Abstract

Objective and intervention

To explore contextual factors influencing residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs established as a result of a municipally driven GP coverage intervention in a disadvantaged neighbourhood in Copenhagen with a GP shortage.

Design

A qualitative study design informed by realist methodology was used to conduct the study. Data were obtained through a survey with residents (n = 67), two focus group interviews with residents (n = 21), semi-structured interviews with the project- and local community stakeholders (n = 8) and participant observations in the neighbourhood. The analysis was carried out through systematic text condensation and interpreted and structured by Pawson’s layers of contextual influence (infrastructural and institutional). The concept of collective explanations by Macintyre et al. and Wacquant’s framework of territorial stigmatisation were applied to analyse and discuss the empirical findings.

Subject and setting

Residents from five local community organisations in a disadvantaged neighbourhood in Copenhagen.

Main outcome measures

Infrastructural and institutional contextual factors influencing residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs.

Results

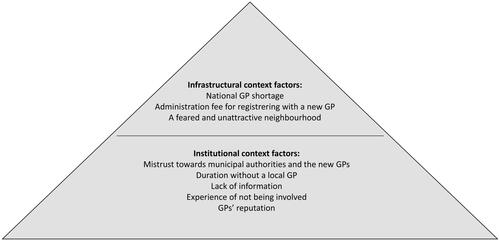

Infrastructural contextual factors included the national shortage of GPs, the administration fee for registering with a new GP, and the neighbourhood’s reputation as being feared and unattractive for GPs to establish themselves. Institutional contextual factors included mistrust towards municipal authorities and the new-coming GPs shared by many residents, the duration without a local GP, GPs’ reputation and a perceived lack of information about the GP coverage intervention, and an experience of not being involved.

Conclusion and implication

Infrastructural and institutional contextual factors influenced residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs. The findings will be helpful in adjusting, implementing, and disseminating the intervention and developing and implementing future complex interventions in disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

KEY POINTS

GP coverage interventions in disadvantaged neighbourhoods with a GP shortage should address contextual factors influencing residents’ intentions to register with new-coming GPs

The neighbourhood’s negative reputation led residents to question the GPs’ motives for coming and whether they would stay permanently

Residents’ mistrust of both municipal authorities and the new GPs, combined with a lack of information and a feeling of exclusion from the decision-making process, influenced residents’ intentions to register negatively

Residents needed more information on the GPs’ ambitions and intentions for choosing their neighbourhood to be convinced that they would be there permanently

Introduction

In Denmark, as in many other countries, primary care lacks general practitioners (GPs) [Citation1–3]. The GP shortage problem is particularly acute in rural and disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods [Citation4–8]. A Danish study from 2017 showed that nearly every second disadvantaged neighbourhood listed on the government’s parallel society list (previously known as the ghetto list), lacks a local GP [Citation9]. The lack of local GPs is unfortunate, as a short distance to GPs is essential in preventing, treating and managing diseases [Citation9,Citation10], especially because people living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods have a greater need for consulting their GP due to higher morbidity rates with multiple conditions such as type 2 diabetes [Citation11–14]. In addition to a high morbidity rate, the residents are also characterised by having low socioeconomic status and great ethnic diversity [Citation11,Citation12]. Socio-cultural diversity, low health literacy [Citation15,Citation16], and linguistic barriers all contribute to the complexity. Furthermore, residents’ issues require specialised knowledge because they may be related to trauma from torture or war [Citation6]. Finally, disadvantaged areas have a higher crime rate than the national average [Citation17]. These complexities increase GPs’ workload, making it difficult to attract GPs to these areas [Citation4,Citation6].

A needs assessment survey conducted in a disadvantaged neighbourhood in Copenhagen with a GP shortage revealed that most residents participating in the study found the distance to their GP challenging and thus, preferred a local GP [Citation18]. In line with this, another qualitative study conducted in the same neighbourhood focusing on residents’ access to healthcare services addressed the need for a local GP, as the distance to the GP outside the neighbourhood made it difficult for most residents to access their GP, as it required the use of public transport, which they described as inadequate and expensive [Citation9].

To improve access to GPs in this neighbourhood, the Municipality of Copenhagen, the Capital Region of Denmark, and the General Practitioners’ Organisation developed a GP coverage intervention to attract local GPs. However, it is unclear, whether the establishment of local GPs will lead to residents registering with one of them. Studies have shown that trust and continuity of care are essential for choosing a GP, particularly among those with chronic diseases [Citation19]. These factors may, therefore, be more important than having a short distance. Furthermore, studies, not the least by medical sociologist Sally Macintyre and her co-authors, have focused on neighbourhoods and health, showing that contextual factors embedded in the neighbourhood, such as the physical and social environment, the area’s reputation, the levels of crime, as well as norms, traditions, and interests shared by residents of the neighbourhood, impact residents’ health, health beliefs, and use of health care services [Citation13,Citation20,Citation21]. Thus, these contextual factors may also influence residents’ preferences when choosing health services, including a local GP [Citation20,Citation22]. The organization of the Danish healthcare system is a highly political issue, however, the public debate tends to lack the citizens’ perspective.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated how these contextual factors related to the neighbourhood influence residents’ GP preferences. With the GP coverage intervention in a disadvantaged neighbourhood with a GP shortage as an example, this study, therefore, seeks to fill this knowledge gap by exploring how contextual factors related to the neighbourhood influence residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs.

Study aim

This study explored residents’ intentions to register with new-coming GPs established as a result of a municipally driven GP coverage intervention in a disadvantaged neighbourhood in Copenhagen with a GP shortage. A particular emphasis was placed on how contextual factors would prevent residents from registering with one of the new-coming GPs.

GPs in the Danish healthcare system

Denmark has a universal healthcare system that is mainly free of charge, as general taxes finance the healthcare services [Citation23]. The healthcare system is structured at three political and administrative levels: the state, regions, and municipalities. The municipalities are responsible for rehabilitation outside hospitals, disease prevention and health promotion [Citation24]. The regions are responsible for health services provided by GPs. GPs are responsible for the primary and continuous care of the patients affiliated with their specific practice. Furthermore, except for emergencies, GPs serve as gatekeepers to secondary and tertiary healthcare services, thus playing a critical role in patients’ access to healthcare services [Citation25]. GPs in Denmark are self-employed and work in singlehanded practices or collaboration in clinics with two or more GPs. They are reimbursed for their services by the region. Nearly all citizens (99%) are listed with a specific GP, which they can consult for free. GPs are organised in the Organization of General Practitioners.

The GP coverage intervention

The GP coverage intervention was developed shortly after the last local GP left the neighbourhood in 2015 as it was not possible to attract a new GP. It was developed by the Capital Region of Denmark, the Municipality of Copenhagen and the GPs’ organisation and evaluated by researchers from the University of Copenhagen. It was a novel collaboration as municipality involvement in GP coverage was the first of its kind in Denmark.

The intervention aimed to attract GPs to a disadvantaged neighbourhood with a GP shortage in Copenhagen. Thereby giving the residents an option to register with a local GP. To attract GPs, the municipality’s role was to assist the GPs in finding suitable premises, which otherwise often is difficult to find in Copenhagen due to high housing prices and a lack of premises. Also, as part of the intervention a social- and healthcare worker was employed to assist the GPs in their work with patients who need help with social related issues, such as housing shortage, unemployment, or serious social problems in the family [Citation26].

The setting

The neighbourhood is one of Denmark’s largest social housing neighbourhoods, with around 6,600 residents living in 2,500 apartments owned and managed by two non-profit social housing associations [Citation27].

Furthermore, it is an area with high diversity, with approximately 80% of residents having immigrant backgrounds representing more than 80 nationalities [Citation27]. The residential composition is considered socially vulnerable as many residents have low levels of income, education, employment rate, social relations [Citation27] and poor health (the neighbourhood has the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Copenhagen) [Citation11]. Finally, the neighbourhood is challenged by a high crime rate, which, combined with the residential composition, placed the neighbourhood on the government’s list of ‘parallel societies’ from 2010 until 2022 [Citation28].

Material and methods

Theoretical framework

The intervention can be described as complex as it contains multiple components, outcomes, and stakeholders [Citation29]. Therefore, we used the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework for complex interventions to investigate residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs [Citation29]. We drew upon realist methodology [Citation30], recommended by the MRC framework, as a theory-based approach [Citation31] to explore the influence of context and identify barriers that could prevent residents who wish to have a local GP from registering with the new-coming GPs.

We defined ‘contextual factors’ as ‘social rules, values, sets of interrelationships that operate within times and spaces that either constrain or support the activation of programme mechanisms’, thus making the intervention work [Citation30].

Furthermore, to better distinguish between various contextual factors, we applied Pawson’s categorisation of contextual influence in layers [Citation32], focusing on the infrastructural and institutional layers. The infrastructural layer is the wider society and welfare system, within which the intervention is embedded. Contextual factors at this layer include the wider political, social, economic and cultural aspects of society. The institutional layer is the setting in which the intervention is implemented (in this case the disadvantaged neighbourhood). Contextual factors at this layer include e.g. the historical context, culture, sociodemographic characteristics, resources, norms and practices embedded in the neighbourhood [Citation32]. To define culture, we drew upon the definition by Kleinman stating that:

Culture is inseparable from economic, political, religious, psychological, and biological conditions. Culture is a process through which ordinary activities and conditions take on an emotional tone and a moral meaning for participants [Citation33].

Macintyre et al. [Citation20] define collective explanations as:

norms, traditions, and interests shared by residents of a given neighbourhood that are a result of the historical and socio-cultural factors that characterize the neighbourhood’ [Citation20].

To strengthen the perspective on how the collective explanations of Macintyre et al. affect residents’ intentions to register with the new-coming GPs, the framework of territorial stigmatization by Wacquant [Citation34] was added. Territorial stigma is defined as a negative and stereotypical representation of disadvantaged neighbourhoods that residents partly internalize [Citation34]. According to Wacquant, this internalisation of territorial stigmatisation causes residents to feel guilty and ashamed, to deny belonging to the neighbourhood and to distance themselves from the area and its neighbours [Citation34].

Recruitment of participants and data collection

We conducted a qualitative study using various methods, sources and data material. Understanding of the GP coverage intervention was achieved by oral information and project documents provided by the municipality. The municipality assisted in establishing access to the neighbourhood through a local gatekeeper who worked as a manager at the local senior activity centre. The manager then assisted the first author in gaining access to five local community organisations, such as the local church, a senior activity centre, a social activity centre for socially vulnerable men and women, a food club for men, and a homework café for adolescents. Representatives from the project stakeholders (the region, the municipality, and the GPs’ organisation) were recruited via an email request.

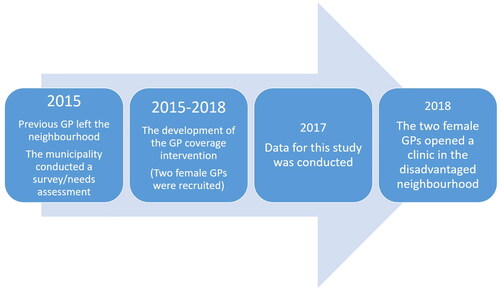

All data were collected by the first author from November to December 2017, approximately 2.5 years after the previous GP retired and six months before the new GPs opened their clinic in the neighbourhood, as shown in the timeline (). Data included individual interviews with the project- and local community stakeholders (n = 8), an open-ended survey questionnaire (n = 67) with residents, two focus groups with residents and participant observations of events at the five local organisations). The first author visited the neighbourhood several times to interview representatives from local community organisations, participate in local events at the five local organisations, distribute surveys and conduct focus groups.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with relevant stakeholders, including the project stakeholders (n = 3) and representatives from local community organisations (n = 5). To gain insights into the GP coverage intervention, its purpose, elements, and expected outcomes, and to obtain information on the new-coming GPs, we reviewed the project documents and interviewed the three project stakeholders. Interviews with representatives from the local community organisations were grouped into three types and included: 1) the district political committee (political stakeholder), 2) the local social worker (community worker), and 3) the neighbourhood management, the senior activity centre, the social activity centre and the social housing association board (community leaders). The interviews gave insights into the various local organisations and their respective resident groups. Furthermore, it provided us with the local community stakeholders’ perspectives on issues such as the duration without a local GP, the consequences of the GP shortage, and their perspectives on the GP coverage intervention. As the local stakeholders have frequent contact with many of the residents, the interviews provided contextual knowledge to understand residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs and potential barriers inhibiting those who otherwise prefer a local GP from registering. The interviews were conducted at the stakeholders’ respective workplaces and were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Survey

Inspired by the needs assessment survey conducted by the municipality in 2015, we conducted a follow-up survey to determine whether many residents still found the distance to their GP difficult and to get an impression of how many residents were planning to register with the new-coming GPs. The survey (n = 67) entailed six open-ended questions concerning 1) residents’ current distance to GP; 2) how they experience the distance; 3) whether they want to register with one of the two new-coming GPs; 4) whether the sex of the GPs matters; 5) how they define a good GP; and 6) what other types of health professionals they would like to have in their neighbourhood.

In this study, we used survey data from questions two, three and four. The survey was developed in cooperation with the senior activity centre manager, who also helped the municipality with the needs assessment survey from 2015. We used the manager’s extensive knowledge of the neighbourhood and its residents to improve the content and clarity of the questions, making them more understandable to the residents. The survey was distributed to five community organisations (See ). The selected locations also participated in the survey from 2015 and ensured a broad representation of men, women, adults, adolescents, the elderly, families with children, and vulnerable and ethnic groups. The survey was conducted from the 7th to the 22nd of December 2017. As some residents could not read or write, the first author and professionals affiliated to the five community organisations assisted them in translating and understanding the survey.

Table 1. Data sources, resident types, and collection sites.

Focus group interviews

The two focus group interviews were with users (n = 15) of the social activity centre and with members of the senior activity centre (n = 6) (See ). Both focus groups arose spontaneously during the survey distribution at the two data collection sites because the residents expressed a desire to talk about their experiences without a local GP and to express their thoughts on registering with one of the new-coming GPs. The themes of the focus group were based on the survey questions.

The focus groups were conducted at their respective places in December 2017 and lasted approximately one hour. The managers participated in both focus groups, ensuring that the residents felt safe and helped elaborate some of the questions when needed. After the focus groups, all participants were invited to answer the survey. The focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Participant observation

Participant observations took place in connection with the survey distribution, which was planned in conjunction with local events in the five organizations. This was done to ensure that as many users as possible were present when the survey was distributed. The first author observed these five events, which included a Christmas gathering at the social activity centre, a church service and communal meal at the Church and House of Dianoia, a bingo arrangement at the senior activity centre, a meeting session the men’s food club, and a meeting session at the homework café for adolescents. The observation of the events lasted between 1.5 and 3 hours. The observations gave insights into the physical, material, and institutional surroundings, residents’ characteristics, and social interactions between the residents and local stakeholders [Citation20]. Moreover, it allowed for informal conversations with various residents regarding their intentions to register with the new-coming GPs.

Participant observation is an ideal method to explore the more ‘invisible’ and unnoticed contextual factors embedded in residents’ daily lives that cannot be investigated through interviews and surveys, as residents most often are unaware of them [Citation35,Citation36].

All observations were recorded in field notes, which included descriptive and analytical field notes [Citation35] (e.g., impressions from the events at the five local organisations, characteristics of residents and local stakeholders who participated in the interviews and/or completed the survey, and relevant information obtained through informal conversations with residents and local stakeholders).

Data analysis

The survey responses were structured in tables in Microsoft Word. All data were collected and managed in NVivo 12 [Citation37] and analysed using systematic context condensation and its four steps: 1) Reading all the material to get a general sense of the data and identify preliminary themes related to the study aim.; 2) Identifying and sorting meaning units, representing residents’ perspectives on new coming GPs according to Pawson’s two contextual layers; 3) Condensation of units and themes; 4) synthesising data into themes with similar code groups [Citation26]. The first author SG undertook analytical steps one and two. The remaining analysis was discussed among all authors to ensure that categories and subcategories covered all the datasets.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the Helsinki II Declaration’s ethics codes and was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The survey respondents were anonymous to ensure the anonymity of the study participants. Similarly, informants who participated in the interviews were pseudonymised. Finally, the neighbourhood is anonymised.

Results

Residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs

After three years without a local GP, most residents expressed gratitude for the return of local GPs. However, when asked if they planned to register with one of the new GPs, only 17 out of 67 residents said yes (). 13 respondents said ‘maybe’ or ‘don’t know,’ while nearly half (n = 35) said no. Many respondents in the latter group stated that they were satisfied with their current GP outside the neighbourhood, whom they knew and trusted, and that they would only register with one of the new-coming GPs if their current GP retired. This was echoed in the focus groups.

Table 2. Residents’ answer regarding their intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs.

Another reason why many respondents preferred keeping their current GP was that many residents have adapted to having a longer distance to their GP. The survey results showed that two-thirds (n = 42) thought the distance was ‘fine’ or ‘ok’. In contrast ‘only’ one-third (n = 22) thought it was difficult, which is a notable change from a similar survey conducted by the municipality after the previous GP left the neighbourhood. In that survey from 2015, two-thirds of respondents reported the distance as difficult [Citation18].

Contextual factors influencing residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs

The analysis revealed eight contextual factors that influenced residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs (). At the infrastructural layer (the welfare system), the contextual factors included: the national GP shortage, the administration fee for registering with a new GP and the neighbourhood’s negative reputation as feared and unattractive for GPs to establish themselves. At the institutional layer (the neighbourhood), the contextual factors included:) mistrust towards municipal authorities and the new-coming GPs, the duration without a local GP, a perceived lack of information, an experience of not being involved, and GPs’ reputation,.

The infrastructural layer of contextual influence

National GP shortage and administration fee for registering with a GP

Firstly, the fact that Denmark has a national problem with a GP shortage was identified as a barrier as it made many residents hesitant to register with one of the new-coming GPs. They felt the decision to change was attached with many uncertainties and no options for undoing. If they registered with one of the new-coming GPs, they were afraid they would be unable to change their decision as access to their current GP would be restricted. This concern is exemplified in the following quote from a resident who experienced this scenario:

I have tried it before and changed GP; I heard from others that she or he was good (…), but he was not good, and then you must go back. Then, your GP is no longer accepting new patients. And who should you then choose? The only GP open to patients is an 87-year-old GP. (Resident, Social activity centre)

Another barrier that arose from the analyses, was the administration fee of nearly 30 Euros per person for registering with a new GP. According to many local stakeholders, the fee would prevent some residents from registering with one of the new-coming GPs, as some residents are financially challenged to the point where they cannot afford medicine or bus fare to their current GP outside the neighbourhood. In addition to being a financial barrier, some residents felt the fee was unfair because it was not their fault that they had been without a local GP. Some residents with this point of view did not want to change because they believed they had been unfairly treated.

A feared and unattractive neighbourhood for GPs to establish themselves

Following the concept of collective explanations by Macintyre et al. an area’s reputation affects its residents’ health, health beliefs and use of healthcare services [Citation20] and according to Wacquant, residents of a given neighbourhood that are being stigmatized at a society level, tend to internalize this stigma. Using the perspective of territorial stigma from Wacquant et al. [Citation34] to understand the collective explanations of the studied neighbourhood, it was evident in the present study that the media’s negative and stereotypical representation of the neighbourhood as an unsafe area with high crime rates influenced the residents’ identity. Hence, this seemed to affect the intentions to register with the new-coming GPs. Further, the duration without a local GP had enhanced the narrative shared by many residents that they lived in a feared and unattractive neighbourhood where liberal professionals showed little interest in establishing themselves. Consequently, this narrative negatively influenced how many residents perceived the new-coming GPs, which made some residents question who the GPs were, why they were coming, and whether they would reside permanently. Many residents, therefore, needed more information on the GPs’ ambitions and intentions for choosing their neighbourhood to be convinced that they would be there permanently:

It must be a bit of a story because otherwise, people think, "Why do the GPs come here? Why would anyone voluntarily expose themselves to the chaos that exists here?" (Resident, Senior activity centre)

The institutional layer of contextual influence

Mistrust towards municipal authorities and the new-coming GPs

The perspective of territorial stigma [Citation34], also enlightened how many residents were mistrustful and sceptical towards municipal authorities and thus the new-coming GPs. This sense of mistrust and scepticism was linked to negative interactions with municipal authorities such as local job centres, where residents receiving cash benefits frequently felt judged and unfairly treated. Furthermore, the findings from the interviews and observations revealed that many residents shared an understanding of the healthcare system, with hospitals being the most ‘prestigious’, followed by GPs and then municipal authorities. The fact that the GPs were established as part of a municipally driven intervention therefore raised questions about whether it was a ‘municipal clinic’ and thus not an independent ‘real’ clinic with competent GPs. According to a local stakeholder, some residents would prefer to keep their current GP if they had the impression that the new GPs were associated with the municipality:

It should look as if it is their own practice. It should not look like a municipal practice. No way. (Local community worker)

It is important to state that they (the municipality, red.) have chosen some highly skilled GPs (…). It is vital to tell people that they are the best. (Local community worker)

The duration without a local GP, lack of information and an experience of not being involved in the intervention

According to documents and interviews with the project stakeholders, the municipality and the region began developing the GP coverage intervention shortly after the previous local GP left the neighbourhood. However, residents and most local stakeholders described being unaware that the public authorities were addressing the GP shortage problem. Several residents explained how during the three years without a local GP, they attempted to ask the municipality for assistance and inform them about the consequences of not having a local GP. However, they felt ignored and ‘left on their own’. Residents’ perceptions of the GP coverage intervention and the GPs were thus negatively influenced by the duration without a local GP and lack of information about the establishment of a new GP clinic. This became clear during data collection, for example, when a resident refused to respond to the survey due to disappointment and the perception that the municipality had been too slow:

If you had asked me to fill in the survey two years ago, I might have said yes, but I have struggled so much with the municipality to get a GP here that now it doesn’t matter. (Resident, Local church)

There are some people sitting far away from X (the neighbourhood, red) and deciding what X needs. You must ask the residents who live here instead (…). It will change how well it is received. The culture centre out here is the same (…), and right now, the residents feel like, "well, it’s not our cultural centre" because they have not been involved in the process. (Local community leader)

GPs’ reputation

GPs’ reputation was another key contextual factor as residents’ decisions on registering with one of the new-coming GPs were highly influenced by the GPs’ reputation in the neighbourhood. The GPs, therefore, had to establish trust among the residents by building a positive reputation in the neighbourhood:

You gain trust by hearing from people who have changed GP and say, "She was a really good GP", then you start to think, ‘Well, ok, she might be very good’. So, these are the kinds of recommendations you need to hear. (Resident, Social activity centre)

Discussion

Residents welcomed the return of local GPs, but when asked if they planned to register with one of the new-coming GPs, most residents were hesitant. Eight contextual factors were identified to impact residents’ intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs. At the infrastructural layer, contextual factors, such as the national GP shortage, the administration fee for registering with a new GP, and the neighbourhood’s negative reputation as being feared and unattractive, were found to be barriers that could prevent residents from registering with one of the new-coming GPs.

At the institutional layer, contextual factors, such as residents’ mistrust towards municipal authorities and the new-coming GPs, their perceived lack of information about the GP coverage intervention, experience of being excluded from the intervention design, combined with the duration without a local GP, were found as barriers that could prevent residents from registering with the GPs. Altogether, these barriers created scepticism and mistrust among residents about whether the GPs were "real" and permanent (not "just, temporary municipal GPs"). Finally, GPs’ reputation were found to either facilitate or hinder residents’ decisions. Overall, the findings indicate that factors such as trust in the GPs and the GPs reputation are more important for residents than having a short geographical distance.

Although the contextual factors are described separately, they are intertwined and influence one another. For example, due to the national GP shortage, many residents were hesitant to register with one of the GPs for fear of being unable to reverse their decision because access to their current GP could be restricted. Thus, they waited to have the GPs recommended by other residents. Similarly, the area’s negative reputation and the residents’ shared history of mistrust towards municipal authorities influenced the residents’ perception of the GP coverage intervention and the new-coming GPs. The fact that the GPs were established as a result of a municipality-driven intervention heightened the mistrust and scepticism. Many of the identified contextual factors, such as mistrust towards public authorities have been reported in similar studies focusing on socially vulnerable groups and disadvantaged neighbourhoods [Citation41,Citation42]. In line with my findings, a study by Srivarathan et al. revealed, for example, how previously negative experiences with municipal social services in Denmark, such as job centres, caused mistrust towards the municipality and prevented residents in a disadvantaged neighbourhood from accepting new municipally driven interventions [Citation39]. Thus, this study supports the notion shared by many researchers of the importance of addressing and ensuring the community’s trust when implementing public health interventions [Citation38,Citation39].

Furthermore, other studies in similarly disadvantaged neighbourhoods have used the framework of territorial stigmatization by Wacquant [Citation34] to interpret how contextual factors influence residents’ perspectives of health-promoting interventions [Citation39,Citation40]. For example, the study conducted by Jensen and colleagues in a disadvantaged Danish neighbourhood found that residents were aware that ‘outsiders’ perceptions of their neighbourhood were negative, but residents did not believe these perceptions were reasonable and fair [Citation40]. Likewise, in our study, many residents expressed that they were aware of the neighbourhood’s bad reputation due to crime, which kept the establishment of new professions, such as GPs, away. Thus, they acknowledged the reputation but did not find it justified. Since the data collection from the present study ended, the two GPs have established themselves in the neighbourhood. They were both females, 55–65 years old, one of Danish origin and the other with an ethnic minority background. Shortly after, a similar GP coverage intervention in another disadvantaged Danish neighbourhood with a GP shortage resulted in the establishment of a local GP [Citation43]. However, six months after the GP was established in the other neighbourhood, only a few residents had registered with the GP, indicating that the present study’s findings may also be relevant to understanding the mechanisms of implementing GPs in other neighbourhoods with similar characteristics [Citation43].

Strengths and weaknesses

Our research has several strengths. One key strength is that we investigate residents from a disadvantaged neighbourhood’s perspectives, a group whose perspectives are seldom heard as they can be difficult for researchers to access [Citation44–46]. The inclusion of Pawson’s context definition and categorisation of contextual influence [Citation32], provided a useful framework for identifying, analysing and understanding how contextual factors embedded in the neighbourhood and society could pose a barrier to some residents, who otherwise prefer a local GP, for registering with one of the new-coming GPs. Furthermore, using the concept of collective explanations [Citation9], we were able to shed light on how the more "invisible" contextual factors embedded in the neighbourhood and society influencing residents intentions to register with one of the new-coming GPs. These novel insights add to a field where existing research often focuses on compositional factors, such as individual characteristics among the study participants [Citation20,Citation41].

However, the study has some limitations. Firstly rather than only discussing the theory of territorial stigma, we could have included it earlier in the fieldwork or analytical phase. Also, it would have strengthened the survey results, if the respondents had indicated whether they were among the residents who had to change GP, when the previous local GP retired, as several of the residents never have had a local GP. This information would have provided more nuanced insights into their responses, as some residents do not prefer having a local GP. Further, even though the survey was distributed to five local organisations and thus completed by different resident groups, the survey results are not representative of sex, age, or ethnicity as we do not have these background variables on the respondents. This was caused by our wish to ensure a high response rate and to make the process manageable for the local stakeholders who assisted with the distribution. Consequently, we prioritised making the survey distribution and completion process as simple as possible by limiting the number of questions. However, based on the observations, we know that there is a higher proportion of females among the respondents, which may have given us different results than if the respondents were equally represented. Similarly, only two of the twenty residents in the focus groups were men, implying that men’s perspectives were underrepresented in the study. Thus, conducting focus groups with residents from all five associations may have strengthened our analysis. Additionally, it is important to consider that the role and interests of local community stakeholders in the neighbourhood may have influenced their perspectives on the role of the community and the process of establishing GPs in the area. However, we primarily used these interviews to supplement our understanding of the residents’ perspectives. Another point to consider is whether the managers’ presence in the focus groups influenced the residents’ participation. For example, some residents may have been more hesitant to share their opinions freely. However, that was not our impression, as the residents seemed engaged and provided honest and personal answers [Citation47].

Implications

This study focuses on the perspectives of residents in a disadvantaged neighbourhood to illuminate the importance of the trust relationship between the GP and patient. We find that residents are aware of the negative stereotyping of their area and the lack of interest from GPs in working there.

The study addresses the importance of researchers and practitioners being aware of contextual factors embedded in the neighbourhood and society when intervening in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Due to the residents’ potential inherent mistrust of public authorities, project stakeholders must be aware that community trust is essential, which can be attained by informing and involving the local community in the development of the intervention. If residents had been informed and involved in the process, they might have been less frustrated, ‘left on their own’, and distrustful of the municipality. Furthermore, it is possible that it would enhance residents’ adoption of the GP clinic. Our findings may be useful in further developing and disseminating the GP coverage intervention to other disadvantaged neighbourhoods and in developing and implementing complex interventions in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. As GP shortages in disadvantaged neighbourhoods are a complex issue with many influencing factors, the effectiveness of the present GP coverage intervention can be discussed. A follow-up study to determine how many residents had actually registered with one of the GPs would be very interesting. Furthermore, more research on how to ensure GP coverage in disadvantaged neighbourhoods is needed, including a focus on GPs’ motives, competencies and conditions for establishing clinics in these areas.

Conclusion

The organization of the Danish healthcare system is a highly political issue and there is an urgent need for a more comprehensive effort to improve equal access to healthcare services for all citizens, especially in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. However, the public debate tends to lack the citizens’ perspective. This study contributes to filling this gap by investigating the residents’ perspectives.

In this study, we explored how infrastructural and institutional contextual factors influenced residents’ intentions to register with new-coming GPs established as part of a municipally-driven GP coverage intervention in a disadvantaged neighbourhood in Copenhagen. We highlight the importance of considering contextual factors embedded within disadvantaged neighbourhoods and society, when developing and implementing health interventions, such as GP coverage interventions in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. These factors include the area’s reputation, which can contribute to internalised territorial stigma among residents, and residents’ mistrust towards public authorities. Our findings emphasize the crucial role of building trust between the residents, the municipality and the GPs.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the study participants, including residents, the local community stakeholders, and project stakeholders. We especially thank the manager of the senior activity center for facilitating access to the neighbourhood, and the local community stakeholders for their invaluable assistance in conducting the survey.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Marchand C, Peckham S. Addressing the crisis of GP recruitment and retention: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(657):e227–37–e237. doi:10.3399/bjgp17X689929.

- Sundhedsministeriet. Sundhedsreformen - gør Danmark sundere. 2022.

- The Danish Government. Lægedækning i hele Danmark. Rapport fra regeringens lægedækningsudvalg. 2017.

- Nexøe J. Danish general practice under threat? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(4):391–392. Available from: doi:10.1080/02813432.2019.1684431.

- Nussbaum C, Massou E, Fisher R, et al. Inequalities in the distribution of the general practice workforce in England: a practice-level longitudinal analysis. BJGP Open. 2021;5(5):BJGPO.2021.0066. doi:10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0066.

- Fischer N DM. 2017. Hver anden ghetto har ingen praktiserende læge.

- Diderichsen F, Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. Planning for health equity in the crossfire between science and policy. Scand J Public Health. 2022;50:875–881. doi:10.1177/14034948221082450.

- VIVE. Primary health care in the nordic countries : comparative analysis and identification of challenges. Copenhagen K, Denmark: VIVE - The Danish Center for Social Science Research; 2020.

- Christensen U, Kristensen EC, Malling Hvid GM. Vulnerability assessment in copenhagen, cities changing diabetes. Copenhagen; 2016.

- Sortsø C, Lauridsen J, Emneus M, et al. Socioeconomic inequality of diabetes patients’ health care utilization in Denmark. Health Econ Rev. 2017;7(1):21. doi:10.1186/s13561-017-0155-5.

- Holm AL, Diderichsen F. Cities changing diabetes rule of halves analysis for copenhagen. 2015. p. 1–48.

- Pemberton S, Humphris R. Locality, neighbourhood and health: a literature review [Internet]. 2016. www.birmingham.ac.uk/iris.

- Ellaway A, Benzeval M, Green M, et al. “Getting sicker quicker”: does living in a more deprived neighbourhood mean your health deteriorates faster? Health Place. 2012;18(2):132–137.

- Poortinga W, Dunstan FD, Fone DL. Neighbourhood deprivation and self-rated health: the role of perceptions of the neighbourhood and of housing problems. Health Place. 2008;14(3):562–575. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.003.

- Knighton AJ, Brunisholz KD, Savitz ST. Detecting risk of low health literacy in disadvantaged populations using area-based measures. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2017;5(3):7. doi:10.5334/egems.191.

- Pedersen SE, Aaby A, Friis K, et al. Multimorbidity and health literacy: a population-based survey among 28,627 danish adults. Scand J Public Health. 2021;51(2):165–172. doi:10.1177/14034948211045921.

- Danish National Police. National strategi for politiets indsats i de saerligt udsatte boligområder. 2019.

- The Health and Care administration. Kvalitativ undersøgelse blandt borgere i tingbjerg om afstand til læge og ønsker til almen praksis. København; 2015.

- Murphy M, Salisbury C. Relational continuity and patients’ perception of GP trust and respect: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):E676–e683. doi:10.3399/bjgp20X712349.

- Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health : how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them ? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(1):125–139. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00214-3.

- Macintyre S, Macdonald L, Ellaway A. Do poorer people have poorer access to local resources and facilities? The distribution of local resources by area deprivation in glasgow, Scotland. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(6):900–914. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.029.

- Mohnen SM, Schneider S, Droomers M. Neighborhood characteristics as determinants of healthcare utilization- A theoretical model. Health Econ Rev. 2019;9(1):7. doi:10.1186/s13561-019-0226-x.

- Olejaz M, Juul Nielsen A, Rudkjøbing A, et al. Denmark health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012;14(2):i.

- Ministry of Health, Healthcare Danmark. Healthcare in Denmark [internet]. Colophon. 2017. p. 1–21. http://www.sum.dk

- General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:34–38.

- City of Copenhagen. City of Copenhagen Health Policy 2015-2025. 2015.

- Tørslev MK, Andersen PT, Nielsen AV, et al. Tingbjerg changing diabetes: a protocol for a long-term supersetting initiative to promote health and prevent type 2 diabetes among people living in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse neighbourhood in copenhagen, Denmark. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e048846. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048846.

- Liste over udsatte boligområder pr. 1. 2021.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374(2018):n2061. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2061.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. SAGE publications; 1997.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(57):1–132. doi:10.3310/hta25570.

- Pawson R. Simple principles for the evaluation of complex programmes. An Evidence-Based Approach to Public Health and Tackling Health Inequalities: practical Steps and Methodological Challenges. 2004. p. 1–36.

- Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e294. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294.

- Wacquant L. Ghettos and anti-ghettos: an anatomy of the new urban poverty. Thesis Eleven. 2008;94(1):113–118. doi:10.1177/0725513608093280.

- Thomsen-Tjørnhøj T, White SR. Fieldwork and participant observation. In Research methods in public health. Gyldendal Akademisk; 2008.

- Kristiansen K. Deltagende observation. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzel; 2015.

- Castleberry A. NVivo 10 [software program]. Version 10. QSR International; 2012. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014 Feb 12;78(1):25. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78125. PMCID: PMC3930250

- Termansen T. Navigating complexity. Aalborg: Aalborg Universitet; 2023.

- Srivarathan A, Jensen AN, Kristiansen M. Community-based interventions to enhance healthy aging in disadvantaged areas: perceptions of older adults and health care professionals 11 medical and health sciences 1117 public health and health services 17 psychology and cognitive sciences 1701 psychology. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3855-6.

- Jensen S, Christensen AD. Territorial stigmatization and local belonging: a study of the danish neighbourhood aalborg east. City. 2012;16(1-2):74–92. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.663556.

- Ezezika OC. Building trust: a critical component of global health. Ann Global Health. 2015;81:589–592. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.12.007.

- Hermesh B, Rosenthal A, Davidovitch N. The cycle of distrust in health policy and behavior: lessons learned from the negev bedouin. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237734. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237734.

- Brix SKJ. Efter et halvt år: kun 152 borgere er flyttet til vollsmose-læge. Tv2 Fyn. 2021.

- Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):42. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-42.

- Ellard-Gray A, Jeffrey NK, Choubak M, et al. Finding the hidden participant: solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-Reach, and vulnerable populations. Int J Qual Methods. 2015;14(5), 1–10.

- Sydor A. Conducting research into hidden or hard-to-reach populations. Nurse Res. 2013;20(3):33–37. doi:10.7748/nr2013.01.20.3.33.c9495.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444.