Abstract

Objective: Asthma is a multifaceted disease, and severe asthma is likely to be persistent. Patients with severe asthma have the greatest burden and require more healthcare resources than those with mild-to-moderate asthma. The majority with asthma can be managed in primary care, while some patients with severe asthma warrant referral for expert advice regarding management. In adolescence, this involves a transition from pediatric to adult healthcare. This study aimed to explore how young adults with severe asthma experienced the transition process.

Methods: Young adults with severe asthma were recruited from an ongoing Swedish population-based cohort. Qualitative data were obtained through individual interviews (n = 16, mean age 23.4 years), and the transcribed data were analyzed with systematic text condensation.

Results: Four categories emerged based on the young adults’ experiences: “I have to take responsibility”, “A need of being involved”, “Feeling left out of the system”, and “Lack of engagement”. The young adults felt they had to take more responsibility, did not know where to turn, and experienced fewer follow-ups in adult healthcare. Further, they wanted healthcare providers to involve them in self-management during adolescence, and in general, they felt that their asthma received insufficient support from healthcare providers.

Conclusions: Based on how the young adults with severe asthma experienced the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, it is suggested that healthcare providers together with each patient prepare, plan, and communicate in the transition process for continued care in line with transition guidelines.

Introduction

Asthma is a multifaceted disease, and certain forms of asthma may persist; severe asthma is more likely to, while mild asthma often goes into remission (Citation1–3). The prevalence of severe asthma in the total asthma population varies between 5 and 10% (Citation4,Citation5), and during adolescence it is estimated at 6.7% (Citation6). Patients with severe asthma have the greatest burden and require more healthcare resources than those with mild to moderate asthma (Citation7,Citation8). The approach to asthma management is described in international and national guidelines (Citation9,Citation10). The majority of patients with asthma can usually be managed in primary care, while some patients with severe asthma warrant referral for expert advice regarding management of severe asthma (Citation7,Citation9). In adolescence, this involves a transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, a transition performed when adolescents are around 18 years old; views vary on whether the transition should occur at a set age or during a particular period (Citation11). In a healthcare setting, the classic definition of transition is “the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centered to adult-oriented healthcare systems” (Citation12). This transition is just one of many during adolescence (Citation13,Citation14). A wider set includes educational, personal, family, and social transitions. Risk and vulnerability encompass many dimensions of the transitions from adolescence to adulthood (Citation15).

Even though formal transition guidelines exist with recommendations of system infrastructure, and education and training for clinicians in partnership with families and youth to support a safe and effective transition process (Citation15), previous literature has shown that the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare is often haphazard, e.g., when the transition has not been planned appropriately (Citation11,Citation16–18). Poor transition planning may also place a vulnerable group at greater risk for a continuation of poor health outcomes throughout their lifespan (Citation14). One of few previous studies investigating consequences of asthma during the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare found that patients with mild/moderate asthma were managed equally effectively in primary and specialist care (Citation19). However, subjects with severe asthma were not included in the randomization since they were classified as need of continued treatment at an adult asthma clinic. It is important that patients with severe asthma are given appropriate advice and medical support to reduce the risk for further asthma exacerbations and potentially life-threatening attacks (Citation20).

Most qualitative studies of asthma to date have focused on the family transition, i.e., the transfer of responsibility (Citation21–23). However, to improve the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, healthcare providers need to know how young adults approach their transitional care. Moreover, as severe asthma imposes long-term debilitating burdens, it should be considered different from milder disease (Citation24). The aim of this qualitative study was therefore to explore how young adults with severe asthma experienced the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare.

Methods

Study design

This study has a qualitative descriptive approach using individual semi-structured interviews, with participants recruited from the ongoing population-based birth cohort BAMSE (Barn/Child, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiology) (Citation25,Citation26). This birth cohort includes 4,089 children born between 1994 and 1996, followed since birth with almost yearly follow-ups. When children were approximately 2 months of age, data about background factors such as allergic heredity were obtained. Follow-up questionnaires were distributed when the children were 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 years, to collect information about symptoms related to asthma and other allergic diseases, and treatment of asthma. The ongoing 24-year follow-up of the entire cohort, including questionnaire and clinical data, started in autumn 2016 and will be completed in 2019.

Recruitment

With the aim of including young adults with persistent and severe asthma, who have experience of living with asthma in adolescence and in young adulthood, a purposive sampling was used (Citation27). Participants were recruited in two steps based on information from the follow-ups at both 16 and 24 years, i.e., two different periods when the criteria were fulfilled.

At 16 years: classified as having asthma, i.e., fulfilled at least two of the following three criteria: symptoms of wheeze and/or breathing difficulties, asthma medicine occasionally or regularly in the preceding 12 months, and/or ever doctor’s diagnosis of asthma (n = 437) () (Citation6). In addition, dispensed high daily doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), at least 800 µg budesonide or equivalent (≥500 µg fluticasone), or fixed combinations of ICS and long-acting β2-agonists (LABA), in accordance with international and national guidelines (Citation7,Citation9,Citation10), in the last 18 months (n = 104).

Table 1. Recruitment, fulfilled criteria and study population.

At 24 years: current respiratory symptoms such as difficulty breathing, tightness of the chest, or wheezy/raspy breathing, at least 4–12 episodes in the last 12 months.

In total, 30 individuals fulfilled these criteria according to data reported in the questionnaires between the start of the 24-year follow-up and February 2018. As an invitation to participate, a research nurse called the young adults fulfilling the above criteria, informed about the study, and asked if the first author (M.Ö.) could contact them, so as to avoid making them feel compelled to participate. M.Ö. thereafter contacted those who had consented. In total, 14 young adults were excluded due to: no contact with healthcare before and after 18 years of age (n = 4), not wanting to participate (n = 3), or not being reachable at less than or equal three different time points (n = 7). Resulting in a total of 16 participants included in the final analyses.

Data collection

Data were obtained through individual semi-structured interviews, a method chosen to gain rich and varied data to cover the aim of the study (Citation27,Citation28). All interviews were performed during 2018 by M.Ö., who is a registered nurse with clinical experience of working with children and adolescents with asthma. The interviews were conducted in Swedish and were held in person (n = 12) or by telephone (n = 4, participants # 4, 12, 13, 15), by telephone due to geographical barriers for the participant. The interviews were audio recorded, and ranged in length from 17 to 39 min, all of good quality of dialog.

The interview guide was developed based on joint discussions between the authors about factors of importance for the interview, using previous knowledge as professionals with clinical experience of asthma management (Citation29). A preliminary interview guide was formulated and pilot-tested twice. Slightly revised, the completed interview guide, supported by previous literature, centered on exploring young adults’ experiences when transitioning from pediatric to adult healthcare, with a focus on expectations, needs, and responsibilities (Citation30). The interview guide is presented in the supplement material. The sequencing of the open-ended questions was not the same for every participant, as it depended on the individual’s responses. Supplementary follow-up questions were asked if necessary for clarification purposes.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (2017/395-32). At the beginning of the interviews, the participants got verbal and written information on how the material would be treated, the aim of the study and that their participation was voluntary, and they gave written informed consent.

Data analysis

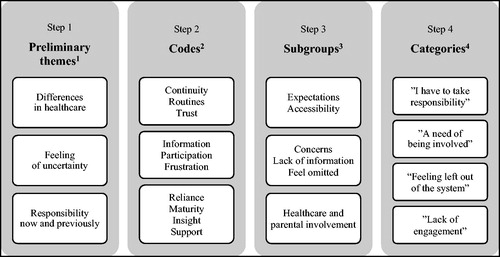

Recordings were transcribed verbatim, and the transcribed data were analyzed using systematic text condensation (STC) in accordance with Malterud (Citation31). STC is a descriptive approach, presenting the experiences of the participants, as expressed by the participants themselves. The goal of STC is to present vital examples from people’s everyday experiences. STC contains intersubjectivity, reflexivity, feasibility, and a responsible level of methodological rigor (Citation31). The analysis was performed in four steps:

Step 1, getting an overall impression of the text, identifying preliminary themes.

Step 2, identifying meaning units in the preliminary themes, labeling with codes.

Step 3, sorting the codes by meaning, and further into subgroups.

Step 4, synthesizing the essence of each meaning from condensation to descriptions and concepts of each category (Citation31).

To achieve credibility in the analytical process, all steps were first conducted by M.Ö. and then by the authors M.J. and I.K. separately. The three authors discussed their results jointly, until no disagreement arose (Citation32). The quotes were professionally translated into the English language. shows the analysis process.

Figure 1. The analysis process in systematic text condensation, steps 1–4: preliminary themes, codes, subgroups, and categories. 1. Step 1, getting an overall impression of the text, identifying preliminary themes. 2. Step 2, identifying meaning units in the preliminary themes, labeling with codes. 3. Step 3, sorting the codes by meaning, and further into subgroups. 4. Step 4, synthesizing the essence of each meaning from condensation to descriptions and concepts of each category.

Results

The participants (n = 16) had a mean age of 23.4 years (range 22.4–24.5), and both genders were represented (). The majority was immunoglobulin E (IgE)-sensitized to inhalant and/or food allergens (n = 15), and 14 had multiple allergic diseases, such as asthma in combination with eczema and/or rhinitis.

Table 2. Characteristics of interviewed participants (n = 16) based on reported BAMSE questionnaire data.

With regard to the participants’ experiences of the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, important aspects were found. In total, four categories emerged during the analysis process: “I have to take responsibility,” “A need of being involved,” “Feeling left out of the system,” and “Lack of engagement.”

I have to take responsibility

The participants expressed that they had to take more responsibility after the transition to adult healthcare. When enrolled at a pediatric asthma/allergy clinic, the participants were used to automatically receiving calls for visits etc., and got support from their parents. The awareness of a difference when in adult healthcare was evident.

When in adult healthcare, participants felt that they needed to be mature enough to take on full responsibility; it was up to the individuals to handle everything, and to keep in touch with healthcare. When a participant visited the same healthcare setting, i.e., primary care organization, from child-to-adulthood, the experienced difference in responsibility before and after the transition was not so distinct, even if their parents no longer came along.

“Now I’m not classed as a kid anymore, so now I need to see a new doctor to get medication prescribed and then I have to show them that I need this. So I have to ask for this myself, because it’s not the same ‘they come to me’ principle, it’s the ‘I come to them’ principle.” (# 3)

Another participant said:

“Just because you turn 18 and become an adult on paper, that doesn’t mean that you are fully educated and mature enough to take on all the responsibility that it implies.” (# 8)

The young adults’ responsibilities included requesting care and taking their own asthma seriously. Moreover, in adult healthcare the participants expressed that they had to be a bit pushy and persuasive in relation to healthcare providers, and make it clear they knew what they wanted.

“When you’re grown up, you need to feel that you take charge of it, because by that time you probably know that you have allergic disease.” (# 1)

Another participant said:

“You have to, you know, want to treat your asthma or want to get better, otherwise I think it’s hard to get the care you need, but you can get the care you need if you want to.” (# 6)

A need of being involved

During childhood, information had been given to the participants’ parents. However, the participants wanted healthcare providers to involve them in self-management of asthma during adolescence, not just their parents. Some participants stated that they had not been aware that a transition from pediatric to adult healthcare was going to occur, and they wished that the healthcare providers had involved them in the process.

“Mum kept track of everything, but it would have been even better if I had sort of kept track of things too. And that’s the reason why I partly don’t remember all that much, because you didn’t really understand any of it back then, you just got the medicine that you got and you tried it.” (# 10)

Another participant said:

“It’s good if the centre provides information that we are not responsible for you anymore and we will be referring you on, so that it’s not just a final check-up and you leave and think that you’ll be going back there again.” (# 6)

Moreover, the participants wanted a joint preparation for adult healthcare that was allowed to take time. As young adults, they would be more prepared for new routines in a way that could help them understand their asthma management, including actions and procedures.

“The transfer should be gradual, you can do it may be over a slightly longer period, that you can start providing information and then at eighteen that it’s ‘okay, you need to move on now.’ That you give it a bit more time, because if you do it about a month before you turn eighteen and say that ‘now you need to move on.’ That causes a bit of a problem, because you need to find someone who knows stuff, someone you can trust.” (# 3)

Feeling left out of the system

Since information about the transition had been lacking, the participants did not know where to turn for, e.g., a renewed prescription, and what the next step was. When no transition occurred, they felt that they ended up outside of the system, and not knowing the healthcare providers in adult healthcare caused concern and feelings of being sent randomly anywhere or to just anyone.

“When I didn’t have any asthma medication left, I thought, but where do I get my medicines now?” (# 2)

Another participant said:

“It was really easy when I had a paediatrician. I just went there or called and they’d say that I could come in and then I could just barge in there and… So that was really easy. I got to know him. Now it’s like okay, where should I go, what do I do, who do I call and so on. So that part is a bit more difficult now.” (# 4)

The participants experienced fewer follow-ups or none at all compared with earlier, whether or not a transition had occurred. In the pediatric asthma/allergy clinic, the participants were familiar with their healthcare providers. They had gotten to know each other, but after the transition this was no longer the case, and visits became impersonal.

“No, I haven’t been to any asthma check-ups since, I’d say at least since 2014. So that’s only because I haven’t gotten any notices to the same extent and the fact is that four years ago, I went from being a kid to being a grownup and I think it might have to do with that.” (# 3)

Another participant said:

“At the allergy centre, I think I did the spirometry fairly often because they followed up on the asthma pretty well when you were there anyway. They don’t do that as much now, I don’t feel. That’s a shame, but you can remind them. You got to know everyone who worked there, they knew all the kids who came there as well.” (# 9)

Lack of engagement

In adult healthcare, the visits tended to come to nothing, partly because of the impersonal contact, but also because they were often focused on a renewed prescription and no discussion or evaluation about the treatment; therefore, they did not feel significant. Moreover, the healthcare providers’ reliability was questioned, when prescriptions were renewed without a physical visit in more than a year.

“I think it’s strange that healthcare continues to prescribe medications without knowing if they are correct and without having met me in many years.” (# 16)

The participants expressed a feeling that their asthma in general received insufficient support from healthcare providers, compared with other chronic diseases. They felt that asthma was underestimated, and this feeling increased over time. They assumed this might be because many people have asthma, and they became one in the crowd.

“Just because asthma and allergy are not directly life-threatening, it feels like it doesn’t have the same impact, so you’re not seen in the same way.” (# 8)

Once they got in touch with adult healthcare and were in the system, they expected the healthcare providers to support them in understanding the severity of their asthma, and they expected to be listened to. However, the participants experienced a lack of engagement from their healthcare providers, while also feeling that asthma was something that affected their way of life during their most formative years and had a big impact on them.

“Asthma is something that affects your way of life, in a way, during your most important formative years. It has quite a big impact.” (# 8)

Discussion

This qualitative study describes how young adults with severe asthma experienced the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare. Results gave important knowledge of how the young adults perceived taking over responsibility, felt left out of the system, and experienced fewer follow-ups in adult healthcare. This suggests a link where healthcare providers together with each patient prepare, plan, and communicate in the transition process for continued care in line with transition guidelines.

In this study, the participants experienced that they had to take more responsibility for their asthma, and needed to be more persuasive in adult healthcare than they were used to. Taking more responsibility for the disease as a young adult is natural, and a recent review showed that providers of adult healthcare encourage young adults to take responsibility for their own health (Citation33). However, when growing into adulthood, the young person needs support to practice disease self-management. Healthcare providers should engage to build relationships that empower the young adults to develop skills and knowledge of disease management (Citation34). Education regarding asthma and support to self-management usually occurs at the time of diagnosis, which in asthma often comes during childhood. Therefore, education is usually directed at the parents (Citation17). It is preferable for adolescents to gradually start seeing their healthcare provider on their own; this could increase confidence in discussing symptoms, as well as knowledge of what asthma is and how their medications work (Citation17,Citation35). In this study, the young adults said that they wanted to be more prepared for adult healthcare, get personal information about the transition, and let it take time, so they could become mature enough to manage their disease. Chronological age cannot be used as the sole determinant for when the transition should start; the timing of preparing the adolescent, and when and how to transfer treatment responsibilities to the patient are also important factors to consider (Citation11,Citation33,Citation36).

Our findings show a risk of being lost to follow-up in the transition between pediatric and adult healthcare, as also seen in a previous study (Citation11). Associations between being lost to follow-up and risk factors for deterioration among participants with severe asthma during the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare are sparsely studied. We aim to investigate this further as well as the importance of healthcare setting, in a coming study by combining data on healthcare consumption from national registers, self-reported data, and objective markers of asthma control. There is variation between healthcare systems in the delivery of asthma care: by primary healthcare providers in some countries, and by specialists in others (Citation9). Moreover, recent studies showed that there is variation in quality of asthma care, adherence to guidelines, and services across asthma specialists and primary care clinicians (Citation37–40). Further, a recent study showed that Swedish adults with severe asthma had few regular visits with both primary and specialist care (Citation41). In this study, we could only speculate, but the impact of systematic factors, such as the delivery and quality of asthma care, as well as few regular visits may influence the transition process.

The participants in this study expressed a feeling of impersonal contact in adult healthcare. In the pediatric asthma/allergy clinic, they were used to seeing the same doctor over many years. In adult healthcare, by contrast, patients often have to go to different doctors to meet their needs of asthma care, which can be a barrier to a successful transition (Citation36). Speck et al. (Citation42) reported that young adults had the impression that their asthma care provider was more likely to prescribe medication than to have a conversation about asthma management. This was evident in our results as well; the participants experienced a lack of engagement on the part of their healthcare providers. This was also shown in a recent systematic review of qualitative studies exploring people’s experiences of living with severe asthma (Citation8). People with severe asthma strived to achieve a greater level of personal control over their condition, but their efforts received insufficient support from their healthcare providers. They also described a similar situation for adults living with other chronic illnesses, but mentioned important differences, e.g., severe asthma was considered an “invisible” condition not easily observable to others.

Guidance for clinicians on the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare exists (Citation15). However, a recently published qualitative meta-synthesis of adolescents’ and young adults’ experiences of the transition from pediatric to adult hospital care showed that the transfer experience is more than a change from one place to another (Citation30). The transfer experience is interwoven into a pattern of developmental, health-illness, situational, and organizational transition issues as well. The authors also found comparisons like the young adults feelings of not belonging, and their need of being acknowledged as competent contributors during the transition process, across somatic chronic diagnoses, supporting the main findings in the present study. To assess whether transition guidelines are used and have a long-term impact on care, further research is needed (Citation43). Healthcare providers’ adherence to transition guidelines appeared to be inadequate in our study. Some of the young adults did not know a transition should occur when they were around 18 years of age. System barriers, such as not receiving information on the transition, have been identified in earlier studies, highlighting the need for better communication between pediatric and adult healthcare during the transition process (Citation33,Citation44). The basics of transition, common to all diseases and conditions, are to prepare young adults in advance for moving to adult healthcare, to prepare adult services to receive the young adults, and to listen to the young adults’ own views of what they want from the transition (Citation13,Citation15). Teamwork between the pediatric and adult systems is the key to improving coordination and communication in the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare (Citation15). In the ideal situation, team-based care in both the pediatric and adult settings could increase the chances of success.

Strengths and limitations

Several strengths and limitations to our study should be acknowledged. The number of well-defined participants with severe asthma was deemed sufficient, and the purposive sampling has a strength in the different perspectives on the phenomena investigated (Citation27). We had the gender aspect in mind in recruitment to get an even distribution, to disclose potential differences in perceptions since gender differences have been revealed, e.g., girls are less likely to achieve asthma control than boys (Citation6,Citation45). However, sociodemographic variables were not taken in account; these could be associated with different experiences of the transition process.

One circumstance that could have affected the results in a negative way is that some of the young adults, as is common in that age period, moved from their hometown due to studies in another city, and therefore experienced a lack of continuity and regularity in healthcare. However, according to national guidelines (Citation10), adolescents with severe asthma should be transferred to adult healthcare.

It is well-known that the results of qualitative studies cannot be generalized, however can be transferred to other settings and groups (Citation46). We believe the present study adds depth and new knowledge, and can hopefully lead to reflection among healthcare providers on how to handle the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare for patients with severe asthma.

Conclusions

Based on the participants’ experiences of the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, young adults with severe asthma felt they had to take more responsibility, did not know where to turn, and experienced fewer follow-ups in adult healthcare. Therefore, healthcare providers should increase their awareness of the difficulties that young adults with severe asthma face in the transition process. It is suggested that healthcare providers together with each patient prepare, plan, and communicate in the progressive transition process for continued care in line with transition guidelines.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Thanks to the participants in the BAMSE cohort and all the staff involved in the study through the years. A special thanks to Marie Carp (Centre for Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Stockholm County Council, Stockholm, Sweden), research nurse at the BAMSE clinic.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fuchs O, Bahmer T, Rabe KF, von Mutius E. Asthma transition from childhood into adulthood. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:224–234. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30187-4.

- Sears MR. Predicting asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.048.

- Garden FL, Simpson JM, Mellis CM, Marks GB. Change in the manifestations of asthma and asthma-related traits in childhood: a latent transition analysis. Eur Respir J 2016;47:499–509. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00284-2015.

- Hekking PP, Wener RR, Amelink M, Zwinderman AH, Bouvy ML, Bel EH. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.042.

- von Bulow A, Kriegbaum M, Backer V, Porsbjerg C. The prevalence of severe asthma and low asthma control among Danish adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.05.005.

- Odling M, Andersson N, Ekstrom S, Melen E, Bergstrom A, Kull I. Characterization of asthma in the adolescent population. Allergy 2018;73:1744–1746. doi: 10.1111/all.13469.

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014;43:343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013.

- Eassey D, Reddel HK, Foster JM, Kirkpatrick S, Locock L, Ryan K, Smith L. “…I've said I wish I was dead, you'd be better off without me”: a systematic review of people's experiences of living with severe asthma. J Asthma 2018;56:311–322. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1452034.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Available from http://ginasthma.org/. [last accessed 7 August 2018]

- The Swedish Paediatric Society. Available from: http://www.barnallergisektionen.se/. [last accessed 7 February 2019]

- Couriel J. Asthma in adolescence. Paediatr Respir Rev 2003;4:47–54.

- Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, Jorissen TW, Okinow NA, Orr DP, Slap GB. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570–576. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(93)90143-D.

- Viner RM. Transition of care from paediatric to adult services: one part of improved health services for adolescents. Arch Dis Childhood 2008;93:160–163. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.103721.

- Gibson-Scipio W, Gourdin D, Krouse HJ. Asthma self-management goals, beliefs and behaviors of urban African American adolescents prior to transitioning to adult health care. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:e53–e61. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.06.012.

- White PH, Cooley WC. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20182587. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2587.

- Bitsko MJ, Everhart RS, Rubin BK. The adolescent with asthma. Paediatr Respir Rev 2014;15:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2013.07.003.

- Towns SJ, van Asperen PP. Diagnosis and management of asthma in adolescents. Clin Respir J 2009;3:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2009.00130.x.

- Scal P, Davern M, Ireland M, Park K. Transition to adulthood: delays and unmet needs among adolescents and young adults with asthma. J Pediatr 2008;152:471–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.10.004.

- Bergstrom SE, Sundell K, Hedlin G. Adolescents with asthma: consequences of transition from paediatric to adult healthcare. Respir Med 2010;104:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.09.021.

- Pike KC, Levy ML, Moreiras J, Fleming L. Managing problematic severe asthma: beyond the guidelines. Arch Dis Childhood 2017;103:392–397. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311368.

- Buford TA. Transfer of asthma management responsibility from parents to their school-age children. J Pediatr Nurs 2004;19:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2003.09.002.

- Gibson-Scipio W, Krouse HJ. Goals, beliefs, and concerns of urban caregivers of middle and older adolescents with asthma. J Asthma 2013;50:242–249. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.759964.

- Meah A, Callery P, Milnes L, Rogers S. Thinking 'taller': sharing responsibility in the everyday lives of children with asthma. J Clin Nurs 2009;19:1952–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02767.x.

- Foster JM, McDonald VM, Guo M, Reddel HK. “I have lost in every facet of my life”: the hidden burden of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1700765. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00765-2017.

- Ballardini N, Bergström A, Wahlgren C-F, van Hage M, Hallner E, Kull I, Melen E, Anto JM, Bousquet J, Wickman M. IgE antibodies in relation to prevalence and multimorbidity of eczema, asthma, and rhinitis from birth to adolescence. Allergy 2016;71:342–349. doi: 10.1111/all.12798.

- Thacher JD, Schultz ES, Hallberg J, Hellberg U, Kull I, Thunqvist P, Pershagen G, Gustafsson PM, Melen E, Bergstrom A. Tobacco smoke exposure in early life and adolescence in relation to lung function. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1702111 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02111-2017.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet (London, England) 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 2015;26:1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444.

- Kallio H, Pietila AM, Johnson M, Kangasniemi M. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031.

- Fegran L, Hall EO, Uhrenfeldt L, Aagaard H, Ludvigsen MS. Adolescents' and young adults' transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: a qualitative metasynthesis. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.001.

- Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health 2012;40:795–805. doi: 10.1177/1403494812465030.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Zhou H, Roberts P, Dhaliwal S, Della P. Transitioning adolescent and young adults with chronic disease and/or disabilities from paediatric to adult care services - an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:3113–3130. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13326.

- The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Adapting to adolescence. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:419.

- van Staa A, Sattoe JN. Young adults' experiences and satisfaction with the transfer of care. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.008.

- Pai ALH, Ostendorf HM. Treatment adherence in adolescents and young adults affected by chronic illness during the health care transition from pediatric to adult health care: a literature review. Children Health Care 2011;40:16–33. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2011.537934.

- Akinbami LJ, Salo PM, Cloutier MM, Wilkerson JC, Elward KS, Mazurek JM, Williams S, Zeldin DC. Primary care clinician adherence with asthma guidelines: the National Asthma Survey of Physicians. J Asthma 2019;1–13. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1579831.

- Cloutier MM, Salo PM, Akinbami LJ, Cohn RD, Wilkerson JC, Diette GB, Williams S, Elward KS, Mazurek JM, Spinner JR, et al. Clinician agreement, self-efficacy, and adherence with the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:886–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.01.018.

- Rege S, Kavati A, Ortiz B, Mosnaim G, Cabana MD, Murphy K, Aparasu RR. Documentation of asthma control and severity in pediatrics: analysis of national office-based visits. J Asthma 2019;1–12. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1554069.

- Warman KL, Silver EJ. Are inner-city children with asthma receiving specialty care as recommended in national asthma guidelines? J Asthma 2018;55:517–524. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1350966.

- Larsson K, Ställberg B, Lisspers K, Telg G, Johansson G, Thuresson M, Janson C. Prevalence and management of severe asthma in primary care: an observational cohort study in Sweden (PACEHR). Respir Res 2018;19:12. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0719-x.

- Speck AL, Nelson B, Jefferson SO, Baptist AP. Young, African American adults with asthma: what matters to them? Ann Allergy 2014;112:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.10.016.

- Sharma N, O’Hare K, Antonelli RC, Sawicki GS. Transition care: future directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.007.

- Huang JS, Gottschalk M, Pian M, Dillon L, Barajas D, Bartholomew LK. Transition to adult care: systematic assessment of adolescents with chronic illnesses and their medical teams. J Pediatr 2011;159:994–998.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.05.038.

- Dahlen E, Wettermark B, Bergstrom A, Jonsson EW, Almqvist C, Kull I. Medicine use and disease control among adolescents with asthma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1993-x.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004.