Abstract

Objective

To compare parent reported physician diagnosed asthma from questionnaires for epidemiological purposes, to general practitioner (GP) recorded childhood asthma.

Methods

This study was embedded in the KOALA Birth Cohort Study with regular follow-up by ISAAC core questions on asthma in 2834 children in two different recruitment groups, with ‘conventional’ lifestyles or ‘alternative’ lifestyles. At age 11–13 years these data were linked to data extracted from GP records. We compared parent reported physician diagnosed asthma, asthma medication use, and current asthma with GP recorded asthma diagnosis and medication. Two different combinations of questions were used to define current asthma (i.e. ISAAC and MeDALL based definition).

Results

Among 958 children with information provided both by the parents and GPs, 98 children (10.2%) had parent reported physician diagnosed asthma, 115 children (12.0%) had a GP recorded asthma diagnosis (Cohen’s kappa 0.49; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.57). Discrepant cases showed that asthma symptoms at an early age led to different labeling between parents and GP. The agreement between ISAAC based definition and MeDALL based definition was excellent (Cohen’s kappa 0.82; 95% CI 0.74 to 0.88).

Conclusion

Parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP recorded childhood asthma had only moderate agreement, and is possibly influenced by labeling early transient wheeze as asthma diagnosis. It is important that parent reported physician diagnosed asthma is combined with additional questions such as current asthma symptoms and asthma medication use, as used in ISAAC or MeDALL based current asthma, in order to obtain reliable information for epidemiological research.

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease with symptoms of wheeze and shortness of breath that are highly variable in time (Citation1). Asthma is a clinical diagnosis, based on a combination of recurrent clinical symptoms and signs in patient history and physical examination, combined with a reversible airflow obstruction in spirometry (Citation2). Ideally, spirometry is performed at the time that clinical symptoms of an asthma exacerbation are present. For epidemiological research, it is important to use a uniform and reliable asthma definition that is feasible to perform in large study populations. In most epidemiological studies, asthma is defined through questionnaires instead of spirometry or clinical assessment due to advantages in data collection, costs and time efficiency (Citation3). The most comprehensive international study on asthma prevalence in children is the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) (Citation4). This collaborative research project developed and validated questionnaires for measuring prevalence of asthma in childhood. Common core ISAAC questions on asthma are: “Did a physician ever diagnose asthma in your child?” and “Has your child ever had asthma”. Although ISAAC has contributed greatly to uniform and valid asthma measurement, a standardized operational asthma definition for epidemiological studies is lacking (Citation5). The MeDALL collaboration (Mechanisms of the Development of Allergy) aimed to further harmonize information on asthma in epidemiological studies and made proposals for definitions of current asthma, eczema and rhinitis (Citation6,Citation7).

The main goal of this study is to compare questionnaire based parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and parent reported use of asthma medication with GP reported asthma diagnosis and asthma medication in children. We will also describe the discrepancies between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP records.

We compared parent reported physician diagnosed asthma, GP recorded asthma diagnosis, asthma medication use, and commonly used combinations of questions to define current asthma in order to determine which gives the most accurate information on the presence of asthma. Our hypothesis is that parent reported physician diagnosed asthma corresponds well to GP reported asthma diagnosis. This is important for the use of parent based questionnaires in epidemiological research, but also useful for clinical practice, as the parents are the spokesperson for their child and it is important that clinicians know whether a parent reported physician diagnosed asthma is indicative of a GP reported asthma diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study is an agreement study comparing parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and asthma medication use with GP recorded asthma diagnosis and asthma medication.

Study population

This study was embedded in the KOALA Birth Cohort Study of 2834 children born between 2001 and 2003 (KOALA is an acronym [in Dutch] for Child, Parent, and Health: Lifestyle and Genetic Constitution). The study consists of two recruitment groups, families with “alternative” and “conventional” lifestyles (Citation8). Families with alternative lifestyles with regard to child rearing practices, dietary habits, vaccination schemes and/or use of antibiotics, were recruited through organic food shops, anthroposophical doctors and midwives. Healthy pregnant women with conventional lifestyles were recruited from an ongoing study on pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (Citation9). Parents were asked to fill out written questionnaires on asthma symptoms and asthma diagnosis at several ages (i.e. 3 and 7 months, 1 year, 2 years, 4 to 5 years, 6 to 7 years, 6 to 8 years, 7 to 9 years, 8 to 10 years, and 8 to 11 years). ISAAC core questions on physician diagnosed asthma and asthma medication use were used: “Did a physician ever diagnose asthma in your child?” and “Did your child use medication for asthma or wheezing in the last 12 months?”, “Which medication and how often did your child use medication in the last 12 months for asthma or wheezing?”.

Asthma care pathway

In the Netherlands the general practitioner (GP) is the central person in the patient’s healthcare, and acts as a gatekeeper for the patient’s health and that of their family. In general, asthma is diagnosed by the general practitioner or pediatrician by clinical observation of recurrent episodes of dyspnea and wheeze, preferably supported by a spirometry with reversible bronchoconstriction. In general, mild asthma with only on demand bronchodilators or stable with normal dosage of inhaled corticosteroids, is treated by the general practitioner. Moderate or severe asthma is treated by the pediatrician. The pediatrician will inform the general practitioner of the diagnosis and treatment with regular correspondence, as the general practitioner is the gatekeeper of the patient’s health in general (Citation10).

Operational asthma definitions

In the KOALA cohort we defined current asthma using the following combination of ISAAC questions: physician diagnosed asthma combined with symptoms of dyspnea or wheeze in the last 12 months and/or regular use of asthma medication in the last 12 months (i.e. daily use of corticosteroids or bronchodilators or use of bronchodilators during exercise) (Citation11). For this study, we also used the MeDALL based definition of current asthma, which is defined as presence of at least two out of the next three criteria: (1) physician diagnosed asthma, (2) wheeze in the last 12 months, and (3) use of asthma medication in the last 12 months (Citation7).

Data collection

In 2008 (when the children were around age 6–7 years), the parents were asked informed consent to approach their GP for their child’s medical information. In 2014 (when the children were around age 11–13), GPs of participating children were asked to fill out a written questionnaire on several diagnoses (i.e. asthma, eczema, hay fever, attention deficit hyperactive disease (ADHD), chronic intestinal disorders) and medication use. Children with available information from their GP and follow-up at least until the age of 8 to 10 years were included in this study.

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of participating children. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Ethical Review Committee of Maastricht University Medical Centre+ (approval number MEC 08-4-016.4, 2008).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). We used Cohen’s kappa statistic with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to quantify agreement. A kappa over 0.81 was considered as excellent, a kappa of 0.61 to 0.80 was considered good, 0.41 to 0.60 moderate, 0.21 to 0.40 fair, and lower than 0.20 poor (Citation12).

Because the last follow-up by parental questionnaire was around one year before the extraction of GP data, we restricted GP reported asthma medication to the period up to the questionnaire date.

The main analysis was aimed to quantify agreement between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP recorded asthma diagnosis. Secondly, we compared parent reported asthma medication use with asthma medication reported by the GP. Thirdly, we compared two different sets of combined questions to define current asthma (i.e. ISAAC and MeDALL based definition of current asthma) with physician diagnosed asthma reported by the parents or GP. In addition, we provided insight into causes of discrepancies between parent reported information and GP records. We performed additional analyses with stratification for recruitment group because we hypothesized that parents in the alternative lifestyle recruitment group could possibly be more restrictive in seeking medical care for asthmatic symptoms and asthma medication use.

Results

In total, parents of 1795 children consented to approaching the GP for medical information. Those with incomplete information or no possibility to link to the GP data were excluded from analysis (missing or unreadable GP address (n = 15), incomplete form (n = 35), discontinued or unknown GP practice (n = 82)).

Valid GP addresses were available for 1663 children from 744 different GP practices (420 practices with one child; the others with two up to nineteen children per practice). These GPs were sent a short questionnaire, to which 529 (71% of 744 GP practices) responded by returning the questionnaire for one or more children, totaling 1172 children. Of the returned questionnaires 1061 questionnaires were valid. The remainder indicated that the child was no longer a patient (n = 95), or refused to fill out the questionnaire (n = 16), for example because of lack of time. We excluded twins (n = 16) to prevent accidental mix-ups by their parents or GP.

Finally, 966 of the remaining 1045 children had information on either parent reported asthma diagnosis or asthma medication at age 8–10 or 8–11 years, and were included in this study. shows the characteristics of the base population, the children whose parents gave informed consent for linkage with the GP record, and the children with available GP record.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants of the KOALA Birth Cohort Study, Netherlands.

Physician diagnosed asthma

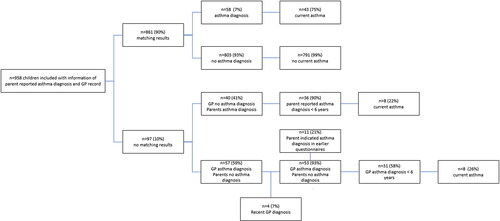

Physician diagnosed asthma was reported by the parents in 98 children (10.2% of 958 children with information on parent reported physician diagnosed asthma), compared to 115 children (12.0%) according to the GP record (). The agreement between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP recorded asthma diagnosis was moderate, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.49 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.57).

Table 2. Parent reported physician diagnosed asthma compared to GP record.

We zoomed in on the cases in which there was no agreement between parental and GP provided information. In 40 cases, the parents indicated that the child had been diagnosed with asthma by a physician while the GP did not. From these 40 discrepant cases it was striking that 36 children (90%) were reported by the parents as having an asthma diagnosis set by a physician before the age of 6 (often 0 to 2 years). Of these children with a reported asthma diagnosis at an early age, only 6 children (15%) were still using asthma medication according to the parents, and 5 according to the GP record (13%). When the more strict definition of current asthma was applied to these 36 cases, only 8 (22%) met the ISAAC based definition, compared to 6 (17%) when using the MeDALL based definition of current asthma.

On the other side, in 57 cases the GP record showed an asthma diagnosis, while the parents did not report this in the last two follow-up questionnaires (ages 8 to 10 years and 8 to 11 years). From these 57 discrepant cases, 4 were diagnosed only recently (after the last follow-up questionnaire) and thus could not have been indicated as diagnosed asthma by the parents yet. From the remaining 53 discrepant cases, 31 children (59%) were diagnosed at an early age according to the GP record (before 6 years), from which 23 (74% of 31 children) had no symptoms or medication use anymore at age 8 to 11 years according to the parents. In 11 cases (21%), parents seemed to have forgotten an earlier asthma diagnosis: in earlier questionnaires (at ages 6 to 7 years, 6 to 8 years, or 7 to 9 years) the parents did fill out an asthma diagnosis, while they did not in the last two follow-up questionnaires at ages 8 to 10 years and 8 to 11 years. In total, only 8 of the 31 discrepant cases with an early diagnosis met the ISAAC based definition of current asthma (26%), while 4 met the MeDALL based definition (13%). See for a visual representation of agreement and discrepancies of parent reported physician diagnosed asthma compared to GP recorded asthma.

Figure 1. Visual representation of agreement and discrepancies of parent reported physician diagnosed asthma compared to GP recorded asthma diagnosis. Parent reported physician diagnosed asthma ever reported in follow-up questionnaires at ages 8 to 10 years or 8 to 11 years. Current asthma either by ISAAC or MeDALL based definition. ISAAC based current asthma is defined as ((1) physician diagnosed asthma and (2) asthma symptoms (dyspnea or wheeze) in the last 12 months) and/or (3) regular use of asthma medication in the last 12 months. MeDALL based current asthma was defined as presence of two out of the next three criteria: (1) physician diagnosed asthma, (2) wheeze in the last 12 months, and (3) use of asthma medication in the last 12 months.

Physician diagnosed asthma compared to current asthma

The agreement between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and current asthma was moderate for both definitions: Cohen’s kappa 0.59 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.68) for ISAAC based current asthma, Cohen’s kappa 0.57 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.67) for MeDALL based current asthma. The agreement between GP recorded asthma diagnosis and current asthma was somewhat lower: Cohen’s kappa 0.53 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.63) for ISAAC based current asthma, and Cohen’s kappa 0.48 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.56) for MeDALL based current asthma. (More details in supplemental file).

Asthma medication

The recent use of asthma medication was reported in 78 (8.1% of 965) children by the parents, compared to 63 (6.5%) children in the GP records (). The agreement between parent reported asthma medication use in the last 12 months and GP recorded asthma medication around the same time period was moderate, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.56 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.66).

Table 3. Parent reported asthma medication compared to GP record.

We focused on the discrepancies: in 21 cases asthma medication was prescribed by the GP recently, while the parents did not report this. In 6 of these cases (29%) parents reported physician diagnosed asthma, compared to 7 asthma diagnoses (33%) in the GP records. Only a few cases met the definitions for current asthma (n = 2 for ISAAC based definition, and n = 1 for MeDALL based definition). In 36 cases parents did report recent asthma medication use, while there was no record of this in the GP record. In 21 cases (58%) parents reported a physician diagnosed asthma, and in 22 cases there was an asthma diagnosis in the GP record (61%). A notable number of 32 cases (89%) met the ISAAC based definition of current asthma, and 28 (78%) met the MeDALL based definition.

Current asthma

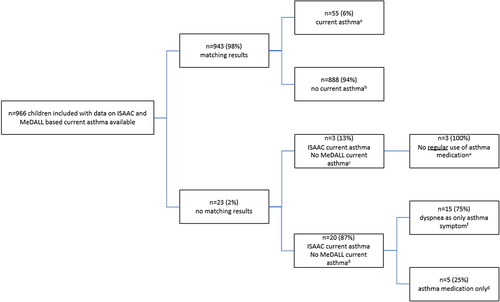

In total, 75 children (7.8%) met the ISAAC based definition of current asthma, as reported by the parents, compared to 58 children (6.0%) defined by the MeDALL based definition of current asthma (). The agreement between the ISAAC based definition and MeDALL based definition was (as expected) excellent, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.82 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.88).

Table 4. ISAAC and MeDALL based definition of current asthma.

In 3 cases, the child met the MeDALL definition of current asthma, but not the ISAAC based definition. In 20 cases, the child met the ISAAC based definition but did not meet the MeDALL based definition. See for a visual representation and explanation of the differences between the ISAAC and MeDALL based definitions.

Figure 2. Visual representation of agreement and discrepancies of ISAAC based current asthma and MeDALL based current asthma. ISAAC based current asthma and MeDALL based current asthma, both reported in follow-up questionnaires at age 8 to 10 years or 8 to 11 years. ISAAC based current asthma was defined as ((1) physician diagnosed asthma and (2) asthma symptoms (dyspnea or wheeze) in the last 12 months) and/or (3) regular use of asthma medication in the last 12 months. MeDALL based current asthma was defined as presence of two out of the next three criteria: (1) physician diagnosed asthma, (2) wheeze in the last 12 months, and (3) use of asthma medication in the last 12 months.

a Current asthma according to both ISAAC and MeDALL based definition.

b No current asthma according to both ISAAC and MeDALL based definition.

c Current asthma according to MeDALL based definition, but not according to ISAAC based definition.

d Current asthma according to ISAAC based definition, but not according to MeDALL based definition.

e Any use of asthma medication but not meeting the requirements for regular asthma medication use according to ISAAC based definition (i.e. daily use of corticosteroids or bronchodilators or use of bronchodilators during exercise).

f Dyspnea as only asthma symptom which meets the asthma symptoms according to ISAAC based definition (i.e. dyspnea or wheeze) but not MeDALL based definition (i.e. wheeze).

g Regular use of asthma medication but no physician diagnosed asthma or recent asthma symptoms. ISAAC based definition required the logical rule of (physician diagnosed asthma AND asthma symptoms) OR (asthma medication use), while MeDALL required 2 out of 3 criteria.

Lifestyle

Of the total study population, 783 children (81%) were from families in the conventional recruitment group, while 183 children (9%) were born into families in the alternative lifestyle recruitment group. Parents of children from the alternative recruitment group less often reported a physician diagnosed asthma (6.6% compared to 11.1%), as did their GP (8.2% compared to 12.9%). Medication use was also slightly lower in the alternative recruitment group (parent reported 6.6% vs 8.4%; GP reported 6.0% vs 6.6%). The agreement of the parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP recorded asthma diagnosis was comparable, while the agreement of asthma medication use was higher in the conventional recruitment group (results in supplemental file).

Discussion

This study shows that there is moderate agreement between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP reported childhood asthma. The discrepant cases revealed several difficulties in reporting physician diagnosed asthma, for example because of a recent diagnosis, or because they were still in the diagnostic process at the time of reporting. But the most striking discrepancies were noted in children where an asthma diagnosis was set at an early age: both parent reports and GP records had difficulties when reporting these cases. Several explanations are possible: it is possible that parents don’t remember an early asthma diagnosis (especially when the child does not have any asthma symptoms anymore: recall bias), or that the GP did not look back far enough in the medical chart. An important reason could also be misclassification of transient early wheeze as asthma diagnosis. Several parents reported their struggle with the words used by their physician. One parent quoted: “I don’t know if the doctor called it asthma, but [my child] wheezed at the age of 2 years, for which he was prescribed puffs”. It was noteworthy that in case of transient wheeze at a young age, a part of the parents did put down “was ever diagnosed with asthma by a physician”, while others did not, or left the question open. One parent noticed: “my family doctor does not make a diagnosis of asthma before the age of 6 years”. This shows that it is very important that physicians speak the same language in describing (viral induced) wheeze and asthma. In this study, we noticed that also GPs struggled with asthma diagnoses at an early age. It has to be noted that these asthma diagnoses were set more than ten years ago, and possibly due to new developments and schooling in childhood asthma would have been recorded as early transient or preschool wheeze nowadays.

The differences in the asthma medication reported by the parents compared to the GP can be caused by different issues: it is possible that medication was requested by the parents but not used in absence of asthma symptoms, or that the timing of the parent reported asthma medication use and GP records did not match completely. In other cases where the parents reported asthma medication use while the GP did not, it is possible that the asthma medication was prescribed by another physician than the GP, especially when there were asthma symptoms or current asthma. It is plausible that these children were referred to a pediatrician who prescribed the asthma medication (and the GP was not notified, the notification letter was not entered in the GP’s record, or was not reported in the GP’s questionnaire).

Earlier studies showed an increasing agreement between parent reported wheezing and GP recorded asthma diagnosis with increasing age, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.57 at age 7, and 0.61 at age 11 (Citation13). Other studies compared parent reported asthma or wheeze with clinical assessment of asthma. Hansen et al. found a good agreement (kappa 0.80) between parent reported asthma diagnosis ever in school children compared to clinical assessment, consisting of a standardized interview, a clinical examination, skin prick tests, blood samples, spirometry, exercise treadmill test, and measurement of exhaled nitrogen oxide (Citation14). Hederos et al. compared parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and symptoms in preschool children with hospital records of admissions and visits to the outpatient clinic, and concluded that only half of the individual patients identified as asthmatic by questionnaires were the same as those identified clinically (Citation15). When comparing parent reported physician diagnosed asthma with health care registry data, agreement was moderate to good (Cohen’s kappa 0.57) in a Swedish study (Citation16). The combination of ISAAC questions of recent wheeze and use of asthma medication in the last 12 months was highly comparable with the Finnish registration of medication reimbursement (Citation17). What this study adds, is an insight of the discrepancies between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and asthma medication use compared to GP records. This study shows that the discrepant cases are often caused by early transient wheeze that can be prematurely labeled as an asthma diagnosis. This could lead to an overestimation of asthma prevalence when using (parent reported) physician diagnosed asthma. This issue can be solved by using the definition current asthma, built up from a combination of asthma questions, such as ISAAC or MeDALL based definition. In this study, we found only minor differences between how these two definitions classified the children. Both definitions of current asthma were able to differentiate between early transient wheeze and asthma, while (parent reported) physician diagnosed asthma could not. This suggests that (parent reported) physician diagnosed asthma is better not used as stand-alone question for determining asthma prevalence in epidemiological studies.

The most important strength of this study is the repeated and detailed information on parent reported asthma questions, prospectively from birth onwards, which allowed this study to elaborate on the discrepancies between the parent reported data and GP recorded data.

Limitations of this study are that the timing of the questionnaire sent to the GP was not exactly at the same time as the questionnaires were sent to the parents; this could implicate that a very recent asthma diagnosis was not yet known at the time of filling out the questionnaire by the parents. It is also possible that the information in the GP record was not complete, or that the GP did not look far enough in the medical record. This appeared to be the case especially for the asthma medication. We assumed that the GP would have all the available information on asthma diagnosis and medication, but it is thinkable that when a child is referred to a pediatrician that the GP does not have complete information. It is also possible that the parents and child changed their GP without handing-over of the medical record, so that we missed part of the medical history.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study showed only moderate agreement between parent reported physician diagnosed asthma and GP recorded childhood asthma and demonstrated some difficulties in classifying physician diagnosed asthma. When using (parent reported) physician diagnosed asthma for epidemiological research, it is important to be informed on the timing of the diagnosis, and especially whether the asthma symptoms were transient or still present. Preferably, combined questions on current asthma are used in order to define asthma in epidemiological studies. Both ISAAC based and MeDALL based definitions of current asthma give valuable information on asthma symptoms and medication use, and are more accurate than merely an asthma diagnosis ever.

Supplemental_file.docx

Download MS Word (19.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the children and parents of the KOALA birth cohort study, and their GPs for participating in this study. We also want to thank Michelle van Dijke-Florijn, Dianne de Korte-de Boer, Jeroen van de Pol and Judith Lubrecht for their help in the collection and processing of the GP data.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no potential conflict of interest.

Data sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ME, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO Asthma. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma.

- Gaillard EA, Kuehni CE, Turner S, Goutaki M, Holden KA, de Jong CC, Lex C, Lo DK, Lucas JS, Midulla F, et al. European Respiratory Society clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis of asthma in children aged 5-16 years. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(5):2004173. doi:10.1183/13993003.04173-2020.

- Pekkanen J, Pearce N. Defining asthma in epidemiological studies. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(4):951–957. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d37.x.

- Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, Mitchell EA, Pearce N, Sibbald B, Stewart AW, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):483–491. doi:10.1183/09031936.95.08030483.

- Sá-Sousa A, Jacinto T, Azevedo LF, Morais-Almeida M, Robalo-Cordeiro C, Bugalho-Almeida A, Bousquet J, Fonseca JA. Operational definitions of asthma in recent epidemiological studies are inconsistent. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:24. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-4-24.

- Pinart M, Benet M, Annesi-Maesano I, von Berg A, Berdel D, Carlsen KCL, Carlsen K-H, Bindslev-Jensen C, Eller E, Fantini MP, et al. Comorbidity of eczema, rhinitis, and asthma in IgE-sensitised and non-IgE-sensitised children in MeDALL: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(2):131–140. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70277-7.

- Gehring U, Wijga AH, Hoek G, Bellander T, Berdel D, Brüske I, Fuertes E, Gruzieva O, Heinrich J, Hoffmann B, et al. Exposure to air pollution and development of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis throughout childhood and adolescence: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(12):933–942. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00426-9.

- Kummeling I, Thijs C, Penders J, Snijders BEP, Stelma F, Reimerink J, Koopmans M, Dagnelie PC, Huber M, Jansen MCJF, et al. Etiology of atopy in infancy: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16(8):679–684. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00333.x.

- Bastiaanssen JM, de Bie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Heuts A, Kroese ME, Essed GG, van den Brandt PA. Etiology and prognosis of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain; design of a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:1. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-5-1.

- Bindels PJ, van de Griendt EJ, Tuut MK, Steenkamer TA, Uijen JH, Geijer RM. Dutch College of General Practitioners’ practice guideline ‘Asthma in children’. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2014;158:A7935.

- Eijkemans M, Mommers M, Remmers T, Draaisma JMT, Prins MH, Thijs C. Physical activity and asthma development in childhood: prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(1):76–82. doi:10.1002/ppul.24531.

- Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. 1991.

- Griffiths LJ, Lyons RA, Bandyopadhyay A, Tingay KS, Walton S, Cortina-Borja M, Akbari A, Bedford H, Dezateux C. Childhood asthma prevalence: cross-sectional record linkage study comparing parent-reported wheeze with general practitioner-recorded asthma diagnoses from primary care electronic health records in Wales. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2018;5(1):e000260. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2017-000260.

- Hansen TE, Evjenth B, Holt J. Validation of a questionnaire against clinical assessment in the diagnosis of asthma in school children. J Asthma. 2015;52(3):262–267. doi:10.3109/02770903.2014.966914.

- Hederos CA, Hasselgren M, Hedlin G, Bornehag CG. Comparison of clinically diagnosed asthma with parental assessment of children’s asthma in a questionnaire. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(2):135–141. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00474.x.

- Hedman AM, Gong T, Lundholm C, Dahlén E, Ullemar V, Brew BK, Almqvist C. Agreement between asthma questionnaire and health care register data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(10):1139–1146. doi:10.1002/pds.4566.

- Nwaru BI, Lumia M, Kaila M, Luukkainen P, Tapanainen H, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, Pekkanen J, Klaukka T, Veijola R, et al. Validation of the Finnish ISAAC questionnaire on asthma against anti-asthmatic medication reimbursement database in 5-year-old children. Clin Respir J. 2011;5(4):211–218. doi:10.1111/j.1752-699X.2010.00222.x.