Abstract

Objective

To investigate to what degree adolescent males (1) value confidentiality, (2) experience confidentiality and are comfortable asking sensitive questions when visiting a general practitioner (GP), and (3) whether self-reported symptoms of poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours (HCB) affect these states of matters.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

School-based census on life, health and primary care in Region Sörmland, Sweden.

Subjects

2,358 males aged 15–17 years (response rate 84%).

Main outcome measures

The impact of poor mental health and HCBs on adolescent males’ valuing and experiencing private time with the GP, having professional secrecy explained, and being comfortable asking about the body, love and sex, analysed with structural equation modelling.

Results

Almost all respondents valued confidentiality regardless of their mental health or whether they engaged in HCBs: 86% valued spending private time with the GP, and 83% valued receiving a secrecy explanation. Among those who had visited a GP in the past year (n = 1,200), 74% had experienced private time and 42% a secrecy explanation. Three-quarters were at least partly comfortable asking sensitive questions. Adolescent males with HCBs were more likely to experience a secrecy explanation (approximative odds ratio [appOR] 1.26; p = 0.005) and to be comfortable asking about sex than their peers (appOR 1.22; p = 0.007). Respondents reporting experienced confidentiality were more comfortable asking sensitive questions (appOR 1.25–1.54; p ≤ 0.010).

Conclusion

Confidentiality matters regardless of poor mental health or HCBs and makes adolescent males more comfortable asking sensitive questions. We suggest that GPs consistently offer private time and explain professional secrecy.

Confidentiality for adolescent males has been scantily studied in relation to mental health and health-compromising behaviours.

In this study, most adolescent males valued confidentiality, regardless of their mental health and health-compromising behaviours.

Health-compromising behaviours impacted only slightly, and mental health not at all, on experiences of confidentiality in primary care.

When provided private time and an explanation of professional secrecy, adolescent males were more comfortable asking the GP sensitive questions.

Key Points

Introduction

Confidentiality for adolescents in healthcare is recommended by medical organizations worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. Confidentiality enhances adolescents’ willingness to talk about sensitive topics [Citation3–5], such as symptoms of poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours (HCBs), i.e. behaviours that can impair adolescents’ health or development [Citation6]. Other potentially sensitive topics that many adolescents want to discuss are pubertal development, relationships and sexuality, even though they can be uncomfortable raising such subjects themselves [Citation7,Citation8]. Thus, confidentiality is arguably key to a respectful discussion that includes both health-risk screening and the adolescent’s own concerns.

In this article, confidentiality is defined as consisting of two components: private time and secrecy explained. First, in order to discuss sensitive topics, adolescents need time alone with the healthcare provider, i.e. without guardians being present (private time) [Citation1,Citation3,Citation5]. Second, since the meaning and boundaries of professional secrecy can be unclear to adolescents [Citation9], they need an explicit explanation of what professional secrecy entails and when it must be breached (secrecy explained).

In Europe, private time is reported in 20–35% of adolescents’ medical encounters and secrecy explained in 40–67% [Citation10–12]. This indicates missed opportunities to discuss sensitive topics, and important health concerns may thus be overlooked. This is particularly problematic for males 15–19 years old, whose mortality is twice that of their female peers, mostly due to poor mental health and HCBs [Citation6]. Despite higher health risks, adolescent males seek healthcare less often [Citation13], and seem to receive less private time and secrecy explained than females [Citation4].

Even though confidentiality is pivotal for discussing and intervening against poor mental health and HCBs in adolescent males, studies focusing on confidentiality for adolescent males in relation to mental health and HCBs are scarce and inconclusive. Confidentiality seems to be more important to adolescent males with poor mental health than to those without [Citation14], and HCBs may increase experienced confidentiality, but reports vary [Citation4,Citation15].

General practitioners (GPs) meet many adolescent males with poor mental health or HCBs [Citation13,Citation16–18]. A stable relationship with a GP is associated with less school drop-out [Citation19] and can be an essential part in the treatment of somatic diseases [Citation20]. Adolescent males who have established such a relationship also report less barriers in seeking healthcare [Citation21], and are more likely to consult for poor mental health [Citation22] and to have their anxiety symptoms discussed [Citation23]. To the best of our knowledge, however, it is still unknown whether at-risk adolescent males receive enough confidentiality to actually reveal their problems to the GP. Few studies describe European primary care, and even fewer address whether adolescents are comfortable raising their own concerns. The aim of the study was therefore to investigate to what degree adolescent males (1) value confidentiality, (2) experience confidentiality and are comfortable asking sensitive questions when visiting a GP, and (3) whether self-reported symptoms of poor mental health and HCBs affect these states of matters.

Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study design was used. Data was obtained from the 2014 Life and Health in Youth, a triannual, school-based census on health and healthcare. Conducted by the Department of Welfare and Public Health and the Centre for Clinical Research at Region Sörmland, this census targets all schools in the county of Sörmland, Sweden. The Regional Ethical Review Board at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, approved the study design (Dnr 2014/1955-32).

Data collection

In March 2014, school employees distributed questionnaires [Citation24] to the students for completion in their classrooms during ordinary school hours. Students and parents were informed in writing beforehand about the survey and that participation was voluntary. To protect the students’ identities, all parts of the survey were entirely anonymous, and therefore a completed questionnaire was considered as informed consent. Absent students were offered a second opportunity to respond within two weeks. Because questionnaires from both occasions were submitted simultaneously, there is no available information on how many used that opportunity.

Respondents

Data from males in year 9 of compulsory school (Y9; typically 15 years old), and males in year 2 of upper secondary school (Y2U; typically 17 years old), were used (). Data from schools for children with intellectual disabilities were excluded.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire was composed of 86 questions for Y9, and 87 questions for Y2U. Of these, 80 questions were identical for Y9 and Y2U, and concerned sociodemographic background, somatic and mental health, school situation, relations to parents and peers, HCBs, health promoting behaviours, and confidentiality in primary care. Most questions originated from established questionnaires. Although never validated as a whole, the questionnaire has been previously used in several studies [Citation25–27].

Variables

Outcomes

Four outcome measures were developed for this study. All had good face validity in adolescent males.

1. Valuing confidentiality (no, yes)

Do you value

a. having the opportunity to speak with the GP in private without your parents?

b. having the meaning of professional secrecy explained?

2. GP visitor: Had visited a GP at least once during the past year (no, yes once, yes several times, do not know)

Have you visited a GP during the past year?

3. Experienced confidentiality when visiting a GP (no, yes)

When you visited the GP

c. did you have the opportunity to speak with the GP in private without your parents?

d. was the meaning of professional secrecy explained to you?

4. Being comfortable asking sensitive questions when visiting a GP (no, partly, yes)

Had you wanted to, would you have been comfortable asking about

e. your body and appearance?

f. love and relationships?

g. sex?

For simplicity, GP here denotes any physician working at a primary care centre, because nearly all such physicians in Sweden have completed (or are completing) a residency in family medicine.

Exposures

In the analyses, symptoms of poor mental health and HCBs were represented by four latent variables that were developed and validated in data from Swedish adolescent males in Y9 and Y2U through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: unsafety, gloominess, pain, and deviancy () [Citation27]. Unsafety stands for an inclination to feel unsafe in a large variety of circumstances and locations. Gloominess represents a tendency towards poor well-being, pessimism, and not enjoying school, spare time, or life. The third factor, pain, describes somatic expressions of poor mental health, including frequently experienced pain in the head, neck, back and stomach. Finally, deviancy denotes a tendency to engage in socially deviant behaviours, such as truancy, stealing, and use of tobacco, alcohol, or drugs. Factor analysis groups variables, based on their statistical associations, into validated factors (called latent variables in structural equation modelling, SEM). In the present context, the latent variables represent a continuum from health to risk (details are presented elsewhere [Citation27]). For example, deviancy extends from normal healthy experimentation to excessive engagement in multiple HCBs.

Table 2. Description of male adolescent GP visitors’ and non-visitors’ behaviours, experiences and symptoms that compose four latent variables and four manifest variables.

A confirmatory factor analysis validated the four latent variables among GP visitors in the present study (using the same methods for data generation and estimation as in the study mentioned above [Citation27]). Model fits were acceptable to good (Comparative Fit Index 0.95, Tucker-Lewis Index 0.94, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation 0.05).

Covariates

The included covariates were grade (as a proxy for age) and impaired connectedness, due to their theoretical importance. Age-related differences in health or confidentiality perception are probable, considering the physical, mental, and social development in adolescence. Connectedness to family, school, and peers are among the strongest protecting factors for poor mental health and HCBs in adolescents [Citation28,Citation29]. In the present study, four manifest variables addressed impaired connectedness to parents, supportive adults in school and spare time, and peers: difficulties talking about worries with mother, father, or other close adult, and absence of close friends (). The most salutogenic response option was coded as zero (talk easily, have several close friends).

Structural equation modelling

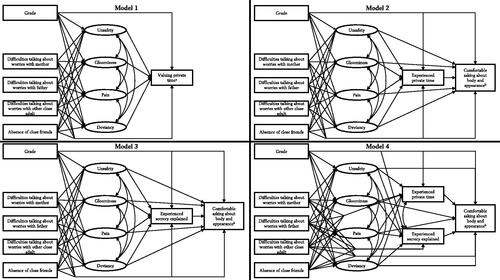

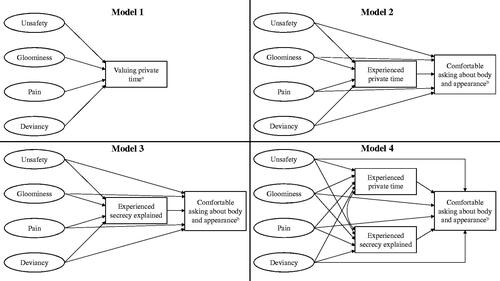

SEM was used to investigate if self-reported symptoms of poor mental health and HCBs affect whether adolescent males value confidentiality, experience confidentiality, or are comfortable asking sensitive questions when visiting a GP (, model 1). Each of these outcomes was analysed in relation to unsafety, gloominess, pain, and deviancy, and adjusted for grade and impaired connectedness (, model 1; Appendix A, ).

Figure 1. Structural models to study confidentiality and being comfortable asking sensitive questions in relation to mental health (unsafety, gloominess, and pain) and health-compromising behaviours (deviancy). Note that the cross-sectional design limits conclusive evidence regarding the causality in the relationships. Adjustment variables and allowed covariances are shown in Appendix A, .

aModel 1 was used for seven outcomes: valuing private time, valuing secrecy explained, experienced private time, experienced secrecy explained, being comfortable asking about body and appearance, love and relationships, and sex.

bModel 2, 3 and 4 were used for three outcomes: being comfortable asking about body and appearance, love and relationships, and sex.

Furthermore, because experienced confidentiality might affect being comfortable asking sensitive questions (, model 2–4), these three outcomes were adjusted for experienced private time (, model 2), experienced secrecy explained (, model 3), and both (, model 4) in addition to the variables in model 1. In total, 16 separate SEM analyses were carried out.

Data analysis

All analyses involving valuing confidentiality were carried out in the total study population (n = 2358). Experienced confidentiality and being comfortable asking sensitive questions were only analysable among GP visitors (n = 1200). Differences between GP visitors and non-visitors were analysed using Pearson’s chi-squared test (). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Missing data were treated by Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations, creating 20 imputed datasets. SEM analyses were computed using lavaan (sem.mi), PROBIT and theta parameterization. Ordinal data were used and the analyses were adapted for skewed categorical data. The regression coefficients were transformed to approximative odds ratios (appOR) [Citation30].

Software

R 3.5.1 [Citation31] (package mice [Citation32], lavaan [Citation33] and semTools) in R studio 1.1.463 and Mplus8 (Los Angeles, CA, Muthén & Muthén) [Citation34] were used.

Results

Of 68 eligible schools, 64 participated with a response rate of 84.5% (85.5% in Y9; 83.6% in Y2U), yielding 2364 completed questionnaires from male respondents (1143 in Y9, 1221 in Y2U). Six questionnaires were considered unreliable and were therefore discarded.

The study population (n = 2358) consisted of equal proportions of 15-year-old and 17-year-old adolescent males (). Most respondents reported good general health, feeling safe in their everyday life, and enjoying school and spare time (). One-sixth reported smoking regularly, one-fourth consumed alcohol every month, and one-fourth exercised less than weekly.

Half of the respondents (53%) had visited a GP the past year. Compared with non-visitors, GP visitors reported higher frequencies of somatic chronic diseases, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder or autism spectrum disorders, pain symptoms, and deviancy (). The only difference in gloominess was in the variable about exercise (GP visitors exercised more frequently). GP visitors and non-visitors reported similar frequencies of unsafety ().

Valuing confidentiality

Of all respondents (n = 2358), 86% (n = 1865) valued private time, and 83% (n = 1771) valued secrecy explained. Fewer GP visitors than non-visitors valued private time (84% versus 88%; p = 0.002) or secrecy explained (82% versus 86%; p = 0.015).

Valuing private time was not associated with unsafety (appOR 0.89; p = 0.257), gloominess (appOR 1.16; p = 0.123), pain (appOR 0.98; p = 0.826), or deviancy (appOR 1.02; p = 0.800), nor was valuing secrecy explained associated with gloominess (appOR 1.17; p = 0.082), pain (appOR 1.04; p = 0.592), or deviancy (appOR 1.11; p = 0.163). However, unsafety might decrease valuing secrecy explained (appOR 0.82; p = 0.050). Moreover, compared with Y9, a higher number of adolescent males in Y2U valued private time (appOR 1.32; p < 0.001) and secrecy explained (appOR 1.15; p = 0.019). Impaired connectedness had no impact on valuing confidentiality. Altogether, among all respondents, valuing confidentiality was affected by older age, but not by poor mental health or HCBs.

Experienced confidentiality when visiting a GP

Among GP visitors, 74% (n = 837) had experienced private time and 42% (n = 456) had experienced secrecy explained. Of the 924 GP visitors who valued private time, 77% had experienced it. Correspondingly, of the 850 GP visitors who valued secrecy explained, 47% had experienced it.

Deviancy increased the odds of experiencing secrecy explained (appOR 1.26; p = 0.005; ), and older age increased the odds of experiencing private time. None of unsafety, gloominess, pain or impaired connectedness influenced experienced confidentiality.

Table 3. Experienced confidentiality (no, yes) and being comfortable asking sensitive questions (no, partly, yes) in relation to poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours among adolescent males, shown as approximative odds ratios.

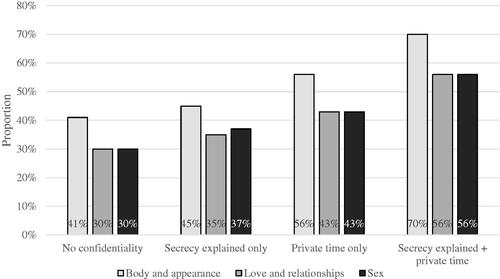

Being comfortable asking sensitive questions when visiting a GP

Approximately half of the GP visitors would have been comfortable asking sensitive questions and an additional one-fourth reported being partly comfortable (asking about their body and appearance: yes 57% (n = 631), partly 22% (n = 246); about love and relationships: yes 45% (n = 492), partly 24% (n = 263); and about sex: yes 45% (n = 483), partly 24% (n = 262)). The proportion increased with experienced confidentiality (). Compared with those who reported neither private time nor secrecy explained, nearly twice as many were comfortable asking sensitive questions among those who experienced both private time and secrecy explained.

Figure 2. Proportions of adolescent males being comfortable asking about their body and appearance, love and relationships, or sex when visiting a general practitioner in relation to experienced confidentiality: if neither private time, nor secrecy explained were experienced; if secrecy explained was experienced; if private time was experienced; or both. Reports from 1200 Swedish adolescent males (Life and Health in Youth 2014).

As presented in , deviancy increased the odds of being comfortable asking about sex, but unsafety, gloominess, or pain did not influence the outcome at all. Difficulties talking about worries with close adults other than parents, and absence of close friends decreased the odds of being comfortable asking sensitive questions. Confidentiality, in particular experienced private time, increased the odds of being comfortable asking about body, love and relationships, and sex.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

In the present study, almost all adolescent males valued confidentiality regardless of their mental health or engagement in HCBs. Adolescent males reporting multiple HCBs experienced more frequently secrecy explained and were more comfortable asking about sex than peers with fewer HCBs. With these few exceptions, neither symptoms of poor mental health nor HCBs influenced adolescent males’ experienced confidentiality or perception of being comfortable asking sensitive questions. Unsurprisingly, adolescent males were more comfortable asking sensitive questions when private time and secrecy explained were provided.

Strengths and weaknesses

The greatest strength of this study is the use of SEM, which takes the well-known clustering of HCBs [Citation35] into account by using a latent variable representing HCBs instead of considering the HCBs one by one [Citation36]. Similarly, the latent variables also enabled use of plenty of poor mental health symptoms instead of psychiatric diagnoses, mirroring the diversity of poor mental health complaints in primary care [Citation13]. SEM also uses a series of regressions in which complex relationships can be analysed simultaneously [Citation36]. However, the cross-sectional design limits conclusive evidence regarding the causality in the relationships [Citation36].

Another strength was the use of self-reported data from an anonymous school-based study with a high response rate, which yielded a large sample and allowed analyses of valuing confidentiality among both GP visitors and non-visitors. Adolescents’ self-reported data of health and healthcare use can be considered reliable [Citation37] and the anonymity is supposed to further improve the data’s accuracy.

Some weaknesses need to be mentioned. First, only associations included in the models are analysed. Important aspects may have been overlooked, and as a result, unmeasured confounders. Another limitation is that the outcomes regarding asking sensitive questions are hypothetical, and may not correctly reflect what really would have happened in the consultation.

Findings in relation to other studies

Valuing confidentiality

Valuing confidentiality was influenced by neither poor mental health nor HCBs. To the best of our knowledge, this association has not been studied before. Given that confidentiality concerns are more common among adolescent males with poor mental health [Citation14], we found the results a bit surprising. It is possible that uncovering such differences requires more detailed questions. However, two covariates stood out. First, in accordance with previous studies, older adolescent males valued confidentiality more than their younger counterparts [Citation12,Citation38], which likely reflects their growing autonomy and increasing interest in discussing sensitive issues with an adult. Second, GP visitors valued confidentiality less than non-visitors, which may indicate differences between GP visitors’ experiences and non-visitors’ expectations. It is possible that many GP-visitors remembered uncomplicated visits, in which confidentiality was not an important issue, whereas the non-visitors visualized other kinds of visits. Another possibility is that non-visitors have refrained from seeking healthcare due to confidentiality concerns as previously described [Citation14]. If true, this would imply that primary care does not deliver appropriate healthcare to all adolescent males, thus jeopardizing their health. Although the present study only regards primary care visits, concerns about lacking confidentiality should be applicable to any healthcare service that fails to explicitly state its commitment to confidentiality.

Experienced confidentiality

Three-quarters of the GP visitors reported private time, but less than half of them had experienced secrecy explained. This may be deeply problematic. Given that many adolescent males are unfamiliar with the limits of confidentiality [Citation9], private time without secrecy explained can result in broken trust, e.g. if adolescent males come to disclose, unaware of the consequences, matters that require breaching confidentiality. Such experiences may negatively affect future healthcare seeking, compromising their health [Citation1,Citation3,Citation9].

Adolescent males with HCBs more often experienced secrecy explained, but no such effect was seen for those with symptoms of poor mental health. This finding contrasts with a study in American primary care, in which secrecy explained had a weak association with depressive symptoms, but was unrelated to substance use or sexual activity [Citation15]. Conversely, in another study from the U.S., the regular health-care provider more often explained the professional secrecy to sexually active adolescents [Citation4], a finding that partly agrees with the present study. One plausible explanation is that some adolescent males with HCBs had observable attributes, e.g. a box of snuff in his pocket, reminding the GP of explaining professional secrecy, whereas poor mental health may be easier to hide. Also, it indicates that GPs presume that adolescent males with HCBs need confidentiality more than their peers. However, the present study emphasizes that regardless of HCBs, almost all adolescent males want confidentiality.

Asking sensitive questions

Nearly half of the adolescent males were comfortable asking sensitive questions; a perception highly influenced by experienced confidentiality. Although confidentiality is well known to facilitate discussions of sensitive topics brought up by the health-care provider [Citation3–5,Citation9], this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study demonstrating that confidentiality makes adolescent males more comfortable raising their own concerns. By revealing their unmet health needs, adolescent males are more likely to receive the interventions that they need.

Adolescent males engaged in HCBs were more comfortable asking about sex, which can be interpreted as sexually active adolescent males being more at ease discussing sex than their peers. Notably, adolescent males without close friends or supportive adults other than parents were less comfortable discussing sensitive questions than their peers, whereas they valued confidentiality as much as the other respondents. This may indicate a vulnerable group that needs the GP’s attention. To find out how to make these adolescent males more comfortable asking sensitive questions, future, preferably qualitative, studies are needed.

Meaning of the study

Confidentiality matters regardless of poor mental health or HCBs. The present study adds the perspective of adolescent males, illuminating that private time and secrecy explained are both needed for them to be comfortable sharing their own health concerns, and consequently to receive appropriate care. As to the GPs role, our results suggest that developing a habit of offering private time and explaining professional secrecy would be beneficial. Considering the heavy workload that many GPs face [Citation39], this might be perceived as an unrealistic task. One approach that might fit the bill, however, is a standardized split-visit model [Citation1,Citation40]. The encounter starts by explaining the meaning and the limits of confidentiality (secrecy explained), followed by the private time, which includes sensitive parts of history taking and examination. Finally, the GP and the adolescent male summarize the assessment and proposed actions to the parents. As the present study highlights the importance of confidentiality for adolescent males to raise their own worries, we also suggest that GPs encourage such questions during the private time.

Ethical approval

Students and parents were informed in writing beforehand and hence a completed questionnaire was regarded as the student’s informed consent. According to Swedish law (The Ethical Review Act, 2003:460), no parental approval is needed for participants 15 years old and above. The study design was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm (Dnr 2014/1955-32) and is in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating adolescents and school staff.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ford C, English A, Sigman G. Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper for the society for adolescent medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004; Aug35(2):160–167.

- World Health Organization. Global standards for quality health care services for adolescents. Geneva 2015. p. 40.

- Ford CA, Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL, et al. Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(12):1029–1034.

- Grilo SA, Catallozzi M, Santelli JS, et al. Confidentiality discussions and private time with a health-care provider for youth, United States, 2016. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(3):311–318.

- Santelli JS, Klein JD, Song X, et al. Discussion of potentially sensitive topics with young people. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20181403.

- Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2383–2401.

- Jeannin A, Narring F, Tschumper A, et al. Self-reported health needs and use of primary health care services by adolescents enrolled in post-mandatory schools or vocational training programmes in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(1–2):11–18.

- Tudrej BV, Heintz AL, Ingrand P, et al. What do troubled adolescents expect from their GPs? Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22(4):247–254.

- Kadivar H, Thompson L, Wegman M, et al. Adolescent views on comprehensive health risk assessment and counseling: assessing gender differences. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):24–32.

- Deneyer M, Devroey D, De Groot E, et al. Informative privacy and confidentiality for adolescents: the attitude of the Flemish paediatrician anno 2010. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(9):1159–1163.

- Jeremic Stojkovic V, Cvjetkovic S, Matejic B, et al. Adolescents’ right to confidential health care: knowledge, attitudes and practice of pediatricians and gynecologists in the primary healthcare sector in Belgrade, Serbia. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(8):1235–1246.

- Rutishauser C, Esslinger A, Bond L, et al. Consultations with adolescents: the gap between their expectations and their experiences. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(11):1322–1326.

- Piiksi Dahli M, Brekke M, Ruud T, et al. Prevalence and distribution of psychological diagnoses and related frequency of consultations in Norwegian urban general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(2):124–131.

- Lehrer JA, Pantell R, Tebb K, et al. Forgone health care among U.S. adolescents: associations between risk characteristics and confidentiality concern. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(3):218–226.

- Gilbert AL, McCord AL, Ouyang F, et al. Characteristics associated with confidential consultation for adolescents in primary care. J Pediatr. 2018;199:79–84 e1.

- Oja C, Edbom T, Nager A, et al. Awareness of parental illness: a grounded theory of upholding family equilibrium in parents on long-term sick-leave in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2021;39(3):268–278.

- Gullbra F, Smith-Sivertsen T, Rortveit G, et al. To give the invisible child priority: children as next of kin in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014; Mar32(1):17–23.

- Gieteling MJ, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Passchier J, et al. The course of mental health problems in children presenting with abdominal pain in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30(2):114–120.

- Homlong L, Rosvold EO, Haavet OR. Can use of healthcare services among 15-16-year-olds predict an increased level of high school dropout? A longitudinal community study. BMJ Open. 2013; 193(9):e003125.

- Brodwall A, Brekke M. General practitioners’ experiences with children and adolescents with functional gastro-intestinal disorders: a qualitative study in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2021; 39(4):543–551.

- Kang M, Robards F, Luscombe G, et al. The relationship between having a regular general practitioner (GP) and the experience of healthcare barriers: a cross-sectional study among young people in NSW, Australia, with oversampling from marginalised groups. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):220.

- Mauerhofer A, Berchtold A, Michaud PA, et al. GPs’ role in the detection of psychological problems of young people: a population-based study. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(566):e308-14–e314.

- Haavet OR, Šaltytė Benth J, Gjelstad S, et al. Detecting young people with mental disorders: a cluster-randomised trial of multidisciplinary health teams at the GP office. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e050036.

- Region Sörmland. Liv och Hälsa Ung: region Sörmland; [cited 2019 February 8]; questionnaire]. Available from: https://samverkan.regionsormland.se/utveckling-och-samarbete/statistik/folkhalsoundersokningar/liv-och-halsa-ung-2020/liv–halsa-ung. /.

- Kvist T, Dahllof G, Svedin CG, et al. Child physical abuse, declining trend in prevalence over 10 years in Sweden. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(7):1400–1408. Jul

- Nylander C, Seidel C, Tindberg Y. The triply troubled teenager–chronic conditions associated with fewer protective factors and clustered risk behaviours. Acta Paediatr. 2014; Feb103(2):194–200.

- Haraldsson J, Pingel R, Nordgren L, et al. Understanding adolescent males’ poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours: A factor analysis model on Swedish school-based data. Scand J Public Health. 2022;50(2):232–244. 10.1177/1403494820974555.

- Blum LM, Blum RW. Resilience in adolescence. In DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Santelli JS, editors. Adolescent health: understanding and preventing risk behaviors. Vol. 1st;1. Aufl.;1;. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2009. p. 51–76.

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–1652.

- Pingel R. Some approximations of the logistic distribution with application to the covariance matrix of logistic regression. Statistics & Probability Letters. 2014; Feb85:63–68.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria; 2016.

- van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Soft. 2011;45(3):1–67.

- Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Soft. 2012; May48(2):1–36.

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Eighth ed. Los Angeles, CA. 1998. 2017.

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991; Dec12(8):597–605.

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. (Book, Whole).

- Santelli J, Klein J, Graff C, et al. Reliability in adolescent reporting of clinician counseling, health care use, and health behaviors. Med Care. 2002;40(1):26–37.

- Song X, Klein JD, Yan H, et al. Parent and adolescent attitudes Towards preventive care and confidentiality. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(2):235–241.

- Johnsson L, Nordgren L. The voice of the self: a typology of general practitioners’ emotional responses to situational and contextual stressors. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2022; Jun40(2):289–304.

- EuTEACH - European training in effective adolescent care and health. EuTEACH Modules: Module A3 [cited 2021. June 30]. Available from: https://www.unil.ch/euteach/en/home/menuinst/what-to-teach/euteach-modules-1.html.

Appendix A

Figure A1. The structural models to study confidentiality and being comfortable asking sensitive questions in relation to poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours, here shown with all included adjustment variables and covariances. Each outcome was tested in relation to poor mental health (unsafety, gloominess, and pain) and health-compromising behaviours (deviancy), adjusted for grade (as a proxy for age) and impaired connectedness (difficulties talking about worries with mother, father, or other close adult, and absence of close friends). Covariances were allowed between the four latent variables (unsafety, gloominess, pain, and deviancy) in all models and between experienced private time and experienced secrecy explained in Model 4.

aModel 1 was used for seven outcomes: valuing private time, valuing secrecy explained, experienced private time, experienced secrecy explained, being comfortable asking about body and appearance, being comfortable asking about love and relationships, and being comfortable asking about sex.

bModel 2, 3 and 4 were used for three outcomes: being comfortable asking about body and appearance, being comfortable asking about love and relationships, and being comfortable asking about sex.