Abstract

Objective: The aim of the current study was to better understand how patients with depression perceive the use of MADRS-S in primary care consultations with GPs.

Design: Qualitative study. Focus group discussion and analysis through Systematic Text Condensation.

Setting: Primary Health Care, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden.

Subjects: Nine patients with mild/moderate depression who participated in a RCT evaluating the effects of regular use of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Self-assessment scale (MADRS-S) during the GP consultations.

Main Outcome measure: Patients’ experiences and perceptions of the use of MADRS-S in primary care.

Results: Three categories emerged from the analysis: (I) confirmation; MADRS-S shows that I have depression and how serious it is, (II) centeredness; the most important thing is for the GP to listen to and take me seriously and (III) clarification; MADRS-S helps me understand why I need treatment for depression.

Conclusion: Use of MADRS-S was perceived as a confirmation for the patients that they had depression and how serious it was. MADRS-S showed the patients something black on white that describes and confirms the diagnosis. The informants emphasized the importance of patient-centeredness; of being listened to and to be taken seriously during the consultation. Use of self-assessment scales such as MADRS-S could find its place, but needs to adjust to the multifaceted environment that primary care provides.

Patients with depression in primary care perceive that the use of a self-assessment scale in the consultation purposefully can contribute in several ways. The scale contributes to

Confirmation: MADRS-S shows that I have depression and how serious it is.

Centeredness: The most important thing is for the GP to listen to and take me seriously.

Clarification: MADRS-S helps me understand why I need treatment for depression.

Key Points

Introduction

In Sweden, as in most other countries, the majority of people with depression are diagnosed and treated in primary care. Scales that rate the severity of depression are becoming increasingly common in primary care; approximately a third of Swedish GPs use them in their practice.[Citation1] These scales are used to assess the severity of the disease and to follow the effects of treatment. Many such scales exist, but the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (self-rating version) (MADRS-S) is the most commonly used in Sweden.[Citation2] Studies indicate that routine assessments of patients’ depressive symptoms in clinical practice are beneficial;[Citation1] they can help GPs evaluate the progress of depression,[Citation3] and can facilitate cooperation and communication between the GP and the patient Communication is of great importance during the consultation and this benefits patients in many ways, including increasing satisfaction with care and improving patients’ understanding of and knowledge about their condition.[Citation4,Citation5] However, according to a systematic review on “Diagnosis and follow up of affective disorders”,[Citation1] there are no studies of acceptable quality that compare rating scales to assess severity of depression against an adequate reference standard, why the review asserts that there is no evidence to support their use to monitor depression severity during treatment.[Citation1]

According to a previous study,[Citation6] GPs’ perception is that a self-assessment scale does not add anything to consultations and that it is more of a hindrance than a help to diagnosis and the consultation as a whole. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the patients' view of MADRS-S in primary care consultations. We hypothesized that patients’ perceptions would be in line with GPs’, and if so, the role of depression rating scales in primary care should be reconsidered.

The aim of the current study was to better understand how patients with depression perceive the use of MADRS-S in primary care consultations with GPs.

Materials and methods

We used focus groups to collect data to be able to take the advantage of the communicative interaction between participants sharing their experiences. This method is suitable for obtaining new information about issues that are not extensively researched.[Citation7] The focus group method enables participants to discuss beliefs, attitudes, and experiences. The interactive format encourages participants to share their opinions and attitudes on the given subject.

C.B. is a general practitioner, C.W. and J.W. are specialist nurses, and E.L.P. is an occupational therapist; all have worked in primary care with patients who have depression. A.P. is a systematic reviewer at SBU. All the authors work with primary health care development and research.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the intervention arm of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [Citation8] of treatment in patients with depression. The trial evaluated the effects of the regular use of a self-assessment scale (MADRS-S) plus four extra visits to the same GP on a variety of outcomes, such as depressive symptoms and return to work. MADRS-S was used to evaluate symptoms and changes in symptoms over time and to adjust treatment. Participants were to fill out MADRS-S during each consultation, and the GPs were to discuss the results with the patient. All GPs who participated in the intervention study were taught about MADRS-S and how to use it in the consultation. Trial recruitment was ongoing; the study ran from 2010–2012.

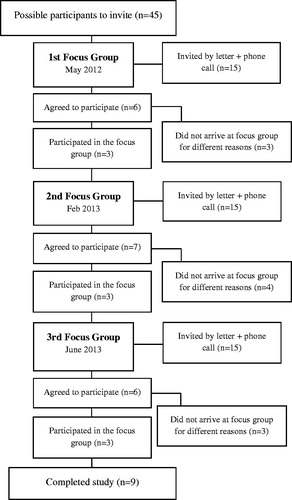

Twelve weeks after they completed the intervention, patients were invited to a focus group discussion. Sending of the invitation was timed to avoid memory bias. We planned to hold three focus group discussions with four to eight participants per group and invited the participants in three rounds; ∼15 people were invited on each occasion (). Each invitation was followed up with a phone call.

All patients who agreed to participate received a letter with instructions about the focus group. The letter included guidelines on how the group would be run and a list of topics to think about before the focus group (Appendix I).

Data collection

The focus groups were conducted between May 2012 and June 2013 and lasted for about ∼1–1.5 h each. The focus groups took place at the Department of Research & Development in Primary Care in Gothenburg. E.L.P., A.P. and C.W. participated in the focus groups. At each meeting, one functioned as moderator and another as observer; the authors shifted roles for each focus group. The observer wrote field notes to complement the audio recording and summarized the researchers’ reflections after the meetings. Prior to the first focus group, the researchers developed a topic guide that included questions focused on eliciting the patient’s perspective of the experience of completing the self- assessment scale and how this experience affected the patient’s treatment and his or her relationship with the GP. All participants were informed orally and in writing about the study. This information included an explanation of their rights, including the information that they had the option to leave the study at any time. The participants were offered compensation for their participation (two movie tickets; value of ∼20 Euros). The focus groups were held after work hours, so the participants were also given a small meal. The recorded focus groups were transcribed verbatim by an external transcriber, and C.W. and E.L.P. crosschecked the transcripts with the recordings to verify their correctness.

MADRS-S

MADRS-S is the patient-administered version of MADRS.[Citation9] MADRS-S includes nine items that the patient rates on a scale from 0 to 6: reported sadness, inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, concentration difficulties, lassitude, inability to feel, pessimistic thoughts, and suicidal thoughts. Higher scores indicate more severe depression and the maximum score is 54. MADRS-S is especially sensitive to change and is therefore suitable for measuring the effect of treatment. Before the patient fills out the scale, the health professional should explain the purpose of MADRS-S and how to fill it out. After the patient has completed MADRS-S, the professional should discuss the results with the patient.

A study from France has shown that MADRS-S is a reliable and valid scale for measuring change in depression and is therefore appropriate for use in clinical trials.[Citation3] Another study concluded that patients accepted MADRS-S as a complement to the physician-administered version of the scale and that MADRS-S was clinically valuable and valid for use in clinical practice and research.[Citation10] Satisfactory correspondence between MADRS-S and Beck Depression Inventory II has also been demonstrated.[Citation11]

Data analysis

To analyse the text, we used Malterud’s Systematic Text Condensation (STC) inspired by Giorgi.[Citation12,Citation13] STC is an elaboration of Giorgie’s psychological phenomenological analysis and has a pragmatic approach that can be used for descriptive and explorative cross-case analysis. We choose this method since it offers a liable methodological quality in the process of intersubjectivity, reflexivity and feasibility for the novice researcher. Systematic text condensation is suitable for summarizing data gathered from multiple informants and even discussions with only a few participants can yield informative results.[Citation12] In the first step of systematic text condensation, C.W. and E.-L.P. read through the material to become familiar with it and form an overall impression of the content. In the second step, meaning units were identified and labelled with a code. The coded meaning units were organised into a matrix that showed the relationship between the units. In a third step, the meaning units were sorted under sub-codes (overarching codes). The meaning units were condensed into “artificial quotations”. In the fourth and final step, data were reconceptualised. The contents of each coded group were condensed and summarized into descriptions concerning discussion of using MADRS-S during the GP consultation. E.-L.P., A.P., J.W. and C.B. followed and validated the entire process

Table 1. Sample distribution in the MADRS-S patient focus group study.

Results

Patient characteristics

The sample of this study was purposive with the aim to look at individuals with depression who regularly completed the self-assessment scale (MADRS-S) together with the GP consultation. Out of 15 invited, six individuals agreed to participate in the first focus group and 11 declined. Three of the six came to the discussion. An early reading of the data collected during the first focus group showed that despite the low number of participants, the data were detailed and adequate, so we included the first focus group in the study. A total of nine participants completed the discussions. See for sample distribution.

Patients views

Three categories emerged from the analysis: (i) confirmation; MADRS-S shows that I have depression and how serious it is, (ii) centeredness; the most important thing is for the GP to listen to and take me seriously and (iii) clarification; MADRS-S helps me understand why I need treatment for depression.

Confirmation: MADRS-S shows that I have depression and how serious it is

Participants expressed the idea that the results of the rating scale were subjective and unique to their situation. Completing MADRS-S gave them a clearer picture of the symptoms (components) that made up their depression and how these components fit together. Some stated that completing MADRS-S provided an opportunity for the GP to step them through the symptoms of their depression so that they understood how these parts came together to form the whole.

FG3 l2: “I think it was pretty good, actually, to divide it up, because it organizes how you really feel. You got to go forward from point to point. How is it with that part, that part, that part, because it could be different for each. It was a good base, actually.”

Additionally, some said that filling out MADRS-S on multiple occasions clarified the severity of their condition; that it “took the temperature” of the depression. One participant said,

FG1 K: “I consider it to be a tool, both for the GP and to take the temperature.”

Some participants felt that MADRS-S made it easier for them to follow the progress of their treatment and get confirmation that their treatment was working.

Participants also expressed reservations about MADRS-S. They addressed the importance of being truthful to oneself when filling out MADRS-S so that the results could be as useful as possible in treatment. Some perceived the response alternatives were limited, so the scale did not give as nuanced a picture of their depression as it could have, and some wanted to choose a response that lay between two options. Additionally, they emphasized that it was important to have enough time to fill out the scale, as difficult questions required deeper consideration. Some thought that MADRS-S should not be used in early stages of depression because the answers might be blurred by the symptoms of the depression. The participants may be too ill to actually fill out the instrument at all or that the result would be flawed.

Centeredness: the most important thing is for the GP to listen to and take me seriously

MADRS-S could form a good basis for patient - GP discussion, facilitating the communication between the two. Patients perceived that it was important for GPs to take them seriously during the consultation.

FG3 l2: “How important it is when one comes and does not feel good, to be listened to, by a professional that takes the time to listen and understand in some way. I think that that alone can be very helpful for some people.”

This factor was considered a key component of the consultation. If the participant thought the GP took him or her seriously, it could enhance the consultation. The patients believed that GPs who had an understanding attitude and spent time talking about the depression showed they took the patient seriously. The very use of an instrument showed that the GP had listened: handing out MADRS-S confirmed that the GP wanted to know more about how the participant would rate and describe his or her depression.

FG2 l1: “It is important for a GP to understand the patients and take care of them in the right way to get the patient to understand, and this I feel he has succeeded with.”

Patients reported that the amount of time set aside for the consultation with the GP affected their opportunity to develop a positive communication.

FG3 l2: “But what I remember and appreciate a great deal is that the doctor took me seriously when I came here and was very down, very tired, very sad and had no motivation, so it was that which I got a lot of help from, it was that he was there and took me seriously and listened to me, and this was very very good.”

Other factors could be experienced as positive or negative depending on the participant’s point of view.

Some participants described how their GP turned toward the computer screen while the participant completed the scale, and some said that the GP did other work-related tasks while the participant was filling out the scale. Participants emphasized that this behaviour made them feel like the GP was only interested in the total MADRS-S “score”. On the other hand, for some participants, it was a relief that the GP did something else while the participant responded to MADRS-S. These participants did not want to be watched while they filled in the scale.

Clarification: MADRS-S helps me understand why I need treatment for depression

Participants experienced that GPs should use MADRS-S to explain why they need treatment for depression and why the GP recommended a specific kind of treatment

FG3 l2: “I think it could be a very useful tool for physicians and even patients. Getting to fill in if you feel that you have some form of depression or anxiety, or if life is tough. You can of course certainly end up with more accurate treatment by filling in this kind of questionnaire.”

After patients completed the instrument, most GPs reviewed the results with the patient, systematically comparing them with earlier results. Some participants perceived that the GPs should ask the participant to fill out the instrument only after the consultation with the patient. Some participants were given the opportunity to fill out the instrument at home before the consultation, and these participants considered this positive because at home, they had the time to give an honest and fair answer. By using the MADRS-S, the GPs reached the essence of the patient and his or her condition in a more rapid manner. This gave the patient and GP more time for the consultation. Many participants lacked sufficient instructions on how to complete the instrument. If the GP taught the patients a bit more about depression with the help of MADRS-S the suggested treatment could make more sense.

FG1 K: “He said that it would help both him and I to be able to, like, almost…take the temperature of how…how great or small the depression was. And one can have it like a tool that can help both him and me as a patient, to be able to…to be able to evaluate it quite easily.”

The participants had some doubt regarding to whom the MADRS-S was completed for, was it for the GP or for some other instance? Some GPs were more interested in the “full score” than in going through the answers individually, this had been more adequate according to the participants.

FG2 l1: “On my behalf it was more that she counted the scores and checked the results. Then there was no discussion of any questions, just to get the score itself.”

Sometimes the participants perceived MADRS-S as a shortcut to treatment and said they felt like the whole process was forced, they felt like the GP was eager to get the score and put it in a binder. The participants experienced that the MADRS-S "score" should not be used as the only basis for treatment, but as something that could strengthen and give weight to the treatment decision.

FG1 Å: “If this could help the doctor to, like, decide which type of treatment would be best for the patient then it is good. It is very good because sometimes one does not know. How could the patient be able to know?”

Discussion

This study investigated how patients with depression perceived the use of MADRS-S in primary care consultations with GPs. The results showed a diversity of perceptions from the participants. MADRS-S was perceived as an instrument that showed them, in black and white, that they really had depression, how serious the depression was, and changes in symptoms over time. Participants said that the most important aspect of the consultation was for the GP to listen to them and take them seriously and that having the chance to fill out MADRS-S during the consultation was one way to know the GP had taken them seriously. They also thought MADRS-S could help the GP decide which treatment was most appropriate. Additionally, participants felt that the information they got from filling out MADRS-S and discussing their answers with the GP made it easier to understand why the GPs recommended certain treatments. If the GP taught the patients a bit more about depression with the help of MADRS-S, the suggested treatment could make more sense.

Many participants found the instrument difficult to complete, and the participants sometimes felt that the physician neglected them while they completed the scale.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to shed light upon how patients with depression perceive the use of MADRS-S in primary care consultations with GPs. We invited patients from a well-functioning RCT study in the region, where all participants had undergone the same intervention. We aimed for five to six participants per discussion but ended up with three per occasion, for a total of nine participants in our study. In theory there are recommendations on five to eight in each focus-group discussion,[Citation14] but in reality there is not any set number as to how large a focus-group discussion should be. The important matter is that the data is sufficient enough to answer the research question.[Citation12] In our focus groups, the participants were talkative and dynamic. After three focus groups, we decided that we had collected sufficient data despite small group sizes. Since all patients included in the RCT who received the intervention was invited to this study a possible selection bias lies in the drop-outs. Those who declined to participate may therefore be different from those who attended the focus group session. However, the reasons for not attending the focus group were mostly lack of time due to family reasons. Saturation is in some qualitative methods a way to secure that analysis come from empirical data. According to Malterud [Citation12] the richness of the data grounded in empirical data is more important than the numbers of participants. In qualitative analysis it is of great value to determine an adequate and information-rich sample that provides coherent narratives of empiricism.[Citation12] Regardless of the small group of participants, representing one of the disadvantages with the focus group method; the self-selection of the participants, where the generalizability of the results can be called in question, we perceive that the rich data has opened doors to new insights and new understandings of patients using MADRS-S together with the GP consultation.[Citation7] The authors are researchers and health professionals and it might have persuaded the participants to answer in a desirable way. However, we feel that we did not force the participants or discussions in any direction.

The ratio of women to men matched the distribution of depression prevalence in the Swedish population, which is approximately 70%:30% [Citation1,Citation15,Citation16] and the age distribution was fairly spread. The discussion premises were perceived as safe and secure by the participants. This contributed to interaction and rich data content.

Discussion of findings

Almost all participants in our focus group discussions shared the same view that MADRS-S was helping them to reveal and picture their depression black on white. In contrast to a previous study on GPs perceptions,[Citation6] patients perceived that the self-assessment scale added something to the consultation and functioned as a tool for the patient and GP. MADRS-S was used both as a tool to visualize and to confirm the depression and as a facilitator for treatment. The participants were somewhat ambiguous on when, where and how the self-assessment scale should best come to use but they were unanimously positive that the GP should use them during the consultation. MADRS-S, which is especially sensitive to change, can be used to follow changes in the patient’s depression, and repeated measurements are required.[Citation9] For many informants a self-assessment scale confirmed their suspicions that they were depressed. All methods that enhance patients’ understanding of their diagnosis and what treatment they are receiving are based upon good communication. Patients are shown to be more adherent to treatment if they know more about their condition and have a GP with a patient-centred consultation method.[Citation17] The patients’ experience of MADRS-S was thus the opposite of the GPs’ experience;[Citation6] i.e. the patients perceived that the self-assessment scale added something to the consultation. They perceived that the self-assessment could function as a supplement to the physician in the consultation. Groot has shown that with the use of self-assessment, patients can benefit from its repeated use to help them learn and understand their depression.[Citation18]

The participants emphasized the importance of integrating the use of the instrument into the consultation rather than using it as an isolated questionnaire that was filed away in a folder.

The participants highlighted the importance of being listened to and taken seriously. A recent qualitative study from Great Britain emphasizes the importance of a good relationship with the GP [Citation19] which our results also seem to show. MADRS-S can enhance the involvement of patients in treatment decisions, via acknowledgement and being listened to. This goes in alignment with other studies that also confirm the importance of communication between patients and GPs in primary health care.[Citation20] Kadam [Citation21] concluded that patients describe it as helpful to talk to someone when being depressed, but that the GPs were too busy and saw it as of little value of importance.

The length of the consultation was not of great importance to the patients if the GP really listened. And a self-assessment scale showed that the GP had listened and was ready to take their concerns seriously. Although GPs do not share the patients’ positive view of the use of depression rating scales,[Citation6] this study shows an important aspect of using MADRS-S during consultation.

If the GPs are critical to the use of assessment instruments in patients with depression or cannot find the time to go through the answers together with the patient, perhaps other professionals in primary care could use them as part of a collaborate care model.[Citation22] Oxman has showed that there is a need to develop collaborative methods to cope with depression patients in primary care, facilitate options for treatment, and enhance GP/patient communication.[Citation23] On the other hand, Dowrick [Citation24] has shown that implementing case-finding and severity-grading instruments seems to compromise the relationship between the GP and patient and disturb the consultation process. MADRS-S could be a pedagogical tool that helps GPs better understand each patient’s experience of symptoms and thus creates a bridge of understanding between the patient and the GP. In the present study, some participants perceived that the GPs should use the scale to explain the level of depression the participant was experiencing and why they recommended certain treatment options. Some experienced the GP more interested in the “score” rather than using the assessment scale as a tool for improving communication during the consultation.

Another aspect of the use of depression rating scales to take into consideration is that continuity of care enhances the patients’ satisfaction.[Citation25] Using MADRS-S repeatedly as a part of collaborative care may benefit compliance to treatment.[Citation26] A deeper understanding among physicians of the patients’ experiences of depression may also lead to improved treatment. To improve the treatment of depression, more research is needed to pinpoint successful methods and find the determinants that increase adherence to treatment and provides a long-term and sustainable outcome.[Citation27]

GPs have been found to perceive that the depression rating scales hamper the dialogue in the consultation, although they can be useful with specific groups of patients.[Citation6] It was clear from the discussions that the GPs had given participants differing instructions on how to complete MADRS-S, and that this could have impeded or altered the degree of discussions. The more educated the patients are in terms of the purpose and how to fill out the instruments the more likely an accurate result is obtained. On the other hand, if the patients better understand their depression and the GP can use that knowledge to enhance compliance to treatment, MADRS-S could strengthen the patient-doctor communication.

Use of self-assessment scales such as MADRS-S could find its place, but needs to adjust to the multifaceted environment that primary care provides. There is need for more information and education on how to practically use the instruments, both for GP’s and patients.

Implications

The use of self-assessment instruments during consultations in primary care is still called in question. However in this study MADRS-S showed that there are several beneficial aspects from the patients’ point of view, which could contribute to increase in patients’ knowledge, adherence, and the patient-doctor communication. To achieve best conditions for this, GPs need to inform and educate the patient about use of the self-assessment instruments.

Conclusion

We assumed that patients’ perceptions would be in line with GPs’, and if so, the role of depression rating scales in primary care should be reconsidered. The results were not aligned with our assumptions and showed us that the use of MADRS-S was perceived as a confirmation for the patients that they had depression and how serious it was. MADRS-S showed the patients something black on white that describes and confirms the diagnosis. The informants emphasized the importance of patient-centeredness; of being listened to and to be taken seriously during the consultation. Further, the instrument helped to clarify for the patient the need of treatment for depression. The differences in how patients and GP’s perceive the use of self-assessment scales are to be taken seriously. To get the most benefit from the method (self-assessment scales) it may be advantageous if the involved parties understand each other’s views.

Further research should concentrate on how to use the assessment tool in alignment with these findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimberly Kane and Christopher Pickering for useful comments on the text. We would also like to thank the participating patients in this study, although they remain anonymous.

Disclosure statement

Ethical approval Dnr 746-09, T 612-10.

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding

This work was funded by Rehsam, Swedish Social Insurance Agency, RS11-013, and Region Västra Götaland.

References

- Swedish Council for Health Technology Assessment. Diagnosis and follow up of affective disorders - a systematic review. Report 212/2012. ISBN 978-91-85413-52-2. ISSN 1400–1403 [in Swedish].

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389.

- Fantino B, Moore N. The self-reported Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale is a useful evaluative tool in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:26.

- Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. BMJ. 2002;325:697–700.

- Ottosson J, editor. The patient-doctor relation – the art of medicine on scientific basis. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, in collaboration with Swedish Council for Health Technology Assessment (SBU); 1999.

- Pettersson A, Bjorkelund C, Petersson EL. To score or not to score: a qualitative study on GPs views on the use of instruments for depression. Family Practice. 2014;31:215–221.

- Kreuger R, Casey M. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009.

- Bjorkelund C. Structured use of a self rating instrument in the primary care consultation with patients with mild to moderate depression. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2011. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01402206.

- Svanborg P, Asberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:82–81.

- Bondolfi G, Jermann F, Rouget BW, et al. Self- and clinician-rated Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale: evaluation in clinical practice. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:268–272.

- Wikberg C, Nejati S, Larsson M, et al. Comparison Between the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale-Self (MADRS-S) and the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) in Primary Care. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17. doi: 10.4088/PCC.14m01758.

- Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:795–805.

- Giorgi A, Sketch of a psychological phenomenological method. Phenomenology and psychological research: essays. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press; 1985: 8–22.

- Carlsen B, Glenton C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:26.

- Mattisson C, Bogren M, Nettelbladt P, et al. First incidence depression in the Lundby Study: a comparison of the two time periods 1947–1972 and 1972–1997. J Affect Disord. 2005;87:151–160.

- Maier W, Gänsicke M, Gater R, et al. Gender differences in the prevalence of depression: a survey in primary care. J Affect Disord. 1999;53:241–252.

- Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient’s perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:269–286.

- Groot PC. Patients can diagnose too: how continuous self-assessment aids diagnosis of, and recovery from, depression. J Ment Health. 2010;19:352–362.

- Bilderbeck AC, Saunders KE, Price J, et al. Psychiatric assessment of mood instability: qualitative study of patient experience. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:234–239.

- Paddison CA, Abel GA, Roland MO, et al. Drivers of overall satisfaction with primary care: evidence from the English General Practice Patient Survey. Health Expect. 2013;18:1081–1092.

- Kadam UT, Croft P, McLeod J, et al. A qualitative study of patients' views on anxiety and depression. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:375–380.

- Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620.

- Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Williams JW Jr, et al. A three-component model for reengineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:441–450.

- Dowrick C, Leydon GM, McBride A, et al. Patients' and doctors' views on depression severity questionnaires incentivised in UK quality and outcomes framework: qualitative study. BMJ. 2009;338:b663.

- Hjortdahl P, Laerum E. Continuity of care in general practice: effect on patient satisfaction. BMJ. 1992;304:1287–1290.

- Oxman AD. Improving the health of patients and populations requires humility, uncertainty, and collaboration. JAMA. 2012;308:1691–1692.

- Aakhus E, Oxman AD, Flottorp SA. Determinants of adherence to recommendations for depressed elderly patients in primary care: a multi-methods study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32:170–179.

Appendix I topic guide for focus group interview

Introduction Question 1

We begin with a discussion on the MADRS-S. How did you perceive that the GP asked you to complete the form?

Where did you complete it?

Who showed how you would fill it out?

Transition Question:

How did you and the doctor use your assessments?

Discussion? Or just submit?

Key issues:

How did you perceive that your treatment has been influenced by filling out MADRS-S? (Advantages disadvantages)

How has your relationship with your GP been influenced by you completing the MADRS-S?

Introduction Question 2

Now we go back in time. How did you enroll into the study?

Transition:

The GP filled out a form while you talked.

Key issues:

How did you perceive the conversation?

Did you notice that the doctor used an interview form?

Did the GP read from the form during the conversation?

Did you get the opportunity to express what you wanted?

What relationship did you get to the doctor?

Final Questions:

Of everything we've discussed, what do you consider to be most important to appear in this report? (The question is given to all)

Have we missed something important in the discussions?

Thanks for your participation! If any of you have any questions after the meeting, you are welcome to contact me.