Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to investigate if menstruation and use of exogenous sex hormones influence self-reported asthma related quality of life (QoL) and asthma control.

Methods

The study is based on two asthma cohorts randomly selected in primary and secondary care. A total of 622 female patients 18–65 years were included and classified as premenopausal ≤ 46 years (n = 338) and peri/postmenopausal 47–65 years (n = 284). Questionnaire data from 2012 and 2014 with demographics, asthma related issues and sex hormone status. Outcome measures were Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (Mini-AQLQ) and asthma control including Asthma Control Test (ACT) and exacerbations last six months.

Results

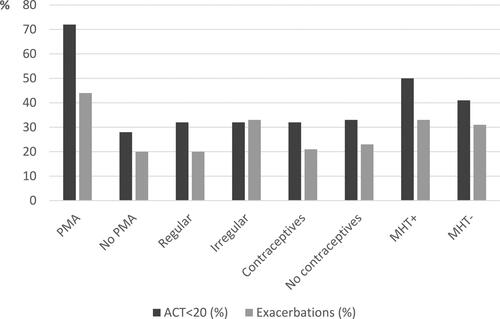

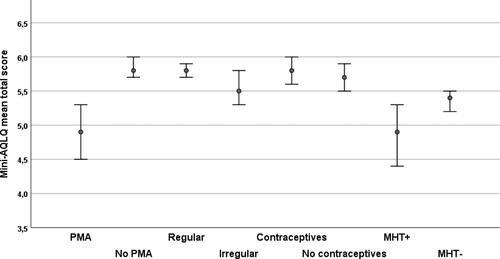

Premenopausal women with menstruation related asthma worsening, perimenstrual asthma (PMA) (9%), had a clinically relevant lower Mini-AQLQ mean score 4.9 vs. 5.8 (p < 0.001), lower asthma control with ACT score < 20, 72% vs. 28% (p < 0.001) and higher exacerbation frequency 44% vs. 20% (p = 0.004) compared with women without PMA. Women with irregular menstruation had higher exacerbation frequency than women with regular menstruation (p = 0.023). Hormonal contraceptives had no impact on QoL and asthma control. Peri/postmenopausal women with menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) had a clinically relevant lower Mini-AQLQ mean score compared to those without MHT, 4.9 vs 5.4 (p < 0.001), but no differences in asthma control.

Conclusion

Women with PMA had lower QoL and more uncontrolled asthma than women without PMA. Peri/postmenopausal women with MHT had lower QoL than women without MHT. Individual clinical management of women with asthma may benefit from information about their sex hormone status.

Introduction

Asthma severity in women may change over the life-course and appears to be related to transition periods in women’s reproductive lives (Citation1–4). Women might experience changes in the character of asthma symptoms during menstruation, pregnancy and the menopause (Citation2,Citation5,Citation6). Previous research has shown the influence of female sex hormones on asthma development and severity (Citation7,Citation8). Despite a number of studies, it is still unclear if specific female sex hormones or their imbalance are associated to the development, worsening or improvement of asthma in women (Citation9,Citation10).

It has been estimated that 19–40% of women experience worsening of asthma symptoms in relation to the menstruation, defined as perimenstrual asthma (PMA) (Citation11–13). Several studies have reported increased asthma symptoms, oral corticosteroid use and emergency department visits in this group (Citation1,Citation14). Furthermore, women with irregular menstruation seem to have more asthma symptoms and allergies than those with regular menstruation (Citation15).

Although sex hormone levels decrease with menopause, post-menopausal women have an increased risk of new-onset asthma (Citation7,Citation16). There are, however, contradictory results on how menopause influences current asthma (Citation17).

Also, previous studies about the influence of hormonal contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT or hormone replacement therapy, HRT) on current asthma have shown different results. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated both negative and positive impact of the use of hormonal contraceptives on asthma symptoms, while MHT in postmenopausal women had negative or no impact (Citation17).

In asthma care, the main goal of asthma management and treatment is achieving good asthma symptom control and minimizing the risk of exacerbations (Citation18). Another important clinical outcome is asthma related QoL that captures changes in health status which may not be seen in clinical measures such as lung function and the presence of symptoms (Citation19,Citation20). There is still limited knowledge how these parameters are affected by different hormonal transition periods in women’s lives.

The current study was based on questionnaire data including hormonal status, self-reported asthma related QoL and asthma control in women with asthma in a primary and secondary care population. The hypothesis was that endogenous sex hormones during the menstrual cycle in premenopausal women and exogenous sex hormones in pre- and peri/postmenopausal women increase the risk of worsening of QoL and asthma control.

Material and methods

Study population

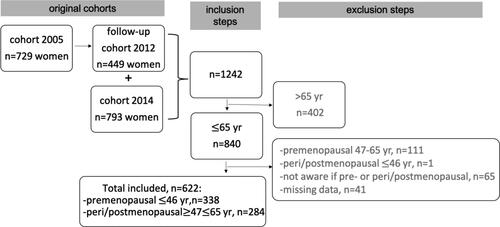

The study uses part of the Swedish PRAXIS cohort on asthma that started in 2005. A total of 1725 patients aged 18–75 years with a doctor´s diagnosis of asthma (ICD-10 J45) were randomly selected at 56 primary health care centers (PHCC) and 14 hospitals in central Sweden. The participants received a postal self-completion questionnaire about their asthma and related issues (Citation21). The cohort from 2005 was followed-up in 2012 whereof 449 women participated (response rate 62%). In 2014, a new cohort of 2803 patients with a doctor´s diagnosis of asthma (ICD-10 J45) aged 18–75 years were randomly selected at the same study centers. The same questionnaire as in 2012 was used and 793 women responded (response rate 46%). The present study sample includes a total of 622 female patients aged 18–65 from the follow-up in 2012 of the 2005 cohort and the 2014 cohort, see .

Questionnaire

The study questionnaire included information on age, daily smoking (yes/no), educational level (at or below, the higher level defined as at least three years above Swedish compulsory school of nine years) and body mass index (BMI) categorized as underweight (BMI < 20 kg/m2), normal (BMI 20.0–24.9 kg/m2) overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Other questions were on asthma onset age (early ≤15 years and late > 15 years), pet- and/or pollen-allergy and depression/anxiety during the previous 12 months. The level of strenuous physical activity was also included (high if daily, medium 4–6 times/week, low if three times or less/week).

Asthma treatment was classified according to GINA guidelines 2018 (Citation18); (Step 1) inhaled short-acting beta-2 agonist (SABA) if needed; (Step 2) daily or periodically inhaled corticosteroids (ICS); (Step 3) ICS and long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABA) and/or antileukotriene (LTRA) treatment.

To enable analysis of the influence of endo- and exogenous sex hormones on asthma outcomes five questions regarding menstruation, use of hormone contraceptives and MHT were included:

Have you experienced worsening of asthma the week before, during or after menstruation? Yes/No (Another option was, “I don’t have menstruation”).

Do you have regular menstruation? Yes/No

Have you used hormonal contraceptives such as oral contraceptives (pill and mini-pill), hormonal intrauterine device, birth control implant or contraceptive injection during the previous 6 months? Yes/No

Have you entered menopause (including have not menstruated for at least 6 months?) Yes/No

Do you use menopausal hormone treatment (oral or patch)? Yes/No

Pre- and peri/postmenopausal women- definition and comparison

The study group was divided into pre- and peri/postmenopausal women. Women were regarded as premenopausal if they answered no to the question whether they had entered menopause and peri/postmenopausal if the answer was yes. The upper age limit for the premenopausal group was 46 years based on a classification used in earlier studies, where 94% of women aged ≤ 46 years were premenopausal (Citation22,Citation23). Consequently, the lower age limit in the peri/postmenopausal group was 47 years, while the upper age limit of 65 years was set to include women more likely to have MHT.

A flow diagram of inclusion and exclusion steps is shown in , resulting in two groups of premenopausal women 18 to ≤ 46 years old (n = 338) and peri/postmenopausal women ≥ 47 to ≤ 65 years old (n = 284).

Asthma worsening in relation to menstruation is in this study defined as perimenstrual asthma (PMA) (Citation11,Citation12). The premenopausal women were compared with regard to PMA vs. no PMA, regular vs. irregular menstruation and use of hormonal contraceptives vs. no use of hormonal contraceptives. The peri/postmenopausal women were compared with regard to use of MHT vs. no use of MHT.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures included the Swedish versions of the Mini-Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (Mini-AQLQ), the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and the exacerbation frequency.

The Mini-AQLQ contains 15 questions divided into four domains that concern asthma symptoms, environmental factors, emotional functions and asthma related activity limitations during the last two weeks. The questions have responses on a seven-point scale, from severe (1) to no (7) impairment. A mean was calculated for each of the domains and the total score, where a clinically relevant difference was considered at a difference of 0.5 (Citation24). A mean score over six indicates that asthma does not have a significant impact on the quality of life (Citation25). The ACT includes five questions about the asthma symptom control in the past four weeks, yielding a maximum of 25 points. A total score of ≥ 20 points indicates sufficient asthma symptom control and < 20 points poor asthma symptom control (Citation26).

In this study, an asthma exacerbation was defined as an emergency visit and/or a course of oral steroids due to asthma worsening during the previous six months (Citation27).

Statistics

Data were analyzed with the SPSS (version 26.0) statistical package. Summary statistics such as means, proportions and measures of dispersion were computed with standard statistical methods. Differences in proportions were calculated with the chi-square test. Analysis of variance was used to calculate differences in the mean of the total score and domains of Mini-AQLQ. The multivariate analyses of the Mini-AQLQ used ANCOVA with adjustment for potential confounders which were chosen if p < 0.05 for the association with the Mini-AQLQ in the univariate analysis. These variables were BMI, pet and/or pollen allergy and educational level in analyses of premenopausal women with and without PMA and BMI and depression/anxiety in analyses with peri/postmenopausal women with and without MHT. Logistic regression was used to estimate the risk of exacerbations in premenopausal women with PMA with adjustment for pet and/or pollen allergy, daily smoking and educational level and in women with irregular menstruation with adjustment for pet and/or pollen allergy and educational level. To enable adjustment for clinically relevant confounders variables were chosen if the univariate associations had p values < 0.10. Logistic regression was also performed to estimate the risk of ACT < 20 in premenopausal women with PMA with adjustment for pet and/or pollen allergy and educational level (chosen with p values < 0.10 for associations in the univariate analysis). P values less than 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals that do not include 1.00 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (number 2011/318). Written informed consent was given by all patients.

Results

Premenopausal women

Descriptive characteristics

The mean age of the premenopausal women (n = 338) was 35 years (± SD 7.3), of them 58% had early asthma onset, 81% had pet and/or pollen allergy and 7% were daily smokers (). Among 307 premenopausal women who menstruated 9% experienced PMA and 21% stated they had an irregular cycle. Of all premenopausal women, 41% had used hormonal contraceptives during the last six months, with 51% using oral contraceptives, 11% birth control implants and 38% hormonal intrauterine devices. The characteristics of the subgroups of premenopausal women are presented in . Apart from daily smoking being more prevalent in women with irregular menstruation there were no notable differences in the characteristics between all subgroups.

Table 1. Characteristics of all premenopausal women ≤ 46 years, with and without perimenstrual asthma (PMA), with regular and irregular menstruation and with and without hormonal contraceptive treatment.

Mini-AQLQ

In women with PMA, the total mean score of the Mini-AQLQ was statistically significantly lower, with a clinically relevant difference, compared to women without PMA, 4.9 vs 5.8 (p < 0.001). There were statistically significantly and clinically relevant differences in all domains of the Mini-AQLQ, also with adjustment for pet and/or pollen allergy, BMI and educational level (). The total mean scores of the Mini-AQLQ were not statistically significantly different between women with regular and irregular menstruation 5.8 vs. 5.5 (p = 0.104) or between women using or not using hormonal contraceptives, 5.8 vs. 5.7 (p = 0.589).

Table 2. The Mini-AQLQ total and domain mean scores and 95% CI in premenopausal women ≤ 46 years with and without PMA.

Asthma control

Of women with PMA 72% had an ACT score < 20, whereas this proportion was 28% in those without PMA (p < 0.001); adjusted OR 6.7 (95% CI 2.63–17.16). Pet and/or pollen allergy and lower education were associated with a higher risk of an ACT score < 20. Exacerbations were also more frequent in women with PMA, 44% compared to 20% (p = 0.004), producing an adjusted OR of 3.0 (95% CI 1.29–6.97). In all four subgroups of women with regular and irregular menstruation and with and without hormonal contraceptives a third had an ACT score < 20. Twenty percent of women with regular menstruation reported exacerbations whereas 33% of those with irregular menstruation did so (p = 0.023); adjusted OR 2.1 (95% CI 1.14–4.00). Pet and/or pollen allergy and lower level of education were associated with higher risk of exacerbations in women with irregular menstruation comparing to those with regular menstruations. There were no differences in exacerbation frequency in women with and without hormonal contraceptives, 21% vs. 23% (p = 0.624).

Peri/postmenopausal women

Descriptive characteristics

The mean age of the peri/postmenopausal women was 58 years (± SD 4.6), of them 22% had asthma with early onset, 76% had pet and/or pollen allergy and 9% were daily smokers. There were no significant differences in characteristics between women with and without MHT ().

Table 3. Characteristics of peri/postmenopausal women and with and without hormone replacement therapy (MHT + and MHT-).

Mini-AQLQ

Women with MHT had significantly lower total mean Mini-AQLQ scores than women without MHT; 4.9 vs. 5.4 (p = 0.031), which was also a clinically relevant difference. In the activity limitations and emotional functions domains, statistically significant and clinically relevant differences were found depending on whether the women used MHT or not (). Even after adjustments for BMI and depression/anxiety there were significant and clinically relevant differences in the total mean score of Mini-AQLQ (p = 0.046) and emotional function domain (p = 0.035), ().

Table 4. The Mini-AQLQ total and domain mean scores and 95% CI in peri/postmenopausal women 47–65 years old with and without menopausal hormone therapy (MHT + and MHT-).

Asthma control

The differences between proportions of women with and without MHT that had ACT scores < 20 was not significant, 50% vs. 41% (p = 0.345) and the exacerbation frequency was also similar, 33% vs. 31% (p = 0.765).

Comparing all subgroups in premenopausal and peri/postmenopausal women

Mini-AQLQ, ACT and exacerbations

The Mini-AQLQ total mean scores were < 6 in all the studied subgroups (). Premenopausal women with PMA and peri/postmenopausal women with MHT had the lowest scores 4.9 (95%CI 4.48–5.30) and 4.9 (95% CI 4.42–5.31), respectively.

Figure 2. The Mini-AQLQ total mean score and 95% CI in premenopausal women with and without PMA, with regular and irregular menstruation, with and without hormonal contraceptives and peri/postmenopausal women with and without MHT.

shows the proportions of women with ACT scores < 20 and exacerbations in all subgroups. In three subgroups more than 40% women had an ACT score < 20: premenopausal women with PMA (72%), peri/postmenopausal women with MHT (50%) and without MHT (41%). Four subgroups had an exacerbation frequency over 30%: premenopausal women with PMA (44%), premenopausal women with irregular menstruation (33%), and peri/postmenopausal women with MHT (33%) and without MHT (31%).

Discussion

The main results of our study were that premenstrual women with PMA had lower QoL, poorer asthma symptom control and more frequent exacerbations and peri/postmenopausal MHT use was associated with lower QoL but not poorer asthma control.

The difference in QoL in women with PMA was clinically relevant, also after adjustment for pet and/or pollen allergy, BMI and educational level. Women with PMA had almost seven times higher risk of uncontrolled asthma and a threefold higher risk of exacerbations.

These findings are in line with earlier studies where aggravation of asthma in relation to the menstrual cycle has been associated with poorly controlled disease and higher frequency of urgent healthcare visits compared to women without PMA (Citation12,Citation14,Citation28). We have not found studies of asthma related QoL in this group in earlier research.

It has been suggested that PMA is a specific asthma phenotype in women characterized by frequent symptoms, exacerbations and associated with aspirin sensitivity, sinus symptoms, less atopy and lower lung capacity (Citation11,Citation13,Citation28). However, a meta-analysis showed no difference in total IgE levels in women with and without PMA (Citation13). Results from a previous study have confirmed that women have an increased airway resistance during the premenstrual period (Citation5), and this indicates that PMA is not only due to the perception of symptoms. In our study, women with PMA had no differences in BMI and prevalence of depression/anxiety in comparison with women without PMA. In some earlier studies though, a higher BMI and depression/anxiety have been independently associated to a lower QoL in asthma (Citation29,Citation30). The prevalence of women with PMA varies between studies due to different methods used (i.e. surveys or lung function measures) and selections of study population (Citation11,Citation12). The small number of women with PMA in our study may be a result of the method as we only used a self-completion questionnaire, with a risk for interpretation and/or recall difficulties.

Our second important result was that peri/postmenopausal women who used MHT had a statistically significantly and clinically relevant lower asthma related QoL than those without MHT, also with adjustment for potential confounders. Earlier studies including a recent meta-analysis demonstrated negative or no impact on asthma symptoms in postmenopausal women using MHT (Citation17,Citation31). Also, a longer use of MHT has been associated with a higher risk of exacerbation and hospital admission (Citation32). This may be a result of a selection bias as women with more symptoms during menopause might be more prone to have MHT. In our study there were no differences in characteristics between those with and without MHT. Other research similar to ours, has not distinguished between different types of MHT. It thus remains unclear whether MHT with estrogen, progesterone or combination of hormones have different effects on asthma. The relatively small number of women with MHT in our study may be due to an international trend in avoiding MHT following research showing that MHT may increase the risk of breast cancer (Citation34)

Another finding in this study was that women with irregular menstruation had a doubled risk of exacerbations compared to women with regular menstruation. In a European population study irregular menstruation was associated with increased asthma, allergy symptoms and lower lung function (Citation35).

We found no difference in asthma related QoL, asthma symptom control or exacerbation rate by use of hormonal contraceptives. In previous studies treatment with hormonal contraceptives had mixed results with both higher, equal and lower risk of asthma worsening episodes (Citation17). In another study, the risk of increased asthma symptoms related to oral contraceptives was greater in normal and overweight, but not lean women (Citation36). A recently published large 17-year follow-up cohort study in the UK demonstrated that combined hormonal contraceptives were associated with reduced risk of severe asthma exacerbation compared with no contraceptive use (37).

Strengths and weaknesses in the study

A strength of this study is the that it included randomly selected women with all severity stages of asthma. We assessed self-reported asthma related QoL life and asthma control in females of different ages measured by well-validated instruments in the same study.

The potential limitations include the small number of some subgroups, which was a consequence of strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. Additionally, collecting data via questionnaires may be biased by recall; e.g. inaccurate reporting of menstruation patterns may have led to some misclassification. Furthermore, we did not use objective measures such as lung function data or sex hormone level analyses.

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional study of randomly selected women with asthma we found that premenopausal women with PMA had lower QoL and poorer asthma control. Among peri/postmenopausal women MHT use was not associated with worse asthma control, but with lower QoL than women without MHT. This study highlights the possible need for guidelines related to management of women with asthma, including use of personalized questions on sex hormone status and the use of exogenous hormones.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yung JA, Fuseini H, Newcomb DC. Hormones, sex, and asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018; 120(5):488–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2018.01.016.

- McCallister JW, Mastronarde JG. Sex differences in asthma. J Asthma. 2008;45(10):853–861. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770900802444187.

- Zhang G-Q, Bossios A, Rådinger M, Nwaru BI. Sex steroid hormones and asthma in women: state-of-the-art and future research perspectives. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020;14(6):543–545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2020.1741351.

- Wright RJ. Hormones and women’s respiratory health across the lifespan: Windows of opportunity for advancing research. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(5):1643–1645. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.033.

- Oguzulgen IK, Turktas H, Erbas D. Airway inflammation in premenstrual asthma. J Asthma. 2002;39(6):517–522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1081/JAS-120004921.

- Jensen ME, Robijn AL, Gibson PG, Oldmeadow C, Murphy VE. Longitudinal analysis of lung function in pregnant women with and without asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(4):1578–1585. e3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.061.

- Postma DS. Gender differences in asthma development and progression. Gend Med. 2007;4(Suppl B):S133–S46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1550-8579(07)80054-4.

- Han YY, Forno E, Celedon JC. Sex steroid hormones and asthma in a nationwide study of U.S. adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(2):158–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201905-0996OC.

- Zein JG, Erzurum SC. Asthma is different in women. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15(6):28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-015-0528-y.

- De Martinis M, et al. Sex and gender aspects for patient stratification in allergy prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1–17

- Rao CK, Moore CG, Bleecker E, Busse WW, Calhoun W, Castro M, Chung KF, Erzurum SC, Israel E, Curran-Everett D, et al. Characteristics of perimenstrual asthma and its relation to asthma severity and control: data from the severe asthma research program. Chest. 2013;143(4):984–992. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0973.

- Graziottin A, Serafini A. Perimenstrual asthma: from pathophysiology to treatment strategies. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2016;11:30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40248-016-0065-0.

- Sanchez-Ramos JL, et al. Risk factors for premenstrual asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2017;11(1):57–72.

- Shames RS, Heilbron DC, Janson SL, Kishiyama JL, Au DS, Adelman DC. Clinical differences among women with and without self-reported perimenstrual asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81(1):65–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63111-0.

- Svanes C, Real FG, Gislason T, Jansson C, Jögi R, Norrman E, Nyström L, Torén K, Omenaas E. Association of asthma and hay fever with irregular menstruation. Thorax. 2005;60(6):445–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2004.032615.

- Triebner K, Johannessen A, Puggini L, Benediktsdóttir B, Bertelsen RJ, Bifulco E, Dharmage SC, Dratva J, Franklin KA, Gíslason T, et al. Menopause as a predictor of new-onset asthma: A longitudinal Northern European population study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(1):50–57 e6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.019.

- McCleary N, Nwaru BI, Nurmatov UB, Critchley H, Sheikh A. Endogenous and exogenous sex steroid hormones in asthma and allergy in females: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(4):1510–1513 e8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.034.

- GINA Guidelines. https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports. 2018.

- Wilson SR, Rand CS, Cabana MD, Foggs MB, Halterman JS, Olson L, Vollmer WM, Wright RJ, Taggart V. Asthma outcomes: quality of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3 Suppl):S88–S123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.988.

- Whalley D, Globe G, Crawford R, Doward L, Tafesse E, Brazier J, Price D. Is the EQ-5D fit for purpose in asthma? Acceptability and content validity from the patient perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0970-3.

- Kampe M, Lisspers K, Stallberg B, Sundh J, Montgomery S, Janson C. Determinants of uncontrolled asthma in a Swedish asthma population:crossectional observational study. Eur Clin Respir J. 2014;1:10–3402. /ecrj.v1.24109. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/ecrj.v1.24109.

- Speroff L GRH, Kase NG. Menopause and the perimenopausal transition. In: Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 6th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p. 1999643–1999724.

- Svensson M, Lindberg E, Naessen T, Janson C. Risk factors associated with snoring in women with special emphasis on body mass index: a population-based study. Chest. 2006;129(4):933–941. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.4.933.

- Juniper EF, Buist AS, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Validation of a standardized version of the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Chest. 1999;115(5):1265–1270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.115.5.1265.

- Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, Busse WW, Clark TJH, Pauwels RA, Pedersen SE. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):836–844. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC.

- Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, Kosinski M, Pendergraft TB, Jhingran P. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(3):549–556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011.

- Kisiel MA, Zhou X, Sundh J, Ställberg B, Lisspers K, Malinovschi A, Sandelowsky H, Montgomery S, Nager A, Janson C, et al. Data-driven questionnaire-based cluster analysis of asthma in Swedish adults. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30(1):14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-020-0168-0.

- Eid RC, Palumbo ML, Cahill KN. Perimenstrual asthma in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):573–578 e4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.054.

- Lavoie KL, Bacon SL, Labrecque M, Cartier A, Ditto B. Higher BMI is associated with worse asthma control and quality of life but not asthma severity. Respir Med. 2006;100(4):648–657. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.001.

- Lomper K, Chudiak A, Uchmanowicz I, Rosińczuk J, Jankowska-Polanska B. Effects of depression and anxiety on asthma-related quality of life. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2016;84(4):212–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.5603/PiAP.2016.0026.

- Nwaru BI, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of severe asthma exacerbation in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: 17-year national cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(7):2751–2760.

- Bonnelykke K, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and asthma-related hospital admission. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(3):813–816.

- Olsson HL, Ingvar C, Bladstrom A. Hormone replacement therapy containing progestins and given continuously increases breast carcinoma risk in Sweden. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1387–1392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11205.

- Real FG, Svanes C, Omenaas ER, Antò JM, Plana E, Janson C, Jarvis D, Zemp E, Wjst M, Leynaert B, et al. Menstrual irregularity and asthma and lung function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(3):557–564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.041.

- Macsali F, Real FG, Omenaas ER, Bjorge L, Janson C, Franklin K, Svanes C. Oral contraception, body mass index, and asthma: a cross-sectional Nordic-Baltic population survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(2):391–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.041.

- Nwaru BI, Tibble H, Shah SA, Pillinger R, McLean S, Ryan DP, Critchley H, Price DB, Hawrylowicz CM, Simpson CR, et al. Hormonal contraception and the risk of severe asthma exacerbation: 17-year population-based cohort study. Thorax. 2021;76(2):109–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215540.