Abstract

Objectives. To calculate the cost for patients with heart failure (HF) in a primary healthcare setting. Design. Retrospective study of all available patient data during a period of one year. Setting. Two healthcare centers in Linköping in the southeastern region of Sweden, covering a population of 19 400 inhabitants. Subjects. A total of 115 patients with a diagnosis of HF. Main outcome measures. The healthcare costs for patients with HF and the healthcare utilization concerning hospital days and visits to doctors and nurses in hospital care and primary healthcare. Results. The mean annual cost for a patient with HF was SEK 37 100. There were no significant differences in cost between gender, age, New York Heart Association functional class, and cardiac function. The distribution of cost was 47% for hospital care, 22% for primary healthcare, 18% for medication, 5% for nursing home, and 6% for examinations. Conclusion. Hospital care accounts for the largest cost but the cost in primary healthcare is larger than previously shown. The total annual cost for patients with HF in Sweden is in the range of SEK 5.0–6.7 billion according to this calculation, which is higher than previously known.

Heart failure (HF) is a common and costly condition with great impact on national health economy. The estimated prevalence is 1.5–2%, which means there are approximately 135 000–180 000 patients in Sweden suffering from HF Citation[1–3]. The direct cost for patients with HF is estimated to account for about 2% of the total National Health Service budget in Sweden as well in the United Kingdom Citation[4], Citation[5]. The prevalence of the disease is increasing continuously and consequently rising costs in the future might be expected due to an aging population and to the increased rate of survival for patients with acute myocardial infarction Citation[6]. However, reduced mortality due to coronary heart disease has been shown, probably in the future affecting the number of heart failure patients Citation[7].

When patients are optimally treated according to guidelines benefit will be obtained in terms of less hospitalization and decreased healthcare costs Citation[8]. Treatment with beta-receptor blockers, as well as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors has been shown to be cost effective Citation[9], Citation[10]. There are still many patients not receiving optimal treatment and only about 30–60% of the patients with HF have performed an echocardiographic investigation according to guidelines Citation[3], Citation[11–13]. Many patients with a clinical diagnosis of HF do not have abnormal cardiac function but still are managed as patients suffering from HF. Those patients do not fulfil the accepted diagnostic criteria for HF and should not be treated as such.

Most previous studies have been focused on hospital-based patients with HF usually recruited in hospital environments. About 70% of the costs in those studies are caused by hospitalization and 11–18% by drug treatment and the care given by primary healthcare accounts only for 6% Citation[4], Citation[5]. Studies including hospital-based patients show a high consumption of hospital care and a high readmittance rate.

Many patients with HF in Sweden are managed and treated by a general practitioner in primary healthcare. Consequently, there are increasing demands on the general practitioner treating patients with HF even though health economic studies performed give the impression that primary care management and subsequent costs constitute a smaller part. It is estimated that general practitioners control more than 50% of the patients with HF and still there are no studies estimating the cost and the distribution of the cost in HF patients in primary healthcare. The aim of this study was to further investigate the direct cost for patients with HF in primary healthcare, a perspective not previously presented.

Material and methods

Study design

Patients with HF were included in the present study from two healthcare centers in Linköping, Sweden, covering a population of 19 400 inhabitants. The population is considered to be representative concerning age and social standard for patients in primary healthcare in Sweden. From the computerized records in the primary healthcare centers, all patients with the diagnosis of HF, I 50, according to the ICD-10 classification were collected during the years 1999 to 2000 and 294 patients were found with a diagnosis of HF. The vast majority of problems coded in accordance with ICD-10 have high accuracy in Swedish general practice, indicating high reliability Citation[14]. Patients with a diagnosis of dementia, malignancy, suspected malignancy, or those receiving palliative care were excluded and the remaining 174 were offered the opportunity to participate. Of these, 115 consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of HF were included. Fifty-nine patients declined to participate mainly due to high age.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class was determined for all patients included and all had an echocardiographic examination performed to assess their cardiac function.

Cost calculation

To estimate the cost during one year for HF patients in primary healthcare all available patient data from the 115 included patients were collected. Patient records from the primary healthcare center and the nearby hospital were carefully scrutinized. The number of visits the patient had made to doctors, nurses, chiropodists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists was registered. The visits to nurses are divided into regular nurse, asthma nurse, diabetic nurse, and hypertension nurse. These nurses are specialized in managing concomitant diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, diabetes, and hypertension. From the hospital records of each patient the number of days the patient was treated at departments of cardiology, internal medicine, and surgery was obtained. Ongoing medication, dosages, and number of days on treatment were registered according to hospital and primary healthcare records. Investigations such as X-ray, coronary angiography, echocardiography, and exercise tests were also registered.

The price list retrieved from the Ödeshög study has been used in order to calculate the patient costs in primary healthcare Citation[15]. The costs of hospital care were calculated according to the price list used in hospital administration. The cost for investigations such as X-ray and echocardiography were calculated with the price list used in the hospital. The cost of medication was based on the Swedish National Medical Agency price list. The different costs used are shown in . The cost for each patient was calculated and an average cost and a median cost was obtained for the whole group and also divided into cost in primary healthcare, hospital care, medication, and investigations. In order to clarify the specific costs for the diagnosis of HF, the medication was divided into treatment for cardiovascular diseases (beta-blockers, calcium inhibitors, ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin II inhibitors, digoxin, diuretics, and statins), diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases.

Table I. Cost per different unit of healthcare resources.

Statistics

Statistical methods used were Student's t-test for comparison of mean values and the chi-squared test for comparison of distributions. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. A simple regression analysis was performed to analyze whether the factors gender, age, NYHA class, cardiovascular diseases, or cardiac function were correlated to the total cost. The Ethical Committee at the University Hospital of Linköping has approved the study.

Results

Of the 115 patients, 52 (45%) were women and 63 (55%) men and the mean age was 77± 8 years. The cost of the whole group of patients during one year was on average SEK 37 100 per patient (median SEK 23 283). The mean cost for women with HF was SEK 38 600 (median SEK 26 024) while the cost for men was SEK 36 600 (median SEK 18 636). This difference was not significant.

Thirty-three of the patients had a normal cardiac function, assessed by echocardiography, and the remaining 82 patients had abnormal cardiac function (systolic and/or diastolic dysfunction). Basic characteristics are given in . There was no significant difference in cost between these two groups, normal or abnormal cardiac function.

Table II. Basic characteristics of the patient group with normal and abnormal cardiac function.

The mean number of visits that the patient had to a GP, nurse in primary healthcare, hospital doctor (outpatient care), and specialized nurses at the hospital (outpatient care) and also the average number of hospital days (inpatient care) and the consequent cost are illustrated in . The distribution of cost was 47% for hospital care, 22% for primary healthcare, 18% for medication, 5% for nursing home, and 6% for examinations.

Table III. Patient-related costs for hospitalization, visits, medication and investigations divided into gender and in total.

Discussion

The average annual cost for each individual patient with a confirmed diagnosis of HF was in this study SEK 37 100. Other studies suggest a similar cost but there are some differences, probably due to study design and selection of patients. A study with prices from 1996 has given a calculated cost of SEK 25 000 (giving an annual cost of SEK 4.5 billion) Citation[5]. This cost is based on official statistics and the costs accounting for primary healthcare are not easily identified. Another study estimated the cost for patients with HF and ischemic heart disease one year before and after hospitalization Citation[16]. In this study the mean cost for patients with HF (25 patients) was calculated to be SEK 40 791 one year after hospitalization, similar to our study, although the mean age was considerably lower, 58 versus 77 years old. The costs for ischemic heart disease were similar to those for HF. This might be expected since ischemic heart disease is the dominating etiology in HF Citation[3], Citation[13].

Another study with a study period of only 6 months was found to have a mean cost of SEK 34 165 Citation[17]. The cost was calculated 6 months after discharge from hospital, which is known to be the time period when there is a high risk of readmission as is also shown in this study, which had a readmission rate of 42%. The cost will consequently be much higher since the highest cost is generated when patients are hospitalized. The calculated cost in this study will apply poorly to patients with HF in primary healthcare. It is also noted that the patients in this study during the study period had a mean number of hospital days of 4.8, visits to cardiologist of 1.5, and visits to nurses of 3.1. This is a much higher rate of use of hospital resources compared with our study where the number of hospital days during a study period of 12 months was on average 4.3 days, visits to hospital doctor 0.7, and visits to nurses 0.2. These patients were included after hospitalization for HF, so it can be assumed they had more severe HF and therefore demand more frequent use of hospital resources.

In comparison with another chronic disease such as diabetes type II, which is mainly managed in primary healthcare, diabetes has an average cost of SEK 25 000 Citation[18]. This is a lower cost and might partly be explained by the fact that patients with HF are more frequently admitted to hospital compared with diabetic patients and therefore generate a higher cost. An investigation with focus on patients with diabetes, performed in the population in Ödeshög community located 50 km west of Linköping, found that few patients required a lot of primary healthcare resources Citation[15]. A major part of the cost was due to the work performed by district nurses. This is similar to the findings in our study where district nurses accounted for a high number of visits and costs.

This study included primary healthcare-based patients and primary healthcare data were easily available and is probably a reason why the primary healthcare cost in this study is higher (22% of the cost) compared with the cost given in other publications (6%), which included hospital-based patients Citation[4], Citation[5]. Perhaps patients in primary healthcare have more stable HF with less need of hospital care (in our study related to 47% of the cost versus about 70% in other studies) although the echocardiographic findings and NYHA class are comparable with other studies. It is apparent that primary healthcare-based patients with HF use primary healthcare resources more than previously described despite the assumption that they have a relatively stable condition. The cost representing primary healthcare is not entirely related to HF but is probably due to a high rate of comorbidity in these patients with HF. This indicates that the care given in primary healthcare is not completely equivalent and replaceable by the care given in hospital.

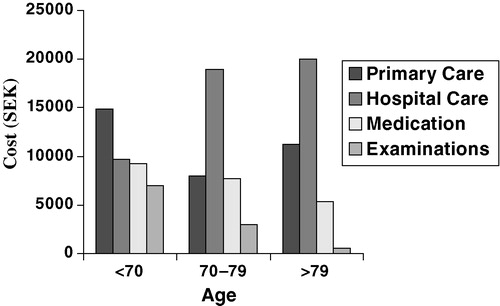

There were no significant differences in cost concerning echocardiographic-assessed cardiac function, concomitant diseases, NYHA class, age, or gender and none of these factors had an impact on the cost. These findings may be the result of too small a sample but could also be explained by these patients’ overall healthcare utilization, due to comorbidity or individual need. The cost for investigations was low in our study, probably due to the fact that patients had had their diagnostic investigations performed prior to the study. Cardiovascular treatment cost was related in our study to 18% of the total cost and was lower as the patient grew older (). On the other hand, the cost for hospital care was increasing with age (SEK 10 000–SEK 20 000). The costs for managing patients with HF can probably be markedly reduced, by prevention of hospitalizations due to HF, if the diagnosis of HF is correct and optimal treatment is used according to guidelines.

Conclusion

Most studies trying to calculate the cost for managing HF patients have included hospital-based patients with a lower mean age than HF patients in the society. The estimated annual cost for HF has been estimated at less than SEK 3 billion. During the last few years, studies have estimated the cost as in the range of SEK 4.5–7.4 billion. In the present study, we have included HF patients in primary healthcare and the estimated cost in Sweden would be SEK 5.0–6.7 billion if these are representative data. The true cost for patients with HF in Sweden is more likely to be in the range of SEK 5–6 billion than SEK 3 billion. Using appropriate diagnostic instruments and optimal treatment might markedly reduce the cost but to prove this controlled studies are needed.

Key Points

The cost for patients with heart failure (HF) in a primary healthcare population has not previously been investigated.

The cost for a patient with heart failure was SEK 37 100, which gives a total cost for HF in Sweden in the range of SEK 5.0–6.7 billion, much higher than previously known.

There were no significant differences in cost concerning gender, NYHA class, age, or heart function assessed by echocardiography.

Primary healthcare accounts for a greater part of the total costs than previously assumed.

This study was supported by a grant from the Medical Research Council of Southeastern Sweden.

References

- McDonagh TA, Morrison CE, Lawrence A, Ford I, Tunstall-Pedoe H, McMurray JJV, Dargie HJ. Symptomatic and asymptomatic left-ventricular systolic dysfunction in an urban population. Lancet 1997; 350: 829–33

- Alehagen U, Eriksson H, Nylander E, Dahlström U. Heart Failure in the elderly: Characteristics of a Swedish primary health care population. Heart Drug 2002; 2: 211–20

- Agvall B, Dahlström U. Patients in primary health care diagnosed and treated as heart failure, with special reference to gender differences. Scand J Prim Health Care 2001; 19: 14–19

- Stewart S, Jenkins A, Buchan S, McGuire A, Capewell S, McMurray J. The current cost of heart failure to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur J Heart Fail 2002; 4: 361–71

- Rydén-Bergsten T, Andersson F. The healthcare costs of heart failure in Sweden. J Intern Med 1999; 246: 275–84

- Mejhert M, Persson H, Edner M, Kahan T. Epidemiology of heart failure in Sweden: A national survey. Eur J Heart Fail 2001; 3: 97–103

- Hartikainen S, Ahto M, Löppönen M, Puolijoki H, Laippala P, Ojanlatva A, et al. Change in the prevalence of coronary heart disease among Finnish elderly men and women in the 1990s. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 178–81

- Cline CM, Israelsson BY, Willenheimer RB, Broms K, Erhardt LR. Cost effective management programme for heart failure reduces hospitalisation. Heart 1998; 80: 428–9

- Ekman M, Zethraeus N, Jonsson B. Cost effectiveness of bisoprolol in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure in Sweden: Analysis using data from the cardiac insufficiency bisoprolol study II. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19: 901–16

- Erhardt L, Ball S, Andersson F, Bergentoft P, Martinez C. Cost effectiveness in the treatment of heart failure with ramipril: A Swedish substudy of the AIRE study. Pharmacoeconomics 1997; 12: 256–66

- Mair F, Crowley T, Blindred PE. Prevalence, aetiology, and management of heart failure in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1996; 46: 77–9

- Parameshwar J, Shackell M, Richardson A, et al. Prevalence of heart failure in three general practices in North West London. Br J Gen Pract 1992; 42: 287–9

- Nilsson G, Strender L-E. Management of heart failure in primary health care: A retrospective study on electronic patient records in a registered population. Scand J Prim Health Care 2002; 20: 161–5

- Nilsson G, Åhlfeldt H, Strender L-E. Textual content, health problems and diagnostic codes in electronic patient records in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 33–6

- Östgren CJ, Johansson A, Grip B, Johansson A, Heurgren M, Melander A. Diabetessjukvård resurSEKävande i primärvården. Läkartidningen 2003; 100: 3600–4

- Zethraeus N, Molin T, Henriksson P, Jönsson B. Costs of coronary heart disease and stroke: The case of Sweden. J Intern Med 1999; 246: 151–9

- Björck Linné A, Liedholm H, Jendteg S, Israelsson B. Health care costs of heart failure: Results from a randomised study of patient education. Eur J Heart Fail 2000; 2: 291–7

- Henriksson F, Agardh C-D, Berne C, Bolinder J, Lönnqvist F, Stenström P, Östenson C-G, Jönsson B. Direct medical costs for patients with type 2 diabetes in Sweden. J Intern Med 2000; 248: 387–96