ABSTRACT

Currently, ketamine is the only legal psychedelic medicine available to mental health providers for the treatment of emotional suffering. Over the past several years, ketamine has come into psychiatric use as an intervention for treatment resistant depression (TRD), administered intravenously without a psychotherapeutic component. In these settings, ketamine’s psychedelic effects are viewed as undesirable “side effects.” In contrast, we believe ketamine can benefit patients with a wide variety of diagnoses when administered with psychotherapy and using its psychedelic properties without need for intravenous (IV) access. Its proven safety over decades of use makes it ideal for office and supervised at-home use. The unique experience that ketamine facilitates with its biological, experiential, and psychological impacts has been tailored to optimize office-based treatment evolving into a method that we call Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP). This article is the first to explore KAP within an analytical framework examining three distinct practices that use similar methods. Here, we present demographic and outcome data from 235 patients. Our findings suggest that KAP is an effective method for decreasing depression and anxiety in a private practice setting, especially for older patients and those with severe symptom burden.

Introduction

The development of a psychotherapy that uses ketamine as a medicine for conscious awareness is new and groundbreaking (Wolfson and Hartelius Citation2016). It coincides with promising clinical research with psilocybin and MDMA embedded in psychotherapies that are entering Phase III FDA trials (Feduccia, Holland, and Mithoefer Citation2018; Mithoefer, Grob, and Brewerton Citation2016). For now, ketamine is the only legally available psychedelic medication, along with cannabis.

Ketamine originated as an anesthetic drug in the late 1960s as an analog of phencyclidine. It has been a successful anesthetic and analgesic agent with far fewer adverse effects than the parent compound. Early in ketamine’s use, there were reports of an unusual side effect, a dissociative/hallucinatory state referred to as the “emergence phenomenon.” This was concerning because patients were not prepared for these vivid experiences and found them disturbing. It was dubbed a “dissociative anesthetic” by the wife of Edward Domino, the primary research clinician (Matthew and Zarate Citation2016).

Ketamine’s potential to treat psychological or psychiatric problems was first reported in Khorramzadeh and Lofty (Citation1973), and in Argentina as an adjunct for antidepressant psychotherapy (Fontana Citation1974). In Mexico, the psychiatrist Salvador Roquet introduced ketamine to patients in group settings as a component of his approach to psychedelic psychotherapy (Kolp et al. Citation2007; Yensen Citation2016). From Russia came reports of using ketamine for the treatment of addictions (Krupitsky and Grinenko Citation1997). Duly noted by those involved with psychedelic substances during this period prior to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s scheduling of substances, use of ketamine for self-exploration and in psychotherapeutic contexts had an ongoing but not extensive profile (Jansen Citation2004; Wolfson and Hartelius Citation2016).

Anecdotally, some practitioners noted that intramuscular ketamine sessions were followed by periods of relief from depressive and anxious states (Kolp et al. Citation2007). In the late 1990s, investigators at the National Institute of Mental Health began exploring the antidepressant potential of ketamine while searching for alternatives to the limited benefits of SSRIs and SNRIs (Berman et al. Citation2000; Krystal et al. Citation1994). Notably, however, their effort was focused on eliminating the psychedelic effects while retaining or enhancing the antidepressant properties. They concentrated on patients failing treatment on two or more conventional antidepressants (labeled Treatment Resistant Depression [TRD]), viewing this as a potential market with a social responsibility to provide effective treatment. Subsequently, a protocol for medicalized use involving an intravenous (IV) route of administration in which ketamine was infused at a rate of 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes emerged. After a single session of IV ketamine, investigators noted remission of TRD and a reduction of suicidality ((Krystal Citation2007). However, the benefit was short-lived. This led to a more intensive approach to providing treatment, tending towards an induction phase of six sessions over about two weeks' time, with further sessions occurring at various times depending on the practitioner. The strategy focused on dosing and frequency of ketamine administration to extend the duration of affective benefit (Cusin et al. Citation2012; Rot et al. Citation2015; Zarate et al. Citation2013).

Although researchers attempted to minimize ketamine’s unwanted dissociative effects, some degree of mind alteration would generally occur. However, studies from the IV researchers indicated enhanced benefit from the presence of psychedelic experiences (Luckenbaugh et al. Citation2014). These findings parallel the relationship between mystical experience and treatment outcome in the psilocybin studies (Griffiths et al. Citation2011), with both medicines providing altered, often profound psychedelic experience. This association suggests that profound psychedelic experiences, regardless of the medicine facilitating them, may improve mental health and overall well-being (Sullivan Citation2018). The psychiatric establishment has tended to avoid this understanding, and instead has attempted to discover a metabolite or analog of ketamine that lacks the psychedelic effects yet retains antidepressant effects. Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP) utilizes a dosage escalation strategy to achieve different levels of trance increasing to full out-of-body experiences. We believe that some degree of mind alteration is necessary for ketamine’s effects. No study to date has demonstrated that, absent some degree of perceived psychoactivity, there is an antidepressant effect (for a review of ketamine research for depression and other disorders, see Ryan, Marta, and Koek Citation2016).

In the mid-2000s, several office-based psychiatrists began administering intramuscular (IM) ketamine within a psychotherapeutic framework, in collaboration with referring therapists, or providing therapy themselves (Early Citation2016). With Stephen Hyde’s (Citation2015) publication of Ketamine for Depression in 2015, it became clear that ketamine could be administered using the sublingual, intranasal, or intramuscular routes (Chilukuri et al. Citation2014), raising the prospect that IV administration was unnecessary. In fact, other routes of administration allow the entire therapeutic dosing spectrum to occur in a non-medicalized office setting with full psychotherapeutic support (Jaitly Citation2013; Lara, Bisol, and Munari Citation2013).

Over decades, ketamine’s record of clinical safety in anesthesia and for analgesia, in emergency room settings, in outpatient pain management clinics, and now for psychiatric use, has produced an extensive body of clinical experience that supports its safety (Collins et al. Citation2010) for use in the office and for prescription use by patients at home. We use ketamine both in lower-dose sublingual administration for a trance experience that promotes interaction during the session and the transformational IM experience with its preparation, journey, and subsequent integration.

For over five years now, KAP has been in clinical development evolving a set of basic strategies and accumulating experience from several hundred patients and thousands of KAP sessions. We report here the results of three distinct KAP practices, each having matured in consecutive time frames. Given the evolving nature of KAP, there is a development of reporting as practices have settled on particular assessment measures and criteria. Over time, there has been an increase in available data and emphasis on patient self-reports. This has enabled the maturation of a dosing strategy into a replicable protocol. What is provided here is both a qualitative and quantitative expression and evaluation of our work to date.

The practices reporting here do not limit the use of KAP to only patients with TRD. KAP has been used for patients suffering from a variety of problems—relationship and existential issues including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Bipolar I and II depressive phases, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), psychological reactions to physical illness, personality disorders, life-threatening illnesses, and substance use co-occurring with a primary psychiatric disorder. We do not view ketamine as a stand-alone medicine fitting all possibilities. The encounter here is with practices addressing the human gamut with all the available tools of psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Ketamine as a medicine: A brief review

Ketamine is available in two enantiomers: the S (+) and the R (−) configurations. The S isomer is estimated to be approximately twice as powerful as the R (Weber et al. Citation2004). There is controversy in distinguishing a pattern of different effects between the two. Current pharmacological preparations include an equimolar racemic mixture of the two enantiomers. S (+) ketamine has just come to market with FDA approval as a patented antidepressant nasal preparation for in-office psychiatric use.

Multiple routes of administration are used by practitioners treating depression and other psychiatric conditions, each with its own unique pharmacokinetics. These include IV, IM, intranasal (IN), sublingual (SL), anal, and oral delivery. Each has its own rate of absorption and timing of onset. In our practices, new patients tend to begin with the SL method for assessment of sensitivity to the medicine.

Ketamine’s antidepressant activity is believed to stem from its antagonism of NMDA receptors within the glutamate neurotransmitter matrix. Based on animal models, it is believed that ketamine-induced synaptic potentiation and proliferation may play a key role in eliciting antidepressant effects. Ketamine also impacts other neurotransmitter systems, affecting cholinergic, monoaminergic, kappa opioid, and GABAergic function, most likely as downstream indirect effects (Wallach Citation2018). A recent paper describing the use of naltrexone in six patients receiving low-dose ketamine infusions (Williams et al. Citation2018) has created controversy as to the putative effects of ketamine on opiod receptors and the possible clinical implications. This has been contradicted by earlier, more thorough work by Krystal et al. in Citation2007; and by receptor research (Wallach Citation2018). It is our view that the antidepressant effect of ketamine is not the direct result of signaling via the opiate receptor.

The bioavailability of IM ketamine is similar (93−95%) to IV ketamine. SL ketamine absorption is variable and difficult to estimate but most likely in the range of 15–25%. IN ketamine absorption is higher at about 25–35%, depending on person and preparation. Oral absorption is much less efficient, at 10% or less, and takes more time to have its effect (Wieber et al. Citation1975). The swallowing of ketamine from SL or IN administration may result in a remote onset of ketamine’s effect when it does occur somewhere in the range of 45–75 minutes later.

Ketamine’s tolerability and safety have been demonstrated over almost five decades (Jaitly Citation2013). A pooled data study from three different clinical trials of subanesthetic IV ketamine administration in major depressive disorder (MDD) patients found that adverse effects common within the first four hours of administration included dizziness, derealization, and drowsiness (McGirr et al. Citation2014). Whether these are considered “adverse” or as part of ketamine’s actual effects that result in therapeutic benefit is the subject of debate. One third of all patients experienced transient hemodynamic changes, particularly elevated blood pressure. There have been no cases of persistent neuropsychiatric sequelae, medical effects, nor increased substance abuse in clinical practice. Use of a body weight schema for a determination of ketamine dosage is of limited clinical utility, as sensitivity to the medicine is idiosyncratic and only fully predictable with patient experience. Increasing the dosage of ketamine utilizing any of the routes of administration will result in an increase in dissociative effects.

The KAP experience: Trance and transformation

KAP’s effectiveness lies in several factors. Depending upon dose, ketamine promotes a time-out from ordinary, usual mind, relief from negativity, and an openness to the expansiveness of mind with access to self in the larger sense. These effects enhance a patient’s ability to engage in meaningful psychotherapy during and after administration. Ketamine is potent for respite, analysis, and meditative presence, and potent for recovery from depression and the lingering effects of trauma. For most patients, we begin with the sublingual induction of the trance state to find an individual “sweet spot” with respect to dosage that can be replicated at home under supervision and used in future in office sessions to aid in psychotherapy. We may then move to the IM experience of transformation based on the patient, producing an out-of-body experience which allows for a unique but related approach to healing. These two modes of treatment are outlined in .

Table 1. The KAP experience: Trance and transformation.

KAP is intensive, demanding, and rewarding for its practitioners and their patients. The long sessions, up to three hours, plus provision of supervised recovery for patients, can be fatiguing. As with any mind-altering experience, there are set and setting considerations. In our offices, we make every effort to provide a nest in the Winnicott sense, a place of safety and warmth (Carhart-Harris et al. Citation2018). Since the breakage of trust or the lack of its acquisition are so much at the core of trauma persistence, the behavior of therapists and their ability to bond with patients are at the heart of our psychotherapy (Van Der Kolk Citation2014). Long exposure to each other requires a more human, intimate, and disclosing posture by therapists while maintaining the boundary of “not needing” of our patients. Attachment wounds are best healed in a therapeutic environment that is reliable, compassionate, appears safe, and recognizes the vulnerability of its patients (Brown and Elliott Citation2016). An altered state is a vulnerable state. In recognition of this, we frequently work dyadically, enabling our patients to let down vigilance and journey freely and without concern for intrusion or violation. If two therapists (including an MD, FNP, or NP) are not available, we have another therapist present on premises. This practice is in accord with the method of MAPS MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Adaptation of different methods to psychedelic psychotherapy, such as Internal Family Systems (Schwartz Citation1995), is an opportunity for growth and creativity and for expansion of the theory and practice of such methods.

Maintenance of the observing self is fundamental to the success of our work and guides dosage selections. Our monitoring consciousness rides with the journey and comments at a fundamental level. It is accentuated and deepened as in profound meditative states. The journey tends to augment meditative ability and stability (Millière et al. Citation2018).

highlights the “signature” of the ketamine experience and therapeutic integrations.

Table 2. The ketamine signature.

In the freedom of an inward journey, absent the emotional constraints of ordinary mind and free of one’s sense of inherent form, a sense of vast space arises. The journey unfolds in different realities that may seem the truth of being, outside of time and space, as if observing our being in different realities. At times, this may be confusing as the experience may be intense with only the observing mind connecting to a sense of self.

This study is of KAP’s effectiveness in providing the means to personal elucidation which results in decrease in symptomatology. We call this anchoring the essential elements gained from the experience. This can take many forms, including slogans, mantras, visions, internal movies, feelings, metaphors, and understandings. This is about learning from the experience, bringing it as method to everyday life. In essence, we use the experiential component of the medicine to bring new perspective and the direct experience of seeing ourselves in a new way—the missing link that gives hope to many sufferers of mental illness and others who cannot achieve this critical reframing by other means.

Methods

All participants provided written informed consent. Three forms were developed for data collection by the Ketamine Research Foundation (KRF) Ketamine Data Project (KDP) using a Redcap research database: Intake, Visit, and Termination (when applicable). Chart data were inputted consecutively from all three practices. Where charts were incomplete, or the work was too limited to input, a list of these was generated with rationales for exclusion.

The forms contain demographic, diagnostic, medication, psychoactive history, psychiatric history, medical history, and family data. Rater views of personality rigidity, recommendations for ketamine administration, and concerns are included in the intake form. Self-report data collected before KAP treatment (baseline/intake) included the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A), Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), Childhood Resilience Scale (CRS), and Adverse Childhood Event Score (ACE). Follow-up self-report measures from the last available office visit included BDI, HAM-A, PHQ-9, and Levine Depression Scale Ratings. Rater view of patient’s symptoms as well as the quality of the KAP session experience were recorded. Change of State, Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ), and Ego Dissolution Index (EDI) (Nour et al. Citation2016) were used to assess KAP sessions.

During KAP treatment, patients received ketamine SL, IM, or both during their treatment course. SL ketamine was administered as either troche or a rapid-dissolve tablet during the initial in-office session to determine sensitivity and dose for the individual. Dose ranges were titrated in office and then adjusted at home to achieve and maintain access to the trance state described. This state facilitates psychotherapy sessions and individual reflection at home to maintain the therapeutic momentum, and cannot be determined by a weight-based protocol in our experience. Subsequently, SL ketamine was prescribed in a limited amount without refills for at-home use with instructions to use SL ketamine up to but not exceeding six sessions over a two-week period, with less frequency thereafter, depending on severity. Patients were instructed to replicate the setting and procedure demonstrated by the clinicians in the initial session at home. KAP sessions were generally held in the office usually two weeks apart, or more frequently depending on acuity. Different diagnoses have different frequencies for KAP and all of our practices are individualized. IM ketamine was administered during in-office sessions only, usually supported by ongoing SL sessions at home. IM doses were used to reach the transformational state described earlier in which out-of-body experiences are common and therapeutic. Not all patients moved on to use the IM route of administration, and this was determined at the discretion of the provider based on therapeutic progress and symptom relief.

Rater views of KAP effects proceed through the Visit and Termination forms, as does the history of administration. Raters provide their estimates of the presence and intensity of psychedelic effects and their impacts, sensitivity to ketamine, changes in symptoms and well-being, plus adverse effects, drug interactions, changes in medications, changes in diagnosis, and commentary of a psychodynamic and qualitative nature.

SAS software was used to analyze the data. Statistical tests used include correlations and moderation analyses. P-values were recorded and reviewed for clinical relevance by the authors.

Results

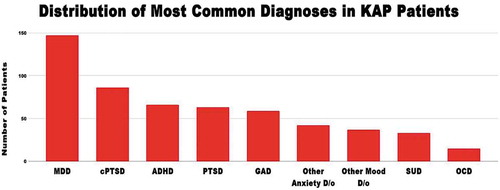

Data from 235 patients from three distinct private general psychiatric practices located in Northern California (Wolfson and Dore) and Austin, Texas (Turnipseed) from 2013–2018 were collected prospectively and analyzed retrospectively. Diagnoses among these KAP patients at intake are shown in .

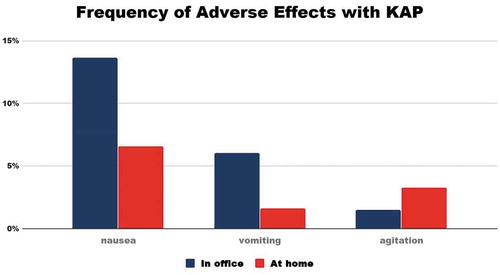

Frequency of Adverse Effects is shown in .

Figure 2. The most common side effects seen in our KAP population are nausea, vomiting, and agitation, which occur only in a small percentage of patients undergoing KAP treatment and rarely lead to discontinuation of the treatment.

Figure 1. Distribution of most common diagnoses in our sample population. At intake, patients underwent a full psychiatric evaluation by licensed mental health providers (MD/NP/therapist teams) who assessed whether patients meet diagnostic criteria according to the DSM-V. Diagnosis are listed: Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Developmental Trauma (cPTSD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Substance Use Disorder (SUD including Alcohol n = 14, Cannabis n = 11, Opioid n = 3, Inhalant n = 3, Cocaine n = 1, Nicotine n = 1, Stimulant n = 1, and Other psychoactive n = 5), Other anxiety disorder (Unspecified, Due to physiological cause, SAD, Agoraphobia, Panic), Other mood disorder (Bipolar Disorder, Unspecified, Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, Dysthymia).

The sample had a mean age of 42.7 years, 48.9% were women, and 85.5% had either a bachelor’s degree or postgraduate degree. Patient’s initiating KAP treatment were taking an average of 2.84 medications for psychiatric complaints at intake. These included antidepressants, stimulants, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, sedatives/anxiolytics, and other medications. On average, individuals fell in the moderate depression category as per BDI (mean = 26.55) and moderate anxiety category as per HAM-A scale (mean = 20.35) before treatment and had a significant ACE score (mean = 3.63). Average resilience score at baseline was 8.27. About one-third (35%) of our population had previous experience with psychoactive substances. These included MDMA (n = 34), LSD (n = 34), psilocybin (n = 29), ayahuasca (n = 6), and ketamine (n = 6). Usual number of years in psychotherapy for our KAP patients was 3–5 years. Total number of people who received IM ketamine was 61.5%. The average dose range of ketamine during KAP sessions was 200–250 mg for the SL route and 80–90 mg for the IM route in our sample.

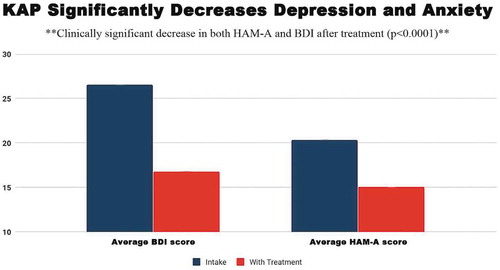

Outcomes included decreases in anxiety and depression. demonstrates clinically significant improvements in depression and anxiety as measured by BDI and HAM-A. Subset analysis of the improvement in depression and anxiety demonstrates that patients with developmental trauma (cPTSD) or developmental trauma have greatest improvement in depression and anxiety scores. Patient self-reported measures (HAM-A, BDI, change of state scores) correlated with clinician rater views on visit and termination forms (including depression, anxiety, PTSD, well-being), confirming internal consistency between clinician report and patient self-report. P values for all of these correlations were significant at p< 0.0001.

Figure 3. Average BDI and HAM-A scores at baseline compared with follow-up reveal a statistically significant decrease in anxiety and depression with treatment. Intake BDI scores on average fell in the range of moderate depression (20–28) and decreased an average of 11.24 points to mild depression range. Intake HAM-A scores fell in the moderate anxiety category and decreased on average 5.5 points to the mild anxiety category.

Number of in-office KAP sessions ranged from 1 to 25 sessions, which were spread over variable time periods from initial session to visit evaluation to termination where applicable. The number of ketamine sessions positively correlated with improvements in the Levine Rapid Depression Scale (p < 0.001), and improvements in BDI from pre- to post-treatment (p < 0.01), indicating that a higher number of visits was correlated with greater improvements in depression post-treatment. Treatment duration positively correlated with Depression Rater View (p < 0.05) and Anxiety Rater View (p < 0.05), showing that those with a longer total duration of treatment also showed greater improvements in depression and anxiety.

Patients with severe symptom burden (including higher BDI at intake, suicidality at intake and within past year, history of psychiatric hospitalization, and higher ACE scores) had more significant improvements with KAP treatment, as demonstrated by greater improvement in anxiety scores, well-being scores, BDI, PTSD scores, drug and alcohol use scores with treatment, p < .01 for all correlations. Additionally, increased age was correlated with greater improvement of depression as per rater view (p < .05), lower HAM-A with treatment (p < .01), and lower BDI with treatment p< .05.

Discussion

KAP is a unique, ground-breaking treatment with two essential modalities that have led to successful treatment outcomes in our clinical practices. We have presented these two modalities as “trance” and “transformation.” Ketamine has a dose-related continuum of psychoactivity that modifies therapeutic communication and interaction, and which provides a range of effects from one medicine decreasing symptoms and facilitating new ways of being for our patients. Our view is that the psychedelic, or dissociative, effects are an integral part of KAP, not to be feared or avoided, but instead that offer benefit to our patients when supported and integrated in a psychotherapeutic context. This benefit occurs not only across a range of doses but also for a range of diagnoses and human difficulties that present within the context of a general psychiatry private practice. KAP stands at the forefront of legal psychedelic psychotherapies as MDMA and psilocybin enter Phase 3 Studies. The practice of KAP has thus laid the groundwork for a growing body of practitioners who will adopt the principles of psychedelic psychotherapy as a part of the future of mental health treatment.

In this study, we present a portrait of KAP which combines patient experiences from three practices of different maturity. Importantly, we found significant benefits for many diagnoses. The population we present reflects the interest from the general population in ketamine work, often stemming from failed prior treatments. Our patients come to KAP with moderate levels of depression and anxiety, and a significant amount of adverse childhood events.

The side-effect profile is important to highlight, given that the most common reason for discontinuing conventional pharmacological treatment for depression and anxiety is the inability to tolerate side effects such as nausea or sexual dysfunction. Ketamine can be administered frequently when symptoms are acute (up to every 48 hours), or periodically in a maintenance format, depending on the needs of the patient. Episodic, intermittent use of a medication is, for many patients, preferable to constant exposure, as with daily antidepressants. Intermittent use of medication also decreases the potential for adverse effects. We also note that, despite the stigma of recreational use and concerns regarding addiction, ketamine used in KAP practice does not produce any physical dependence. Importantly, we have not had patients seek ketamine outside of our clinical practices or encountered any other indication of addictive behavior.

Despite the fact that much of our cohort was naive to psychoactive experiences (65% naive to psychoactives), patients were open to their future ketamine experiences having psychedelic aspects. Psychedelic experiences were well-tolerated and sought after as an essential component of their healing process. Our patient population, in their at-home administration, under close supervision, adjusted their dosage to a balance between trance depth and recollection of their experiences. This aspect of our work is unique in that it requires patients to be more engaged and creative in their own settings.

Our patients experienced a clinically significant decrease in anxiety and depression with treatment as compared to baseline at intake. We also found that patients who have more severe symptoms, including current suicidality, high BDI at intake, and higher ACE score, tend to show the most significant benefit. These correlations help us to begin to form hypotheses about which types of patients benefit most from KAP and will help guide treatment decisions and the integration of this modality into general psychiatric practice. Findings are limited by the instruments we have used to measure change. In our clinical experience, we have observed significant benefit even in the patients who appear to function relatively well and report less symptomatology. Future studies are needed to characterize these observations.

Ketamine is not for everyone. Some patients are sickened by ketamine and a subset (< 5%) cannot tolerate the nausea and vomiting experienced even with preventative medication. A small percentage (1–2%) do not respond to ketamine even at high IM doses. Others, particularly those with rigid personality structures, such as those with severe OCD or personality disorders and perhaps severe PTSD, find entering the trance state difficult and are not able to sustain the benefits they experience during the actual sessions, even if they do indeed experience some relief.

While we are unable to comment on neurobiological mechanisms of action, there is the suggestion that neuroplastic changes may be at work, as well as possible anti-inflammatory effects. Our finding that older patients have more significant improvement in depression over the course of their treatment tends to support this. We thought at first that increased benefit with age might reflect the amount of psychotherapy that a patient had upon entering KAP treatment; however, this variable was not significant.

KAP differentiates itself from the IV practices that have burgeoned in recent years. We have presented our office-based practices and our controlled prescriptions for at-home use. While we follow the protocol that includes frequent sessions in the first stage of ketamine’s application for depression and TRD (most commonly six sessions in two weeks, which may be repeated until remission is achieved), our work embeds ketamine administration within a psychotherapeutic framework for both in-office sessions and home use. As therapy proceeds, we move to a maintenance approach with less frequent ketamine sessions, or sessions that are conducted to prevent significant relapes. We provide treatment plans that include varied frequencies and doses of administration for other psychiatric diagnoses, adapting our KAP treatment to each patient’s individual needs through frequent contacts and close communication.

Comparison of outcomes and effects between the IV practices and KAP are difficult to obtain at this point. Our data set appears to be more complex than what is reported by the IV practices and we have the benefit of experience in diagnosing and treating psychiatric disorders and combining treatment modalities. We anticipate showing a more complete set of our emerging data in the next year as uniformity in reporting enables this. Presently, the use of ketamine with KAP versus the IV practices differentiate in methodology, as well as in economics. KAP, even with its intensity and long sessions, is significantly less expensive overall.

describes our approach for achieving both the Trance and Transformation experiences in individual patients, this method having been developed over the five years that KAP has been practiced. Thus, our positive findings in this article reflect an evolving methodology using ketamine with psychotherapy as described, as opposed to a specific protocol. We have now developed a step-by-step approach that is manualized and taught in our trainings (In trainings conducted by KRF). Further research is required to refine, validate, and test the components of this protocol, and to compare outcomes of the protocol with those of IV ketamine interventions and with standard of care interventions in mental health treatment. In addition, affordability and access to treatment are a major concern for both practitioners and potential patients.

Conclusion

Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy is a new and unique methodology with a rapidly growing group of practitioners participating in its development and practice. We have presented a view of its current status combining data from three different related centers, with attendant outcomes with correlations. Psychedelic experience is an inherent, valued, and well-tolerated part of our methodology. Our data support the efficacy of KAP for a wide variety of psychiatric diagnoses and human difficulties, significantly diminishing depression, anxiety, and PTSD and increasing well-being.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brown, D. A., and D. Elliott. 2016. Attachment disorder in adults. New York, NY: W.W.Norton.

- Carhart-Harris, R., L. Roseman, E. Haijen, D. Erritzoe, R. Watts, I. Branchi, and M. Kaelen. 2018, July. Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. Journal of Psychopharmacology 32 (7):725–31. Epub 2018 Feb 15. doi:10.1177/0269881118754710.

- Chilukuri, H., R. Pothula, R. Pathapati, A. Manu, S. Jollu, and A. Shaik. 2014. Acute antidepressant effects of intramuscular versus intravenous ketamine. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine (36/1):71–76. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.127258.

- Collins, K., J. Murrough, A. Perez, D. Reich, D. Charney, and S. Mathew. 2010. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry 67 (2):139–45. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038.

- Cusin, C., G. Hilton, A. Nierenberg, and M. Fava. 2012. Long-term maintenance with intramuscular ketamine for treatment-resistant bipolar II depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 169:868–69. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020219.

- Early, T. 2016. Making ketamine work in the long run. In The ketamine papers: Science,therapy and transformation, ed. P. Wolfson and G. Hartellius, 305–22. Santa Cruz, CA: MAPS Press.

- Feduccia, A., J. C. Holland, and M. C. Mithoefer. 2018. Progress and promise for the MDMA drug development program. Psychopharmacology 235 (2):561–71. doi:10.1007/s00213-017-4779-2.

- Fontana, A. 1974. Terapia atidepresiva con ketamine. Acta psiquiatrica y psicologica de America latina 20:32.

- Griffiths, R., M. Johnson, W. Richards, B. Richards, U. McCann, and R. Jesse. 2011. Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: Immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 218 (4):649–65. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2358-5.

- Hyde, S. J. 2015. Ketamine and depression. Tasmania: Xlibris.

- Jaitly, V. 2013. Sublingual ketamine in chronic pain: Service evaluation by examining more than 200 patient years of data. Journal of Observational Pain Medicine 1/2 (2013).

- Jansen, K. 2004. Ketamine: Dreams and realities. Santa Cruz, CA: MAPS.

- Khorramzadeh, E., and A. Lofty. 1973. The use of ketamine in psychiatry. Psychosomatics 14:344–46. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(73)71306-2.

- Kolp, E., M. S. Young, H. Friedman, E. Krupitsky, K. Jansen, and L. O’Connor. 2007. Ketamine-enhanced psychotherapy: Preliminary clinical observations on its effects in treating death anxiety. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 26:1–17. doi:10.24972/ijts.

- Krupitsky, E., and A. Grinenko. 1997. Ketamine psychedelic therapy (KPT)—A review of the results of ten years of research. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29 (2):165–83. doi:10.1080/02791072.1997.10400185.

- Krystal, J. H. 2007. Ketamine and the potential role for rapid-acting antidepressant medications. Swiss Medical Weekly 137 (15–16):215–16.

- Krystal, J. H., L. P. Karper, J. P. Seibyl, G. K. Freeman, R. Delaney, J. D. Bremner, and D. S. Charney. 1994. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans: Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Archives of General Psychiatry 51 (3):199–214. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004.

- Krystal, J. H., S. Madonick, E. Perry, R. Gueorguieva, L. Brush, Y. Wray, A. Belger, and D. C. D’Souza. 2006. Potentiation of low dose ketamine effects by naltrexone: Potential implications for the pharmacotherapy of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology 31 (8):1793–800. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300994.

- Lara, D., L. Bisol, and L. Munari. 2013. Antidepressant, mood stabilizing and procognitive effects of very low dose sublingual ketamine in refractory unipolar and bipolar depression. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 16 (9):2111–17. doi:10.1017/S1461145713000485.

- Luckenbaugh, D. A., M. J. Niciu, D. F. Ionescu, N. M. Nolan, E. M. Richards, N. E. Brutsche, and C. Zarate. 2014. Do the dissociative side effects of ketamine mediate antidepressant effects. Journal of Affective Disorders 159:56–61. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.017.

- Matthew, S., and C. Zarate, editors. 2016. Ketamine for Treatment Resistant Depression. Switzerl: Adis, Springer International.

- McGirr, A., M. Berlim, D. Bond, M. Fleck, L. Yatham, and R. W. Lam. 2014. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychological Medicine. doi:10.1017/S0033291714001603.

- Millière, R., R. Carhart-Harris, L. Roseman, F. Trautwein, and A. Berkovich-Ohana. 2018, September 4. Psychedelics, meditation, and self-consciousness. Frontiers in Psychology 9:1475. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01475.

- Mithoefer, M. C., C. S. Grob, and T. D. Brewerton. 2016. Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: Psilocybin and MDMA. The Lancet Psychiatry 3 (5):481–88. Epub 2016 Apr 5. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00576-3.

- Nour, M. M., L. Evans, D. Nutt, and R. L. Carhart-Harris. 2016, June 14. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: Validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 10:269. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269.eCollection2016.

- R. M.A. Cappiello, A. Anand, D. Oren, G. Heninger, D. Charney, and J. Krystal. 2000. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry 47 (4):351–54. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00230-9.

- Rot, M., K. Collins, J. Murrough, A. Perez, D. Reich, D. Charney, and S. Mathew. 2015. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry 67/2:139–45. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038.

- Ryan, W., C. Marta, and R. Koek. 2016. Ketamine and depression: A review. In The ketamine papers, ed. P. Wolfson and G. Hartellius, 199–273. Santa Cruz, CA: MAPS.

- Schwartz, R. 1995. Internal family systems therapy. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Sullivan, P. 2018. Using ketamine to treat addictions. Paper presented at the Kriya Conference, The Nueva School. Hillsborough, CA, November 4.

- Van Der Kolk, B. 2014. The body keeps the score. London, UK: The Penguin Group.

- Wallach, J. 2018. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ketamine (and Related Compounds). Paper Presented at the Kriya Conference, The Nueva School. Hillsborough, CA, November 2.

- Weber, F., H. Wulf, M. Gruber, and R. Biallas. 2004. S-ketamine and s-norketamine plasmaconcentrations after nasal and iv administration in anesthetized children. Paediatr†anaesth 14 (12):983–988.

- Wieber, J., R. Gugle, J. Hengstmann, and H. Dengler. 1975. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine in man. Anaesthesist 24 (6):260–63.

- Williams, N. R., B. D. Heifets, C. Blasey, K. Sudheimer, J. Pannu, H. Pankow, J. Hawkins, J. Birnbaum, D. M. Lyons, C. I. Rodriguez, and A. F. Schatzberg. 2018. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. The American Journal of Psychiatry 175 (12):1205–1215. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138.

- Wolfson, P., and G. Hartelius, editors. 2016. The ketamine papers. Santa Cruz, CA: MAPS.

- Yensen, R. 2016. Psychedelic experiential psychology: Pioneering clinical explorations with salvador roquet. In The ketamine papers, ed. P. Wolfson and G. Hartellius, 69–93. Santa Cruz, CA: MAPS.

- Zarate, C., R. Duman, G. Liu, S. Sartori, J. Quiroz, and H. Murck. 2013. New paradigms for treatment-resistant depression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1292 (1):21–31. doi:10.1111/nyas.12223.