Abstract

Objective

To describe clinical outcomes in patients with severe asthma (SA) by common sociodemographic determinants of health: sex, race, ethnicity, and age.

Methods

CHRONICLE is an observational study of subspecialist-treated, United States adults with SA receiving biologic therapy, maintenance systemic corticosteroids, or uncontrolled by high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids with additional controllers. For patients enrolled between February 2018 and February 2020, clinical characteristics and asthma outcomes were assessed by sex, race, ethnicity, age at enrollment, and age at diagnosis. Treating subspecialists reported exacerbations, exacerbation-related emergency department visits, and asthma hospitalizations from 12 months before enrollment through the latest data collection. Patients completed the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire and the Asthma Control Test at enrollment.

Results

Among 1884 enrolled patients, the majority were female (69%), reported White race (75%), non-Hispanic ethnicity (69%), and were diagnosed with asthma as adults (60%). Female, Black, Hispanic, and younger patients experienced higher annualized rates of exacerbations that were statistically significant compared with male, White, non-Hispanic, and older patients, respectively. Black, Hispanic, and younger patients also experienced higher rates of asthma hospitalizations. Female and Black patients exhibited poorer symptom control and poorer health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

In this contemporary, real-world cohort of subspecialist-treated adults with SA, female sex, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, and younger age were important determinants of health, potentially attributable to physiologic and social factors. Knowledge of these disparities in SA disease burden among subspecialist-treated patients may help optimize care for all patients.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at at www.tandfonline.com/ijas .

Introduction

Approximately 5%–10% of individuals with asthma have severe asthma (SA) that requires intensive therapy and subspecialist care (Citation1). SA is associated with considerable morbidity, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and long-term sequelae. Patients with SA often experience poor symptom control and frequent exacerbations (Citation2,Citation3). SA accounts for a disproportionate amount of annual costs and HCRU compared with mild asthma (Citation4–6). SA is a heterogenous disease with variable disease burden as well as multiple different phenotypes and endotypes (Citation2,Citation3).

Sex, race, ethnicity, and age are central sociodemographic factors that have been repeatedly associated with health inequities and disparities in care, driven by both physiologic and social mechanisms (Citation7,Citation8). For asthma in general, multiple demographic factors have been associated with differences in patient-experienced disease burden. Sex differences in asthma prevalence, morbidity, and HCRU are well-established, with asthma prevalence in adults confirmed as higher in women than men (Citation9–11). Older age has also been associated with increased asthma morbidity, mortality, and HCRU (Citation12,Citation13). There are well-established phenotypic differences by age-of-onset, such as childhood-onset asthma being more commonly associated with atopy and adult-onset asthma more commonly associated with non-allergic mechanisms (Citation14,Citation15). Race and ethnicity also affect asthma prevalence and severity. Black and Puerto Rican populations in the United States (US) have a disproportionately high prevalence of asthma and asthma-related mortality (Citation16,Citation17). Furthermore, studies have found that Black Americans are more likely than White Americans to have very poorly controlled asthma (Citation18).

Despite these previous observations, the effects of these factors on patient-experienced disease burden have not been extensively described in a contemporary, real-world population of US patients with subspecialist-confirmed SA. The CHRONICLE study is a prospective, real-world, non-interventional study of US adults with confirmed SA who are treated by a diverse sample of allergists/immunologists or pulmonologists. The aim of the current analysis was to examine the effects of sex, race, ethnicity, and age on clinical outcomes and disease burden among the large sample of contemporary, subspecialist-treated US patients with SA enrolled in CHRONICLE.

Methods

Described in detail previously (Citation19), CHRONICLE is an observational study of adult patients with SA residing in the US and treated by allergists/immunologists or pulmonologists. Eligible patients must be diagnosed with SA, as determined by subspecialists, for ≥12 months before enrollment. SA is defined according to European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines. Patients must be adults (aged ≥18 years) currently receiving care from subspecialist physicians at a participating site. Patients must also meet one or more of the following criteria: (1) current use of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved monoclonal antibody therapy for SA, (2) use of systemic corticosteroids (SCS) or other systemic immunosuppressants for SA for ≥50% of the prior 12 months, or (3) having persistently uncontrolled asthma (per ERS/ATS guidelines) while treated with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids with additional controllers. Study site selection was not probability weighted; however, efforts were taken to maximize the diversity and representativeness of study site selection by geography and practice type/setting (Citation19).

Per protocol, sites approached all eligible patients for enrollment in CHRONICLE. Patients provided written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to sign the written informed consent, not fluent in English or Spanish, unable to complete the study follow-up or web-based patient-reported outcomes, or received an investigational therapy for asthma, allergy, atopic disease, or eosinophilic disease as part of a clinical trial during the 6 months before enrollment. Enrollment in clinical trials of investigational therapies after enrollment in CHRONICLE was allowed. Central institutional review board (Advarra, Columbia, MD) approval was granted for the CHRONICLE study protocol on November 3, 2017, and the study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov on December 14, 2017 (NCT03373045).

Data collection

At enrollment, data on patient demographics, medical history, and current asthma management are collected from the treating subspecialist through an electronic case report form system. For each patient, the subspecialist also answers the following Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) control assessment questions: (1) Does the patient have daytime asthma symptoms more than twice per week? (2) Does the patient have any nocturnal/awakening symptoms due to asthma? (3) Does the patient require asthma-reliever medication use more than twice per week? (4) Does the patient have any activity limitation due to asthma?

Enrolled patients receive e-mails to complete surveys via a web-based interface at enrollment. The Asthma Control Test (ACT) is a five-item, five-option Likert-type questionnaire that assesses asthma symptoms and control in the past month, with possible scores ranging from 5 (poor asthma control) to 25 (complete asthma control) (Citation20). Scores on the ACT were divided into three categories for analysis: 5–15 (very poorly controlled), 16–19 (not well-controlled), 20–25 (well-controlled). The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) is a 50-item instrument for measuring health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with obstructive airway diseases, including SA and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), based on assessment of respiratory symptoms, activity limitations, and psychosocial effects in the prior 3 months. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater impairment (Citation21,Citation22).

The current study analyzed asthma outcomes among patients enrolled in CHRONICLE by sex, race, ethnicity, age at enrollment (18–49, 50–64, or ≥65 years), and age at diagnosis (<12, 12–17, 18–40, or >40 years). Race and ethnicity were collected by sites based on patient self-report, consistent with FDA guidance on best practices (Citation23). For ethnicity, patients reported “Hispanic or Latino” or “Not Hispanic or Latino.” For race, patients reported White, Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Not Reported, or Other. For the current analysis, the three populations analyzed were patients reporting Black race (regardless of reported ethnicity), Hispanic ethnicity (regardless of reported race), and those with non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity. Other racial/ethnic subgroups were too small to support robust comparisons.

For each subgroup, patient demographics, medical history, and current asthma treatment were evaluated as of patient enrollment. Additionally, the most recent results of pulmonary function testing (forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1] % predicted and forced vital capacity [FVC] % predicted) and the highest reported blood eosinophil count (BEC) while patients were not receiving biologics or SCS (because biologics and SCS can affect BEC values) were evaluated. The implementation of race adjustment for lung-function assessments was not collected at the site level but was expected to follow standard of care among US subspecialists based on standard guidelines for pulmonary assessments.

The primary disease burden outcome evaluated across patient subgroups was the annualized rate of subspecialist-confirmed asthma exacerbations. From 12 months before enrollment through the last data collection before the data cutoff date, annualized rates of exacerbations, emergency department (ED) visits (including urgent-care visits), and asthma hospitalizations, as well as characteristics of these events were analyzed. An exacerbation was defined as an event requiring inpatient hospitalization or treatment with ≥3 days of oral corticosteroids or ≥1 corticosteroid injection. Secondarily, subspecialist assessment of asthma control, ACT scores, and SGRQ scores at enrollment were also evaluated across subgroups. Subspecialist-reported GINA control question responses were summarized descriptively without statistical testing to provide further insight into patient symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed for patients enrolled between February 2018 and February 2020. Descriptive statistics were calculated for patient demographics and clinical characteristics at enrollment, overall and by sex, race, ethnicity, age at study enrollment, and age at asthma diagnosis. Annualized rates of exacerbations, ED visits, and asthma hospitalizations were assessed for each subgroup of interest on a person-time basis, in which the denominator reflects each patient’s contributed observation time while receiving a treatment. Stratified analyses were conducted by age at enrollment within each age at diagnosis category to determine whether effects were attributable to age at enrollment, age at diagnosis, or both because age at enrollment and diagnosis are correlated. Based on these results, statistical testing was only conducted for subgroups based on age at enrollment.

Rates of exacerbations, exacerbation-related ED visits, and asthma hospitalizations were compared among patient subgroups using generalized linear negative-binomial models, which allowed for the inclusion of observation time in the model. Comparisons of mean ACT and SGRQ scores among patient subgroups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. A multivariate analysis adjusting for other covariates was not conducted because the aim of this study was to describe the patient-experienced disease burden associated with sex, race, ethnicity, and age, not to evaluate the independent effects of these factors after adjusting for other differences. The disease burden experienced by a specific sex, race, or age subgroup was deemed the most relevant outcome of interest by the authors, regardless of how that burden is affected by other factors. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study-site characteristics

Patients were enrolled at 112 study sites. By geographic location, 28% of sites were in the Northeast, 13% in the Midwest, 43% in the South, and 16% in the West. Practice-setting location was 53% urban, 40% suburban, and 6% rural. Private practice (non-hospital) accounted for 80% of the site-practice settings, whereas university and non-university hospitals accounted for 15% and 4% of practice settings, respectively.

Overall patient characteristics

Among 1884 patients enrolled in CHRONICLE between February 2018 and February 2020, 69% of patients were female, and the mean age at enrollment was 54 years (). Demographics were similar between all eligible patients and enrolled patients (Table S1). Most patients (60%) were diagnosed with asthma as adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 29 years. The majority of patients were White (75%), 19% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic/Latino. Approximately half of the patients received care from a pulmonologist (51%), 39% from an allergist/immunologist, and 10% from both a pulmonologist and an allergist/immunologist. At enrollment, the majority of patients were receiving biologic therapy (65%), whereas 14% were receiving maintenance systemic corticosteroids (mSCS), and 30% were not receiving biologics or mSCS. Biologic and mSCS use were not mutually exclusive, and a small subset (8%) of patients received both biologic therapy and mSCS. Available ACT scores revealed that 43% of patients were very poorly controlled, 25% were not well-controlled, and 31% were well-controlled. By subspecialist answers to the GINA control questions, 45% of patients were considered uncontrolled, 25% partly controlled, and 19% well-controlled (11% had missing data).

Table 1. Patient characteristics overall and by sex, race, and ethnicity.

Sex differences

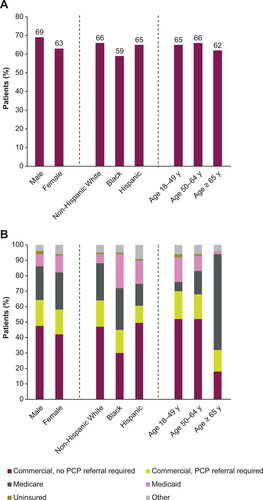

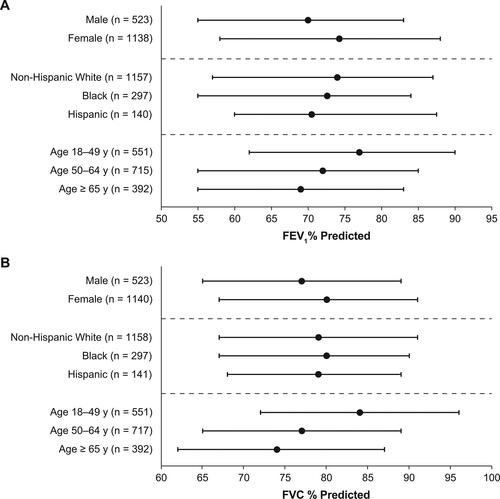

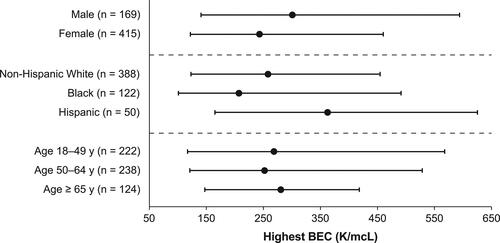

At enrollment, female patients had less full-time employment, a higher mean body mass index (BMI), and more comorbid depression, anxiety, and thyroid disease than male patients (). A higher percentage of female patients received care from a pulmonologist provider and a lower percentage of female patients received biologic treatment compared with male patients (). Female patients had higher median FEV1% () and FVC % () than male patients. Among those who had a BEC result while not receiving biologics or SCS, male patients had a higher median BEC than female patients ().

Figure 1. (A) Biologic recipient at enrollment and (B) insurance status by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. PCP, primary care provider.

Figure 2. Median FEV1 (A) and FVC (B) percent predicted by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. Error bars denote interquartile range. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Figure 3. Highest median BECa by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. aHighest BEC while not receiving biologics or SCS. Error bars denote interquartile range. BEC, blood eosinophil count; SCS, systemic corticosteroids.

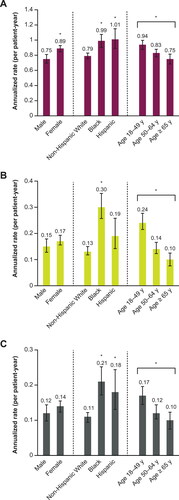

Female patients had a significantly higher annualized rate of exacerbations than male patients (P = 0.03; ). Although rates of exacerbation-related ED visits () and asthma hospitalizations () trended higher among female patients, no statistically significant differences were found.

Figure 4. Rates of HCP-confirmed asthma (A) exacerbations, (B) emergency department visits, and (C) hospitalizations by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. *P < 0.05; Error bars denote 95% CI. CI, confidence interval; HCP, health care provider.

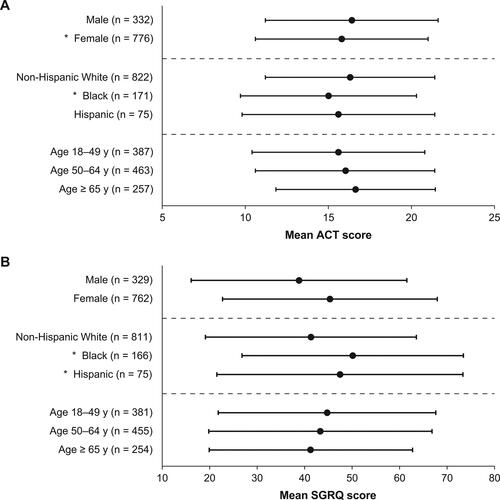

ACT scores by sex were not statistically significantly different (), but per subspecialist report female patients tended to have more daytime and nocturnal symptoms, more asthma reliever medication use, and more activity limitation due to asthma (). There was a statistically significant difference in SGRQ score by sex, with female patients reporting poorer HRQoL than male patients (P < 0.01; ).

Figure 5. Mean (A) ACT and (B) SGRQ scores by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. *P < 0.05; Error bars denote standard deviation. ACT scores range from 5 to 25 with higher scores reflecting better asthma control. SGRQ scores range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating poorer HRQoL. ACT, Asthma Control Test; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Race and ethnicity

Larger proportions of Hispanic and Black patients lived in an urban residential area compared with non-Hispanic White patients, and a greater proportion of Black patients lived within 500 feet of a major road (e.g. a highway) than other groups (). A smaller percentage of Black patients were employed full-time and had commercial insurance with no primary care provider referral required than other patient groups (). A lower proportion of Hispanic patients had hypertension, a lower proportion of non-Hispanic White patients had type 2 diabetes, and a lower proportion of Black patients had anxiety, seasonal allergies, and perennial allergies than other groups. A greater proportion of Black patients received care from a pulmonologist provider and were disabled because of asthma than other patient groups. Biologic use was less prevalent among Black patients than among non-Hispanic Whites (). Hispanic patients had lower median FEV1% predicted than non-Hispanic White patients () and a higher median BEC compared with other groups ().

The annualized exacerbation rate was significantly higher for Black (P < 0.02) and Hispanic (P < 0.03) patients than non-Hispanic White patients (). Additionally, the annualized rate of exacerbation-related ED visits was significantly higher among Black patients than non-Hispanic White patients (P < 0.01) and trended higher in Hispanic patients than non-Hispanic White patients (P = 0.21; ). The annualized rate of asthma-related hospitalizations was significantly higher for Black (P < 0.01) and Hispanic (P < 0.04) patients than non-Hispanic White patients ().

Scores on the ACT were significantly lower among Black patients than non-Hispanic White patients (P < 0.01), whereas ACT scores trended lower in Hispanic patients than non-Hispanic White patients (P = 0.25). Both Black patients (P < 0.01) and Hispanic patients (P = 0.02) reported significantly poorer HRQoL on the SGRQ than non-Hispanic White patients ().

Age at enrollment

With increasing age at enrollment, a greater proportion of patients were male and a smaller proportion were Black or Hispanic (). Former smoking, COPD, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia were more prevalent with older age, whereas allergic rhinitis and nasal polyps were less prevalent. With older age, a greater percentage of patients received care from a pulmonologist than an allergist/immunologist. Both predicted FEV1% () and FVC % () increased with younger age. Median BEC was similar across age groups ().

Table 2. Patient and clinical characteristics by age at enrollment and age at diagnosis.

There were significant differences in the annualized rates of exacerbations (P = 0.02), ED visits (P < 0.01), and asthma hospitalizations (P = 0.02) between age groups, with younger age correlating to a higher rate of exacerbations ().

There were no statistically significant differences on the ACT or SGRQ between age groups; although per subspecialist report, patients with younger age tended to experience more daytime and nocturnal symptoms and more asthma reliever medication use.

Age at diagnosis

Patients with older age at diagnosis more frequently lived in a rural residential area, reported former smoking, and less frequently reported perennial allergies (). Those diagnosed at age >40 years reported seasonal allergies less frequently, but more activity limitation because of asthma and more frequent care from a pulmonologist than other age groups.

Descriptively, there were no meaningful differences in patient characteristics, comorbidities, disease burden, or asthma-control level observed by age at diagnosis that were not observed by age at enrollment, and asthma exacerbation rates were similar by age at diagnosis. Stratified analyses revealed all measured outcomes to be more clearly related to increasing age at enrollment than age at diagnosis. Only prevalence of allergies and care by an allergist were associated with young age at diagnosis (<40 years) independent of age at enrollment.

Discussion

The current analysis is the largest characterization to date describing the effects of sex, race, ethnicity, and age on the disease burden experienced by real-world US subspecialist-treated patients with SA. Annualized exacerbation rates were significantly higher for female patients, Black patients, Hispanic patients, and patients with younger age at enrollment, and exacerbation-related HCRU was higher for Black patients, Hispanic patients, and younger patients. Notably, a smaller proportion of female patients and Black patients were receiving biologics compared with male and non-Hispanic White patients, respectively, which may have influenced disease control and exacerbation risk. The observation of these differences within the CHRONICLE population, all of whom were receiving ongoing subspecialist care, provides support for the role of physiologic and social factors in driving differences in disease burden by sex, race, ethnicity, and age. It is possible that these differences may be greater if studied in a larger population of US patients with SA who have differential access to subspecialist care.

The finding of increased patient disease burden among female patients with SA is consistent with previous smaller studies in which female patients with SA reported worse perception of asthma, more symptoms, and poorer HRQoL than male patients (Citation24). An analysis of the Severe Asthma Network in Italy showed that female patients had poorer disease control and a higher rate of asthma hospitalizations than male patients, whereas rates of exacerbations and ED visits were similar for both sexes (Citation10). A Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) analysis, which studied individuals with SA enrolled at select US academic centers, identified a sizable patient cluster of older women with obesity and late-onset asthma who experienced severe disease and frequent exacerbations (Citation25). Notably, despite greater disease burden, female patients had better lung function and lower BEC, consistent with previous findings (Citation10,Citation26). Although we are not aware that reduced biologic use in female patients with SA has been previously reported, sex differences in general asthma treatment have been observed, with female patients having greater oral corticosteroid use and short-acting beta-agonist use (Citation27).

Our findings of increased SA morbidity and HCRU for Black and Hispanic patients compared with non-Hispanic White patients validate previous work on racial disparities in asthma-related health outcomes. In a large cohort of adult patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma, Black patients were more likely to have asthma control problems and poorer HRQoL than White patients, even after adjusting for confounding variables (Citation28). African ancestry has been associated with increased exacerbation risk (Citation29,Citation30), and Black race has been associated with two- to five-fold higher rates of asthma-related ED visits (Citation17,Citation28,Citation31). A SARP analysis suggested that baseline differences in socioeconomic variables and environmental exposures may contribute to higher ED utilization among Black patients relative to White patients (Citation32). Others have suggested that racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of asthma care are a driving factor (Citation33). Minority populations are overrepresented in public health plans and may have reduced access to subspecialists and preventative care (Citation34). Additionally, an analysis of the Asthma Clinical Research Network trials showed that among adults with asthma, Black patients have a greater likelihood of treatment failure than White patients (Citation35). The current analysis adds to the body of evidence that poorer outcomes and HRQoL in Black Americans are multifactorial and influenced by physiologic and social determinants of health; Black patients had less full-time employment, more disability due to asthma and other reasons, higher BMI, more Medicaid insurance, and less use of biologics.

Few data are available regarding asthma morbidity and HCRU in the US Hispanic population. Available data demonstrate that there is considerable heterogeneity among Hispanic subgroups, particularly Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans, in asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality (Citation17,Citation36). Puerto Ricans have the highest asthma prevalence of any racial or ethnic group in the US, as well as the highest prevalence of asthma attacks (Citation16,Citation17,Citation36). However, most existing data on asthma mortality and HCRU outcomes in the US do not account for Hispanic subgroups (Citation17). This is also a limitation of the current analysis because the CHRONICLE study did not collect data on Hispanic ethnicity by subgroup. Further research is needed to better understand ethnic disparities in asthma outcomes.

A potential contributing factor to the increased disease burden experienced by Black and Hispanic individuals is exposure to air pollution. In our study, more Black and Hispanic patients reported urban residence than non-Hispanic White patients, and more Black patients reported living near a major road. A 2019 analysis similarly demonstrated greater exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) among Black and Hispanic populations (Citation17,Citation37). Multiple studies have shown that exposure to PM2.5 and other air pollutants can drive airway hyperresponsiveness and asthma exacerbations, ED visits, and hospitalizations (Citation38–40).

In our analysis, younger adult patients with SA had a higher risk of exacerbations, more frequently reported asthma symptoms, and had poorer HRQoL than older adult patients. Previous SARP analyses have similarly found that, among adults, SA and asthma hospitalizations were most common during middle age (Citation41,Citation42). The increased disease burden among younger patients with SA may be due in part to increased tissue inflammation, as evidenced in our study by an increased prevalence of nasal polyps and allergic disease in younger adults.

Limitations

The intent of this analysis was to describe real-world patient factors and their associated disease burden as experienced by patients, therefore no multivariate adjusted analyses were conducted. Analyses to evaluate the effect of comorbidities, lung function, smoking status, medication adherence, and other factors on disease burden by sex, race, ethnicity, and age were not conducted. Among patients included in the analysis, missing data and patient recall bias could affect the generalizability of findings. Not all patients completed online surveys at enrollment; patients who did not complete their surveys were not included in analyses of patient-reported outcomes. The study population was restricted to subspecialist-treated adults with SA, and therefore these results do not describe care for children with SA, patients not treated by a subspecialist, or patients outside of the US. There was a potential for enrollment bias; however, the bias appears to be minimal based on the similarities between all eligible and all enrolled patients. In addition, site selection was not probability weighted, so the generalizability of study results is unknown. However, it is reassuring that the site characteristics were generally similar to those observed in other samples of US asthma subspecialists (Citation19) and that the associations observed have been described previously in other patient samples.

Conclusions

There are meaningful differences in the disease burden experienced by US adults with SA across the core sociodemographic variables of sex, race, ethnicity, and age. The observed disparities are consistent with previous observations regarding the clinical phenotypes of SA and racial and ethnic disparities in asthma outcomes. The causes of the observed disparities are likely multifactorial and potentially attributable to physiologic and social factors. Biologic use was found to be lower among female and Black patients, which may have contributed to the greater disease burden and higher exacerbation risk observed in these groups. Documenting disparities in patient outcomes and HCRU can help optimize asthma care for patients.

SA_Disease_Burden_in_the_US_Supplemental_8Nov2021.docx

Download MS Word (31.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Camille Sample, PhD, and Casey Demko, MS, of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc. (Newtown, PA, USA), which was in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by AstraZeneca (Wilmington, DE, USA). Portions of this manuscript have been previously presented as a poster presentation with interim findings at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) 2021 Annual Meeting, and the abstract was published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.200).

Declaration of interests

Njira Lugogo received consulting fees for advisory board participation from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Teva; honoraria for non-speakers bureau presentations from GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca; and travel support from AstraZeneca; her institution received research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Avillion, Gossamer Bio, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Teva. Elizabeth Judson, Frank Trudo, and Christopher S. Ambrose are employees and shareholders of AstraZeneca. Erin Haight was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this work was conducted. Bradley E. Chipps is an advisor for, received consultancy fees from, and is on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. Jennifer Trevor is a consultant for AstraZeneca and on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Data availability statement

CHRONICLE is an ongoing study; individual de-identified participant data cannot be shared until the study concludes. The full study protocol is available upon request of the corresponding author. Individuals who were or were not involved in the study may submit publication proposals to the study’s Publication Steering Committee by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343–373. doi:10.1183/09031936.00202013.

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2020. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GINA-2020-full-report_-final-_wms.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2020.

- Trevor JL, Chipps BE. Severe asthma in primary care: identification and management. Am J Med. 2018;131(5):484–491. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.12.034.

- Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, Lynd L, Alasaly K, Swiston J, FitzGerald JM. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:24. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-9-24.

- Cisternas MG, Blanc PD, Yen IH, Katz PP, Earnest G, Eisner MD, Shiboski S, Yelin EH. A comprehensive study of the direct and indirect costs of adult asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(6):1212–1218. doi:10.1067/mai.2003.1449.

- Kerkhof M, Tran TN, Soriano JB, Golam S, Gibson D, Hillyer EV, Price DB. Healthcare resource use and costs of severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma in the UK general population. Thorax. 2018;73(2):116–124. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210531.

- Sullivan K, Thakur N. Structural and social determinants of health in asthma in developed economies: a scoping review of literature published between 2014 and 2019. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20(2):5. doi:10.1007/s11882-020-0899-6.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing Interactions Among Social Behavioral and Genetic Factors in Health. Genes, Behavior, and the Social Environment: Moving Beyond the Nature/Nurture Debate(LM Hernandez, DG Blazer, editors). Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006.

- Schatz M, Camargo CAJr. The relationship of sex to asthma prevalence, health care utilization, and medications in a large managed care organization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(6):553–558. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61533-5.

- Senna G, Latorre M, Bugiani M, Caminati M, Heffler E, Morrone D, Paoletti G, Parronchi P, Puggioni F, Blasi F, et al. Sex differences in severe asthma: results from Severe Asthma Network in Italy-SANI. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2021;13(2):219–228. doi:10.4168/aair.2021.13.2.219.

- Shah R, Newcomb DC. Sex bias in asthma prevalence and pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2997. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02997.

- Tsai C-L, Delclos GL, Huang JS, Hanania NA, Camargo CA. Age-related differences in asthma outcomes in the United States, 1988-2006. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110(4):240–246.e1. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.01.002.

- Tsai C-L, Lee W-Y, Hanania NA, Camargo CA. Age-related differences in clinical outcomes for acute asthma in the United States, 2006-2008. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(5):1252–1258.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.061.

- Pakkasela J, Ilmarinen P, Honkamäki J, Tuomisto LE, Andersén H, Piirilä P, Hisinger-Mölkänen H, Sovijärvi A, Backman H, Lundbäck B, et al. Age-specific incidence of allergic and non-allergic asthma. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12890-019-1040-2.

- Tan DJ, Walters EH, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, Dharmage SC. Age-of-asthma onset as a determinant of different asthma phenotypes in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2015;9(1):109–123. doi:10.1586/17476348.2015.1000311.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. 2018 National Health Interview Survey data. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/nhis/2018/data.htm. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. 2020. Asthma disparities in America: a roadmap to reducing burden on racial and ethnic minorities. aafa.org/asthmadisparities. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Haselkorn T, Szefler SJ, Chipps BE, Bleecker ER, Harkins MS, Paknis B, Kianifard F, Ortiz B, Zeiger RS. Disease burden and long-term risk of persistent very poorly controlled asthma: TENOR II. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2243–2253. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2020.02.040.

- Ambrose CS, Chipps BE, Moore WC, Soong W, Trevor J, Ledford DK, Carr WW, Lugogo N, Trudo F, Tran TN, et al. The CHRONICLE study of US adults with subspecialist-treated severe asthma: objectives, design, and initial results. Pragmat Obs Res. 2020;11:77–90. doi:10.2147/POR.S251120.

- Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Pendergraft TB. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):59–65. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008.

- Jones PW, Forde Y. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Manual. London, UK: Division of Cardiac and Vascular Science, St George’s, University of London; 2009.

- Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85 Suppl B:25–31; discussion 33–37. doi:10.1016/S0954-6111(06)80166-6.

- Food and Drug Administration. Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/collection-race-and-ethnicity-data-clinical-trials. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Colombo D, Zagni E, Ferri F, Canonica GW. Gender differences in asthma perception and its impact on quality of life: a post hoc analysis of the PROXIMA (Patient Reported Outcomes and Xolair® In the Management of Asthma) study. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2019;15:65. doi:10.1186/s13223-019-0380-z.

- Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(4):315–323. doi:10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC.

- Milger K, Korn S, Buhl R, Hamelmann E, Herth FJF, Gappa M, Drick N, Fuge J, Suhling H. Age- and sex-dependent differences in patients with severe asthma included in the German Asthma Net cohort. Respir Med. 2020;162:105858. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105858.

- Kynyk JA, Mastronarde JG, McCallister JW. Asthma, the sex difference. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(1):6–11. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283410038.

- Haselkorn T, Lee JH, Mink DR, Weiss ST. Racial disparities in asthma-related health outcomes in severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(3):256–263. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60490-5.

- Grossman NL, Ortega VE, King TS, Bleecker ER, Ampleford EA, Bacharier LB, Cabana MD, Cardet JC, Carr TF, Castro M, et al. Exacerbation-prone asthma in the context of race and ancestry in Asthma Clinical Research Network trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(6):1524–1533. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.08.033.

- Rumpel JA, Ahmedani BK, Peterson EL, Wells KE, Yang M, Levin AM, Yang JJ, Kumar R, Burchard EG, Williams LK, et al. Genetic ancestry and its association with asthma exacerbations among African American subjects with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1302–1306. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.001.

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 emergency department summary tables. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Fitzpatrick AM, Gillespie SE, Mauger DT, Phillips BR, Bleecker ER, Israel E, Meyers DA, Moore WC, Sorkness RL, Wenzel SE, et al. Racial disparities in asthma-related health care use in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2052–2061. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.11.022.

- Cabana MD, Lara M, Shannon J. Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of asthma care. Chest. 2007;132(5 Suppl):810S–817S. doi:10.1378/chest.07-1910.

- Canino G, McQuaid EL, Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6):1209–1217; quiz 1218–1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.043.

- Wechsler ME, Castro M, Lehman E, Chinchilli VM, Sutherland ER, Denlinger L, Lazarus SC, Peters SP, Israel E. Impact of race on asthma treatment failures in the asthma clinical research network. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(11):1247–1253. doi:10.1164/rccm.201103-0514OC.

- Rosser FJ, Forno E, Cooper PJ, Celedón JC. Asthma in Hispanics. An 8-year update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(11):1316–1327. doi:10.1164/rccm.201401-0186PP.

- Tessum CW, Apte JS, Goodkind AL, Muller NZ, Mullins KA, Paolella DA, Polasky S, Springer NP, Thakrar SK, Marshall JD, et al. Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial-ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(13):6001–6006. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818859116.

- Lu X, Li R, Yan X. Airway hyperresponsiveness development and the toxicity of PM2.5. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(6):6374–6391. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-12051-w.

- Orellano P, Quaranta N, Reynoso J, Balbi B, Vasquez J. Effect of outdoor air pollution on asthma exacerbations in children and adults: Systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174050. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174050.

- Zheng X-Y, Ding H, Jiang L-N, Chen S-W, Zheng J-P, Qiu M, Zhou Y-X, Chen Q, Guan W-J. Association between air pollutants and asthma emergency room visits and hospital admissions in time series studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138146. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138146.

- Teague WG, Phillips BR, Fahy JV, Wenzel SE, Fitzpatrick AM, Moore WC, Hastie AT, Bleecker ER, Meyers DA, Peters SP, et al. Baseline features of the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP III) cohort: differences with age. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):545–554.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.032.

- Zein JG, Udeh BL, Teague WG, Koroukian SM, Schlitz NK, Bleecker ER, Busse WB, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Comhair SA, et al. Impact of age and sex on outcomes and hospital cost of acute asthma in the United States, 2011–2012. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157301. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157301.