Abstract

Objective

This real-world observational study compared medication adherence and persistence among patients with asthma receiving the once-daily inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist (ICS/LABA) fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (FF/VI) versus the twice-daily ICS/LABAs budesonide/formoterol (B/F) and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FP/SAL).

Methods

This retrospective cohort study conducted using IQVIATM Health Plan Claims Data included patients with asthma ≥18 years of age initiating ICS/LABA therapy with FF/VI, B/F, or FP/SAL between January 1, 2014 and June 30, 2016 (index date). Patients had ≥12 months and ≥3 months of continuous eligibility pre- and post-index date, respectively. Patients receiving FF/VI were separately matched 1:1 with patients receiving B/F or FP/SAL using propensity score matching (PSM) and multivariable regression to balance baseline covariates between cohorts. The primary endpoint was medication adherence, measured by proportion of days covered (PDC). Secondary endpoints included proportion of patients achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 and persistence with index medication, measured by time to discontinuation (>45-day gap in therapy).

Results

After PSM, 3,764 and 3,339 patients receiving FF/VI were matched with patients receiving B/F or FP/SAL, respectively. Mean PDC was significantly higher for FF/VI versus B/F (0.453 vs 0.345; adjusted p < 0.001) and FP/SAL (0.446 vs 0.341; adjusted p < 0.001). The proportion of patients achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 or PDC ≥ 0.8, and treatment persistence were significantly higher for FF/VI versus B/F and FP/SAL (all p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In this real-world study, patients initiating FF/VI had better adherence and lower risk of discontinuing treatment versus B/F or FP/SAL, suggesting that once-daily ICS/LABA treatment might improve adherence and persistence compared with twice-daily alternatives.

Introduction

Guidelines developed by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) recommend inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for long-term treatment of patients with persistent asthma (Citation1,Citation2). In patients whose symptoms are not controlled by ICS alone, guidelines recommend the addition of a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) to the treatment regimen (Citation1,Citation2). ICS/LABA fixed-dose combination (FDC) therapies combine these controller medications into a single inhaler, which can lead to improved asthma control compared with ICS and LABA treatments administered with separate inhalers (Citation3). Several ICS/LABA FDCs are available for patients with asthma, including twice-daily budesonide/formoterol (B/F) and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FP/SAL), and once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (FF/VI) (Citation4–6). In the USA, FF/VI is administered via a dry powder inhaler (DPI) (Citation4), B/F is administered via a pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) (Citation5), and FP/SAL is available as both a DPI and a pMDI (Citation6,Citation7).

Treatment guidelines highlight the importance of adherence to medication in achieving asthma control (Citation1,Citation2). However, adherence to long-term controller medications among patients with asthma is often low in the real-world setting (Citation8–10). Uncontrolled asthma is often associated with poor medication adherence or suboptimal therapy resulting in an increased risk of exacerbations and higher associated medical costs (Citation9,Citation11–14). Adherence to medication can be influenced by aspects of the treatment regimen, such as the number of individually administered agents, dosing frequency, and ease of administration (Citation15,Citation16). Previous studies have shown significant improvements in adherence to treatment with once-daily compared with twice-daily controller medications (Citation17–23). Furthermore, a recent study reported greater adherence and a lower risk of discontinuation in patients initiating FF/VI compared with patients initiating B/F (Citation24).

However, real-world data on treatment patterns and adherence with ICS/LABAs is currently limited. This study aimed to evaluate real-world adherence, as measured by proportion of days covered (PDC), and persistence among patients who initiated treatment with FF/VI compared with those who initiated B/F or FP/SAL.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

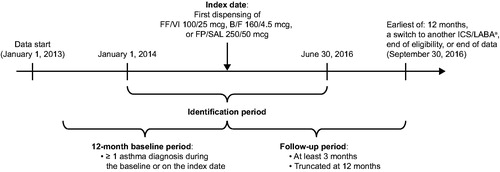

This was a retrospective cohort study using medical and pharmacy claims data and enrollment information from IQVIA™ Health Plan Claims Data between January 1, 2013 and September 30, 2016 ().

Figure 1. Study design. aIncluded patients who switched to another ICS/LABA FDC or to a different dose of the index ICS/LABA. B/F, budesonide/formoterol; FF/VI, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol; FDC, fixed-dose combination; FP/SAL, fluticasone propionate; ICS/LABA, inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist.

Patients were included in the study population if they had ≥1 prescription fill for FF/VI (100/25 mcg), B/F (160/4.5 mcg), or FP/SAL (250/50 mcg) during the patient identification period (January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2016). Of note, only the DPI form of FP/SAL was used in this study. The baseline period was defined as the 12-month period prior to the date of first dispensing of FF/VI, B/F, or FP/SAL (index date), and the follow-up period was defined as the period from the index date to the earliest of 12 months, switch to another ICS/LABA, health plan disenrollment, or the end of data availability (September 30, 2016). Patients were included if they had ≥12 months of continuous eligibility before the index date, ≥3 months of continuous eligibility after the index date, ≥1 diagnosis of asthma during the baseline period or on the index date, and age of ≥18 years as of the index date. Patients were excluded if they had ≥1 diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cystic fibrosis during the baseline period, on the index date, or during the follow-up period, a diagnosis of acute respiratory failure during the baseline period or on the index date, or ≥1 prescription fill for any ICS/LABA (including the index medication) within the 12-month baseline period prior to the index prescription fill. The presence of specific conditions was identified using diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Disease, 9th/10th Edition, Clinical Modification (Supplementary Table S1 in supplementary material). This study utilized de-identified retrospective claims data compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and no institutional review board (IRB) approval was required.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was treatment adherence, measured by mean PDC in the follow-up period. To calculate PDC, the number of days the index medication was available (based on filled prescriptions) was divided by the total number of days of follow-up in the post-index period for each patient.

Secondary endpoints were treatment adherence, based on the proportion of patients who achieved PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 for the index medication during the follow-up period (including the index date), and persistence, as measured by time to index medication discontinuation. Medication discontinuation was defined as a gap in therapy of >45 days from the run-out date of the ICS/LABA pharmacy fill and the next fill, or between the end of the days of supply of the last dispensing and the end of follow-up, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to control for differences in baseline characteristics between treatment cohorts. Patients initiating FF/VI were separately matched 1:1 with patients initiating B/F and 1:1 with patients initiating FP/SAL using multivariable propensity score (PS) with a greedy matching algorithm and caliper widths of 0.01. The PS is the conditional probability of being treated with FF/VI based on observable baseline demographics and socioeconomic and clinical characteristics. PS was generated using probability estimates from a logistic regression model in which treatment with FF/VI was the binary (yes/no) dependent variable and patient characteristics were used as predictors of being treated with FF/VI. PS was used to match the FF/VI cohort with the B/F cohort, and separately with the FP/SAL cohort. After PSM, the distribution of patient characteristics of the post-matched cohorts was evaluated. Exact 1:1 matching was conducted on the factors that remained unbalanced between cohorts, including prescribing physician specialty, specifically respiratory specialists, and index medication costs.

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), an alternative method of correcting for differences in baseline characteristics between cohorts, was conducted as a sensitivity analysis. Unlike PSM, IPTW allows all patients to be retained for analysis. Each patient was attributed a weight, calculated as 1/PS for the FF/VI cohort and 1/(1-PS) for the B/F and FP/SAL cohorts. Weights were normalized by the mean weight.

Demographics and clinical characteristics were assessed during the 12-month baseline period and analyzed descriptively. Bivariate comparisons in the pre- and post-matched cohorts were based on p values and standardized differences. For bivariate comparisons of baseline characteristics between the pre-matched cohorts, significance was tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for unpaired continuous variables and the chi-square test for unpaired dichotomous variables; whereas the Wilcoxon sign-rank test for paired continuous variables and McNemar’s test for paired dichotomous variables were used for comparisons of the post-matched cohorts. For the IPTW sensitivity analyses, significance was evaluated using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables.

In the primary analysis, mean PDC and the proportion of patients achieving PDC by cutoff were compared in the post-matched cohorts. Multivariable regression models were used for post-match adjustment of covariates with residual imbalance, defined as p ≤ 0.05 following PSM or standardized difference ≥10% following inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Specifically, generalized linear regression was used for mean PDC and logistic regression was used for PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 endpoints.

To evaluate persistence with index therapy, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to calculate the cumulative incidence of index medication discontinuation. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze time-to-treatment discontinuation.

As an additional sensitivity analysis, a pre-specified subgroup analysis evaluated medication adherence and persistence among patients with at least 12 months of follow-up. For this analysis, additional residual imbalances in baseline characteristics were accounted for in the multivariable models since the baseline characteristics of this subgroup of patients differ from those of the overall study population.

Results

Study population

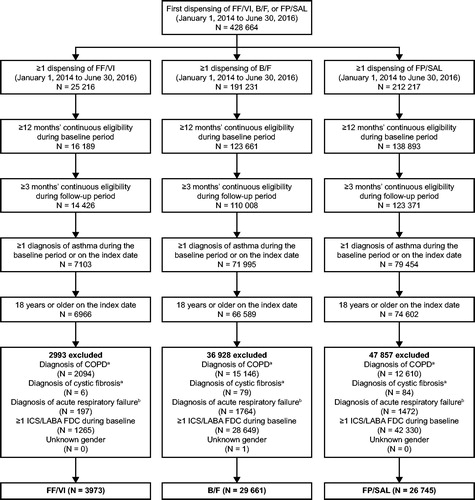

In total, 3,973 patients receiving treatment with FF/VI, 29,661 patients receiving B/F, and 26,745 patients receiving FP/SAL met the study criteria (). After PSM, 3,764 and 3,339 patients initiating FF/VI were matched to 3,764 patients receiving B/F and 3,339 patients receiving FP/SAL, respectively.

Figure 2. Study population selection. aDuring the baseline or follow-up period. bDuring the baseline period or on the index date. B/F, budesonide/formoterol; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FDC, fixed-dose combination; FF/VI, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol; FP/SAL, fluticasone propionate; ICS/LABA, inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist.

After matching, the mean post-index follow-up time was similar for the FF/VI and B/F cohorts (257.1 vs 260.3 days; p = 0.125) and for the FF/VI and FP/SAL cohorts (258.1 vs 259.8 days; p = 0.434). Selected post-match baseline demographics and clinical characteristics that may be related to adherence are described in . All pre- and post-match baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are described in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 in supplementary material.

Table 1. Selected post-match baseline characteristics.

Treatment adherence

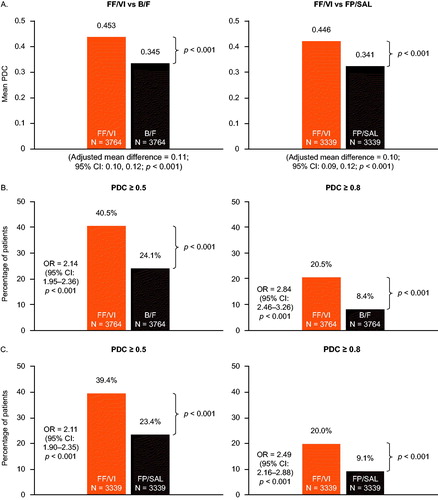

Mean PDC was significantly higher among FF/VI initiators compared with either B/F or FP/SAL initiators (. For FF/VI versus B/F, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) PDC was 0.453 (0.300) in the FF/VI cohort and 0.345 (0.252) in the B/F cohort (p < 0.001), and the adjusted mean difference in PDC was 0.11 (95% CI: 0.10–0.12; p < 0.001). For FF/VI versus FP/SAL, the mean PDC (SD) was 0.446 (0.300) in the FF/VI cohort and 0.341 (0.257) in the FP/SAL cohort, with the adjusted mean difference in PDC as 0.10 (95% CI: 0.09–0.12; p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Mean PDC (A) and proportion of patients achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 with FF/VI versus B/F (B) and FF/VI versus FP/SAL (C). Mean PDC and OR were calculated using generalized linear regression and logistic regression models, respectively, including the following baseline covariates: (A) FF/VI versus B/F: region, insurance product type, log of all-cause medical cost, log of all-cause medical cost paid by patient, log of all-cause outpatient costs, number of all-cause outpatient visits, and baseline LAMA/LABA use (yes/no); (B) FF/VI versus FP/SAL: insurance product type, log of all-cause total cost, log of all-cause medical cost, log of all-cause ED visit cost, log of all-cause outpatient costs, log of all-cause medical cost paid by patient, number of all-cause ED visits, number of all-cause outpatient visits, and baseline rescue medication use (yes/no). B/F, budesonide/formoterol; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; FF/VI, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol; FP/SAL, fluticasone propionate; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; OR, odds ratio; PDC, proportion of days covered.

A greater proportion of FF/VI initiators achieved PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 compared with B/F initiators (40.5% vs 24.1%; p < 0.001 and 20.5% vs 8.4%; p < 0.001, respectively) and FP/SAL initiators (39.4% vs 23.4%; p < 0.001 and 20.0% vs 9.1%; p < 0.001, respectively). The adjusted odds of FF/VI initiators achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 were 2.14 times higher (95% CI: 1.95–2.36) and 2.84 times higher (95% CI: 2.46–3.26), respectively, compared with B/F initiators (. For FF/VI initiators versus FP/SAL initiators, the adjusted odds of achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 were 2.11 times higher (95% CI: 1.90–2.35) and 2.49 times higher (95% CI: 2.16–2.88), respectively (.

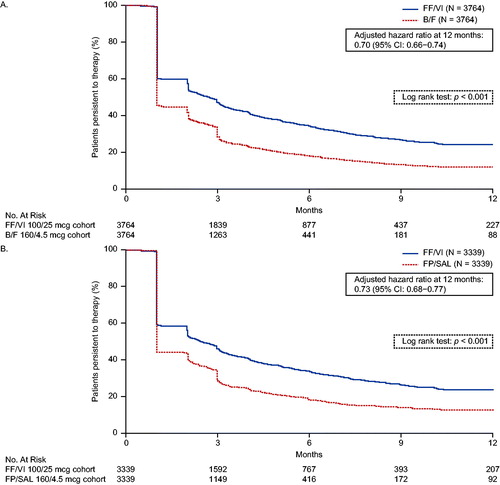

Treatment persistence

Kaplan–Meier curves of persistence to FF/VI versus B/F and to FF/VI versus FP/SAL are shown in , panels A and B, respectively. Treatment persistence was significantly better with FF/VI versus B/F (p < 0.001) and with FF/VI versus FP/SAL (p < 0.001). The adjusted risk of discontinuation was 30% lower (adjusted HR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.66–0.74) and 27% lower (adjusted HR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.68–0.77) among patients receiving FF/VI compared with patients receiving B/F and FP/SAL, respectively.

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier analysis of persistence to (A) FF/VI versus B/F and (B) FF/VI versus FP/SAL. Treatment discontinuation was defined as a gap in therapy of >45 days from the run-out date of the ICS/LABA pharmacy fill and the next fill, or between the end of the days of supply of the last dispensing and the end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. Hazard ratios were calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for baseline covariates including: (A) FF/VI versus B/F: region, insurance product type, log of all-cause medical cost, log of all-cause medical cost paid by patient, log of all-cause outpatient costs, number of all-cause outpatient visits, and baseline LAMA/LABA use (yes/no); (B) FF/VI versus FP/SAL: insurance product type, log of all-cause total cost, log of all-cause medical cost, log of all-cause ED cost, log of all-cause outpatient costs, log of all-cause medical cost paid by patient, number of all-cause ED visits, number of all-cause outpatient visits, and baseline rescue medication use (yes/no). B/F, budesonide/formoterol; ED, emergency department; FF/VI, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol; FP/SAL, fluticasone propionate; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Sensitivity analyses

In a pre-specified subgroup analysis of patients with 12 months of follow-up, mean PDC at 12 months and the odds of achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 and PDC ≥ 0.8 were significantly higher among FF/VI initiators compared with B/F and FP/SAL initiators, and the risk of discontinuation was significantly lower (all p < 0.001; Table S4 in supplementary material).

The sensitivity analysis of adherence using IPTW is shown in Table S5 in supplementary material. When IPTW was used as an alternative method, outcomes were consistent and similar to what was observed for the PSM analyses for all endpoints (all p < 0.001).

Discussion

This retrospective observational study used data from a large US claims database to evaluate treatment adherence and persistence among patients with asthma receiving once-daily FF/VI, twice-daily B/F, or twice daily FP/SAL in the real-world setting. Compared with B/F or FP/SAL initiators, patients initiating FF/VI had significantly better adherence and persistence to their medication. The findings in a subgroup of patients with at least 12 months of follow-up and in cohorts balanced using IPTW, an alternative method to correct for confounding differences in baseline characteristics, were consistent with the primary PSM analyses. These findings are based on a data source representing patient populations from multiple health plans and providers across the USA, and support recent studies that showed significantly higher mean PDC, greater odds of achieving PDC ≥ 0.5 or PDC ≥ 0.8, and lower risk of discontinuation among FF/VI initiators compared with B/F initiators (Citation24) or FP/SAL initiators (Citation25).

Previous studies have shown that adherence and persistence to controller medication among patients with asthma is suboptimal (Citation8–10,Citation15,Citation16,Citation20). While adherence in the present study was better among patients receiving FF/VI, low adherence to controller medications was observed across all cohorts. The range of mean PDC values across the cohorts was 0.34–0.45, which is consistent with the range of approximately 0.30–0.70 reported by previous studies of adherence to controller medications in patients with asthma (Citation8–10,Citation24). Additionally, a high proportion of patients in this study discontinued the index medication within 12 months, which is also consistent with earlier studies of persistence with controller medications (Citation26). Better adherence is associated with improved outcomes in patients with asthma, including a lower risk of exacerbations, reduced rescue medication use, and fewer asthma-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits (Citation11,Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation20,Citation21,Citation27–30). There is therefore an unmet need for treatment regimens promoting improved adherence and outcomes among patients with asthma.

The present study was the first head-to-head investigation of adherence to ICS/LABA FDCs administered via DPIs in patients with asthma in the USA, supporting the findings of a previous US-based study that compared adherence to FF/VI administered via a DPI and B/F via a pMDI in patients with asthma (Citation24). Patients receiving FF/VI demonstrated significantly higher mean PDC and probability of achieving a clinically significant level of adherence, as well as lower risk of discontinuation compared with those receiving B/F or FP/SAL. Adherence can be influenced by multiple factors, including patient understanding of the disease and treatments, as well as complexity of the medication regimen with respect to the number of agents, dosing frequency and ease of inhaler use (Citation1,Citation15,Citation16,Citation31,Citation32). The importance of dosing frequency in medication adherence in the real-world setting has been highlighted by previous studies demonstrating better adherence with once-daily versus twice-daily inhalers in patients receiving ICS monotherapy (Citation17–19,Citation21–23) and more recently with other controller medications (Citation20). The findings of the current study corroborate previous findings and provides additional evidence of the association of once-daily FF/VI with better adherence and persistence compared with twice-daily ICS/LABAs, specifically B/F and FP/SAL.

There are several general limitations associated with assumptions inherent in claims-based observational studies that should be considered in interpretation of the results of the present study. Firstly, this analysis used indirect measures of adherence and persistence, which were based on medical and pharmacy claims data and therefore not prospectively measured. Secondly, adherence was calculated using dispensing data; however, the presence of a claim for a filled prescription does not confirm that a patient used their medication, and medications obtained as samples or during inpatient visits are not captured. Thirdly, dosing frequency was not evaluated in this analysis, and as such it is assumed that dosing frequency for each product was in accordance with the relevant prescribing information. Finally, while PS methods and statistical modeling were used to balance cohorts on observed variables, as this was a non-randomized study, residual confounding could arise from variables not captured in matching, weighting or adjustment models, such as lung function, symptom severity, or smoking history. In addition, this study was not designed to assess the effects of increased adherence on outcomes such as exacerbations or oral corticosteroid use, and data on these outcomes in the follow-up period were not collected. Future studies are warranted to evaluate the relationship between adherence and outcomes. Despite these possible limitations, claims data are a valuable tool for assessing real-world treatment patterns, as they provide access to a large and diverse sample of patients initiated on different ICS/LABA treatments for asthma with a wide geographic distribution across the USA.

Conclusions

This retrospective study using a large US claims database found that patients initiating once-daily FF/VI had better adherence (as measured by PDC) and lower risk of discontinuing therapy compared with twice-daily B/F or FP/SAL in the real world. These findings suggest that once-daily ICS/LABA therapy could improve adherence and persistence relative to a twice-daily alternative.

Author contributions

The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. CA and RHS contributed to conception and design of the study and data analysis and interpretation. FL, JWW, GG, and MSD contributed to conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation.

Supplemental Material

Download (139.6 KB)Acknowledgements

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating authors’ comments, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Mark Condon, DPhil, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this analysis are based in part on data obtained under license from IQVIATM. Source: IQVIATM Health Plan Claims Data January 1, 2013–September 30, 2016, IQVIATM. All rights reserved. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IQVIATM or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Conflicts of interest

RHS and CMA are employees of GSK and hold stocks/shares in GSK. FL, JWW, GG, and MSD are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research funds from GSK. to conduct this study.

Data sharing

To request access to patient-level data and documents for this study, please submit an enquiry via www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. Data included in this manuscript are derived from a database owned by IQVIATM and contain proprietary elements, and therefore data cannot be broadly disclosed or made publicly available at this time. The disclosure of this data to third-party clients assumes certain data security and privacy protocols are in place and that the third-party client has executed IQVIA’s standard license agreement, which includes restrictive covenants governing the use of the data.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2018 [updated Mar 2018]. Available from: http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/.

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. 2007.

- Price DB, Colice G, Israel E, Roche N, Postma DS, Guilbert TW, van Aalderen WMC, Grigg J, Hillyer EV, Thomas V, et al. Add-on LABA in a separate inhaler as asthma step-up therapy versus increased dose of ICS or ICS/LABA combination inhaler. ERJ Open Res. 2016;2:00106-2015. doi:10.1183/23120541.00106-2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. New Drug Application (NDA): 204275 (Breo Ellipta) 2013 [cited 2018 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=204275.

- US Food and Drug Administration. New Drug Application (NDA): 021929 (Symbicort) 2006 [cited 2018 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=021929.

- US Food and Drug Administration. New Drug Application (NDA): 021077 (Advair Diskus) 2000 [updated 2017; cited 2018 Dec19]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=021077.

- US Food and Drug Administration. New Drug Application (NDA): 021254 (Advair HFA) 2006 [cited 2019 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=021254.

- Wu AC, Butler MG, Li L, Fung V, Kharbanda EO, Larkin EK, Vollmer WM, Miroshnik I, Davis RL, Lieu TA, et al. Primary adherence to controller medications for asthma is poor. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:161–6. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-459OC.

- Makhinova T, Barner JC, Richards KM, Rascati KL. Asthma controller medication adherence, risk of exacerbation, and use of rescue agents among texas medicaid patients with persistent asthma. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21:1124–1132. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.12.1124.

- Boutopoulou B, Koumpagioti D, Matziou V, Priftis KN, Douros K. Interventions on adherence to treatment in children with severe asthma: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:232.

- Engelkes M, Janssens HM, de Jongste JC, Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:396–407. doi:10.1183/09031936.00075614.

- Gold LS, Yeung K, Smith N, Allen-Ramey FC, Nathan RA, Sullivan SD. Asthma control, cost and race: results from a national survey. J Asthma. 2013;50:783–90. doi:10.3109/02770903.2013.795589.

- Stern L, Berman J, Lumry W, Katz L, Wang L, Rosenblatt L, Doyle JJ. Medication compliance and disease exacerbation in patients with asthma: a retrospective study of managed care data. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:402–8. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60808-3.

- Delea TE, Stanford RH, Hagiwara M, Stempel DA. Association between adherence with fixed dose combination fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on asthma outcomes and costs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3435–42. doi:10.1185/03007990802557344.

- Dima AL, Hernandez G, Cunillera O, Ferrer M, de Bruin M, Group A-L. Asthma inhaler adherence determinants in adults: systematic review of observational data. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:994–1018. doi:10.1183/09031936.00172114.

- Makela MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, Larsson K. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107:1481–90. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2013.04.005.

- Price D, Robertson A, Bullen K, Rand C, Horne R, Staudinger H. Improved adherence with once-daily versus twice-daily dosing of mometasone furoate administered via a dry powder inhaler: a randomized open-label study. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10:1. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-10-1.

- Wells KE, Peterson EL, Ahmedani BK, Williams LK. Real-world effects of once vs greater daily inhaled corticosteroid dosing on medication adherence. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:216–20. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.008.

- Dal Negro RW, Bonadiman L, Turco P. Fluticasone furoate/vilanterol 92/22 mug once-a-day vs beclomethasone dipropionate/formoterol 100/6 mug b.I.D.: a 12-month comparison of outcomes in mild-to-moderate asthma. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2018;13:18. doi:10.1186/s40248-018-0131-x.

- de Llano LP, Sanmartin AP, González-Barcala FJ, Mosteiro-Añón M, Abelaira DC, Quintas RD, Ventosa MM. Assessing adherence to inhaled medication in asthma: Impact of once-daily versus twice-daily dosing frequency. The ATAUD study. J Asthma. 2018;55:933–8. doi:10.1080/02770903.2018.1426769.

- Navaratnam P, Friedman HS, Urdaneta E. Treatment with inhaled mometasone furoate reduces short-acting beta(2) agonist claims and increases adherence compared to fluticasone propionate in asthma patients. Value Health. 2011;14:339–46. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2011.01.001.

- Guest JF, Davie AM, Ruiz FJ, Greener MJ. Switching asthma patients to a once-daily inhaled steroid improves compliance and reduces healthcare costs. Prim Care Respir J 2005;14:88–98. doi:10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.01.002.

- Friedman HS, Navaratnam P, McLaughlin J. Adherence and asthma control with mometasone furoate versus fluticasone propionate in adolescents and young adults with mild asthma. J Asthma. 2010;47:994–1000. doi:10.1080/02770903.2010.513076.

- Stanford RH, Averell C, Parker ED, Blauer-Peterson C, Reinsch TK, Buikema AR. Assessment of adherence and asthma medication ratio (AMR) for a once-daily and twice-daily inhaled corticosteroid/long acting beta agonist (ICS/LABA) for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:14-1496.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.12.021.

- Atsuta R, Takai J, Mukai I, Kobayashi A, Ishii T, Svedsater H. Patients with asthma prescribed once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol or twice-daily fluticasone propionate/salmeterol as maintenance treatment: analysis from a claims database. Pulm Ther. 2018;4:135. doi:10.1007/s41030-018-0084-4.

- Marceau C, Lemiere C, Berbiche D, Perreault S, Blais L. Persistence, adherence, and effectiveness of combination therapy among adult patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:574–81. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.034.

- Williams LK, Peterson EL, Wells K, Ahmedani BK, Kumar R, Burchard EG, Chowdhry VK, Favro D, Lanfear DE, Pladevall M, et al. Quantifying the proportion of severe asthma exacerbations attributable to inhaled corticosteroid nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1185–91. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.011.

- Williams LK, Pladevall M, Xi H, Peterson EL, Joseph C, Lafata JE, Ownby DR, Johnson CC. Relationship between adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and poor outcomes among adults with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1288–93. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.028.

- Price D, Harrow B, Small M, Pike J, Higgins V. Establishing the relationship of inhaler satisfaction, treatment adherence, and patient outcomes: a prospective, real-world, cross-sectional survey of US adult asthma patients and physicians. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8:26. doi:10.1186/s40413-015-0075-y.

- Ismaila A, Corriveau D, Vaillancourt J, Parsons D, Stanford R, Su Z, Sampalis JS. Impact of adherence to treatment with fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in asthma patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1417–25. doi:10.1185/03007995.2014.908827.

- Oland AA, Booster GD, Bender BG. Psychological and lifestyle risk factors for asthma exacerbations and morbidity in children. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10:35doi:10.1186/s40413-017-0169-9.

- Gillisen A. Patient’s adherence in asthma. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;58:205–22.