Abstract

Objective

We compared the pharmacokinetic exposure following a single subcutaneous dose of benralizumab 30 mg using either autoinjectors (AI) or accessorized prefilled syringes (APFS). APFS and AI functionality and reliability for at-home benralizumab delivery have been demonstrated in the GREGALE and GRECO studies, respectively.

Methods

In the open-label AMES study (NCT02968914), 180 healthy adult men and women were randomized to one of two device (AI or APFS) and three injection site (upper arm, abdomen, or thigh) combinations. Randomization was stratified by weight (<70 kg, 70–84.9 kg, and ≥85 kg). Blood eosinophil counts were measured on Days 1, 8, 29, and 57.

Results

Benralizumab pharmacokinetic exposure was similar between AI and APFS. Geometric mean ratios (AI/APFS) (90% CI) were 92.8% (87.4–98.6) and 94.5% (88.2–101.2) for two area under the concentration‒time curve measurements (AUClast and AUCinf). Benralizumab exposure was approximately 15–30% greater for thigh vs. abdomen or upper arm administration. Exposure was slightly greater for APFS vs. AI regardless of injection site or weight class. These differences were unlikely to be clinically relevant, as eosinophil depletion was achieved consistently with both devices at all injection sites. No device malfunctions were reported. No new or unexpected safety findings were observed.

Conclusion

Benralizumab pharmacokinetic exposure was similar between AI and APFS, with consistent blood eosinophil count depletion observed with both devices. These results support benralizumab administration with either AI or APFS, providing patients and physicians increased choice, flexibility, and convenience for potential at-home delivery.

Introduction

Benralizumab is a humanized interleukin-5 receptor alpha–directed cytolytic monoclonal antibody currently approved in the European Union, United States, and other countries for the treatment of severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma (Citation1–3). Benralizumab 30 mg is currently administered subcutaneously (SC) every 8 weeks (first three doses every 4 weeks) in a clinical setting (Citation2,Citation3).

It is important to evaluate the feasibility of the self-administration of biologics, such as benralizumab, specifically in an at-home setting. Patients and health care professionals prefer self-administration of biologics because of the health-related quality of life and economic benefits (Citation4–7). At-home self-administration can substantially reduce the burden associated with specialty clinic visits, especially for patients who currently travel long distances for treatment. The option of self-administering treatment allows physicians to treat more patients with severe asthma by freeing up capacity at specialty clinics.

Two injection device options include autoinjectors (AI) and accessorized prefilled syringes (APFS). It is important to provide patients device options to support their satisfaction and adherence. Several studies for patients with arthritis and ulcerative colitis have indicated that patients prefer AI over APFS for self-administration of their medications, with reasons including ease of use, satisfaction, and acceptability (Citation8,Citation9). In a report on self-administration of migraine medication, patients found both devices equally easy to use and were comfortable using either (Citation10).

In two open-label Phase III studies, GREGALE and GRECO, APFS and AI, respectively, used to administer benralizumab in an at-home setting were demonstrated to be functional and reliable, with similarly acceptable performance compared with administration with these devices in a clinical setting (Citation11,Citation12). In GREGALE and GRECO, at-home benralizumab administration was completed successfully by ≥98% and approximately 97% of patients and caregivers, respectively (Citation11,Citation12). Malfunction rates were very low in both studies.

Benralizumab is approved for APFS administration with reported pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of an absorption half-life of approximately 3.6 days and an elimination half-life of approximately 15 days (Citation2). We report findings from the open-label Phase I AMES study (NCT02968914). The aim of this study was to compare PK exposure following a single dose of benralizumab 30 mg SC administered via AI or APFS by health care professionals at clinical sites.

Methods

Study design

AMES was a multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel group, Phase I study performed at two sites in Berlin, Germany, and London, United Kingdom. The study included a screening period of ≤28 days; a single treatment period during which volunteers received benralizumab at the study center on Day 1 and returned for follow up on Days 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 15, 19, and 43; and an end-of-treatment visit on Day 57.

Eligible male or female healthy volunteers were aged 18–55 years, weighed 55.0–100.0 kg, and had body mass index 18.0–29.9 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included history of clinically significant diseases or disorders that could affect volunteer safety, study results, or study participation; history of anaphylaxis with any biologic; and helminthic parasitic infection diagnosed within 24 weeks before enrollment that either had not been treated or did not respond to standard-of-care therapy. The attending physician determined helminthic parasitic infection based on local standards of care through their general practitioner records.

Before any volunteers were enrolled, the clinical study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees and respective regulatory authorities in the United Kingdom and Germany. All volunteers provided written informed consent at enrollment. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice and the AstraZeneca policy on Bioethics and Human Biological Samples.

Procedures

Volunteers were stratified by body weight (55.0–69.9 kg, 70.0–84.9 kg, and 85.0–100.0 kg) and randomized 1:1:1:1:1:1 based on device (AI or APFS) and injection site (upper arm, abdomen, or thigh) (). Each individual device/injection site/weight group included 10 volunteers, with a total of 60 volunteers for each injection site and body weight category and 90 volunteers for each device category. Volunteers received a single SC dose of benralizumab 30 mg (manufactured by AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) on Day 1 as a 30 mg/mL solution in either AI or APFS. Blood samples were obtained to measure serum benralizumab concentrations on Days 1 (pre-dose), 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 15, 29, 43, and 57. Benralizumab blood concentrations were measured by PPD Bioanalytical Lab (Richmond, VA, USA) via a validated assay (Citation13). Blood eosinophil counts were measured on Days 1, 8, 29, and 57.

Table 1. Study design and volunteer randomization.

Study objectives

The primary study objective was to compare PK exposure following a single SC injection of benralizumab administered via either AI or APFS. The following primary PK parameters were evaluated: area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to time of last quantifiable concentration (AUClast), area under the concentration–time curve from zero to infinity (AUCinf), and maximum observed concentration (Cmax). Secondary study objectives were 1) to compare PK exposure of benralizumab administered via either AI or APFS at various injection sites and to volunteers in different body weight categories, 2) safety and tolerability, and 3) immunogenicity of benralizumab. Secondary PK parameters evaluated were time when maximum concentration is observed (Tmax), terminal half-life (t1/2), apparent extravascular clearance (CL/F), and apparent volume of distribution based on the terminal phase (Vz/F).

Statistical methods

For the primary and secondary objectives, a total of 162 volunteers (81 per device group) was required to achieve 80% power and a 90% 2-sided confidence interval (CI) for geometric mean ratios of AUC and Cmax being within a limit of 0.8–1.25 (inclusive). The calculation was based on two 1-sided tests at a 5% alpha level under the assumption of maximum 50% coefficient of variance PK variability for AUC and Cmax. Enrollment of 180 volunteers was assumed adequate to evaluate the primary and secondary study objectives assuming a 10% dropout rate.

For the primary PK analysis, an analysis of variance model was employed on the log-transformed AUClast, AUCinf, and Cmax separately, with fixed effects for device, injection site, and body weight category. Estimated differences and 2-sided 90% CIs on the log scale were back-transformed to obtain geometric mean ratios of AI to APFS and corresponding 90% CIs. For the secondary PK analyses, PK parameters were summarized by device, injection sites, and body weight ranges. The analysis of variance model used for the primary PK analyses was employed for the secondary PK analyses including the addition of fixed effects for device × injection site, with a nonparametric analysis performed for Tmax. Summary data were presented in tabular format, and categorical data were summarized by the number and percentage of volunteers in each category. Continuous data were summarized by descriptive statistics, including n, mean, standard deviation, median, and range.

PK analysis was performed for the PK analysis set, which consisted of all volunteers who received benralizumab, whose samples were not affected by factors such as protocol violations, and who had at least one post-dose quantifiable serum PK observation. The safety analysis set consisted of all volunteers who received at least one dose of benralizumab. All statistical analyses were performed via SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). PK analyses were performed via Phoenix WinNonlin version 6.3 (Certara, Princeton, NJ, USA).

Results

Volunteers

A total of 180 healthy volunteers (90 AI and 90 APFS) participated in and completed the study. Two protocol deviations were reported during the study following benralizumab administration; one volunteer had received a new chemical entity 87 days before benralizumab administration, and one volunteer’s surgical sterilization was considered reversible. Neither deviation influenced interpretation of results or excluded volunteers from the PK and safety analyses. Demographics were similar between groups receiving benralizumab via AI and APFS. Most volunteers were white (91%, n = 163) and male (82%, n = 147) ().

Table 2. Volunteer demographics.

PK results by device

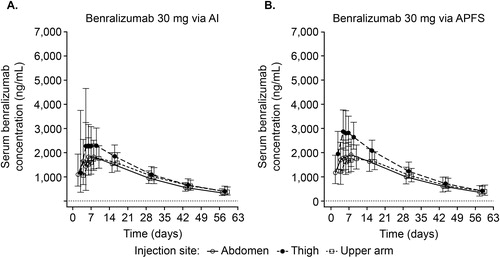

Following benralizumab 30 mg SC administration, changes in mean serum concentrations were similar between AI and APFS, initially increasing with a median Tmax of approximately 5 days, followed by an exponential decrease after reaching Cmax (). At Day 57 (end of treatment), serum concentrations were above the lower limit of quantification (3.86 ng/mL) for all volunteers.

Figure 1. Geometric mean benralizumab serum concentration over time across injection sites and devices (PK analysis set). AI, autoinjector; APFS, accessorized prefilled syringe; PK, pharmacokinetic. Vertical lines represent ± standard deviation of the geometric mean. Dashed horizontal line represents the lower limit of quantification (3.86 ng/mL).

Mean PK parameter values were comparable between AI and APFS and are summarized in . Benralizumab PK exposure was similar between devices, with AI/APFS geometric mean ratios of 92.8%, 94.5%, and 92.3% for AUClast, AUCinf, and Cmax, respectively (). All 90% CIs were within the 80–125% reference range for each parameter (). Tmax, t1/2, CL/F, and Vz/F were also similar between devices. Similar decreases in blood eosinophil counts with benralizumab were observed for both devices, with median (minimum–maximum) values at baseline for AI (135 cells/µL [20–700]) and APFS (135 cells/μL [30–510]) decreasing to 0 cells/µL (0–20 [AI] and 0–30 [APFS]) for both devices by Day 8 and remaining at 0 cells/µL on Days 29 (0–10 [AI] and 0–20 [APFS]) and 57 (0–20 [AI] and 0–20 [APFS]).

Table 3. Statistical comparison of key benralizumab PK parameters between devices (PK analysis set).

PK results by injection site and body weight

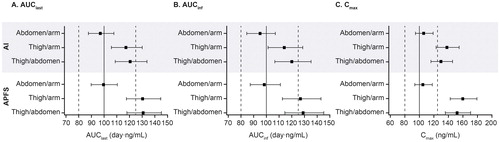

Similar exposure was observed between abdomen and upper arm administrations. Benralizumab PK exposure was 15–30% greater for the thigh injection site compared with abdomen and upper arm injection sites (). For example, geometric mean ratios for thigh/upper arm for AUClast, AUCinf, and Cmax were 117.3%, 114.1%, and 138.0%, respectively, for AI and 130.4%, 126.8%, and 159.9%, respectively, for APFS (). For comparisons of the thigh to other injection sites, the upper limit of 90% CIs of the geometric mean ratios was greater than the reference range of 125%, and the lower limit of 90% CIs was greater than 100% ().

Table 4. Statistical comparison of key benralizumab PK parameters between injection sites and devices (PK analysis set).

When stratified by injection site (), exposure was slightly greater with APFS vs. AI, with geometric mean ratios (AI/APFS) for AUClast, AUCinf, and Cmax, respectively, of 97.0%, 99.0%, and 96.6% (upper arm); 94.6%, 95.7%, and 97.7% (abdomen); and 87.2%, 89.1%, and 83.4% (thigh) (). All 90% CIs of the geometric mean ratio (AI/APFS) stratified by injection site were within the 80–125% reference range for each parameter for upper arm and abdomen and slightly less than 80% for thigh ().

Figure 2. Forest plot of pairwise comparison of benralizumab PK parameters across injection sites and devices (PK analysis set). AI, autoinjector; APFS, accessorized prefilled syringe; AUCinf, area under the concentration–time curve from zero to infinity; AUClast, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to time of last quantifiable concentration; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, maximum observed concentration; PK, pharmacokinetic. The forest plot represents 90% CIs of injection site ratios by device for PK parameters. The PK analysis set included all volunteers who received benralizumab, whose samples were not affected by factors such as protocol violations, and who had at least one post-dose quantifiable serum PK observation.

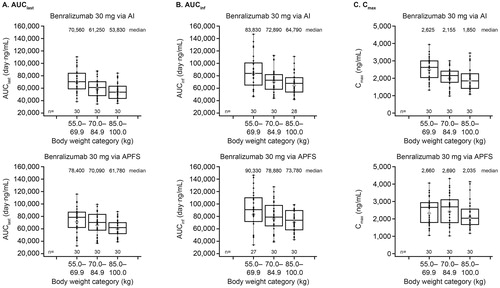

Geometric mean AUClast, AUCinf, and Cmax were slightly greater for APFS compared with AI for all weight categories (). Exposures were greater for volunteers in the lowest weight category compared with those in the other weight categories, with the exception of Cmax with the APFS. The t1/2 values demonstrated no clear differences across weight categories between devices.

Figure 3. Box plot of benralizumab PK parameters by body weight category and device (PK analysis set). AI, autoinjector; APFS, accessorized prefilled syringe; AUCinf, area under the concentration–time curve from zero to infinity; AUClast, area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to time of last quantifiable concentration; Cmax, maximum observed concentration; PK, pharmacokinetic. Top and bottom whiskers represent maximum and minimum values, respectively. Top and bottom boxes represent upper and lower quartiles, respectively. Bars within the boxes represent medians, and symbols within the boxes represent geometric means. Dots represent individual values. The PK analysis set included all volunteers who received benralizumab, whose samples were not affected by factors such as protocol violations, and who had at least one post-dose quantifiable serum PK observation.

Safety

A total of 96 (53%) volunteers reported at least one adverse event (AE), with similar percentages of AEs reported between devices (). There were no deaths, serious AEs, or AEs leading to discontinuations reported during the study (). The most common AEs were nasopharyngitis (17% [n = 31]), headache (11% [n = 19]), and oropharyngeal pain (10% [n = 18]). Most reported AEs were mild (34% [n = 61]) to moderate (19% [n = 34]), with one severe AE (decreased appetite) for the AI group. Potentially drug-related AEs were reported by 13% (n = 12) and 17% (n = 15) of volunteers in the AI and APFS groups, respectively. Drug-related AEs reported by ≥2 volunteers for a given device were oropharyngeal pain (total: 4% [n = 8], AI: 3% [n = 3], APFS: 6% [n = 5]), headache (total: 3% [n = 6], AI: 3% [n = 3], APFS: 3% [n = 3]), acne (total: 2% [n = 4], AI: 2% [n = 2], APFS: 2% [n = 2]), cough (total: 2% [n = 3], AI: 1% [n = 1], APFS: 2% [n = 2]), and abdominal pain (total: 2% [n = 3], AI: 1% [n = 1], APFS: 2% [n = 2]). One volunteer experienced an injection-site reaction (AI group, injection-site hypersensitivity of mild intensity), which was potentially related to the study drug. Anti-drug antibody (ADA) prevalence (ADA positive at any time point in the study) was low for volunteers receiving benralizumab via the AI (2.2% [n = 2]) and APFS (6.7% [n = 6]). No device malfunctions were reported.

Table 5. AEs (on-treatment, safety analysis set).

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence that benralizumab PK exposure is similar with both AI and APFS, regardless of injection site or body weight. In addition, complete blood eosinophil count depletion was also achieved with both devices. These results support the option of using either the APFS or the AI.

Benralizumab induces direct, rapid, and nearly complete depletion of eosinophils via enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (Citation1,Citation14). In three Phase III studies, benralizumab every 8 weeks was demonstrated to significantly (p ≤ 0.02) reduce asthma exacerbations, improve lung function, and decrease oral corticosteroid use for patients with severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma (Citation15–17). Currently, benralizumab is recommended to be administered by a health care professional in a clinical setting (Citation2). To investigate potential alternative at-home administration options, two open-label Phase III studies (GREGALE and GRECO) were performed (Citation11,Citation12). In GREGALE, 116 adult patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma received benralizumab 30 mg SC every 4 weeks via APFS in five separate administrations: three were in a clinical setting, and two were at home (Citation11). Successful at-home benralizumab administrations were completed by ≥98% of patients or caregivers. Only one of 573 APFS malfunctioned. User error occurred twice, resulting in two unsuccessful at-home administrations (Citation11). Injection-site reactions, which occurred for 4% (n = 5) of patients, were mild to moderate in intensity and resolved in 1–15 days (Citation11). In GRECO, 121 adult patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma received five separate administrations of benralizumab 30 mg SC via AI every 4 weeks (three in a clinical setting and two at home) (Citation12). Approximately 97% of at-home administrations were successful when completed by patients or caregivers (Citation12). Of 595 AIs used throughout the study, one malfunctioned and eight injections were unsuccessful because of user error (Citation12). Injection-site reactions, reported by eight patients (6.6%), were all mild and resolved in 1–8 days (Citation12).

In GREGALE and GRECO, both of which evaluated device functionality, patients were prompted to report any issues with any aspect of injection (Citation11,Citation12). These studies determined that AI and APFS were functional and reliable for self-administration of benralizumab in an at-home setting with similarly acceptable performance compared with administration by a health care professional in a clinical setting (Citation11,Citation12). However, a side-by-side comparison of these two devices was needed to determine if they have similar PK properties, supporting the use of either device for self-administration.

In this current study, we determined that PK exposure of a single dose of benralizumab 30 mg SC was similar between AI and APFS administration for healthy volunteers, with all 90% CIs within the reference range of 80–125% for the AI/APFS comparisons of AUC (AUClast and AUCinf) and Cmax. Slightly greater exposures with APFS compared with AI were observed regardless of injection site or weight class. As injection site flexibility may be relevant for patients because of factors such as personal preference and potential sensitivity for specific injection sites, we compared benralizumab PK exposure between three injection sites: upper arm, abdomen, and thigh. We determined that benralizumab PK exposure was similar between injection sites with either device, although overall exposures were greater for thigh injections than for other injection sites (Citation10,Citation18). Because consistent eosinophil depletion was observed following administration at all injection sites with both devices, the greater exposure for thigh injections was unlikely to be clinically relevant. When benralizumab PK exposure was stratified by weight groups, no clear differences were observed between devices. Consistent with a previous PK modeling study (Citation19), benralizumab PK exposure was greater for volunteers in the lowest weight group compared with those in the other weight groups. Benralizumab was well-tolerated with low prevalence of ADAs, consistent with previous studies (Citation15–17).

Self-administration of biologics for the treatment of asthma is an important goal to provide patients greater convenience and potentially reduce costs. With benralizumab, self-administration every 8 weeks could decrease patient burden and potentially improve adherence as compared with administration at a treatment center. Self-administration, particularly in the home setting, would be especially relevant for patients who do not have flexible schedules or who need to travel long distances to treatment centers. At-home self-administration can allow physicians to treat more patients with severe asthma by increasing capacity at specialty clinics.

As this study was performed for healthy volunteers, and each volunteer received a single injection with only one device, one limitation was that patient preference for the AI or APFS device was not explored. Patient preference for AI over APFS has been reported for self-administration of arthritis medication, while no device preference was described in a migraine study (Citation8–10). Future studies should be performed to determine device preference for patients receiving benralizumab.

Conclusion

In summary, these benralizumab PK exposure findings indicate that both AI and APFS have similar PK profiles, regardless of injection site or body weight. These results, along with previous functionality studies, support the use of either device for self-administration of benralizumab. Giving patients the opportunity to determine how, when, and where they receive their asthma treatments could provide important benefits for their treatment outcomes and overall experiences.

Acknowledgements

We thank the investigators, health care providers, research staff, and volunteers who participated in the AMES study. We thank Bing Wang, formerly of MedImmune LLC, for his contributions to the AMES study design and protocol, and Mark Odorisio (AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD) and Melanie Sundsbo Hughes (AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD) for their clinical operations leadership in this study. In addition, we thank Yen Lin Chia, of AstraZeneca, for her critical review of the manuscript. Editorial support was provided by Alan Saltzman, PhD, CMPP, of JK Associates, Inc., and Michael A. Nissen, ELS, of AstraZeneca. This support was funded by AstraZeneca. Some of these data were presented in a poster at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) Congress on February 22–25, 2019, in San Francisco, CA, USA. The poster abstract was published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (Martin U, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143[2 Suppl]:AB95; https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(18)32033-5/abstract).

Data availability

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be requested in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data-sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagroup-dt.pharmacm.com/DT/Home.

Declaration of interest

Ubaldo J. Martin, Peter Barker, Milton J. Axley, Magnus Aurivillius, Li Yan, and Lorin Roskos are employees of AstraZeneca. Rainard Fuhr and Pablo Forte are employees of Parexel, which conducted this study under contract with AstraZeneca.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kolbeck R, Kozhich A, Koike M, Peng L, Andersson CK, Damschroder MM, Reed JL, Woods R, Dall’acqua WW, Stephens GL, et al. MEDI-563, a humanized anti–IL-5 receptor alpha mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1344–53. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.004.

- Benralizumab (FASENRA™) prescribing information; 2017 [accessed 2019 Apr 29]. https://www.azpicentral.com/fasenra/fasenra.pdf#page=1.

- Benralizumab (FASENRA™) summary of product characteristics; 2018 [accessed 2019 Apr 29]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fasenra-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Tetteh EK, Morris S, Titcheneker-Hooker N. Discrete-choice modelling of patient preferences for modes of drug administration. Health Econ Rev. 2017;7:26. doi:10.1186/s13561-017-0162-6.

- Stoner KL, Harder H, Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA. Intravenous versus subcutaneous drug administration. Which do patients prefer? A systematic review. Patient. 2015;8:145. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0075-y.

- Scalone L, Sarzi-Puttini P, Sinigaglia L, Montecucco C, Giacomelli R, Lapadula G, Olivieri I, Giardino AM, Cortesi PA, Mantovani LG, et al. Patients’, physicians’, nurses’, and pharmacists’ preferences on the characteristics of biologic agents used in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2153–68. doi:10.2147/PPA.S168458.

- Huynh TK, Ostergaard A, Egsmose C, Madsen OR. Preferences of patients and health professionals for route and frequency of administration of biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:93–9. doi:10.2147/PPA.S55156.

- Demary W, Schwenke H, Rockwitz K, Kastner P, Liebhaber A, Schoo U, Hübner G, Pichlmeier U, Guimbal-Schmolck C, Müller-Ladner U. Subcutaneously administered methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis, by prefilled syringes versus prefilled pens: patient preference and comparison of the self-injection experience. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1061–71. doi:10.2147/PPA.S64111.

- Vermeire S, D’heygere F, Nakad A, Franchimont D, Fontaine F, Louis E, Van Hootegem P, Dewit O, Lambrecht G, Strubbe B, et al. Preference for a prefilled syringe or an auto-injection device for delivering golimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized crossover study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1193–202. doi:10.2147/PPA.S154181.

- Stauffer VL, Sides R, Lanteri-Minet M, Kielbasa W, Jin Y, Selzler KJ, Tepper SJ. Comparison between prefilled syringe and autoinjector devices on patient-reported experiences and pharmacokinetics in galcanezumab studies. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1785–95. doi:10.2147/PPA.S170636.

- Ferguson GT, Mansur AH, Jacobs JS, Hebert J, Clawson C, Tao W, Wu Y, Goldman M. Assessment of an accessorized pre-filled syringe for home-administered benralizumab in severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:63–72. doi:10.2147/JAA.S157762.

- Barker P, Ferguson GT, Cole J, Aurivillius M, Roussel P, Martin U. Single-use autoinjector functionality and reliability for at-home benralizumab administration: GRECO trial results. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:AB69.

- Yan L, Wang B, Chia YL, Roskos LK. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of benralizumab in adult and adolescent patients with asthma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58:943–58. doi:10.1007/s40262-019-00738-4.

- Pham TH, Damera G, Newbold P, Ranade K. Reductions in eosinophil biomarkers by benralizumab in patients with asthma. Respir Med. 2016;111:21–9. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2016.01.003.

- Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, Papi A, Weinstein SF, Barker P, Sproule S, Gilmartin G, Aurivillius M, Werkström V, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2115–27. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1.

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, Korn S, Ohta K, Lommatzsch M, Ferguson GT, Busse WW, Barker P, Sproule S, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2128–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31322-8.

- Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, Bourdin A, Lugogo NL, Kuna P, Barker P, Sproule S, Ponnarambil S, Goldman M, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2448–58. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1703501.

- Zeraatkari K, Karimi M, Shahrzad MK, Changiz T. Comparison of heparin subcutaneous injection in thigh, arm, & abdomen. Can J Anesth. 2005;52:A109. doi:10.1007/BF03023147.

- Wang B, Yan L, Yao Z, Roskos LK. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of benralizumab in healthy volunteers and patients with asthma. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6:249–57. doi:10.1002/psp4.12160.