Abstract

Objective

To assess asthma burden and medication adherence in a US de-identified patient level claims database.

Methods

This retrospective observational study used the IQVIA PHARMETRICS PLUS database to identify patients aged 5–17 years, diagnosed with asthma between 01/01/2012–09/30/2017 (asthma cohort), and those initiating treatment with twice-daily inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or twice-daily ICS/long-acting beta2 agonists (LABA) (treatment cohorts; index date = first dispensing). Patient characteristics, asthma medication, and healthcare resource utilization were assessed over a 12-month baseline period. Treatment cohort endpoints were assessed in a 12-month follow-up period, including: adherence using proportion of days covered (PDC); persistence (no gap >45 days between dispensings).

Results

The asthma cohort included 186,868 patients (112,689 children, mean age 7.9 years; 74,179 adolescents, mean age 14.3 years). During baseline, 34.5% used ICS or ICS/LABA, 24% used oral corticosteroids, 11.1% had ≥1 asthma-related emergency department visit, 2.2% had ≥1 asthma-related hospitalization. Among treatment cohorts, 47,276 and 10,247 patients initiated twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA, respectively (mean ages: 9.9; 12.5 years). Mean PDC adherence to twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA was 30% and 34% at 6 months (PDC ≥0.8: 4.3%; 6.1%); 21% and 24% at 12 months (PDC ≥0.8: 1.8%; 2.8%). Persistence with twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA was 10.1% and 14.2% at 6 months; 5.6% and 8.0% at 12 months.

Conclusions

A large disease burden and unmet need exist among US children/adolescent asthma patients, evidenced by low use of, and poor adherence to, ICS-containing medication, the notable proportion of oral corticosteroid users, and higher-than-expected asthma-related emergency department and hospitalization rates.

Introduction

Asthma affects >300 million people worldwide (Citation1) and is the most common chronic disease in children, with relatively high prevalence in North America (Citation2). The 2019 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported asthma prevalence to be 8.3% in children aged 5–11 years, and 8.6% in adolescents aged 12–17 years in 2019 (Citation3).

Pediatric asthma imposes a significant economic burden to the US healthcare system, with costs and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) significantly greater for children with asthma than without (Citation4). Inadequate adherence can result in uncontrolled asthma in children/adolescents (Citation5), associated with reduced lung function, impaired physical-exercise performance, and reduced quality of life (Citation6). Children with asthma are prone to severe viral-induced asthma exacerbations even when well-controlled clinically (Citation7).

Guidelines for troublesome asthma symptoms (i.e. symptoms most days or waking with asthma ≥once/week) recommend treatment with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) combination for children/adolescents (Citation8). Despite efforts to increase awareness of asthma and improve care (Citation8), childhood asthma underdiagnosis and undertreatment persist (Citation2). This can be attributed to the fact that children with asthma may have periods of time where they have little to no impairment (i.e. no symptoms, no need for rescue therapy for symptoms) and have preserved lung function (Citation9). However, children can have rapid and severe acute asthma episodes often resulting in a need for systemic corticosteroids, emergency department (ED) visits, and/or hospitalizations (Citation10). In contrast, adult asthma is characterized by more impairment (frequent 24-h symptoms, need for rescue therapy, impaired lung function), and fewer exacerbations (Citation11). Thus, there is a need to better understand and characterize the pediatric/adolescent asthma population, treatment patterns, and associated disease and economic burden in the US.

Adherence is a quality measure for asthma and an important endpoint for US payers/healthcare providers. While it is generally accepted that adherence to prescribed asthma therapy is poor among children/adolescents (Citation12), there is limited real-world information on adherence to once- vs. twice-daily maintenance medications among pediatric/adolescent asthma patients in the US. In this study, we assessed disease burden among asthma patients aged 5–17 years, and medication adherence of twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA users in a large US claims database.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This retrospective observational cohort study used medical and pharmacy claims data, which contained information on dispensed, not prescribed, medication from the IQVIA PHARMETRICS PLUS database between 01/01/2012–09/30/2017. The database contains fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims for more than 190 million unique enrollees, and is generally representative of the commercially insured US population aged <65 years with respect to age/gender distribution.

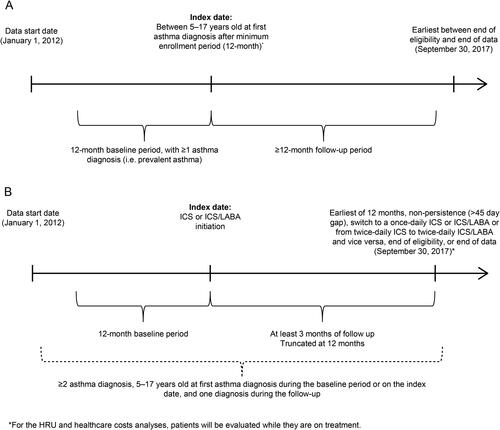

Claims data containing International Classification of Disease (ICD)-9 (493.xx) and ICD-10 (J45.3, J45.4, J45.5, J45.9) codes were used to identify asthma patients aged 5–17 years at index, analyzed in two cohorts by asthma and treatment. Asthma and treatment cohort study designs are shown in .

Figure 1. Study design scheme for (A) the asthma cohort and (B) the treatment cohorts. HRU, healthcare resource utilization; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting beta2 agonist.

The index date for the asthma cohort was the first asthma diagnosis after a minimum 12 months of continuous enrollment. The 12-month period pre-index was defined as the baseline period; patients in the asthma cohort also had ≥1 confirmatory asthma diagnosis during this period. The follow-up period spanned from the index until the earliest of end of eligibility or data availability. There were also two separate treatment cohorts that included children/adolescents with asthma who initiated (1) twice-daily ICS or (2) twice-daily ICS/LABA. The treatment cohorts’ index was the date of the first twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA dispensing. The baseline period was 12 months pre-index while the follow-up period spanned from the index to the earliest of 12 months, non-persistence (>45 day gap), switching to once-daily ICS or ICS/LABA or from twice-daily ICS to twice-daily ICS/LABA and vice versa, end of eligibility/data. Patients in the treatment cohorts had a minimum of 12 months enrollment pre- and ≥3 months post-index. Patients in the treatment cohorts had ≥2 diagnoses of asthma, with ≥1 asthma diagnosis during the baseline period or at index and ≥1 asthma diagnosis during the follow-up period.

If a patient was eligible to be included in both cohorts, they were included in both cohorts.

For both cohorts, patients with a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis or cystic fibrosis during the study period were excluded. Patients were also excluded (in the treatment cohorts only) if they had ≥1 ICS or ICS/LABA dispensing during the baseline period, for twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA cohorts, respectively.

Endpoints

Primary endpoints were evaluated during the follow-up period for the asthma and treatment cohorts (separately for the twice-daily ICS and twice-daily ICS/LABA cohorts). Primary endpoints included: treatment patterns (i.e. patients with ≥1 dispensing for asthma maintenance or rescue medication stratified by medication class), all-cause and asthma-related (any claim with a primary diagnosis of asthma) HRU and costs (stratified by inpatient, ED, and outpatient visits, and by index medication costs [twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA]), and asthma exacerbations (overall, and further stratified by moderate and severe). Moderate exacerbations required an asthma-related ED visit or outpatient visit with a systemic corticosteroid/oral corticosteroid (OCS) dispensing within ±5 days. Severe exacerbations required an asthma-related inpatient visit or ED visit resulting in an inpatient visit within +1 day. Patients with ≥2 exacerbations within 14 days of each other were considered as one exacerbation and classified according to the highest severity (Citation13,Citation14).

Secondary endpoints were evaluated among the treatment cohorts and included: treatment patterns for twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA; medication adherence to twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA (evaluated at 90, 180, 270, 365 days post-index) using mean proportion of days covered (PDC); proportion of patients achieving PDC ≥0.5 (less restrictive threshold for adherence) or ≥0.8 (adherent to medication); persistence to twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA (evaluated at 90, 180, 270, 365 days post-index); and time to treatment discontinuation. Discontinuation was defined as a gap of >45 days in days’ supply of medication (i.e. between the end of supply of one dispensing to the date of the following dispensing or the end of the follow-up period). Of note, all medications dispensed within the same twice-daily therapeutic class were considered interchangeable.

Data analysis

All primary endpoints were assessed descriptively, expressed as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Treatment patterns for asthma maintenance and rescue medication use were reported separately for the asthma and treatment cohorts. The number of dispensings, mean days of supply, and treatment duration (from the first to the last dispensing) for twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA were reported for the twice-daily treatment cohorts only. Rates of all-cause and asthma-related HRU per patient per year (PPPY) and per patient per month (PPPM) were calculated by dividing the number of visits over the follow-up period by the patient-years or patient-months of observation. All-cause and asthma-related healthcare costs were also reported as PPPY and PPPM; calculated by dividing the costs incurred over the follow-up period by the patient-years or patient-months of observation. The all-cause and asthma-related healthcare costs paid by patients included medical costs, pharmacy costs, and index medication costs. All costs were inflation adjusted to 2018 US dollars ($) based on the medical care component of the consumer price index.

Medication adherence was evaluated using PDC; calculated as the total number of days supplied by dispensings divided by the total number of days from the index to the end of the specified time interval (i.e. 90, 180, 270, and 365 days). The proportions of patients with PDC ≥0.5 and PDC ≥0.8 were also reported. Persistence to therapy was assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Kaplan-Meier persistence rates were evaluated at 90, 180, 270, and 365 days following treatment initiation.

Results

Asthma cohort

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

The asthma cohort included 186,868 patients (112,689 children [aged 5–11 years] and 74,179 adolescents [aged 12–17 years]). Baseline characteristics are shown in (additional information, Table 1, supplementary material). The mean age was 10.5 years and 40.4% of patients were female (children: 7.9 years and 37.8% were female; adolescents: 14.3 years and 44.3% were female). At baseline, 25.7% of patients used ICS (29.6% children; 19.7% adolescents), 8.8% used ICS/LABA (children: 6.4%; adolescents: 12.4%), 24.0% used OCS (defined as at least one dispensing of OCS during the baseline period; children: 26.6%; adolescents: 19.9%), 19.6% used leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA; children: 20.0%; adolescents: 19.0%), and 44.2% used short-acting beta2 agonists (SABA; children: 44.1%; adolescents: 44.4%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics: asthma cohort.a

Overall, 20.0% had ≥1 exacerbation (children: 22.8%; adolescents: 15.8%), 17.8% had ≥1 moderate exacerbation (children: 20.0%; adolescents: 14.3%), and 2.2% had ≥1 severe exacerbation (children: 2.8%; adolescents: 1.4%). Overall, 11.1% had ≥1 asthma-related ED visit (children: 12.6%; adolescents: 8.7%), and 2.2% had ≥1 asthma-related hospitalization (children: 2.7%; adolescents: 1.4%).

Follow-up endpoints

Treatment patterns during the follow-up period are shown in . The most commonly used maintenance medications were ICS in 30.3% of patients (children: 34.6%; adolescents: 23.8%) and LTRA in 24.6% of patients (children: 25.3%; adolescents: 23.4%), followed by ICS/LABA in 12.4% of patients (children: 10.2%; adolescents: 15.8%). Similar percentages of children and adolescents received rescue medications during the follow-up: 50.4% and 51.0%, respectively, received SABA; and 34.7% and 32.0%, respectively, were treated with OCS.

Table 2. Follow-up treatment patterns: asthma cohort.

Follow-up asthma-related HRU and healthcare costs are presented in . Inpatient visits were present in 2.5% of patients (children: 2.9%; adolescents: 1.9%), ED visits in 11.5% of patients (children: 12.8%; adolescents: 9.4%), and outpatient visits in 68.0% of patients (children: 71.2%; adolescents: 63.1%).

Table 3. Follow-up asthma-related HRU and healthcare costs: asthma cohort and treatment cohort.

Annualized PPPY mean asthma-related total costs in 2018 US$ were $521 overall: $525 for children and $517 for adolescents. Annualized PPPY mean asthma-related medical costs were: $60 for inpatient visits (children: $69; adolescents: $47), $24 for ED visits (children: $26; adolescents: $21), and $163 for outpatient visits (children: $151; adolescents: $182). PPPM costs are reported in the supplementary material.

Overall, 19.4% of patients had ≥1 exacerbation during follow-up (children: 21.8%; adolescents: 15.8%), 16.9% had ≥1 moderate exacerbation (children: 18.8%; adolescents: 13.9%), and 2.5% had ≥1 severe exacerbation (children: 3.0%; adolescents: 1.9%) (Table 2, supplementary material). The annualized rate of overall exacerbations was 0.148 in children and 0.098 in adolescents.

Treatment cohorts

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

Among treatment cohorts, 47,276 and 10,247 patients initiated twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA, respectively; their baseline characteristics are shown in (additional information, Table 3, supplementary material). For twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA cohorts, respectively, mean age was 9.9 and 12.5 years, and 43.9% and 48.2% were female. A high percentage of patients used SABA and OCS rescue medication: for twice-daily ICS patients, 65.4% and 38.9% received SABA and OCS, respectively; for twice-daily ICS/LABA users, 66.2% and 40.6% were treated with SABA and OCS, respectively. Asthma-related ED visits were reported in 7.9% of twice-daily ICS and 7.6% of ICS/LABA users. Asthma-related hospitalization was reported in 2.9% and 1.9% of twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA patients, respectively. Primary care providers were the most common prescribers (64.5% and 48.6% of twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA initiators, respectively) followed by respiratory specialists who treated 12.8% of new users of twice-daily ICS and 25.1% of twice-daily ICS/LABA.

Table 4. Baseline characteristics: treatment cohorts.

Follow-up endpoints

Follow-up treatment patterns are shown in ; in both twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA cohorts, 31.7% and 41.6%, respectively, of patients were also prescribed LTRA as maintenance medication at some time during the ≥3 (up to 12) months of follow up. In twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA cohorts, respectively, 80.4% and 74.4% of patients used SABA, and 41.2% and 39.6% used OCS. The mean [median] duration of treatment was 148.3 [89] days for twice-daily ICS, and 160.7 [119] days for twice-daily ICS/LABA. In the twice-daily ICS cohort, most patients were on medium dose ICS (50.1%) followed by low dose (36.6%) and high dose ICS (13.3%). Among the twice-daily ICS/LABA cohort, 45.7% of patients were on low dose ICS, 42.1% were on medium dose, and 12.2% were on high dose ICS.

Table 5. Follow-up treatment patterns: treatment cohorts.

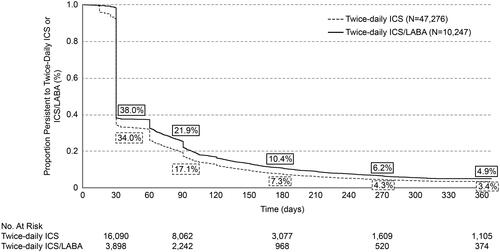

Mean PDC for twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA, respectively, was 30% and 34% at 6-months (PDC ≥0.8: 4.3% and 6.1%), and 21% and 24% at 12-months post-index (PDC ≥0.8: 1.8% and 2.8%) (). Persistence with twice daily ICS or ICS/LABA is shown in . Persistence with twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA, respectively, was 7.3% and 10.4% at 6-months, and 3.4% and 4.9% at 12-months post-index. Similar findings were observed in sensitivity analyses using different gaps (of >60 and >90 days) to define discontinuation (Figures 1 and 2, supplementary material).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier rates of persistencea to twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA. Notes: aNon-persistence (i.e. discontinuation) was defined as a gap of >45 days in days’ supply of medication (i.e. between the end of supply of one dispensing to the date of the following dispensing or the end of the follow-up period). ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting beta2 agonist.

Follow-up asthma-related HRU and healthcare costs are presented in . HRU was similar between twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA patients. Asthma-related outpatient visits were reported in 34.0% and 37.4% of twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA patients, respectively, and asthma-related ED visits in 1.4% and 1.3%, respectively. Annualized mean asthma-related costs were $1,365 for twice-daily ICS and $1,920 for twice-daily ICS/LABA users.

For twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA initiators, respectively, 5.8% and 7.6% had ≥1 exacerbation during follow-up, 4.9% and 6.5% had ≥1 moderate exacerbation, and 0.9% and 1.0% had ≥1 severe exacerbation (Table 4, supplementary material). The annualized rates of exacerbations were 0.078 for twice-daily ICS, and 0.110 for twice-daily ICS/LABA cohorts.

Discussion

The aim of this retrospective observational study was to investigate patient characteristics, treatment patterns, exacerbations, HRU, and healthcare costs among children/adolescents aged 5–17 years with asthma, and to examine medication adherence and persistence in patients prescribed twice-daily ICS and ICS/LABA. The real-world asthma burden was considerable among children and adolescents as particularly highlighted by high HRU. ICS-containing medication was under-used, with only 34.5% of asthma patients using either ICS or ICS/LABA at baseline. Among those initiating twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABA therapy, medication adherence and persistence was low, highlighting an unmet need among children and adolescents with asthma. In adults, similar mean PDC values have been reported previously (Citation15). Treatment with twice-daily ICS/LABA combination therapy in our study was associated with slightly higher adherence and persistence relative to ICS alone; patients may be more likely to take a medication with an immediate symptomatic benefit versus a medication which may have no perceivable effect for weeks (ICS only) (Citation15).

Achieving and maintaining asthma control is a key long-term goal of asthma treatment and management strategies (Citation8); the success of this, and achieving clinically significant benefits for patients, is impacted by adherence to prescribed treatments. Low adherence to maintenance medication is known to increase the risk of asthma exacerbations (Citation16). Poor treatment adherence in pediatric asthma is well documented (Citation12,Citation17,Citation18), especially among adolescents (Citation19). Reviews of pediatric asthma studies have reported that more than half of the clinical trials had adherence rates of ≤50% (Citation20), while in children, rates of adherence to maintenance medication were low (28–67%) (Citation21). Not only is poor adherence to maintenance medication common, it is also significantly associated with severe exacerbations in children (Citation18).

Childhood asthma is characterized by periods with little, if any, impairment and fluctuations in severity (Citation10,Citation19); this may make it hard for parents to be convinced that their child needs a daily medication and difficult for the child/adolescent who feels fine when well. Parents and patients may believe that the medication does not help if it does not have an immediate effect, or mistakenly think that maintenance medication can be taken intermittently when symptoms are noticeable (Citation22). Difficulties using inhalers, burdensome regimens, having to use multiple different inhalers, unaffordable medication co-payments, advice to stop treatment from healthcare providers, and lack of education on the importance of continuous adherence are also factors that may lead to poor adherence (Citation8).

While asthma control was not assessed in this study, we showed the significant risk children with asthma display, with need for OCS reaching 40% over a 1-year follow-up period. Controlled studies have demonstrated the relative paucity of asthma symptoms in children on placebo or ICS (Citation23,Citation24). In one study, children with mild persistent asthma had no symptoms and no need for rescue albuterol on 80–90% of the days studied, yet significantly more patients on placebo (49%) had an exacerbation requiring OCS therapy than those on low-dose daily ICS therapy (28%) (Citation23). Treatment failure (requiring a second OCS dose within 6 months) was significantly higher in the placebo group (23%) than in the low-dose ICS group (2.8%) (Citation23), demonstrating that even in children with low symptom frequency there is still a high risk for exacerbations, and also that low-dose ICS significantly reduces need for OCS therapy. In another study, children had a high percentage (71–79%) of symptom-free days, yet 15% had ≥1 exacerbation despite being on either LABA, LTRA, or ICS therapy (Citation24). Lung function has also been noted to be normal in children/adolescents with asthma (Citation23,Citation24) and with severe asthma (Citation25), confirming that lung function does not correlate with asthma severity in children (Citation26).

For twice-daily ICS/LABA users, a similar cohort of adults with asthma in the same database had higher OCS use, slightly fewer patients with ≥1 asthma-related ED visit or hospitalization, and comparable patients with ≥1 exacerbation compared with pediatric and adolescent patients with asthma in the current study (Citation14). The high proportion of OCS users in the treatment cohort in the present study highlights the large disease burden and unmet clinical need of asthma in children and adolescents. In addition, a plausible explanation as to why SABA prescription rates at follow-up were much lower in the asthma cohort compared with the treatment cohort is that patients may have multiple SABA canisters at home, which would artificially lower their refill rate.

There were several limitations. This study used fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims as indirect measures of adherence, which were not prospectively evaluated. The presence of a dispensed medication cannot guarantee that the medication was taken as prescribed. Conversely, adherence rates may be falsely high due to the common practice of automatic prescription re-fills. Medications unrecorded in claims data (e.g. over-the-counter, drug samples, and/or medications received during an inpatient stay) could not be accounted for in the present analysis. Moreover, pharmacy claims data reflect medication that was prescribed for a patient by a healthcare provider and dispensed at a pharmacy. Since the patients in this study were under the age of 18, their parent/caregiver would have likely paid for the dispensed medication and therefore the claims data received would depend on the specific pharmacy benefits and insurance they had at the time. Dosing frequency was assumed to be in accordance with the Prescribing Information for each product. Inherent to all claims-based analyses, this study may be subject to potential coding inaccuracies and missing data, including the absence of race/ethnicity details that are not collected in the IQVIA PHARMETRICS PLUS database. This database primarily contains claims data from families with commercial insurance plans and so does not include data for children who are uninsured or receiving Medicaid, and who may have different disease burden and adherence patterns to the children included in our study. Additionally, adherence was calculated using dispensing data; however, the presence of a claim for a filled prescription does not confirm that a patient used their medication, and medications obtained as samples or during impatient visits are not captured. Furthermore, it could be possible that ICS dose was increased for some patients due to unrecognized poor adherence, especially considering the low PDC in the study cohort. Despite these limitations, our study had a number of strengths, including that to mitigate misclassification bias, patients were required to have ≥2 claims of asthma to confirm their diagnosis. Other strengths included the real-world study design, and a large geographically diverse sample size with the ability to assess asthma patients 5–17 years of age with diverse medical histories across the US.

Potential areas of future research could include the association between adherence and exacerbations or rescue medication refills. Although we did not directly evaluate these associations, the data in suggest that higher use of rescue medication is associated with lower adherence to controller medications, and this would be an interesting avenue for future research. Other studies have shown (at least in adults) that higher adherence is associated with lower levels of OCS, SABA use, and severe exacerbations (Citation27,Citation28). This could potentially demonstrate that better adherence is associated with reduced risk of having an exacerbation or lower use of rescue medications.

Conclusions

A large disease burden and unmet need exist among children and adolescent asthma patients in the US as evidenced by low use of, and poor adherence to, ICS-containing medication, the notable proportion of OCS users, and higher-than-expected asthma-related ED and hospitalization rates. Understanding differences in adherence and the overall disease burden among the asthma population aged 5–17 years and those who were treated with twice-daily ICS or ICS/LABAs in real-world practice may help identify unmet care needs.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed to the conception/design of the study, the data analysis, and/or interpretation. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this analysis are based in part on data obtained under license from IQVIA. Source: IQVIA PHARMETRICS PLUS Claims Data 01/01/2012–09/30/17. All rights reserved. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IQVIA or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

208274_Supp_Fig_2_V2.pdf

Download PDF (123.3 KB)208274_Supp_Fig_1_V2.pdf

Download PDF (124.9 KB)208274_MS_Supplementary_Material.docx

Download MS Word (501.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Robson Lima for his contributions to the design of this study and advice during manuscript development. Editorial support in the development of the manuscript was provided by Jenni Lawton, PhD, at Ashfield MedComms (Macclesfield, UK), an Ashfield Health company, and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline plc.

Data sharing statement

To request access to de-identified patient-level data and documents for this study, please submit an enquiry via www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. Data included in this manuscript are derived from a database owned by IQVIA and contain proprietary elements, and therefore data cannot be broadly disclosed or made publicly available at this time. The disclosure of this data to third-party clients assumes certain data security and privacy protocols are in place and that the third-party client has executed IQVIA’s standard license agreement, which includes restrictive covenants governing the use of the data.

Declaration of interests

CMA, DJS, and JS are GlaxoSmithKline plc. employees and hold shares in GlaxoSmithKline plc. FL, GG, and MSD are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline plc. to conduct the current study.

Funding

This study (HO-18-18648) was funded by GlaxoSmithKline plc. The funders of the study had a role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. Employees of Analysis Group were not paid for manuscript development. Trademarks are owned by or licensed to their respective owners (IQVIA database [PHARMETRICS PLUS database, Health Plan Claims Data]).

References

- Ferrante G, La Grutta S. The burden of pediatric asthma. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:186. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00186.

- Serebrisky D, Wiznia A. Pediatric asthma: a global epidemic. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1):6. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2416.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent national asthma data. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm.

- Perry R, Braileanu G, Palmer T, Stevens P. The economic burden of pediatric asthma in the United States: literature review of current evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):155–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0726-2.

- Desai M, Oppenheimer JJ. Medication adherence in the asthmatic child and adolescent. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11(6):454–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-011-0227-2.

- Lang A, Mowinckel P, Sachs-Olsen C, Riiser A, Lunde J, Carlsen K-H, Lødrup Carlsen KC. Asthma severity in childhood, untangling clinical phenotypes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(6):945–953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01072.x.

- Oliver BG, Robinson P, Peters M, Black J. Viral infections and asthma: an inflammatory interface? Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1666–1681. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00047714.

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Third expert panel on the diagnosis and management of asthma. Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US); 2007. pp. 1–278, 326–328.

- Kaplan A, Hardjojo A, Yu S, Price D. Asthma across age: insights from primary care. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:162. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00162.

- Ortiz-Alvarez O, Mikrogianakis A, Canadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee. Managing the paediatric patient with an acute asthma exacerbation. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(5):251–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/17.5.251.

- Trivedi M, Denton E. Asthma in children and adults-what are the differences and what can they tell us about asthma? Front Pediatr. 2019;7:256. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00256.

- Kaplan A, Price D. Treatment adherence in adolescents with asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2020;13:39–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S233268.

- Stanford RH, Averell C, Parker ED, Blauer-Peterson C, Reinsch TK, Buikema AR. Assessment of adherence and asthma medication ratio (AMR) for a once-daily and twice-daily inhaled corticosteroid/long acting beta agonist (ICS/LABA) for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(5):1488–1496.e7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2018.12.021.

- Averell CM, Stanford RH, Laliberté F, Wu JW, Germain G, Duh MS. Medication adherence in patients with asthma using once-daily versus twice-daily ICS/LABAs. J Asthma. 2021;58(1):102–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2019.1663429.

- Wu AC, Butler MG, Li L, Fung V, Kharbanda EO, Larkin EK, Vollmer WM, Miroshnik I, Davis RL, Lieu TA, et al. Primary adherence to controller medications for asthma is poor. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(2):161–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-459OC.

- Marckmann M, Hermansen MN, Hansen KS, Chawes BL. Assessment of adherence to asthma controllers in children and adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(8):930–937. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13312.

- Burgess S, Sly P, Devadason S. Adherence with preventive medication in childhood asthma. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:973849. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/973849.

- Engelkes M, Janssens HM, de Jongste JC, Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(2):396–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00075614.

- Rehman N, Morais-Almeida M, Wu AC. Asthma across childhood: improving adherence to asthma management from early childhood to adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):1802–1807.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.02.011.

- Morton RW, Everard ML, Elphick HE. Adherence in childhood asthma: the elephant in the room. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(10):949–953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306243.

- Boutopoulou B, Koumpagioti D, Matziou V, Priftis KN, Douros K. Interventions on adherence to treatment in children with severe asthma: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:232. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00232.

- Chipps BE, Bacharier LB, Farrar JR, Jackson DJ, Murphy KR, Phipatanakul W, Szefler SJ, Teague WG, Zeiger RS. The pediatric asthma yardstick: practical recommendations for a sustained step-up in asthma therapy for children with inadequately controlled asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(6):559–579.e11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2018.04.002.

- Martinez FD, Chinchilli VM, Morgan WJ, Boehmer SJ, Lemanske RF, Mauger DT, Strunk RC, Szefler SJ, Zeiger RS, Bacharier LB, et al. Use of beclomethasone dipropionate as rescue treatment for children with mild persistent asthma (TREXA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):650–657. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62145-9.

- Lemanske RF, Jr, Mauger DT, Sorkness CA, Jackson DJ, Boehmer SJ, Martinez FD, Strunk RC, Szefler SJ, Zeiger RS, Bacharier LB, et al. Step-up therapy for children with uncontrolled asthma receiving inhaled corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):975–985. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1001278.

- Chipps BE, Zeiger RS, Borish L, Wenzel SE, Yegin A, Hayden ML, Miller DP, Bleecker ER, Simons FER, Szefler SJ, et al. Key findings and clinical implications from The Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):332–342.e10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.014.

- Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, White D, Lemanske RF, Jr, Sorkness CA. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):426–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200308-1178OC.

- Delea TE, Stanford RH, Hagiwara M, Stempel DA. Association between adherence with fixed dose combination fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on asthma outcomes and costs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(12):3435–3442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990802557344.

- Ismaila A, Corriveau D, Vaillancourt J, Parsons D, Stanford R, Su Z, Sampalis JS. Impact of adherence to treatment with fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in asthma patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(7):1417–1425. doi:https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2014.908827.