Abstract

Objective

Despite advances in treatment, asthma remains uncontrolled in many patients, with increased risk of exacerbation and associated healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). We describe patient characteristics, exacerbations, asthma control, and HCRU using GINA treatment step (GS) as a proxy for asthma severity.

Methods

Using a large, US, health-claims database, 4 longitudinal cohorts of 517,738 patients in GS2–5, including a subgroup of patients with baseline eosinophil (EOS) counts, were analyzed retrospectively (study period 2010 − 2016). Index for each cohort was patients’ first time entering the GS, determined by first claim of first regimen. Uncontrolled asthma was defined according to published criteria as a multi-dimensional measure that includes number of exacerbations. Key variables including, baseline characteristics, post-index exacerbations, and HCRU (all-cause and asthma-specific events) are summarized by descriptive statistics.

Results

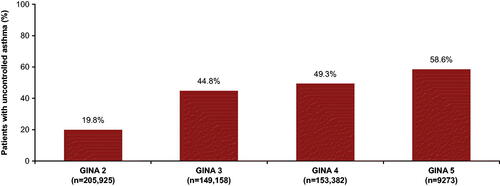

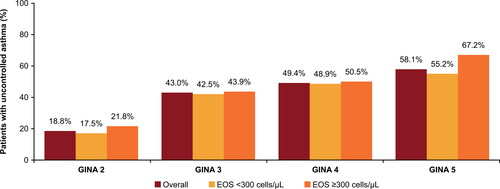

Uncontrolled asthma was reported in 19.8% patients in GS2, 44.8% in GS3, 49.3% in GS4, and 58.6% in GS5. Annualized mean (SD) rates of exacerbation 12 months post-index generally increased across GS2–5 (0.26 [0.86], 0.32 [0.79], 0.36 [0.83], 0.29 [0.86], respectively). HCRU also increased with increasing GS, with higher HCRU among the uncontrolled cohort within each GS. In patients with EOS ≥300 cells/µL, uncontrolled asthma also increased with increasing GS (21.8%, 43.9%, 50.5%, 67.2% for GS2–5, respectively).

Conclusions

This large database study provides real-world evidence of the substantial degree of uncontrolled asthma in US clinical practice across GS, supporting calls for better asthma management. Healthcare burden tends to increase with lack of control in all groups, highlighting the need for improved patient education, adherence, access, and treatment optimization.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at publisher’s website.

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease (Citation1) that affects more than 26 million people in the United States (US), comprising ∼8% of the total population (Citation2), and its prevalence is increasing (Citation3). The aims of asthma treatment are to achieve and maintain control of symptoms, and minimize risk of future exacerbations (Citation1). The treatment guidelines provided by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recommend a stepwise approach to disease management, with each step representing an increase in intensity of treatment required to achieve control (Citation1).

Despite implementation of these guidelines, asthma remains poorly controlled in many patients, with inadequate or suboptimal control present in approximately 45–57% of patients (Citation4–6), and high exacerbation rates (a key component of control) reported worldwide (Citation7–9). Patients with poorly controlled asthma report a greater impact of their disease on work productivity, lower health-related quality of life, greater healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), and more frequent feelings of anxiety and depression vs. those with well-controlled disease (Citation4–6). In addition, poor symptom control is associated with increased risk of future exacerbations, long-term airway damage, and increased hospitalizations (Citation1,Citation10–14).

To date, very few real-world studies have adequately evaluated asthma control or stratified patients by treatment step, and few studies have included all age groups and investigated the HCRU of uncontrolled patients in the US (Citation4–6,Citation9,Citation13–17). The aims of this observational, retrospective study of a US health claims database are to describe demographic and clinical characteristics, disease exacerbations, asthma control, and HCRU in a large study of both pediatric and adult patients with asthma, using patients’ GINA treatment step (GINA step) as a proxy for disease severity. This will provide US stakeholders and physicians a more complete picture on which to base their decision making.

Methods

Study design

Our study was a retrospective, longitudinal cohort analysis of data retrieved from Optum® Clinformatics® Data Mart™ (the Optum database), a large US administrative health claims dataset of a commercially insured patient population, including a proportion of patients on Medicare Advantage (>65 years old). The population includes data for members across all ethnicities and US states who are commercially insured. The study period ran from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2016. The index date was determined by the date a patient made their first claim for their first asthma treatment regimen and the baseline period was defined as 12 months prior to this index date. Patients were identified from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2015 and were followed up from their index date either to GINA step change (up or down) or for 12 months, whichever occurred first (Supplementary Figure 1).

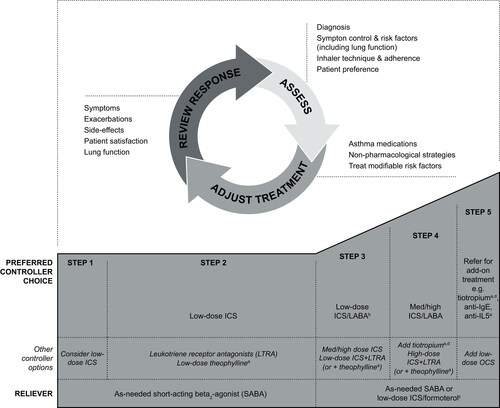

Figure 1. The GINA stepwise approach to disease management (Citation18) used for cohort allocation in this study. ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; med, medium (dose); OCS, oral corticosteroids; anti-IgE, anti-immunoglobulin E therapy; anti-IL5, anti-interleukin 5.

aNot for children <12 years.

bFor children 6–11 years old, the preferred Step 3 treatment is medium-dose ICS.

cLow-dose ICS/formoterol is the reliever medication for patients prescribed low-dose budesonide/formoterol or low-dose beclometasone/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy.

dTiotropium by mist inhaler is an add-on treatment for patients with a history of exacerbations; it is not indicated in children <12 years.

Reproduced from: Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2017 (Citation18). More recent GINA guidelines are available; figure provided here reflects that used at time of study.

GINA step is a well-established criterion to assess asthma severity and was used as a proxy for patient disease severity in this study. To assess which GINA step cohort the patient should be categorized into, severity was assigned retrospectively by the treatment needed to achieve control of symptoms and exacerbations based on the 2017 GINA guidelines (the most recent guidelines at the time this study was conducted) (Citation18). GINA Step 2 was used as a proxy for mild asthma, step 3 for moderate asthma and Steps 4 and 5 for severe asthma (Citation18). The treatment regimens that fall within each GINA step (from Step 2 onwards) are shown in . The definitions of asthma, allergic rhinitis and COPD were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth revisions, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) codes.

Data collection and analysis

Data in the baseline period for patients in each GINA step cohort (Step ≥2) were analyzed for baseline demographics and clinical characteristics. Criteria for uncontrolled asthma shown in were determined to measure control across disease severity and include standard measures similar to those used in other studies (Citation14,Citation17,Citation18). Exacerbations were defined as a hospital admission, ER visit with a primary diagnosis for asthma or asthma exacerbation, or an outpatient visit with a diagnosis for asthma with an OCS prescription order within 7 days.

Table 1. Study criteria for uncontrolled asthma (Citation19).

Patients could be included in multiple GINA steps but only the first time they entered each GINA step was used for analysis. As an example, a patient who entered GINA Step 3 with a medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS; March 2012), stepped up to medium-dose ICS/long-acting β2 agonist (LABA; January 2013), and then stepped down to medium-dose ICS (October 2013), would be included in the Step 3 cohort (index: March 2012) and followed up till January 2013; this patient would also be included in the Step 4 cohort (index: January 2013) and followed up until October 2013. The patient’s second time entering GINA Step 3 (October 2013) would not be used to avoid double-counting. The rationale for this approach was to examine the dynamics of uncontrolled asthma within each treatment step and capture when patients experience a change in treatment and move to a higher GINA step in order to achieve control.

In addition to typical claims-related data, the Optum database includes outpatient laboratory test results for 35 − 40% of patients. Patients with available eosinophil (EOS) data in the baseline period were included as a subgroup and were characterized by EOS count (<300 cells/µL; ≥300 cells/µL) and age (≥12 to <18 years; ≥18 years). Associations between blood EOS level and asthma control status were evaluated.

All-cause and asthma-specific HCRU were analyzed in patients with at least 30 days’ follow-up by evaluation of the annualized rate of hospitalizations, inpatient days, outpatient visits, and number of emergency room (ER) visits. Asthma-specific HCRU included hospital admission or ER visits with a primary diagnosis for asthma or asthma exacerbations, or outpatient visits with an asthma diagnosis plus an OCS prescription. Annualized rates were calculated by the number of events (e.g. hospitalizations, inpatient days, etc.) divided by time (either number of months from entering a GINA step to end of step, or 12 months, whichever came first).

Patients

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the analysis if they were: aged ≥6 years at index; had continuous medical and pharmacy benefit claims for 12 months pre- and post-index; had ≥2 outpatient asthma diagnoses during the set identification period (1 January 2011 to 31 December 2015) that were ≥7 days apart, or 1 outpatient asthma diagnosis and ≥2 pharmacy claims for asthma control medications, or ≥2 pharmacy claims for asthma-specific medications, or ≥1 ER or inpatient asthma diagnosis.

Patients were required to meet the criteria for GINA Step 2 or above. For patients included in the EOS subgroup, at least 1 EOS measurement in the 12 months prior to or 3 months after the index date was required. Patients with cystic fibrosis, COPD, or autoimmune diseases (e.g. ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) were excluded from this analysis.

This study was designed in accordance with the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (Citation20), the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (Citation21), and with the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. Information retrieved from the health claims database was de-identified for compliance with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) regulations regarding the protection of human subjects.

Statistical analysis

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics were summarized descriptively by GINA step and age group. Patients in the overall and uncontrolled cohorts were summarized descriptively by GINA step. Annualized exacerbation rate and annualized HCRU outcomes in the follow-up period (from index date either to GINA step change or up to 12 months) were derived among patients with at least 30 days’ follow-up, in order to minimize the impact of extreme outliers on the annualized rates due to very short follow-up periods. Data were summarized descriptively by type of visit and GINA step for the overall, controlled, and uncontrolled populations.

Descriptive statistics by GINA step and age group overall, and by disease control status, were used for blood EOS levels in the EOS subgroup. The closest EOS data to the index date in the 12-month pre-index period were used.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

Patient claims data were derived from the Optum database, which contains inpatient and outpatient medical, and outpatient prescription drug information of patients in employment and their dependents with employer-sponsored insurance and retirees who opt into Medicare Advantage insurance plans offered by private companies. summarizes the patient distribution by GINA step category. A total of 668,113 patients were available for analysis; of these 517,738 patients could be categorized into GINA steps 2–5 based on their treatment regimen. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics including number of exacerbations in the 12 months prior to index, are presented in , and are shown by GINA step for the overall cohort and for the subgroup of patients with EOS counts in the baseline period.

Table 2. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by GINA step in the overall cohort and subgroup of patients with evaluable EOS data.

Overall cohort in the baseline period

The majority (∼75%) of patients were aged 18 years or older. Mean (standard deviation; SD) age generally increased with increasing GINA step and was notably higher for those in GINA Step 5 (60.1 [18.1] years) compared with those in Step 2 (37.7 [23.1] years), Step 3 (36.6 [23.8] years), and Step 4 (48.6 [20.6] years). The proportion of females (range: 59.3%–61.2%) was consistently higher than males (range: 38.8%–43.9%) in each GINA step ().

The presence of comorbidities, as assessed by the Charlson Comorbidity Index, was lowest in GINA Step 2 (mean 0.4 [SD 1.1]) and Step 3 (0.4 [1.0]); this value rose slightly in Step 4 (0.5 [1.2]) and then increased 3-fold, to 1.5 (2.3), for patients in Step 5 (). For pre-specified allergic comorbidities, the presence of allergic rhinitis declined with increasing GINA step, from 39.2% of patients in GINA Step 2 to 23.8% of patients in Step 5. In contrast, comorbid chronic sinusitis was more common in GINA Step 5 (12.3%) than in Steps 2–4 (8.7%–10.8%).

The mean (SD) number of exacerbations in the 12 months prior to index date increased with increasing GINA step, starting at 0.23 (0.59) in Step 2, 0.28 (0.63), and 0.32 (0.71) in Steps 3 and 4, respectively, and 0.39 (0.95) in Step 5 (). GINA Step 5 included a higher proportion of patients with multiple (≥2) exacerbations than in the lower GINA steps (8.2% vs. 4.1%, 5.0% and 6.2% in GINA Steps 2–4, respectively), and a similar trend was seen for the proportions of patients with ≥3 exacerbations. The proportion of patients free from exacerbations in the 12 months prior to index ranged from 77.3% to 82.8%, with the lowest proportion in the GINA Step 5 cohort.

Treatment use by GINA step

The proportions of patients on their first treatment regimen falling within GINA Steps 2–5 are shown in . The most common regimen in GINA Step 2 was leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) monotherapy, received by 77.9% of patients in this cohort, and 21.1% received low-dose ICS. In GINA Step 3, 20.1% of patients received the preferred controller low-dose ICS/LABA, 44.5% received medium-dose ICS and 20.9% received high-dose ICS. In GINA Step 4, most patients received the preferred treatments of medium-dose ICS/LABA (46.6%) and high-dose ICS/LABA (27.6%). The most common regimen in GINA Step 5 was GINA Step 4 therapy plus an add-on biologic treatment, reported in 75.3% of patients in the cohort.

EOS subgroup in the baseline period

In general, baseline demographics and clinical characteristics in the EOS subgroup were similar to the overall cohort; one exception was that the proportion of patients aged 18 years or older was higher vs. the overall cohort (86.0%–97.5% vs. 65.6%–96.7%) across all GINA steps (). For patients with baseline EOS count ≥300 cells/µL, the smallest proportion (24.7%) was seen in GINA Step 5 and the largest in GINA Step 4 (33.7%). When stratified by age, over 60% of adolescents had baseline EOS counts <300 cells/μL across all GINA steps. In general, a larger proportion of adolescent than adult patients had baseline EOS counts ≥300 cells/μL across GINA Steps 2–4 ().

Frequency of exacerbations post-index

In the overall cohort of patients with ≥30 days’ follow-up, mean (SD) annualized rates of exacerbation in the follow-up period for GINA Steps 2 (n = 196,034), 3 (n = 146,259), 4 (n = 152,984) and 5 (n = 8892) were 0.26 (0.86), 0.32 (0.79), 0.36 (0.83), and 0.29 (0.86), respectively ().

Asthma control by GINA step: overall cohort

In the overall cohort, the proportion of patients with uncontrolled asthma increased with each subsequent GINA step, with 40,828/205,925 (19.8%) patients in Step 2, 66,864/149,158 (44.8%) in Step 3, 75,548/153,382 (49.3%) in Step 4, and 5430/9273 (58.6%) in Step 5. Uncontrolled asthma was thus 2–3-fold higher among patients in Steps 3–5 (45–59%) compared with Step 2 (20%; ).

HCRU by GINA step and asthma control status

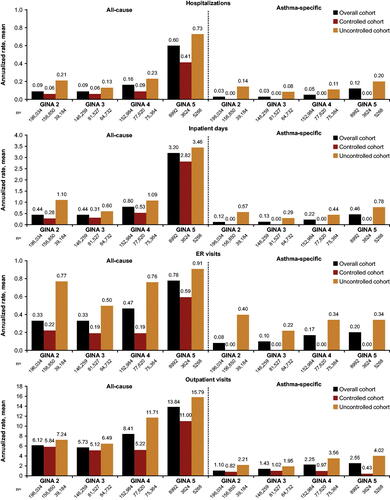

In the overall, controlled and uncontrolled subgroups, HCRU generally increased with increasing disease severity, as indicated by increasing GINA step (; Supplementary Table 3). The most pronounced difference between the overall vs. the uncontrolled cohort was seen in asthma-specific ER visits, with annualized rates consistently higher in the uncontrolled population across all GINA steps. There was a higher rate of annualized asthma-specific ER visits among GINA Step 2 patients (0.40) vs. GINA Steps 3–5 (0.22–0.34), which may be associated with receiving suboptimal treatment. Within each of the GINA steps, for all four HCRU outcomes, HCRU was repeatedly higher in the uncontrolled population vs. the overall and controlled cohorts.

Figure 3. All-cause and asthma-specific healthcare resource utilization by GINA Step in the overall, controlled, and uncontrolled cohorts. ER, emergency room; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma. Overall cohort is the combined controlled and uncontrolled subgroups. Uncontrolled status is a multi-dimensional measure as defined in , and by definition the controlled cohort should have zero asthma-specific hospitalizations/inpatient days/ER visits.

Asthma control by GINA step: EOS subgroup

The proportion of patients with uncontrolled asthma in the EOS subgroup increased with increasing GINA step. In GINA Step 5, a 12% absolute difference in presence of uncontrolled asthma was seen for patients with high EOS counts (67.2%) vs. those with low EOS counts (55.2%); .

Discussion

In this large, retrospective, longitudinal cohort analysis of more than half a million patients with asthma, over 45% of patients in GINA Steps 3, 4, and 5 had uncontrolled asthma. Similar or higher levels of uncontrolled asthma have been reported in the literature (Citation4,Citation14,Citation22), and this study contributes a US perspective to the body of knowledge. Asthma control was a multi-dimensional measure determined by asthma exacerbations, treatment step-up, or frequency of short-acting β2 agonist use. In all GINA steps, exacerbation rates were indicative of poorly controlled asthma, although the rates of exacerbation are at the lower end of the range reported in other studies (Citation14,Citation23). Our data are from a database analysis of patients already receiving medication to control their asthma, and will therefore differ from interventional studies reporting patient outcomes prior to receiving optimal medication (Citation24). Additionally, the methodology to assess exacerbations or control status is not consistent across studies, and asthma management is not expected to be comparable in different countries or in different patient populations. Notably, the rate of exacerbation reported for patients in Step 4 (0.36) is higher than in GINA Step 5 (0.29). The sample size of GINA step 5 is smaller than GINA steps 2–4, and therefore we may be artificially underestimating the exacerbation rate. Furthermore, exacerbation is also not the only criterion that determines the GINA step category, and those patients in Step 5 may have more severe asthma with less exacerbations due to the step up in treatment management.

The proportion of uncontrolled asthma increased with higher GINA step, with 45%, 49%, and 59% of those in GINA Steps 3, 4, and 5, respectively. It is important to note that these results were not statistically validated; however, the observed trends in this descriptive study demonstrate poorly controlled asthma across the spectrum of disease severity. Furthermore, our study supports existing literature from a small number of studies examining asthma control in the UK and the US (Citation9,Citation14). It is recognized that multiple contributory factors, such as lack of treatment response, history of exacerbations (Citation13,Citation14), and existing comorbidities (Citation25,Citation26), all affect disease control. In addition, a patient’s adherence to treatment (Citation1,Citation27,Citation28), inhaler technique (Citation29,Citation30), education (Citation31), and attitude toward asthma, particularly regarding evaluation of disease severity and interpretation of symptom control and management (Citation4), also have a bearing on disease control status. Country-specific differences in asthma control are also expected to reflect differences in access to treatment, prescribing practices and socioeconomic factors, and we report here the control status of insured patients with asthma in the US. Although not captured in insurance claims databases, the ability to track patient-reported outcome measures combined with more traditional metrics of control, as well as the use of biomarkers, will enhance the measurement of asthma control in future studies (Citation32).

HCRU generally increased with higher GINA step, and was highest among patients in GINA Step 5. This trend was generally seen across all 4 HCRU measures (hospitalizations, inpatient days, outpatient visits, and ER visits), although high values for HCRU were also seen in GINA Step 2. One possible explanation for this is that there may have been a higher proportion of newly diagnosed patients in the GINA Step 2 group who were yet to receive optimal treatment (e.g. over three-quarters of patients in GINA Step 2 received LTRA monotherapy as their first regimen), and thus were at risk of transitioning to higher GINA steps over time. LTRA monotherapy use is known to be higher in real-world clinical practice, particularly in the US, than advised in treatment guidelines, possibly also relating to specific concerns about side effects with ICS, ease of administration of LTRA and its favorable safety profile (Citation1,Citation33–36). We also speculate that LTRA may have been prescribed for some patients to treat allergic rhinitis, a common asthma comorbidity (Citation37). Another factor is that adherence to treatment may be poor in mild asthma when symptoms are less frequent, possibly contributing to the higher HCRU rates observed among patients in GINA Step 2. It is not unexpected that uncontrolled asthma-specific HCRU was markedly high in GINA Step 2. Results from randomized clinical trials demonstrating that mild asthma was associated with severe exacerbations (Citation38,Citation39) led to changes in the 2019 treatment guidelines for GINA Step 2, and we provide real-world evidence to strengthen these recommendations.

Within each GINA step, higher levels of HCRU were consistently seen for patients with uncontrolled disease compared with those in the overall cohort. The difference in HCRU between uncontrolled and overall populations was particularly pronounced for asthma-specific ER visits. This suggests patients with uncontrolled asthma continue to experience disease exacerbations and require medical attention at the ER. This finding also demonstrates the higher burden that is placed on healthcare resources when asthma is not adequately controlled.

The highest rates of HCRU, especially hospitalizations, were seen in GINA Step 5. This may be a result of the higher mean age of those in the GINA Step 5 cohort (e.g. ∼60 years in Step 5 vs. <40 years in Steps 2 and 3), as older patients with asthma may be expected to have a greater number of comorbidities compared with younger patients (Citation40,Citation41), leading to higher HCRU.

The proportion of patients with EOS data available generally increased with increasing GINA step. This may be related to patients with more severe asthma visiting their physician more frequently, and undergoing more laboratory tests. In the EOS subgroup, 75% of patients in GINA Step 5 had baseline EOS counts under 300 cells/µL. Interpretation of these data must take into account that GINA Step 5 represents patients with severe disease whose treatment regimen may contribute to suppressed EOS levels (Citation42,Citation43). However, among patients in GINA Step 5, there was a notably higher percentage of patients with uncontrolled asthma in the higher baseline EOS count (≥300 cells/μL) group than in the lower baseline EOS count group, suggesting that despite confounding factors, EOS level is still a useful biomarker that could play a role in individualized asthma management alongside other metrics of disease severity (Citation44).

It is also possible that the difference in control status at GINA Step 5 in these patients may be related to a higher level of comorbidities, as a general trend of increasing comorbidities with increasing GINA step was seen, suggesting a potential association with suboptimal disease control. The higher proportion of adults in later GINA steps would also contribute to the increasing trend in comorbidities. The presence of allergic rhinitis, however, decreased with increasing GINA step, consistent with the expectation that this condition would decline due to treatment with biologics and/or OCS in Step 5 plus the fact that rates of allergic rhinitis are generally higher in younger patients (Citation45).

Given the high proportion of patients in our study with uncontrolled asthma, we believe this highlights an unmet need in patients who receive escalating levels of treatment but continue to have uncontrolled disease. This observation among US patients is supported by the findings of the European REALIZE study (Citation4) of 8000 patients with asthma, in which disease control was poor, and symptoms and exacerbations were common. Notably, while 44% of participants experienced acute exacerbations, 24% had visited an ER and 12% had been hospitalized, more than 80% considered their asthma to be controlled and over two-thirds did not regard their condition as serious (Citation4), showing a clear disconnect between patient-perceived and guideline-defined asthma control. In a global study of perspectives on asthma management among physicians, when asked why patients may not have received the treatments they were prescribed, the most common reason (given by 59% of physicians) was that patients failed to understand the importance of using the medication (Citation46), highlighting the necessity of improved patient education and support (Citation16). A recent expert review focused on poor inhaler adherence as a root cause of increasing exacerbations, with many factors contributing to both intentional and unintentional poor adherence (Citation47). Technological advances in monitoring inhaler use and the use of other validated assessment tools, as well as the development of online resources to enable greater access to specialist care, will go some way to bridging the gap between treatment guidelines and treatment in practice (Citation32,Citation47,Citation48). To address the unmet need in therapy-resistant asthma, research efforts should focus on developing new treatments for patients who cannot be helped with improved management (Citation49).

With over half a million patients with asthma in the dataset analyzed, one of the strengths of this study is the considerable size of the study population. In addition, the analytical approach of examining uncontrolled asthma by GINA step in a longitudinal fashion, and using a definition of uncontrolled asthma that accommodates a change in treatment regimen or change in GINA step, is distinct and reflects the dynamics of real-world clinical practice. It should be noted that patients were classified by GINA step according to the treatment regimen they were on during the study period. Therefore, if a patient’s treatment regimen changed over the course of the study period, they may have been included in both the previous and new GINA step. However, since we only examined rates of severity for patients within each GINA step and not across all GINA steps, patients were not double-counted. Asthma severity was assessed based on the physician-prescribed treatment regimen considered appropriate to control their disease. As a result, the treatment regimen prescribed may not have been consistent with the patient’s actual disease severity, however, it does mean the data are reflective of real-world practice and demonstrate the actual clinical application of the treatment guidelines. Only a few other studies have examined controlled or uncontrolled asthma status by GINA-defined treatment steps 2–5. Although our study design precludes across-group comparisons, the analysis reflects the dynamic movement of patients through the GINA steps and importantly, we can compare the rates of severity within each GINA step (Citation2–5).

Regarding asthma control status, the number of patients with uncontrolled disease in GINA Step 5 may have been underestimated given that there is no further option to step up therapy. It is also conceivable that some patients who had a GINA treatment step up, an increase in dose, or the addition of another controller medication, may have done so for reasons other than having uncontrolled asthma, although this seems unlikely. An additional study limitation is that it was not possible to fully account either for patient adherence to treatment or the quality of administration (Citation29,Citation30).

As this was a retrospective analysis based upon insurance claims, some general limitations of the study should be recognized, and we acknowledge their impact on the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn. Limitations of data access means that it is impossible to provide further information regarding ethnicity, socioeconomic status, insurance plan coverage, treatment settings, and other non-pharmacologic factors, such as smoking status, that may have influenced treatment selection and thus asthma control. Generalization of the results to patients in other countries, with different healthcare systems, is unknown.

Conclusions

To the authors’ knowledge, estimates of asthma control have not been previously assessed across GINA treatment steps in such a large cohort of patients in a real-world setting. The results of this US-based population study indicate that a high percentage of patients with asthma remain uncontrolled and have asthma-specific ER visits and hospitalizations despite receiving asthma medications. The fact that patients across the spectrum of disease severity remain prone to exacerbations highlights the need for regular assessment of asthma control and appropriate use of guideline-recommended treatments (Citation32). Further research is warranted to better understand the complex barriers to adequate treatment and control.

Declaration of interest

WWB reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sanofi. JF, JM, PA, and HC are employees and stockholders of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. HT is an employee of Novartis Services Inc.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (246.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Authors employed by Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation were involved in the study design; interpretation of data; writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors received editorial support for this manuscript from Heather St Michael and Laura Buck of Fishawack Communications Ltd., part of Fishawack Health, funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA.

Additional information

Funding

Funding

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention (2018 update). Available from: www.ginasthma.org [last accessed 24 September 2018].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent asthma data 2018 (updated May 2018). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm [last accessed 8 November 2018].

- GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(17)30293-x.

- Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9.

- Braido F, Brusselle G, Guastalla D, Ingrassia E, Nicolini G, Price D, Roche N, Soriano JB, Worth H, LIAISON Study Group. Determinants and impact of suboptimal asthma control in Europe: the international cross-sectional and longitudinal assessment on asthma control (LIAISON) study. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0374-z.

- Lee LK, Obi E, Paknis B, Kavati A, Chipps B. Asthma control and disease burden in patients with asthma and allergic comorbidities. J Asthma. 2018;55(2):208–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.1316394.

- Ban GY, Ye YM, Lee Y, Kim JE, Nam YH, Lee SK, Kim JH, Jung KS, Kim SH, Park HS. Predictors of asthma control by stepwise treatment in elderly asthmatic patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(8):1042–1047. doi:https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.8.1042.

- Tay TR, Wong HS, Tee A. Predictors of future exacerbations in a multi-ethnic Asian population with asthma. J Asthma. 2019;56:380–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2018.1458862.

- Bloom CI, Nissen F, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L, Cullinan P, Quint JK. Exacerbation risk and characterisation of the UK’s asthma population from infants to old age. Thorax. 2018;73(4):313–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210650.

- Castillo JR, Peters SP, Busse WW. Asthma exacerbations: pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):918–927. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.001.

- King GG, James A, Harkness L, Wark PAB. Pathophysiology of severe asthma: we’ve only just started. Respirology. 2018;23(3):262–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13251.

- Matsunaga K, Hirano T, Oka A, Tanaka A, Kanai K, Kikuchi T, Hayata A, Akamatsu H, Akamatsu K, Koh Y, et al. Progression of irreversible airflow limitation in asthma: correlation with severe exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(5):759–764.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2015.05.005.

- Quezada W, Kwak ES, Reibman J, Rogers L, Mastronarde J, Teague WG, Wei C, Holbrook JT, DiMango E. Predictors of asthma exacerbation among patients with poorly controlled asthma despite inhaled corticosteroid treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(2):112–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2015.11.011.

- Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, Albers FC. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0409-3.

- Sicras-Mainar A, Capel M, Navarro-Artieda R, Nuevo J, Orellana M, Resler G. Real-life retrospective observational study to determine the prevalence and economic burden of severe asthma in Spain. J Med Econ. 2020;23(5):492–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2020.1719118.

- de Groot EP, Kreggemeijer WJ, Brand PL. Getting the basics right resolves most cases of uncontrolled and problematic asthma. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(9):916–921. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13059.

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Navaratnam P, Friedman HS, Kavati A, Ortiz B, Lanier B. National prevalence of poor asthma control and associated outcomes among school-aged children in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):536–544.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.039.

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention (2017 update). Available from: www.ginasthma.org [last accessed 2 April 2019].

- Broder MS, Chang EY, Kamath T, Sapra S. Poor disease control among insured users of high-dose combination therapy for asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(1):60–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2010.31.3302.

- International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology: Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2008;17:200–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1471.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

- Buhl R, Heaney LG, Loefroth E, Larbig M, Kostikas K, Conti V, Cao H. One-year follow up of asthmatic patients newly initiated on treatment with medium- or high-dose inhaled corticosteroid-long-acting β2-agonist in UK primary care settings. Respir Med. 2020;162:105859. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105859.

- FitzGerald JM, Barnes PJ, Chipps BE, Jenkins CR, O’Byrne PM, Pavord ID, Reddel HK. The burden of exacerbations in mild asthma: a systematic review. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(3):00359-2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.

- Baptist AP, Hao W, Song PX, Carpenter L, Steinberg J, Cardozo LJ. A behavioral intervention can decrease asthma exacerbations in older adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(3):248–253.e3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2019.12.015.

- Kankaanranta H, Kauppi P, Tuomisto LE, Ilmarinen P. Emerging comorbidities in adult asthma: risks, clinical associations, and mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:3690628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3690628.

- Bardin PG, Rangaswamy J, Yo SW. Managing comorbid conditions in severe asthma. Med J Aust. 2018;209(S2):S11–S17. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja18.00196.

- Engelkes M, Janssens HM, de Jongste JC, Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(2):396–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00075614.

- Normansell R, Kew KM, Stovold E. Interventions to improve adherence to inhaled steroids for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD012226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012226.pub2.

- Arora P, Kumar L, Vohra V, Sarin R, Jaiswal A, Puri MM, Rathee D, Chakraborty P. Evaluating the technique of using inhalation device in COPD and bronchial asthma patients. Respir Med. 2014;108(7):992–998. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2014.04.021.

- Roman-Rodriguez M, Metting E, Gacia-Pardo M, Kocks J, van der Molen T. Wrong inhalation technique is associated to poor asthma clinical outcomes. Is there room for improvement? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019;25(1):18–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mcp.0000000000000540.

- Boulet LP, Boulay ME, Gauthier G, Battisti L, Chabot V, Beauchesne MF, Villeneuve D, Cote P. Benefits of an asthma education program provided at primary care sites on asthma outcomes. Respir Med. 2015;109(8):991–1000. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2015.05.004.

- Herman E, Beavers S, Hamlin B, Thaker K. Is it time for a patient-centered quality measure of asthma control?J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1771–1777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.016.

- Arellano FM, Arana A, Wentworth CE, Vidaurre CF, Chipps BE. Prescription patterns for asthma medications in children and adolescents with health care insurance in the United States. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22(5):469–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01121.x.

- Butler MG, Zhou EH, Zhang F, Wu YT, Wu AC, Levenson MS, Wu P, Seymour S, Toh S, Iyer A, et al. Changing patterns of asthma medication use related to US Food and Drug Administration long-acting β2-agonist regulation from 2005-2011. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(3):710–717. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.057.

- Llanos JP, Bell CF, Packnett E, Thiel E, Irwin DE, Hahn B, Ortega H. Real-world characteristics and disease burden of patients with asthma prior to treatment initiation with mepolizumab or omalizumab: a retrospective cohort database study. J Asthma Allergy. 2019;12:43–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S189676.

- Korelitz JJ, Zito JM, Gavin NI, Masters MN, McNally D, Irwin DE, Kelleher K, Bethel J, Xu Y, Rubin J, et al. Asthma-related medication use among children in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(3):222–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)60446-2.

- Lagos JA, Marshall GD. Montelukast in the management of allergic rhinitis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(2):327–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.2.327.

- Dusser D, Montani D, Chanez P, de Blic J, Delacourt C, Deschildre A, Devillier P, Didier A, Leroyer C, Marguet C, et al. Mild asthma: an expert review on epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment recommendations. Allergy. 2007;62(6):591–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01394.x.

- Reddel HK, Busse WW, Pedersen S, Tan WC, Chen YZ, Jorup C, Lythgoe D, O’Byrne PM. Should recommendations about starting inhaled corticosteroid treatment for mild asthma be based on symptom frequency: a post-hoc efficacy analysis of the START study. Lancet. 2017;389(10065):157–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31399-X.

- Battaglia S, Benfante A, Spatafora M, Scichilone N. Asthma in the elderly: a different disease?Breathe (Sheff). 2016;12(1):18–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.002816.

- Wardzyńska A, Kubsik B, Kowalski ML. Comorbidities in elderly patients with asthma: association with control of the disease and concomitant treatment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(7):902–909. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12367.

- Gibson PG. Variability of blood eosinophils as a biomarker in asthma and COPD. Respirology. 2018;23(1):12–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13200.

- Lababidi HM, AlSowayigh OM, BinHowemel SF, AlReshaid KM, Alotaiq SA, Bahnassay AA. Refractory asthma phenotyping based on immunoglobulin E levels and eosinophilic counts: a real life study. Respir Med. 2019;158:55–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2019.10.003.

- Bostantzoglou C, Delimpoura V, Samitas K, Zervas E, Kanniess F, Gaga M. Clinical asthma phenotypes in the real world: opportunities and challenges. Breathe (Sheff). 2015;11(3):186–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.008115.

- Izquierdo-Dominguez A, Jauregui I, Del Cuvillo A, Montoro J, Davila I, Sastre J, Bartra J, Ferrer M, Alobid I, Mullol J, et al. Allergy rhinitis: similarities and differences between children and adults. Rhinology. 2017;55(4):326–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin17.074.

- Chapman KR, Hinds D, Piazza P, Raherison C, Gibbs M, Greulich T, Gaalswyk K, Lin J, Adachi M, Davis KJ. Physician perspectives on the burden and management of asthma in six countries: the Global Asthma Physician Survey (GAPS). BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0492-5.

- Hew M, Reddel HK. Integrated adherence monitoring for inhaler medications. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1045–1046. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.1289.

- Wachter RM, Judson TJ, Mourad M. Reimagining specialty consultation in the digital age: the potential role of targeted automatic electronic consultations. JAMA. 2019;322(5):399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.6607.

- Chipps BE, Lanier B, Milgrom H, Deschildre A, Hedlin G, Szefler SJ, Kattan M, Kianifard F, Ortiz B, Haselkorn T, et al. Omalizumab in children with uncontrolled allergic asthma: review of clinical trial and real-world experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1431–1444. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.002.