Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of three doses of glycopyrrolate metered dose inhaler (GP MDI) in patients with uncontrolled asthma despite treatment with inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonists (ICS/LABA) with or without tiotropium, to characterize the benefit of triple therapy.

Method

This phase II/III, double-blind study randomized patients to 24 weeks’ treatment with twice-daily GP MDI 36 µg, 18 µg, 9 µg, or placebo MDI (all delivered via Aerosphere inhalers), or once-daily open-label tiotropium 2.5 µg. Patients continued their own ICS/LABA regimen throughout the study. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) area under the curve from 0 − 4 h (AUC0 − 4) at Week 24. Secondary endpoints included patient questionnaires to measure asthma control or symptoms. Safety was also assessed.

Results

The primary analysis (modified intent-to-treat) population included 1066 patients. The primary study endpoint was not met (changes from baseline in FEV1 AUC0 − 4 at Week 24 were 294 mL, 284 mL, 308 mL, 240 mL, and 347 mL for GP MDI 36 µg, GP MDI 18 µg, GP MDI 9 µg, placebo, and open-label tiotropium, respectively). There were no significant differences between treatment and placebo in secondary endpoints at Week 24. Post-hoc analyses using post-bronchodilator FEV1 as the baseline measurement, or averaging values across multiple baseline visits, showed a dose-related response to GP MDI. The incidence of adverse events was low and similar across treatments.

Conclusion

Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, post hoc analyses identified a dose-related response to GP MDI when alternative definitions of baseline FEV1 were used in the analyses.

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation and defined by symptoms including wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough, together with variable expiratory airflow obstruction. These may vary over time and in intensity, often triggered by factors such as exercise, allergens, or exposure to irritants, and patients may experience exacerbations that can be life-threatening (Citation1). The long-term goals of asthma management include maintaining symptom control and normal activity levels and minimizing the risk of exacerbations and persistent airflow limitation (Citation1).

Current guidelines recommend a stepwise approach to the management of asthma, with the mainstay of therapy being an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) alone or in combination with a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) (Citation1). Nonetheless, asthma remains difficult to control for many patients despite medium or high-dose ICS/LABA treatment (Citation2,Citation3). For such patients, add-on treatments may be considered, including long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) (Citation1,Citation4). In this regard, triple therapy with an ICS/LAMA/LABA has been shown to improve airflow and reduce exacerbations compared with ICS/LABA therapy alone (Citation1,Citation5–8).

The LAMA tiotropium has been demonstrated to improve lung function (Citation5–7) and reduce exacerbations (Citation7) as an add-on treatment in patients with poorly controlled asthma, despite treatment with ICS/LABA therapy. More recently, two randomized, controlled phase III trials showed improved lung function and reduced exacerbations with the LAMA glycopyrrolate, administered as a component of single-inhaler triple therapy to patients with uncontrolled asthma (Citation8). Final results are pending from further phase III asthma triple therapy studies, including glycopyrrolate (NCT02571777; clinicaltrials.gov) and another LAMA, umeclidinium (NCT02924688; clinicaltrials.gov).

Dose-ranging of an innovative formulation of glycopyrrolate (GP MDI; using co-suspension delivery technology to facilitate consistent dose delivery via the metered dose Aerosphere inhaler (Citation9,Citation10)) has been fully characterized in extensive phase II (Citation11–13) and phase III (Citation14–16) programs in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as well as a 14-day phase II study in patients with intermittent or mild-to-moderate uncontrolled asthma (Citation17). A further phase III program evaluating the safety and efficacy of GP as a component of fixed-dose triple therapy in patients with COPD has demonstrated improvements in lung function and reductions in exacerbations (Citation18,Citation19).

Further information is required to characterize the benefits of LAMA treatments in the management of asthma when used in combination with other controller medications (Citation20,Citation21). Therefore, this phase II/III study was performed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and dose-response of three doses of GP MDI compared with placebo MDI and open-label tiotropium over 24 weeks in patients with sub-optimally controlled asthma despite treatment with ICS/LABA therapy, with or without tiotropium.

Material and methods

Study design

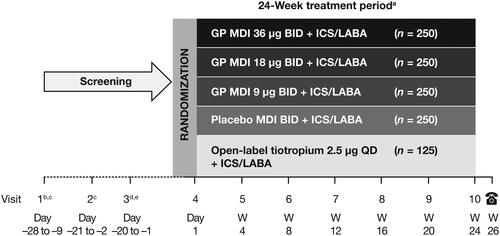

This phase II/III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group multicenter study (NCT03358147) was conducted at 249 sites in the USA from December 2017 to September 2019. Patients were randomized 2:2:2:2:1 using an interactive web response system to one of the following treatments for 24 weeks: GP MDI 36 µg twice daily (BID), GP MDI 18 µg BID, GP MDI 9 µg BID, placebo MDI BID (all delivered via Aerosphere inhalers), or open-label tiotropium inhalation spray 2.5 µg once daily (QD) (Spiriva® Respimat®) (). Tiotropium 2.5 µg QD is the dose approved in the USA for asthma (Citation22). All doses represent the sum of two actuations. Randomization was stratified by baseline percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (≤60% or >60%), reversibility to ipratropium (<12% or <200 mL versus ≥12% and ≥200 mL improvement in FEV1), and the ICS included in their ICS/LABA combination (budesonide, mometasone furoate, fluticasone furoate or fluticasone propionate).

Figure 1. Study design.

All patients were on a fixed combination ICS/LABA during screening and throughout the study.

aGP MDI and placebo MDI treatments were double-blind; tiotropium was open-label.

bFor patients receiving tiotropium at study entry, tiotropium was discontinued and replaced with ipratropium.

cPatients were required to demonstrate reversibility to salbutamol at either Visit 1 or Visit 2 for study eligibility.

dReversibility to ipratropium was assessed for characterization and stratification only.

eHolter monitors were placed at Visits 3 and 7 and removed the following day.

BID = twice-daily; GP = glycopyrrolate; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-agonist; MDI = metered dose inhaler; QD = once daily; W = week.

Patients continued on their own fixed-dose ICS/LABA regimen throughout the screening and treatment periods, and also received salbutamol for rescue use as needed. Patients who were receiving tiotropium discontinued its use at the start of screening (Visit 1) and replaced it with ipratropium, taken four times daily during the screening period. Ipratropium was discontinued at randomization.

Following randomization, the study included a further six visits. Visits were scheduled to occur approximately 12 hours (for twice-daily formulations) or 24 hours (for once-daily formulations) following ICS/LABA dosing. Post-dose spirometry was conducted following study drug and ICS/LABA administration. Patients received training regarding the use of their assigned device (MDI or Spiriva® Respimat®) at each visit. Patients recorded the time of study drug administration in an eDiary twice-daily throughout the study. Percent adherence was defined as the total number of puffs of study treatment taken on a study day/total number expected, averaged across all days of a patient’s dosing × 100.

A subset of patients participated in a 24-hour Holter monitor sub-study, for which data were collected at baseline and Week 12. Patients with clinically significant abnormal findings at baseline were excluded from the full study.

The study protocol was approved by Advarra (formerly Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board) and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation/Good Clinical Practice, and applicable regulatory requirements.

Patients

Eligible patients were 12–80 years of age with a body mass index of <40 kg/m2 and a documented history of physician-diagnosed asthma. Patients must have been on a stable ICS/LABA regimen ± tiotropium (2.5 µg QD) for ≥4 weeks prior to enrollment. Other eligibility criteria included: Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)-5 total score ≥1.5 at screening Visit 2; pre-bronchodilator FEV1 40–85% of predicted normal value (PN) for patients ≥18 years of age (40–90% for those <18 years of age) at Visits 1, 2 and 4; reversibility to salbutamol of ≥12% and ≥200 mL at Visit 1 or 2; demonstration of correct MDI administration technique. All patients (or parents/guardians for those <18 years of age) provided signed, written informed consent and/or assent.

Patients were excluded if they: received oral corticosteroids within 4 weeks, or any biologic agent within 3 months (or five half-lives, whichever is longer), of study initiation, were current smokers, or former smokers if they stopped smoking <6 months previously, or had >10 pack-years’ history, had life-threatening asthma, an upper respiratory infection not resolved within 7 days or hospitalizations for asthma within 3 months of study initiation, or had historical or current evidence of a clinically significant uncontrolled disease that could put the patient at risk through participation, or affect the efficacy or safety analysis if the disease/condition exacerbated during the study.

Efficacy endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in FEV1 area under the curve from 0–4 hours post-dose (AUC0 − 4) at Week 24. Secondary endpoints included: change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 at Week 24; the rate of moderate/severe asthma exacerbations, and change from baseline in ACQ-5, ACQ-7, and the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire for 12 Years and Older (AQLQ + 12) at Week 24.

Post hoc analyses were carried out to evaluate FEV1 AUC0–4 and change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks using the highest post-bronchodilator FEV1 value (post-salbutamol at Visit 1 or Visit 2) or an average of pre-bronchodilator FEV1 at screening Visits 3 and 4 as the baseline measurement, to reduce the impact of variability across pre-randomization visits.

Pulmonary function testing

Pulmonary function tests to measure FEV1 were performed in accordance with American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria (Citation23), using a spirometer that met or exceeded ATS minimum performance recommendations. Spirometry was carried out on Day 1 of the treatment period (Visit 4), at Week 12 and Week 24 (or discontinuation) 60 and 30 minutes prior to study drug and ICS/LABA administration and at 15 and 30 minutes and 1, 2, and 4 hours post-dosing with study drug and ICS/LABA. At Weeks 4, 8, 16, and 20, spirometry was carried out 60 and 30 minutes prior to study drug and ICS/LABA administration. The mean of the 30- and 60-minute pre-dose values on Day 1 was used as the baseline for all the protocol-specified analyses.

Assessment of exacerbations

Patients were provided with an eDiary for recording the use of rescue salbutamol and asthma symptoms of cough, wheeze, shortness of breath, and chest tightness every morning and evening throughout the study. Symptoms were rated using a single score for all; daytime symptoms were rated between 0 (none during the day) and 5 (‘so severe that I could not work or perform daily activities’); night-time symptoms were rated between 0 (none during the night) to 4 (‘so severe that I did not sleep at all’). Patients also received a peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) meter to measure their morning and evening PEFR, which was automatically transmitted to their eDiary. Signs of potential asthma exacerbations (decreases from baseline in PEFR, increases in salbutamol use, and/or increases in asthma symptom scores) were monitored. If any of these parameters met the pre-defined threshold for a moderate asthma exacerbation, the eDiary would generate an alert to the patient and the site, intended to stimulate contact to assess the status of the patient’s asthma.

Assessment of asthma control

Patients completed ACQ questionnaires at Visit 2 during screening, at baseline (Day 1), and every 4 weeks during the treatment period. ACQ-5 measures five symptoms (woken at night by symptoms, wake in the morning with symptoms, limitation of daily activities, shortness of breath, and wheeze); ACQ-7 includes these five symptoms plus daily rescue medication use recall and airway caliber, as measured by pre-bronchodilator FEV1 percent-predicted. Each question is scored from 0 (no impairment) to 6 (maximum impairment); the ACQ score is the mean of the item responses, ranging from 0 (totally controlled) to 6 (severely uncontrolled). The AQLQ + 12, which measures functional problems most troublesome to adults and adolescents with asthma, was completed at baseline (Day 1) and every 4 weeks during the treatment period. Patients rated each of the 32 items across four domains from 7 (no impairment) to 1 (severe impairment); the mean of all responses provided the overall score.

Safety assessments

Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs), physical examinations, clinical laboratory variables, vital signs, and 12-lead safety electrocardiograms. Cardiovascular safety was assessed in the 24-hour Holter monitoring sub-study, with a primary endpoint of change from baseline in mean heart rate over 24 hours.

Statistical analyses

It was calculated that a sample size of 1125 patients (250 per double-blind treatment group; 125 in the open-label tiotropium treatment group) would provide approximately 93% power to detect a 120 mL difference between the GP MDI treatment groups and placebo MDI in the analysis of the primary endpoint, with a two-sided alpha for each pairwise comparison of 0.05. Comparisons of GP MDI to open-label tiotropium were focused on estimation as the study was not powered to demonstrate non-inferiority or superiority. For the secondary endpoint of change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 at Week 24, it was assumed that the study would have 80% power to detect a difference of 90 mL for GP MDI versus placebo MDI. Expected treatment differences were based on a previous study of GP MDI (Citation17).

Efficacy analyses were carried out on the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, defined as patients with post-randomization data obtained prior to treatment discontinuation. Any data collected after completion of or discontinuation from randomized study medication was excluded from the mITT population analyses. The safety population comprised patients who were randomized and received any amount of study treatment. Those in the Holter monitoring analysis set must have had ≥18 hours of acceptable quality Holter monitoring data at Holter Baseline (Visit 3) and Week 12.

The primary endpoint, change from baseline in FEV1 AUC0 − 4, and the secondary endpoint, change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1, were analyzed using a linear repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. This included treatment, visit, ICS in the background fixed-dose ICS/LABA combination product, and treatment-by-visit interaction as categorical covariates and baseline FEV1, percentage reversibility to ipratropium, and the logarithm of baseline blood eosinophil count (average of non-missing values from Visit 1 and Visit 4) as continuous covariates. An unstructured variance–covariance matrix was fit. The same statistical models were used for the post hoc analyses, though the baseline definitions were changed (as described earlier). The annualized rate of moderate/severe asthma exacerbations was analyzed with negative binomial regression. Changes from baseline in ACQ-5, ACQ-7, and AQLQ were analyzed using ANCOVA models similar to those for the lung function endpoints. Data analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4.

Primary analysis testing was conducted in descending dose order, with the highest dose of GP MDI tested against placebo MDI at the nominal alpha (two-sided 0.05). Testing continued through the GP MDI doses as long as the results were successful, stopping if any comparison of GP MDI versus placebo MDI failed to meet statistical significance. Thus, any subsequent comparisons lower in the hierarchy with an unadjusted p-value <0.05 are referred to as ‘nominally’ significant. The secondary analyses for each dose of GP MDI versus placebo MDI proceeded only if the primary analysis for that GP MDI dose was successful. The Type I error rate within the secondary analyses of each GP MDI dose versus placebo MDI was controlled with a combination of sequential testing and the Hochberg procedure.

Results

Patients

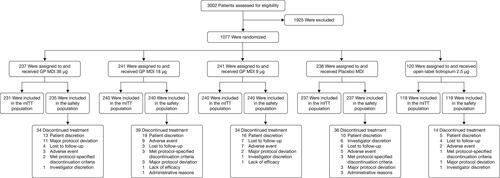

In total, 1077 patients were randomized and received treatment; 1066 patients were included in the mITT population (). Overall, 917 patients (85.1%) completed 24 weeks of treatment (GP MDI 36 µg, 85.7%; GP MDI 18 µg, 83.8%; GP MDI 9 µg, 85.5%; placebo MDI, 84.5%; and open-label tiotropium 87.5%) and 953 patients (88.5%) completed the study (GP MDI 36 µg, 89.5%; GP MDI 18 µg, 86.3%; GP MDI 9 µg, 89.2%; placebo MDI, 88.2%; and open-label tiotropium 90.0%).

Figure 2. Patient disposition.

Eight individuals participated in the study twice. Of these, three individuals (with a total of n = 6 sets of data) were excluded from the mITT and safety populations as they had overlapping study drug exposure in the study. The other five individuals (with n = 10 sets of data) participated in the study twice in separate instances and the data from the second instance was excluded from the mITT population analyses.

GP = glycopyrrolate; ITT = intent-to-treat; MDI = metered dose inhaler; mITT = modified intent-to-treat.

Demographic characteristics were balanced across the treatment arms (); overall, the mean age was 47.7 years, and 35 patients were 12 − 18 years of age (3.3%). The mean baseline FEV1 was 2.0 L (or 64.4% of PN), with 33.5% of patients having FEV1 ≤60% PN, and the mean reversibility to salbutamol was 25.4%. The majority of patients did not use tiotropium at screening (97.5%); 79.3% were Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) classification 4 or 5, and 6.1% had FEV1 >80% PN at randomization (Visit 4). Overall, 17.3% of patients reported one severe asthma exacerbation in the previous year, and 5.7% reported two or more severe exacerbations.

Table 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics (mITT population).

Efficacy

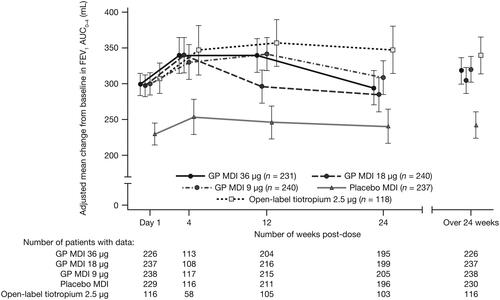

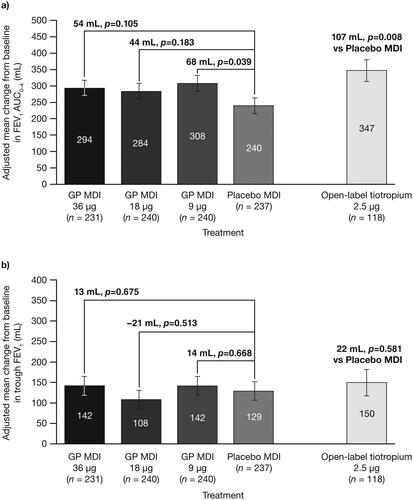

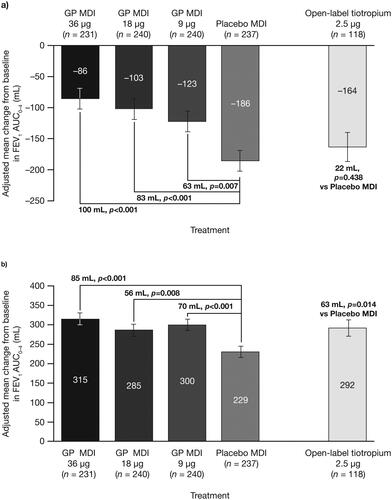

For the primary endpoint, there were no statistically significant differences for GP MDI 36 µg or 18 µg versus placebo in change from baseline in FEV1 AUC0–4 at Week 24, although nominally significant (p < 0.05) differences versus placebo were observed for the lowest dose of GP MDI (9 µg) and open-label tiotropium ( and Citation4a). There were nominally significant improvements in FEV1 AUC0–4 for all GP doses versus placebo at Day 1, Week 4, and over 24 weeks ().

Figure 3. Change from baseline in FEV1 AUC0–4 over the study period with study treatment plus ICS/LABA (mITT population).

Error bars represent the standard error.

AUC0–4 = area under the curve from 0–4 hours; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GP = glycopyrrolate; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-antagonist; MDI = metered dose inhaler; mITT = modified intent-to-treat.

There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatments versus placebo in the secondary endpoint of change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 at Week 24 ().

Figure 4. Change from baseline in a) FEV1 AUC0–4 at Week 24 and b) morning pre-dose trough FEV1 at Week 24, with study treatment plus ICS/LABA (mITT population).

Error bars represent the standard error.

AUC0–4 = area under the curve from 0–4 hours; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GP = glycopyrrolate; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-antagonist; MDI = metered dose inhaler; mITT = modified intent-to-treat.

There were no appreciable differences for any of the treatments versus placebo in change from baseline in ACQ-7 scores at Week 24 (least squares mean [standard error] changes from baseline of −0.78 [0.057], –0.73 [0.057], –0.90 [0.056], –0.90 [0.080] and –0.80 [0.057] for GP MDI 36 µg, 18 µg, 9 µg, open-label tiotropium, and placebo, respectively; all p-values not significant versus placebo). Similar findings were noted for ACQ-5 and AQLQ + 12 ().

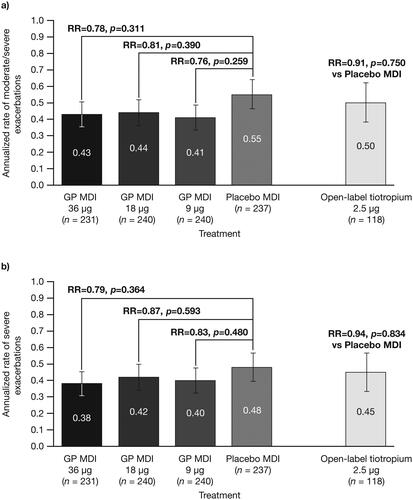

Trends for an exacerbation benefit with GP MDI were observed at all doses, for both moderate/severe exacerbations and severe exacerbations only ().

Figure 5. Annualized (adjusted) rate of a) moderate/severe asthma exacerbations and b) severe asthma exacerbations, with study treatment plus ICS/LABA (mITT population).

Error bars represent the standard error. Treatments are compared adjusting for baseline post-salbutamol FEV1% predicted, baseline severe asthma exacerbations history, the logarithm of baseline blood eosinophil count, background ICS/LABA, and percent reversibility to ipratropium using negative binomial regression. Time at risk of experiencing an exacerbation was used as an offset variable in the model.

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GP = glycopyrrolate; m/s = moderate/severe; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-antagonist; MDI = metered dose inhaler; mITT = modified intent-to-treat; RR = rate ratio.

Post hoc analyses of lung function

Given the unexpected findings for the primary analyses, post hoc analyses were conducted to determine possible explanations. One factor that was found to influence the results was baseline FEV1 variability. Changes in pre-bronchodilator trough FEV1 were observed over the screening period between Visits 1 to 4 (see ). The greatest mean difference in FEV1 between Visit 3 and baseline (Visit 4) was observed in patients later randomized to the open-label tiotropium arm (−100 mL), and the smallest difference was observed in those later randomized to the GP MDI 36 μg arm (−7 mL). Given the size of the observed difference across the groups, we conducted post hoc analyses with alternative definitions of baseline FEV1 to determine the effects of this baseline variability on the findings. These analyses estimated effects over 24 weeks, rather than at Week 24, to reduce the variation present at any single time point.

Firstly, we conducted a post hoc analysis using the largest post-bronchodilator FEV1 during screening (as assessed at either Visit 1 or 2) as the baseline assessment (instead of pre-dose trough FEV1 at Visit 4) to compare the treatment effects to the benefits observed following salbutamol administration. In this analysis, the change in FEV1 AUC0–4 over 24 weeks was shown to be nominally significant versus placebo for all GP doses, with a clear dose-response being observed (). Similarly, there was a nominally significant improvement for GP MDI 36 μg versus placebo in change from baseline in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks using post-bronchodilator FEV1 as the baseline assessment (p = 0.006; ).

Figure 6. Change in FEV1 AUC0–4 over 24 weeks, a) using post-bronchodilator FEV1 as baseline value and b) averaging pre-bronchodilator FEV1 assessments from pre-randomization Visits 3 and 4 to give baseline FEV1 value, with study treatment plus ICS/LABA (mITT population).

Error bars represent the standard error. In panel a), less negative values are indicative of a greater treatment benefit.

AUC0–4 = area under the curve from 0–4 hours; GP = glycopyrrolate; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-antagonist; MDI = metered dose inhaler; mITT = modified intent-to-treat.

Table 2. Summary of TEAEs with study treatment plus ICS/LABA (safety population).

Averaging the pre-bronchodilator FEV1 assessments at Visits 3 and 4 to give a baseline FEV1 value, as an alternative way to address variability in baseline FEV1 during screening, also demonstrated a clearer dose-response. Again, the change in FEV1 AUC0–4 over 24 weeks was shown to be nominally significant versus placebo for all GP doses, with the largest treatment effect for GP MDI 36 µg ().

Safety

The mean number of days of study drug exposure was generally similar across groups (range: 153.9–157.1 days). Across the GP MDI and placebo MDI groups, 72.3–74.2% of patients had 80–100% adherence and <1% of patients had >100% adherence. In the tiotropium group, 53.8% of patients had 80–100% adherence, 10.1% had 100–120% adherence and 26.1% had >120% adherence.

The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) in the safety population was low and similar across treatments, with no dose-related trends (). The most frequently reported TEAEs were upper respiratory tract infection (6.3%; range across treatment groups: 5.0–8.0%), nasopharyngitis (4.9%; range: 1.7–7.1%) and sinusitis (2.9%; range: 1.3–5.9%). Seven patients discontinued from the study due to serious TEAEs (asthma exacerbations [n = 2 patients], suicidal ideation, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute respiratory failure, and acute cerebrovascular accident [all n = 1]); none were considered treatment-related. There were no deaths during the study.

Cardiovascular safety of the three doses of GP MDI, assessed via 24-hour Holter monitoring, was comparable to that of placebo and open-label tiotropium (Supplementary Table S3). For the primary Holter monitoring endpoint, least squares mean changes from baseline in 24-hour mean heart rate at Week 12 were small across each of the GP MDI groups (−0.4 to −0.1 bpm) and the placebo group (−1.1 bpm). Similarly, there were no meaningful treatment differences in secondary Holter monitoring endpoints.

Discussion

In a broad population of patients with uncontrolled asthma despite treatment with ICS/LABA (with or without tiotropium), this study did not meet the primary endpoint of FEV1 AUC0–4 at Week 24 or the secondary endpoint of trough FEV1 at Week 24, with no dose-response observed. These results are unexpected given that previous studies have shown a benefit of adding a LAMA to an ICS/LABA in patients with uncontrolled asthma (Citation6–8). Also, a previous phase II study of GP MDI in mild-to-moderate asthma demonstrated dose-ordering of treatment effects with and without concurrent ICS treatment (Citation17). Indeed, in the current study, tiotropium showed a nominally significant improvement in lung function versus placebo at Week 24; however, we observed evidence of overuse in this open-label treatment arm, which may have affected the results in this group. In the tiotropium group, 26.1% of patients had >120% adherence (compared with 0–0.4% across the remaining treatment arms), which could be attributed to the treatment being open-label or some patients using it twice-daily (as is common for other inhalers) rather than once-daily.

One of the reasons that the current study did not meet the primary endpoint may relate to the patient population enrolled, which included a considerable proportion with only a mild degree of lung function impairment (approximately two-thirds had a baseline mean FEV1 >60% predicted), for whom the capacity for improvement in lung function is reduced relative to those with greater lung function impairment. Furthermore, ‘baseline’ measurements for pulmonary function and symptom control were made at Visit 4, up to 28 days into the study run-in; however, we observed improvements in these efficacy measures during the run-in period, suggesting that, for some patients, there was little room for additional improvement. There were no stability criteria for FEV1 in our study, and indeed variability in lung function is a hallmark of asthma (Citation1,Citation24), which is likely to have contributed to the unexpected results.

Therefore, post hoc analyses were carried out to evaluate the impact of these factors and model likely findings over 24 weeks with a more stable baseline. By analyzing the data over 24 weeks, the variation present at a single time point could be reduced. We investigated two alternative definitions of baseline FEV1 to reduce variability in the baseline measurements: using post-bronchodilator FEV1 and taking the mean of pre-bronchodilator FEV1 from Visits 3 and 4.

Our post hoc results using both these alternative methods demonstrated evidence of a dose-response over 24 weeks, the largest treatment effect being observed with GP MDI 36 µg. Furthermore, GP MDI showed improvements in post-bronchodilator FEV1 over 24 weeks that were comparable with tiotropium, which is consistent with the known efficacy of these drugs in asthma (Citation8).

Another important goal in the treatment of asthma is the reduction of exacerbation risk, and so the observation of a trend toward an exacerbation benefit with all GP MDI doses in our study is interesting. The phase III trials showing an effect of triple therapy in reducing asthma exacerbations only included patients with ≥1 exacerbation during the previous year (Citation8); the majority of patients (77%) in the current study had no history of exacerbations, so the trend of a positive effect for this endpoint warrants further investigation.

Overall, GP MDI was well tolerated, in line with the previously published study in asthma patients (Citation17); no new safety signals were identified, including cardiovascular safety evaluated by Holter monitoring. Data from studies of GP (as a component of triple therapy) for the treatment of patients with COPD, who are typically more frail and at higher risk of cardiac disease, further support the safety of GP MDI (Citation18,Citation19).

A strength of this study is that it was carried out in a broad population of patients with asthma; however, a key limitation is that patients used multiple devices and dosing regimens, which likely impacted adherence with randomized treatment regimens and potentially affected the study outcome. Furthermore, as patients demonstrated significant variability during the screening/run-in period, the sensitivity of the study to see further post-randomization improvements in FEV1 was reduced. Lastly, the trend toward a reduction in exacerbations was interesting, particularly because the treatment effect was comparable to those seen with the LAMA class (Citation7,Citation8) even though the study did not enrich for patients prone to exacerbations and did not extend out to 52 weeks. However, definitive evidence for the efficacy of GP in asthma, including benefits on exacerbations and lung function, will be provided in two variable-length phase III studies (24–52 week) of budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate fixed-dose combination triple therapy (the KALOS (Citation25) and LOGOS (Citation26) studies) in more than 5000 patients with uncontrolled asthma.

Conclusions

In a broad asthma population treated with ICS/LABA, this study of GP MDI delivered using the Aerosphere inhaler did not show any benefit over placebo for the primary endpoint, possibly due to variability of baseline lung function values. However, post hoc analyses to mitigate the potential impact of baseline variability suggest a clear dose-response of GP MDI. Further investigation is warranted in phase III trials in patients with uncontrolled asthma.

Support statement

This study was funded by AstraZeneca.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (146.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Lindsey O’Mahony, PhD, on behalf of CMC Connect, McCann Health Medical Communications, funded by AstraZeneca in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Declaration of interest

E. Kerwin has participated in consulting, advisory boards, and speaker panels for, or has received travel reimbursement from, Amphastar, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Mylan, Novartis, Oriel, Sunovion, Teva, and Theravance. P. Dorinsky, M. Patel, P. Darken, D. Griffis, and H. Fjällbrant are employees of AstraZeneca. K. Rossman, C. Reisner, and A. Maes are former employees of AstraZeneca.

Data availability

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. 2020. Report: global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/.

- Aalbers R, Park HS. Positioning of long-acting muscarinic antagonists in the management of asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9(5):386–393. doi:https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2017.9.5.386.

- Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24(1):1–10.

- Cazzola M, Rogliani P, Matera MG. The latest on the role of LAMAs in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(6):1288–1291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.014.

- Fardon T, Haggart K, Lee DK, Lipworth BJ. A proof of concept study to evaluate stepping down the dose of fluticasone in combination with salmeterol and tiotropium in severe persistent asthma. Respir Med. 2007;101(6):1218–1228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.11.001.

- Kerstjens HAM, Disse B, Schröder-Babo W, Bantje TA, Gahlemann M, Sigmund R, Engel M, van Noord JA. Tiotropium improves lung function in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(2):308–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.039.

- Kerstjens HAM, Engel M, Dahl R, Paggiaro P, Beck E, Vandewalker M, Sigmund R, Seibold W, Moroni-Zentgraf P, Bateman ED, et al. Tiotropium in asthma poorly controlled with standard combination therapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1198–1207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1208606.

- Virchow JC, Kuna P, Paggiaro P, Papi A, Singh D, Corre S, Zuccaro F, Vele A, Kots M, Georges G, et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy in uncontrolled asthma (TRIMARAN and TRIGGER): two double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394(10210):1737–1749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32215-9.

- Vehring R, Lechuga-Ballesteros D, Joshi V, Noga B, Dwivedi SK. Cosuspensions of microcrystals and engineered microparticles for uniform and efficient delivery of respiratory therapeutics from pressurized metered dose inhalers. Langmuir. 2012;28(42):15015–15023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la302281n.

- Doty A, Schroeder J, Vang K, Sommerville M, Taylor M, Flynn B, Lechuga-Ballesteros D, Mack P. Drug delivery from an innovative LAMA/LABA co-suspension delivery technology fixed-dose combination MDI: evidence of consistency, robustness, and reliability. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018;19(2):837–844. doi:https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-017-0891-1.

- Fabbri LM, Kerwin EM, Spangenthal S, Ferguson GT, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Pearle J, Sethi S, Orevillo C, Darken P, St. Rose E, et al. Dose-response to inhaled glycopyrrolate delivered with a novel Co-Suspension™ Delivery Technology metered dose inhaler (MDI) in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0426-4.

- Reisner C, Fabbri LM, Kerwin EM, Fogarty C, Spangenthal S, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, Martinez FJ, Donohue JF, Darken P, et al. A randomized, seven-day study to assess the efficacy and safety of a glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate fixed-dose combination metered dose inhaler using novel Co-Suspension™ Delivery Technology in patients with moderate-to-very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0491-8.

- Rabe KF. GFF MDI for the improvement of lung function in COPD - a look at the PINNACLE-1 and PINNACLE-2 data and beyond. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(7):685–698. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2017.1320218.

- Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, Fabbri LM, Rennard S, Feldman GJ, Sethi S, Spangenthal S, Gottschlich GM, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Efficacy and safety of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler formulated using co-suspension delivery technology in patients with COPD. Chest. 2017;151(2):340–357. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.028.

- Hanania NA, Tashkin DP, Kerwin EM, Donohue JF, Denenberg M, O’Donnell DE, Quinn D, Siddiqui S, Orevillo C, Maes A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler using novel Co-Suspension™ Delivery Technology in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2017;126:105–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2017.03.015.

- Lipworth BJ, Collier DJ, Gon Y, Zhong N, Nishi K, Chen R, Arora S, Maes A, Siddiqui S, Reisner C, et al. Improved lung function and patient-reported outcomes with co-suspension delivery technology glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler in COPD: a randomized Phase III study conducted in Asia, Europe, and the USA. Int J Chronic Obstructive Pulm Dis. 2018;13:2969–2984. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S171835.

- Kerwin E, Wachtel A, Sher L, Nyberg J, Darken P, Siddiqui S, Duncan EA, Reisner C, Dorinsky P. Efficacy, safety, and dose response of glycopyrronium administered by metered dose inhaler using co-suspension delivery technology in subjects with intermittent or mild-to-moderate persistent asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Med. 2018;139:39–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.04.013.

- Ferguson GT, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Fabbri LM, Wang C, Ichinose M, Bourne E, Ballal S, Darken P, DeAngelis K, et al. Triple therapy with budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate with co-suspension delivery technology versus dual therapies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (KRONOS): a double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(10):747–758. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8.

- Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT, Wang C, Singh D, Wedzicha JA, Trivedi R, St. Rose E, Ballal S, McLaren J, et al. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-very-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):35–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916046.

- Cazzola M, Puxeddu E, Matera MG, Rogliani P. A potential role of triple therapy for asthma patients. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13(11):1079–1085. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2019.1657408.

- Sobieraj DM, Baker WL, Nguyen E, Weeda ER, Coleman CI, White CM, Lazarus SC, Blake KV, Lang JE. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting muscarinic antagonists with asthma control in patients with uncontrolled, persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1473–1484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2757.

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. Spiriva® Respimat® Prescribing Information. Last updated August. 2020. Available from: http://docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Spiriva%20Respimat/spirivarespimat.pdf.

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034805.

- Dean BW, Birnie EE, Whitmore GA, Vandemheen KL, Boulet L-P, FitzGerald JM, Ainslie M, Gupta S, Lemiere C, Field SK, et al. Between-visit variability in FEV1 as a diagnostic test for asthma in adults. Annals Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(9):1039–1046. doi:https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201803-211OC.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to assess PT010 in adult and adolescent participants with inadequately controlled asthma (KALOS). 2020. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04609878.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to assess PT010 in adult and adolescent participants with inadequately controlled asthma (LOGOS). 2020. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04609904.