.

Results: Data of 243 adolescents with asthma were available; age 15.1 ± 2.0 years and 53% females. More than half of these adolescents (62%; n = 151) reported to be non-adherent (Medication Adherence Report Scale ≤23) and 77% (n = 188) had uncontrolled asthma. There was a strong positive correlation between disease control and QoL (r = 0.74). All illness perceptions items were correlated with disease control and QoL, with the strongest correlation between ‘identity’ (symptom perception) and QoL (r=–0.66). Medication adherence was correlated to medication beliefs (r = 0.38), disease control (r = 0.23), and QoL (r = 0.14), whereas medication beliefs were only associated with adherence.

Conclusions: Stimulating positive illness perceptions and medication beliefs might improve adherence, which in turn might lead to improved disease control and better QoL.

Introduction

Well-controlled symptoms are an important outcome for asthma patients. Obtaining sufficient asthma control implies fewer asthma symptoms and exacerbations, decreased use of rescue medication, fewer nighttime awakenings, and improved quality of life (QoL) (Citation1–3). A number of factors are related to uncontrolled asthma, among which are smoking, allergic rhinitis, female gender, and poor adherence (Citation4–7). Medication adherence (i.e. the degree to which the person’s behavior corresponds with the agreed recommendations from a health care provider) is in particular a strong determinant of asthma control, because daily use of controller medications, such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), suppresses the chronic airway inflammation (Citation8, Citation9).

Adherence to medication is complex and affected by multiple factors (Citation10–12). Non-adherence is caused by a combination of unintentional (related to practical barriers) and intentional (related to motivation and beliefs) barriers to take medication (Citation5). The Common Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM) is used to understand patient’s response to their illness. CSM propose that cognitive and emotional illness representations, and medication beliefs (personal medication convictions) directly influence coping strategies (by using feedback mechanisms), thus they can affect intentional non-adherence (health behavior) (Citation13). There are in general five cognitive domains; identity (symptom perception), timeline, consequences, perceived controllability, and the cause.

Adherence rates in asthma patients are generally low, for example, on average 50% of asthma patients are adherent (Citation4). It has been reported that adherence is especially low during adolescence (Citation14). Some barriers for medication adherence, such as forgetfulness, are not specific for adolescents (age 12–18 years), but are more prevalent among them. Furthermore, developmental norms can contribute to adolescent specific barriers for medication adherence, for example, they have a high desire for peer conformity, and they experience feelings of insecurity or invincibility. Moreover, they have unique medication beliefs (e.g. girl aged 14 years said “There are moments I do not feel better from using my inhaler, those times I use nothing”) (Citation15–17). Additionally, a large proportion of adolescents experience a reduction in asthma symptoms (Citation18). This may affect medication adherence, illness perceptions, and medication beliefs.

Factors, such as self-efficacy and perceptions on illness and medication use, have independently been shown to be associated with medication adherence and asthma control in adults and to a lesser extent in adolescents (Citation19, Citation20). However, the exact relationship between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, and adherence (and subsequently disease control and QoL) is unknown, especially in adolescents. Clarification of this relationship may improve the understanding of how disease control can be achieved in this unique patient population, and thereby provide valuable insights for future interventions aimed at improving asthma control, and might highlight factors that can contribute to life-long correct disease management (Citation21). Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the relationship between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, medication adherence, disease control, and QoL in adolescents with asthma.

Materials and methods

Study design, population, and setting

In this cross-sectional exploratory study, we used baseline data of patients who participated in the ADolescent Adherence Patient Tool (ADAPT) study, a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a mobile health intervention on medication adherence. The complete rationale and design of the ADAPT study are described elsewhere (Citation22, Citation23). In short: adolescents aged 12–18 years who filled two or more prescriptions for ICS or a fixed combination of ICS with a long-acting beta-agonist (ICS/LABA) during the previous 12 months (defined as asthma patients) (Citation24) were recruited by mail from community pharmacies belonging to the Utrecht Pharmacy Practice network for Education and Research (UPPER) (Citation25).

After receiving the signed informed consent form by mail, patients had access to the online questionnaire. For patients younger than 16 years, both parents also had to sign informed consent. Baseline data were collected between July 2015 and February 2016. The ADAPT study is approved by the Medical Review Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht (NL50997.041.14) and by the Institutional Review Board of UPPER, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht University. The ADAPT trial is registered at the Dutch Trial Register (NTR5061).

Questionnaire items

The online questionnaire contained sociodemographic questions (e.g. age, gender, education, and sport participation) and questions on adolescents’ health status and asthma medication use. It also contained validated questionnaires on illness perceptions (Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire [Brief-IPQ]) (Citation26), medication beliefs about ICS (Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire-specific [BMQ-specific]) (Citation27), adherence (Medication Adherence Report Scale [MARS-5]) (Citation11), disease control (Control of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma Test [CARAT]) (Citation28, Citation29), and asthma-related QoL (Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire [PAQLQ]) (Citation30, Citation31).

Outcomes measures

The Brief-IPQ was used to assess adolescents’ illness perceptions. This questionnaire consists of eight 11-point Likert scale items divided in three domains (): cognitive representation (illness consequences, duration, personal control, treatment control, and symptom perception), illness comprehensibility (understanding of illness), and emotional representation (emotional representation and illness concern). The ninth item was an open-ended item on the causes of the illness. We excluded this open-ended item from the analysis, because this item was perceived as complicated by young adolescents (Citation32). For the other items, a total score between 0 and 10 was obtained, where a higher score represented more agreement with the item.

Table 1. The median score (response scale 0 to 10; not at all to very much) per item of the Brief-IPQ, with the correlation coefficients with medication beliefs, adherence, disease control, and quality of life.

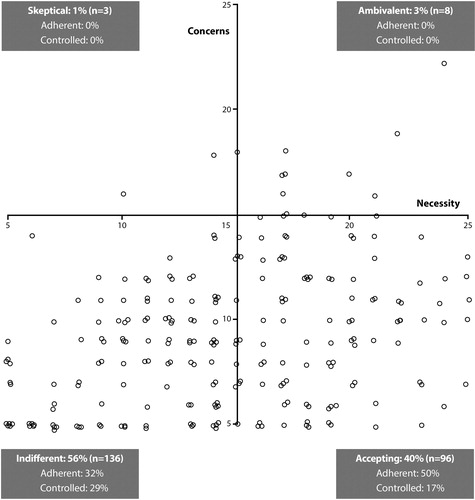

The BMQ-specific was used to assess adolescents beliefs about the necessity and concerns regarding their ICS asthma treatment. This questionnaire consists of 10 questions, divided in two subscales; five items on necessity and five items on concerns. All items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), resulting in a total score between 5 and 25 per subscale. Generally, scores above the scale midpoint (>15) were considered as strong beliefs, resulting in four attitudinal groups: accepting (high necessity, low concerns), ambivalent (high necessity, high concerns), indifferent (low necessity, low concerns), and skeptical (low necessity, high concerns) (Citation33). Moreover, we calculated the necessity-concern differential (i.e. total necessity score minus total concerns score) to get an insight in the necessity beliefs and concerns of an individual patients, and to study the correlations. A positive differential indicated more necessity beliefs than concerns and a negative differential indicated more concerns than necessity beliefs. The BMQ-specific is previously used in adolescents with asthma (Citation8).

Self-reported ICS adherence was assessed using the MARS-5, which consists of five items. All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never), with a total score between 5 (not adherent) and 25 (completely adherent)(Citation11). Additionally, MARS sum scores were dichotomized (adherent versus non-adherent patients) by using a threshold for the sum scores of ≥23 for sufficient adherence, based on previous studies (Citation8, Citation34). The MARS-5 was originally developed for adults; however, previous studies also used MARS as a tool for children and adolescents (Citation35).

Disease control was assessed using the CARAT, which consists of 10 items. A total score between 0 and 30 was obtained, where a score >24 indicates good disease control. The total score can be divided in allergic rhinitis symptoms (item 1–4, score >8 indicate good control) and asthma symptoms (item 5–10, ≥16 indicate good control) (Citation28, Citation29). The CARAT Kids was developed for children age 6 to 12 years, therefore, we used the CARAT.

Asthma-related QoL was assessed using the PAQLQ (Citation31), which consists of 23 items divided in three domains: symptoms, activity limitations, and emotional function. All items were scored using a seven-point Likert scale, resulting in a total mean score (and per domain) between 1 and 7, where seven indicated the highest QoL. The PAQLQ was designed for children aged 7 to 17 years.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. For skewed data, the median with interquartile range (IQR) is shown instead of the mean with standard deviation (SD). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. Additionally, fitting (generalized) linear models were used for secondary analysis, for example, to compare adherent and disease control groups. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test to test for differences in disease control and medication adherence between the four attitudinal groups. These secondary analyses were performed to provide a clear and complete overview of our data and findings. Statistical analysis was performed using R (version 3.4.3). p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 1204 adolescents were invited to participate in the ADAPT study of which 243 adolescents (20.2%) from 54 pharmacies completed the baseline study measurement (on average 4.5 ± 2.7 adolescents per pharmacy). The characteristics of the study population are shown in : half of the patients were male (46.9%), the mean age was 15.1 ± 2.0 years, and most had a Dutch ethnicity (88.5%). A small number of patients (n = 15) reported not having been diagnosed with asthma, however, they collected at least two ICS or ICS/LABA in the previous year, and they reported symptoms which were very likely asthma symptoms, such as shortness of breath (n = 12), allergy symptoms (n = 6), and/or exercise induced symptoms (n = 3). Therefore, we included them in the analysis.

Table 2. Basic characteristics of the study population (N = 243).

Almost half of the adolescents (44.0%) used asthma medication for more than 10 years. Four patients reported that they did not use their inhaler in the previous 6 months, because they (“thought they”) did not need it (n = 3) or forgot to take it (n = 1). All remaining patients used ICS; either monotherapy or ICS in fixed combination with long-acting beta-agonists ().

Illness perceptions

All illness perceptions scores are shown in . Adolescents scored the highest on timeline (i.e. how long do you think your illness will continue?), indicating that they expected a chronic course of their illness. Thereafter, the highest scores were obtained for personal control, treatment control, and coherence (i.e. how well do you feel you understand your illness?). The lowest scores were on the domain emotional representation, suggesting that their asthma did not emotionally affect them.

Beliefs about medication

The mean BMQ-necessity score was 14.4 ± 5.1 (range 5–25) and the mean BMQ-concerns score was 9.2 ± 3.4 (range 5–23). Almost half of the adolescents (42.8%; n = 104) reported high necessity beliefs (above scale midpoint), while only 11 adolescents (4.5%) reporting high concerns. Subsequently, the majority of adolescents had a positive necessity-concern differential (81.9%; n = 199), thus the majority felt medication necessity outweighed medication concerns. Moreover, most adolescents had an indifferent or accepting attitude (95.5%; n = 232; ). There were significant differences between the percentages of controlled (p = .047) and adherent (p = .002) patients in the four attitudinal groups (). That is, half of the adolescents with an accepting attitude and 32% of the indifferent adolescents were adherent, while 29% of the indifferent adolescents and 17% of the accepting adolescents had controlled disease ().

Self-reported medication adherence

The median MARS score was 22.0 (IQR 5), and 37.9% (n = 92) of the adolescents were defined as adherent (MARS sum score ≥23). The percentage of adolescents scoring 1 to 3 (always to sometimes) was the highest at item 1, 3, and 5 (, last column). The median of intentional non-adherence (items 2–5) was five, whereas the median of unintentional non-adherence, that is, forgetting, was three.

Table 3. The median MARS scores per item, ranging from 1 to 5 (always to never).

Self-reported disease control

In total, 22.6% of the adolescents (n = 55) had sufficient disease control (CARAT >24), with more adolescents having control over allergic rhinitis symptoms (38.3%), than over their asthma symptoms (21.8%; ). The mean CARAT total score was 19.6 ± 5.5 (range 0–30), the mean allergic rhinitis score was 7.2 ± 3.1 (range 0–12), and the mean asthma score was 12.4 ± 3.6 (range 0–18). All these means were below the standardized thresholds for sufficient control.

Asthma-related QoL

The mean total PAQLQ score was 5.9 ± 0.9 (range 1.4–7.0), indicating a sufficient to good QoL. The highest mean score was on emotional function 6.5 ± 0.9 (range 1.4–7.0), thereafter on symptoms 5.7 ± 1.1 (range 1.4–7.0), and subsequently on activity limitation 5.4 ± 1.1 (range 1.4–7.0).

Correlation illness perceptions, medication beliefs, adherence, disease control, and QoL

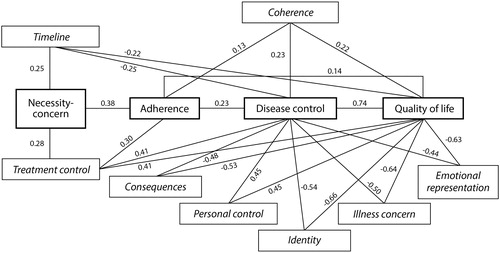

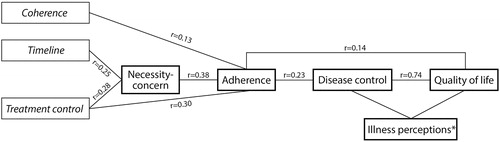

There was a strong correlation (r = 0.74) between disease control and QoL (p < .001). A weak correlation was found between adherence and the necessity-concern differential (r = 0.38; p < .001), thus necessity was positively correlated with adherence (r = 0.28; p < .001), while concerns were negatively correlated (r=–0.14; p = .026). Other weak correlations were found between adherence and disease control (r = 0.23; p < .001), and adherence and QoL (r = 0.14; p = .035). Within the PAQLQ domains, only “symptoms” was correlated with adherence (r = 0.14; p = .027). All correlations are summarized in (and Appendix 1).

Figure 2. Relation between medication beliefs, adherence, illness perceptions, disease control, and QoL in adolescents with asthma (N = 243). r: correlation coefficient. *All items of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire were correlated with disease control and QoL ().

All illness perceptions items were correlated with disease control and QoL (), with the strongest correlations between identity (i.e. symptom perception) and QoL (r=–0.66; p < .001), illness concern and QoL (r =–0.64; p < .001), and emotional representation and QoL (r=–0.63; p < .001). Thus, being more emotionally affected, having more asthma symptoms, and having more concerns are all associated with a decrease in QoL. Duration of the illness (timeline; r = 0.25; p < .001) and treatment control (r = 0.28; p < .001) were both correlated with the necessity-concern differential. Moreover, treatment control (r = 0.30; p < .001) and coherence (i.e. how well do you feel you understand your illness?) were correlated with adherence (r = 0.13; p = .045; ).

Adherent versus non-adherent

Adherent adolescents (MARS ≥23; n = 92) had significant higher scores on the CARAT (median 21) compared with the non-adherent adolescents (n = 151; median 19; p = .006). The asthma control subscale was significantly higher for adherent adolescents (median 14 versus 13; p = .007), while there was no difference on the allergic rhinitis subscale (p = .082). In total, 21% of non-adherent patients had controlled asthma and 75% of adherent patients had uncontrolled asthma. These findings support the weak correlation between adherence and disease control (r = 0.23; ). Moreover, adherent adolescents had a higher necessity-concern differential (median 7.0 versus 3.0; p < .001) and a higher QoL score (median 6.4 versus 6.0; p = .004). They perceived more personal control (median 8 versus 7; p = .009) and more treatment control (median 8 versus 7; p < .001) than non-adherent adolescents. Adherent adolescents also perceived fewer symptoms (identity; median 2 versus 3, p = .003) and were less emotionally affected by their asthma (median 0 versus 1, p = .006) compared with non-adherent adolescents.

Controlled versus uncontrolled

Adolescents with disease control (CARAT >24; n = 55) had a higher QoL (median 6.7) compared with those without disease control (n = 188; median 5.9; p < .001). No differences were found in the medication beliefs (necessity-concern differential; p = .359) and adherence scores (p = .089) of controlled and uncontrolled patients. However, patients with disease control had higher scores on personal control, treatment control, and coherence, while they scored lower on consequences, timeline, identity, emotional representations, and illness concerns (coherence p = .002, others p < .001).

Discussion

The aim was to study the relationship between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, medication adherence, disease control, and QoL in adolescents with asthma. This study showed complex relations between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, medication adherence, disease control, and QoL in adolescents with asthma. Disease control and QoL were highly correlated. Both adherence and illness perceptions were related to these disease outcomes, while medication beliefs were only associated with adherence (). Necessity beliefs were positively associated with adherence, while concerns were negatively associated, which is also previously shown (Citation11, Citation36). Remarkably, adherence was only correlated to the disease outcomes, that is, disease control and QoL. Based on these complex relations (and individual differences), we suggest patient-centered care, such as shared-decision making (Citation37), to improve disease outcomes.

Most illness perceptions were not associated with adherence in this study. This finding seems contradictory to the CSM (Citation13), which proposes that cognitive and emotional representations toward a health threat, result in illness representations and medication beliefs, which affect health behavior (e.g. adherence). Only “treatment control” (i.e. how much do you think your medication can help your illness?) and “coherence perceptions” (i.e. how well do you feel you understand your illness?) were slightly associated with adherence, which is shown before (Citation38). This shows that only one (of the five cognitive CSM domains) is related to adherence that is perceived controllability. The other illness perception domain affecting adherence is illness comprehensibility.

Our findings also suggest that adolescents might not appraise ‘adherence’ as a health outcome (Citation35), instead they might focus on ‘health status’ as an outcome. To illustrate this: illness representations did not emphasize the importance of ICS adherence for adolescents, therefore, they did not improve their adherence (no coping strategy). However illness representations could be related to their health status, however their health status was perceived as acceptable (experience no symptoms), thus no coping strategy is needed (no improvement in adherence).

Adherence and illness perceptions were both associated with disease outcomes, such as disease control and QoL (Citation39). These findings suggest that improving patient’s behavior (increasing adherence) and their illness perceptions (improving cognitive illness representations and illness comprehensibility; ) might improve disease outcomes of adolescents with asthma. However, compared with adults and adolescents with other chronic conditions, adolescents with asthma had already high personal control and coherence (i.e. understanding of their illness), and low concerns and consequences (Citation30). Thus, there was not much to achieve in the illness perceptions of this study population. However, adherence could be increased, as only 38% was defined as adherent. Although, sometimes it might be hard to motivate patients, as asthma care might not always help patients to feel good, as, for example, children can be ashamed to take medication in the classroom. A suggestion to improve adolescent’s behavior and their illness perceptions is to use online influencer (i.e. someone who affects the way other people behave, via use of social media), as, for example, celebrities with chronic conditions may motivate adolescents in using their medication and improve their illness perceptions (Citation40).

More than half of the current adolescent population (56%) had an indifferent attitude (low necessity and low concerns; ), which makes it hard to motivate them. This indifferent attitude might be age-specific, or it might be related to the long-term medication use, as, for example, in our study, 44% used asthma medication for more than 10 years. The indifference could also be related to the high control perceptions (personal and treatment control) and low symptom perceptions (identity), that is, they were feeling fine. However, only 23% of the adolescents had indeed sufficient disease control. This discrepancy between perceived and reported disease control, suggests that it is important to improve adolescent’s insights into their disease control. For example, by comparing their perceived asthma control with pulmonary function measurements, such as spirometry, the PAQLQ data suggest that especially activity limitation may be improved. These results suggest that adolescents accept some activity limitation, whereas activity limitation can be absent when asthma is controlled. Improved insights into their less controlled asthma may increase treatment necessity beliefs and treatment control perceptions (and thereby may subsequently support adherence and disease control). However, more research is needed to find effective ways to improve adolescent’s insights into their disease control.

This study emphasized the complex relationship between medication adherence and disease control, because most adolescents in this study were non-adherent and had uncontrolled asthma; however, 21% of the non-adherent adolescents had controlled asthma. This contradictory finding might be caused by the mechanism of action of ICS. Patients are advised to use daily controller medication to suppress their chronic airway inflammation. However, when they sometimes forget to use ICS, they will not directly experience wheezing or other asthma symptoms. The transition of asthma symptoms (i.e. decrease during adolescence) (Citation18) might also explain why some non-adherent patients still had disease control. These patients may be over treated. On the other hand, 75% of adherent patients had uncontrolled asthma. These patients require special attention, because other factors may contribute to uncontrolled asthma, such as wrong inhaler techniques, seasonal effects, too low dose of ICS, or uncontrolled allergic rhinitis.

Weak correlations were found in this study, suggesting complex relations. We suggest that “feedback mechanisms” might play a role here. For example, patients are adherent until a certain level of disease control, thereafter they become more negligent with their asthma medication (as they experience fewer asthma symptoms). To illustrate; the percentage of adherent patients in the indifferent group (32%) was lower than in the accepting group (50%), while the percentage of controlled patients (29%) was higher in the indifferent group than in the accepting group (17%) (). Such mechanisms may make it hard to obtain complete disease control, because patients can become more indifferent toward their medication when they experience fewer asthma symptoms. A ceiling effect might also contribute to the weak correlations.

This cross sectional study used validated questionnaires to measure study outcomes, which has some limitations. First of all, there might be a desirability bias. Suggestions to overcome this bias are to use direct measurements for adherence and disease control, such as refill records and spirometry measurements. However, cognitive factors can only be measured by using self-report. Second, the participants in this study participated in a clinical trial, suggesting that they were highly motivated (participation bias). This might partly explain why almost half of the adolescents (43%) reported high necessity beliefs and 82% had a positive necessity-concern differential. The latter percentage is high compared with other adolescent patient populations, as, for example, 62% of adolescents with ADHD had a positive necessity-concern differential and 11% reported high necessity beliefs (Citation32). However, there are always variations between patients, suggesting that there is ample room to discuss the specific illness perceptions and medication beliefs of individual adolescents. Third, there might be a risk for multiple comparisons; however, our focus was on exploring the relationship between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, medication adherence, disease control, and QoL in adolescents with asthma. Additionally, we conducted descriptive analysis, to provide more information on the study population, therefore, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. Finally, the relationships found in this study might be different for specific patient population, for example, patients with a low socioeconomic status. Moreover, the results might be different for different inhaler devices. Therefore, more research is needed to find associations in specific patient populations and for different inhaler devices.

In adolescents with asthma, the relationship between illness perceptions, medication beliefs, adherence, disease control, and QoL are complex. There was a strong positive correlation between disease control and QoL. All illness perceptions items were correlated with disease control and QoL, and medication adherence was correlated to medication beliefs, disease control, and QoL. Based on these findings, we suggest that stimulating positive illness perceptions and medication beliefs might improve adherence, which in turn lead to improved disease control and better QoL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their input.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- SundbergR, PalmqvistM, TunsäterA, TorénK. Health-related quality of life in young adults with asthma. Respir Med 2009;103:1580–1585. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2009.04.023.

- RheeH, BelyeaMJ, ElwardKS. Patterns of asthma control perception in adolescents: associations with psychosocial functioning. J Asthma 2008;45:600–606. doi:10.1080/02770900802126974.

- LozierMJ, ZahranHS, BaileyCM. Assessing health outcomes, quality of life, and healthcare use among school-age children with asthma. J Asthma 2018;56:42–49. doi:10.1080/02770903.2018.1426767.

- BurkhartPV, SabatéE. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. J Nurs Scholarsh 2003;35:207

- Haughney J, Price D, Kaplan A, Chrystyn H, Horne R, May N, Moffat M, Versnel J, Shanahan ER, Hillyer EV, et al. Achieving asthma control in practice: Understanding the reasons for poor control. Resp Med 2008;102:1681–1693. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2008.08.003.

- Laforest L, Van Ganse E, Devouassoux G, Bousquet J, Chretin S, Bauguil G, Pacheco Y, Chamba G. Influence of patients’ characteristics and disease management on asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:1404–1410. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.007.

- Bednarek A, Bodajko-Grochowska A, Bartkowiak-Emeryk M, Klepacz R, Ciołkowski J, Zarzycka D, Emeryk A. Demographic and medical factors affecting short-term changes in subjective evaluation of asthma control in adolescents. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2018;35:259–266. doi:10.5114/ada.2018.76221.

- KosterES, PhilbertD, WintersNA, BouvyML. Adolescents’ inhaled corticosteroid adherence: the importance of treatment perceptions and medication knowledge. J Asthma 2015;52:431–436. doi:10.3109/02770903.2014.979366.

- Jentzsch NS, Silva GCG, Mendes GMS, Brand PLP, Camargos P. Treatment adherence and level of control in moderate persistent asthma in children and adolescents treated with fluticasone and salmeterol. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2017;95:69–75.

- HorneR. Compliance, adherence, and concordance: implications for asthma treatment. Chest 2006;130:65S–72S. doi:10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.65S.

- HorneR, WeinmanJ. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health 2002;17:17–32. doi:10.1080/08870440290001502.

- LycettH, WildmanE, RaebelEM, SherlockJ-P, KennyT, ChanAHY. Treatment perceptions in patients with asthma: Synthesis of factors influencing adherence. Respir Med 2018;141:180–189. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.032.

- LeventhalH, NerenzD, SteeleD, Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: BaumA, TaylorSE, SingerJE, eds. Handbook of psychology and health. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates 1984. 219–252.

- McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Klein RB, Fritz GK. Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: reasoning, responsibility, and behavior. J Pediatr Psychol 2003;28:323–333. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsg022.

- KosterES, PhilbertD, de VriesTW, van DijkL, BouvyML. “I just forget to take it”: asthma self-management needs and preferences in adolescents. J Asthma 2015;52:831–837. doi:10.3109/02770903.2015.1020388.

- KosterES, HeerdinkER, de VriesTW, BouvyML. Attitudes towards medication use in a general population of adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 2014;173:483–488. doi:10.1007/s00431-013-2211-4.

- Sleath B, Carpenter DM, Walsh KE, Davis SA, Hayes Watson C, Lee C, Loughlin CE, Garcia N, Reuland DS, Tudor G. Factors associated with adolescent and caregiver reported problems in using asthma medications. J Asthma 2018;56:451–457. doi:10.1080/02770903.2018.1466312.

- FuchsO, BahmerT, RabeKF, von MutiusE. Asthma transition from childhood into adulthood. Lancet Resp Med 2017;5:224–234. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30187-4.

- RheeH, WicksMN, DolgoffJ, LoveT, HarringtonD. Cognitive factors predict medication adherence and asthma control in urban adolescents with asthma. Patient Prefer Adher 2018;12:929–937. doi:10.2147/PPA.S162925.

- Kaptein AA, Hughes BM, Scharloo M, Fischer MJ, Snoei L, Weinman J, Rabe KF. Illness perceptions about asthma are determinants of outcome. J Asthma 2008;45:459–464. doi:10.1080/02770900802040043.

- NormansellR, KewKM, StovoldE. Interventions to improve adherence to inhaled steroids for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD012226.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012226.pub2.

- Kosse RC, Bouvy ML, de Vries TW, Kaptein AA, Geers HC, van Dijk L, Koster ES. mHealth intervention to support asthma self-management in adolescents: the ADAPT study. Patient Prefer Adher 2017;11:571–577. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124615.

- KosseRC, BouvyML, de VriesTW, KosterES. Effect of a mHealth intervention on adherence in adolescents with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Med 2019;149:45–51. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2019.02.009.

- Mulder B, Groenhof F, Kocabas LI, Bos HJ, De Vries TW, Hak E, Schuiling-Veninga C. Identification of Dutch children diagnosed with atopic diseases using prescription data: a validation study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72:73–82. doi:10.1007/s00228-015-1940-x.

- KosterES, BlomL, PhilbertD, RumpW, BouvyML. The Utrecht pharmacy practice network for education and research: a network of community and hospital pharmacies in the Netherlands. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:669–674. doi:10.1007/s11096-014-9954-5.

- BroadbentE, PetrieKJ, MainJ, WeinmanJ. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosomat Res 2006;60:631–637. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020.

- HorneR, WeinmanJ, HankinsM. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999;14:1–24. doi:10.1080/08870449908407311.

- Nogueira-Silva L, Martins SV, Cruz-Correia R, Azevedo LF, Morais-Almeida M, Bugalho-Almeida A, Vaz M, Costa-Pereira A, Fonseca JA. Control of allergic rhinitis and asthma test–a formal approach to the development of a measuring tool. Respir Res 2009;10:52. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-10-52.

- Fonseca JA, Nogueira-Silva L, Morais-Almeida M, Azevedo L, Sa-Sousa A, Branco-Ferreira M, Fernandes L, Bousquet J. Validation of a questionnaire (CARAT10) to assess rhinitis and asthma in patients with asthma. Allergy 2010;65:1042–1048. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02310.x.

- RaatH, BuevingHJ, de JongsteJC, GrolMH, JuniperEF, van der WoudenJC. Responsiveness, longitudinal-and cross-sectional construct validity of the Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) in Dutch children with asthma. Qual Life Res 2005;14:265–272. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-6551-4.

- JuniperEF, GuyattGH, FeenyDH, FerriePJ, GriffithLE, TownsendM. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Qual Life Res 1996;5:35–46. doi:10.1007/BF00435967.

- KosseRC, BouvyML, PhilbertD, de VriesTW, KosterES. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication use in adolescents: the patient’s perspective. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:619–625. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.027.

- Menckeberg TT, Bouvy ML, Bracke M, Kaptein AA, Leufkens HG, Raaijmakers JA, Horne R. Beliefs about medicines predict refill adherence to inhaled corticosteroids. J Psychosomat Res 2008;64:47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.016.

- SjölanderM, ErikssonM, GladerE-L. The association between patients’ beliefs about medicines and adherence to drug treatment after stroke: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003551. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003551.

- AlsousM, HamdanI, SalehM, McElnayJ, HorneR, MasriA. Predictors of nonadherence in children and adolescents with epilepsy: a multimethod assessment approach. Epilepsy Behav 2018;85:205–211. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.06.022.

- HorneR, ChapmanSCE, ParhamR, FreemantleN, ForbesA, CooperV. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e80633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080633.

- TaylorYJ, TappH, ShadeLE, LiuT-L, MowrerJL, DulinMF. Impact of shared decision making on asthma quality of life and asthma control among children. J Asthma 2018;55:675–683. doi:10.1080/02770903.2017.1362423.

- LawGU, TolgyesiCS, HowardRA. Illness beliefs and self-management in children and young people with chronic illness: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev 2014;8:362–380. doi:10.1080/17437199.2012.747123.

- PetrieKJ, JagoLA, DevcichDA. The role of illness perceptions in patients with medical conditions. Curr Opin Psychiatr 2007;20:163–167. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328014a871.

- HoffmanSJ, TanC. Following celebrities’ medical advice: meta-narrative analysis. Br Med J 2013;347:f7151. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7151.