Abstract

In food industry, nanotechnology has been an attractive technology that can revolutionize the food sector ranging from food processing to food packaging, safety, and finally, shelf-life extension. Herein, the consumer perception of nanoparticles’ use in the food industry is a determining factor in their successful implementation and commercialization. The European Union (EU) Commission and the Federal Office of Public Health in Switzerland made it mandatory for food producers to provide transparent information on the ingredients, including synthetic nanoparticle content. Therefore, it is imperative to determine the current state of the public’s perception and opinion on the use of nanoparticles in the food industry. In this report, an overview of current legislations is given. In addition, health risk concerns and public opinion are critically discussed with a focus on information gained by a small convenience survey in the French-speaking part of Switzerland.

Introduction

Nanotechnology is a key technology for innovative and sustainable products in medicine and pharmaceuticals, in agriculture and throughout the industry (Bastus and Puntes Citation2018; Maynard et al. Citation2006). Man-made nanoparticles are already widely used in our daily lives. There is a broad range of different types of nanoparticles, each with a distinctive physicochemical composition, size distribution, and shape that allows them to be used for a variety of unique applications (e.g. anti-caking agents in powders, mineral UV filters in sunscreens, pigments for coloring). The addition of nanoparticles to food can result in a variety of benefits in the health, sensory, and safety areas and has the potential to increase shelf life, nutrition, and overall appeal of foods (Chen, Seiber, and Hotze Citation2014; Rhodes Citation2014).

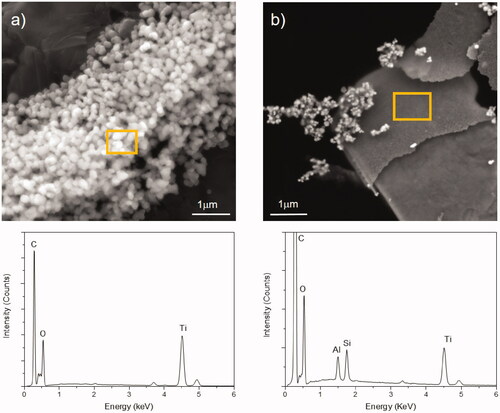

For example, some nanoparticles have been developed to increase the nutritional value of food: reducing the size of vital nutrients can allow more to be added without adversely affecting a food. Also, Vitamin E nanoparticles are used in beverage applications (Chen and Wagner Citation2004) or antioxidant nanoparticles made of ethyl cellulose encapsulated with poor water-soluble gamma oryzanol, providing a system with a controlled release of the antioxidant into the food (Ghaderi et al. Citation2014). Artificially produced inorganic (nano)particles, i.e. synthetic (nano)particles, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2) or silicon dioxide (SiO2) can also be found in food products (). These food additives have been labeled on products for years as E-numbers under E171 for TiO2 and E551 for SiO2 (RIKILT and JRC Citation2014). TiO2 is particularly used as a colorant in foods such as sweets, candies, and chewing gums (Weir et al. Citation2012). Silicon dioxide is used in the form of synthetic amorphous silica. Its main purpose in the food industry is to improve flow in viscous products or to prevent 'caking ' in powdered products. It is also used as a thickener in pastes, as a carrier of flavors, and as an agent for clarifying beverages and controlling foam formation (Peters et al. Citation2012).

Figure 1. Nanoparticle analysis in food products containing nanoparticles. Scanning electron micrographs with corresponding energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy to analyze the chemical composition of the observed particles of (a) a chocolate product containing TiO2 particles and (b) of candies containing talc (hydrated magnesium silicate) and TiO2 particles. Images courtesy Dr. Miguel Spuch-Calvar.

Nanoparticles and legislation

In 2011, the European Commission adopted the following recommendation for the definition of nanomaterials/nanoparticles (European Commission Citation2011).

‘Nanomaterial is either a natural, a process-derived or a manufactured material containing particles in an unbound state, as an aggregate or as an agglomerate, and in which at least 50% of the particles in the number size distribution have one or more external dimensions in the range 1 to 100 nanometers (nm).’

Nanomaterials exhibit at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nm. For nanoparticles, all three dimensions measure between 1 and 100 nm. To classify a material as ‘nano’ for legislative and policy purposes in the European Union (EU), the official recommended definition must be applied.

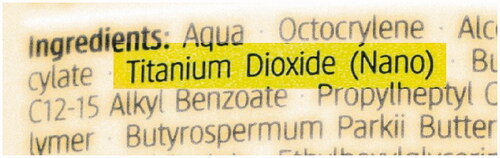

Regulatory bodies have started dealing with the potential risks posed by nanoparticles since many years. In 2004, the EU has been developing a regulatory policy to tighten control and to improve regulatory adequacy and knowledge of nanotechnology risks. Currently, specific provisions on nanomaterials have been introduced for biocides, cosmetics, food additives, food labeling, and materials in contact with foodstuff (Baran Citation2016; Karlaganis et al. Citation2019). Thus, as stipulated in the EU Cosmetics Regulation 1223/2009 (Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products, Off.J. EU 2009: L 342, 22.12.2009, p. 59-209), all ingredients that are present as nanoparticles (if intentionally added) must be labeled on the packaging with the term (nano) in parentheses (). In addition, with its Food Regulation 1169/2011, the EU has introduced a labeling requirement for food and cosmetic products containing nano: ‘All ingredients present in the form of synthetic nanomaterials must be clearly listed in the list of ingredients. The name of such ingredients must be followed by the word “nano” in parentheses.’ Thus, both regulations are intended to ensure that manufacturers inform consumers about these ingredients (Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers … Off. J. EU 2011, L 304, 22.11.2011, p 18-63.).

Figure 2. Ingredients present as nanoparticles have to be indicated on the package with the term ‘nano’ in brackets, i.e. (nano).

In Switzerland, the SR 817.023.31 Ordinance of the FDHA on Cosmetic Products (OCos) of 16 December 2016 (as at 1 July 2020) states in detail the definition of nanomaterials, the identification, and the labeling in cosmetic products (https://fedlex.data.admin.ch/filestore/fedlex.data.admin.ch/eli/cc/2017/165/20200701/de/pdf-a/fedlex-data-admin-ch-eli-cc-2017-165-20200701-de-pdf-a.pdf; accessed 4.5.2021). Then, the Chemicals Ordinance, the Biocidal Products Ordinance, the Plant Protection Products Ordinance and the Food Law contain specific requirements for nanoparticles (https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/gesund-leben/umwelt-und-gesundheit/chemikalien/nanotechnologie/rechtsetzung-und-vollzug/geltendes-recht.html; accessed 4.5.2021). More specifically, the SR 817.022.16 Ordinance of the Swiss Federal Department of Home Affairs (FDHA) regarding food labeling of 16 December 2016 (as of 1 July 2020) states in Section 3: List of ingredients, Article 8: that ‘Ingredients in the form of engineered nanomaterials shall be marked with the word ‘nano’ in brackets’ (https://fedlex.data.admin.ch/filestore/fedlex.data.admin.ch/eli/cc/2017/158/20170501/de/pdf-a/fedlex-data-admin-ch-eli-cc-2017-158-20170501-de-pdf-a.pdf; accessed 4.5.2021). From 2021, food manufacturers in Switzerland will now also have to indicate whether a product contains synthetic nanoparticles if this additive is intentionally added.

Health risk concerns

As mentioned above, synthetic nanoparticles in food must be labeled as additives under the appropriate E-number. The E-numbers designate food additives that are approved in the EU and Switzerland and do not indicate a potential hazard. It is important to note that legislation and regulatory authorities require that only harmless (i.e. safe for the consumer) food additives are allowed. Therefore, all additives are tested and must be approved by the legislator (https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-additives; accessed 4.5.2021).

However, there are critical voices highlighting the potential health risk of synthetic nanoparticles (Winkler, Suter, and Naegeli Citation2016). One example which is currently controversially discussed is TiO2. The use of anatase TiO2 has been approved by the US FDA in 1966 by allowing levels up to 1% in food (FDA (Food and Drug Agency). 2015. Summary of Color Additives for Use in the United States in Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics, and Medical Devices [Online]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/forindustry/coloradditives/coloradditiveinventories/ucm115641.htm. Accessed on 17 February 2021.) and has been accepted as a food additive in the EU for decades. Since 2004, also rutile, i.e., another form of titania, is allowed (EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). 2004. Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Food Additives, Flavorings, Processing Aids and materials in Contact with Food on a request from the Commission related to the safety in use of rutile titanium dioxid). The possible health concerns that came up recently are mainly based on some animal studies. These showed that, for example, orally ingested TiO2 particles added to drinking water impaired the immune system in animals, as well as triggering changes in the intestinal mucosa (Bettini et al. Citation2017). However, these studies, like all animal studies, have weaknesses, which have been addressed by other studies. Here, TiO2 nanoparticles were added to the feed, and no effects on the immune system and changes in the intestinal mucosa were found (Blevins et al. Citation2019). In addition to animal studies, efforts are ongoing in the field of quantitative risk assessment. Such risk assessment studies include approaches such as (i) based on intake, i.e. external doses, and (ii), based on internal organ concentrations using kinetic models in order to account for accumulation over time described by Heringa and colleagues (Heringa et al. Citation2016). Although the second approach resulted a potential risk for accumulation of nanoparticles in secondary organs, the study concludes that there is nothing that suggests TiO2 nanoparticles are a health concern, even in the long term.

The statements about possible effects of nanoparticles in food are therefore very controversial at the moment and difficult to understand for the consumers. Therefore, it is important to consult the conclusions and recommendations of the authorities. In recent years, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has evaluated all available studies on effects in animals of nanoparticles used in food. As a result, the authority concluded that the existing data do not raise concerns for human health, taking into account the low oral bioavailability of nanoparticles and thus the low exposure. EFSA recommended that further studies be conducted to fill existing data gaps regarding potential effects. This should enable the derivation of an acceptable daily intake level of the food additive E171 (https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/160914; accessed 4.5.2021). The German Federal Office for Risk Research (BfR) also considers EFSA's conclusion to be comprehensible (https://mobil.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/titandioxid-es-besteht-noch-forschungsbedarf.pdf; accessed 4.5.2021). In May 2021, the EFSA has updated its safety assessment of E171 and concluded that titanium dioxide cannot longer be considered safe when used as a food additive taking into consideration many thousands of studies (https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/titanium-dioxide-e171-no-longer-considered-safe-when-used-food-additive; accessed 05.07.2021). It is stated, that the ‘EFSA’s scientific advice will be used by risk managers (the European Commission, Member States) to inform any decisions they take on possible regulatory actions’. In addition to the authority consultations, there is an urgent need to establish standardized and accepted provided by international authorities guidelines for thorough characterization of synthetic nanoparticles in food products (Musial et al. Citation2020).

These risks and scientists’ ever-evolving understanding of nanoparticles are sources of concern for the public. Thus, clear and open communication between the public and scientists is key for the continued use of nanoparticles in food products, as well as funding of research into their applications. Keeping consumers safe and educated on the effects of nanoparticles in their food is the responsibility of the government, academia, and food industry (Schmid and Riediker Citation2008).

Safe handling of nanomaterials in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the safety of nanomaterials is under intense discussion in science, politics, and federal offices. In April 2008, for example, the Federal Council adopted the ‘Synthetic Nanomaterials Action Plan.’ Its aim is to create legal foundations for the safe handling of nanomaterials (https://www.bafu.admin.ch/dam/bafu/de/dokumente/chemikalien/ud-umwelt-diverses/aktionsplan_synthetischenanomaterialien.pdf.download.pdf/aktionsplan_synthetischenanomaterialien.pdf; accessed 4.5.2021). The action plan compiled information on the opportunities and risks of nanotechnology for a public dialogue. It provided the basis for in-depth research, such as the National Research Program ‘Opportunities and Risks of Nanomaterials’ (NRP64) and initiated the development of the precautionary matrix for synthetic nanomaterials.

The action plan was completed in 2019. The conclusions and recommendations are available on the website of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) (https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/chem/nanotechnologie/2019-schlussbericht-br-aktionsplan-nano.pdf.download.pdf/2019-schlussbericht-br-aktionsplan-nano-de.pdf; accessed 4.5.2021).

The findings from the action plan led to the establishment of two new service platforms in Switzerland. They are to pursue the promotion of the safe and sustainable handling of nanomaterials. For example, in 2018, the national and independent contact point contactpointnano.ch was founded under the leadership of Empa (https://contactpointnano.ch/; accessed 4.5.2021). In 2020, the analytics platform 'Swiss NanoAnalytics' was created at the Adolphe Merkle Institute (AMI) of the University of Fribourg (https://www.ami.swiss/en/nanoanalytics/; accessed 4.5.2021). The platform offers a service-oriented service for the characterization of nanomaterials, for example in cosmetic products, food or new drugs. This expertise for industry and authorities is particularly important in view of the mandatory declaration of nanomaterials in food, which is valid since May 2021.

Public perception and opinion

One of the primary goals of nanoparticle-related legislation is to inform the public about what they are eating and to ensure public safety for the consumers. Therefore, it is important that the public has access to the knowledge and knows and understands what nanoparticles are, what their benefits and risks are, and what the current legislation is, so they can make an informed decision. It also has been recommended that customer opinion be considered in the process of product design, development, and commercialization of various food applications containing nanoparticles (Frewer et al. Citation2014). Such a process will support consumer acceptance.

Over the past decade, a lot of research worldwide was and is focusing on the potential health and environmental risks presented by nanoparticles. In the past few years, efforts have been made to make research more accessible to the public. Despite this effort to further public knowledge, it seems that much of the research is still not known by the general public. Another aspect is that nanoparticle labeling of products can reduce consumers’ benefit perception and increase their perception of risk, as shown in a study in which participants were given sunscreen images with and without labeling (Siegrist and Keller Citation2011).

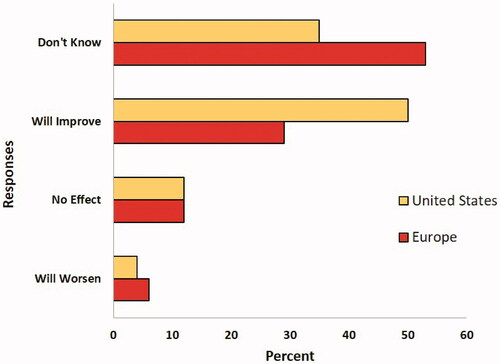

The general public seems to be accepting nanoparticles in food, but there is still concern about their presence in food products due to possible health risks (Belli Citation2012). This concern is very dependent on location and knowledge of an individual and Gaskell and colleagues compared public perceptions of technologies in the United States and Europe (Gaskell et al. Citation2005). Interestingly, they have shown that people in the US are more optimistic than Europeans about familiar technologies. By contrast, in Europe there is more concern about the impact of technology on the environment, less commitment to economic progress and less confidence in regulation. shows the results from this paper of the polls performed in the United States and in Europe.

Figure 3. Public opinion of nanoparticles on daily life in the United States and Europe. Graph of poll results from data published with permission by Public Understanding of Science, Gaskell et al. (Citation2005).

Participants were asked if they thought nanoparticles could improve their daily lives. As seen in the figure, the most common responses were ‘yes, it will improve’ and ‘don’t know,’ with nearly opposite results in the US as in Europe. Despite the lack of knowledge of what nanoparticles are, U.S. consumers are willing to purchase products that are described as containing nanoparticles (Kuang et al. Citation2020). The study presented different samples of chocolate ice cream and cherry tomatoes to participants who said they enjoy those products. When given the samples, the participants were told they included nanoparticles even though they did not. They were informed of the benefits the nanoparticles purportedly provided and were asked to rank their enjoyment of the product. In the end, participants were asked a number of questions, one of which addressed their willingness to purchase food products enhanced by nanoparticles. Less than 20% of participants answered that they would be unwilling to purchase those products. The reasoning of those who were unwilling was ‘not in objection to the technology; instead, they quite literally expressed their distaste for the products they believed to be produced with nanomaterials’.

Current perception and opinions held by a small convenience sample of the Swiss public on nanoparticles in food

To determine the current public opinion and perception of nanoparticles in Switzerland, a survey was performed from August to October 2020 within a convenience sample using the University of Fribourg’s email list and members of the Adolphe Merkle Institute. This email survey included some general background questions (SI 1) and one question that asked participants to freelist: ‘Would you please list all of the things that you can think of when you hear ‘nanoparticles in food’?’ The survey was sent out in English, German, and French and also included a few demographic questions. The data from the survey’s freelist question was analyzed by sorting the items listed in the responses into broad categories. The idea with this question on nanoparticles in food was to get a sense of what the general public associates with ‘nanoparticles’ and to let them to express their opinion on this topic without any guidance or direction. With this approach, it was possible to get an unbiased opinion from this convenience sample, who might have heard very limited or nothing about the topic.

A preliminary analysis of the responses to determine the categories in which the responses were sorted into was performed. The categories used were as follows:

material residue

safety/heath

environment

foods/additives

unknown (meaning the participant responded that they knew little or nothing about nanoparticles in food),

applications

Additionally, each response to the freelisting question was also evaluated based on overall tone and categorized as positive, positive-neutral, neutral, negative-neutral, or negative. These categories were then compared graphically to determine the things our sample thinks of most when they hear ‘nanoparticles in food’ and the most common tone taken in the responses.

Demographic information about participants was also recorded including age, highest level of education achieved, and if the participant worked or studied in a field related to nanoparticles. The majority of participants surveyed were 24 and under (68%) and many of them were currently in pursuit of a bachelor’s or master’s degree. The population surveyed was highly concentrated with young people currently studying at a college level. Of those surveyed, 92% did not work or study in a field related to nanoparticles.

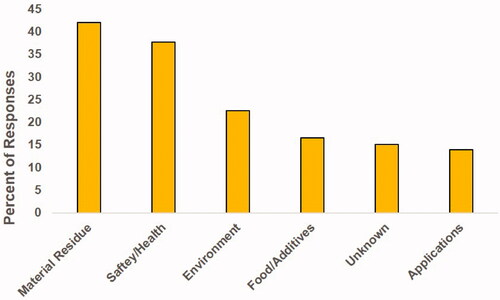

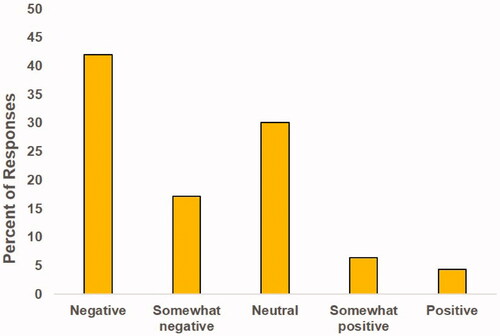

The results of this survey align with the results of the content analysis. The survey revealed that a large portion of those surveyed knew very little about nanoparticles or mentioned microplastics that are not intentionally added to food products. The survey received 279 responses and responses to the question: ‘Would you please list all of the things that you can think of when you hear ‘nanoparticles in food’?’ These responses varied from one word to a few sentence answers. The topics covered and the overall connotation of each response was recorded and compiled. and summarize the overall data.

Figure 4. Freelisting survey: Summary of topics covered in the survey response. Many participants listed multiple topics, which were tallied separately.

Figure 5. Freelisting survey: Summary of the connotation of responses. Each response was assigned a connotation.

As shown in , over 40% of the participants listed different types of material residue that inevitably ended up in food, which include heavy metals and plastics. One hundred out of the 279 responses listed plastic. Interestingly the second most commonly listed topic in the freelisting survey was the concern about the safety/health impacts of nanoparticles in food. The majority of these concerns were about microplastics, even though they are not nanoparticles nor are they specifically added to food. The third most commonly listed topic was related to the environment. The responses did not specify if the perception is good or bad in general for nanoparticles, and the majority of these responses were concerns about pollution related to microplastics. The most commonly mentioned topic that did not pertain mainly to microplastics is labeled in as ‘Food/Additives.’ This is when a specific nanoparticle additive or food containing nanoparticles was mentioned, but even a few of these responses included comments on microplastics. From these responses it is evident that those surveyed are conflating microplastics that end up in food with nanoparticles that are purposefully added into food. Additionally, 15% of respondents said that they did not know much if anything about nanoparticles in food. Only 14% of respondents listed any specific application of nanoparticles, so it is clear that the benefits nanoparticles can provide are not being widely advertised.

The general opinion of respondents to the survey on nanoparticles in food was determined by the ‘connotation,’ the overall tone of each participant’s response, from negative to positive (). Overall, the majority of responses were negative or neutral, very few people had a positive or slightly positive response (10.8%). It is also important to consider that a number of the responses were about microplastics or other material residues in food, and not specifically about engineered nanoparticles that are added intentionally to food. This means that the survey response may not reflect the public’s opinion on nanoparticles in food, because they may not have understood what nanoparticles are. Furthermore, the responses that more accurately listed information on nanoparticles tended to be more positive than the overall results.

This small convenience survey in Switzerland with a focus on Fribourg showed that the public have limited knowledge of intentionally added nanoparticles in food products. The majority of the public’s opinion of nanoparticles in food is negative or neutral, but this opinion is probably due to the current discussion on micro – and nanoplastic pollution in general, maybe also due to nanoparticles in food’s relatively low amount of coverage in mass media, while microplastics are mentioned much more frequently. Due to this media coverage frequency, the convenience sample group associates any small particle with pollution and plastics accumulating into food. The limited knowledge about nanoparticles and their various applications was already highlighted by Gupta and colleagues in 2015 (Gupta, Fischer, and Frewer Citation2015). They showed that even in the absence of risk information related to nanoparticle applications, consumers spontaneously consider moral, ethical, and social risk aspects when discussing the usefulness of nanoparticles in consumer products, which had not been addressed by experts.

The limit of this study is that the specific population subgroup (e.g. E-mail list from University of Fribourg) is small and the insights gained, although interesting, are minimal. In a next step, it is important to extend such a survey to other regions in Switzerland to determine the opinion of the Swiss public as a whole. In addition, the stakeholder group should be broader to include the food industry and regulators, not just customers. An example for such a broader study is described by Hartmann and colleagues, who conducted a survey to compare prioritization of food hazards from experts, producers and consumers in the German- and French-speaking part in Switzerland (Hartmann, Hubner, and Siegrist Citation2018). This study showed no difference between the cultural regions, but the average ranking of hazards differed between experts and producers/consumer.

Conclusion

Synthetic nanomaterials have an enormously broad application potential and can contribute with new or improved properties to food. It is important to keep questioning the safety of these materials and to discuss them with experts from various fields, as well as to consult the recommendations of the authorities. The mandatory labeling of ‘nano’ in food will certainly stimulate the public debate again. Food additives such as synthetic nanoparticles will only be approved if they are safe. Based on current knowledge, authorities say there is no cause for health concern. It is important to continue to examine the topic objectively and competently from all sides in order to sustainably exploit the potential of the technology and at the same time ensure safe handling. In addition, the public has to be better informed and it is recommended that communication needs to improve the understanding of what nanoparticles are and why they are used in certain products.

Author contributions

BR-R and AP-F conceived the review idea and proposed the student work for MB and RH. MB and RH performed a literature research and did the survey in Switzerland. AM supervised MB and RH and revised the survey. BR-R and AP-F wrote the manuscript through contribution from all co-authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding from the Adolphe Merkle Foundation. The authors also thank Worcester Polytechnic Institute for the support, coordination, and advisement of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Baran, Agnieszka. 2016. “Nanotechnology: legal and Ethical Issues.” Ekonomia i Zarzadzanie 8 (1): 47–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/emj-2016-0005.

- Bastus, N. G., and V. Puntes. 2018. “Nanosafety: Towards Safer Nanoparticles by Design.” Current Medicinal Chemistry 25 (35): 4587–4601. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867324666170413124915.

- Belli, B. 2012. “Eating Nano: Processed Foods and Food Packaging Already Contain Nanoparticles - Some of Which Could be Harmful to Our Health.” The Environmental Magazine Website. Available online at: https://emagazine.com/eating-nano/

- Bettini, S., E. Boutet-Robinet, C. Cartier, C. Comera, E. Gaultier, J. Dupuy, N. Naud, et al. 2017. “Food-Grade TiO2 Impairs Intestinal and Systemic Immune Homeostasis, Initiates Preneoplastic Lesions and Promotes Aberrant Crypt Development in the Rat Colon.” Scientific Reports 7: 40373 doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40373.

- Blevins, L. K., R. B. Crawford, A. Bach, M. D. Rizzo, J. Zhou, J. E. Henriquez, Dmio Khan, et al. 2019. “Evaluation of Immunologic and Intestinal Effects in Rats Administered an E 171-containing diet, a food grade titanium dioxide (TiO2)).” Food Chem Toxicol 133: 110793 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2019.110793.

- Chen, C. C., and G. Wagner. 2004. “Vitamin E Nanoparticle for Beverage Applications.” Chemical Engineering Research and Design 82 (11): 1432–1437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1205/cerd.82.11.1432.52034.

- Chen, H., J. N. Seiber, and M. Hotze. 2014. “ACS Select on Nanotechnology in Food and Agriculture: A Perspective on Implications and applications.” J Agric Food Chem 62 (6): 1209–1212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jf5002588.

- European Commission. 2011. “Commission Recommendation of 18 October 2011 on the Definition of Nanomaterial.” Official Journal of the European Union 2011/696/EU: 38–40.

- Frewer, L. J., N. Gupta, S. George, A. R. H. Fischer, E. L. Giles, and D. Coles. 2014. “Consumer Attitudes towards Nanotechnologies Applied to Food Production.” Trends in Food Science & Technology 40 (2): 211–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2014.06.005.

- Gaskell, George, Toby Ten Eyck, Jonathan Jackson, and Giuseppe Veltri. 2005. “Imagining Nanotechnology: cultural Support for Technological Innovation in Europe and the United States.” Public Understanding of Science 14 (1): 81–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662505048949.

- Ghaderi, S., S. Ghanbarzadeh, Z. Mohammadhassani, and H. Hamishehkar. 2014. “Formulation of Gammaoryzanol-Loaded Nanoparticles for Potential Application in Fortifying Food Products.” Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin 4 (Suppl 2): 549–554. doi:https://doi.org/10.5681/apb.2014.081.

- Gupta, N., A. R. Fischer, and L. J. Frewer. 2015. “Ethics, Risk and Benefits Associated with Different Applications of Nanotechnology: A Comparison of Expert and Consumer Perceptions of Drivers of Societal Acceptance.” Nanoethics 9 (2): 93–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-015-0222-5.

- Hartmann, C., P. Hubner, and M. Siegrist. 2018. “A Risk Perception Gap? Comparing Expert, Producer and Consumer Prioritization of Food Hazard Controls.” Food and Chemical Toxicology. 116 (Pt B): 100–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2018.04.006.

- Heringa, M. B., L. Geraets, J. C. van Eijkeren, R. J. Vandebriel, W. H. de Jong, and A. G. Oomen. 2016. “Risk Assessment of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles via Oral Exposure, Including Toxicokinetic Considerations.” Nanotoxicology 10 (10): 1515–1525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17435390.2016.1238113.

- Karlaganis, Georg, Rachel Liechti, Sirasak Teparkum, Pavadee Aungkavattana, and Ramjitti Indaraprasirt. 2019. “Nanoregulation along the Product Life Cycle in the EU, Switzerland, Thailand, the USA, and Intergovernmental Organisations, and Its Compatibility with WTO Law.” Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry 101 (7-8): 339–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02772248.2019.1697878.

- Kuang, Lina, Brenda Burgess, Cara L. Cuite, Beverly J. Tepper, and William K. Hallman. 2020. “Sensory Acceptability and Willingness to Buy Foods Presented as Having Benefits Achieved through the Use of Nanotechnology.” Food Quality and Preference 83: 103922. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103922.

- Maynard, A. D., R. J. Aitken, T. Butz, V. Colvin, K. Donaldson, G. Oberdorster, M. A. Philbert, et al. 2006. “Safe Handling of Nanotechnology.” Nature 444 (7117): 267–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/444267a.

- Musial, J., R. Krakowiak, D. T. Mlynarczyk, T. Goslinski, and B. J. Stanisz. 2020. “Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products-What Do We Know about Their Safety?” Nanomaterials ( Nanomaterials ) 10 (6)doi: 1110. 3390/nano10061110. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10061110.

- Peters, R., E. Kramer, A. G. Oomen, Z. E. Rivera, G. Oegema, P. C. Tromp, R. Fokkink, et al. 2012. “Presence of Nano-Sized Silica during in Vitro Digestion of Foods Containing Silica as a Food Additive.” ACS Nano 6 (3): 2441–2451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/nn204728k.

- Rhodes, C. J. 2014. “Eating Small: applications and Implications for Nano-Technology in Agriculture and the Food Industry.” Science Progress 97 (Pt 2): 173–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.3184/003685014X13995384317938.

- RIKILT and JRC 2014. “Inventory of Nanotechnology Applications in the Agricultural, Feed and Food Sector.” EFSA Supporting Publication 2014:EN-621, 125 pp.

- Schmid, K., and M. Riediker. 2008. “Use of Nanoparticles in Swiss Industry: A Targeted Survey.” Environmental Science & Technology 42 (7): 2253–2260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/es071818o.

- Siegrist, M., and C. Keller. 2011. “Labeling of Nanotechnology Consumer Products Can Influence Risk and Benefit Perceptions.” Risk Analysis : An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 31 (11): 1762–1769. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01720.x.

- Weir, A., P. Westerhoff, L. Fabricius, K. Hristovski, and N. von Goetz. 2012. “Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products.” Environmental Science & Technology 46 (4): 2242–2250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/es204168d.

- Winkler, H. C., M. Suter, and H. Naegeli. 2016. “Critical Review of the Safety Assessment of Nano-Structured Silica Additives in Food.” Journal of Nanobiotechnology 14 (1): 44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-016-0189-6.